2.1. Preliminary Estimates

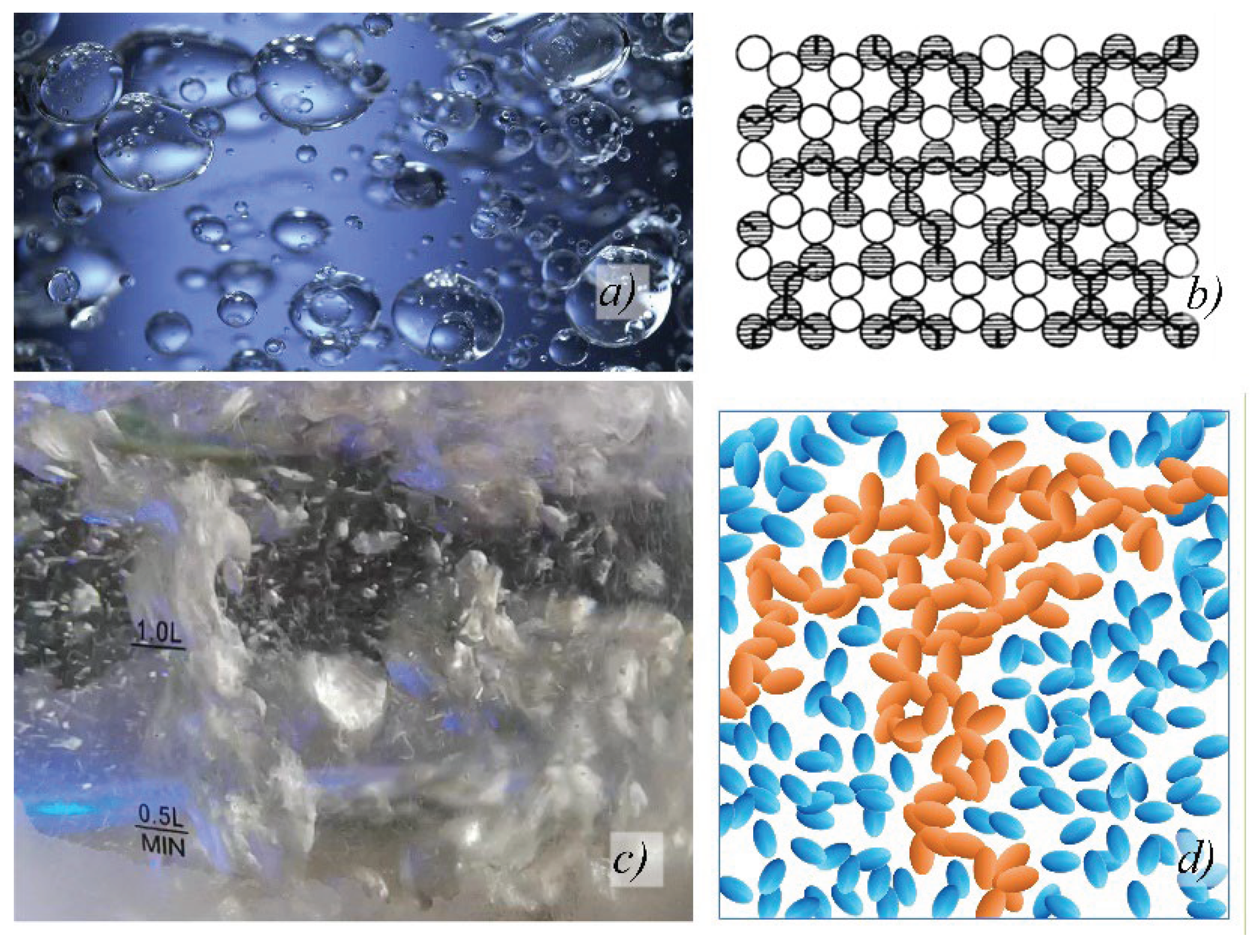

The key object of our study is a vapor bubble, both immediately before its separation from the hot surface and during its ascent. The bubble's ascent velocity depends, among other things, on its size and can be variable. Some researchers believe that the growth of bubbles during their merging slows their ascent and is a mechanism that reduces heat flux [

