Submitted:

11 December 2025

Posted:

12 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- How do executive function, instrumental activities of daily living, and quality of life interrelate in a community-dwelling sample of older adults, adding depressive symptoms as a covariate in a structural model of interrelation pathways?

2. Materials and Methods

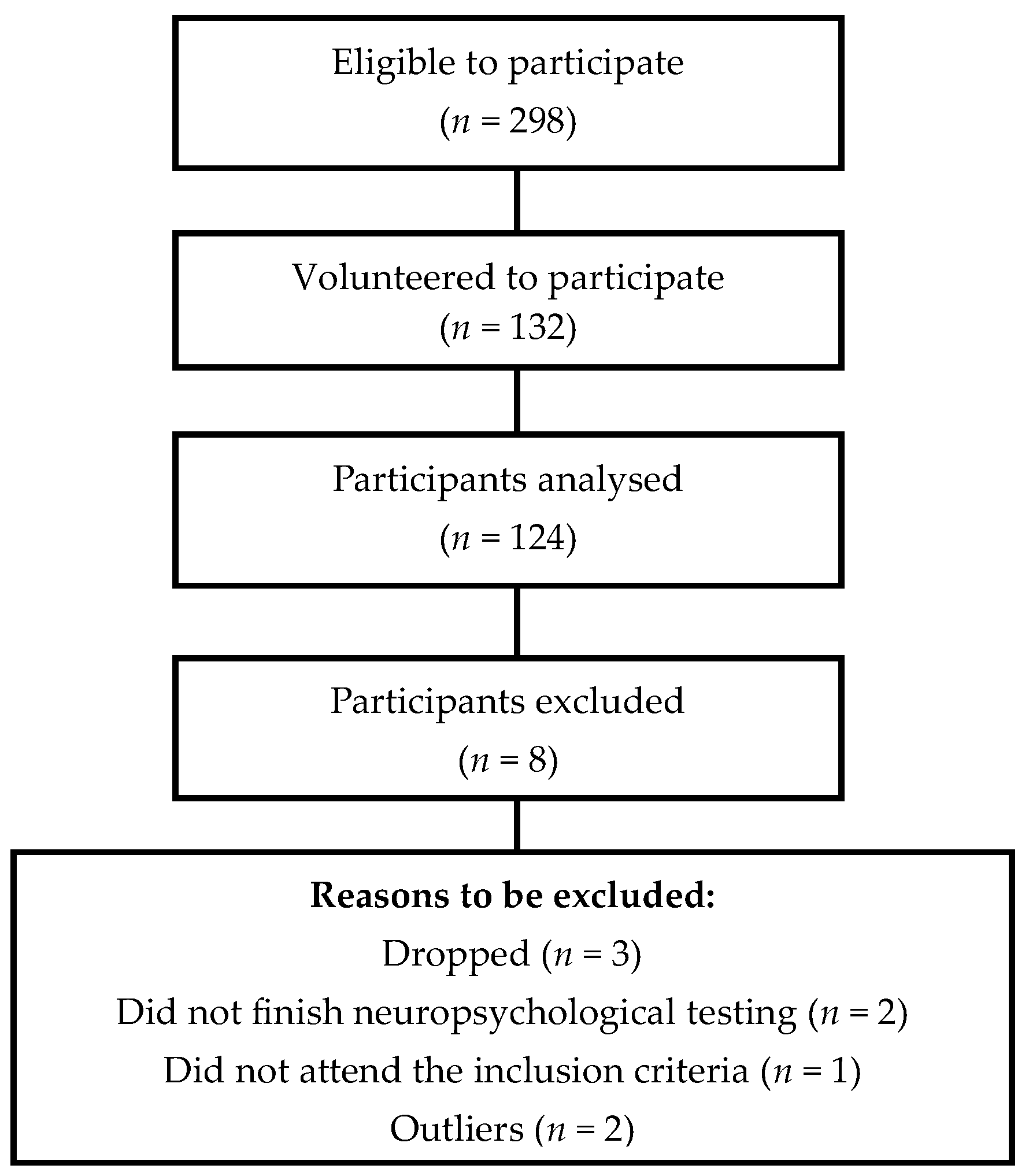

2.1. Participants

2.2. Instruments

