Submitted:

12 December 2025

Posted:

16 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Carbon Dots (CDs)

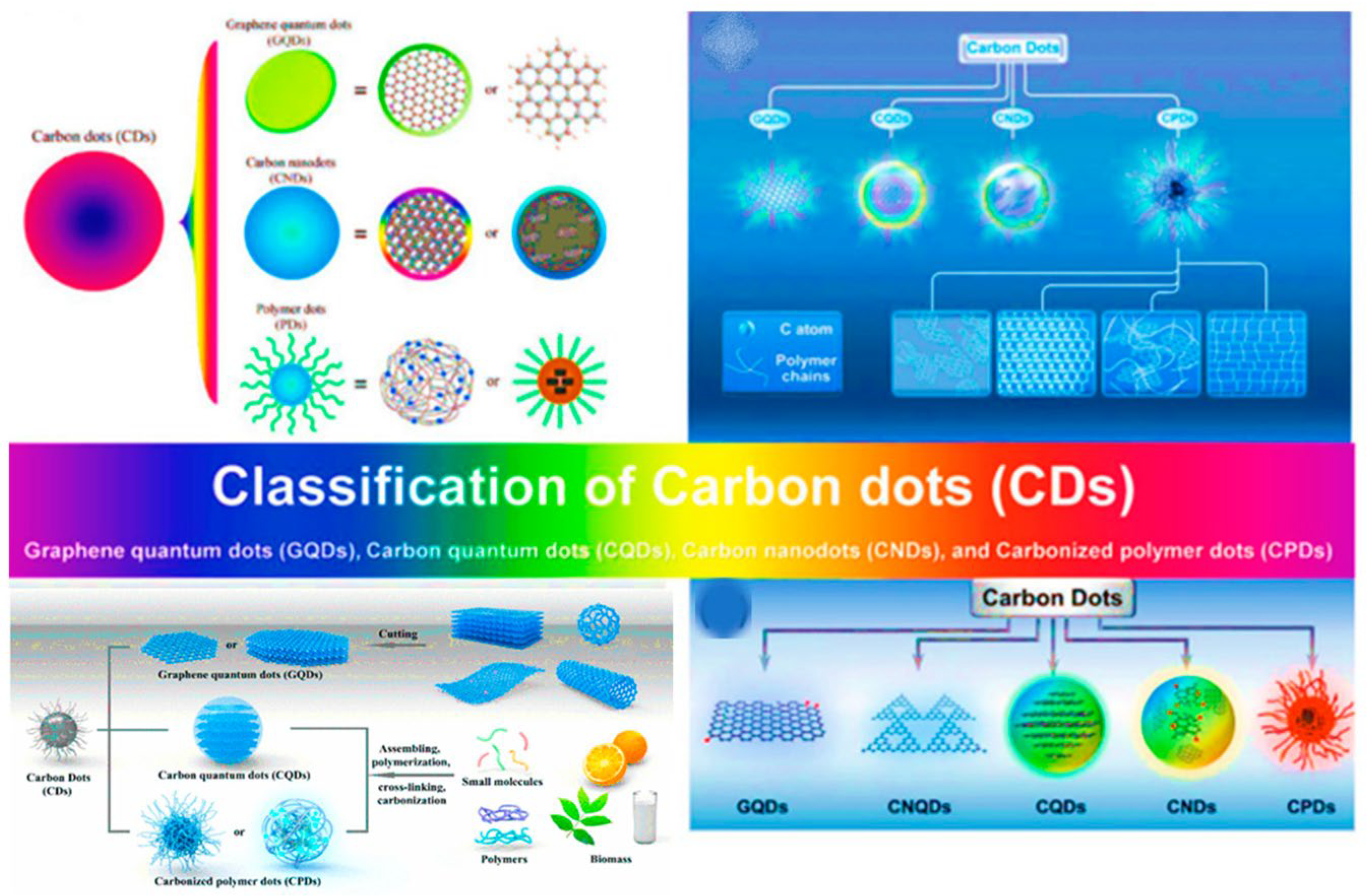

2.1. Classification, Characterization, and Properties of CDs

2.2. CD Synthesis Approaches

2.3. Biomedical Applications of CDs

2.3.1. Drug, Vaccine, and Gene Therapy

2.3.2. Bioimaging

2.3.3. Biosensing

2.3.4. Nanomedicine and Therapeutic Activity

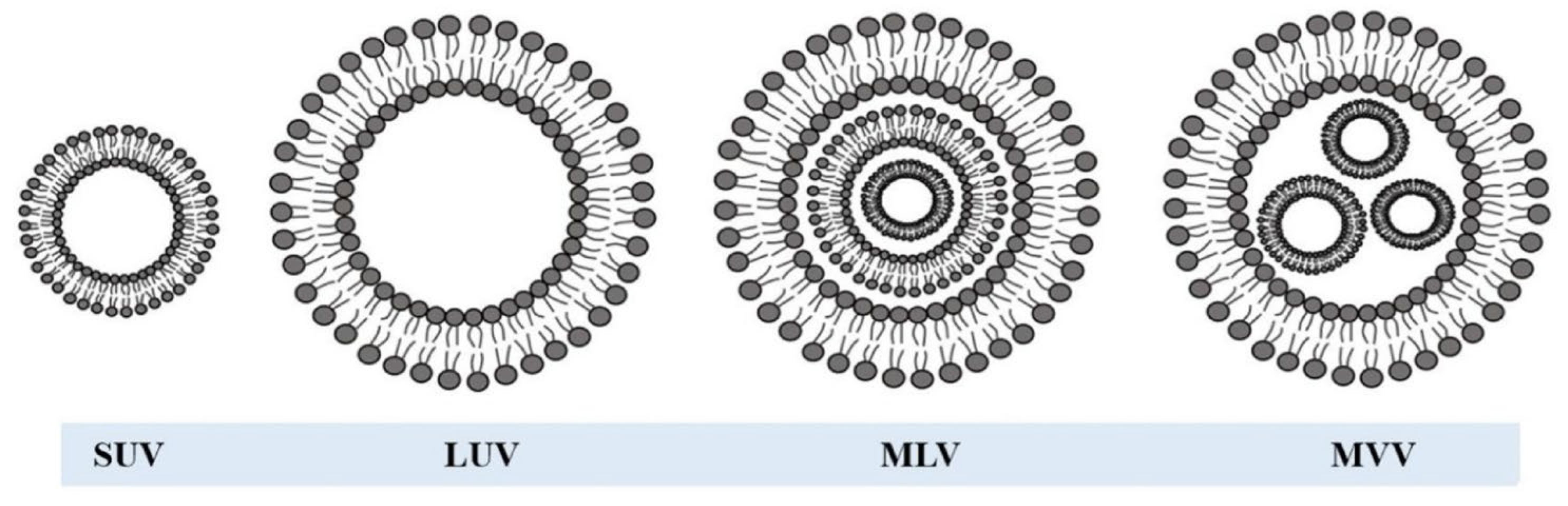

3. The Model Membrane System (Phospholipid Vesicles or Liposomes)

4. Carbon Dots and The Model Membrane Systems

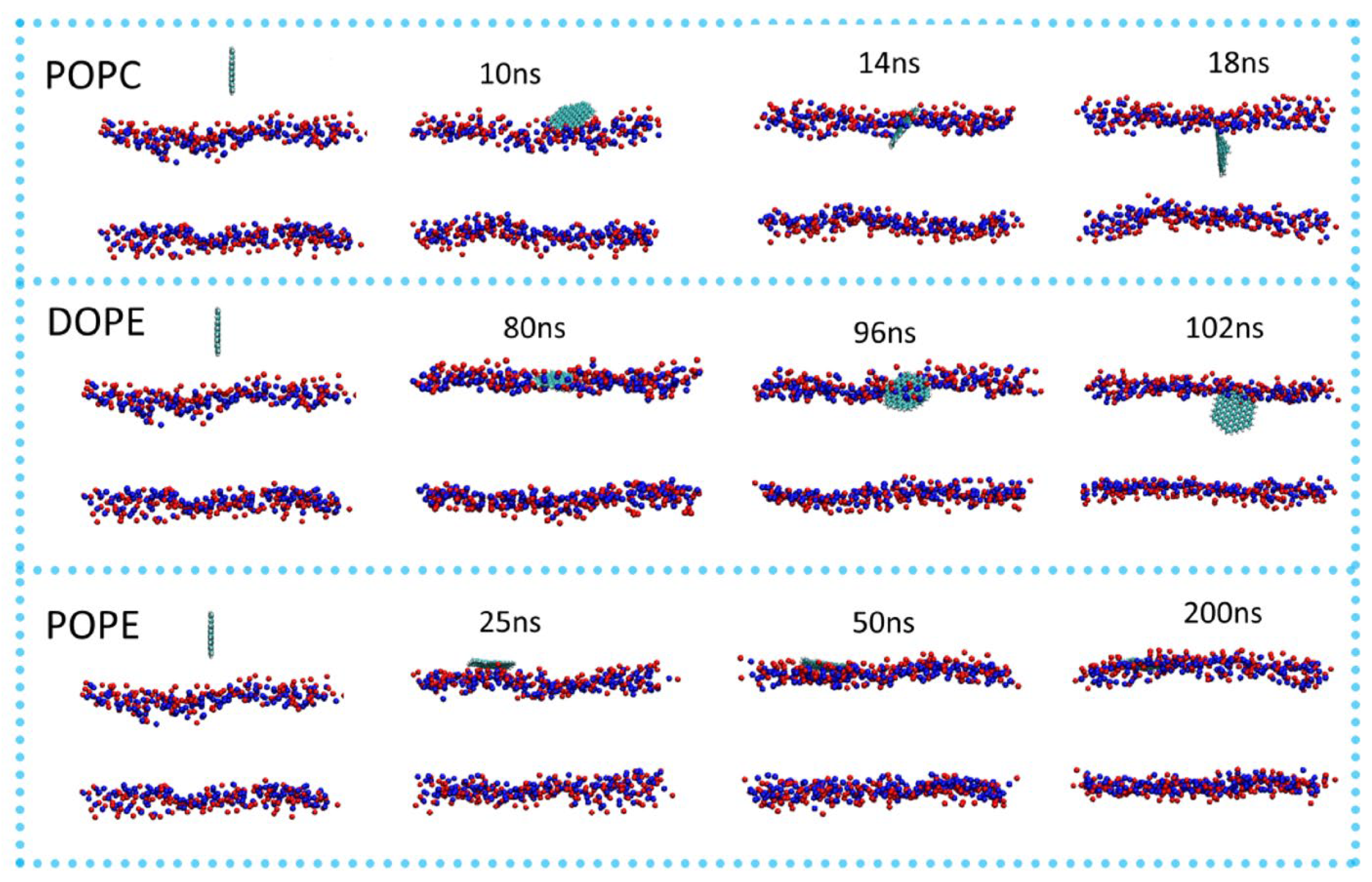

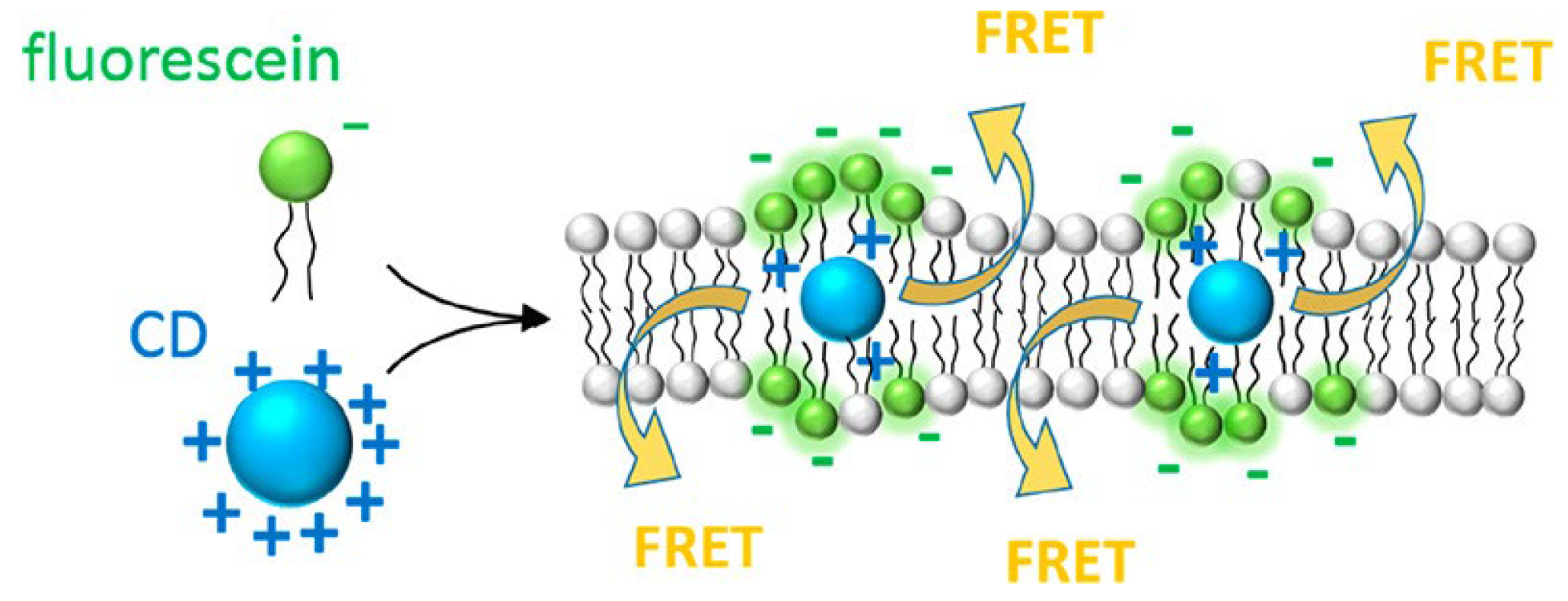

