1. Introduction

Nowadays, increasing competition forces businesses to pay greater attention to customer satisfaction and to provide better services [

1,

2]. Researchers argue that cognitive involvement is one of the most important concepts in consumer behavior, essential for analyzing consumer actions and assisting in the development of marketing strategies [

3]. Cognitive involvement can be explained as the extent of cognitive arousal and interest that consumers exhibit during specific purchase decisions [

1]. According to [

4] when consumers are highly involved in purchase decisions, they are more likely to research and gather information about products. This deep involvement can significantly influence their future buying behaviors. Mitchell [

5] defined purchase decision involvement (PDI) as “the amount of attention and concern an individual exhibits during the purchase decision-making process.” This concept relates to the consumer’s attitude toward the impending purchase decision, reflecting the importance or insignificance of choosing the right or wrong brand for them and whether selecting among different options makes a difference. This perspective mirrors the consumer’s mindset throughout the stages of the purchase decision process [

6].

While PDI is influenced by a range of factors, its manifestation varies significantly across product categories and cultural contexts. In the food industry, especially in segments like confectionery, where emotional appeal, brand familiarity, and habitual consumption play prominent roles in understanding what drives PDI is both complex and essential. Consumers may exhibit high involvement not only due to health concerns or brand trust but also because of symbolic meanings associated with certain food brands [

7,

8]. At the same time, macroeconomic pressures such as inflation and rising living costs have shifted consumer priorities toward price sensitivity, often reducing cognitive engagement and weakening brand loyalty [

9,

10]. This tension between emotional-brand engagement and economic rationality underscores the need for context-specific research on PDI.

Moreover, the role of technology in shaping involvement remains debated. On one hand, digital tools such as brand-specific mobile apps and digital wallets can enhance interaction and deepen consumer engagement [

11]. On the other hand, opposing views such as some authors [

12], automation, and algorithm-driven recommendations may streamline decision-making, leading to lower cognitive effort and reduced involvement. These contradictory effects highlight the complexity of modern consumer behavior and the importance of examining PDI within specific technological and cultural environments.

Despite its theoretical and practical significance, empirical research on the antecedents of purchase decision involvement (PDI) in food branding remains scarce, particularly within the context of emerging markets. The majority of existing studies on consumer involvement have focused predominantly on durable goods, luxury products, or high-involvement categories such as automobiles, electronics, or financial services where the perceived risk and personal relevance of purchase decisions are inherently higher [

1,

3,

13]. However, this emphasis has resulted in a significant lack of insight into how Purchase Decision Involvement (PDI) operates in low-engagement, commonly bought products like packaged foods and sweets, where feelings, habits, and sensory experiences tend to have more influence than logical evaluation [

14,

15,

16].

This discrepancy is particularly evident in culturally and economically unique settings such as Iran, where consumer behavior is influenced by a complex combination of religious beliefs, collective social values, economic instability, and the changing dynamics of brand markets [

17,

18]. Some authors [

18] demonstrate that Iranian consumers place high importance on brand heritage and domestic origin when evaluating food products, which can amplify PDI even in low-involvement categories. As well as, over the past decades, companies have become customer-centric and heavily reliant on marketing to provide a distinctive brand experience aimed at reducing consumer price sensitivity [

19]. Furthermore, findings indicate that consumers prioritize the functional features of products over the aesthetic aspects of the store environment when making purchase decisions, underscoring the need for further research on store-specific environments in grocery markets across different regions [

20]. Indeed, gaining diverse insights into consumer purchase decisions at the point of sale and purchase intentions serves as an effective tool for marketers and retailers to identify consumers with specific characteristics, which in turn enables them to tailor retailing methods or strategies to target willing buyers [

21]. Analyzing the factors influencing consumer purchase decisions at the point of sale goes beyond being a science; it is essentially considered an art [

22].

In today’s increasingly competitive markets, the entire endeavor of marketing science focuses on influencing consumer behavior. To achieve this goal, companies must be able to develop effective advertising and promotional policies. Success in formulating marketing strategies requires managers to have accurate and reliable data and information that enable them to correctly identify and categorize the factors influencing consumer purchase decisions [

23] A review of the literature reveals that very limited research has been conducted on the factors affecting Purchase Decision Involvement (PDI) in food brands. In today’s competitive and diversified food product markets, retailers need to attract and actively engage customers in the purchase decision process in order to maintain and increase market share. Customer involvement enhances the shopping experience, increases loyalty, and raises the likelihood of brand preference, a factor of particular importance in the sensitive food market. Given the complexity of consumer needs and intensified competition, identifying the key factors of such involvement can improve marketing strategies, especially promotional strategies, enhance sales performance, and assist in designing products and services that align with customer expectations. To this end, a specific brand from a confectionery chain store in Tehran will be examined to better understand Iranian consumers’ behavior in the purchase decision involvement process. This study also aims to assist retailers in optimizing resource utilization, strengthening targeted innovations, and creating more effective consumer interactions, ultimately contributing to sustainable development and differentiation in the market.