6]. Since this explanation is simpler than the occurrence of a percolation transition, we will qualitatively evaluate its contribution to the change in heat flux. Note that the heat flux from the surface is proportional to the volume of the rising bubbles and their ascent velocity. To initiate boiling on the substrate from which heat is removed, a liquid superheat of several degrees must be created. Superheat is defined as the difference between the liquid temperature and the saturation temperature T

s. The superheat field must form in a thin liquid layer, approximately several hundred microns thick, above the substrate surface. Within the cavities and irregularities of the substrate, unstable vapor nanobubbles with a characteristic size of approximately one nanometer spontaneously emerge. Due to stochastic Brownian coagulation, the bubbles coalesce, eventually forming a bubble of critical size [

6]. This bubble is held to the substrate by surface tension forces around the perimeter of the bubble's "neck." Within the superheated liquid layer, the bubbles grow to hundreds of microns in size and break away under the action of Archimedes' force.

For boiling on a substrate, studies have found two ranges of bubble sizes, differing by two orders of magnitude [

6]. The first range is called critical. With superheating of a few degrees, the characteristic size of a critical liquid vapor bubble in a conical cavity on a substrate is approximately 1 μm. Critical bubbles can grow indefinitely. The second range of bubble radii is called separation. The radius of separation bubbles is several hundred microns. These bubbles detach from the substrate due to the Archimedes force and carry the bulk of the energy during boiling.

At the point of the first boiling crisis, the heat flux removed reaches a maximum and begins to decrease. Most of the heat is removed from the hot surface in steam bubbles. As noted above, one of the simplest explanations for the boiling crisis and the resulting slowdown in heat removal is a decrease in the bubble ascent velocity. This change in velocity can be caused by bubble coagulation or a change in external pressure as the bubbles rise. Let's consider the effect of coagulation. For the laminar ascent of a spherical bubble of radius R

b, the steady-state velocity of a single bubble in a liquid,

v, can be calculated using the expression

where µ is the viscosity of the liquid,

,

are the liquid and vapor densities, respectively, and g is the acceleration due to gravity. In fact, equation (1) is a lower bound estimation for the velocity of bubbles in a flow moving in one direction. It follows from this formula that in the laminar Stokes regime of bubble rising, the rate of energy transfer should only increase as the vapor bubbles coagulate. As the critical point is approached, the bubbles begin to interact with each other and significantly turbulize the flow. The dependence of the bubble ascent velocity on the bubble radius in the turbulent regime has a different character [

7]. The nature and features of the motion of gas bubbles in this regime were analyzed in detail in the works of Malenkov [

8] and Kutateladze [

9]. This regime is characterized by two size ranges of rising bubbles, corresponding to Reynolds numbers Re ~ 10-100 and Re ~ 1000. The first regime can be considered a transitional form associated with changes in the bubble's shape and dependent on the surface tension σ of the liquid. The bubble's ascent velocity in this regime can be determined from dimensional theory considerations:

This regime is intermediate for the entire size range of air bubbles in water. It operates at

Rb ≈ 3...5 mm and exhibits a decrease in velocity with increasing bubble size. Equation (2) is a special case of the expression for the bubble ascent velocity obtained by Malenkov for the entire range of Reynolds numbers (Re ~ 10...1000):

