Submitted:

14 December 2025

Posted:

15 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Background

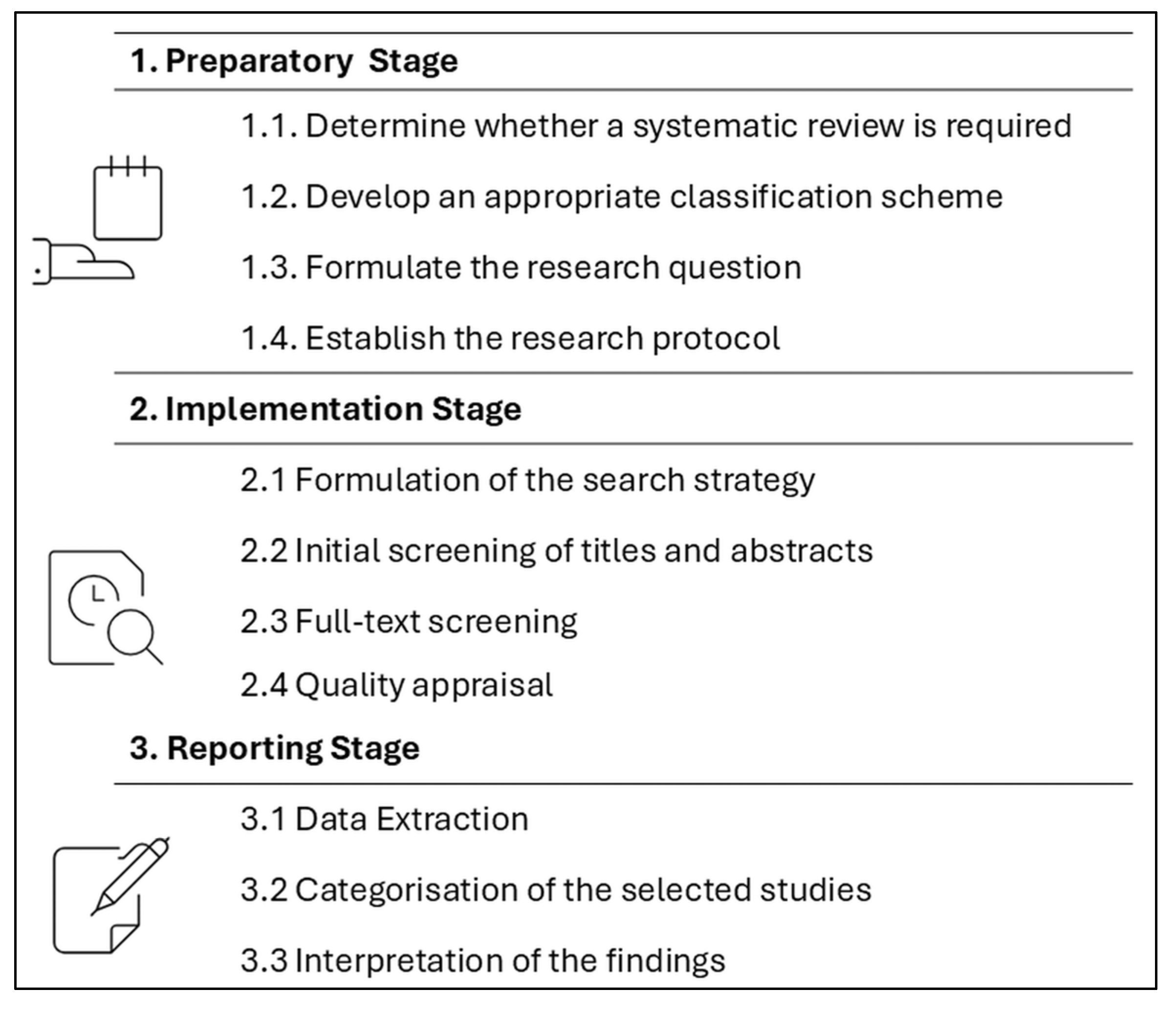

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Preparatory Stage

3.1.1. Determine Whether a Systematic Review Is Required

3.1.2. Develop an Appropriate Classification Scheme

3.1.3. Formulate the Research Question

3.1.4. Establish the Research Protocol

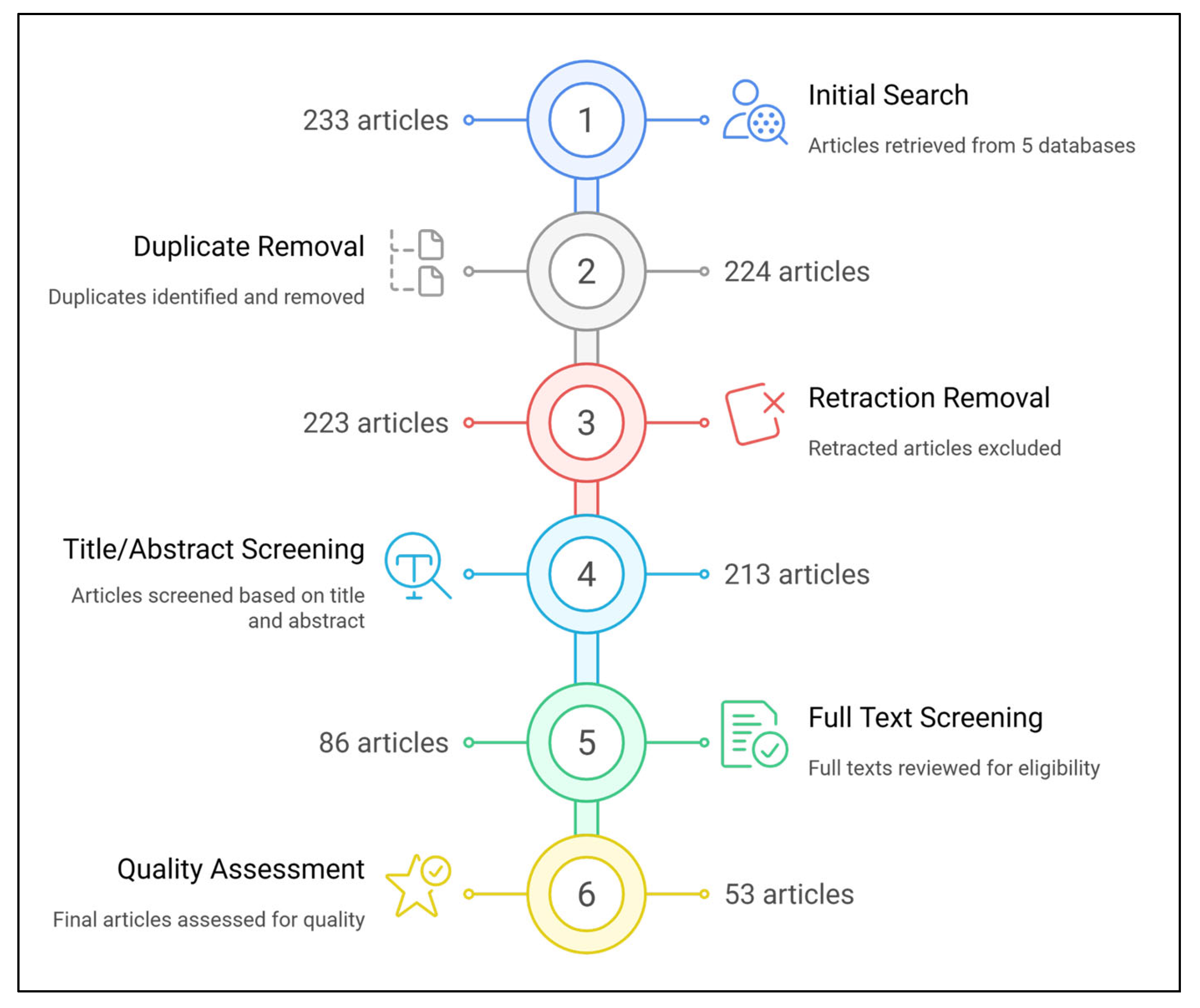

3.2. Implementation Stage

3.2.1. Formulation of the Search Strategy

3.2.2. Initial Screening of Titles and Abstracts

3.2.3. Full-Text Screening

3.2.4. Quality Appraisal

3.3. Reporting Stage

3.3.1. Data Extraction

4. Results

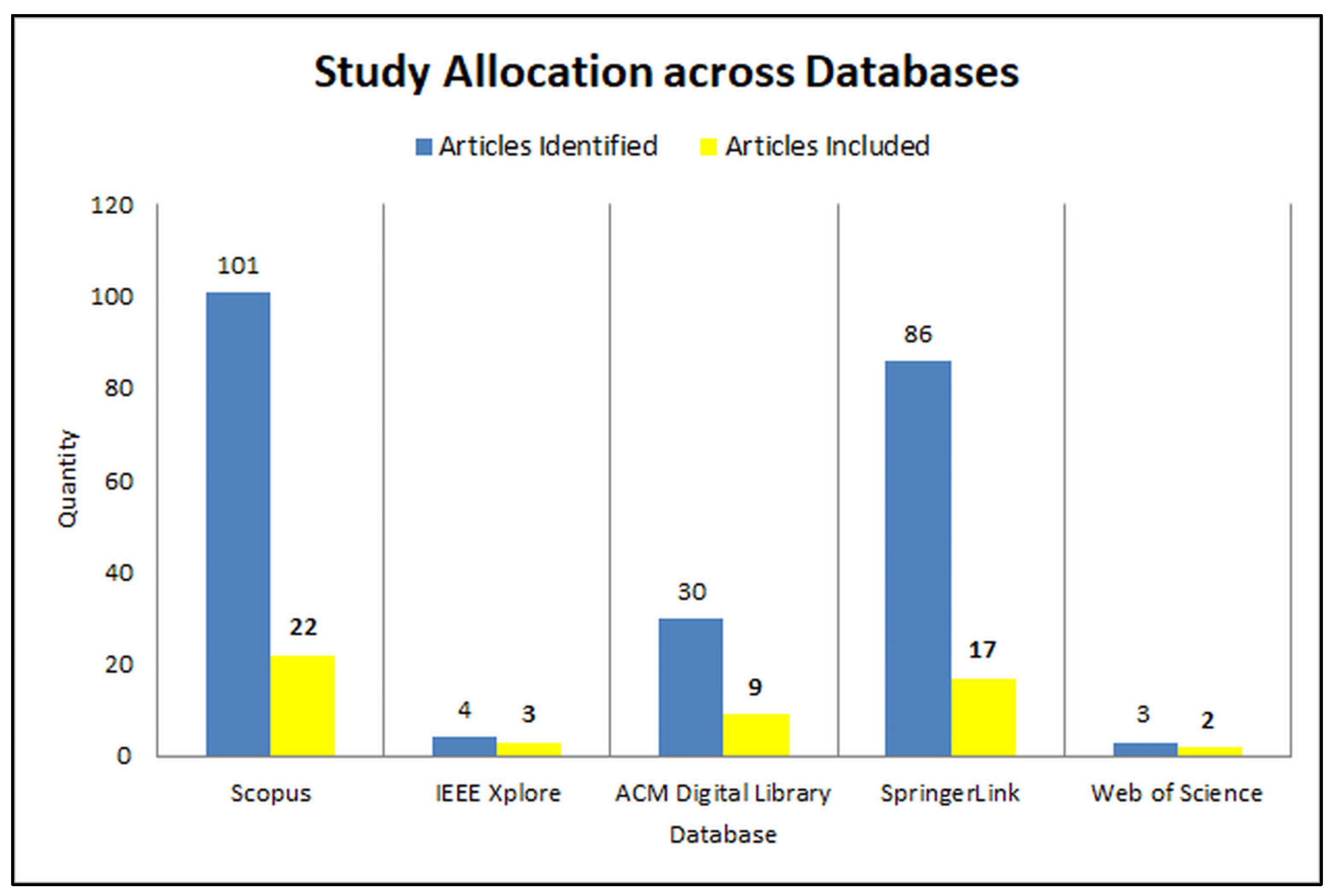

4.1. Database-Wise Distribution of the Selected Studies

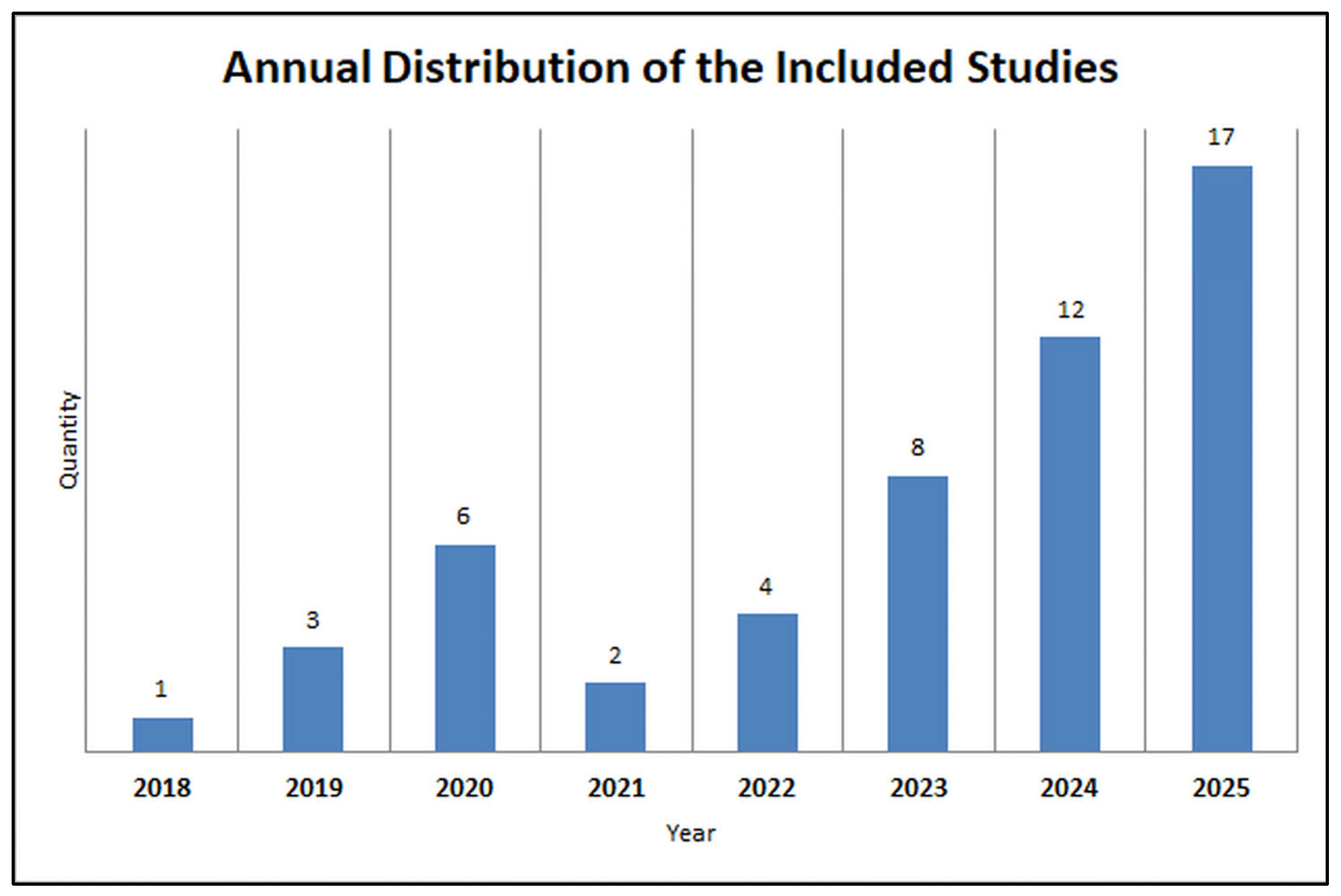

4.2. Publication Year Distribution of the Selected Studies

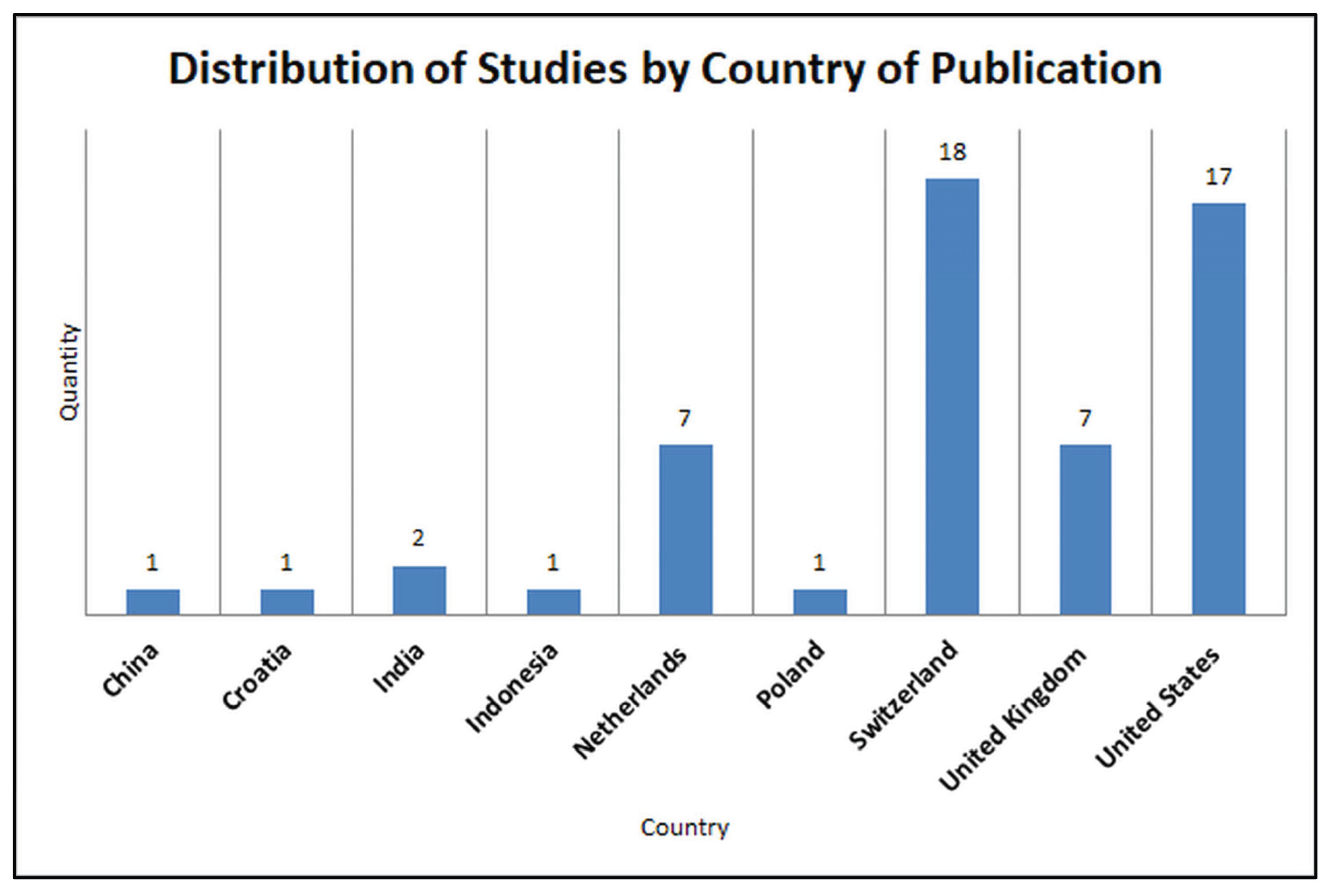