4.1. Interactions of the CDs with the Model Membrane System

4.1.1. Factors Affecting the Interactions of the CDs with the Model Membrane System

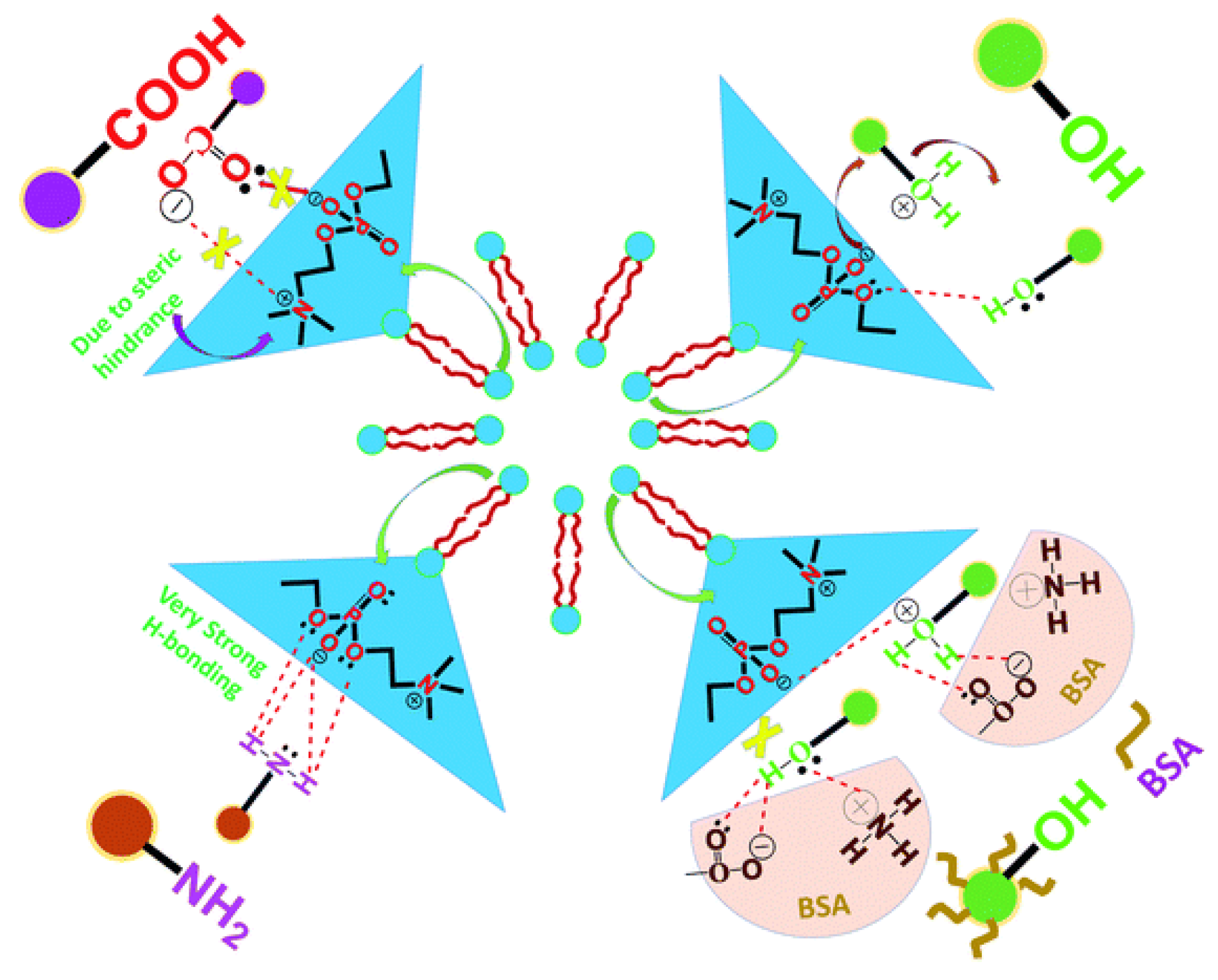

4.1.1. A. Surface Chemistry

4.1.1. B Isomerism of CDs

4.2. CD-Model Membrane Hybrid System

5. Conclusions and Future Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CDs | Carbon Dots |

| GQDs | Graphene Quantum Dots |

| CQDs | Carbon Quantum Dots |

| CNDs | Carbon Nanodots |

| CPDs | Carbonized Polymer Dots |

| MDs | Molecular Dynamics |

| BBB | Blood-brain barrier |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| PDT | Photodynamic Therapy |