2. Hypotheses and Conceptual Framework

2.1. Store Image

The store image is a multi-dimensional concept that has been given several definitions by different researchers. Martineau [

24] is the first person who raised the issue of store image. He describes the store image as follows: Store image is a concept that is imprinted in customer’s mind and includes the functional and psychological characteristics of the store. Therefore, store image is shaped by the perception of each individual customer [

25]. According to some authors [

26], customers’ trust in a store is derived from their mental image of the store, its employees, and its products. Wu [

27], store image is formed from various store attributes, indicating that customers’ attitudes are influenced by both the inherent and external features of the store. Graciola et al. [

28] a stronger perception of a store’s image leads to higher consumer brand awareness. Additionally, store image acts as a key standalone factor that enhances brand recognition and boosts the perceived value. Store image is important for retailers and marketing managers’ business strategies because it guarantees differentiation in the market [

29]. Based on this literature review, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1. Store image has a positive and significant influence on consumers’ brand trust.

2.2. Brand Trust

Trust is defined as “the expectation held by a consumer that a service provider is dependable and can be relied on to deliver on its promises.” [

30]. It was also reported that brand image contributes to trust [

31,

32] According to these definitions, brand trust is described as the consumer’s readiness to depend on the brand’s capability to fulfill its promised function. [

33]. Keh & Xie [

34] brand trust was introduced as a basic prerequisite for building relationships with customers. Şahin et al. [

35] believe that concept of brand trust is based on the idea of a brand-consumer relationship, which is seen as a substitute for human contact between the store and its consumers. Sheau-Fen et al.[

36] examined how perceived risks, quality, and familiarity with store brands influence consumers and discovered that brand familiarity has the most significant impact on perceived quality and the intention to purchase store brand products. Therefore, the hypothesis is as follows:

H2. Consumers’ brand trust has a positive, direct, and significant influence on purchase decision involvement.

2.3. Product Class Involvement and Purchase Decision Involvement

In recent years, the concepts of product involvement and purchase decision involvement have gained significant attention and have been widely studied in the areas of information systems and marketing. Mitchell [

5] describes product involvement as an internal state variable as an individual agent whose motivational characteristic is created by a specific stimulus or situation. Product involvement, according to some authors [

37] refer to the overall level of consumer engagement with particular attributes of a food product. They identified price, taste, nutritional value, convenience of preparation, and brand name as key factors used to assess product involvement [

38]. They defined price, taste, nutrition, ease of preparation, and brand name as variables that measure product involvement. Kim and Sung [

39] investigated the dimensions of purchase decision involvement: affective and cognitive involvement in the product and brand. The results indicated that the four proposed constructs were consistent and valid for measuring different types of product class involvement in product categories. Also, Jiang et al. [

13] note in their study that products with high involvement typically possess a high capital value. To make well-informed purchase decisions, consumers usually invest considerable time gathering information when dealing with high-involvement products. Bhardwaj et al. [

40] found that in a clothing store, the purchase decision involvement of consumers in choosing a clothing brand in the cases of buying expensive brands and buying stylish and attractive clothing styles is positively influenced by a customer’s shopping style. Sang et al. [

41] reported a strong negative relationship between customer satisfaction and change of brand name intention for customers with high purchase decision involvement. While a strong positive relationship between need for variety and change of brand name intention was observed for customers with low purchase decision involvement. Liu et al. [

42] found that as temporal distance increases, consumer involvement in purchase decisions also rises, which subsequently leads to greater overall consumer consumption. Accordingly, we propose the following hypotheses:

H3. Product class involvement has a positive, direct, and significant influence on purchase decision involvement.

3. Methodology

3.1. Participants

The data collection tool in this study is a questionnaire consisting of 270 questions. The first part of the questions includes demographic information, and the second part includes items related to the selected variables, which are available in

Table 1. Data was also collected in both quantitative and qualitative ways. All of these statements presented in the survey asked respondents to indicate their agreement on a five-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree (1)” to “strongly agree (5)”. In addition, data were collected from 170 customers through face-to-face interviews in two confectionery chain stores of a specific brand, using a simple random sampling method, in 2023.

