Submitted:

11 December 2025

Posted:

12 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Study Area

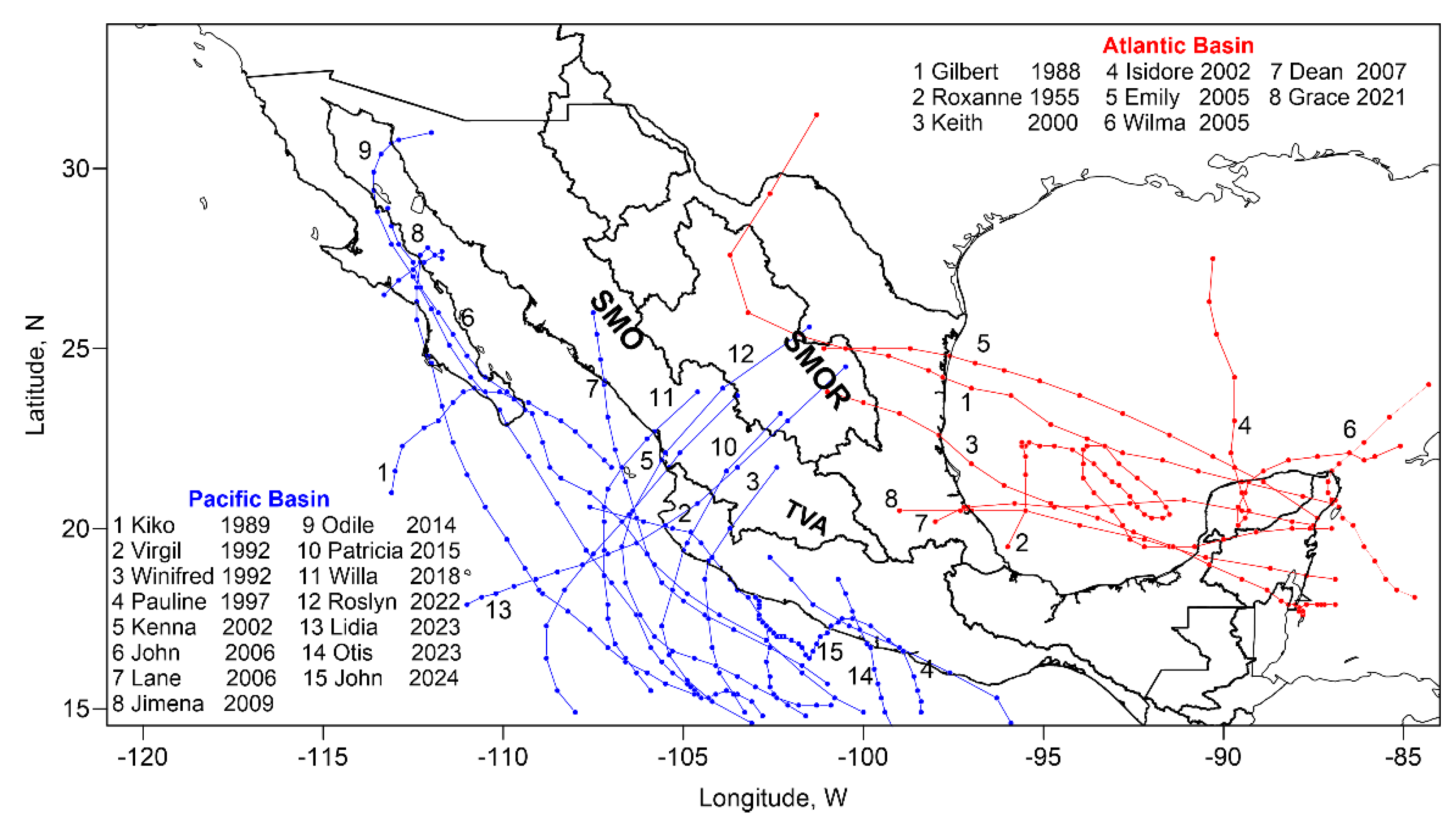

2.2. Tropical Cyclones

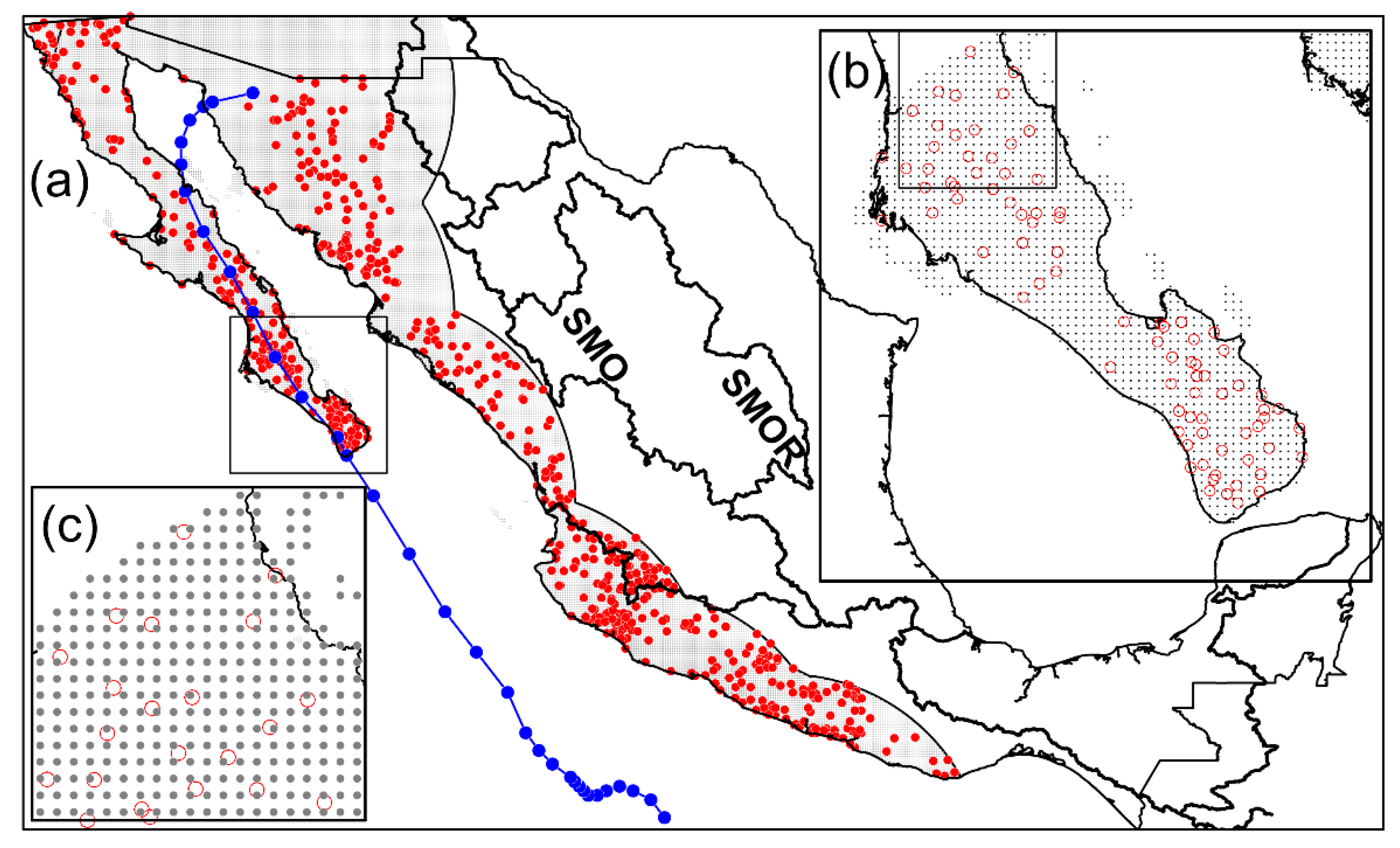

2.3. Observational Data

2.4. CHIRPS Dataset

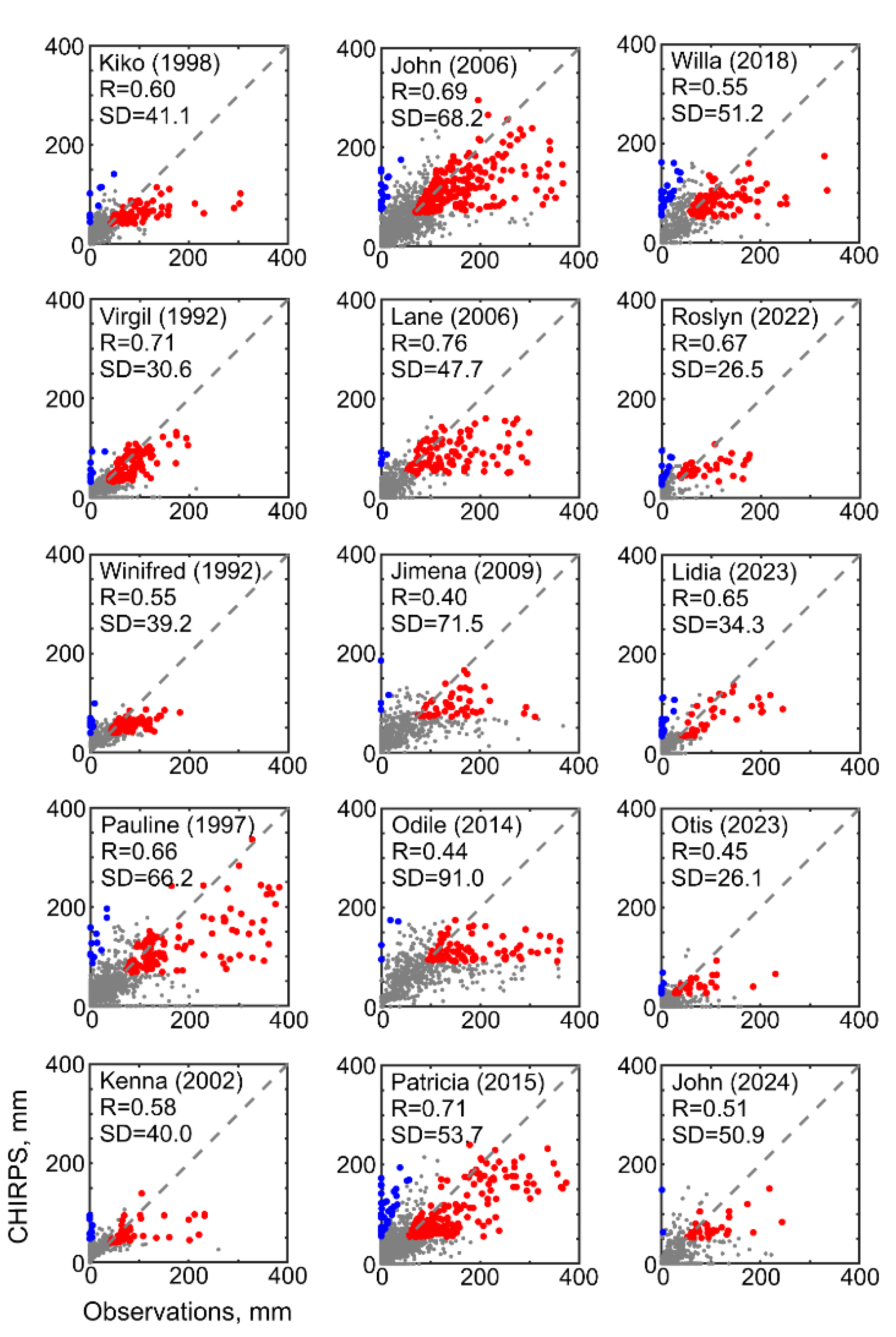

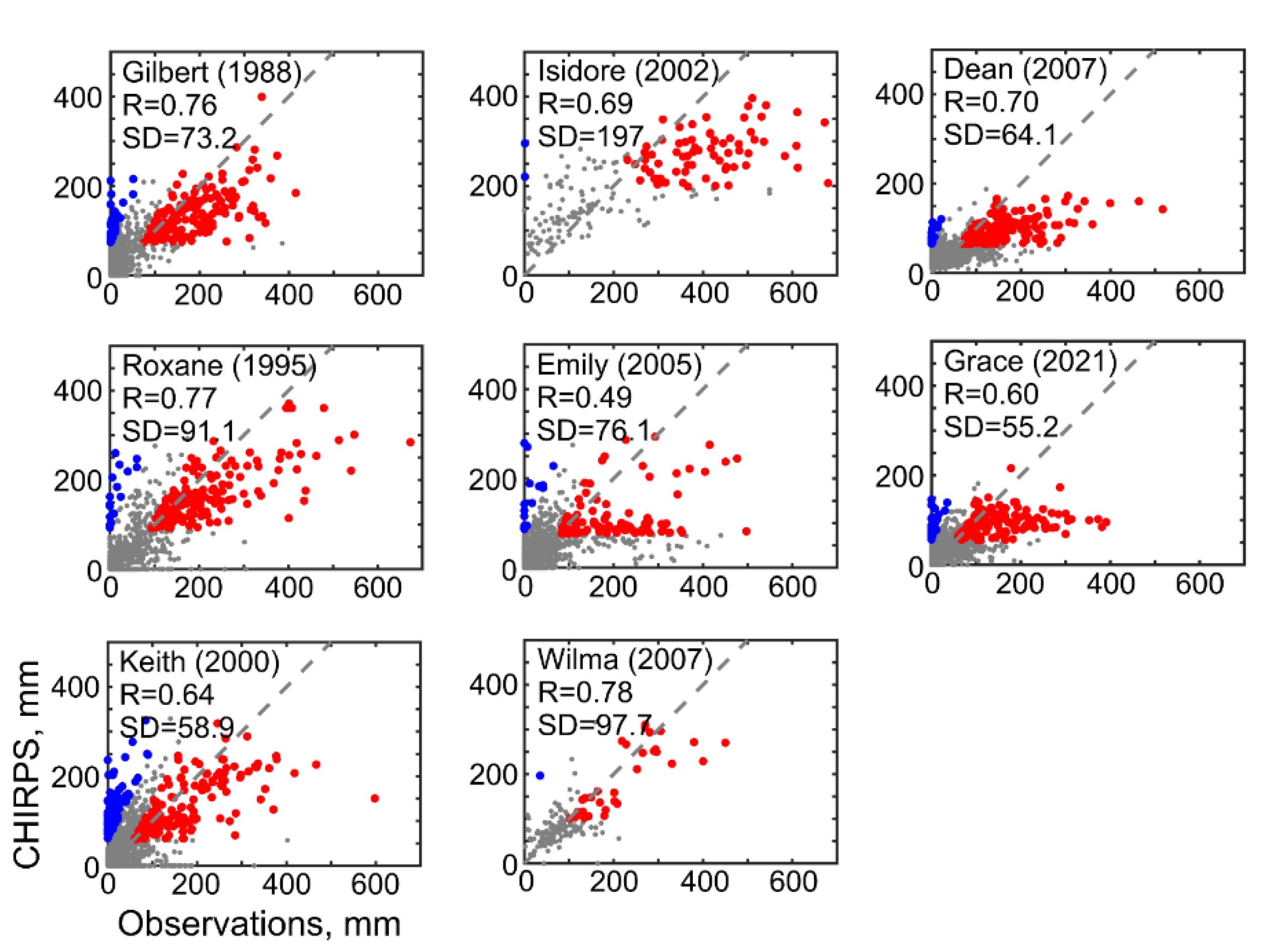

2.5. CHIRPS Gridded Dataset Versus Observations

2.6. Cumulative Precipitation

3. Results

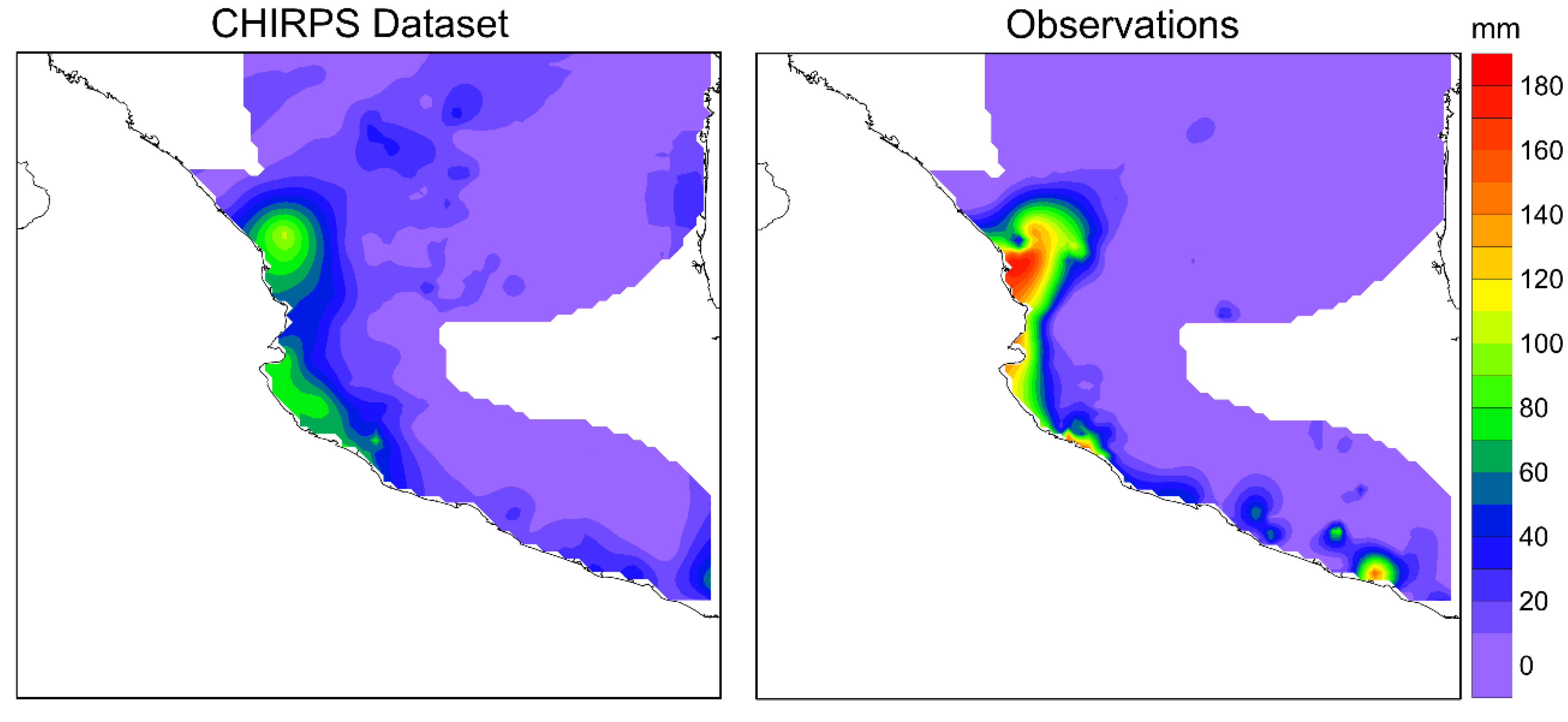

3.1. Cumulative Precipitation in the Eastern Pacific and Atlantic Basins

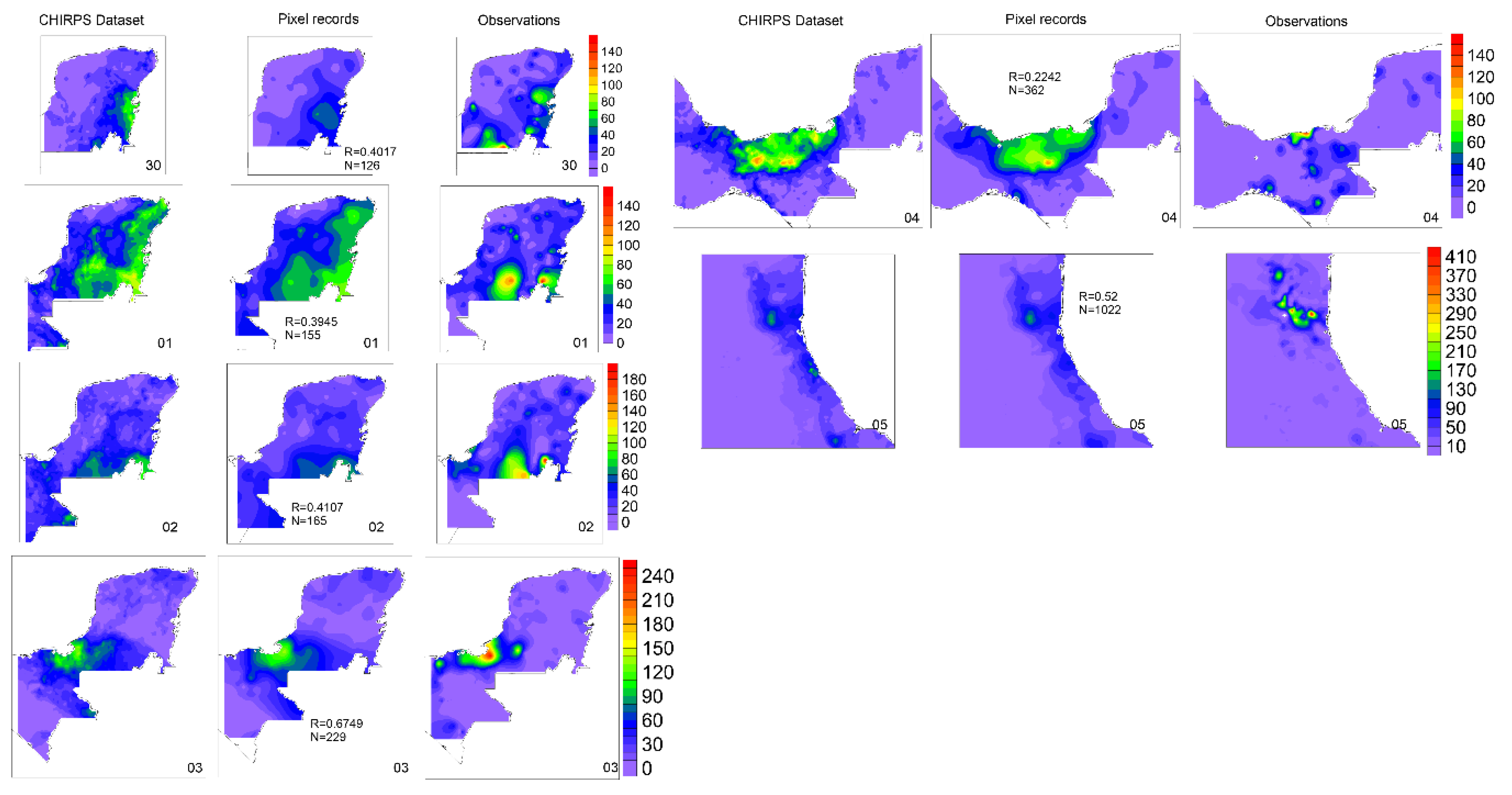

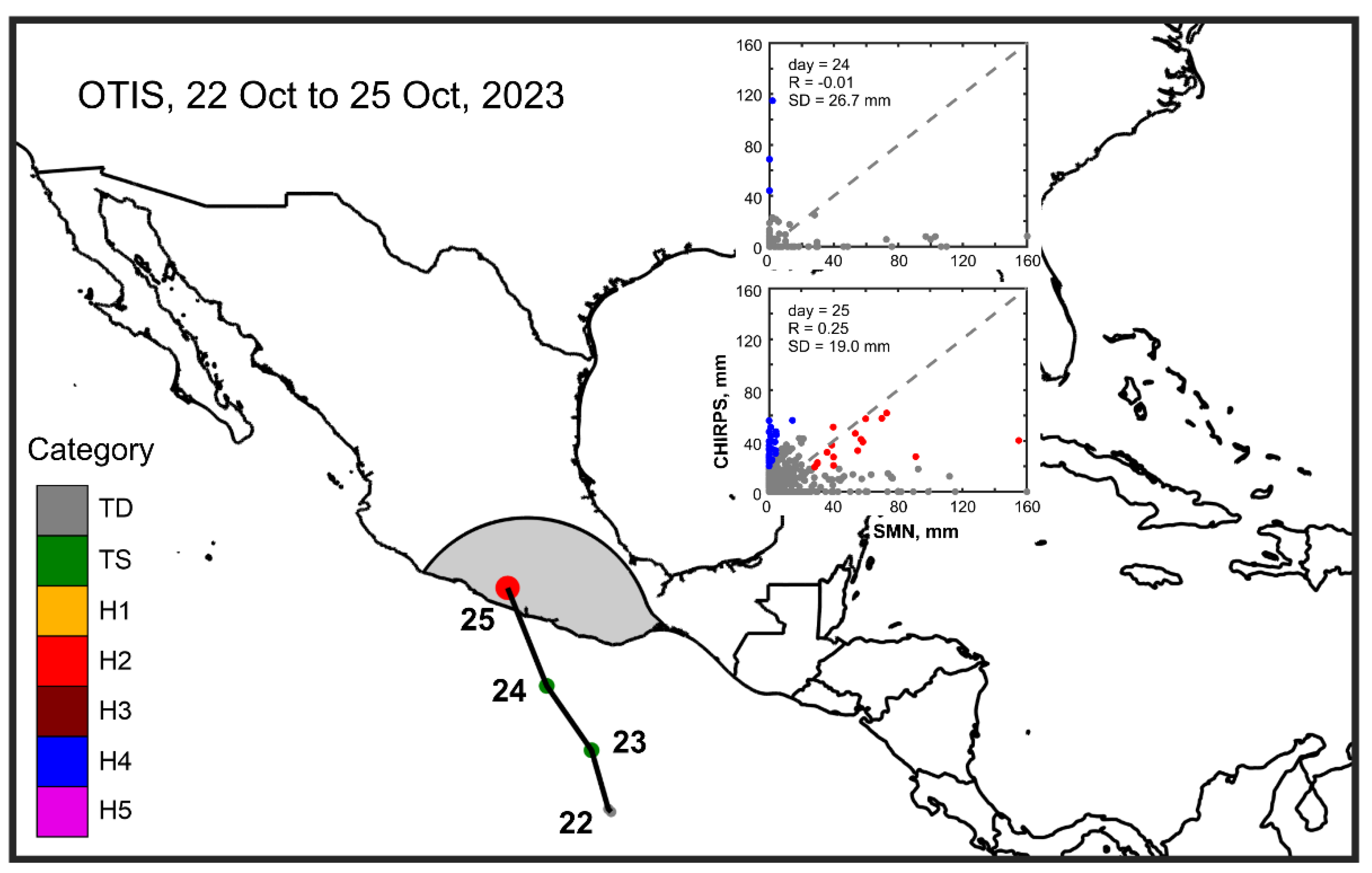