4.3. Distribution of Studies by Country of Publication

4.4. Summary of Institutional Affiliations by Continent

4.5. Publications by Authors

4.6. Research Classification Framework

4.6.1. (RQ1) Dimension: AI Applications

- 1.

- Food Recognition, Classification and CV

- 2.

- Recipe Generation, Transformation and Creativity Support

- 3.

- Recommender Systems for Food, Ingredients and Nutrition

- 4.

- Nutrition Assessment, Dietary Monitoring and Health

- 5.

- Cooking Assistance, Automation and Domestic Robotics

- 6.

- Food Culture, Heritage and Culinary Knowledge Discovery

- 7.

- Smart Kitchens, IoT, Retail and Food Service

- 8.

- Cross-domain Applications and Miscellaneous

4.6.2. (RQ2) Dimension: AI Methodologies and Techniques

- 1.

- Computer Vision

- 2.

- Natural Language Processing

- 3.

- Graph-based Modelling

- 4.

- Recommender Systems

- 5.

- Multimodal Deep Learning

- 6.

- Reinforcement Learning

- 7.

- Traditional ML

- 8.

- IoT, Sensors and Embedded Systems

- 9.

- Robotics and Manipulation

4.6.3. (RQ3) Dimension: Data Resources, Standards and Development Frameworks

- 1.

- User-generated Data and Surveys

- 2.

- Public Food Image Datasets

- 3.

- Public Recipe and Multimodal Datasets

- 4.

- Large-Scale Multimodal Web Data

- 5.

- Chemical, Nutritional and Biomedical Databases

- 6.

- Ontologies, Knowledge Graphs and Linked Data

- 7.

- Standards, Guidelines and Annotation Protocols

- 8.

- Software Frameworks and Infrastructure

- 9.

- Development Frameworks and Experimental Pipelines

4.6.4. (RQ4) Dimension: Challenges and Emerging Trends

- 1.

- Limitations in Data, Annotation and Benchmarking

- 2.

- Multimodal, Sensorial and Cross-modal Integration Challenges

- 3.

- Model Generalisation, Cultural Transfer and Cross-domain Robustness

- 4.

- Evaluation, Validation and Real-world Deployment

- 5.

- Interaction, Interfaces and Usability Issues

- 6.

