Submitted:

10 October 2025

Posted:

13 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

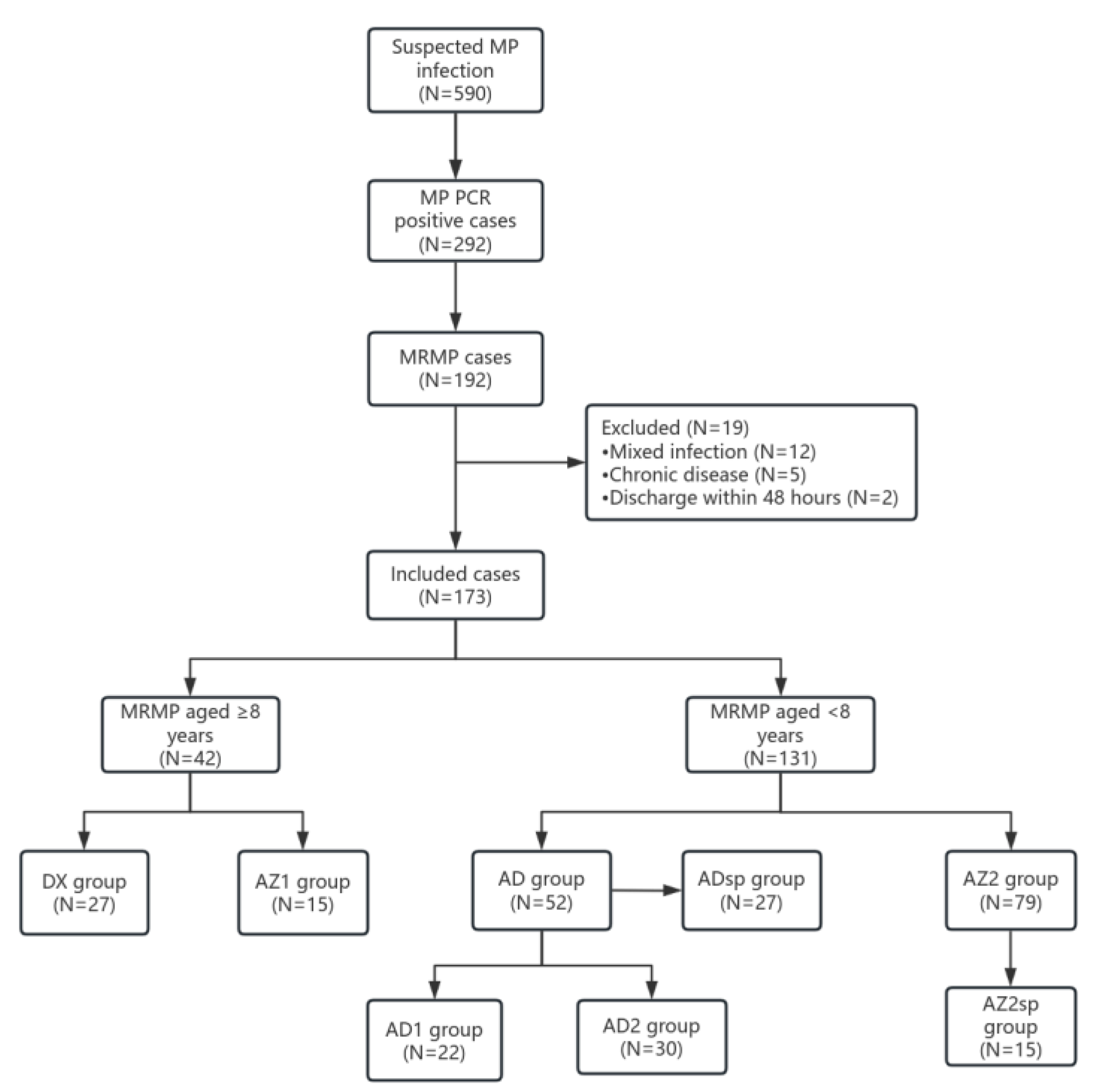

2.1. Study Subjects

3. Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Statistical Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

4.2. Comparisons of Clinical Courses After Therapy

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Consent for Publication

Competing Interests

References

- Oishi T, Ouchi K: Recent Trends in the Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Macrolide-Resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2022, 11, 1–8.

- Gu H, Zhu Y, Zhou Y, Huang T, Zhang S, Zhao D, Liu F: LncRNA MALAT1 Affects Mycoplasma pneumoniae Pneumonia via NF-κB Regulation. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology 2020, 8, 1–12.

- Beeton ML, Zhang X-S, Uldum SA, Bébéar C, Dumke R, Gullsby K, Ieven M, Loens K, Nir-Paz R, Pereyre S et al: Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections, 11 countries in Europe and Israel, 2011 to 2016. Eurosurveillance 2020, 25, 1–13.

- Lee H, Yun KW, Lee HJ, Choi EH: Antimicrobial therapy of macrolide-resistantMycoplasma pneumoniaepneumonia in children. Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy 2017, 16, 23–34.

