Introduction

Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) like Uganda face significant public health challenges from concurrent infectious outbreaks and endemic threats, causing millions of deaths and the loss of over 200 million healthy life years [

1,

2]. In Africa, reliance on syndromic surveillance often limits early pathogen detection, particularly in regions with poor diagnostic access [

3]. While traditional epidemiology is valuable, it frequently lacks the resolution required for prompt, effective response [

4].

Genomic sequencing bridges this gap by providing high-resolution data on disease etiology, pathogen evolution, and drug resistance [

4,

5]. These insights are critical for targeted interventions and evidence-based public health decision-making [

6]. Despite its potential, the adoption of genomic epidemiology remains uneven in resource-limited settings [

7,

8].

Uganda, with its high burden of infectious and emerging non-communicable diseases, presents a compelling use case for integrating genomics into health policy. Leveraging genomics can refine epidemiological models, optimize resource allocation, and tailor interventions to specific genetic needs. This review explores the integration of genomics into Uganda’s public health ecosystem, focusing on surveillance, outbreak investigation, and antimicrobial resistance monitoring. We examine in-country capacity and policy influence, offering lessons for other LMICs aiming to enhance health security through genomics.

Genomics Capacity

The NHLDS-CPHL genomics core has expanded its capacity through the acquisition of advanced molecular diagnostics and the implementation of robust quality management systems. The facility is equipped with diverse sequencing platforms, including Illumina (NextSeq, MiSeq, iSeq), Oxford Nanopore (GridION, MinION), and ABI SeqStudio, supported by high-performance computing infrastructure. Partnerships with the Africa Pathogen Genomics Initiative (Africa PGI), African Society of Laboratory Medicine (ASLM), WHO, and the Global Fund have strengthened the workforce [

9], enabling near real-time outbreak reporting [

10] and the development of localized bioinformatics pipelines [

11]. Consequently, NHLDS-CPHL has emerged as a regional center of excellence, providing technical support and training to National Public Health Laboratories (NPHLs) across more than ten African nations. Committed to high-quality standards, the laboratory participates in External Quality Assessment (EQA) programs with College of American Pathologists (CAP), the National Food Institute, Technical University of Denmark (DTU), WHO, and UKNEQAS covering HIV, AMR, Mpox, and malaria, alongside United Nations Secretary-General’s Mechanism (UNSGM) bioinformatics exercises for bioweapon analysis. These capabilities position NHLDS-CPHL to lead collaborative pathogen genomics surveillance and strengthen public health systems across Africa [

12].

SARS-CoV-2 Variant Surveillance

The emergence of SARS-CoV-2 and its subsequent evolution into diverse variants posed significant challenges to public health even after the WHO declared the end as a global health emergency [

13]. This called for continuous surveillance of variants to sufficiently monitor their impact on the performance of currently available vaccines, therapies, and diagnostic tools. Considerable progress was made in establishing and strengthening local and global systems to detect signals of potential variants of interest (VOIs) and variants of concern (VOCs) and rapidly assess the risk posed by SARS-CoV-2 variants to public health [

