Submitted:

14 December 2025

Posted:

16 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Methodological Framework Overview

- Theoretical modeling with Logic Eτ, which provides the inferential foundation for reasoning under uncertainty and contradiction, supporting key decision points in the system workflow.

- Experimental validation through Design of Experiments (DoE), conducted as proof-of-concept trials to tune system-level parameters affecting semantic retrieval, preprocessing, and generative behavior, rather than as large-scale validation.

- System implementation of the Decision Support AI-Copilot for Poutry Farming, developed as a modular RAG-based architecture that integrates LLMs with evidential reasoning mechanisms based on Logic Eτ.

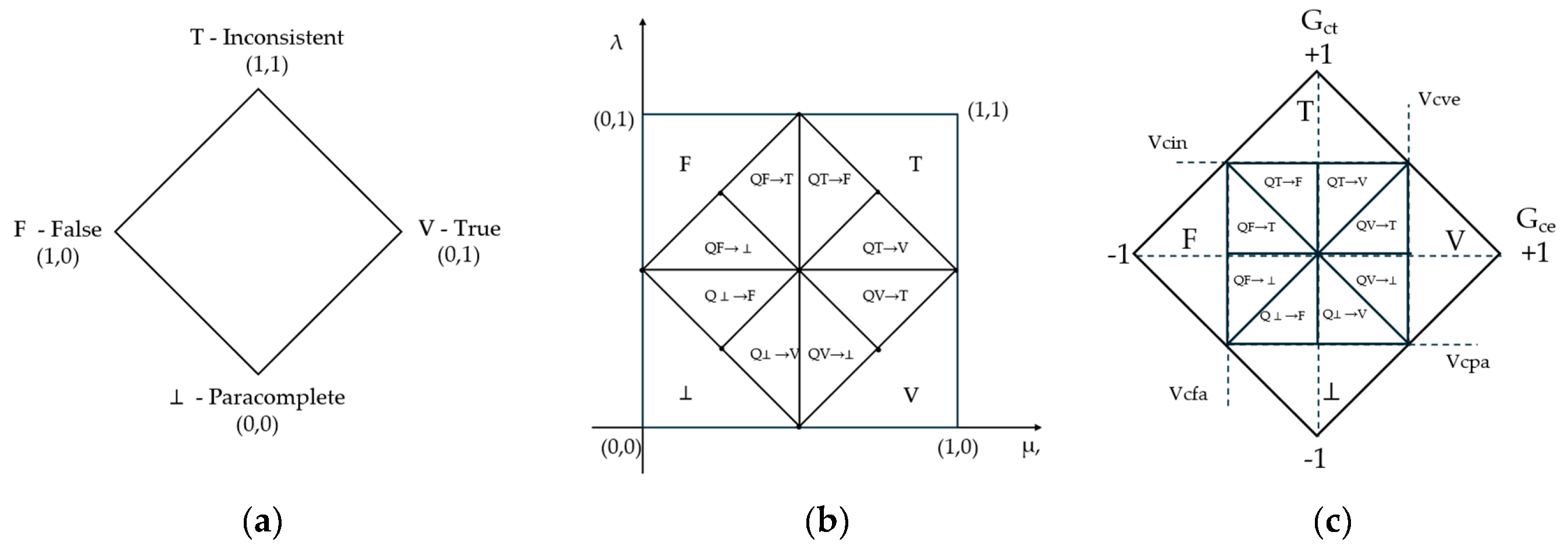

2.2. Evidential Inference with Logic Eτ

- 1.

- Lattice τ with Partial Order: This structure defines a complete lattice over the unit square [0,1] ², where each pair (μ, λ) encodes the degrees of favorable and unfavorable evidence about a proposition. A partial order is defined by:

- 2.

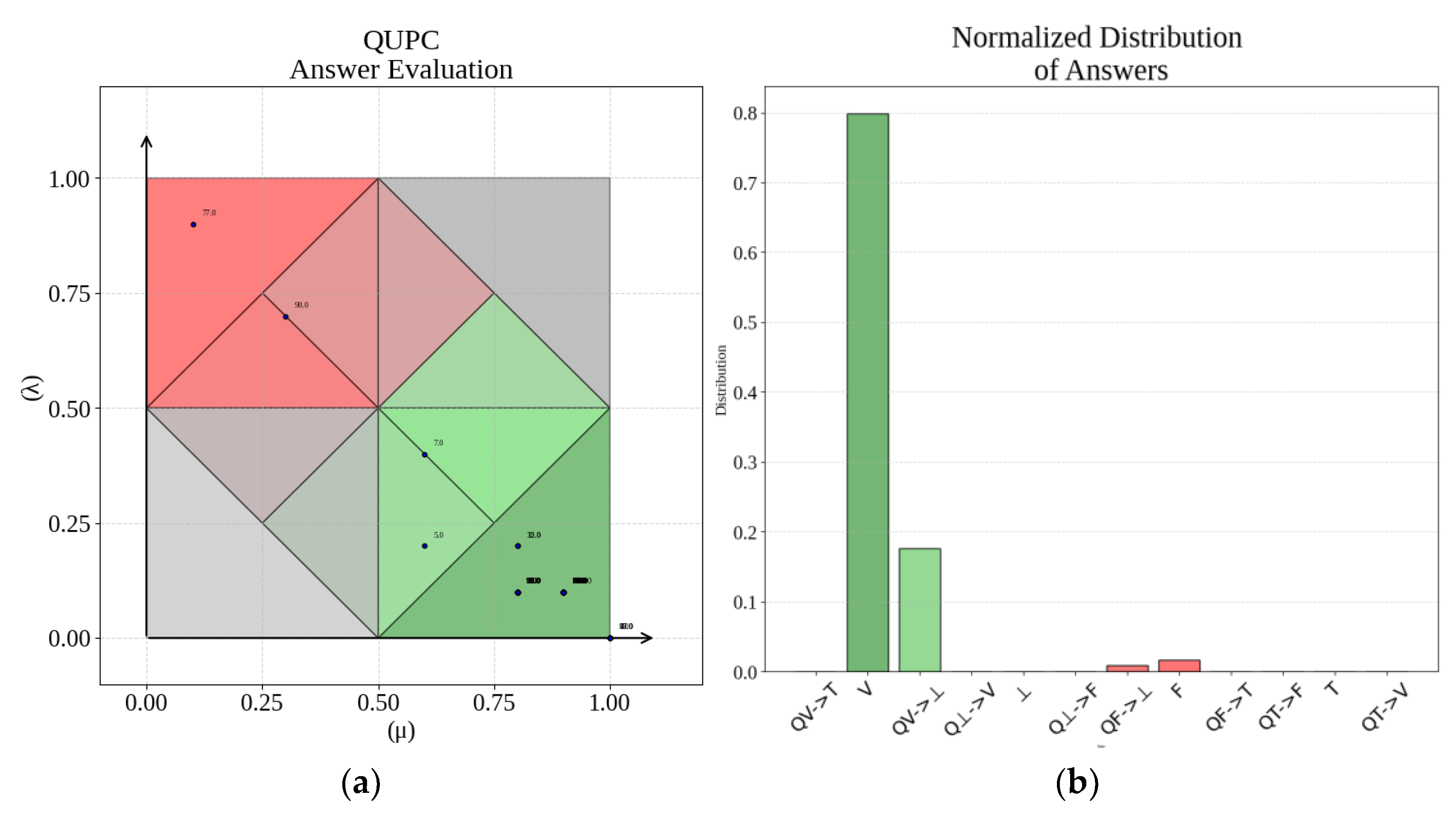

- USCP (Unit Square of the Cartesian Plane), from a geometric standpoint, the evidential lattice can be visualized as a unit square of the Cartesian plane. Each evidential pair (μ, λ) corresponds to a point in this 2D unit square (Figure 1b), allowing for an intuitive representation of the underlying information state. While the lattice defines logical and computational operations through ordering, the USCP offers a descriptive and analytic space for visualizing evidential distributions and for mapping them onto the logical plane [14,15,16,32].

- 3.

- Diagram of Certainty and Contradiction Degrees: A nonlinear transformation maps USCP into the logical diagram, where inference operates in Figure 1c. The transformation defines two axes: the certainty degree (Gce), and the contradiction degree (Gct).