- Tanaka T, Oishi T, Miyata I, Wakabayashi S, Kono M, Ono S, Kato A, Fukuda Y, Saito A, Kondo E et al: Macrolide-Resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae Infection, Japan, 2008–2015. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2017, 23, 1703–1706. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim K, Jung S, Kim M, Park S, Yang H-J, Lee E: Global Trends in the Proportion of Macrolide-Resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae Infections. JAMA Network Open 2022, 5, 1–12.

- Yan C, Xue G-H, Zhao H-Q, Feng Y-L, Cui J-H, Yuan J: Current status of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in China. World Journal of Pediatrics 2024, 20, 1–4. [CrossRef]

- Zhou Y, Shan Y, Cui Y, Shi J, Wang F, Miao H, Wang C, Zhang Y: Characteristics and Outcome of Severe Mycoplasma pneumoniae Pneumonia Admitted to PICU in Shanghai: A Retrospective Cohort Study. Critical Care Explorations 2021, 3, 1–8.

- Xu M, Li Y, Shi Y, Liu H, Tong X, Ma L, Gao J, Du Q, Du H, Liu D et al: Molecular epidemiology of Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in children, Wuhan, 2020–2022. BMC Microbiology 2024, 24, 1–11.

- Yang H-J: Benefits and risks of therapeutic alternatives for macrolide resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in children. Korean Journal of Pediatrics 2019, 62, 199–205. [CrossRef]

- Chen Y-C, Hsu W-Y, Chang T-H: Macrolide-Resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae Infections in Pediatric Community-Acquired Pneumonia. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2020, 26, 1382–1391. [CrossRef]

- Lanata MM, Wang H, Everhart K, Moore-Clingenpeel M, Ramilo O, Leber A: Macrolide-Resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae Infections in Children, Ohio, USA. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2021, 27, 1588–1597. [CrossRef]

- Wang Y-S, Zhou Y-L, Bai G-N, Li S-X, Xu D, Chen L-N, Chen X, Dong X-Y, Fu H-M, Fu Z et al: Expert consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in children. World Journal of Pediatrics 2024, 20, 901–914. [CrossRef]

- Cheng J, Liu Y, Zhang G, Tan L, Luo Z: Azithromycin Effectiveness in Children with Mutated Mycoplasma Pneumoniae Pneumonia. Infection and Drug Resistance 2024, 17, 2933–2942. [CrossRef]

- Commission NH: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Mycoplasma Pneumoniae Pneumonia in Children.

- (2023 Edition). Infect Dis Info 2023, 36, 291–297.

- Ahn JG, Cho H-K, Li D, Choi M, Lee J, Eun B-W, Jo DS, Park SE, Choi EH, Yang H-J, Kim KH: Efficacy of tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones for the treatment of macrolide-refractory Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infectious Diseases 2021, 21, 1–10.

- Cunha TA, Sibley CM, Ristuccia AM: Doxycycline. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring 1982, 4, 115–135.

- Zhu H, Wen Q, Bhangu SK, Ashokkumar M, Cavalieri F: Sonosynthesis of nanobiotics with antimicrobial and antioxidant properties. Ultrasonics Sonochemistry 2022, 86, 1–8.

- Lee H, Choi YY, Sohn YJ, Kim YK, Han MS, Yun KW, Kim K, Park JY, Choi JH, Cho EY, Choi EH: Clinical Efficacy of Doxycycline for Treatment of Macrolide-Resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae Pneumonia in Children. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 1–11.

- Chen Y, Zhang Y, Tang Q-N, Shi H-B: Efficacy of doxycycline therapy for macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in children at different periods. Italian Journal of Pediatrics 2024, 50, 1–8.

- Fredeking TM, Zavala-Castro JE, González-Martínez P, Moguel-Rodríguez W, Sanchez EC, Foster MJ, Diaz-Quijano FA: Dengue Patients Treated with Doxycycline Showed Lower Mortality Associated to a Reduction in IL-6 and TNF Levels. Recent Patents on Anti-Infective Drug Discovery 2015, 10, 51–58. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh B, Ghosh N, Saha D, Sarkar S, Bhattacharyya P, Chaudhury K: Effect of doxycyline in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease - An exploratory study. Pulmonary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2019, 58, 1–9.

- Patel A, Khande H, Periasamy H, Mokale S: Immunomodulatory Effect of Doxycycline Ameliorates Systemic and Pulmonary Inflammation in a Murine Polymicrobial Sepsis Model. Inflammation 2020, 43, 1035–1043. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu Z, Yu Q, Qi G, Yang J, Ni Y, Ruan W, Fang L: Tigecycline-Induced Tooth Discoloration in Children Younger than Eight Years. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2021, 65, 1–4.

- Kim SJ, Kim EH, Lee M, Baek JY, Lee JY, Shin JH, Lim SM, Kim MY, Jung I, Ahn JG et al: Risk of Dental Discoloration and Enamel Dysplasia in Children Exposed to Tetracycline and Its Derivatives. Yonsei Medical Journal 2022, 63, 1113–1120. [CrossRef]

- Bolormaa E, Park JY, Choe YJ, Kang CR, Choe SA, Mylonakis E: Treatment of Macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae Pneumonia in Children: A Meta-analysis of Macrolides Versus Tetracyclines. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal 2024, 44, 200–206.