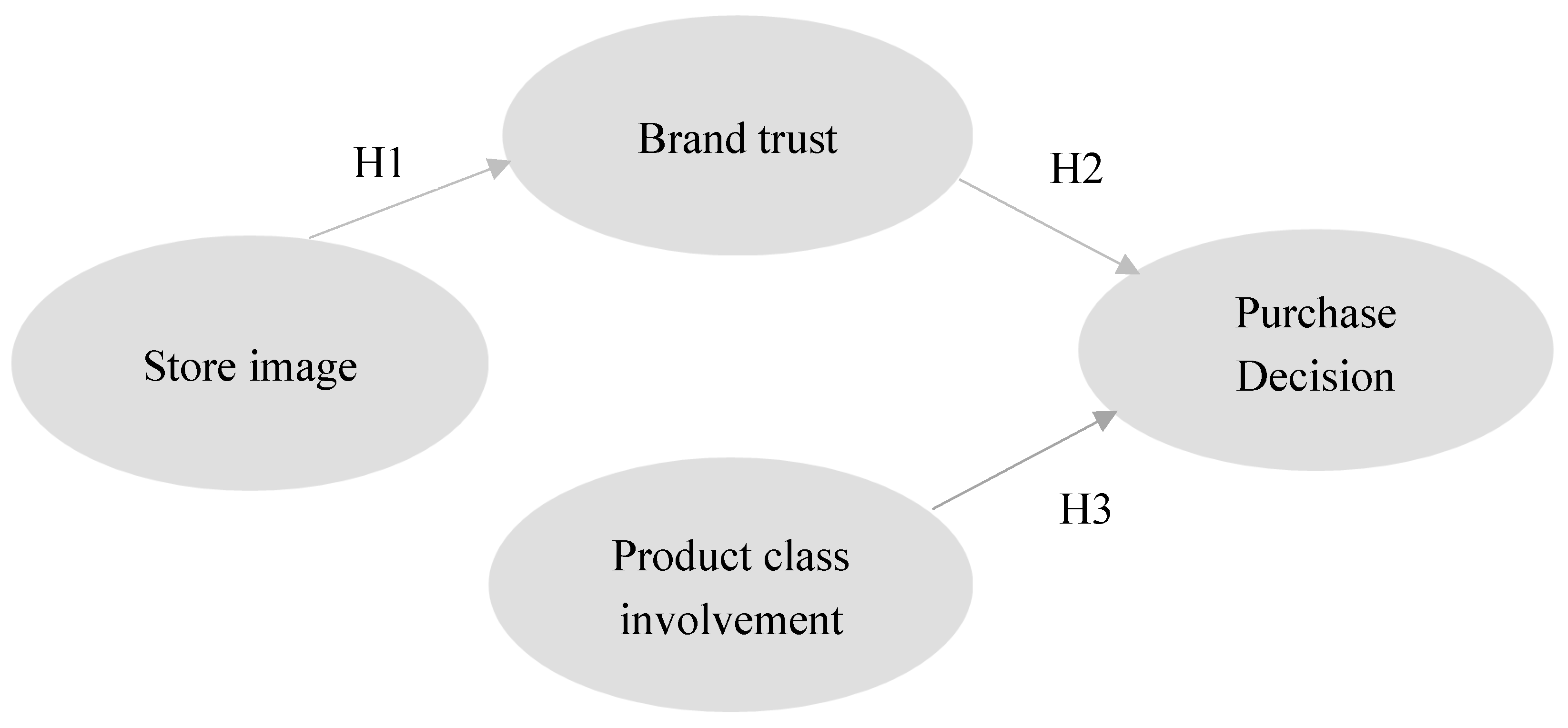

Figure 1 shows the relationships and hypotheses derived from the up section.

3.2. Structural

Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) method is an extension of path analysis and multiple regression, both of which are forms of multivariate analysis models. In multivariate correlation or causal analyses, SEM has gradually supplanted path analysis and multiple regression, demonstrating its superiority. The advantage of SEM lies in its ability to analyze data more comprehensively and thoroughly [

44]. This is because, in SEM, analysis is conducted at a deeper level where each item of the research instrument is considered as an observed variable or an indicator of a latent construct, enabling a more precise and comprehensive examination of the data [

45]. The initial phase of this study involves gathering data through a questionnaire. Then, in the next step, hypotheses are determined that in this research, the variables of brand trust, product category involvement, and purchase decision involvement are taken from [

39], and the store image variable is taken from [

46]. The next step is to identify and estimate the structural model. In this research, confirmatory factor analysis is utilized to evaluate the construct validity of the questionnaire. To establish convergent validity within the context of factor analysis, average variance extracted (AVE) is calculated, following the criterion proposed by Fornel and Larcker [

47]. This criterion is calculated as the sum of the squared factor loadings divided by the number of items. In the present study, the adequacy of the measurement model is evaluated based on three primary criteria: construct validity, convergent validity, and reliability, the latter assessed via Cronbach’s alpha coefficient. Construct validity represents a multifaceted concept, necessitating evaluation through multiple dimensions, including concurrent validity, predictive validity, discriminant validity, and convergent validity. It denotes the extent to which an instrument precisely measures the underlying theoretical construct or attribute of interest [

48]. Cronbach’s alpha coefficient serves as an index of the internal consistency and reliability among the questionnaire items. The concluding phase of the analysis involves model modification, which aims to enhance the goodness of fit between the proposed model and the empirical data [

49]. For the structural model assessment in this research, Smart PLS 3 software was employed.

3.3. Data and Instance Descriptions

The city of Tehran has a population of 9 million people and 2 million nine hundred households and is one of the most populated cities in Iran. For this purpose, in the current research, the population under investigation, customers of a prominent chain of confectionery and chocolate stores in Tehran, have been selected. This brand has 9 active branches in Tehran and has more than 80 years of experience in the cake and pastry industry, also has a variety of products such as cakes, sweets, all kinds of desserts, bread, and other products. Therefore, we will ask the customers of this confectionery to express the characteristics of the products such as price, taste, freshness, variety, brand, and the image they have of this store by answering the questions and how important it is to them while buying sweets. In order to identify the needs and preferences of consumers in choosing consumer products.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Socioeconomic Impacts

Table 2 presents analysis of the respondents’ demographic characteristics. Majority of customers of these stores are married, women, between the ages of 20 to 40, with bachelor’s and master’s degrees, and working in the public sector.

4.2. Assessment of Overall Structural Model

Results of the construct validity test, we conducted a comprehensive evaluation of both construct validity and reliability. Specifically, we assessed internal consistency reliability using Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR), and examined convergent validity through average variance extracted (AVE) and outer loadings. The results confirmed that the measurement model is both reliable and valid. All constructs reported Cronbach’s alpha and CR values well above the recommended threshold of 0.70, indicating a high degree of internal consistency [

50]. This suggests that the items used to measure each construct were homogeneous and conceptually coherent.

