3.1. FTIR Spectroscopy: Co-Extraction Hypothesis and Model Systems

The ATR–FTIR spectrum of the butanolic extract obtained from Cucumaria frondosa (Figure 4), measured as a film on a single reflexion diamond crystal after deposition from n-butanol and drying under dried air (trace solvent possibly remaining), displayed an unusually strong set of CH2/CH3 stretching bands centered near 2925 and 2850 cm−1, whose intensity markedly exceeded that of the OH stretching band typically found around 3400 cm−1. This observation deviates from the canonical spectral profile of saponins, which are characterized by rich hydroxylation patterns that dominate the IR spectrum via strong OH vibrations. The atypically high intensity of aliphatic bands raised the hypothesis that the extract contains a significant proportion of long hydrocarbon chains, possibly derived from co-extracted membrane lipids or lipid-like saponin architectures. Furthermore, a low-intensity but distinct C=O stretching band near 1735 cm−1 was observed, suggesting the presence of carbonyl functionalities; in our system these are most plausibly due to (i) ester carbonyls from co-extracted phospho-/glycolipids and (ii) a lactone (butenolide) associated with the triterpenoid aglycone, rather than a ketone, consistent with known marine triterpenoid motifs.

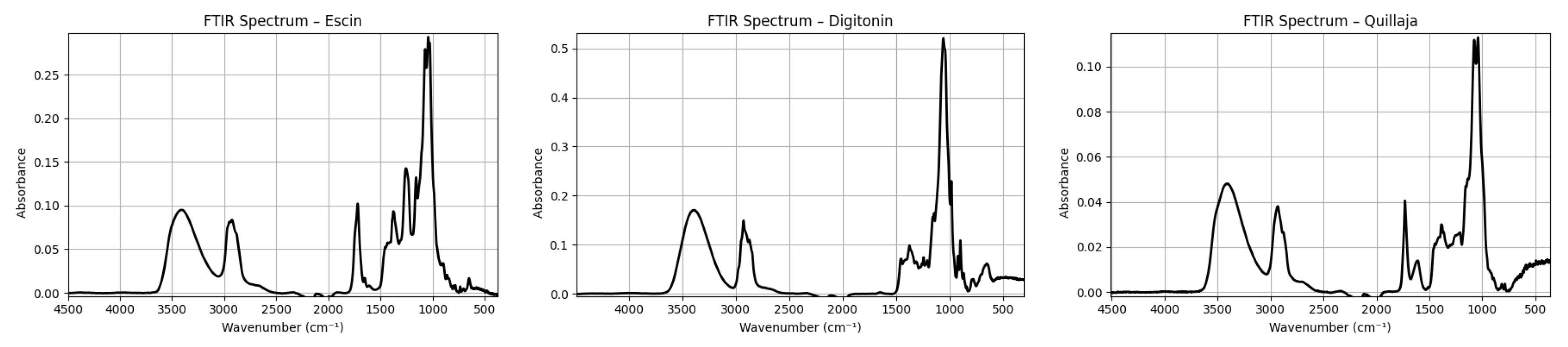

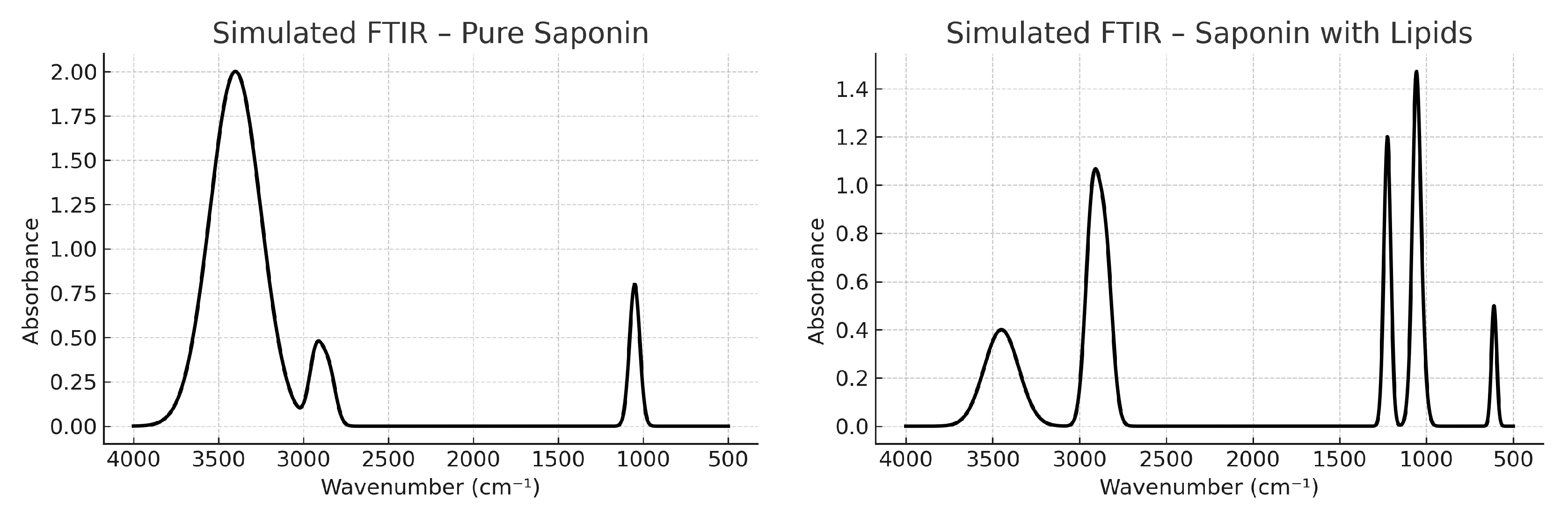

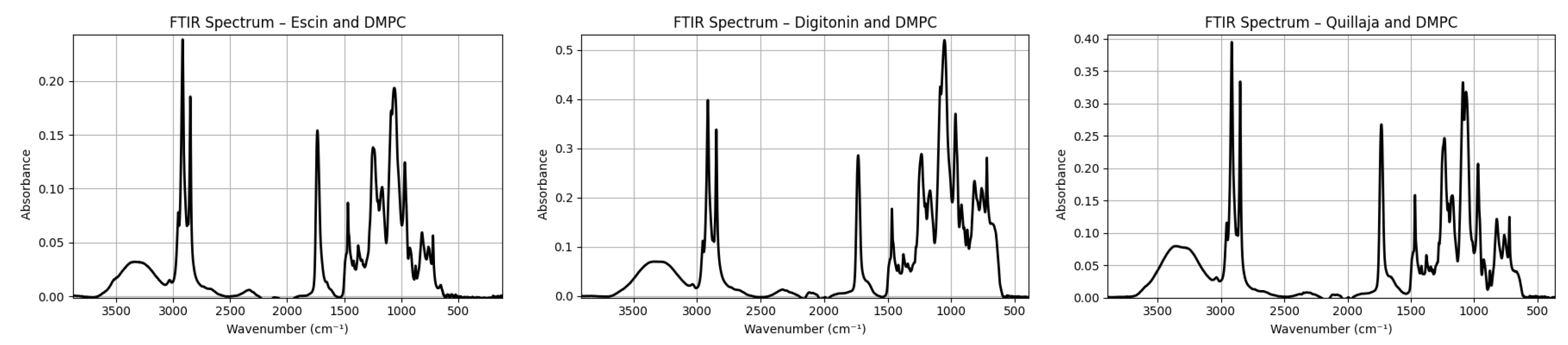