- Song X, Zhou N, Lu S, Gu C, Qiao X: New-generation tetracyclines for severe macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in children: a retrospective analysis. BMC Infectious Diseases 2024, 24, 1–10.

- Meyer Sauteur PM: Childhood community-acquired pneumonia. European Journal of Pediatrics 2023, 183, 1129–1136. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Subspecialty Group of Respiratory tSoP, Chinese Medical Association; China National Clinical Research Center of Respiratory Diseases; the Editorial Board, Chinese Journal of Pediatrics: Evidence-based guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in children (2023). Chin J Pediatr 2024, 62, 1137–1144.

- Kumar S, Kumar S: Mycoplasma pneumoniae: Among the smallest bacterial pathogens with great clinical significance in children. Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology 2023, 46, 1–5.

- Jiang T-t, Sun L, Wang T-y, Qi H, Tang H, Wang Y-c, Han Q, Shi X-q, Bi J, Jiao W-w, Shen Ad: The clinical significance of macrolide resistance in pediatric Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection during COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology 2023, 13, 01–09.

- Song Z, Jia G, Luo G, Han C, Zhang B, Wang X: Global research trends of Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in children: a bibliometric analysis. Frontiers in Pediatrics 2023, 11, 01–16.

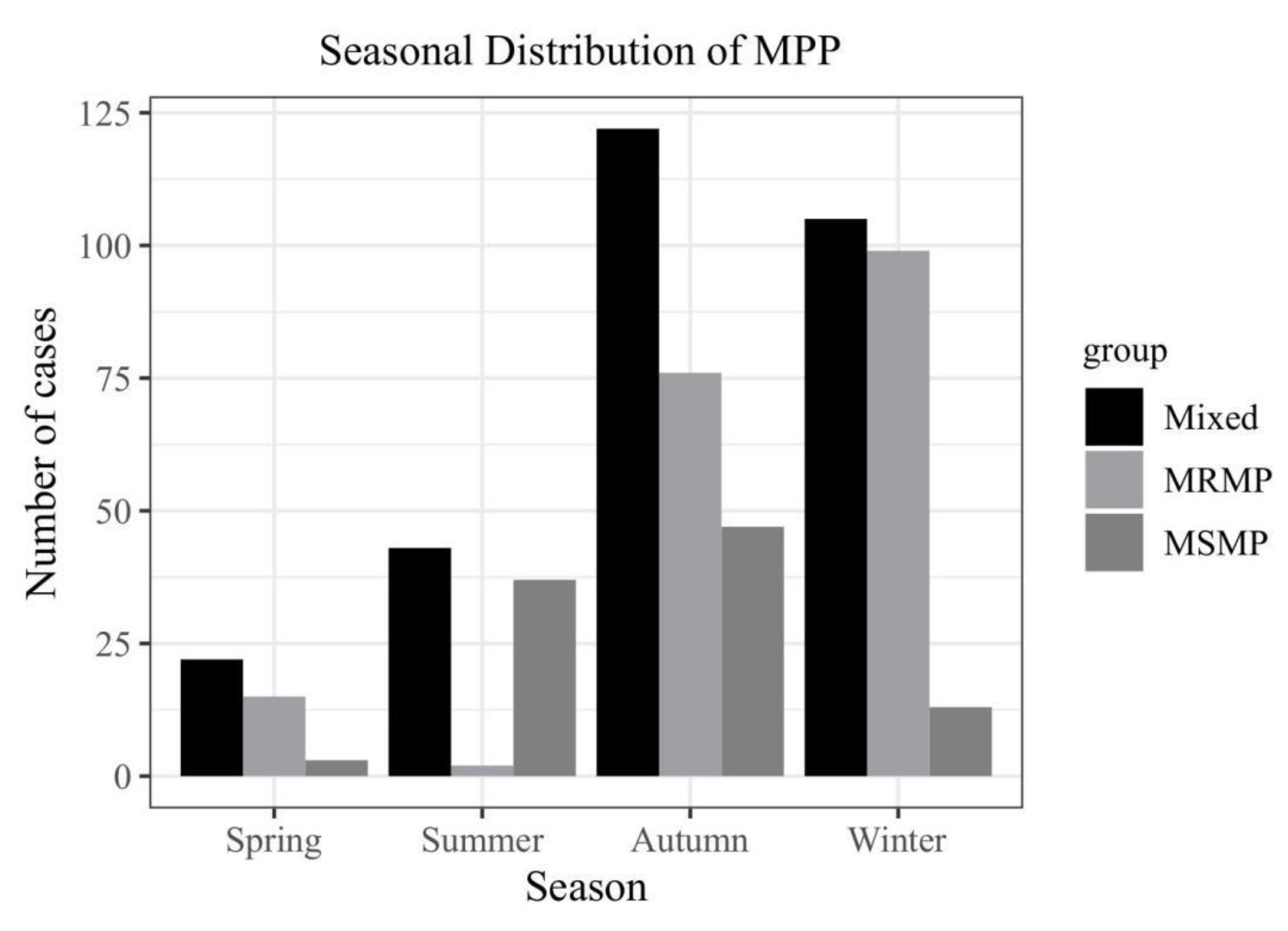

- Akashi Y, Hayashi D, Suzuki H, Shiigai M, Kanemoto K, Notake S, Ishiodori T, Ishikawa H, Imai H: Clinical features and seasonal variations in the prevalence of macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Journal of General and Family Medicine 2018, 19, 191–197. [CrossRef]

- Rothstein TE, Cunningham SA, Rieke RA, Mainella JM, Mutchler MM, Patel R: Macrolide Resistance in Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Midwestern United States, 2014 to 2021. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2022, 66, 1–5.

