Introduction

The escalating climate crisis is no longer a distant problem, which is evident by the rising global temperatures, biodiversity loss, and extreme weather conditions. Technological innovations and new policies are crucial, but not effective enough without behavioural change (Strefler et al., 2024). Everyday decisions around the utilization of resources come from our values, emotions, and sense of responsibility toward nature. Researchers now stress the importance of individual psychology, empathy, and culture in shaping how society responds to these decisions (McCaffery et al., 2025).

The field of Environmental Psychology emphasizes that, beyond knowledge and awareness, intrinsic values, emotional connection to nature, and empathy for the non-human world have emerged as key drivers of pro-environmental behavior (Bouman & Steg, 2019; Tam, 2022). Individuals with higher biospheric and altruistic values are more likely to take part in conservation, support environmental policies, and live sustainably (Bouman & Steg, 2021; Wang et al., 2021). Recent neuroscientific evidence further supports this link, showing that empathic concern for nature involves both affective and cognitive processing, reflecting how individuals emotionally and intellectually engage with environmental distress (Sahni et al., 2024). These factors can be different across cultures, highlighting the need for cross-cultural studies. Assessing these aspects in conjunction can help researchers understand why people choose to act in environmentally responsible ways.

In the Indian cultural context, ecological values and empathy for nature have deep historical roots. Ancient philosophies such as Advaita Vedanta and traditions like Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam (“the world is one family”) embody interconnectedness with all living beings (Kar, 2023; Long, 2023). Religious practices across Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and indigenous traditions also emphasize reverence for rivers, trees, animals, and the earth itself, which are often seen as sacred (Sharma & Kumar, 2021). Festivals, rituals, and community practices, such as tree worship, protecting village groves, and respecting water bodies, have long reinforced a sense of ecological morality (Sharma & Kumar, 2021). However, rapid urbanization, consumer aspirations, and lifestyle changes in modern India risk eroding some of these values (Guha, 2006). Studying environmental empathy and values through culturally validated tools is therefore crucial, as it helps connect traditional reverence for nature with contemporary demands for sustainable behavior (Tam, 2024).

Review of Literature

Two tools are particularly relevant for understanding the behavioural mechanisms behind environmental behavior. The Dispositional Empathy with Nature Scale (DENS) (Tam, 2013) looks at the extent to which individuals feel concern for and emotionally identify with the natural world. The Environmental Portrait Value Questionnaire (E-PVQ) (Bouman et al., 2018) focuses on people’s values, such as caring for others, protecting the environment, or seeking comfort and pleasure, and how these values influence their choices. Together, these scales address the cognitive and emotional aspects of environmental behaviour.

Even though these tools have been studied in Europe and other countries, they have not yet been validated in India. Given India’s unique traditions of environmental reverence that range from sacred groves to Gandhian principles of minimalism, psychological tools must account for these cultural influences to truly capture how Indians relate to nature (Ormsby & Bhagwat, 2010). Validating them in India can make research more accurate and also help design better programs to encourage pro-environmental behavior.

The E-PVQ measures four value types influencing environmental behavior: biospheric (care for nature), altruistic (care for others), egoistic (personal success, money, power), and hedonic (pleasure, comfort) (Bouman et al., 2018). Biospheric and altruistic values promote pro-environmental actions, while egoistic or hedonic values may reduce them (Steg, 2023). This helps identify which values encourage or hinder sustainability in different groups.

Derived from Schwartz’s PVQ, the E-PVQ uses short “portraits” describing people’s goals, which participants rate for similarity. This approach avoids abstract terms, reduces confusion, and works across languages and educational levels (Schwartz & Cieciuch, 2021). In India’s diverse cultural context, simple descriptions improve accuracy and fairness. Tested in Germany and the Netherlands, the E-PVQ showed strong reliability and structure, performing comparably to the Environmental Schwartz Value Survey (Bouman et al., 2018; Bouman & Steg, 2019). Participants found it easier and more relevant, and it predicted attitudes, habit changes, and policy support.

Validating the E-PVQ and DENS together is important because, while the two constructs are distinct, they complement each other in understanding environmental behavior. The E-PVQ captures the cognitive dimension of environmental values, reflecting what individuals consider important in guiding their actions (Bouman et al., 2018). In contrast, the DENS measures the emotional dimension, assessing empathy toward nature, and also taps into the experiential sense of connectedness with the natural world (Tam, 2013; Lovati et al., 2025). Together, these scales provide a more holistic picture of the human–nature relationship, linking values, feelings, and experience. Given India’s cultural, linguistic, and ecological diversity, validating both scales in Indian populations ensures that they accurately capture environmental attitudes and behaviors in this context.