Table 3 shows all AVE values ranged from 0.864 to 0.936 across the constructs substantially exceeding the minimum accepted value of 0.50. These elevated AVE scores indicate that a substantial proportion of variance in the indicators was captured by their respective latent constructs, thereby confirming strong convergent validity. Additionally, the outer loadings of all items were statistically significant and exceeded the standard cut-off point of 0.70, further reinforcing the appropriateness of the indicators used in the study. These findings collectively support the conclusion that the constructs used in our structural model demonstrate high levels of reliability and validity, providing a solid foundation for subsequent structural path analysis.

If AVE values of each latent construct exceed its squared correlation with any other latent construct, discriminant validity is established [

51]. Accordingly, the square roots of AVE values were compared with the correlation between each pair of constructs. Finally, as presented in

Table 4, convergent validity demonstrates a relatively strong association between each item and its corresponding construct, with values ranging from 0.752 to 0.887. This reflects satisfactory internal stability for the measurement models. Accordingly, all latent variables were found to exhibit convergent validity.

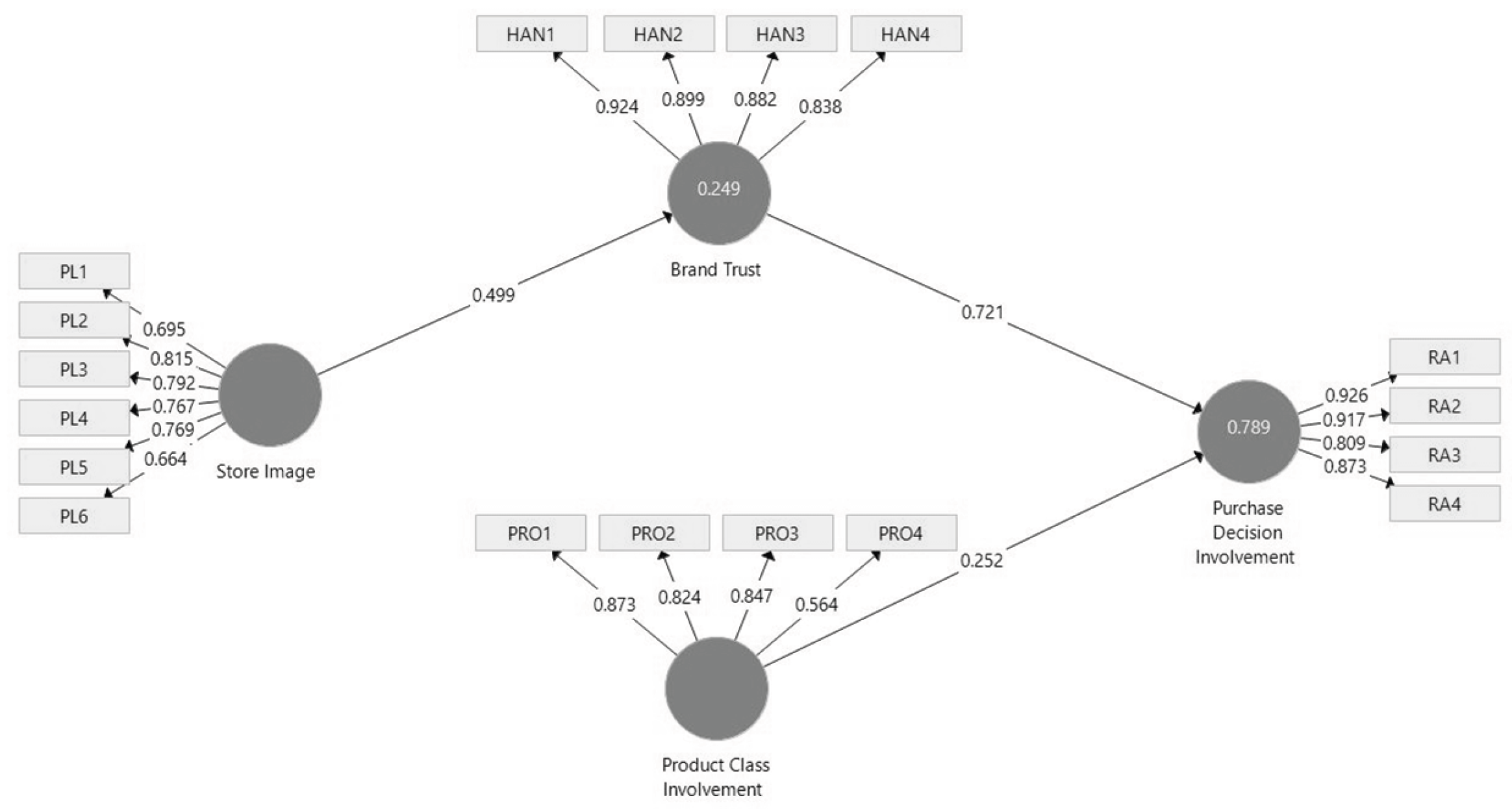

Figure 2 presents the outcomes of the hypothesis test, illustrating the relationships among the variables through reflective measurement models. It also displays the path coefficients, the coefficient of determination, and the t-statistic between the variables. These findings are summarized in

Table 4.