To further explore this hypothesis, a set of reference FTIR spectra were analyzed. These included simulated vibrational profiles under classical conditions for illustrative purposes (Figure 3) and experimental spectra of three structurally distinct commercial saponins—aescin, digitonin, and Quillaja saponins—measured in the solid state under the same ATR conditions (

Figure 2). The simulations for a pure triterpenoid saponin (

Figure 3a) show a broad OH band near 3400 cm

−1, moderate CH

2/CH

3 stretches, and a dense fingerprint region between 1000–1100 cm

−1 dominated by glycosidic C–O and C–O–C vibrations. Conversely, the simulation of a saponin–lipid mixture (

Figure 3b) exhibits a spectral inversion, with dominant aliphatic stretching bands and a weakened. A narrower O–H stretching band—reflecting a change in the relative contribution of hydrogen-bonded versus non-hydrogen-bonded populations, rather than an intensity variation caused by the environment—suggests that the extract contains a larger proportion of less strongly hydrogen-bonded O–H groups compared with the pure saponin.

The experimental spectra of the purified saponins closely mirrored the simulated pure saponin pattern. All three compounds showed the expected broad OH band at 3200–3400 cm−1, moderate aliphatic stretches around 2925 and 2850 cm−1, and a glycosidic fingerprint rich in C–O and C–O–C bands (1200–1000 cm−1). No sulfate-associated signals were detected in these commercial samples, as expected from their known non-sulfated structures. Notably, the N–H stretching region (3300–3500 cm−1) was either absent or extremely weak in all purified samples, in agreement with the lack of free amino groups in the structures of aescin and related saponins.