- Wang X, Li M, Luo M, Luo Q, Kang L, Xie H, Wang Y, Yu X, Li A, Dong M et al: Mycoplasma pneumoniae.

- triggers pneumonia epidemic in autumn and winter in Beijing: a multicentre, population-based epidemiological study between 2015 and 2020. Emerging Microbes & Infections 2022, 11, 1508–1517. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao F, Li J, Liu J, Guan X, Gong J, Liu L, He L, Meng F, Zhang J: Antimicrobial susceptibility and molecular characteristics of Mycoplasma pneumoniae isolates across different regions of China. Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control 2019, 8, 1–8.

- Morozumi M, Ubukata K, Takahashi T: Macrolide-resistant Mycoplasma pneumoniae: characteristics of isolates and clinical aspects of community-acquired pneumonia. Journal of Infection and Chemotherapy 2010, 16, 78–86. [CrossRef]

- Gianvecchio C, Lozano NA, Henderson C, Kalhori P, Bullivant A, Valencia A, Su L, Bello G, Wong M, Cook E et al: Variation in Mutant Prevention Concentrations. Frontiers in Microbiology 2019, 10, 1–9.

- Stultz JS, Eiland LS: Doxycycline and Tooth Discoloration in Children: Changing of Recommendations Based on Evidence of Safety. Annals of Pharmacotherapy 2019, 53, 1162–1166. [CrossRef]

- Qiao Y, Chen Y, Wang Q, Liu J, Guo X, Gu Q, Ding P, Zhang H, Mei H: Safety profiles of doxycycline, minocycline, and tigecycline in pediatric patients: a real-world pharmacovigilance analysis based on the FAERS database. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2024, 15, 01–14.

- Thompson EJ, Wu H, Melloni C, Balevic S, Sullivan JE, Laughon M, Clark KM, Kalra R, Mendley S, Payne EH et al: Population Pharmacokinetics of Doxycycline in Children. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 2019, 63, 1–12.

- Kuriakose K, Pettit AC, Schmitz J, Moncayo A, Bloch KC: Assessment of Risk Factors and Outcomes of Severe Ehrlichiosis Infection. JAMA Network Open 2020, 3, 1–12.

- Zhao Q, Sang X, Gao D, Zhang Z, Xuan A, Peng W: Efficacy and safety of doxycycline for severe Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia in pediatric patients. Clinical and Experimental Medicine 2025, 25, 1–18.

- Velušček M, Bajrović FF, Strle F, Stupica D: Doxycycline-induced photosensitivity in patients treated for erythema migrans. BMC Infectious Diseases 2018, 18, 1–5.

- Dou W, Liu X, An P, Zuo W, Zhang B: Real-world safety profile of tetracyclines in children younger than 8 years old: an analysis of FAERS database and review of case report. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety 2024, 23, 885–892. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maciag MC, Ward SL, O’Connell AE, Broyles AD: Hypersensitivity to tetracyclines. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology 2020, 124, 589–593.

| ≥8 years | P value | <8 years | P value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DX group | AZ1 group | AD group | AZ2 group | |||

| N=27 | N=15 | N=52 | N=79 | |||

| Age, years | 9.00±1.33 | 9.20±1.47 | 0.725 | 5.75±1.29 | 5.33±1.30 | 0.066 |

| Male gender (n,%) | 16(59.3%) | 8(53.3%) | 0.710 | 28(53.8%) | 39(49.4%) | 0.616 |

| Fever (n, %) | 27(100%) | 15(100%) | - | 52(100%) | 79(100%) | - |

| Cough (n, %)) | 27(100%) | 15(100%) | - | 52(100%) | 79(100%) | - |

| Duration of fever before treatment (d) | 3.37±1.57 | 3.40±1.29 | 0.286 | 3.27±1.65 | 3.14±1.68 | 0.664 |

| Cough duration before treatment (d) | 5.67±1.75 | 5.20±1.52 | 0.392 | 5.08±2.35 | 5.73±2.11 | 0.099 |

| Chest imaging findings(n, %) | 0.800 | 0.975 | ||||

| pulmonary consolidation | 14(51.9%) | 9(60.0%) | 22(42.3%) | 35(44.3%) | ||

| Interstitial Disease | 1(3.7%) | 1(6.7%) | 5(9.6%) | 8(10.1%) | ||

| Mixed Lesions | 7(25.9%) | 4(26.7%) | 19(36.5%) | 29(36.7%) | ||

| Pleural Effusion | 5(18.5%) | 1(6.7%) | 6(11.5%) | 7(8.9%) | ||

| Laboratory findings | ||||||

| White blood cell(×10^9/L) |

8.26±3.06 | 9.68±4.57 | 0.291 | 8.16±3.63 | 8.39±4.08 | 0.836 |

| Neutrophil (%) | 66.22±9.18 | 61.04±18.09 | 0.313 | 67.01±11.96 | 65.46±11.55 | 0.459 |

