1. Introduction: Deconstructing Archetypal Binaries

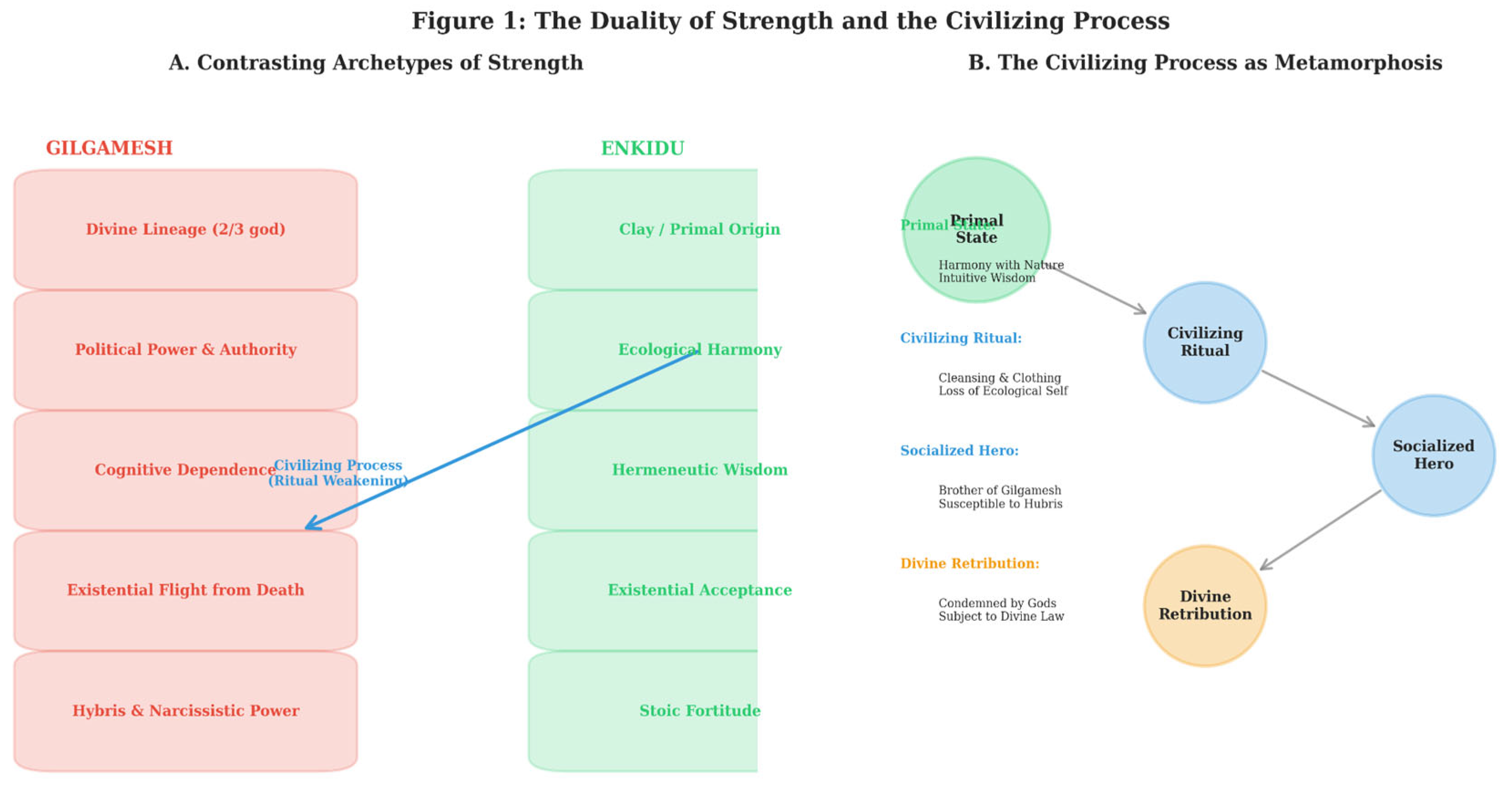

The Standard Babylonian Version of the Epic of Gilgamesh presents a foundational narrative whose psychological complexity has been overshadowed by simplistic archetypal readings. Gilgamesh is canonically viewed as the heroic, civilized king, while Enkidu serves as the wild, instrumental companion whose domestication and death facilitate the hero's growth (George, 2003). This paper proposes a paradigm-shifting reinterpretation: the epic systematically inverts this hierarchy, revealing Gilgamesh as existentially, cognitively, and emotionally weak, and Enkidu as possessing a foundational, integrated strength. This inversion is not a narrative flaw but the core mechanism for a profound exploration of strength, civilization, and mortality.