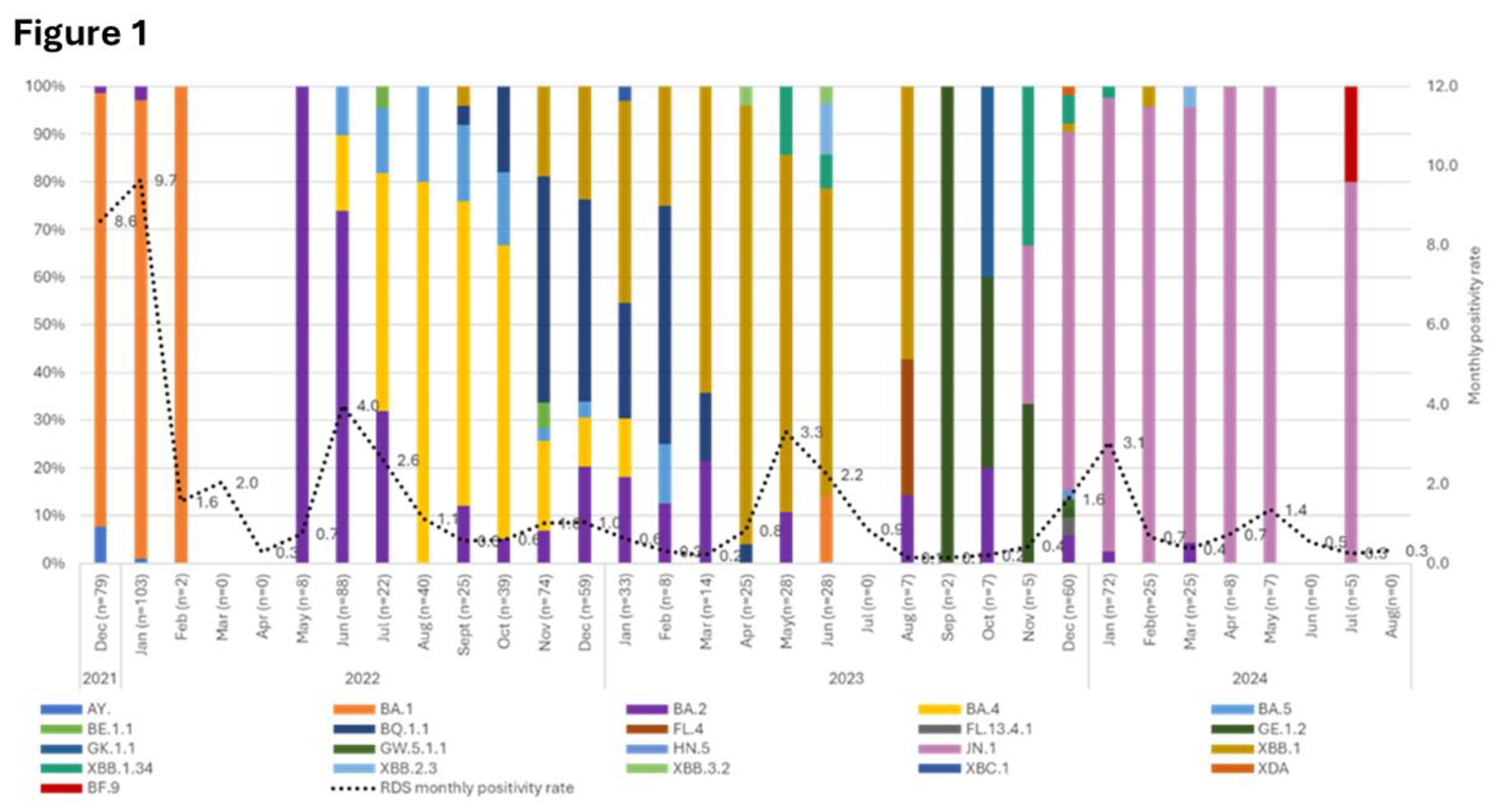

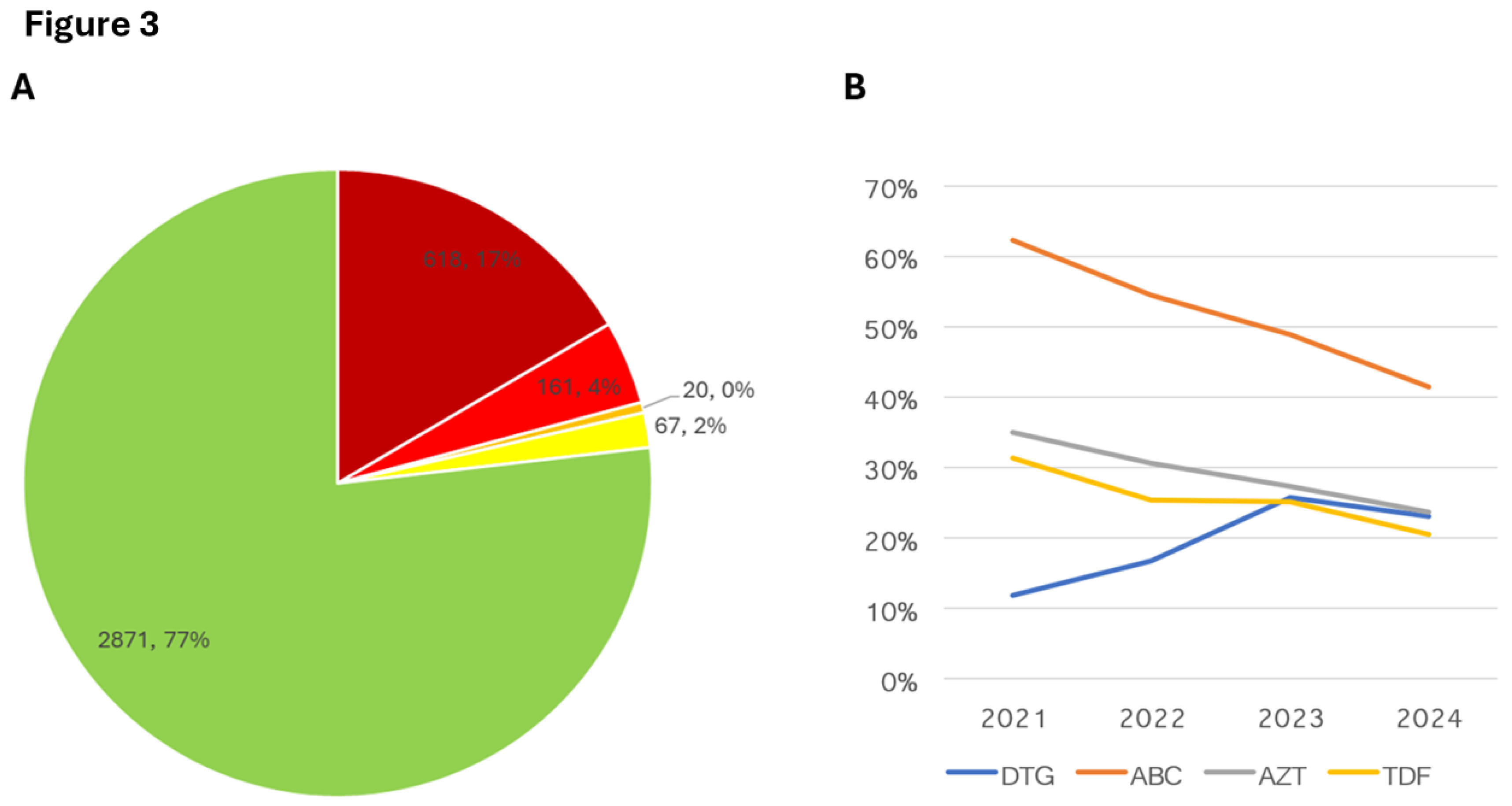

14]. At CPHL, tracking of SARS-CoV-2 VOIs and VOCs circulating in the country has been in force since 2021, albeit the low national testing. Consistent with global trends, the Omicron lineage has remained dominant, with sub-lineages still present as of July 2024 (

Figure 1). Despite low national SARS-CoV-2 testing and positivity rates, the JN.1 variant, classified as a VOI in 2023 [

15], accounted for over 95% of infections (

Figure 1). Although this variant currently poses a low global health risk, its increased transmissibility and potential for immune evasion compared to earlier variants necessitate ongoing monitoring and surveillance for effective COVID-19 management [

16]. This longitudinal analysis of variants enables the prediction of seasonal surges, allowing for timely intensification of surveillance, which has led to the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 surveillance into a comprehensive national severe acute respiratory infection and influenza-like Illness (SARI/ILI) active surveillance system.

Genomics in Wastewater-Based Surveillance

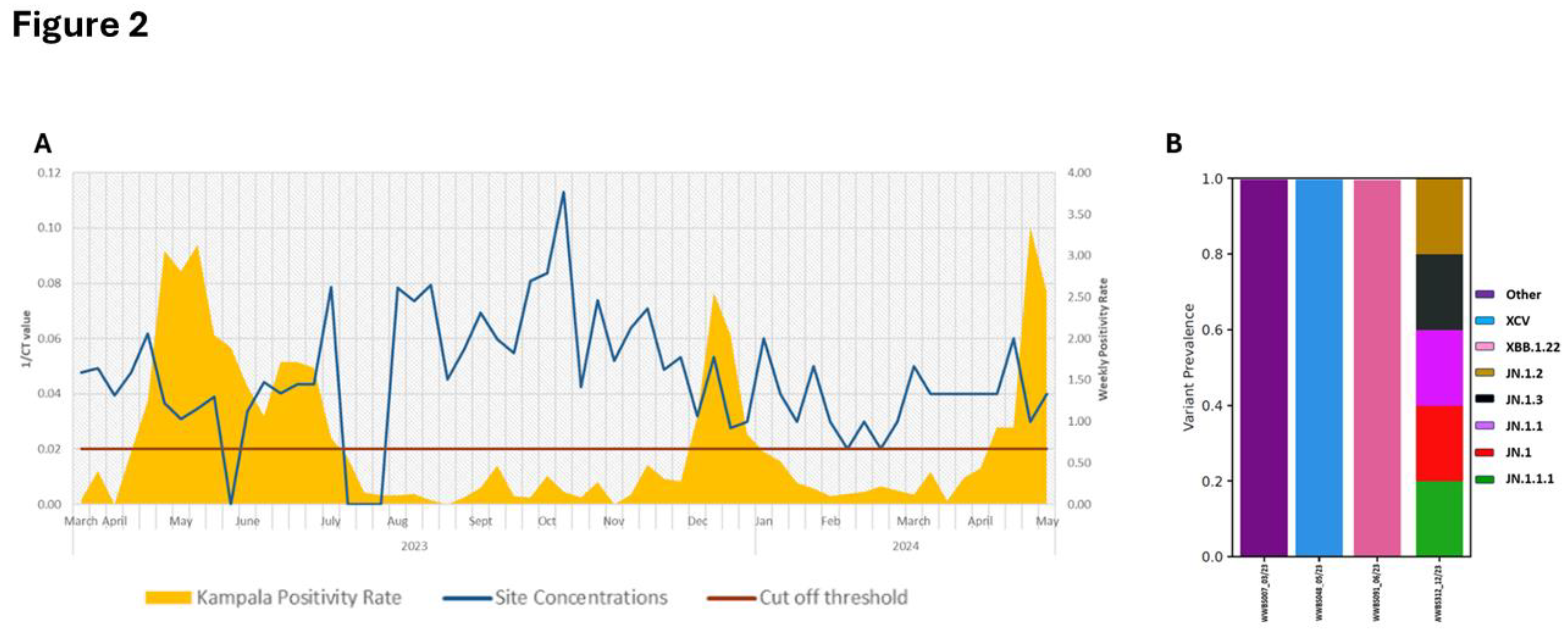

To assess the feasibility and public health value of implementing wastewater surveillance for early warning system and enhanced surveillance in Uganda, CPHL initiated a pilot project for wastewater-based SARS-CoV-2 surveillance in the Kampala metropolitan area. Our findings revealed that in late April 2023, the positivity in wastewater was twice as high as the national average. This preceded the community case surge observed in May 2023, demonstrating the value of continuous wastewater monitoring for predicting outbreaks (Figure 2A). Furthermore, wastewater samples collected between March and December 2023, were subjected to targeted genomic sequencing for VOCs and variants under monitoring (VUM) and these corresponded to those observed to circulating in the general population (Figure 1 and 2B). Overall, these data demonstrate the value of wastewater-based surveillance as an early warning outbreak indicator within the general population.

