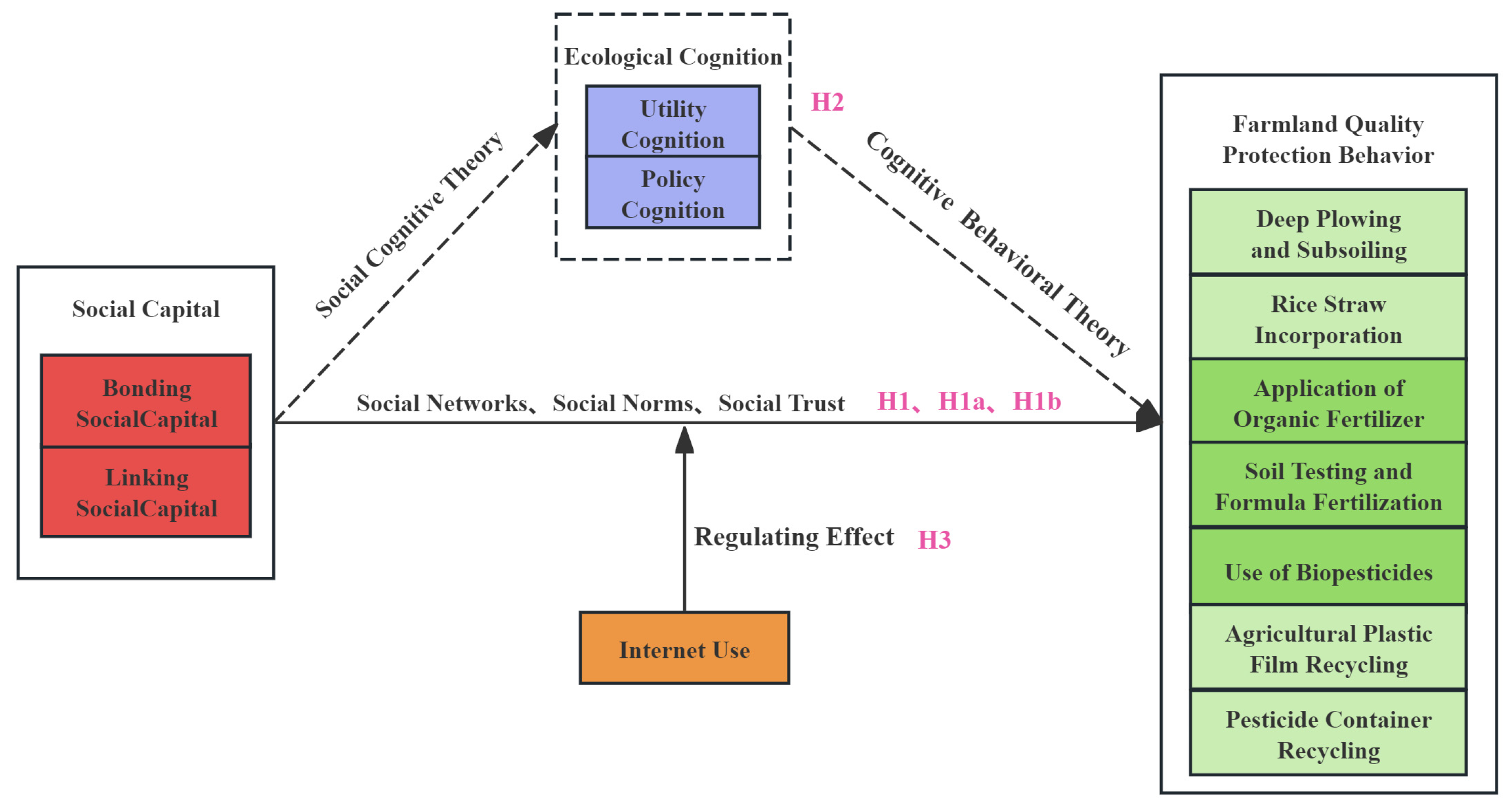

1. Introduction

Farmland is the cornerstone of agricultural production, and itself is also a crucial part of the world's ecological environment. Guaranteeing farmland security is hence the key to ensuring food security, social stability, and long-term development [

1]. But in the past few years, the world's farmlands have faced many threats to their degradation. Based on the data provided by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, the amount of fertilizer used globally has increased by 37% compared to that of the year 2000. This surge has brought along a string of problems that cause farmland quality to go down, soil acidification, lack of nutrients, and deterioration of farmland [

2], which are very dangerous to growing food and people's health all over the world. This issue is most serious in China, which is experiencing problems like underdeveloped agricultural infrastructure, lots of tiny pieces of land, and severe environmental pollution. In response, the Chinese government has made farmland protection a core, long-term national policy and developed, by far, the most rigorous system of modern farmland protection [

3].

At present, the protection of farmland in China has developed from protecting the quantity of farmland alone to a protection concept and method that focuses on protecting farmland quantity and quality, and even ecology, i.e., a three-dimensional integration of quantity, quality, and ecology with quality as the main focus [

4]. Higher quality farmland improves both the amount of grain produced and its consistency, and also makes the resources used in agriculture more efficient. It also serves as an important indicator of a healthy ecological environment. Nevertheless, Chinese farmland has long suffered from excessive input of chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Besides, the leftover plastic film of agriculture is creating more and more "white pollution", making the land poorer and poorer.

