1. Introduction

Video games have evolved from simple entertainment systems into sophisticated interactive media that can elicit complex emotional responses. Unlike passive media such as film or literature, games require active participation, creating a direct feedback loop between player actions, game states, and emotional outcomes. This interactivity offers unprecedented opportunities for designers to create experiences tailored to individual affective states. However, traditional approaches to game adaptation—such as Dynamic Difficulty Adjustment (DDA)—rely primarily on performance metrics, including success rates and time-to-completion. While effective for maintaining balance, these metrics fail to account for the full spectrum of the user experience; a player may perform mechanically well while experiencing frustration, anxiety, or boredom.

To address this limitation, this research explores a novel approach at the intersection of affective computing and procedural game design: an adaptive system that modifies gameplay based on real-time emotional recognition. The central contribution of this paper is a closed-loop architecture designed to (1) monitor observable behavior, (2) infer the player’s affective state in near real-time, and (3) manipulate game parameters to induce targeted emotional transitions.

Distinct from traditional "Flow" systems that merely seek to balance challenge and skill, our proposed model aims to orchestrate specific emotional journeys—for example, steering a player from "anger" to "joy" and subsequently to "fear." This approach not only addresses "emotional dissonance" in entertainment but also has significant implications for serious games, including exposure therapy and emotional regulation training.

2. Related Work

The optimization of player experience has evolved from static difficulty settings to sophisticated adaptive systems at the intersection of Artificial Intelligence (AI), cognitive psychology, and data science. Historically, the primary objective of such systems has been to maintain the player in a state of "Flow"—a psychological state of intense focus achieved when challenge aligns with skill [

1,

2]. However, recent advancements indicate a shift toward active emotional regulation and induction. This section reviews the trajectory of these technologies, from performance-based adjustments to modern affective computing frameworks powered by deep learning.

2.1. Foundations of Player Experience and Flow

The theoretical foundation for most adaptive systems is the concept of Flow, defined by Nakamura et al. as a state requiring a balance between the perceived challenges of a task and the actor’s capabilities [

1]. In gaming contexts, this necessitates dynamic game mechanics adjustments to prevent players from drifting into boredom (low challenge) or anxiety (high challenge) [

3].

To operationalize this, early frameworks such as MDA (Mechanics, Dynamics, Aesthetics) posited that game mechanics—particularly resource economies like health and ammunition—serve as the primary levers for regulating frustration [

2]. Modern AI literature expands this view, emphasizing that effective adaptation requires a holistic player model that accounts for satisfaction, knowledge, and playing style rather than mechanical performance alone [

4].

2.2. Dynamic Difficulty Adjustment (DDA)

Dynamic Difficulty Adjustment (DDA) represents the first generation of adaptive systems, focusing primarily on performance metrics to regulate game pacing.

2.2.1. Performance-Based Adaptation

Traditional DDA systems rely on heuristic functions or statistical models to track player success rates. For instance, creating a reference point for "optimal" play allows systems to intervene when a player’s performance deviates significantly from the expected curve [

3]. However, simple reactive systems often fail to account for the temporal nature of skill acquisition — players learn and forget. To address this, tensor factorization techniques have been proposed to model player performance over time, allowing systems to forecast future failures and proactively tailor challenge sequences rather than merely reacting to immediate inputs [

5,

6].

2.2.2. Machine Learning in DDA

Recent systematic reviews indicate a paradigm shift from rule-based DDA to data-driven approaches [

7]. While earlier systems used simple "rubber-banding" mechanics, modern implementations utilize deep learning and reinforcement learning to create sophisticated opponent agents that adapt to human expertise in real-time [

8,

9]. Despite these advances, performance-based metrics remain a proxy for player experience; they measure

what the player does, but not necessarily

how they feel.

2.3. Affective Computing and Emotion-Based Adaptation

The field of Affective Computing, pioneered by Rosalind Picard, argues that for computers (and games) to interact naturally with humans, they must recognize, understand, and express emotions [

10]. This has led to the development of "Affective Game Computing," where the system closes the loop between the player’s emotional state and the game environment.

2.3.1. Physiological and Behavioral Sensing

To infer emotional states, researchers have integrated physiological sensors (e.g., EEG, Heart Rate Variability) into gameplay. For example, the BIRAFFE experiments demonstrated that bio-signals could effectively measure reaction intensity, which, when combined with game context (e.g., a "Game Over" event), allows the system to label specific emotions and adjust gameplay to mitigate negative states [

11]. However, the requirement for physiological sensors is often intrusive and impractical for ubiquitous mobile gaming [

8].

2.3.2. Non-Invasive Inference

To overcome hardware limitations, recent research has explored non-invasive methods. Dialogue-Based Self-Reports (DBSR) integrate emotional assessment directly into NPC conversations, allowing games to adjust difficulty parameters like enemy speed based on reported frustration without breaking immersion [

12]. More recently, deep learning has enabled robust emotion recognition from facial expressions alone. Studies in 2025 have shown that Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) can successfully detect psychological states such as sadness, fear, or happiness from live player footage [

13]. In the mobile domain, emotion-aware frameworks combining facial analysis with gaze tracking have been shown to significantly reduce negative emotional responses (e.g., anger) and improve learning outcomes in educational games [

14].

2.4. Gap in Research: From Maintenance to Induction

While substantial progress has been made in maintaining Flow or detecting emotions [

9], a gap remains in actively

inducing specific emotional states beyond simple satisfaction. Most existing systems act as "thermostats," attempting to return the player to a neutral state of engagement when they deviate [

7]. There is limited research on using deep learning not just to monitor, but to manipulate game parameters to provoke specific target emotions (e.g., inducing fear in a horror game or joy in a casual game) using standard mobile hardware.

2.5. Novelty of this Work

This research addresses the identified gaps through the following contributions:

Input-Driven Emotion Inference: We propose a deep learning framework that correlates facial expression data with raw player inputs. This enables non-intrusive emotion inference solely through gameplay behavior, even when the camera is unavailable, thereby mitigating the privacy and intrusion concerns associated with continuous monitoring [

12].

Active Emotional Induction: Unlike traditional DDA systems that aim solely for "comfort" or "Flow" [

1,

2,

3], our system modifies game parameters to actively

induce target emotions, expanding the scope of adaptation from maintenance to emotional orchestration.

3. Ethical Considerations

We acknowledge the significant ethical implications inherent in systems designed to monitor and influence human emotional states. The manipulation of user affect by algorithmic systems has been a subject of scrutiny, highlighted by controversies such as the "emotional contagion" study on social media platforms [

15] and the emergence of "dark patterns" in game design [

16]. In the commercial gaming sector, patents suggest the existence of matchmaking algorithms explicitly designed to manipulate player satisfaction to drive microtransactions [

17], incentivizing the optimization of revenue over player well-being.

The deep learning architecture proposed in this research possesses a "dual-use" nature. While designed to orchestrate compelling narrative journeys (e.g., inducing fear in a horror setting), the same mechanisms could theoretically be tuned to exploit emotional vulnerability—for example, by deliberately inducing frustration to sell in-game assistance items.

We acknowledge that the techniques proposed in this paper, which enable the induction of emotional states such as fear or joy, possess a "dual-use" nature. The same mechanisms could theoretically be tuned to exploit emotional vulnerability — for example, by deliberately inducing frustration to sell in-game assistance items ("boosters") or to exploit emotional vulnerability to maximize retention loops in mobile gacha games. However, we argue, that the responsible path is to research these mechanisms transparently. It is likely that large commercial entities already utilize similar affective loops as proprietary trade secrets.

4. Methodology

This section details the technical architecture and data collection methodology employed for the empirical study presented in this work. The core components include the custom mobile game platform, the server-side data processing infrastructure, neural network architectures, and the associated data models and analysis techniques.

4.1. Problem Formulation

We address the problem of player emotion recognition and subsequent game adaptation as a sequence-to-sequence (Seq2Seq) modeling task, leveraging neural networks for prediction and optimization. The core task is to predict the next temporal step of state, given an observed sequence of game states, associated parameters and previous emotions. This prediction problem is formally defined as follows:

Let:

g - the current game state,

p - the set of game parameters,

e - be a distribution representing the player’s emotional state at a given time,

- a loss function measuring deviation from the desired emotion,

- the sequence of observed states up to time step n,

- the predicted state at the next time step,

- parameters of the neural network model used for game state prediction,

- parameters of a separate neural network model used for computing optimal starting parameters,

Given the sequence

x of

n time steps, each composed of

, the task is to predict the next step

, formulated as:

This prediction enables the formulation of the game adaptation task as an optimization problem.

The goal is to adjust game parameters in order to minimize the difference between the predicted player emotion and a target emotional state

, based on the current game conditions. Formally, this can be written as

Additionally, due to the stochastic nature of gameplay within game design and variability in emotional responses, we introduce a second predictive task: estimating the optimal initial game parameters (set before game session starts) that are most likely to elicit the desired emotional state. This task is handled by a second neural model

G, defined as:

Together, Equations (

1), (

2) and (

3) formalize a unified framework for emotion-driven game adaptation through predictive and generative modeling.

4.2. System Architecture

We developed a sophisticated, custom browser-based game platform using the Unity engine [

18] framework. This approach was selected to provide ease of access and broad compatibility, allowing players to participate on mobile devices without requiring any installation or download. This significantly lowered the barrier to entry, facilitating data collection effort.

The platform was engineered to collect rich, temporally aligned data streams encompassing gameplay events, sensor readings, and player affective state information. The client-server communication relied on robust, cross-platform protocols: client devices transmitted all collected data in structured JSON packages over the HTTPS protocol using a REST API. The server-side backend was written in Python, designed to efficiently receive, validate, and store the high volume of incoming data records.

Each complete data record corresponds to a single game session and is organized into distinct categories:

Metadata: administrative details of the session, including a unique session identifier, the time of data submission, the platform (iOS, Android), the specific device type, the screen dimensions (width and height), and the availability and permission status for system resources such as the gyroscope, touch input, and webcam.

Player and Session State: information capturing the player’s experimental status, including the desired affective state (the target emotion or feeling prompted in the experiment), the complete history of starting and mid-game adjustable parameters, the request timestamps for these adjustments, the total game duration, the highest level achieved, and whether the player’s character died.