Theoretical Framework

Value-Belief-Norm (VBN) Theory (Stern et al., 1999)

The Value–Belief–Norm (VBN) theory explains how values shape pro-environmental behavior through a sequential pathway: values influence ecological worldviews (beliefs), which in turn activate personal norms that guide behavior (Stern, 2000). Recent research confirms the robustness of this framework, demonstrating that self-transcendent values strongly predict environmental concern and behaviors across cultures (Wang et al., 2021; Zeiske et al., 2021). These values have consistently been shown to drive moral obligation and willingness to act on environmental issues (Al Mamun et al., 2025). The Environmental Portrait Value Questionnaire (E-PVQ) and the Dispositional Empathy with Nature Scale (DENS) both derive conceptually from VBN theory (Stern et al., 1999; Stern, 2000). E-PVQ operationalizes the role of biospheric and altruistic values in environmental contexts, while DENS expands the framework by integrating empathy as an affective basis for moral norms (Wang et al., 2022; Tam, 2013).

Schwartz’s Value Theory (Schwartz, 1992)

Schwartz’s theory identifies 10 universal value types (e.g., benevolence, universalism, power, achievement) that are structured in a circumplex model reflecting motivational conflicts and compatibilities (Schwartz, 1992). The most relevant axis of this model for Environmental Psychology contrasts self-transcendence (universalism, benevolence) with self-enhancement (power, achievement). Numerous studies confirm that self-transcendence values are consistently associated with environmental concern and sustainable behavior (Steg, 2016). The E-PVQ directly builds on Schwartz’s framework by focusing on four environmental value orientations: biospheric, altruistic, egoistic, and hedonic. This adaptation allows the universal value model to be applied to environmental issues, making it a widely used tool for predicting ecological attitudes and behaviors (Bouman et al., 2018).

By integrating affective dispositions, the two instruments extend beyond traditional cognitive models to account for the emotional pathways that drive ecological concern and action. Incorporating affective empathy improves predictions of behavior and provides a more holistic understanding of environmental engagement (Tam, 2013; Li et al., 2024).

Method

Hypothesis

Factorial validity: The DENS will show a unidimensional factor structure, while the EPVQ will show a two-factor structure reflecting biospheric/altruistic and egoistic/hedonic values.

Internal consistency: Both the DENS and EPVQ will demonstrate acceptable to high internal consistency (Cronbach’s α ≥ .80).

Convergent validity:

DENS scores will be positively correlated with EPVQ Factor 1 (biospheric/altruistic values), reflecting their shared emphasis on affective connection and pro-environmental concern.

DENS scores will be negatively correlated with EPVQ Factor 2 (egoistic/hedonic values), as these reflect self-enhancing motives that conceptually oppose empathy with nature.

Participants

A sample of 538 Indian students aged 10-19 (47.5% Male, 51.5% Female). All participants provided written informed consent after receiving a comprehensive explanation of the study procedure. The project under which the experimental protocol of the study was carried out has the approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC) of the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi.

Table 1 displays the sociodemographic characteristics of the sample.

Instruments

Environmental Portrait Value Questionnaire (EPVQ; Bouman et al., 2018).

The EPVQ is a 17-item instrument developed to assess environmental values using a portrait-based methodology that adapts Schwartz’s value theory to the domain of pro-environmental attitudes (Bouman et al., 2018). Each item presents a short vignette describing a person who embodies specific environmental values. Respondents are asked to rate, on a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = not like me at all to 7 = very much like me), the extent to which the described person’s values resemble their own. Higher scores indicate stronger endorsement of pro-environmental values.

The EPVQ has demonstrated strong psychometric properties, including robust construct validity, high internal consistency, and test–retest reliability (Bouman et al., 2018). Its vignette-based design has been highlighted as particularly suitable for minimizing social desirability bias, as it facilitates indirect self-assessment and enhances accessibility across age and educational groups. Cross-cultural studies have supported the applicability of the EPVQ in diverse contexts, including North America, Europe, Africa, New Zealand, and parts of Asia, with evidence of configural and metric invariance across demographic groups (Bouman et al., 2018). However, published validation studies of the EPVQ in India and Southeast Asia remain scarce.

Dispositional Empathy with Nature Scale (DEN; Tam, 2013)

The DEN is a 10-item self-report instrument designed to measure the dispositional tendency to emotionally empathize with the natural environment (Tam, 2013). Items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 7 = strongly agree), with higher scores reflecting a stronger affective connection and emotional resonance with nature. The DEN has consistently been shown to possess a unidimensional factor structure, strong internal consistency (α ≈ .90), and sound evidence of convergent and discriminant validity. It correlates positively with related constructs such as connectedness to nature and pro-environmental behavior, and negatively with measures of moral disengagement from nature (Tam, 2013; Zhang et al., 2024).

