1. Introduction

This work reconstructs the algebraic structure of reality from the minimal conditions under which existence is knowable to a subject. The very possibility of comprehension entails that primitive reality must be finite and attribute-free, while the experience of change entails that it must be timeful. From these necessities alone, the algebraic architecture of the Finite Ring Continuum emerges without discretionary assumptions.

Fundamental Axiom of Existence.

I think, therefore the Universe is.

This expression echoes, but fundamentally departs from, the classical Cartesian formulation

cogito, ergo sum [

1]. We interpret it not as a metaphysical guarantee of the self—a higher-order philosophical determination beyond our scope and purpose—but operationally: the very existence of experience entails that reality must be both

finite and

timeful. Finitude is required for experience to distinguish a bounded set of primitive states, while timefulness is required for the subject to comprehend their own comprehension. All algebraic structure developed in this work follows unavoidably from this epistemic reading of the Fundamental Axiom.

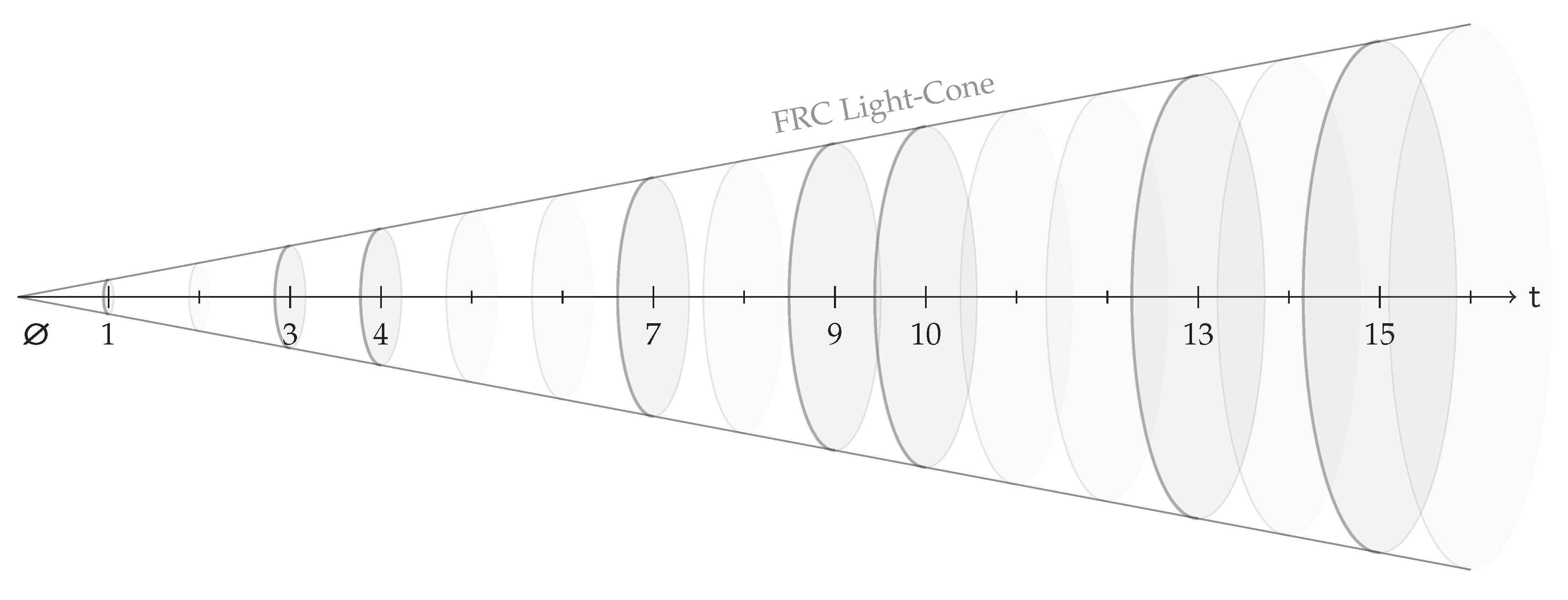

From finitude, the primitive states of the universe are necessarily indistinguishable and attribute-free, and their knowability requires that they form a finite collection closed under a single reversible successor operation. This forces the primitive universe to be a homogeneous finite cycle and therefore a cyclic group

. From timefulness, the structure of experience must contain a temporal polarity that cannot be reduced to spatial reversal. Such a temporal reflection cannot be realised within the cyclic successor structure alone, nor within a symmetry-complete prime field

as a nontrivial involutive field automorphism, even when the latter admits an internal Euclidean conjugation. The minimal finite-field domain capable of supporting such a distinct involution is the quadratic extension

, whose unique nontrivial automorphism

serves as temporal reflection. Together, the spatial involution

and the temporal involution

generate the Klein four-group, whose generic orbits contain four elements. Consequently, each genuinely new invariant emerges in an irreducible four-element packet, and the minimal enlargement of the symmetry shell is

. In this reconstruction, relational symmetry is therefore the primary driver of emergent invariants and structural complexity, echoing Noether’s insight that invariance principles govern the appearance of invariant quantities in physical theory [

2]. The resultant succession of finite symmetry shells

of the order

, where

t denotes a time-like chronon parameter, form the FRC Light Cone [

3] illustrated in

Figure 1.

