1. Introduction

Rubrene (5,6,11,12-tetraphenyltetracene) holds a legendary status in materials science due to its exceptional charge carrier mobility in single crystals [

1,

2,

3]. However, despite its prominence and a history dating back to its first isolation by Moureu and Dufraisse in 1926 [

4], the synthetic chemistry of rubrene has not kept pace with the interest in its physical properties. The structure of rubrene was initially misassigned before being correctly identified as a tetracene derivative by Dufraisse and Velluz [

5]. As highlighted in a recent review by Douglas and co-workers [

6], synthetic approaches to rubrene and its derivatives have remained surprisingly limited. Multi-step approaches, including Diels–Alder cycloadditions [

7] and cross-coupling reactions with pre-formed tetracene cores [

8], offer greater control but often involve lengthy sequences with specific limitations [

6]. The most direct method remains the classical one-pot synthesis involving dimerization of a 1,1,3-triaryl-3-chloroallene intermediate generated from the corresponding propargyl alcohol [

4,

6]. While valued for its simplicity, this “rubrenic synthesis” is complicated by a competing pathway that leads to bis(alkylidene)cyclobutene by-products, a common impurity in commercial rubrene [

9]. The mechanistic picture, refined by Rigaudy and Capdevielle [

10], suggests a delicate equilibrium between the tetracene and cyclobutene frameworks. According to a pivotal study by Braga, the reaction outcome correlates with the electronic nature of the substituents on the chloroallene, such that strong electron-donating groups (e.g., diethylamino) favored the cyclobutene, whereas electron-withdrawing or neutral substituents afforded the desired tetracene framework [

9].

Despite the development of modern methods, this classical pathway remains highly relevant for the straightforward preparation of symmetrical rubrene derivatives [

6,

11], driven by the need to tailor rubrene properties for applications in organic electronics and as an annihilator in triplet-triplet annihilation upconversion (TTA-UC) [

12,

13,

14]. Functionalization of the rubrene core, particularly with electron-withdrawing groups (EWGs), is a recognized strategy to modulate its electronic structure and suppress detrimental processes like singlet fission [

14,

15]. While, for instance, nitro- or cyano-substituted rubrene derivatives have been synthesized via the 3-chloroallene route [

11], this work focused exclusively on the tetracene product and did not report the formation of the cyclobutene byproduct, implying high selectivity. However, the behavior of moderate EWGs, such as esters, on the critical 3-chloroallene dimerization step remains underexplored.

Herein, we report the synthesis and comprehensive characterization of novel symmetrically disubstituted rubrene derivative bearing methoxycarbonyl groups at the para-positions of its 5- and 11-phenyl moieties.

