1. Introduction

Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD), previously known as neuromyelitis optica or Devic’s disease, is a rare autoimmune disease characterized by inflammation and demyelination in the central nervous system (CNS)[

1]. The disease present with a relapsing-remitting course and mainly affects the spinal cord, optic nerves and brainstem with visual loss and paralysis as common clinical manifestations. Untreated, NMOSD often leads to devastating neurological sequele [

2]. Despite being reminiscent of multiple sclerosis (MS), discriminative clinical and radiological criteria for NMOSD have been available since the 1990s [

2] and the discovery of IgG antibodies (abs) against the water channel aquaporin-4 (AQP4) has contributed significantly to improve diagnosis and treatment [

3].

Around 10-30% of patients fulfilling criteria for a NMOSD diagnosis, according to the 2015 diagnostic criteria [

4] are seronegative for AQP4-IgG [

5,

6] in which a proportion of the patients present with IgG-antibodies against myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) [

7]. Detection of MOG-IgG can be found in patients with different clinical manifestations including optic neuritis, myelitis, brainstem encephalitis and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, in addition to the patients with a diagnosis of AQP4-seronegative-NMOSD [

8]. In recent years MOG-IgG-associated disease (MOGAD) has been acknowledged as an inflammatory demyelinating disease of the CNS with distinct immunobiological characteristics separate from AQP4+NMOSD [

8]. Another subset of patients, that fulfil NMOSD diagnostic criteria, have neither detection of AQP4-IgG, or MOG-IgG, commonly referred to as double-seronegative NMOSD [

9]. The knowledge about the immunopathogenesis in double-seronegative NMOSD is limited and the disorder seems to be more clinically heterogenous and often results in diagnostic and treatment challenges [

9].

NMOSD is a rare disease, with an estimated prevalence of 0.54 – 4.4/100,000 individuals but a significantly increased incidence of NMOSD in Sweden was recently described with a current incidence of 0.79 per 1,000,000 person-years [

10,

11]. NMOSD patients confer a high risk for severe relapses, often with residual disabilities, and disease modifying therapies (DMTs) are crucial in managing the disease [

2,

12]. Approved DMTs for NMOSD have been lacking until very recently when four monoclonal antibodies; sartralizumab, inebilizumab, eculizumab and rituximab, received approvals for AQP4+ NMOSD [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Guidelines for treatment recommendations have previously only included off-label regimen with immunosuppressive therapies such as azathioprine, methotrexate and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) with support from real-world data studies, case series and small randomized trials [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22]. Following results from a phase 3 randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial [

23] in addition to real-world data, rituximab was recommended as first line maintenance therapy in AQP4+ NMOSD by the European Federation of Neurological Societies [

24,

25,

26] and in the 2015 recommendations of the Neuromyelitis Optica Study Group [

27] and later updates [

28]. Also in Sweden, rituximab has been frequently used for NMOSD and was recommended as first-line DMT for AQP4+ NMOSD in recent updated guidelines from the Swedish Multiple Sclerosis Association [

29]. Treatment guidelines for relapse preventive therapies in MOGAD and double-seronegative NMOSD are much more limited. Beneficial effect of rituximab in suppressing disease activity in MOGAD has been demonstrated, while recent data indicated less effect on clinical attacks when compared to AQP4+ NMOSD [

30,

31].

Safety concerns for rituximab as a long-term DMT for MS have occurred due to its association with an increased risk for infections [

32]. Similar findings of an increased risk of infections in NMOSD and MOGAD patients treated with rituximab were reported [

33], although the knowledge about the extent, severity and types of infections remains more unclear.

In this study we aimed to collect real-world data regarding efficacy and safety of rituximab therapy in a Swedish cohort of patients with a diagnosis of NMOSD including AQP4+, MOG+ and double-seronegative subgroups. We assessed the frequency and risk of relapses, and severe infectious events (SIEs), during a long follow-up time for up to eight years. We collected data on rituximab dosing regimen and reasons for discontinuation. Further, we correlated CD19+ lymphocyte counts with relapse risk and serum IgG levels with SIE risk, to assess their value as biomarkers for treatment monitoring.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study patients

All adult patients (≥18 years) at the Karolinska University Hospital with a diagnosis of NMOSD according to the 2015 international consensus diagnostic criteria were identified in the Swedish Neuroregistry (SMSreg). Patients treated with rituximab during January 2012 to December 2021 were included. All patients, including the NMOSD patients with detection of MOG-IgG had been diagnosed and treated according to a diagnosis of NMOSD. This was because of the study period for which the knowledge of MOGAD, as a separate disease, had not been established. According to the very recent proposal of diagnostic criteria for MOGAD [

34], some of the current patients categorized as ‘MOG+ NMOSD’ did also fulfill criteria for relapsing MOGAD because of diagnostic overlap.

The study was approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Dnr 2020-03942). All patients are registered in the SMSreg which signifies that the patient consent to all research based on data from the registry. Further acquisition of informed consent was thereby waived, as commonly applied in Sweden for studies using pseudonymized data from national health registries and medical reports.

