1. Introduction

White cataracts represent one of the most technically challenging conditions in modern cataract surgery [

1,

2,

3,

4]. They are characterized by complete opacification of the crystalline lens with an absent or markedly reduced red reflex, which precludes preoperative visualization of the lens nucleus and posterior capsule. As a result, surgeons must manage increased risks of anterior capsule tear, posterior capsule rupture, zonular instability, and corneal endothelial damage during phacoemulsification [

1,

3,

4]. Unlike ordinary cataracts, white cataracts do not allow accurate preoperative assessment of nuclear hardness. Surgical difficulty is therefore determined intraoperatively, often after capsulorrhexis and partial debulking of the lens material. Furthermore, these eyes frequently exhibit elevated intralenticular pressure, fragile capsules, and weakened zonules, all of which contribute to an increased incidence of intraoperative complications [

1,

4,

5,

6]. Consequently, safe and efficient nucleus management remains a critical issue in the surgical treatment of white cataracts.

Various surgical techniques have been proposed to address the challenges associated with white cataracts, including extracapsular cataract extraction, divide-and-conquer, phaco-chop, and stop-and-chop techniques [

3,

4,

7,

8,

9,

10]. However, many of these techniques rely on initial phacoemulsification of an undivided hard nucleus, which can transmit substantial stress to the posterior capsule and zonules. This limitation is particularly problematic in white cataracts, where capsular and zonular fragility is frequently encountered [

1,

3]. Therefore, an ideal surgical technique for white cataracts should enable reliable nucleus fragmentation while minimizing ultrasound energy, fluid usage, and mechanical stress on intraocular structures. The eight-chop technique was developed to address these specific challenges by mechanically dividing the lens nucleus into eight small fragments prior to emulsification [

11]. Unlike conventional prechop techniques, which typically divide the nucleus into four sections, the eight-chop technique consistently achieves eight-piece nuclear fragmentation using specialized instruments designed for precise and controlled mechanical splitting. This approach allows subsequent phacoemulsification and aspiration to be performed efficiently at the iris plane with reduced ultrasound energy and fluidics, thereby potentially minimizing corneal endothelial damage and intraoperative complications.

In eyes with white cataracts, successful completion of continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis (CCC) is a critical initial step, which requires adequate staining and visualization of the anterior lens capsule [

6,

12]. The use of brilliant blue G (BBG) has been shown to improve capsular visualization and to enable complete capsulorhexis without evidence of ocular toxicity in experimental models [

13]. However, previous clinical studies involving eyes with white cataracts have primarily employed trypan blue for anterior capsule staining, and the use of BBG in this setting has not been reported [

1,

4]. Thus, the clinical applicability of BBG for anterior capsule staining in eyes with white cataracts remains to be elucidated.

Although the eight-chop technique has been reported to be effective for hard cataracts [

11,

14], evidence regarding its performance specifically in white cataracts remains limited. Moreover, few studies have systematically evaluated intraoperative efficiency, corneal endothelial outcomes, intraocular pressure changes, and visual recovery in white cataracts according to intraoperative nuclear hardness. Given that nuclear hardness is a major determinant of surgical difficulty and postoperative outcomes, such stratified analyses are essential for accurately assessing the clinical value of surgical techniques in this setting. Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to evaluate the safety and efficacy of the eight-chop technique in eyes with white cataracts by analyzing intraoperative parameters, corneal endothelial cell density and morphology, intraocular pressure, visual outcomes, and surgical complications. Furthermore, outcomes were compared according to intraoperatively assessed nuclear hardness to clarify the applicability of the eight-chop technique across a wide spectrum of lens hardness in white cataracts.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Considerations

This retrospective, single-center, single-surgeon, single-arm observational study included eyes of patients with white cataracts who underwent phacoemulsification and posterior chamber intraocular lens (IOL) implantation between January 4, 2010, and March 25, 2025. The study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sato Eye Clinic (the approval number: 20091101). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to enrollment. Brilliant Blue G (BBG), which has been approved for human intraocular use in the European Union and is currently under regulatory review by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare in Japan, was used at a concentration of 0.025% for anterior capsule staining in the present study. Because the study was initiated on January 4, 2010, BBG was permitted for use at that time with approval from the institutional review board, which was obtained prior to patient enrollment.

2.2. Study Population

Patients who presented to our institution with white cataracts were enrolled in this study. In this study, white cataract was defined as a cataract in which the entire lens appeared white and opaque on slit-lamp examination, with absent or markedly reduced red reflex. Eyes with corneal disease or corneal opacity, uveitis, a history of ocular trauma, or previous intraocular surgery were excluded from the study.