International validations (e.g., in Italy, China, and other cultural contexts) have replicated its single-factor structure, high reliability, and predictive validity, supporting its cross-national and cross-linguistic suitability (Tam, 2013; Lovati et al., 2025). Standard translation and back-translation procedures have been employed in these adaptations. While the DEN has not yet been formally validated in India or Southeast Asian contexts, findings from other Asian cultural settings suggest that the construct is theoretically and psychometrically appropriate for use in non-Western populations.

Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted using Jamovi statistical software version 2.6.44. To examine the structure of the EPVQ, confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed on the full sample. Two models were tested: a four-factor model with altruism, biospheric, egoistic, and hedonic subfactors, and a two-factor model combining altruism and biospheric into self-transcendence, and egoistic and hedonic into self-enhancement. CFA was also conducted on the DENS scale to test it as a one-factor model. Model fit was evaluated using RMSEA, CFI, TLI, and χ².

Correlations were computed to explore the relationships between DENS and EPVQ scores. This included correlations with the total EPVQ score, the two-factor model, and all four subfactors individually. Gender differences were examined using a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA), with DENS, self-transcendence, and self-enhancement as dependent variables.

The reliability of the scales was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. This was done for DENS, the total EPVQ, and both the two-factor and four-factor EPVQ models. These analyses helped ensure that the instruments were reliable and suitable for use in this study.

Results

Confirmatory Factor Analysis

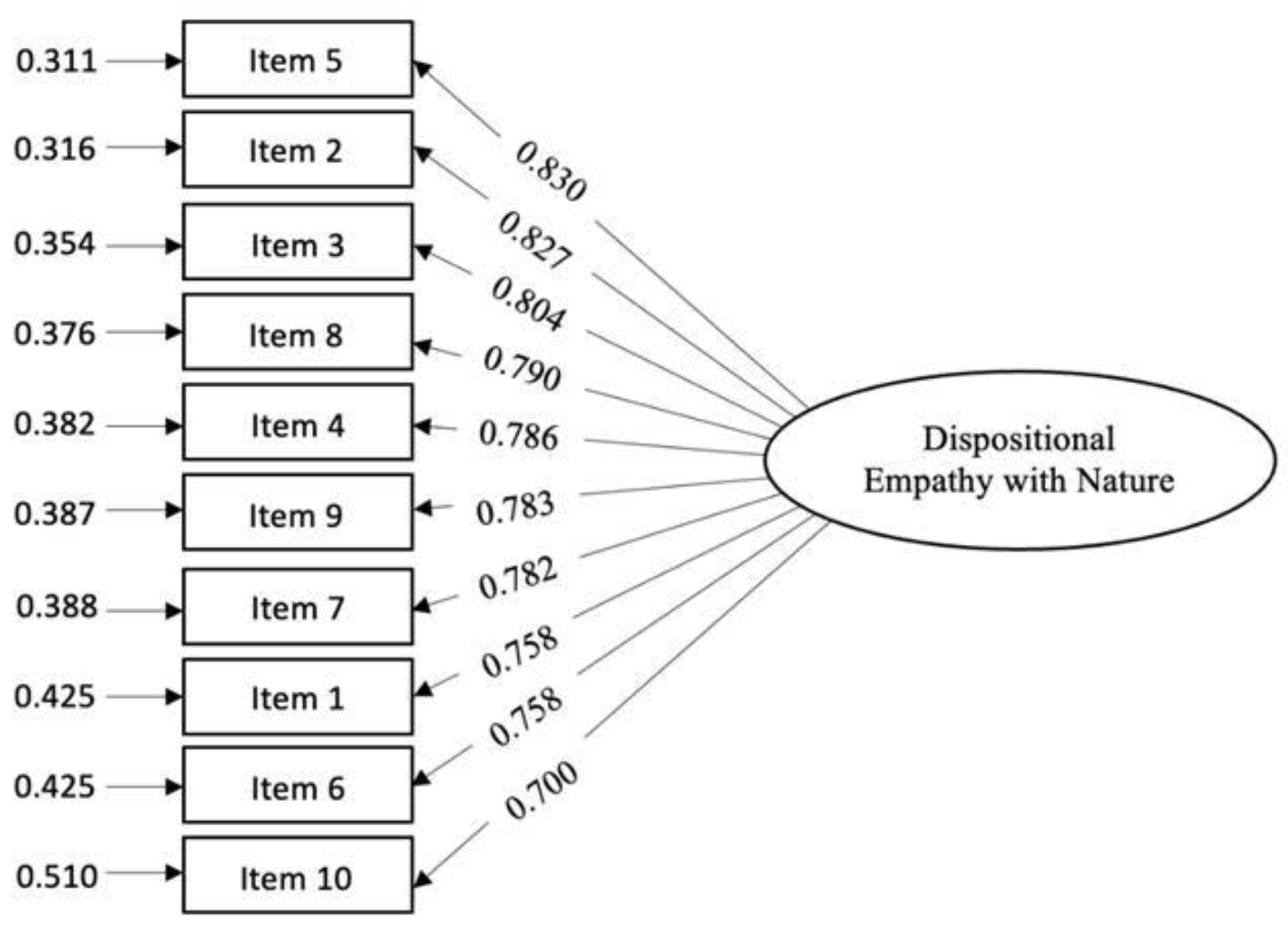

The confirmatory factor analysis of the data was run once for confirming the factor structure of DENS and twice for two different model structures of EPVQ. The confirmatory factor analysis of DENS revealed that all the factor loaded well on the scale, with factor loading ranging from 0.700 to 0.830 (