In contrast, the FTIR spectrum of the crude

C. frondosa extract (

Figure 4) revealed a highly structured vibrational profile consistent with a mixture of triterpenoid saponins, lipids, sphingolipids, and ceramides. The aliphatic CH

2/CH

3 stretching bands at ∼2925 and ∼2850 cm

−1 were particularly intense, markedly exceeding the OH stretching band near 3400 cm

−1, and reinforcing the hypothesis of co-extracted or self-assembled lipidic domains. In comparison, pure aescin displayed only moderate aliphatic features, while the addition of 1,2-dimyristoyl-

sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC) to aescin (

Figure 5a) replicated the spectral enhancement in the CH region—suggesting that the high intensity in the extract arises from similar components or interactions.

Beyond the aliphatic region, additional informative signals were observed. A sharp band at ∼1750 cm−1 and a shoulder near 1550 cm−1 were present, tentatively attributable to C=O stretching and N–H bending modes, respectively—likely arising from ester-containing lipids (phospho-/glycolipids) and amide-bearing lipids such as ceramides and sphingolipids. Consistent with this view, the C=O feature near 1735–1750 cm−1 becomes more prominent upon mixing with DMPC, supporting a lipidic origin for a significant fraction of this band, while a contribution from a triterpenoid lactone in the aglycone remains plausible. The typical glycosidic fingerprint between 1200–1000 cm−1 was also well defined, with features around 1225 and 1060 cm−1 that are compatible with the asymmetric/symmetric vibrations of sulfates (S=O) and/or phosphate () groups from phospholipids; we therefore retain both possibilities for these assignments. Interestingly, the OH stretching band in the extract was red-shifted (∼20 cm−1) compared to the purified samples, indicative of stronger hydrogen bonding or hydration—possibly related to micellar or supramolecular aggregation. Furthermore, the absence of a distinct, resolvable N–H stretching band (typically near 3250 cm−1). The pronounced absorption near 1650 cm−1 is consistent with the Amide I (C=O stretching) vibration of amide-bearing lipids, such as sphingolipids or ceramides. In this spectral region, C=C stretching modes would contribute only weakly due to their low extinction coefficients and would therefore be effectively obscured by the much stronger amide C=O signal. Together with the corresponding Amide II band, this provides strong evidence that the extract contains nitrogenous lipids not present in the aescin or aescin–DMPC model systems.

Two additional features reinforce the presence of nitrogenated compounds: a weak band near 1550 cm−1 tentatively assignable to amide II (N–H bending and C–N stretching), and a sharper band around 1700–1750 cm−1, consistent with C=O stretching from ester groups (and a possible lactone contribution in the triterpenoid aglycone). These signatures suggest the coexistence of triterpenoid saponins (rich in hydroxyl and glycosidic groups) with lipidic components bearing ester and amide functionalities. The fingerprint region (1000–1200 cm−1) remains rich in C–O and C–C vibrations from glycosidic linkages, supporting the dominance of saponin-type structures.

The annotated spectrum further helps disentangle overlapping contributions, and confirms that the extract contains a mixture of hydroxylated saponins, saturated lipid chains, possible amides, and glycosidic moieties. These observations are consistent with co-extraction of marine triterpenoids, phospholipids, and nitrogenous lipids such as ceramides or sphingomyelins, and are compatible with their association in supramolecular aggregates; however, we note that FTIR alone does not prove specific complexation.

In the 1550 cm−1 region, the expected Amide II band is partially obscured by overlapping contributions, but its presence is consistent with the pronounced Amide I absorption observed at ∼1650 cm−1. Given the much larger extinction coefficient of amide C=O stretching compared with C=C modes, the feature at 1650 cm−1 is most reasonably attributed to amide-bearing lipids such as ceramides or sphingolipids rather than to unsaturated lipid vibrations. This interpretation is further supported by the broad, structured envelope in the 3300–3500 cm−1 region, dominated by O–H stretching but likely containing a minor N–H component. Together, these spectral signatures reinforce the presence of nitrogenous lipids in the extract, in agreement with the known lipid-rich composition of echinoderms.