2.3. Preoperative Assessment

All patients underwent comprehensive preoperative ophthalmic examinations. The preoperative assessment included slit-lamp biomicroscopy and fundus examination. Best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was measured using a Snellen visual acuity chart, and intraocular pressure (IOP) was measured using standard tonometric methods. Corneal endothelial cell density (CECD, cells/mm²), central corneal thickness (CCT), the coefficient of variation in cell size (CV), and the percentage of hexagonal cells (PHC) were evaluated using a non-contact specular microscope (EM-3000; Topcon Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Axial length and anterior chamber depth were assessed using a swept-source optical coherence tomography biometer with a wavelength of 1060 nm (OA-2000; TOMEY, Tokyo, Japan) when available. In earlier cases, axial length was measured using other commercially available biometry devices, and anterior chamber depth was not consistently assessed in all patients.

2.4. Classification of Nuclear Hardness

The hardness of the lens nucleus was assessed intraoperatively by the surgeon based on the Emery classification [

15]. Because the lens nucleus in white cataracts cannot be evaluated preoperatively, nuclear hardness was classified according to intraoperative findings. After completion of continuous curvilinear capsulorrhexis (CCC) and aspiration of the emulsified lens material, an eight-chopper was inserted into the exposed lens nucleus, and its color and hardness were evaluated.

2.5. Surgical Technique

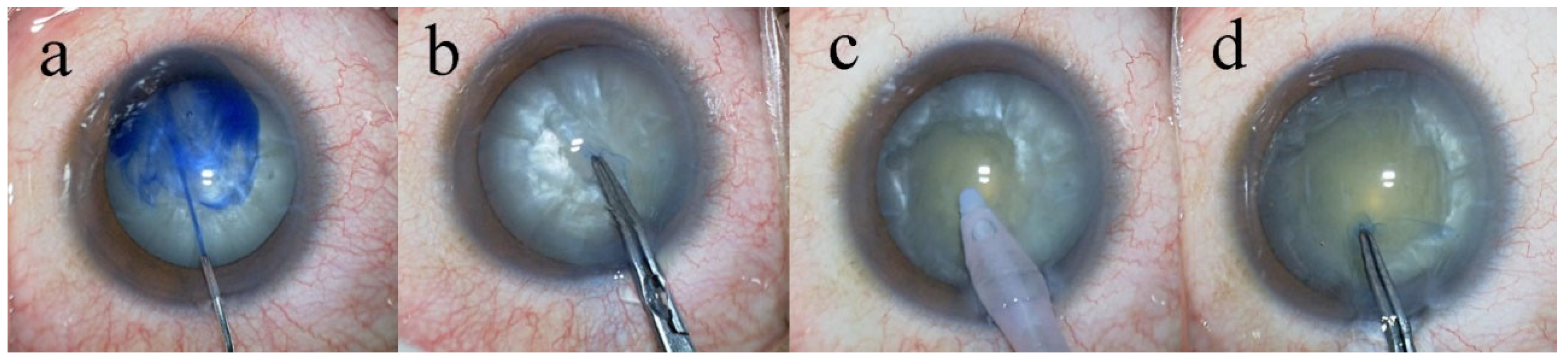

All surgeries were performed by a single surgeon (T.S.) who was fully experienced in the eight-chop technique, following the same standardized surgical protocol. Phacoemulsification was performed using the Centurion® Vision System (Alcon Laboratories, Inc., Fort Worth, TX, USA). All procedures were recorded using a video camera (MKC-704KHD; Ikegami Tsushinki Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The eight-chop technique was performed using an Eight-chopper II (SP-8402; ASICO, Westmont, IL, USA) and a Lance chopper (SP-9989; ASICO, Westmont, IL, USA). A 3.0-mm temporal clear corneal incision was created using a steel keratome. In all cases, Brilliant Blue G (BBG; 0.025%) was used to enhance visualization of the anterior capsule (