- Standards, Ethical, Privacy and Sustainability Constraints

4.7. Research Implications, Limitations, and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CG | Computational Gastronomy |

| CV | Computer Vision |

| DG | Digital Gastronomy |

| DH | Digital Health |

| DL | Deep Learning |

| FS | Food Science |

| IMRaD | Introduction, Methods, Results and Discussion |

| ML | Machine Learning |

| NLP | Natural Language Processing |

| Q | Question |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| RQ | Research Question |

| USDA | United States Department of Agriculture |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Category | AI applications reported | Study/Ref. |

| Food Recognition, Classification and Computer Vision | Detection and analysis of food attributes in digital interfaces, supporting personalised dining experiences. | [60] |

| Food and beverage recognition in digital menus and personalised gastronomic interfaces. | [61] | |

| Multi-label recognition of Chinese dishes and ingredients for nutritional and culinary analysis. | [7] | |

| Recognition of food items and user-tailored metadata such as allergenicity and expiration. | [62] | |

| Recipe Generation, Transformation and Creativity Support | Automatic summarisation of cooking videos and generation of stepwise recipe instructions to support learning and accessibility. | [6] |

| Survey of AI-based recipe generation models (Ratatouille, Cook-Gen, FIRE); flavour modelling, taste prediction, health-oriented personalisation and sustainability. | [4] | |

| Summarisation of cooking videos and extraction of essential procedural steps for learning support. | [3] | |

| Recipe generation using unusual ingredients for creative menu development and culinary ideation. | [95] | |

| Full recipe generation including seasoning and oil usage; creativity assessment through graph dissimilarity. | [11] | |

| Adaptation of recipes for general, vegetarian and vegan diets through nutritional modelling. | [64] | |

| Generation of recipe sentences from cooking videos (YouCookII) to support understanding and searchability. | [63] | |

| Scientific and creative applications of generative models, including recipe generation. | [96] | |

| Image-to-recipe generation and cross-modal retrieval in large-scale food datasets. | [94] | |

| Recommender Systems for Food, Ingredients and Nutrition | Recommender systems for recipes based on ingredient availability and user preferences, supporting home cooks. | [8] |

| AI-based food pairing and flavour compound prediction, enabling discovery of novel ingredient combinations. | [65] | |

| Recommendation of recipes, menus and meal plans for personalised nutrition and health. | [10] | |

| Tag- and user-item-based recommendation of cooking videos, balancing accuracy and creativity. | [68] | |

| Low-fat meal planning with calorie estimation and personalised recommendations. | [66] | |

| Recipe recommendation in food-sharing platforms integrating ingredient-combination preferences and calorie levels. | [67] | |

| Food recommendations for dishes, meal plans and restaurants integrating dietary restrictions. | [63] | |

| Recipe recommendation from images or ingredient lists with QA on equipment, timing and substitutions. | [70] | |

| Nutrition Assessment, Dietary Monitoring and Health | Dietary assessment, nutritional analysis and intelligent food service management systems. | [71] |

| Multimodal food diaries for calorie monitoring, health management and behavioural awareness. | [9] | |

| Personalised dietary management for peritoneal dialysis patients with weekly nutritional planning. | [72] | |

| Meal-planning system for pregnant women using five nutritional groups to prevent stunting. | [73] | |

| Mobile app FRANI for healthy-eating nudges in adolescents using gamified feedback and consumption tracking. | [74] | |

| Acceptance analysis of personalised dietary counselling among users with different dietary constraints. | [75] | |

| Impact of behavioural nudges and personalised recommendations on healthy-eating adherence. | [76] | |

| Cooking Assistance, Automation and Domestic Robotics | Automated cooking of rice and beans, remote and local control of meal preparation, support for older adults and people with disabilities. | [12] |

| Interactive cooking assistance, step-by-step recipe guidance, real-time hazard detection (fire), support for older adults and users with cognitive impairment. | [22] | |

| Robot-assisted preparation and frying of food, including manipulation of chicken and shrimp pieces. | [13] | |

| Recognition of ingredients on the counter and real-time recipe guidance using augmented video overlays. | [35] | |

| Monitoring of cooking habits, health-related food behaviour and real-time culinary support. | [77] | |

| Food Culture, Heritage and Culinary Knowledge Discovery | Analysis of Catalan culinary heritage, identification of core recipes and culinary communities, support for personalised recommendation and gastronomic innovation. | [78] |

| Classification of culinary styles and regions using heterogeneous recipe data. | [79] | |

| Smart Kitchens, IoT, Retail and Food Service | Kitchen monitoring system for objects, temperature and access events using battery-free sensing. | [14] |

| Smart kitchen safety system detecting toxic gases and hazardous volatiles. | [80] | |

| Activity-of-daily-living monitoring for older adults in smart kitchens, with inference of sub-activities. | [81] | |

| Smart kitchen recognition of utensils, boiling water, steam and smoke, adjusting heat and suggesting cookware. | [15] | |

| Order-management system for restaurant delivery, predicting preparation and delivery times. | [82] | |

| Smart kitchen simulator identifying depression based on ingredients selected for meals. | [83] | |

| Cross-domain Applications and Miscellaneous | Cross-domain applications including health, agriculture, sensory science and food quality management. | [27] |

| Automated dietary assessment and food logging in intelligent cooking environments. | [85] | |

| Mapping of AI applications in ingredient pairing, cuisine evolution, health associations and recipe generation. | [84] | |

| Mapping of food-related AI applications: ingredient substitution, flavour prediction, and healthy replacements. | [5] | |

| Food-quality assessment systems applied to pork and beef cuts in various processing states. | [90] | |

| Food-quality analysis of tea leaves, commercial teas, beverages and bakery products. | [91] | |

| Visual food recognition, recipe retrieval, nutritional estimation and smart-appliance support. | [88] | |

| Improvement of search and recommendation in recipe databases through personalisation. | [89] | |

| Quality assurance in the meat sector using AI to predict physicochemical and sensory parameters. | [92] | |

| Digital food journaling, smart retail and food-waste monitoring. | [86] | |

| Automated food logging, dietary assessment and nutrition-oriented applications. | [87] | |

| AI applications for tea-related products such as classification, safety and quality control. | [93] |

Appendix A.2

| Category | AI methodologies and techniques | Study/Ref. |

| Computer Vision | Deep learning–based food image analysis (CNNs, object detection, segmentation), visual quality assessment, dish and ingredient recognition, and video-based procedural understanding. | [3,6,7,9,13,15,27,35,60,61,62,63,64,69,75,79,81,85,87,88,90,92,94] |

| Natural Language Processing | Transformer-based recipe modelling, textual representation and semantic extraction, automated recipe generation and summarisation, conversational and retrieval-based culinary NLP. | [4,5,6,11,63,64,66,69,71,73,79,89,94,95] |

| Graph-based Modelling | Construction and analysis of food-related networks (recipe similarity graphs, flavour networks, ingredient co-occurrence graphs), graph embeddings and structural modelling for culinary knowledge discovery. | [5,8,11,65,67,70,71,78,79,91,94] |

| Recommender Systems | Hybrid, collaborative and content-based recommendation; context- and ingredient-aware matching; graph-enhanced recommenders; multi-criteria and health-oriented recommendation models. | [5,8,10,13,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,73,74,76,89,94] |

| Multimodal Deep Learning | Joint modelling of images, videos and text through unified embedding spaces, multimodal fusion, cross-modal retrieval and video-to-recipe or recipe-to-image alignment. | [3,6,63,64,79,88,94] |

| Reinforcement Learning | RL for optimising sequential decisions in restaurant workflows, including delivery timing, kitchen scheduling and resource allocation. | [82] |

| Traditional ML | Classical classification and regression (SVM, Random Forest, KNN, logistic regression), statistical clustering and pattern mining, food quality prediction and user modelling. | [5,11,14,74,76,77,81,83,89,92,96] |

| IoT, Sensors and Embedded Systems | Sensor-rich IoT architectures for real-time kitchen monitoring, environmental safety systems, smart appliances, and embedded microcontroller-based food sensing. | [12,14,22,60,77,80,86] |

| Robotics and Manipulation | Robotic cooking and automated manipulation, including vision-guided handling, ingredient placement, and task automation in food preparation. | [12,22,35] |