Crucially, the extract also revealed a broad and structured signal in the N–H/O–H region (3300–3400 cm−1), more complex than the spectra of the pure saponins. Combined with a deformation band near 1600 cm−1, this pattern is consistent with amine- and amide-containing compounds, including sphingolipids, ceramides, or even small peptides, all of which contain primary or secondary amines. This would explain both the enhanced breadth of the high-wavenumber region and the more complex bending patterns in the mid-IR, even though a distinct N–H stretching maximum is not resolved.

To experimentally test the co-extraction hypothesis and the potential role of lipid association in modifying the vibrational profile, binary mixtures of each saponin with DMPC were prepared and analyzed (

Figure 5). In all three mixtures, the CH

2/CH

3 stretching bands increased substantially in intensity, accompanied by enhanced definition in the 1450–1375 cm

−1 region, consistent with C–H bending and C–C skeletal modes typical of lipid chains. These enhancements occurred despite the lower molar extinction coefficients of hydrocarbon vibrations, suggesting a true compositional increase in lipidic content. The resulting spectra closely resembled that of the

C. frondosa extract, supporting the presence of lipid-associated domains in the crude sample. Moreover, the C=O stretching band near 1735 cm

−1 became more prominent in the DMPC mixtures, consistent with ester carbonyls from phospholipid backbones (with a possible superimposed contribution from a triterpenoid lactone). However, the N–H region remained weak, in agreement with the absence of free amines in both saponins and the DMPC headgroup, which contains only a quaternary ammonium.

Simulated FTIR spectra for mixed saponin–lipid systems (

Figure 3b) reproduced this behavior, reinforcing the idea that vibrational profiles are strongly modulated by the local molecular environment. The combination of experimental and computational evidence suggests that naturally occurring saponins may exist in the extract as lipid-associated assemblies, possibly forming supramolecular aggregates through hydrophobic and hydrogen-bond interactions. Given the amphiphilic nature of marine saponins, such self-assembled states are plausible and have been previously reported in studies of membrane solubilization and adjuvancy.

The co-extraction or complexation with lipids may also have implications for chromatographic behavior. These lipid-enriched saponin assemblies are expected to exhibit greater hydrophobicity and thus longer retention times in reversed-phase HPLC, particularly under the high-acetonitrile conditions applied in the late gradient stages of our analysis. This would help explain the detection of late-eluting compounds with aliphatic-rich mass spectra and IR profiles.

In conclusion, FTIR spectroscopy—supported by simulations and model mixtures—suggests that the C. frondosa extract contains both sulfated triterpenoid saponins and co-extracted or self-assembled lipidic components. In addition, the presence of weak N–H-related features and associated bending modes is compatible with co-extracted amine-containing lipids, such as sphingolipids or ceramides. This highlights the importance of considering matrix effects and supramolecular associations when interpreting vibrational data from marine extracts. In the following section, we complement these findings with tandem mass spectrometry to further resolve the molecular composition and fragmentation behavior of the extract.