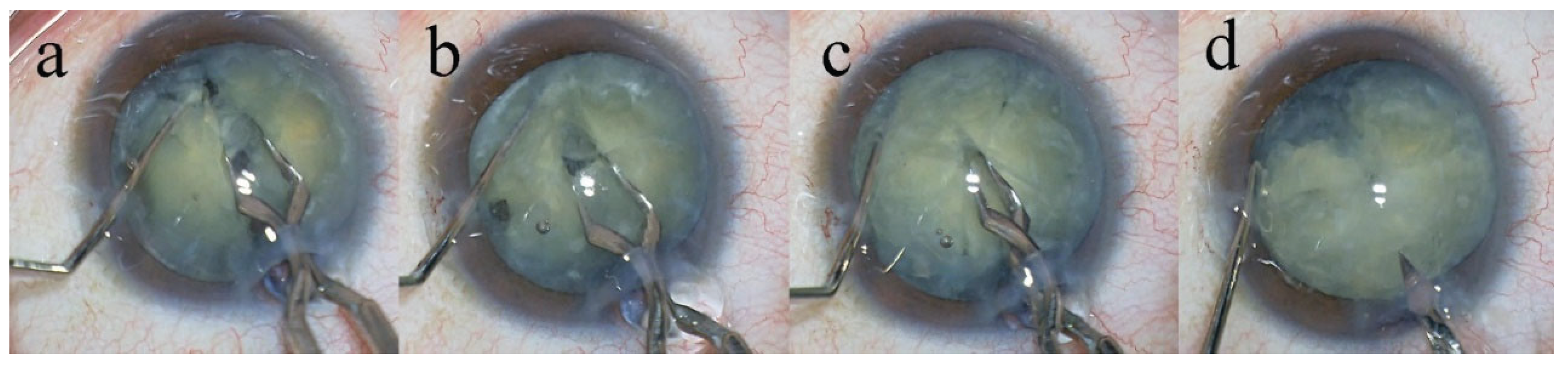

Figure 1). Anterior capsule staining was confirmed by video recordings in each case. After intentionally creating a small continuous curvilinear capsulorrhexis (CCC), the capsulorrhexis was subsequently enlarged to a final diameter of 6.2–6.5 mm using a two-step CCC technique. Hydrodissection was performed using a 27-gauge cannula (AMO Japan, Inc., Tokyo, Japan). The lens nucleus was mechanically divided into eight segments using the Eight-chopper II in 18 cases and the Lance chopper in 87 cases (

Figure 2). In eyes with Grade III or IV nuclear hardness, an additional side-port incision was created using a 23-gauge microvitreoretinal knife at approximately 90° from the main corneal incision, through which a sustainer was inserted. After removal of cortical material from the capsular bag using an irrigation–aspiration tip, a viscoelastic agent was injected, and a foldable posterior chamber intraocular lens (Acrysof

® MN60AC; Alcon Laboratories, Inc., Fort Worth, TX, USA) with polymethyl methacrylate haptics was implanted into the capsular bag using an injector system. Residual viscoelastic material was then thoroughly aspirated. At the end of surgery, moxifloxacin (0.5 mg/mL) was injected into the anterior chamber

2.6. Postoperative Examinations

Intraoperative outcome measures included surgical time (minutes), ultrasound time (seconds), aspiration time (minutes), cumulative dissipated energy (CDE), total volume of irrigation fluid used (mL), and the incidence of intraoperative complications. Surgical time was defined as the duration from the initiation of the corneal incision to the completion of viscoelastic material removal. Postoperative examinations were performed on postoperative days 1 and 2, and at 1, 3, 7, and 19 weeks after surgery. Postoperative outcome measures included best-corrected visual acuity, intraocular pressure, and corneal endothelial cell density. For the purposes of analysis in this study, data obtained at 7 and 19 weeks postoperatively were used.

2.7. Handling of Missing Data and Bilateral Cases

Because this was a retrospective study, postoperative data were missing for some eyes. The primary reasons for missing data were loss to follow-up or the inability to obtain corneal endothelial cell measurements. Therefore, statistical analyses were performed using a complete-case analysis approach, and no imputation of missing values was conducted. A total of 12 eyes were derived from bilateral cases. These eyes accounted for a small proportion of the overall study population, and no patient contributed more than two eyes to the dataset. Given the limited number of bilateral cases and the predominance of unilateral observations, the potential impact of inter-eye correlation on the overall estimates was considered minimal. Therefore, no statistical adjustment for within-subject correlation, such as the use of mixed-effects models or generalized estimating equations, was applied in the analyses.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.5.2; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages. Comparisons among groups stratified by nuclear hardness were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables. When overall significance was detected, post hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted using the Tukey–Kramer method. For comparisons of categorical variables, the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test was applied, as appropriate. Longitudinal changes in postoperative outcomes were evaluated by comparing values at each postoperative time point. Because this was a retrospective study and postoperative data were missing for some eyes, all analyses were conducted using a complete-case analysis approach without imputation of missing values. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical tests were two-tailed.

3. Results

During the observation period from January 4, 2010, to March 25, 2025, a total of 12,642 cataract surgeries were performed at our institution. Among these, 126 eyes were diagnosed with white cataracts. Of the 126 eyes, 20 eyes were excluded due to loss to follow-up, and 1 eye was excluded because of progression to lens dislocation. Consequently, data from 105 eyes were included in the final analysis. Among the 105 eyes with white cataracts, 22 eyes were from patients with diabetes mellitus. Postoperatively, 4 eyes were excluded from visual acuity analyses due to diabetic retinopathy, 3 eyes due to age-related macular degeneration, and 1 eye due to branch retinal vein occlusion. All other missing data were attributable to lack of patient follow-up or inability to perform the required examinations.

