2 Alex Ekwueme Federal University, Ndufu-Alike, Ikwo, Ebonyi State, Nigeria

Introduction

The Igbo as Africans share a common worldview that is heavily influenced by African traditional religion, locating and identifying the universe as a combination of the physically and meta-physically, the mundane and the supra-mundane, and the sensible and the supersensible. Indeed, it is a world of duality of existence and purpose. The Igbo cosmology, as a fallout of its religious background, is unambiguous in its conception of the interaction of beings, vital forces, and elements that make up existence (Metuh 1986: 78). In Igbo, daily engagements (as one of the numerous vital forces that people form the entire universe of connected relationships), he (African Igbo) strives to accumulate wealth, which for him is a combination of many elements, components, and ingredients, including death. This desire to acquire death or the expectation or preparation to meet death ultimately, so to say, occupies the life force, true essence and ultimate destination of every Igbo human life. It is therefore understood and interpreted from the prism and conviction of a religiously oriented meaning that they attach to wealth, death, and the essence of life generally. The rationale for seeking wealth is intrinsically located in their view of the interrelatedness and symbiosis of spiritual and physical worlds, enhancing and influencing each other. While the Igbo desire for ‘death’ is drawn from their conviction that wealth is not complete in the absence of inevitable death, the reality of the mystery of this uncommon alliance in African Igbo cosmology can be better understood, as it becomes clearer and more comprehensible in their ever-elaborate burial ceremonies and celebration of death with the accompanying rites and rituals to mark the transmission to another stage or phase of life and existence. However, this fascinating aspect of Igbo culture lacks an academic attention to expose and clarify some misconceptions. This gap has led to misrepresentations of this important traditional cosmology. To address this contending issue necessitated this study. The use of the word man in this work is to be understood as generic (representing all humans: man, woman, boy, girl) and not the specific man.

Research Questions and Objectives

In order to exhaustively discourse this Igbo religious, cultural and philosophical thought, this research asks and answers such questions as: What and how are the relationships that exist between death and wealth in the Igbo cosmology? Is death entirely a bad end in the Igbo worldview? How has the concept of good death impacted in the life and culture of the Igbo? The objective of this research is to establish the relationships and complementarity between good death and wealth in the Igbo religion, culture and thought. The work exposes the mystery of this African Igbo thought and the meaning attached to the conception of life, death and wealth. Secondly, it establishes that the African Igbo do not conceive of death (howbeit) as an end of life. Rather it marks an entry into another realm of existence. This has continued to manifest in Igbo thought not minding the great influence of missionary religions, urbanization, modernity and globalization as shown often through the modern printing of posters and invitation for funeral with such inscriptions as Transition into Glory, Triumphant Transition, and so on. An interviewee, Eze (2024) recounted that one of the major reasons an Igbo works hard is traceable to the complementary linkages between wealth and good death. Once an Igbo makes a good, noble and fulfilled life, his transition provides an avenue and opportunity to showcase further wealth through the funeral celebration (of life) and the multitude of sympathizers and mourners. Thirdly, the thought of wealth in good death impacts heavily on Igbo world-view. As Eze aforesaid argued, this conception has made an average Igbo to be very industrious to ensure that at their transition, a befitting funeral (with a prescribed rites and rituals) complements their nobility and achievements while alive.

The research findings establish that the phenomenon of death, though an evil of sort, remains a significant and celebrated part and parcel of the components of wealth as the African Igbo seeks to fulfil the essence of his creation or existence. The references have exposed the nature of the African Igbo person, their purposes on earth, origin and destination or eschatology. They have also unveiled the composition of the African/Igbo cosmology, the essence of life and what truly constitutes wealth, death and life, navigating all the essentials of life and existentialism. Death (especially the good one) does not terminate the African Igbo life, but remains only a means to another and higher spiritual life even to the benefit of those still alive. Death here becomes nothing but a rite of passage to an active spiritual life and a component of the desired complete and comprehensive wealth. This has been demonstrated with cases of the spirits of the dead allegedly appearing to their loved ones in dreams and trances either appreciating them for the qualities of funerals given to them, or rebuking them for not doing it rightly. Eze, 2024, Nwokorie, 2024, Mbadiegwu, 2024 and Eke, 2024 in separate interviews concurred to the foregoing. Ebisike (2024) added that in many cases, the bereaved family members are motivated to perform second burial (Okwukwu) to accord their departed ones a corresponding nobility, fulfilled and wealthy existence in the spirit realm/hereafter.

Theoretical Framework

This study hinges on the theory of hermeneutics, otherwise known as the theory of interpretation. The appropriateness of this research is understood from the fact that hermeneutics (interpretation) accommodates a broad range of areas of study. As the art of interpretation, hermeneutics, in general terms, have a rich history that refers to the theory and practice of interpretation involving an understanding that can be justified. It describes a body of historically diverse methodologies for interpreting texts, objects, and concepts that directly accommodate the focus of this research and the theory of understanding. As such, it concerns making it unintelligible, intelligible, and communicable (Dyer, 2010: 26).

In this regard, the concepts of wealth and death from the African Igbo worldview can be interpreted. This is done through the recognition of the African traditional religious background so much that the appreciation, meaning, and influence religion, wealth, and death exert on the African Igbo holistic life is well understood. As a preferred tool of interpretation in this research, Magee (2011: 37) observes that hermeneutics etymologically is derived from the Greek word to translate or interpret and similarly concerned with meaning in a very general sense. For Berk (2015: 45), this theory allows an understanding of human action within the context. Therefore, this theory is very suitable for this research.

Methodology

Considering that this study is a naturalistic one in the sense that variables were studied in real world settings without the researchers interfering or altering the variables studied, qualitative research approach was adopted to extract both primary and secondary data. Primary data were collected using oral (face-to-face and telephone) interviews, ethnography and participant observations. Ethnographic studies were carried out in such Igbo community as Uboma, Mbano, Ikwo, Okigwe, Nsukka, and Nnewi. These communities were spread to capture the five states of Igboland (Abia, Anambra, Ebonyi, Enugu, and Imo), Nigeria. In terms of participant observations, the researchers got involved in meetings, planning and funeral occasions in Igboland. Interviewees were selected using purposive sampling methods to locate Igbo traditionalists, elders, titled men, among others who have relevant information. Being a study that involves humans, beliefs and to some extent, emotions, the researchers announced the topic of research, purpose, objectives and expected results to the respondents and participants. Through this, their consents were secured before their participations. Secondary information used includes published academic works which were critically studied using content analysis for the purpose of this study. Generally, the data collected were analyzed using hermeneutic approach, while findings were chronologically presented in themes for easy understanding.