-

Sensor Streams: time-series data from onboard device sensors:

- −

Motion Data: gyroscope quaternion data (X, Y, Z, W components), accelerometer measurements (X, Y, Z axes), and computed device rotation angles (Alpha, Beta, Gamma).

- −

Gravity Vector: the device’s perceived gravity vector (X, Y, Z components).

- −

Interaction Inputs: Touch coordinates (X, Y) and analog joystick input vectors (X, Y).

-

Spatial and Gameplay Histories: trajectories and positions of key game elements over time:

- −

Player character position histories (X and Y coordinates).

- −

Center-of-mass positions for enemy entities (X and Y coordinates).

- −

Player Interactions and Choices: discrete events related to player input and decision-making:

- −

Timestamps of all player choices.

- −

The specific types or categories of choices made.

- −

The progression level or stage associated with each choice.

-

Game Parameter Settings: detailed log of the dynamic configuration values for all in-game entities, providing a complete picture of the experimental condition:

- −

Parameters related to the player, enemies, weapons, passive abilities, loot items, and entity spawners.

- −

Timestamps detailing when any of these parameters were dynamically adjusted or "re-rolled" during the session.

The server performs data integrity checks immediately upon receipt, prior to storage in a structured database. Asynchronous message queues manage computationally intensive tasks, including emotion extraction from facial images captured during “data collection game-mode” using the Residual Masking Network [

19].

4.3. Game Design

The game was developed as an experimental platform to support empirical research, strategically integrating the necessity for robust data collection with an accessible and engaging player experience. The core design focused on achieving ease of use, broad device compatibility, and a consistent user experience essential for conducting reliable, repeated experimental trials.

A key priority was simplicity in both gameplay mechanics and interface. The game was engineered to require minimal upfront instruction, allowing participants to commence play immediately. This approach significantly reduced the participant’s cognitive burden and time commitment, which helped expand the potential participant pool and improve the reliability of the collected behavioral data across diverse user groups.

The system was implemented as a browser-based, single-player application, ensuring access across various mobile devices without the need for installation. This choice effectively eliminated common technical barriers, guaranteeing that participants could utilize their preferred devices for the experiment.

Gameplay was structured around a popular "auto-shooter" format, often called "Bullet Heaven". Players control an avatar in a 2D space against continuous stream of enemies, organized into waves. The avatar remains centered, and all combat actions are automated based on the equipped weaponry. This mechanism facilitates smooth and intuitive interaction, particularly on touchscreen devices, while preserving engagement through difficulty progression.

The visual style utilized a retro aesthetic with simple, recognizable graphics and a distinct color palette. Coupled with audio elements, the presentation was designed to be appealing and immersive, encouraging sustained and natural player engagement (The game screen is shown in

Figure 1). Crucially, the game was deliberately free of audiovisual elements that might induce strong emotional responses, ensuring experimental neutrality.

The core game loop incorporated a systematic and time-dependent increase in difficulty, prompting players to develop adaptive strategies. Participants earned experience points (XP), which allowed them to select upgrades (e.g., enhanced weapons or passive abilities) from a predefined set, introducing controlled variation between sessions. The weapon system featured distinct attack patterns, while passive elements supported long-term engagement and behavioral diversity. Attack patterns, which included long-range single-target, short-range area-of-effect, medium-range crowd control, and random firing, directly invited players to engage with and explore the game. At each level, the player was prompted to select one of the following: a new weapon, a weapon upgrade, a new passive ability, or a passive upgrade. Several enemy types were present, distinguished by variations in their movement patterns (e.g., direct approach vs. random direction) and stat profiles (e.g., high hit points and damage but slow movement, or weak but very fast, and lone operation vs. group attacks). To create the feeling of being surrounded, enemies were spawned at random locations on the boundary of a circle centered on the player, consistently outside the player’s view. The randomization of avatar upgrade offerings and enemy attack vectors compelled participants to experiment with varied strategies.

This strategic necessity, by sustaining participant interest in the gameplay, served to naturally mitigate the potential rigidity of the controlled research environment. Designed for short, repeatable sessions, the structure minimized participant fatigue and scheduling issues, which is highly advantageous for data collection. Each session concluded consistently, either upon player defeat or the completion of a final objective, providing a clear and standardized structure for subsequent data analysis.

The entire game system is controlled by a set of parameters that govern crucial elements, including player statistics, weapon and passive item statistics, enemy statistics, and the enemy generation intervals and rate. Collectively, these parameters provide the mechanism nuanced control over the game’s flow, offering a means to systematically influence both players’ emotions and their in-game behavior.

4.4. Emotions Ground-Truth Proxy

Determining a player’s emotions directly from gameplay data is challenging. In-game actions, such as defeating an opponent or solving a puzzle, do not reliably reveal underlying affective states, and the same event may evoke different emotions in different players. This ambiguity makes it difficult to define a definitive ground truth based solely on gameplay metrics.

Self-reported emotions are also problematic. Players may struggle to identify or articulate their feelings in real time, and interrupting gameplay to collect reports can disrupt immersion and alter the emotional experience itself. Individual differences in emotional vocabulary and attribution further reduce consistency, making self-reports a weak source of ground-truth data.

To address these limitations, we employ a proxy ground-truth approach based on automatic facial expression analysis. The assumption is that spontaneous facial expressions, while imperfect and subject to cultural and situational variation, provide a more immediate and less biased indicator of emotional state than self-reporting. We use a pre-trained facial emotion recognition network [

19] to analyze photographs of players taken during gameplay. The network assigns one of seven labels (anger, disgust, fear, joy, sadness, surprise, or neutral) [

20] to each image, which we then link to the corresponding game state data.

While we acknowledge that facial expressions are behavioral signals that may not always perfectly align with internal physiological states, they represent a necessary trade-off between accuracy and ecological validity in mobile gaming [

21,

22]. Unlike physiological sensors (e.g., EEG, GSR), which are often intrusive and impractical for widespread deployment [

23], or self-reports, which disrupt the player’s immersion and flow [

12], facial analysis allows for continuous, non-invasive monitoring.

This reliance on facial analysis aligns with recent methodologies in adaptive game-based learning and Flow regulation, where webcam-based inference is accepted as a valid and sufficient proxy for real-time affective modeling [

13,

14]. It is also consistent with recent affective computing frameworks that prioritize the preservation of natural dynamics over the granular precision of invasive biosensors [

24]. This produces a proxy ground truth for player emotions, enabling us to annotate specific gameplay events with emotional information.

Crucially, within our architecture, this proxy provides the necessary supervision to bridge the gap between distinct data modalities. It enables the system to learn a complex mapping function where the emotional state is inferred directly from the observable history of player inputs and gameplay events. Consequently, our system utilizes a pre-trained facial emotion recognition network as a scalable proxy. Crucially, however, the proposed adaptation architecture is designed to be input-agnostic. While this study utilizes facial data for its accessibility, the underlying optimization loop remains compatible with any affective data stream (e.g., biometrics) should such hardware become ubiquitous in the future.

4.5. Neural Network Architectures

To perform effective optimization of game parameters, a reliable method for predicting their impact on player emotional responses is essential.

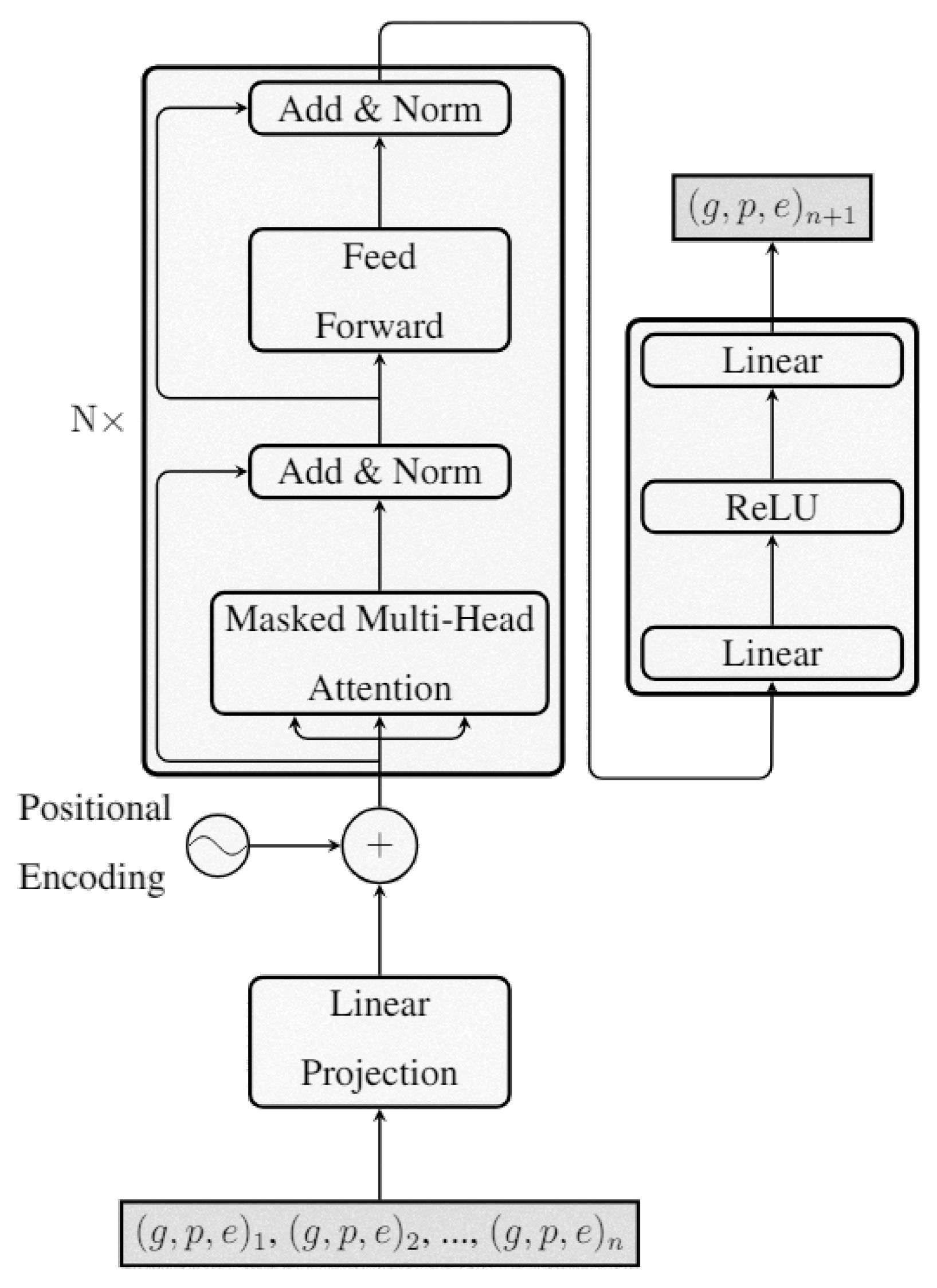

We introduce a Transformer network [

25] designed to predict future game states and the corresponding player emotional responses based on sequential gameplay history. In principle, this approach allows for the prediction of future game states based on historical data, coupled with the simultaneous prediction of players’ emotional responses. This model forms the core of our dynamic gameplay optimization loop, iteratively searching for adjustments to game parameters that are predicted to elicit the desired emotional state.

