1. Background

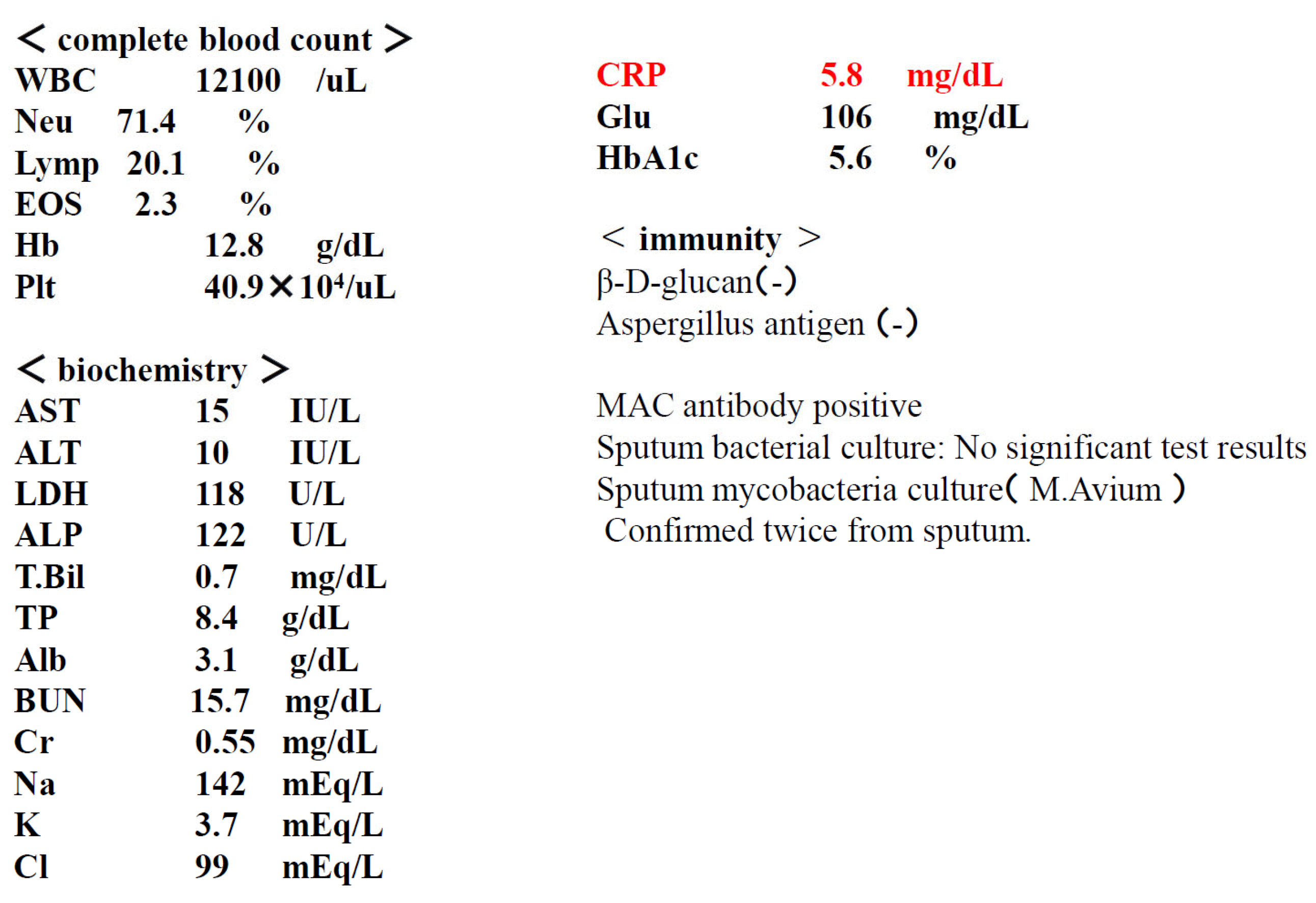

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) is a collective term for mycobacteria other than the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and Mycobacterium leprae. NTM includes over 150 species, and they are widely distributed not only in natural environments such as water and soil, but also in residential environments such as bathrooms. Inhalation exposure from these environments can lead to pulmonary NTM disease, a respiratory infection. In Japan, 90% of cases of pulmonary NTM disease are caused by two species: Mycobacterium avium and M. intracellulare. (1) Because the two species share similar biochemical profiles, they are collectively referred to as Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC). Pulmonary MAC disease is broadly divided into two types: the fibrocavitary type and the nodular-bronchiectatic type,(2.3) each with its own distinctive features. (4.5) (

Figure 1)

The course and prognosis of pulmonary MAC disease vary depending on the type. The fibrocavitary type generally progresses rapidly, and chemotherapy is recommended early after diagnosis. Because the nodular/bronchiectatic type progresses slowly and varies widely from case to case, there is no clear basis for determining when to start chemotherapy after diagnosis, and it is generally left to the discretion of the clinician.

Diagnostic methods consist of clinical and bacteriological criteria, and a diagnosis is made when both are met. Clinical criteria include the ability to exclude other diseases based on chest imaging findings. Bacteriological criteria include positive cultures of at least two different sputum samples. It is clearly stated that positive cultures cannot be substituted for positive nucleic acid amplification tests, and that gastric juice samples have little diagnostic value.