3.2. Specific Dates Analysis in the Eastern Pacific

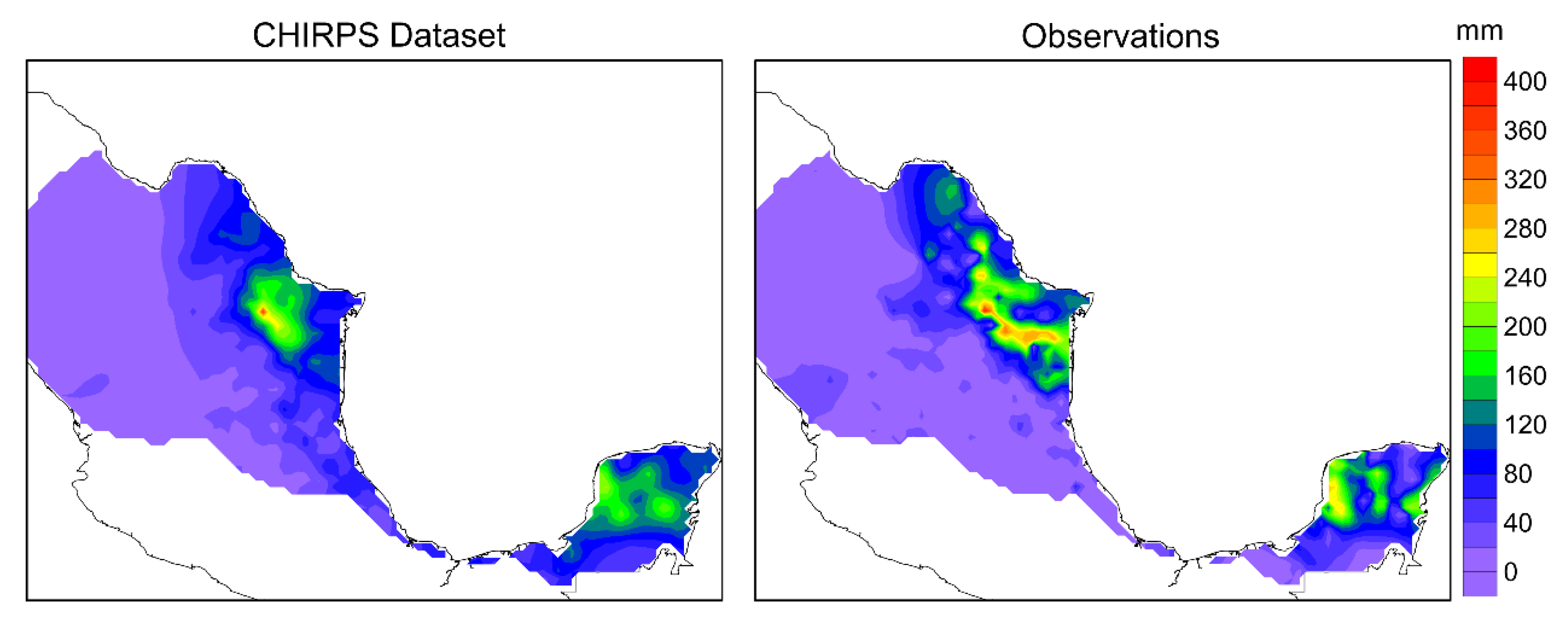

3.3. Specific Dates Analysis in the Atlantic Basin

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- The correlations between observations and estimates, in some cases, were statistically significant. However, this result does not guarantee congruence between observations and estimates since, as discussed, CHIRPS fails to adequately reproduce the position of the highest precipitation core, to overestimate small precipitation, and to underestimate large precipitation.

