1. Introduction

Breast cancer is the most frequently diagnosed malignancy and the leading cause of cancer-related mortality among women worldwide [

1]. Its classification is defined by the immunohistochemical expression status of estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2). Among the subtypes, triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC)—which lacks ER, PR, and HER2 expression—accounts for approximately 15–20% of all cases and is characterized by high aggressiveness, early recurrence, and poor prognosis [

2,

3]. Despite recent advances in molecularly targeted therapies and antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs), standard treatment for TNBC still relies primarily on conventional cytotoxic agents such as anthracyclines and taxanes [

4]. However, intrinsic and acquired resistance to these drugs frequently occurs, leading to treatment failure and disease progression. Therefore, novel therapeutic strategies capable of overcoming chemoresistance and improving radiosensitivity remain an urgent unmet need.

POSTN is a secreted matricellular protein that regulates cell adhesion, migration, and tissue remodeling by interacting with extracellular matrix (ECM) components, integrins, cytokines, and proteases[

5,

6],It is physiologically expressed during embryonic development, wound healing, and tissue repair[

7] but aberrant overexpression of POSTN has been implicated in a variety of fibrotic and inflammatory diseases such as heart failure[

8] diabetic retinopathy[

9]and chronic inflammatory airway disorders [

10] In the cardiovascular system, POSTN has been shown to play a pivotal role in cardiac remodeling and myocardial repair following injury, where its excessive induction contributes to pathological fibrosis and heart failure progression (Katsuragi et al., 2004b).In particular, our group(

Taniyama et al.) demonstrated that POSTN promotes fibroblast activation and maladaptive cardiac remodeling via integrin-mediated signaling, establishing POSTN as a key regulator linking inflammation and fibrosis in the diseased heart.

In cancer, POSTN is mainly secreted by cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) within the tumor microenvironment (TME), where it promotes extracellular matrix deposition, epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), cancer stemness, and metastatic dissemination [

12,

13].

High POSTN expression is strongly correlated with poor clinical outcome, particularly in TNBC[

14]..

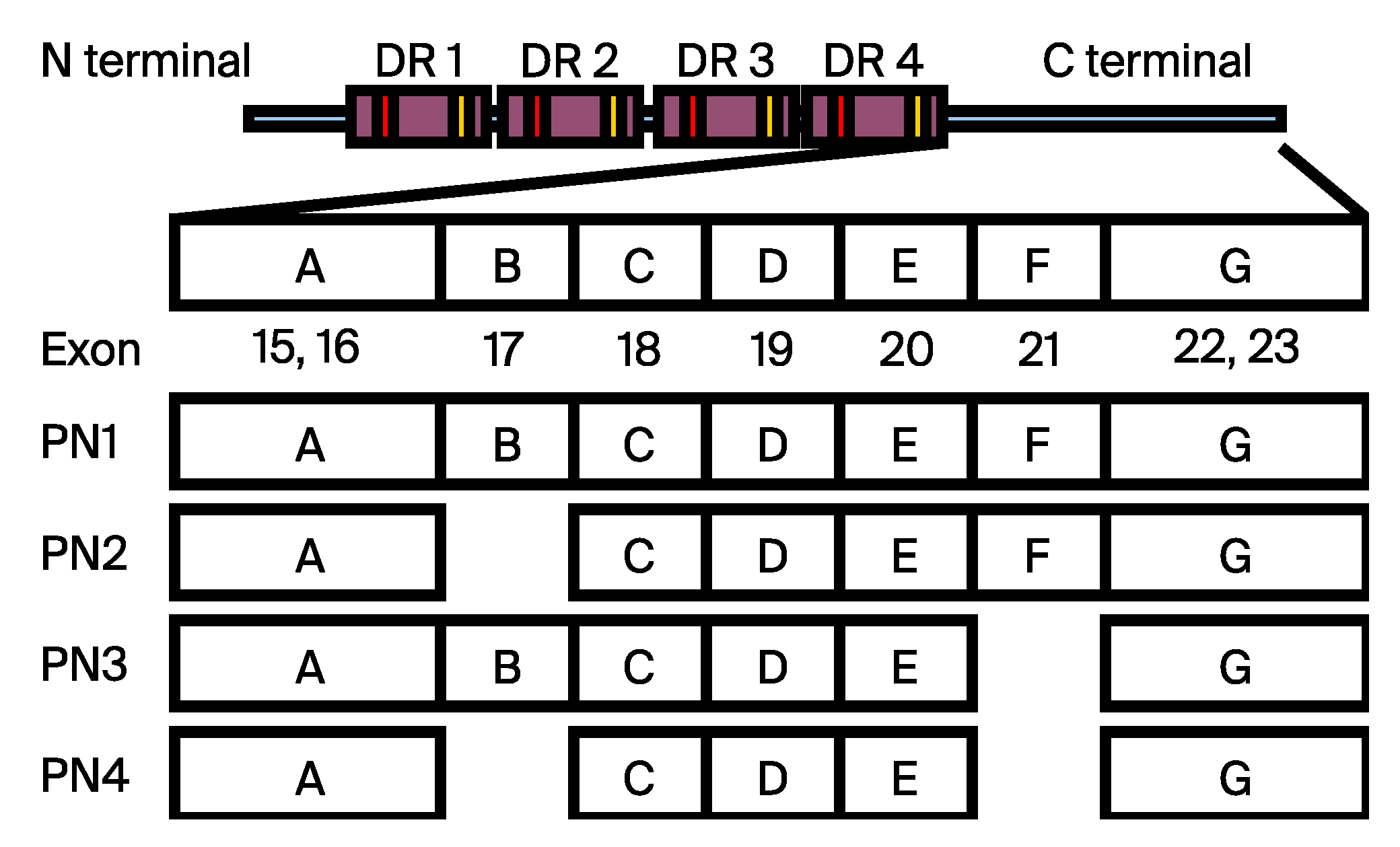

Human POSTN undergoes alternative splicing at exons 17 and 21, generating four major isoforms—PN1 (full-length), PN2 (Δexon 17), PN3 (Δexon 21), and PN4 (Δexons 17 and 21) [

15,

16]. Notably, isoforms containing exon 21 (PN1 and PN2) are preferentially expressed under pathological conditions such as tumorigenesis, whereas exon 21-deficient isoforms (PN3 and PN4) are predominant in normal tissues [

17,

18,

19]. Among these, POSTN variants containing exon 17 and exon 21 have recently drawn attention as pathological isoforms that drive malignant phenotypes in breast cancer. Notably, [

20].demonstrated that a short fragment encompassing exon 17 is essential for tumor growth and metastasis. In addition [

21]further reported that pathological POSTN splicing variants are highly upregulated in the stroma and cancer cells of breast tumors and that their suppression can attenuate tumor progression . Moreover,

Balbi et al. showed that an exosome-carried short POSTN isoform can induce cardiomyocyte proliferation, highlighting the functional diversity of POSTN variants beyond oncology [

22]. Together, these findings underscore the crucial role of POSTN splicing diversity in disease biology and its potential as a therapeutic target.

Our pivotal study by[

15] first demonstrated that POSTN blockade using a neutralizing antibody overcame paclitaxel (PTX) resistance in breast cancer by restricting the expansion of mesenchymal-like tumor subpopulations. Importantly, that study also revealed that chemotherapy—including PTX, doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide—induced strong POSTN expression in both tumor cells and surrounding stromal fibroblasts, accompanied by enrichment of mesenchymal tumor populations and loss of epithelial markers. This indicated that POSTN upregulation is not limited to taxane treatment but represents a common adaptive response to various cytotoxic stresses, which reinforces EMT and stromal remodeling within the TME. These findings provided compelling evidence that POSTN plays a central role in therapy-induced selection of aggressive, EMT-associated tumor cells and the development of chemoresistance. However, it remains unclear whether selective targeting of the exon 21–containing POSTN isoforms can directly modulate therapy-induced stromal remodeling and overcome treatment resistance in aggressive breast cancer. Therefore, in this study, we sought to investigate whether blockade of POSTN exon 21 enhances the therapeutic efficacy of radiation and standard chemotherapeutic agents by suppressing EMT within the tumor microenvironment. This work aims to clarify the mechanistic contribution of pathological POSTN variants to therapy response and to determine whether exon 21 represents a viable therapeutic target in breast cancer.

Figure 1.

Domain structure and alternative splicing isoforms of POSTN.

Figure 1.

Domain structure and alternative splicing isoforms of POSTN.

