Submitted:

12 December 2025

Posted:

15 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Composite Materials in Aerospace: Overview

2.1. Definition and Classification of Composite Materials

2.2. Importance of Composite Materials in Aerospace

2.3. Advantages and Disadvantages of Composite Materials

3. Composite Materials in Structural Components

4. Composite Materials in Propulsion Systems

4.1. Engine Casings

4.2. Fan Blades

4.3. Nozzle Structures

4.4. Heat Shield Systems

5. Composite Materials in Interior Applications

5.1. Cabin Interiors

5.2. Seating Systems

5.3. Galley Structures

5.4. Lavatory Components

6. Challenges and Limitations of Composite Materials in Aerospace

6.1. Manufacturing and Processing Challenges

6.2. Repair and Maintenance Considerations

6.3. Cost Implications

6.4. Environmental Sustainability

7. Advances in Composite Materials for Aerospace Applications

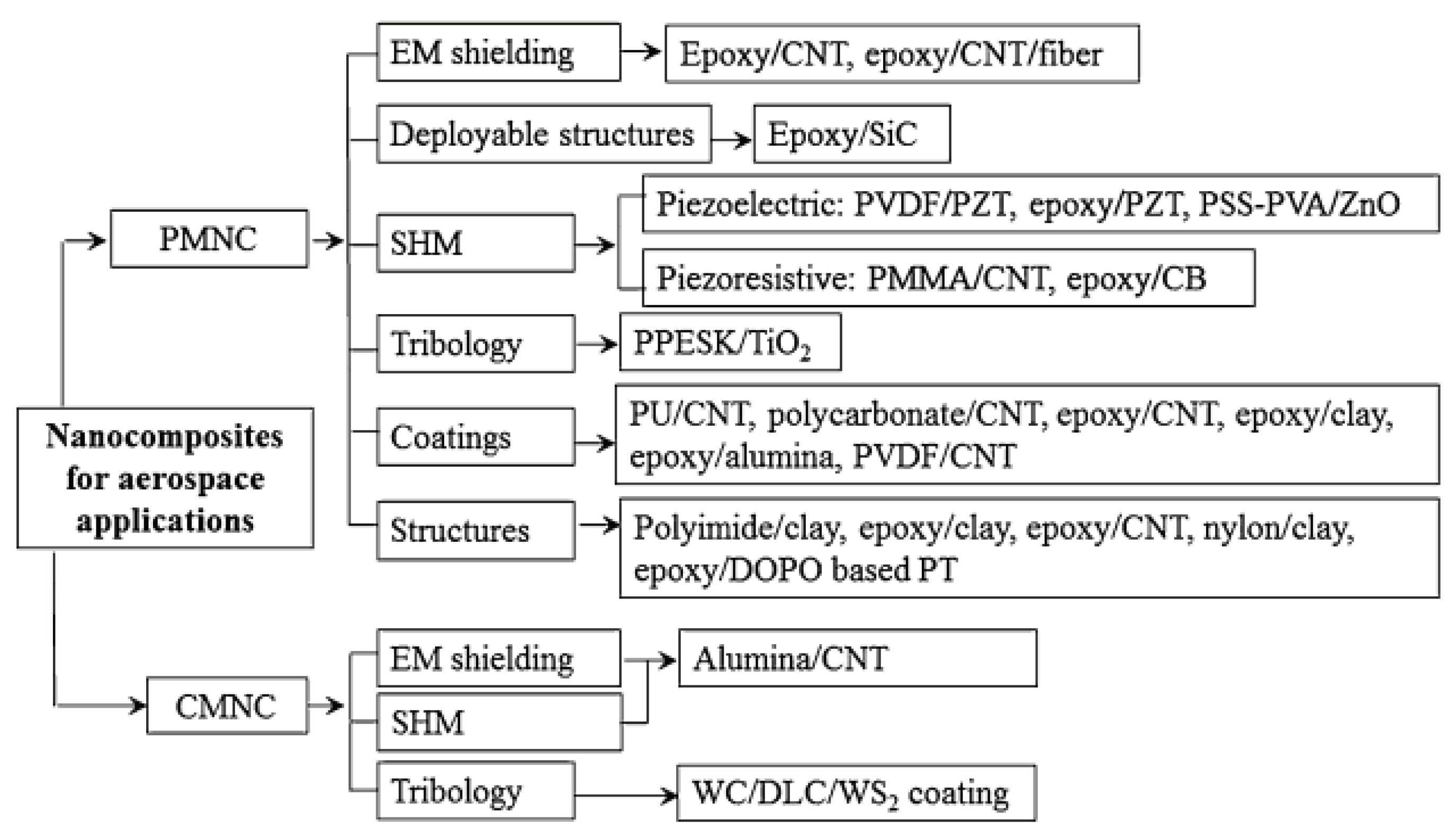

7.1. Nanocomposites and Hybrid Materials

7.2. Integrated Structural Health Monitoring Systems

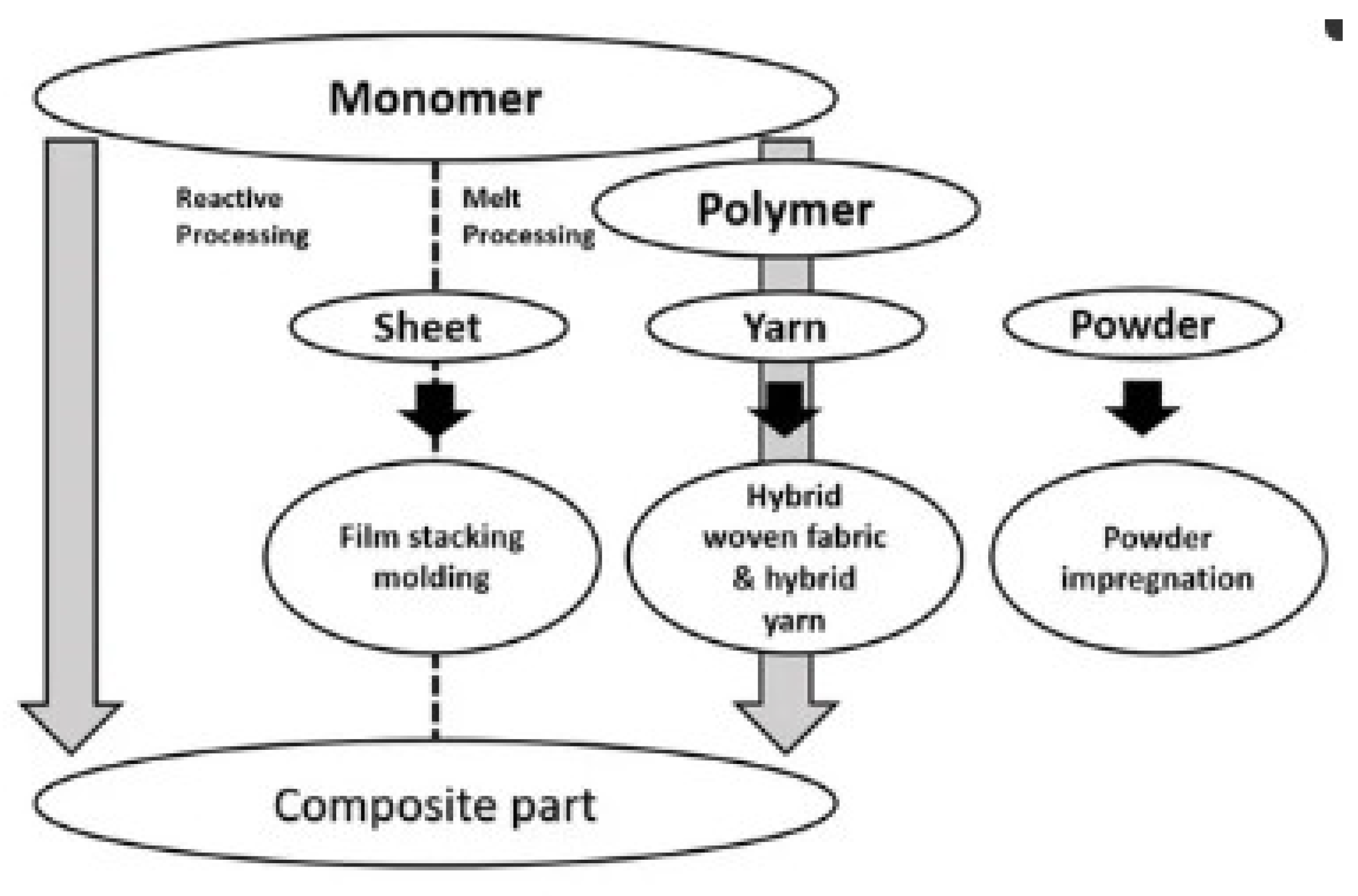

7.3. New Manufacturing Techniques and Automation

7.4. Sustainable Composite Materials

8. Performance Evaluation and Testing of Composite Materials

8.1. Mechanical Testing

8.2. Durability and Fatigue Analysis

8.3. Non-Destructive Testing Methods

8.4. Fire and Thermal Performance Evaluation

9. Regulatory and Certification Considerations

9.1. Regulatory Framework for Composite Materials

9.2. Certification and Qualification Processes

9.3. Safety and Reliability Standards

Author Contributions

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bismarck, S. Mishra, and T. Lampke, “Plant Fibers as Reinforcement for Green Composites,” in Natural Fibers, Biopolymers, and Biocomposites, CRC Press, 2005. [CrossRef]