- When the correlation between observed and estimated precipitation is higher, CHIRPS is able to reproduce the precipitation pattern quite well, although it tends to overestimate the area of very large precipitation.

- Based on the average correlation between observed and estimated precipitation, the Atlantic basin shows a higher correlation than the Pacific basin, indicating that, in general, CHIRPS better replicates the precipitation distribution pattern in the Atlantic.

- In the initial stages of TC, CHIRPS is unable to reproduce the accumulations of precipitation resulting in low correlations between the observations and database estimates.

- It is recommended to use CHIRPS with caution when the focus is on analyzing rainfall patterns during the development of intense tropical cyclones.

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Englehart, P.J.; Douglas, A.V. Dissecting the Macro-scale Variations in Mexican Maize Yields (1961-1997). Geographical and Environmental Modelling 2000, 4, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, A.; Wolff, H. Concept and Unintended Consequences of Weather Index Insurance: The Case of Mexico. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 2011, 93, 505–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogé, P.; Friedman, A.R.; Astier, M.; Altieri, M.A. Farmer Strategies for Dealing with Climatic Variability: A Case Study from the Mixteca Alta Region of Oaxaca, Mexico. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems 2014, 38, 786–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englehart, P.J.; Douglas, A.V. Mexico’s summer rainfall patterns: an analysis of regional modes and changes in their teleconnectivity. Atmósfera 2002, 15, 147–164. [Google Scholar]

- Giddings, L.; Soto, M.; Rutherford, B.; Maarouf, A. Standardized Precipitation Index Zones for México. Atmósfera 2005, 18, 33–56. [Google Scholar]