Locating the African Igbo

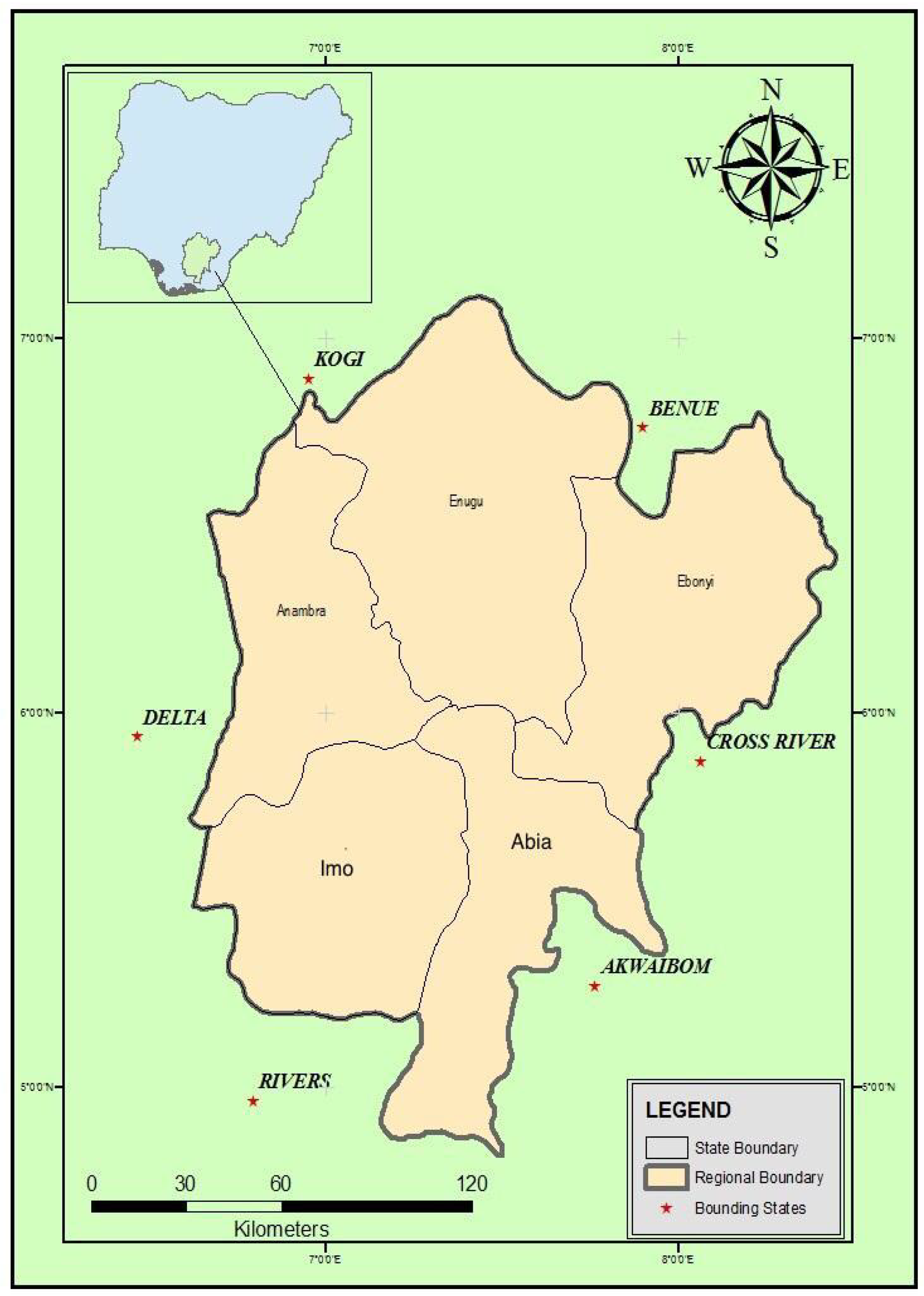

Okeke (2023: 3), x-rayed the views of AfIgbo (1981: x) that Igbo history is comparable to the hot soup, which is better eaten or licked from the sides of the container or plate as it were. This feature is a consequence of the complexities surrounding the tracing. Floyd (1969: 12) shares the view that it is very difficult to trace the history of Igbo or the origins of their nomenclature as both have been lost in a vicious circle of tradition. He maintained that migration to their present home in South-Eastern Nigeria from a distant land must have taken place many years ago. Since their domicile in the region, villages have obtained other villages to the extent that the tradition of the offshoots has become the original Igbo tradition of their origin. Few historians who are aware of this would yet undertake to write a comprehensive history of Igbo-speaking people. African Igbo is among the few African people who probably require little introduction into the outside world. Igboland is the indigenous homeland of the Igbo people. It is a cultural and common linguistic region in Southern Nigeria.

Geographically, the area is divided by the lower Niger River into two sections:

Eastern and Western regions (Slattery, 2016: 43). The people are primarily found in the Nigerian states of Abia, Anambra, Ebonyi, Enugu, and Imo. The area has an estimated population of 35 million, eight hundred and eleven thousand (35,811,000) people (Ibile, 2022: 98). The people are called Igbo, and their language is Igbo with significant and observable variations in dialect, with a central dialect spoken around areas mostly within parts of the Imo, Abia, and Anambra States.

A map of Nigeria showing Igboland, (Onyemechalu, 2020).

A map of Nigeria showing Igboland, (Onyemechalu, 2020).

The Igbo Human Being/Person

Like other human tribes, Igbo has always had the quest to unravel who the human being is, beginning with his origin or the origin of man. Going by the numerous myths of creation that abound in Igbos cosmology, human beings are always placed at the center of the universe. Igbo sees the universe from that perspective and considers the universe and everything in terms of its usefulness or otherwise to humans. For this reason, according to Onyeocha (1997:25), things in the universe are seen in terms of their purpose as human beings. The ones they could eat or not eat, the ones that helped or harmed. Those that serve or threaten.