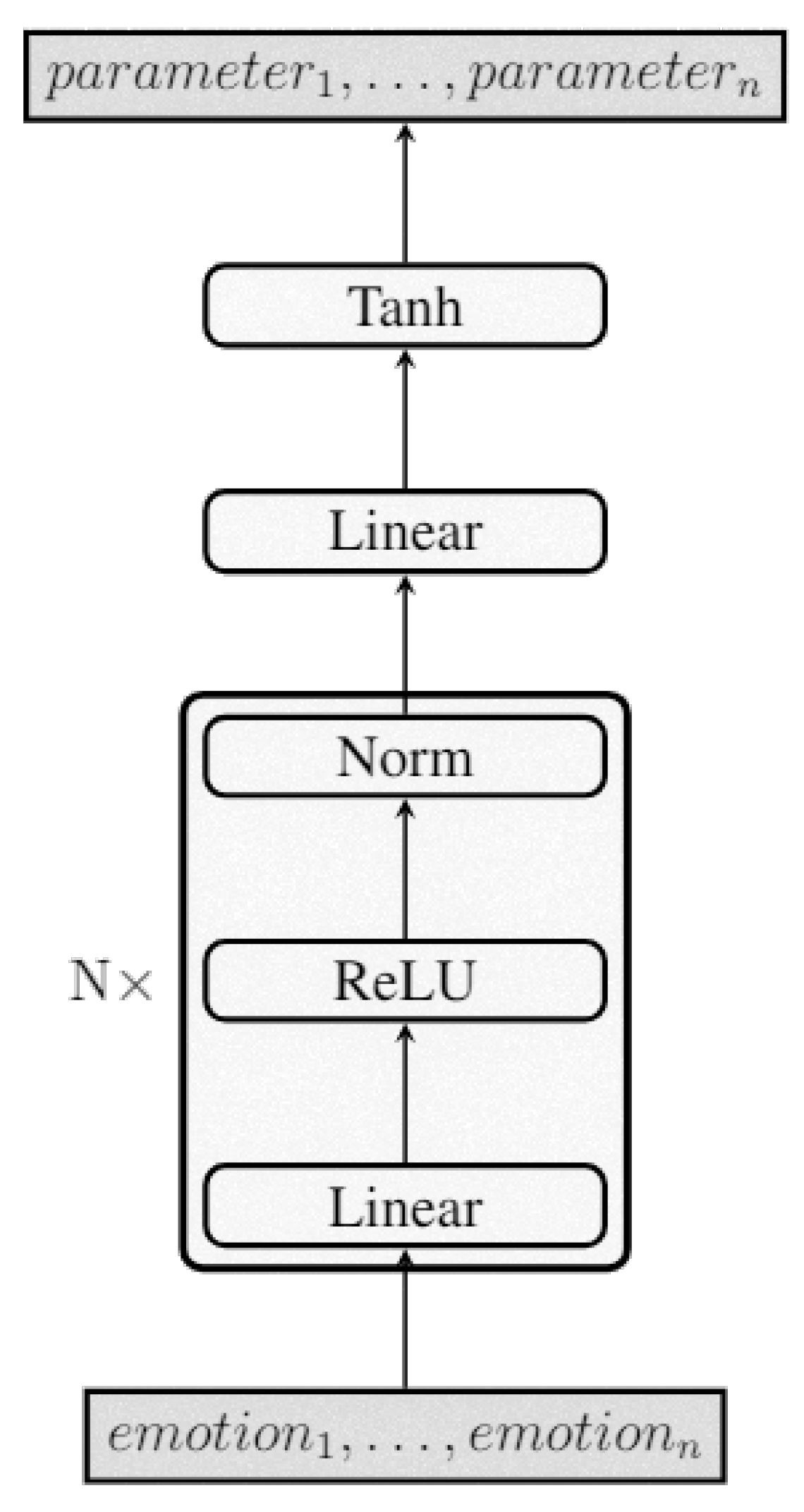

However, for optimization based on gameplay events, determining optimal game parameters requires self-reference to previous gameplay, which is unavailable from a cold start. To solve this cold-start problem and establish initial parameters that are more likely to be closer to the desired emotional state, we incorporate a second, linear neural network. This dedicated network is designed to efficiently determine optimal initial game parameters that correspond directly to a target emotional state.

This dual-network approach ensures low-latency initialization while providing a dynamic, data-driven system for continuous, fine-grained parameter adjustment throughout the player’s session.

4.5.1. Transformer Architecture

Our approach leverages the Transformer’s [

25] core capabilities: multi-head self-attention mechanisms for capturing complex dependencies in long sequences and sinusoidal positional encoding to maintain sequence order information . However, the standard Transformer embedding approach, designed for discrete tokens representing words or sub-word units, is insufficient for representing the continuous numerical state vectors common in game systems (often multi-dimensional).

Therefore, the initial embedding layer, which maps discrete tokens, was replaced by a linear projection layer. This layer directly transforms the sequence of high-level state representations (e.g., player health, position, inventory) into the continuous vector space expected by the subsequent Transformer decoder layers. Subsequently, the positional encoding is added to the resulting vector.

We adapted the overall model structure as decoder-only, similar to the GPT architecture [

26]. This involves processing the sequence of previous game states through the decoder layers, where the attention mechanism allows the model to focus on relevant parts of the sequence history (masked attention) while generating the prediction, with each sub-layer followed by a residual connection and post-layer normalization. The final output of the model is the sequence of predicted future game state vectors and emotion distributions, achieved by a linear projection from the model’s hidden states.

This modified Transformer architecture effectively utilizes the attention mechanism’s ability to analyze long sequences and detect multiple relationships, while the linear projection ensures the correct input format for game state prediction, bypassing the need for tokenization. The network diagram is presented in

Figure 2. This dual objective design is critical, as it provides the necessary predictive capabilities for the subsequent optimization loop, directly enabling the system to predict how parameter adjustments might steer both the game state and the player’s emotional trajectory toward a specified target.

4.5.2. Initial Parameters Network Architecture

A fully connected neural network [

27] is employed to predict initial game parameters based on target player’s emotional state. The network’s input is a vector representing a distribution of emotional probabilities. These inputs are processed through blocks containing linear layers, ReLU, and layer normalization. The output of the last block undergoes a linear layer and Tanh activation to map final parameters to the desired range of

. The network is trained to directly map emotion distributions to an appropriate set of gameplay parameters. This capability is crucial for addressing the "cold-start" problem inherent in optimization systems. By reliably selecting an informed initial configuration predicted to evoke the target emotion, the model reduces the initial phase of divergence and accelerates the overall convergence of the subsequent optimization loop.

An additional method is implemented to increase the diversity of initial parameter generation for a given target emotion value, during inference. The value corresponding to the selected emotion was assigned manually, while the remaining components of the distribution were sampled from a conditional Dirichlet distribution to ensure they sum to one. The architecture is illustrated in

Figure 3.

5. Results and Discussion

Our primary objective is to train and assess the deep neural network architectures detailed in

Section 4.5. These models are tasked with predicting game states and identifying optimal initial parameters. The predictive and control capabilities of these neural networks are directly dependent on the foundational game state data.

The performance of the models’ outputs will be validated against ground truth proxy values to confirm their efficacy. Furthermore, the overall system functionality, particularly the performance of the game control module, will be evaluated to ensure proper operation.