According to authoritative data, China's latest fertilizer application has reached 325.65kg/ha, which is 1.45 times the internationally acknowledged upper limit of 225kg/ha [

5]. The overall soil organic matter content is lower than 50% of the soil organic matter content of the same kind of soil in Europe. Additionally, the area of saline-alkaline farmland exceeds 6.67 million hectares, and the low- and medium-grade farmland accounts for more than two-thirds of the country's total area, with the soil being severely acidified [

6]. Occupation of good farmland in compensation for inferior land, industrial pollution, and farmland abandonment [

7]. China still faces tremendous pressure and a challenging task in protecting the quality of its farmland. Farmer is the micro-level subject of agricultural production and management; they are the most direct participants and stakeholders in protecting farmland quality. Thus, it is essential to study how to promote farmers' farmland quality protection behavior to protect farmland quality effectively and develop green agriculture.

Researchers in the current literature have investigated the effects of farmers' personal characteristics [

8], cognitive aspects [

9], household and operation characteristics [

10] on farmers' farmland quality protection behaviors or green production decisions. However, in actual agricultural production, Farmers' production decision-making is not a completely independent act; their behavioral intention and decision-making are often the result of the interaction with "other people" [

11]. Chinese rural society is characterized as an "acquaintance society" with factors such as kinship and geographical location serving as its foundation. The social network a farmer belongs to, daily social exchange activities, and the interaction between individuals have an impact on the individual's life and agricultural production decisions [

12]. In other words, social capital is a crucial factor that affects the agricultural production decisions of farmers. Social capital, as an "intangible" resource that relies on trust, is constructed via networks, governed by norms, and can be considered as a valuable asset for rural communities.

Some scholars have also conducted relevant research on the effect of social capital on farmers' protection of farmland quality and agricultural green production. Hunecke et al. believed social capital operates through three key mechanisms: 1) an Information Mechanism for the flow of information and knowledge, 2) a Trust Mechanism to reduce the risks and costs of cooperation, and 3) a Resource Mechanism to integrate necessary resources and mobilize social support. And these mechanisms facilitate the adoption of green production technologies together [

13]. Additionally, Läpple et al. Indicated that social capital is involved throughout the entire process by which farmers adopt green production technologies, sharing values and emotions, and becoming a bridge between policy support, personal attitude, and adoption behavior [

14]. Gao et al. considered that social capital can reduce the uncertainties and transaction costs associated with land transfer through access to information, reinforcement of trust-based norms, and provision of resource support. It can improve the stable expectations of long-term management of farmland, which can promote agricultural operators to use green production technologies [

15]. Adopting such technologies can reduce the pollution of farmland and improve the quality of the soil, which is a specific example of behavior to protect the quality of farmland.It is interesting that the penetration of the Internet and its spread to rural areas bring digital change to the agricultural and rural sectors, as well as changes in farmers' behavior when producing or making decisions [

16,

17]. This change not only has the potential to promote the efficiency of agriculture and expand the amount of food available, but it can also be used as a means to facilitate the greening of agriculture [

18].

In summary, regarding the influence of social capital on farmers' behavior in protecting arable land quality and adopting green production technologies, relevant studies generally show that strong social capital significantly increases these types of protective behavior and the adoption of these technologies [

19,

20]. However, there is no agreement on the structure and classification of farmers' social capital. At the same time, people still don't know how social capital influences farmers' protection and maintenance of farmland quality. Moreover, the existing studies also ignore the influence of farmers' Internet use. In reality, farmers' access to the Internet enhances the effectiveness of social capital in the spread of information and technology, thus improving farmers' actions to protect their farmland quality.Thus, based on reality in rural society, this study classifies farmers' social capital into two types: bonding social capital, which refers to the network and trust among farmers; and linking social capital, which refers to the network and trust between farmers and governmental entities.Ground on this two-fold typology of social capital, this paper studies the influence of social capital on the behavior of farmers' farmland quality protection and the path of the influence. And it explores the role of Internet use in the influence of social capital on those protective behaviors. According to the findings, this paper puts forward targeted measures to improve such behavior so as to promote the efficient and sustainable farmland conservation, and contribute to the rural ecological revitalization.