Table 1). The goodness of fit indices for DENS (

Table 2) revealed that all goodness of fit indices were found acceptable for the one factor model, with χ²(35) = 207, p < .001, χ²/df = 5.91, CFI = .94, TLI = .92, SRMR = .038, and RMSEA = .117 (90% CI [.102, .133]). While CFI, TLI, and SRMR suggested a good fit, the RMSEA value was higher than recommended. Overall, the results still supported a unidimensional model for the DENS.

The path diagram of the unidimensional model of DENS highlighted that all the factors had moderate to low error variances ranging from 0.311 to 0.510 (

Figure 1). This indicated that all the items loaded decently with lower margin of error for the Indian adolescents. This established a factorial validity to the conceptual model of DENS which had also been calculated so previously.

The confirmatory analysis for EPVQ was ran twice for the two and four factor models structures. The analysis revealed that the goodness of fit indices gave mixed results for the two factor and four factor solution, with the indices being, χ²(76) = 768, p < .001, χ²/df = 10.10, CFI = 0.758, TLI = 0.711, SRMR = 0.094, and RMSEA = 0.130, for the two factor structure and such for the four factor model, as; χ²(113) = 491, p < .001, χ²/df = 4.34, CFI = 0.903, TLI = 0.883, SRMR = 0.098, and RMSEA = 0.078. Looking at the indices (

Table 2), it can be seen that both two and four factor models had mixed results with respect to the goodness of fit. While CFI, TLI, and SRMR suggested a good fit for the four-factor solution, the χ²/df and RMSEA value was higher of the two-factor solution, suggesting a use of two factor solution.

Estimates of factor covariances was also calculated for the factor solutions in EPVQ (

Table 3). It was found that four factor model solution had moderate to low factor covariances between them while the two-factor model had a higher and stronger covariances, suggesting to use the two-factor model solution over two. The goodness of fit indices and factor covariances together suggested the use of two factor model solution of EPVQ for the Indian adolescents.