5.1. Data Analysis

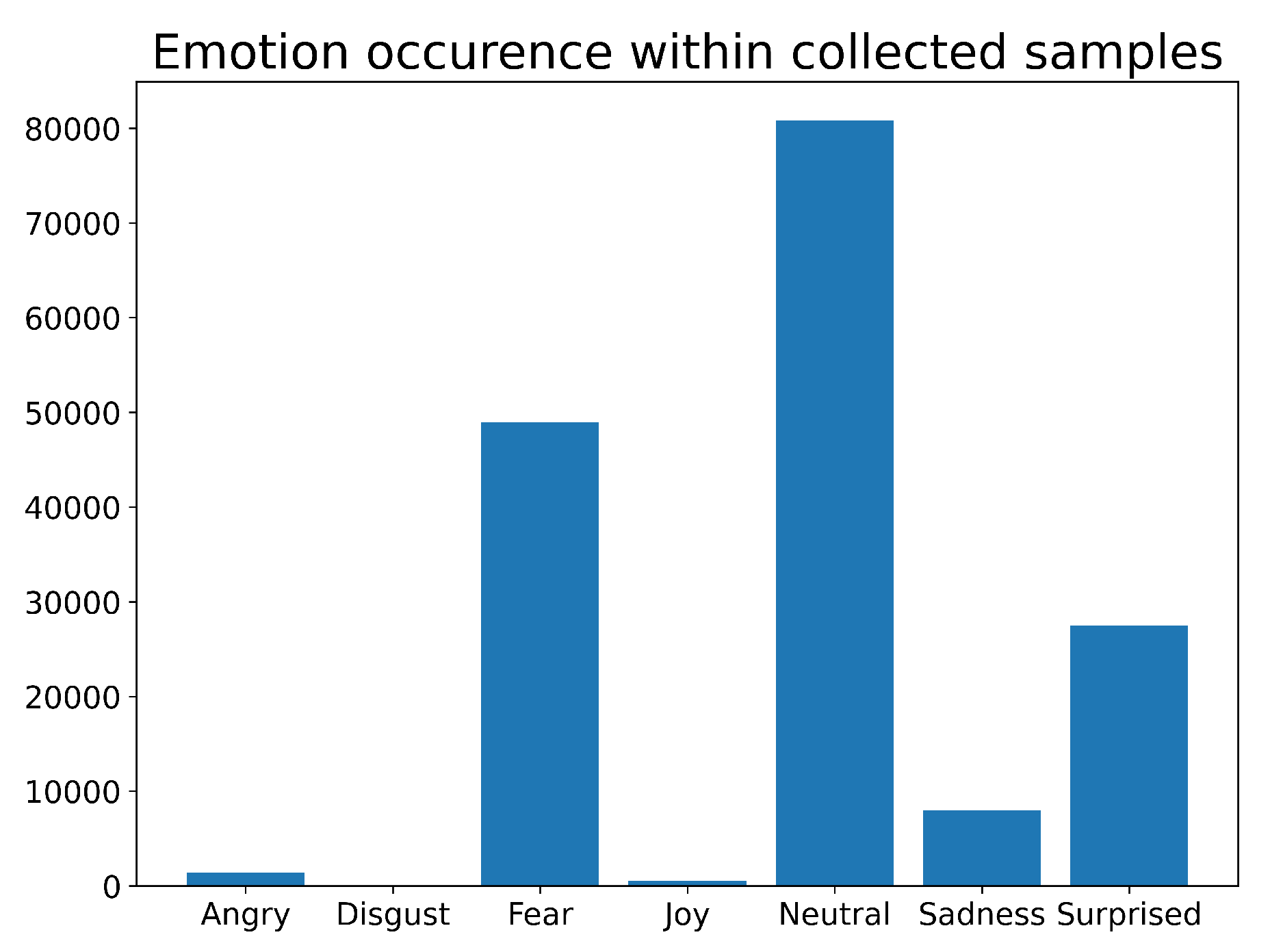

This study employs a dataset of 164,297 game state samples collected from 30 controlled volunteer sessions - 12 students from age group 20-26 and 2 supervisors (that were not the authors), ages 30-40. The dataset is partitioned into a training set (85%, 139,652 samples) and a testing set (15%, 24,645 samples) to facilitate the training and evaluation of deep neural networks.

The dataset includes emotion labels derived from facial photographs captured during data collection, described in

Section 4.2 and

Section 4.4. The initial data analysis revealed an imbalanced distribution of these emotional states, which is further detailed in

Figure 4.

This imbalance can be explained by several experimental factors. Participants engaged with the game casually, often outside laboratory conditions and in parallel with unrelated activities. Each participant played only a few sessions, which could limit the immersion overall immersion compared to playing long sessions at home. Crucially, this overarching sparsity aligns with similar studies on facial expressions in gaming [

21], which demonstrates that full-spectrum emotional displays are rare and highly dependent on game genre. As such, the resulting dataset distribution reflects the genuine nature of user engagement in a auto-shooter context, allowing for valid conclusions regarding the detection and steering of these specific, realizable states. Therefore, the observed imbalance is an inherent characteristic of the domain, driven by the game type and the nature of interaction rather than a systemic failure of the collection method.

Although a predominance of neutral facial expressions could be interpreted as a sign of indifference or dissatisfaction, multiple lines of evidence indicate that the opposite is true. Subjective feedback collected from participants was positive; all students and supervisors taking part in the study characterized the game as an "overall fun experience" during immediate debriefs and subsequent unrelated conversations. This self-reported enjoyment was corroborated by supervisor observations of students, which highlighted high levels of engagement, peer-to-peer conversation, and active commentary during gameplay. Furthermore, the prevalence of neutral expressions is consistent with research on gaming psychology. Kobayashi et al. [

28] demonstrated that neutral facial expressions are often a product of the content’s nature — specifically, fast-paced action that demands high attention and concentration. In such contexts, overt emotional displays may be suppressed by the cognitive load required to process game information.

We attribute the elevated levels of fear and surprise to the intrinsic mechanical difficulty and novelty of the gameplay, rather than to the experimental conditions. The detection of such emotions aligns with identifiable, acute gameplay stressors inherent to the genre. In the context of the ’Bullet Heaven’ mechanic, it likely captures moments of survival panic or performance anxiety; these instances correspond with high-intensity threat spikes, such as the sudden accumulation of high-hit-point adversaries or overwhelming enemy density.

Similarly, occasional instances labeled as anger are consistent with frustration and goal obstruction, occurring most frequently when enemy encirclement forces players to abandon high-value resource pickups or experience unavoidable damage.

The scarcity of the joy class (0.27% of samples) is consistent with the ’Bullet Heaven’ genre, where the gameplay loop is characterized by sustained tension interspersed with brief, high-intensity moments of reward or relief (e.g., leveling up or clearing a difficult wave). Unlike neutral (concentration) or fear (tension), which represent continuous states, joy in this context functions as a discrete micro-affective event. Consequently, while the sample count is low, these instances represent high-fidelity signals directly correlated with specific, high-reward game states.

The lack of the disgust label corroborates the intended non-offensive nature of the stimulus material. The game environment was deliberately engineered to be aesthetically neutral, strictly excluding visceral, grotesque, or aversive audiovisual stimuli that typically elicit such an affective response. Consequently, this emotion was deemed irrelevant to the core gameplay loop.

In addition to emotions, gameplay parameters, which affected difficulty levels, were randomly reassigned every 60 seconds by a dedicated module.

The system’s core gameplay parameters were defined by several key variable sets that govern the interaction between the player and the environment. These parameters fundamentally determine the level of challenge. The parameters operate as systemic scalar coefficients applied directly to the intrinsic, predefined values of the game’s constituent systems and objects.

- 1.

-

Adversary Threat

This set of parameters quantifies the immediate threat posed by approaching adversaries.

Health - The durability or total damage an enemy can sustain before defeat.

Damage - The magnitude of harm inflicted upon the player by the enemy.

Movement Speed - The velocity at which the enemy pursue the player.

Size - The physical dimensions of the adversary, affecting collision and visibility.

- 2.

-

Player Avatar Attributes

These parameters define the capabilities and combat effectiveness of the player’s avatar.

Health - The durability or total damage avatar can sustain before defeat.

Regeneration - The rate at which lost health is recovered.

Damage - The multiplier of all damage inflicted by player.

Movement Speed - The velocity at which the player can move and reposition.

Size - The physical dimensions of the player character, affecting hit-box and area interaction.

- 3.

-

Weaponry Attributes

Parameters in this set describe the weapons statistics

Damage - The raw offensive power of the avatar’s weapons.

Attack Intervals - The delay between successive weapon uses (rate of fire).

Size - The area or range covered by the weapon’s effect.

Projectile Speed - The velocity of launched projectiles.

Piercing - The capacity of a projectile or attack to strike multiple enemies.

- 4.

-

Reward system This parameter governs the rate of player progression.

- 5.

-

Enemy Instantiation Frequency

Number of New Enemies per Generation - The volume of new adversaries introduced during each spawning cycle.

Generation Interval - The temporal delay between consecutive enemy spawning cycles.

Scaling - The rate at which the adversaries’ core attributes are amplified over time to maintain a suitable challenge curve.

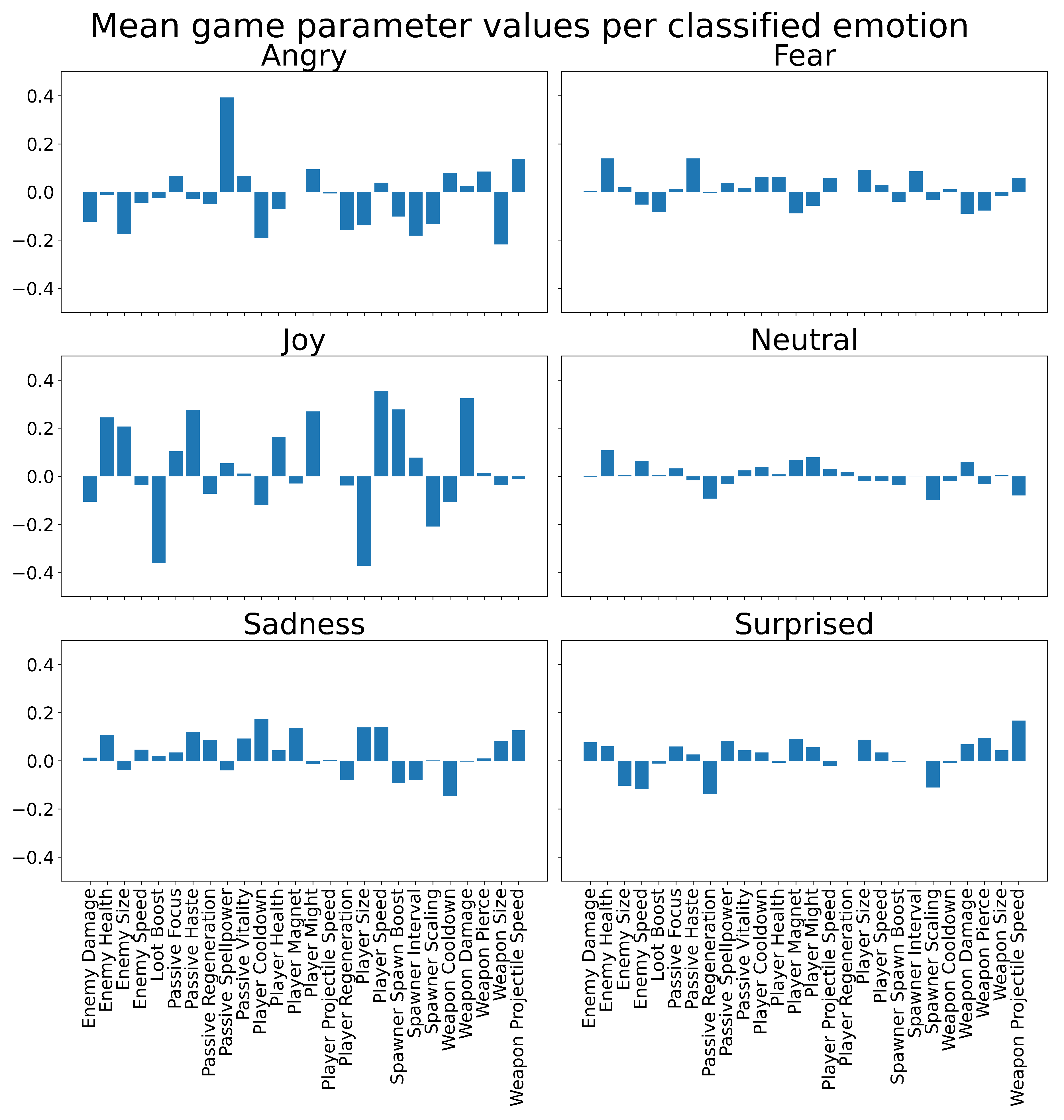

Figure 5 presents their average distributions for each emotional state. These parameters directly influenced both gameplay progression and emotional responses.