These forced structures constitute the core of the Finite Ring Continuum (FRC) [

3,

4]. They also provide a natural setting for Dirac-like dynamics in the finite-field quadratic extension, where causal and temporal asymmetries appear as algebraic consequences of the Frobenius involution [

5].

Context and Prior Work.

Efforts to ground physical theory in informational, relational, or operational principles have a long pedigree. Relational approaches to space, time, and existence appear in the work of Leibniz and Mach, and more recently in Barbour’s relational dynamics [

6], Rovelli’s relational quantum mechanics [

7], and structural realist perspectives [

8]. Operational reconstructions of quantum theory and physical law (e.g. Hardy [

9], Chiribella

et al. [

10], and the information-theoretic approaches surveyed in [

11,

12]) similarly begin from epistemic constraints to derive formal structures.

Discrete and algebraic models of spacetime and information (Wheeler’s “it-from-bit” proposal [

13], Sorkin’s causal sets [

14], and finite-field quantum theories [

15]) share with the present work the desire to build physics from minimal principles. However, these approaches typically postulate discrete structures or algebraic frameworks from the outset: causal partial orders, Boolean information units, fixed Hilbert spaces, or chosen finite fields.

The Finite Ring Continuum (FRC), developed in [

3,

4,

5], takes a different path. Rather than selecting a mathematical structure and exploring its consequences, FRC attempts to

derive the mathematical structure of the universe from conditions of finite knowability and temporal experience. This shifts the emphasis from “Which mathematical system describes reality?” to “What algebraic form is forced by the existence of experience itself?”

Goal of this paper.

The purpose of this work is to show that the algebraic architecture of the Finite Ring Continuum is uniquely determined by the Fundamental Axiom of Existence. We demonstrate that once finitude and timefulness are acknowledged as operational necessities, all further structure—cyclicity, conjugation, quadratic extension, Klein symmetry, four-element innovation packets, and the linear shell law—arises without additional assumptions. The Uniqueness Theorem presented in

Section 6 formalises this result, establishing that any finite, attribute-free, genuinely evolving universe is forced to adopt the shell hierarchy of the Finite Ring Continuum.

Non-Axiomatic Status of This Reconstruction.

It is essential to emphasise that the present framework is not an axiomatic system proposed alongside others, nor does it compete with alternative formal foundations. The algebraic structure derived in this work follows not from stipulated axioms, but from the phenomenological necessities implicit in the very fact of experience. Once existence is taken in the operational sense—that experience occurs and can be recognised as such—the conditions of finite knowability and temporal polarity are unavoidable. All mathematical structure developed in this paper arises as the minimal consequence of these necessities. Accordingly, the Finite Ring Continuum is not one model among many, but the unique algebraic universe compatible with the possibility of comprehension of self. Critiques based on alternative axiom systems are therefore orthogonal: unless one rejects the phenomenological conditions that enable experience to occur, no other algebraic realisation is admissible.

Structure of the paper.

Section 2 formalises the phenomenological commitments of finitude and timefulness.

Section 3 and

Section 4 derive the algebraic consequences of these commitments, leading to the quadratic extension and the emergence of Klein symmetry.

Section 5 shows that innovation must occur in four-element packets, forcing the minimal shell increment

.

Section 6 presents and discusses the Uniqueness Theorem, the central result of the paper. Examples and illustrations appear in

Section 7, followed by a broader discussion of implications in

Section 8.

2. Phenomenological Commitments Derived from the Axiom of Existence

This work does not begin from independent mathematical postulates or discretionary axioms. Instead, it proceeds from a single epistemic principle, which we state in axiomatic form for clarity.

Axiom 1 (Fundamental Axiom of Existence).

Cogito, ergo universum est—I think, therefore the Universe is.

It is important to emphasize that the above statement is not a mathematical axiom in the traditional sense, but rather an epistemic primitive, a pre-mathematical constraint on comprehension in all of its forms. We interpret this statement operationally: the very fact that experience occurs imposes unavoidable structural constraints on the form that reality can take. These constraints are not optional assumptions but the minimal conditions under which existence becomes knowable to a subject. The following conditions follow immediately and necessarily from the Axiom.

Corollary 1 (Knowability).

For reality to be knowable, all admissible operations and distinctions must be internal to the domain itself. No primitive element or structural feature may lie beyond the operational horizon of the domain. Knowability therefore requires internal completeness: all primitives that can arise under admissible operations must already belong to the domain.

Corollary 2 (Finitude).

A knowable domain cannot be unbounded under admissible operations. If repeated application of admissible operations were to generate ever-new primitives without return, the domain would fail to be internally complete and thus fail to be knowable in the sense of Corollary 1.

Accordingly, knowability requires returnability: all admissible operations must eventually close on the domain itself. In representational terms, this property is described as finitude.

Remark 1. Infinity is not rejected here as a mathematical utilitarian concept. Rather, it lies outside the scope of primitive knowability as defined above. Structures invoking actual infinity may serve as effective idealizations, but they do not represent internally closed domains and therefore cannot constitute primitive reality within the present reconstruction.

Independently of the present derivation, it is worth noting that the epistemic and ontological status of actual infinity has been questioned in several foundational approaches to mathematics, including on the following grounds:

-

Epistemic inaccessibility.