2.2. Data collection and analyses of AQP4-IgG and MOG-IgG serostatus

Electronic medical charts were reviewed to collect patient data including sex, age at diagnosis, co-morbidities, prior and ongoing immunosuppressive therapy, neurological function at rituximab treatment initiation according to the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS)[

35], relapses, infectious events, deaths, cause of death and laboratory serum analyses (AQP4-IgG, MOG-IgG, total IgG-levels and CD19+ lymphocyte counts). Relapses were defined as the appearance of new neurological symptoms with duration for a period of at least 24 hours and absence of evidence of an infection or fever. A SIE was defined as an infection requiring intravenous antibiotics, hospital admission or death caused by the infection. The laboratory analyses of AQP4-IgG and MOG-IgG were performed at Wieslab Laboratories, Malmö, Sweden, or (since year 2014) in-house at the Karolinska University Hospital, Stockholm, Sweden. Immunoblot assay was used until year 2012 whereafter a cell-based assay has been utilized.

2.3. Statistical analyses

Data on patient characteristics and rituximab dosing was compiled using descriptive statistics. Continuous variables were described as mean or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), or ranges. Categorical data were described as values and proportions. Inter-subgroup differences were analyzed with Kruskal-Wallis for continuous data and Pearson’s chi-squared test for categorical data. Poission modelling was applied to calculate the incidence risk ratio (IRR) for relapses and SIEs. Kaplan-Meier estimators were used to assess the time to first relapse and first SIE and, relative differences between subgroups were analysed using Cox proportional hazard regression modelling. The median and IQR of CD19+ lymphocytes and IgG were plotted separately to examine potential trends over cumulative doses of rituximab in subgroups. Logistic regression models were used to analyse correlations between CD19+ lymphocyte count and relapses, as well as correlation of SIEs with IgG levels, EDSS at baseline and prior immunosuppression. The significance level was set as p <0.05. Statistical analyses were performed utilizing the software Statistica 13 and Stata MP 17.

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics

All 42 patients included in the study fulfilled the 2015 criteria for a NMOSD diagnosis [

5], patient characteristics are described in

Table 1. Based on serostatus, the patients were subgrouped as: AQP4+ (n=24; 92% females), MOG+ (n=8, 50% females) and double-seronegative (n=10; 70% females). The mean age at rituximab treatment start was: 50, 37 and 41 years for AQP4+, MOG+ and double-seronegative patients, respectively. The median disease duration at rituximab initiation was 14.5 months (IQR: 3-72) for the total study cohort; 48 months (IQR: 2-96) for AQP4+, 16 months (IQR: 2,5-48) for MOG+, and 8 months (IQR: 5-36) for double-seronegative patients. Neurological disability, assessed by EDSS, at rituximab start, was comparable between the subgroups with a mean EDSS of 4 (range: 2-7) overall. Six patients, all among AQP4+ patients, had a co-morbid rheumatologic disease including Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (n=4), Sjögrens Syndrome (n=1), and Rheumatoid Arthritis (n=1). A history of a prior malignant disorder was found in two patients: one AQP4+ patient with previous breast cancer and one double-seronegative patient with cervix cancer. Immunosuppressive therapy had been prescribed in 12 patients prior rituximab start, mainly AQP4+ patients (n=9), including azathioprine (n=10), cyclophosphamide (n=3), methotrexate (n=1), interferon-beta-1a (n=1) and fingolimod (n=1).

3.2. Rituximab treatment

Rituximab was prescribed as first-line DMT in 62% of the patients, dosing regimen is described in

Table 2. The induction dose varied between 100-2000 mg, the mean maintenance dose was 100-1000 mg, and the mean cumulative dose was 4640 mg (IQR: 1000-8000 mg) in the cohort. Oral prednisolone was administered intermittently concomitant in 75% of AQP4+ patients, half of MOG+ patients and half of the double-seronegative patients. Concomitant treatment with azathioprine was noted in six AQP4+, one MOG+ and two double-seronegative patients. Tocilizumab had been used in parallel with rituximab in two AQP4+, two MOG+ and one double seronegative patient. The mean follow-up time, defined as number of years from the initial dose of rituximab to six months after the last dose of rituximab, was 4.4 (range: 0.9-7.7) for AQP4+, 2.6 (range: 0.5-4.8) for MOG+ and 4.2 (range: 0.8-8.3) years for double-seronegative patients.

More than a third of all patients; (38%) discontinued rituximab treatment during the study period. Within the AQP4+ group seven (29%) patients discontinued treatment due to the following reasons: new disease activity (of which one patient had anti-rituximab antibodies (n=3), SIEs (n=1), IgG hypogammaglobulinemia (n=1), emigration (n=1), old age and long-term stable disease (n=1). Five (63%) MOG+ patients stopped rituximab due to new disease activity including one that also experienced several infections including one SIE. Four (40%) double-seronegative patients stopped treatment due to insufficient B-cell depletion (n=1), new disease activity (n=1), SIE (n=1), and IgG hypogammaglobulinemia (n=1).