3.1. Preoperative Characteristics and Intraoperative Parameters by Lens Hardness

Preoperative patient characteristics and intraoperative parameters are summarized according to lens hardness (

Table 1). The number of eyes was 13 in the Grade I–II group, 28 in the Grade III group, and 64 in the Grade IV group. The mean age increased significantly with lens hardness, being 44.4 ± 12.0 years in the Grade I–II group, 60.1 ± 11.5 years in the Grade III group, and 73.1 ± 9.0 years in the Grade IV group (p < 0.001). There was no significant difference in sex distribution among the groups (male: 61.5%, 67.9%, and 46.9%, respectively; p = 0.152). Anterior chamber depth (ACD) did not differ significantly among the groups (p = 0.269), whereas axial length decreased significantly with increasing lens hardness (Grade I–II: 24.7 ± 0.9 mm; Grade III: 24.1 ± 1.2 mm; Grade IV: 23.1 ± 1.0 mm; p < 0.001). Lens hardness itself differed significantly among the groups (1.3 ± 0.5, 3.3 ± 0.3, and 4.3 ± 0.3, respectively; p < 0.001). Regarding intraoperative parameters, both operative time and phacoemulsification time (Phaco time) increased significantly with lens hardness (operative time: 8.9 ± 4.3, 10.1 ± 4.4, 12.8 ± 4.4 min; p = 0.003; Phaco time: 5.8 ± 6.5, 18.9 ± 13, 34 ± 14.6 s; p < 0.001). Aspiration time and volume of fluid used did not differ significantly among the groups (p = 0.108 and p = 0.32, respectively). Cumulative Dissipated Energy (CDE) increased significantly with lens hardness (1.6 ± 2, 7.4 ± 5.5, 15.3 ± 6.4, respectively; p < 0.001).

3.2. Corneal Endothelial Cell Density Changes by Lens Hardness

Preoperative and postoperative corneal endothelial cell density (CECD) values are shown according to lens hardness (

Table 2). Preoperatively, the mean CECD was 2585.9 ± 403.6 cells/mm² in the Grade I–II group, 2676 ± 180.4 cells/mm² in the Grade III group, and 2627.2 ± 269.6 cells/mm² in the Grade IV group, with no significant difference among the groups (p = 0.593). At 7 weeks postoperatively, CECD values were 2491.8 ± 322.3, 2598.8 ± 241.5, and 2421.6 ± 489.3 cells/mm² in the Grade I–II, III, and IV groups, respectively. The mean percentage decrease from preoperative values was -2.7 ± 11.5% in Grade I–II, -1.6 ± 7.1% in Grade III, and -6.4 ± 17.4% in Grade IV, with no significant difference among the groups (p = 0.242 for CECD, p = 0.389 for % decrease). At 19 weeks postoperatively, CECD values were 2539.3 ± 110.6, 2629.1 ± 235.6, and 2433.4 ± 418.1 cells/mm², with mean percentage decreases of -0.9 ± 6.8%, -0.5 ± 5.7%, and -6.7 ± 13.5% in the Grade I–II, III, and IV groups, respectively. No statistically significant differences were observed among the groups (p = 0.238 for CECD, p = 0.105 for % decrease).

3.3. Corneal Endothelial Parameters According to Lens Hardness

The pre- and postoperative central corneal thickness (CCT), coefficient of variation of cell size (CV), and percentage of hexagonal cells (PHC) according to lens hardness are shown in

Table 3. Preoperatively, CCT was 550.0 ± 46.2 μm in the Grade I–II group, 544.0 ± 49.0 μm in the Grade III group, and 541.1 ± 41.9 μm in the Grade IV group, with no significant differences among the groups (p = 0.820). At 7 weeks postoperatively, CCT was 551.8 ± 45.2, 563.2 ± 60.9, and 552.3 ± 56.6 μm, and at 19 weeks postoperatively, 518.3 ± 20.9, 536.2 ± 44.2, and 542.6 ± 45.7 μm, with no significant differences among the groups at either time point. Preoperative CV was 48.3 ± 9.6 in the Grade I–II group, 39.8 ± 4.9 in the Grade III group, and 44.3 ± 10.7 in the Grade IV group, showing a significant difference among groups (p = 0.023). At 7 weeks postoperatively, CV was 50.4 ± 10.3, 39.9 ± 5.7, and 43.9 ± 8.2, with significant differences (p = 0.001), whereas at 19 weeks postoperatively, CV was 41.6 ± 5.7, 39.7 ± 8.1, and 39.5 ± 5.7, and the differences were no longer significant (p = 0.686). Preoperative PHC was 39.0 ± 10.6% in the Grade I–II group, 44.3 ± 8.3% in the Grade III group, and 49.8 ± 54.2% in the Grade IV group, with no significant differences among groups (p = 0.665). At 7 weeks postoperatively, PHC was 39.0 ± 8.3%, 45.2 ± 8.9%, and 41.3 ± 8.3%, and at 19 weeks postoperatively, 39.3 ± 7.2%, 46.6 ± 7.8%, and 43.4 ± 7.9%, with no significant differences at either time point.