No conceivable act of experience, measurement, or enumeration can verify or realize an infinite collection. In this sense, infinity functions as a presumptive and utilitarian postulate rather than an empirically grounded one.

-

Foundational tension.

The continuum has been argued to introduce structural and logical tensions that motivate finitist reformulations; see, for example, [16]. -

Structural redundancy.

A broad and systematically increasing range of mathematical constructions commonly formulated using actual infinity admit finite reformulations or interpretations. This perspective has been emphasized by Zeilberger [17] and Lev [18], among others, and further developed in [4].

These considerations are not required for the derivation presented here, but they situate the present results within a broader landscape of finitist and structural approaches.

Corollary 3 (Timefulness).

Experience contains a structural contrast between “now” and “not-now”, requiring a polarity that cannot be reduced to spatial or numerical reversal. The recognition of comprehension presupposes a distinction between the moment of experience and the moment in which that experience is reflected upon. This reflexive separation constitutes the minimal form of temporal polarity. Without it, states could be presented but not related, and no coherent notion of information update could exist.

Accordingly, any framework grounded in the possibility of comprehension must begin from internal completeness rather than from externally imposed attributes. Finitude and attribute-freeness are not axioms but consequences of knowability. The present reconstruction therefore derives all subsequent structure from the minimal conditions under which a domain can be internally closed and timefully extended.

A natural question follows as to whether such a minimal framework can support the rich phenomenology of observed reality. The remainder of this work demonstrates that it can, and that the algebraic structure of the Finite Ring Continuum emerges unavoidably from these commitments.

3. Algebraic Consequences of Finitude

Under the Fundamental Axiom of Existence, finitude is not an auxiliary assumption but a structural necessity of knowable reality. Since primitive states carry no intrinsic labels or attributes, their identity is determined solely by their relational position within a finite set, relative to the observer. Any admissible structure must therefore be relational, homogeneous, and internally complete through comprehension. In this section we derive the algebraic consequences of finitude and show that it forces the primitive state space to adopt a unique minimal additive structure. These results provide the Euclidean skeleton upon which the algebraic consequences of timefulness, developed in

Section 4, will be built.

Definition 1 (Primitive closure).

Let S be a set of primitive, attribute-free states. A primitive closure

on S is given by a reversible operation

such that for every , repeated application of σ eventually returns to x, and no application of σ ever leaves S. No absolute ordering, enumeration, counting, or distinguished element is assumed. The operation σ represents an admissible internal symmetry of the domain.

Corollary 4 (Admissible operation and information capacity). The only admissible primitive capability is the ability, given a current state , to transition to a state . This capability defines a transition relation but does not, by itself, specify a unique successor.

A primitive closure

is a reversible realization of this capability. Since , any such σ is a bijection and therefore decomposes into disjoint cycles, implying that its period is at most . Moreover, there exist closures whose action consists of a single -cycle, and hence

We call the information capacity of the primitive domain: it is the maximal reversible enumeration horizon realizable by any admissible closure. Closures with smaller period correspond to premature cycle closure and do not constitute alternative structures; they merely underutilize the available capacity.

Lemma 1 (Cyclic structure). Let S admit a primitive closure σ in the sense of Definition 1. Then S consists of a single closed orbit under σ. Consequently, once a representation is chosen, there exists a finite cyclic group structure on S, and S is isomorphic to a canonical cyclic representation for some q.

Proof. Because is reversible, its repeated application partitions S into disjoint closed orbits.

If more than one such orbit existed, membership in a particular orbit would constitute a relational distinction between primitive states, contradicting their attribute-free character. Hence only a single closed orbit is admissible.

A single closed orbit admits a canonical cyclic representation. Once such a representation is introduced, the orbit length defines a finite cyclic group, and S is isomorphic to . □

The successor operation therefore induces an additive structure on the primitive state space:

where addition is defined by iteration of

.

Lemma 2 (Spatial Reversal).

The additive cyclic structure admits a canonical involutive symmetry

which conjugates the successor map to its inverse .

Proof. Reversibility of enumeration implies that closure of the cycle may proceed in either direction. In coordinates on , this corresponds to the involution , which satisfies and reverses the orientation of the cycle. Any other involutive symmetry differs from R only by composition with a translation, reflecting the absence of an intrinsic origin. □

We interpret R as spatial reversal. It arises purely from the relational structure forced by finitude and does not encode temporal polarity.

Lemma 3 (Minimality of the Additive Structure). The additive cyclic group is the unique minimal algebraic structure compatible with finitude, homogeneity, and reversible enumeration.

Proof. Quotienting by any nontrivial subgroup collapses distinct primitive states, violating indistinguishability. Extending the group introduces additional algebraic attributes not grounded in finitude. Introducing multiple generators breaks the homogeneity of enumeration. Hence no proper quotient or extension preserves all consequences of finitude. □

This completes the derivation of the additive skeleton of the universe. No further structure has been assumed: the cyclic group arises uniquely from the operational content of finitude. Finally, we emphasize that this reconstruction does not assume a field structure. As shown in [

4], multiplication on

is definable from addition by repeated enumeration and distributivity, without introducing new primitive attributes. When

is prime, this canonical ring is a field

, uniquely determined up to isomorphism. The transition to a quadratic field in

Section 4 will arise solely from the requirements of timefulness, not from any independent postulate of fieldhood.

