2. Materials and Methods

Some terminology that is compatible with Oral Theory is not used often in the literature on the Homeric Question, or absent in it: oral scopes, roles, oral characteristics, and clusters of oral characteristics.3 An oral scope is a traditional subspecialty of a bard that can be used to perform shorter or longer passages, or complete poems. Oral traditions, stories, story types, type-scenes, and roles are all oral scopes. Roles are subspecialties that bards can use during alternating performances with multiple bards. For example, a god role could be mastered by a bard who improvises the passages about the gods. An oral characteristic is any recurring aspect or element of a poem by which a certain oral scope can be recognized and distinguished from other oral scopes. Examples are ‘lineages to an ancestor’, ‘epithet about the fertility of the soil’, and ‘digression’. A cluster of oral characteristics is itself an oral characteristic that consists of multiple oral characteristics that are strongly related within their oral scope, such that they occur often closely together in the text, or are conceptually related. Examples are ‘wine, meals, and washing hands’, ‘Muses and Apollo’, and ‘bow, Apollo, and Lycia’. However, clusters can be much larger than these examples. The whole oral scope is itself a cluster.

Many oral scopes in the Homeric works are hidden (hard to reveal) because of at least four reasons: they are broad (consisting of a wide variety of oral characteristics), they occur mixed with other oral scopes, they occur distorted because they acquired a fixed place in a story that evolved through the ages, and/or they occur in an incomplete manner (displaying only two or three oral characteristics in a given passage). Examples of oral scopes that are not hidden are short type-scenes of the Ionian Tradition: the preparation of meals, going to bed, and announcing a new day. Revealing a hidden oral scope often results in a wealth of new information.

The Homeric artificial language largely makes use of the Ionic dialect, but has Aeolic ingredients for words or phrases that do not fit in the hexameter when translated to the Ionic dialect.4 Very sometimes, there are even Arcadocypriot archaisms that stem from Mycenaean Greece. Attic variants might be intrusions after the Homeric works got literally fixed. The occurrences of dialectic variations are therefore typically not oral characteristics of any oral scope, because they are demanded by the hexameter system, rather than by their meaning. This may excuse the fact that the oral characteristics are not described in Homeric Greek. The oral characteristics and the oral scopes that spread and survived through space and time must necessarily be synchronically and diachronically translatable and meaningful. Using a mother-tongue translation may therefore have been an underestimated success factor in obtaining the presented results, because no attention needs to be paid to the linguistic layer.

The manual clustering methodology consists of listing clusters of oral characteristics that are often close in the text and that have many conceptual relations. A complete cluster then becomes an oral scope. For each cluster, a set of passages needs to be collected (where the clusters occur) and a set of characteristics (what the clusters consist of). Different clusters can come together to form a larger cluster. For example, the type-scene of the brave scout is a cluster consisting of 34 oral characteristics (Ns1-Ns34),5 but is itself an oral characteristic of three other oral scopes (the Ionian Tradition: I18, the European Narrative Role: N6, the Helen Narrative: Nh11). The largest clusters found via this methodology have the structure of an oral tradition in itself.

If two characteristics within the same oral scope have a conceptual relation, then the existence of this relation will often be affirmed by the bards who use this scope, which is done by mentioning both characteristics and their relation together. An example is the relation between building a wall of earth and building a burial mound of earth. The fact that they are mentioned closely together, together with the (negated) idea that they both cost a lot of work to execute (Iliad 7.430-441), increases the probability that they belong to the same oral scope.

In this study, a Dutch translation was used that is helpful but still accurate on the conceptual level.6 For example, the terms Argives, Achaians, and Danaans are all translated by ‘Greeks’, because these three Homeric terms are used wherever the concept ‘Greeks’ has to fit in the hexameter. It is evident that pattern recognition, comparison, and analysis are easier when the same concepts are always referred to by the same names. Other translations and the Homeric Greek text were consulted sporadically. The same copy was used in the long term, given that fast lookup and comparison of passages in the same layout were found to be indispensable. The study was conducted over a period of more than twenty years.

In order to get a better grasp on the variation that was introduced by the transmission history, an analysis was made of West’s edition of the Iliad, which can be found in the Homeric Traditions Apparatus.7 The idea is that a hypothesized interpolation that is in fact original, belongs to the same combination of oral scopes by which it is surrounded. The conclusions were drawn that longer hypothesized interpolations fit more clearly in their context and that West rejected too many lines.

3. Results

Using the manual clustering methodology, 25 hidden oral scopes were found, a total of at least 776 oral characteristics, and 832 passages that are somehow colored by one of the oral scopes.8 The 25 hidden oral scopes consist of 3 oral traditions, 6 story types, 3 stories, 8 type-scenes, and 5 roles. The number of 776 characteristics is an underestimation, because many characteristics are themselves presented as a short list or a grouping of characteristics.