2.3. Design of Experiments for System-Level Parameter Tuning

- 1.

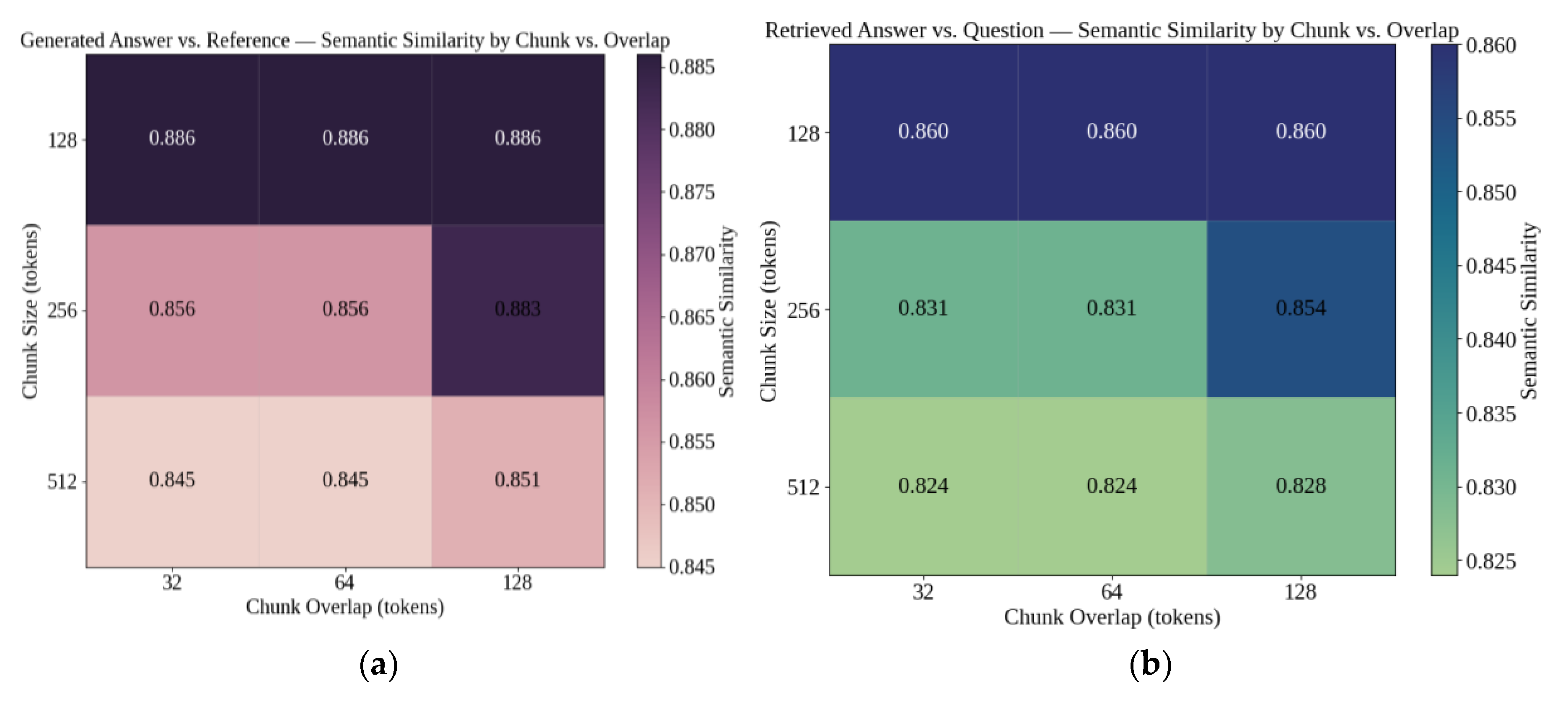

- Chunk Size and Overlap: In the RAG pipeline, chunk size refers to the number of tokens in each embedded segment, while overlap specifies the number of tokens repeated between adjacent chunks, directly affecting contextual continuity and information density. The interaction between these parameters affects retrieval precision, semantic cohesion, and computational efficiency [20].

- 2.

- Lemmatization: This preprocessing step reduces inflected or derived words to their base form (lemma), preserving grammatical context and semantic identity. By mapping morphological variants to a unified lexical representation, it may reduce embedding dispersion and improve retrieval alignment [22,23].

- 3.

- Normalization: This preprocessing step standardizes both the domain-specific corpus and the question–answer pairs by reducing superficial variability that does not affect meaning. It directly influences lexical alignment, improves embedding consistency, and enhances semantic matching, particularly in architectures where token-level similarity governs access to relevant content [24].

- 4.

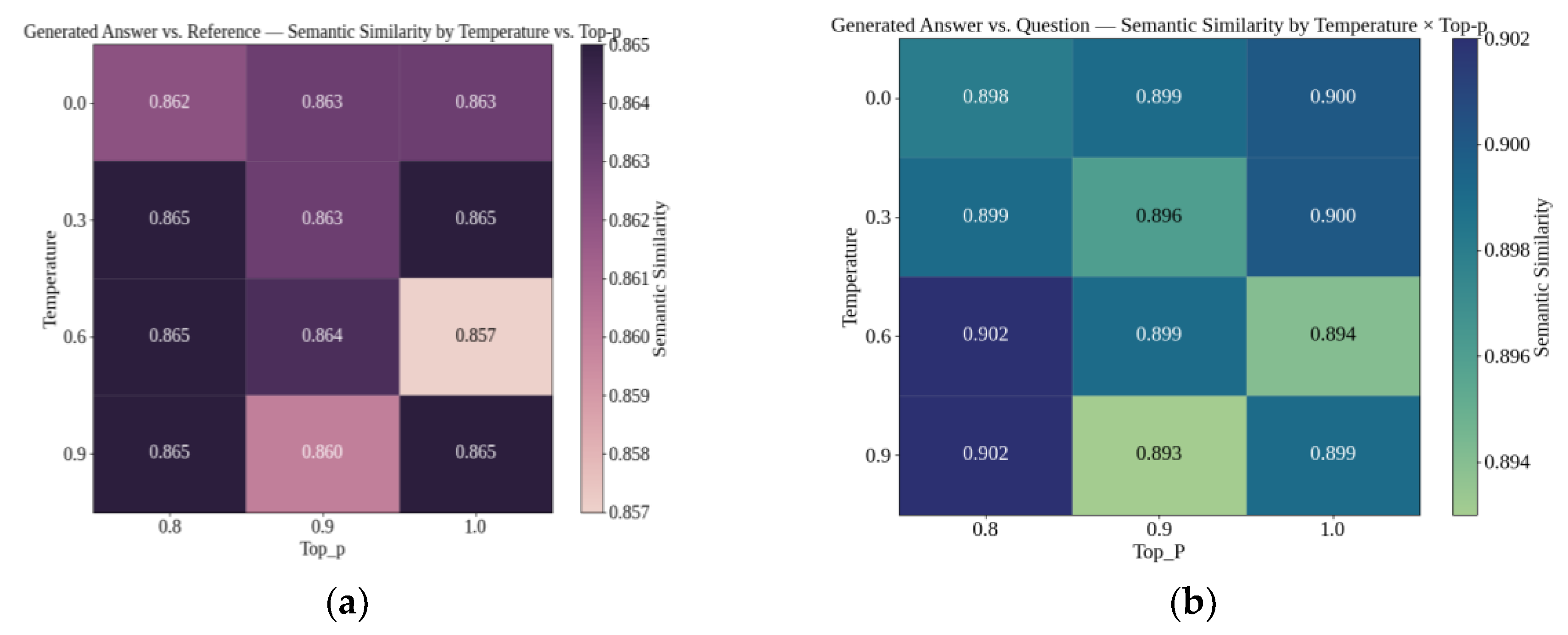

- Temperature and Top-p: The foundation model parameters regulate the stochastic behavior of the language model during response generation. Temperature controls the entropy of the output distribution, modulating the balance between determinism and exploration [26,27]. Top-p (nucleus sampling) constrains the sampling space to the smallest set of tokens whose cumulative probability exceeds a given threshold, shaping the diversity and unpredictability of the generated text [26,27].