4. Algebraic Consequences of Timefulness

Under the Fundamental Axiom of Existence, timefulness is not a supplementary assumption but a structural necessity of experience. Experience presents a polarity between “now” and “not-now,” and this distinction must have an algebraic counterpart. Crucially, temporal polarity cannot be reduced to spatial reversal; otherwise, the temporal structure of experience would collapse into the symmetries already forced by finitude. In this section we derive the algebraic consequences of timefulness and establish that the temporal involution is distinct from any Euclidean symmetry present in the cyclic structure.

In symmetry-complete prime fields

with

, the element

i satisfying

exists internally. This allows the Euclidean theory developed in [

3,

4] to define an internal involution acting as a spatial reflection on framed complex coordinates,

which is a symmetry entirely contained within the Euclidean structure of the shell. This conjugation does not encode temporal polarity and cannot represent the distinction between “now” and “not-now.”

We therefore formalise timefulness as an algebraic requirement.

Definition 2 (Timefulness). Let A be the algebra of primitive states at a given stage. The universe is said to be timeful if the next state of the universe cannot be expressed using elements of A alone, but requires the admission of a genuinely new primitive element.

Definition 3 (Minimal Innovation). An innovation is minimal if the enlarged algebra B is the smallest extension of A that contains such a new primitive element and remains closed under the algebraic operations forced by finitude.

Lemma 4 (Quadratic Extension as Minimal Innovation).

Let be a symmetry–complete prime shell. Under minimal innovation, the smallest algebraic extension admitting a new primitive element is a quadratic field extension

Proof. Finite field extensions of have degree . The smallest nontrivial extension has degree , yielding . □

Lemma 5 (Temporal Involution).

The quadratic extension admits a unique nontrivial –automorphism

which satisfies and fixes pointwise.

Proof. The Galois group is cyclic of order n, generated by the Frobenius map. A nontrivial involution therefore exists only when n is even; the minimal such case is . □

Remark 2. The involution τ is the algebraic expression of temporal polarity: it distinguishes the original shell A from the newly introduced component of the extension. Its existence is not postulated but follows necessarily from timefulness under finitude and minimal innovation.

Timefulness therefore requires a structural involution

that cannot be realised within the cyclic successor structure or by any Euclidean symmetry internal to

.

With spatial reversal

and temporal reflection

both present, and with

p odd, these involutions commute:

The universe therefore inherits the symmetry group

the Klein four-group.

This Klein symmetry is not an additional assumption but the necessary closure of the involutions forced by finitude and timefulness. Its generic orbits have four elements, governing the irreducible innovation packets and the minimal shell enlargement

derived in

Section 5.

Timefulness ⇒ existence of a structural involution distinct from spatial reversal ⇒ minimal support in the quadratic extension .

In summary, timefulness introduces a temporal polarity that cannot be realised within the Euclidean cyclic shell, even when that shell contains an internal imaginary unit. The quadratic extension and Frobenius conjugation arise as the unique minimal algebraic realisation of this requirement, and together with spatial reversal generate the Klein symmetry governing all further structural evolution.

5. Quadratic Extension, Klein Symmetry, and Shell Growth

Having established that finitude forces a cyclic additive structure and that timefulness forces the quadratic extension together with an independent temporal involution, we now derive the algebraic consequences of the resulting symmetry structure. We show that the coexistence of spatial and temporal involutions forces Klein symmetry, whose orbit structure governs the minimal enlargement of the state space under innovation.

Definition 4 (Klein Symmetry).

Let denote the spatial involution forced by finitude and the temporal involution forced by timefulness. The symmetry group generated by is

the Klein four-group.

Lemma 6 (Commutativity of Involutions). For odd prime p, the involutions R and τ commute.

Proof. Since , one has . □

The Klein group is not introduced by fiat but arises as the minimal closure of the universe under the involutions forced independently by finitude and timefulness.

Definition 5 (Nondegenerate Element). An element is called nondegenerate if it is fixed by neither τ nor .

Lemma 7 (Klein Orbit Structure).

Let be nondegenerate. Its orbit under has cardinality four:

The degeneracy set consists precisely of the fixed field and the trace-zero -subspace , with intersection .

Proof. An orbit has cardinality less than four if and only if or . The first condition identifies , the second the trace-zero subspace. Their intersection is . Counting yields degenerate elements and nondegenerate elements. □

On the norm-one multiplicative subgroup, where

, one has

, and a canonical representative of a generic orbit is

Lemma 8 (Minimal Innovation Increment). Assume an innovation introduces a new nondegenerate element (Definition 5). Then any minimal innovation introduces exactly one four-element Klein orbit into the state space.

Proof. A genuinely new element cannot be admitted in isolation: closure under the forced symmetries requires inclusion of its entire Klein orbit . In the nondegenerate case, Lemma 7 gives , and no smaller subset preserves invariance under . □

Corollary 5 (Minimal Shell Enlargement).

If the current shell contains q residues, then any minimal innovation step requires

Corollary 6 (Linear Shell Growth).

If the universe evolves by incorporating one minimal innovation at each step, the shell cardinalities satisfy

The additive constant is fixed by the presence of the distinguished zero element and by the requirement of odd parity, ensuring that spatial reversal is well-defined.