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

3.2. Preliminary Analysis

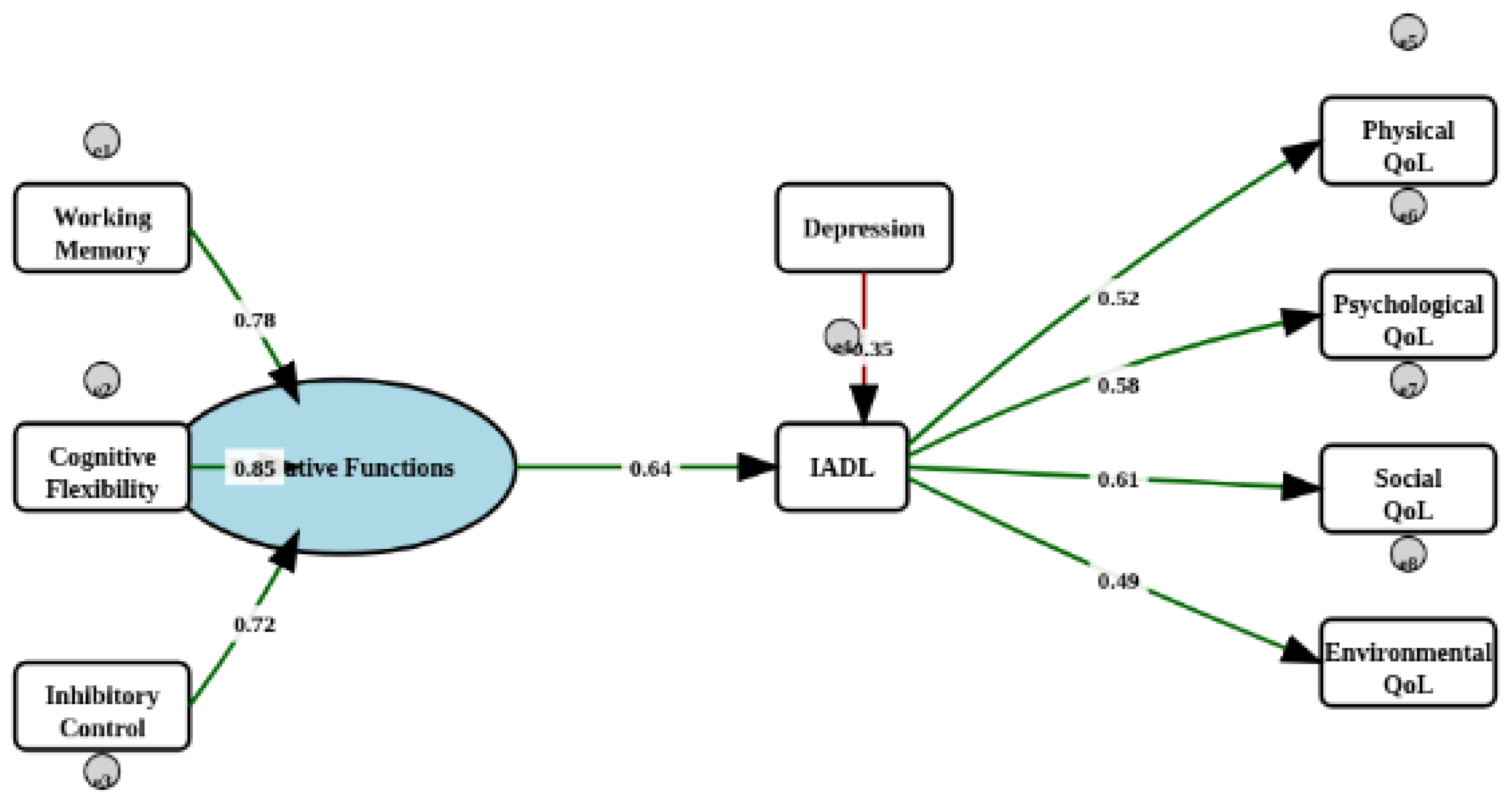

3.3. Structural Analysis

| Path | B | SE | β | 95% CI LL | 95% CI UL | p |

| EF → physical QoL | 0.426 | 0.515 | 0.075 | -0.582 | 1.435 | 0.407 |

| IADL → physical QoL | -0.124 | 0.084 | -0.190 | -0.288 | 0.040 | 0.139 |

| depression → physical QoL | -0.340 | 0.085 | -0.335 | -0.506 | -0.174 | < .001 |