| Platelets (×10^9/L) | 296.03±92.50 | 311.86±113.52 | 0.627 | 293.96±106.97 | 308.84±106.72 | 0.317 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 123.33±10.76 | 123.60±8.66 | 0.935 | 118.58±9.29 | 119.51±9.52 | 0.582 |

| C-reactive protein(mg/L) |

23.38±19.53 | 25.18±26.13 | 0.815 | 22.69±15.67 | 24.65±33.98 | 0.273 |

| Procalcitonin (ng/mL) | 0.19±0.35 | 0.47±1.02 | 0.790 | 0.26±0.43 | 0.26±0.49 | 0.447 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) |

332.14±185.51 | 325.12±97.74 | 0.893 | 317.78±84.33 | 315.16±80.23 | 0.959 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/h) | 49.77±27.97 | 48.40±12.99 | 0.829 | 48.87±18.64 | 48.39±16.54 | 0.821 |

| Severe pneumonia (n, %) |

12(44.4%) | 6(40.0%) | 1.000 | 27(51.9%) | 15(19.0%) | 0.000 |

| AD1 group | AD2 group | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N=22 | N=30 | ||

| Age, years | 5.50±1.50 | 5.93±1.11 | 0.360 |

| Male gender (n,%) | 9(40.9%) | 19(63.3%) | 0.160 |

| Duration of fever before treatment (d) | 3.23±1.37 | 3.30±1.86 | 0.878 |

| Cough duration before treatment (d) | 5.64±2.17 | 4.67±2.44 | 0.145 |

| Chest imaging findings(n, %) | 0.373 | ||

| pulmonary consolidation | 8(36.4%) | 14(46.7%) | |

| Interstitial Disease | 1(4.5%) | 0(0.0%) | |

| Mixed Lesions | 10(45.5%) | 9(30.0%) | |

| Pleural Effusion | 3(13.6%) | 7(23.3%) | |

| Laboratory findings | |||

| White blood cell(×10^9/L) |

8.52±4.18 | 7.90±3.23 | 0.549 |

| Neutrophil (%) | 66.70 ±12.45 | 67.24±11.80 | 0.875 |

| Platelets (×10^9/L) | 300.14±109.48 | 289.43±106.74 | 0.725 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 118.36±7.82 | 118.73±10.36 | 0.889 |

| C-reactive protein(mg/L) |

20.38±12.98 | 24.39±17.4 | 0.368 |

| Procalcitonin (ng/mL) | 0.20±0.35 | 0.30±0.48 | 0.590 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) |

294.89±59.48 | 334.57±96.21 | 0.176 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/h) | 43.14±13.81 | 53.07±20.73 | 0.057 |

| Severe pneumonia (n, %) |

12(54.5%) | 15(50.0%) | 0.785 |

| AD group | AZ2 group | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N=27 | N=15 | ||

| Age, years | 5.74±1.37 | 4.80±2.04 | 0.129 |

| Male gender (n,%) | 16(59.3%) | 5(33.3%) | 0.107 |

| Duration of fever before treatment (d) | 2.85±1.70 | 3.00±1.85 | 0.799 |

| Cough duration before treatment (d) | 5.07±2.40 | 5.80±2.17 | 0.338 |

| Chest imaging findings(n, %) | 0.203 | ||

| pulmonary consolidation | 12(44.4%) | 4(26.7%) | |

| Interstitial Disease | 1(3.7%) | 3(20.0%) | |

| Mixed Lesions | 9(33.3%) | 7(46.7%) | |

| Pleural Effusion | 5(18.5%) | 1(6.7%) | |

| Laboratory findings | |||

| White blood cell(×10^9/L) |

8.32±4.23 | 7.83±3.15 | 0.865 |

| Neutrophil (%) | 65.83±13.99 | 60.94±8.87 | 0.230 |

| Platelets (×10^9/L) | 265.22±99.73 | 294.87±113.25 | 0.351 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 119.30±8.41 | 119.93±7.30 | 0.807 |

| C-reactive protein(mg/L) |

20.28±18.91 | 23.40±19.48 | 0.487 |

| Procalcitonin (ng/mL) | 0.38±0.57 | 0.23±0.48 | 0.351 |

| Lactate dehydrogenase (U/L) |

334.00±99.66 | 324.95±62.15 | 0.752 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/h) | 46.74±18.21 | 49.13±15.45 | 0.670 |