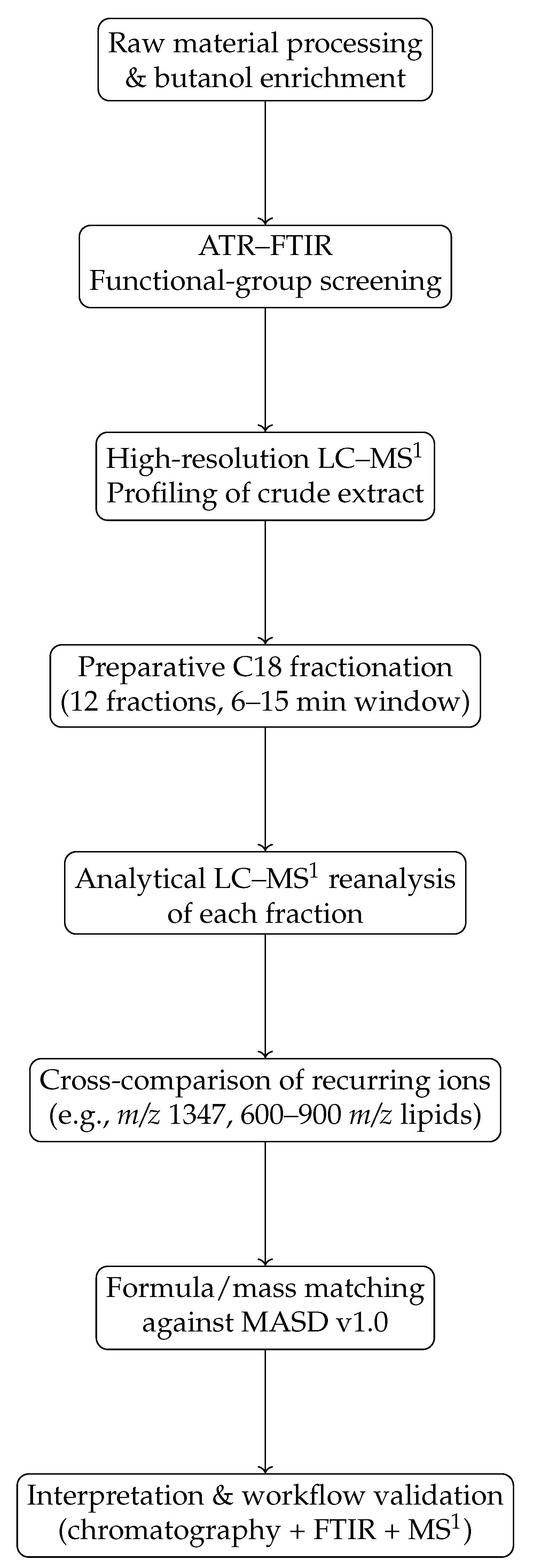

3.2. Preliminary HPLC-MS Profiling and Elution Behavior of the Extract

The butanolic extract of Cucumaria frondosa was subjected to reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS) for an initial compositional assessment. A C18 column was used under a gradient elution profile with 0.1% formic acid in water (A) and acetonitrile (B) as mobile phases. The gradient progressed from aqueous to highly organic conditions, favouring the elution of hydrophobic constituents during the later stages.

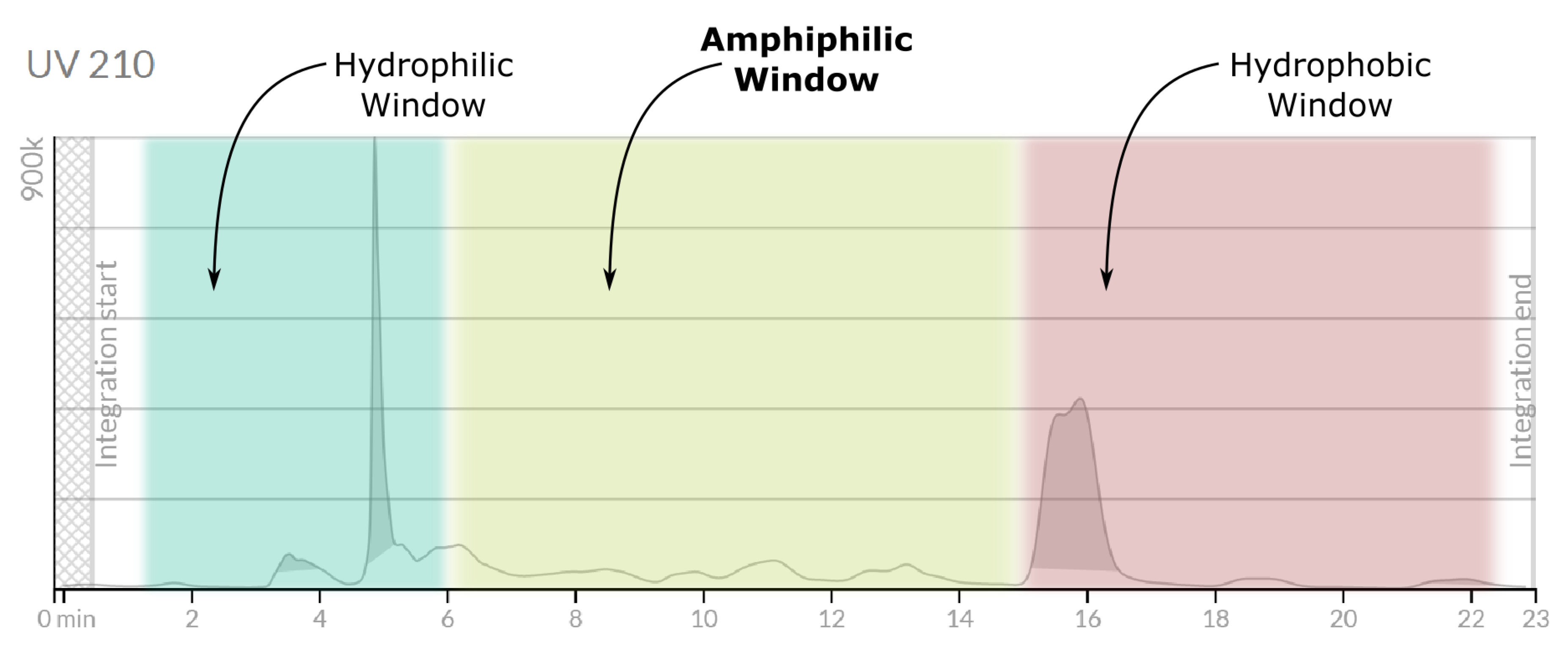

The UV chromatogram recorded at 214 nm (

Figure 6) revealed three distinct elution domains:

A prominent early peak (0–6 min), dominated by highly polar or low-molecular-weight species.

An extended intermediate region (6–15 min) containing multiple, well-resolved signals.

A late-eluting zone (after 15 min) composed of strongly hydrophobic components.

The mass spectra were acquired in both positive and negative modes employing a dual-ion ESI/APCI source showed minimal evidence of saponin-like ions in the early and late domains. In contrast, the intermediate region (6–15 min) displayed complex spectral signatures enriched in ions compatible with triterpenoid glycosides. This pattern aligns with FTIR observations indicating the presence of lipidic components associated with the saponin fraction, which may increase the effective hydrophobicity of saponin–lipid supramolecular assemblies and shift their retention times.

To more deeply interrogate this middle elution zone, a preparative-scale fractionation was carried out using the same C18 column and gradient. Twelve fractions (F1–F12) were collected across the 6–15 min window. Subsequent analytical HPLC-MS reanalysis revealed multiple chromatographic signals per fraction, with recurring mass features reproducibly detected across several fractions.

A particularly prominent ion at m/z= 1347 (positive mode) was consistently detected, especially in late-eluting preparative fractions. This ion is putatively assignable to a modified form of frondoside A. The 1347 m/z value may correspond to a frondoside adduct with a CH2 increment—potentially arising from methylene-bridge formylation via formic acid under acidic gradient conditions, a process previously described for polyol-containing molecules.

Strikingly, most fractions containing the 1347 m/z species also exhibited companion ions in the 600–900 m/z range, tentatively assignable to lipidic species (ceramides, phosphatidylcholine, sphingolipids). Their co-occurrence suggests the presence of stable or dynamically reorganising saponin–lipid aggregates, rather than isolated molecular entities.

Negative-mode ionization further revealed a robust and recurrent peak at

m/z= 477, more intense in later fractions (e.g., F6, F12). This ion corresponds, according to LIPID MAPS [

23], to

trimethyl 1-((2,5,5,8a-tetramethyldecahydronaphthalen-1-yl)methoxy)propane-1,2,3-tricarboxylate, a molecule combining polar and aliphatic features. Its co-elution with saponin-like species and selective detection in negative mode indicate a potential role in modulating the hydrophilic–lipophilic balance of the saponin–lipid assemblies, possibly contributing to the observed retention-time shifts.

Consistent with FTIR data, the presence of nitrogen-containing lipid species (e.g., ceramides, sphingolipids) is supported by the NH-related stretching and bending signals detected in the extract. Since triterpenoid saponins themselves lack nitrogen atoms, these vibrational features must originate from lipidic co-extracts, reinforcing the interpretation of supramolecular association.