- V. Okur, M. Ganapathi, A. Wilson, and W. K. Chung, “Biallelic variants in VARS in a family with two siblings with intellectual disability and microcephaly: case report and review of the literature,” Molecular Case Studies, vol. 4, no. 5, p. a003301, Oct. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Y. Zhou, F. Althoey, B. S. Alotaibi, Y. Gamil, and B. Iftikhar, “An overview of recent advancements in fibre-reinforced 3D printing concrete,” Front Mater, vol. 10, Oct. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Seers, R. Tomlinson, and P. Fairclough, “Residual stress in fiber reinforced thermosetting composites: A review of measurement techniques,” Polym Compos, vol. 42, no. 4, pp. 1631–1647, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Kirtania and D. Chakraborty, “Multi-scale modeling of carbon nanotube reinforced composites with a fiber break,” Mater Des, vol. 35, pp. 498–504, Mar. 2012. [CrossRef]

- K. Krishnamurthy, P. Ravichandran, A. Shahid Naufal, R. Pradeep, and K. M. Sai HarishAdithiya, “Modeling and structural analysis of leaf spring using composite materials,” Mater Today Proc, vol. 33, pp. 4228–4232, 2020. [CrossRef]

- K. S. Krishnamurthy, P. Mahajan, and R. K. Mittal, “Impact response and damage in laminated composite cylindrical shells,” Compos Struct, vol. 59, no. 1, pp. 15–36, Jan. 2003. [CrossRef]

- K. I. Tserpes, P. Papanikos, G. Labeas, and Sp. G. Pantelakis, “Multi-scale modeling of tensile behavior of carbon nanotube-reinforced composites,” Theoretical and Applied Fracture Mechanics, vol. 49, no. 1, pp. 51–60, Feb. 2008. [CrossRef]

- J. Cao, P. Xue, X. Peng, and N. Krishnan, “An approach in modeling the temperature effect in thermo-stamping of woven composites,” Compos Struct, vol. 61, no. 4, pp. 413–420, Sep. 2003. [CrossRef]

- Bismarck, S. Mishra, and T. Lampke, “Plant Fibers as Reinforcement for Green Composites,” in Natural Fibers, Biopolymers, and Biocomposites, CRC Press, 2005. [CrossRef]

- F. U. Buehler and J. C. Seferis, “Effect of reinforcement and solvent content on moisture absorption in epoxy composite materials,” Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf, vol. 31, no. 7, pp. 741–748, Jul. 2000. [CrossRef]

- G. Manickam, A. Bharath, A. N. Das, A. Chandra, and P. Barua, “Thermal buckling behaviour of variable stiffness laminated composite plates,” Mater Today Commun, vol. 16, pp. 142–151, Sep. 2018. [CrossRef]