2. Results and Discussion

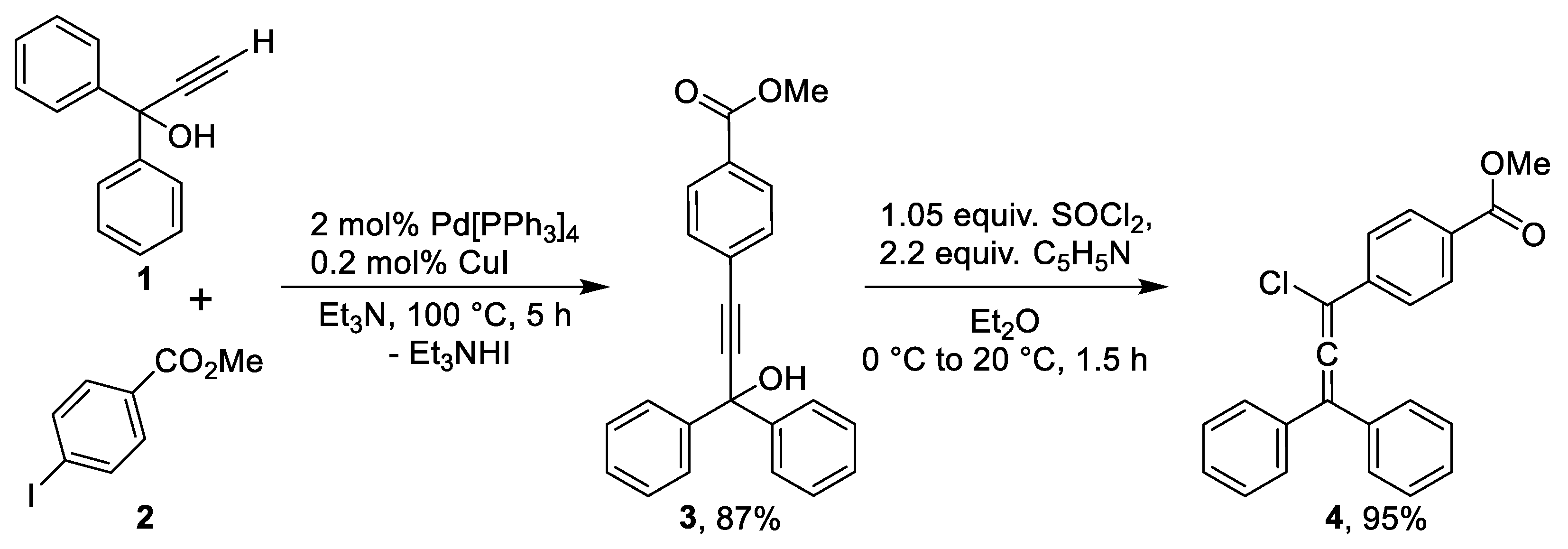

Our synthetic approach to the target methoxycarbonyl-substituted rubrene is outlined in

Scheme 1. The synthesis commenced with a Sonogashira cross-coupling between commercially available 1,1-diphenylprop-2-yn-1-ol (

1) and methyl 4-iodobenzoate (

2) using a catalytic system of Pd(PPh

3)

4 and CuI in a solution of triethylamine, the reaction proceeded smoothly to afford the propargyl alcohol

3 in 87% yield. Subsequent treatment of alcohol

3 with thionyl chloride in the presence of pyridine in dry Et

2O gave 3-chloroallene

4, which was isolated in 95% yield. It should be noted that the resulting 3-chloroallene turned out to be quite stable at room temperature and was even characterized by NMR spectroscopy and HRMS. This is evidence of the stabilization of its molecule due to the presence of the electron-withdrawing methoxycarbonyl group in the phenyl moiety at C-3 atom of allene structure.

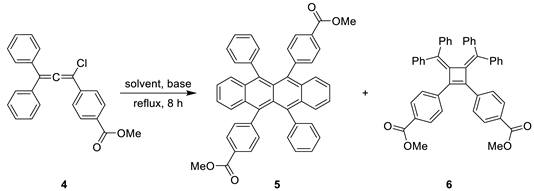

The critical thermal dimerization of 3-chloroallene 4 was then investigated. This reaction is known to proceed via a complex mechanism that can lead to two desired rubrene derivative 5 and a bis(alkylidene)cyclobutene by-product

6 [

9,

10]. We examined this transformation under various conditions. When the reaction was conducted in p-xylene with collidine as a base under reflux (

Table 1, entry 1), the desired rubrene derivative 5 was obtained in a mere 3% yield after work-up and purification, while the cyclobutene 6 was isolated in 28% yield. Omitting the base and switching to chlorobenzene under reflux (

Table 1, entry 2) led to a marked improvement for the tetracene, yielding rubrene

5 in 23%, with the yield of cyclobutene

6 being 25%. The best result for the target compound was achieved under reflux in

o-dichlorobenzene without base (

Table 1, entry 3), affording compound

5 in 25% isolated yield; cyclobutene

6 was also obtained in 25% yield. A striking and consistent feature across all experiments was the formation of substantial amounts of by-product

6, which was separated from the target rubrene by crystallization from acetone. Thus, all our attempts to improve selectivity toward the tetracene product resulted in comparable formation of rubrene

5 and cyclobutene

6, indicating that the methoxycarbonyl substituent does not notably affect the competition between the two reaction pathways under the investigated conditions.

The

1H NMR spectrum of rubrene

5 was in full agreement with the proposed highly symmetric tetracene framework (see

Supplementary Materials to obtain the copies of

1H and

13C NMR spectra of this compound). It showed the characteristic doublet for the ortho-protons of the methoxycarbonyl-substituted phenyl rings at 7.68 ppm with a coupling constant 8.1 Hz, and the sharp singlet for the methoxy groups at 3.91 ppm. The remaining 22 aromatic protons were observed as a series of complex multiplets between 7.28 and 6.83 ppm. In contrast, the spectrum of the cyclobutene

6 showed a clearly distinct and more complex aromatic region, including characteristic doublets at 7.44 and 6.60 ppm. Crucially, its methoxy groups resonated as a sharp singlet at a different 3.78 ppm, unequivocally differentiating it from compound

5.