This conception of the human person or being by the African Igbo tallies with Mbiti’s (1969: 35) view of African ontology as highly anthropocentric, revolving around the human being. Mbiti further posits that it is an extremely anthropocentric ontology in the sense that everything is seen in terms of its relation to man (and deducing from the five categories). God is the originator and sustainer of man; the spirits explain the destiny of man; man is at the center of this ontological hierarchy. Animals, plants, natural phenomena, and objects constitute the environment in which humans live, provide a means of existence, and if need be, man establishes a mystical relationship with them.

In the conception of the Igbo, man is born into this world first through his or her parents and into his or her community of many ancestors, some of whom are said to have reincarnated in him or her. He or she then grows into the linage unit in the village, town, country, and world communities (Onyeocha, 2007: 32). The Igbo human person is, by nature, not simply a social being in the gregarious Aristotelian sense, but is emphatically communalistic. We shall later see how this communality factor adds to the fulfilment of his destiny on Earth. He is not an individualistic human, as found in the industrialized West. However, the individual Igbo human being has no personality and no rule unless as a community person, like a part of an engine, his prosperity being the prosperity of his kinsmen, near and distant, and of his society (Onyeocha, 2007: 17).

Though the human person is the prime of creation in going by the Igbo worldview, the human is placed at the center of the universe (Anyacho, 2016: 78), the sky is above him, and the underworld is beneath the earth where he lives. The activities that go on in the sky and those determined by powers in the sky affect the man. Thus, the Igbo human person depends on God for rain, which will wet his ground and the sun to help crop production. Man also depends on the deities and functionaries on the earth for the guidance of his actions, for help in getting the best of his sustenance and needs from the earth. He has many divinities that occupy significant positions in every aspect of his life, like ‘Ikenga’ deity, the Ala deity etc. Humans need them for crop production, medicine, fertility, protection, and good luck. He further needs the services of the spiritual forces in the great beyond for their favor because that is where man would transcend to in the fulfilment of his existence.

It is observable from the foregoing that the scientific view of man or the human being contrasts sharply with the Igbo concept in two major ways the essence of this distinction at this moment is to draw the attention for a more coherent understanding and appreciation of the Igbo mans inclusion and recognition of death phenomenon as a solid component of wealth. In Igbos conception of human beings, he is partly material and partly immaterial. That is, human beings are both biological and spiritual beings, in the concept of the Igbo world view. Human beings are an organic whole (Quarcoopome, 1987: 51). This rules out the idea of split personality. His physical part relates him to the family, lineage, clan, and tribe; hence, the idea and practice of the extended family system in the Igbo marriage setting. Therefore, it becomes obligatory for men to adhere to the rules of society for cohesion and solidarity. Spiritually, the human person depends on God and other spiritual entities for his life force, his essential being (wealth), or personality soul, in addition to his destiny. Good destiny is promoted by a good character, always calling out the soul to be conscious of moral and ethical demands.

Adding his voice to the concept of the human being in Igbo worldview, Anyanwu (1999: 71) posits that the human being is as mysterious as the earth in which he lives. Drawing from numerous Igbo myths of creation, he observes that the human being is created by ‘Chineke’ (Creator God), but exactly when he came into being is unknown. The human being’s psych is open to ‘Chukwu’ (Great God), the divinities and spirits, and the vital forces on the earth. One major characteristic of the African Igbo is that he is capable of entering into a relationship with supernatural forces and is also vulnerable to the influence of supernatural forces, either for good or for bad. Human beings, therefore, try to use the universe or derive some good (wealth) from it in physical, mystical, and supernatural ways. In reality, the Igbo does not conceive of the human being as the master of the universe; he is only at the center.

According to Nwala (1985: 31), human beings are not only regarded as the most important aspect of creation, they are also regarded as being superior in natural intelligence to other beings. The Igbo person is typically threatened by famine, disease, and war, some of which fall into the capricious potency of forces that must be channelled correctly. What happened to Achan in the Bible is a good illustration of the sense of solidarity of the Igbo human being and his existence. The whole community suffered as a consequence of Achans sin until Achan and his family were executed. Thus, for the well-being of African Igbo and his society, he must regulate his conduct and what he does to uphold the well-being of society (Onwubuariri, 2011: 17).

The Philosophy of ‘Onwudinuba’

This philosophy is derived from the compound word Onwudinuba (death is part of wealth or death is a component of wealth). It comprises of Onwu (death), Dina (part of or component of) and Uba (wealth). Put together, one will have Onwudinuda (death is a component of wealth). It is an acceptable fact among scholars of various fields and across the divide that wealth is a combination of various elements or ingredients. Generally, wealth is the abundance of valuable financial assets or physical possessions that can be converted into a form that can be used for transactions. This includes the core meaning held in the originating Old English World Weal, which is from an Indo-European word stem (American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language 4TH ed). The United Nations defines inclusive wealth as a monetary measure that includes the sum of natural, human, and physical assets (The Economist, June 30th, 2012; Inclusive Wealth Report, July 9, 2012).

The concept of wealth among the Igbo includes stocks of goods such as buildings, parcels of land, houses, furniture, cars, clothes, and many children or large families. It also includes intangible assets, such as good health, which are counted, praised, and imagined sources and instruments of power (Guyer 1995: 45). Death was added to the aforementioned component. This is derived from the names Igbo bears or gives them to their children. One of such name is Onwudinuba. Through this, the Igbo understands wealth as death that also brings to the person who has acquired wealth or looks forward to acquiring wealth. The phenomenon of death, as may be generally understood from its known effects, is that it brings sadness, sorrow, grief, and pain as a loved one or breadwinner die.

Yet, in this understandable negative feeling, Igbo still recognizes and appreciates that this unpleasant phenomenon is part of the wealth most humans desire. The importance of this philosophy in the Igbo will be better understood and interpreted if one considers the value they place on wealth. According to Mensah and Iloh (2021), wealth is highly regarded in Igbo culture and its acquisition is a status symbol. This ensures the material welfare of those privileged to control it. Thus, Igbo acquires wealth as a source of power to guarantee pleasurable and healthy lifestyles that they desire. Death becomes an ingredient or element that he desires through his express desire and overt pursuit of wealth. Igbo searches for wealth. In this search, he also searches for death, which is part of wealth and without which wealth will not be complete. We shall see that it plays out in the subsequent subheadings.