- E. Madyaratri et al., “Recent Advances in the Development of Fire-Resistant Biocomposites—A Review,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 14, no. 3, p. 362, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Candiotti, J. L. Mantari, C. E. Flores, and S. Charca, “Assessment of the mechanical properties of peruvian Stipa Obtusa fibers for their use as reinforcement in composite materials,” Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf, vol. 135, p. 105950, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. L. Y. Léonard and J. W. Nylander, “SUSTAINABILITY ASSESSMENT OF COMPOSITES IN AERO-ENGINE COMPONENTS,” Proceedings of the Design Society: DESIGN Conference, vol. 1, pp. 1989–1998, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- Y. Kim, S. Lee, and H. Yoon, “Fire-Safe Polymer Composites: Flame-Retardant Effect of Nanofillers,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 13, no. 4, p. 540, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- V. Werlen, C. Rytka, and V. Michaud, “A numerical approach to characterize the viscoelastic behaviour of fibre beds and to evaluate the influence of strain deviations on viscoelastic parameter extraction,” Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf, vol. 143, p. 106315, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Parveez, M. I. Kittur, I. A. Badruddin, S. Kamangar, M. Hussien, and M. A. Umarfarooq, “Scientific Advancements in Composite Materials for Aircraft Applications: A Review,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 14, no. 22, p. 5007, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Taub and A. A. Luo, “Advanced lightweight materials and manufacturing processes for automotive applications,” MRS Bull, vol. 40, no. 12, pp. 1045–1054, Dec. 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Siengchin, “A review on lightweight materials for defence applications: Present and future developments,” Defence Technology, vol. 24, pp. 1–17, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Vijayan, A. Sivasuriyan, P. Devarajan, A. Stefańska, Ł. Wodzyński, and E. Koda, “Carbon Fibre-Reinforced Polymer (CFRP) Composites in Civil Engineering Application—A Comprehensive Review,” Buildings, vol. 13, no. 6, p. 1509, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Wang, D. D. L. Chung, and J. H. Chung, “Impact damage of carbon fiber polymer–matrix composites, studied by electrical resistance measurement,” Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf, vol. 36, no. 12, pp. 1707–1715, Dec. 2005. [CrossRef]

- V. Mahesh, S. Joladarashi, and S. M. Kulkarni, “A comprehensive review on material selection for polymer matrix composites subjected to impact load,” Defence Technology, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 257–277, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, R. Davidson, K. Uchino, N. Shanmuga Priya, and M. Shanmugasundaram, “7.18 Smart Composite Materials Systems,” in Comprehensive Composite Materials II, Elsevier, 2018, pp. 358–363. [CrossRef]

- D.-M. Lim, I.-S. Yoon, K.-W. Kang, and J.-K. Kim, “Fatigue Analysis of Fiber-Reinforced Composites Using Damage Mechanics,” Transactions of the Korean Society of Mechanical Engineers A, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 112–119, Feb. 2006. [CrossRef]

- V. Kobelev, Design and Analysis of Composite Structures for Automotive Applications. Wiley, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Y. Al-Assaf and H. El Kadi, “Fatigue life prediction of unidirectional glass fiber/epoxy composite laminae using neural networks,” Compos Struct, vol. 53, no. 1, pp. 65–71, Jul. 2001. [CrossRef]

- Sobey, J. Blake, and A. Shenoi, “Optimisation Approaches to Design Synthesis of Marine Composite Structures,” Ship Technology Research, vol. 56, no. 1, pp. 24–30, Jan. 2009. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Shenoi, J. M. Dulieu-Barton, S. Quinn, J. I. R. Blake, and S. W. Boyd, “Composite Materials for Marine Applications: Key Challenges for the Future,” in Composite Materials, London: Springer London, 2011, pp. 69–89. [CrossRef]

- S. Rana and R. Fangueiro, “Advanced composites in aerospace engineering,” in Advanced Composite Materials for Aerospace Engineering, Elsevier, 2016, pp. 1–15. [CrossRef]

- F. Rubino, A. Nisticò, F. Tucci, and P. Carlone, “Marine Application of Fiber Reinforced Composites: A Review,” J Mar Sci Eng, vol. 8, no. 1, p. 26, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. E. Abdel Raheem and E. M. A. Abdel Aal, “Finite Element Analysis for Structural Performance of Offshore Platforms under Environmental Loads,” Key Eng Mater, vol. 569–570, pp. 159–166, Jul. 2013. [CrossRef]

- V. S. Kathavate, K. Amudha, L. Adithya, A. Pandurangan, N. R. Ramesh, and K. Gopakumar, “Mechanical behavior of composite materials for marine applications – an experimental and computational approach,” J Mech Behav Mater, vol. 27, no. 1–2, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- J. J. Joshua, P. S. Venkatanarayanan, and D. Singh, “A literature review on composite materials filled with and without nanoparticles subjected to high/low velocity impact loads,” Mater Today Proc, vol. 33, pp. 4635–4641, 2020. [CrossRef]

- W. Wang, Y. Xiang, J. Yu, and L. Yang, “Development and Prospect of Smart Materials and Structures for Aerospace Sensing Systems and Applications,” Sensors, vol. 23, no. 3, p. 1545, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- W. Wang, Y. Xiang, J. Yu, and L. Yang, “Development and Prospect of Smart Materials and Structures for Aerospace Sensing Systems and Applications,” Sensors, vol. 23, no. 3, p. 1545, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Rodrigues et al., “Environmental Life-Cycle Assessment of an Innovative Multifunctional Toilet,” Energies (Basel), vol. 14, no. 8, p. 2307, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. H. Mian, G. Wang, U. A. Dar, and W. Zhang, “Optimization of Composite Material System and Lay-up to Achieve Minimum Weight Pressure Vessel,” Applied Composite Materials, vol. 20, no. 5, pp. 873–889, Oct. 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Shimoda, H. Otani, and J.-X. Shi, “Design optimization of composite structures composed of dissimilar materials based on a free-form optimization method,” Compos Struct, vol. 146, pp. 114–121, Jun. 2016. [CrossRef]