3.4. Intraocular Pressure Changes According to Lens Hardness

The mean intraocular pressure (IOP) and percentage decrease from baseline according to lens hardness are shown in

Table 4. Preoperatively, the mean IOP was 13.9 ± 2.0 mmHg in the Grade I–II group, 13.7 ± 2.3 mmHg in the Grade III group, and 13.6 ± 2.5 mmHg in the Grade IV group, with no significant differences among the groups (p = 0.948). At 7 weeks postoperatively, the mean IOP was 14.0 ± 1.5, 13.0 ± 2.4, and 12.2 ± 2.0 mmHg, with significant differences among the groups (p = 0.018). The percentage decrease from baseline IOP was -3.0 ± 11.6% in the Grade I–II group, 4.8 ± 12.0% in the Grade III group, and 9.7 ± 14.0% in the Grade IV group, showing a significant difference (p = 0.013). At 19 weeks postoperatively, mean IOP was 14.8 ± 1.6, 12.9 ± 2.0, and 12.0 ± 2.1 mmHg (p = 0.003), and the percentage decrease from baseline was -7.5 ± 13.3%, 5.5 ± 7.6%, and 10.0 ± 15.3%, respectively, with significant differences among groups (p = 0.007). These results indicate that higher lens hardness was associated with greater postoperative IOP reduction.

3.5. Best-Corrected Visual Acuity According to Lens Hardness

The pre- and postoperative best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) in logMAR according to lens hardness are shown in

Table 5. Preoperatively, BCVA was 1.935 ± 0.408 in the Grade I–II group, 2.120 ± 0.293 in the Grade III group, and 2.183 ± 0.334 in the Grade IV group, with no significant differences among the groups (p = 0.107). At 7 weeks postoper-atively, BCVA was -0.079 ± 0.001, -0.041 ± 0.053, and -0.014 ± 0.091, showing a significant difference among groups (p = 0.022). At 19 weeks postoperatively, BCVA was -0.079 ± 0.001, -0.036 ± 0.050, and -0.019 ± 0.084, with no significant differences among groups (p = 0.057). These results suggest that differences in BCVA according to lens hardness were observed in the early postoperative period but tended to disappear over the long term.

4. Complications and Additional Procedures during Surgerys

In this study, posterior capsule rupture was observed in 2 of 105 eyes. In 7 eyes, a complete con-tinuous curvilinear capsulorrhexis (CCC) could not be achieved. Iris retractor hooks were used in 25 eyes. No cases of lens nucleus drop occurred during surgery.

4. Discussion

White cataract represents one of the most technically demanding conditions in phacoemulsification surgery because of the absence of a red reflex, increased intralenticular pressure, frequent liquefaction of cortical material, and the presence of a hard and brittle lens nucleus [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. These characteristics increase the risk of capsulorhexis-related complications, zonular stress, posterior capsule rupture, and excessive ultrasound energy delivery [

1,

3,

4]. In this retrospective single-surgeon study, we evaluated the intraoperative efficiency and postoperative outcomes of the eight-chop technique in eyes with white cataract and demonstrated that this approach allows safe and efficient phacoemulsification with favorable visual and endothelial outcomes. In the present study, the eight-chop technique achieved short operative time, reduced ultrasound exposure, low cumulative dissipated energy (CDE), and limited irrigation fluid usage, even in eyes with advanced nuclear hardness [

4,

16]. Surgical efficiency is particularly important in white cataract because prolonged manipulation and excessive energy delivery are known to increase the risk of endothelial damage and intraocular complications [

1,

2,

10,

17,

18]. Although direct comparisons of operative time among studies are difficult due to differences in surgical definitions and reporting, the operative time observed in this study was comparable to or shorter than those reported in previous studies using alternative techniques for dense cataracts [

8,

10]. Importantly, the eight-chop technique separates nuclear fragmentation from phacoemulsification and aspiration. This conceptual separation allows the surgeon to complete nuclear division mechanically before ultrasound application, thereby minimizing the need for prolonged phaco power [

11]. In contrast, techniques such as divide-and-conquer or phaco-chop require simultaneous nuclear cracking and emulsification, which may increase intraocular stress, particularly in eyes with fragile capsules and weakened zonules, as frequently encountered in white cataract [

2,

3,

7].

Corneal endothelial cell density (CECD) is widely recognized as an integrated indicator of intraocular surgical stress [

19,

20,

21,

22,

23]. Previous reports have shown that phacoemulsification in dense or white cataracts is associated with greater endothelial cell loss than routine cataract surgery [

1,

2,

10,

16]. Reported endothelial cell loss rates in dense cataracts vary widely, reflecting differences in surgical technique, ultrasound parameters, and case complexity. In the present study, postoperative endothelial cell loss was minimal and not statistically significant compared with baseline values. This finding suggests that the eight-chop technique effectively limits ultrasound energy delivery and reduces mechanical and fluidic stress on the corneal endothelium. The ability to divide the nucleus into eight small, manageable segments facilitates rapid emulsification at the iris plane, thereby increasing the distance between the ultrasound tip and the corneal endothelium. Another factor contributing to endothelial safety is the reduced volume of irrigation fluid used during surgery. Excessive fluid flow can induce turbulence within the anterior chamber, leading to endothelial trauma [

21,

24,

25,

26]. The low fluid usage observed in this study reflects the efficiency of the eight-chop technique and may partially explain the favorable endothelial outcomes.