5.2. Training of Neural Networks

Both neural architectures were trained using CUDA on an NVIDIA RTX 3060 GPU. The main training parameters and configurations are summarized in

Table 1.

The results indicate that the transformer-based gameplay state prediction network required substantially longer training time due to its higher architectural complexity and dual-objective loss function. In contrast, the parameter initialization network, being fully connected and optimized with a single MSE objective, converged more rapidly while maintaining low error on the test set. These findings confirm that both models can be effectively trained on commodity hardware while achieving the performance required for subsequent adaptation experiments.

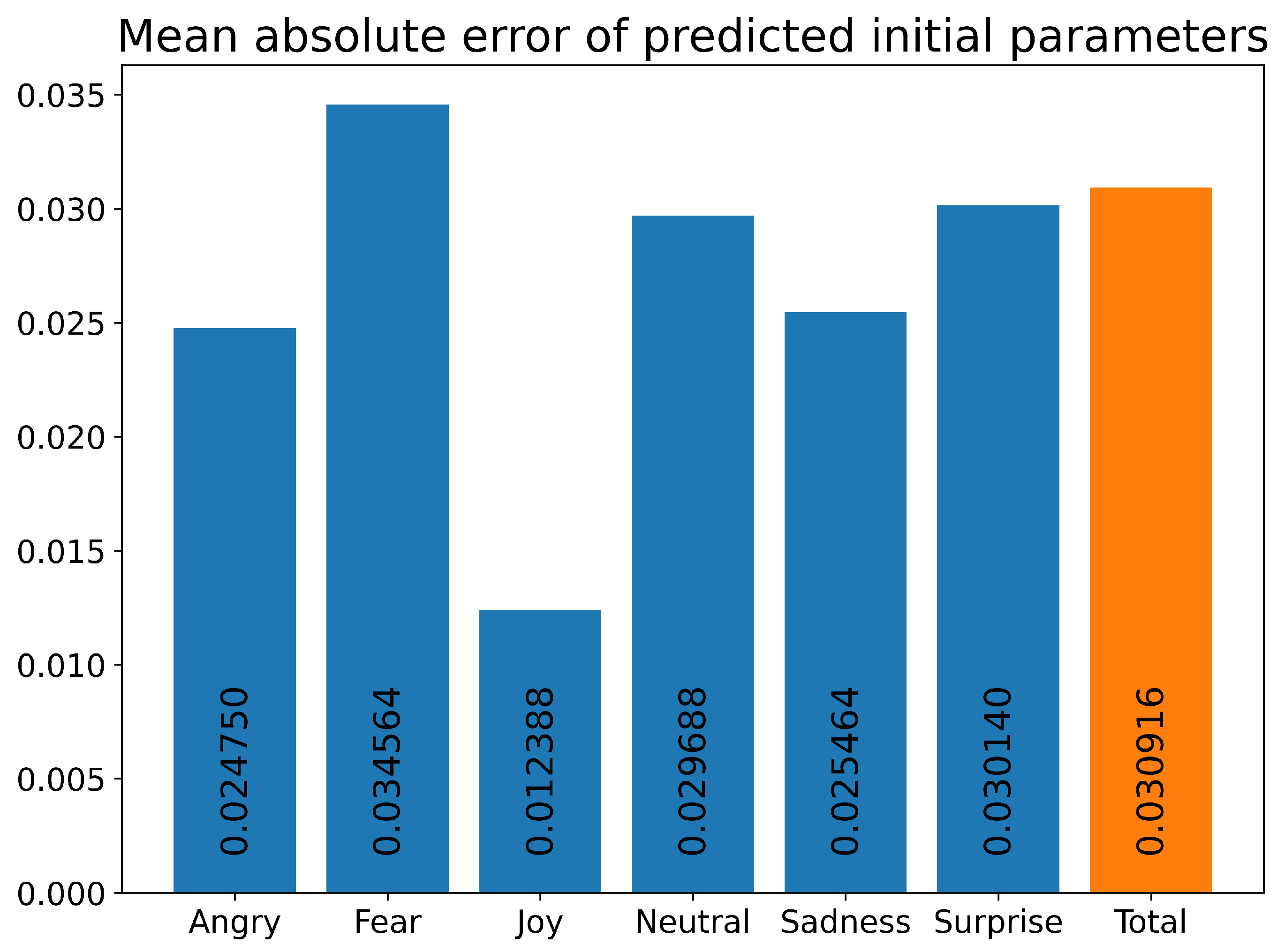

5.3. Emotion Prediction Performance

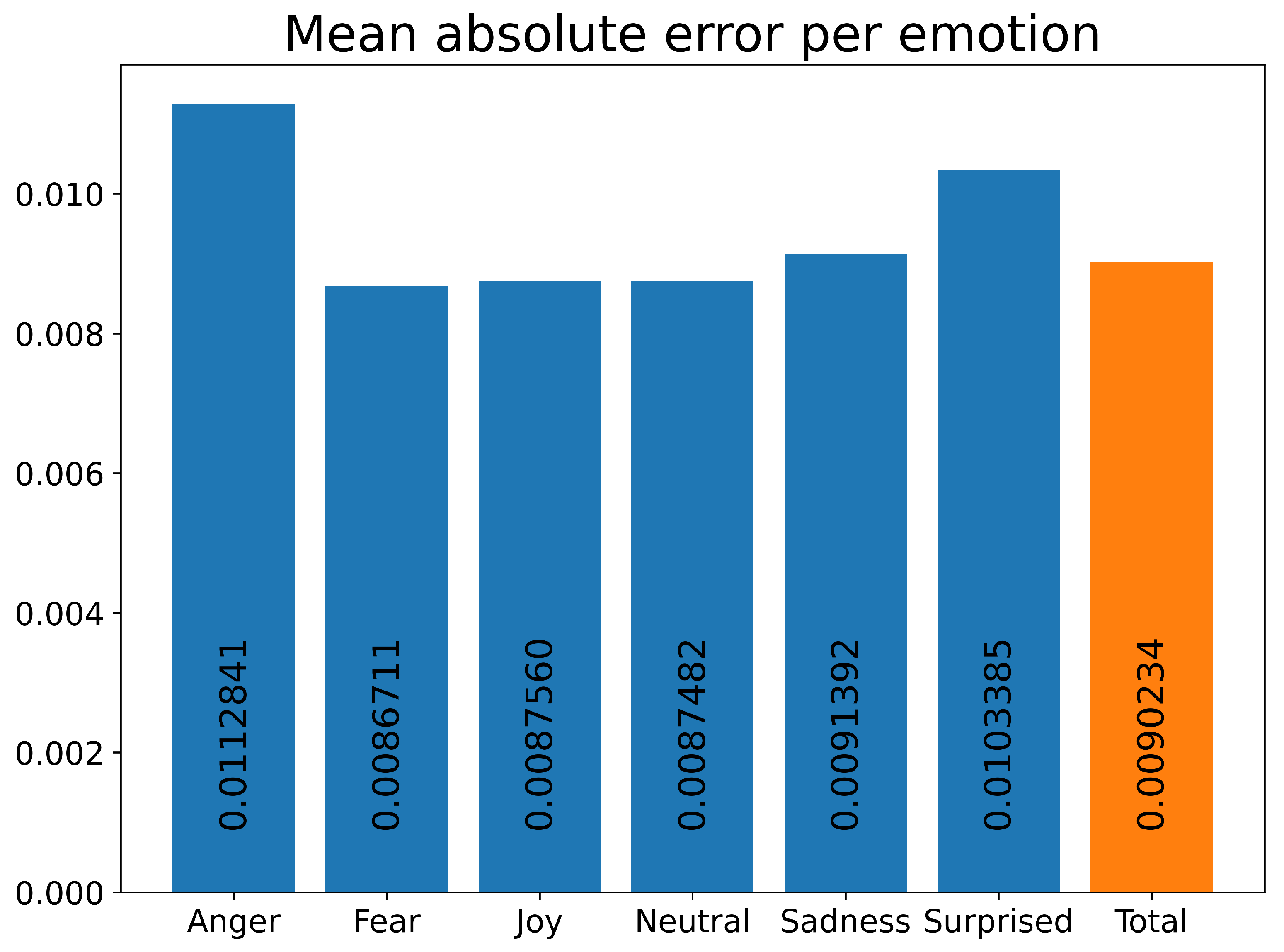

Across selected emotions, mean absolute error values remained low (

Figure 6), indicating accurate prediction of future gameplay states. Class-dependent variation was observed, but differences were minor and attributable to dataset imbalance rather than architectural limitations.