We redefine strength not as physical prowess or political power (Krakauer & Figueredo, 2013), but as existential integrity, emotional maturity, and the wisdom of acceptance—qualities linked to psychological resilience and adaptive coping (Routledge & Juhl, 2012; Pyszczynski, Greenberg, & Solomon, 2015). The epic’s central paradox is that Gilgamesh, two-thirds divine, is spiritually weaker than Enkidu, the creature of clay. This challenges the civilizational values the epic purportedly upholds, suggesting that the project of civilization may incur costs in psychic fragmentation and disconnection from natural law (Abram, 1996).

The Tripartite Weakness of Gilgamesh

Gilgamesh’s divine status masks a triad of profound weaknesses: moral, cognitive, and existential.

1.1. Moral Weakness: Hybris and the Empty Self

His early rule in Uruk is characterized by hybris—the ius primae noctis and oppressive labors. This represents not strength but a performative, narcissistic power rooted in insecurity and a need for validation, aligning with modern analyses of pathological narcissism and abusive authority (Twenge & Campbell, 2009; Krizan & Herlache, 2018). His actions betray a “purpose deficit” and an inability to form genuine attachments, fundamental for psychosocial health (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Pfund & Hill, 2018).

1.2. Cognitive Weakness: Hermeneutic Dependence

A critical flaw is Gilgamesh’s inability to interpret his own dreams (Tablets II, IV, V), forcing him to rely on his mother Ninsun and Enkidu. This signifies a catastrophic failure in metacognition—the ability to reflect on one’s own subconscious processes—a deficit linked to poorer psychological outcomes (Vaccaro & Fleming, 2018; Lysaker et al., 2018). He also consistently misreads external reality (e.g., interpreting ritual prostration as fear), demonstrating impaired social and religious cognition, often associated with narcissistic traits (Ritter et al., 2011). Enkidu acts as his necessary cognitive corrective.

1.3. Existential Weakness: The Collapse Before Mortality

His reaction to Enkidu’s death is a textbook case of complicated grief and existential crisis, manifesting as identity disruption, frantic flight, and magical thinking (Shear et al., 2011; Fong et al., 2016). His quest for immortality is not philosophical but a pathological denial of death, a manifestation of severe death anxiety (Iverach, Menzies, & Menzies, 2014). He lacks “existential maturity,” the ability to accept human finitude (Yalom, 1980).

Table 1.

The Tripartite Weakness of Gilgamesh.

Table 1.

The Tripartite Weakness of Gilgamesh.

| Domain |

Manifestation in Text |

Psychological Construct |

Key Reference |

| Moral (Hybris) |

Tyrannical rule in Uruk (ius primae noctis) |

Narcissistic Personality; Purpose Deficit |

Krizan & Herlache, 2018; Pfund & Hill, 2018 |

| Cognitive |

Inability to interpret dreams; misreading of social cues |

Metacognition Deficit; Impaired Theory of Mind |

Vaccaro & Fleming, 2018; Ritter et al., 2011 |

| Existential |

Catastrophic grief; denial-fueled quest for immortality |

Complicated Grief; Death Anxiety |

Shear et al., 2011; Iverach et al., 2014 |

2. The Composite Strength of Enkidu

Enkidu’s “wildness” signifies not savagery but an integrated state of being.

2.1. Ecological Strength: Harmony as Ethos

His initial state represents a coherent “ecological self”—identity and well-being contingent on harmony with nature (Kellert & Wilson, 1993). His strength is pro-social (freeing animals), contrasting with Gilgamesh’s predatory hybris. This connection to nature is linked to lower psychopathology and higher well-being (Howell et al., 2011).