The many results vary greatly in the dimensions of being easy to validate, being uncontroversial, and being significant. Nevertheless, in the rest of this section, they are ordered according to the hypothesized oral tradition with which they are associated. After that, a single highlight is made of a result that is moderately easy to validate, partially controversial, but highly significant. It is about setting up the army before the fight, which relates to the non-Greek origin of the rampart and the ditch in the Iliad.

3.1. The Mycenaean Tradition

The Mycenaean Tradition is a Homeric oral tradition that is found almost exclusively in digressions in the Iliad and to a lesser extent in the Odyssey. The digressions have a typical compact style in which the oral characteristics follow each other closely.

That the Mycenaean Tradition most probably stems from Mycenaean Greece is apparent from its eighteen most important oral characteristics (M1-M18): digressions; age-old, well-known myths and stories; kings; the seven-gated Thebes; the change of power; bloody feuds within the family; the revenge on the return; (divine) genealogies; wars against cities or between peoples; the cycle of misery; failed marriages; the brave hero; the many places and personal names; the Peloponnese (and Central Greece); riches of the soil, typical of a place or city; fatal women; the hero who defeats a whole army; and the exiled son. Many of these characteristics are related to the intense struggle for the power in luxurious castles. We find such castles in Mycenaean Greece, but not after it.

Remarkably, shipping is not a Mycenaean-Homeric characteristic, even though the Mycenaeans knew seafaring. There is only a single occurrence of shipping that clearly belongs to a Mycenaean-Homeric context, namely the flight of Tlepolemos from Argos to Rhodes Island (Iliad 2.653-670). This stresses the importance of making the historical analysis independent of the clustering effort.

Two story types are strongly related to the Mycenaean Tradition: the King Story Type and the Hero Story Type.9 Their characteristics and their many concrete variants further corroborate that the discovered Mycenaean Tradition really stems from Mycenaean Greece. For example, ‘king’ is an oral characteristic of both story types.

The King Story Type is about a city in which the king is betrayed by his wife during his absence. The wife remarries after which the king assembles an army to take back the power. It is ultimately the son of the king who succeeds in this task. The King Story Type can be recognized by thirty-four oral characteristics, such as attackers who get into the city by a ruse (Mk20), the fight during a feast or solemn games (Mk21), and the transport of corpses (Mk26). The main theme is the loyalty versus the infidelity (Mk30) of those who remain behind during the absence of the king. Four concrete king stories about four cities have the characteristics of the King Story Type. They are about Mycenae, Ithaca, Thebes, and Troy.

The Hero Story Type is about a hero with royal blood who has a difficult childhood and an exceptional education. When he becomes an adult, he proves his special origin through heroic deeds in a neighboring kingdom.

One way to show that the list of oral characteristics really constitutes a separate oral scope or oral tradition is to annotate passages that are colored by this oral scope with the oral characteristics from the list. The short descriptions of the oral characteristics can be put in a footnote. The following extract of a digression made by Phoinix can serve as an example (Iliad 9.478-484):

aφεῦγον10 (M1, 19) ἔπειτ᾽ ἀπάνευθε (24) δι᾽ Ἑλλάδος (13) εὐρυχόροιο (15),

Φθίην (13) δ᾽ ἐξικόμην (24, 44) ἐριβώλακα (15) μητέρα (15) μήλων(31)

ἐς Πηλῆα (13, 20) ἄναχθ᾽ (3): ὃ δέ με πρόφρων (30) ὑπέδεκτο (34),

καί μ᾽ ἐφίλησ᾽ (30) ὡς εἴ τε πατὴρ (30) ὃν παῖδα (30) φιλήσῃ (30)

μοῦνον (5, 30) τηλύγετον (24) πολλοῖσιν (23) ἐπὶ κτεάτεσσι (5, 23, 30, 34),

καί μ᾽ ἀφνειὸν (23, 26) ἔθηκε (5), πολὺν δέ μοι ὤπασε (5) λαόν (3, 22, 26):

ναῖον (44) δ᾽ ἐσχατιὴν (44) Φθίης (13) Δολόπεσσιν (13, 22) ἀνάσσων (3).