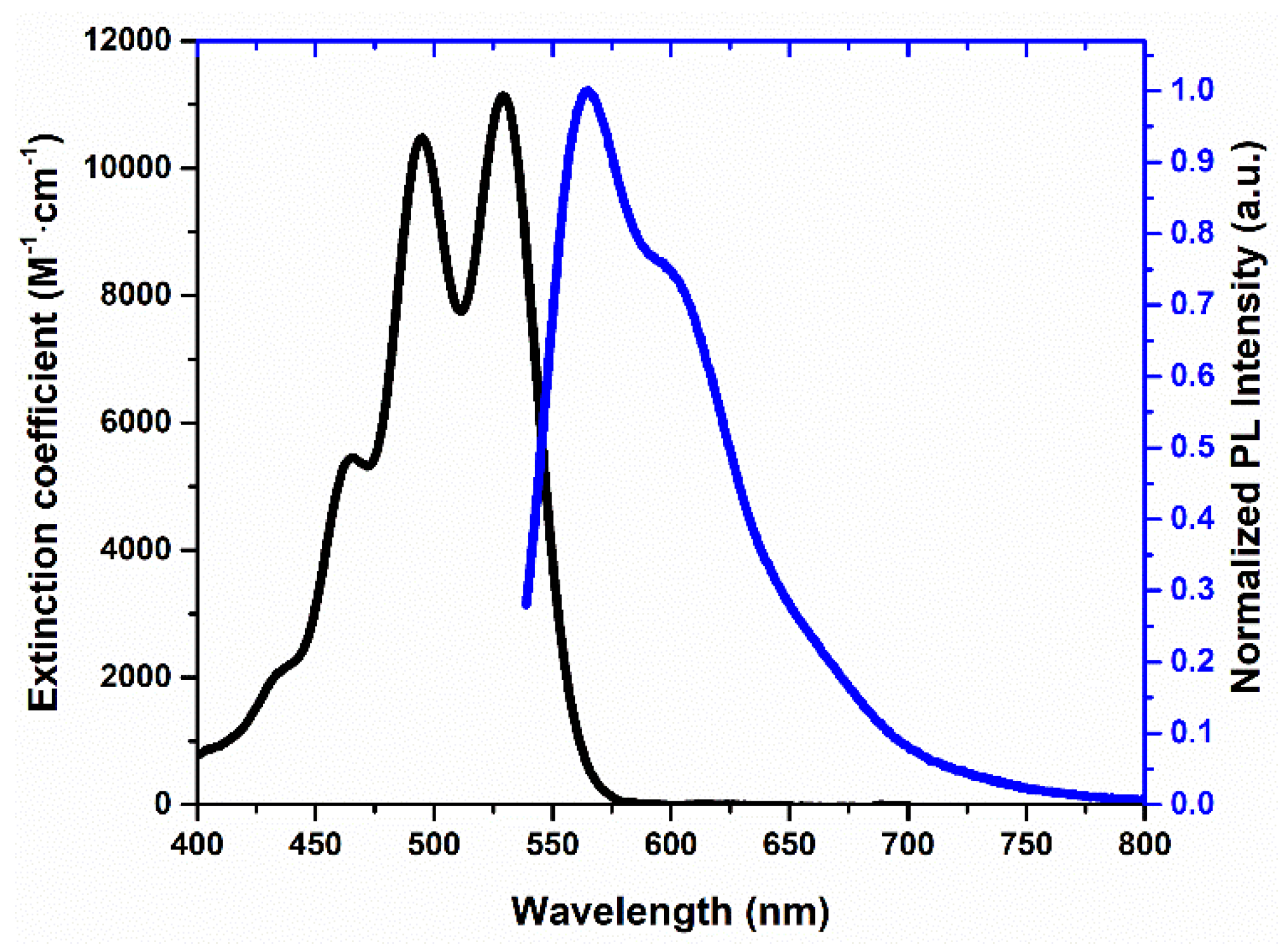

The optical characteristics of newly rubrene derivative

5 were examined in a CHCl

3 solution and in the solid state (

Table 2). In solution, compound

5 exhibits well-defined vibronic absorption bands with a dominant maximum at 529 nm, typical for tetracene-based chromophores with extended conjugation, and emits at 565 nm with a moderate Stokes shift, indicative of limited excited-state relaxation. The high fluorescence quantum yield of 0.81 and the long excited-state lifetime of 11.41 ns confirm efficient radiative deactivation and a relatively low non-radiative decay rate, showing that the moderately electron-withdrawing methoxycarbonyl substituents preserve the emissive character of the tetracene core. A comparison with cyano-functionalized rubrene