3.3. Relapse activity

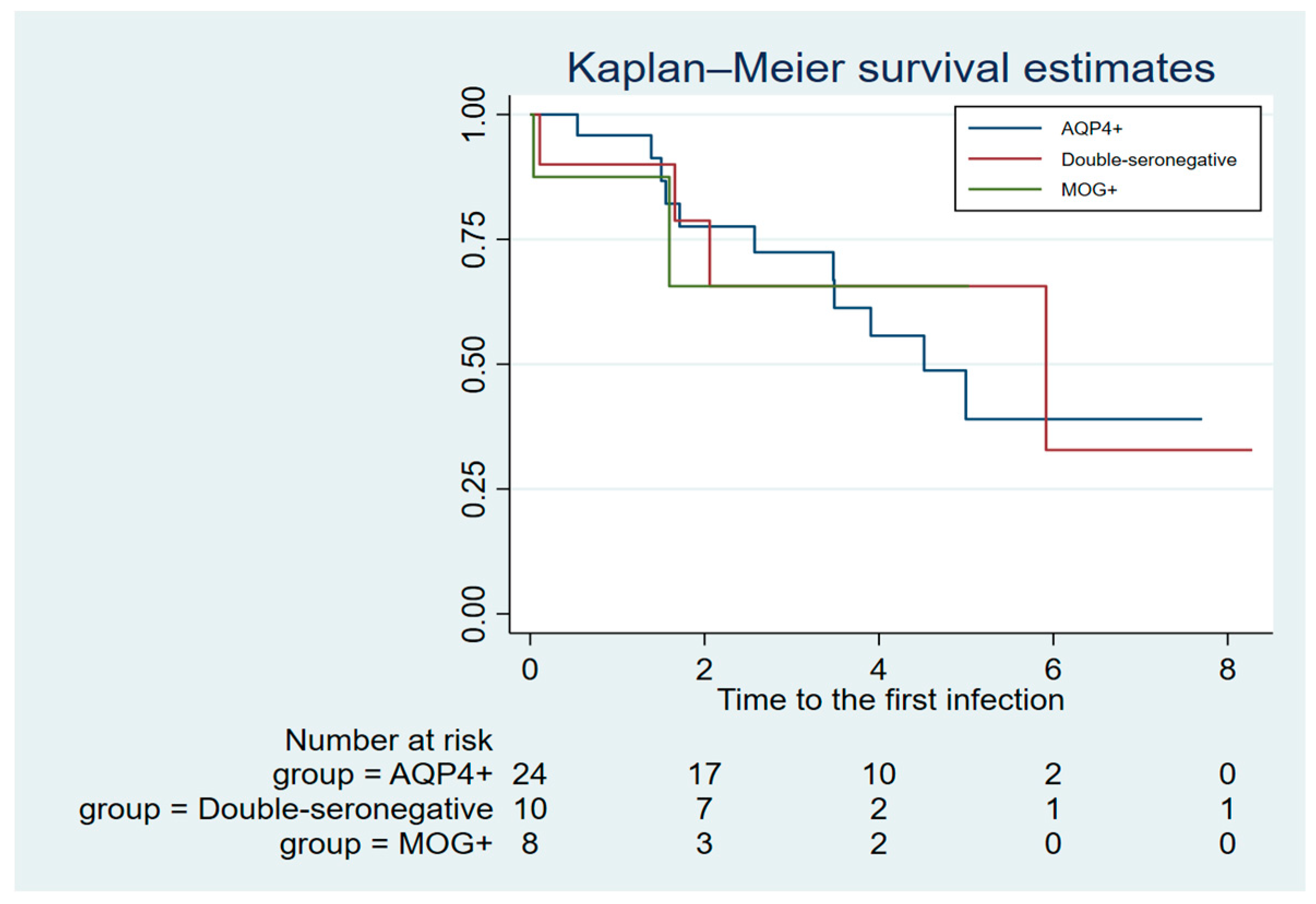

A total of 21 (50%) patients relapsed during follow-up, including nine (37%) AQP4+, six (75%) MOG+ and six (60%) double-seronegative patients. The mean ARR was 0.21 (IQR: 0-0.5) in the AQP4+ group, 1.7 (IQR: 0.5-2.6) in the MOG+ group and 0.48 (0-0.6) in the double-seronegative group. The incidence risk ratio (IRR) for a relapse was three times higher in MOG+ compared to AQP4+ (IRR: 3.0, 95% CI 1.2- 7.7). No significant difference in the IRR for a relapse was found between AQP4+ and double-seronegative patients (IRR: 1.8, 95% CI 0.7- 4.8) or between MOG+ and double-seronegative patients (IRR: 0.6, 95% CI 0.2-1.8). Kaplan-Maier survival estimates for time to first relapse (

Figure 1) demonstrated early relapse activity in the MOG+ and double-seronegative group with 75% of MOG+, and more than half of the double-seronegative patients, affected two years after rituximab start. The AQP4+ group exhibited a different pattern with less relapse activity in the first years following treatment start, but it also shows persisting risk of a relapse after more than six relapse-free years on treatment. A shorter time to first relapse in MOG+ compared to AQP4+ patients was observed (HR; 3.8, 95% CI 1.2-11.8) while no differences was found between AQP4+ and double-seronegative patients (HR; 1.7, 95% CI 0.6- 4.6), or between MOG+ and double-seronegative patients (HR 0.4, 95% CI 0.1-1.4).