Then (M1) I fled (M19) far away (M24) through Hellas (M13) with its wide lands (M15) and I arrived (M24, M44) at Phthia (M13), wealthy (M15) in flocks (M31) and mother (M15) of sheep (M31), and to king (M3) Peleus (M13, M20), who welcomed (M34) me friendly (M30). He loved (M30) me as a father (M30) loves (M30) his only (M5, M30), far-wandering (M24) son (M30), who is heir (M5) to many (M23) possessions (M23, M30, M34). He made (M5) me rich (M23, M26) and granted me a large people (M3, M5, M22, M26) and living (M44) in farthest (M36, M44) Phthia (M13), I reigned (M3) over the Dolopians (M13, M22).11

3.2. The European Tradition

The European Tradition12 consists of the European War Role and the European Narrative Role.13 It is hypothesized that stories in the European Tradition were performed by two bards – a War Bard and a Narrative Bard – who took turns. More bards with dedicated roles may have been added on Greek soil, as the Iliad tradition became richer. The analysis of our Iliad (the Iliad that we know) suggests the presence of a God Bard and an Achilles Bard in addition to these two European bard roles.

3.2.1. The European War Role

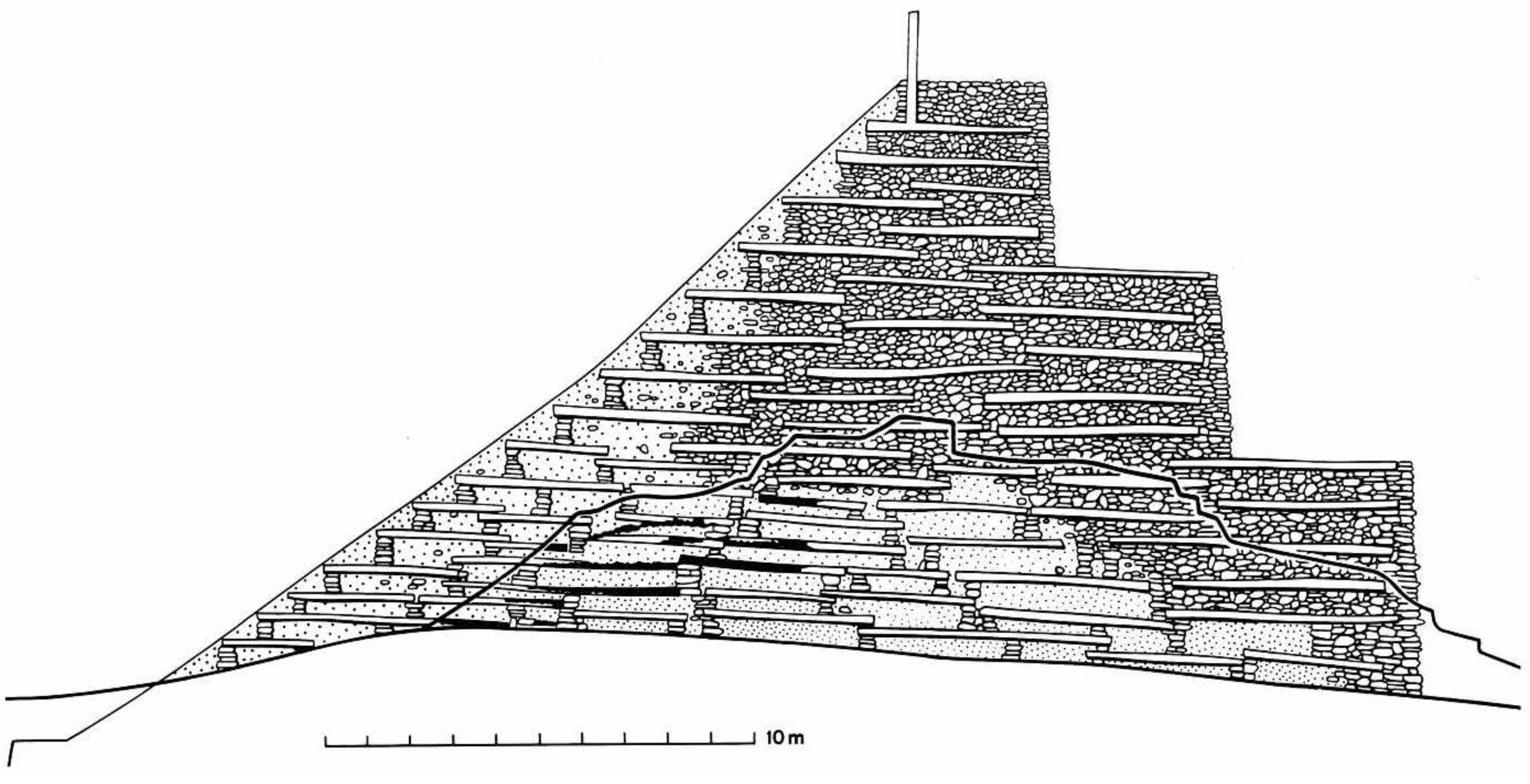

The ten most important oral characteristics of the European War Role (E1-E5) are the battle scene, chariot warriors and infantry, the clan system, the rampart and the ditch, thematic type-scenes, the warrior who does not fight, setting up the army before the fight, fame for the father, the resentful warrior, and the withheld honor gift. Both the European War Role and the European Narrative Role must stem from non-Greek European warrior clans. The main indication for this is the rampart and the ditch of wood and earth (E4, N9) that the Greeks built around their ships on the Trojan beach. Such ramparts with a ditch around (see