Genomics in HIV Antiretroviral Therapy Optimisation

HIV genotyping has been demonstrated as a critical tool in the clinical management of antiretroviral therapy (ART), especially in identifying and monitoring drug resistance patterns capable of compromising treatment efficacy [

17,

18]. Following the WHO recommendation [

19], LMICs, including Uganda, rapidly adopted the use of the integrase inhibitor Dolutegravir (DTG)-based regimens as part of the preferred first-line ART for HIV due to their potency, high barrier to resistance, and generally favorable tolerability profile. However, the emergence of resistance to DTG poses a significant challenge, necessitating genomic surveillance and targeted management strategies [

20,

21]. To this end, NHLDS-CPHL has since validated and integrated the use of next-generation sequencing [

22], a less subjective, more quantitative, and highly sensitive technology capable of detecting low-abundance variants, into routine care for patients with virological failure [

23,

24].

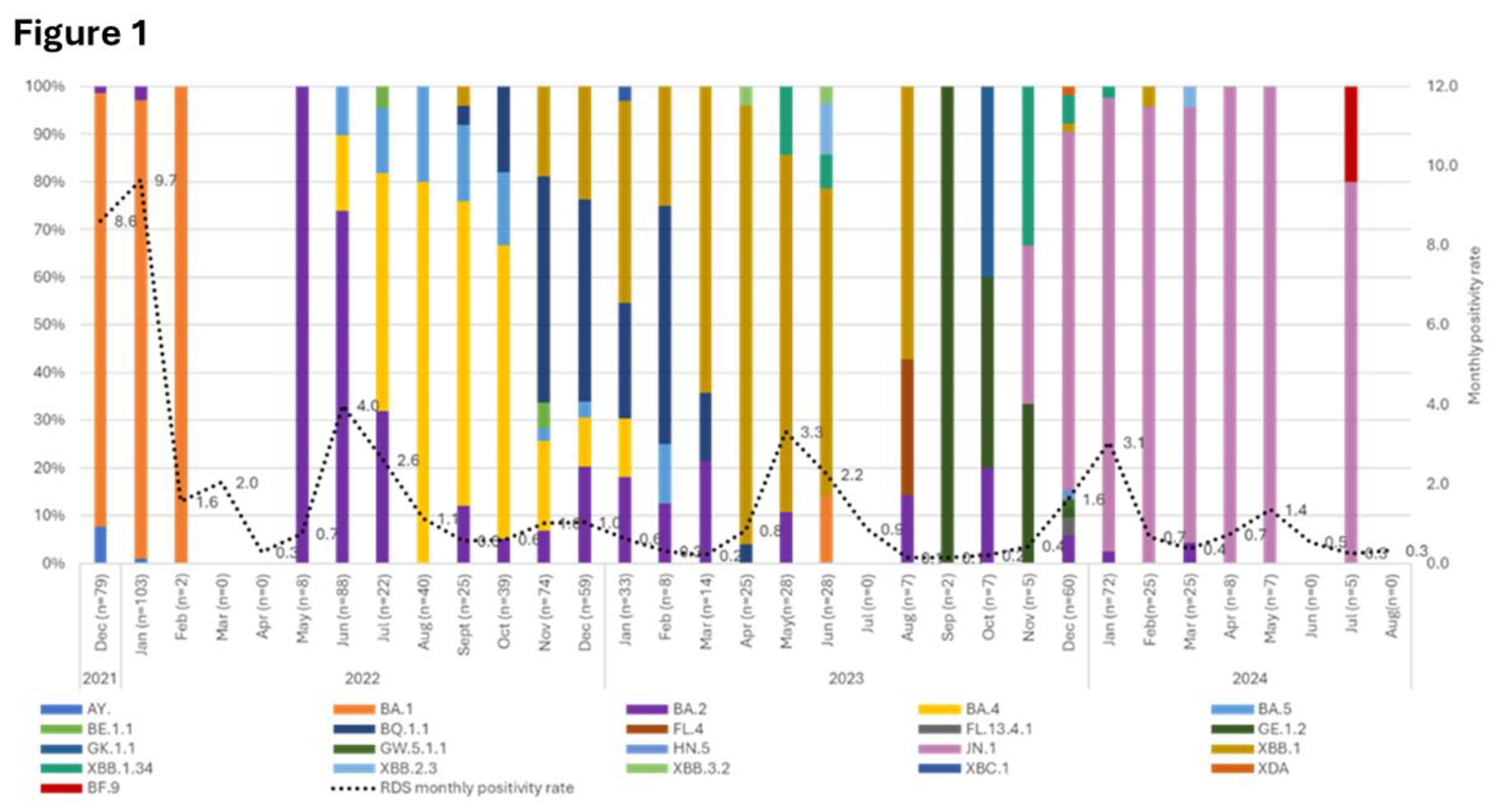

Program data generated from routine genomic surveillance has demonstrated a steady increase in DTG resistance with an up to 8% leap in 2023. However, data from for January-September 2024 data indicate a slight decrease that underscore further routine surveillance. At a granular level in 2024 data, we found up to 17% high-level, 4% intermediate, and 2% low-level resistance to DTG among patients with a non-suppressed repeat viral load (Figure 3A). Following the discussion and review of the results, most patients with intermediate to low-level resistance were not empirically switched to more expensive regimens. Additionally, our data also indicates a notable decline in acquired drug resistance to backbone drugs; Abacavir (ABC), Zidovudine (AZT), and Tenofovir (TDF) compared to Dolutegravir (DTG) (Figure 3B), underscoring the importance of genomics in routine HIV care and case management.