Definition 6 (Symmetry-Complete Shell). A shell is symmetry-complete when is prime with , so that contains an element i satisfying and admits the internal Euclidean symmetries of the FRC construction.

Such shells embed canonically into their quadratic extensions , where the temporal involution becomes available. By Dirichlet’s theorem, the progression contains infinitely many symmetry-complete stages.

Remark 3. These stages underpin the innovation-consolidation cycle discussed in Section 8: innovation accesses the quadratic extension, while consolidation incorporates its invariants into the next Euclidean shell.

Finitude ⇒ spatial involution.

Timefulness ⇒ temporal involution.

Together ⇒ Klein symmetry ⇒ fourfold innovation.

In summary, the coexistence of finitude and timefulness forces Klein symmetry, four-element innovation packets, and the linear shell growth law. None of these features are adjustable; they arise inevitably from the structural commitments established earlier. This forced structure forms the final input to the Uniqueness Theorem of

Section 6.

6. The Uniqueness Theorem

The coexistence of spatial reversal R and temporal reflection generates the Klein four-group, forcing four-element innovation packets and the minimal shell enlargement . We now show that these consequences determine the algebraic architecture of the universe, in the precise sense that any finite, attribute-free, timeful universe must realise the same shell hierarchy (up to representation).

At this point all structural degrees of freedom introduced by the existence axiom have been exhausted. Any alternative finite construction would necessarily fail to satisfy at least one of the derived requirements—finitude, attribute-freeness, or timefulness—and therefore cannot represent a knowable primitive domain. The following theorem formalizes this closure.

Theorem 1 (Uniqueness of the Finite Ring Continuum).

Let be the primitive state space of a universe satisfying the Fundamental Axiom of Existence, interpreted operationally as in Section 2. Then:

-

(1)

Finite knowability

implies that admits a finite cyclic representation, hence for some q.

-

(2)

Spatial reversal

is forced by the absence of intrinsic orientation: there exists an involution R that exchanges forward and backward enumeration. In a chosen coordinatization one may write , uniquely up to translation of the cycle.

-

(3)

Temporal polarity

requires a structural involution τ that is distinct from the spatial symmetry forced by finitude. In particular, when a shell is a prime field , no such nontrivial involutive field automorphism exists within .

-

(4)

Minimal finite-field support for temporal reflection:

among finite field extensions of , the smallest extension admitting a nontrivial involution is the quadratic field , whose unique nontrivial -automorphism is the Frobenius involution . We identify .

-

(5)

-

Klein symmetry and four-element packets:

in with p odd, the maps and commute and generate

Every element outside the degeneracy set belongs to a four-element orbit.

-

(6)

Minimal innovation implies linear shell growth:

if at each innovation step the universe adjoins the smallest number of new primitive states required to remain closed under the Klein action, then each innovation contributes one nondegenerate four-element orbit and the shell sizes obey

-

(7)

-

Uniqueness (shell hierarchy):

up to representation, the resulting time-indexed primitive state space is determined by the graded family of symmetry shells

where the grade t records the innovation stage. For bookkeeping, one may realise this grading as the disjoint union , but the relevant structure is the grading by t, not a literal set-theoretic union.

Thus, within the class of finite, attribute-free universes whose evolution is timeful and whose innovation is minimal in the above sense, the Finite Ring Continuum is uniquely determined.

Proof of Theorem 1. We indicate how each item follows from the results established in Section 3, Section 4 and

Section 5.

(1) Finite knowability is formalised by the existence of a reversible enumeration (Definition 1). Lemma 1 then yields .

(2) Lemma 2 gives the forced spatial involution (unique up to translation) in any coordinatization.

(3) Temporal polarity is the content of Corollary (Timefulness) in

Section 2. In particular, a nontrivial involutive

field automorphism cannot exist inside a prime shell: any field automorphism of

fixes 1 and hence all of

.

(4) Lemmas 4 and 5 show that the smallest finite-field support for a distinct involution is the quadratic extension , with the unique nontrivial –automorphism .

(5) Lemma 6 gives commutativity of R and , hence Klein symmetry. Lemma 7 identifies the four-element orbit structure outside the degeneracy set.

(6) Under the nondegeneracy hypothesis, Lemma 8 forces each innovation to contribute an entire four-element Klein orbit. Corollary 6 then yields and .

(7) Items (1)–(6) determine a unique time-indexed shell hierarchy. This is naturally expressed as a graded family of shells , unique up to representation. (For bookkeeping, one may realise the grading as the disjoint union .) □

The temporal involution derived in this reconstruction is algebraic rather than dynamical: it expresses the polarity of temporal experience, not reversibility of physical evolution. This resolves the apparent tension with earlier FRC work, where Euclidean conjugation existed inside but did not represent time. Temporal reflection requires a distinct involution, and the quadratic extension is the minimal finite-field domain supporting it. From this involution, Klein symmetry and the linear shell law follow under minimal innovation. Thus the Finite Ring Continuum is not an imposed algebraic framework but the unique minimal universe compatible with finite knowability and temporal polarity.