- Seager, R.; Ting, M.; Davis, M.; Cane, M.; Naik, N.; Nakamura, J.; Li, C.; Cook, E.; Stahle, D. Mexican drought: an observational modeling and tree ring study of variability and climate change. Atmósfera 2009, 22, 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- Colorado-Ruiz, G.; Cavazos, T. Trends of daily extreme and non-extreme rainfall indices and intercomparison with different gridded data sets over Mexico and the southern United States. International Journal of Climatology 2021, 41, 5406–5430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, T.; Chiang, J.C.H. Spatial variability and mechanisms underlying El Niño-induced droughts in Mexico. Climate Dynamics 2014, 43, 3309–3326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, K.; Yu, Z.; Elsberry, R.L.; Bell, M.; Jiang, H.; Lee, T.C.; Lu, K.-C.; Oikawa, Y.; Qi, L.; Rogers, R.F.; et al. Recent Advances in Research and Forecasting of Tropical Cyclone Rainfall. Tropical Cyclone Research and Review 2018, 7, 106–127. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Monroy, V.H.; Farfán, L.M.; Brito-Castillo, L.; Cortés-Ramos, J.; González-Rodríguez, E.; D’Sa, E.J.; Euan-Avila, J.I. Tropical Cyclone Landfall Frequency and Large-Scale Environmental Impacts along Karstic Coastal Regions (Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico). Applied Sciences 2020, 10, 5815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breña-Naranjo, A.J.; Pedrozo-Acuña, A.; Pozos-Estrada, O.; Jiménez-López, S.A.; López-López, M.R. The contribution of tropical cyclones to rainfall in Mexico. Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C 2015, 83-84, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khouakhi, A.; Villarini, G.; Vecchi, G.A. Contribution of Tropical Cyclones to Rainfall at the Global Scale. Journal of Climate 2017, 30, 359–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominguez, C.; Magaña, V. The Role of Tropical Cyclones in Precipitation Over the Tropical and Subtropical North America. Frontiers in Earth Science 2018, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englehart, P.J.; Douglas, A.V. The role of eastern North Pacific tropical storms in the rainfall climatology of western Mexico. International Journal of Climatology 2001, 21, 1357–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klotzbach, P. C.; Fogarty; Truchelut, R. Hurricane Otis: The strongest landfalling hurricane on record for the west coast of Mexico [in “State of the Climate in 2023”]. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2024, 105(8), S264–S265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colorado-Ruiz, G.; Cavazos, T.; Salinas, J.A.; De Grau, P.; Ayala, R. Climate change projections from Coupled Model Intercomparison Project phase 5 multi-model weighted ensembles for Mexico, the North American monsoon, and the mid-summer drought region. International Journal of Climatology 2018, 38, 5699–5716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- León-Cruz, J.F.; Carbajal Henken, C.; Carbajal, N.; Fischer, J. Spatio-Temporal Distribution of Deep Convection Observed along the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt. Remote Sensing 2021, 13, 1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, S.; Alsafadi, K.; Al-Awadhi, T.; Sherief, Y.; Harsanyie, E.; El Kenawy, A.M. Space and time variability of meteorological drought in Syria. Acta Geophysica 2020, 68, 1877–1898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perdigón-Morales, J.; Romero-Centeno, R.; Pérez, P.O.; Barrett, B.S. The midsummer drought in Mexico: perspectives on duration and intensity from the CHIRPS precipitation database. International Journal of Climatology 2018, 38, 2174–2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Oliver, E.C.J.; Ballestero, D.; Mauro Vargas-Hernandez, J.; Holbrook, N.J. Influence of the Madden–Julian oscillation on Costa Rican mid-summer drought timing. International Journal of Climatology 2019, 39, 292–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, C.; Peterson, P.; Landsfeld, M.; Pedreros, D.; Verdin, J.; Shukla, S.; Husak, G.; Rowland, J.; Harrison, L.; Hoell, A.; et al. The climate hazards infrared precipitation with stations—a new environmental record for monitoring extremes. Scientific Data 2015, 2, 150066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavalcante, R.B.L.; Ferreira, D.B.d.S.; Pontes, P.R.M.; Tedeschi, R.G.; da Costa, C.P.W.; de Souza, E.B. Evaluation of extreme rainfall indices from CHIRPS precipitation estimates over the Brazilian Amazonia. Atmospheric Research 2020, 238, 104879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Liu, J.; Tuo, Y.; Chiogna, G.; Disse, M. Evaluation of eight high spatial resolution gridded precipitation products in Adige Basin (Italy) at multiple temporal and spatial scales. Science of The Total Environment 2016, 573, 1536–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Carr, D.; Mwenda, K.M.; Pricope, N.G.; Kyriakidis, P.C.; Jankowska, M.M.; Weeks, J.; Funk, C.; Husak, G.; Michaelsen, J. A spatial analysis of climate-related child malnutrition in the Lake Victoria Basin. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), 26-31 July 2015, 2015; pp. 2564–2567. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera, J.A.; Marianetti, G.; Hinrichs, S. Validation of CHIRPS precipitation dataset along the Central Andes of Argentina. Atmospheric Research 2018, 213, 437–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Velázquez, M.I.; Herrera, G.d.S.; Aparicio, J.; Rafieeinasab, A.; Lobato-Sánchez, R. Evaluating reanalysis and satellite-based precipitation at regional scale: A case study in southern Mexico. Atmósfera 2021, 34, 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Romero, P.; Patiño-Gómez, C.; Martínez-Austria, P.F.; Corona-Vásquez, B. Rainfall/runoff hydrological modeling using satellite precipitation information. Water Practice and Technology 2022, 17, 1082–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavazos, T.; Luna-Niño, R.; Cerezo-Mota, R.; Fuentes-Franco, R.; Méndez, M.; Pineda Martínez, L.F.; Valenzuela, E. Climatic trends and regional climate models intercomparison over the CORDEX-CAM (Central America, Caribbean, and Mexico) domain. International Journal of Climatology 2020, 40, 1396–1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Ortigoza, S.; Hernández-Espriú, A.; Arciniega-Esparza, S. Regional modeling of groundwater recharge in the Basin of Mexico: new insights from satellite observations and global data sources. Hydrogeology Journal 2023, 31, 1971–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincón-Avalos, P.; Khouakhi, A.; Mendoza-Cano, O.; Cruz, J.L.-D.l.; Paredes-Bonilla, K.M. Evaluation of satellite precipitation products over Mexico using Google Earth Engine. Journal of Hydroinformatics 2022, 24, 711–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (INEGI), I.N.d.E.y.G. Panorama sociodemográfico de México: Censo de Población y Vivienda 2020; Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía: Mexico, 2020.

- De la Torre, E.Y. Los volcanes del Sistema Volcánico Transversal. Investigaciones Geográficas 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyra Jáuregui, J.A. Guía de las altas montañas de México y una de Guatemala; Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad (CONABIO), 2012; p. 415. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, K.R.; Diamond, H.J.; Kossin, J.P.; Kruk, M.C.; Schreck, C.J. International best track archive for climate stewardship (IBTrACS) project, version 4. NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information 2018, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Knapp, K.R.; Kruk, M.C.; Levinson, D.H.; Diamond, H.J.; Neumann, C.J. The International Best Track Archive for Climate Stewardship (IBTrACS): Unifying Tropical Cyclone Data. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 2010, 91, 363–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branski, F. Pioneering the collection and exchange of meteorological data. Bulletin of the World Meteorological Organization 2010, 59, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Dinku, T.; Funk, C.; Peterson, P.; Maidment, R.; Tadesse, T.; Gadain, H.; Ceccato, P. Validation of the CHIRPS satellite rainfall estimates over eastern Africa. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 2018, 144, 292–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paredes-Trejo, F.; Barbosa, H. A.; Kumar, T. V. L.; Thakur, M. K.; de Oliveira Buriti, C. Assessment of the CHIRPS-based satellite precipitation estimates. In Inland Waters-Dynamics and Ecology; IntechOpen., 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Eastern Pacific Basin | |||