2.2. Hermeneutic Strength: The Primary Decoder

Enkidu is the duo’s chief interpreter. He correctly decodes Gilgamesh’s dreams, providing a strategic roadmap—an ability associated with emotional intelligence and cognitive flexibility in deriving meaning from subconscious material (Hill et al., 2013; Edwards et al., 2013). He also understands the sacred nature of the Cedar Forest and Humbaba, voicing an ecotheological conscience (White, 1967).

2.3. Existential Strength: From Anguish to Acceptance

On his deathbed, Enkidu’s trajectory from cursing to blessing exemplifies integrative life review and ego development (Staudinger & Glück, 2011; Westerhof et al., 2004). His vision and narration of the Netherworld represent a courageous confrontation with mortality, in stark contrast to Gilgamesh’s flight. He embodies a Stoic acceptance, finding strength in acquiescing to cosmic order (Irvine, 2009).

Figure 1.

The Duality of Strength: Gilgamesh vs. Enkidu. A conceptual diagram would be inserted here showing two contrasting columns: Gilgamesh’s column listing "Divine Lineage," "Political Power," "Cognitive Dependence," "Existential Flight." Enkidu’s column listing "Clay/Primal Origin," "Ecological Harmony," "Hermeneutic Wisdom," "Existential Acceptance." An arrow from Enkidu’s "Ecological Harmony" points to a box labeled "Civilizing Process (Ritual Weakening)," which then points to a diminished version of Enkidu labeled "Socialized & Vulnerable.".

Figure 1.

The Duality of Strength: Gilgamesh vs. Enkidu. A conceptual diagram would be inserted here showing two contrasting columns: Gilgamesh’s column listing "Divine Lineage," "Political Power," "Cognitive Dependence," "Existential Flight." Enkidu’s column listing "Clay/Primal Origin," "Ecological Harmony," "Hermeneutic Wisdom," "Existential Acceptance." An arrow from Enkidu’s "Ecological Harmony" points to a box labeled "Civilizing Process (Ritual Weakening)," which then points to a diminished version of Enkidu labeled "Socialized & Vulnerable.".

3. Civilization as a Vector of Weakening

The bond between the two is tragically dialectic. Gilgamesh’s civilizing influence directly weakens Enkidu.

3.1. The Ritual of Weakening

Before facing Humbaba, Gilgamesh subjects Enkidu to a ritual cleansing, anointing, and clothing. This act symbolically severs Enkidu’s connection to his ecological self (George, 2003). Such forced disconnection from one’s environmental identity can induce psychosocial distress akin to ecological grief or solastalgia (Cunsolo & Ellis, 2018; Albrecht et al., 2007).

3.2. The Vulnerability of the Socialized

Once civilized, Enkidu becomes susceptible to peer influence and hubris. His desecration of Ishtar’s Bull and his ruthless urging to kill Humbaba reflect conformity to in-group norms and impulsive aggression under social pressure (Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004; Heatherton & Wagner, 2011). His newfound social agency makes him a visible target for divine retribution. Civilization grants social power but erodes metaphysical resilience.

Table 2.

The Civilizing Process as Metamorphosis and Weakening.

Table 2.

The Civilizing Process as Metamorphosis and Weakening.