- T. Qiao, G. Zhang, Y. Xu, and B. Zhang, “Fabrication and Finite Element Analysis of Composite Elbows,” Materials, vol. 12, no. 22, p. 3778, Nov. 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Maria, “Advanced composite materials of the future in aerospace industry,” INCAS BULLETIN, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 139–150, Sep. 2013. [CrossRef]

- B. Parveez, M. I. Kittur, I. A. Badruddin, S. Kamangar, M. Hussien, and M. A. Umarfarooq, “Scientific Advancements in Composite Materials for Aircraft Applications: A Review,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 14, no. 22, p. 5007, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Dhanasekar et al., “A Comprehensive Study of Ceramic Matrix Composites for Space Applications,” Advances in Materials Science and Engineering, vol. 2022, pp. 1–9, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Skoczylas, S. Samborski, and M. Kłonica, “THE APPLICATION OF COMPOSITE MATERIALS IN THE AEROSPACE INDUSTRY,” Journal of Technology and Exploitation in Mechanical Engineering, vol. 5, no. 1, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- R. Talreja, Failure Analysis of Composite Materials with Manufacturing Defects. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Skoczylas, S. Samborski, and M. Kłonica, “THE APPLICATION OF COMPOSITE MATERIALS IN THE AEROSPACE INDUSTRY,” Journal of Technology and Exploitation in Mechanical Engineering, vol. 5, no. 1, Jan. 2019. [CrossRef]

- C. E. Harris, J. H. Starnes, and M. J. Shuart, “Design and Manufacturing of Aerospace Composite Structures, State-of-the-Art Assessment,” J Aircr, vol. 39, no. 4, pp. 545–560, Jul. 2002. [CrossRef]

- N. Saha, P. Roy, and P. Topdar, “Damage detection in composites using non-destructive testing aided by ANN technique: A review,” Journal of Thermoplastic Composite Materials, vol. 36, no. 12, pp. 4997–5033, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. G. Dillingham, B. R. Oakley, E. Dan-Jumbo, J. Baldwin, R. Keller, and J. Magato, “Surface treatment and adhesive bonding techniques for repair of high-temperature composite materials,” J Compos Mater, vol. 48, no. 7, pp. 853–859, Mar. 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Hassani, M. Mousavi, and A. H. Gandomi, “Structural Health Monitoring in Composite Structures: A Comprehensive Review,” Sensors, vol. 22, no. 1, p. 153, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. E. Torbali, A. Zolotas, and N. P. Avdelidis, “A State-of-the-Art Review of Non-Destructive Testing Image Fusion and Critical Insights on the Inspection of Aerospace Composites towards Sustainable Maintenance Repair Operations,” Applied Sciences, vol. 13, no. 4, p. 2732, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. Edmonds and G. Hickman, “Damage detection and identification in composite aircraft components,” in 2000 IEEE Aerospace Conference. Proceedings (Cat. No.00TH8484), IEEE, pp. 263–269. [CrossRef]

- M. E. Ibrahim, “Nondestructive evaluation of thick-section composites and sandwich structures: A review,” Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf, vol. 64, pp. 36–48, Sep. 2014. [CrossRef]

- V. Couty, J. Berthe, E. Deletombe, P. Lecomte-Grosbras, J.-F. Witz, and M. Brieu, “Comparing Methods to Detect the Formation of Damage in Composite Materials,” Exp Tech, vol. 47, no. 3, pp. 689–708, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Wang, S. Zhong, T.-L. Lee, K. S. Fancey, and J. Mi, “Non-destructive testing and evaluation of composite materials/structures: A state-of-the-art review,” Advances in Mechanical Engineering, vol. 12, no. 4, p. 168781402091376, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Powell and S. Green, “The challenges of bonding composite materials and some innovative solutions,” Reinforced Plastics, vol. 65, no. 1, pp. 36–39, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. B. Katnam, L. F. M. Da Silva, and T. M. Young, “Bonded repair of composite aircraft structures: A review of scientific challenges and opportunities,” Progress in Aerospace Sciences, vol. 61, pp. 26–42, Aug. 2013. [CrossRef]

- M. Bowkett and K. Thanapalan, “Comparative analysis of failure detection methods of composites materials’ systems,” Systems Science & Control Engineering, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 168–177, Jan. 2017. [CrossRef]

- V. Giurgiutiu and C. Soutis, “Enhanced Composites Integrity Through Structural Health Monitoring,” Applied Composite Materials, vol. 19, no. 5, pp. 813–829, Oct. 2012. [CrossRef]

- Aabid, M. Baig, and M. Hrairi, “Advanced Composite Materials for Structural Maintenance, Repair, and Control,” Materials, vol. 16, no. 2, p. 743, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Rajendran et al., “Metal and Polymer Based Composites Manufactured Using Additive Manufacturing—A Brief Review,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 15, no. 11, p. 2564, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. K. Maes, K. Potter, and J. Kratz, “Features and defects characterisation for virtual verification and certification of composites: A review,” Compos B Eng, vol. 246, p. 110282, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Z. L. Gan, S. N. Musa, and H. J. Yap, “A Review of the High-Mix, Low-Volume Manufacturing Industry,” Applied Sciences, vol. 13, no. 3, p. 1687, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Hussain, W. Xuetong, and T. Hussain, “Impact of Skilled and Unskilled Labor on Project Performance Using Structural Equation Modeling Approach,” Sage Open, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 215824402091459, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- P. J. Schubel, “Cost modelling in polymer composite applications: Case study – Analysis of existing and automated manufacturing processes for a large wind turbine blade,” Compos B Eng, vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 953–960, Apr. 2012. [CrossRef]

- M. G. Bader, “Selection of composite materials and manufacturing routes for cost-effective performance,” Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf, vol. 33, no. 7, pp. 913–934, Jul. 2002. [CrossRef]