In the present study, brilliant blue G (BBG) at a concentration of 0.025% was used routinely for anterior capsule staining in eyes with white cataracts. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first clinical study to apply BBG in this context, as previous studies of white cataracts have relied exclusively on trypan blue for visualization of the anterior capsule [

1,

27,

28]. BBG has been extensively studied as a protein-staining dye and has demonstrated superior safety profiles compared with trypan blue and indocyanine green in experimental and clinical settings [

13,

29,

30,

31]. Previous experimental studies have shown that this concentration provides sufficient anterior capsule staining with minimal toxicity to corneal endothelial cells, and clinical studies in vitreoretinal surgery have further supported its relative safety [

13,

29,

30]. In the present study, BBG provided adequate capsular visualization to achieve complete continuous curvilinear capsulorhexis without intraoperative complications attributable to dye toxicity. The stable postoperative endothelial cell counts observed are consistent with previous findings and support the safety and clinical utility of BBG for anterior capsule staining in white cataract surgery.

Postoperative best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) improved significantly across all nuclear hardness grades. Although eyes with harder nuclei tended to show slightly delayed visual recovery, BCVA at later postoperative time points did not differ significantly among groups. These results indicate that the eight-chop technique provides consistent visual rehabilitation even in eyes with severe lens opacification. Several eyes were excluded from visual acuity analysis due to coexisting retinal diseases, including diabetic retinopathy and age-related macular degeneration. This exclusion allowed a more accurate assessment of surgery-related visual outcomes and strengthens the interpretation that postoperative visual improvement was primarily attributable to the surgical technique rather than retinal pathology.

A reduction in intraocular pressure (IOP) following cataract surgery has been reported in both glaucomatous and nonglaucomatous eyes [

32,

33]. In the present study, postoperative IOP showed a modest decrease at both 7 and 19 weeks; however, these changes did not reach statistical significance. Although the sample size may have limited the power to detect small IOP changes, the trend toward IOP reduction suggests that the eight-chop technique does not adversely affect aqueous outflow and may be suitable for eyes with concomitant glaucoma. Further prospective studies are warranted to clarify this potential benefit.

Despite the technical challenges inherent to white cataract surgery, intraoperative complications were infrequent in this study. Posterior capsule rupture occurred in only two eyes, and no cases of nuclear drop were observed. Although incomplete capsulorhexis was encountered in several cases, the two-step capsulorhexis technique combined with BBG staining allowed controlled enlargement of the capsular opening without progression to severe complications. The use of iris retractor hooks in selected cases facilitated adequate surgical exposure and contributed to intraoperative safety [

34]. These findings highlight the importance of appropriate adjunctive techniques when managing white cataracts.

Compared with conventional techniques, the eight-chop method offers several theoretical and practical advantages in white cataract surgery. By enabling complete mechanical segmentation of the nucleus prior to emulsification, it minimizes zonular stress and posterior capsule movement [

14,

35]. The use of specialized instruments, such as the Eight-chopper II and Lance chopper, allows precise and controlled nuclear division even in extremely hard nuclei [

11]. Furthermore, dividing the nucleus into eight segments reduces the size of each fragment, facilitating efficient aspiration with minimal ultrasound power. This feature is particularly advantageous in eyes with compromised corneal endothelium or shallow anterior chambers [

36].

This study has several limitations. First, its retrospective design may introduce selection bias. Second, the absence of a control group undergoing alternative surgical techniques limits direct comparisons. Third, although a small number of eyes from bilateral cases were included, no adjustment for inter-eye correlation was performed. However, the proportion of such cases was minimal relative to the total sample size, and the potential impact on statistical inference is likely negligible. Finally, surgical outcomes may reflect the experience of a single surgeon highly familiar with the eight-chop technique, which may limit generalizability. Nevertheless, this also represents a strength, as it ensures procedural consistency and reduces confounding variability.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, the eight-chop technique enables safe and efficient phacoemulsification in eyes with white cataract. The technique achieves favorable intraoperative efficiency, preserves corneal endothelial integrity, and provides excellent visual outcomes with a low rate of complications. These findings support the eight-chop technique as a valuable surgical option for the management of white cataract, particularly in cases with hard nuclei and increased surgical risk.

Author Contributions

Language editing tools were used solely to improve grammar and readability. All scientific content, data interpretation, statistical analyses, and conclusions were entirely conducted and verified by the author.