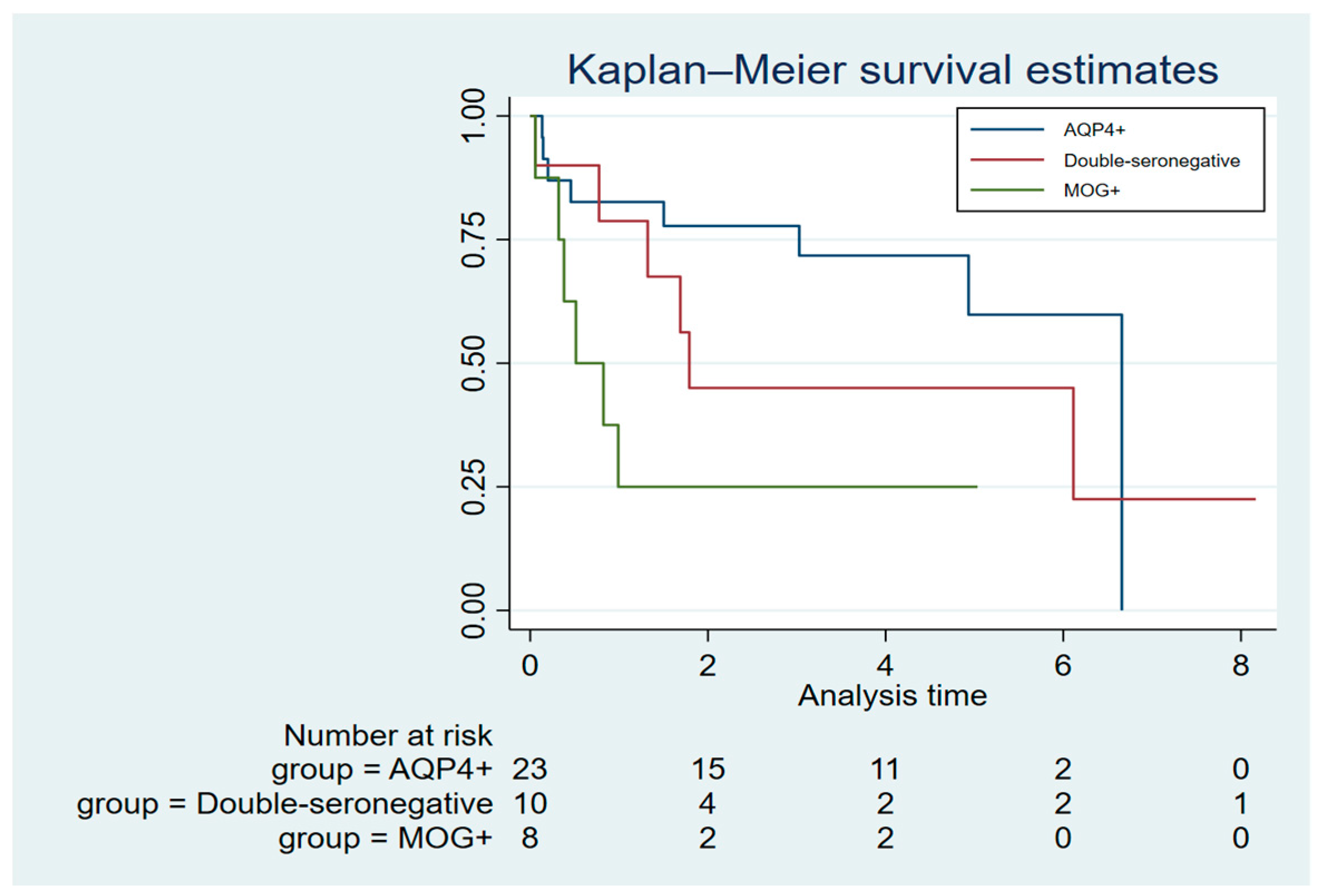

3.4. Severe infectious events and malignancy

The occurrence of ≥1 SIE was observed in 40% of all patients including 11 (46%) AQP4+, two (25%) MOG+, and four (40%) double-seronegative patients. The mean annual SIE rate for AQP4+ patients was 0.32 (range: 0-3.3), 0.1 (range: 0-0.6) for MOG+ patients and 0.18 (range: 0-1.3) for double-seronegative patients. AQP4+ patients conferred an increased risk for SIE compared to MOG+ (IRR; 5.3, 95% CI: 1.2-24.3). No significant differences between the MOG+ and the double-seronegative group (IRR; 2.4, 95% CI: 0.5-11.3), or between the AQP4+ and the double-seronegative patients (IRR; 0.5, 95% CI: 0.1-1.7), was found. Kaplan-Maier survival analysis for time to first SIE showed comparable trends between the subgroups which was confirmed with Cox regression analyses; AQP4+ versus (vs) MOG+: HR; 1.0, 95% CI 0.2-2.9 and AQP4+ vs double-seronegative: HR; 1.0, 95% CI 0.3-2.9 and MOG+ vs double-seronegative: HR; 1.0, 95% CI 0.2-6.5), (

Figure 2).

Common to all groups, the most frequent types of SIEs were urinary tract infections with 50% affected, and upper respiratory infections (50%), pneumonia (27.5%) and bacterial skin infections (27.5%) as described in

Table 3. Sepsis occurred in 17.5% of all patients. Three patients (all AQP4+) died during hospitalization for a SIE including one patient with respiratory failure and soft tissue pseudomonas aeruginosa infection, one patient with pneumonia and sepsis and nasopharyngeal culture positive for Streptococcus pneumoniae, and one patient with respiratory failure and chronic decubitus ulcers.

Using logistic regression, adjusting for age at rituximab start, we found no significantly increased risk of SIEs for patients with moderate/high EDSS (>3) compared to low EDSS (≤3) (HR; 1.6, 95% CI 0,5-5,8). Likewise, the frequency of SIEs was not correlated with the usage of immunosuppressive therapy before rituximab start (HR; 3.0, 95% CI 0,7-12.2).