Wealth in Igbo Cosmology

The Igbo word for wealth is Uba. Some scholars such as Mensah and Iloh (2021: 22) wrongly identified wealth as Aku in the Igbo language. The Igbo word Aku stands for riches, which are no doubt part of wealth (Uba). However, it does not fully or completely represent the meaning of wealth in Igbos cosmology. Aku or riches represent those items or elements which the human being has a greater percentage to acquire by the instrumentality of his hard-work, industry and labor. Such elements or items include financial or monetary acquisitions, property of land, nobility, and fame. However, from the Igbo name Madukaku (human is greater than property). It is understandable that the human life which is part of the components of wealth is not captured in the use of Aku as representing wealth in Igbo cosmology. Hence, the proper word for wealth in Igbo cosmology is Uba which acceptably represents a combination of non- human property like money, buildings or houses, the human element of wealth (large families and children) and the death element. In accordance with this view and meaning, the Igbo have or bear such names as Ubaku (wealth of property), Ubasinachi (wealth comes from God), Ubamadu (wealth of human beings) and Madukaku (humans are greater than property or money).

The Igbo has a clear understanding of the eternal mysticism of the essence of human life, which acknowledges and further identifies some elements of wealth creation, the ability, or power to make wealth that comes from the spiritual or super-sensible world. It is for the human being or person to struggle to acquire money, property, fame, and nobility. It is another reality that all his struggles would amount to nothingness if his chi (guardian angel or spirit) refuses or fails to support his efforts. The Igbo represents this understanding in their pithy saying - Omemara ma chi ekweghi, onye uta atala ya (nobody should blame anyone whose God has not granted or permitted success). From the Igbo name Ubasinachi (wealth comes from God), it is clear that for the Igbo, acquiring wealth is only feasible by the combined efforts that come from the super-sensible world to grant one success. It should be pointed out that although Igbo believes that wealth has a spiritual element, it still resides with human beings to make an appreciable effort to be wealthy. The one who desires wealth must not be slothful, lazy, or procrastinate in any form, material, or particular. If one desires to be wealthy, they must be hard-working, industrious, diligent, and focused. This accounts for the reason behind the Igbo deity, which represents industry, commerce, and hard work known as Ikenga.

According to Nwaorgu (2001: 65), ‘Ikenga’ refers to the Igbo mans right arm of valor. In form, it is symbolized variously in carved images, which is illustrated in a great achievement or in an exemplary performance at which the Igbo man raises his right arm up and exclaims in great jubilation, ‘Aka-Ikenga mu!’ (Oh, my right hand of the valor). ‘Ikenga’ as a deity also confirms the Igbo cosmology that Ihe di abuo (things are double), physical and spiritual. For Anilakor (1984: 38) man in Igbo cosmos in pursuit of Igbo ideals of status, success and achievement is well certified by the cult of his right hand and good of fortune known as Ikenga, his male vitality, his life force and individuality. Ikenga represents the Igbo god of personal strength and achievement, to which Igbo traditionally minded forebearers attributed their success in various realms of endeavor. It is artistically presented as two-horned carving.

Enekwe (1987: 60) interprets Ikenga image thus, ‘the two ram horns mean that the person must go ahead into his business with the stubbornness of a ram. The knife in his right hand means that he must cut down any obstacle on the way, and the skull in the left hand means that he must always take the lead to succeed. Nwala (1985: 53) described Ikenga as a symbol of the cult of the right achievements. The art object showing Ikenga realistically brings forth the strong right and force that directs achievement. The art object showing Ikenga realistically brings forth the strong right-hand with which the individual (with a knife in his hand) hacks his way through and pursues his goal is reflected in the stubborn ram that he holds. The skull (Isi) in his hand, which an individual must take daringly to succeed.

The Igbo acquires money and property, and by his desire to have a large family, he marries many wives who bear him many children, making him have the human element or part of wealth (Ubamadu). Monetary or property wealth leads Igbo to acquire wealth. It is with money that he buys all the items required to settle the bride prize and other demands in line with customary marriage. It is also with his monetary wealth that he feeds on his large family, sends the children to school, and establishes them in various skills acquisition or trade. He is a happy man who has children (both males and females) and has the capacity to feed and train them.

The concept or phenomenon of death is activated when the Igbo transitions to the spiritual world after a ripe old age. This transition brings his family members, in-laws, friends, colleagues, and association to accord him with the last respect during his burial. His compound is filled with people from all walks of life: They eat, dance, and celebrate their lifetime. Gifts are brought to the house in the form of goats, chickens, cows, sheep, assorted drinks, and money. The elements or components of wealth manifest during this burial. His survivors also became rich in gifts they received from their guests, associates, friends, and sympathizers. Here lies the death element or component of wealth in Igbos cosmology.

Death as a Component of Wealth in Igbo World-View

Death is a common phenomenon and destination for every living thing. There is a time or season when living is brought into existence and another season or time when it goes into extinction. Upon extinction (or non-existence), human beings are said to have died. The Collins Dictionary defines death as the permanent end of life of a person or animal (

www.collinsdictionary.com). It is the act of passing away, the end of life, or the permanent destruction of something. Pallis (1983: 16) stated that death is the total cessation of life processes that eventually occur in all living organisms. The state of human death has always been obscured by mystery and superstition, and its precise differs according to culture and the legal system. For Pallis, during the latter half of the 20th century, death became a popular subject. Before that time, perhaps rather surprisingly, it was a theme largely eschewed in serious scientific and, to a lesser extent, philosophical speculations. However, in modern times, the study of death has become a central concern in most disciplines.

However, for an African Igbo, death is just a transition, journey, stage, and initiation process from a physically active living to an active spiritual living. When the human Igbo is living in the physical, his nature of existence is physical-spiritual. When he dies, he takes the form of a spiritualphysical life. According to Mbiti (1969: 50), death for an African is not a complete annihilation of a persons departure from one state of life to another or a portal to a wider world. Death in Igbo cosmology is only a transition; it is not the opposite of life, but part of the true existence that must be when it will. Death does not contradict existence, but complements it by its position as a replica of life. Therefore, death is a transition or passage to another form of living or existence. While Igbo is alive, he is an active human participant and a passive spiritual entity. However, when he passes through the transformation of death, the dead become an active spiritual and passive human entity. When death is not called, the Igbo human sees himself as a human-spiritual entity. However, when death comes, it becomes a human spiritual entity. This is why in Igbo cosmology, ones relatives include, therefore, the living, dead, and unborn.