4.3. The Path Coefficients and Hypotheses Testing

Table 5 presents the findings related to consumers’ perspectives on purchase decision involvement in buying sweets and chocolate.

H1. The Effect of Store Image on Brand Trust.

Results of the structural equation modeling reveal that store image exerts a positive and statistically significant effect on brand trust, and the t-statistic is 9.362. This finding supports Hypothesis 1, confirming that the way a retail store is perceived by consumers substantially shapes their trust in the store’s private or featured brands.

This result aligns with a well-established body of literature highlighting the multi-dimensional nature of store image, which encompasses factors such as product quality, pricing transparency, customer service, and store layout [

52]. A positive store image can signal professionalism, reliability, and consistency characteristics that consumers often associate with trustworthy brands Some authors [

53] demonstrated that store image directly influences consumers’ willingness to purchase store brands, suggesting that the store serves as a heuristic or shortcut for assessing brand quality. More recently, Dursun et al. [

54] emphasized the strategic role of store image in the development and positioning of store brands, arguing that a favorable image enables retailers to extend trust toward relatively unfamiliar or new brand offerings. Islam et al. [

55] further nuanced this relationship by identifying store image as a moderating variable, strengthening the association between brand attitude and brand loyalty. In essence, when the store environment is perceived positively, the emotional and cognitive attachment to the brand is reinforced. These findings underscore the importance of managing the physical and psychological retail environment, not merely as an operational concern but as a strategic branding tool. Retailers aiming to build long-term customer trust must therefore invest in a holistic store experience that communicates credibility, quality, and authenticity.

H2. The Effect of Brand Trust on Purchase Decision Involvement

Hypothesis 2 is strongly supported by the data, as brand trust is shown to have a positive, direct, and statistically significant impact on purchase decision involvement, and the t-statistic is 18.764. This is one of the most robust relationships in the model, highlighting the pivotal role that brand trust plays in motivating consumers to invest cognitive and emotional effort into the decision-making process.

This finding is supported by Sheau-Fen et al.[

36] and Bhardwaj et al. [

40] found that brand trust not only increases the likelihood of purchase but also enhances customer engagement and brand loyalty. Maheswaran et al. [

56] further argued that brand names with strong reputations function as powerful informational cues, especially in low-involvement product categories, where consumers might otherwise rely on superficial attributes. Jerab [

57] suggests that in saturated retail environments, brand trust becomes a critical differentiator that draws consumer attention and deepens involvement. In addition, moreover, Hanaysha’s [

58] work in the fast-food sector of the UAE provides contemporary evidence of this dynamic, demonstrating that brand trust significantly predicts purchase intention, particularly in environments where product quality cannot be fully assessed prior to consumption. In such cases, trust serves as a psychological bridge between consumer expectations and perceived brand performance. Also, Pop et al. [

59] confirmed that brand trust positively influences purchase decisions.

Thus, retailers and brand managers must regard trust not as a by-product of marketing success, but as a strategic asset that directly engages the consumer and propels them toward meaningful, informed decision-making.

H3. The Effect of Product Class Involvement on Purchase Decision Involvement

Hypothesis 3 is also confirmed, indicating that product class involvement has a positive, direct, and significant impact on purchase decision involvement, and the t-statistic is 5.428. This finding suggests that when consumers are inherently interested or engaged with a specific category of products such as sweets and chocolates, they are more likely to dedicate attention, effort, and emotional energy to evaluating individual brand options within that category.

The concept of product involvement has long been recognized as a key driver of consumer behavior. This finding is supported by previous study [

60]. Sang et al. [

41] found that high-involvement product categories are associated with greater information search and longer decision times, as consumers seek to maximize satisfaction and minimize regret. Additionally, other authors [

61] suggest that product certification marks and reputation can influence decision involvement within product class involvement.

This relationship has strategic implications for marketers. By activating product involvement through educational campaigns, product sampling, and detailed feature comparisons, brands can stimulate consumers to move from habitual to deliberate purchasing behavior. The goal is not merely to trigger interest in a specific brand, but to elevate the entire product category in the consumer’s mind, positioning it as worthy of thoughtful consideration and engagement.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations

Empirical findings of this study indicate that three key factors store image, brand trust, and product class involvement can have a significant and positive impact on increasing consumer involvement in purchase decisions for food brands, particularly in the context of confectionery and chocolate stores. These results highlight the importance of psychological and perceptual dimensions in shaping customer behavior and provide a multifaceted framework to enhance buyer engagement throughout the purchasing process. The following conclusions are drawn for implementation, policy development, education, marketing, and future research.

From an operational perspective, food retailers and brand managers should simultaneously focus on improving both physical and psychological aspects of the store environment, strengthening trust-building mechanisms, and promoting active consumer engagement with the product category. These objectives can be achieved through redesigning store layout, ensuring hygiene and cleanliness, training and enhancing employee performance, and creating a pleasant and engaging in-store experience (such as appropriate music, appealing scents, and suitable color schemes for store décor). Such measures not only elevate the store’s image but also increase customer trust and deepen their involvement with the brand. Practical recommendations: Redesign the store environment to reflect modernity, cleanliness, and emotional comfort; implement loyalty programs and post-purchase feedback systems to enhance customer interaction, such as establishing a Customer Relationship Management (CRM) section; develop in-store training classes to improve staff service quality and customer orientation.