Figure 1) are ubiquitous in non-Greek Europe, but they were barely ever used in Greece or Turkey.

14 It is especially the determination that this oral characteristic is highly traditional that proves the validity of this argument.

There are two arguments why the earthen rampart and the ditch are traditional characteristics, rather than fabrications that happen to occur in our Iliad. First of all, there are several chapters in the Iliad that are devoted to the attack on the earthen rampart, while there are only two short passages that suggest a possible attack on the stone ramparts of Troy.15 Second, the rampart, the ditch around the rampart, and a bridge over the ditch are part of one of the hidden type-scenes, namely setting up the army before the fight (E7).16 This finding is highlighted in the last subsection of this section. Apart from the wall and the ditch, also the way of fighting (similar to that of the Celts) and the burial customs (incineration, urns, and burial mounds) fit a Central-European origin.17

There are six more hidden type-scenes of the European Tradition: fame for the father, the resentful warrior, the withheld honor gift, the warrior in need and the helper, the cowardly archer, and the warrior who blames his companion.18 They are thematic type-scenes, because they are related to important themes in the European stories. All these six type-scenes are related to one super-theme: the warrior who does not fight (E6).

3.2.2. The European Narrative Role

The European Narrative Role shares its societal background with the European War Role. In fact, the Central-European burial customs that we find in the Iliad (incineration, urns, and burial mounds) are more tightly related to the Narrative Role as compared to the War Role, because the wall of wood and earth of the Greeks is built together with a large burial mound in a long passage that clearly belongs to the Narrative Role.19 The evidence for a non-Greek European origin is therefore also strong for the Narrative Role.

The Narrative Role and the War Role also share the same themes, such as the warrior who does not fight and the withheld honor gift. This indicates that the two European bard types could alternate to improvise the same stories. While the European War Bard performed the raw battle-scene passages, the Narrative Bard developed the story in between these war passages. This is evident from the twelve most important oral characteristics of the Narrative Role (N1-N12): the cooperation with the European War Role; themes and motifs; war assemblies; oaths and treaties; burial mounds, cremation, and urns; the type-scene of the brave scout; the diversification from the fight; speeches; ramparts, ditches, gates, and the battlefield; wine; the alternation of day and night; and to wash and to anoint.

Once the passages of the Narrative Role are identified, it is much easier to find a series of motifs and themes that belong to these passages. Some examples are Aias, the greatest hero after Achilles (Na12); Diomedes, the youth who turns out to be the greatest hero (Nh2); and becoming unarmed, losing the last spear (Nc14).

By finding always more motifs and themes, it then becomes possible to distinguish three separate stories: the anger of Achilles, the abduction of Helen, and the compassion of Achilles.20 The themes, motifs, and other characteristics enable the creation of speculative reconstructions of the three stories. The anger of Achilles is about a great hero, Achilles, who refuses to fight because the clan leader, Agamemnon, withheld his honor gift. The main theme of the story about the abduction of Helen is that violating oaths and treaties is punished by the supreme god. At last, the compassion of Achilles is about the compassion of a great hero, Achilles, that turns into ruthlessness when the Trojan Hektor kills Achilles’ dearest companion Patroklos. In all three of these stories, the Greek and the Trojan camp can be made symmetrical. Both sides live in a fortified village that is surrounded by a wall of earth and wood and a ditch. The Trojans trying to set the Greek ships on fire goes back to stories in which houses in a village are set on fire. This also explains why the same type-scene of setting up the army before the fight (E7) is applied to both the Greek and the Trojan sides, and why the warriors line up outside of the walls (Es10): without defense, the walls of earth and wood can easily be invaded.

A remarkable fact about the Narrative Role is that Odysseus has the role of a herald in it.21 In the Narrative-Role passages, Odysseus performs tasks normally done by heralds, and he is mentioned closely together with heralds. For example, he is the most important delegate who is sent from Agamemnon to Achilles. Furthermore, the name ‘Odysseus’ is similar to that of two heralds: Idaios and Odios. This role as a herald is closely related to the extensive Narrative-Role type-scene of the brave scout (N6, Ns1-Ns34), in which Odysseus is often the main protagonist.22 This in turn can explain the merger with the Odysseus of the Mycenaean King Story of Ithaca.