Here, the numerical coefficients α and β, according to Malenkov, are close to 1. The characteristic times for establishing a steady-state ascent velocity do not exceed 0.1 s for any regime. Generally, the dependence of the ascent velocity of gas bubbles in a liquid on their radius is nonmonotonic: it increases rapidly in the diameter range from hundreds of microns to approximately 2 mm, then decreases just as rapidly to a size of ~5 mm. It then remains approximately constant in the diameter range of 5-10 mm and increases slowly at larger sizes. Coagulation "drives" the bubble along this size range; in the intermediate size range, it slows the bubbles, possibly thereby further turbulizing the flow. This pattern partially confirms the hypothesis that, during the coagulation of intermediate-sized bubbles at a certain height from the substrate, the bubbles can slow their velocity and partially slow heat removal. However, in our opinion, such behavior cannot fully explain the occurrence of a boiling crisis. Even if we narrow the bubble size spectrum through a specific hot surface morphology, the bubble slowing mechanism by coagulation is still monotonic and cannot, from a mathematical point of view, yield a singular point. This mechanism may adjust the absolute value of the critical heat flux, but it does not determine the underlying mechanism. We believe that the primary mechanism for the occurrence of a boiling crisis is percolation-based.

2.2. Continuum Percolation Problem

For further consideration, we need a brief overview of the key aspects of continuum or off-lattice problems of percolation theory. Percolation theory is currently the dominant scientific concept in describing heterogeneous disordered media and systems with fully stochastic structure [

10,

11]. The classic and best-developed example of a percolation problem is the conductivity problem, or the dielectric-metal transition. In this problem a mixture of dielectric and metallic balls or particles is considered. When metallic balls are added to the dielectric ones, at a certain concentration, macroscopic electrical conductivity arises in the system. Percolation theory describes the emergence of macroscopic conductivity in such a system. More generally, percolation theory describes the emergence of macroscopic connectivity in a disordered system for one of the components. The condition of local connectivity in each problem has its own meaning – from direct contact of particles to the overlap of virtual regions of physical interaction. For example, when a combustion wave propagates through a heterogeneous mixture of fuel and inert particles, the connectivity condition is the condition of the fresh particle entering the heating region around the burnt particle, where the temperature is higher than the ignition temperature [

12]. Direct contact is a special case of the connectivity condition.

A percolation cluster (PC) is the most interesting and important object in such a heterogeneous system. It is a cluster that joints only sites (objects) of a similar type, for example, only metal balls in its mixture with dielectric ones. So, one can travel to infinity from any PC site by moving only along the sites of a given cluster, i.e., along metallic balls. A PC possesses a whole set of fractal properties. It can be distinguished by several subsystems, the main ones being the skeleton and the surface. Removing skeleton sites leads to a rupture of macroscopic connectivity. The surface of a percolation cluster is a collection of cluster sites adjacent to sites of another type. Macroscopic connectivity arises in such a system when a percolation cluster forms from connected sites.

Historically, the first problems were those of percolation on lattices. In these problems, the sites of regular spatial lattices were considered, some of which were occupied, some free. Next, the minimum fraction of occupied sites was found at which a percolation cluster occurred in the system. Thus, for the site problem on a 2D square lattice, this threshold is p

c ≈ 0.5927, and on a 3D cubic lattice, p

c = 0.3116077 ± 0.0000004 [

13].

Continuum percolation theory arose as an extension of discrete lattice percolation theory to continuous Euclidean space. It was first formulated based on ideas from early lattice problems and was associated with the need to describe the first wireless communication networks [

14]. The base points of discrete percolation form various types of lattices. In the general case, the base points of continuum percolation are stochastically located in some continuous space. In the context of the problem under consideration, these may be the growth centers of vapor bubbles or the centers of mass of such bubbles as they rise (

Figure 1). Each point may be associated with a specific geometric object (a shape—a sphere, ellipsoid, cube, cylinder, etc.). In the simplest case, this is a circumscribed circle for two-dimensional problems or a sphere for three-dimensional ones. For example, for the problem of signal transmission over a network of cellular towers, the sites are the locations of the towers, and the geometric shapes are the coverage areas of these towers, which, due to local topographic features, may differ from a circle. It should be noted that sometimes this form can represent the real forms of physical objects – for example, particles of one material randomly distributed in a matrix of another material [