| No. | TC Name | Highest Category | Dates |

| 1 | Kiko | H3 | August 25–29, 1989 |

| 2 | Virgil | H4 | October 01–05, 1992 |

| 3 | Winifred | H3 | October 06–10, 1992 |

| 4 | Pauline | H4 | October 05–10, 1997 |

| 5 | Kenna | H5 | October 22–26, 2002 |

| 6 | John | H4 | August 28–September 04, 2006 |

| 7 | Lane | H3 | September 13–17, 2006 |

| 8 | Jimena | H4 | August 28–September 05, 2009 |

| 9 | Odile | H4 | September 09–18, 2014 |

| 10 | Patricia | H5 | October 20–24, 2015 |

| 11 | Willa | H5 | October 19–24, 2018 |

| 12 | Roslyn | H4 | October 20–24, 2022 |

| 13 | Lidia | H4 | October 03–11, 2023 |

| 14 | Otis | H5 | October 21–25, 2023 |

| 15 | John | H3 | September 22–27, 2024 |

| Atlantic Basin | |||

| 1 | Gilbert | H5 | September 14–18, 1988 |

| 2 | Roxanne | H3 | October 10–21, 1995 |

| 3 | Keith | H4 | September 30–October 06, 2000 |

| 4 | Isidore | H3 | September 21–25, 2002 |

| 5 | Emily | H5 | July 17–21, 2005 |

| 6 | Wilma | H5 | October 21–23, 2005 |

| 7 | Dean | H5 | August 21–23, 2007 |

| 8 | Grace | H3 | August 19–21, 2021 |

| Name (Year) | Cat | n | p | |||

| Roslyn (2022) | H4 | 0.67 | 559 | 0.000 | 132/360 | 1.46 |

| Lidia (2023) | H4 | 0.65 | 446 | 0.000 | 141/163 | 1.16 |

| Kiko (1989) | H3 | 0.60 | 454 | 0.000 | 14/72 | 1.11 |

| Kenna (2002) | H5 | 0.58 | 329 | 0.000 | 13/61 | 1.20 |

| Willa (2018) | H5 | 0.55 | 478 | 0.000 | 47/71 | 1.02 |

| Virgil (1992) | H4 | 0.71 | 830 | 0.000 | 266/109 | 0.76 |

| Pauline (1997) | H4 | 0.66 | 1182 | 0.000 | 110/81 | 0.95 |

| John (2024) | H3 | 0.51 | 397 | 0.000 | 160/20 | 0.59 |

| Otis (2023) | H5 | 0.45 | 628 | 0.000 | 330/225 | 0.56 |

| Odile (2014) | H4 | 0.44 | 597 | 0.000 | 46/44 | 0.75 |

| Lane (2006) | H3 | 0.76 | 956 | 0.000 | 221/256 | 0.94* |

| Patricia (2015) | H5 | 0.71 | 1351 | 0.000 | 94/120 | 0.94* |

| John (2006) | H4 | 0.69 | 1235 | 0.000 | 45/91 | 0.98* |

| Winifred (1992) | H3 | 0.55 | 336 | 0.000 | 0/17 | 0.99* |

| Jimena (2009) | H4 | 0.40 | 472 | 0.000 | 8/44 | 0.79* |

| average | 0.56 |

| Name (Year) | Cat | n | p | |||

| Gilbert (1988) | H5 | 0.76 | 1002 | 0.000 | 76/145 | 1.19 |

| Wilma (2005) | H5 | 0.78 | 149 | 0.000 | 2/0 | 0.94 |

| Roxane (1995) | H3 | 0.77 | 909 | 0.000 | 213/145 | 0.88 |