3.3. The Aeolian Tradition

The Aeolian Tradition can be generally divided in a Homeric and a post-Homeric phase. The tradition corresponding to the Homeric phase is the Aeolian-Homeric Tradition, while that of the post-Homeric phase is called the Aeolian-Roman Tradition, for reasons that are explained further.23 Eight of the ten most important oral characteristics of the Aeolian-Homeric tradition (A1-A10) are the environment of Troy; proper names specific to the Aeolian Tradition; precious, special horses; defensive walls with a history; eponyms; seafaring, storms at sea, and islands; Aeneas; and Herakles. While the Aeolian Tradition seems to have evolved from the Mycenaean Tradition (A2), it appears in the Iliad in a dense mixture with the European War Role (A3).

The Aeolian Tradition appears more prominently in Iliad 5 (the ἀριστεία [or triumphant raid] of Diomedes), Iliad 20 (the ἀριστεία of Achilles), and Iliad 21 (Achilles in the river Xanthos). The reason for this is most probably the association with Diomedes (A16), Achilles (A15), a river (A11), the name Xanthos (A17), and the mixture with the European War Role (A3), which are all important oral characteristics of the Aeolian Tradition.

Even though a historical destruction of Troy may have contributed to the story of the Trojan War, it is the mythologization and the local Anatolian stories of the new homeland of the Aeolian Greeks who colonized the region around Troy in the Dark Ages that seem to explain the Trojan War story and the origins of the Aeolian Tradition in the first place.24 In this respect, the ruins of Troy sufficed as an element around which the oral characteristics of the Mycenaean King Story Type could stick together. In this new homeland, the Mycenaean Tradition could branch off and evolve into the Aeolian-Homeric Tradition.

While the Aeolian Tradition may be an interesting phenomenon in the analysis of the Iliad, it has its historical importance with respect to the origins of Roman mythology. As it turns out, Roman stories are largely derived from the Aeolian-Homeric Tradition, as compared to the other three Homeric traditions. In fact, after the Iliad got fixed, the Aeolian-Homeric Tradition has evolved further into the Aeolian-Roman tradition. Fourteen additional oral characteristics can be found in Vergil’s Aeneid and other Aeolian-colored stories, but not often (less than three times) in the Iliad.

That the Aeolian-Roman tradition is bound up with Greek colonization is evidenced by two facts: it appears on Italian soil and its oral characteristics are related to colonization. The six most important additional characteristics of the Aeolian-Roman tradition (AR1-6) are the founding of cities and colonization, the mother goddess Cybele, the stories of the Trojan Cycle, difficult wanderings in far-off places, the leader followed by a large group, and revealed conditions for an expedition to succeed. The first and the last three are indeed related to colonization.

Archaeological finds, such as pottery decorations, often reveal the Aeolian-Roman Tradition. The cult that worshipped Cybele stems from Anatolia and its spread in Greece and Italy can be traced archaeologically.25 It seems plausible that the Aeolian-Roman Tradition spread together with this cult. Moreover, there are many post-Homeric stories that witness the spread of the Aeolian-Roman Tradition. Examples are the Trojan Cycle (Proc. Chrest.), the horses of the Thracian Diomedes (D.S. 4.15.3-4), the biography of Achilles (e.g., Soph. Tr.), Herakles and the serpent woman (Hdt. 4.9-10), Apollonius’ Argonautica, many stories about the founding of cities (e.g., Apollod. 2.5.8: the founding of Abdera), and, last but not least, Vergil’s Aeneid.

The story about Herakles and the serpent woman nicely illustrates how strongly the Aeolian-Roman stories are determined by the Aeolian-Roman characteristics. During one of Herakles’ wanderings in a far-away region, a creature that is half woman and half snake steals the horses of Herakles. Herakles finds her, but she is only prepared to give the horses back to Herakles on the condition that he has sexual intercourse with her. Herakles impregnates the snake woman and takes back his horses. He then gives her his bow and belt and gives her instructions on how their children should found a nation in Scythia.

The following Aeolian-Homeric characteristics can be found in this short story: precious, special horses (A5); Herakles (A10); fatal marriages and romances (A14); local nature gods and nymphs (A19); huge, composite, evil monsters (A20); nymphs and gods as one’s mother or father (A22); precious, divine weapons (A23); mighty mothers, women, and goddesses (A24); bow and arrow (A26); and snakes (A31). In addition, it has the following Aeolian-Roman characteristics: the founding of cities and colonization (AR1); difficult wanderings in far-off places (AR4); revealed conditions for an expedition to succeed (AR6); and the son raised by an animal (AR7).