POSTN consists of an N-terminal EMI domain followed by four tandem fasciclin-like (FAS1) repeats, and a C-terminal region encoded by exons 15–23. The C-terminal region undergoes alternative splicing that generates four major isoforms: PN1 (full-length), PN2 (lacking exon 17), PN3 (lacking exon 21), and PN4 (lacking both exons 17 and 21). Pathological isoforms containing exon 21 (PN1 and PN2) are enriched in tumor tissues and promote epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), matrix remodeling, and chemoresistance, whereas the physiological isoform PN4 lacks these exons and is predominantly expressed in normal tissues. This schematic illustration was modified from our previous publication ([

19]) with permission.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

MCF10DCIS.com (Asterand Bioscience, Detroit, MI, USA), and ZR-75-1 (CRL-1500, ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) breast cancer cell lines were used in this study. Cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan; Cat. No. 26252-94) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Grand Island, NY, USA) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Grand Island, NY, USA). All cells were maintained at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO₂, and the medium was replaced every 2–3 days.

2.2. Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cultured cells or tissue samples according to previously described protocols. RNA quantity and integrity were verified prior to reverse transcription. Complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis was carried out using the SuperScript™ III First-Strand Synthesis Kit (Cat. No. 18080051, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Grand Island, NY, USA) in the presence of an RNase inhibitor, following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Quantitative analysis was performed on the Applied Biosystems ViiA™ 7 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Grand Island, NY, USA). In each assay, mouse glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) served as the internal reference gene.

GAPDH (5′-GAAGCAGGCATCTGAGGGC-3′, 5′-TTGAAGTCGCAGGAGACAACC-3′)

hPN1(5′-GTGATTGAAGGCAGTCTTCAGCC-3′,5′-CTCCCTGAAGCAGTCTTTTA-3′), hPN2 (5′-AATCCCCGTGACTGTCTATAGACC-3′, 5′-CTCCCTGAAGCAGTCTTTTA-3′),

hPN3 (5′-GTGATTGAAGGCAGTCTTCAGCC-3′, 5′-TCCTCACGGGTGTGTCTTCT-3′),

hPN4(5′-AATCCCCGTGACTGTCTATAGACC-3′,5′-TCCTCACGGGTGTGTCTTCT-3′), CDH1 (5′-TGCCCAGAAAATGAAAAAGG-3′, 5′-GTGTATGTGGCAATGCGTTC-3′), SNAI1 (5′-AAGATGCACATCCGAAGCC-3′,5′-CGCAGGTTGGAGCGGTCAGC-3′), SNAI2 (5′-AAGCATTTCAACGCCTCCAAA-3′, 5′-GGATCTCTGGTTGTGGTATGACA-3′), TWIST1 (5′-AAGAGGTCGTGCCAATCAG-3′,5′-GGCCAGTTTGATCCCAGTAT-3′), ZEB1 (5′-GATGATGAATGCGAGTCAGATGC-3′,5′-ACAGCAGTGTCTTGTTGTTGTAG-3′),

2.3. In Vivo Mouse Experiment

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the institutional guidelines for animal care and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Animal Experiment Facility, Osaka University School of Medicine (Approval No. 04-101-008 ). Female CAnN.Cg-Foxn1<nu>/CrlCrlj (BALB/c-nu) mice (6–8 weeks old; Charles River Laboratories, Yokohama, Japan) were maintained under specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions with ad libitum access to food and water and acclimatized for at least one week prior to experimentation. For orthotopic xenograft establishment, MCF10DCIS cells (5 × 10⁶ cells) were suspended in 100 μL of a 1:1 mixture of serum-free DMEM/F12 medium and Matrigel (Corning) and injected into the fourth mammary fat pads on both sides (bilateral implantation). Each mouse thus carried two independent tumors, and five mice (n = 5) were used per treatment group. Tumor growth was monitored twice weekly using digital calipers, and tumor volume was calculated using the formula (length × width²)/2. When the mean tumor volume reached approximately 100 mm³, mice were randomly assigned to treatment groups. PN-21Ab was administered via tail vein injection (intravenously, i.v.) at 10 mg/kg twice per week, while the control group received vehicle (PBS).

For combination therapy studies, the following agents were administered according to their respective regimens:

– Eribulin (Halaven®): 0.5 mg/kg, i.v., once per week The drug was generously provided by Eisai Co., Ltd. under a Material Transfer Agreement (MTA).

– Vinorelbine: 16 mg/kg, i.v., twice per week for one cycle

– Doxorubicin: 10 mg/kg, i.v., twice per week for one cycle

– 5-Fluorouracil (5-FU): 60 mg/kg, intraperitoneally (i.p.), once per week

For the radiation combination group, a single 9 Gy X-ray dose was delivered locally to the tumor site using an X-ray irradiator (MX-160Labo; mediXtec Corporation, Japan).

2.4. Anti-Human POSTN Exon 21 Antibody

To generate a mouse monoclonal antibody specific to exon 21 of human POSTN, the exon 21 peptide was synthesized by BIO MATRIX RESEARCH (Chiba, Japan). Mice were immunized with the synthesized peptide, and the antibody was produced according to previously described methods [

23]. The resulting monoclonal antibody, designated PN-21Ab, specifically recognizes the exon 21 region of human POSTN.

2.5. Statistical Analysis

All quantitative data are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism version 10.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Differences among multiple experimental groups were assessed using the Mann–Whitney U-test, while comparisons between two matched groups were analyzed by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test. Statistical significance was defined as a p value less than 0.05.

2.6. Ethical Statement

All animal procedures were performed in compliance with the institutional regulations for animal experimentation and were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Animal Experiment Facility, Osaka University School of Medicine (Approval No. 04-101-008 ).All experiments conformed to the national standards and recommendations specified in the following guidelines:– Guidelines for Animal Experiments in Research Institutions (Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan);– Guidelines for Animal Experiments in Research Institutions (Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan); and– Guidelines for the Proper Conduct of Animal Experiments (Science Council of Japan).In this study, female CAnN.Cg-Foxn1<nu>/CrlCrlj (BALB/c-nu) mice (6–8 weeks old) obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Yokohama, Japan) were used. All possible measures were taken to minimize discomfort and to reduce the number of animals used.

