Submitted:

12 December 2025

Posted:

15 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- Freedom from hunger and thirst

- Freedom from discomfort

- Freedom from pain, injury, and disease

- Freedom to express normal behavior

- Freedom from fear and distress

2. Materials and Methods

- Cases submitted between 2008-2025

- Cases involved the following domestic animal species: dogs, cats, horses, cows, sheep, goat, pigs, and pet birds.

-

Cases had to be at least one of the following:

- ○

- Police cases, where there was a police report made, and police was involved in the process, or

- ○

- The submitted case history indicated some type of animal abuse as a possible differential for COD or MOI, or

- ○

- The veterinary pathologist, after doing the necropsy, suspected the COD or MOI was related to animal abuse.

- The cases included completed necropsy reports.

- Suspected cases with partial reports or without reports accompanying the case number

- Biopsy or cytology cases of live animals

- Cases that were suspected initially to be related to animal abuse, but that after necropsy, another COD unrelated to animal abuse was found.

- Cases involving exotic animal species or environmentally sensitive species, as these are covered under other laws[9].

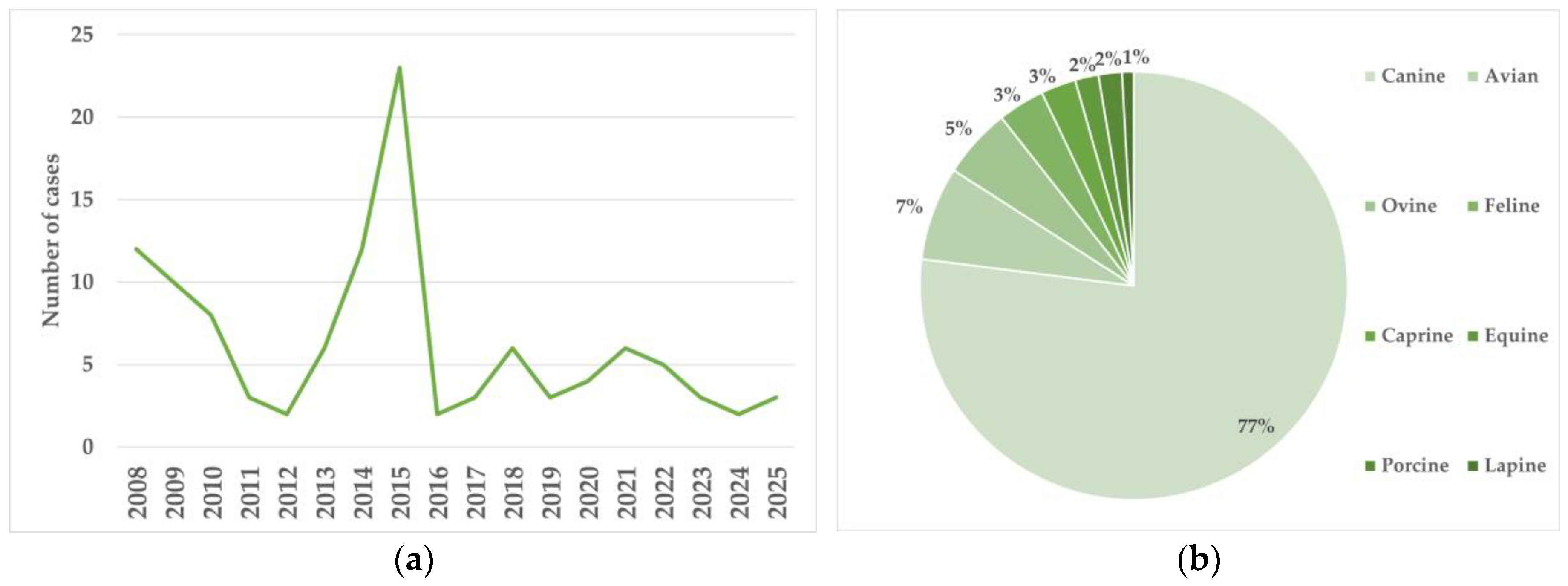

- Cases per year

- Species