Appendix A.3

| Category | Data resources, standards and development frameworks | Study/Ref |

| User-generated Data and Surveys | User surveys, questionnaires and preference reports | [12,68,74] |

| Sensory evaluation forms and manual annotation sheets | [27,67] | |

| Participant-contributed experimental data | [22,80] | |

| Internal curated recipe collections | [8,10,78] | |

| In-house laboratory experiments | [22,60,85] | |

| Custom multimodal datasets | [65,79] | |

| Proprietary sensor-based datasets | [71,73,95] | |

| Custom video recordings of cooking tasks | [3,66] | |

| In-house dataset of 84 dishes | [77] | |

| Calibrated food image dataset | [75] | |

| MRI-based food image dataset | [92] | |

| Controlled participant experiments | [62] | |

| Narrative review (no datasets) | [86] | |

| Simulated food intake dataset | [83] | |

| Extracted recipes and symptoms | [93] | |

| User–item interaction dataset | [70] | |

| Public Food Image Datasets | Food-101 | [6,9,64,88] |

| UEC-Food100 and UEC-Food256 | [6,14] | |

| UNIMIB2016 | [6] | |

| Fruits36, Fruits360, VegFru, ISIA-Food | [6,72,88] | |

| ETHZ Food-256 | [14] | |

| Large real-world annotated image datasets | [15] | |

| CAFSD (21,306 images) | [90] | |

| ChineseFood-200 | [7] | |

| MAFood-121 | [87] | |

| Public Recipe and Multimodal Datasets | Recipe1M and Recipe1M+ | [4,9,72,94] |

| RecipeDB, SpiceRx, FlavorDB, DietRx, FooDB | [4,5] | |

| Vireo Food and Vireo Recipes | [4] | |

| YouCook and YouCook2 | [3,61,63] | |

| MealRec | [64] | |

| Wikitable and Wikia | [11] | |

| Large-scale web recipe portals | [69,76] | |

| 3A2M+ | [89] | |

| Multimodal instruction corpora | [9,64] | |

| Large-scale Multimodal Web Data | Scraped culinary websites and blogs | [8,9,78] |

| Crawled multimodal collections | [9,72] | |

| Process logs and preparation steps | [82] | |

| Chemical, Nutritional and Biomedical Databases | USDA FoodData Central | [4,66] |

| CIQUAL, Phenol-Explorer, FooDB | [4] | |

| Laboratory nutrient and texture analyses | [22,60,85] | |

| Handbook of Medicinal Herbs | [91] | |

| Ontologies, Knowledge Graphs and Linked Data | FoodOn | [9] |

| Ingredient and recipe knowledge graphs | [8,9] | |

| Semantic food taxonomies and Linked Data | [96] | |

| Standards, Guidelines and Annotation Protocols | Image and video annotation protocols | [3,6] |

| Ingredient and nutritional tagging guidelines | [6,9] | |

| Sensory and experimental protocols | [67,85] | |

| Software Frameworks and Infrastructure | APIs and scraping tools | [8,9] |

| Database infrastructures | [8,78] | |

| Pre-processing pipelines | [9,72] | |

| Development Frameworks and Experimental Pipelines | Pipelines for food recognition and prediction | [6,9,72] |

| Multimodal fusion workflows | [9,72] | |

| Evaluation frameworks for cooking tasks | [66,95] |

Appendix A.4

| Category | Challenges and emerging trends (summary) | Study/Ref |

| Limitations in Data, Annotation and Benchmarking | Need for broader and more diverse datasets, improved annotation quality, insufficient availability of open data, and lack of standardised benchmarks that enable consistent performance comparisons across studies. | [3,5,6,9,10,13,14,15,35,61,63,64,69,70,73,75,76,77,79,80,82,83,84,87,88,89,90,92,93,94,95] |

| Multimodal, Sensorial and Cross-modal Integration Challenges | Difficulties in integrating heterogeneous modalities (image, text, audio, sensor signals), limited capacity to capture sensorial nuances, and challenges in aligning representations across modalities. | [4,7,8,9,11,65,66,68,71,72,74,81,86,91,96] |

| Model Generalisation, Cultural Transfer and Cross-domain Robustness | Limited robustness when transferring models across culinary cultures, ingredient rarities, and cooking styles; difficulties in adapting to new domains and ensuring generalisability. | [4,7,9,11,27,60,62,66,67,74,78,81,85,96] |

| Evaluation, Validation and Real-world Deployment | Lack of in vivo validation, limited objective evaluation, calibration issues, and constraints in deploying AI systems in real culinary environments. | [4,10,12,13,14,22,27,35,61,62,64,65,66,68,69,71,73,77,82,84,86,89,90,92] |

| Interaction, Interfaces and Usability Issues | Limited personalisation, constraints in assistive interfaces, challenges in human–machine interaction, and need for user-adaptive systems that support practical cooking scenarios. | [5,8,12,63,65,67,75,79,83,85,88,91,95] |

| Standards, Ethical, Privacy and Sustainability Constraints | Ethical and privacy concerns related to food and behavioural data, absence of harmonised standards, insufficient sustainability principles, and lack of secure data governance frameworks. | [3,4,14,15,60,69,70,73,80,94] |

References

- Zoran, A. Cooking With Computers: The Vision of Digital Gastronomy [Point of View]. Proceedings of the IEEE 2019, 107, 1467–1473. [CrossRef]

- Zoran, A.R. Digital Gastronomy 2.0: A 15-Year Transformative Journey in Culinary-Tech Evolution and Interaction. Int J Gastron Food Sci 2025, 39, 101135. [CrossRef]

- Nishimura, T.; Hashimoto, A.; Ushiku, Y.; Kameko, H.; Mori, S. Recipe Generation from Unsegmented Cooking Videos. ACM Transactions on Multimedia Computing, Communications, and Applications 2024. [CrossRef]

- Goel, G.B. Computational Gastronomy: Capturing Culinary Creativity by Making Food Computable. NPJ Syst Biol Appl 2024. [CrossRef]

- Goel, M.; Bagler, G. Computational Gastronomy: A Data Science Approach to Food. J Biosci 2022, 47, 12. [CrossRef]

- Sadique, P.M.A.; Aswiga, R. V. Automatic Summarization of Cooking Videos Using Transfer Learning and Transformer-Based Models. Discover Artificial Intelligence 2025, 5, 7. [CrossRef]

- He, R.Z.O.L.B.Z. Learning Multi-Scale Features Automatically from Food and Ingredients. Multimed Syst 2025. [CrossRef]