15]. Sometimes, for a number of problems, these forms are virtual and represent, for example, the region of some physical interaction of particles [

16]. In general, two large classes of continuum problems are considered – problems on non-overlapping volumes (forms cannot penetrate or superimpose each other) [

17] and problems on overlapping volumes [

18]. Which class of problems describes the boiling problem is still an open question. During boiling, most bubbles do not overlap, and the total volume of merging bubble is, to a first approximation, equal to the sum of the volumes of the merged bubbles. Therefore, for the boiling problem, a description based on a percolation problem for non-overlapping volumes appears preferable. As for discrete percolation problems, the key question of study in continuum percolation is the conditions for the formation of a percolation cluster, i.e. macroscopic connectivity.

An important issue for this work is the percolation threshold in continuum problems. The development of continuum percolation is closely related to the work of Sher and Zallen [

19]. Percolation thresholds for lattice problems vary widely, and it is difficult to discern any pattern in their values. However, there is an approximate invariant for them, which was described by Sher and Zallen. They constructed a circle (or sphere) around each lattice site with a radius equal to half the distance to the nearest neighbor (Fig. 1c). Note that such a construction corresponds to the continuum problem for non-overlapping volumes. Sher and Zallen calculated the fraction of the area (volume) that is located within such circles (spheres) constructed around occupied sites at the percolation threshold. It turned out that the relative volume φ

c occupied by such spheres at the percolation threshold is an approximately constant value, depending only on the dimensionality of the space:

This construction was the first step in understanding the properties of continuum percolation. The problem of continuum percolation on random sites is formulated as follows. Consider a stochastic system of points randomly distributed in space with an average concentration n per unit volume. Let ξ

ij be a function of the vector r

ij connecting points i and j. We define a number ξ and assume that sites i and j are connected if the inequality ξij ≤ ξ, which is called the connectivity condition, is satisfied. If two sites are connected directly or via pairwise connected sites, they are said to belong to the same cluster. The percolation threshold ξ

c is defined as the lower value of the parameter ξ for which a percolation system exists. The simplest of these problems is the problem with the connectivity condition r

ij ≤ R. This condition is satisfied if site j is located within a sphere of radius R circumscribed around site i. This problem has a simple geometric interpretation. Let spheres of equal radius R be constructed around stochastically distributed sites. The problem is to find, for a given concentration of sites n, the smallest value of R = R

c such that infinite chains of sites exist such that each subsequent sites lies inside the sphere constructed on the previous one. In some problems, it is more convenient to construct spheres with radius R/2 (analogy with the Scher-Zallen construction). In this case, sites are considered connected if their spheres intersect. Pike and Seeger [

20] proposed calling the first construction enclosing spheres (circles), and the second, overlapping spheres (circles).

Consider a three-dimensional region with linear dimension

L and volume

V = L3.

N particles (bubbles of radius r) are randomly distributed within this region. The numerical concentration of particles is

n = N/V. Then the volume fraction of the space occupied by the spheres circumscribed around the particles is:

Let's consider the problem of overlapping spheres. Consider an arbitrary point in space. We'll find the probability

that none of the

N particles and the spheres circumscribed around them fall into that arbitrary point in space. Given their uniform distribution throughout the volume

Then we obtain the following relationship between the volume fraction

and the volume fraction

of space occupied by intersecting spheres, taking into account their random overlaps:

The parameter φ

с represents the percolation threshold for continuum problems. It depends on the spatial dimension d and on the shape of the interacting geometric objects embedded within the space. For the problem on overlapping circles and spheres, the most accurate calculation result to date is as follows [

21]:

These values of the quantities characterizing thresholds in 2D and 3D systems with a uniform space distribution of particles (bubbles) are valid for both the non-overlapping and overlapping spheres (circles) problem.