| PTT | Photothermal Therapy |

| SUV | Small unilamellar vesicles |

| LUV | Large unilamellar vesicles |

| MLV | Multilamellar vesicles |

| MVV | Multivesicular vesicles |

| POPC | 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine |

| DOPE | 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine |

| POPE | 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl phosphatidylethanolamine |

| POPC | 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine |

| DPPC | 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine |

| DMPC | 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine |

References

- Omar, N.A.S.; Fen, Y.W.; Irmawati, R.; Hashim, H.S.; Ramdzan, N.S.M.; Fauzi, N.I.M. A Review on Carbon Dots: Synthesis, Characterization and Its Application in Optical Sensor for Environmental Monitoring. Nanomaterials 2022, 12, 2365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, S. Carbon Dots (CDs): Basics, Recent Potential Biomedical Applications, Challenges, and Future Perspectives. J Nanopart Res 2023, 25, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mkhari, O.; Ntuli, T.D.; Coville, N.J.; Nxumalo, E.N.; Maubane-Nkadimeng, M.S. Supported Carbon-Dots: A Review. Journal of Luminescence 2023, 255, 119552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.-T.; Wang, L.-N.; Xu, J.; Huang, K.-J.; Wu, X. Synthesis and Modification of Carbon Dots for Advanced Biosensing Application. Analyst 2021, 146, 4418–4435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luchini, A.; Vitiello, G. Mimicking the Mammalian Plasma Membrane: An Overview of Lipid Membrane Models for Biophysical Studies. Biomimetics (Basel) 2020, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

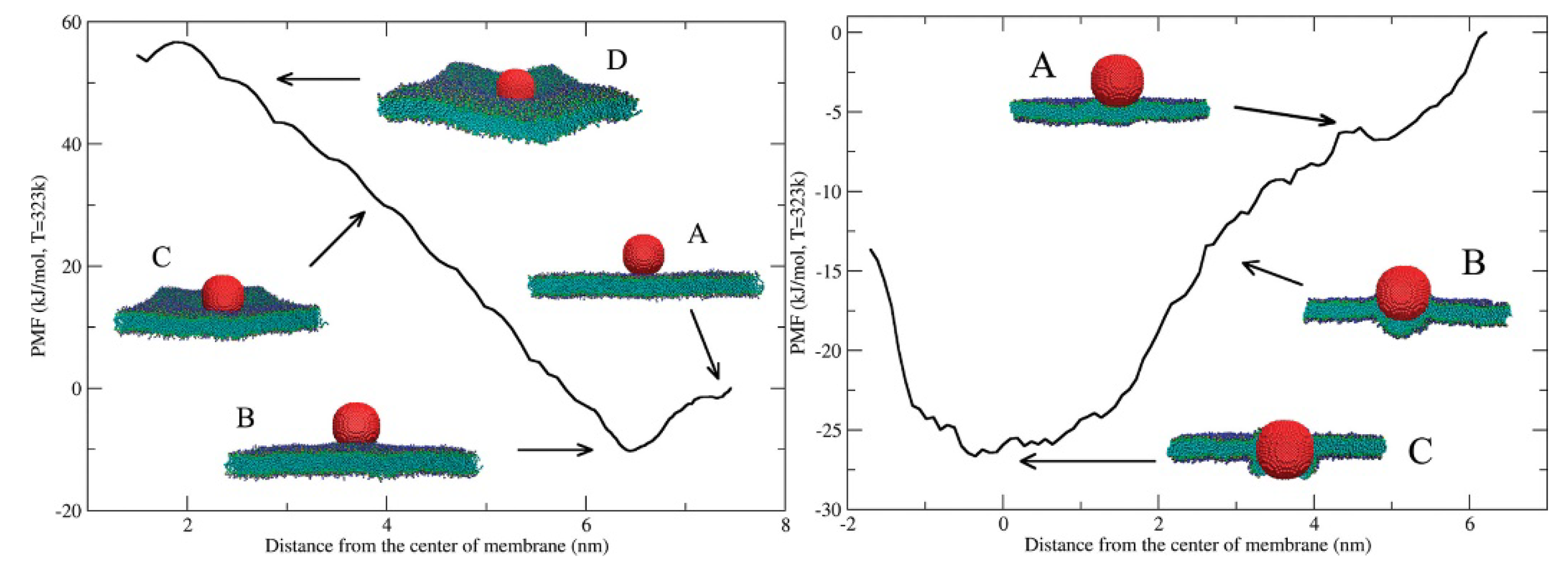

- Zhang, P.; Jiao, F.; Wu, L.; Kong, Z.; Hu, W.; Liang, L.; Zhang, Y. Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Transport Mechanism of Graphene Quantum Dots through Different Cell Membranes. Membranes 2022, 12, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