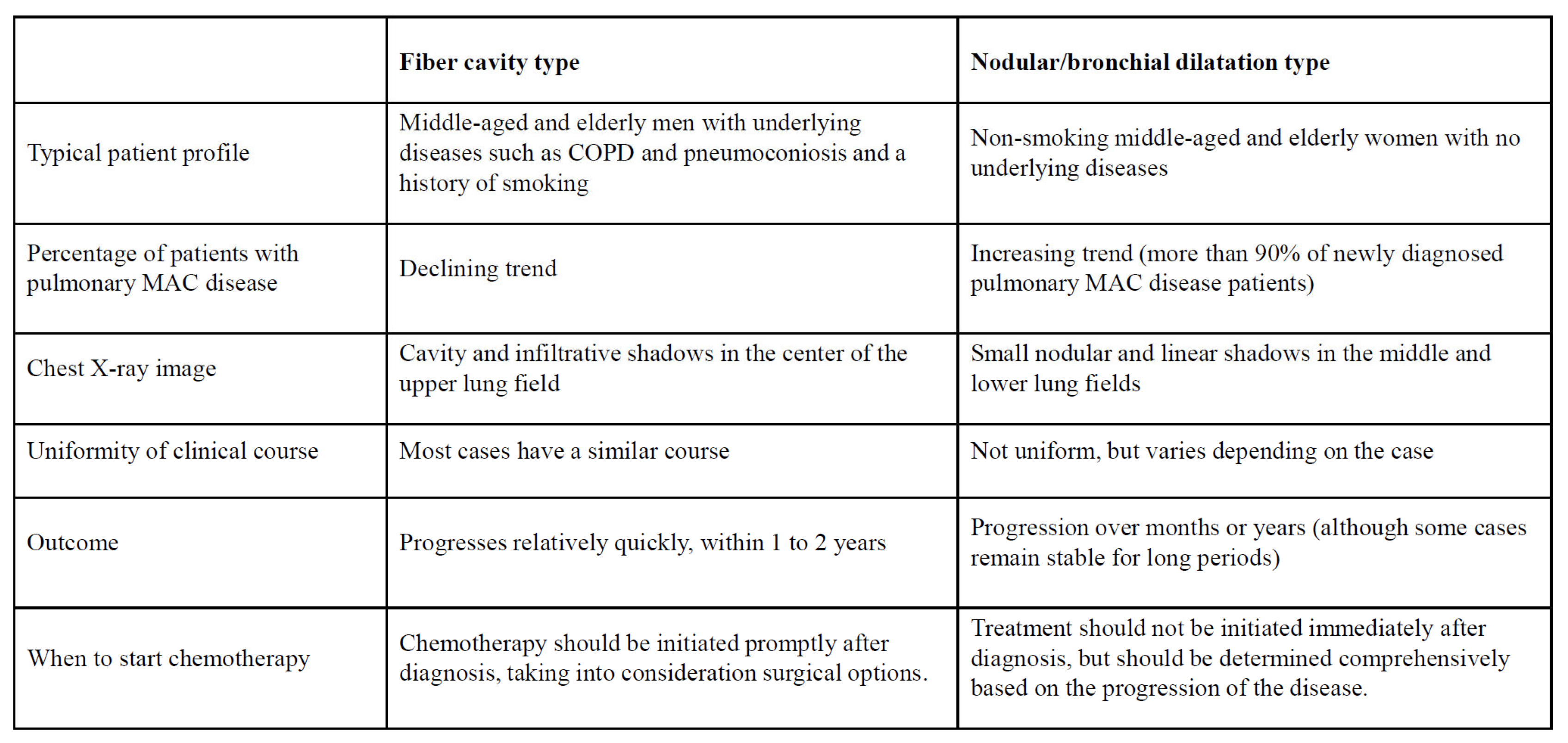

In Japan, where chemotherapy is primarily based on the three drugs clarithromycin (CAM), ethambutol (EB), and rifampicin (RFP), it is recommended to administer these three drugs orally daily, with the addition of intramuscular streptomycin or kanamycin as needed. (6.7,8) Treatment methods are shown in

Figure 2.

Regarding the duration of drug administration, although "approximately one year after bacterial culture negativity" is one guideline, there is little evidence and this is considered a topic for future research. Amikacin was originally available as an intravenous formulation and was approved for use in fibrocavitary and refractory nodular/bronchial types of pulmonary edema. However, its therapeutic efficacy remains uncertain, with standard drug therapy achieving long-term bacterial negativity in approximately 60% of cases (9). A meta-analysis reported a rate as low as 40% (10). The new drug, liposomal amikacin (ALIS), is an aminoglycoside antibiotic that works by binding to bacterial liposomes and inhibiting protein synthesis. Its greatest features are its liposomal amikacin technology and a dedicated inhaler. This allows amikacin to efficiently reach alveolar macrophages, directly acting on and killing MAC bacteria within them. This provides therapeutic benefits while minimizing systemic side effects. This is a novel treatment approach. (11,12,13)

Inhaled amikacin (ALIS) is indicated for fibrocavitary and refractory cases. However, due to its recent release, high cost, and difficult inhalation method, there is still little data on its therapeutic efficacy in clinical practice. Here, we report two cases: one in a cancer patient with a weakened immune system who developed severe pulmonary MAC disease, and the other in a patient with pulmonary MAC disease that had been gradually progressing for several years. Both cases were elderly women, and ALIS was used to treat these cases with efficacy at a lower dose than the standard treatment dose.

2. Case Presentation and Outcome

2.1. Case 1: 73-Year-Old Female

Chief complaint: Dyspnea, cough

Medical history: Stage I breast cancer

Lifestyle history: Smoking history: None, Alcohol consumption: 1 beer/day

Present illness: The patient had been diagnosed with left pleural effusion and pulmonary MAC disease and was receiving treatment at a local hospital. She was referred to our hospital due to worsening dyspnea and chronic cough. Right breast cancer was incidentally discovered during the examination, and she was referred to a breast cancer specialty hospital. Due to the early stage of the disease, a right mastectomy was performed. Given her advanced age and impaired reading ability due to frailty, postoperative chemotherapy was not administered. Regarding pulmonary MAC disease, chest CT scan revealed diffuse granular opacities in both lung fields, a cavity in the left upper lobe, and pleural effusion in the left pleural cavity. (Figure) Sputum acid-fast bacillus cultures detected M. intracellulare twice. Furthermore, blood tests were positive for MAC antibodies, and a diagnosis of pulmonary MAC disease was made. Thoracentesis and pleural fluid cytology revealed no cancer, and bacterial cultures did not detect any bacteria. A diagnosis of pulmonary MAC disease with pleurisy was made. CAM 800 mg/day, RFP 300 mg/day, and EB 250 mg/day were initiated as outpatients, but symptoms did not improve, so the patient was admitted to the hospital for the introduction of ALIS.

Symptoms at the time of admission: height 145 cm, weight 35 kg, temperature 36.5°C, blood pressure 124/78 mmHg, pulse rate 98/min, irregular pulse.

No palpable lymph nodes, cardiac rhythm irregularities, lung sounds with coarse and intermittent rales, respiratory rate 21/min, abdomen flat, soft, and nontender. Right mastectomy was performed, and no limb abnormalities were observed.