Four of the twenty-five hidden oral scopes are somewhat similar story types that are loosely connected with the evolving Aeolian Tradition, but clearly linked with Eastern traditions:26 the Destruction Story Type, the Monster Story Type, the Savior Story Type, and the Tele Story Type.27 In the Destruction Story Type, the city of wicked people who insulted the god(s) is destructed. The Monster Story Type is about a hero who kills a monster that plagues humanity. The Savior Story Type features a hero who gains an eternal life by overthrowing the reign of an evildoer that existed since the beginning of time. And in the Tele Story Type a hero who wanders in far-off places is destined to end the dominion of a wicked ruler. The Tele Story Type is an important origin of the Odyssey, next to the Mycenaean King Story Type and the European Narratives Role’s type-scene of the brave scout.

3.4. The Ionian Tradition

The Iliad and the Odyssey got fixed in the Ionian Tradition,28 which is hidden in the Iliad because it is so heavily mixed with other oral scopes. The Ionian Tradition is therefore the only Homeric tradition of which we know the artificial language in which it was usually performed, namely the Homeric artificial language. The Ionian Tradition was a very rich tradition, because it included other oral traditions as a subspecialty or role.

The ten most important oral characteristics of the Ionian Tradition (I1-I10) are the following: extraneous oral traditions/scopes as subspecialty; the materialism; the guest friendship (or ξενία); the house of nobles, servants, shepherds, heralds, and bards (or οἶκος); the system of epithets specific to the Ionian Tradition; Homeric similes; verbosity; the gods in their home on Olympos; type-scenes that repeat almost literally; and travel and travel matters.

Two characteristics are related to many others: materialism and guest friendship. With respect to materialism, almost everything in the Ionian Tradition is beautiful, shiny, well designed, and made of precious metals. This applies to the furniture in the rich houses, but ultimately also to the poem itself: The Ionian-Homeric bards preferred poetic, emotional, and peaceful scenes (I17). The lovely scenes on the shield of Achilles are typical examples (Iliad 18.541-605).

The ξενία provides us with the historical background of the Ionian Tradition. Travelers had the right to stay for thirty days in the house of their host and receive expensive guest gifts and a means of transportation to the next host. In return, the traveler could offer stories about his adventures and indications about where he lived, which enabled the host to travel abroad later on in his life.29 Without the ξενία, traveling would be too dangerous, because there were many pirates and slave sellers around.

The Ionian-Homeric system of epithets is the best evidence that the other three Homeric traditions must have existed in other artificial languages than the Homeric artificial language. Three kinds of subjects are provided with epithets in a natural manner: objects, animals, and women. Most often, they are described by how they look like or how they move. Extraneous subjects, from other Homeric traditions, imitate this system, such as περικαλλέα δίφρον (the very beautiful chariot) and πόδας ὠκὺς Ἀχιλλεύς (the swift-footed Achilles). While the epithet ‘περικαλλέα’ in ‘περικαλλέα δίφρον’ fits well in the materialistic descriptions of the Ionian Tradition, it does not correlate with the European Tradition. Nevertheless, the Ionian-Homeric system of epithets is ubiquitous in the Iliad: the passages colored by other Homeric traditions also contain such epithets. The best explanation is that the other Homeric traditions were continuously translated to the Ionian-Homeric artificial language during some period.

The Homeric similes prove the same point as the epithets. They are also present in the passages of all the Homeric traditions, while their content is related to the lovely (I17) and peaceful (I37) scenes of the Ionian Tradition, and its animal world (I81). Even though they occur often in the passages of the European War Role, they mostly do not contain any oral characteristics of it.

In the Iliad, many of the purest Ionian-Homeric passages (those that do not contain other Homeric traditions) are not essential for the story: they do not occur in a short content of the Iliad. For example, the following annotated passage about the gods closes Iliad 1 and can be omitted without impact on the rest of the story (Iliad 1.601-611):

ὣς30 τότε μὲν πρόπαν ἦμαρ (I98) ἐς ἠέλιον καταδύντα (98)

δαίνυντ᾽ (37, 38), οὐδέ τι θυμὸς ἐδεύετο δαιτὸς (38) ἐΐσης (9),

οὐ μὲν φόρμιγγος (12, 28, 32) περικαλλέος (2, 5) ἣν ἔχ᾽ Ἀπόλλων (12, 32),

Μουσάων (32) θ᾽ αἳ ἄειδον (28) ἀμειβόμεναι (28) ὀπὶ καλῇ (17, 37).