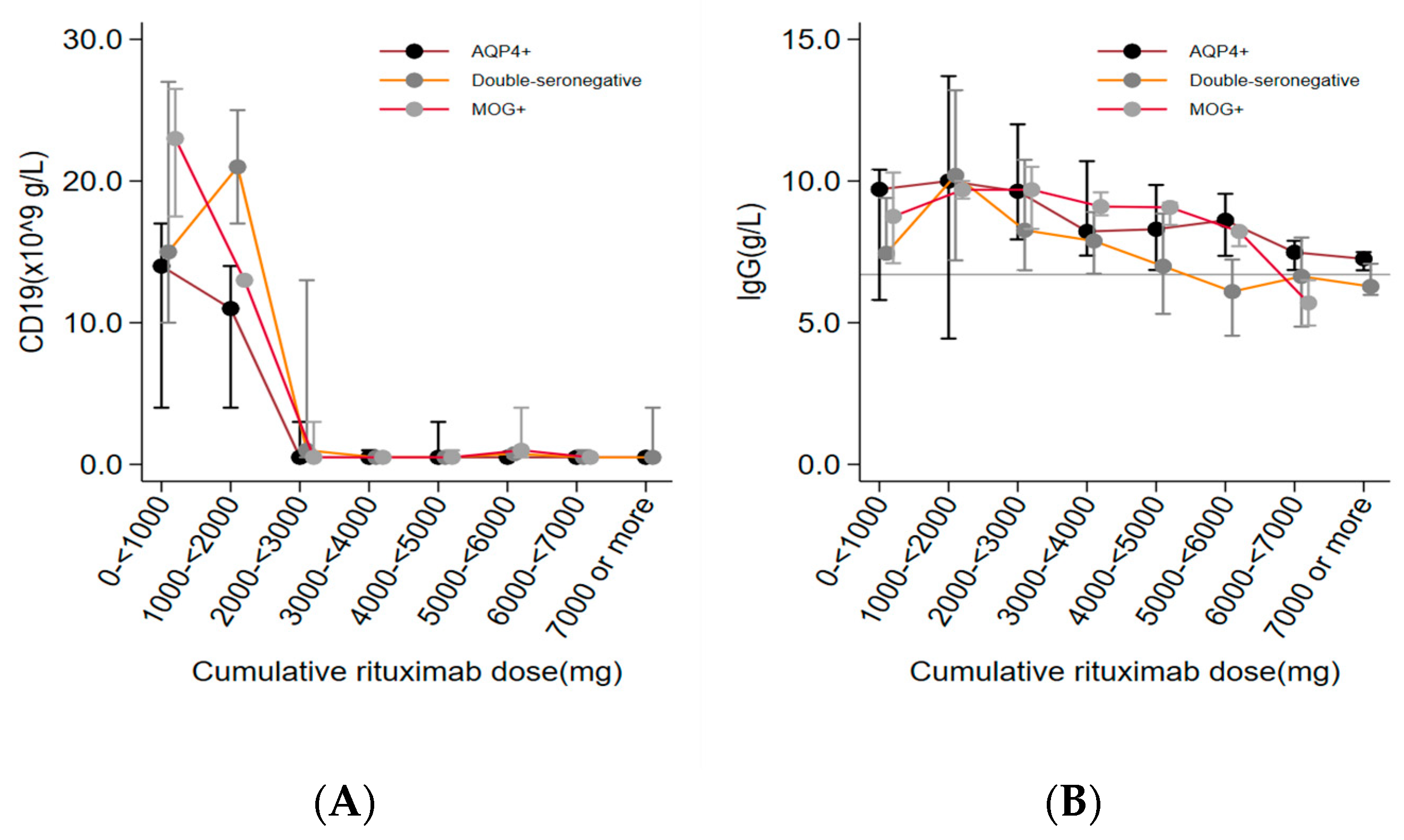

CD19+ lymphocyte counts and IgG levels

Complete suppression of CD19+ lymphocytes (defined as: CD19+ < 0.01 x 10

9 g/L) occurred in most patients when exposed to cumulative doses of 2-3000 mg rituximab (

Figure 3). We found no correlation between relapse and incomplete CD19+ suppression (defined as; CD19+ > 0.01x 10

9 g/L) (HR; 1.9, 95% CI 0.7-5.2).

A non-significant trend of a correlation between decreasing IgG levels and cumulative doses of rituximab was observed in the total cohort. The mean level of IgG was below the lower reference limit (<6.7 g/L) at cumulative doses of 5000 - > 6000 mg rituximab in double-seronegative patients and at 6000- >7000 mg in MOG+ patients while the majority of AQP4+ patients remained with IgG levels within the normal reference interval during the study period (

Figure 2). A median drop in IgG levels of 0.35 g /L (95% CI 0.23-0.47 g/L) per 1000 mg rituximab was found in the total study group.Logistic regression analyses, adjusted for age, showed no significant correlation between frequency of SIEs and low IgG levels (defined as IgG levels < 6.7 g/L), (OR; 2.0, 95% CI 0.8-4.8). One double-seronegative patient was diagnosed with lymphoma after receiving a total of 1500 mg rituximab. Malignancy was not detected in the AQP4+ and MOG+ groups during treatment.

4. Discussion

This retrospective cohort study observed a substantial relapse- and SIE burden for NMOSD patients treated with rituximab. Almost half of the AQP4+ patients experienced at least one SIE and the risk for SIE in this subgroup was increased compared to MOG+ patients. On the other hand, MOG+ patients had an increased risk for a relapse, compared to AQP4+ patients, with 75% affected during the current observation period. Discontinuation of rituximab was common in the total cohort. Clinical routine monitoring with assessment of IgG levels offered limited value to predict the occurrence of SIEs among the patients. Similarly, CD19 counts were not correlated with relapse activity.

The present finding of 63% relapse-free patients in the AQP4+ patients during follow up is in line with results from a systematic review with 62.9% relapse-free AQP4+ patients during a mean rituximab treatment time of 1.0-6.6 years [

36].