3. Results

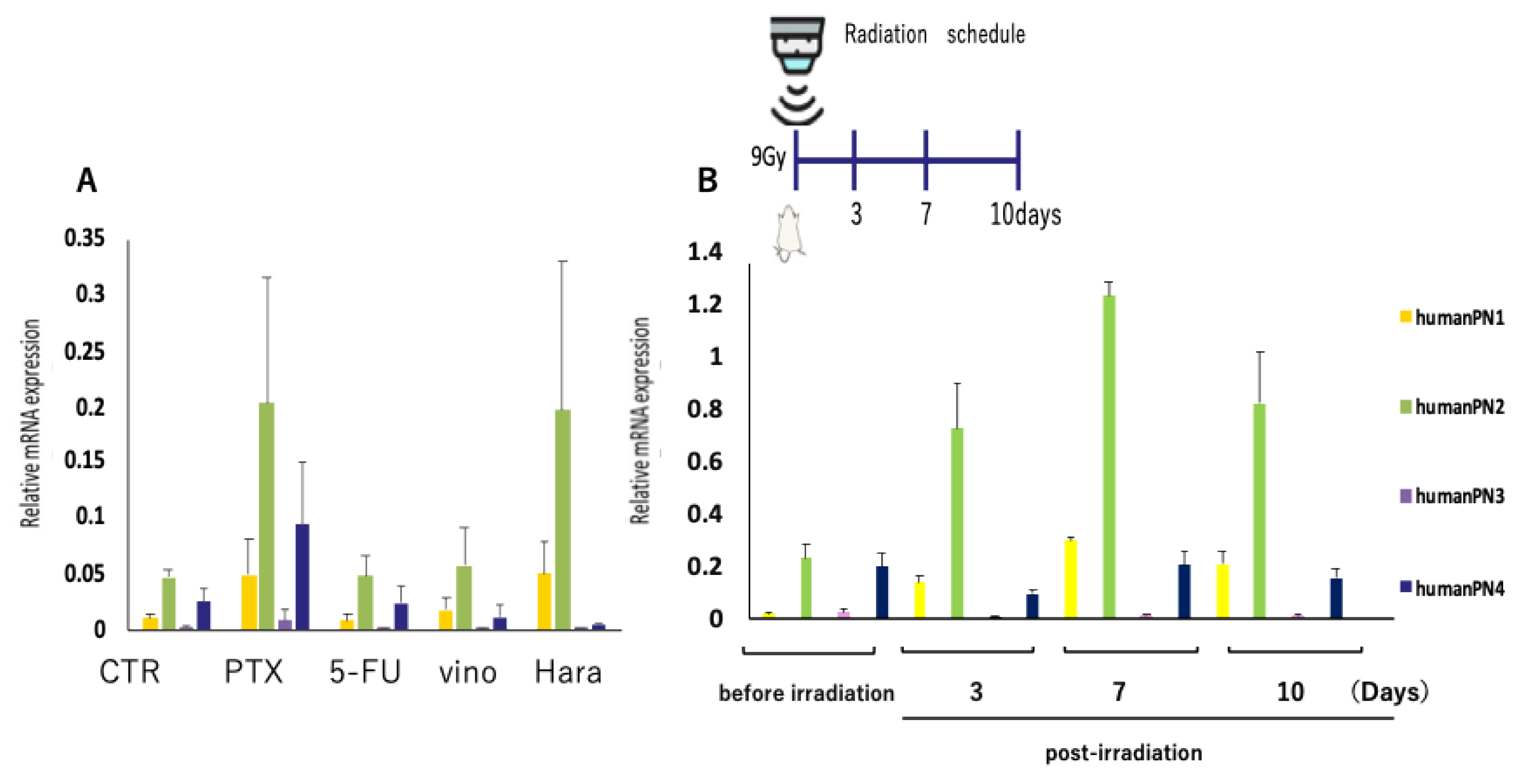

To investigate whether conventional cancer therapies influence POSTN splicing,

MCF10DCIS xenograft–bearing mice received a single dose of paclitaxel (30 mg/kg, i.v.), eribulin (Halaven®, 0.5 mg/kg, i.v.), vinorelbine (16 mg/kg, i.v.), doxorubicin (10 mg/kg, i.v.), or 5-fluorouracil (60 mg/kg, i.p.).

Tumors were collected 3 days after treatment, and mRNA expression of human POSTN isoforms (PN1–PN4) was quantified by qRT-PCR.

As shown in

Figure 2A, expression of the exon 21–containing PN2 isoform was markedly upregulated in the paclitaxel and eribulin groups, while only minor increases were observed following 5-FU or vinorelbine treatment.

PN3 and PN4 isoforms remained at basal levels under all conditions. This conclusion is supported by the known mechanisms of action of eribulin and paclitaxel, both of which modulate microtubule dynamics and can influence cellular plasticity, EMT induction, and stromal remodeling within the tumor microenvironment. These drug-induced biological changes are consistent with the observed increase in POSTN expression following treatment.

To further examine the kinetics of PN2 induction, tumors were harvested 0, 3, 7, and 10 days after 9 Gy irradiation (

Figure 2B).

PN2 expression began to increase by day 3, peaked strongly at day 7, and declined to baseline by day 10.

These results indicate that cytoskeletal and radiation-induced stress transiently enhance PN2 expression, suggesting that the exon 21–containing POSTN variant may act as a dynamic regulator of extracellular matrix remodeling in response to therapy-induced tissue injury.

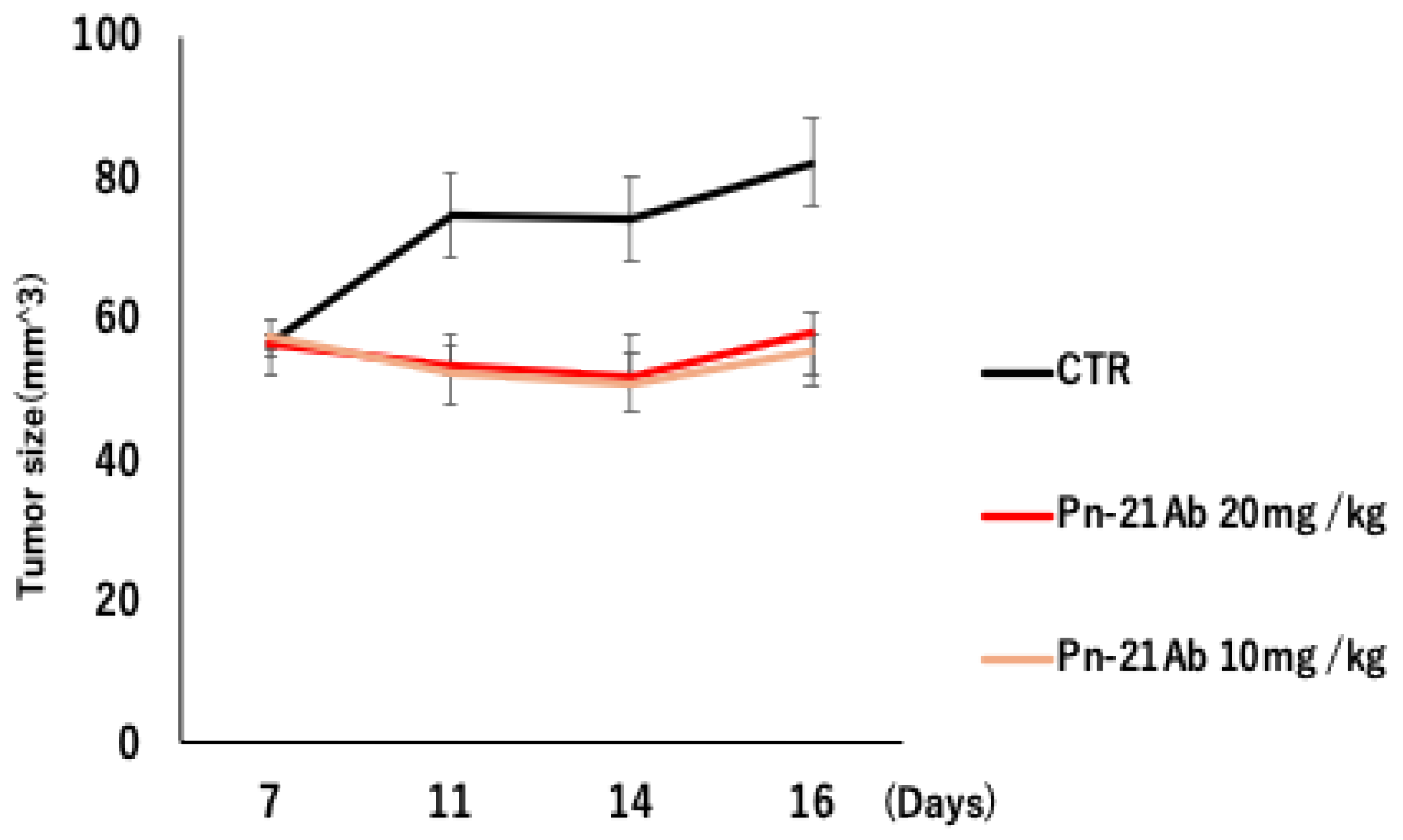

ZR75-1 xenograft-bearing mice were treated with PN-21Ab (10 mg/kg or 20 mg/kg, i.v., twice per week) or control(CTR).

Tumor growth was modestly suppressed in both PN-21Ab groups compared with vehicle, with similar efficacy between the two doses.

Data represent mean ± SD (n = 5); p < 0.05 vs. CTR (Mann–Whitney U test).

3.1. Antitumor Activity of PN-21Ab in Luminal Breast Cancer Model (ZR75-1)

To evaluate whether PN-21Ab exhibits antitumor activity in non-TNBC breast cancer, we examined its efficacy in a ZR75-1 xenograft model, which represents a luminal-type breast cancer with low POSTN expression.

Mice bearing ZR75-1 tumors were treated with PN-21Ab at 10 mg/kg or 20 mg/kg (i.v., twice per week) or control.

As shown in

Figure 3, both PN-21Ab treatment groups demonstrated a modest but consistent inhibition of tumor growth compared with the control, with no significant dose-dependent difference between 10 mg/kg and 20 mg/kg.

Figure 3.

Antitumor activity of PN-21Ab in ZR75-1 xenograft model.

Figure 3.

Antitumor activity of PN-21Ab in ZR75-1 xenograft model.

Figure 3.