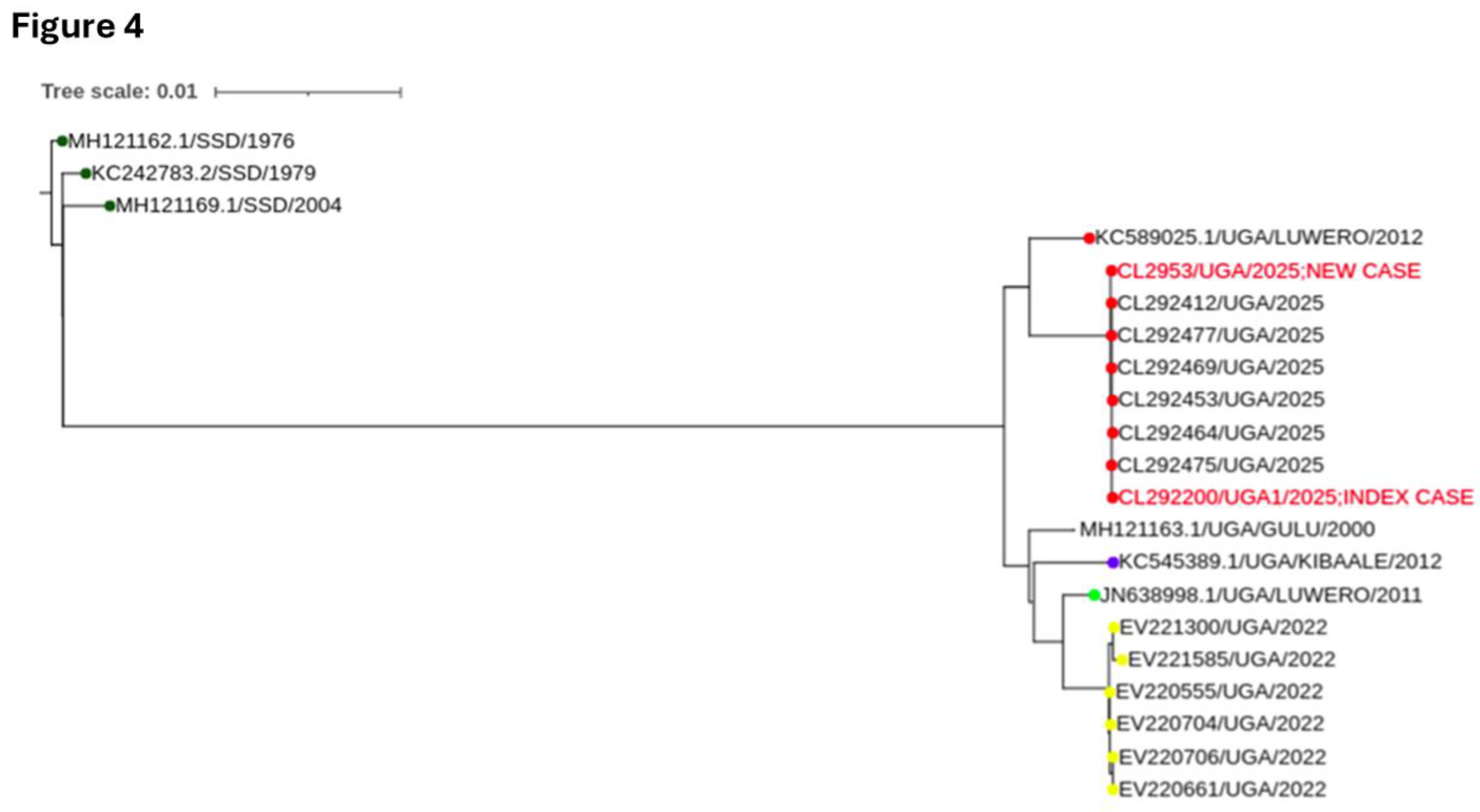

Ebola Sudan Outbreak Investigation

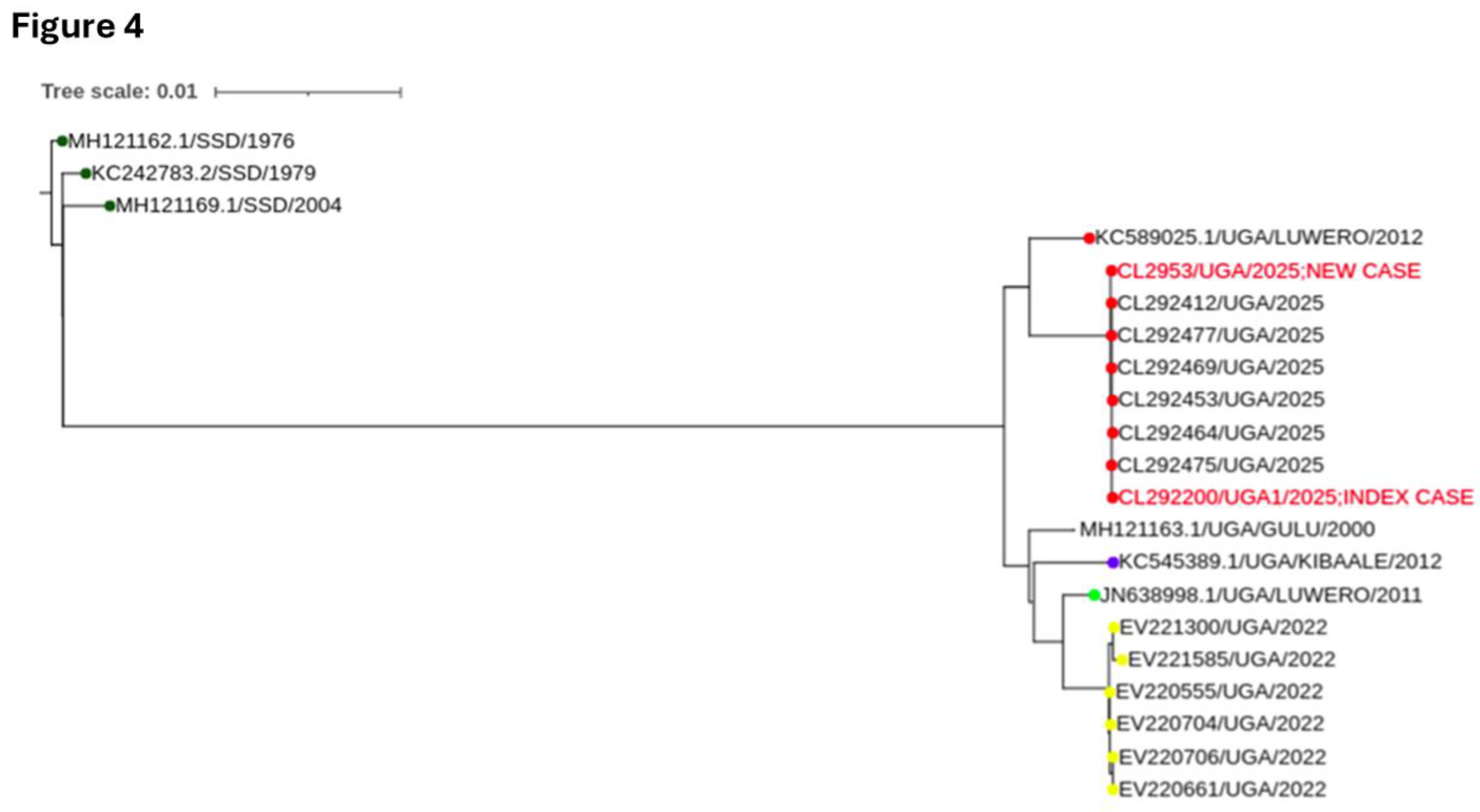

Uganda has been the epicenter of Ebola Sudan virus (SUDV), documenting seven outbreaks to date, with healthcare workers consistently identified as the highest-risk population [

25,

26]. For the most recent outbreaks, CPHL has played a pivotal role in the response, notably in 2025 response, delivering genomic sequencing data within 24 hours of diagnosis. Phylogenetic analysis confirmed SUDV and revealed that the 2025 viral genomes closely clustered with sequences from the 2012 Luwero outbreak, with a high degree of nucleotide identity. Additionally, the 2025 outbreak does not cluster with sequences from the 2022 outbreak, suggesting no direct evolutionary linkages [

10] (

Figure 4). Interestingly, we also observed that the 2022 sequences aligned with the Luwero 2011 genomes, suggesting a potential shared epidemiological origin, Luwero, possibly through a common reservoir, independent spillover events, or endemic circulation rather than a direct lineage continuation. Overall, our findings underpin the need for expanded genomic surveillance to better understand the mechanisms driving SUDV re-emergence in Uganda.