Funding

This study received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Sato Eye Clinic (approval number 20091101, approval date: November 1, 2009).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants for cataract surgery and for the use of their clinical data for research and publication.

Data Availability Statement

The anonymized dataset generated and analyzed during the present study is available in the supplementary materials (Supplementary Dataset 1). No personally identifiable information is included, in accordance with ICMJE data sharing standards.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| IOL |

Intraocular lens |

| BBG |

Brilliant Blue G |

| BCVA |

Best-corrected visual acuity |

| IOP |

Intraocular pressure |

| CECD |

Corneal endothelial cell density |

| CCT |

Central corneal thickness |

| CV |

Coefficient of variation |

| PHC |

Percentage of hexagonal cells |

| ACD |

Anteior chamber depth |

| CDE |

Cumulative dissipated energy |

| ANOVA |

Analysis of variance |

| CCC |

Continuous curvilinear capsulorrhexis |

| logMAR |

Logarithm of the minimum angle of resolution |

References

- Jacob, S.; Agarwal, A.; Agarwal, A.; Agarwal, S.; Chowdhary, S.; Chowdhary, R.; Bagmar, A.A. Trypan blue as an adjunct for safe phacoemulsification in eyes with white cataract. J Cataract Refract Surg 2002, 28, 1819–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasavada, A.; Singh, R.; Desai, J. Phacoemulsification of white mature cataracts. J Cataract Refract Surg 1998, 24, 270–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brazitikos, P.D.; Tsinopoulos, I.T.; Papadopoulos, N.T.; Fotiadis, K.; Stangos, N.T. Ultrasonographic classification and phacoemulsification of white senile cataracts. Ophthalmology 1999, 106, 2178–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermisş, S.S.; Oztürk, F.; Inan, U.U. Comparing the efficacy and safety of phacoemulsification in white mature and other types of senile cataracts. Br J Ophthalmol 2003, 87, 1356–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Titiyal, J.S.; Kaur, M.; Shaikh, F.; Goel, S.; Bageshwar, L.M.S. Real-time intraoperative dynamics of white cataract-intraoperative optical coherence tomography-guided classification and management. J Cataract Refract Surg 2020, 46, 598–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, V.A.C.; Rosatelli Neto, J.M.; Moscovici, B.K.; Rabelo, D.F.O.; Sano, V.A.; Hida, R.Y. Automated Capsular Decompression to Avoid Argentinian Flag Sign in Intumescent Cataract. Clin Ophthalmol 2024, 18, 1915–1920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakrabarti, A.; Singh, S. Phacoemulsification in eyes with white cataract. J Cataract Refract Surg 2000, 26, 1041–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatesh, R.; Tan, C.S.; Sengupta, S.; Ravindran, R.D.; Krishnan, K.T.; Chang, D.F. Phacoemulsification versus manual small-incision cataract surgery for white cataract. J Cataract Refract Surg 2010, 36, 1849–1854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Tang, Q.; Yu, F.; Cai, X.; Lu, F. Consecutive drilling combined with phaco chop for full thickness segmentation of very hard nucleus in coaxial microincisional cataract surgery. BMC Ophthalmol 2019, 19, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, V.W.; Lai, T.Y.; Lee, G.K.; Lam, P.T.; Lam, D.S. Safety and efficacy of micro-incisional cataract surgery with bimanual phacoemulsification for white mature cataract. Ophthalmologica 2007, 221, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T. Efficacy and safety of the eight-chop technique in phacoemulsification for patients with cataract. J Cataract Refract Surg 2023, 49, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ungricht, E.L.; Culp, C.; Qu, P.; Harris, J.T.; Brintz, B.J.; Mamalis, N.; Olson, R.J.; Werner, L. Effect of phacoemulsification fluid flow on the corneal endothelium: experimental study in rabbit eyes. J Cataract Refract Surg 2022, 48, 481–486. [Google Scholar]

- Hisatomi, T.; Enaida, H.; Matsumoto, H.; Kagimoto, T.; Ueno, A.; Hata, Y.; Kubota, T.; Goto, Y.; Ishibashi, T. Staining ability and biocompatibility of brilliant blue G: preclinical study of brilliant blue G as an adjunct for capsular staining. Arch Ophthalmol 2006, 124, 514–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T. Minimizing Endothelial Cell Loss in Hard Nucleus Cataract Surgery: Efficacy of the Eight-Chop Technique. J Clin Med 2025, 14, 2576. [Google Scholar]

- Emery, J.M.; Little, J.H. Patient selection. In Phacoemulsification and aspiration of cataracts; Surgical Techniques, Complications, and Results; Emery, J.M., Little, J.H., Eds.; CV Mosby: St Louis, MO, USA, 1979; pp. 45–48. [Google Scholar]