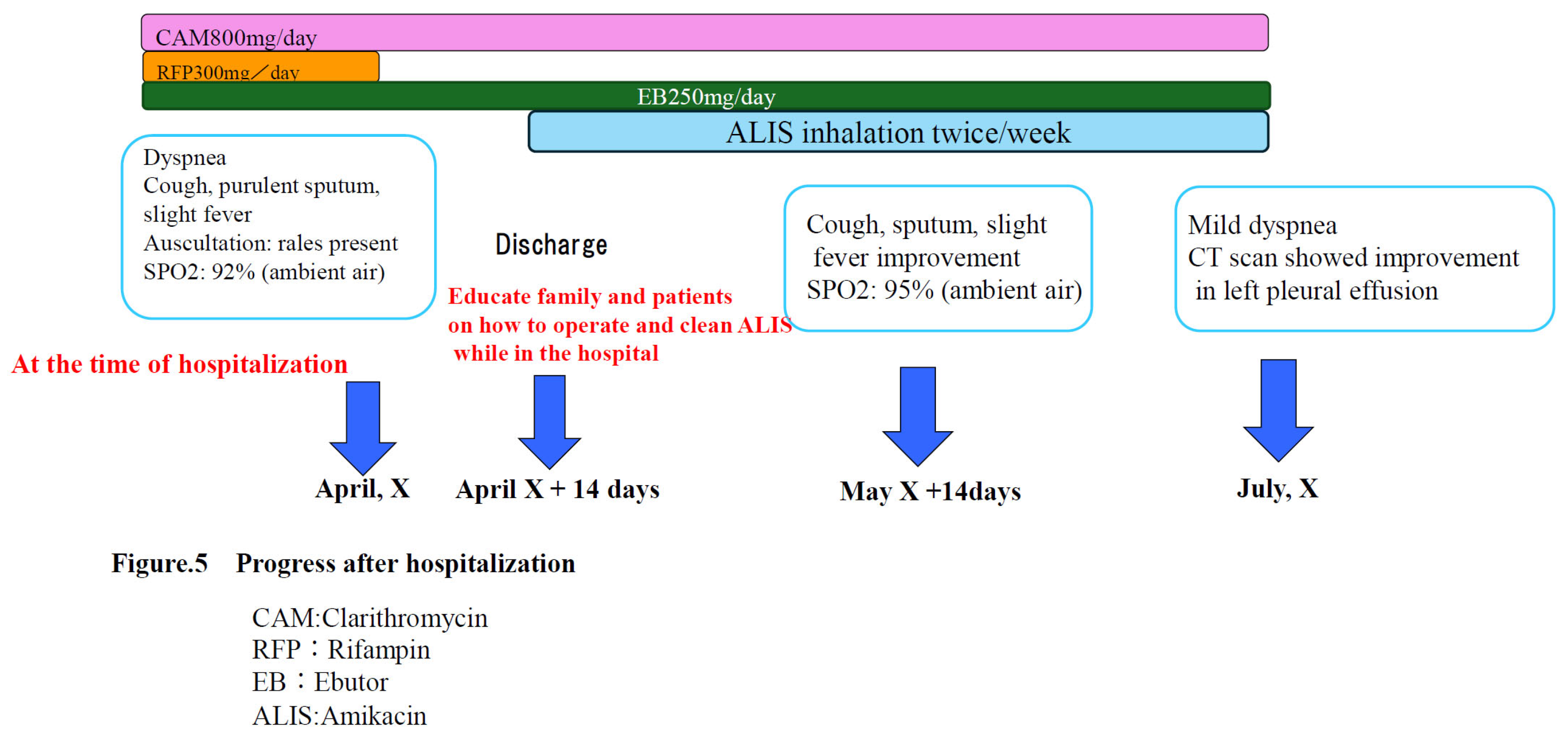

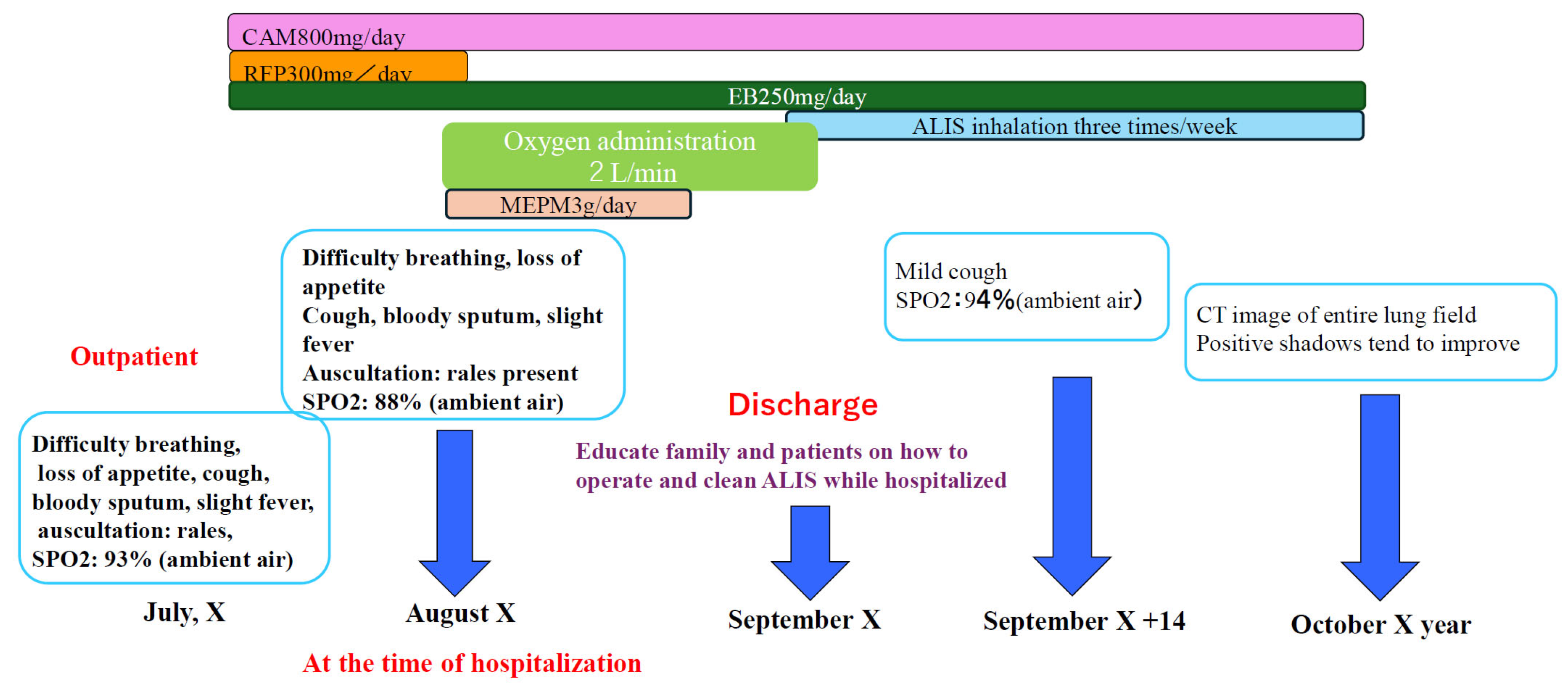

Post-discharge course: RFP was discontinued due to the onset of liver dysfunction and anorexia upon admission. CAM and EB therapy were continued, and fluid replacement therapy was administered while awaiting improvement in the patient's anorexia and liver damage. Approximately 14 days were then spent instructing the patient's family on how to operate and clean the inhaler before starting ALIS. After the patient's anorexia and liver damage improved and he was able to inhale properly, he was discharged and began treatment with ALIS administered once daily, twice weekly. The change from daily administration to twice weekly administration was due to the patient's poor general condition, which made it difficult for him to consistently administer the inhaler himself. Therefore, administration was initiated on days when his family was available to assist him. (