Cholera Outbreak Investigation

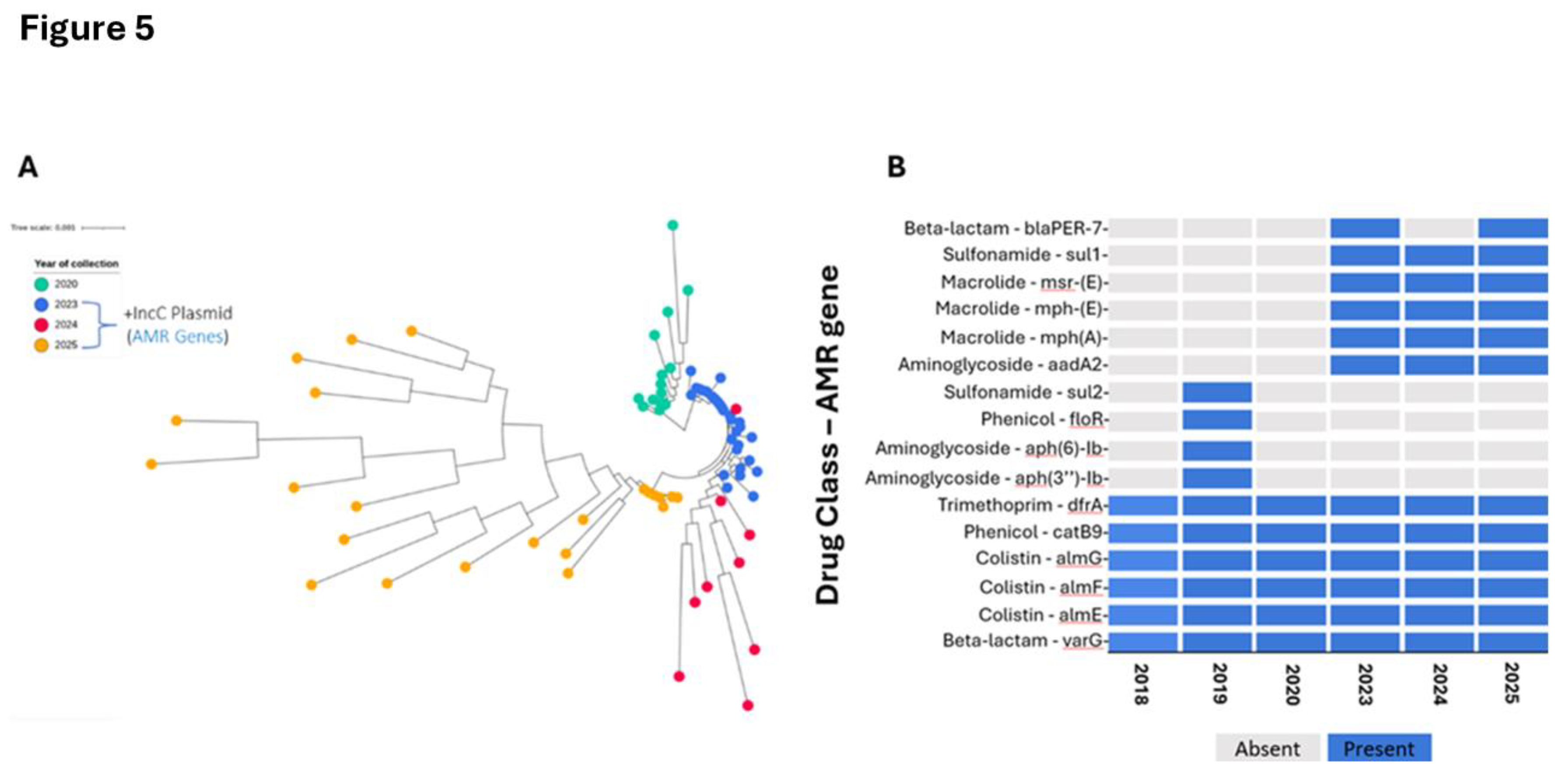

NHLDS-CPHL through the CholGen consortium, an initiative led by Africa CDC under the Africa PGI, has built significant capacity for cholera genomics, which focussed on wet lab, metadata collection and bioinformatics analysis [

27,

28]. In 2023-2025, CPHL deployed genomic analysis for the first time during cholera outbreaks, with results promptly confirming that the T13 (AFR13) lineage was responsible for these outbreaks similar historical isolates previously identified through the CholGen regional analysis, suggesting persistent circulation of this strain within Uganda. Additional genomic analysis revealed the presence of the IncA/C plasmid, a common carrier of multidrug resistance in cholera among resulting in the detection of aad2, blaPER-7, mph(A), mph(E), mrs(E), and sul1 [

29,

30] (

Figure 5B). These findings underscore the importance of ongoing AMR surveillance to guide effective treatment strategies and outbreak management.

Genomics in Outbreak Response of Unknown Aetiologies

Timely identification of infectious agents in outbreak scenarios, especially those with unknown aetiologies, remains a critical gap in many low-resource settings. Leveraging genomics has enabled rapid, precise detection of causative pathogens, even in complex cases involving co-infections.

Coinfection of Rotavirus A and Coxsackievirus at a baby’s home: NHLDS-CPHL has utilized targeted enrichment-based sequencing for rapid detection of pathogens agents of unknown causes, exacerbated by limited diagnostics. In August 2023, children in a baby’s home exhibited symptoms including acute watery diarrhoea, vomiting, as well as general body weakness with no definitive diagnosis. Stool samples were collected and subjected to the Illumina Viral Surveillance Sequencing Panel (VSP) at NHLDS-CPHL and results confirmed presence of rotavirus A, a common causative agent of diarrhoeal disease in infants, as the primary pathogen and revealed a co-infection with enterovirus (coxsackievirus) in some cases (

Table 1), resulting in guided implementation of targeted control strategies such as heightened hygiene interventions and promotion of vaccination to prevent further transmission. The dual-pathogen presence observed in this investigation highlighted the probable multifaceted nature, underpinning the need for considering concurrent infections during outbreak response and management.

Bacillus cereus in a suspected food poisoning investigation: In July 2023, a severe food poisoning outbreak affecting over 100 students occurred at one of the secondary schools in Uganda’s Mukono District, characterized by bloody diarrhea, abdominal pain, and vomiting. Specimens including cooked food, raw ingredients, and stool samples were analyzed by the CPHL using a repurposed Respiratory Pathogen ID/AMR Enrichment Panel (Illumina, Inc.), capable of simultaneously detecting 280+ pathogens and 2,000+ AMR markers in a single assay. Genomic analysis, corroborated by microbial culture results, identified

Bacillus cereus in the cooked food but not in raw ingredients, indicating that contamination occurred during food preparation or following cooking rather than from raw ingredients (

Table 2). These findings clarified the outbreak’s origins and provided evidence-based guidance for implementing preventive measures in schools and similar congregate settings, particularly regarding improved food handling and preparation practices.