-

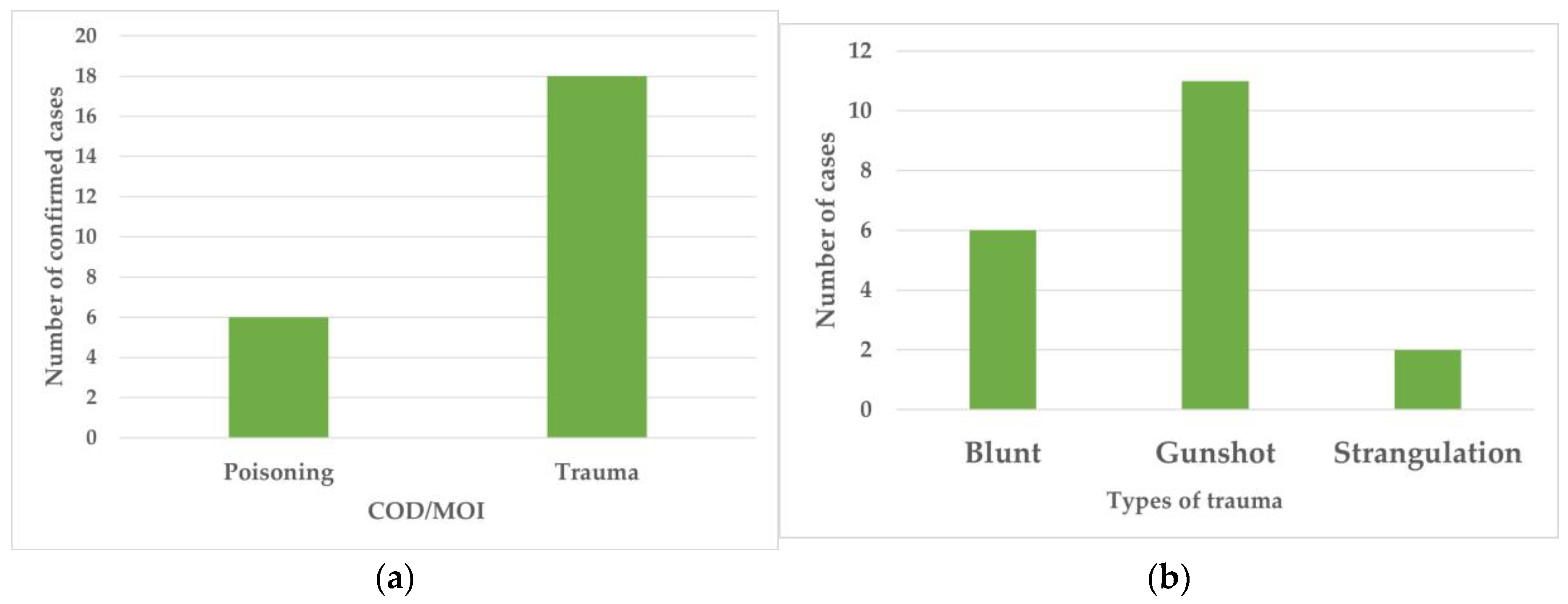

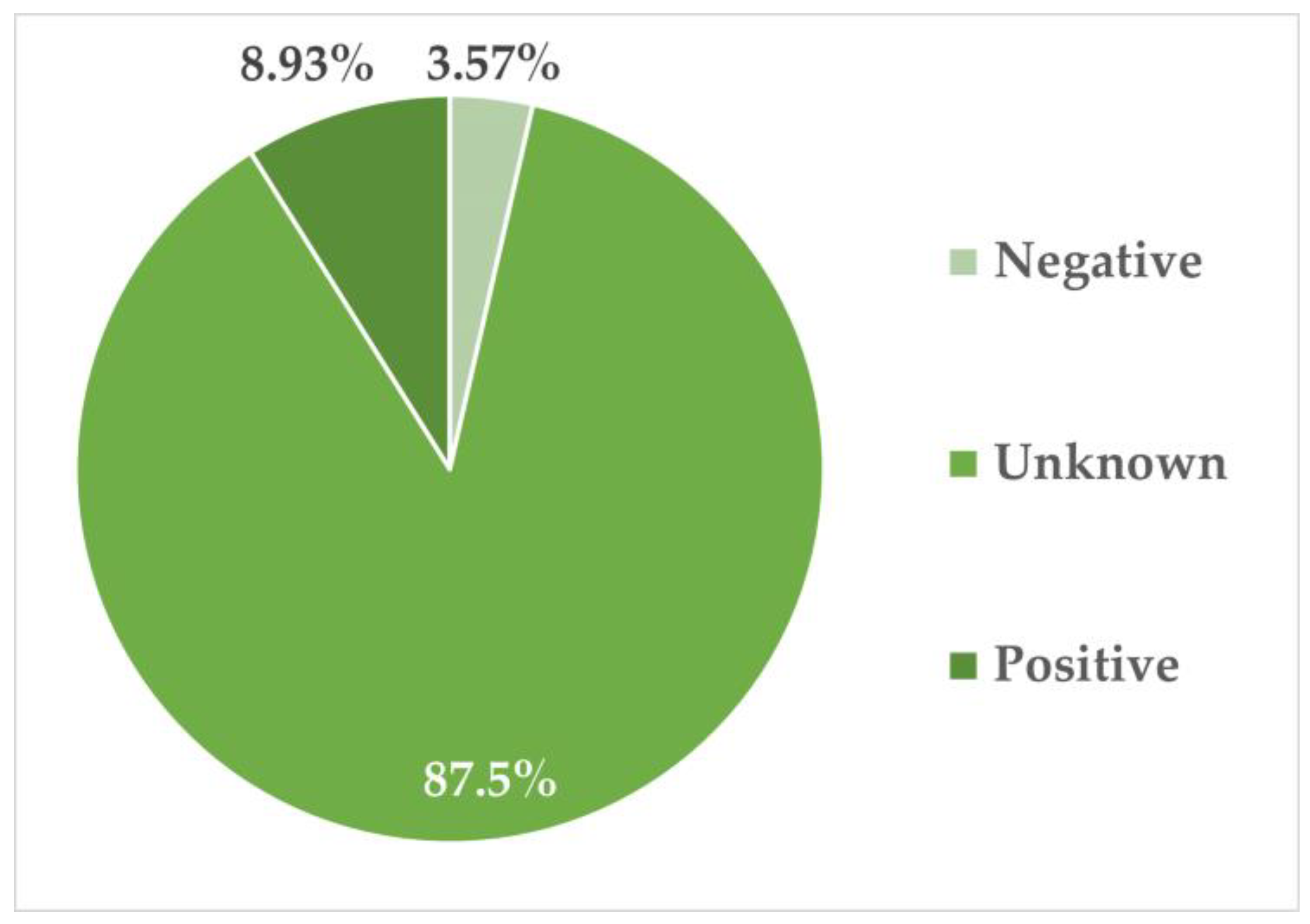

Cause of death (COD) or mode of injury (MOI) if euthanized

- ○

- If toxicology was done and if results were obtained

-

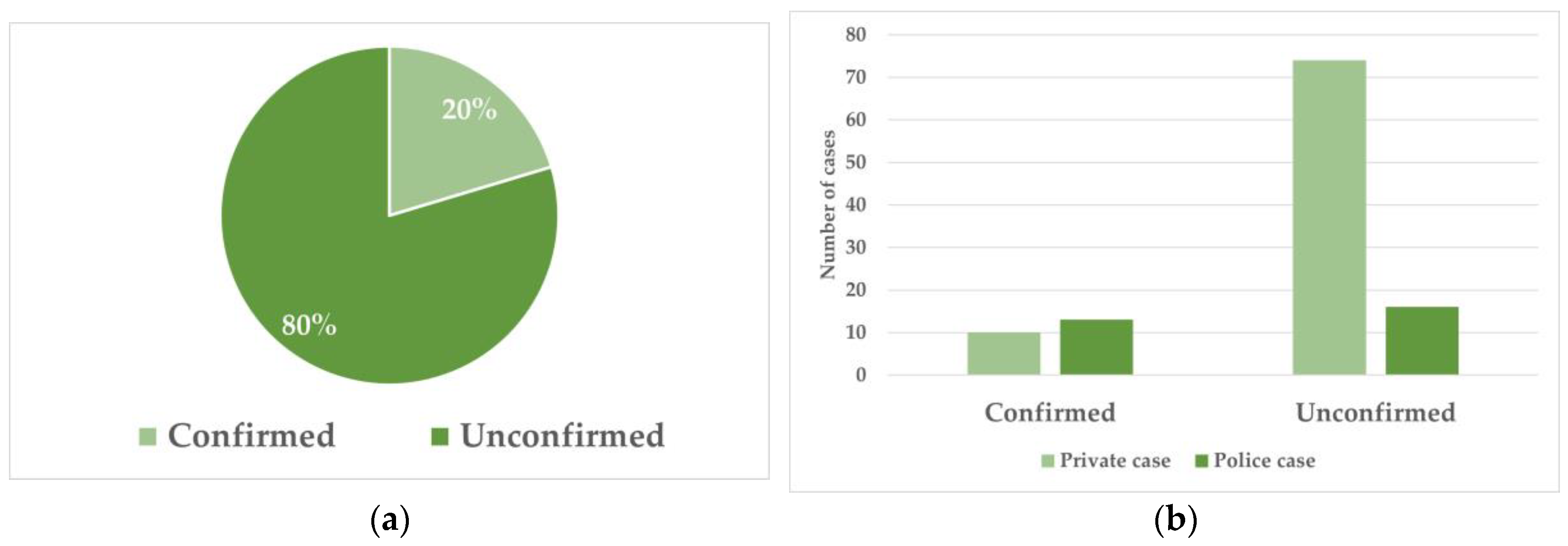

Police case vs private cases

- ○

- Police cases are those that were referred by the police because a report was made or the death involved some criminal activity (robbery for example) where the police was called.

- ○

- Private cases are those submitted by regular citizens, usually the owners of these animals, but sometimes rescue organizations that worked in the area the animal was found, if the animals were strays.