| EF → psychological QOL | 0.331 | 0.461 | 0.058 | -0.572 | 1.233 | 0.473 |

| IADL → psychological QOL | -0.038 | 0.097 | -0.058 | -0.228 | 0.153 | 0.699 |

| depression → psychological QOL | -0.342 | 0.095 | -0.340 | -0.528 | -0.156 | < .001 |

| EF → social QoL | -0.269 | 0.535 | -0.035 | -1.317 | 0.779 | 0.615 |

| IADL → social QoL | 0.068 | 0.054 | 0.077 | -0.039 | 0.174 | 0.212 |

| depression → social QoL | -0.366 | 0.125 | -0.268 | -0.610 | -0.122 | 0.003 |

| EF → environmental QoL | 0.607 | 0.435 | 0.095 | -0.246 | 1.460 | 0.163 |

| IADL → environmental QoL | -0.012 | 0.037 | -0.017 | -0.085 | 0.060 | 0.740 |

| depression → environmental QoL | -0.491 | 0.075 | -0.431 | -0.638 | -0.344 | < .001 |

| FE → IADL | -1.840 | 0.964 | -0.210 | -3.729 | 0.049 | 0.056 |

| depression → IADL | 0.268 | 0.133 | 0.172 | 0.006 | 0.529 | 0.045 |

| depression → EF | -0.012 | 0.019 | -0.070 | -0.050 | 0.025 | 0.513 |

| Variable | R² | % Variance Explained |

| WM | 0.058 | 5.8% |

| Flx | 0.674 | 67.4% |

| IC | 0.795 | 79.5% |

| physical QoL | 0.188 | 18.8% |

| psychological QoL | 0.134 | 13.4% |

| social QoL | 0.071 | 7.1% |

| envoirnment QoL | 0.204 | 20.4% |

| IADL | 0.079 | 7.9% |

| EF | 0.005 | 0.5% |

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| NESMEP | Center of Studies in Mental Health, Education and Psychometrics |

| UFPB | Federal University of Paraíba |

| QoL | Quality of Life |

| EF | Executive Function |

| IADL | Instrumental Activities of Daily Living |

| ConVExA | Contextually Valid Executive Assessment |

| SEM | Structural Equation Modeling |

| SD | Standard Deviation |

| MCI | Mild Cognitive Impairment |

| n | Number of participants |

| IBGE | Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics |

| GDS-15 | 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale |

| PFAQ | Pfeffer’s Functional Activities Questionnaire |

| WHOQOL-BREF | World Health Organization Quality of Live abbreviated version |

| FDT | Five-Digit Test |

| WAIS-III | Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale, third version |

| p | p-value |

| χ² | Chi-square |

| R² | R-squared (proportion of variance explained) |

| df | Degrees of freedom |

| CFI | Comparative Fit Index |

| TLI | Tucker-Lewis Index |

| RMSEA | Root Mean Square Error of Approximation |

| SRMR | Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

| GenAI | Generative Artificial Intelligence |

| M | Mean |

| r | Correlation coefficent |

| WM | Working memory |

| CF | Cognitive flexibility |

| IC | Inhibitory control |

| B or β | Standardized coefficient |

| SE | Standard Error |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| AVE | Average Variance Extracted |

| AIC | Akaike Information Criterion |

| BIC | Bayesian Information Criterion |

| LL | Lower Limit |

| UL | Upper Limit |

References

- Livingston, G.; Huntley, J.; Liu, K.Y.; Costafreda, S.G.; Selbæk, G.; Alladi, S.; Ames, D.; Banerjee, S.; Burns, A.; Brayne, C.; et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care: 2024 report of the Lancet standing Commission. Lancet 2024, 404, 572–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro-Costa, É.; Diniz, B.S.; Blay, S.L. Editorial: Cognitive Impairment and Inflammation in Old Age and the Role of Modifiable Risk Factors of Neurocognitive Disorders. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moraes, E.; Pereira, A.; Azevedo, R.; Moraes, F. Avaliação Multidimensional do Idoso; Secretaria de Estado da Saúde do Paraná: Curitiba, Brazil, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Censo Demográfico 2022: População por Idade e Sexo: Pessoas de 60 Anos ou Mais de Idade: Resultados do Universo: Brasil, Grandes Regiões e Unidades da Federação; IBGE: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Decade of Healthy Ageing: Baseline Report. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240017900 (accessed on 15 October 2024).