- Martin, D. Saenz del Castillo, A. Fernandez, and A. Güemes, “Advanced Thermoplastic Composite Manufacturing by In-Situ Consolidation: A Review,” Journal of Composites Science, vol. 4, no. 4, p. 149, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- C. Zweben, “Advanced composites for aerospace applications,” Composites, vol. 12, no. 4, pp. 235–240, Oct. 1981. [CrossRef]

- M. Sasi Kumar, S. Sathish, M. Makeshkumar, S. Gokulkumar, and A. Naveenkumar, “Effect of Manufacturing Techniques on Mechanical Properties of Natural Fibers Reinforced Composites for Lightweight Products—A Review,” 2023, pp. 99–117. [CrossRef]

- M. G. Bader, “Selection of composite materials and manufacturing routes for cost-effective performance,” Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf, vol. 33, no. 7, pp. 913–934, Jul. 2002. [CrossRef]

- E. Shehab, A. Meiirbekov, A. Amantayeva, and S. Tokbolat, “Cost Modelling for Recycling Fiber-Reinforced Composites: State-of-the-Art and Future Research,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 15, no. 1, p. 150, Dec. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. A. Calado, M. Leite, and A. Silva, “Selecting composite materials considering cost and environmental impact in the early phases of aircraft structure design,” J Clean Prod, vol. 186, pp. 113–122, Jun. 2018. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Hubbe, “Sustainable Composites: A Review with Critical Questions to Guide Future Initiatives,” Sustainability, vol. 15, no. 14, p. 11088, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. J. Andrew and H. N. Dhakal, “Sustainable biobased composites for advanced applications: recent trends and future opportunities – A critical review,” Composites Part C: Open Access, vol. 7, p. 100220, Mar. 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. Rupcic, E. Pierrat, K. Saavedra-Rubio, N. Thonemann, C. Ogugua, and A. Laurent, “Environmental impacts in the civil aviation sector: Current state and guidance,” Transp Res D Transp Environ, vol. 119, p. 103717, Jun. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. F. Muhaisn, Z. A. Naser, D. H. Nayel, Z. T. Al-Sharify, and F. F. Muhaisn, “Investigate the environmental impact of aircraft on the Earth’s atmosphere and analyzing its effect on air and water pollution,” 2023, p. 090046. [CrossRef]

- Vajdová et al., “Environmental Impact of Burning Composite Materials Used in Aircraft Construction on the Air,” Int J Environ Res Public Health, vol. 16, no. 20, p. 4008, Oct. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. M R, S. Doddamani, S. Siengchin, and M. Doddamani, Lightweight and Sustainable Composite Materials: Preparation, Properties and Applications. 2023.

- G. Chatziparaskeva et al., “End-of-Life of Composite Materials in the Framework of the Circular Economy,” Microplastics, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 377–392, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- J. Bachmann, C. Hidalgo, and S. Bricout, “Environmental analysis of innovative sustainable composites with potential use in aviation sector—A life cycle assessment review,” Sci China Technol Sci, vol. 60, no. 9, pp. 1301–1317, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- Pokharel, K. J. Falua, A. Babaei-Ghazvini, and B. Acharya, “Biobased Polymer Composites: A Review,” Journal of Composites Science, vol. 6, no. 9, p. 255, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. H. Bonilla, C. M. V. B. Almeida, B. F. Giannetti, and D. Huisingh, “The roles of cleaner production in the sustainable development of modern societies: an introduction to this special issue,” J Clean Prod, vol. 18, no. 1, pp. 1–5, Jan. 2010. [CrossRef]

- N. Khanna, K. K. Gajrani, K. Giasin, and J. P. Davim, Sustainable Materials and Manufacturing Technologies. London: CRC Press, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Bastas, “Sustainable Manufacturing Technologies: A Systematic Review of Latest Trends and Themes,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 8, p. 4271, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- M. Javaid, A. Haleem, R. Pratap Singh, S. Khan, and R. Suman, “Sustainability 4.0 and its applications in the field of manufacturing,” Internet of Things and Cyber-Physical Systems, vol. 2, pp. 82–90, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Fera, R. Abbate, M. Caterino, P. Manco, R. Macchiaroli, and M. Rinaldi, “Economic and Environmental Sustainability for Aircrafts Service Life,” Sustainability, vol. 12, no. 23, p. 10120, Dec. 2020. [CrossRef]

- J. Chen, J. Wang, and A. Ni, “Recycling and reuse of composite materials for wind turbine blades: An overview,” Journal of Reinforced Plastics and Composites, vol. 38, no. 12, pp. 567–577, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- P. L. Y. Léonard and J. W. Nylander, “SUSTAINABILITY ASSESSMENT OF COMPOSITES IN AERO-ENGINE COMPONENTS,” Proceedings of the Design Society: DESIGN Conference, vol. 1, pp. 1989–1998, May 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. Chatziparaskeva et al., “End-of-Life of Composite Materials in the Framework of the Circular Economy,” Microplastics, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 377–392, Jul. 2022. [CrossRef]

- V. Lunetto, M. Galati, L. Settineri, and L. Iuliano, “Sustainability in the manufacturing of composite materials: A literature review and directions for future research,” J Manuf Process, vol. 85, pp. 858–874, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. T. Rathod, J. S. Kumar, and A. Jain, “Polymer and ceramic nanocomposites for aerospace applications,” Appl Nanosci, vol. 7, no. 8, pp. 519–548, 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. Aththanayaka, G. Thiripuranathar, and S. Ekanayake, “Emerging advances in biomimetic synthesis of nanocomposites and potential applications,” Materials Today Sustainability, vol. 20, p. 100206, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Ö. Seydibeyoğlu et al., “Review on Hybrid Reinforced Polymer Matrix Composites with Nanocellulose, Nanomaterials, and Other Fibers,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 15, no. 4, p. 984, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. C. Tjong, “Structural and mechanical properties of polymer nanocomposites,” Materials Science and Engineering: R: Reports, vol. 53, no. 3, pp. 73–197, 2006. [CrossRef]