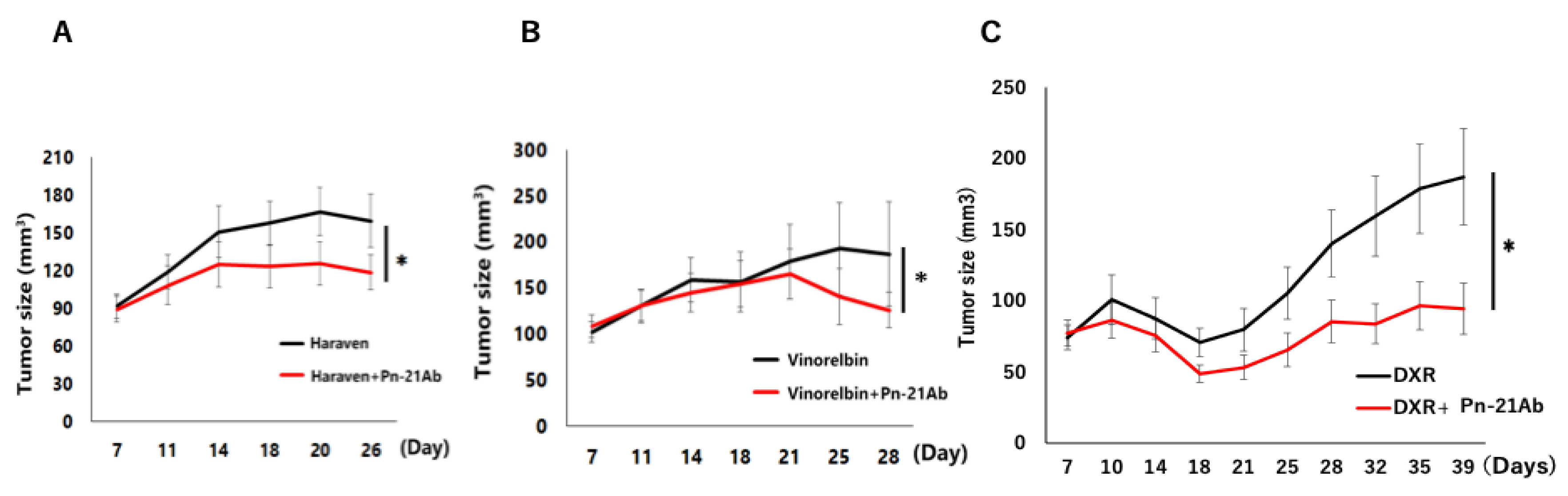

PN-21Ab enhances the antitumor efficacy of standard chemotherapeutic agents in MCF10DCIS xenografts. (A) Tumor growth curves following treatment with eribulin (Halaven®, 0.5 mg/kg, i.v., once per week) ± PN-21Ab (10 mg/kg, i.v., twice per week). (B) Tumor growth curves following treatment with vinorelbine (16 mg/kg, i.v., twice per week) ± PN-21Ab. (C) Tumor growth curves following treatment with doxorubicin (10 mg/kg, i.v., twice per week) ± PN-21Ab. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 5). *p < 0.05 vs. monotherapy (Mann–Whitney U test).

Figure 3.

PN-21Ab enhances the antitumor efficacy of standard chemotherapeutic agents in MCF10DCIS xenografts. (A) Tumor growth curves following treatment with eribulin (Halaven®, 0.5 mg/kg, i.v., once per week) ± PN-21Ab (10 mg/kg, i.v., twice per week). (B) Tumor growth curves following treatment with vinorelbine (16 mg/kg, i.v., twice per week) ± PN-21Ab. (C) Tumor growth curves following treatment with doxorubicin (10 mg/kg, i.v., twice per week) ± PN-21Ab. Data represent mean ± SD (n = 5). *p < 0.05 vs. monotherapy (Mann–Whitney U test).

These findings indicate that PN-21Ab exerts mild antitumor effects even in a POSTN-low, luminal-type tumor model, suggesting that POSTN blockade may confer basal inhibitory activity independent of high POSTN expression levels.

This result further supports the therapeutic potential of PN-21Ab across different breast cancer subtypes, while its strongest efficacy was observed in POSTN-high TNBC models.

3.2. PN-21Ab Synergistically Enhances the Antitumor Effects of Microtubule-Targeting and Cytotoxic Agents

To assess whether POSTN blockade enhances the efficacy of standard chemotherapeutics MCF10DCIS xenograft–bearing mice were treated with eribulin (Halaven®, 0.5 mg/kg, i.v., once per week), vinorelbine (16 mg/kg, i.v., twice per week), or doxorubicin (10 mg/kg, i.v., twice per week),

either alone or in combination with PN-21Ab (10 mg/kg, i.v., twice per week).

Tumor volumes were measured twice weekly for up to 4 weeks.

As shown in

Figure 3A–C, the combination of PN-21Ab with each chemotherapeutic agent resulted in significantly greater tumor growth inhibition compared with monotherapy.

In the eribulin group (

Figure 3A), combination treatment reduced tumor volume by approximately 30% relative to eribulin alone on day 26 (

p < 0.05).

Similarly, vinorelbine + PN-21Ab (

Figure 3B) suppressed tumor growth by 40–45% versus vinorelbine alone at day 28 (

p < 0.05).

The combination with doxorubicin (

Figure 3C) also produced a marked and sustained inhibition, leading to significantly smaller tumors after 35–39 days (

p < 0.05).

These findings demonstrate that PN-21Ab potentiates the therapeutic efficacy of both microtubule-targeting and DNA-damaging agents,

suggesting that blockade of exon 21–containing POSTN (PN2) may disrupt stromal interactions and enhance tumor chemosensitivity within the tumor microenvironment.

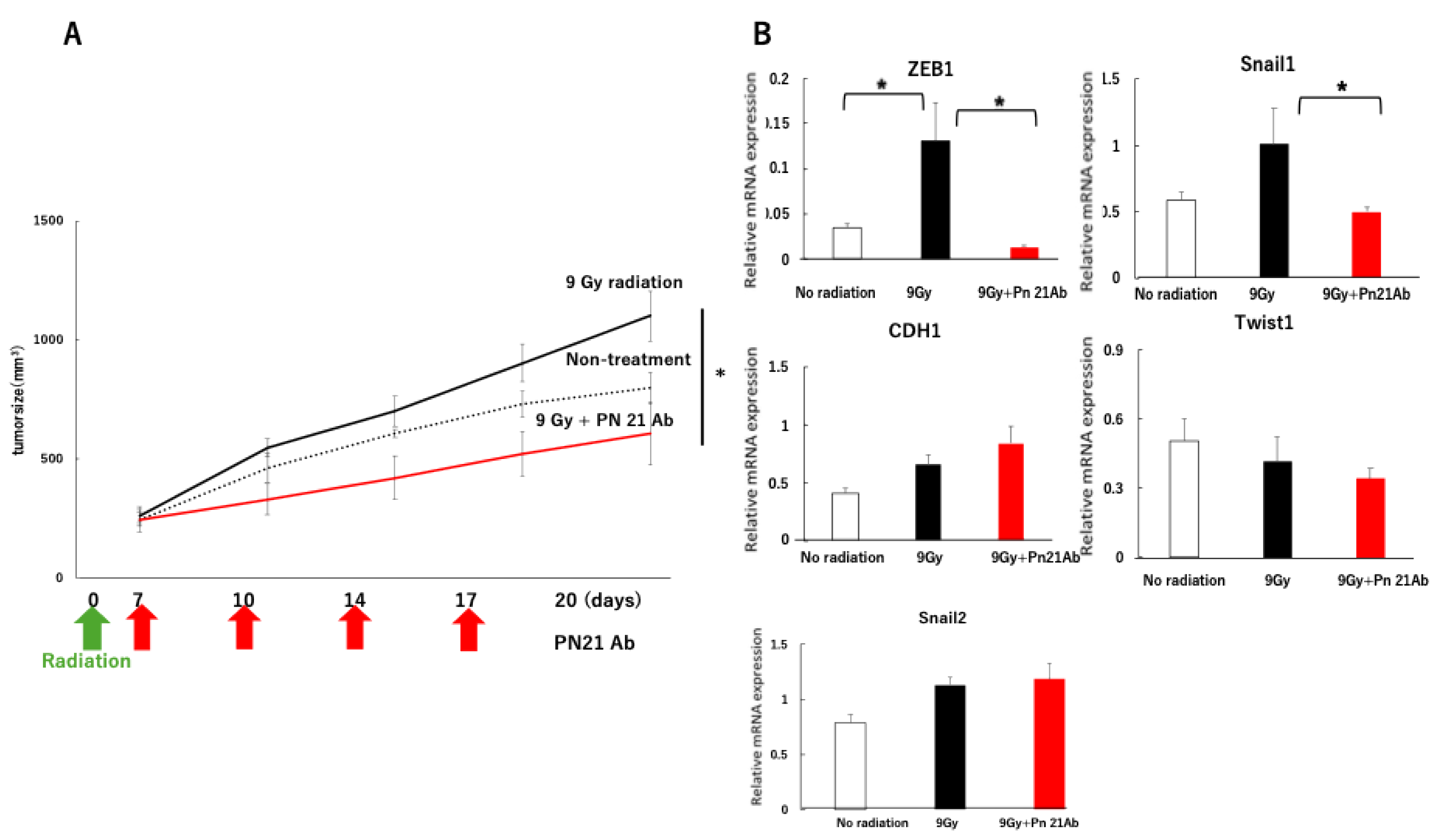

Radiation alone markedly induced the EMT-related transcription factors snail1 and ZEB1, whereas co-administration of PN-21Ab significantly suppressed their expression (p < 0.05).