Genomics in Real-Time Mpox Outbreak Management

Uganda confirmed its first case of Mpox on August 2, 2024, and as of February 2025, the outbreak had spread over 56 districts across the country. A total of 732 PCR-confirmed Mpox-positive cases were subjected to hybrid-capture method to isolate genomes and subsequently processed using the artic-mpxv-illumina-nf workflow [

31] achieving > 90% genome coverage for majority samples. Genomic analysis revealed that all positive samples belonged to Clade 1b, with the emergence of 3 temporally distributed distinct clusters as well as APOBEC-3 mutations

(Figure 6), which is suggestive of ongoing human-to-human transmission and viral evolution with probable immune evasion at play [

32,

33]. Overall, these findings guided public health informed-decision making regarding which diagnostic strategies to be deployed in Uganda, given the varying sensitivities and specificities of available tests for different Mpox clades.

Genomics in Malaria Surveillance

Uganda adopted artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) per WHO guidelines [

34,

35]. However, efficacy is increasingly threatened by partial artemisinin resistance associated with

Plasmodium falciparum Kelch 13 (PfK13) mutations and markers of partner drug resistance [

36,

37]. Through the Implementing of Malaria Molecular SurveillancE in Uganda (IMMRSE-U) project, the NHLDS-CPHL and partners identified spatiotemporal increases in PfK13 mutations, specifically A675V and C469Y in northern Uganda; R561H, P441L, and C469F in the west; and R622I in 2023 [

37]. Additionally, genomic metrics such as complexity of infection (COI) were found to correlate strongly with malaria prevalence [

38]. Overall, these findings support data-driven subnational stratification and complement routine epidemiologic surveillance, providing insights leveraged by the National Malaria Elimination Division (NMED) to design therapeutic efficacy studies and formulate new elimination strategies.

Surveillance among refugees revealed distinct resistance profiles, characterized by aminoquinoline markers in refugees from South Sudan and antifolate markers in those from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), with moderate artemisinin partial resistance observed in both groups. These profiles differed from those in local host communities, highlighting the risk of resistance importation Such monitoring is essential to inform targeted treatment strategies, improve refugee health, and limit the spread of antimalarial drug resistance within Uganda [

39].

Rigorous technical evaluations of genotyping tools are essential for establishing reliable surveillance infrastructure. We assessed the sensitivity, specificity, and precision of the Multiplexed Amplicons for Drugs, Diagnostics, Diversity, and Differentiation using High-Throughput Targeted Resequencing (MAD4HatTeR) [

40] and the Molecular Inversion Probe (MIP) assay [

41]. Our findings define distinct utilities for each: MAD4HatTeR is optimal for therapeutic efficacy studies and detecting minority alleles, while the MIP assay is preferred for investigating novel mutations and phenotypic-genotypic associations [

42].

In parallel, we evaluated diagnostic accuracy by monitoring

pfhrp2/3 gene deletions, which threaten the performance of antigen-based Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs) [

43]. Although deletions are present, their prevalence remains below the WHO 5% threshold required for policy modification [

44,

45]. Crucially, field performance evaluations confirmed that the Bioline Malaria Ag P.f/Pan RDT maintains high sensitivity and reliability in Uganda [

46]. Together, these findings validate our technical capacity and underscore the necessity of continuous monitoring to sustain diagnostic integrity.

Genomics for Liquid Biopsy in Oncology Diagnosis

Within the Aggressive Infection Related-East African Lymphoma (AIREAL) consortium, NHLDS-CPHL has shown that liquid biopsies, analyzing circulating viral DNA, offer a non-invasive and faster route to early diagnosis of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-driven Burkitt’s lymphoma (BL). Traditional BL diagnosis relies on invasive tissue biopsies, often causing significant delays and potentially leading to less targeted treatment with poorer outcomes [

47,

48]. The evaluated liquid biopsy panel achieved 87.5% sensitivity and 84.6% specificity for EBV-driven BL, presenting clinicians, especially in areas with limited pathology resources, with a more precise diagnostic option for better patient management [

49].

Discussion and Conclusion

This review underscores Uganda’s progress in integrating genomics into its public health ecosystem, demonstrating the technology’s transformative potential in resource-limited settings. Enhanced laboratory capacity, local bioinformatics infrastructure, and strengthened surveillance have optimized diagnostic accuracy and outbreak response. Case studies spanning COVID-19, HIV, malaria, Ebola, Mpox, rotavirus, and cholera illustrate the critical role of genomics in tracking variants, guiding treatment, investigating outbreaks, and monitoring drug resistance.

Despite these achievements, challenges regarding sustainable funding and ethical governance persist. Addressing these requires diversified financing mechanisms through public-private partnerships, robust data governance frameworks to ensure privacy, and the development of local reference databases to enhance interpretation accuracy. Furthermore, knowledge transfer programs prioritizing self-sufficiency are essential for long-term sustainability.

Future advancements will rely on cross-sectoral collaborations and emerging technologies. Innovations such as portable diagnostics (e.g., lab-on-a-chip) and Artificial Intelligence (AI) for predictive analytics are poised to revolutionize rapid, on-site detection and real-time surveillance, while Virtual Reality (VR) offers scalable training solutions. The NHLDS-CPHL is actively cultivating an innovative workforce to develop cost-effective, in-house solutions, thereby reducing reliance on external resources. Ultimately, this NHLDS-CPHL-led initiative serves as a replicable model for Africa, proving that coordinated investment in genomic infrastructure yields substantial returns in public health resilience and preparedness.

Ethical Considerations

All investigations complied with ethical guidelines, obtaining informed consent where feasible. For public health surveillance and outbreak response activities, a waiver of informed consent was granted by the Uganda National Health Laboratory Services Research and Ethics Committee (UNHLS-2025-133). Participant privacy was ensured through data anonymization and compliance with data protection regulations.

Acknowledgments

The work presented here was generously supported by the Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention through the Africa Pathogen Genomics Initiative, African Society of Laboratory Medicine, the Gates Foundation, the Global Fund, and the Government of Uganda. We also acknowledge the leadership and support of the Department of National Health Laboratory and Diagnostic Services and the Ministry of Health.

Author Contributions

AS, AA and ISs conceived the topic, designed the scope and drafted the initial manuscript. AS, AA, SK, HRO, GT and CM conducted the data extraction. AS, AA, SK, HRO, JS, WT, GT, SW, MM, IS, JMK, CM, ST, TK, AN contributed to data analysis, interpretation of findings, and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Availability

Aggregate genomic and associated surveillance data are available upon request (sewyisaac@yahoo.co.uk), subject to data sharing policies and ethical approvals.

References

- Murray CJL. The Global Burden of Disease Study at 30 years. Nat Med (2022) 28:2019–2026. [CrossRef]

- Max Roser, Hannah Ritchie, Fiona Spooner. Burden of Disease. Our World in Data (2021).