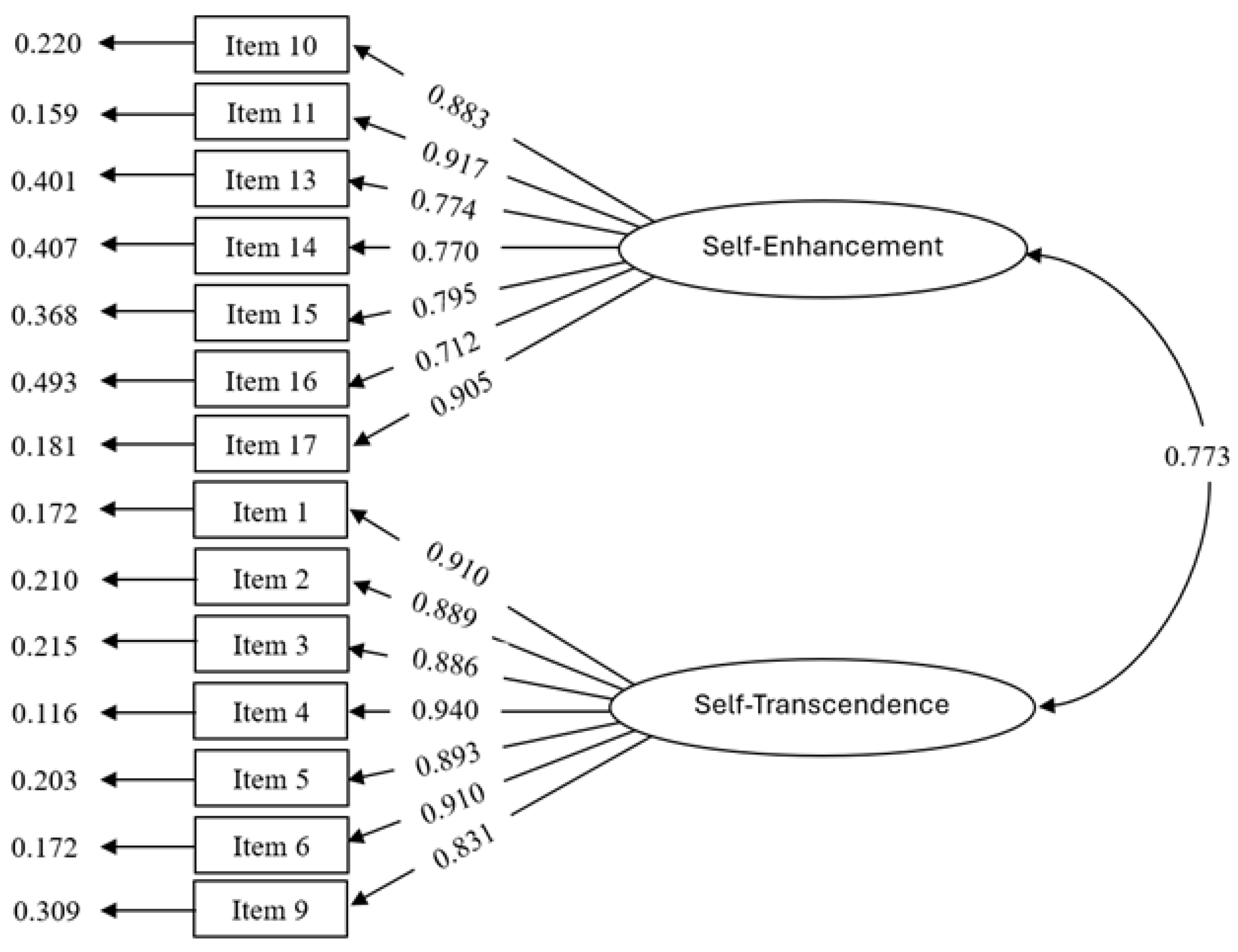

Confirmatory factor analysis for EPVQ found that all the items loaded significantly for the two-factor model solution for the sub-factors of self-enhancement and self-transcendence. The factor loadings for the two-factor structure ranged from 0.774 to 0.940 (

Table 4), with error variances ranging from 0.159 to 0.493 (

Figure 2) , suggesting a moderate to low error margins for the factor loading. Items 7, 8 and 12 were removed from the factor solutions since they provided a more than higher factor loading, leading to negative valued error variances, recommending a rephrased use of these items for the scale use with Indian adolescents.

Reliability Analysis and Intra-Correlations

Cronbach alpha values were calculated for the reliability analysis. It was found that (

Table 5), the Cronbach alpha value for DENS was 0.94, with both the sub-factors of EPVQ having a higher Cronbach alpha value of 0.765 and 0.848. In order to further compare the consistency of scores with the original study values, a comparison column is added in the table (

Table 5). This revealed that both DENS and a two factor model of EPVQ suggested a reliable measure for the Indian adolescent population.

Pearson correlations were also computed to see the inter and intra-factor correlations between and variables. It was found that DENS was strongly and positively correlated with the overall EPVQ score, r = .62, p < .001. Examining the EPVQ subfactors separately, DENS showed a strong positive correlation with EPVQ-SE, r = 0.35, p < .001, and a moderate positive correlation with EPVQ-ST, r = 0.46 p < .001. The two EPVQ factors themselves were also moderately correlated, r = 0.47, p < .001. According to Cohen’s (1988) guidelines, these represent moderate, and small-to-moderate effect sizes, respectively.

Table 6.

Correlational Analysis between DENS total score and Two Factors Model of EPVQ.

Table 6.

Correlational Analysis between DENS total score and Two Factors Model of EPVQ.

| Factors |

EPVQ-SE |

EPVQ-ST |

| DENS |

0.35** |

0.46** |

| EPVQ-SE |

- |

0.47** |

Gender Differences

A Multivariate Analysis of Covariance (MANCOVA) was conducted to explore gender-based differences in dispositional empathy with nature (DENS), self-transcendence values, and self-enhancement values. The overall multivariate effect of gender was statistically significant, Pillai’s Trace = 0.0255, F(3, 532) = 4.65, p = .003, suggesting that gender influenced the combined set of dependent variables. Follow-up univariate analyses indicated a significant effect of gender on self-transcendence values, F(1, 534) = 6.08, p = .014, with females reporting higher self-transcendent orientations than males. No significant gender differences emerged for DENS, F(1, 534) = 0.40, p = .530, or self-enhancement values, F(1, 534) = 1.14, p = .287. Although the Box’s M test revealed a violation of covariance homogeneity (p = .002), Pillai’s Trace was considered the most robust indicator for interpretation. Overall, the results suggest that female adolescents tend to endorse stronger self-transcendent environmental values, reflecting greater moral and emotional connection to nature.

Discussion

The present study aimed to validate two key instruments used in Environmental Psychology– the Environmental Portrait Value Questionnaire (EPVQ) and the Dispositional Empathy with Nature Scale (DENS) in an Indian adolescent and youth sample. Together, these measures provide a comprehensive understanding of how values and empathy shape people’s emotional and cognitive relationship with nature within the Indian cultural setting.