3. Data Sources, Variable selection, Research methods

3.1. Data Sources

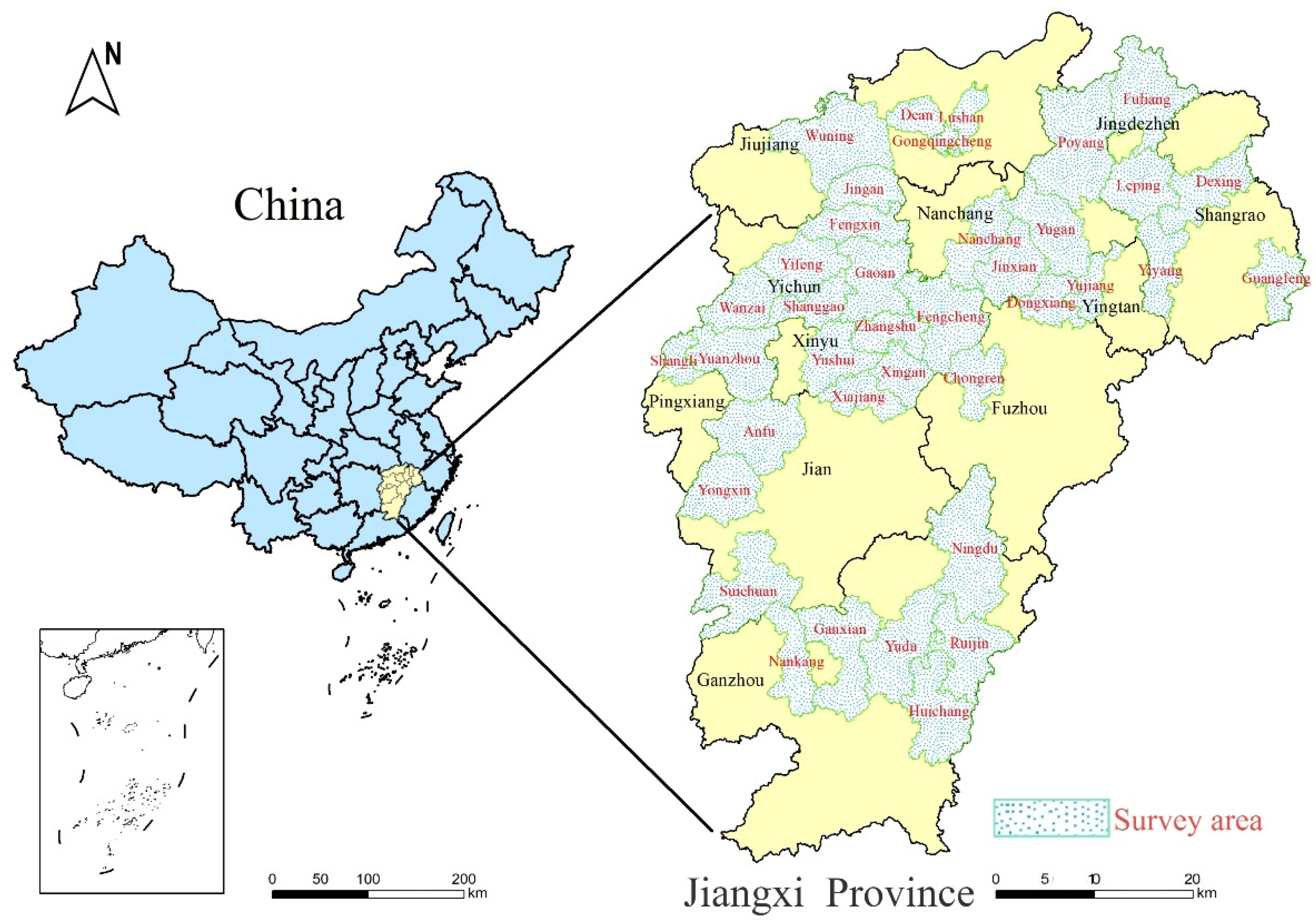

Jiangxi Province is a key agricultural province in China; it has many agricultural and rural resources, and it is also called "Land of Fish and Rice" and is one of China's twelve primary rice-producing regions. (provinces, cities, municipalities) in China. Its rice output accounted for 10.02% of the national total in 2023, ranking it third in the country. The province has a resident population of 45.2798 million, of which 17.1746 million live in the countryside, accounting for 37.93% of the total. The main types of terrain features are hills, mountains, and plains. The rural area of Jiangxi is a classic image of Chinese rural society.In recent years, Jiangxi Province has actively implemented the farmland quality conservation initiative and has made significant progress. But there are still issues such as low soil fertility, a large amount of low- and medium-yield farmland, and soil acidification [

34]. Thus, focusing on rice farmers in Jiangxi Province to conduct an in-depth investigation of how social capital affects their farmland quality protection behaviors carries significant practical implications. The data used in the article is primarily through questionnaires collected from various counties in Jiangxi Province among rice farmers between December 2022 and September 2023.

Before the survey began, the questionnaire of the study team was reviewed and approved by the university's ethics committee. The content of the questionnaire did not contain sensitive information. The participation of the respondents was voluntary, and their personal privacy was protected. They can withdraw at any time. The sample data includes all 11 prefecture-level cities, 38 counties, and 95 townships (and towns) of Jiangxi Province; these areas basically cover the typical rice-growing areas of major grain-producing counties in Jiangxi Province. (The sampled counties are shown in

Figure 2.) The survey was mainly focused on the household heads, and it was done with a one-on-one interview. A total of 1056 questionnaires were distributed. After exclusion of invalid response questionnaires according to the indicators that the study requires, a total of 1013 valid questionnaires were retained, with an effective rate of 95.74% for the sample. Thus, this sample is highly representative of researching the farmland quality protection behavior of rice farmers in Jiangxi Province.

3.2. Variable Selection

Explained Variable: Farmland Quality Protection Behavior. The definition of farmland quality protection is based on the official document "

Action Plan for the Protection and Improvement of Farmland Quality.” issued by the former Ministry of Agriculture [

35]. This plan clearly states that the quality of farmland protection consists of improvements in three aspects: land use patterns, input application methods, and waste treatment. And the operationalization of this variable is also based on the existing scholarly research [

36]. Operationalizing this variable involves seven specific conservation actions under three dimensions. For land usage patterns, it includes deep plowing and subsoiling, and straw return incorporation. For input application methods, it contains soil testing and formula fertilization, application of organic fertilizer, and use of biopesticides. For waste management practices, it comprises agricultural plastic film recycling and pesticide container recycling. These seven practices together determine how much of the farmers' farmland quality protection behaviors there are. Farmers were given a score based on how many of the seven practices they adopted: 0 if they did not adopt any, one if they adopted one, two if they adopted two, and so forth until reaching seven if they adopted all seven practices. Therefore, Farmland Quality Protection Behaviors takes an ordinal value of 0 to 7.