Figure 5)

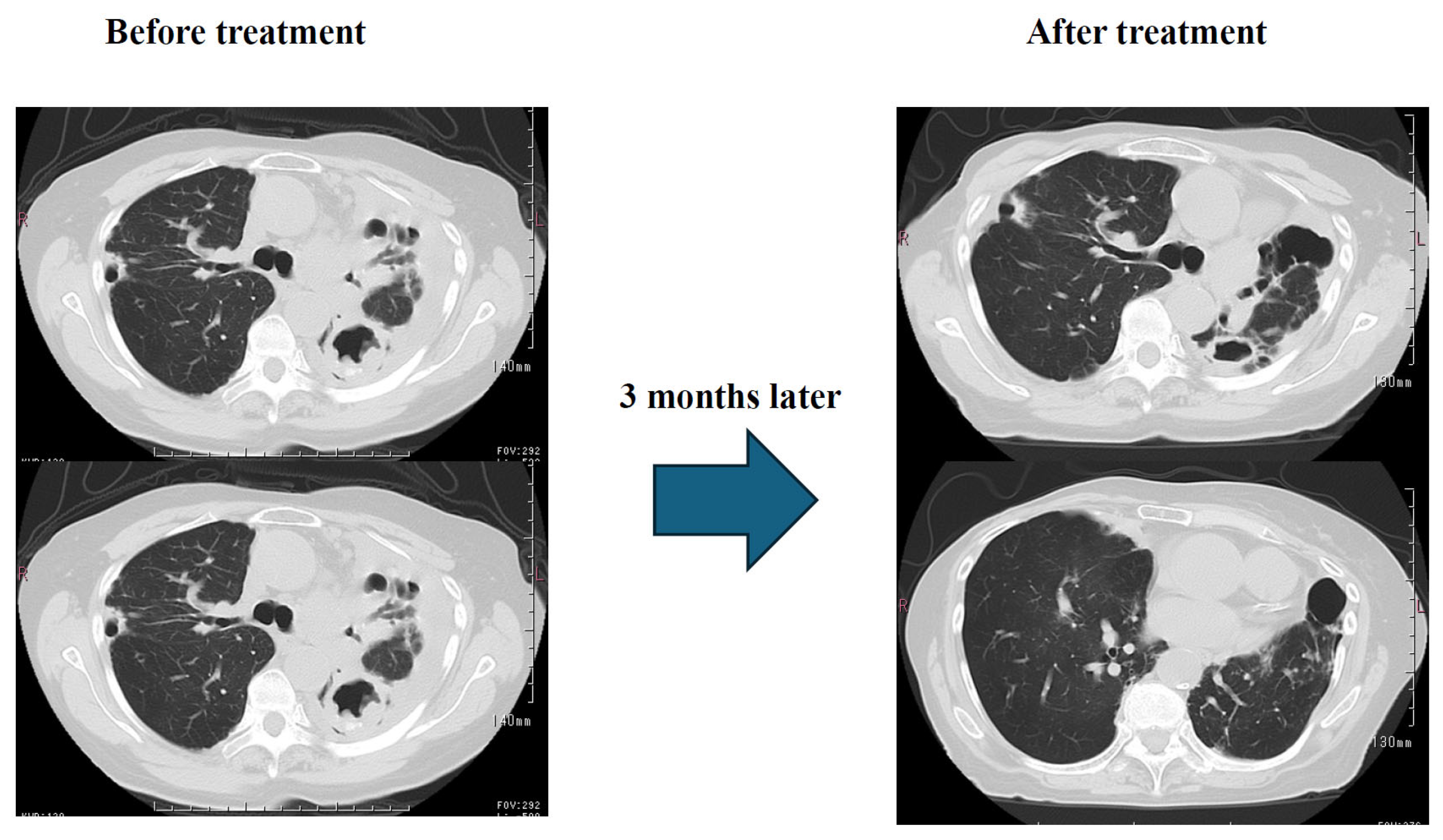

Results: Three months later, sputum testing detected M. intracellulare, but chest CT scans showed significant improvement in pleural effusion and infiltrates. (

Figure 6) Subjective symptoms included almost complete resolution of coughing, and significant improvement in dyspnea. SpO2 (outside air), which was 92% at the start of treatment, improved to approximately 97%. Currently, the patient is receiving CAM, EB, and ALIS once a day, twice a week, in one inhalation, and his condition is stable.