The DENS scale was strongly supported as a unidimensional measure. Confirmatory factor analysis showed that all items loaded well on a single factor, with high reliability (α = 0.94). Although the RMSEA value was slightly elevated at around 0.096, other fit indices were strong. Small deviations of this kind are often observed in models with few degrees of freedom (Kenny et al., 2015). Conceptually, a single-factor model fits well with Indian philosophical and cultural traditions, where humans and nature are seen as deeply interconnected (Shaw, 2016). Similar unidimensional findings have been reported in other cross-cultural validations of empathy-with-nature scales conducted in Hong Kong, Spain, and Italy (Tam, 2013; Beery et al., 2023). The consistent unidimensionality of the DENS suggests that empathy with nature may represent a universal emotional disposition, even though the way it is expressed may vary across cultural contexts. In India, this emotional bond is often intertwined with compassion, spirituality, and the belief in coexistence between humans and the natural world.

The correlations between DENS and EPVQ provided further clarity about how these constructs relate. DENS showed the strongest correlations with biospheric values (r ≈ 0.572) and self-transcendence (r ≈ 0.585), indicating that empathy for nature aligns most closely with values of care, concern, and responsibility toward the environment. Correlations with egoistic and hedonic values were weaker but still significant (r ≈ 0.410), suggesting that empathy with nature can exist alongside self-oriented motivations. In India, environmental concern is often tied to moral and spiritual ideals rather than to material benefits or pleasure (Awasthi, 2021). This is consistent with earlier work showing that value-based and moral motivations tend to be stronger predictors of pro-environmental behaviors than hedonic considerations (Van Riper et al., 2018).

For the EPVQ, confirmatory factor analyses supported both the original four-factor and the proposed two-factor structures, with acceptable model fit (

Table 3). However, the two-factor solution showed clearer factor loadings, smaller error variances, and stronger conceptual coherence. This model grouped biospheric and altruistic values together as self-transcendence, and egoistic and hedonic values as self-enhancement. These findings align with Schwartz’s higher-order value framework (Schwartz, 1992) and its application in environmental psychology (Bouman et al., 2018; Steg et al., 2016). After removing three items (Item 7, Item 8 and Item 12), the two-factor model demonstrated improved loadings and fit, suggesting that this structure better represents value organization among Indian participants. These results indicate that while the EPVQ is theoretically robust, certain items may require adaptation for greater cultural relevance in the Indian setting.

The three excluded items provide valuable insight into cultural nuances that may influence how adolescents interpret value statements. Item 7 (“It is important for Umang that every person is treated justly”) may have performed poorly because the concept of “justice” is often understood differently in collectivist societies. For Indian adolescents, fairness is often viewed through relationships, respect, and family expectations rather than as an abstract social principle. Item 8 (“It is important for Umang that there is no war or conflict”) may have seemed too distant or impersonal for younger participants whose experiences of conflict are likely interpersonal or community-based rather than global. Prior studies have also found that abstract, globally oriented items can underperform in non-Western youth samples because they lack direct personal relevance (Sortheix & Schwartz, 2017). Item 12 (“It is important for Umang to do things that Umang enjoys”) may have been interpreted in line with cultural norms that discourage overt self-focus. In collectivist cultures, personal enjoyment is often balanced against social approval and responsibility (Karaosman et al., 2015). These differences in interpretation likely contributed to the unstable loadings and suggest that future adaptations should reframe such items in culturally meaningful ways.

The stronger performance of the two-factor model aligns with previous research showing that collectivist societies often merge altruistic and biospheric values into a single self-transcendence dimension (Imaningsih et al., 2023). In India, this integration is consistent with philosophies such as Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam (“the world is one family”) and Gandhian environmental ethics, both of which emphasize harmony and compassion across human and natural life (Devi, 2025). The merging of altruistic and biospheric values reflects a worldview where care for others and care for nature are inseparable moral duties. Similarly, the combination of egoistic and hedonic values as self-enhancement reflects a more social interpretation of individual success. In India, ambition and enjoyment are not necessarily viewed as self-serving; they are often linked with familial responsibility and collective advancement. Recent studies in Southeast Asian contexts have also shown that self-enhancement can motivate pro-environmental behavior when it aligns with social prestige or community reputation (DeVille et al., 2021; (Karaosman et al., 2015c). The positive association between DENS and self-enhancement observed in this study supports this idea and suggests that empathy and ambition can coexist rather than compete in collectivist cultures.