Explanatory variable: Social Capital. The concept and the scope of social capital are subject to considerable debate among academics, and the measure and definition of it are often adjusted according to the goals of a specific study. According to an analysis of the categories and the scope of farmers' real-world social interaction, this study identifies that there are two kinds of farmers' social capital: 1) bonding social capital, which refers to the relational networks and degree of trust within the farmers themselves; 2) linking social capital, which refers to the relational networks and degree of trust among farmers and the government [

26]. Bonding social capital was formed by the three indicators of (1) the number of relatives who frequently communicate, (2) the number of WeChat friends, and (3) whether there is a mutual aid or labor exchange among farmers during rice planting. Mutual aid among farmers is spontaneous and stems from strong social capital. It serves as a resource swap. The exchange of agricultural production information among farmers serves as a crucial channel for learning about and adopting new technologies, Consequently, the frequency of such information exchanges can be used to some extent as an indicator of the strength of a farmer's social ties. Linking social capital is measured by three indicators: (1) whether there is a village or township cadre in the household; (2) whether the farmer has participated in the training organized by the government, and (3) the farmer's evaluation of the village cadre. The relationship and trust between farmers and the government can affect not only farmers' rice cultivation decisions and practices, but also influence their willingness to adopt farmland quality protection behaviors or green production technologies, which is an important social capitals for farmers.

As for the variable treatment, this paper applies the entropy method to calculate the weight of each indicator, and then calculates the total score of farmers' social capital. The specific indicators and their corresponding weights are as follows in

Table 1.

Mechanism Variables: Utility Cognition, Policy Cognition, Internet Use. Utility cognition and policy cognition both belong to the category of ecological cognition. Through interaction with other farmers or government bodies, the farmers are informed about the ecological knowledge and policies. And after being processed and internalized by farmers, it forms their own specific cognition on the utility of ecological protection and the content of environmental policies. Similarly, Ecological cognition has a great influence on whether farmers will implement quality protection of farmland or not. Hence, ecological utility cognition and ecological policy cognition are the intermediate variables in the impact of social capital on farmers' farmland quality protection behavior.

Ecological utility cognition is measured by "Ecological production can reduce the incidence of disease among residents," and the response is recorded as 1 for strongly disagree, 2 for disagree, 3 for neutral, 4 for agree, and 5 for strongly agree. The given scores are 1 to 5, the higher the score indicates the higher level of ecological utility cognition. Likewise, ecological policy cognition was evaluated with the item, “What level of understanding do you have for eco-environmental protection policies?” The answers were given in the following manner: 1 = Not at all familiar, 2 = Slightly familiar, 3 = Moderately familiar, 4 = Familiar, 5 = Very familiar. The scores range from 1 to 5, where the larger the number, the higher the level of ecological policy cognition.

The use of the Internet increases the efficiency of information exchange in the social capital network of farmers and increases their ability to learn. It also helps translate the green production technology spread via these networks into production decisions, thereby enhancing the impact of social capital on farmland quality preservation, so Internet usage positively moderates the impact of social capital on farmers’ farmland quality protection actions. This variable was constructed from two survey questions: (1) "Do you use the Internet? (1 = Yes, 0 = No) and (2) "Do you use the Internet to search for agricultural information? (1 = Yes, 0 = No). A composite score (ranging from 0 to 2) was calculated, where 0 indicates the ability to do neither, 1 indicates the ability to do one of them, and 2 indicates the ability to do both. A higher score reflects a higher level of Internet use.

Control Variables: Individual characteristics, operational characteristics, and Village Characteristics. To isolate the effect of social capital on farmers' farmland quality protection behaviors, this study, in line with prior research [

37], incorporates three sets of control variables: individual characteristics, operational characteristics, and village characteristics. Individual characteristics contain gender, age, education level, and health status. Operational characteristics encompass household type (whether part-time farming), risk preference, farmland scale, farmland fragmentation, and farmland quality. Village characteristics include the village's economic level within the county and its traffic conditions. The descriptive statistics for all variables are presented in

Table 2.

3.3. Research Methods

The Entropy Method. To calculate a composite index for farmers' social capital, this study employs the entropy method. This approach determines indicator weights based on the principle of information entropy, representing an objective weighting method that avoids the subjectivity inherent in human judgment. Due to significant differences in the units and scales of the various indicators, each indicator was first standardized using the following formula:

In Formula (1), Z

ij represents the standardized value of the variable. To avoid zero values, Z

ij is shifted by 0.0001 units to the right. Subsequently, the entropy value and information utility value for each indicator are calculated. Following this, the weight W

i for each indicator is then calculated. Finally, the social capital index for farmers is derived based on the standardized indicators and their respective weights, as shown in the formula(2):

Baseline Regression Model. In this study, the explained variable is farmers' farmland quality protection behaviors, which is an ordinal variable ranging from 0 to 7. Therefore, the Ordered Probit model is selected for the baseline regression. The econometric model is specified as follows:

In Equation (3), i denotes an individual farmer, and Y

i represents the latent (unobserved) variable for farmland quality protection behaviors. SC denotes social capital, encompassing both bonding and linking types. Ctr

i represents the control variables, ε

i is the stochastic error term, and β

1 and β are the regression coefficients for their respective variables. The relationship between the observed farmland quality protection behaviors (Y

i) and the latent variable (Y

i*) is defined as follows:

In Equation (4), r

0, r

1,...,r

7 represent the unknown cut points. Consequently, the probability of a farmer adopting different numbers of farmland quality protection behaviors is given by:

In Equation (5), θ denotes the CDF of the standard normal distribution. Since the baseline regression results can only illustrate the influence of each variable on farmers' farmland quality protection behaviors in terms of significance and coefficient sign, and cannot fully quantify their marginal impact, this study further calculates the marginal effects of every variable on these behaviors. The specific calculation formula is:

In Equation (6), y is the explained variable, and x represents all explanatory variables in the regression. The marginal effect indicates the probability of a change in the explained variable y when an explanatory variable changes by one unit.