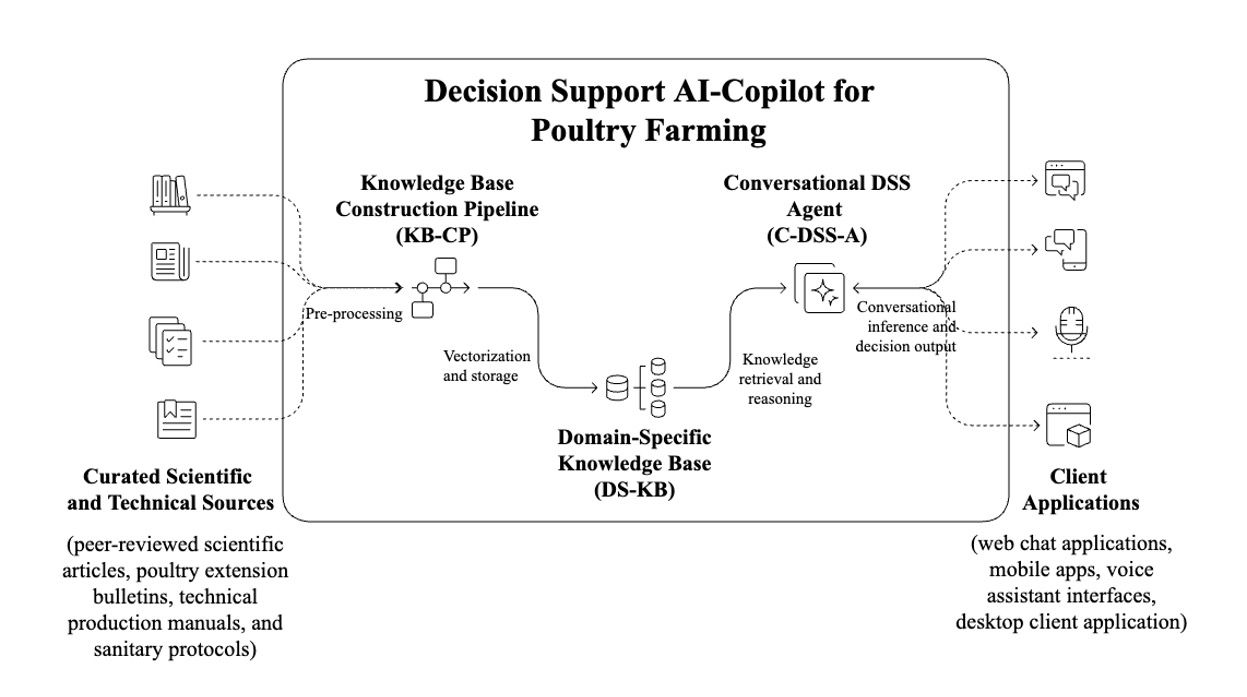

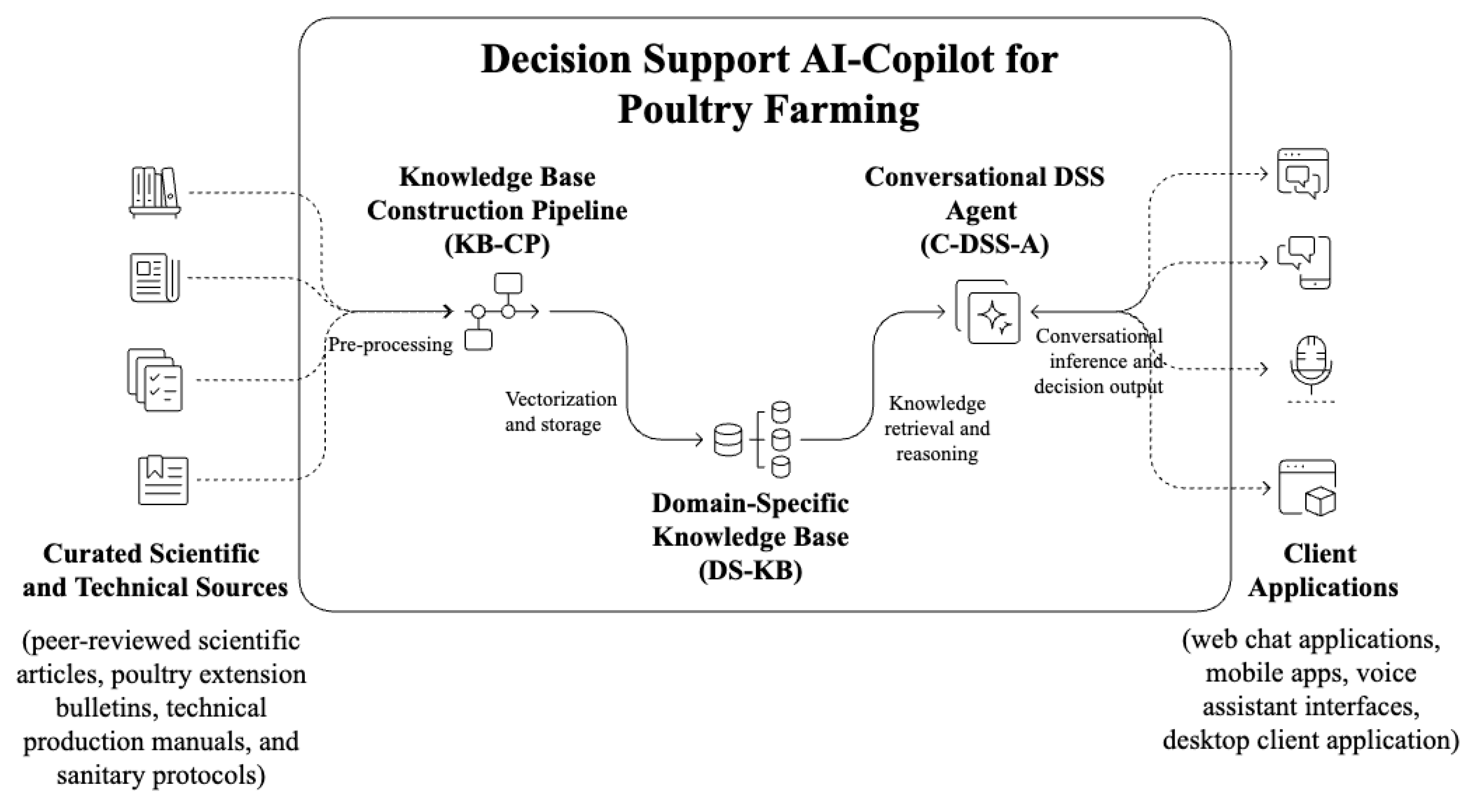

2.4. System Architecture

2.4.1. Knowledge Base Construction Pipeline (KB-CP)

-

Document Collection: A sample of 48 technical documents were curated from authoritative sources, including peer-reviewed scientific articles, poultry extension bulletins, technical production manuals, and sanitary protocols. The selection prioritized content with high informational density, practical relevance, and clear domain affiliation. Documents were collected through targeted searches in scientific databases, institutional repositories, and validated extension services.Domain Classification: Each document was manually assigned to one of five predefined poultry production domains: (i) Housing and Environmental Control, (ii) Animal Nutrition, (iii) Poultry Health, (iv) Husbandry Practices, and (v) Animal Welfare.These domains reflect core areas of technical decision-making in intensive poultry systems and are grounded in established animal welfare frameworks. The FAO’s work on poultry welfare identifies health, nutrition, environmental comfort, and welfare as core aspects of assessment [29,30,42,43,44]. Classification was performed based on thematic focus, terminology patterns, and stated objectives of the material. In cases of overlap, domain assignment favored the dominant technical axis addressed by the document.Preprocessing: All documents were converted to plain text and segmented into overlapping chunks, preserving local semantic cohesion. Chunk size and overlap were defined according to the optimal configuration identified in Experiment 1 (Section 2.1.2), which balances retrieval granularity with contextual integrity. This preprocessing step ensured that segment boundaries did not compromise sentence-level coherence, thereby improving embedding stability.Vectorization: Each chunk was embedded using OpenAI’s text-embedding-ada-002 model, producing dense vector representations in a high-dimensional semantic space. These embeddings captured contextual relationships at the subparagraph level, enabling fine-grained semantic retrieval aligned with user queries.Domain-Based Indexing: For each knowledge domain, a separate FAISS index was created using the IndexFlatIP configuration (inner product similarity). This design supports fast and exact k-nearest neighbor (k-NN) search within each semantic repository. The use of independent indexes per domain facilitates targeted retrieval and minimizes semantic noise during generation.