αὐτὰρ ἐπεὶ κατέδυ (98) λαμπρὸν (46) φάος (46) ἠελίοιο,

οἳ μὲν κακκείοντες ἔβαν οἶκον (4, 25, 64) δὲ ἕκαστος,

ἧχι ἑκάστῳ δῶμα (4) περικλυτὸς (22) ἀμφιγυήεις (22, 39)

Ἥφαιστος (84) ποίησεν (2) ἰδυίῃσι (46) πραπίδεσσι (46):

Ζεὺς δὲ πρὸς ὃν λέχος (9, 24, 25) ἤϊ᾽ Ὀλύμπιος (7, 22) ἀστεροπητής (7, 22),

ἔνθα πάρος κοιμᾶθ᾽ (98) ὅτε μιν γλυκὺς (5, 17) ὕπνος ἱκάνοι (7, 9, 39):

ἔνθα καθεῦδ᾽ ἀναβάς (9, 67), παρὰ (64) δὲ χρυσόθρονος (41) Ἥρη (9, 67).

Thus, the whole day (I98) until the sun went down (I98) they feasted (I37, I38). Neither did their hearts lack an equal portion (I38) of the banquet (I9, I38) nor the exceedingly (I2, I5) beautiful (I2, I5, I17) lyre (I12, I28, I32) of Apollo (I12, I32) and the Muses (I32) singing (I28) beautifully (I17), taking turns (I28, I37). But when the radiant (I46) light (I46) of the sun went down (I98) they went each to their own home (I25, I64) to sleep (I98) where (I39) for each the famous (I22), lame-footed (I22) Hephaistos (I84) had built a house (I4, I25) with (I39) skillful (I2, I46) craftsmanship (I2, I46). Zeus, the Olympian (I7, I22) lightning master (I7, I22), went to his bed (I9, I24, I25). Having gone up there (I64) he slept (I9, I67, I98), beside (I64) Hera (I9, I67) of the golden (I41) throne.31

The Ionian Tradition is more deeply rooted in the Odyssey, given that several chapters elaborate the practice of guest friendship in which both Telemachos and Odysseus are guests. Also traveling and seafaring are Ionian-Homeric characteristics that we find more in the Odyssey.

Finally, it is possible to distinguish three Ionian-Homeric roles in the Iliad: the Early Dramatic Role, the Achilles Role (or Late Dramatic Role), and the God Role.32 These roles are probably the result of a traditional practice to take turns during an alternating improvisation with bards who had different specialties. With respect to our Iliad a War Bard, a Narrative Bard, an Achilles Bard, and a God Bard can be distinguished.33 Blondé 2022, 107, hypothesizes that they improvised our Iliad together during a well-prepared event with sufficiently many memorizers and/or writers who could capture the performance in a fixed form, without delaying it.

Many passages in the Iliad betray the character of the four bards, as they respond to the narrative decisions that were taken by one of the other bards. For example, the Achilles Bard dislikes the existence of the Greek wall on the Trojan beach, even though it is essential for the War Bard and the Narrative Bard. Another example is that the Narrative Bard criticizes the chaotic development of the battle by the War Bard in Iliad 13 by immediately restoring order when he takes over at 13.723 by means of his favorite character Polydamas. The reproach against Hektor can be directly interpreted as a reproach against the War Bard. But the most spectacular interaction between two bards is the quarrel between the Narrative Bard and the Achilles Bard in Iliad 19. The Narrative Bard’s plan to develop the story with food and rest conflicts with the Achilles Bard’s desire to let Achilles take immediate revenge on the Trojans and Hektor. It is the Narrative Bard who wins the quarrel with a poetic intervention (Iliad 19.215 and further) that stresses the importance of poetic and narrative passages as a counterbalance to the many raw battle passages. An unsolved question is to which degree these four bards repeated the same interactions and quarrels each time they performed together.

3.5. Highlighted Result: Setting up the Army Before the Fight

The many results can too easily be dismissed as irrelevant by pointing out that many of them are controversial and/or hard to validate as sound. For this reason, one controversial but significant result is highlighted, namely the observation that the type-scene of setting up the army before the fight is highly traditional and closely associated with the rampart of earth and wood and the ditch on the Trojan beach. This is an important argument for the non-Greek European origin of the rampart. According to its references, it concerns the European-War characteristics E7 (the type-scene) and Es1 to Es23 (the 23 distinct stages of the type-scene) in the alphabetically-ordered characteristics sheet of the Homeric Traditions Apparatus. It is described in detail in Blondé 2019, pp. 86-92, where eight passages of 1.324 lines together (of which the catalogues in Iliad 2 take 444 lines) are referenced (p. 87).