| Stage |

Enkidu's State |

Source of Strength |

Vulnerability Introduced |

| 1. Primal State |

Ecological Self |

Harmony with Nature; Intuition |

None (in harmony with cosmic order) |

| 2. Civilizing Ritual |

Cleansed/Clothed/Armed |

Borrowed (Gilgamesh's mandate) |

Severance from ecological self; dependence |

| 3. Socialized Hero |

Brother of Gilgamesh |

Social belonging; Shared purpose |

Susceptibility to peer pressure & hubris |

| 4. Divine Retribution |

Condemned by gods |

N/A |

Subject to full weight of divine law |

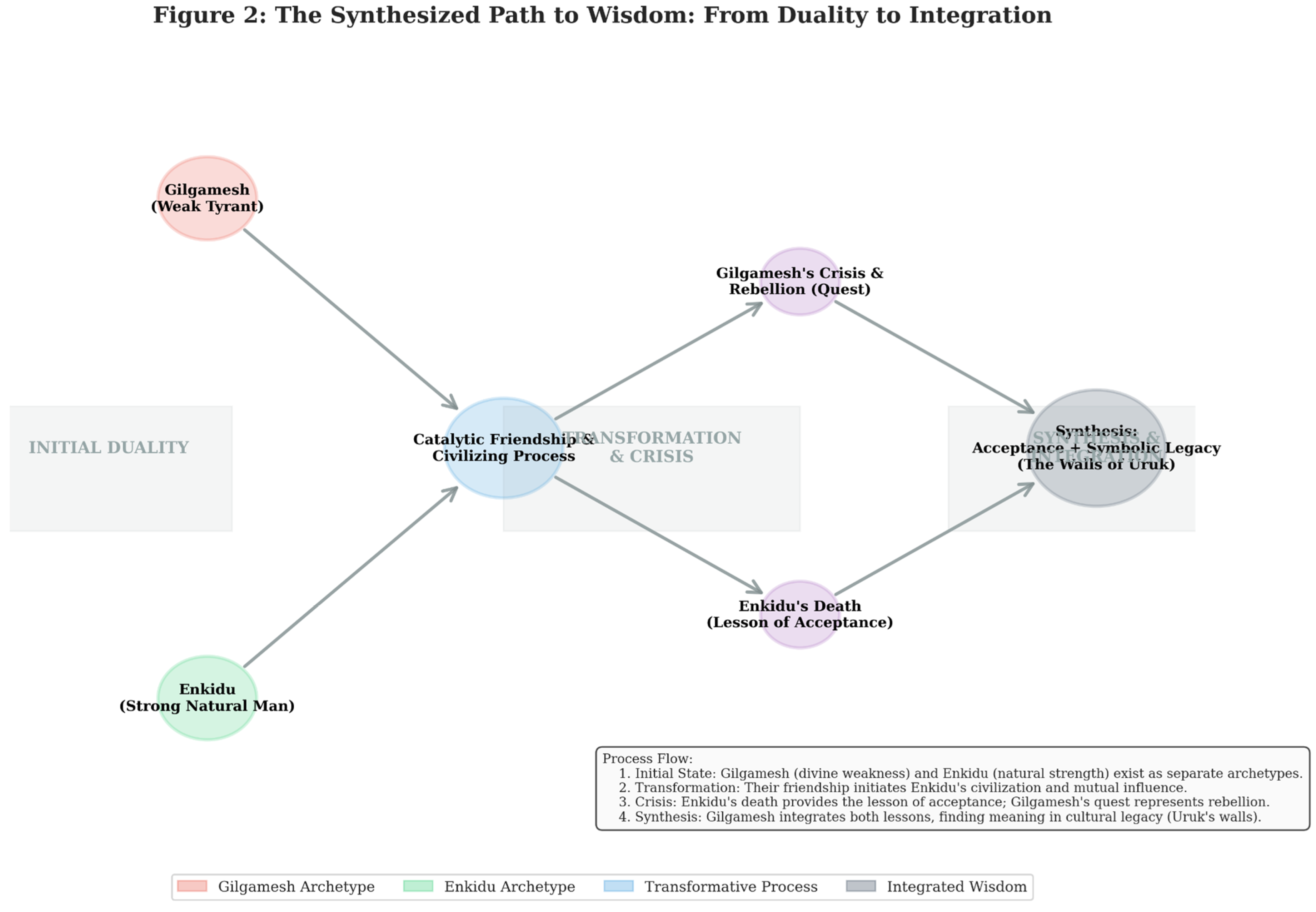

4. Synthesis: Two Types of Resistance and the Lesson of Strength

The epic concludes not with a victor but with a synthesis of two responses to mortality.

4.1. Enkidu’s Path: Stoic Acceptance

Enkidu models the strength of acceptance and integration. His deathbed process aligns with achieving ego integrity and managing death anxiety through worldview-consistent meaning (Erikson, 1959; Pyszczynski et al., 2015).

4.2. Gilgamesh’s Path: Existential Rebellion

Gilgamesh embodies rebellion and the quest for symbolic immortality. He rejects Siduri’s hedonistic advice (Seligman, 2011) and his pursuit of the Plant of Rejuvenation represents a Promethean, albeit failed, attempt to transcend biological limits.