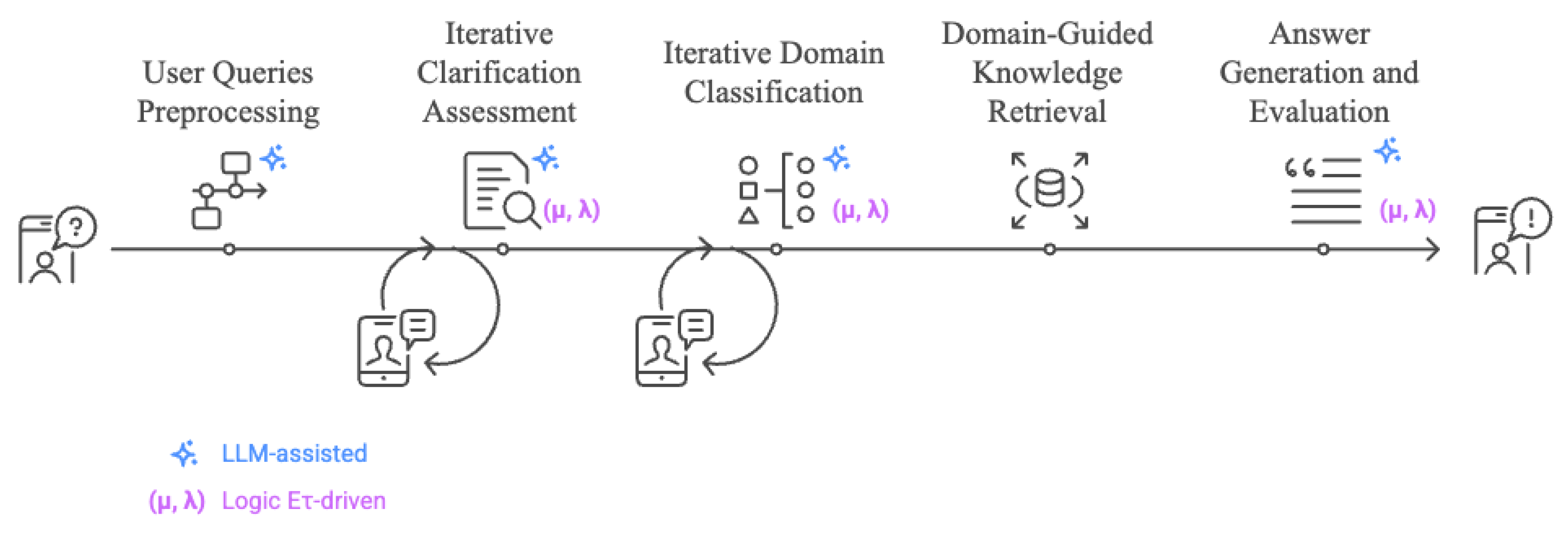

2.4.2. Reasoning Workflow of the Conversational DSS Agent (C-DSS-A)

-

User Queries Preprocessing: User queries were preprocessed before both vector-based retrieval and language model inference. The adopted preprocessing configuration reflected the outcomes of controlled experiments. Synonym expansion was enabled as the only non-trivial transformation, selected for its capacity to bridge lexical gaps between user queries and indexed content. Lemmatization and punctuation removal were also applied, given their low computational cost and consistent contribution to lexical normalization. Conversely, diacritic stripping and whitespace collapsing were turned off by default, as their empirical impact on retrieval effectiveness proved negligible.Iterative Clarification Assessment: Upon receiving a preprocessed user query, the system initiates an iterative process to evaluate and refine the clarity of the input. This is framed as the proposition:P1(μ, λ): “The user question is clear.”

- Iterative Domain Classification: Once the question is considered clear, the system prompts the LLM to classify it into one of five predefined poultry production domains: (i) housing and environmental control, (ii) animal nutrition, (iii) poultry health, (iv) husbandry practices, or (v) animal welfare. The classification is formalized as an annotated proposition:P₂(μ, λ) = “The question pertains to [identified domain]”.

- Domain-Guided Knowledge Retrieval: With a clarified question and an identified domain, the system proceeds to semantic retrieval. The input query is embedded using OpenAI’s text-embedding-ada-002 model, and a k-NN search (k = 5) is performed in a FAISS vector index (IndexFlatIP with dot-product similarity) to retrieve the most relevant content chunks. Each passage is linked to its original source and metadata.

- Answer Generation and Evaluation: The retrieved passages are concatenated with the clarified user query and submitted as the prompt context to GPT-4o (via OpenAI API). The model then generates a draft response. In parallel, it evaluates the annotated proposition:

2.4.3. Reasoning Support with Logic Eτ

2.5. Evaluation Protocol

- 4.