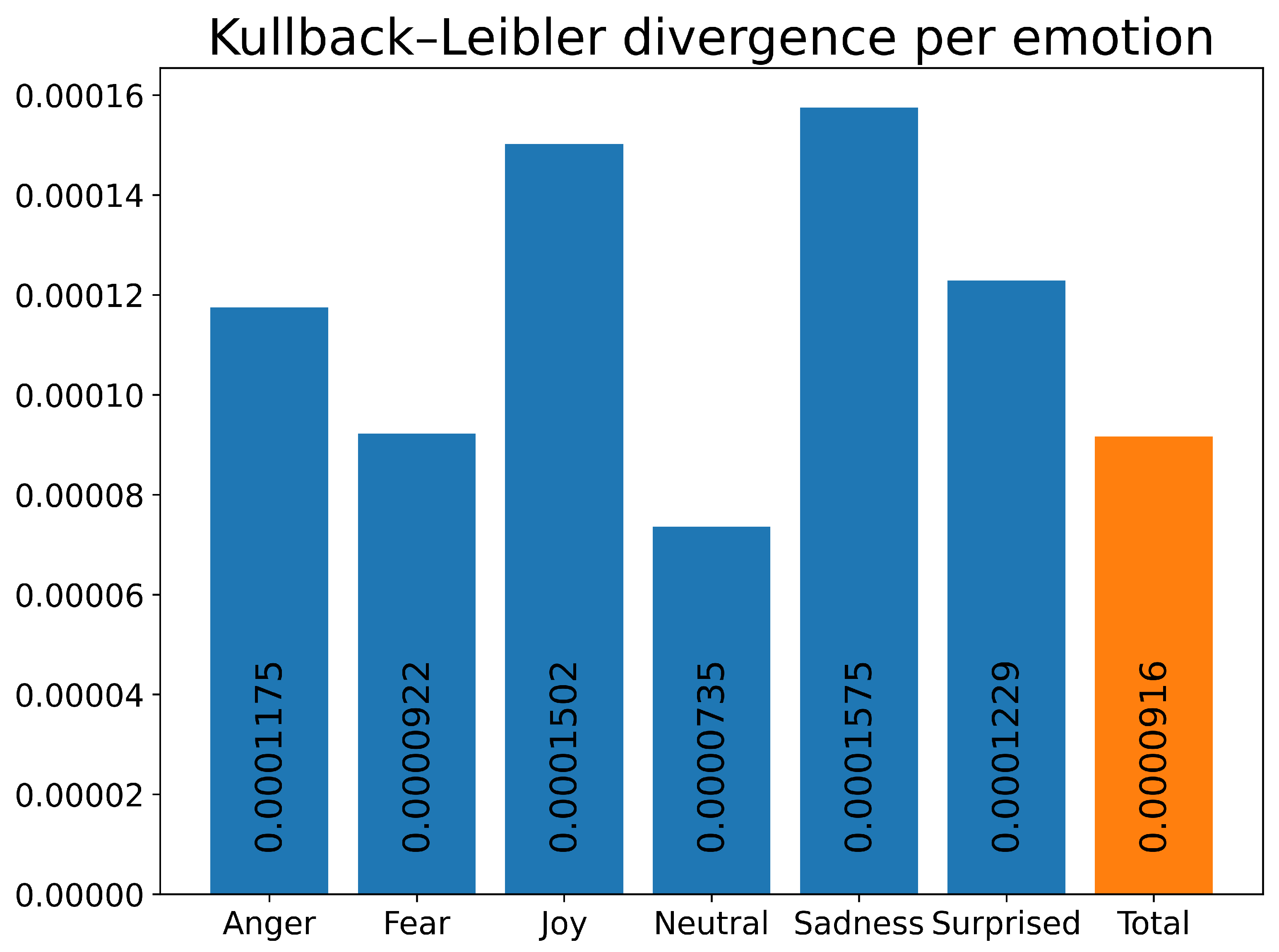

Similarly, Kullback-Leibler divergence values between predicted and observed emotional distributions were consistently low (

Figure 7), demonstrating that the model captured both dominant and mixed emotional states. This indicates its suitability for tasks requiring recognition of overlapping affective responses.

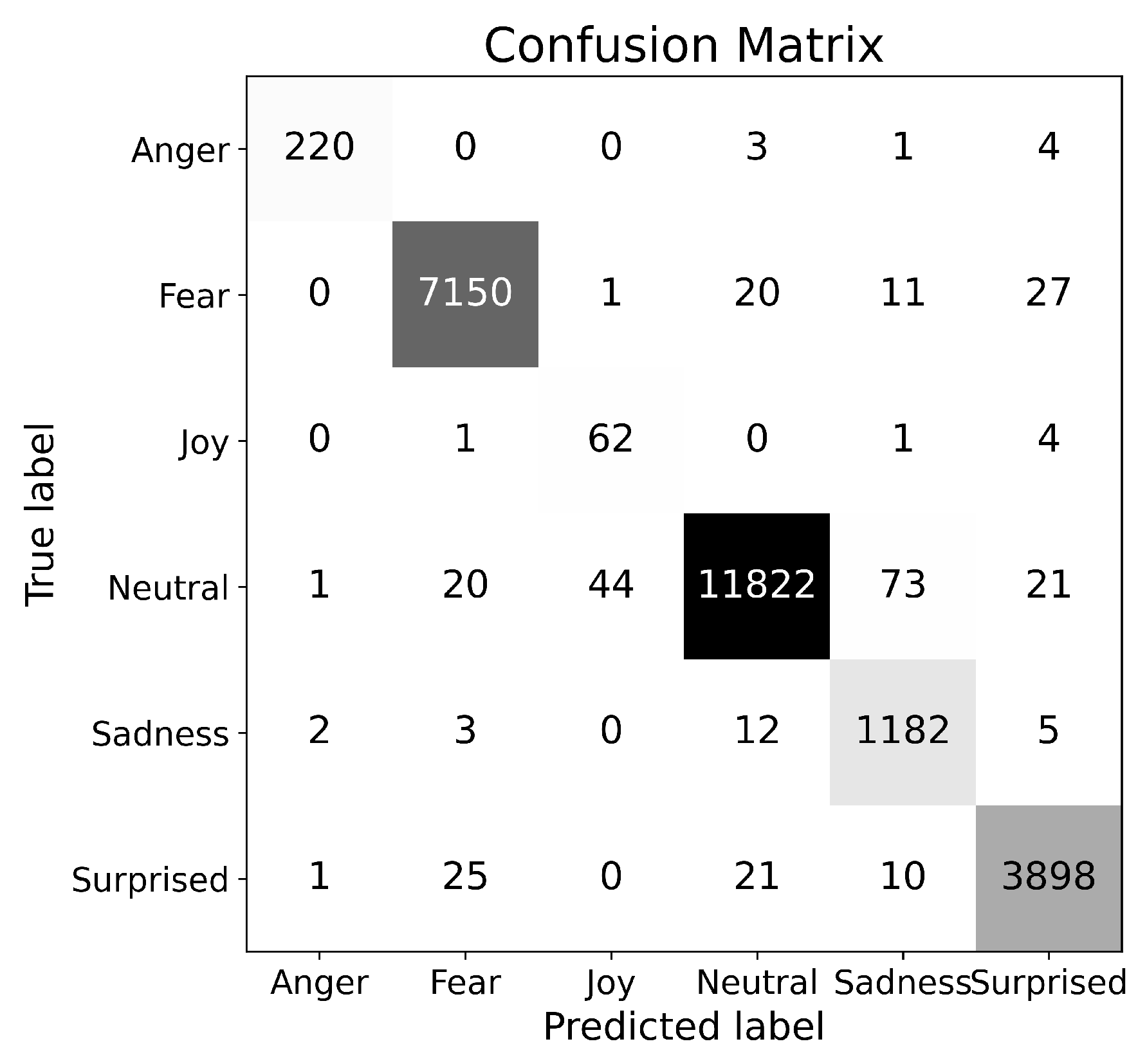

Classification accuracy is reported in

Table 2, with the corresponding confusion matrix shown in

Figure 8. The disgust category was omitted from the final model, as the game’s design deliberately excluded aversive stimuli, rendering the class statistically insignificant and contextually irrelevant. The model achieved balanced accuracy of 97.04%.

Results suggest strong performance on a majority of emotion classes. Nevertheless, the accuracy for underrepresented classes could not be conclusively validated due to an insufficient number of samples. This indicates that more balanced data is a critical requirement for a comprehensive evaluation and more robust findings in future studies. However, despite the significant class imbalance, the model achieved a relatively high F1-score (0.7086) for the joy class. We theorize, that this performance is due to the distinctiveness of the gameplay features associated with positive affect. This might suggest that the Transformer successfully mapped these sparse but distinct gameplay vectors to the corresponding affective labels, effectively learning to identify ’moments of triumph’ (like clearing all the tough enemies from the screen) without requiring the massive dataset volume needed for more ambiguous, continuous states like concentration.

5.4. Gameplay Adaptation

This section details the application and evaluation of the proposed emotional steering methodology, which consists of two main components: an initial parameter prediction network and an online optimization routine for adapting gameplay parameters. We first present the performance of the network designed to select appropriate initial game settings that target specific emotional states. Subsequently, we describe the offline optimization results, which confirm the model’s ability to converge toward desired emotional distributions using historical data. Finally, we detail the implementation and performance of the online optimization during live gameplay sessions, demonstrating the system’s effectiveness in periodically adjusting parameters to elicit targeted emotional responses throughout the game session.

5.4.1. Offline Optimization

The parameter initialization network achieved low mean absolute error (MAE) values across selected emotions (

Figure 9), measured on test data set, by generating parameters for given emotions distribution. This indicates that it can reliably select appropriate initial gameplay parameters to elicit targeted emotional distributions.