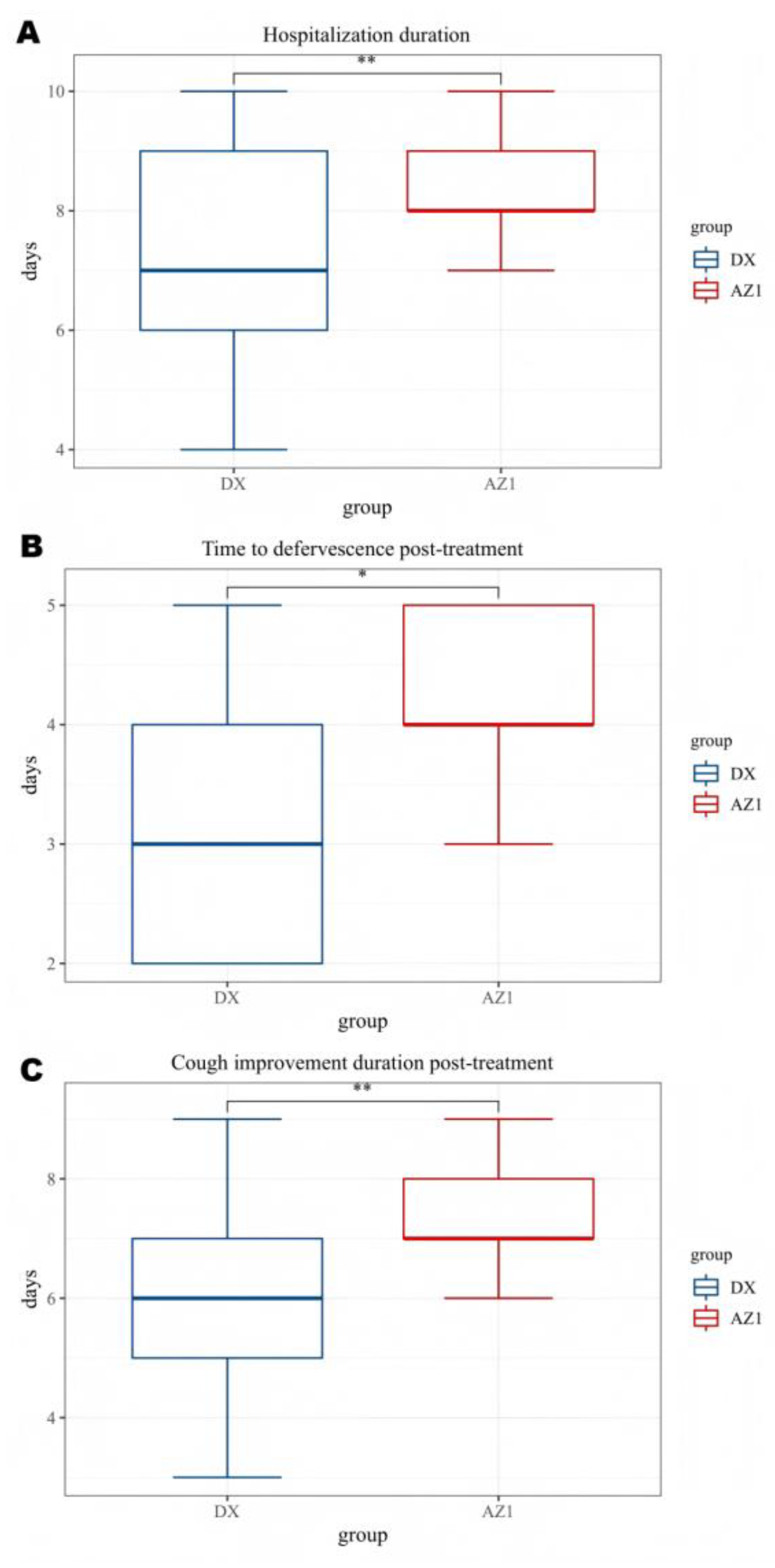

| DX group | AZ1 group | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N=27 | N=15 | ||

| Hospitalization duration(d) | 7.11±1.78 | 8.33±0.97 | 0.007 |

| Fever duration after treatment(d) |

3.37±1.18 | 4.33±0.72 | 0.011 |

| Antipyretic period | 0.020 | ||

| Defervescence within 72 h (n,%) | 14(51.9%) | 2(13.3%) | |

| Fever lasts more than 72 hours(n,%) | 13(48.1%) | 13(86.7%) | |

| Cough Improvement Duration After Treatment (d) | 5.96±1.76 | 7.33±0.97 | 0.008 |