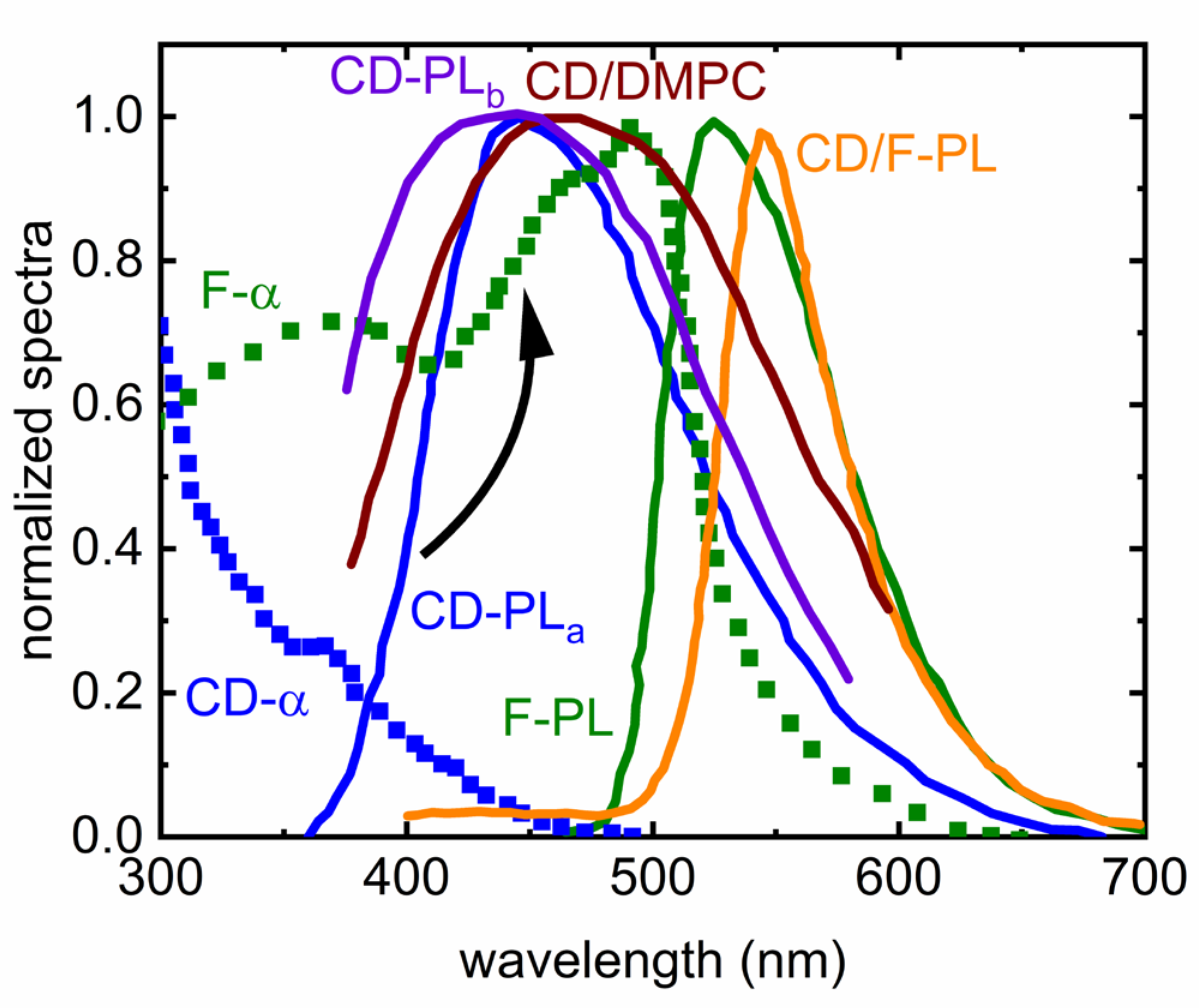

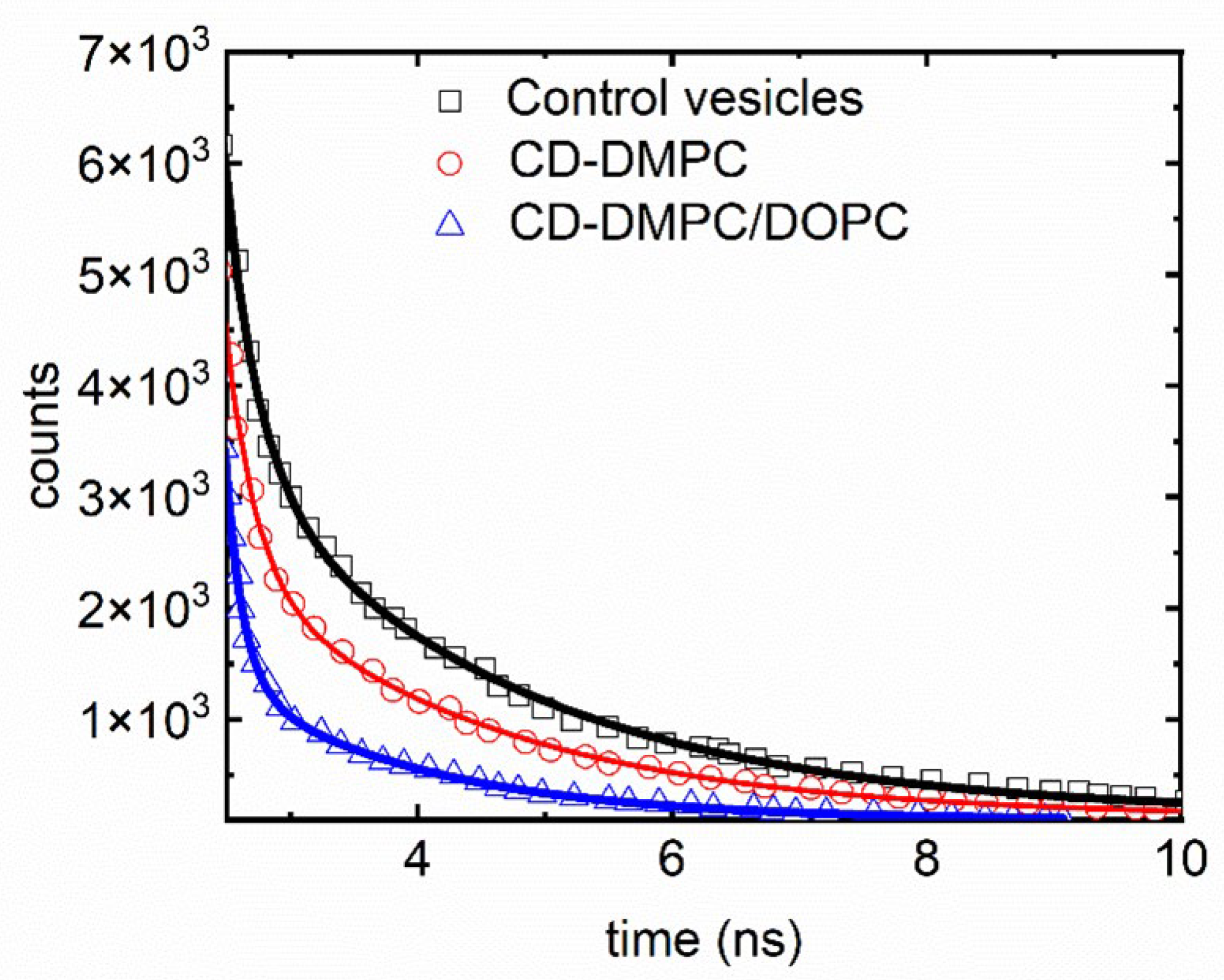

- Nandi, S.; Malishev, R.; Bhunia, S.K.; Kolusheva, S.; Jopp, J.; Jelinek, R. Lipid-Bilayer Dynamics Probed by a Carbon Dot-Phospholipid Conjugate. Biophysical journal 2016, 110, 2016–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- S. Boruah, J.; Sankaranarayanan, K.; Chowdhury, D. Insight into Carbon Quantum Dot–Vesicles Interactions: Role of Functional Groups. RSC Advances 2022, 12, 4382–4394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavroidi, B.; Kaminari, A.; Sakellis, E.; Sideratou, Z.; Tsiourvas, D. Carbon Dots–Biomembrane Interactions and Their Implications for Cellular Drug Delivery. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2023, 16, 833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, B.; Moghimianavval, H.; Hwang, S.-W.; Liu, A.P. Synthetic Cell as a Platform for Understanding Membrane-Membrane Interactions. Membranes 2021, 11, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botet-Carreras, A.; Montero, M.T.; Sot, J.; Domènech, Ò.; Borrell, J.H. Engineering and Development of Model Lipid Membranes Mimicking the HeLa Cell Membrane. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2021, 630, 127663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trebesch, N.; Hasdemir, H.S.; Chen, T.; Wen, P.-C.; Tajkhorshid, E. Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Biological Membranes and Membrane-Associated Phenomena across Scales. Current Opinion in Structural Biology 2025, 93, 103071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Chen, X.; Gu, N. Computational Investigation of Interaction between Nanoparticles and Membranes: Hydrophobic/Hydrophilic Effect. J. Phys. Chem. B 2008, 112, 16647–16653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

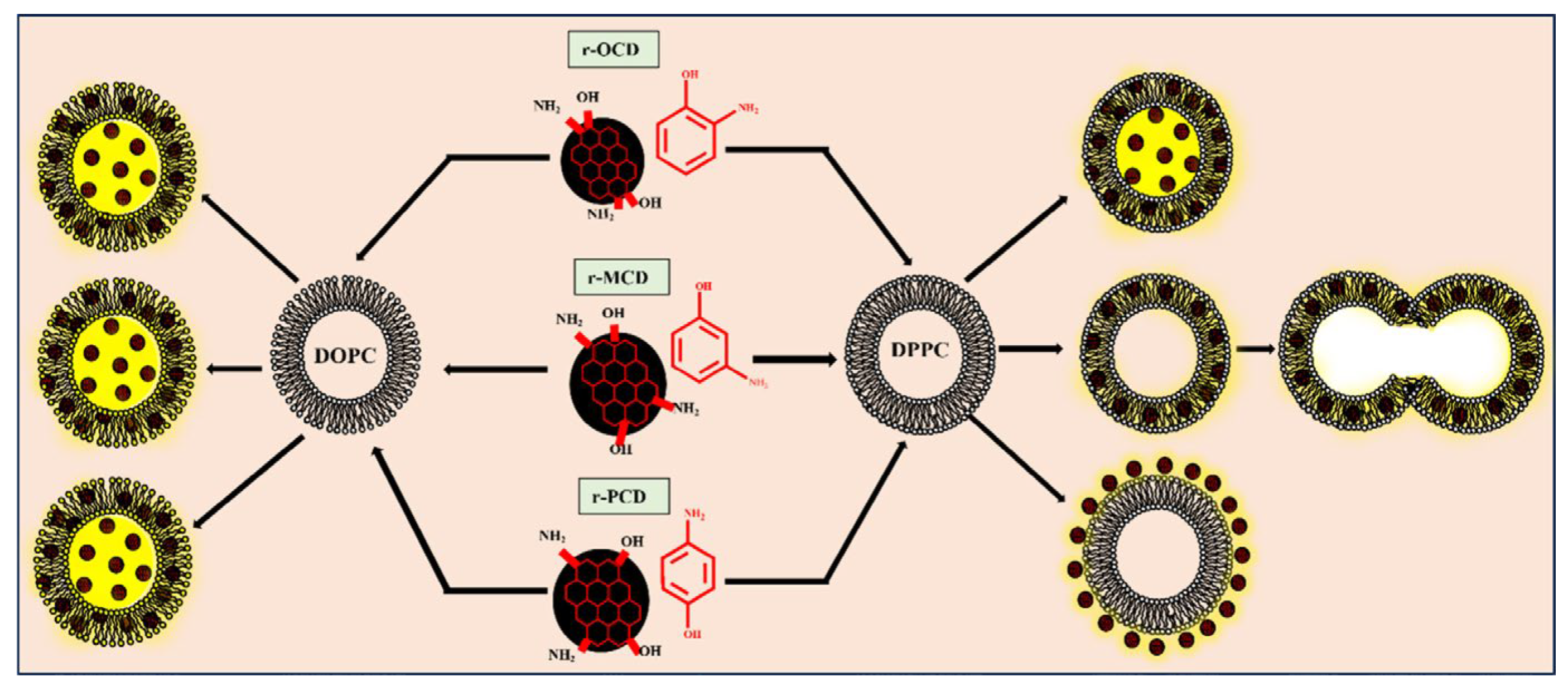

- Kumar, N.; Choudhury, S.; Nath, P.; Tabassum, H.; Bagchi, D.; Maity, A.; Chakraborty, A. Unraveling the Fluidity-Dependent Interactions of Isomeric Reduced Carbon Dots with Lipid Membranes for Bioimaging: A Multifaceted Spectroscopic and Microscopic Investigation. Langmuir 2025, 41, 23990–24003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