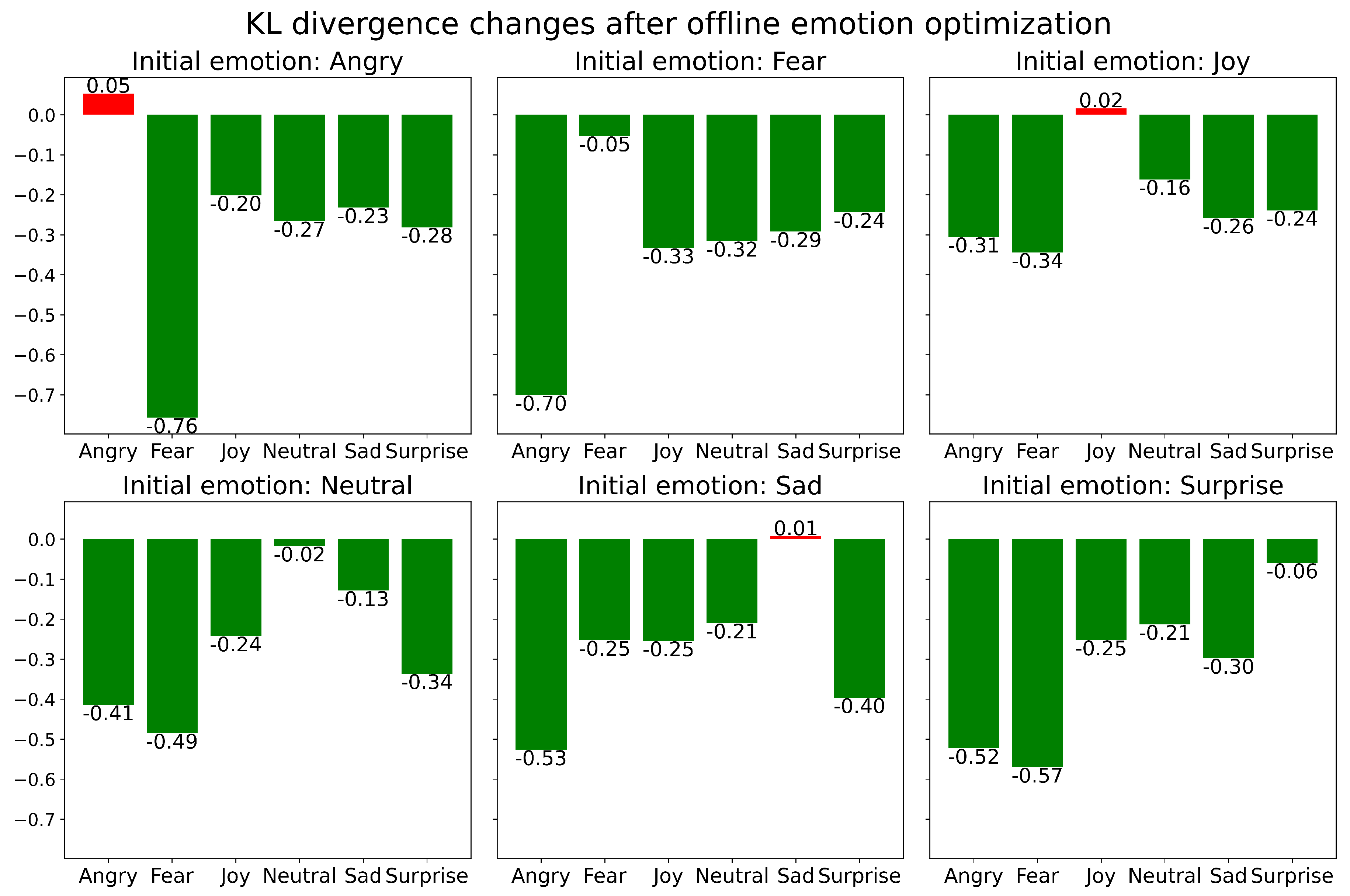

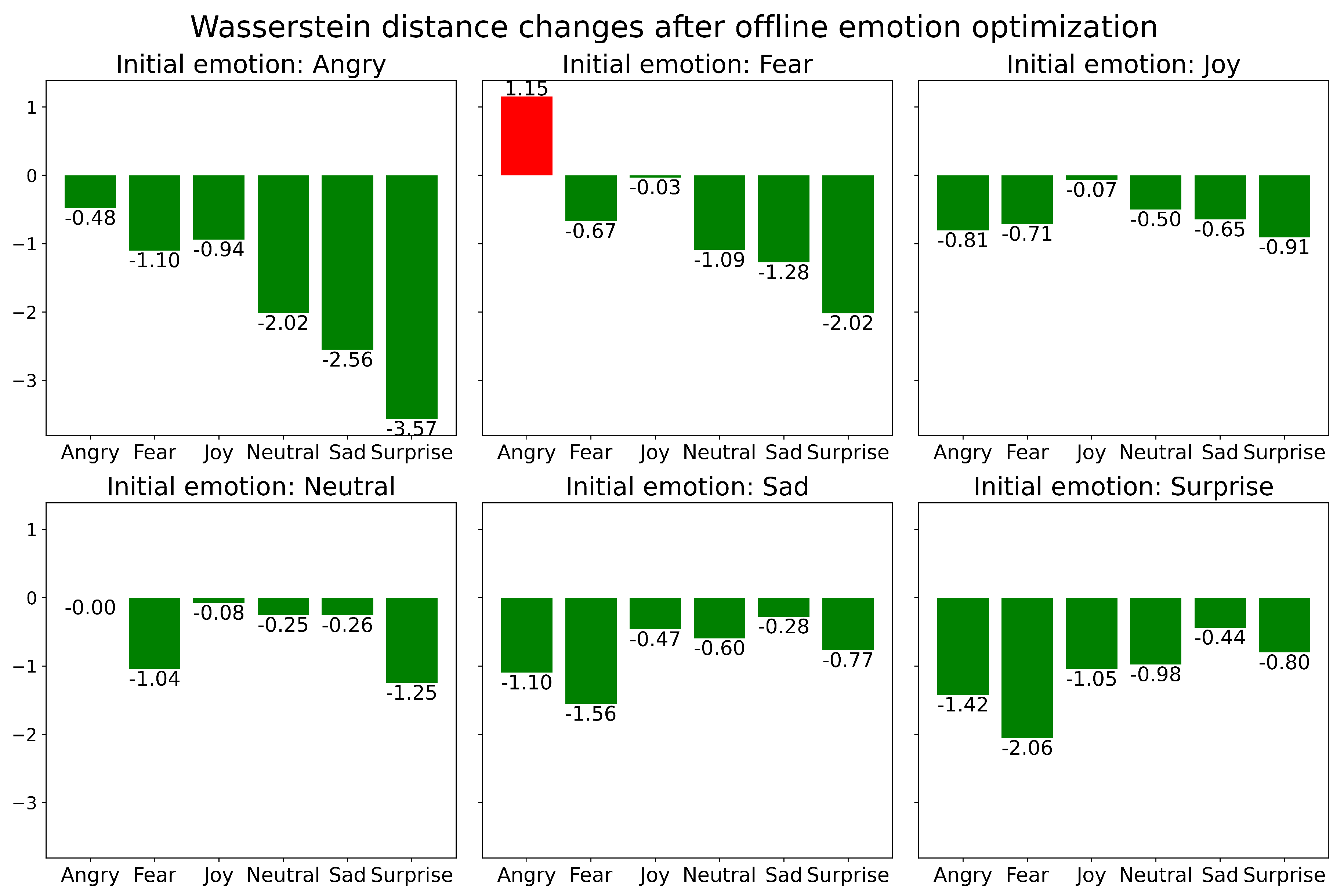

Optimization was performed based on recorded gameplay data to model steering of emotional states. The optimization routine involved the adjustment of half of the historical parameters. At each step, 30 future states were predicted by the transformer model, and the distribution of the final predicted emotions were compared against the target emotion using KL divergence. Results (

Figure 10) show decreasing divergence values, confirming convergence toward the desired distribution. Similar findings were obtained using Wasserstein distance (

Figure 11).

Due to hardware limitations, optimization was restricted to 500 Adam iterations per cycle, corresponding to an average runtime of 13 seconds. While this prevents continuous real-time adaptation, it enables periodic adjustments at a frequency aligned with natural player response times. The gameplay design inherently results in a temporal decoupling between parameter adjustments and their ultimate effects on player responses. This effect created a sufficient buffer that enabled the methodology to viably integrate the delayed parameter optimization processing time without disrupting the continuous flow of the session.

5.4.2. Online Optimization

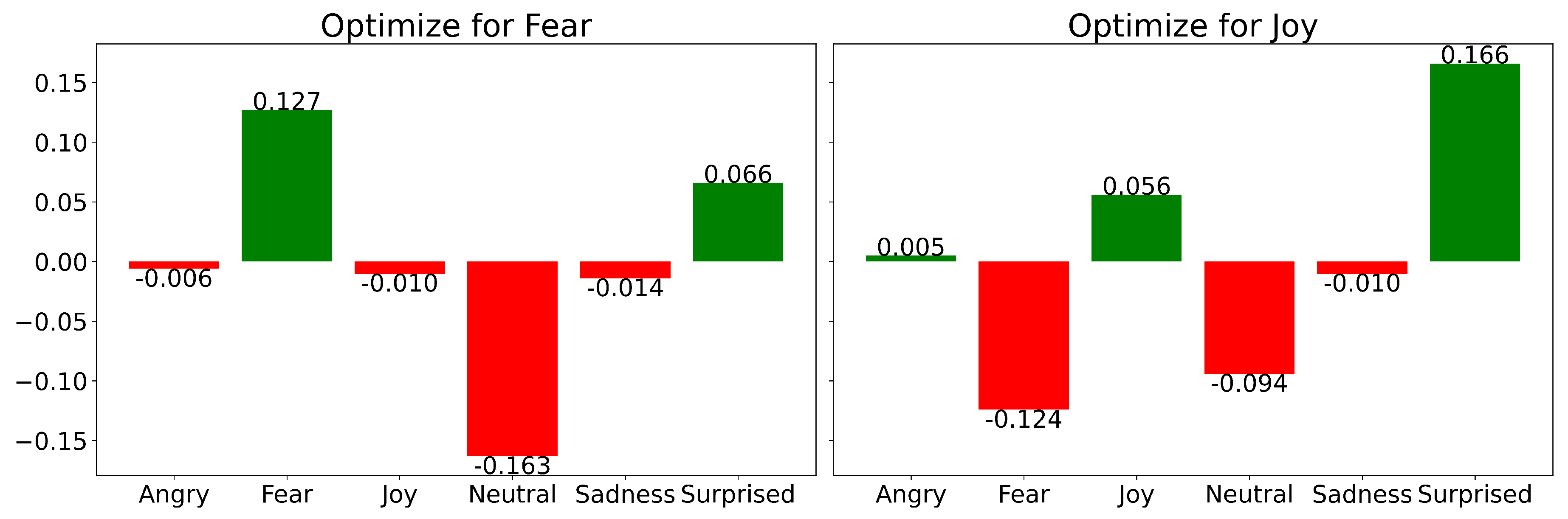

The optimization methodology was implemented and evaluated during live gameplay sessions. The process began by utilizing an initial parameter network to determine the starting game parameters predicted to evoke a selected target emotion, which persisted for session. During the subsequent one minute interval, data regarding the overall game state was continuously collected. Following this period, the game client transmitted a request to the computation server for parameter optimization. This optimization process leveraged the historical game state data to calculate a refined set of parameters, specifically to more effectively elicit the chosen emotion in the player.