In contrast, Twist1, snail2 (Slug), and CDH1 showed no significant changes among the groups, suggesting that PN-21Ab selectively inhibits radiation-induced activation of specific EMT regulators rather than globally affecting epithelial or mesenchymal gene expression.

Data are presented as mean ± SD (n = 5); p < 0.05 compared with radiation alone (Mann–Whitney U test).

3.3. PN-21Ab Enhances the Antitumor Efficacy of Radiation and Suppresses EMT Activation

To evaluate whether POSTN blockade enhances the therapeutic effect of radiation and inhibits epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT), MCF10DCIS xenograft–bearing mice were treated with PN-21Ab (10 mg/kg, i.v., twice per week) following a single 9 Gy X-ray irradiation.

As shown in

Figure 4A, the combination of PN-21Ab with radiation significantly suppressed tumor growth compared with radiation alone (p < 0.05).

At the molecular level (

Figure 4B–E), radiation alone strongly induced the expression of snail1 and ZEB1, both of which are key transcriptional regulators of EMT.

In contrast, co-administration of PN-21Ab markedly reduced snail1 and ZEB1 expression to near-baseline levels (p < 0.05), while Twist1 and snail2 (Slug) remained unchanged.

These findings indicate that PN-21Ab selectively suppresses radiation-induced EMT activation through inhibition of the snail1–ZEB1 axis.

Taken together, POSTN blockade contributes to improved tumor control after irradiation through both direct radio sensitization and attenuation of EMT-associated plasticity within the tumor microenvironment

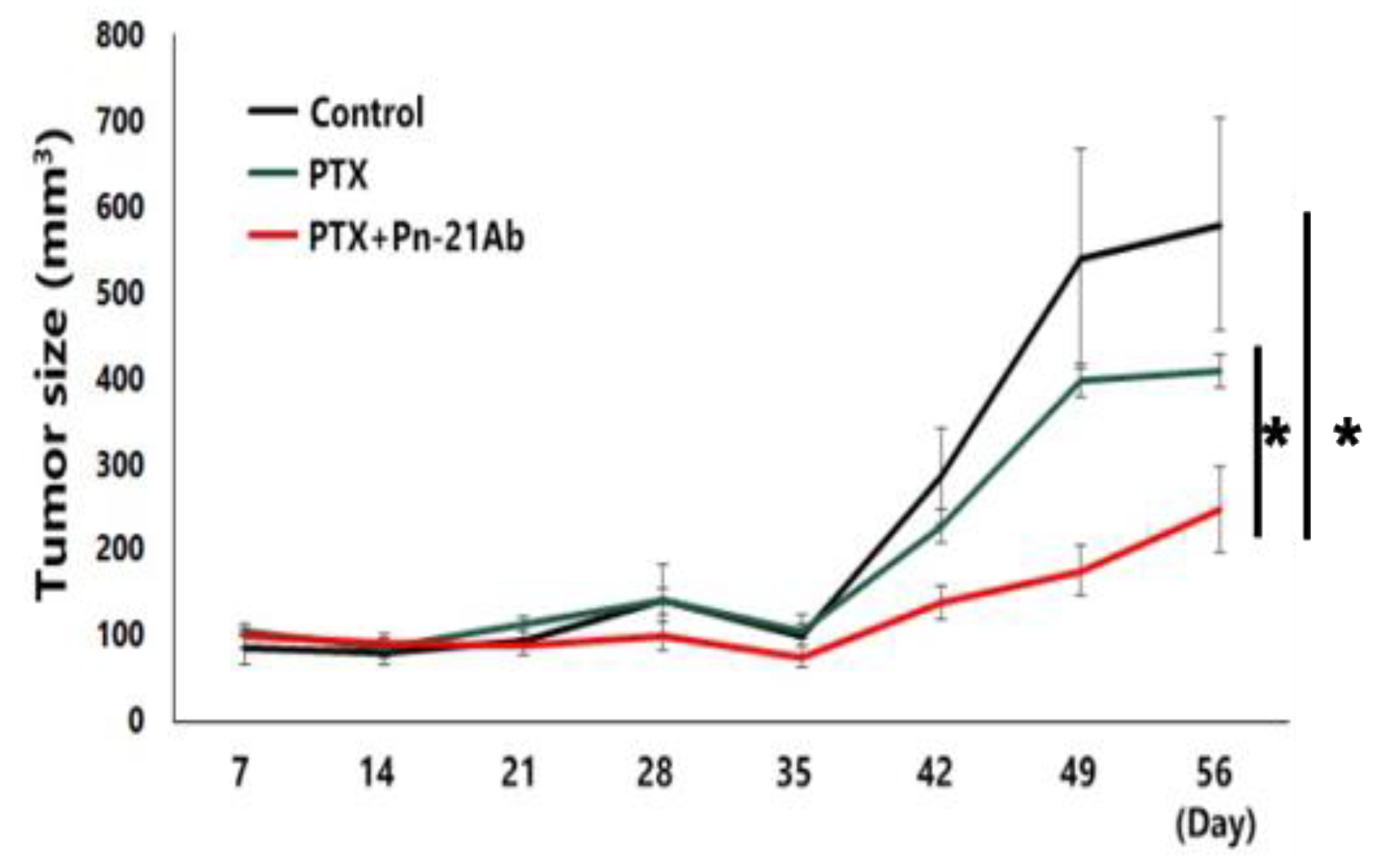

As shown in

Figure 5, PTX monotherapy moderately inhibited tumor growth compared with the control group; however, the combination of PTX with PN-21Ab exhibited a markedly enhanced antitumor effect (

p < 0.05).

By day 56, tumors in the combination group remained significantly smaller than those in either control or PTX-alone groups. These data further support that POSTN blockade by PN-21Ab potentiates the efficacy of microtubule-targeting chemotherapeutics in aggressive TNBC models, consistent with the results observed in MCF10DCIS xenografts (

Figure 3).

Tumor growth curves of MDA-MB-231 xenograft-bearing mice treated with PTX (30 mg/kg, i.v., once per week) with or without Pn-21Ab (10 mg/kg, i.v., twice per week).

The combination group (PTX + PN-21Ab) exhibited a significantly stronger antitumor effect compared with PTX monotherapy (p < 0.05).

Data are expressed as mean ± SD (n = 5).

To further confirm the synergistic antitumor activity of PN-21Ab in another triple-negative breast cancer model, we next evaluated its combination with paclitaxel (PTX) in MDA-MB-231 xenografts. Mice were treated with PTX (30 mg/kg, i.v., once per week) with or without PN-21Ab (10 mg/kg, i.v., twice per week), and tuFigmor growth was monitored for 8 weeks.