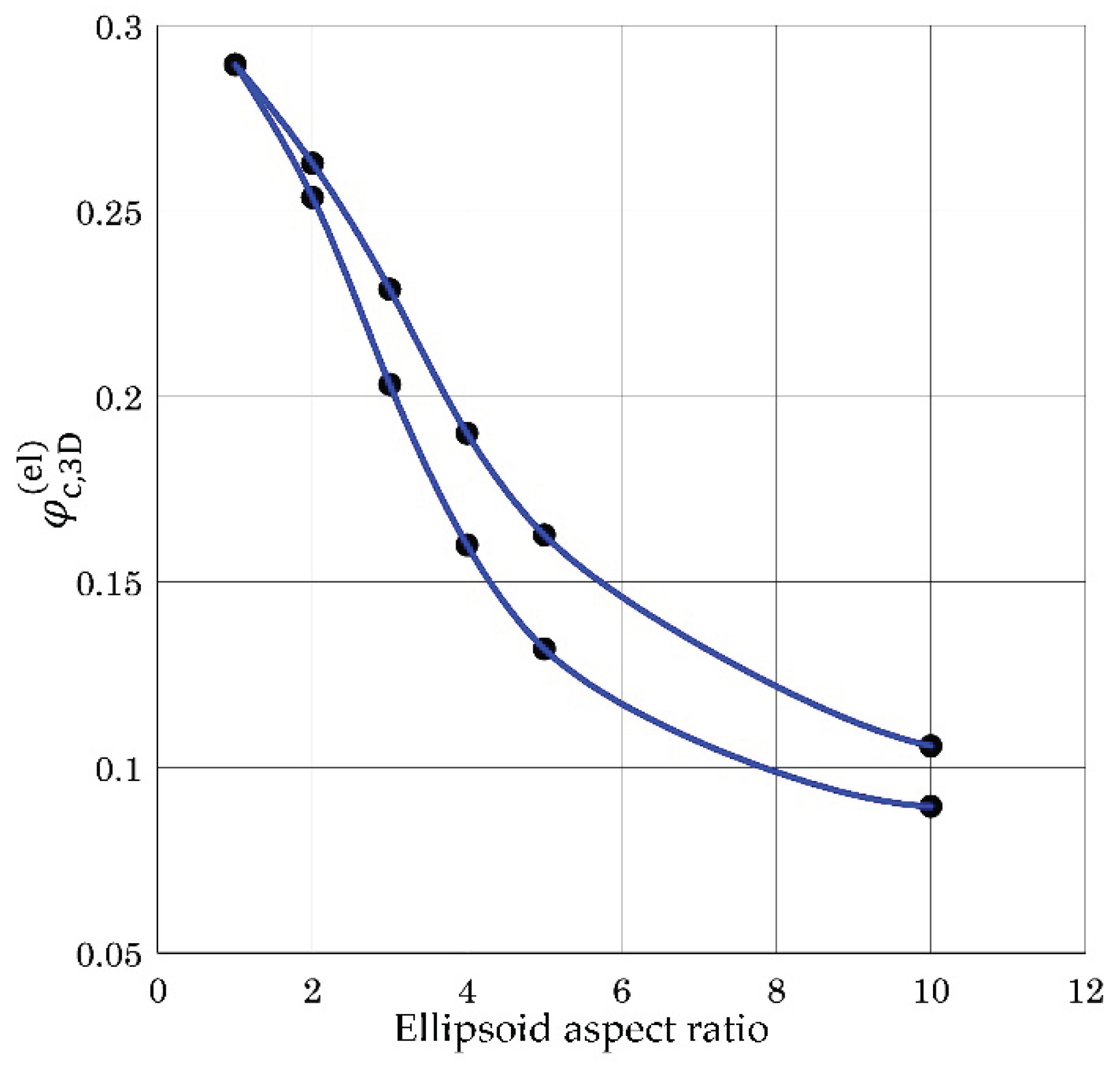

If the shape of the interacting geometric objects differs from spheres, then the threshold value may also change. For example, for ellipsoids of revolution (

Figure 1d)

where

a and

b are the major and minor axes of the ellipsoid [

22].