Mediation Effect Model. To verify Hypothesis 2 and following the approach of Wen et al. [

38], a mediation effect model is constructed as follows:

In Equation (7), Mediumi denotes the mediator variables, specifically utility cognition and policy cognition. α1 represents the coefficient of the effect of social capital on utility cognition and policy cognition. In Equation (8), δ2 indicates the effect of utility cognition and policy cognition on farmers' farmland quality protection behaviors after controlling for social capital.

Moderation Effect Model. To test Hypothesis 3, a Moderation Effect Model is constructed following the approach of James et al. [

39].

In Equation (9), SCi denotes social capital, Interneti denotes Internet use, and SCi×Interneti represents their interaction term. The coefficient λ3 captures this interaction effect, and its significance is used to determine the presence of a moderating effect.

4. Results

4.1. Analysis of The Baseline Regression Results

Before estimating the Ordered Probit model, a test for multicollinearity was conducted on all explanatory variables. The results indicate that the mean VIF is 1.18, and all individual VIF are well below the critical threshold of 10. This suggests the absence of severe multicollinearity issues and confirms that the model exhibits an overall good fit. The variables in this paper were processed using Stata 18, and the results of the impact of social capital are shown in

Table 3.

First, Model (1) is used to estimate the effect of social capital on farmers' farmland quality protection behavior. Then, individual characteristics, operating characteristics, and village characteristics were successively added as control variables to explore the impact of social capital, which resulted in Models (2), (3), and (4). Finally, to verify the effects of various types of social capital, the influence of its two components—bonding and linking social capital—was analyzed, resulting in model (5).

From Model (1) to Model (4), the effect of social capital on the behavior of farmland quality protection is always positive and significant at the 1% level, with coefficients of 1.223, 1.004, 0.809, and 0.827, respectively. This strongly supports a positive promoting impact of social capital on these behaviors. Thus, Hypothesis 1 is supported. Model (5) looks at the effect of farmers' bonding social capital and linking social capital. Both types of social capital have a significantly positive influence on the behaviors of farmland quality protection at 1%, with coefficient values of 2.064 and 0.264, respectively. Therefore, hypothesis 1a is supported, and hypothesis 1b is supported.

In terms of the effect of control variables on farmers' farmland quality protection behaviors, longer years of education mean more farmland quality protection behaviors. And it may be that the more educated farmers generally have stronger environmental consciousness, leading them to act to protect the farmland. Conversely, part-time farming exerts a significant negative impact. It might be because the part-time farmer relies less on agriculture and its land than a full-time farming household would, so they spend less time and effort on protecting the quality of their farmland. In addition, the bigger the farmland scale and the better the land quality, the more beneficial it is to the farmers' farmland quality protection behavior. It is due to the fact that larger farmland scale enhances farmers' expected return on investment through economies of scale, leading to a higher probability of conservation practice adoption. Meanwhile, good farmland is also naturally more valuable and productive. To preserve this resource endowment and ensure sustainable yields, farmers are more likely to implement protection measures on their land proactively.

There is a inverse correlation among the economic level of villages and farmers' farmland quality protection behavior. This could be because of the fact that as the village economic development increases, it offers farmers more off-farm employment opportunities, which decreases the time that farmers would have for agricultural activities and consequently diminishes engagement in protection practices. On the contrary, good village accessibility means a higher level of farmland quality protection behavior. This positive relationship may be because better accessibility allows people and goods to flow more freely, spreading information and technology, leading to more farmers adopting these practices.

4.2. Marginal Effects Analysis

Marginal effects analysis for the Ordered Probit model used in this research is needed to obtain a clearer understanding of how every factor affects farmland quality preservation. Specifically, the marginal effects reported here refer to the impact of social capital on the probability of farmers adopting different numbers of farmland quality protection practices. The results are shown in

Table 4 below.

As can be seen from

Table 4, as the level of social capital rises, the likelihood of farmers being in a low-level protection state (from "0 practices adopted" to "3 practices adopted") significantly declines; at the same time, the chance of adopting high-level protection behaviors (from "4 practices adopted" to "7 practices adopted") obviously rises. It shows that social capital does not uniformly promote all types of behaviors; rather, it facilitates a structural shift in farmers' protection behaviors from low to high levels. For example, for each unit increase in social capital, the probability of farmers adopting "5 protection practices" increases by a large 13.4 percentage points.

As for the impact of the two kinds of social capital, the bonding social capital and the linking social capital have a marginal effect in the same direction, but their effect strengths differ significantly. The absolute values of marginal effects for bonding social capital are larger than those for linking social capital in all behavioral tiers. Take the adoption of "5 practices" as an example, the marginal effect of bonding social capital is 0.338, and the marginal effect of linking social capital is 0.043. In terms of reducing the probability of adopting "1 practice" the effect of bonding social capital (-0.268) is also markedly more substantial than that of linking social capital (-0.034). This indicates that in driving the adoption of farmland quality protection behaviors, bonding social capital-rooted in informal ties based on kinship and geography-exerts a stronger influence than linking social capital, which is based on formal institutional networks.

4.3. Robustness Test

1. Replace the model. Given that the dependent variable, farmers' farmland quality protection behaviors, is an ordinal categorical variable ranging from 0 to 7, the Ordered Logit regression model also provides an appropriate alternative for estimating the effect of the independent variables. As presented in

Table 5, Model (6) shows that social capital remains statistically significant at the 1% level, with a coefficient of 1.356. Model (7) reveals that bonding social capital is significant at a 1% level (coefficient is 3.226), whereas linking social capital is significant at a 5% level (coefficient is 0.443). These consistent results confirm that the baseline results were robust.