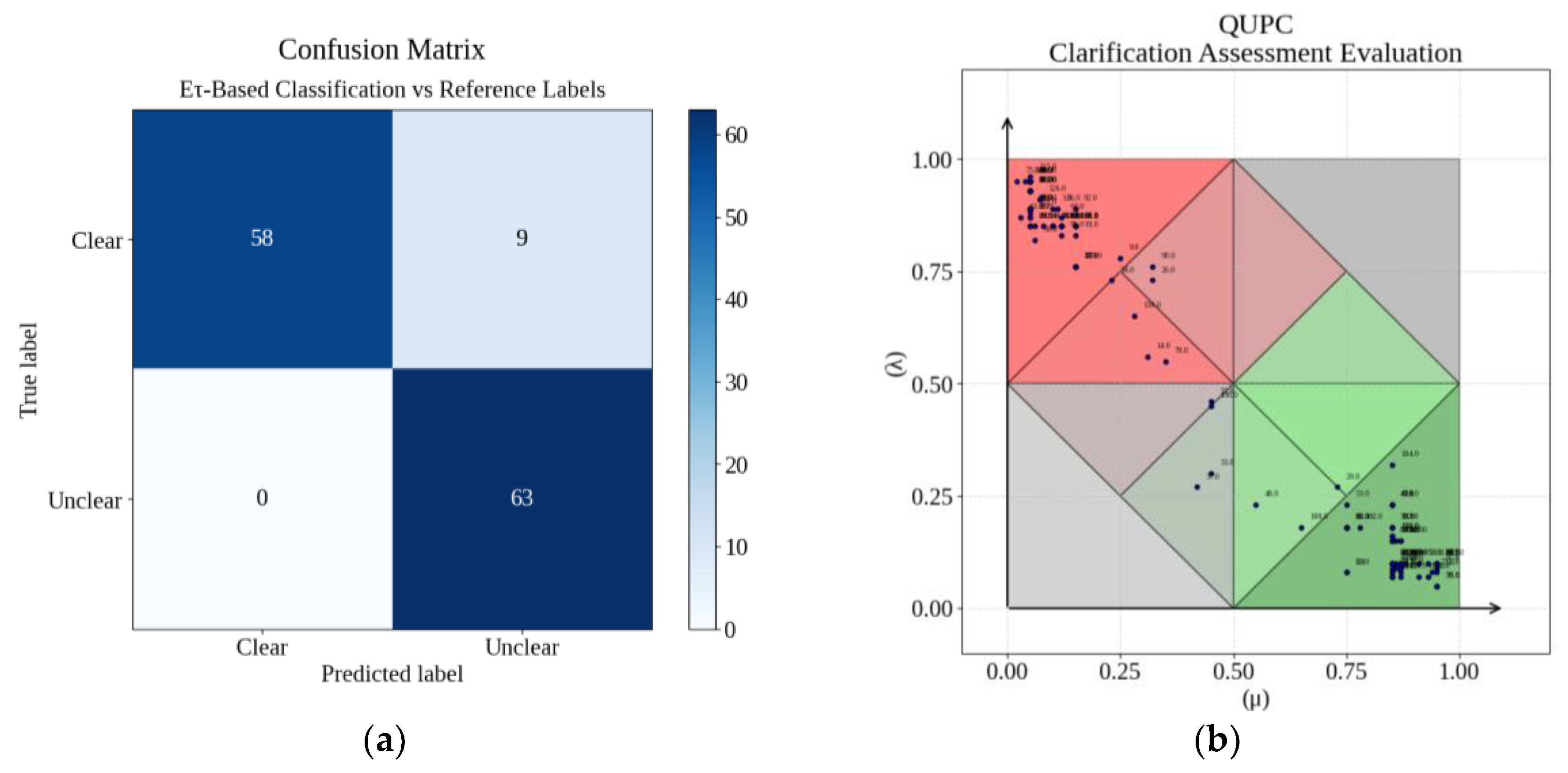

- The test of the Iterative Clarification Assessment stage used a synthetic dataset of 130 user questions, generated from the DS-KB and labeled as Clear or Unclear. Each label encompassed a gradient of linguistic phenomena, including ambiguous phrasing, underspecified referents, non-technical constructions, and malformed syntax. Manual validation ensured internal consistency and class balance. The objective was to assess the system’s ability to evaluate the proposition P₁(μ, λ): “The user question is clear”, by discriminating underdetermined inputs based on evidential clarity rather than surface features. System performance was measured by its ability to converge to the correct classification through iterative reformulation, with convergence defined as Gce(μ, λ) ≥ 0.75 for proposition P₁.

- 5.

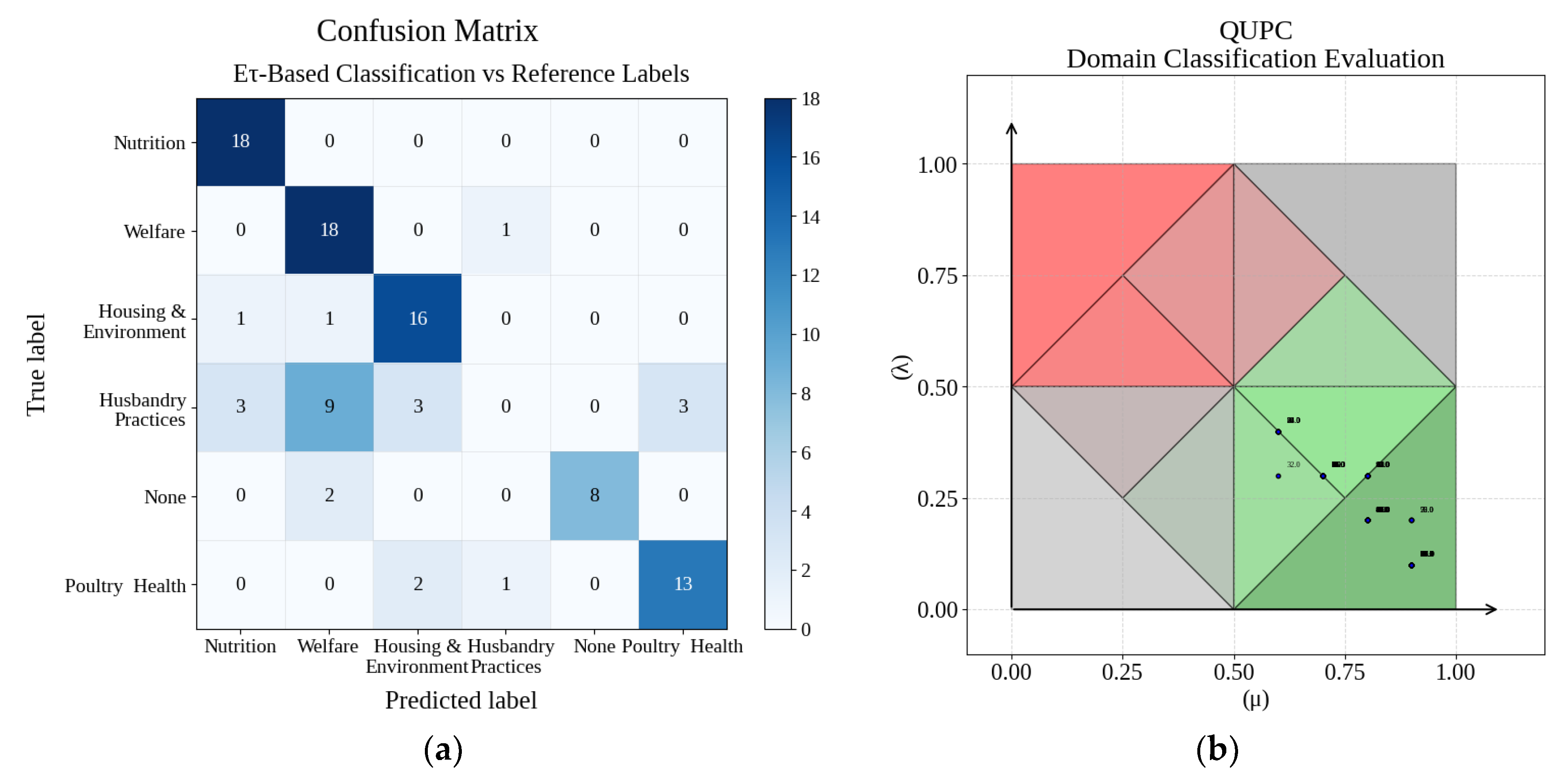

- The second test targeted the Iterative Domain Classification stage, using a new set of 100 synthetically generated questions, randomly assigned to one of the five defined domains, Housing and Environment, Animal Nutrition, Poultry Health, Husbandry Practices, Animal Welfare, or to no domain at all. This randomized distribution simulated open-query conditions. The dataset also included domainless questions to test rejection behavior under semantic uncertainty. The objective was to evaluate the system’s ability to assess the proposition P₂(μ, λ): “The question belongs to [domain]”, identifying the most appropriate category without forcing classification when evidential support was lacking. Classification was accepted only when the certainty degree satisfied Gce(μ, λ)≥0.75, ensuring evidential convergence before domain attribution.

- 6.