- Mremi IR, George J, Rumisha SF, Sindato C, Kimera SI, Mboera LEG. Twenty years of integrated disease surveillance and response in Sub-Saharan Africa: challenges and opportunities for effective management of infectious disease epidemics. One Health Outlook (2021) 3:22. [CrossRef]

- Grad YH, Lipsitch M. Epidemiologic data and pathogen genome sequences: a powerful synergy for public health. Genome Biol (2014) 15:538. [CrossRef]

- Gardy JL, Loman NJ. Towards a genomics-informed, real-time, global pathogen surveillance system. Nat Rev Genet (2018) 19:9–20. 10.1038/nrg.2017.88Armstrong GL, Maccannell DR, Taylor J, Carleton HA, Neuhaus EB, Bradbury RS, Posey JE, Gwinn M, Summary MPH. Pathogen Genomics in Public Health. N Engl J Med (2019) 381:2569–2580. [CrossRef]

- Armstrong GL, Maccannell DR, Taylor J, Carleton HA, Neuhaus EB, Bradbury RS, Posey JE, Gwinn M, Summary MPH. Pathogen Genomics in Public Health. N Engl J Med (2019) 381:2569–2580. [CrossRef]

- Baker KS, Jauneikaite E, Hopkins KL, Lo SW, Sánchez-Busó L, Getino M, Howden BP, Holt KE, Musila LA, Hendriksen RS, et al. Genomics for public health and international surveillance of antimicrobial resistance. Lancet Microbe (2023) 4:e1047–e1055. [CrossRef]

- Inzaule SC, Tessema SK, Kebede Y, Ogwell Ouma AE, Nkengasong JN. Genomic-informed pathogen surveillance in Africa: opportunities and challenges. Lancet Infect Dis (2021) 21: e281–e289. 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30939-7Onywera H, Ondoa P, Nfii F, Ogwell A, Kebede Y, Christoffels A, Tessema SK. Boosting pathogen genomics and bioinformatics workforce in Africa. Lancet Infect Dis (2024) 24: e106–e112. [CrossRef]

- Onywera H, Ondoa P, Nfii F, Ogwell A, Kebede Y, Christoffels A, Tessema SK. Boosting pathogen genomics and bioinformatics workforce in Africa. Lancet Infect Dis (2024) 24:e106–e112. [CrossRef]

- Kanyerezi S, Ayitewala A, Ssemaganda A, Makoha C, Kabahita JM, Murungi M, Tusabe GW, Tenywa W, Oundo HR, Sseruyange J, et al. Near Real-Time Genomic Characterization of the 2025 Sudan Ebolavirus Outbreak in Uganda’s Index Case: Insights into Evolutionary Origins. https://virological.org/t/near-real-time-genomic-characterization-of-the-2025-sudan-ebolavirus-outbreak-in-uganda-s-index-case-insights-into-evolutionary-origins/990 (2025).

- Kanyerezi S, Sserwadda I, Ssemaganda A, Seruyange J, Ayitewala A, Oundo HR, Tenywa W, Kagurusi BA, Tusabe G, Were S, et al. HIV-DRIVES: HIV drug resistance identification, variant evaluation, and surveillance pipeline. Access Microbiol (2024) 6:000815. v3. [CrossRef]

- Africa Centres for Disease Control. Integrated Genomic Surveillance for Outbreak Detection (DETECT). The Africa Pathogen Genomics Initative (2024).

- World Health Organization. WHO chief declares end to COVID-19 as a global health emergency. https://news.un.org/en/story/2023/05/1136367 (2023).

- World Health Organization. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants. https://www.who.int/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants/ (2024).

- World Health Organization. JN.1 Initial Risk Evaluation. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/18122023_jn1_ire_clean.pdf?sfvrsn=6103754a_3 (2023).

- Naveed Siddiqui A, Musharaf I, Gulumbe BH. The JN.1 variant of COVID-19: immune evasion, transmissibility, and implications for global health. Ther Adv Infect Dis (2025) 12:. [CrossRef]

- Manyana S, Gounder L, Pillay M, Manasa J, Naidoo K, Chimukangara B. HIV-1 Drug Resistance Genotyping in Resource Limited Settings: Current and Future Perspectives in Sequencing Technologies. Viruses (2021) 13:. [CrossRef]

- Aboulker J-P. Drug-resistant genotyping in HIV-1 therapy. The Lancet (1999) 354:1120. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Updated recommendations on first line and second-line antiretroviral regimens and post-exposure prophylaxis and recommendations on early infant diagnosis of HIV: interim guidelines: supplement to the 2016 consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection. (2018).

- Phillips AN, Venter F, Havlir D, Pozniak A, Kuritzkes D, Wensing A, Lundgren JD, De Luca A, Pillay D, Mellors J, et al. Risks and benefits of dolutegravir-based antiretroviral drug regimens in sub-Saharan Africa: a modelling study. Lancet HIV (2019) 6: e116–e127. [CrossRef]

- Vitoria M, Hill A, Ford N, Doherty M, Clayden P, Venter F, Ripin D, Flexner C, Domanico PL. The transition to dolutegravir and other new antiretrovirals in low-income and middle-income countries: What are the issues? AIDS (2018) 32:1551–1561. [CrossRef]

- Ayitewala A, Ssewanyana I, Kiyaga C. Next generation sequencing based in-house HIV genotyping method: validation report. AIDS Res Ther (2021) 18:. [CrossRef]

- Parkin NT, Avila-Rios S, Bibby DF, Brumme CJ, Eshleman SH, Harrigan PR, Howison M, Hunt G, Ji H, Kantor R, et al. Multi-Laboratory Comparison of Next-Generation to Sanger-Based Sequencing for HIV-1 Drug Resistance Genotyping. Viruses (2020) 12:. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health. Consolidated Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of HIV and AIDS in Uganda. (2022).

- Abdullah W, W BP, Kenneth K, Kayiira M, Hellen A-T, Daniel K, T SM, D KJ, Peter W, R BR, et al. Sudan Virus Disease among Health Care Workers, Uganda, 2022. New England Journal of Medicine (2024) 391:285–287. [CrossRef]

- Kyobe Bosa Henry, Wayengera Misaki, Nabadda Suzan, Olaro Charles, Bahatungire Rony, Kalungi Samuel, Bakamutumaho Barnabas, Muruta Allan, Kagirita Atek, Muwonge Haruna, et al. Sudan Ebola virus disease outbreak in Uganda a role for cryptic transmission. Nat Med (2025).

- Tanui CK, Tessema SK, Tegegne MA, Tebeje YK, Kaseya J. Unlocking the power of molecular and genomics tools to enhance cholera surveillance in Africa. Nat Med (2023) 29:2387–2388. [CrossRef]

- Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Scientists Call for Broader and Stronger Network for Genomic Surveillance of Cholera in Africa. https://africacdc.org/news-item/scientists-call-for-broader-and-stronger-network-for-genomic-surveillance-of-cholera-in-africa/# (2024).

- De R. Mobile Genetic Elements of Vibrio cholerae and the Evolution of Its Antimicrobial Resistance. Frontiers in Tropical Diseases (2021) 2:. [CrossRef]

- Mboowa G, Matteson NL, Tanui CK, Kasonde M, Kamwiziku GK, Akanbi OA, Chitio JJE, Kagoli M, Essomba RG, Ayitewala A, et al. Multicountry genomic analysis underscores regional cholera spread in Africa. (2024). [CrossRef]

- ARTIC Network Project. artic-mpxv-illumina-nf. (2025).