4.3. The Final Synthesis: The Walls of Uruk

Gilgamesh’s return to Uruk and his celebration of its walls signify the integration of both lessons. He accepts personal finitude (Enkidu’s lesson) but channels his rebellious energy into his cultural legacy—the walls. This act of symbolic immortality striving represents post-traumatic growth, where loss is reconfigured into a new, meaningful philosophy (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004; Pyszczynski et al., 2015). True strength is thus achieved, not inherited.

Figure 2.

The Synthesized Path to Wisdom. A flowchart would be inserted here: 1. Start: "Gilgamesh (Weak Tyrant)" and "Enkidu (Strong Natural Man)" as separate nodes. 2. "Catalytic Friendship & Civilizing Process" connects them, leading to "Enkidu's Death (Lesson of Acceptance)." 3. This leads to "Gilgamesh's Crisis & Rebellion (Quest)." 4. Which leads to the final node: "Synthesis: Acceptance of Finitude + Investment in Symbolic Legacy (The Walls of Uruk).".

Figure 2.

The Synthesized Path to Wisdom. A flowchart would be inserted here: 1. Start: "Gilgamesh (Weak Tyrant)" and "Enkidu (Strong Natural Man)" as separate nodes. 2. "Catalytic Friendship & Civilizing Process" connects them, leading to "Enkidu's Death (Lesson of Acceptance)." 3. This leads to "Gilgamesh's Crisis & Rebellion (Quest)." 4. Which leads to the final node: "Synthesis: Acceptance of Finitude + Investment in Symbolic Legacy (The Walls of Uruk).".

5. Discussion and Implications

This analysis reframes the epic as a prescient exploration of psychological and ecological concepts. It deconstructs the heroic journey, showing that growth comes from integrating weakness, not exercising innate power (Campbell, 2008). The narrative offers a powerful ecocritical critique, illustrating how civilization’s ascent can entail a tragic alienation from the natural wisdom that constitutes a core aspect of human strength (Cunsolo & Ellis, 2018).

The epic’s enduring relevance lies in its sophisticated model of mortality management, presenting acceptance and creative rebellion not as opposites but as necessary components of a mature human response. Gilgamesh’s final wisdom is a blueprint for post-traumatic growth, demonstrating how meaning can be rebuilt after catastrophic loss through generative, cultural contribution.

6. Conclusion

The Epic of Gilgamesh systematically inverts the archetypes of the strong king and the wild man to argue that authentic strength is existential and earned, not inherited or natural. Gilgamesh’s weaknesses—his hybris, cognitive dependence, and death denial—are contrasted with Enkidu’s strengths—ecological integrity, hermeneutic wisdom, and stoic acceptance. The civilizing process itself is revealed as ambivalent, granting social power while eroding innate resilience. The ultimate lesson is synthesized at the walls of Uruk: human strength and immortality reside not in conquering death, but in the courageous acceptance of our limits and the enduring meaning we build within them. This ancient text thus provides a timeless framework for understanding resilience, growth, and the foundational quest for meaning in a finite world.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by the Author.

Consent for publication

The Authors transfer all copyright ownership, in the event the work is published. The undersigned author warrants that the article is original, does not infringe on any copyright or other proprietary right of any third part, is not under consideration by another journal and has not been previously published

Availability of data and materials

All data and materials generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript. The Authors had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Competing interests

The Author does not have any known or potential conflict of interest including any financial, personal or other relationships with other people or organizations within three years of beginning the submitted work that could inappropriately influence or be perceived to influence their work.

Authors' contributions

The Authors performed equally: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, statistical analysis, administrative, technical and material support, study supervision.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