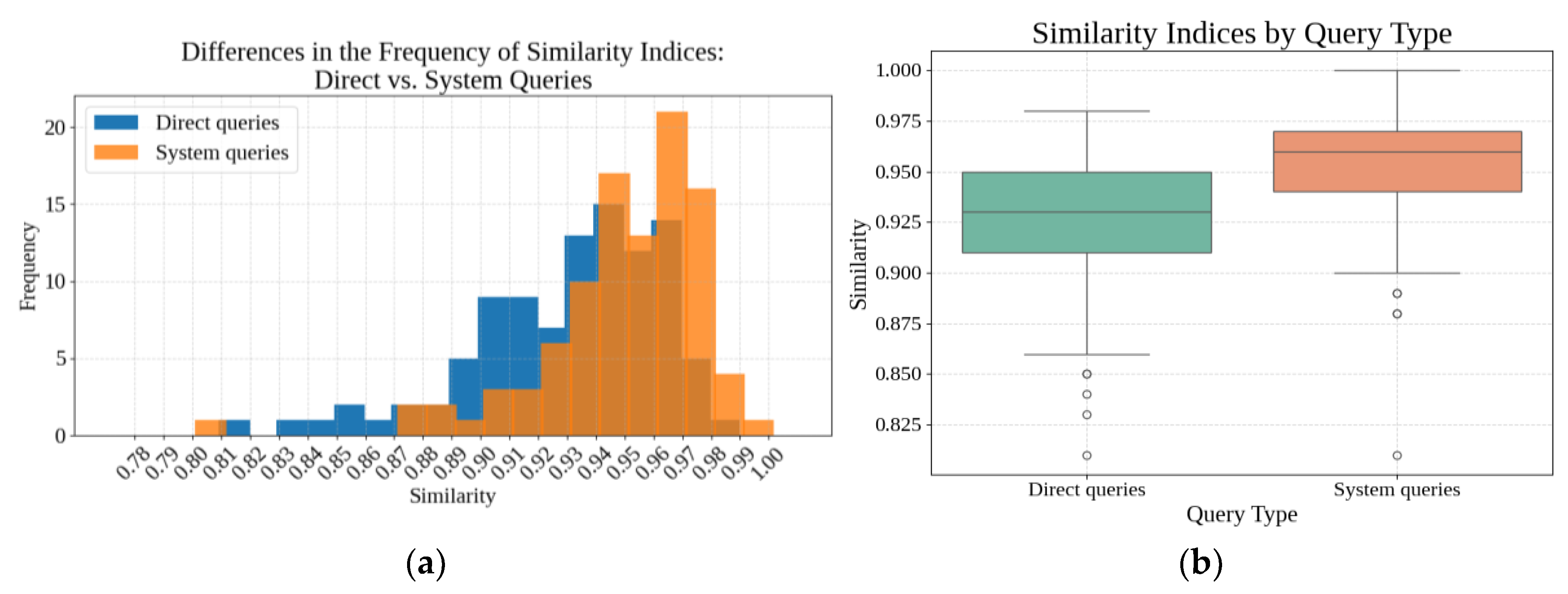

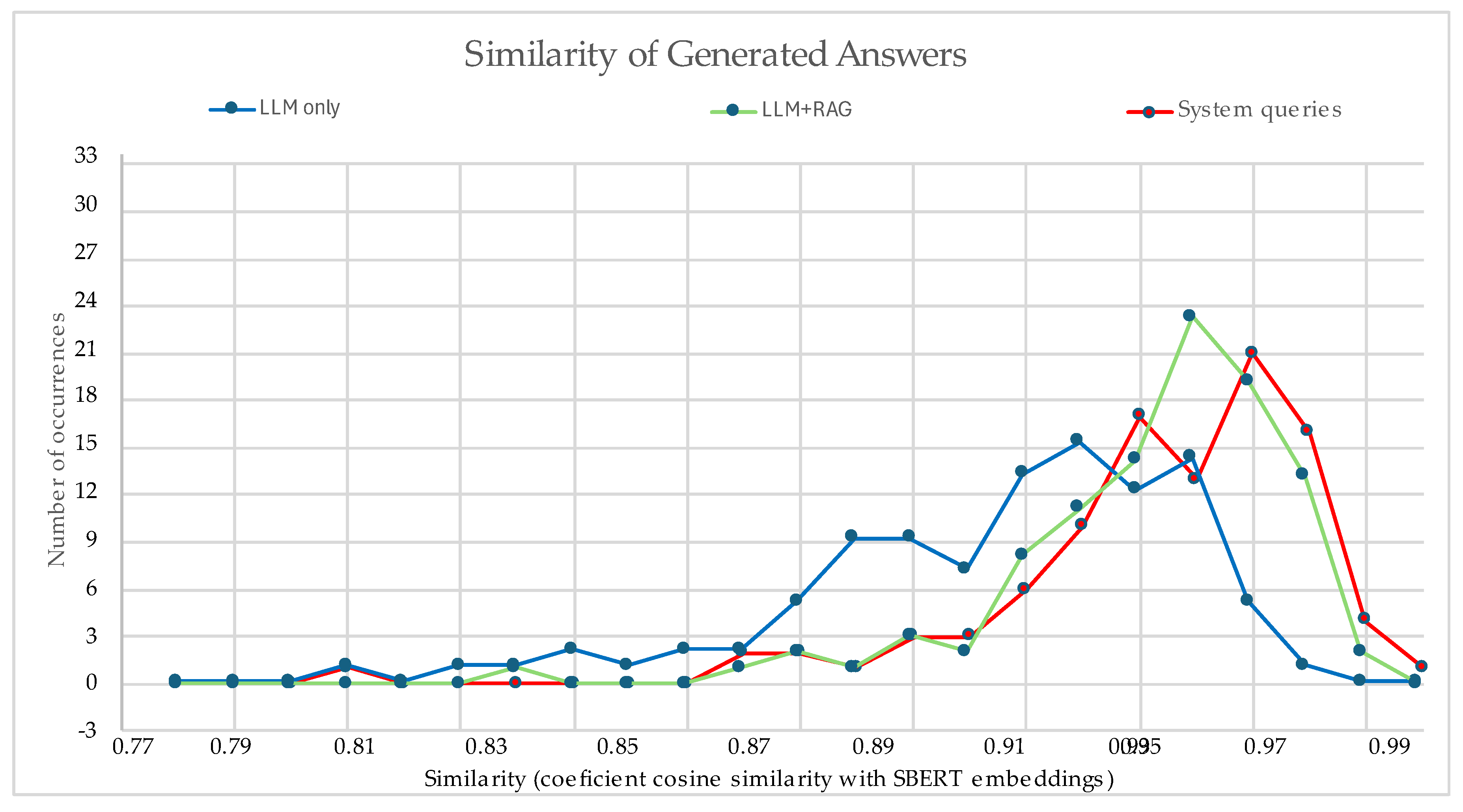

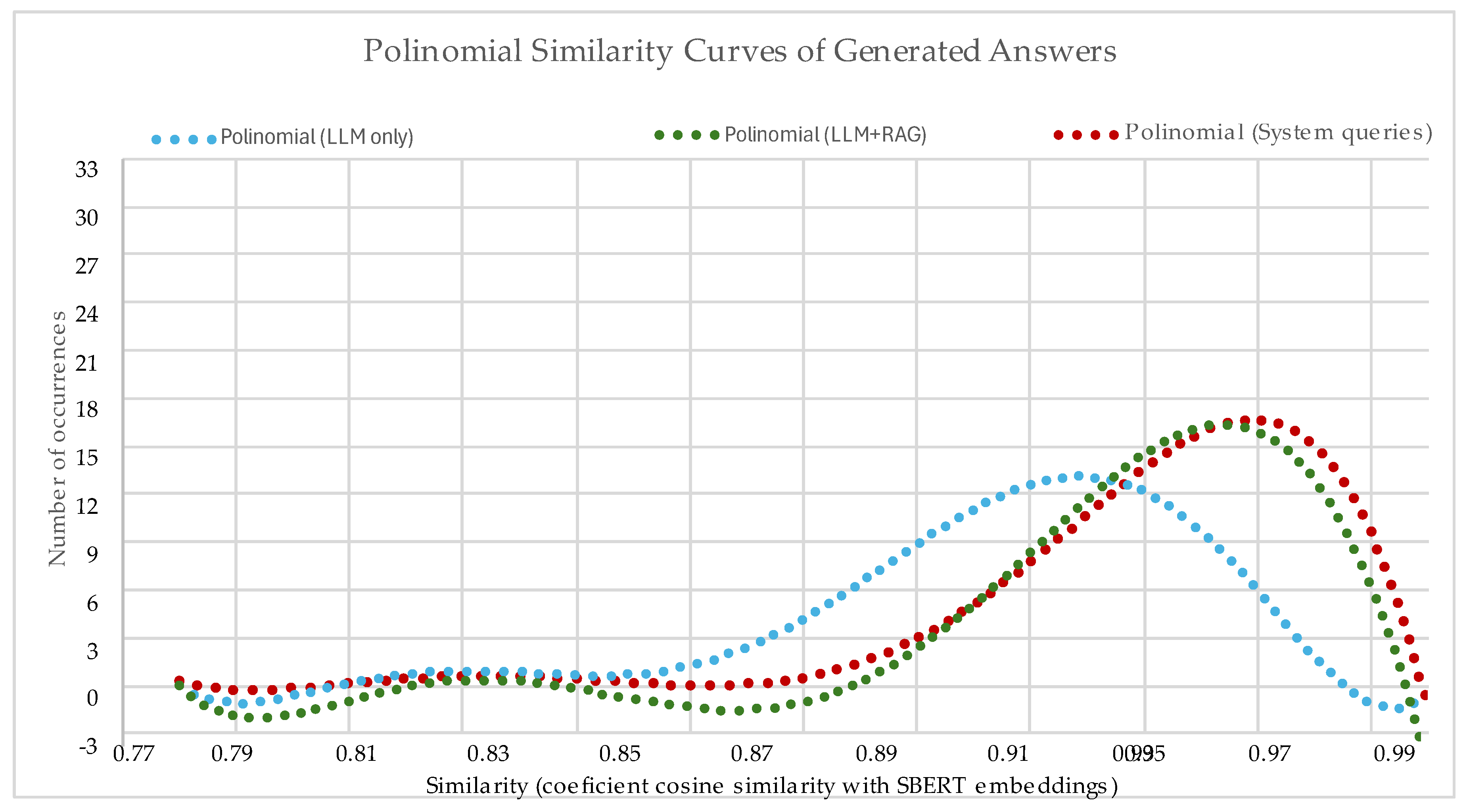

- The third test focused on the stages of Domain-Guided Knowledge Retrieval and Answer Generation and Evaluation, using 100 synthetically generated question–answer pairs curated from source articles in the DS-KB. Each question was processed under two conditions: first, through direct prompting without retrieval or evidential evaluation, and second, through the whole system workflow, which includes retrieval from the DS-KB, generative response, and Logic Eτ-based self-assessment. In the second condition, the system instructed the model to evaluate the adequacy of its answer using Logic Eτ, producing an evidential annotation for the proposition P₃(μ, λ): “The generated answer is adequate”. This annotation served as a meta-level judgment of response quality. For both conditions, the generated answers were compared to gold-standard references using semantic similarity metrics (cosine similarity with SBERT embeddings). The objective was to assess whether the evidential reasoning introduced by Logic Eτ improves the system’s capacity to generate semantically valid responses and enhances the interpretability and trustworthiness of the final output.