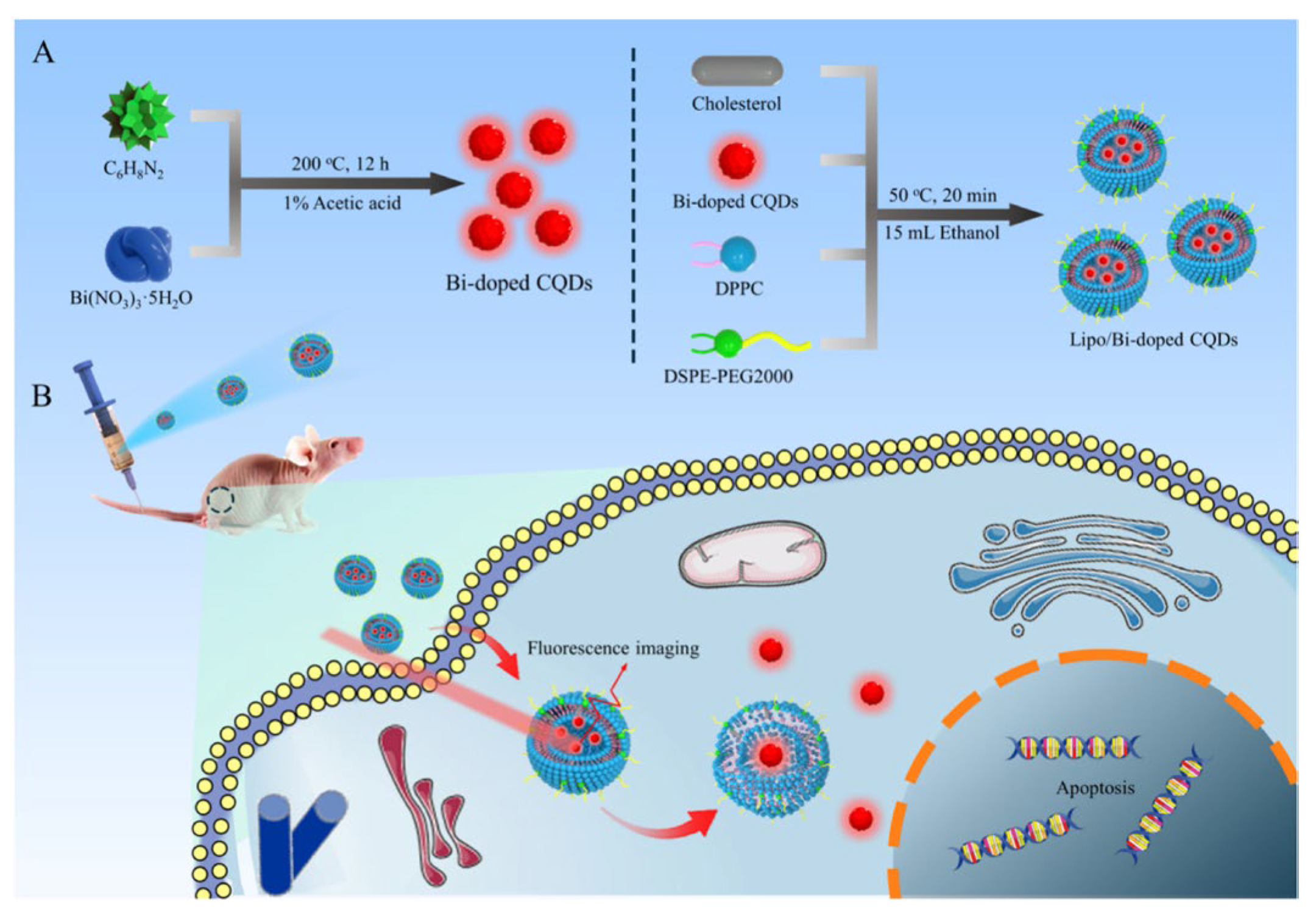

- Zhu, P.; Liu, Y.; Tang, Y.; Zhu, S.; Liu, X.; Yin, L.; Liu, Q.; Yu, Z.; Xu, Q.; Luo, D.; et al. Bi-Doped Carbon Quantum Dots Functionalized Liposomes with Fluorescence Visualization Imaging for Tumor Diagnosis and Treatment. Chinese Chemical Letters 2024, 35, 108689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

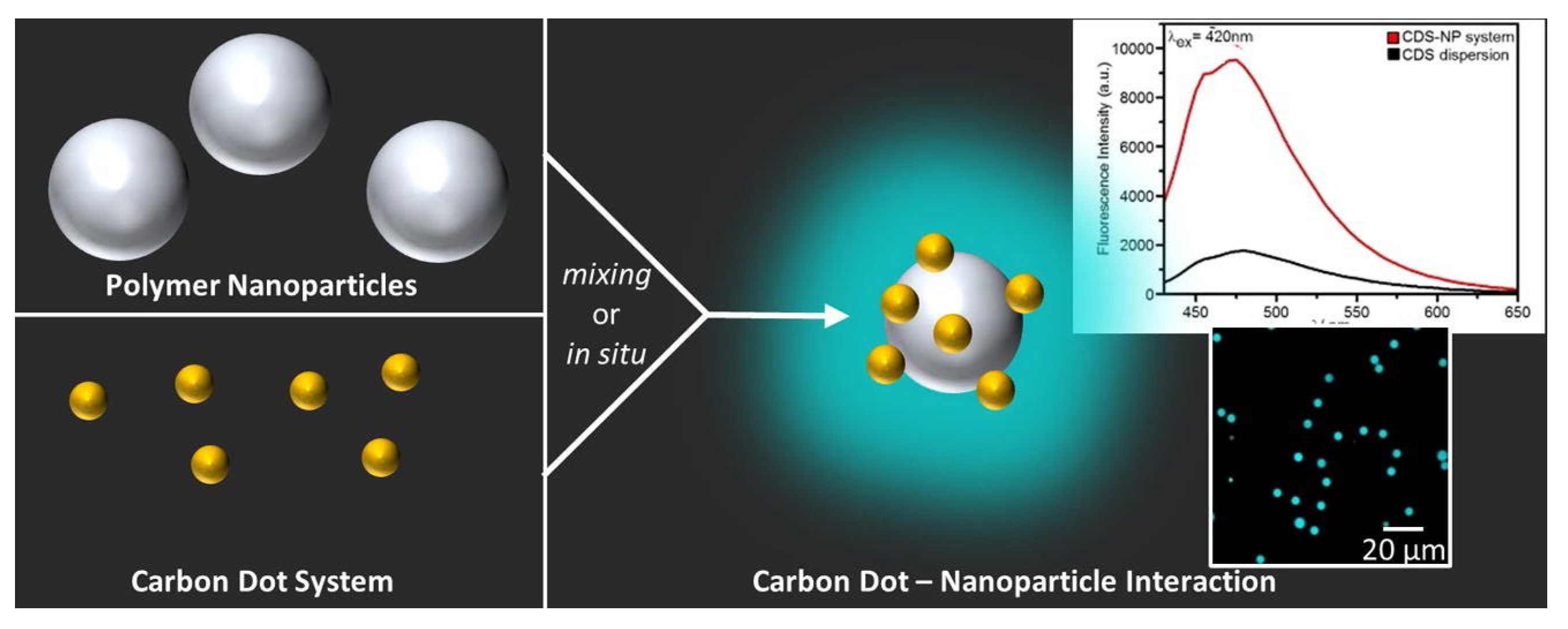

- Momper, R.; Steinbrecher, J.; Dorn, M.; Rörich, I.; Bretschneider, S.; Tonigold, M.; Ramanan, C.; Ritz, S.; Mailänder, V.; Landfester, K.; et al. Enhanced Photoluminescence Properties of a Carbon Dot System through Surface Interaction with Polymeric Nanoparticles. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science 2018, 518, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