The dead are said to be interested in the affairs of the living through whose efforts (in libation, rites, and rituals) are capable of re-entering the physical world inform of reincarnation. Igbo recognizes two categories or types of death. The first is that they call bad death.” This is a premature death. The death of one who did not attend ripe old age. The death of a person by means such as accident, lightening, swollen stomach, drowning in a river, falling from a tree, or dying of leprosy. When a youth dies, especially unmarried ones, it represents bad death in its fullest meaning. As a bad death, it is an interpretation of the vengeance or anger of the gods or evil from the spirit world, which may have been allowed by the gods due to the evil deeds of the person or relatives as it were. This interpretation is a confirmation of the sins of the parents being visited by their children. Hence, all is called upon to quickly do the needful of appeasing the gods each time they are offended through scarification, libation, and similar rites.

This category or classification of death in Igbo cosmology is known as ‘Onwu mgbabi chi’ (premature death) and does not constitute one of the components or elements of wealth in Igbo philosophy. Conversely, such death, which is said to be bad, is well captured in some of the names Igbo gives to their children. They include Onwu churuba (death drives away wealth), Onwuemenyi (death has no friend), Onwubuariri (death is an impediment), Onwubiko (death I plead with you), Ntishirionwu (death does not hear) and many more. Because this type of death is tragic, premature, and abruptly cuts life short, it does not qualify as a transition to a world of peaceful spirit. One who dies through this means cannot be an ancestor; it cannot be ushered into the ancestral world with elaborate rites and rituals, and cannot receive libation and newer to be invoked for the good of the land. Therefore, it does not qualify to be included as a part of wealth in the Igbo worldview. In line with this interpretation, Awolalu and Dopama (1979) state that a bad death does not normally receive full funeral rites. When a child dies, parents and relatives lament to death. Deaths caused by the anti-wickedness divinities like ‘amadioha’ (the god of thunder), small pox and iron are regarded as bad. They may be capital punishments for the divine and must not be mourned. The deceased are buried in purificatory and expiatory rituals to appeal to the divinities concerned. All those who die of a bad death are not given formal burials, but they are buried without delay by a specialist (priest) and not within the homestead, but far away from home in the evil forest. They are kept at a distance to wonder as ghosts by sacrificing exorcism. Thus, they are never remembered as they are quickly forgotten in antiquity.

The death that the Igbo interprets as part of or a component of wealth that must be pursued is good death. Good death is the opposite of bad. In Igbo cosmology or world-view it is called Onwuchi (natural death). This death is not only benevolent, but also comes after a ripe old age. It is the desired death of those who lived a transparent, fruitful, honest, and morally upright life, with offspring, and accorded a befitting or elaborate burial ceremony with accompanying rites and rituals. The underlying reason for this belief is not farfetched; in the Igbo collective interpretation, ideas and spirituality must conform to what the Igbo society cherishes and respect as true and beneficial to the entire Igbo population and for the advancement of their well-being. Enekwe (1987: 72) agrees with this fact when he says that even though Igbo individuals are highly developed, it must not negate the Igbo concept of communal humanism that is found in most African people. The Igbo lives as a group, sees things as a group, and performs things as a group. Their lifestyles would never tolerate individual ventures.

When a good death occurs, deceased family members, relatives, and society are jointly involved. The first announcement of death is made in traditional Igbo society by the beating or sounding of the gong (ekwe). The wise men and women could clearly interpret the sound language of the gong. As the gong conveys the message, calling the names of some titled and powerful men of the village, community, and beyond, canon shots accompany the gong boom at intervals, showing that an important personality has transitioned. As the canon continued to shatter the silence of early morning, especially if it involved a titled man, men, women, and children, it would continue to wait breathlessly and would start to assemble in groups in the village or community, inquiring who may have transited. Since Igbo believes in reincarnation, during the burial ceremony, the man who had passed through the rites (the dead) was praised and a fresh mandate given to him to reincarnate as a strong and wealthy man in his next life. His wife shaved their hair. The funeral ceremony was an exciting event. Friends, in-laws, children, grandchildren, great-grandchildren, fellow titled men, and age grades of different groups would be involved in the burial. Items such as cows, goats, sheep, chicken, food items, and drinks (palm wine and spirits) would be abundant. On the day of burial, different groups would pay tributes befitting the deceased. Achebe (1981:76) captures this, pointing out that ancient drums of death beats, guns, and cannons were fired, and men dashed about in frenzy, cutting down every tree or animal they saw jumping over walls and dancing on the roof.

Depending on the community of the deceased, different age grades of the children and grand-children or his wives, different dancing groups according to where he belonged or where his children and wives belonged like Ndi-Okpanga, ndi-ma-ogu, Otu-ogbo, ndi-egberu-oba, in turn would demonstrate their art in the mans compound on the day of the burial. Entertainment was provided in the groups. Relatives of the departed would also visit in turns with presents such as cows, goats, cloth, Ukpaji (basket of yam) ukpa ede (basket of coco yam), cocks, etc. The Umu okpu (kinswomen) would keep the tempo of the burial celebration very high every night with their songs and dances. The burial ceremony consisted of two phases: the first came after burying the corpse, and the second came up after Izu asaa (seven market weeks). If the departed was a titled man, the items used during market days would be carried along with other valuable things to the market (Afuekwe, 1992). His children picked one item each for market dance. After market outing, it was believed that the deceased would have joined his settled ancestors and become Ndi-iche (ancestor). Drinks and kola nuts can then be given to them by those still living physically.

It is no doubt that from the foregoing, the good death in Igbo world-view brings out and confirms the availability of gift items in great quantities, including money, goats, chickens, cows, and other food items. Such death also gathers the entire society together to celebrate departure. People, friends, well-wishers, loved ones, children, kinsmen, and women of different groups, different dancers, and many activities that make up the rites of passage take place during the burial. All these activitiesmen, gifts, visitations, market outings, and libationconstitute an element or component of wealth in the philosophy and worldview of the Igbo. These activities are captured in one of the pithy statements of the Igbo girigiri wu ugwu eze (the multitude is a sign of kingship/wealth). It is therefore inconceivable that a man of Igbo extraction will have money, many children (large family), die, and be buried quietly without the accompanying elaborate rites and rituals to usher him into the spirit world. If this third element or component of wealth is lacking, the deceased is never a wealthy man in Igbo cosmology. No wealthy Igbo man dies without attracting people from all walks of life and gifts to his compound during his burial.