2.6. Reproducibility and Software Environment

- Language modeling and embedding: Openai 1.95.1 (for GPT-4o and text-embedding-ada-002), tiktoken 0.9.0 (for token counting and window control).

- Retrieval and orchestration: faiss-cpu 1.11.0 (for dense vector search using IndexFlatIP), langchain 0.3.25 and related packages (langchain-core, langchain-openai, langchain-community, langchain-text-splitters, langchain-xai, langsmith) for chaining retrieval, embedding, and generation steps.

- Text preprocessing and NLP: spaCy 3.8.7 (for lemmatization and syntactic analysis), nltk 3.9.1 (for lexical resources and linguistic tagging), including downloads: punkt, wordnet, omw-1.4, averaged_perceptron_tagger, averaged_perceptron_tagger_eng, punkt_tab.

- Data analysis and visualization: Pandas 2.3.1 (for data manipulation), scikit-learn 1.6.1 (for combinatorial evaluation routines), matplotlib 3.10.3 and seaborn 0.13.2 (for results visualization).

- Auxiliary and system tools: python-dotenv 1.1.0, requests 2.32.3, aiohttp 3.12.2, httpx 0.28.1 (for API and system orchestration), tenacity, joblib, threadpoolctl, Django 5.0.4 (web framework), djangorestframework 3.15.1 (APIs RESTful), and tqdm (for robustness, parallelization, and progress monitoring).

2.7. GenAI Disclosure

3. Results

3.1. Experimental Results

3.1.1. Effects of Chunk Size and Overlap on Retrieval Quality

3.1.2. Effects of Preprocessing on Retrieval Quality

3.1.3. Effects of Temperature and Top-p on Response Quality

3.2. Evaluation of Conversational DSS Agent Workflow Stages

3.2.1. Results for the Iterative Clarification Assessment Stage

3.2.2. Results for the Domain Classification Stage

3.2.3. Results for the Domain-Guided Knowledge Retrieval and Answer Generation and Evaluation Stages

4. Discussion

4.1. Implications of System-Level Parameter Tuning Experiments

4.2. Evidential Reasoning in Stage-Wise System Evaluations

4.3. Integrative Perspective: From Parameter Tuning to System Behavior

4.4. Limitations and Future Work

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

References

- Food balance sheets 2010–2022. Global, regional and country trends. Statistics. Available online: https://www.fao.org/statistics/highlights-archive/highlights-detail/food-balance-sheets-2010-2022-global-regional-and-country-trends/en (accessed on 9 July 2025).

- Mottet, A.; Tempio, G. Global poultry production: Current state and future outlook and challenges. World’s Poult. Sci. J. 2017, 73, 245–256. [CrossRef]

- Berckmans, D. General introduction to precision livestock farming. Anim. Front. 2017, 7, 6–11. [CrossRef]

- Gržinić, G.; Piotrowicz-Cieślak, A.; Klimkowicz-Pawlas, A.; Górny, R. L.; Ławniczek-Wałczyk, A.; Piechowicz, L.; et al. Intensive poultry farming: A review of the impact on the environment and human health. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 160014. [CrossRef]

- Hafez, H. M.; Attia, Y. A. Challenges to the poultry industry: Current perspectives and strategic future after the COVID-19 outbreak. Front. Vet. Sci. 2020, 7, 516. [CrossRef]

- Lewis, P.; Perez, E.; Piktus, A.; Petroni, F.; Karpukhin, V.; Goyal, N.; et al. Retrieval-augmented generation for knowledge-intensive NLP tasks. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2005.11401. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Su, Y.; Cai, D.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L. A survey on retrieval-augmented text generation. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.01110. [CrossRef]

- Leite, M. V.; Abe, J. M.; Souza, M. L. H.; de Alencar Nääs, I. Enhancing environmental control in broiler production: Retrieval-augmented generation for improved decision-making with large language models. AgriEng 2025, 7, 12. [CrossRef]

- Izacard, G.; Grave, E. Leveraging passage retrieval with generative models for open domain question answering. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2007.01282. [CrossRef]

- Cai, D.; Wang, Y.; Liu, L.; Shi, S. Recent advances in retrieval-augmented text generation. In Proceedings of the 45th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval (SIGIR 2022), New York, NY, USA, July 11–15, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. B.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P.; et al. Language models are few-shot learners. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2005.14165. [CrossRef]

- Ji, Z.; Lee, N.; Frieske, R.; Yu, T.; Su, D.; Xu, Y.; et al. Survey of hallucination in natural language generation. ACM Comput. Surv. 2023, 55, 248:1–248:38. [CrossRef]

- Metze, K.; Morandin-Reis, R. C.; Lorand-Metze, I.; Florindo, J. B. Bibliographic research with ChatGPT may be misleading: The problem of hallucination. J. Pediatr. Surg. 2024, 59, 158. [CrossRef]

- Abe, J. M.; Akama, S.; Nakamatsu, K. Introduction to Annotated Logics: Foundations for Paracomplete and Paraconsistent Reasoning; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2015; Vol. 88. [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, F. R. D.; Abe, J. M. A Paraconsistent Decision-Making Method; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2018; Vol. 87. [CrossRef]

- de Carvalho Junior, A.; Justo, J. F.; de Oliveira, A. M.; da Silva Filho, J. I. A comprehensive review on paraconsistent annotated evidential logic: Algorithms, applications, and perspectives. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 127, 107342. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, A.; Beed, R. S. Applications of Internet of Things in Smart Agriculture. In AI to Improve e-Governance and Eminence of Life; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp 103–115. [CrossRef]

- Abe, J. M. Remarks on Paraconsistent Annotated Evidential Logic Et. Unisanta Sci. Technol. 2014, 3, 25–29.

- Petroni, F.; Piktus, A.; Fan, A.; Lewis, P.; Yazdani, M.; Cao, N. D.; et al. KILT: A benchmark for knowledge intensive language tasks. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2009.02252. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, D.; Li, J.; Feng, Z.; Zhang, F. Entropy-optimized dynamic text segmentation and RAG-enhanced LLMs for construction engineering knowledge base. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3134. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Vuppalapati, C. Integrating retrieval-augmented generation with large language models for supply chain strategy optimization. In Applied Cognitive Computing and Artificial Intelligence; Springer: Cham, 2025; pp 475–486. [CrossRef]

- Boban, I.; Doko, A.; Gotovac, S. Sentence retrieval using stemming and lemmatization with different length of the queries. Adv. Sci. Technol. Eng. Syst. J. 2020, 5, 349–354. [CrossRef]

- Pramana, R.; Debora; Subroto, J. J.; Gunawan, A. A. S.; Anderies. Systematic literature review of stemming and lemmatization performance for sentence similarity. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 7th International Conference on Information Technology and Digital Applications (ICITDA), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, Nov 23–25, 2022; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp 1–6. [CrossRef]

- Sirisha, U.; Kumar, C.; Durgam, R.; Eswaraiah, P.; Nagamani, G. An analytical review of large language models leveraging KDGI fine-tuning, quantum embedding’s, and multimodal architectures. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2025, 83, 4031–4059. [CrossRef]

- Gabín, J.; Parapar, J. Leveraging retrieval-augmented generation for keyphrase synonym suggestion. In Advances in Information Retrieval; Springer: Cham, 2025; pp 311–327. [CrossRef]