- D. Romero-Fierro, M. Bustamante-Torres, F. Bravo-Plascencia, A. Esquivel-Lozano, J.-C. Ruiz, and E. Bucio, “Recent Trends in Magnetic Polymer Nanocomposites for Aerospace Applications: A Review,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 14, no. 19, p. 4084, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- U. A. Samad, M. A. Alam, H. S. Abdo, A. Anis, and S. M. Al-Zahrani, “Synergistic Effect of Nanoparticles: Enhanced Mechanical and Corrosion Protection Properties of Epoxy Coatings Incorporated with SiO2 and ZrO2,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 15, no. 14, p. 3100, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Kanies, R. Hayes, and G. Yang, “Thermoluminescence and optically stimulated luminescence response of Al2O3 coatings deposited by mist-chemical vapor deposition,” Radiation Physics and Chemistry, vol. 191, p. 109860, 2022. [CrossRef]

- L. M. Muresan, “Nanocomposite Coatings for Anti-Corrosion Properties of Metallic Substrates,” Materials, vol. 16, no. 14, p. 5092, Jul. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. R. Farrar and K. Worden, “An introduction to structural health monitoring,” CISM International Centre for Mechanical Sciences, Courses and Lectures, vol. 520, pp. 1–17, 2010. [CrossRef]

- E. Ozer and M. Q. Feng, “Structural health monitoring,” Start-Up Creation: The Smart Eco-efficient Built Environment, Second Edition, pp. 345–367, Jan. 2020. [CrossRef]

- W. Ostachowicz, R. Soman, and P. Malinowski, “Optimization of sensor placement for structural health monitoring: a review,” Struct Health Monit, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 963–988, May 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Teng, W. Lu, R. Wen, and T. Zhang, “Instrumentation on structural health monitoring systems to real world structures,” Smart Struct Syst, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 151–167, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- U. M. N. Jayawickrema, H. M. C. M. Herath, N. K. Hettiarachchi, H. P. Sooriyaarachchi, and J. A. Epaarachchi, “Fibre-optic sensor and deep learning-based structural health monitoring systems for civil structures: A review,” Measurement, vol. 199, p. 111543, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Z. C. Zhu, C. W. Chu, H. T. Bian, and J. C. Jiang, “An integration method using distributed optical fiber sensor and Auto-Encoder based deep learning for detecting sulfurized rust self-heating of crude oil tanks,” J Loss Prev Process Ind, vol. 74, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Y. Lu, X. Xu, and L. Wang, “Smart manufacturing process and system automation – A critical review of the standards and envisioned scenarios,” J Manuf Syst, vol. 56, pp. 312–325, Jul. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Bastas, “Sustainable Manufacturing Technologies: A Systematic Review of Latest Trends and Themes,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 8, p. 4271, Apr. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Md. I. Hossain, Md. S. Khan, I. K. Khan, K. R. Hossain, Y. He, and X. Wang, “TECHNOLOGY OF ADDITIVE MANUFACTURING: A COMPREHENSIVE REVIEW,” Kufa Journal of Engineering, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 108–146, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- W. J. A. Dahm, N. Allen, R. R. Razouk, and W. Shyy, “Challenges and Opportunities in the Next Two Decades of Aerospace Engineering,” in Encyclopedia of Aerospace Engineering, Wiley, 2010. [CrossRef]

- J. E. Spowart, N. Gupta, and D. Lehmhus, “Additive Manufacturing of Composites and Complex Materials,” JOM, vol. 70, no. 3, pp. 272–274, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- L. J. Kumar and C. G. Krishnadas Nair, “Current Trends of Additive Manufacturing in the Aerospace Industry,” in Advances in 3D Printing & Additive Manufacturing Technologies, D. I. Wimpenny, P. M. Pandey, and L. J. Kumar, Eds., Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2017, pp. 39–54. [CrossRef]

- H. Alami et al., “Additive manufacturing in the aerospace and automotive industries: Recent trends and role in achieving sustainable development goals,” Ain Shams Engineering Journal, vol. 14, no. 11, p. 102516, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. C, R. Shanmugam, M. Ramoni, and G. BK, “A review on additive manufacturing for aerospace application,” Mater Res Express, vol. 11, no. 2, p. 022001, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- B. Barroqueiro, A. Andrade-Campos, R. A. F. Valente, and V. Neto, “Metal Additive Manufacturing Cycle in Aerospace Industry: A Comprehensive Review,” Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing, vol. 3, no. 3, p. 52, Jun. 2019. [CrossRef]

- S. Guessasma, W. Zhang, J. Zhu, S. Belhabib, and H. Nouri, “Challenges of additive manufacturing technologies from an optimisation perspective,” International Journal for Simulation and Multidisciplinary Design Optimization, vol. 6, p. A9, Jan. 2015. [CrossRef]

- M. Khorasani, A. Ghasemi, B. Rolfe, and I. Gibson, “Additive manufacturing a powerful tool for the aerospace industry,” Rapid Prototyp J, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 87–100, Jan. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. Jayamani, T. J. Jie, and M. K. Bin Bakri, “Life cycle assessment of sustainable composites,” in Advances in Sustainable Polymer Composites, Elsevier, 2021, pp. 245–265. [CrossRef]

- T. Trzepieciński, S. M. Najm, M. Sbayti, H. Belhadjsalah, M. Szpunar, and H. G. Lemu, “New Advances and Future Possibilities in Forming Technology of Hybrid Metal–Polymer Composites Used in Aerospace Applications,” Journal of Composites Science, vol. 5, no. 8, p. 217, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Soundhar, V. L. Narayanan, M. Natesh, and K. Jayakrishna, “Sustainable composites for lightweight applications,” in Materials for Lightweight Constructions, Boca Raton: CRC Press, 2022, pp. 191–208. [CrossRef]

- M. Khasreen, P. F. Banfill, and G. Menzies, “Life-Cycle Assessment and the Environmental Impact of Buildings: A Review,” Sustainability, vol. 1, no. 3, pp. 674–701, Sep. 2009. [CrossRef]

- V. Prasad, A. Alliyankal Vijayakumar, T. Jose, and S. C. George, “A Comprehensive Review of Sustainability in Natural-Fiber-Reinforced Polymers,” Sustainability, vol. 16, no. 3, p. 1223, Jan. 2024. [CrossRef]