3. Results

3.1. Total Number of Cases Between 2008-2025 and Species

3.2. Confirmed vs Unconfirmed Cases

3.3. Cause of Death/Mode of Injury

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| DOAJ | Directory of open access journals |

| TLA | Three letter acronym |

| LD | Linear dichroism |

References

- Lockwood, R.; Arkow, P. Animal Abuse and Interpersonal Violence: The Cruelty Connection and Its Implications for Veterinary Pathology. Vet Pathol 2016, 53, 910–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arkow, P. Recognizing and responding to cases of suspected animal cruelty, abuse, and neglect: what the veterinarian needs to know. Vet Med (Auckl) 2015, 6, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cleary, M.; Thapa, D.K.; West, S.; Westman, M.; Kornhaber, R. Animal abuse in the context of adult intimate partner violence: A systematic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior 2021, 61, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota-Rojas, D.; Monsalve, S.; Lezama-Garcia, K.; Mora-Medina, P.; Dominguez-Oliva, A.; Ramirez-Necoechea, R.; Garcia, R.C.M. Animal Abuse as an Indicator of Domestic Violence: One Health, One Welfare Approach. Animals (Basel) 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerdin, J.A.; McDonough, S.P. Forensic pathology of companion animal abuse and neglect. Vet Pathol 2013, 50, 994–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otteman, K.; Hedge, Z.; Fielder, L. Animal Basics. In Animal Cruelty Investigations: Approach from Victim to Verdict, 1st ed.; Otteman, K., Fielder, L., Lewis, E., Eds.; Wiley: Newark, NJ, 2022; pp. 14–24. [Google Scholar]

- Summary Offences Act of 1921, Chapter11:02, Sections 79-90 1920.

- Animal (Diseases, Importation, Health and Welfare) Act, No. 21 of 2020. 2020.

- Environmental Management Act. 2000; 269.

- McDonough, S.P.; McEwen, B.J. Veterinary Forensic Pathology: The Search for Truth. Vet Pathol 2016, 53, 875–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brownlie, H.W.; Munro, R. The Veterinary Forensic Necropsy: A Review of Procedures and Protocols. Vet Pathol 2016, 53, 919–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooper, J.E.; Cooper, M.E. Forensic veterinary medicine: a rapidly evolving discipline. Forensic Sci Med Pathol 2008, 4, 75–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otteman, K.; Hedge, Z. Veterinary Forensic Necropsy. In Animal Cruelty Investigations: Approach from Victim to Verdict, 1st ed.; Otteman, K., Fielder, L., Lewis, E., Eds.; Wiley: Newark, NJ, 2022; pp. 158–179. [Google Scholar]

- Frontera-Acevedo, K; Gyan, L; Suepaul, R. A Review Of The Cause Of Death And Mode Of Injury Of Suspected Animal Abuse Cases In Trinidad And Tobago. Poster presented at 67th ACVP Annual Meeting, New Orleans, LA, United States, 2016 Dec 3-9. [Google Scholar]

- Araujo, D.; Lima, C.; Mesquita, J.R.; Amorim, I.; Ochoa, C. Characterization of Suspected Crimes against Companion Animals in Portugal. Animals (Basel) 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rial-Berriel, C.; Acosta-Dacal, A.; Zumbado, M.; Henriquez-Hernandez, L.A.; Rodriguez-Hernandez, A.; Macias-Montes, A.; Boada, L.D.; Travieso-Aja, M.D.M.; Martin-Cruz, B.; Suarez-Perez, A.; et al. Epidemiology of Animal Poisonings in the Canary Islands (Spain) during the Period 2014-2021. Toxics 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutchinson, G.; Daisley, H.; Simeon, D.; Simmonds, V.; Shetty, M.; Lynn, D. High rates of paraquat-induced suicide in southern Trinidad. Suicide Life Threat Behav 1999, 29, 186–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pesticide - Gramoxone. Available online: https://health.gov.tt/cfdd/pesticides/search/7188 (accessed on November 27).

- Bradley-Siemens, N.; Brower, A.I. Veterinary Forensics: Firearms and Investigation of Projectile Injury. Vet Pathol 2016, 53, 988–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ressel, L.; Hetzel, U.; Ricci, E. Blunt Force Trauma in Veterinary Forensic Pathology. Vet Pathol 2016, 53, 941–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McEwen, B.J. Nondrowning Asphyxia in Veterinary Forensic Pathology: Suffocation, Strangulation, and Mechanical Asphyxia. Vet Pathol 2016, 53, 1037–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kissoon, C. Animal atrocity. Trinidad Daily Express. 11/4/2020 2020.

- Almeida, D.C.; Torres, S.M.F.; Wuenschmann, A. Retrospective analysis of necropsy reports suggestive of abuse in dogs and cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2018, 252, 433–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).