- Chung, J.; Kamar, E.; Amershi, S. Increasing diversity while maintaining accuracy: Text data generation with large language models and human interventions. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers); Rogers, A., Boyd-Graber, J., Okazaki, N., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Toronto, Canada, July 9–14, 2023; pp 575–593. [CrossRef]

- Amin, M. M.; Schuller, B. W. On prompt sensitivity of ChatGPT in affective computing. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Affective Computing and Intelligent Interaction (ACII 2024), Glasgow, United Kingdom, 15–18 September 2024; pp 203–209. [CrossRef]

- OpenAI; Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; et al. GPT-4 technical report. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2303.08774. [CrossRef]

- Ojo, R. O.; Ajayi, A. O.; Owolabi, H. A.; Oyedele, L. O.; Akanbi, L. A. Internet of things and machine learning techniques in poultry health and welfare management: A systematic literature review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 200, 107266. [CrossRef]

- Astill, J.; Dara, R. A.; Fraser, E. D. G.; Roberts, B.; Sharif, S. Smart poultry management: Smart sensors, big data, and the internet of things. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 170, 105291. [CrossRef]

- OpenAI Platform. Models overview. Available online: https://platform.openai.com/docs/models (accessed on February 6, 2025).

- Towards Paraconsistent Engineering, Akama, S., Ed. Towards Paraconsistent Engineering; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2016. [CrossRef]

- DSSAICopilotForPoultryFarming/. Available online: https://github.com/marcusviniciusleite/DSSAICopilotForPoultryFarming/tree/main (accessed on July 23, 2025).

- Brassó, L. D.; Komlósi, I.; Várszegi, Z. Modern technologies for improving broiler production and welfare: A review. Animals 2025, 15 (4), 493. [CrossRef]

- Tareesh, M. T.; Anandhi, M.; Sujatha, G.; Thiruvenkadan, A. K. Digital twins in poultry farming: A comprehensive review of the smart farming breakthrough transforming efficiency, health, and profitability. Int. J. Vet. Sci. Anim. Husbandry 2025, 10 (8S), 89–95. [CrossRef]

- Nääs, I. A.; Garcia, R. G. The dawn of intelligent poultry science: A Brazilian vision for a global future. Braz. J. Poult. Sci. 2025, 27, eRBCA. [CrossRef]

- Baumhover, A.; Hansen, S. L. Preparing the AI-assisted animal scientist: Faculty and student perspectives on enhancing animal science education with artificial intelligence. Anim. Front. 2024, 14 (6), 54–56. [CrossRef]

- Ghavi Hossein-Zadeh, N. Artificial intelligence in veterinary and animal science: Applications, challenges, and future prospects. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2025, 235, 110395. [CrossRef]

- eFarm – Horizon OpenAgri. Available online: https://horizon-openagri.eu/open-source-catalogue/demo-efarm/ (accessed on August 31, 2025).

- farmOS. Available online: https://farmos.org/ (accessed on August 31, 2025).

- Poultry Farming Management System – Horizon OpenAgri. Available online: https://horizon-openagri.eu/open-source-catalogue/poultry-farming-management-system/ (accessed on August 31, 2025).

- Poultry Development Review. Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/i3531e/i3531e00.htm (accessed on August 31, 2025).

- Environmental guidelines for poultry rearing operations. FAOLEX. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/en/c/LEX-FAOC204579/ (accessed on August 31, 2025).

- Mellor, D. J. Operational details of the five domains model and its key applications to the assessment and management of animal welfare. Animals (Basel) 2017, 7 (8), 60. [CrossRef]

- Azad, H. K.; Deepak, A. Query expansion techniques for information retrieval: A survey. Inf. Process. Manag. 2019, 56 (5), 1698–1735. [CrossRef]

- Holtzman, A.; Buys, J.; Du, L.; Forbes, M.; Choi, Y. The curious case of neural text degeneration. arXiv 2020, arXiv:1904.09751. [CrossRef]

- Peeperkorn, M.; Kouwenhoven, T.; Brown, D.; Jordanous, A. Is temperature the creativity parameter of large language models? arXiv 2024, arXiv:2405.00492. [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Zhang, Z.; Langrené, N.; Zhu, S. Unleashing the potential of prompt engineering for large language models. Patterns 2025, 6 (6), 101260. [CrossRef]

| Symbol | State |

| V | True |

| QV→T | Quasi-true, tending to inconsistent; |

| QV→⊥ | Quasi-true, tending to paracomplete |

| F | False |

| QF→T | Quasi-false, tending to inconsistent |

| QF→⊥ | Quasi-false, tending to paracomplete |

| T | Inconsistent |

| QT→V | Quasi-inconsistent, tending to true |

| QT→F | Quasi-inconsistent, tending to false |

| ⊥ | Paracomplete or Indeterminate |

| Q⊥→V | Quasi-paracomplete, tending to true |

| Q⊥→F | Quasi-paracomplete, tending to false |

| Proposition ID | Evaluated Statement |

Purpose in System |

Threshold (Gce)* | Action if Gce< Threshold |

System Interaction Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P₁(μ, λ) | “The user question is clear.” | Assess linguistic clarity; ensure interpretability |

0.75 | Trigger clarification question; append user response |

Iterative clarification loop |

| P₂(μ, λ) | “The question pertains to [identified domain].” |

Classify query into production domain | 0.75 | Pose meta-question to user; eliminate rejected domain |

Iterative domain pruning |

| P₃(μ, λ) | “The generated answer appropriately addresses the user’s question.” |

Assess adequacy and relevance of generated response | 0.75 | Flag response as uncertain; optionally trigger regeneration |

Response flagging or regeneration |

| Precision | Recall | F1-score | Support | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clear | 1.000 | 0.866 | 0.928 | 67 |

| Unclear | 0.875 | 1.000 | 0.933 | 63 |

| Accuracy | 0.931 | 130 | ||

| Macro avg | 0.938 | 0.933 | 0.931 | 130 |

| Weighted avg | 0.939 | 0.931 | 0.931 | 130 |

| Precision | Recall | F1-score | Support | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Animal Nutrition | 0.818 | 1.000 | 0.900 | 18 |

| Animal Welfare | 0.600 | 0.947 | 0.735 | 19 |

| Housing and Environment | 0.762 | 0.889 | 0.821 | 18 |

| Poultry Health | 0.813 | 0.813 | 0.813 | 16 |

| Out-of-scope queries 2 | 1.000 | 0.800 | 0.889 | 10 |

| Accuracy | 0.737 | 99 | ||

| Macro avg | 0.665 | 0.741 | 0.693 | 99 |

| Weighted avg | 0.635 | 0.737 | 0.675 | 99 |

| User Query |

Generated Answer (excerpt) |

Evidential Judgment |

User-Facing Message |

|---|---|---|---|

| What is the recommended broiler diet for heat stress? | Conflicting guidelines were retrieved, some emphasizing increased electrolytes, others focusing on energy adjustment | μ = 0.61, λ = 0.12 Gce = 0.49 (Inadequate) |

“Some retrieved information appears inconsistent. The answer may need clarification. Please consider refining your query or reviewing the supporting evidence.” |

| What is the optimal temperature for broiler housing at 21 days of age? | Broilers at 21 days should be kept at 28 °C; some sources also mention 24–26 °C depending on ventilation |

μ = 0.64, λ = 0.39 Gce = 0.25 (Inadequate) |

“Retrieved guidelines vary across sources. Please consider reviewing the suggested ranges or providing more context for your query.” |

| How often should litter be replaced in broiler houses? | Some sources recommend complete replacement each cycle, others suggest partial reuse if treated with drying agents |

μ = 0.78, λ = 0.17 Gce = 0.61 (Inadequate) |

“The retrieved evidence shows differing recommendations. The answer may depend on farm conditions—please review the supporting guidelines.” |

| Is vaccination against coccidiosis always required in broilers? | Most sources recommend vaccination for long-cycle broilers; some mention prophylaxis may suffice under high biosecurity. | μ = 0.62, λ = 0.14 Gce = 0.48 (Inadequate) |

“Evidence for this query is partly inconsistent. The system combined both vaccination and prophylaxis approaches—please interpret according to your production context” |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).