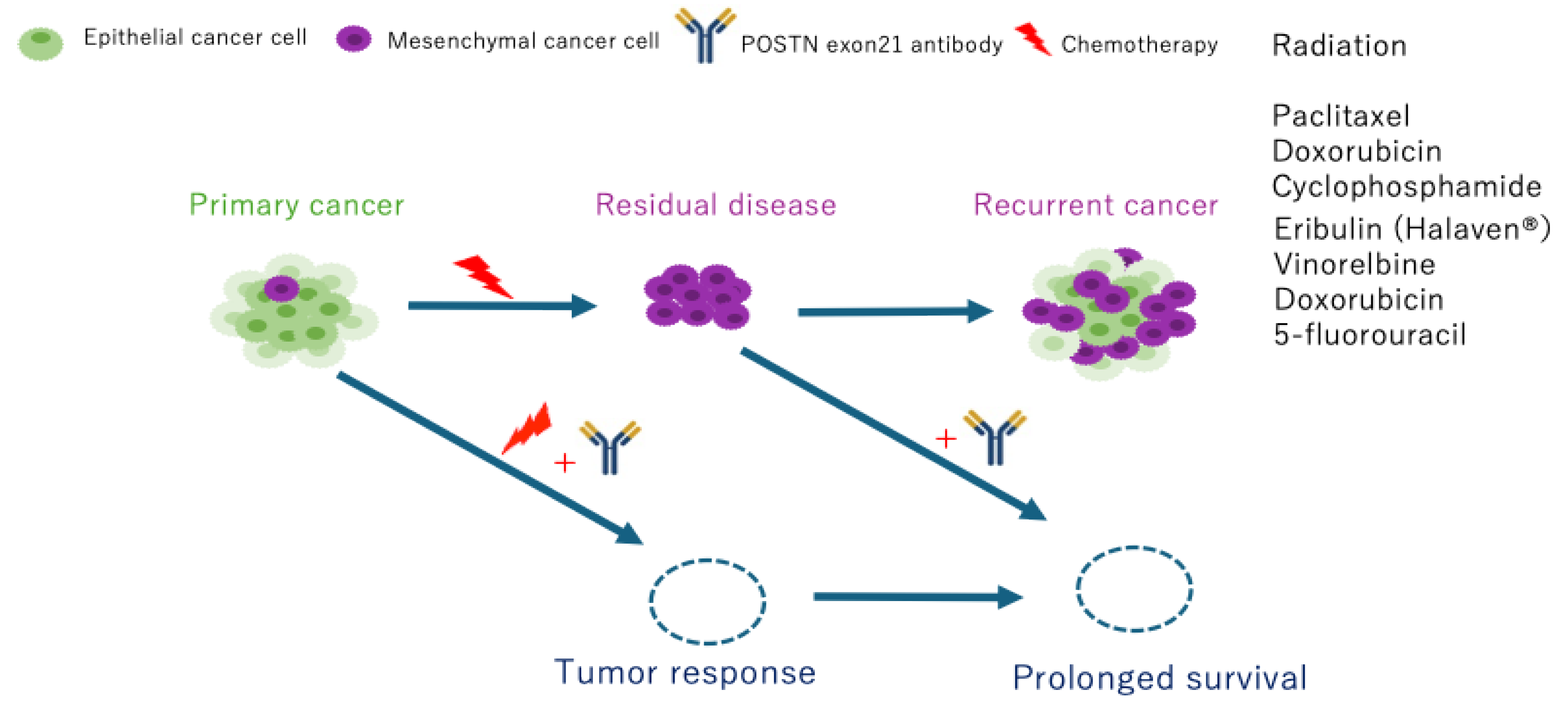

Figure 6.

Conceptual Framework of How POSTN exon 21 Blockade Improves Treatment Outcomes.

Figure 6.

Conceptual Framework of How POSTN exon 21 Blockade Improves Treatment Outcomes.

4. Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated that selective targeting of POSTN exon 21 by the monoclonal antibody PN-21Ab significantly enhances the therapeutic efficacy of both radiation and standard chemotherapeutic agents in breast cancer models. PN-21Ab exhibited potent combinatorial effects with microtubule-targeting drugs such as eribulin, vinorelbine, and paclitaxel, as well as with the DNA-damaging agent doxorubicin. Importantly, PN-21Ab also suppressed radiation-induced epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) and maintained epithelial characteristics within the tumor microenvironment (TME). These findings highlight the functional importance of the exon 21-containing POSTN isoform (PN2) as a dynamic mediator of therapy-induced stromal remodeling and treatment resistance [

24,

25].

POSTN is well recognized as a matricellular component of the TME that promotes tumor progression, EMT, and metastasis through integrin-mediated signaling and extracellular matrix (ECM) organization [

26,

27,

28]. Alternative splicing of POSTN generates multiple isoforms with distinct biological functions. Among these, exon 21-containing variants (PN1 and PN2) are preferentially expressed under pathological conditions, including cancer and fibrosis [

19,

20,

21,

23,

29,

30,

31,

32]. The present study revealed that chemotherapy and radiotherapy transiently increased PN2 mRNA expression, particularly after treatment with eribulin, paclitaxel, or irradiation. This conclusion is supported by the known mechanisms of action of eribulin and paclitaxel, both of which modulate microtubule dynamics and influence cellular plasticity, EMT/MET transitions, and stromal remodeling within the tumor microenvironment. In particular, eribulin has been shown to reverse EMT and induce MET in breast cancer models in vitro and in vivo [

33,

34]. Paclitaxel similarly modulates microtubule stability and has been reported to promote EMT-like changes and enhance cellular stress responses .[

35] These drug-induced biological changes are consistent with the observed increase in POSTN expression following treatment. This suggests that therapy-induced stress activates POSTN splicing toward the exon 21-containing isoform, thereby reinforcing tumor–stroma interactions that facilitate survival and repair mechanisms following cytotoxic injury [

36,

37].

Consistent with this hypothesis, blockade of the exon 21 region by PN-21Ab attenuated such adaptive responses and sensitized tumors to both cytotoxic and radiation treatments [

38]. The suppression of SNAIL1 and ZEB1 expression, together with restoration of E-cadherin (CDH1), indicates that PN-21Ab mitigates radiation-induced EMT [

39,

40,

41]. Since EMT contributes to stemness acquisition, immune evasion, and metastatic dissemination, inhibition of EMT by POSTN blockade may represent a crucial mechanism underlying the observed therapeutic synergy [

42,

43,

44].

Notably, PN-21Ab also exhibited modest but consistent antitumor activity in the luminal-type ZR75-1 model, which expresses relatively low levels of POSTN. This suggests that POSTN blockade exerts basal inhibitory effects on tumor–stromal signaling even in POSTN -low contexts, although its maximal efficacy is expected in POSTN-high tumors such as triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) [

30,

45,

46]. We selected paclitaxel rather than eribulin for the MDA-MB-231 in vivo experiment because paclitaxel is one of the most widely used first-line chemotherapeutic agents for triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), including MDA-MB-231–like basal-type tumors. The primary objective of this experiment was to evaluate whether POSTN exon 21 blockade enhances the efficacy of a representative frontline cytotoxic agent under clinically relevant conditions. Although eribulin also targets microtubules, it is generally administered in later-line settings, and its distinct effects on EMT reversal and stromal remodeling have already been demonstrated in our previous studies. Therefore, paclitaxel was selected to assess the baseline combinatorial potential of PN-21Ab in an established TNBC model, while eribulin-based combinations will be explored in future investigations. Taken together, these findings support the notion that PN-21Ab has broad therapeutic applicability across molecular subtypes of breast cancer, with potential for patient stratification based on POSTN isoform expression [

19,

20,

23].

From a translational perspective, POSTN targeting offers several advantages. Unlike conventional cytotoxic drugs, PN-21Ab acts on the tumor microenvironment rather than directly on cancer cells, minimizing systemic toxicity while enhancing the efficacy of existing therapies [

23]. The antibody’s selectivity for exon 21-containing isoforms allows precise intervention in pathological POSTN signaling while sparing physiological isoforms required for normal tissue homeostasis [

21,

23]. Furthermore, our results suggest that PN2 expression may serve as a predictive biomarker for treatment response and could be incorporated into companion diagnostic assays in future clinical studies.

In conclusion, selective inhibition of POSTN exon 21 by PN-21Ab effectively overcomes therapy-induced stromal resistance and EMT activation, thereby improving the efficacy of both chemotherapy and radiotherapy in breast cancer. These findings provide preclinical evidence supporting the development of PN-21Ab as a first-in-class stromal-targeted antibody for combination therapy in POSTN -high breast cancers, particularly TNBC [

21,

23,

42,

43]. Further clinical translation, including biomarker-guided patient selection and pharmacodynamic evaluation of POSTN isoforms, will be essential to realize its full therapeutic potential.

5. Patents

The patent of the Ex21 antibody belongs to Osaka University and Periotherapia Co., which has the priority negotiation right.