A table showing the two types of deaths in Igbo cosmology, Igbo names denoting them, and their meanings.

A table showing the two types of deaths in Igbo cosmology, Igbo names denoting them, and their meanings.

| Type of death and English meaning |

Igbo Names with death attached to their meanings |

English Meanings |

| Onwu mgbabi chi (premature death) |

Onwu churuba |

Death drives away wealth |

| Onwuemenyi |

Death has no friend |

| Onwubuariri |

Death is an impediment |

| Onwubiko |

Death I plead with you |

| Ntishirionwu |

Death does not hear |

| Onwuchi (natural death) |

Onwudinuba |

death is a component of wealth |

| Onwusinachi |

Death is from god |

| Onwuka |

Death is great |

| Onwubuike |

Death is strength |

| Onwubudo |

Death is peace |

Since Igbo, like his other African counterparts, conceive of a universe that has cyclical continuity, there is a sequence of one event after the other (in an ordered succession), symbolically expressing harmony, persistence, and dynamism (Onunwa, 1990), The good death and accompanying elaborate burial ceremony depicting wealth is life-affirming or world-affirming. One of the desires of every Igbo man at death is to reach the spirit world and enjoy fellowship with their ancestors. A dead man cannot get to the ancestral world to occupy his position if he is not wealthy (of finance, property, survivors, or elaborate burial). All these put together constitute an existential life span which form the cycle of life of return to the human-world through the process of reincarnation.

The researchers observed the burial ceremony of an Igbo man who fit into the interpretation of a wealthy man in one of the communities visited in the course of gathering the data for this work. The burial ceremony took place in a primary school field on Saturdays. While the dancing, eating, and presentation of gifts were going on, a mad man sat on the pavement of one of the blocks of the school building and observed all that was going on. He would walk up to the organizers to collect the burial brochure; he would walk up to those serving food to collect his share; he would walk up to those sharing drink and water to collect his share; and he would be pouring the different types of food into different waterproof bags he gathered from the environment. When it was time to leave, the mad man nicknamed Gi pose wee (continue to pose), apparently because of the way he used to walk raising his two shoulders, collected all his waterproof bags, and was heading home. Along the road, very close to where the researchers were discussing with one of the children of the deceased, some youth (three boys) called out the mad man saying Gi pose wee your bags are full of food and drinks. The mad man responded ‘ezi-okwu Onwudinuba’ (truly there is wealth in death).

The Rationale for Igbo to Seek Wealth

Wealth is to be understood in the context of its three components or elements of properties, human beings, and death as conceived in the Igbo worldview, and not just property or monetary value. A critical look at or appreciation of the elements is important for a proper understanding of why Igbo seeks wealth. In relation to money and property as elements of wealth, Igbo supports this desire, because it encourages one not to be lazy or slothful. One of Igbo idiomatic expressions directs that dimkpa ga agba mbo na-okorobia (a human being should struggle or work hard in his youth). This is a direct interpretation that the people understudy abhor laziness and slothfulness in all their ramifications or shades of manifestations. That is why Igbo begins early to tutor a child on how to be hardworking by taking him to the farm, making him learn a craft or trade depending on what is obtainable within the cultural area. Traditionally, Igbo youth were quick to learn blacksmithing, farming especially yam, cutting palm fruits, tapping palm wine, making baskets from bamboo, or even fishing for those living around riverine areas. Igbo believes that there is dignity in labor; he works hard to maintain his dignity and nobility.

Achebe (1959: 71) portrays Unoka’s okonkwo the father, as a derisive scorn of the community for being lazy, poor, and disappointing in life. He is not a courageous man. In fact was coward and could not bear sight of blood. As a result of disappointing the life of his father (Unoka), who could barely fend for his small family, Okonkwo, his son, was patently ashamed of his father and wanted to be an entirely man. In order to live a life different from that of his father, Okonkwo worked hard to be rich, had many wives, and became prominent. The philosophy of the Igbo about life no doubt further encouraged the people to embrace the development of entrepreneurial skill, Igba boi (apprenticeship) system which has become a major procedure in Igbo society. Today the ‘Igba boi’ system is an organized procedure recognized as a legitimate educational method for entrepreneurial development (Nwanegbo - Ben OzoIgbo, 2021: 17).

It is also against Igbos morality of being lazy. Amaegwu (2013) posits that laziness amongst other socially disapproved habits is generally condemned in Igbo society, the understanding that a humans moral life is paramount in maintaining the cosmic equilibrium. Therefore, the moral heroes of the Igbo world were selected from the animal world to reflect this. According to Nwoye (2011: 66), this includes a tortoise that is admired for its capacity to deploy creative ingenuity in the direction of finding solutions to the problem of living. Thus, Igbo seeks wealth to find solutions to the problems of living for himself, his family, his neighborhood, extended families, and society at large. He could not do this comfortably without acquiring wealth. In Igbo cosmology, wealth is a repellent of attackers of any form or magnitude, such as sickness, hunger, safety, group relations, or socialization. The tortoise as a moral totem in this regard is also believed to know when to open and close its amour, in keeping with the sensations of safety or danger. It is believed that among the Igbo, tortoises exude an odor that repels potential attackers.

In search of or gathering this wealth, Igbo is never in a hurry, like the proverbial tortoise. The Igbo moved slowly in pursuit of wealth. He is never in a hurry to get rich overnight or to acquire wealth overnight, for such is a fast lane to premature bad feat (Onwumgbabichi), which will cause him to be permanently poor while fulfilling his life essence, as he cannot reincarnate nor peacefully join the ancestral world. For Igbo, these qualities (as a path of wealth) reflect an imaginative deployment of intelligence for personal and communal safety and well-being. The human component of Igbo wealth draws value from death or the hereafter. Igbo longs to become an ancestor. He wanted to continue keeping the name of the family and going linage. The family must not become extinct. Procreation must continue so that there would always be members to perform libation for the comfort of ancestors, and for the ancestors to have survivors who are in solidarity with other spiritual entities ought to protect. A cycle or circle must not be cut. To be able to do this, a male child or a child is of great necessity. If the first wife is not able to bear male children or any children at all, she must not be driven away. She is not the cause or architect of her misfortune. It was not her makings. She remains the first wife, while the husband goes to bring another wife home after the completion of all marriage rites. The second wife may begin with one or two male children. The man may be happy but not yet comfortable, as he would be seen as a proverbial man with one eye and who could become blind if anything happens to the eye. Armed with the strength of finance and property, he goes for another wife and another and more. Since the world of the Igbo is masculine, the man abhors dying childless, in line with the Jewish tradition. African Igbo will do anything to beget male children.