2. Replace the dependent variable. The explained variable in this study is farmers' comprehensive farmland quality protection behavior. A key part of that safeguarding is reducing chemical fertilizer input. Hence, to test the robustness of the results, the original dependent variable is substituted by a single-item measure based on the survey question "In agricultural production, have you paid attention to reducing the amount of chemical fertilizers input?" (1 = yes; 0 = no). A Probit model was then employed for estimation, providing a valid alternative measure of protection behavior. As can be seen from Model (8) in

Table 5, social capital is still significant at the 1% level, with a coefficient of 1.241. Model (9) shows that both bonding and linking social capital are significant at the 1% level, with coefficients of 2.198 and 0.481, respectively. These findings further support the main findings.

3. Winsorization. Extreme values may compromise the accuracy of regression results. Winsorization is an effective method to mitigate this concern by replacing values beyond specific percentile thresholds with the values at those percentiles, thereby preserving the original sample size. In this study, a 5% two-sided Winsorization was applied to all continuous variables involved in the baseline regression. As shown in Model (10) in

Table 5, social capital remains significant at the 1% level, with a coefficient of 0.868. Model (11) shows that both bonding and linking social capital are significant at the 1% level, with coefficients of 2.360 and 0.273, respectively. Overall, the significance and direction of the effects of social capital on farmers' farmland quality protection behaviors show no substantial change. These results pass the robustness check, confirming that the model specification and estimation results of this study are reliable.

4.4. Endogeneity Test

The Ordered Probit model may suffer from endogeneity issues caused by missing variables, measurement errors, or sample selection bias, which can cause biased estimates of the social capital coefficient. To address this concern, this paper follows the approach of Roodman [

40]. and uses the Conditional Mixed Process (CMP) estimator for analysis. The dependent variable is farmers' farmland quality protection behaviors, which is ordinal, so the CMP estimator is more appropriate than the traditional 2SLS. A crucial step in applying the CMP method is selecting a valid instrumental variable (IV), which must satisfy the requirements of relevance and exogeneity. This study uses the average social capital of other farmers in the same village, excluding the individual farmer, as the instrumental variable [

41].

Within a village, the social environment influences an individual farmer's social capital; however, the social capital of any single farmer cannot directly impact the total social capital of the area. Moreover, the average social capital of others will not directly affect the farmland quality protection behavior of a single farmer. Thus, this instrumental variable meets the criteria for both relevance and exogeneity. Prior to the CMP estimation, a weak instrument test was conducted, following the conventional 2SLS framework. The result is 1233.790. The result shows an F-statistic of 1233.790, which far exceeds the critical threshold of 10, with a p-value of 0.000. This provides further empirical evidence supporting the strength and validity of the chosen instrumental variable.

The main point of the CMP method is that it has a two-stage process. The first stage examines the correlation between the explanatory variable and the instrumental variable. In the second stage, the instrumental variable is incorporated into the model, and the exogeneity of the explanatory variable is assessed based on the estimate of the endogeneity parameter, atanhrho_12. If atanhrho_12 is statistically significant and differs from zero, it shows the presence of endogeneity.

As manifested in

Table 6, the results show that in the first stage, the instrumental variable is significantly correlated with social capital at the 1% level. In the second stage, atanhrho_12 is not statistically significant. This confirms that social capital in the baseline regression model is not endogenous, lending further reliability to the core findings. Furthermore, the absolute values of the marginal effects of social capital on farmland quality protection behaviors, derived from this procedure, are greater than those reported in

Table 4. This suggests that endogeneity, if present, might have led to an underestimation of social capital's actual effect in the initial models.

4.5. Mechanism Analysis

Building upon the baseline regression, this section further examines the mechanisms through which social capital influences farmers' farmland quality protection behaviors. As presented in

Table 7, the analysis encompasses the mediating role of ecological cognition (including utility cognition and policy cognition) and the moderating role of Internet use.

The mediation of utility cognition. As shown in Model (12) in

Table 7, social capital has a positive effect on farmers' utility cognition, with a coefficient of 1.129 that is significant at the 1% level. It means that the social capital improves the farmers' acquisition of information, breaks up the out-of-date notion, and raises the ecological utility cognition level. Based on the mediation effect model, Model (13) shows that after including the level of utility cognition, social capital, and utility cognition, they significantly promote farmers' behavior to protect the quality of farmland, and the significance test is passed at the 1% level. Notably, the coefficient of social capital in this model (0.657) is smaller than the coefficient of social capital in the baseline regression model (4) (0.827). It is initially judged that utility cognition partially mediates the relation between social capital and farmers' protection behavior.

The mediation effect of policy cognition. Model (14) in

Table 7 shows that social capital has a positive effect on farmers' policy cognition, with a coefficient of 1.532, which is significant at the 1% level. It can be seen that through the farmers' relational networks with other farmers or the government, they obtain more information about ecological and environmental protection policies, thus increasing the farmers' policy cognition. Model (15) adds policy cognition to the model, which shows that both social capital and policy cognition significantly promote farmland quality protection behavior; both coefficients pass the significance test at the 1% level. Social capital has a smaller coefficient (0.597) compared to the same variable in the baseline regression Model (4), which is 0.827. It is initially judged that policy cognition also partially mediates the relationship between social capital and farmers’ conservation behavior. Therefore, based on the empirical results and analysis above, hypothesis 2 is supported.