Author Contributions

K.S. (Kana Shibata): study conception and design, collection and assembly of data, data analysis and interpretation, and manuscript writing. N.K. (Nobutaka Koibuchi), N.K. (Naruto Katsuragi), F.S. (Fumihiro Sanada), and T.Y. (Tetsuhiro Yoshinami): study conception and design, collection and assembly of data, and data analysis and interpretation.Y.T. (Yasuo Tsunetoshi), Y.K. (Yuko Kanemoto), and S.I. (Shoji Ikebe): collection and assembly of data. K.Y. (Koichi Yamamoto), R.M. (Ryuichi Morishita), and K.S. (Kenzo Shimazu): study conception and design. Y.T. (Yoshiaki Taniyama): study conception and design, data analysis and interpretation, and final manuscript approval. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (2024–2029, Grant Number 24K11740) and the START Project of the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT, Japan; Funding Number 12103677) awarded to Y.T. (Yoshiaki Taniyama).In addition, this work was supported by a JSPS KAKENHI Grant (Grant Number JP24K11764) and a Grant-in-Aid for Early-Career Scientists (Grant Number JP23K14522) as well as a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (Grant Number C25K10681, 2025–2028) — all awarded to K.S. (Kana Shibata). This research was also partially supported by the Drug Discovery Eco-Venture Program (Grant Number 24qfb127004j0001 25qfb127004j0002 ) of MEXT, Japan, which promotes academia–industry collaboration for the development of innovative biologics and antibody therapeutics.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the protocols approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of The University of Osaka (Approval No. 04-101-007).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Y. Taniyama, upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Hideyuki Suzuki (Oriental Bio service, Inc.) for his valuable advice and technical assistance regarding radiation experiments. We also acknowledge Ms. Ryoko Nakagawa, Ms. Terumi Matsuyama, Ms. Satoko Kagiya, Mr. Tadayoshi Maekawa, and Mr. Yutaro Ishikawa in the Department of Advanced Molecular Therapy, Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka University, for their excellent technical assistance. We are also grateful to the Animal Experiment Facility, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Osaka, and to Mr. Takashi Enjyoji (Center for Medical Research and Education, Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Osaka) for their support with gene expression analysis. We also thank Eisai Co., Ltd. for kindly providing the drug used in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

Y. Taniyama and F. Sanada serve as external directors of Periotherapia Co., Ltd.K. Shibata, N. Koibuchi, and N. Katsuragi are members of Periotherapia Co., Ltd., a biotechnology company originating from The University of Osaka that develops POSTN targeted antibodies for the treatment of intractable diseases, including breast cancer.

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation |

Full term |

| ADC |

Antibody–drug conjugate |

| Akt |

Protein kinase B |

| CAF |

Cancer-associated fibroblast |

| CDH1 |

Cadherin 1 (E-cadherin) |

| cDNA |

Complementary DNA |

| DMEM |

Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium |

| ECM |

Extracellular matrix |

| EMT |

Epithelial–mesenchymal transition |

| ER |

Estrogen receptor |

| ERK |

Extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| Ex |

Exon |

| FAS1 |

Fasciclin-like domain 1 |

| FBS |

Fetal bovine serum |

| 5-FU |

5-Fluorouracil |

| GAPDH |

Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| Gy |

Gray (unit of absorbed radiation dose) |

| HER2 |

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 |

| IL |

Interleukin |

| i.p. |

Intraperitoneal injection |

| i.v. |

Intravenous injection |

| MCF10DCIS |

MCF10DCIS.com human breast cancer cell line |

| MDA-MB-231 |

Human triple-negative breast cancer cell line |

| MEXT |

Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (Japan) |

| mRNA |

Messenger RNA |

| PBS |

Phosphate-buffered saline |

| PCR |

Polymerase chain reaction |

| PN |

Periostin isoform (PN1–PN4) |

| PN-21Ab |

Anti-periostin exon 21 monoclonal antibody |

| POSTN |

Periostin |

| PR |

Progesterone receptor |

| PTX |

Paclitaxel |

| qRT-PCR |

Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction |

| SD |

Standard deviation |

| SPF |

Specific pathogen-free |

| TGF-β |

Transforming growth factor beta |

| TME |

Tumor microenvironment |

| TNBC |

Triple-negative breast cancer |

| VC |

Vinorelbine combination group |

| ZEB1 |

Zinc finger E-box-binding homeobox 1 |

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021, 71, 209–249. [CrossRef]

- Bianchini, G.; Balko, J.M.; Mayer, I.A.; Sanders, M.E.; Gianni, L. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: Challenges and Opportunities of a Heterogeneous Disease. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2016, 13, 674–690.

- Foulkes, W.D.; Smith, I.E.; Reis-Filho, J.S. Triple-Negative Breast Cancer; 2010; Vol. 363;.

- Articles Comparisons between Diff Erent Polychemotherapy Regimens for Early Breast Cancer: Meta-Analyses of Long-Term Outcome among 100 000 Women in 123 Randomised Trials. 2011. [CrossRef]

- Conway, S.J.; Izuhara, K.; Kudo, Y.; Litvin, J.; Markwald, R.; Ouyang, G.; Arron, J.R.; Holweg, C.T.J.; Kudo, A. The Role of Periostin in Tissue Remodeling across Health and Disease. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2014, 71, 1279–1288.

- Kudo, A. Periostin in Fibrillogenesis for Tissue Regeneration: Periostin Actions inside and Outside the Cell. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2011, 68, 3201–3207.

- Takayama, G.; Arima, K.; Kanaji, T.; Toda, S.; Tanaka, H.; Shoji, S.; McKenzie, A.N.J.; Nagai, H.; Hotokebuchi, T.; Izuhara, K. Periostin: A Novel Component of Subepithelial Fibrosis of Bronchial Asthma Downstream of IL-4 and IL-13 Signals. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology 2006, 118, 98–104. [CrossRef]

- Katsuragi, N.; Morishita, R.; Nakamura, N.; Ochiai, T.; Taniyama, Y.; Hasegawa, Y.; Kawashima, K.; Kaneda, Y.; Ogihara, T.; Sugimura, K. Periostin as a Novel Factor Responsible for Ventricular Dilation. Circulation 2004, 110, 1806–1813. [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, S.; Nakao, S.; Nakama, T.; Kita, T.; Asato, R.; Sassa, Y.; Arita, R.; Miyazaki, M.; Enaida, H.; Oshima, Y.; et al. Periostin Promotes the Generation of Fibrous Membranes in Proliferative Vitreoretinopathy Keijiro Ishikawa1. FASEB Journal 2014, 28, 131–142. [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, S.S.; Yuan, S.; Innes, A.L.; Kerr, S.; Woodruff, P.G.; Hou, L.; Muller, S.J.; Fahy, J. V. Roles of Epithelial Cell-Derived Periostin in TGF-β Activation, Collagen Production, and Collagen Gel Elasticity in Asthma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010, 107, 14170–14175. [CrossRef]

- Katsuragi, N.; Morishita, R.; Nakamura, N.; Ochiai, T.; Taniyama, Y.; Hasegawa, Y.; Kawashima, K.; Kaneda, Y.; Ogihara, T.; Sugimura, K. Periostin as a Novel Factor Responsible for Ventricular Dilation. Circulation 2004, 110, 1806–1813. [CrossRef]

- Malanchi, I.; Santamaria-Martínez, A.; Susanto, E.; Peng, H.; Lehr, H.A.; Delaloye, J.F.; Huelsken, J. Interactions between Cancer Stem Cells and Their Niche Govern Metastatic Colonization. Nature 2012, 481, 85–91. [CrossRef]

- González-González, L.; Alonso, J. Periostin: A Matricellular Protein with Multiple Functions in Cancer Development and Progression. Front Oncol 2018, 8.

- Shao, R.; Bao, S.; Bai, X.; Blanchette, C.; Anderson, R.M.; Dang, T.; Gishizky, M.L.; Marks, J.R.; Wang, X.-F. Acquired Expression of Periostin by Human Breast Cancers Promotes Tumor Angiogenesis through Up-Regulation of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor 2 Expression. Mol Cell Biol 2004, 24, 3992–4003. [CrossRef]

- Nakazawa, Y.; Taniyama, Y.; Sanada, F.; Morishita, R.; Nakamori, S.; Morimoto, K.; Yeung, K.T.; Yang, J. Periostin Blockade Overcomes Chemoresistance via Restricting the Expansion of Mesenchymal Tumor Subpopulations in Breast Cancer. Sci Rep 2018, 8. [CrossRef]

- Litvin, J.; Selim, A.H.; Montgomery, M.O.; Lehmann, K.; Rico, M.C.; Devlin, H.; Bednarik, D.P.; Safadi, P.F. Expression and Function of Periostin-Isoforms in Bone. J Cell Biochem 2004, 92, 1044–1061. [CrossRef]

- Morra, L.; Moch, H. Periostin Expression and Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Cancer: A Review and an Update. Virchows Archiv 2011, 459, 465–475.