- V. Lunetto, M. Galati, L. Settineri, and L. Iuliano, “Sustainability in the manufacturing of composite materials: A literature review and directions for future research,” J Manuf Process, vol. 85, pp. 858–874, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- E. Jayamani, T. J. Jie, and M. K. Bin Bakri, “Life cycle assessment of sustainable composites,” in Advances in Sustainable Polymer Composites, Elsevier, 2021, pp. 245–265. [CrossRef]

- V. Shanmugam et al., “The mechanical testing and performance analysis of polymer-fibre composites prepared through the additive manufacturing,” Polym Test, vol. 93, p. 106925, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Ebrahimnezhad-Khaljiri, R. Eslami-Farsani, and K. A. Banaie, “The evaluation of the thermal and mechanical properties of aramid/semi-carbon fibers hybrid composites,” Fibers and Polymers, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 296–302, Feb. 2017. [CrossRef]

- V. Shanmugam et al., “The mechanical testing and performance analysis of polymer-fibre composites prepared through the additive manufacturing,” Polym Test, vol. 93, p. 106925, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- V. Shanmugam et al., “The mechanical testing and performance analysis of polymer-fibre composites prepared through the additive manufacturing,” Polym Test, vol. 93, p. 106925, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Ou and D. Zhu, “Tensile behavior of glass fiber reinforced composite at different strain rates and temperatures,” Constr Build Mater, vol. 96, pp. 648–656, Oct. 2015. [CrossRef]

- Y. Anand and V. Dutta, “Testing of Composites: A Review,” International Journal of Advanced Materials Manufacturing and Characterization, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 359–363, Mar. 2013. [CrossRef]

- S. Kangishwar, N. Radhika, A. A. Sheik, A. Chavali, and S. Hariharan, “A comprehensive review on polymer matrix composites: material selection, fabrication, and application,” Polymer Bulletin, vol. 80, no. 1, pp. 47–87, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Barreira-Pinto, R. Carneiro, M. Miranda, and R. M. Guedes, “Polymer-Matrix Composites: Characterising the Impact of Environmental Factors on Their Lifetime,” Materials, vol. 16, no. 11, p. 3913, May 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. Shanmugam et al., “Fatigue behaviour of FDM-3D printed polymers, polymeric composites and architected cellular materials,” Int J Fatigue, vol. 143, p. 106007, Feb. 2021. [CrossRef]

- D. Pertuz-Comas, J. G. Díaz, O. J. Meneses-Duran, N. Y. Niño-Álvarez, and J. León-Becerra, “Flexural Fatigue in a Polymer Matrix Composite Material Reinforced with Continuous Kevlar Fibers Fabricated by Additive Manufacturing,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 14, no. 17, p. 3586, Aug. 2022. [CrossRef]

- E. V. Yakovlev et al., “Non-destructive testing of composite materials using terahertz time-domain spectroscopy,” F. Berghmans and A. G. Mignani, Eds., Apr. 2016, p. 98990W. [CrossRef]

- R. Gupta et al., “A Review of Sensing Technologies for Non-Destructive Evaluation of Structural Composite Materials,” Journal of Composites Science, vol. 5, no. 12, p. 319, Dec. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Y. Hung, L. X. Yang, and Y. H. Huang, “Non-destructive evaluation (NDE) of composites: digital shearography,” in Non-Destructive Evaluation (NDE) of Polymer Matrix Composites, Elsevier, 2013, pp. 84–115. [CrossRef]

- B. R. Tittmann, “7.11 Ultrasonic Inspection of Composites,” in Comprehensive Composite Materials II, Elsevier, 2018, pp. 195–249. [CrossRef]

- V. V. Gonçalves, D. M. G. de Oliveira, and A. A. dos Santos Junior, “Comparison of Ultrasonic Methods for Detecting Defects in Unidirectional Composite Material,” Materials Research, vol. 24, no. suppl 2, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. TOWSYFYAN, A. BIGURI, R. BOARDMAN, and T. BLUMENSATH, “Successes and challenges in non-destructive testing of aircraft composite structures,” Chinese Journal of Aeronautics, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 771–791, Mar. 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Khan et al., “Advances of composite materials in automobile applications – A review,” Journal of Engineering Research, Feb. 2024. [CrossRef]

- T. Guo, G. Xue, and B. Fu, “Axial Compression Damage Model and Damage Evolution of Crumb Rubber Concrete Based on the Energy Method,” Buildings, vol. 14, no. 3, p. 705, Mar. 2024. [CrossRef]

- F. P. Rahimian, J. S. Goulding, S. Abrishami, S. Seyedzadeh, and F. Elghaish, Industry 4.0 Solutions for Building Design and Construction. London: Routledge, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Georgantzinos, G. I. Giannopoulos, K. Stamoulis, and S. Markolefas, “Composites in Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering,” Materials, vol. 16, no. 22, p. 7230, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. Huang, S. Su, Z. Xu, Q. Miao, W. Li, and L. Wang, “Advanced Composite Materials for Structure Strengthening and Resilience Improvement,” Buildings, vol. 13, no. 10, p. 2406, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- L. S. Sutherland, “A review of impact testing on marine composite materials: Part I – Marine impacts on marine composites,” Compos Struct, vol. 188, pp. 197–208, Mar. 2018. [CrossRef]

- B. Parveez, M. I. Kittur, I. A. Badruddin, S. Kamangar, M. Hussien, and M. A. Umarfarooq, “Scientific Advancements in Composite Materials for Aircraft Applications: A Review,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 14, no. 22, p. 5007, Nov. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Valente, I. Rossitti, and M. Sambucci, “Different Production Processes for Thermoplastic Composite Materials: Sustainability versus Mechanical Properties and Processes Parameter,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 15, no. 1, p. 242, Jan. 2023. [CrossRef]