In this type-scene the captain of the defending army shows up on the rampart (Es5), such that the bright glare of his armor (Es6) frightens the enemy. The charioteers drive via a bridge over the ditch (Es7) and line up the chariots along the ditch (Es10). The captain returns within the ramparts to sacrifice and pray (Es15) and the clan leader watches from the rampart (Es16). The last characteristic, after the battle igniting (Es22), is the fool who dies first (Es23).

A textbook example of this type-scene occurs at the beginning of a new day in the war (Iliad 11.1-83). The type-scene is of major importance for the architecture of Iliad 2, 3, 4 and 6. Nevertheless, its characteristics occur often distorted in our Iliad, which suggests that these are indeed old and traditional. For example, in one of the eight passages (Iliad 12.75-117), it is the Trojans who line up along the Greek ditch, even though this passage has several characteristics of the type-scene, including a formula about reining in the horses by the ditch (Es20; Iliad 11.47-48 = 12.84-85), the listing of warriors (Es11) in five groups and the fool (Asios) who dies first (Es23). A second example is that not the whole army crosses the ditch via a bridge, but that a single warrior – Diomedes – turns around and crosses the ditch with his horses, without any mention of a bridge (Iliad 8.255). A third example is that Athene kindles a fire above Achilles’ head to scare the Trojans (Iliad 18.206), which replaces the bright glare of the captains’ armor (Es6).

That the type-scene of setting up the army before the fight has had a severe influence on a long-standing fluid Iliad tradition, is apparent in Iliad 6.237-529.34 It is the return of the captain – Hektor – within the ramparts to sacrifice and pray (Es15) that must have been the initial kernel to which other oral characteristics have become attached later. The first of these were other thematic type-scenes of the European War Role: the warrior who does not fight (E6), the warrior in need and the helper (E11), the cowardly archer (E12), and the warrior who blames his companion (E13), all relating to Hektor and Paris. Only later did Helen and Andromache start to play a bigger role and with them the characteristics of the European Narrative Role and the Aeolian and Ionian Traditions. The reason why we can look back into the past so easily for this passage is that it must have been popular and therefore an indispensable part of an Iliad tradition throughout the ages.

While the core of the type-scene about setting up the army before the fight is compatible with a non-Greek European origin, there are some Greek characteristics that became associated with it. The centrally located ship of Odysseus is mentioned twice in relation with the ideal place from where a loud battle cry (Es9) can be shouted in both directions (Iliad 8.222 and Iliad 11.5). And the gods of war (Es13) Ares (Iliad 4.439 and Iliad 20.51), Eris (Iliad 11.1-83 and Iliad 20.48), and Athene (Iliad 2.446 and Iliad 4.439) incite the warriors more than once.

The passage Iliad 20.1-75 applies the type-scene to the Greek gods. Instead of gathering warriors in the stronghold (Es2), Zeus gathers the gods on Mount Olympos. After that, they divide in two camps – Greek versus Trojan – and line up among the human warriors. It is still the gods of war Athene and Ares who give out a loud battle cry (Es9). For Athene it is mentioned that she stands by the rampart and the ditch dug by the Greeks. The origin of this type-scene being applied to the Greek gods is most probably characteristic Es14: gods who choose a side. Normally only the gods of war choose a side, but this passage with all the gods serves the needs of a Greek audience.

An interesting find is that the famous Catalogue of Ships is part of the type-scene of setting up the army before the fight, namely characteristic Es11: listing leaders, regiments, and numbers.35 The number of ships that belong to each regiment, may once have been a number of chariots. The type-scene already starts at Iliad 2.434, which is 60 verses earlier than the beginning of the catalogue itself. These 60 verses contain many similes (I6), but in the gods of war (Es13), the aegis (Es12), lining up the army (Es10), the bright glare of the armor (Es6), the noise of the army (Es8), and the glorification of the leader (Es3), the European-War type-scene still shines through. We find Protesilaos in the Greek catalogue (Iliad 2.701) and Nastes in the Trojan catalogue (2.871-874) as those who die first or in a foolish manner (Es23). The Catalogue of Ships itself is also heavily colored by the Mycenaean Tradition, because of the many places and personal names (M13), the riches of the soil, typical of a place or city (M15), and the presence of digressions (M1) with the characteristics of the Mycenaean Tradition.

It may require some work to compare 1.324 lines on the presence of 23 oral characteristics, but the return on investment is great in terms of insight into the origins of the Iliad. This result shows that the rampart and the ditch built by the Greeks are more traditional than currently assumed and probably require a non-Greek, European origin. It also excludes many theories about the Catalogue of Ships and about the Iliad as a whole.