- Gattuso, M.; Butti, S.; Benincá, I.L.; Greco, A.; Di Trani, M.; Morganti, F. A Structural Equation Model for Understanding the Relationship between Cognitive Reserve, Autonomy, Depression and Quality of Life in Aging. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2024, 21, 1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleck, M.P.A.; Louzada, S.; Xavier, M.; et al. Application of the Portuguese Version of the WHOQOL-bref Instrument. Revista de Saúde Pública 2000, 34(2), 178–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. The World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL): Position Paper from the World Health Organization. Social Science & Medicine 1995, 41, 1403–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.V.; Baptista, M.N. Quality of Life and Advanced Activities of Daily Living among Older Adults: A Cross-Sectional Study. Braz. J. Dev. 2023, 9(3), 11939–11958. [Google Scholar]

- Souza-Júnior, E.V.; Silva, C.S.; Cruz, D.P.; et al. Sexuality and Depressive Symptomatology in Elderly Residents in Northeastern Brazil. Enfermería Global 2021, 64, 202–214. [Google Scholar]

- Guye, S.; Röcke, C.; Martin, M.; von Bastian, C.C. Functional Ability in Everyday Life: Are Associations With an Engaged Lifestyle Mediated by Working Memory? Journals Gerontol. Ser. B 2019, 75, 1873–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xue, H.; Huang, C.; Zhu, Q.; Zhou, S.; Ji, Y.; Ding, X.; Zhang, D.; Gu, D. Relationships Among Cognitive Function, Frailty, and Health Outcome in Community-Dwelling Older Adults. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022, 13, 790251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raimo, S.; Maggi, G.; Ilardi, C.R.; Cavallo, N.D.; Torchia, V.; Pilgrom, M.A.; Cropano, M.; Roldán-Tapia, M.D.; Santangelo, G. The relation between cognitive functioning and activities of daily living in normal aging, mild cognitive impairment, and dementia: a meta-analysis. Neurol. Sci. 2024, 45, 2427–2443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruderer-Hofstetter, M.; Gorus, E.; Cornelis, E.; Meichtry, A.; De Vriendt, P. Influencing factors on instrumental activities of daily living functioning in people with mild cognitive disorder – a secondary investigation of cross-sectional data. BMC Geriatr. 2022, 22, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velaithan, V.; Tan, M.-M.; Yu, T.-F.; Liem, A.; Teh, P.-L.; Su, T.T. The Association of Self-Perception of Aging and Quality of Life in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Gerontol. 2023, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verga, C.E.R.; dos Santos, G.; Ordonez, T.N.; Moreira, A.P.B.; Costa, L.A.; de Moraes, L.C.; Lessa, P.; Cardoso, N.P.; França, G.D.; Neto, A.F.; et al. Executive functions, mental health, and quality of life in healthy older adults. Dement. Neuropsychol. 2024, 18, e20240156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, O.; Teixeira, L.; Araújo, L.; Rodríguez-Blázquez, C.; Calderón-Larrañaga, A.; Forjaz, M.J. Anxiety, Depression and Quality of Life in Older Adults: Trajectories of Influence across Age. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2020, 17, 9039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchy, Y. Introduction to special issue: Contextually valid assessment of executive functions in the era of personalized medicine. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2020, 34, 613–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchy, Y.; Ziemnik, R.E.; Niermeyer, M.A.; Brothers, S.L. Executive functioning interacts with complexity of daily life in predicting daily medication management among older adults. Clin. Neuropsychol. 2019, 34, 797–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lezak, M.D.; Howieson, D.B.; Loring, D.W.; Fischer, J.S. Neuropsychological Assessment, 5th ed.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Suchy, Y.; Niermeyer, M.A.; Franchow, E.I.; Ziemnik, R.E. Naturally Occurring Expressive Suppression is Associated with Lapses in Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Among Community-Dwelling Older Adults. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2019, 25, 718–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suchy, Y. Executive Functioning: A Comprehensive Guide for Clinical Practice; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Suchy, Y.; Mora, M.G.; DesRuisseaux, L.A.; Brothers, S.L. It’s complicated: Executive functioning moderates impacts of daily busyness on everyday functioning in community-dwelling older adults. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2023, 29, 850–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satler, C.; Faria, E.T.; Rabelo, G.N.; Garcia, A.; Tavares, M.C.H. Inhibitory control training in healthy and highly educated older adults. Dement. Neuropsychol. 2021, 15, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corbo, I.; Troisi, G.; Marselli, G.; Casagrande, M. The role of cognitive flexibility on higher level executive functions in mild cognitive impairment and healthy older adults. BMC Psychol. 2024, 12, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sayed, M.M.; Hawash, M.M.; Khedr, M.A.; Hafez, S.A.; Salem, E.-S.A.E.-H.; Essa, S.A.; Sayyd, S.M.; El-Ashry, A.M. Cognitive flexibility's role in shaping self-perception of aging, body appreciation, and self-efficacy among community-dwelling older women. BMC Nurs. 2024, 23, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, C.; Morgado, B.; Alves, E.; Ramos, A.; Silva, M.R.; Pinho, L.; João, A.; Lopes, M. The Functional Profile, Depressive Symptomatology, and Quality of Life of Older People in the Central Alentejo Region: A Cross-Sectional Study. Healthcare 2024, 12, 2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, M.; Moulder, R.G.; Breitfelder, L.K.; Röcke, C. Daily activity diversity and daily working memory in community-dwelling older adults. Neuropsychology 2023, 37, 181–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yesavage, J.A.; Brink, T.L.; Rose, T.L.; Lum, O.; Huang, V.; Adey, M.; Leirer, V.O. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: A preliminary report. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1983, 17, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, O.P.; Almeida, S.A. Short Versions of the Geriatric Depression Scale: A Study of Their Validity for the Diagnosis of a Major Depressive Episode According to ICD-10 and DSM-IV. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 1999, 14(10), 858–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, R.I.; Kurosaki, T.T.; Harrah, C.H.; Chance, J.M.; Filos, S. Measurement of Functional Activities in Older Adults in the Community. J. Gerontol. 1982, 37, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sanchez, M.A.d.S.; Correa, P.C.R.; Lourenço, R.A. Cross-cultural Adaptation of the "Functional Activities Questionnaire - FAQ" for use in Brazil. Dement. Neuropsychol. 2011, 5, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The Whoqol Group. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF Quality of Life Assessment. Psychol. Med. 1998, 28, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleck, M.P.A.; Louzada, S.; Xavier, M.; Chachamovich, E.; Vieira, G.; Santos, L.; Pinzon, V. Aplicação da versão em português do instrumento abreviado de avaliação da qualidade de vida “WHOQOL-bref”. Rev. Saúde Pública 2000, 34(2), 178–183. Available online: https://www.fsp.usp.br/rsp. [CrossRef]

- Sedó, M.; de Paula, J.J.; Malloy-Diniz, L.F. O Teste dos Cinco Dígitos; Hogrefe, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- De Paula, J.J.; Oliveira, T.D.; Querino, E.H.G.; Malloy-Diniz, L.F. The Five Digits Test in the assessment of older adults with low formal education: construct validity and reliability in a Brazilian clinical sample. Trends Psychiatry Psychother. 2017, 39, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, E. Validação e adaptação do teste WAIS-III para um contexto brasileiro. Tese de Doutorado, Universidade de Brasília, Brasília, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Nascimento, E.D.; de Figueiredo, V.L.M. WISC-III e WAIS-III: alterações nas versões originais americanas decorrentes das adaptações para uso no Brasil. Psicol. E Crit. 2002, 15, 603–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suchy, Y.; Brothers, S.L. Reliability and validity of composite scores from the timed subtests of the D-KEFS battery. Psychol. Assess. 2022, 34, 483–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kline, R.B. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H. Structural Equation Modeling. In Models and Methods for Management Science; Zhang, H., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 199–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthropic. Claude (Claude 3 Opus version) [Large language model]. 2025. Available online: https://claude.ai/ (accessed on 16 July 2025).