The author used ChatGPT to assist with data analysis and manuscript drafting and to improve spelling, grammar and general editing. The authors take full responsibility of the content.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Cunsolo, A.; Ellis, N. R. Ecological grief as a mental health response to climate change-related loss. Nature Climate Change 2018, 8(4), 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, C. L.; Ruby, P. M.; Malinowski, J. E.; Bennett, P. D. Dreaming and insight. Frontiers in Psychology 2013, 4, 979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fong, T. C. T.; Ho, R. T. H.; Wan, A. H. Y. The role of emotional intelligence in the grief and depression of bereaved parents. Death Studies 2016, 40(5), 316–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A. R. The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition and Cuneiform Texts; Oxford University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Heatherton, T. F.; Wagner, D. D. Cognitive neuroscience of self-regulation failure. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2011, 15(3), 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, C. E.; Zack, J. S.; Wonnell, T. L.; Hoffman, M. A.; Rochlen, A. B.; Goldberg, J. L.; Exline, J. J. The effects of dream interpretation on session process and outcome. Dreaming 2013, 23(1), 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howell, A. J.; Dopko, R. L.; Passmore, H.-A.; Buro, K. Nature connectedness: Associations with well-being and mindfulness. Personality and Individual Differences 2011, 51(2), 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, W. B. A Guide to the Good Life: The Ancient Art of Stoic Joy; Oxford University Press, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Iverach, L.; Menzies, R. G.; Menzies, R. E. Death anxiety and its role in psychopathology: Reviewing the status of a transdiagnostic construct. Clinical Psychology Review 2014, 34(7), 580–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaba, T. Dasatinib and quercetin: short-term simultaneous administration yields senolytic effect in humans. Issues and Developments in Medicine and Medical Research 2022, Vol. 2, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Krakauer, L. D.; Figueredo, A. J. A quantitative ethnography of the Fijian tabua (sperm whale tooth) as a biocultural resource. Human Nature 2013, 24(2), 150–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizan, Z.; Herlache, A. D. The Narcissism Spectrum Model: A synthetic view of narcissistic personality. Personality and Social Psychology Review 2018, 22(1), 3–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lysaker, P. H.; Gagen, E.; Moritz, S.; Schweitzer, R. D. Metacognitive approaches to the treatment of psychosis: A comparison of four approaches. Psychology Research and Behavior Management 2018, 11, 341–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfund, G. N.; Hill, P. L. The multifaceted nature of sense of purpose. The Journal of Positive Psychology 2018, 13(4), 406–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyszczynski, T.; Greenberg, J.; Solomon, S. Thirty years of terror management theory: From genesis to revelation. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 2015, 52, 1–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, K.; Dziobek, I.; Preissler, S.; Rüter, A.; Vater, A.; Fydrich, T.; Roepke, S. Lack of empathy in patients with narcissistic personality disorder. Psychiatry Research 2011, 187(1-2), 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Routledge, C.; Juhl, J. The effect of mortality salience on implicit anti-war attitudes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 2012, 48(1), 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seisenberger, S.; Andrews, S.; Krueger, F.; Arand, J.; Walter, J.; Santos, F.; Reik, W. The dynamics of genome-wide DNA methylation reprogramming in mouse primordial germ cells. Molecular Cell 2012, 48(6), 849–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seligman, M. E. P. Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-being; Free Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shear, M. K.; Simon, N.; Wall, M.; Zisook, S.; Neimeyer, R.; Duan, N.; Keshaviah, A. Complicated grief and related bereavement issues for DSM-5. Depression and Anxiety 2011, 28(2), 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staudinger, U. M.; Glück, J. Psychological wisdom research: Commonalities and differences in a growing field. Annual Review of Psychology 2011, 62, 215–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedeschi, R. G.; Calhoun, L. G. Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry 2004, 15(1), 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkemaladze, J. Reduction, proliferation, and differentiation defects of stem cells over time: a consequence of selective accumulation of old centrioles in the stem cells? Molecular Biology Reports 2023, 50(3), 2751–2761. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36583780/. [CrossRef]

- Tkemaladze, J. Editorial: Molecular mechanism of ageing and therapeutic advances through targeting glycative and oxidative stress. Front Pharmacol 2024, 14, 1324446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tkemaladze, J. Through In Vitro Gametogenesis—Young Stem Cells. Longevity Horizon 2025, 1(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2009). The Narcissism Epidemic: Living in the Age of Entitlement. Free Press.Vaccaro, A. G., & Fleming, S. M. (2018). Thinking about thinking: A coordinate-based meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies of metacognitive judgements. Brain and Neuroscience Advances, 2, 1–14. [CrossRef]

- Westerhof, G. J.; Bohlmeijer, E. T.; Valenkamp, M. W. In search of meaning: A review of life review research in the context of geriatric care. Journal of Gerontological Nursing 2004, 30(3), 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).