The efficacy of rituximab therapy in MOG+ and double-seronegative NMOSD have been less studied compared to AQP4+ patients. Most evidence of rituximab treatment efficacy in patients with presence of MOG-IgG abs has been provided by studies composed of heterogenous MOGAD cohorts in contrast to the present study restricted to patients that also fulfilled criteria for a diagnosis of NMOSD [

31]. Our observations are nevertheless in line with previous findings showing a higher occurrence of relapses in MOGAD compared to AQP4+ NMOSD during rituximab treatment [

30,

37]. A recent meta-analysis compared relapse frequency among MOGAD patients with different maintenance immunosuppressive therapies, including rituximab, and reported an overall relapse frequency of 62% during a mean treatment period of 1.2 years [

38]. The authors concluded that maintenance therapy with intravenous immunoglobin (IVIG) conferred the lowest ARR compared to rituximab, MMF, azathioprine and cyclophosphamide, respectively, indicating that IVIG might had been a more effective option as first-line DMT for the current MOG+ patients [

38].

It is of value to note that the late introduction of standardized NMOSD treatment guidelines, at our center, lower annual doses of rituximab had been used, compared to doses administered at other centers, which might negatively have impacted on the relapse frequency [

26]

The present observation of SIEs in 40% of all patients was somewhat unexpected. Previous retrospective studies on AQP4+ and/or MOGAD cohorts treated with rituximab found SIEs in 8-19% of the patients which is substantially lower compared to our findings [

24,

30,

33,

39]. The difference in follow-up time, age, co-morbidities, and heterogenous NMOSD cohorts, between the studies, do likely explain the variance in SIE frequency. We observed no association between EDSS and SIE which contrast previous findings [

39] but may reflect the current relatively low mean EDSS score at treatment start in our cohort.

An increasing body of evidence indicate that infections play an important role as triggers for onset and relapses in NMOSD [

40]. Common colds, otitis media, sinusitis, urinary tract infection and gastrointestinal infections were reported to precede clinical attacks in NMOSD patients [

41]. Postulated mechanisms behind the role of infections in NMOSD disease activity are bystander activation, molecular mimicry and disease exacerbation by systemic inflammation involving increased CSF interleukin (IL)-6 levels with promotion of AQP4+ ab secretion from plasmablasts [

42]. Our results emphasize the need for a high surveillance for infections in rituximab-treated NMOSD patients, in addition to thorough optimization of vaccination strategies. Furthermore, some patients may also need prophylactic antimicrobial therapy.

We observed no apparent correlation between IgG-levels and SIEs. IgG hypogammaglobulinemia and/or reduced levels of IgG has been reported to associate with risk of infections in rituximab-treated patients with rheumatic disease [

43] but similar risks in NMOSD patients are less explored. Data from a Korean patient cohort found decreased levels of IgG in 41% of rituximab-treated NMOSD patients with a mean treatment time of eight years, however, there was no association between risk of infection and hypogammaglobulinemia [

39].

The current limited clinical benefit of rituximab in combination with the results of a lower frequency of SIEs among patients pertaining to the MOG+ group lend further support that MOG+ patients shall be referred and treated to as a separate CNS demyelinating disease entity [

44]. Interestingly, the inadequate relapse preventive effect in the MOG+ group was seen despite successful CD19+ B-cell suppression. Accordingly, it can be reasoned that other mechanisms are pivotal in the maintenance of the autoimmune attacks in MOG+ patients. In addition, the findings of a high frequency of other autoimmune disease in AQP4+, but not in MOG+, nor double seronegative patients, further argues for diverse mechanisms involved in the dysregulated immune response in the different subgroups of patients fulfilling the present diagnostic criteria for NMOSD [

45].

A limitation in the present study is the relatively small sample sizes of subgroups and the intra-and inter-group adjunctive treatment heterogeneity which may have affected data analysis and interpretation. Further, the relatively late introduction of standard protocols for laboratory monitoring during rituximab treatment in our center have resulted in gaps of IgG and CD19 lymphocyte count which might have had an impact on these results. The long follow up time in addition to complete data regarding SIEs associated with access to medical charts is a strength of the study. A future prospective study including larger number of patients and longitudinal collection of serum immune markers will provide further information regarding risk factors for the development of relapses and SIEs in patients with a diagnosis of NMOSD or MOGAD.

5. Conclusion

Although previous studies have suggested rituximab treatment of NMOSD to be effective and safe, our cohort shows a significant burden of relapses and SIEs. This highlights the need to find more effective treatments and to imply thorough clinical surveillance of the patients to prevent disability and severe infections. Collecting real-world data is fundamental in understanding the effectiveness and safety of NMOSD and MOGAD treatments and should be systematically applied, as possible, especially when applying off-label therapies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.I.J, L.B and E.I.; Methodology, O. C., D.I.J, E.I.; Formal analyses, O.C., D.I.J, Data analyses: O.C., D.I.J., L.B., E. I., Writing—original draft preparation, D.j., E.I., Writing—review and editing, O.C., D.i.J., L.B., E.I., X.X.; Supervision, E.I., L.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Region Stockholm Clinical Research Appointment (no 108291).

Institutional Review Board Statement

study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Dnr 2020-03942, date of approval: 2020-11-18).

Informed Consent Statement

All study patients are registered in the Swedish Multiple Sclerosis Registry (

https://www.neuroreg.se/multipel-skleros/) which denotes that the patient consent to all research based on data from the registry. Further acquisition of informed consent is thereby waived.