7. Examples

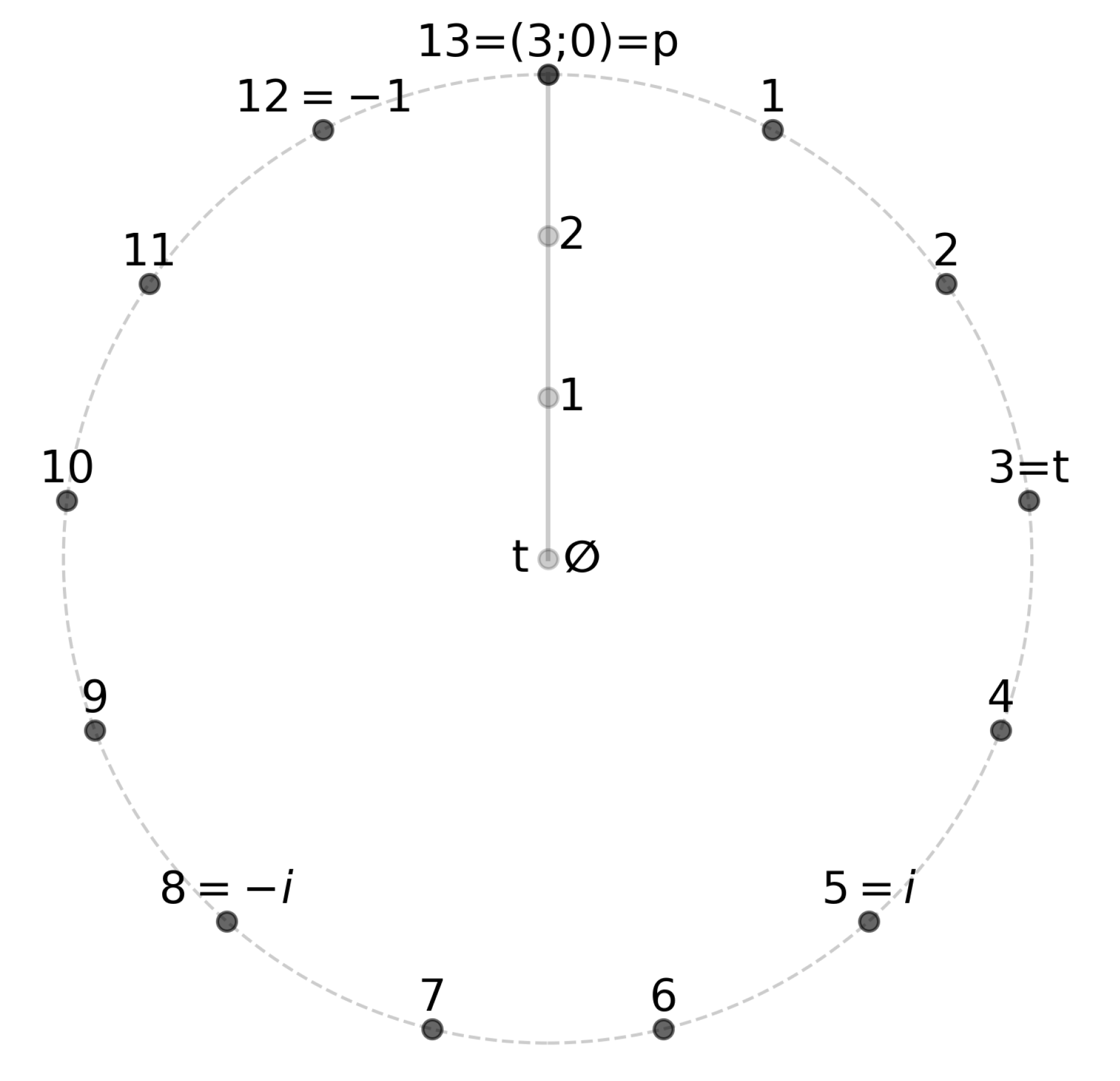

To complement the abstract reconstruction presented in the preceding sections, we now illustrate the forced algebraic structure of the Finite Ring Continuum with explicit finite-field example of

illustrated in

Figure 2. This example demonstrate concretely how the quadratic extension, the temporal involution, the Klein symmetry, and the fourfold innovation packets arise in practice. They also illustrate the minimal shell enlargement

required by the Uniqueness Theorem (Theorem 1).

We consider the symmetry-complete prime shell

, where

. The quadratic residues modulo 13 are

and the quadratic nonresidues are

Choose

as a quadratic nonresidue. The corresponding quadratic extension is

and we denote by

c the image of

X. Every element of

admits a unique representation

Since

is irreducible over

, its two roots

lie in

and are exchanged by the Frobenius automorphism

, which fixes

pointwise. Consequently,

, and for any

one has

The temporal involution is therefore the Frobenius map

which acts as a discrete conjugation. Spatial reversal is given by

. The four algebraically forced states associated with

z are thus

For a generic element these four states are distinct and form a four-element orbit under the Klein group generated by R and . Such an orbit cannot be partially realized: relational completeness requires that it appear as an inseparable packet.

Four-Element Klein Orbit.

As a concrete illustration, take

Then

and the full orbit generated by

R and

is

All four elements are distinct, in accordance with the Klein symmetry.

This example illustrates the central conclusion of

Section 5:

innovation introduces structure only in four-element packets, never singly. The minimal enlargement required to accommodate a new nondegenerate orbit is therefore

elements.