From a policy-making standpoint, consumer trust and engagement with brands can be reinforced through transparent information disclosure about product quality, guaranteeing product authenticity, and implementing return policies. Additionally, public organizations and industry associations should collaborate to enforce regulations and guidelines that ensure authenticity, clarity, and comparability of product information. Furthermore, policies should be formulated to support domestic brands that comply with trust-building criteria. Policy recommendations: develop mandatory standards for product labeling and price transparency; introduce national support programs for certified domestic brands with strong consumer trust indices; establish platforms and services for consumer feedback and complaint tracking to monitor and uphold trustworthiness.

Enhancing consumer knowledge and decision-making skills plays a crucial role in promoting more active participation in the purchasing process. To achieve this, public and private stakeholders should collaborate to provide extensive formal and informal educational programs that help consumers better understand and interpret brand quality signals, store conditions, and product quality. Moreover, culturally tailored campaigns can foster responsible and informed purchasing behaviors among consumers.

Educational recommendations: launch multimedia educational campaigns for recognizing authentic and reliable brands; design in-store education points using QR codes or interactive displays for product guidance; allocate a section of the store to cooking or confectionery workshops using the store’s products, which can attract customer attention and foster increased purchases.

For marketers and retail developers, this study underscores the importance of aligning branding efforts with strategies to enhance consumer involvement. Effective approaches include offering product samples, comparative advertising, storytelling, and utilizing visual merchandising displays to attract customer attention and encourage product purchase. In addition, leveraging digital tools and collaborating with influencers can help build brand familiarity and foster sustainable trust. Marketing suggestions:

- Employ experiential marketing techniques to boost cognitive and emotional engagement with products—for example, a specialty confectionery store could set up an interactive tasting section where customers sample various sweets and chocolates, learn about their aroma, taste, and texture, and select their favorites, thereby creating a stronger emotional and cognitive connection with the product. Collaborate with popular social media influencers to enhance brand credibility and reach interested consumer segments. Develop online shopping platforms that provide real-time product comparisons along with user reviews to facilitate informed purchasing decisions.

Although this study provides robust empirical evidence regarding the relationships among store image, brand trust, and product class involvement in influencing purchase decision involvement, its focus was on examining the direct structural relationships between these core constructs within a specific product category (confectionery and chocolates). This approach was essential to maintain high internal validity and clarity in interpreting the model results. Based on current findings, future research can expand the conceptual framework and address the limitations of this study by exploring the following areas:

- Investigating interaction effects between demographic variables (such as age, gender, income) and the main constructs studied to better understand group differences in brand trust formation and purchase decision involvement.

- Conducting comparative studies between domestic and foreign brands, particularly regarding the moderating role of brand origin in the relationship between store image and consumer trust.

- Analyzing differences across store types by comparing consumer responses between chain stores and independent retailers, which may vary in their capability to establish consistent store images and foster brand loyalty.

- Examining the impact of digital marketing and social media usage on brand trust and purchase decision involvement across different generational cohorts, especially considering the growing presence of online customers in various markets.