The moderating role of Internet use. Based on the model of the moderation effect, the model (16) in

Table 7 reveals that social capital and Internet use have a significant positive effect on farmers' farmland quality protection behavior, and there exists a synergistic interaction effect between them. Specifically, social capital and Internet use individually increase protective behavior. More importantly, the interaction term between social capital and Internet use has a coefficient of 0.420, which is significant and positive at the 5% level. It proves that Internet use significantly enhances the positive effect of social capital on farmers' farmland quality protection behavior, indicating a positive moderation effect. These findings support Hypothesis 3.

With the diffusion of Internet technology into rural society, not only does it become an important means for farmers to acquire agricultural technical information, policy information, and market information, but more importantly, as a "social capital amplifier", it has enhanced the operational efficiency and resource mobilization capabilities of traditional social networks. Through instant messaging, social media, and online communities, the Internet break through the time and space restrictions of information transmission among relatives, friends, and government officials. It allows for a faster and broader spread of green production technology, ecological concepts, and environmental policies, and ultimately translates into practical protection practices, thereby promoting farmers' farmland quality protection behaviors.

4.6. Heterogeneity Analysis

In order to further study the impact of social capital on the farmland quality protection behavior of different farmer groups, this paper examines the heterogeneity of the effect of social capital on the farmland quality protection behavior of farmers from two aspects: the household type (part-time farming household or full-time farming household) and farmers' risk preference. Specifically, a grouped regression method is applied so that the impact of social capital can be seen according to the differences in farmer characteristics.

Heterogeneity Analysis of Different Farming Households Types, the results are indicated in

Table 8. In the household type sub-group, the influence of social capital on farmland protection behavior is significant at the 1% level for full-time farmers, with a coefficient of 0.875. On the contrary, for part-time farming households, it is only significant at the 10% level, with a coefficient of 0.612. From the perspective of the marginal effect of social capital on the farmland quality protection behavior of the two types of farmers, the absolute value of the marginal effect of the full-time farming household is greater than that of the part-time farming household. Taking the adoption of five protection behaviors as an example, the marginal effect of pure farmers is 0.147, which is significant at the 1% level, while the marginal effect of part-time farmers is 0.085, which is significant at the 10% level. This fully demonstrates that the positive role of social capital is even more prominent among groups that rely entirely on agricultural income. This difference probably comes from fundamental differences in production objectives and resource constraints between these two groups. The livelihood of full-time farming households is heavily reliant on their farmland. They possess greater social capital, embedded in localized kinship and geographical networks, that can be more easily turned into real substance, such as sharing agricultural technical know-how, helping each other with labor, and sharing risks. And so, this greatly encourages them to take up long-term conservation practices. Part-time farming households, in contrast, have diversified incomes and are less dependent on land. Therefore, a part of its social capital will flow into the non-agricultural sector, resulting in relatively weaker investment motives for farmland protection. And it takes some time and energy from farmers who are engaged in part-time farming, which might also weaken the ability of farmers to transform social capital into concrete actions of farm management.

Analysis of heterogeneity in different risk preferences, the results are indicated in

Table 9. From the risk preference subgroup analysis results, we can see that the effect of social capital is an apparent nonlinearity. The effect is most substantial for risk-neutral farmers, with a coefficient of 1.345, significant at the 1% level. Risk-appetite farmers follow this with a coefficient of 1.011, significant at the 5% level. The regression coefficient for risk-averse farmers is 0.524, which is statistically significant at the 5% level. Examining the marginal effects of social capital from the perspective of farmland quality protection behaviors, both risk-neutral and risk-preferring farmers exhibit larger absolute values than their risk-averse counterparts. Taking the adoption of five protection practices as an example, the marginal effect for risk-neutral farmers is 0.256 (significant at the 1% level), compared to 0.133 for risk-preferring farmers (significant at the 5% level). However, the effect for risk-averse farmers is only 0.089, which is also significant at the 5% level. This underscores the significant impact that risk attitude has on the conversion of social capital into tangible results.

Compared to risk-averse farmers, risk-neutral or risk-appetite farmers generally have more reasonable characteristics. To evaluate objectively the value of the information and resources obtained through social networks, without being afraid or preoccupied by the unknown that the new technologies and practices will introduce. Thus, they are better able to convert social capital into actual farmland quality protection behaviors. On the other side, because risk-averse farms are extremely sensitive to losses, they will act as wait-and-see and will still follow traditional, conventional ways of producing despite high social capital. And this tendency erodes the facilitative effects of social capital.

5. Discussion

As the main guardians of farmland, the driving factors behind their behavioral decisions are worth noting. Based on social capital theory and farmers' decision-making behavior theory, this study aims to study in depth the influence of social capital and its structure on the farmland quality protection behavior of farmers. Compared with previous studies, this paper may make the following possible marginal contributions. In measuring social capital, the study categorizes it into two categories: bonding social capital among farmers and linking social capital between farmers and the government. It better corresponds to the actual realities of the farmers' production and life. For measuring farmland quality protection behaviors, seven indicators are used to assess the behavior across three dimensions: land use patterns, input application methods, and waste management, providing an overall assessment. In terms of impact mechanism, the study identifies farmers' ecological cognition as an important channel through which social capital influences farmland quality protection behavior, and finds that Internet use plays a positive moderating role in how social capital affects farmers' farmland quality protection behavior. Finally, to account for heterogeneity, the study incorporates two dimensions: household type, reflecting divergent livelihood strategies, and risk attitude, as a fundamental psychological trait. It then investigates how the magnitude of social capital's effect differs across these groups.