Data Availability Statement

Research data supporting the study are available upon request from the author.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to all patients included in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

O.C. and D.I.J. declare no conflicts of interest. L.B. has received travel grants and lecturing fees from Sanofi/ Genzyme, Biogen, Amirall, and MedDay. L.B. has participated in advisory boards for Genzyme, Sanofi, Biogen, Amirall and Merck. E.I. has received honoraria for serving on advisory boards for Biogen, Sanofi-Genzyme and Merck and speaker’s fees from Biogen and Sanofi-Genzyme. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Wingerchuk DM, Lennon VA, Lucchinetti CF, Pittock SJ, Weinshenker BG. The spectrum of neuromyelitis optica. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(9):805-15.

- Wingerchuk DM, Hogancamp WF, O’Brien PC, Weinshenker BG. The clinical course of neuromyelitis optica (Devic’s syndrome). Neurology. 1999;53(5):1107-14. [CrossRef]

- Lennon VA, Wingerchuk DM, Kryzer TJ, Pittock SJ, Lucchinetti CF, Fujihara K, et al. A serum autoantibody marker of neuromyelitis optica: distinction from multiple sclerosis. Lancet. 2004;364(9451):2106-12. [CrossRef]

- Wingerchuk DM, Banwell B, Bennett JL, Cabre P, Carroll W, Chitnis T, et al. International consensus diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Neurology. 2015;85(2):177-89. [CrossRef]

- Hyun JW, Jeong IH, Joung A, Kim SH, Kim HJ. Evaluation of the 2015 diagnostic criteria for neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Neurology. 2016;86(19):1772-9. [CrossRef]

- Hamid SH, Elsone L, Mutch K, Solomon T, Jacob A. The impact of 2015 neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders criteria on diagnostic rates. Mult Scler. 2017;23(2):228-33. [CrossRef]

- Reindl M, Waters P. Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibodies in neurological disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15(2):89-102. [CrossRef]

- Sechi E, Cacciaguerra L, Chen JJ, Mariotto S, Fadda G, Dinoto A, et al. Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein Antibody-Associated Disease (MOGAD): A Review of Clinical and MRI Features, Diagnosis, and Management. Front Neurol. 2022;13:885218. [CrossRef]

- Wu Y, Geraldes R, Jurynczyk M, Palace J. Double-negative neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Mult Scler. 2023;29(11-12):1353-62. [CrossRef]

- Jonsson DI, Sveinsson O, Hakim R, Brundin L. Epidemiology of NMOSD in Sweden from 1987 to 2013: A nationwide population-based study. Neurology. 2019;93(2):e181-e9. [CrossRef]

- Flanagan EP, Cabre P, Weinshenker BG, Sauver JS, Jacobson DJ, Majed M, et al. Epidemiology of aquaporin-4 autoimmunity and neuromyelitis optica spectrum. Ann Neurol. 2016;79(5):775-83. [CrossRef]

- Cabrera-Gomez JA, Bonnan M, Gonzalez-Quevedo A, Saiz-Hinarejos A, Marignier R, Olindo S, et al. Neuromyelitis optica positive antibodies confer a worse course in relapsing-neuromyelitis optica in Cuba and French West Indies. Mult Scler. 2009;15(7):828-33. [CrossRef]

- Yamamura T, Kleiter I, Fujihara K, Palace J, Greenberg B, Zakrzewska-Pniewska B, et al. Trial of Satralizumab in Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(22):2114-24. [CrossRef]

- Traboulsee A, Greenberg BM, Bennett JL, Szczechowski L, Fox E, Shkrobot S, et al. Safety and efficacy of satralizumab monotherapy in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(5):402-12. [CrossRef]

- Cree BAC, Bennett JL, Kim HJ, Weinshenker BG, Pittock SJ, Wingerchuk DM, et al. Inebilizumab for the treatment of neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (N-MOmentum): a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled phase 2/3 trial. Lancet. 2019;394(10206):1352-63. [CrossRef]

- Pittock SJ, Fujihara K, Palace J, Berthele A, Kim HJ, Oreja-Guevara C, et al. Eculizumab monotherapy for NMOSD: Data from PREVENT and its open-label extension. Mult Scler. 2022;28(3):480-6.

- Costanzi C, Matiello M, Lucchinetti CF, Weinshenker BG, Pittock SJ, Mandrekar J, et al. Azathioprine: tolerability, efficacy, and predictors of benefit in neuromyelitis optica. Neurology. 2011;77(7):659-66.

- Moog TM, Smith AD, Burgess KW, McCreary M, Okuda DT. High-efficacy therapies reduce clinical and radiological events more effectively than traditional treatments in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. J Neurol. 2023;270(7):3595-602. [CrossRef]

- Chen H, Qiu W, Zhang Q, Wang J, Shi Z, Liu J, et al. Comparisons of the efficacy and tolerability of mycophenolate mofetil and azathioprine as treatments for neuromyelitis optica and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Eur J Neurol. 2017;24(1):219-26. [CrossRef]

- Nikoo Z, Badihian S, Shaygannejad V, Asgari N, Ashtari F. Comparison of the efficacy of azathioprine and rituximab in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: a randomized clinical trial. J Neurol. 2017;264(9):2003-9. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Chen L, Wu L, Yao J, Wang N, Su X, et al. Effective Rituximab Treatment in Patients with Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorders Compared with Azathioprine and Mycophenolate. Neurol Ther. 2022;11(1):137-149. [CrossRef]

- Montcuquet A, Collongues N, Papeix C, Zephir H, Audoin B, Laplaud D, et al. Effectiveness of mycophenolate mofetil as first-line therapy in AQP4-IgG, MOG-IgG, and seronegative neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Mult Scler. 2017;23(10):1377-84. [CrossRef]