2.2. Case 2: 87-Year-Old Female

Chief complaint: Dyspnea, cough

Past medical history: Schizophrenia

Lifestyle history: Smoking history: None, Alcohol consumption: Occasional

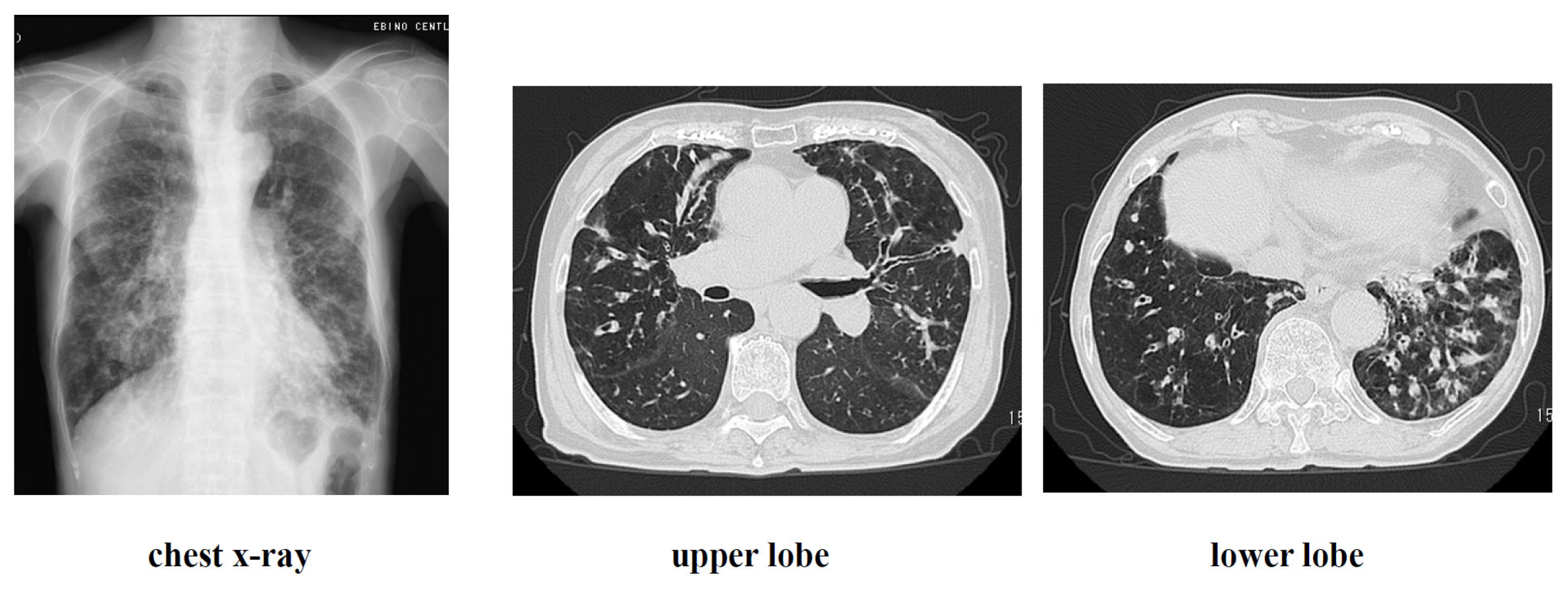

History of current illness: Approximately 3 years ago, the patient visited a local physician complaining of dyspnea, cough, and slight fever. Chest CT scan revealed granular and nodular shadows in both lung fields (Figure). Sputum culture revealed no significant bacteriological changes in the sputum. A blood test revealed positive MAC antibodies, leading to a tentative diagnosis of pulmonary MAC disease. Erythromycin (EM) 400 mg/day was administered, but symptoms gradually worsened over approximately 3 years. M. avium was detected twice in sputum cultures. A diagnosis of nodular bronchiectasis was made, and outpatient treatment with CAM 800 mg/day, RFP 300 mg/day, and EB 250 mg/day was initiated. Treatment continued for approximately one month, but the cough, low-grade fever, and dyspnea did not improve. Furthermore, imaging findings worsened, loss of appetite developed, and the patient's overall condition worsened. Consequently, the patient was diagnosed with refractory pulmonary MAC disease and hospitalized, and ALIS therapy was initiated. At the time of admission, the patient's height was 148 cm, weight was 32 kg, temperature was 37.5°C, blood pressure was 98/78 mmHg, pulse rate was 98 beats/min, and arrhythmia was present.

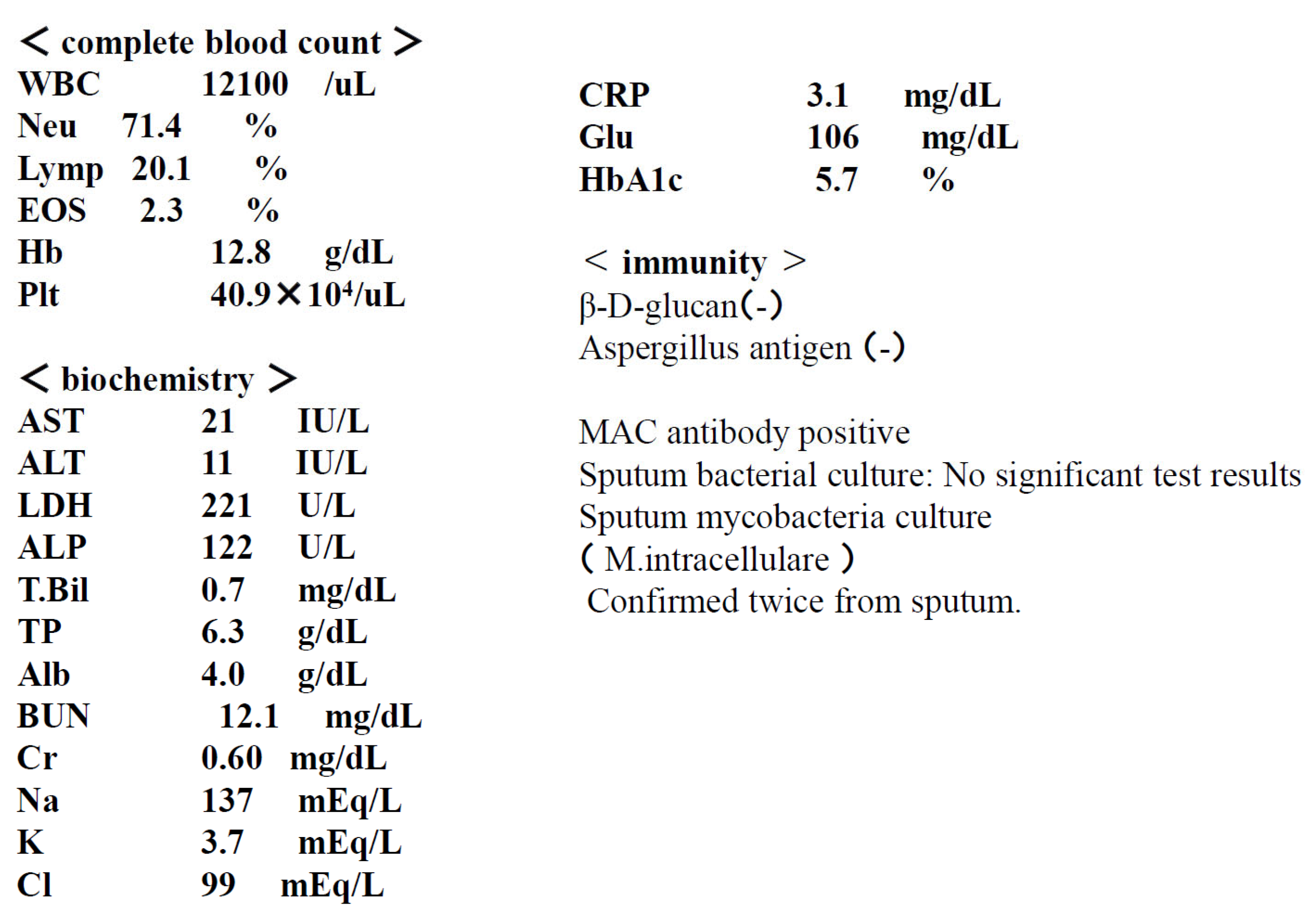

Figure 7.