The stronger endorsement of self-transcendent environmental values among female adolescents in this study aligns with previous research showing that Indian women tend to exhibit more positive environmental attitudes than men (Dhenge, 2022). Similar gender differences have been observed globally, where women consistently report higher pro-environmental concern and engagement (Echavarren, 2023). This pattern is often attributed to gendered socialization processes and traditional caregiving roles that encourage empathy, relational responsibility, and sensitivity to ecological well-being (Tien & Huang, 2023). In the Indian context, these cultural expectations and lived experiences likely foster a deeper moral and emotional connection with nature, offering a meaningful explanation for the observed gender difference in self-transcendent values.

Overall, the findings show that while the basic structure of environmental empathy and values is consistent with existing theoretical models, their expression is influenced by cultural context. The DENS captures a unified emotional connection to nature that resonates deeply with India’s eco-spiritual worldview. The EPVQ, in its two-factor form, reflects the integration of social and ecological concern that defines Indian collectivist ethics. The need to reword or refine certain EPVQ items highlights that direct translations of Western tools may not always capture the subtle ways Indian respondents think about moral and environmental values. Future research should continue adapting and refining these measures to ensure that concepts like justice, conflict, and pleasure are expressed in culturally meaningful language. This will enhance the accuracy and depth of environmental psychology research in India and provide tools that better represent how people in this cultural context relate to nature.

Limitations and Implications

The present study offers valuable insights into the assessment of environmental values and empathy with nature in the Indian context. By validating the EPVQ and DENS among Indian adolescents, it provides researchers with culturally appropriate tools to explore environmental psychology within collectivist societies. The positive relationship observed between empathy with nature and self-enhancement values suggests that environmental initiatives in India could benefit from messages that appeal to both personal and collective motives. Framing pro-environmental behavior in terms of personal well-being, social recognition, and community benefit may therefore enhance engagement. These results also indicate that self-transcendence and self-enhancement values may not be mutually exclusive in interdependent cultural settings but may work together to promote ecological concern. However, the study’s focus on adolescent, school-based participants limits the generalizability of the findings to other age groups and non-institutional populations. The reliance on self-report data raises the possibility of social desirability effects, and the cross-sectional design restricts the ability to draw conclusions about causal relationships or changes over time.

Conclusion

This study provides one of the first validations of the EPVQ and DENS in India, demonstrating their reliability and cultural relevance. The findings highlight that empathy toward nature and environmental values are shaped by both self-oriented and other-oriented motivations, reflecting the complexity of moral and emotional connections with nature in collectivist contexts. By emphasizing the importance of culturally grounded measurement, this research contributes to a broader understanding of how diverse value systems influence pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

References

- Al Mamun, A., Yang, M., Hayat, N., et al. (2025). The nexus of environmental values, beliefs, norms and green consumption intention. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 12, 634. [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, A. (2021). A reinterpretation of Hindu spirituality for addressing environmental problems. Religions, 12(5), 358. [CrossRef]

- Beery, T., Olafsson, A. S., Gentin, S., Maurer, M., Stålhammar, S., Albert, C., Bieling, C., Buijs, A., Fagerholm, N., Garcia-Martin, M., Plieninger, T., & Raymond, C. M. (2023). Disconnection from nature: Expanding our understanding of human–nature relations. People and Nature, 5(2), 470–488. [CrossRef]

- Bouman, T., & Steg, L. (2019). Motivating society-wide pro-environmental change. One Earth, 1(1), 27–30. [CrossRef]

- Bouman, T., & Steg, L. (2021). Environmental values and identities at the personal and group level. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 42, 47–53. [CrossRef]

- Bouman, T., Steg, L., & Kiers, H. A. L. (2018). Measuring values in environmental research: A test of an environmental portrait value questionnaire. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 564. [CrossRef]

- Devi, D. S. B. (2025). Traditional Indian knowledge and environmental conservation. American Journal of Social and Humanitarian Research, 6(5), 1157–1166. https://globalresearchnetwork.us/index.php/ajshr/article/view/3655.

- DeVille, N. V., Tomasso, L. P., Stoddard, O. P., Wilt, G. E., Horton, T. H., Wolf, K. L., Brymer, E., Kahn, P. H., & James, P. (2021). Time spent in nature is associated with increased pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(14), 7498. [CrossRef]

- Guha, R. (2006). How much should a person consume? Environmentalism in India and the United States. University of California Press.

- Imaningsih, E. S., Ramli, Y., Widayati, C., Hamdan, & Yusliza, M. Y. (2023, October 30). The influence of egoistic values, biospheric values, and altruistic values on green attitudes for re-intention to use eco-bag: Studies on millennial consumers. Social Space Journal. https://socialspacejournal.eu/menu-script/index.php/ssj/article/view/269.

- Kar, A. K. (2023). The concept of Vasudhaiva Kutumbakam (The world is one family).