When God called Abraham to go to a country he would show him, Abram and Sarai had no children, and the answer for a son Isaac came later, which made both Abraham and his wife Sarah happy (Gen. 18:9-15; 21:1-7). As with Jews, it is with Igbo. Children are the backbone and strong-hood of the family (Psalm 127:3-6; 128:3-5). Blessed is a man whose quiver (house) is full of children because they will not be put to shame when they contend with their enemies in the gate, court city, place of judgement, etc. Basden (1938: 44) writes in agreement that Africans (Igbo inclusive) are insatiably desirous of their children. In every community, they constitute a source of pride and joy for their parents. A man with many of them within his compound is considered wealthy and fortunate. A childless couple is usually taunted by its neighbors, despite the socio-economic motive or reasons for having many children. There are many subtle reasons that are based on African cosmology and religious beliefs, which include spiritual and religious beliefs, including the power and authority that children have in the day-to-day practice of faith (Onuwa, 1988 22). It is the children or survivors after a mans departure who remembers him through libation and other rites and rituals. This justifies the importance of wealth creation and its search for the Igbo.

The importance attached to proper and elaborate burial rites, rituals, and ceremonies is profoundly found in the Igbo interpretation of the universe as a duality, the physical, and the spiritual, which further situates the man as part of the ancestral world in death. To become an ancestor, aside from having survivors, living a good life, and dying after a ripe old age, the deceased must be accorded the proper burial rites if he must occupy his place in the spirit world. Igbo frontally sought peaceful entry into the spirit world from the day of his birth. He grows through adolescence, marries live his life, and later joins his ancestors. Thus, completing the circle of wealth is ready to be returned through the process of reincarnation. The circle continues on and.

Writing about the importance of ancestors in Igbo cosmology, Anyanwu (1999: 29) posits that they are living memories. They are dead and can be remembered by name. In this category, they are regarded as being closest to the family circle. They are called living dead because though they are physically dead, they are still within the family circle spiritually and, as such, are among the family members.

Putting together all that constitutes wealth in Igbo world-view, the Igbo human, by completing the circle, is interpreted to have fulfilled his purpose of existence or life. Thus, in Igbo cosmology, existentialism is attained through seeking and making wealth. By being born into the physical world and living out his life, the Igbo are trapped in existence, living in a world that is completely meaningless without the man who is the only creation that makes sense out of it. The universe and all that is therein are for the comfort and use of humans. The world is not configured by creation to be arbitrary in Igbos conception. He realizes the unintelligibility of the universe without him and the need for him to find some principles of order through his birth, growth, and death (a component of wealth). Like the existentialist, the Igbo by the configuration of the universe through his inescapable seeking of wealth is confronted by his dreadful freedom, recognizing that he is completely free to choose his worldview through his experiences and convictions. By the combination or interplay of universal forces, the Igbo human person cannot avoid making a choice as he is precluded from escaping from the consequences of the choices of his basic decisions.

Igbo wealth is likened to prosperity in Hebrew, which focuses on making progress, championing a cause, fulfilling a mission, and reaching a destiny (Bowen, 2012: 13). There are a number of instances when wealth (prosperity) in the old testament indicates the fulfillment of a task or assignment that is to be accomplished. Judges 4:24 says and the hands of the children of Israel prospered. In Igbo world-view, you are only prosperous if you have wealtha feature of all encompassing meaningold age, good life, good name, riches, offspring, good death, burial, second burial, all the rites and rituals of life celebration. In the old testament instance, this implies that the people of God (created by God) were successful. In 2 chronicles 22:30, the old testament observes, and Hezekiah prospered in all his work. Here, prosperity, like wealth in Igbo cosmology, means accomplishing tasks and making the desired difference in life. Seeking wealth seeks a path to true living and existence. The Igbo does not find the answer for true existentialism only in his religious faith (the supernatural), but also in his humanistic approaches and convictions, in the ways of dealing with his neighbors as belonging to the committee of people in need of one another.

Conclusion

The African Igbo has a meaning and interpretation of wealth, which includes death as a component of wealth. Based on this, there were two types of deaths. The bad and good death. While bad death brings grief, pain, and sadness, and is therefore abhorred by all, it is the desire of every Igbo to experience good death, which completes the ingredients or elements of wealth. The wealth, so interpreted/understood if achieved, equals prosperity. Prosperity for the Igbo is not just rich, but like the Hebrews is a destination to be sorted, or a progress to be made. The championing of a cause, fulling a mission or reaching (prosperity). The Igbo, in recognition of his nobility, strives in legitimate engagements to make the non-human component of wealth, which in turn enhances his bearing to make the human component of wealth with the support of the super sensible world. In arriving at his destination of true existentialism, he transcends to the next stage of his life essence, wherein the third component of wealth manifests in his physical absence, which surely enhances his position and propels him into another role.

Igbo observes and enjoys the first two elements of wealth in his greater physical life manifestation, while his survivors grace and adore the last. He seeks this wealth to fulfill his purpose and destiny. He progresses to a super sensible world, retaining contact with his family and waiting to return in due season (through reincarnation). It is a cycle. It goes on, and one until eternity. He does not seek this wealth for his own (personal) enjoyment, aggrandizement, or other selfish reasons. The wealth is for the good of humanity and for the purpose of his existence and meaning of life. Metuh (1987: 88) captures this meaning aptly, as he opines that Igbo interprets the world as a journey that commences physically in the physical world. He expresses it firmly in an idiomatic expression thus, we are on a market trip on the earth, whenever our time is up, we go home” (ihe anyi biara na uwa bu ahia, Onye zucha nke ya o la). This is the interpretation and meaning given to their children Onwudinuba (death is a component of wealth).

Lessons and Recommendations

(1) This serves as a spring board for more research in similar areas that Afro-centic scholars should leverage to investigate other peoples philosophies of life.