- Jahankir MJB, Sounderrajan V, Rao SS, Thangam T, Kamariah N, Kurumbati A, Harshavardhan S, Ashwin A, Jeyaraj S, Parthasarathy K. Accelerated mutation by host protein APOBEC in Monkeypox virus. Gene Rep (2024) 34:101878. [CrossRef]

- Suspène R, Raymond KA, Boutin L, Guillier S, Lemoine F, Ferraris O, Tournier JN, Iseni F, Simon-Lorière E, Vartanian JP. APOBEC3F Is a Mutational Driver of the Human Monkeypox Virus Identified in the 2022 Outbreak. Journal of Infectious Diseases (2023) 228:1421–1429. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO guidelines for malaria. WHO Global Malaria Programme. (2021).

- National Malaria Control Division Ministry of Health Uganda. Malaria reduction and elimination strategic plan: 2021-2025. (2021).

- Agaba BB, Travis J, Smith D, Rugera SP, Zalwango MG, Opigo J, Katureebe C, Mpirirwe R, Bakary D, Antonio M, et al. Emerging threat of artemisinin partial resistance markers (pfk13 mutations) in Plasmodium falciparum parasite populations in multiple geographical locations in high transmission regions of Uganda. Malar J (2024) 23:330. [CrossRef]

- Conrad MD, Asua V, Garg S, Giesbrecht D, Niaré K, Smith S, Namuganga JF, Katairo T, Legac J, Crudale RM, et al. Evolution of Partial Resistance to Artemisinins in Malaria Parasites in Uganda. New England Journal of Medicine (2023) 389:722–732. [CrossRef]

- Kiyaga, S., Mbabazi, M., Katairo, T., Kabbale, K.D., Asua, V., Nsengimaana, B., Wiringilimaana, I., Semakuba, F.Ddumba., Mwubaha, C., Nakasaanya, J., et al. (2025). Accuracy of Plasmodium falciparum genetic data for estimating parasite prevalence and malaria incidence in Uganda. Preprint. [CrossRef]

- Tukwasibwe S, Garg S, Katairo T, Asua V, Kagurusi BA, Mboowa G, Crudale R, Tumusiime G, Businge J, Alula D. Varied Prevalence of antimalarial drug resistance markers in different populations of newly arrived refugees in Uganda. J Infect Dis (2024) 230:497–504.

- Aranda-Díaz A, Neubauer Vickers E, Murie K, Palmer B, Hathaway N, Gerlovina I, Boene S, García-Ulloa M, Cisteró P, Katairo T, et al. Sensitive and modular amplicon sequencing of Plasmodium falciparum diversity and resistance for research and public health. Sci Rep (2025) 15:10737. [CrossRef]

- Aydemir O, Janko M, Hathaway NJ, Verity R, Mwandagalirwa MK, Tshefu AK, Tessema SK, Marsh PW, Tran A, Reimonn T, et al. Drug-Resistance and Population Structure of Plasmodium falciparum Across the Democratic Republic of Congo Using High-Throughput Molecular Inversion Probes. J Infect Dis (2018) 218:946–955. [CrossRef]

- Katairo T, Asua V, Nsengimaana B, Tukwasibwe S, Semakuba FD, Wiringilimaana I, Kagurusi BA, Mwubaha C, Nakasaanya J, Garg S. Performance of molecular inversion probe DR23K and Paragon MAD4HatTeR Amplicon sequencing panels for detection of Plasmodium falciparum mutations associated with antimalarial drug resistance. Malar J (2025) 24:188.

- Agaba BB, Anderson K, Gresty K, Prosser C, Smith D, Nankabirwa JI, Nsobya S, Yeka A, Opigo J, Gonahasa S, et al. Molecular surveillance reveals the presence of pfhrp2 and pfhrp3 gene deletions in Plasmodium falciparum parasite populations in Uganda, 2017–2019. Malar J (2020) 19:300. [CrossRef]

- Agaba, Bosco B, Nankabirwa JI, Yeka A, Nsobya S, Gresty K, Anderson K, Mbaka P, Prosser C, Smith D, et al. Limitations of rapid diagnostic tests in malaria surveys in areas with varied transmission intensity in Uganda 2017-2019: Implications for selection and use of HRP2 RDTs. PLoS One (2021) 15: e0244457-. [CrossRef]

- Agaba BB, Smith D, Travis J, Pasay C, Nabatanzi M, Arinaitwe E, Ssewanyana I, Nabadda S, Cunningham J, Kamya MR, et al. Limited threat of Plasmodium falciparum pfhrp2 and pfhrp3 gene deletion to the utility of HRP2-based malaria RDTs in Northern Uganda. Malar J (2024) 23:3. [CrossRef]

- Kabbale KD, Nsengimaana B, Semakuba FD, Kagurusi BA, Mwubaha C, Wiringilimaana I, Katairo T, Kiyaga S, Mbabazi M, Gonahasa S. Field evaluation of the Bioline Malaria Ag Pf/Pan rapid diagnostic test causes of microscopy discordance and performance in Uganda. Malar J (2025) 24:138.

- Ogwang MD, Zhao W, Ayers LW, Mbulaiteye SM. Accuracy of Burkitt Lymphoma Diagnosis in Constrained Pathology Settings: Importance to Epidemiology. Arch Pathol Lab Med (2011) 135:445–450. [CrossRef]

- Mawalla WF, Morrell L, Chirande L, Achola C, Mwamtemi H, Sandi G, Mahawi S, Kahakwa A, Ntemi P, Hadija N, et al. Treatment delays in children and young adults with lymphoma: a report from an East Africa lymphoma cohort study. Blood Adv (2023) 7:4962–4965. [CrossRef]

- Chamba CC, Howard K, Mawalla WF, Christopher H, Seruyange J, Josephat E, Legason ID, Ogwang M, Ayitewala A, Mremi A, et al. Performance of a Liquid Biopsy Diagnostic Prediction Model for EBV-Positive Burkitt Lymphoma in Sub-Saharan Africa. Blood (2023) 142:4364. [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Target enrichment for the stool specimen collected from children’s home in Uganda.

Table 1.

Target enrichment for the stool specimen collected from children’s home in Uganda.

| Lab ID |

Pathogen Detected |

| RPGS-222 |

Rotavirus A; Enterovirus (Coxsackieviruses) |

| RPGS-223 |

Rotavirus A; Enterovirus (Coxsackieviruses) |

| RPGS-224 |

Rotavirus A; Enterovirus (Coxsackieviruses) |

| RPGS-225 |

Rotavirus A; Enterovirus (Coxsackieviruses) |

| RPGS-226 |

Enterovirus (Coxsackieviruses) |

| RPGS-227 |

Rotavirus A; Enterovirus (Coxsackieviruses) |

| RPGS-228 |

Enterovirus (Coxsackieviruses) |

| RPGS-230 |

Enterovirus (Coxsackieviruses) |

| RPGS-231 |

Rotavirus A; Enterovirus (Coxsackieviruses) |

| RPGS-232 |

Enterovirus (Coxsackieviruses) |

Table 2.

Genomic and culture results in food exhibits sampled.

Table 2.

Genomic and culture results in food exhibits sampled.

| Exhibit material |

Sample id |

Culture |

Genomics |

| Cooked posho |

D |

NIL |

Bacillus cereus |

| C |

NIL |

Bacillus cereus |

| Cooked beans |

A |

Bacillus cereus |

Bacillus cereus |

| Uncooked Posho flour |

N3 |

Bacillus cereus |

NIL |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).