- X. Huang, S. Su, Z. Xu, Q. Miao, W. Li, and L. Wang, “Advanced Composite Materials for Structure Strengthening and Resilience Improvement,” Buildings, vol. 13, no. 10, p. 2406, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Wang, S. Zhong, T.-L. Lee, K. S. Fancey, and J. Mi, “Non-destructive testing and evaluation of composite materials/structures: A state-of-the-art review,” Advances in Mechanical Engineering, vol. 12, no. 4, p. 168781402091376, Apr. 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. K. Georgantzinos, G. I. Giannopoulos, K. Stamoulis, and S. Markolefas, “Composites in Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering,” Materials, vol. 16, no. 22, p. 7230, Nov. 2023. [CrossRef]

- S. Waite, “Certification and airworthiness of polymer composite aircraft,” in Polymer Composites in the Aerospace Industry, Elsevier, 2020, pp. 593–645. [CrossRef]

- J. ZHU, H. ZHOU, C. WANG, L. ZHOU, S. YUAN, and W. ZHANG, “A review of topology optimization for additive manufacturing: Status and challenges,” Chinese Journal of Aeronautics, vol. 34, no. 1, pp. 91–110, Jan. 2021. [CrossRef]

- W. P. Ryan-Johnson, L. C. Wolfe, C. R. Byron, J. K. Nagel, and H. Zhang, “A Systems Approach of Topology Optimization for Bioinspired Material Structures Design Using Additive Manufacturing,” Sustainability, vol. 13, no. 14, p. 8013, Jul. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Q. Ma, M. Rejab, J. Siregar, and Z. Guan, “A review of the recent trends on core structures and impact response of sandwich panels,” J Compos Mater, vol. 55, no. 18, pp. 2513–2555, Aug. 2021. [CrossRef]

- Y. Chen et al., “Manufacturing Technology of Lightweight Fiber-Reinforced Composite Structures in Aerospace: Current Situation and toward Intellectualization,” Aerospace, vol. 10, no. 3, p. 206, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Zhou, R. Fleury, and M. Kemp, “Optimization of Composite - Recent Advances and Application,” in 13th AIAA/ISSMO Multidisciplinary Analysis Optimization Conference, Reston, Virigina: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Sep. 2010. [CrossRef]

- N. J et al., “Sustainable shape formation of multifunctional carbon fiber-reinforced polymer composites: A study on recent advancements,” Mechanics of Advanced Materials and Structures, pp. 1–35, Sep. 2023. [CrossRef]

- J. C. Ince et al., “Overview of emerging hybrid and composite materials for space applications,” Adv Compos Hybrid Mater, vol. 6, no. 4, p. 130, Aug. 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Anwajler and A. Witek-Krowiak, “Three-Dimensional Printing of Multifunctional Composites: Fabrication, Applications, and Biodegradability Assessment,” Materials, vol. 16, no. 24, p. 7531, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- N. S. Ermolaeva, M. B. G. Castro, and P. V Kandachar, “Materials selection for an automotive structure by integrating structural optimization with environmental impact assessment,” Mater Des, vol. 25, no. 8, pp. 689–698, Dec. 2004. [CrossRef]

- R. A. Fernandes et al., “Development of an Innovative Lightweight Composite Material with Thermal Insulation Properties Based on Cardoon and Polyurethane,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 16, no. 1, p. 137, Dec. 2023. [CrossRef]

- B. Chang, X. Li, P. Parandoush, S. Ruan, C. Shen, and D. Lin, “Additive manufacturing of continuous carbon fiber reinforced poly-ether-ether-ketone with ultrahigh mechanical properties,” Polym Test, vol. 88, p. 106563, Aug. 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. Liu, Y. Xiong, and L. Zhou, “Additive manufacturing of continuous fiber reinforced polymer composites: Design opportunities and novel applications,” Composites Communications, vol. 27, p. 100907, Oct. 2021. [CrossRef]

- P. Parandoush and D. Lin, “A review on additive manufacturing of polymer-fiber composites,” Compos Struct, vol. 182, pp. 36–53, Dec. 2017. [CrossRef]

- B. Kianian, “Wohlers Report 2016: 3D Printing and Additive Manufacturing State of the Industry, Annual Worldwide Progress Report: Chapter title: The Middle East,” 2016. [Online]. Available: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:114654352.

- K. Bledzki, H. Seidlitz, K. Goracy, M. Urbaniak, and J. J. Rösch, “Recycling of Carbon Fiber Reinforced Composite Polymers—Review—Part 1: Volume of Production, Recycling Technologies, Legislative Aspects,” Polymers (Basel), vol. 13, no. 2, 2021. [CrossRef]

- S. Salifu, O. Ogunbiyi, and P. A. Olubambi, “Potentials and challenges of additive manufacturing techniques in the fabrication of polymer composites,” The International Journal of Advanced Manufacturing Technology, vol. 122, no. 2, pp. 577–600, Sep. 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Y. Khalid, Z. U. Arif, W. Ahmed, and H. Arshad, “Recent trends in recycling and reusing techniques of different plastic polymers and their composite materials,” Sustainable Materials and Technologies, vol. 31, p. e00382, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Y. Khalid, Z. U. Arif, W. Ahmed, and H. Arshad, “Recent trends in recycling and reusing techniques of different plastic polymers and their composite materials,” Sustainable Materials and Technologies, vol. 31, p. e00382, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. J. Keith, G. Oliveux, and G. A. Leeke, “Optimisation of solvolysis for recycling carbon fibre reinforced composites,” 2016. [Online]. Available: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:55932091.

- K. Wong, C. Rudd, S. Pickering, and X. Liu, “Composites recycling solutions for the aviation industry,” Sci China Technol Sci, vol. 60, no. 9, pp. 1291–1300, Sep. 2017. [CrossRef]

- R. J. Tapper, M. L. Longana, A. Norton, K. D. Potter, and I. Hamerton, “An evaluation of life cycle assessment and its application to the closed-loop recycling of carbon fibre reinforced polymers,” Compos B Eng, vol. 184, p. 107665, 2020. [CrossRef]

- E. Krauklis, C. W. Karl, A. I. Gagani, and J. K. Jørgensen, “Composite Material Recycling Technology—State-of-the-Art and Sustainable Development for the 2020s,” Journal of Composites Science, vol. 5, no. 1, 2021. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).