- Cui, D.; Huang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Ouyang, G. The Multifaceted Role of Periostin in Priming the Tumor Microenvironments for Tumor Progression. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 2017, 74, 4287–4291.

- Shibata, K.; Koibuchi, N.; Sanada, F.; Katsuragi, N.; Kanemoto, Y.; Tsunetoshi, Y.; Ikebe, S.; Yamamoto, K.; Morishita, R.; Shimazu, K.; et al. The Importance of Suppressing Pathological Periostin Splicing Variants with Exon 17 in Both Stroma and Cancer. Cells 2024, 13. [CrossRef]

- Ikeda-Iwabu, Y.; Taniyama, Y.; Katsuragi, N.; Sanada, F.; Koibuchi, N.; Shibata, K.; Shimazu, K.; Rakugi, H.; Morishita, R. Periostin Short Fragment with Exon 17 via Aberrant Alternative Splicing Is Required for Breast Cancer Growth and Metastasis. Cells 2021, 10. [CrossRef]

- Kanemoto, Y.; Sanada, F.; Shibata, K.; Tsunetoshi, Y.; Katsuragi, N.; Koibuchi, N.; Yoshinami, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Morishita, R.; Taniyama, Y.; et al. Expression of Periostin Alternative Splicing Variants in Normal Tissue and Breast Cancer. Biomolecules 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Balbi, C.; Milano, G.; Fertig, T.E.; Lazzarini, E.; Bolis, S.; Taniyama, Y.; Sanada, F.; Silvestre, D. Di; Mauri, P.; Gherghiceanu, M.; et al. An Exosomal-Carried Short Periostin Isoform Induces Cardiomyocyte Proliferation. Theranostics 2021, 11, 5634–5649. [CrossRef]

- Fujikawa, T.; Sanada, F.; Taniyama, Y.; Shibata, K.; Katsuragi, N.; Koibuchi, N.; Akazawa, K.; Kanemoto, Y.; Kuroyanagi, H.; Shimazu, K.; et al. Periostin Exon-21 Antibody Neutralization of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cell-Derived Periostin Regulates Tumor-Associated Macrophage Polarization and Angiogenesis. Cancers (Basel) 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R. The Biology and Function of Fibroblasts in Cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2016, 16, 582–598.

- Dongre, A.; Weinberg, R.A. New Insights into the Mechanisms of Epithelial–Mesenchymal Transition and Implications for Cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2019, 20, 69–84.

- Pastushenko, I.; Blanpain, C. EMT Transition States during Tumor Progression and Metastasis. Trends Cell Biol 2019, 29, 212–226. [CrossRef]

- Lamouille, S.; Xu, J.; Derynck, R. Molecular Mechanisms of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014, 15, 178–196.

- Nieto, M.A.; Huang, R.Y.Y.J.; Jackson, R.A.A.; Thiery, J.P.P. EMT: 2016. Cell 2016, 166, 21–45. [CrossRef]

- Balbi, C.; Milano, G.; Fertig, T.E.; Lazzarini, E.; Bolis, S.; Taniyama, Y.; Sanada, F.; Silvestre, D. Di; Mauri, P.; Gherghiceanu, M.; et al. An Exosomal-Carried Short Periostin Isoform Induces Cardiomyocyte Proliferation. Theranostics 2021, 11, 5634–5649. [CrossRef]

- Kyutoku, M.; Taniyama, Y.; Katsuragi, N.; Shimizu, H.; Kunugiza, Y.; Iekushi, K.; Koibuchi, N.; Sanada, F.; Oshita, Y.; Morishita, R. Role of Periostin in Cancer Progression and Metastasis: Inhibition of Breast Cancer Progression and Metastasis by Anti-Periostin Antibody in a Murine Model. Int J Mol Med 2011, 28, 181–186. [CrossRef]

- Tsunetoshi, Y.; Sanada, F.; Kanemoto, Y.; Shibata, K.; Masamune, A.; Taniyama, Y.; Yamamoto, K.; Morishita, R. A Role for Periostin Pathological Variants and Their Interaction with HSP70-1a in Promoting Pancreatic Cancer Progression and Chemoresistance. Int J Mol Sci 2024, 25. [CrossRef]

- Fischer, K.R.; Durrans, A.; Lee, S.; Sheng, J.; Li, F.; Wong, S.T.C.; Choi, H.; El Rayes, T.; Ryu, S.; Troeger, J.; et al. Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition Is Not Required for Lung Metastasis but Contributes to Chemoresistance. Nature 2015, 527, 472–476. [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, T.; Ozawa, Y.; Kimura, T.; Sato, Y.; Kuznetsov, G.; Xu, S.; Uesugi, M.; Agoulnik, S.; Taylor, N.; Funahashi, Y.; et al. Eribulin Mesilate Suppresses Experimental Metastasis of Breast Cancer Cells by Reversing Phenotype from Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) to Mesenchymal-Epithelial Transition (MET) States. Br J Cancer 2014, 110, 1497–1505. [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, E.; Horiuchi, K.; Senoo, A.; Susa, M.; Inoue, M.; Ishizaka, T.; Rikitake, H.; Matsuhashi, Y.; Chiba, K. Eribulin Induces Tumor Vascular Remodeling through Intussusceptive Angiogenesis in a Sarcoma Xenograft Model. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2021, 570, 89–95. [CrossRef]

- Hong, J.; Zhou, J.; Fu, J.; He, T.; Qin, J.; Wang, L.; Liao, L.; Xu, J. Phosphorylation of Serine 68 of Twist1 by MAPKs Stabilizes Twist1 Protein and Promotes Breast Cancer Cell Invasiveness. Cancer Res 2011, 71, 3980–3990. [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, Y.; Weeraratna, A.T. Fibroblasts in Cancer: Unity in Heterogeneity. Cell 2023, 186, 1580–1609. [CrossRef]

- Ouanouki, A.; Lamy, S.; Annabi, B. Oncotarget 22023 Www.Oncotarget.Com Periostin, a Signal Transduction Intermediate in TGF-β-Induced EMT in U-87MG Human Glioblastoma Cells, and Its Inhibition by Anthocyanidins; 2018; Vol. 9;.

- Chen, Y.; McAndrews, K.M.; Kalluri, R. Clinical and Therapeutic Relevance of Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2021, 18, 792–804.

- Kim, R.-K.; Kaushik, N.; Suh, Y.; Yoo, K.-C.; Cui, Y.-H.; Kim, M.-J.; Lee, H.-J.; Kim, I.-G.; Lee, S.-J. Radiation Driven Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Is Mediated by Notch Signaling in Breast Cancer; 2016; Vol. 7;.

- He, E.; Pan, F.; Li, G.; Li, J. Fractionated Ionizing Radiation Promotes Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition in Human Esophageal Cancer Cells through PTEN Deficiency-Mediated Akt Activation. PLoS One 2015, 10. [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Bai, X.; Zhou, W.; He, Y.; Wu, Y.; Wang, X. Radiation Exposure Triggers the Progression of Triple Negative Breast Cancer via Stabilizing ZEB1. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2018, 107, 1624–1630. [CrossRef]

- Mani, S.A.; Guo, W.; Liao, M.J.; Eaton, E.N.; Ayyanan, A.; Zhou, A.Y.; Brooks, M.; Reinhard, F.; Zhang, C.C.; Shipitsin, M.; et al. The Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Generates Cells with Properties of Stem Cells. Cell 2008, 133, 704–715. [CrossRef]

- Brabletz, S.; Schuhwerk, H.; Brabletz, T.; Stemmler, M.P. Dynamic EMT: A Multi-tool for Tumor Progression. EMBO J 2021, 40. [CrossRef]

- Thiery, J.P.; Acloque, H.; Huang, R.Y.J.; Nieto, M.A. Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transitions in Development and Disease. Cell 2009, 139, 871–890. [CrossRef]

- Kalluri, R. The Biology and Function of Fibroblasts in Cancer. Nat Rev Cancer 2016, 16, 582–598.

- Lamouille, S.; Xu, J.; Derynck, R. Molecular Mechanisms of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014, 15, 178–196.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).