The results manifest that social capital has a strong positive effect on farmers' farmland quality protection behavior. This finding is in line with the study by Li et al. [

22] and Qiu et al. [

23] indicating that farmers' social networks and trust are important drivers of farmers' decisions on land protection. Both bonding social capital among farmers and linking social capital between farmers and the government positively promote these protection behaviors. But in terms of the strength of effect, bonding social capital has a greater effect than linking social capital. This observation shows a slight difference from the results by Yang et al. [

25]. This may be due to the differences in the way indicators for the two kinds of social capital were constructed, leading to different magnitudes of influence. However, the direction of the effect is consistent for both. Ecological cognition serves as a medium for the influence of social capital. This is consistent with the research conclusion by Zhang et al. [

27] and Li et al. [

42]. It shows that strong social capital can improve farmers' ecological awareness, which is an important endogenous driving force to promote green production or farmland quality. Furthermore, the Internet can serve as a powerful means to amplify the effect of social capital, and it is one factor that leads to farmland quality protection behavior. Similarly, conclusions like those in the study by Gong et al. [

31] and Zheng et al. [

32] show that Internet use contributes to farmers protecting farmland quality and promoting ecological production.

This study has conducted a meaningful search on how social capital can promote farmers' farmland quality protection behavior, but some limitations should be paid attention to. First, a lack of comparison between different regions or farmers growing different crops may limit the generalizability of the results. Secondly, while social capital can facilitate farmers' non-agricultural employment [

43], it is partly counteracted by the positive effect of social capital on farmland conservation. In future studies, it would be meaningful to incorporate this factor into the analytical framework to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the influence of social capital. Lastly, due to the cross-sectional nature of the survey data, we are unable to capture the dynamic changes in farmers' behavior. Future work can use panel data to explore how farmers' farmland protection behaviors co-evolve with dynamic changes in social capital, allowing for better causal inferences.

6. Research Conclusions and Policy Recommendations

6.1. Research Conclusions

Based on China's ongoing farmland quality conservation initiatives, this paper studied rice farmers from Jiangxi Province using an Ordered Probit model, a mediation effect model, and a moderation effect model to analyze the influence and mechanism of farmers' social capital and the structure of its on their farmland quality protection behavior. It further examined the heterogeneous influences of social capital across different kinds of farmers and risk preferences. The following conclusion is drawn.

(1) Social capital has a significant positive impact on farmers' farmland quality protection behavior. Both bonding social capital (among farmers) and linking social capital (between farmers and government) promote these behaviors, but the former is greater than the latter. Specifically, the more frequent the interactions, mutual assistance, and the higher the degree of trust among farmers themselves and between farmers and the government, the greater the likelihood that farmers will adopt practices to protect farmland quality.

(2) On the one hand, ecological cognition serves as a significant channel through which social capital positively influences farmers' farmland quality protection behaviors. Social capital can enhance farmers' ecological consciousness, including their awareness of the necessity of ecological production for a healthy life, and their knowledge of environmental protection policies. Thus, they will participate more actively in conservation actions. On the other hand, Internet use positively moderates the promoting effects of social capital on these behaviors. It helps farmers communicate and exchange information with their relatives, friends, and government agencies, facilitating the spread of green production technology. This, in turn, enables farmers to transform information and knowledge into action, thereby significantly improving their behavior in protecting the quality of their farmland.

(3) Social capital plays a stronger role in farmland quality protection behavior for full-time farming households and risk-neutral or risk-appetite farmers. Because the livelihoods of full-time farming households are more dependent on agriculture, they are more willing to take conservation measures to protect their long-term interests. In contrast to risk-averse farmers, risk-neutral or risk-appetite farmers are more willing to experiment and try new agricultural production technology, thereby improving their farmland quality protection behavior.

6.2. Policy Recommendations

According to the findings, this study makes the following policy recommendations to encourage farmers to engage in farmland quality protection and to achieve a green transformation of agricultural production.

(1) Focus on cultivating farmers' social capital. On the one hand, the establishment of specialized farmers' cooperatives and agricultural mutual aid organizations, as well as the organization of cultural activities, strengthens the links between farmers, forming a more solid and diverse network of social capital and thus increasing bonding social capital. Secondly, we must enhance the support of village cadres and agricultural technicians for farmers' production activities, stimulate villagers' participation in public affairs, and strengthen farmers' confidence in the government to cultivate the linking social capital.

(2) Improve farmers' ecological cognition and encourage Internet adoption and penetration among them. Because ecological cognition encourages farmers to protect the quality of their farmland, the government must utilize different channels, like the Internet, Bulletin Boards, Radio, Television, and other means, to popularize ecological cognition, environmental protection policies, and laws. Additionally, regularly convening village collective meetings or organizing targeted training sessions can help foster ecological and environmental cognition among farmers, thereby stimulating their motivation to adopt conservation practices. Using the Internet to improve the efficiency of communication among farmers' relational networks, diffuse technologies and knowledge, and thereby improve farmland quality protection behaviors. Therefore, we should speed up the construction of Internet infrastructure in rural areas so that everyone can get access to it, give publicity and emphasis to excellent farmers in communities who are good at using the Internet, utilizing follow-on effect and neighborhood effect to inspire more people to try out and follow them; also we should call for village grassroots cadres to engage in villagers, popularizing Internet literacy and teaching them how to use the Internet.

(3) Speed up the training of new types of agricultural entities and actively promote agricultural insurance. On the one hand, efforts are made to promote large professional farmers, family farms, agricultural cooperatives, etc., through policy, technology, market, and human resources. It will improve the long-term expectations of farmers for land management and promote the behavior of protecting farmland quality. On the other hand, farmers' risk aversion reduces their willingness to use green production technologies. Therefore, it is crucial to vigorously promote agricultural insurance to improve farmers' risk resilience. This, in turn, will boost their confidence and motivation to adopt green production technologies, thereby encouraging the protection of arable land quality.