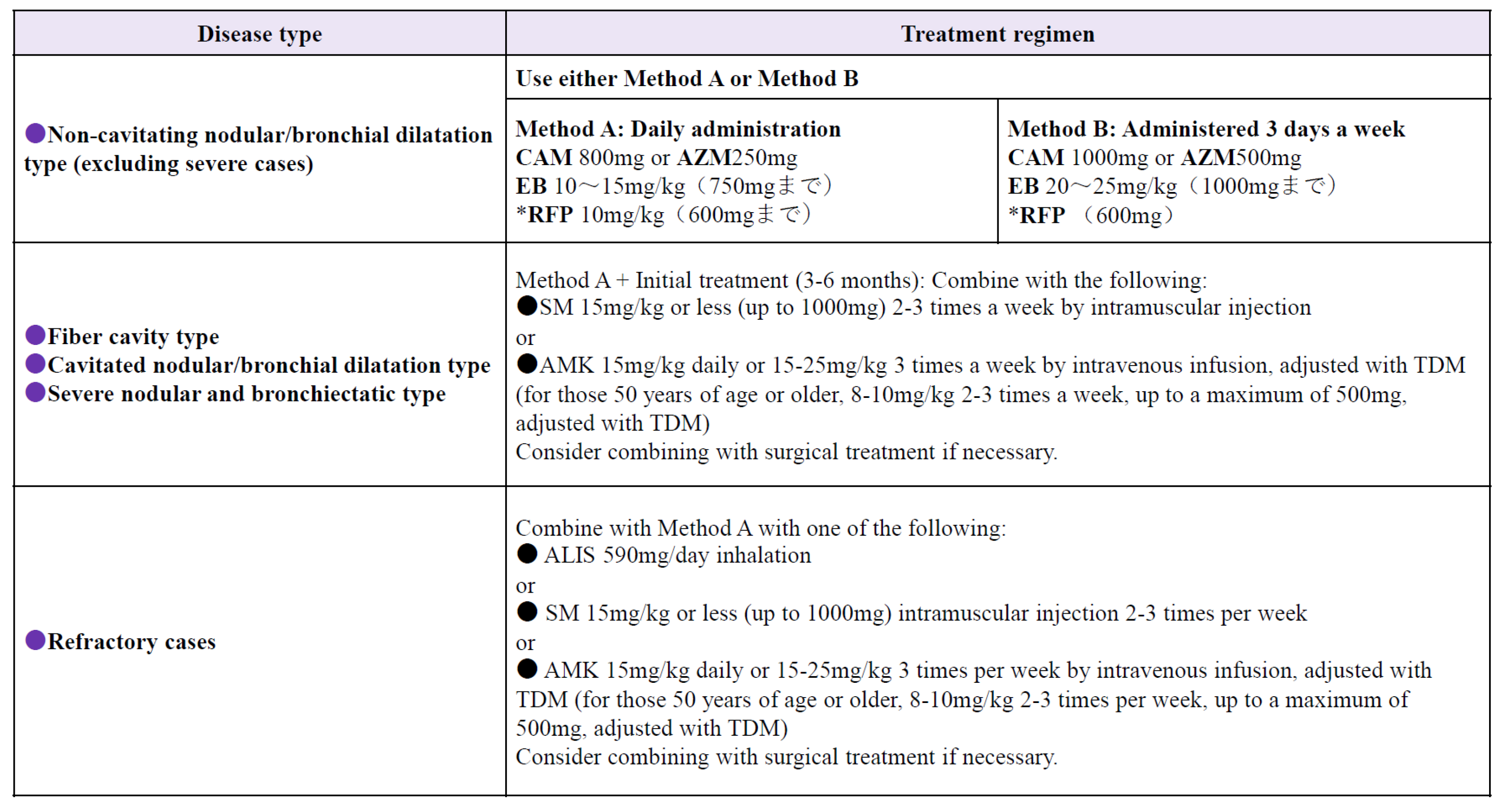

Test results at the time of admission.

Figure 7.

Test results at the time of admission.

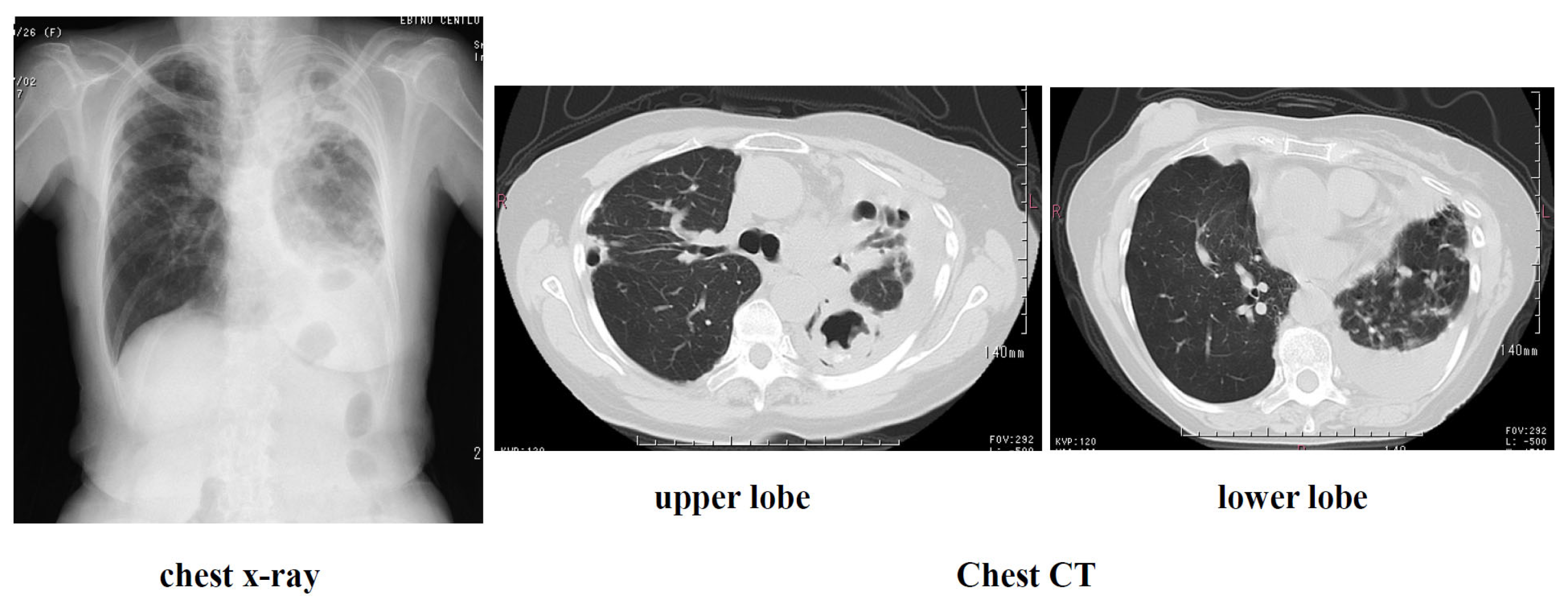

Figure 8.

Imaging findings at admission.

Figure 8.