- Vajpayee, R.B.; Bansal, A.; Sharma, N.; Dada, T.; Dada, V.K. Phacoemulsification of white hypermature cataract. J Cataract Refract Surg 1999, 25, 1157–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Wang, B.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Yang, H.; Wu, R.; Cui, Y. Cataract Surgery in Eyes with Microphthalmos and/or Uveal Coloboma. Ophthalmic Res 2025, 68, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Chen, L.L.; Li, D.K. An exploration of safe and efficient nucleus fragmentation strategies for femtosecond laser-assisted cataract surgery in short axial length patients. BMC Ophthalmol 2024, 24, 550. [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay, S.; Sharma, P.; Chouhan, J.K.; Goyal, R. Comparative evaluation of modified crater (endonucleation) chop and conventional crater chop techniques during phacoemulsification of hard nuclear cataracts: a randomized study. Indian J Ophthalmol 2022, 70, 794–798. [Google Scholar]

- Akansha; Yadav, R.S. Comparative assessment of the corneal endothelium following phacoemulsification surgery in patients with type II diabetes and nondiabetes. Saudi J Ophthalmol 2025, 39, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Vasavada, V.; Agrawal, D.; Vasavada, S.A.; Vasavada, A.R.; Yagnik, J. Intraoperative Performance and Early Postoperative Outcomes Following Phacoemulsification With Three Fluidic Systems: A Randomized Trial. J Refract Surg 2024, 40, e304–e312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, N.S.; Ong, K. Risk factors for corneal endothelial cell loss after phacoemulsification. Taiwan J Ophthalmol 2024, 14, 83–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hong, J.; Chen, X. Comparisons of the clinical outcomes of Centurion(®) active fluidics system with a low IOP setting and gravity fluidics system with a normal IOP setting for cataract patients with low corneal endothelial cell density. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023, 10, 1294808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Nanaiah, S.G.; Kummelil, M.K.; Nagappa, S.; Shetty, R.; Shetty, B.K. Effect of fluidics on corneal endothelial cell density, central corneal thickness, and central macular thickness after phacoemulsification with torsional ultrasound. Indian J Ophthalmol 2015, 63, 641–644. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.Y.; Kim, H.; Jun, I.; Kim, T.I.; Seo, K.Y. Effect and safety of pressure sensor-equipped handpiece in phacoemulsification system. Korean J Ophthalmol 2023, 37, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Tao, J.; Yu, X.; Diao, W.; Bai, H.; Yao, L. Safety and prognosis of phacoemulsification using active sentry and active fluidics with different IOP settings - a randomized, controlled study. BMC Ophthalmol 2024, 24, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balyan, M.; Jain, A.K.; Malhotra, C.; Ram, J.; Dhingra, D. Achieving successful capsulorhexis in intumescent white mature cataracts to prevent Argentinian flag sign - A new multifaceted approach to meet the challenge. Indian J Ophthalmol 2021, 69, 1398–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelmotaal, H.; Abdelazeem, K.; Hussein, M.S.; Omar, A.F.; Ibrahim, W. Safety of Trypan Blue Capsule Staining to Corneal Endothelium in Patients with Diabetic Retinopathy. J Ophthalmol 2019, 2019, 4018739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueno, A.; Hisatomi, T.; Enaida, H.; Kagimoto, T.; Mochizuki, Y.; Goto, Y.; Kubota, T.; Hata, Y.; Ishibashi, T. Biocompatibility of brilliant blue G in a rat model of subretinal injection. Retina 2007, 27, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baba, T.; Hagiwara, A.; Sato, E.; Arai, M.; Oshitari, T.; Yamamoto, S. Comparison of vitrectomy with brilliant blue G or indocyanine green on retinal microstructure and function of eyes with macular hole. Ophthalmology 2012, 119, 2609–2615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayama, K.; Sato, T.; Karasawa, Y.; Sato, S.; Ito, M.; Takeuchi, M. Phototoxicity of indocyanine green and Brilliant Blue G under continuous fluorescent illumination on cultured human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2012, 53, 7389–7394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poley, B.J.; Lindstrom, R.L.; Samuelson, T.W.; Schulze, R., Jr. Intraocular pressure reduction after phacoemulsification with intraocular lens implantation in glaucomatous and nonglaucomatous eyes: Evaluation of a causal relationship between the natural lens and open-angle glaucoma. J Cataract Refract Surg 2009, 35, 1946–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Walland, M.; Thomas, A.; Mengersen, K. Lowering of Intraocular Pressure After Phacoemulsification in Primary Open-Angle and Angle-Closure Glaucoma: A Bayesian Analysis. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Phila) 2016, 5, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, T. Eight-chop technique in phacoemulsification using iris hooks for patients with cataracts and small pupils. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 7298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, T. Cataract Surgery in Pseudoexfoliation Syndrome Using the Eight-Chop Technique. J Pers Med 2025, 15, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, T. Corneal endothelial cell loss in shallow anterior chamber eyes after phacoemulsification using the eight-chop technique. J Clin Med 2025, 14, 3045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).