Submitted:

15 December 2025

Posted:

16 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Motivation and Conceptual Framework

2.2. Pendulum-Based Mounting Mechanism for Seismic Path Tuning

3. Results

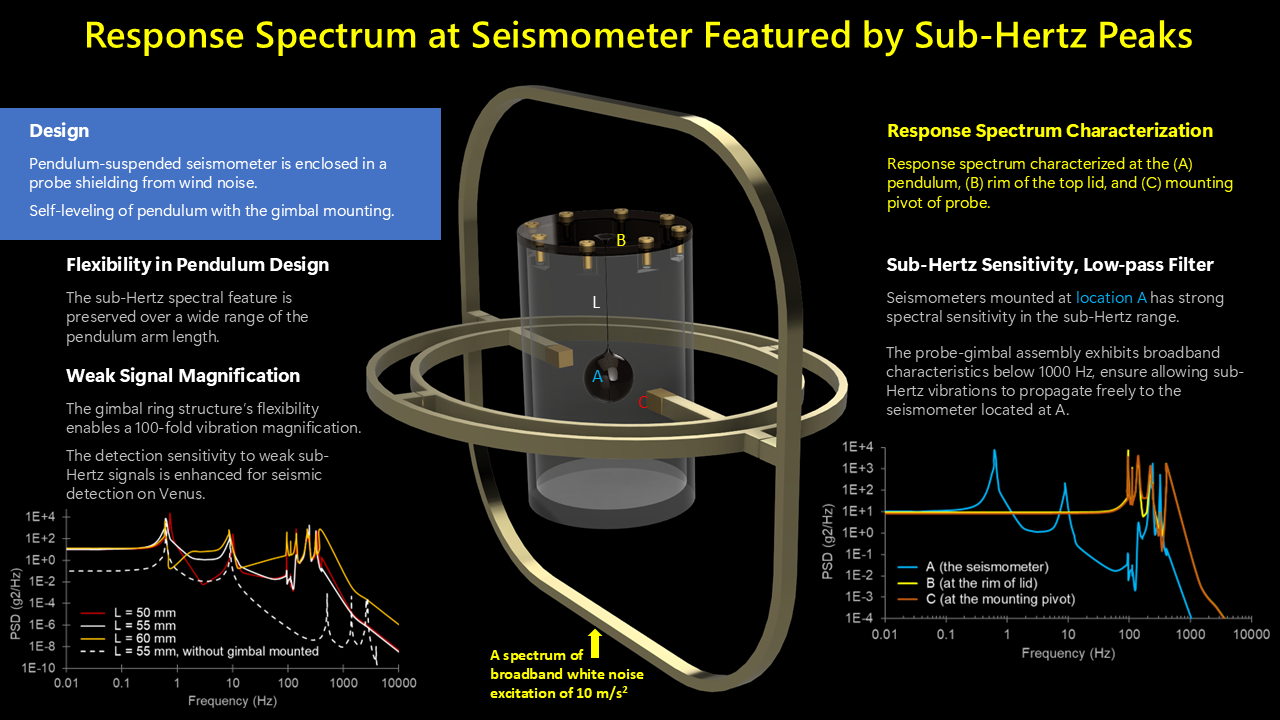

3.1. Spectral Response of Pendulum-Based Passive Mounting Mechanism

3.1.1. PSD at Pendulum Bob

3.1.2. PSD Response at the Mounting Structures (Locations B, C, and D)

3.1.3. Transmissibility (Transfer Function)

3.2. Minimum Level of Detection

3.3. Maximum Number of Annual Surface Quake Detectable

4. Discussions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ADC | Analog-to-digital conversion |

| SNR | Signal-to-noise ratio |

| ASD | Amplitude spectrum density |

| PSD | Power spectrum density |

| RMS | Root-mean-squared |

| LLISSE | Long Lived In-situ Solar System Explorer |

| SEIS | Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure |

| SAEVe | Seismic and Atmospheric Exploration of Venus |

References

- Herrick, R.R.; Hensley, S. Surface changes observed on a Venusian volcano during the Magellan mission. Science (1979) 2023, 379(6638), 1205–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lognonné, P.; Johnson, C.L. Planetary Seismology. Treatise on Geophysics: Second Edition 2015, 10(4), 65–120. [Google Scholar]

- Kremic, T.; Ghail, R.; et al. Long-duration Venus lander for seismic and atmospheric science. Planet Space Sci. 2020, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnamoorthy, S.; Komjathy, A.; et al. Detection of Artificially Generated Seismic Signals Using Balloon-Borne Infrasound Sensors. Geophys Res Lett. 2018, 45(8), 3393–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, R.F.; van Zelst, I.; et al. Seismic Wave Detectability on Venus Using Ground Deformation Sensors, Infrasound Sensors on Balloons and Airglow Imagers. Earth and Space Science 2024, 11(11), e2024EA003670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panning, M.P.; Pike, W.T.; et al. On-Deck Seismology: Lessons from InSight for Future Planetary Seismology. J Geophys Res Planets 2020, 125(4), e2019JE006353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W.; Tkalčić, H.; et al. Spectral characteristics and implications of located low-frequency marsquakes and impact events from InSight SEIS observations. Physics of the Earth and Planetary Interiors 2025, 361, 107334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerdt, B. EPSC Abstracts: InSight’s Contributions to Planetary Seismology and Geophysics. Europlanet Science Congress 2022, 2022; 16, p. 773. [Google Scholar]

- Ksanfomaliti, L. V.; Zubkova, V.M.; et al. Microseisms at the VENERA-13 and VENERA-14 Landing Sites. Soviet Astronomy Letters 1982, 8, 241–2. [Google Scholar]

- Kremic, T.; Hunter, G.W. Long-Lived In-Situ Solar System Explorer (LLISSE) Potential Contributions to Solar System Exploration. Bulletin of the American Astronomical Society 2021, 53(4), e–id. 151. [Google Scholar]

- Lognonné, P.; Banerdt, W.B.; et al. SEIS: Insight’s Seismic Experiment for Internal Structure of Mars. Space Sci Rev. 2019, 215(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schon, K. Transfer behavior of linear systems, convolution and deconvolution. Power Systems 2019, 269–306. [Google Scholar]

- Murdoch, N.; Mimoun, D.; et al. Evaluating the Wind-Induced Mechanical Noise on the InSight Seismometers. Space Sci Rev. 2017, 211(1–4), 429–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdoch, N.; Alazard, D.; et al. Flexible Mode Modelling of the InSight Lander and Consequences for the SEIS Instrument. Space Sci Rev. 2018, 214(8), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stott, A.E.; Charalambous, C.; et al. The Site Tilt and Lander Transfer Function from the Short-Period Seismometer of InSight on Mars. Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America 2021, 111(6), 2889–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackerley, N. Principles of Broadband Seismometry. Encyclopedia of Earthquake Engineering 2015, 1941–70. [Google Scholar]

| Pendulum | |

|---|---|

| Arm length L (mm) Arm diameter (mm) Bob diameter (mm) |

50 - 71 0.4 30 |

| Cylindrical housing | |

| Diameter (mm) Height (mm) Wall thickness (mm) |

100 130 5 |

| Gimbal ring | |

| Ring’s cross-sectional area (mm2) Diameter Outer ring (mm) Middle ring (mm) Inner ring (mm) |

10 × 10 320 260 200 |

| Ring connector length Outer-middle (mm) Middle-inner (mm) Inner cylinder (mm) |

20 20 40 |

| Material | Ti6Al4V |

| Young’s modulus (GPa) Poisson’s ratio Density (g/cm3) |

110 0.30 4.45 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).