- Developing integrated conceptual models that combine cognitive and behavioral decision-making frameworks to better capture the complex and culturally embedded processes that underlie consumer choices in the Iranian context.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K.Y. and A.F.; methodology, M.K.Y and N.P.; software, M.K.Y.; validation, F.B. and A.F.; formal analysis, A.F. and M.K.Y.; investigation, M.K.Y.; resources, F.B. and A.F.; data curation, M.K.Y.; writing— original draft preparation, M.K.Y., A.F., N.P. and F.B.; writing—review and editing, F M.K.Y. and A.F; supervision, F.B. and A.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Before starting the data collection, participants were informed about the objective of the research and the consequent statistical analysis. Participation in the study was fully voluntary and anonymous and subjects could withdraw from the survey at any time and for any reason. Respondents were required to sign a policy privacy and consent form for collecting and processing personal data in advance, according to the Italian Data Protection Law (Legislative Decree 101/2018) in line with the European Commission General Data Protection Regulation (679/2016). The investigation was carried out following the rules of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, revised in 2013. All procedures involving research study participants were approved and are in line with the SWG Code of Conduct. Ethical review and approval were waived for this study because it did not involve any invasive procedure (e.g., fecal samples, voided urine, etc.), laboratory assessment, induce lifestyle changes, or impose dietary modifications.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Mittal, B. Measuring Purchase-decision Involvement. Psychol Mark 1989, 6, 147–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuad, E.; Abdullah, Z. Data Analytics of E-CRM Technology: Its Impact on Customer Experience, Satisfation, Trust, and Loyalty in e-Coomerce. JOURNAL INFORMATION AND TECHNOLOGY MANAGEMENT (JISTM) 2025, 10, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaichkowsky, J.L. Conceptualizing Involvement. J Advert 1986, 15, 4–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.S.; Yoon, H.H. Why Do Satisfied Customers Switch? Focus on the Restaurant Patron Variety-Seeking Orientation and Purchase Decision Involvement. Int J Hosp Manag 2012, 31, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, A.A. Involvement: A Potentially Important Mediator of Consumer Behavior. ACR North American Advances 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Peschel, A.O.; Grebitus, C.; Colson, G.; Hu, W. Explaining the Use of Attribute Cut-off Values in Decision Making by Means of Involvement. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics 2016, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seock, Y.K.; McBride, J. The Impact of Consumer Knowledge/Familiarity with Private Label Brands (PLBs) and Store Image on Perceptions and Preferences toward PLBs and Patronage Intentions: Case of Midscale Department Store PLBs. Journal of the Korean Society of Clothing and Textiles 2012, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adaval, R. How Good Gets Better and Bad Gets Worse: Understanding the Impact of Affect on Evaluations of Known Brands. Journal of Consumer Research 2003, 30, 352–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, U.T.X.; Tran, C.T.T.; Nguyen, N.M.T. Socioeconomic Constraints on Low-Income Individuals’ Perceptions toward Food Safety. J Sens Stud 2024, 39, e12918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.D.; Barrett, N.J.; Miller, K.E. Brand Loyalty in Emerging Markets. Marketing Intelligence & Planning 2011, 29, 222–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curran, J.M.; Meuter, M.L. Self-Service Technology Adoption: Comparing Three Technologies. Journal of Services Marketing 2005, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.F.Y.; To, W.M. Customer Involvement and Perceptions: The Moderating Role of Customer Co-Production. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2011, 18, 271–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Duan, R.; Jain, H.K.; Liu, S.; Liang, K. Hybrid Collaborative Filtering for High-Involvement Products: A Solution to Opinion Sparsity and Dynamics. Decis Support Syst 2015, 79, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imtiyaz, H.; Soni, P.; Yukongdi, V. Understanding Consumer’s Purchase Intention and Consumption of Convenience Food in an Emerging Economy: Role of Marketing and Commercial Determinants. J Agric Food Res 2022, 10, 100399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukhari, F.; Hussain, S.; Ahmed, R.R.; Mubasher, K.A.; Naseem, M.R.; Rizwanullah, M.; Nasir, F.; Ahmed, F. Consumers’ Purchase Decision in the Context of Western Imported Food Products: Empirical Evidence from Pakistan. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A.; Serventi, L.; Kumar, L.; Morton, J.D.; Torrico, D.D. Packaging, Perception, and Acceptability: A Comprehensive Exploration of Extrinsic Attributes and Consumer Behaviours in Novel Food Product Systems. Int J Food Sci Technol 2024, 59, 6725–6745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alizadeh, H.; Kashani, H.N. An Empirical Study of Consumer-Brand Relationships in the Hospitality Industry. Interdisciplinary Journal of Management Studies 2023, 16, 857–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakili, M.; Salehzadeh, R.; Esmailian, H. Exploring the Antecedents and Consequences of Brand Addiction among Iranian Consumers. Journal of Islamic Accounting and Business Research 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.C.; Li, M.Y.; Li, T. A Study of Experiential Quality, Experiential Value, Experiential Satisfaction, Theme Park Image, and Revisit Intention. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Research 2018, 42, 26–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brüggemann, P.; Martinez, L.F.; Pauwels, K. Theoretical Perspectives and Conceptual Framework for Online Grocery Shopping: Adapting to Environmental Circumstances and Influencing Internal Factors. Electronic Commerce Research 2025, 25, 2271–2307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behboodi, O.; Ghafourian, A.; Assistant, S.; Alimirzaee, H. From Attitude Components to Willingness to Purchase; Examining the Role of Marketing Mix, Social Responsibility and Perceived Quality; An Approach to Green Marketing (Case Study: Customers of Organic Products). Consumer Behavior Studies Journal 2023, 10, 91–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekzadeh, S.; Navehebrahim, A.; Abdollahi, B.; Zamahani, M. Designing the Model of Promotion of Educational Brand of Payame Noor University. Research in School and Virtual Learning 2019, 6, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colabi, A.M.; Goodarzi, A. Identifying Factors Influencing Online Shopping Decisions: The Role of Virtual Ideal Self-Image and Cognitive Approaches through Meta-Synthesis. Journal of Business Management 2025, 17, 266–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martineau, P. The Personality of the Retail Store. Harvard Business Review 1958, 36, 47–55. [Google Scholar]