| Emily (2005) | H5 | 0.49 | 1046 | 0.000 | 93/85 | 0.84 |

| Dean (2007) | H4 | 0.70 | 1062 | 0.000 | 0/121 | 0.86* |

| Isidore (2002) | H3 | 0.69 | 191 | 0.000 | 0/1 | 0.80* |

| Keith (2000) | H4 | 0.64 | 1753 | 0.000 | 696/306 | 1.06* |

| Grace (2021) | H3 | 0.60 | 1170 | 0.000 | 39/139 | 0.97* |

| average | 0.68 |

| Name | Date | Cat | n | p | |||

| Kenna | Oct 25, 2002 | H3 | 0.58 | 329 | 0.000 | 13/61 | 1.20 |

| Winifred | Oct 09, 1992 | H1 | 0.53 | 323 | 0.000 | 7/86 | 1.04 |

| Kiko | Aug 27,1989 | H3 | 0.51 | 177 | 0.000 | 69/125 | 1.28 |

| Jimena | Sep 03, 2009 | H1 | 0.45 | 249 | 0.000 | 93/161 | 1.23 |

| Willa | Oct 23, 2018 | TD | 0.46 | 331 | 0.000 | 84/107 | 1.11 |

| John | Sep 26, 2024 | H1 | 0.70 | 199 | 0.000 | 149/58 | 0.39 |

| Virgil | Oct 02, 1992 | H2 | 0.69 | 200 | 0.000 | 127/75 | 0.59 |

| Odile | Sep 17, 2014 | TS | 0.65 | 179 | 0.000 | 131/123 | 0.54 |

| Pauline | Oct 08, 1997 | TS | 0.30 | 322 | 0.000 | 131/62 | 0.37 |

| Otis | Oct 25, 2023 | H5 | 0.25 | 623 | 0.000 | 345/272 | 0.79 |

| Roslyn | Oct 22, 2022 | TS | 0.70 | 107 | 0.000 | 31/41 | 0.47* |

| Patricia | Oct 23, 2015 | H5 | 0.62 | 179 | 0.000 | 0/8 | 0.59* |

| Lane | Sep 15, 2006 | TS | 0.60 | 312 | 0.000 | 49/71 | 0.65* |

| John | Sep 01, 2006 | H4 | 0.47 | 178 | 0.000 | 30/47 | 0.62* |

| Lidia | Oct 10, 2023 | H3 | 0.50 | 32 | 0.004 | 4/4 | 0.31* |

| average | 0.53 |

| Name | Date | Cat | n | p | |||

| Keith | Oct 03, 2000 | TS | 0.67 | 229 | 0.000 | 37/46 | 1.34 |

| Dean | Aug 22, 2007 | TD | 0.63 | 867 | 0.000 | 0/131 | 1.02 |

| Gilbert | Sep 16, 1988 | H4 | 0.57 | 3.44 | 0.000 | 0/140 | 1.01 |

| Emily | Jul 21, 2005 | TS | 0.51 | 840 | 0.000 | 196/234 | 1.78 |

| Roxanne | Oct 20, 1995 | TD | 0.61 | 594 | 0.000 | 295/225 | 0.75 |

| Wilma | Oct 21, 2005 | H4 | 0.54 | 147 | 0.000 | 53/10 | 0.39 |

| Isidore | Sep 23, 2002 | TS | 0.44 | 194 | 0.000 | 0/14 | 0.65* |

| Grace | Aug 20, 2021 | H1 | 0.42 | 316 | 0.000 | 64/122 | 0.31* |

| average | 0.55 |

| Name | Date | Cat | n | P | |||

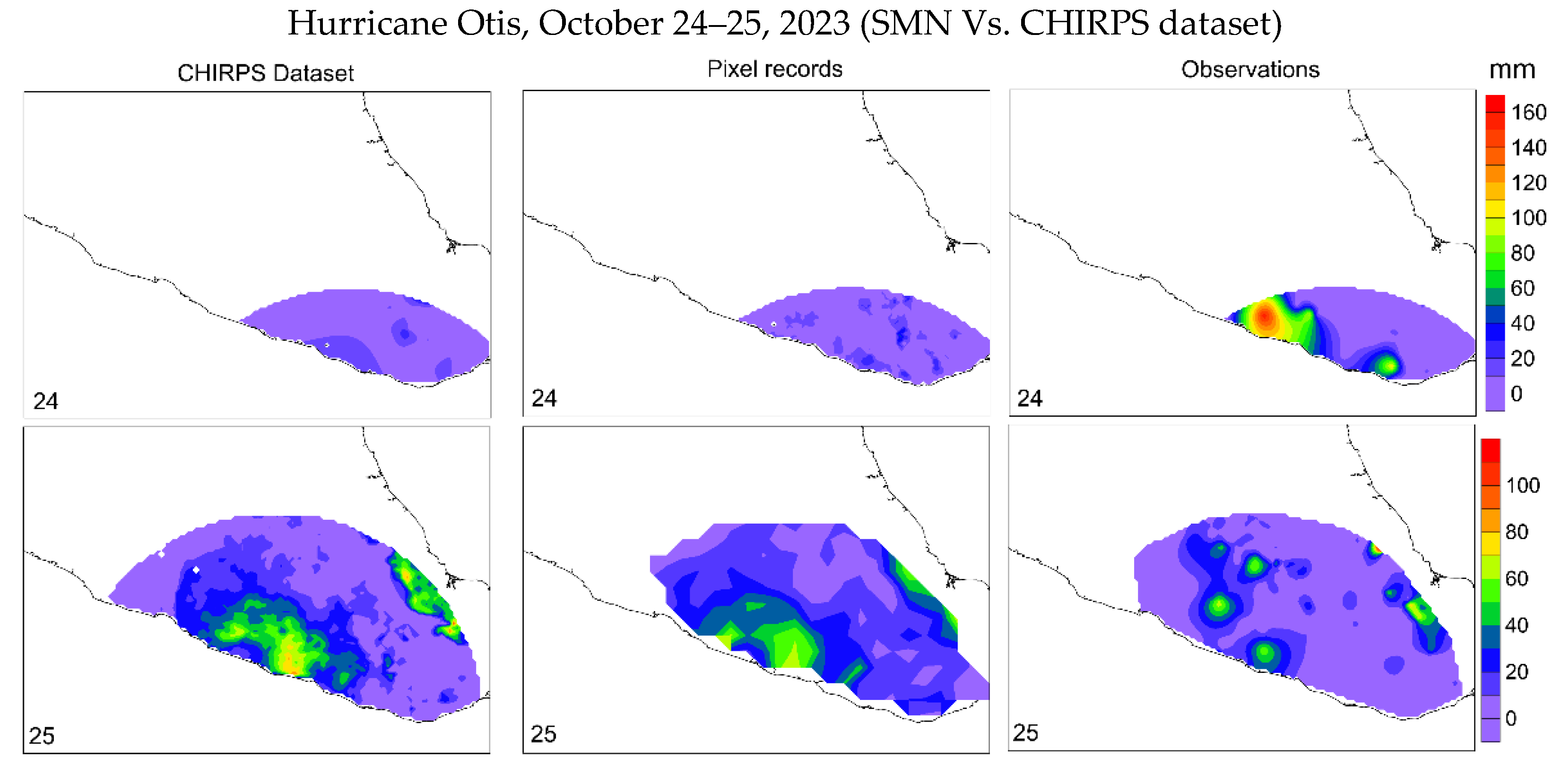

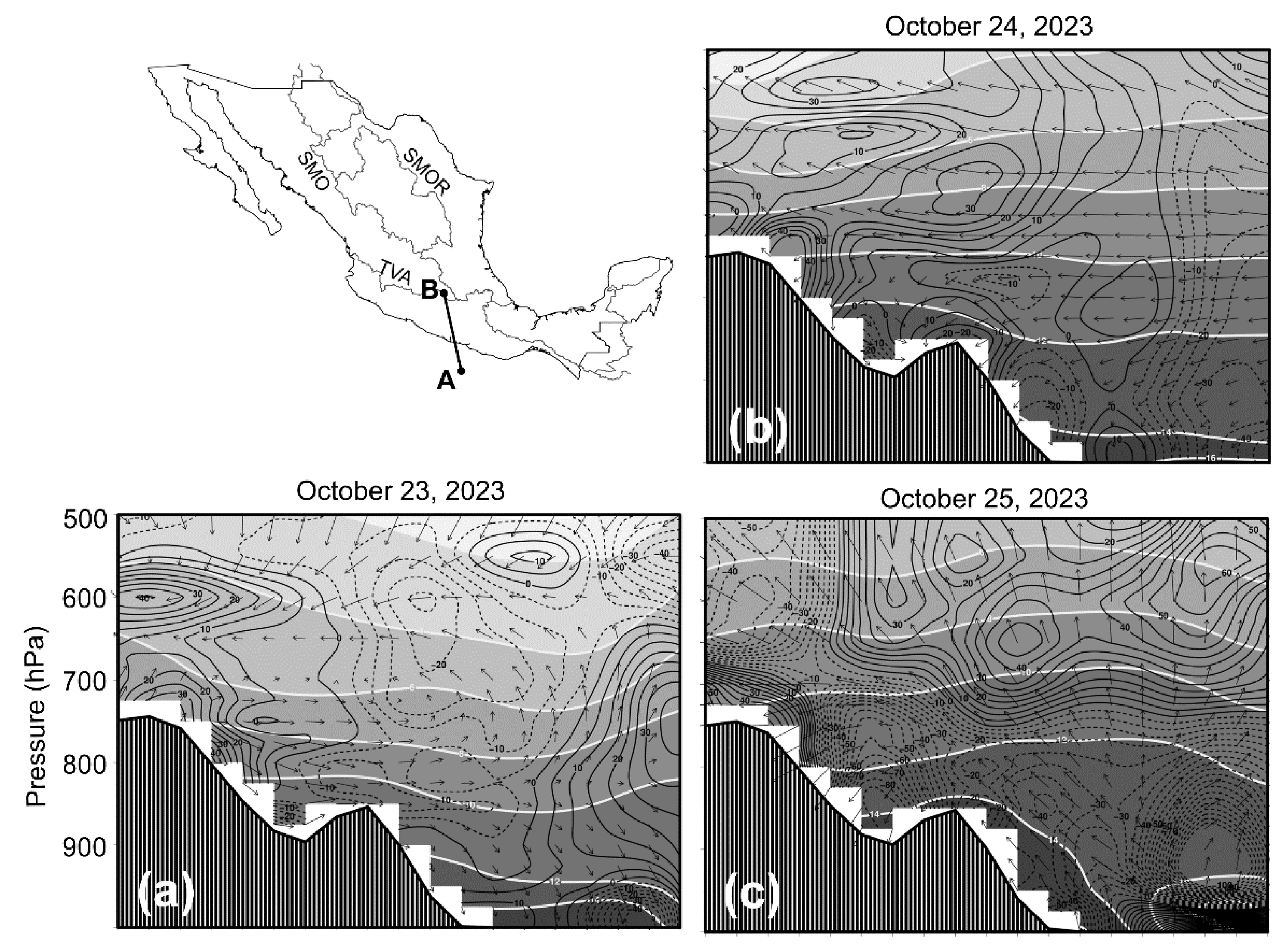

| Otis | Oct 24, 2023 | H1 | 0.14 | 51 | 0.320 | 25/28 | 0.12 |

| Otis | Oct 25, 2024 | H2 | 0.31 | 487 | 0.000 | 209/106 | 1.12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).