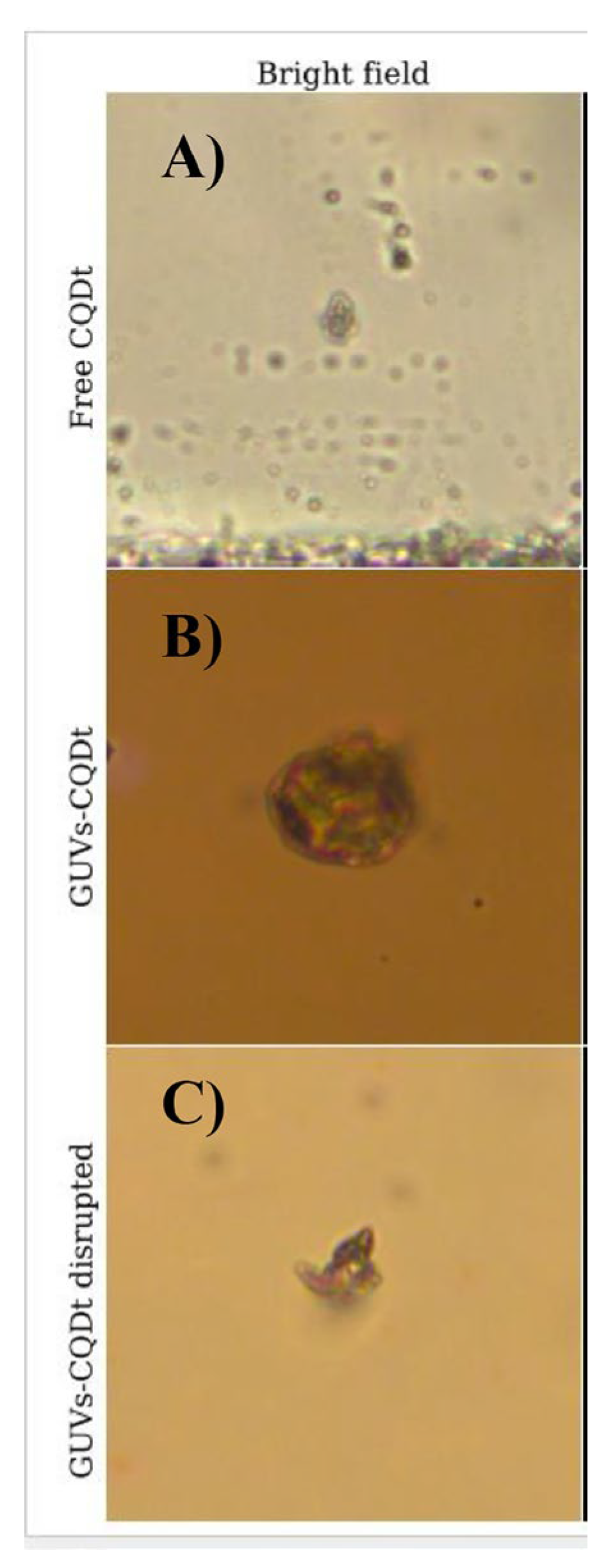

- Guzmán-López, J.E.; Pérez-Isidoro, R.; Amado-Briseño, M.A.; Lopez, I.; Villareal-Chiu, J.F.; Sánchez-Cervantes, E.M.; Vázquez-García, R.A.; Espinosa-Roa, A. Facile One-Pot Electrochemical Synthesis and Encapsulation of Carbon Quantum Dots in GUVs. Chemical physics impact 2024, 8, 100519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

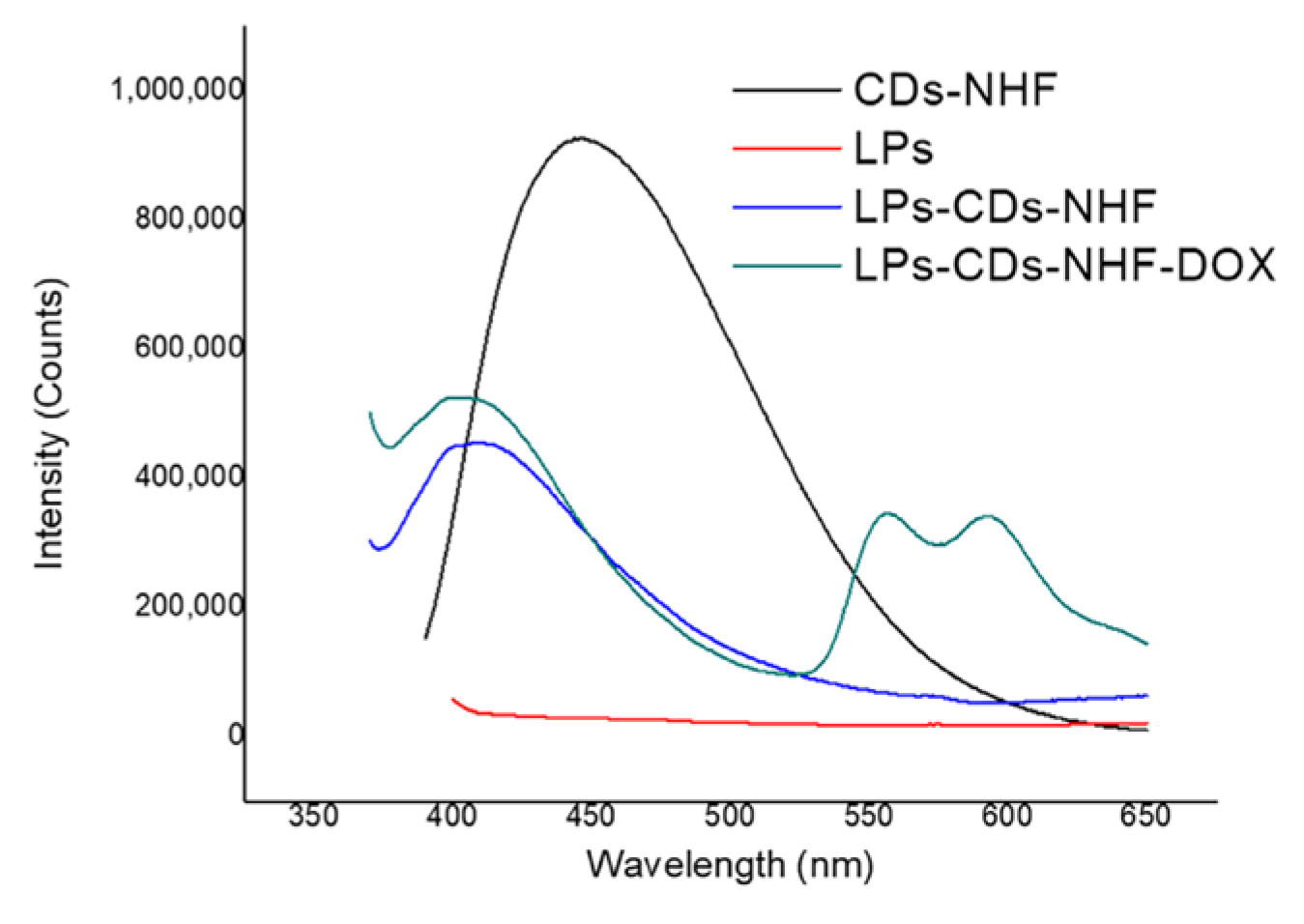

- Corina-Lenuta, L.; Cristian, P.; Stan, C.S.; Gabriel, L.; Tiron, C.E.; Mariana, P.; Aleksander, F.; Bogdan, S.; Constanta, I.; Adrian, T.; et al. Carbon Dot-Enhanced Doxorubicin Liposomes: A Dual-Functional Nanoplatform for Cancer Therapy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 7535–7556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pritzl, S.D.; Pschunder, F.; Ehrat, F.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Lohmüller, T.; Huergo, M.A.; Feldmann, J. Trans-Membrane Fluorescence Enhancement by Carbon Dots: Ionic Interactions and Energy Transfer. Nano Lett. 2019, 19, 3886–3891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