2CN-rub[

15] reveals a clear structure–property contrast: while both substituent types reduce electron density, the strong acceptor CN group significantly enhances non-radiative decay and leads to a considerable loss of emission efficiency in solution (Φ = 0.56 reported for

2CN-Rub). This difference suggests that derivative

5 maintains a more favorable balance between radiative and non-radiative processes. Although triplet–triplet annihilation behavior was not yet explored for compound

5, its moderate acceptor strength may lead to a distinct influence on triplet energy levels and annihilation pathways compared to strongly electron-deficient CN analogs, which were shown to increase the statistical probability of singlet formation via TTA in solid-state photonic applications [

15].

In the solid state, compound 5 demonstrates a markedly different behavior. Both absorption and emission spectra undergo pronounced bathochromic shifts (547 and 618 nm, respectively), consistent with strong π–π interactions in the aggregated phase. However, this packing causes severe aggregation-induced quenching: the quantum yield sharply drops to 0.01 and the lifetime decreases to 2.17 ns, indicating highly efficient non-radiative decay triggered by exciton coupling. This result stands in strong contrast to cyano-functionalized rubrenes, which can retain solid-state emission by imposing more favorable packing motifs and suppressing exciton-loss processes. Thus, while the methoxycarbonyl group allows the material to exhibit high photoluminescence efficiency in solution, it does not provide sufficient steric or electronic modulation to prevent exciton quenching in the condensed phase. Overall, the data show that compound 5 is a highly efficient light emitter in solution but becomes limited by aggregation-induced non-radiative decay in the solid state. A deeper study of crystal packing, intermolecular distances, and triplet-state energetics could offer strategies to optimize solid-state emissive performance for materials science applications.

Figure 1.

Absorption (black line) and fluorescence (blue line) spectra of rubrene 5 in a CHCl3 solution.

Figure 1.

Absorption (black line) and fluorescence (blue line) spectra of rubrene 5 in a CHCl3 solution.

3. Materials and Methods

1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on Bruker AVANCE-500 (500 MHz) (Bruker BioSpin, Germany), in CDCl3 with SiMe4 as an internal standard. High-resolution mass spectra were obtained on a Bruker maXis Impact HD spectrom-eter (Bruker BioSpin, Germany). Unless otherwise stated, all reagents were purchased from commercial sources and used without further purification. Melting points were determined on combined heating stages and are uncorrected.

Synthesis of methyl 4-(3-hydroxy-3,3-diphenylprop-1-yn-1-yl)benzoate (3). A mixture of 1,1-diphenylprop-2-yn-1-ol (1, 1.05 g, 5.05 mmol), methyl 4-iodobenzoate (2, 1.31 g, 5.0 mmol), CuI (30 mg, 0.16 mmol), and Pd(PPh3)4 (150 mg, 0.125 mmol) in triethylamine (22 mL) was placed in a 50 mL Schlenk tube equipped with a reflux condenser. The mixture was deoxygenated by four cycles of vacuum/argon flushing, then stirred and heated at reflux under argon for 6 h. After cooling, diethyl ether (30 mL) was added, and the mixture was filtered through a short pad of silica gel (approx. 4 x 1 cm), eluting with additional ether. The filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure, and the residue was crystallized from isopropanol to afford 3 as a beige powder.

Yield: 1.49 g (87%); m.p. 140–141 °C. ¹H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.00 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.69 – 7.63 (m, 4H), 7.57 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.36 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 4H), 7.30 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 3.92 (s, 3H), 2.96 (s, 1H). ¹³C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 166.6, 144.8, 131.9, 130.1, 129.6, 128.5, 128.0, 127.2, 126.2, 94.8, 86.5, 75.0, 52.4. HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C23H19O3 [M+H]+: 343.1329; found: 343.1329.