Shell Enlargement.

Let the initial symmetry-complete shell be

, with cardinality

. The next shell capable of hosting one additional nondegenerate Klein orbit must contain at least four further residues, giving the minimal enlargement

The number 17 is prime and satisfies

, making it the next symmetry-complete shell. Dirichlet’s theorem guarantees that the progression

contains infinitely many primes, ensuring the continued availability of symmetry-complete shells.

To summarize, this example makes concrete the logical chain culminating in the Uniqueness Theorem:

Timefulness forces the quadratic extension.

The two involutions generate Klein symmetry.

Klein symmetry forces fourfold innovation packets.

Fourfold packets force linear shell enlargement by .

Repetition of this minimal enlargement yields the canonical shells .

No modelling decisions enter the construction; the algebraic behaviour observed in is a concrete instance of the forced structure underlying all finite timeful universes. The Finite Ring Continuum therefore emerges not as an engineered model but as the unique algebraic realisation of the phenomenology of finitude and evolution.

8. Discussion

The Uniqueness Theorem establishes that the Finite Ring Continuum is not an axiomatically postulated algebraic environment but the unavoidable consequence of the phenomenological commitments of finitude and timefulness. In this section we elaborate on the conceptual implications of this result and situate the Finite Ring Continuum within broader scientific and epistemic contexts.

FRC as a Forced Algebraic Universe.

The foundational observation of this work is that once primitive reality is taken to be finite and attribute-free, the only admissible representation of the state space is a homogeneous finite cycle, and hence a finite cyclic group. Likewise, once evolution is required to be meaningful and reversible, temporal reversal must emerge as a symmetry distinct from spatial reversal. These two phenomenological requirements have immediate algebraic consequences: the cyclic group must extend to the quadratic field , and the two involutions R and necessarily generate a Klein symmetry. No alternative algebraic structure satisfies these constraints.

Thus, the architecture of the Finite Ring Continuum does not arise from selecting a convenient mathematical formalism. Rather, it emerges uniquely from the only two features that make a universe knowable and evolving. Every structural element of FRC—cyclic enumeration, complex-like conjugation, fourfold innovation orbits, and linear shell growth—appears as a forced consequence of these commitments.

Unlike axiomatic systems, which begin by postulating mathematical structure, the present reconstruction derives structure from the conditions under which any such postulates could be meaningful. The Finite Ring Continuum therefore operates at a deeper epistemic level: it is not a theory within mathematics, but a derivation of the algebra necessary for mathematics, physics, and experience to be possible at all.

Innovation-Consolidation Principle.

The algebraic reconstruction developed here reveals a deep structural pattern in the evolution of finite universes. Innovation corresponds to accessing the quadratic extension , where new invariants become expressible. Consolidation corresponds to the forced reduction back to the Euclidean shell, where each new invariant must appear in a four-element orbit and hence enlarge the shell only by the minimal increment of four residues.

This expansion–compression cycle mirrors the abstract structure of learning systems, both biological and artificial [

19,

20,

21,

22]. In such systems, a surprising observation triggers a temporary expansion of the representational domain, enabling new latent features to be expressed; subsequently, these features are consolidated into a stable and compact form. The Finite Ring Continuum provides the algebraic counterpart of this principle: innovation expands the algebraic domain to

, while consolidation compresses the new structure into a minimal fourfold packet in the next shell.

Implications for Discrete Physics and Causality.

The quadratic extension plays a role analogous to the complex field in continuum physics, where complex conjugation is intimately associated with time reversal, phase, and causal propagation. The emergence of a conjugation-like involution in the finite setting therefore provides an algebraic origin for causal and temporal structure. This aligns with the observation that Dirac-like dynamics requires the availability of both real and conjugate components, a condition satisfied naturally in .

Moreover, the forced shell growth law provides a discrete analogue of cosmological unfolding: new structural degrees of freedom appear in irreducible four-element packets, and the universe expands at the minimal rate compatible with its symmetries. This offers a mathematically grounded mechanism for the accumulation of structure in a finite world.

Elementary Particles as Quanta of Symmetry.

In the present framework, primitive residues of the Finite Ring Continuum are not to be identified with physical particles. Primitive states are indistinguishable and attribute-free; they serve only as relational carriers within the finite algebraic substrate. Physical particles, by contrast, correspond to invariants—stable quanta of symmetry—rather than to individual primitive elements.

From this perspective, the four-element Klein orbits that arise generically in the quadratic extension

do not represent four distinct particles, but a single symmetry quantum with four algebraically related manifestations. The quadruplet

constitutes a minimal invariant under the combined action of spatial reversal

R and temporal reflection

. Interpreted physically, this structure mirrors the organization of relativistic state spaces into particle, antiparticle, and their time-reversed counterparts.

This correspondence is structural rather than identificatory. The theory does not assign particle ontology to individual residues, nor does it derive particle dynamics. Rather, it suggests that particle-like degrees of freedom emerge as symmetry classes within a finite, attribute-free algebraic universe. In this sense, particles appear as quanta of symmetry rather than as primitive constituents, allowing them to be distinguishable even though the underlying residues remain indistinguishable.

Conceptual Significance.