Imaging findings at admission.

No lymph nodes were palpable, cardiac rhythm was irregular, lung sounds were intermittent, respiratory rate was 19 breaths/min, and the abdomen was flat and soft, with no tenderness. A right mastectomy was performed, but no abnormalities were found in the extremities.Chest X-ray examination at the time of admission suggested the possibility of bacterial pneumonia, and MEPM 3g/day and fluid replacement were initiated to treat the patient's loss of appetite. Fever and dyspnea improved within approximately one week. MEPM and oxygen administration were discontinued. During the hospitalization, the patient and family received approximately two weeks of instruction on how to use and clean the ALIS inhaler. After discharge, treatment with ALIS was initiated, with inhalation once daily, three times a week. This was because the patient's advanced age and schizophrenia made it impossible to continue treatment without the presence of family members. (

Figure 9)

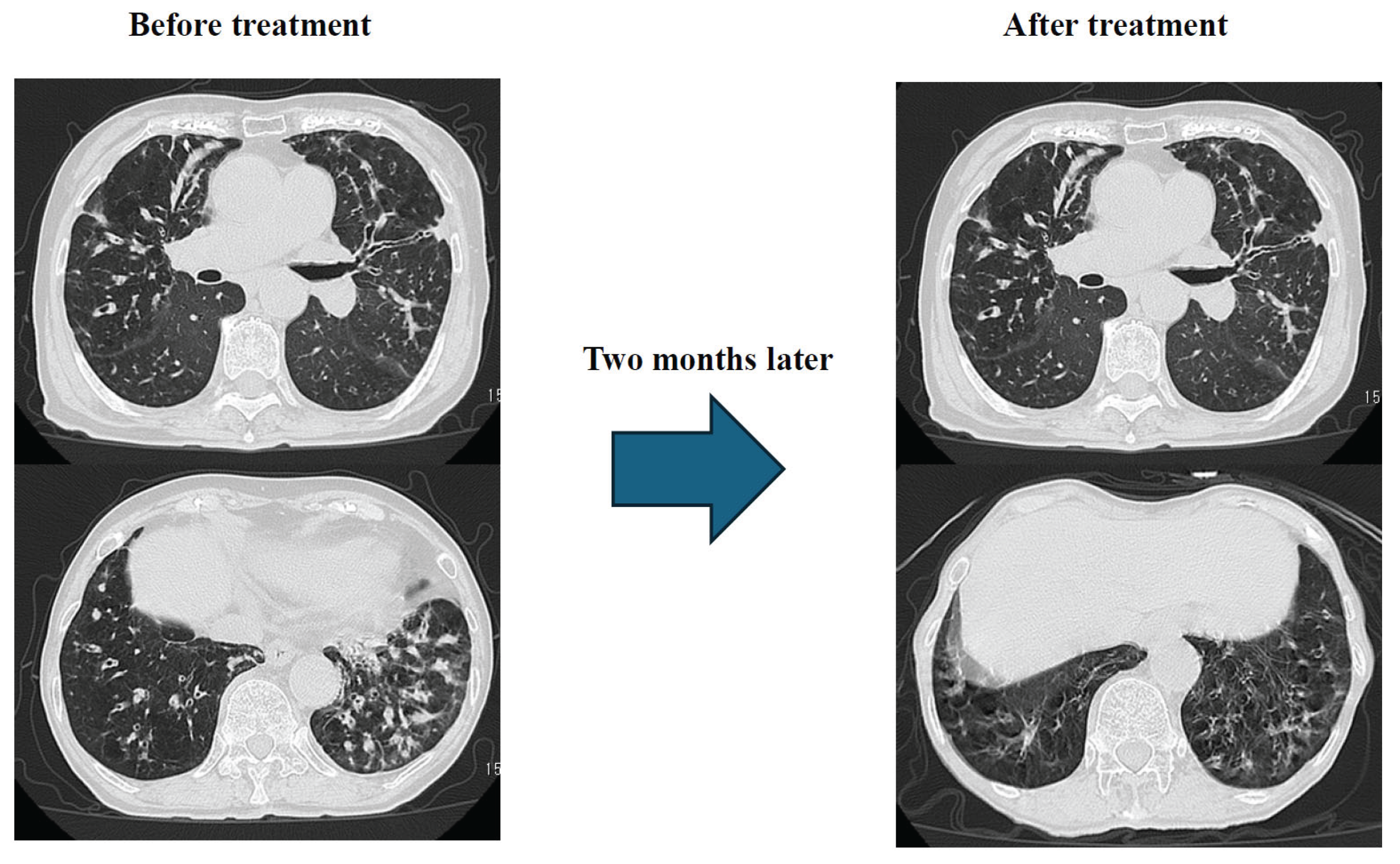

Results: Just two months after the start of treatment, dyspnea, cough, and low-grade fever had almost completely resolved. Chest CT scan showed significant improvement in granular and infiltrative opacities, particularly in the lower lobes (

Figure 10).

Sputum acid-fast bacillus testing revealed M. avium, and treatment with CAM 800 mg/day, EB 250 mg/day, and ALIS (single inhalation, once daily, three times weekly) is ongoing.

3. Discussion

In Case 1, the patient had pre-existing breast cancer, and the immunosuppressive state caused by the cancer-bearing condition is thought to have contributed to the progression of pulmonary MAC disease, leading to a deterioration in the patient's overall condition. The diagnosis was fibrocavitary pulmonary MAC disease and pleurisy. While pleurisy is considered rare in nontuberculous mycobacterial disease (NTM disease), Ichiki et al. have reported 9 cases out of 309 cases of NTM disease, and as with this case, left pleural effusion is common. (14) Although no significant bacteria were identified in thoracentesis or bacterial culture, no malignant findings were detected in cytology, and the diagnosis of pulmonary MAC disease and pleurisy is not inconsistent.(15) Initially, in accordance with the guidelines of the Japanese Respiratory Society and the Tuberculosis Society, administration of CAM 800 mg/day, RFP 300 mg/day, and EB 250 mg/day was initiated. However, due to severe liver damage and loss of appetite, which was thought to be due to the effects of RFP, it was difficult to continue treatment and no improvement was observed. Although amikacin intravenous formulation would normally be used, we decided to use ALIS, which is highly effective and has few side effects. As a result, the patient was diagnosed with refractory pulmonary MAC disease, and treatment was changed to CAM 800 mg/day, EB 250 mg/day, and ALIS, one inhalation once daily, twice a week. The reasons for changing to twice-weekly treatment were that the patient's general condition was poor, and because the patient was elderly and had limited comprehension, it was considered difficult for the patient to use ALIS alone, as the inhalation method and inhaler cleaning procedures were complicated. Therefore, it was considered necessary for a family member to accompany the patient, and twice-weekly treatment was the most feasible frequency. Although the inhalation dose was less than half the usual daily dose, pleural effusion and imaging improved, and subjective symptoms also improved significantly. No side effects were observed. Case 2 was a case in which imaging findings and blood tests showed strong positive anti-MAC antibodies three years ago, but a definitive diagnosis was not possible due to a negative sputum acid-fast bacillus culture test. The patient was being treated with EM, but symptoms worsened, likely due to a weakened immune system associated with aging. Sputum acid-fast bacillus culture tests showed two positive results for M. avium, and the patient was definitively diagnosed with nodular and bronchiectatic type. Administration of CAM 800mg/day, RFP 300mg/day, and EB 250mg/day was initiated, but symptoms such as fever, cough, and dyspnea, as well as imaging, showed little improvement, and loss of appetite also appeared, resulting in a deterioration in the patient's overall condition. The loss of appetite was likely due to the effects of RFP, so the treatment was discontinued. As the condition was intractable, the treatment regimen was changed to CAM 800mg/day, EB 250mg/day, and ALIS, one inhalation once daily, three times per week. The reason for administering ALIS three times a week is that the patients are elderly, suffer from schizophrenia and are not very understanding, and there were only three days a week when the family could be with them to ensure the administration was correct. In this case too, there was a significant improvement in symptoms and chest images just two months after starting administration. No side effects occurred in this case either.