- Tahara M, Oeda T, Okada K, Kiriyama T, Ochi K, Maruyama H, et al. Safety and efficacy of rituximab in neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders (RIN-1 study): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(4):298-306. [CrossRef]

- Poupart J, Giovannelli J, Deschamps R, Audoin B, Ciron J, Maillart E, et al. Evaluation of efficacy and tolerability of first-line therapies in NMOSD. Neurology. 2020;94(15):e1645-e56. [CrossRef]

- Novi G, Bovis F, Capobianco M, Frau J, Mataluni G, Curti E, et al. Efficacy of different rituximab therapeutic strategies in patients with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2019;36:101430. [CrossRef]

- Damato V, Evoli A, Iorio R. Efficacy and Safety of Rituximab Therapy in Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73(11):1342-8.

- Trebst C, Jarius S, Berthele A, Paul F, Schippling S, Wildemann B, et al. Update on the diagnosis and treatment of neuromyelitis optica: recommendations of the Neuromyelitis Optica Study Group (NEMOS). J Neurol. 2014;261(1):1-16. [CrossRef]

- Jarius S, Aktas O, Ayzenberg I, Bellmann-Strobl J, Berthele A, Giglhuber K, et al. Update on the diagnosis and treatment of neuromyelits optica spectrum disorders (NMOSD) - revised recommendations of the Neuromyelitis Optica Study Group (NEMOS). Part I: Diagnosis and differential diagnosis. J Neurol. 2023;270(7):3341-68.

- https://www.svenskamssallskapet.se/nmosd/.

- Barreras P, Vasileiou ES, Filippatou AG, Fitzgerald KC, Levy M, Pardo CA, et al. Long-term Effectiveness and Safety of Rituximab in Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder and MOG Antibody Disease. Neurology. 2022;99(22):e2504-e16. [CrossRef]

- Nepal G, Kharel S, Coghlan MA, Rayamajhi P, Ojha R. Safety and efficacy of rituximab for relapse prevention in myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein immunoglobulin G (MOG-IgG)-associated disorders (MOGAD): A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neuroimmunol. 2022;364:577812.

- Rico A, Ninove L, Maarouf A, Boutiere C, Durozard P, Demortiere S, et al. Determining the best window for BNT162b2 mRNA vaccination for SARS-CoV-2 in patients with multiple sclerosis receiving anti-CD20 therapy. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2021;7(4):20552173211062142.

- Avouac A, Maarouf A, Stellmann JP, Rico A, Boutiere C, Demortiere S, et al. Rituximab-Induced Hypogammaglobulinemia and Infections in AQP4 and MOG Antibody-Associated Diseases. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2021;8(3). [CrossRef]

- Banwell B, Bennett JL, Marignier R, Kim HJ, Brilot F, Flanagan EP, et al. Diagnosis of myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease: International MOGAD Panel proposed criteria. Lancet Neurol. 2023;22(3):268-82. [CrossRef]

- Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology. 1983;33(11):1444-52.

- Gao F, Chai B, Gu C, Wu R, Dong T, Yao Y, et al. Effectiveness of rituximab in neuromyelitis optica: a meta-analysis. BMC Neurol. 2019;19(1):36. [CrossRef]

- Durozard P, Rico A, Boutiere C, Maarouf A, Lacroix R, Cointe S, et al. Comparison of the Response to Rituximab between Myelin Oligodendrocyte Glycoprotein and Aquaporin-4 Antibody Diseases. Ann Neurol. 2020;87(2):256-66. [CrossRef]

- Chen JJ, Flanagan EP, Bhatti MT, Jitprapaikulsan J, Dubey D, Lopez Chiriboga ASS, et al. Steroid-sparing maintenance immunotherapy for MOG-IgG associated disorder. Neurology. 2020;95(2):e111-e20.

- Kim SH, Park NY, Kim KH, Hyun JW, Kim HJ. Rituximab-Induced Hypogammaglobulinemia and Risk of Infection in Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorders: A 14-Year Real-Life Experience. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2022;9(5).

- Sellner J, Hemmer B, Muhlau M. The clinical spectrum and immunobiology of parainfectious neuromyelitis optica (Devic) syndromes. J Autoimmun. 2010;34(4):371-9. [CrossRef]

- Wang L, Zhou L, ZhangBao J, Huang W, Tan H, Fan Y, et al. Causal associations between prodromal infection and neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder: A Mendelian randomization study. Eur J Neurol. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Sellner J, Cepok S, Kalluri SR, Nestler A, Kleiter I, Kumpfel T, et al. Aquaporin 4 antibody positive central nervous system autoimmunity and multiple sclerosis are characterized by a distinct profile of antibodies to herpes viruses. Neurochem Int. 2010;57(6):662-7.

- Md Yusof MY, Vital EM, McElvenny DM, Hensor EMA, Das S, Dass S, et al. Predicting Severe Infection and Effects of Hypogammaglobulinemia During Therapy With Rituximab in Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(11):1812-23.

- Fujihara K. MOG-antibody-associated disease is different from MS and NMOSD and should be classified as a distinct disease entity - Commentary. Mult Scler. 2020;26(3):276-8. [CrossRef]

- Jarius S, Ruprecht K, Wildemann B, Kuempfel T, Ringelstein M, Geis C, et al. Contrasting disease patterns in seropositive and seronegative neuromyelitis optica: A multicentre study of 175 patients. J Neuroinflammation. 2012;9:14. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).