- Morschett, D.; Swoboda, B.; Foscht, T. Perception of Store Attributes and Overall Attitude towards Grocery Retailers: The Role of Shopping Motives. International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 2005, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobucci, D.; Ostrom, A. Commercial and Interpersonal Relationships; Using the Structure of Interpersonal Relationships to Understand Individual-to-Individual, Individual-to-Firm, and Firm-to-Firm Relationships in Commerce. International Journal of Research in Marketing 1996, 13, 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.C.S.; Yeh, G.Y.Y.; Hsiao, C.R. The Effect of Store Image and Service Quality on Brand Image and Purchase Intention for Private Label Brands. Australasian Marketing Journal 2011, 19, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graciola, A.P.; De Toni, D.; Milan, G.S.; Eberle, L. Mediated-Moderated Effects: High and Low Store Image, Brand Awareness, Perceived Value from Mini and Supermarkets Retail Stores. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 2020, 55, 102117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdil, T.S. Effects of Customer Brand Perceptions on Store Image and Purchase Intention: An Application in Apparel Clothing. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 2015, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirdeshmukh, D.; Singh, J.; Sabol, B. Consumer Trust, Value, and Loyalty in Relational Exchanges. J Mark 2002, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.; Ham, S. Restaurants’ Disclosure of Nutritional Information as a Corporate Social Responsibility Initiative: Customers’ Attitudinal and Behavioral Responses. Int J Hosp Manag 2016, 55, 96–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.Y.; Ching Yuh, C.Y. The Influence of Corporate Image, Relationship Marketing, and Trust on Purchase Intention: The Moderating Effects of Word-of-mouth. Tourism Review 2010, 65, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Holbrook, M.B. The Chain of Effects from Brand Trust and Brand Affect to Brand Performance: The Role of Brand Loyalty. J Mark 2001, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keh, H.T.; Xie, Y. Corporate Reputation and Customer Behavioral Intentions: The Roles of Trust, Identification and Commitment. Industrial Marketing Management 2009, 38, 732–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şahin, A.; Zehir, C.; Kitapçi, H. The Effects of Brand Experiences, Trust and Satisfaction on Building Brand Loyalty; An Empirical Research On Global Brands. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 2011, 24, 1288–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheau-Fen, Y.; Sun-May, L.; Yu-Ghee, W. Store Brand Proneness: Effects of Perceived Risks, Quality and Familiarity. Australasian Marketing Journal 2012, 20, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moorthy, S.; Ratchford, B.T.; Talukdar, D. Consumer Information Search Revisited: Theory and Empirical Analysis. Journal of Consumer Research 1997, 23, 263–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellini, G.; Graffigna, G. Assessing Involvement with Food: A Systematic Review of Measures and Tools. Food Qual Prefer 2022, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Sung, Y. Dimensions of Purchase-Decision Involvement: Affective and Cognitive Involvement in Product and Brand. Journal of Brand Management 2009, 16:8 16, 504–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhardwaj, P.; Bhardwaj Xavier, P. Linkages Between Brand Experience, Shopping Styles and Purchase Decision Involvement: An Empirical Investigation in Retail Indian Apparel. International Journal of Business and Economics Research 2022, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Sang, H.; Xue, F.; Zhao, J. What Happens When Satisfied Customers Need Variety? –Effects Of Purchase Decision Involvement and Product Category on Chinese Consumers’ Brand-Switching Behavior. J Int Consum Mark 2018, 30, 148–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Huang, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhang, X.; Huang, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Y. Exploring Consumers’ Buying Behavior in a Large Online Promotion Activity: The Role of Psychological Distance and Involvement. Journal of theoretical and applied electronic commerce research 2020, 15, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.J.; Chang, Y.J. An Exploratory Research on the Store Image Attributes Affecting Its Store Loyalty.

- Chang, W.Y.B. Path Analysis and Factors Affecting Primary Productivity. J Freshw Ecol 1981, 1, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Lin, L.S. Structural Equation-Based Latent Growth Curve Modeling of Watershed Attribute-Regulated Stream Sensitivity to Reduced Acidic Deposition. Ecol Modell 2010, 221, 2086–2094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.; Chang, Y. An Exploratory Research on the Store Image Attributes Affecting Its Store Loyalty. Seoul Journal of Business 2005, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadbeigi, A.; Mohammadsalehi, N.; Aligol, M. Validity and Reliability of the Instruments and Types of MeasurmentS in Health Applied Researches. Journal of Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences 2015, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Akinyode, B.F. The Use of Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) in Built Environment Disciplines. International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE) 2016, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.P.; Fischer, A.; Nitzl, C.; Menictas, C. Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling-Based Discrete Choice Modeling: An Illustration in Modeling Retailer Choice. Business Research 2019, 12, 115–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error. Journal of Marketing Research 1981, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, P.S.; Dick, A.S.; Jain, A.K. Extrinsic and Intrinsic Cue Effects on Perceptions of Store Brand Quality. J Mark 1994, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, D.; Krishnan, R.; Baker, J.; Borin, N. The Effect of Store Name, Brand Name and Price Discounts on Consumers’ Evaluations and Purchase Intentions. Journal of Retailing 1998, 74, 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dursun, I.; Kabadayi, E.T.; Alan, A.K.; Sezen, B. Store Brand Purchase Intention: Effects of Risk, Quality, Familiarity and Store Brand Shelf Space. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 2011, 24, 1190–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, S.; Zahin, M.; Rahim, S.B. Investigating How Consumer-Perceived Value and Store Image Influence Brand Loyalty in Emerging Markets. South Asian Journal of Business Studies 2024, 13, 505–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheswaran, D.; Mackie, D.M.; Chaiken, S. Brand Name as a Heuristic Cue: The Effects of Task Importance and Expectancy Confirmation on Consumer Judgments. Journal of Consumer Psychology 1992, 1, 317–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerab, D. Factors Influencing Consumer Purchase Decisions in Online Shopping. SSRN Electronic Journal 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanaysha, J.R. Impact of Social Media Marketing Features on Consumer’s Purchase Decision in the Fast-Food Industry: Brand Trust as a Mediator. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights 2022, 2, 100102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, R.A.; Săplăcan, Z.; Dabija, D.C.; Alt, M.A. The Impact of Social Media Influencers on Travel Decisions: The Role of Trust in Consumer Decision Journey. Current Issues in Tourism 2022, 25, 823–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petty, R.E.; Cacioppo, J.T. The Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion. Adv Exp Soc Psychol 1986, 19, 123–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azad, N.; Roshan, A.H. Measuring Purchase-Decision Involvement. Management Science Letters 2014, 4, 1859–1864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).