| Improved chest imaging(n,%) | 17(63.0%) | 3(20.0%) | 0.011 |

| Glucocorticoids(n,%) | 20(74.1%) | 12(80.0%) | 1.000 |

| Glucocorticoids(d) | 2.15±1.81 | 4.07±2.49 | 0.013 |

| Immunoglobulin(n,%) | 4(14.8%) | 7(46.7%) | 0.034 |

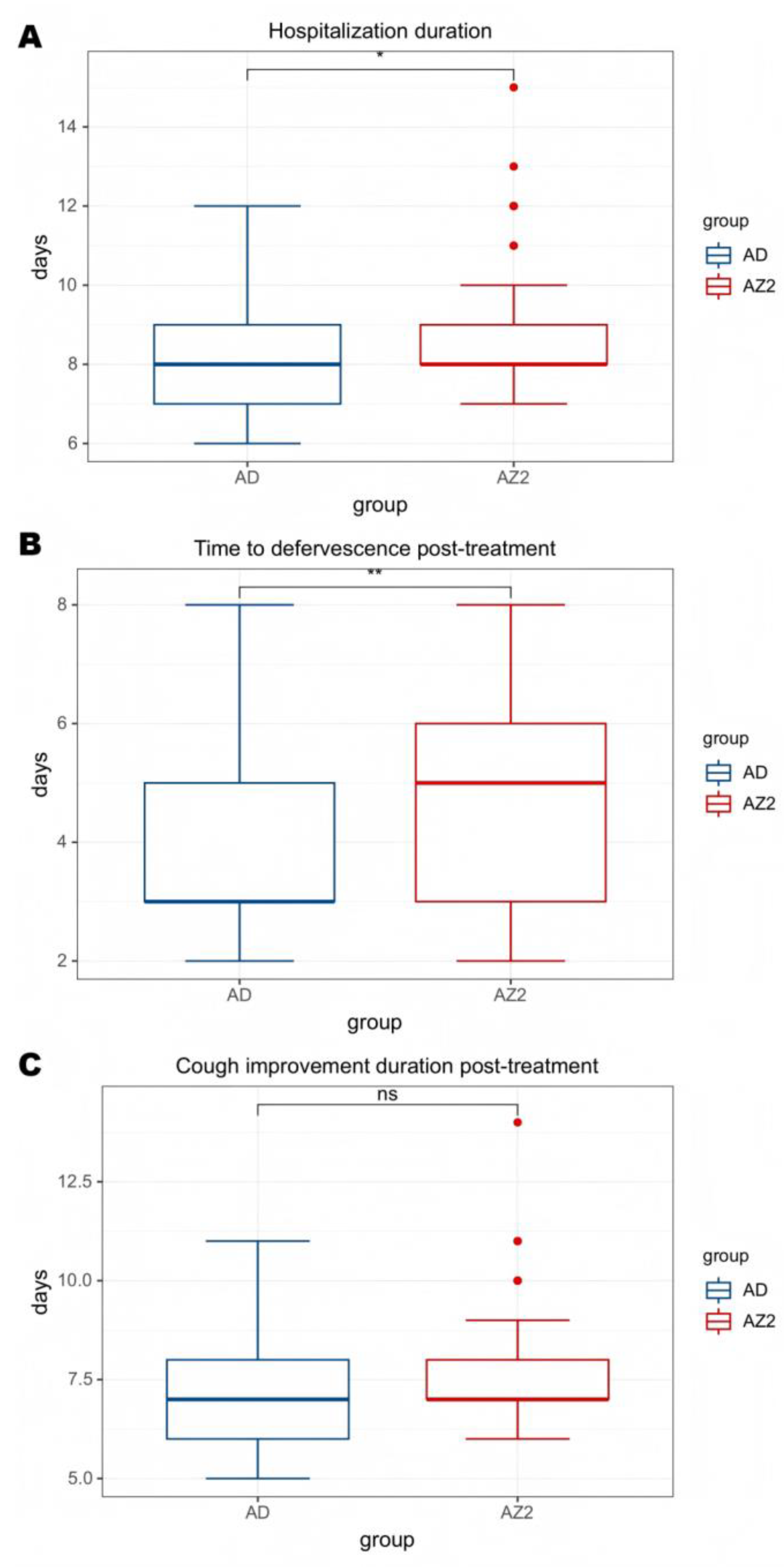

| AD group | AZ2 group | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N=52 | N=79 | ||

| Hospitalization duration(d) | 8.12±1.56 | 8.76±1.75 | 0.029 |

| Fever duration after treatment(d) |

3.85±1.60 | 4.65±1.51 | 0.005 |

| Antipyretic period | 0.000 | ||

| Defervescence within 72 h (n,%) | 32(61.5%) | 21(26.6%) | |

| Fever lasts more than 72 hours(n,%) | 20(38.5%) | 58(73.4%) | |

| Cough Improvement Duration After Treatment (d) | 7.06±1.61 | 7.61±1.56 | 0.056 |

| Improved chest imaging(n,%) | 31(59.6%) | 38(48.1%) | 0.215 |

| Glucocorticoids(n,%) | 39(75.0%) | 72(91.1%) | 0.015 |

| Glucocorticoids(d) | 3.96±2.55 | 4.14±1.91 | 0.649 |

| Immunoglobulin(n,%) | 13(25.0%) | 13(16.5%) | 0.266 |

| ADsp group | AZ2sp group | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N=27 | N=15 | ||

| Hospitalization duration(d) | 9.04±1.61 | 10.93±1.34 | 0.000 |

| Fever duration after treatment(d) | 4.52±1.87 | 5.73±1.58 | 0.032 |

| Antipyretic period | 0.000 | ||

| Defervescence within 72 h (n,%) | 14(51.9%) | 3(20.0%) | |

| Fever lasts more than 72 hours(n,%) | 13(48.1%) | 12(80.0%) | |

| Cough Improvement Duration After Treatment (d) | 8.04±1.61 | 9.00±1.31 | 0.043 |