- Arora, U.N.R.G.A. Characterize Ingredient Network for Recipe Suggestion. International Journal of Information Technology 2019. [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.D.W.F.S. Deep Learning-Enhanced Food Ingredient Segmentation with Co-Occurrence Relationship Constraints. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization 2025. [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, P.; Kaur, P.D. A Systematic Literature Review of Food Recommender Systems. SN Comput Sci 2024, 5. [CrossRef]

- Santos, W.A. Dos; Bezerra, J.R.; Wanderley Goes, L.F.; Ferreira, F.M.F. Creative Culinary Recipe Generation Based on Statistical Language Models. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 146263–146283. [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.SharmaS.R.N. Design of Smart Automated Cooker: A Survey and Feasibility Study. Multimed Tools Appl 2024. [CrossRef]

- Majil, I.; Yang, M.T.; Yang, S. Augmented Reality Based Interactive Cooking Guide. Sensors 2022, 22. [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; Bringle, M.; Fahad, I.; Morales, G.; Zahid, A.; Swaminathan, S. NeuroCamTags: Long-Range, Battery-Free, Wireless Sensing with Neuromorphic Cameras. Proc ACM Interact Mob Wearable Ubiquitous Technol 2024, 8. [CrossRef]

- Azurmendi, I.; Zulueta, E.; Lopez-Guede, J.M.; Azkarate, J.; González, M. Cooktop Sensing Based on a YOLO Object Detection Algorithm. Sensors 2023, 23. [CrossRef]

- Bondevik, J.N.; Bennin, K.E.; Babur, Ö.; Ersch, C. A Systematic Review on Food Recommender Systems. Expert Syst Appl 2024, 238, 122166. [CrossRef]

- Babu, P.; Mounika, E.; Vani, G.; Madhu, B.O.; Sai Mohan, S.; Srinivas, J. Application of 3D Printing in Food Processing Industry. Futuristic Trends in Agriculture Engineering & Food Sciences Volume 3 Book 5 2024, 123–135. [CrossRef]

- Shah, P.; Shah, V.; Shrestha, S.; Mitra, P. A Review on 3D Food Printing Technology in Food Processing. Journal of Food Industry 2024, 8, 17. [CrossRef]

- Manivelkumar, K.N.; Kalpana, C.A. A Systematic Review on 3D Food Printing: Progressing from Concept to Reality. Amerta Nutrition 2025, 9, 176–185. [CrossRef]

- Simon, J.; Gogolák, L. From Digital Design to Edible Art: The Role of Additive Manufacturing in Shaping the Future of Food. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing 2025, 9, 217. [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Zhou, H.; Peng, S.; Lin, H.; Guo, H.; Shao, J.; Yang, P.; Yang, Q.; Miao, S.; He, X.; et al. Towards Depth Foundation Model: Recent Trends in Vision-Based Depth Estimation. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Bouchard, B.; Bouchard, K.; Bouzouane, A. A Smart Cooking Device for Assisting Cognitively Impaired Users. J Reliab Intell Environ 2020, 6, 107–125. [CrossRef]

- Ali, O.; Shrestha, A.; Soar, J.; Wamba, S.F. Cloud Computing-Enabled Healthcare Opportunities, Issues, and Applications: A Systematic Review. Int J Inf Manage 2018, 43, 146–158. [CrossRef]

- Wieringa, R.; Maiden, N.; Mead, N.; Rolland, C. Requirements Engineering Paper Classification and Evaluation Criteria: A Proposal and a Discussion. Requir Eng 2006, 11, 102–107. [CrossRef]

- Spence, C.; Velasco, C. Digital Dining. Digital Dining 2025. [CrossRef]

- Mizrahi, M.; Golan, A.; Mizrahi, A.B.; Gruber, R.; Lachnish, A.Z.; Zoran, A. Digital Gastronomy: Methods & Recipes for Hybrid Cooking. UIST 2016 - Proceedings of the 29th Annual Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology 2016, 541–552. [CrossRef]

- Min, W.; Jiang, S.; Liu, L.; Rui, Y.; Jain, R. A Survey on Food Computing. ACM Comput Surv 2020, 52. [CrossRef]

- Anumudu, C.K.; Augustine, J.A.; Uhegwu, C.C.; Uche, J.N.; Ugwoegbu, M.O.; Shodeko, O.R.; Onyeaka, H. Smart Kitchens of the Future: Technology’s Role in Food Safety, Hygiene, and Culinary Innovation. Standards 2025, 5, 21. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, D.P.; Ailawadi, P. Computational Gastronomy - Use of Computing Methods in Culinary Creativity. TRJ Tourism Research Journal 2019, 3, 203. [CrossRef]

- Razzaq, M.S.; Maqbool, F.; Ilyas, M.; Jabeen, H. EvoRecipes: A Generative Approach for Evolving Context-Aware Recipes. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 74148–74164. [CrossRef]

- Bossard, L.; Guillaumin, M.; Van Gool, L. Food-101 - Mining Discriminative Components with Random Forests. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics) 2014, 8694 LNCS, 446–461. [CrossRef]

- Myers, A.; Johnston, N.; Rathod, V.; Korattikara, A.; Gorban, A.; Silberman, N.; Guadarrama, S.; Papandreou, G.; Huang, J.; Murphy, K. Im2Calories: Towards an Automated Mobile Vision Food Diary. Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision 2015, 2015 Inter, 1233–1241. [CrossRef]

- de Araújo Gomes, A.; Azcarate, S.M.; Špánik, I.; Khvalbota, L.; Goicoechea, H.C. Pattern Recognition Techniques in Food Quality and Authenticity: A Guide on How to Process Multivariate Data in Food Analysis. TrAC - Trends in Analytical Chemistry 2023, 164. [CrossRef]

- Salvador, A.; Drozdzal, M.; Giro-I-Nieto, X.; Romero, A. Inverse Cooking: Recipe Generation from Food Images. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition; IEEE Computer Society: Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain, 2019; Vol. 2019-June, pp. 10445–10454.

- Jang, K.; Park, J.; Min, H.J. Developing a Cooking Robot System for Raw Food Processing Based on Instance Segmentation. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 106857–106866. [CrossRef]

- Qais, M.H.; Kewat, S.; Loo, K.H.; Lai, C.M. Early Outlier Detection in Three-Phase Induction Heating Systems Using Clustering Algorithms. Ain Shams Engineering Journal 2024, 15, 102467. [CrossRef]

- Ciocca, G.; Napoletano, P.; Schettini, R. CNN-Based Features for Retrieval and Classification of Food Images. Computer Vision and Image Understanding 2018, 176–177, 70–77. [CrossRef]

- Chotwanvirat, P.; Prachansuwan, A.; Sridonpai, P.; Kriengsinyos, W. Advancements in Using AI for Dietary Assessment Based on Food Images: Scoping Review. J Med Internet Res 2024, 26, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Manochandar, S. AI-Enhanced Smart Cooking Pot: A Culinary Companion with Intelligent Sensing. IETI Transactions on Data Analysis and Forecasting (iTDAF) 2024, 2, 41–55. [CrossRef]

- Bollini, M.; Tellex, S.; Thompson, T.; Roy, N.; Rus, D. Interpreting and Executing Recipes with a Cooking Robot. 2013, 481–495. [CrossRef]