The results presented here suggest that the Finite Ring Continuum is not one among many possible discrete models of physical reality. Rather, it is the unique algebraic universe compatible with the phenomenological preconditions of finitude and evolution. By showing that no further structure can be added or removed without violating these commitments, the Uniqueness Theorem offers a principled justification for the FRC framework and situates it within a wider discourse on relational physics, causality, and the emergence of information.

The innovation–consolidation cycle extends this perspective, demonstrating that the evolution of structure in a finite universe follows a universal pattern of expansion and compression. This principle appears across biological learning, computational adaptation, and now finite algebraic cosmology, suggesting that discrete evolution may ultimately be governed by a small number of deep and unified organisational laws.

9. Conclusions

This work has demonstrated that the algebraic architecture of the Finite Ring Continuum arises not from discretionary modelling choices but from two phenomenological commitments that are indispensable for the existence of a knowable and evolving universe: finitude and timefulness. Finitude requires that primitive states be indistinguishable and closed under reversible enumeration, forcing a cyclic additive structure. Timefulness requires a reversible temporal symmetry independent of spatial reversal, forcing the minimal algebraic extension that admits such a symmetry: the quadratic finite field with its unique nontrivial involution. Together, these commitments generate the Klein four-group as the symmetry core of the universe, impose four-element orbit structure on emerging invariants, and necessitate the minimal linear shell growth law .

The Uniqueness Theorem formalises this chain of implications and establishes that any universe consistent with finitude and timefulness is uniquely isomorphic to the shell hierarchy of the Finite Ring Continuum. Every structural feature—cyclic enumeration, spatial reversal, temporal conjugation, quadratic innovation, fourfold consolidation, and linear shell expansion—arises as an unavoidable consequence of these commitments. No supplementary primitives, structural parameters, or ad hoc principles are introduced; the entire framework is forced by the minimal conditions under which a finite subject can encounter an evolving world.

Beyond establishing the uniqueness of the FRC, the analysis also reveals a universal organisational principle: the evolution of structure in a finite universe follows a rhythm of innovation and consolidation. Innovation corresponds to the temporary expansion into the quadratic extension, where new invariants become expressible; consolidation corresponds to the irreducible compression of these invariants into four-element orbits that advance the shell structure by the minimal increment. This expansion–compression pattern echoes structural learning in biological and computational systems, suggesting that the innovation–consolidation cycle may be a deep organising law of finite representational systems.

The Finite Ring Continuum therefore stands as a uniquely determined algebraic universe—neither posited nor engineered, but uncovered by tracing the necessary consequences of finite knowability and temporal evolution. We expect that further exploration of invariant families, shell dynamics, and Lorentzian structure within this framework will illuminate additional aspects of discrete physics, learning, and emergence, and we view the Uniqueness Theorem as a foundational step toward a comprehensive finite-algebraic account of structure and evolution.

References

- Descartes, R. Meditations on First Philosophy; Michael Soly: Paris, 1641. Original Latin edition; English translation available in modern editions.

- Noether, E. Invariant variation problems. Transport Theory and Statistical Physics 1971, 1, 186–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtman, Y. Euclidean–Lorentzian Dichotomy and Algebraic Causality in Finite Ring Continuum. Entropy 2025, 27, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akhtman, Y. Relativistic Algebra over Finite Ring Continuum. Axioms 2025, 14, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtman, Y. Schrödinger–Dirac Formalism in Finite Ring Continuum. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbour, J. The End of Time; Oxford University Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rovelli, C. Relational Quantum Mechanics. International Journal of Theoretical Physics 1996, 35, 1637–1678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladyman, J.; Ross, D. Every Thing Must Go: Metaphysics Naturalized; Oxford University Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, L. Quantum Theory From Five Reasonable Axioms. arXiv 2001, arXiv:quant-ph/0101012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiribella, G.; D’Ariano, G.M.; Perinotti, P. Informational Derivation of Quantum Theory. Physical Review A 2011, 84, 012311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, C.A.; Mermin, N.D.; Schack, R. An Introduction to QBism with an Application to the Locality of Quantum Mechanics. American Journal of Physics 2014, 82, 749–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masanes, L.; Müller, M.P. A Derivation of Quantum Theory From Physical Requirements. New Journal of Physics 2011, 13, 063001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, J.A. Information, Physics, Quantum: The Search for Links. In Complexity, Entropy, and the Physics of Information; Zurek, W.H., Ed.; Addison-Wesley, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sorkin, R.D. Causal Sets: Discrete Gravity. arXiv:gr-qc/0503027 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, B.; Westmoreland, M. Quantum Processes, Systems, and Information; Cambridge University Press, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtman, Y. Paradoxes of Infinity as Reductio ad Absurdum. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeilberger, D. “Real” Analysis is a Degenerate Case of Discrete Analysis. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Difference Equations (ICDEA 2001).

- Lev, F. Finite Mathematics as the Foundation of Classical Mathematics and Quantum Theory; Springer International Publishing, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friston, K. The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory? Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2010, 11, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, A. Whatever next? Predictive brains, situated agents, and the future of cognitive science. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 2013, 36, 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schultz, W.; Dayan, P.; Montague, P.R. A neural substrate of prediction and reward. Science 1997, 275, 1593–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gershman, S.J.; Niv, Y. Novelty and inductive generalization in human reinforcement learning. Topics in Cognitive Science 2015, 7, 391–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).