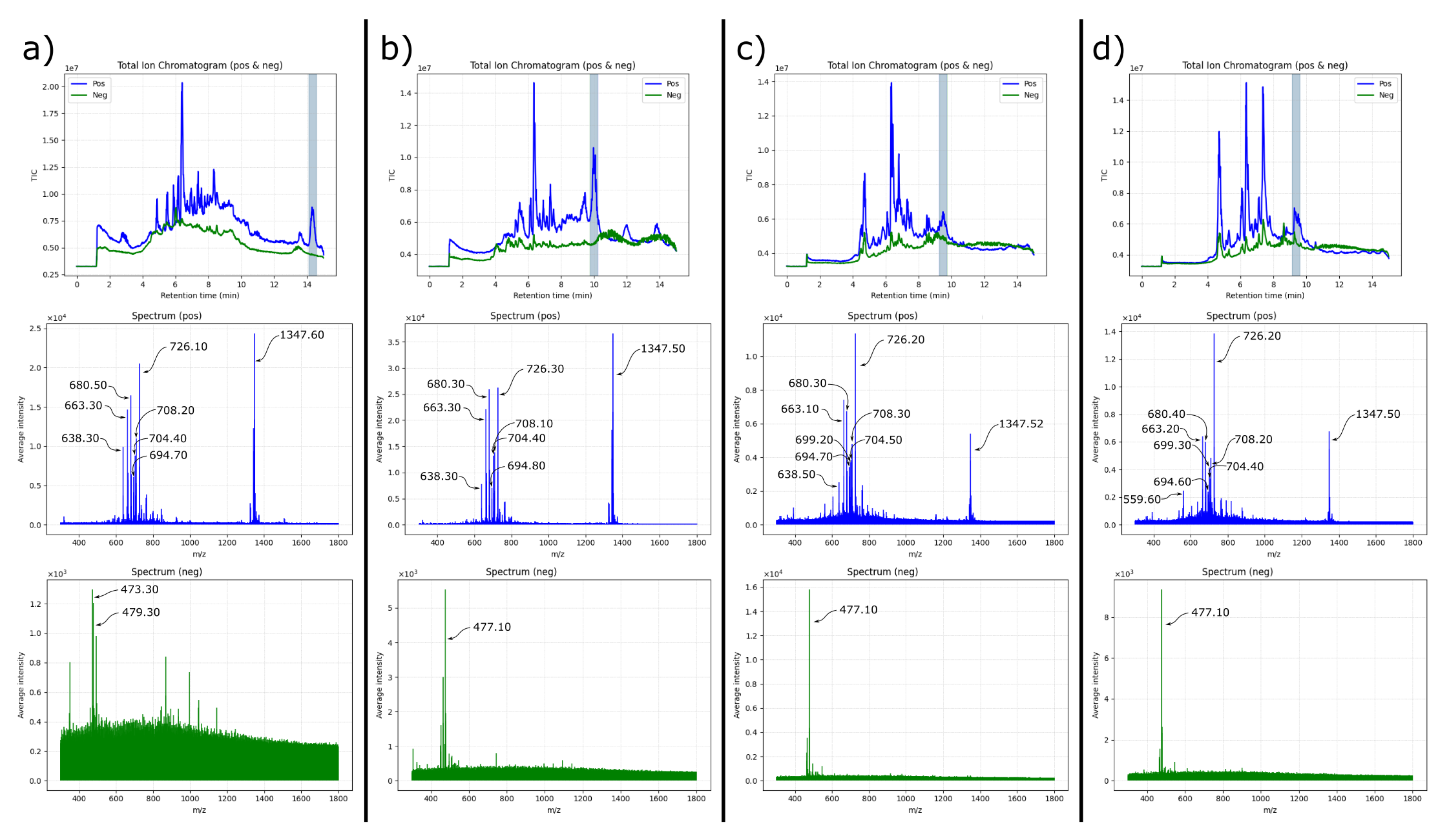

Figure 7.

LC-MS analysis of fractions F1, F2, F6 and F12 from the mid-elution zone (6–15 min). Each column (a–d) displays the total ion chromatogram (top), the average mass spectrum in positive mode (middle), and the average mass spectrum in negative mode (bottom). The recurring signal at m/z= 1347 appears in all fractions, accompanied by lipid-like ions in the 600–900 m/z range. The consistent negative-mode peak at m/z= 477 supports the presence of mixed saponin–lipid assemblies with modulated polarity.

Figure 7.

LC-MS analysis of fractions F1, F2, F6 and F12 from the mid-elution zone (6–15 min). Each column (a–d) displays the total ion chromatogram (top), the average mass spectrum in positive mode (middle), and the average mass spectrum in negative mode (bottom). The recurring signal at m/z= 1347 appears in all fractions, accompanied by lipid-like ions in the 600–900 m/z range. The consistent negative-mode peak at m/z= 477 supports the presence of mixed saponin–lipid assemblies with modulated polarity.

Interestingly, the retention time of the 1347 m/z species varied significantly among fractions. Early fractions (e.g., F1) showed the principal peak near 14 minutes, while later fractions (F6–F12) exhibited the same ion eluting earlier, around 9.5 minutes. Despite this mobility shift, the mass spectra remained remarkably consistent across fractions, strongly suggesting that the same molecular ensemble—rather than distinct chemical species—was present. We interpret this behaviour as evidence of dynamically reorganising saponin–lipid aggregates that redistribute into similar equilibrium assemblies after fraction collection and prior to analytical reinjection. This phenomenon explains the unexpected appearance of the target saponin and its lipidic companions across multiple, temporally distinct preparative fractions.