Synthesis of methyl 4-(1-chloro-3,3-diphenylprop-1,2-dien-1-yl)benzoate (4). Propargyl alcohol 3 (2.05 g, 6.00 mmol) was dissolved in dry diethyl ether (75 mL) and cooled in an ice bath. Dry pyridine (1.20 mL, 14.9 mmol) was added, followed by dropwise addition of freshly distilled thionyl chloride (0.60 mL, 8.3 mmol). The mixture was stirred for 1 h at ambient temperature. The precipitated pyridine hydrochloride was removed by filtration and washed with hexane (2 × 5 mL). The combined organic filtrates were washed with 6 M aqueous HCl (40 mL), followed by water (2 × 15 mL). The organic layer was dried over anhydrous CaCl2, filtered through a small silica gel pad, and concentrated under reduced pressure. The product was obtained as a gray powder, pure by NMR analysis, and was used in the next step without further purification.

Yield: 2.057 g (95%); m.p. 121–122 °C. ¹H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl₃) δ 8.05 – 8.02 (m, 2H), 7.74 – 7.69 (m, 2H), 7.47 – 7.35 (m, 10H), 3.92 (s, 3H). ¹³C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl₃) δ 166.7, 138.2, 134.8, 130.0, 130.0, 129.2, 129.0, 128.9, 126.3, 120.1, 107.4, 52.3. HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C23H18ClO2 [M+H]+: 361.0990; found: 361.0990.

Procedure for the thermal dimerization of 3-сhloroallene 4 to give rubrene 5 and cyclobutene 6. 3-Chloroallene 4 (1.80 g, 5.00 mmol) was dissolved in o-dichlorobenzene (30 mL). The solution was heated at reflux for 8 h and then left to stand overnight at room temperature. The solvent was removed by evaporation under reduced pressure. The resulting crude residue was dissolved in benzene (10 mL), and acetone (50 mL) was added. The volume of a solution was reduced to approximately 30 mL by evaporation on air in a fume hood with gentle heating. The mixture was then stand at ambient temperature for 10 min, and the precipitated rubrene 5 was collected by filtration, washed with cold acetone (10 mL) and dried at 120 °C. The mother liquor was concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting solid residue was dissolved in toluene (5 mL), and methanol (15 mL) was added to precipitate cyclobutene 6, which was collected by filtration. If necessary, the products were further purified by recrystallization from acetone (for 5) or a toluene/methanol mixture (for 6) to afford analytically pure samples.

Dimethyl 4,4’-(5,6,11,12-tetraphenyltetracene-5,11-diyl)dibenzoate (5). Isolated as reddish microcrystals.

Reddish crystals, yield 0.405 g (25%), m.p. 301–302 °C. ¹H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl₃) δ 7.74 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 4H), 7.39 – 7.33 (m, 2H), 7.28 – 7.23 (m, 2H), 7.17 – 7.08 (m, 6H), 7.06 – 7.01 (m, 4H), 6.96 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 4H), 6.87 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 4H), 3.98 (s, 6H). ¹³C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl₃) δ 167.4, 147.1, 141.5, 137.5, 136.1, 132.5, 132.3, 130.5, 130.1, 128.9, 128.6, 127.6, 127.5, 126.8, 126.5, 126.2, 125.6, 125.3, 52.2. HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C46H33O4 [M+H]+: 649.2373; found: 649.2373.

Dimethyl 4,4’-(3,4-bis(diphenylmethylene)cyclobut-1-ene-1,2-diyl)dibenzoate (6).

Yellowish needles, yield 0.408 g (25%), m.p. 238–239 °C. m.p. 238–239 °C. ¹H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.52 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 4H), 7.08 – 6.90 (m, 14H), 6.86 – 6.81 (m, 2H), 6.77 – 6.72 (m, 4H), 6.58 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 4H), 3.85 (s, 6H). ¹³C NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3) δ 167.0, 154.3, 141.4, 140.8, 139.6, 137.4, 131.8, 131.7, 131.5, 128.5, 128.1, 127.9, 127.6, 127.4, 127.3, 127.2, 52.1. HRMS (ESI) m/z calcd for C46H35O4 [M+H]+: 651.2530; found: 651.2530.