(2) Names in Igbo cosmology are not given to people. They reflect the minds and worldviews of people. Therefore, for a better understanding of African Igbo, an understanding of the meaning they attach to life is equally important for a harmonious relationship and a stable social order.

(3) The African Igbo has a philosophy of life encapsulated in their worldview. Scholars across the board should, therefore, resist the attempt to denigrate Africa as having no philosophy or that they are merely applying irrational principles in the interpretation of their world.

(4) Research such as this is a conscious attempt to preserve African culture and philosophy for prosperity. People without a culture are like trees, without roots. All hands should be on deck for the continuous promotion of African culture in similar and other ways.

Appendix

List of Interviewees

Amos, Nwandu M (79 years) - Interview conducted on the 13th June 2021 in Mbano

Ebisike, Ugwoagbala M (70 years) - Interview conducted on the 13th June 2024 in Uboma.

Eke, Ibeneche M (80 years) - Interview conducted on the 13th June 2024 in Uboma

Onyedikachi, Ugwulebo M (67 years) - Interview conducted on the 17th February 2020 in Ikwo

Eze, Uchenna Odika M (71 years) - Interview conducted on the 17th February 2024 in Okigwe

Onyeagboso Ngozichukwuka F (80 years) - Interview on the 17th February 2020 in Nsukka

Nwokorie Agbim Udemba F (66 years)- Interview conducted on the 8th April 2024 in Bende

Onyemauchechukwu Agajemba M (81 years)- Interview conducted on the 8th April 2020 in Ngwa

Mbadiegwu Onyeama M. (66 years) - Interview conducted on the 24th April 2024 in Abakaliki

Beneditta Osiamam F (77 years)- Interview conducted on the 30th April 2020 in Ikwo

Ugwulota Okolie M (65 years)- Interview conducted on the 8th August 2020 in Enugu

Samuel Igwenagummadu M (60 years)- Interview conducted on the 11th November 2020 in Awka

Moses Ukomadu M (75 years) - interview conducted on the 15th December 2020 in Nnewi

References

- Achebe, C. 1959. Things Fall Apart, London, Heinemann Educational books.

- AfIgbo, A 1981. Ropes of sand. Studies in Igbo History and culture. Oxford university press.

- Afuekwe, A.I 1992. A philosophical inquiry into Religion and social life in Igbo Lan-Alor as a case study Calabar; Associated publisher and consultant Ltd.

- Amaegwu, O. J 2013. Globalization Vs African cultural values. (Vol, 11), Enugu, san press.

- Aniakor, C. 1984. Ikenga Art and Igbo cosmos., journal of African studies Vol. 1 no.1.

- Anyacho, E. 2016. Igbo Traditional Religion and cosmology in Etim, E.O (ed) (2016) Igbo traditional Religion, culture and society, Calabar, Afri-penticost Academic publishing.

- Anyanwu, H.O. 1999. African Traditional Religion from the Grassroot, Uyo, saviour prints.

- Basden, G.T. 1938. Niger Ibos, London, Frank Cass.

- Berk, M et al. 2015. The use of mixed methods in Drug Discovery in Tohen, M. et al. (ed) (2015). Clinical Trial design challenges in Mood Disorders, USA, El sevier Inc.

- Bowen, B.J. 2012. Prosperity Gospel and its Effects on the 21st Century Church, USA, Xlibris Corporation.

- Dyer, J. 2010. Hermeneutics in Peterson, petal (ED) (2010) International Encyclopaedia of Education (3rd ED) USA, El sevier.

- Enekwe, O. 1987. Igbo masks. The oneness of Ritual and theatre, Lagos Federal Ministry of information and culture.

- Floyd, B. 1969. Eastern Nigeria: A Geographical Review, London: MacMillan publishers.

- Guyer J. I. 1995. Wealth in people, Wealth in things introduction the Journal of African History Vol.36 no. 1. 83 -90.

- Ibile, F. 2022. Igbo people. www.joshuaproject.net.

- Inclusive Wealth Report: Ihdp, unu. edu July 9th, 2012, retried July 14th, 2012.

- Magee, L. et al. 2011. Towards a semantic Wed connecting knowledge in Academic Research, USA, Woodhead publishing limited.

- Mbiti, J.S.1969. African Religious and philosophy, London, Heinemann Books, Ltd.

- Mensah, E.O and Iloh, Q.I 2021. Wealth is king. The conceptualization of wealth in Igbo personal naming practices. Anthropological Quarterly Vol. 94, no. 4. 699-723. [CrossRef]

- Metuh, E.I. 1986. comparative studies of African traditional Region, Onitsha, Imico publishers.

- Nwala, T.U. 1985. Igbo philosophy Lagos, Literamed publications.

- Nwanegbo- Ben, J and OzoIgbo, B.I. 2021. Entrepreneurship and the cubana principle As the basis of Igbo. Cosmology journal of humanities and social policy, Vol. 7 no.1.

- Nwaorgu, A.E. 2001. Cultural symbols. The Christian perspective, Owerri, T Afrique International Association.

- Nwoye, C.M.A. 2011. Igbo Cultural and Religious World-view: An Insiders Perspective, International Journal of Sociology and Anthropology, Vol. 3, no .9.

- Onunwa, U.R. 1990. Studies in Igbo Traditional Religion, Obosi, Pacific publishers Ltd.

- Onuwa, U.R. 1988. Igbo Traditional Attitude to children. A religious interpretation of a socio-economic need, JSTOR, Vol. 43. No.4.

- Onyemechalu, S. (2020, April 16). Map of Nigeria showing the South-eastern Region.

- Onyeocha, M. 1997. Africa: the question of identity. Washington D.C the council for Research in values and philosophy.

- Onyeocha, M. 2007. African the country the concept and the Horixon, Owerri, Imo state university press, Ltd.

- Onwubuariri, J.O. 2011. Classical African indigenous religious thought, Owerri, Tonyben publishers.

- Pallis, CA. 1983. The ABC of Brain stem Death. British Medical Journal London. www.books.google.com.ng.

- Quarcoopome, T.N.O. 1987. West African Traditional Religion, Ibadan, African universities press.

- Slattery, K. 2016. The Igbo people origin and History, Belfast, school of English, Queens university of Belfast. www.faculty.ucr.edu.

- The Economist (June 30th, 2012). Free Exchange. The real wealth of nations. Retrieved July 14th, 2012.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).