Collectively, these observations highlight the compositional and supramolecular complexity of the C. frondosa extract. The data indicate that the system does not consist of isolated molecules but of interconverting saponin–lipid aggregates whose chromatographic behaviour depends on their transient stoichiometry and microenvironment. Further purification and comprehensive structural analysis (see next section) are required to disentangle individual components and confirm molecular identities through NMR and targeted MS/MS fragmentation.

3.3. Critical Considerations for Structural Elucidation: Toward Comprehensive Spectral Validation

The release of MASD v1.0 marks an important milestone in the systematisation of marine triterpenoid saponins, providing unified molecular formulas, curated taxonomic information, and reference metadata for a large diversity of compounds. As the MASD authors clearly state, the first version of the database is deliberately centred on MS1-level information, with the explicit intention of establishing a platform that can later be expanded to include higher-order spectral data. This focus greatly increases accessibility and offers a consistent starting point for dereplication efforts across laboratories. At the same time, it naturally limits the specificity with which complex mixtures can be annotated, particularly those as chemically rich and structurally heterogeneous as Cucumaria frondosa extracts.

A long-recognised challenge in saponin research arises from the extensive structural diversity within this metabolite class. Numerous isomeric species—including aglycone variants, interchanged sugar sequences, and differences in sulfation—share identical elemental formulas. MASD v1.0 appropriately groups such structures under a common formula when MS1 data alone cannot distinguish them. Our results reflect this intrinsic limitation: several ions detected within the mid-elution window exhibit formulas consistent with saponin-like scaffolds, yet their annotation remains ambiguous without diagnostic fragmentation patterns. This behaviour is not a shortcoming of MASD itself, but rather an illustration of the fundamental inadequacy of MS1-only datasets to resolve isomeric complexity in marine secondary metabolites.

During the cross-examination of our experimental masses with the formulas listed in MASD, we observed a small subset of cases in which the reported molecular formula and the associated mass (labelled as “MWT” in the distributed dataset) did not fully coincide when recalculated as monoisotopic masses. Although the magnitude of these discrepancies is modest, they occasionally approach values consistent with CH2-equivalent shifts. With the utmost caution, we note that these deviations may arise from heterogeneity in the primary literature sources from which MASD compiles its structures, or from transcription or labelling inconsistencies inherited during data integration—challenges also acknowledged by the MASD authors in their discussion of curation limitations. Such instances are neither unexpected nor uncommon in natural product databases, particularly for structures established before the widespread implementation of high-resolution MS. Rather than detracting from the utility of MASD, these observations highlight the essential role of cross-validating formulas, exact masses, and fragmentation profiles when using the database for high-confidence annotation.

These considerations underscore the necessity of adopting an integrated analytical strategy for the structural elucidation of marine saponins. Tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) is indispensable for mapping fragmentation along both glycone and aglycone regions, enabling the discrimination of positional isomers, the identification of sugar linkages, and the confirmation of sulfation patterns. Complementarily, FTIR spectroscopy provides rapid and direct evidence of functional groups, as showcased by the characteristic S=O asymmetric stretching near 1225 cm−1 in our C. frondosa fractions. Together, MS/MS and FTIR greatly refine initial MS1-based annotations and help contextualise MASD entries within an experimentally validated framework.

Ultimately, however, full structural elucidation requires nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, provided that chromatographic purification yields fractions of adequate homogeneity. NMR remains the only technique capable of unambiguously assigning glycosidic sequences, aglycone stereochemistry, and substituent positions—elements that cannot be resolved by mass spectrometry alone. Such purification is likewise essential prior to biological testing: without molecularly defined samples, apparent bioactivities may reflect synergistic or antagonistic effects among co-extracted species, complicating structure–function interpretations.

In this light, MASD v1.0 serves as a valuable and much-needed foundation for the field, and our analysis highlights the complementary experimental efforts still required to achieve comprehensive structural resolution of marine saponins. The integration of MS/MS, FTIR, and NMR data into open-access repositories will not only enhance reproducibility, but will also enable future versions of MASD to incorporate richer, multi-dimensional spectral information. Such reciprocal development—where curated databases and experimental validation inform and strengthen one another—will be crucial for confidently identifying bioactive marine metabolites and for advancing their therapeutic potential.

Given these constraints, our analysis refrains from proposing new structures and instead focuses on demonstrating how multi-spectroscopic validation mitigates several sources of misannotation commonly encountered when relying solely on MS1-level information.