| Improved chest imaging(n,%) | 18(66.7%) | 4(26.7%) | 0.023 |

| Glucocorticoids(n,%) | 20(74.1%) | 15(100%) | 0.038 |

| Glucocorticoids(d) | 4.52±2.86 | 6.07±0.88 | 0.049 |

| Immunoglobulin(n,%) | 7(25.9%) | 9(60.0%) | 0.047 |

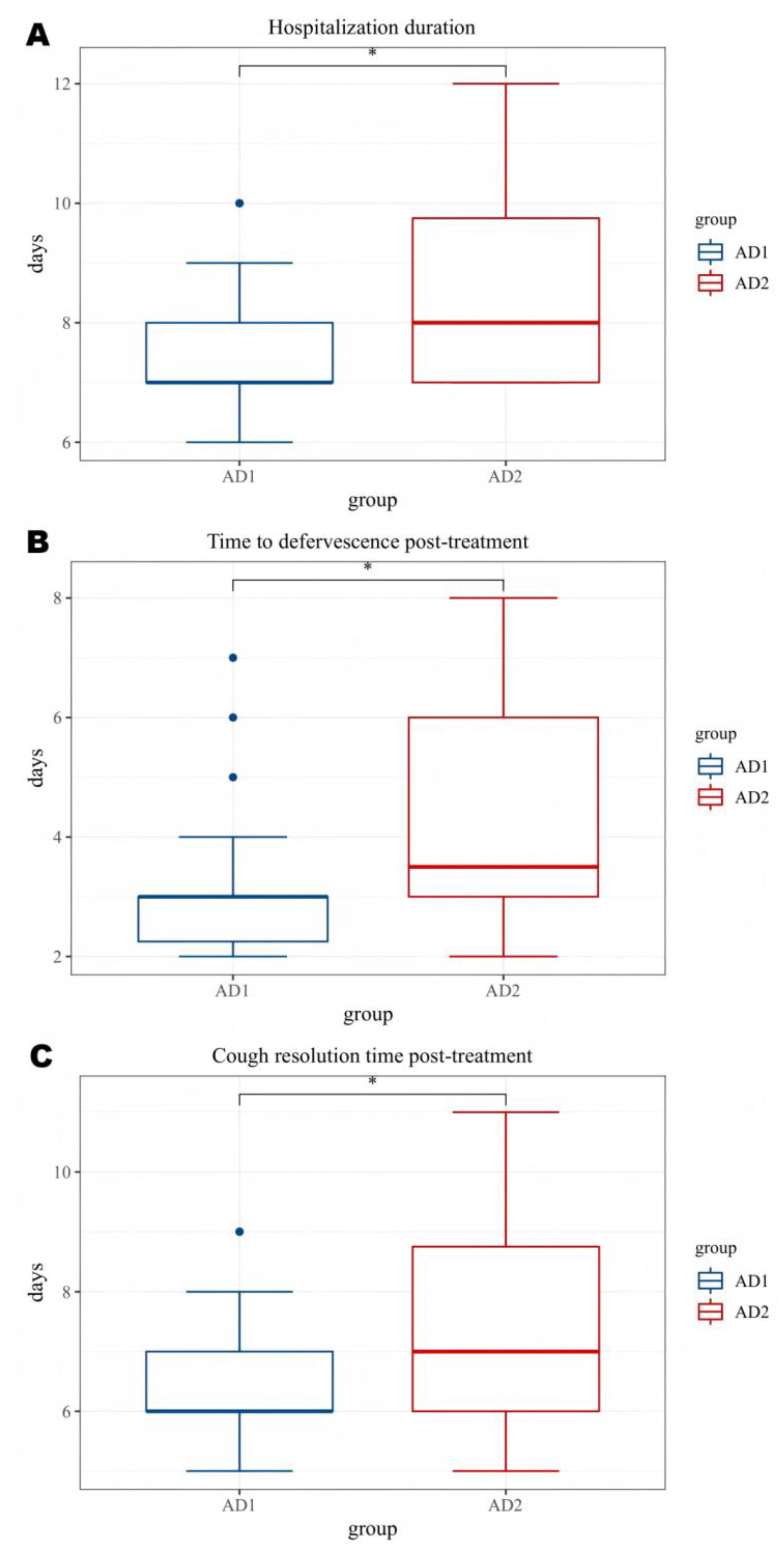

| AD1 group | AD2 group | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N=22 | N=30 | ||

| Hospitalization duration(d) | 7.50±1.10 | 8.57±1.70 | 0.013 |

| Fever duration after treatment(d) | 3.23±1.31 | 4.30±1.66 | 0.015 |

| Antipyretic period | 0.044 | ||

| Defervescence within 72 h (n,%) | 17(77.3%) | 14(46.7%) | |

| Fever lasts more than 72 hours(n,%) | 5(22.7%) | 16(53.3%) | |

| Cough Improvement Duration After Treatment (d) | 6.50±1.10 | 7.47±1.81 | 0.031 |

| Improved chest imaging(n,%) | 18(81.8%) | 13(43.3%) | 0.009 |

| Glucocorticoids(n,%) | 13(59.1%) | 26(86.7%) | 0.049 |

| Glucocorticoids(d) | 3.14±2.78 | 4.57±2.22 | 0.045 |

| Immunoglobulin(n,%) | 2(9.1%) | 11(36.7%) | 0.049 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).