- Lugo-Morin, D.R. Artificial Intelligence on Food Vulnerability: Future Implications within a Framework of Opportunities and Challenges. Societies 2024, 14. [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.; Kim, J.; Hare, V.M.; Agrawala, M. RecipeScape: Mining and Analyzing Diverse Processes in Cooking Recipes. Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems - Proceedings 2017, Part F1276, 1524–1531. [CrossRef]

- Min, W.; Hong, X.; Liu, Y.; Huang, M.; Jin, Y.; Zhou, P.; Xu, L.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, S.; Rui, Y. Multimodal Food Learning. ACM Transactions on Multimedia Computing, Communications and Applications 2025, 21. [CrossRef]

- Ciocca, G.; Napoletano, P.; Schettini, R. Food Recognition: A New Dataset, Experiments, and Results. IEEE J Biomed Health Inform 2017, 21, 588–598. [CrossRef]

- Watson, R.T. Beyond Being Systematic in Literature Reviews in IS. Journal of Information Technology 2015, 30, 185–187. [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B.A.; Budgen, D.; Pearl Brereton, O. Using Mapping Studies as the Basis for Further Research - A Participant-Observer Case Study. Inf Softw Technol 2011, 53, 638–651. [CrossRef]

- Ali, O.; Abdelbaki, W.; Shrestha, A.; Elbasi, E.; Alryalat, M.A.A.; Dwivedi, Y.K. A Systematic Literature Review of Artificial Intelligence in the Healthcare Sector: Benefits, Challenges, Methodologies, and Functionalities. Journal of Innovation and Knowledge 2023, 8, 100333. [CrossRef]

- Ali, O.; Ally, M.; Clutterbuck; Dwivedi, Y. The State of Play of Blockchain Technology in the Financial Services Sector: A Systematic Literature Review. Int J Inf Manage 2020, 54, 102199. [CrossRef]

- Ali, O.; Jaradat, A.; Kulakli, A.; Abuhalimeh, A. A Comparative Study: Blockchain Technology Utilization Benefits, Challenges and Functionalities. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 12730–12749. [CrossRef]

- Keele, S. Guidelines for Performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering. Technical report, Ver. 2.3 EBSE Technical Report. EBSE 2007.

- Systematic_Mapping_Studies_in_Software_Engineering Español Julio 2024 Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228350426_Systematic_Mapping_Studies_in_Software_Engineering (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Learning Structured Output Representation Using Deep Conditional Generative Models | Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems - Volume 2 Available online: https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555/2969442.2969628 (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Yuan, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhao, B. A Survey of Multimodal Learning: Methods, Applications, and Future. ACM Comput Surv 2025, 57. [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372. [CrossRef]

- Ouhaichi, H.; Spikol, D.; Vogel, B. Research Trends in Multimodal Learning Analytics: A Systematic Mapping Study. Computers and Education: Artificial Intelligence 2023, 4, 100136. [CrossRef]

- Paul, J.; Lim, W.M.; O’Cass, A.; Hao, A.W.; Bresciani, S. Scientific Procedures and Rationales for Systematic Literature Reviews (SPAR-4-SLR). Int J Consum Stud 2021, 45, O1–O16. [CrossRef]

- Golder, S.; Loke, Y.K.; Zorzela, L. Comparison of Search Strategies in Systematic Reviews of Adverse Effects to Other Systematic Reviews. Health Info Libr J 2014, 31, 92–105. [CrossRef]

- How to Write and Publish a Scientific Paper Seventh Edition.

- Jernudd, B.H. Genre Analysis: English in Academic and Research Settings. John M. Swales. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990. Pp. 288. 15.95 Paper. Stud Second Lang Acquis 1993, 15, 125–126. [CrossRef]

- Amarasinghe, C.; Ranasinghe, N. Digital Food Sensing and Ingredient Analysis Techniques to Facilitate Human-Food Interface Designs. ACM Comput Surv 2024, 57. [CrossRef]

- Shaikh, S.A.H. A Transformer-Based Convolutional Local Attention (ConvLoA) Method for Temporal Action Localization. International Journal of Machine Learning and Cybernetics 2024. [CrossRef]

- Miyatake, Y.; Punpongsanon, P. EateryTag: Investigating Unobtrusive Edible Tags Using Digital Food Fabrication. Front Nutr 2025, 12. [CrossRef]

- Fujii, T.; Sei, Y.; Tahara, Y.; Orihara, R.; Ohsuga, A. “Never Fry Carrots without Chopping” Generating Cooking Recipes from Cooking Videos Using Deep Learning Considering Previous Process. International Journal of Networked and Distributed Computing 2019, 7, 107. [CrossRef]

- Martin-Bautista, A.M.-G.G.-B.J. Adaptafood: An Intelligent System to Adapt Recipes to Specialised Diets and Healthy Lifestyles. Multimed Syst 2025. [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.P.K.K.S. FlavorGraph: A Large-Scale Food-Chemical Graph for Generating Food Representations and Recommending Food Pairings. Sci Rep 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ataguba, G.; Orji, R. Exploring Large Language Models for Personalized Recipe Generation and Weight-Loss Management. ACM Trans Comput Healthc 2025, 6. [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Yang, X.; Xu, C. Self-Supervised Calorie-Aware Heterogeneous Graph Networks for Food Recommendation. ACM Transactions on Multimedia Computing, Communications and Applications 2023, 19. [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Chung, F.L.; Jiang, W.; Ester, M.; Liu, W. A Deep Bayesian Tensor-Based System for Video Recommendation. ACM Trans Inf Syst 2019, 37. [CrossRef]

- Pakray, A.F.U.R.K.S.S.A.D.M. Multimodal Recipe Recommendation System Using Deep Learning and Rule-Based Approach. SN Comput Sci 2023. [CrossRef]

- Patel, Z.; Chokshi, H.J. Food Recommender System: Methods, Challenges, and Future Research Directions. International Journal of Engineering Trends and Technology 2025, 73, 267–276. [CrossRef]

- Veselkov, J.S.G.B.P.L.Z.M.V.B. Genomic-Driven Nutritional Interventions for Radiotherapy-Resistant Rectal Cancer Patient. Sci Rep 2023. [CrossRef]

- Silva, L.M.; Ankrah, E.A.; Huai, Y.; Epstein, D.A. Exploring Opportunities for Multimodality and Multiple Devices in Food Journaling. Proc ACM Hum Comput Interact 2023, 7, 1–27. [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Huang, L.; Ye, J.; Wang, J.; Lin, X.; Wu, S.; Hu, W.; Lin, Q.; Li, X. Enhancing Nutritional Management in Peritoneal Dialysis Patients through a Generative Pre-Trained Transformers-Based Recipe Generation Tool: A Pilot Study. Front Med (Lausanne) 2024, 11. [CrossRef]

- Kurnianingtyas, D.; Daud, N.; Arai, K.; Indriati; Marji Automated Menu Planning for Pregnancy Based on Nutrition and Budget Using Population-Based Optimization Method. IAES International Journal of Artificial Intelligence 2025, 14, 3483–3492. [CrossRef]

- Braga, B.C.; Arrieta, A.; Bannerman, B.; Doyle, F.; Folson, G.; Gangupantulu, R.; Hoang, N.T.; Huynh, P.N.; Koch, B.; McCloskey, P.; et al. Measuring Adherence, Acceptability and Likability of an Artificial-Intelligence-Based, Gamified Phone Application to Improve the Quality of Dietary Choices of Adolescents in Ghana and Vietnam: Protocol of a Randomized Controlled Pilot Test. Front Digit Health 2022, 4. [CrossRef]