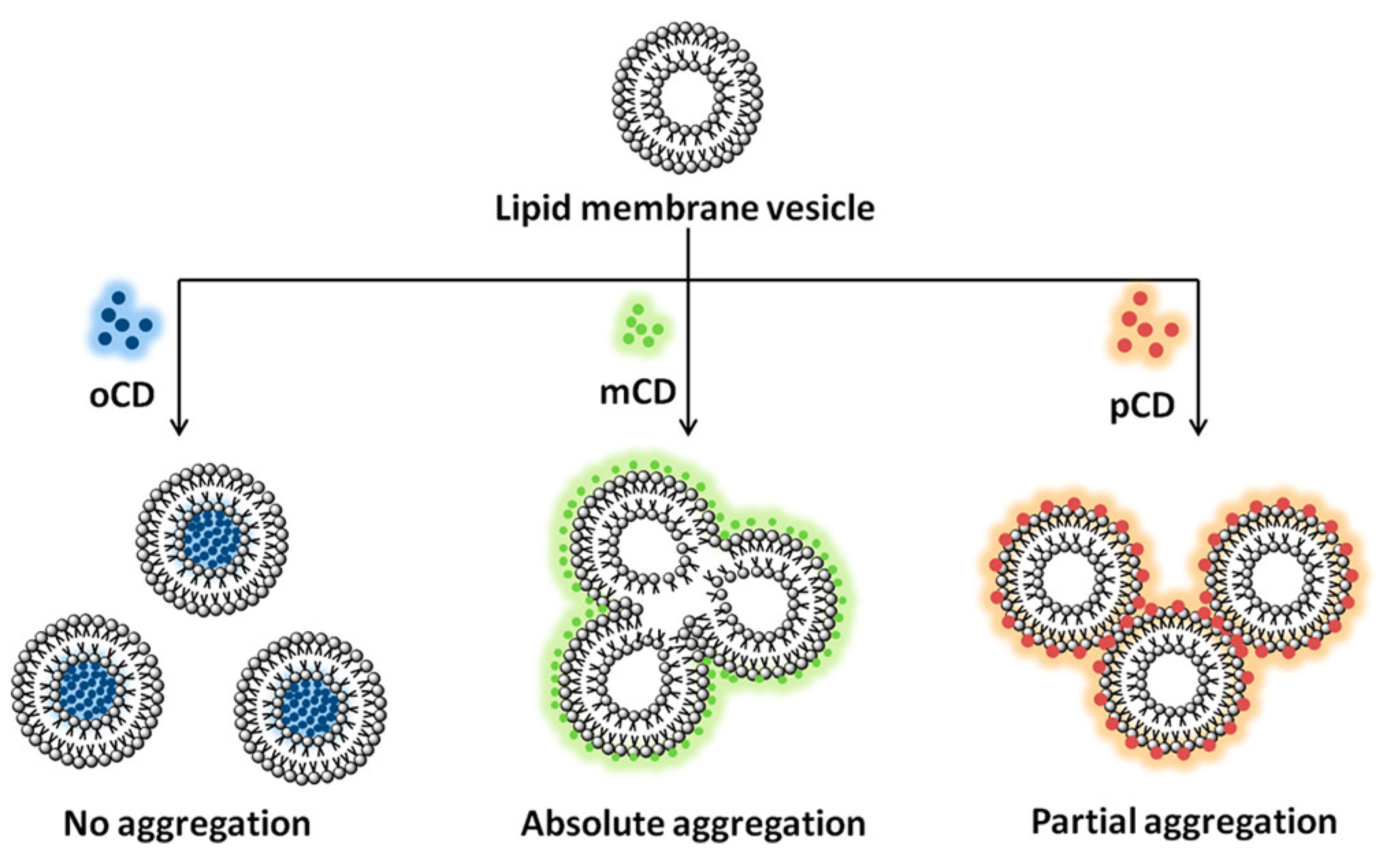

- Kanwa, N.; M, K.; Chakraborty, A. Discriminatory Interaction Behavior of Lipid Vesicles toward Diversely Emissive Carbon Dots Synthesized from Ortho, Meta, and Para Isomeric Carbon Precursors. Langmuir 2020, 36, 10628–10637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etefa, H.F.; Tessema, A.A.; Dejene, F.B. Carbon Dots for Future Prospects: Synthesis, Characterizations and Recent Applications: A Review (2019–2023). C 2024, 10, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, A.; Hong, S.; Ju, H. Carbon Quantum Dots: Synthesis, Characteristics, and Quenching as Biocompatible Fluorescent Probes. Biosensors 2025, 15, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaurav, H.; Verma, D.; Bansal, A.; Kapoor, D.N.; Sheth, S. Progress in Drug Delivery and Diagnostic Applications of Carbon Dots: A Systematic Review. Front. Chem. 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansuriya, B.D.; Altintas, Z. Carbon Dots: Classification, Properties, Synthesis, Characterization, and Applications in Health Care—An Updated Review (2018–2021). Nanomaterials (Basel) 2021, 11, 2525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehtesabi, H.; Hallaji, Z.; Najafi Nobar, S.; Bagheri, Z. Carbon Dots with pH-Responsive Fluorescence: A Review on Synthesis and Cell Biological Applications. Microchim Acta 2020, 187, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faghihi, H.; Mozafari, M.R.; Bumrungpert, A.; Parsaei, H.; Taheri, S.V.; Mardani, P.; Dehkharghani, F.M.; Pudza, M.Y.; Alavi, M. Prospects and Challenges of Synergistic Effect of Fluorescent Carbon Dots, Liposomes and Nanoliposomes for Theragnostic Applications. Photodiagnosis and Photodynamic Therapy 2023, 42, 103614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tirusew, T.; Endale, M.; Zhao, D.; Liu, Y.; Chen, X.; Ahrum, B.; Kim, J.; Chang, Y.; Lee, G.H. Surface Modification, Toxicity, and Applications of Carbon Dots to Cancer Theranosis: A Review. Nanomaterials 2025, 15, 781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Tao, S.; Yang, B. The Classification of Carbon Dots and the Relationship between Synthesis Methods and Properties. Chin. J. Chem. 2023, 41, 2206–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Ren, X.; Sun, M.; Liu, H.; Xia, L. Carbon Dots: Synthesis, Properties and Applications. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 3419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, D.K.; V, P.; Si, S.; Panigrahi, H.; Mishra, S. Carbon Dots and Their Polymeric Nanocomposites: Insight into Their Synthesis, Photoluminescence Mechanisms, and Recent Trends in Sensing Applications. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 11050–11080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbon Dots: A New Type of Carbon-Based Nanomaterial with Wide Applications | ACS Central Science. Available online: https://pubs-acs-org.proxy.lib.miamioh.edu/doi/10.1021/acscentsci.0c01306 (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Koutsogiannis, P.; Thomou, E.; Stamatis, H.; Gournis, D.; Rudolf, P. Advances in Fluorescent Carbon Dots for Biomedical Applications. Advances in Physics X 2020, 5, 1758592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y. Advances in Carbon Dot-Based Ratiometric Fluorescent Probes for Environmental Contaminant Detection: A Review. Micromachines 2024, 15, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorns, M.; Pappas, D. A Review of Fluorescent Carbon Dots, Their Synthesis, Physical and Chemical Characteristics, and Applications. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paloncýová, M.; Langer, M.; Otyepka, M. Structural Dynamics of Carbon Dots in Water and N,N-Dimethylformamide Probed by All-Atom Molecular Dynamics Simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2018, 14, 2076–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, B.K.; Singh, V.V.; Solanki, M.K.; Kumar, A.; Ruokolainen, J.; Kesari, K.K. Smart Nanomaterials in Cancer Theranostics: Challenges and Opportunities. ACS Omega 2023, 8, 14290–14320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Razzaghi, M.; Ghorbanpoor, H.; Ebrahimi, A.; Avci, H.; Akbari, M.; Hassan, S. Carbon Dots in Drug Delivery and Therapeutic Applications. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2025, 224, 115644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Cai, H.; Waterhouse, G.I.N.; Qu, X.; Yang, B.; Lu, S. Carbon Dots in Bioimaging, Biosensing and Therapeutics: A Comprehensive Review. Small Science 2022, 2, 2200012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lv, R.; Li, G.; Lu, S.; Wang, T. Synthesis of Multi-Functional Carbon Quantum Dots for Targeted Antitumor Therapy. J Fluoresc 2021, 31, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutrim, E.S.M.; Vale, A.A.M.; Manzani, D.; Barud, H.S.; Rodríguez-Castellón, E.; Santos, A.P.S.A.; Alcântara, A.C.S. Preparation, Characterization and in Vitro Anticancer Performance of Nanoconjugate Based on Carbon Quantum Dots and 5-Fluorouracil. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2021, 120, 111781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliwal, S.; Jana, P.; Singh, S.; Madhyastha, H.; Webster, T.J.; Dev, A. Folic Acid Conjugated Capecitabine Capped Green Synthesized Fluorescent Carbon Dots as a Targeted Nano-Delivery System for Colorectal Cancer. Materials Today Communications 2022, 33, 104590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Ghosh, A.K.; Chowdhury, M.; Das, P.K. Folic Acid-Functionalized Carbon Dot-Enabled Starvation Therapy in Synergism with Paclitaxel against Breast Cancer. ACS Appl Bio Mater 2022, 5, 2389–2402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Peng, Z.; Dallman, J.; Baker, J.; Othman, A.M.; Blackwelder, P.L.; Leblanc, R.M. Crossing the Blood-Brain-Barrier with Transferrin Conjugated Carbon Dots: A Zebrafish Model Study. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces 2016, 145, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Strickland, S.; Jorns, M.; Fourroux, L.; Heyd, L.; Pappas, D. Cancer Cell Targeting Via Selective Transferrin Receptor Labeling Using Protein-Derived Carbon Dots. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 2707–2718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, L.M.T.; Gul, A.R.; Le, T.N.; Kim, M.W.; Kailasa, S.K.; Oh, K.T.; Park, T.J. One-Pot Synthesis of Carbon Dots with Intrinsic Folic Acid for Synergistic Imaging-Guided Photothermal Therapy of Prostate Cancer Cells. Biomater. Sci. 2019, 7, 5187–5196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Lin, Z.; Yu, Y.-X.; Jiang, B.-P.; Shen, X.-C. Multifunctional Hyaluronic Acid-Derived Carbon Dots for Self-Targeted Imaging-Guided Photodynamic Therapy. J Mater Chem B 2018, 6, 6534–6543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.-J.; Zhang, J.; Liu, Y.-H.; Luo, T.-Y.; He, X.; Yu, X.-Q. Hyaluronic Acid-Based Carbon Dots for Efficient Gene Delivery and Cell Imaging. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 15613–15624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benner, D.; Yadav, P.; Bhatia, D. Red Emitting Carbon Dots: Surface Modifications and Bioapplications. Nanoscale Adv. 2023, 5, 4337–4353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Li, W.; Chen, J.; Huang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Shu, W.; Lei, B.; Zhang, H. Antibacterial Activity and Synergetic Mechanism of Carbon Dots against Gram-Positive and -Negative Bacteria. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021, 4, 6937–6945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoval, A.; Markus, A.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, X.; Cazelles, R.; Willner, I.; Mandel, Y. Anti-VEGF-Aptamer Modified C-Dots-A Hybrid Nanocomposite for Topical Treatment of Ocular Vascular Disorders. Small 2019, 15, e1902776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hettiarachchi, S.D.; Graham, R.M.; Mintz, K.J.; Zhou, Y.; Vanni, S.; Peng, Z.; Leblanc, R.M. Triple Conjugated Carbon Dots as a Nano-Drug Delivery Model for Glioblastoma Brain Tumors. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 6192–6205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Li, B.; Ashraf, U.; Li, Q.; Lu, X.; Gao, X.; Cui, M.; Imran, M.; Ye, J.; Cao, F.; et al. Quaternized Cationic Carbon Dots as Antigen Delivery Systems for Improving Humoral and Cellular Immune Responses. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 9449–9461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.K.; Wongso, V.; Sambudi, N.S. Isnaeni Biowaste-Derived Carbon Dots/Hydroxyapatite Nanocomposite as Drug Delivery Vehicle for Acetaminophen. J Sol-Gel Sci Technol 2020, 93, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, K.; Wu, A.; Lin, H. Toward High-Efficient Red Emissive Carbon Dots: Facile Preparation, Unique Properties, and Applications as Multifunctional Theranostic Agents. Chem. Mater. 2016, 28, 8659–8668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enriquez, B.U.M.; Rangel-Ayala, M.; Kumar, Y.; Garcia, J.E.; Gomez-Aguilar, J.F.; Khandual, S.; Agarwal, V. Multifunctional Arthrospira Platensis Biomass Derived Carbon Dots: Sensing/Removal of Heavy Metal Ions, High-Power Light-Emitting Devices, and Some Machine Learning Assisted Approaches for Solid State Sensor. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2025, 13, 117827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, M.; Bhowmick, M. Needle Tip Tracking through Photoluminescence for Minimally Invasive Surgery. Biosensors (Basel) 2024, 14, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, X.; Sun, Y.; Guo, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, K.; Xiao, L.; Qu, L.; Li, Z. Fluorescent Carbon Dots for in Situ Monitoring of Lysosomal ATP Levels. Anal. Chem. 2020, 92, 7940–7946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.; Chen, M.; Hu, N.; Hu, Y.; Chen, R.; Lyu, Y.; Guo, W.; Li, L.; Liu, Y. Carbon Dots-Based Dual-Emission Ratiometric Fluorescence Sensor for Dopamine Detection. Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 2020, 243, 118804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsipur, M.; Molaei, K.; Molaabasi, F.; Alipour, M.; Alizadeh, N.; Hosseinkhani, S.; Hosseini, M. Facile Preparation and Characterization of New Green Emitting Carbon Dots for Sensitive and Selective off/on Detection of Fe3+ Ion and Ascorbic Acid in Water and Urine Samples and Intracellular Imaging in Living Cells. Talanta 2018, 183, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, R.; Chen, B.; Li, F.; Weng, S.; Zheng, Z.; Chen, M.; Wu, W.; Lin, X.; Yang, C. Positive Carbon Dots with Dual Roles of Nanoquencher and Reference Signal for the Ratiometric Fluorescence Sensing of DNA. Sensors and Actuators B: Chemical 2018, 264, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, H.O.; Salehnia, F.; Hosseini, M.; Hassan, R.; Faizullah, A.; Ganjali, M.R. Fluorescence Immunoassay Based on Nitrogen Doped Carbon Dots for the Detection of Human Nuclear Matrix Protein NMP22 as Biomarker for Early Stage Diagnosis of Bladder Cancer. Microchemical Journal 2020, 157, 104966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, D.; Zhuo, Y.; Feng, Y.; Yang, X. Employing Carbon Dots Modified with Vancomycin for Assaying Gram-Positive Bacteria like Staphylococcus Aureus. Biosens Bioelectron 2015, 74, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Citric Acid Based Carbon Dots with Amine Type Stabilizers: pH-Specific Luminescence and Quantum Yield Characteristics | The Journal of Physical Chemistry C. Available online: https://pubs-acs-org.proxy.lib.miamioh.edu/doi/10.1021/acs.jpcc.9b11732 (accessed on 3 November 2025).

- Ghirardello, M.; Ramos-Soriano, J.; Galan, M.C. Carbon Dots as an Emergent Class of Antimicrobial Agents. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inbaraj, J.J.; Nusair, N.A.; Lorigan, G.A. Investigating Magnetically Aligned Phospholipid Bilayers with EPR Spectroscopy at Q-Band (35 GHz): Optimization and Comparison with X-Band (9 GHz). Journal of Magnetic Resonance 2004, 171, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, P.C.; Tiburu, E.K.; Nusair, N.A.; Lorigan, G.A. Calculating Order Parameter Profiles Utilizing Magnetically Aligned Phospholipid Bilayers for 2H Solid-State NMR Studies. Solid State Nuclear Magnetic Resonance 2003, 24, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nusair, N.A.; Lorigan, G.A. Investigating the Structural and Dynamic Properties of n-Doxylstearic Acid in Magnetically-Aligned Phospholipid Bilayers by X-Band EPR Spectroscopy. Chemistry and Physics of Lipids 2005, 133, 151–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nusair, N.A.; Tiburu, E.K.; Dave, P.C.; Lorigan, G.A. Investigating Fatty Acids Inserted into Magnetically Aligned Phospholipid Bilayers Using EPR and Solid-State NMR Spectroscopy. Journal of Magnetic Resonance 2004, 168, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dave, P.C.; Nusair, N.A.; Inbaraj, J.J.; Lorigan, G.A. Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Studies of Magnetically Aligned Phospholipid Bilayers Utilizing a Phospholipid Spin Label: The Effect of Cholesterol. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Biomembranes 2005, 1714, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chelliah, R.; Rubab, M.; Vijayalakshmi, S.; Karuvelan, M.; Barathikannan, K.; Oh, D.-H. Liposomes for Drug Delivery: Classification, Therapeutic Applications, and Limitations. Next Nanotechnology 2025, 8, 100209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Teng, W.; Cao, J.; Wang, J. Liposomes as Delivery System for Applications in Meat Products. Foods 2022, 11, 3017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peetla, C.; Stine, A.; Labhasetwar, V. Biophysical Interactions with Model Lipid Membranes: Applications in Drug Discovery and Drug Delivery. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2009, 6, 1264–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nusair, N.; Bhowmick, M.; Huff, E.; Davies, E.; Schlabach, A.; Renaud, J.; Eversole, L. Abstract 2763 Interaction and Integration of Carbon Dot Nanoparticles Into Phospholipid Bilayers: A Step Toward Advanced Drug Delivery Systems. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2025, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.C.; Chen, L.Q.; Zhan, L.; Huang, C.Z.; Huang, J. Amino-Functionalized Carbon Dots Disrupt Lipid Metabolism to Impair Zebrafish Embryogenesis. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2025, 496, 139497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).