In both of these cases, the patients were elderly women who had become immunosuppressed due to coexisting illnesses and age, and their pulmonary MAC disease became severe, and they were successfully treated with a regimen using ALIS.

ALIS is an aminoglycoside antibiotic that works by binding to bacterial liposomes and inhibiting protein synthesis. The most notable features of this innovative drug are its unique liposomal amikacin technology and dedicated inhaler. This allows amikacin to be efficiently delivered to alveolar macrophages, where it directly kills MAC bacteria. It has been reported to be effective in Japanese patients, with mild side effects such as hoarseness remaining unresolved (16, 17). However, challenges remain. The inhaler requires unique cleaning and inhalation procedures, and many patients with pulmonary MAC disease require medical treatment. These patients are often elderly, malnourished, or have underlying conditions that suppress the immune system, making it difficult for them to continue treatment on their own.making it difficult to implement. Furthermore, Oshita et al. reported 11 case studies in which a regimen using ALIS was effective, but side effects such as hoarseness and dysphonia inevitably occurred, posing a challenge to continued treatment. (18)

In this case, inhaler use was successfully implemented with the cooperation of the patient's family. It was suggested that inhaler use, even two to three times a week, was effective and did not necessarily require daily use. Furthermore, the reduced frequency of use may reduce the likelihood of side effects.

4. Conclusions

ALIS is an aminoglycoside antibiotic that works by binding to bacterial liposomes and inhibiting protein synthesis. Its greatest feature is its revolutionary, unprecedented effect: by using amikacin liposome technology and a dedicated inhaler, it efficiently reaches alveolar macrophages and directly kills MAC bacteria within them. However, due to the specialized administration method that requires inhaler cleaning, continuous use is difficult for patients with refractory pulmonary MAC disease. Even when treatment is possible, hoarseness and dysphonia are often present, hindering the introduction of ALIS.

In these two cases, treatment was possible with the cooperation of the patient's family, and no side effects were observed. Treatment was effective with fewer treatment sessions than usual. These findings suggest that inhaled antibiotics, a new drug delivery method, not only offers a new treatment option when existing medications are ineffective or cannot be used for some reason, but also has the potential to be highly effective and safe for elderly patients.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Griffith, D.E.; Aksamit, T.; Brown-Elliott, B.A.; Catanzaro, A.; Daley, C.; Gordin, F.; Holland, S.M.; Horsburgh, R.; Huitt, G.; Iademarco, M.F.; et al. An Official ATS/IDSA Statement: Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention of Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Diseases. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 175, 367–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namkoong, H; Kurashima, A; Morimoto, K. : Epidemi- ology of Pulmonary Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Disease, Japan. Emerg Infect Dis. 2016, 22, 1116‒7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stout, J.E.; Koh, W.-J.; Yew, W.W. Update on pulmonary disease due to non-tuberculous mycobacteria. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2016, 45, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Japan Tuberculosis Society Non-tuberculous Mycobacterial Disease Control Committee. Japanese Respiratory Society Infectious Diseases and Tuberculosis Scientific Committee: Views on Chemotherapy for Pulmonary Non-tuberculous Mycobacterial Diseases - Revised 2012. Tuberculosis 2012, 87, 83–86. [Google Scholar]

- Moro, H; Kikuchi, T. Mycobacterium infection(s tuberculosis and nontuberculous mycobacteriosis). In Lung Disease Associated with Rheumatoid Arthritis; Tokuda, H, Ed.; Springer Japan: Tokyo, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Committee on Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Disease Control, Japanese Society for Tuberculosis, and the Infectious Diseases and Tuberculosis Academic Division of the Japanese Respiratory Society: Opinion on Chemotherapy for Pulmonary Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Disease - 2012 Revision. Tuberculosis 2012, 87, 83–86.

- Japanese Society of Tuberculosis Disease Control Committee for Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Diseases, Japanese Respiratory Society Infectious Diseases and Tuberculosis Scientific Committee: Guidelines for Diagnosis of Pulmonary Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Diseases - 2008. Tuberculosis 2008, 83, 525–526.

- Kobashi, Y.; Matsushima, T.; Oka, M. A double-blind randomized study of aminoglycoside infusion with combined therapy for pulmonary Mycobacterium avium complex disease. Respir. Med. 2007, 101, 130–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Ingen, J; Ferro, BE; Hoefsloot, W. : Drug treatment of pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease in HIV- negative patients: the evidence. Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther. 2013, 11, 1065–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, HB; Jiang, RH; Li, L. Treatment outcomes for Myco- bacterium avium complex: a systematic review and meta- analysis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014, 33, 347 ‒ 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J; et al. Front Microbiol 2018, 9, 915. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenzler, E; et al. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2016, 29, 581–632. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Z; et al. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2008, 21(3), 245–254. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ichki, T. Nichikokyuukaishi. 2011, 49(12). [Google Scholar]

- Japan Society for Tuberculosis and Non-tuberculous Mycobacterial Diseases, Committee on Non-tuberculous Mycobacterial Diseases, Japanese Respiratory Society, Infectious Diseases and Tuberculosis Scientific Subcommittee. Tuberculosis 2023, 98(5), 1–11.

- Griffith, DE. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018, 198, 1559–1569. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Morimoto, K. Respir investing. 2024, 62, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Oshita, G. Nichikokyuukaishi. 2024, 13(5). [Google Scholar]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).