- Starke, A.D.; Dierkes, J.; Lied, G.A.; Kasangu, G.A.B.; Trattner, C. Supporting Healthier Food Choices through AI-Tailored Advice: A Research Agenda. PEC Innovation 2025, 6, 100372. [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Hu, Y.; Lu, Q. Cooking Method Detection Based on Electronic Nose in Smart Kitchen. Jisuanji Fuzhu Sheji Yu Tuxingxue Xuebao/Journal of Computer-Aided Design and Computer Graphics 2023, 35, 185–194. [CrossRef]

- Cassi, M.B.B.-C.B.V.R.A.T. The Recipe Similarity Network: A New Algorithm to Extract Relevant Information from Cookbooks. Sci Rep 2025. [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Li, W.; Cui, X.; Wang, Z.; Berretti, S.; Wan, S. MS-GDA: Improving Heterogeneous Recipe Representation via Multinomial Sampling Graph Data Augmentation. ACM Transactions on Multimedia Computing, Communications and Applications 2024, 20. [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Verma, A.; Verma, P. IoT-HGDS: Internet of Things Integrated Machine Learning Based Hazardous Gases Detection System for Smart Kitchen. Internet of Things (The Netherlands) 2024, 28. [CrossRef]

- Burns, M.; Cruciani, F.; Morrow, P.; Nugent, C.; McClean, S. Using Convolutional Neural Networks with Multiple Thermal Sensors for Unobtrusive Pose Recognition. Sensors 2020, 20, 6932. [CrossRef]

- Kabala, K.; Dziurzanski, P.; Konrad, A. Development of a Reinforcement Learning-Based Adaptive Scheduling Algorithm for Commercial Smart Kitchens. Informatyka, Automatyka, Pomiary w Gospodarce i Ochronie Środowiska 2025, 15, 117–122. [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Magarino, I.; Muttukrishnan, R.; Lloret, J. Human-Centric AI for Trustworthy IoT Systems With Explainable Multilayer Perceptrons. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 125562–125574. [CrossRef]

- XIA, B.; Abidin, M.R.Z.; Ab Karim, S. From Tradition to Technology: A Comprehensive Review of Contemporary Food Design. Int J Gastron Food Sci 2024, 37. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Min, W.; Lyu, Y.; Liu, L. Few-Shot Food Recognition via Multi-View Representation Learning. ACM Transactions on Multimedia Computing, Communications and Applications 2020, 16. [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Sun, D.; He, Y. Emerging Techniques for Determining the Quality and Safety of Tea Products: A Review. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf 2020, 19, 2613–2638. [CrossRef]

- Ponte, D.; Aguilar, E.; Ribera, M.; Radeva, P. Multi-Task Visual Food Recognition by Integrating an Ontology Supported with LLM. J Vis Commun Image Represent 2025, 110, 104484. [CrossRef]

- Du, J.D.H.L.L. The Multi-Learning for Food Analyses in Computer Vision: A Survey. Multimed Tools Appl 2023. [CrossRef]

- Sakib, N.; Shahariar, G.M.; Kabir, M.M.; Hasan, M.K.; Mahmud, H. Towards Automated Recipe Genre Classification Using Semi-Supervised Learning. PLoS One 2025, 20. [CrossRef]

- Karabay, A.; Varol, H.A.; Chan, M.Y. Improved Food Image Recognition by Leveraging Deep Learning and Data-Driven Methods with an Application to Central Asian Food Scene. Sci Rep 2025, 15. [CrossRef]

- Varshney, R.K.Z.B.R.K.R. From Phytochemicals to Recipes: Health Indications and Culinary Uses of Herbs and Spices. NPJ Sci Food 2025. [CrossRef]

- Torres, J.P.; Caro, A.; Avila, M.D.M.; Perez-Palacios, T.; Antequera, T.; Rodriguez, P.G. A Computer-Aided Inspection System to Predict Quality Characteristics in Food Technology. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 71496–71507. [CrossRef]

- Piyasawetkul, T.; Tiyaworanant, S.; Srisongkram, T. AppHerb: Language Model for Recommending Traditional Thai Medicine. AI (Switzerland) 2025, 6, 170. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Lin, G.; Hoi, S.C.H.; Miao, C. Learning Structural Representations for Recipe Generation and Food Retrieval. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell 2022, 45, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Şener, E.; Ulu, E.K. Culinary Innovation: Will the Future of Chefs’ Creativity Be Shaped by AI Technologies? Tourism 2024, 72, 340–352. [CrossRef]

- Ławrynowicz, A. Creative AI: A New Avenue for the Semantic Web? Semant Web 2020, 11, 69–78. [CrossRef]

| AI applications reported in DG (a) |

AI methodologies and techniques (b) |

Data resources, standards and development frameworks (c) |

Challenges and emerging trends (d) |

|---|---|---|---|

| a1 - Food Recognition, Classification and CV a2 - Recipe Generation, Transformation and Creativity Support a3 - Recommender Systems for Food, Ingredients and Nutrition a4 - Nutrition Assessment, Dietary Monitoring and Health a5 - Cooking Assistance, Automation and Domestic Robotics a6 - Food Culture, Heritage and Culinary Knowledge Discovery a7 - Smart Kitchens, IoT, Retail and Food Service a8 - Cross-domain Applications and Miscellaneous |

b1 - CV b2 - NLP b3 - Graph-based Modelling b4 - Recommender Systems b5 - Multimodal DP b6 - Reinforcement Learning (RL) b7 - Traditional ML b8 - IoT, Sensors and Embedded Systems b9 - Robotics and Manipulation |

c1 - User-generated Data and Surveys c2 - Public Food Image Datasets c3 - Public Recipe and Multimodal Datasets c4 - Large-Scale Multimodal Web Data c5 - Chemical, Nutritional and Biomedical Databases c6 - Ontologies, Knowledge Graphs and Linked Data c7 - Standards, Guidelines and Annotation Protocols c8 - Software Frameworks and Infrastructure c9 - Development Frameworks and Experimental Pipelines |

d1 - Limitations in Data, Annotation and Benchmarking d2 - Multimodal, Sensorial and Cross-modal Integration Challenges d3 - Model Generalisation, Cultural Transfer and Cross-domain Robustness d4 - Evaluation, Validation and Real-world Deployment d5 - Interaction, Interfaces and Usability Issues d6 - Standards, Ethical, Privacy and Sustainability Constraints |

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Papers published between 2018 and 2025 Papers written in English Papers that address at least one of the research questions Publications that have undergone peer review and are either journal articles or conference papers |

Papers not written in English Duplicate studies Publications that have not been peer reviewed |

| Continent | Number of Countries | Number of Institutions | Countries Included * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asia | 9 | 47 | China (19), India (14), Japan (4), South Korea (3), Indonesia (1), Malaysia (1), Singapore (2), Thailand (1), Kazakhstan (1) |

| Europe | 8 | 29 | Spain (9), United Kingdom (4), Poland (5), Italy (2), Netherlands (1), Norway (3), Turkey (1), Ireland (1) |

| North America | 2 | 10 | United States (7), Canada (3) |

| South America | 1 | 1 | Brazil (1) |

| Africa | 0 | 0 | — |

| Oceania | 0 | 0 | — |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).