- Karaosman, H., Morales-Alonso, G., & Grijalvo, M. (2015). Consumers’ responses to CSR in a cross-cultural setting. Cogent Business & Management, 2(1). [CrossRef]

- Kenny, D. A., Kaniskan, B., & McCoach, D. B. (2015). The performance of RMSEA in models with small degrees of freedom. Sociological Methods & Research, 44(3), 486–507. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Zhao, Y., Huang, Q., Deng, J., Deng, X., & Li, J. (2024). Empathy with nature promotes pro-environmental attitudes in preschool children. PsyCh Journal, 13(4), 598–607.

- Long, J. D. (2023). Advaita Vedānta and its implications for deep ecology. Journal of Dharma Studies, 6(1), 87–98. [CrossRef]

- Lovati, C., Manzi, F., Di Dio, C., Massaro, D., Gilli, G., & Marchetti, A. (2025). Bonding with nature: A validation of the Dispositional Empathy with Nature scale in Italy. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1388798. [CrossRef]

- McCaffery, J., & Boetto, H. (2025). Eco-emotional responses to climate change: A scoping review of social work literature. The British Journal of Social Work, 55(1), 120–140.

- Ormsby, A. A., & Bhagwat, S. A. (2010). Sacred forests of India: A strong tradition of community-based natural resource management. Environmental Conservation, 37(3), 320–326. [CrossRef]

- Sahni, P. S., Rajyaguru, C., Narain, K., Miedenbauer, K. L., Kumar, J., & Schonert-Reichl, K. A. (2024). Neural dynamics of development of nature empathy in children: An EEG/ERP study. Current Research in Ecological and Social Psychology, 7, 100210. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 25, pp. 1–65). Academic Press. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S., & Cieciuch, J. (2021). Measuring the refined theory of individual values in 49 cultural groups: Psychometrics of the revised portrait value questionnaire. Semantics Scholar. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Measuring-the-Refined-Theory-of-Individual-Values-Schwartz-Cieciuch/ee916ab8610e8d86f08705aacea057ff24e90204.

- Sharma, S., & Kumar, R. (2021). Sacred groves of India: Repositories of a rich heritage and tools for biodiversity conservation. Journal of Forestry Research, 32, 899–916. [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J. (2016). Religion, “nature” and environmental ethics in ancient India: Archaeologies of human:non-human suffering and well-being in early Buddhist and Hindu contexts. World Archaeology, 48(4), 517–543. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26619414.

- Sortheix, F. M., & Schwartz, S. H. (2017). Values that underlie and undermine well-being: Variability across countries. European Journal of Personality, 31(2), 187–201. [CrossRef]

- Steg, L. (2016). Values, norms, and intrinsic motivation to act proenvironmentally. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 41, 277–292. [CrossRef]

- Steg, L. (2023). Psychology of climate change. Annual Review of Psychology, 74, 391–421. [CrossRef]

- Stern, P. C. (2000). New environmental theories: Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. Journal of Social Issues, 56, 407–424. [CrossRef]

- Stern, P. C., Dietz, T., Abel, T. D., Guagnano, G. A., & Kalof, L. (1999). A value-belief-norm theory of support for social movements: The case of environmentalism. Human Ecology Review, 6, 81–97.

- Strefler, J., Merfort, L., Bauer, N., Stevanović, M., Tänzler, D., Humpenöder, F., Klein, D., Luderer, G., Pehl, M., Pietzcker, R. C., Popp, A., Rodrigues, R., Rottoli, M., & Kriegler, E. (2024). Technology availability, sector policies and behavioral change are complementary strategies for achieving net-zero emissions. Nature Communications, 15(1). [CrossRef]

- Tam, K.-P. (2013). Dispositional empathy with nature. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 35, 92–104. [CrossRef]

- Tam, K.-P. (2022). Gratitude to nature: Conceptualization, measurement, and effects on pro-environmental behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 79, 101754. [CrossRef]

- Tam, K.-P. (2024). Culture and pro-environmental behavior. Current Opinion in Psychology, 62, 101986. [CrossRef]

- Van Riper, C. J., Lum, C., Kyle, G. T., Wallen, K. E., Absher, J., & Landon, A. C. (2018). Values, motivations, and intentions to engage in proenvironmental behavior. Environment and Behavior, 52(4), 437–462. [CrossRef]

- Wang, L., Sheng, G., She, S., & Xu, J. (2023). Impact of empathy with nature on pro-environmental behaviour. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 47(6), 2510–2526. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., van der Werff, E., Bouman, T., & Steg, L. (2021). I am vs. we are: How biospheric values and environmental identity of individuals and groups can influence pro-environmental behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 618956. [CrossRef]

- Zeiske, N., Venhoeven, L., Steg, L., & van der Werff, E. (2020). The normative route to a sustainable future: Examining children’s environmental values, identity and personal norms to conserve energy. Environment and Behavior, 53(10), 1118–1139. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).