Although the average computation time was sub-optimal at 13 seconds, this delay had no perceptible effect on the continuity of the gameplay, which proceeded uninterrupted. Upon receiving the newly optimized parameter set, the game flow was again measured for a subsequent 60 second period. This iterative loop of measuring, optimizing, and applying new parameters was repeated until the conclusion of the experimental session.

Live gameplay experiments targeting fear and joy produced increases in value of 55.01% and 99.89%, respectively, relative to test set average values of selected emotions (

Figure 12). In the case of joy it is important to contextualize this result. Given the baseline scarcity of this emotion in survival gameplay, this optimization does not imply a continuous state of euphoria, but rather a successful system-driven increase in the frequency of positive valence events. The system effectively manipulated parameters to generate more frequent ’triumph loops,’ which the model correctly predicted would elicit positive facial markers.

Furthermore, an increase in surprise was observed concurrently with the increase in target emotions. This co-occurrence merits further investigation regarding player awareness of gameplay changes. Notably, these results were achieved without artificial audiovisual manipulation, but solely through gameplay parameter adjustments, underscoring the effectiveness of the proposed method. These experiments consisted of using initial parameters prediction and adjustment of game parameters during live game sessions.

5.5. Discussion

The results confirm that the proposed system can accurately model both gameplay states and influence emotional responses, despite dataset imbalance and non-laboratory conditions. The ability to dynamically adjust parameters demonstrates the feasibility of emotion-driven adaptation. However, computational costs remain a limitation, as optimization requires several seconds per cycle. Additionally, dataset bias, particularly the predominance of neutral states and lack of joy states, may have affected classification results. Future work should address these limitations by collecting more balanced datasets and optimizing model efficiency for real-time deployment.

6. Conclusion

The primary objective of this work was to explore a framework for using deep neural networks to influence player emotions during mobile gaming. We successfully designed and implemented a mobile game and a system for data collection and processing. This system enabled the development of two neural network architectures aimed at analyzing and adapting game flow based on desired emotional states.

A key contribution of this research is the exploration of a methodology for an emotion-aware adaptive gaming system. Our findings indicate the potential for high emotion classification accuracy using only in-game state information and mobile sensor data. However, this study also highlights significant challenges inherent in this type of research. Primary among these are the limitations of the imbalanced training dataset and the computational latency, which currently preclude real-time, unobtrusive application. These hurdles underscore the difficulties of achieving a "feasible" system in a real-world context and provide critical insights for future work in this domain.

Future research should focus on optimizing the investigated Transformer architecture, refining our approach to ground-truth labeling, and addressing the computational efficiency required for a truly real-time adaptive system. Further study could also assess the generalization potential of this framework across diverse game genres and explore alternative methods for extracting game states, such as directly from images or sensor data alone.

In summary, this research provides a foundational framework for emotion-aware adaptive gaming. It not only demonstrates the potential of this approach but also, and perhaps more importantly, clarifies the key methodological and computational challenges that must be overcome to move from a proof-of-concept to a practical application.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.K., P.K.; methodology, J.K., P.K.; software, J.K; validation, J.K., P.K.; formal analysis, J.K., P.K.; investigation, J.K., P.K.; resources, J.K., P.K.; data curation, J.K.; writing—original draft preparation, J.K; writing—review and editing, J.K, P.K; visualization, J.K, P.K.; supervision, P.K; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Informed Consent Statement

Prior to participation, each volunteer received a detailed explanation of the study’s purpose, methodology, and data handling procedures. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, with explicit authorization for the real-time capture of facial imagery.

Participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time without consequence.

To ensure privacy and data security, facial images were strictly utilized for the immediate extraction of affect labels via the neural network. No raw image data was persisted to storage; images were processed in volatile memory and permanently discarded immediately post-inference. Consequently, the final dataset contains only anonymized gameplay telemetry and the corresponding derived emotion labels, ensuring no personally identifiable visual information was retained.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used large language models [

29,

30] for the purpose of assisting in the revision of grammar, phrasing, and overall clarity of the manuscript. The LLMs did not contribute to the research design, data analysis, interpretation of results, or the formulation of conclusions. All substantive content, including conceptualization, methodology, and scholarly interpretation, is the sole work of the authors. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Nakamura, J.; Csikszentmihalyi, M. The Concept of Flow. In Handbook of Positive Psychology; Oxford University Press, 2001; Available online: https://academic.oup.com/book/0/chapter/422198947/chapter-pdf/52442481/isbn-9780195135336-book-part-7.pdf. [CrossRef]

- Hunicke, R. The case for dynamic difficulty adjustment in games. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2005 ACM SIGCHI International Conference on Advances in Computer Entertainment Technology, New York, NY, USA, 2005; ACE ’05, pp. 429–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepulveda, G.K.; Besoain, F.; Barriga, N.A. Exploring Dynamic Difficulty Adjustment in Videogames. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE CHILEAN Conference on Electrical, Electronics Engineering, Information and Communication Technologies (CHILECON), 2019; IEEE; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yannakakis, G.; Togelius, J. Artificial Intelligence and Games; 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zook, A.; Riedl, M. A Temporal Data-Driven Player Model for Dynamic Difficulty Adjustment. Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Interactive Digital Entertainment 2012, 8, 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zook, A.; Riedl, M.O. Temporal Game Challenge Tailoring. IEEE Transactions on Computational Intelligence and AI in Games 2015, 7, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mortazavi, F.; Moradi, H.; Vahabie, A.H. Dynamic difficulty adjustment approaches in video games: a systematic literature review. Multimedia Tools and Applications 2024, 83, 83227–83274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, N.; Kulshreshth, A.K. Exploring Dynamic Difficulty Adjustment Methods for Video Games. Virtual Worlds 2024, 3, 230–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, N.; Kulshreshth, A.K. Dynamic Difficulty Adjustment in Games: Concepts, Techniques, and Applications. In From Pixels to Play - The Art and Science of Video Games; Guzsvinecz, T., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, 2025; p. chapter 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picard, R.W. Affective Computing; The MIT Press, 1997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kutt, K.; Ściga; Nalepa, G. Emotion-based dynamic difficulty adjustment in video games. In 2023 IEEE 10th International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics (DSAA); Thessaloniki, Greece, Manolopoulos, Y., Zhou, Z.H., Eds.; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), 9-12 October 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frommel, J.; Fischbach, F.; Rogers, K.; Weber, M. Emotion-based Dynamic Difficulty Adjustment Using Parameterized Difficulty and Self-Reports of Emotion. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2018 Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play, New York, NY, USA, 2018; CHI PLAY ’18, pp. 163–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younas, R.; Burhan ul Haq, H. Deep Learning Model to Analyze Psychological Effects on Gamers. Spectrum of Decision Making and Applications 2025, 2, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyal Awwad, A.M. Emotion-Aware and Context-Driven Mobile Game-Based Learning: A Machine Learning Approach. International Journal of Interactive Mobile Technologies (iJIM) 2025, 19, 4–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, A.D.I.; Guillory, J.E.; Hancock, J.T. Experimental evidence of massive-scale emotional contagion through social networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2014, 111, 8788–8790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zagal, J.P.; Björk, S.; Lewis, C. Dark patterns in the design of games. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Foundations of Digital Games, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Marr, M.D.; Kaplan, K.S.; Lewis, N.T. US9789406B2; System and method for driving microtransactions in multiplayer video games. oct 2017.

- Unity Technologies. Unity Real-Time Development Platform, Version 2023.3.14f1, 2024. Available online: https://unity.com/.

- Pham, L.; Vu, T.H.; Tran, T.A. Facial expression recognition using residual masking network. In Proceedings of the 2020 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), 2021; IEEE; pp. 4513–4519. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.J.; Erhan, D.; Carrier, P.L.; Courville, A.; Mirza, M.; Hamner, B.; Cukierski, W.; Tang, Y.; Thaler, D.; Lee, D.H.; et al. Challenges in Representation Learning: A Report on Three Machine Learning Contests. In Proceedings of the Neural Information Processing; Berlin, Heidelberg, Lee, M., Hirose, A., Hou, Z.G., Kil, R.M., Eds.; 2013; pp. 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, S.; Ahn, J.; Choi, H.; Jeon, J.; Kim, D.; Kim, H.; Kang, S. Analytical Framework for Facial Expression on Game Experience Test. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 104486–104497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Kim, D.K. Comparative Analysis of Emotion Classification Based on Facial Expression and Physiological Signals Using Deep Learning. Applied Sciences 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsia, I.; Zafeiriou, S.; Fotopoulos, S. Affective Gaming: A Comprehensive Survey. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, 2013; pp. 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levordashka, A.; Richardson, M.; Hirst, R.J.; Gilchrist, I.D.; Fraser, D.S. Trace: A research media player measuring real-time audience engagement. Behavior Research Methods 2025, 57, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 2017; Curran Associates, Inc.; Vol. 30. [Google Scholar]

- Radford, A.; Narasimhan, K.; Salimans, T.; Sutskever, I. Improving Language Understanding by Generative Pre-Training. Technical report, OpenAI, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow, I.; Bengio, Y.; Courville, A. Deep Learning; MIT Press, 2016; Available online: http://www.deeplearningbook.org.

- Kobayashi, N.; Jitoku, D.; Nishihara, M.; Fujimoto, Y.; Qian, C.; Okuzumi, S.; Tei, S.; Tamura, T.; Takahashi, H.; Ueno, T.; et al. Facial Emotional Expression in Reaction to Internet Gaming Videos Among Young Adults: A Preliminary and Exploratory Study. Neuropsychopharmacology Reports 2025, 45, e70031, [https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/npr2.70031]. e70031 NPPR-2025-0013.R2, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/npr2.70031.. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OpenAI. ChatGPT. Large language model. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Google. Gemini. Large language model. 2025. [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).