- Salthouse, T.A. The aging of working memory. Neuropsychology 1994, 8, 535–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salthouse, T.A. Trajectories of normal cognitive aging. Psychol. Aging 2019, 34, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y.; Park, Y.-H. Structural equation model of the relationship between functional ability, mental health, and quality of life in older adults living alone. PLOS ONE 2022, 17, e0269003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huijun, L.; Xiange, Z.; Ming, Y.; Jiayi, S.; Juanjuan, P.; Wangquan, X.; Yueli, S.; Guixia, F. The mediating role of daily living ability and sleep in depression and cognitive function based on a structural equation model. BMC Geriatr. 2025, 25, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Wang, C. The Relationships Among Structural Social Support, Functional Social Support, and Loneliness in Older Adults: Analysis of Regional Differences Based on a Multigroup Structural Equation Model. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muhammad, T.; Kumar, P.; Srivastava, S. How socioeconomic status, social capital and functional independence are associated with subjective wellbeing among older Indian adults? A structural equation modeling analysis. BMC Public Heal. 2022, 22, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Navarra, G.A.; Tabacchi, G.; Scardina, A.; Agnese, M.; Thomas, E.; Bianco, A.; Palma, A.; Bellafiore, M. Functional fitness, lifestyle and demographic factors as predictors of perceived physical and mental health in older adults: A structural equation model. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0290258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, N.G.N.; Bolina, A.F.; Haas, V.J.; Tavares, D.M.d.S. Exploring the effect of the structural model of active aging on the self-assessment of quality of life among older people: A cross-sectional and analytical study. Sao Paulo Med J. 2024, 142, e2022609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, P.K.H.; Wong, E.L.Y.; Yeung, N.C.Y.; Wong, S.Y.S.; Chung, R.Y.; Tong, A.C.Y.; Ko, C.C.Y.; Li, J.; Yeoh, E.-K. Differential associations among social support, health promoting behaviors, health-related quality of life and subjective well-being in older and younger persons: a structural equation modelling approach. Heal. Qual. Life Outcomes 2022, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de León, L.P.; Mangin, J.P.L.; Ballesteros, S. Psychosocial Determinants of Quality of Life and Active Aging. A Structural Equation Model. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2020, 17, 6023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benincá, I.L.; Gattuso, M.; Butti, S.; Caccia, D.; Morganti, F. Emotional Status, Motor Dysfunction, and Cognitive Functioning as Predictors of Quality of Life in Physically Engaged Community-Dwelling Older Adults: A Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2024, 21, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dantas, B.A.d.S.; Cavalcante, A.C.V.; de Miranda, J.M.A.; Toscano, G.A.d.S.; Nobre, T.T.X.; Mendes, F.R.P.; de Miranda, F.A.N.; Maia, E.M.C.; Torres, G.d.V. Depression and quality of life in Brazilian and Portuguese older people communities. Medicine 2021, 100, e27830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, J.O.; Pontes, D.; Peixoto, B.; Dores, A.R.; Barbosa, F. Ecological validity of neuropsychological interventions: A systematic review. Appl. Neuropsychol. Adult 2024, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suchy, Y.; DesRuisseaux, L.A.; Mora, M.G.; Brothers, S.L.; Niermeyer, M.A. Conceptualization of the term “ecological validity” in neuropsychological research on executive function assessment: a systematic review and call to action. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2024, 30, 499–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Item | Mean (SD) | n (%) |

| Age | 69.16 (7.32) | |

| Education (years) | 9.67 (5.24) | |

| Marital Status | ||

| Married | 53 (42.7) | |

| Divorced | 27 (21.8) | |

| Widowed | 24 (19.4) | |

| Single | 18 (14.5) | |

| Stable Union | 2 (1.6) | |

| Income | ||

| 1 minimum wage | 56 (45.2) | |

| 3 to 5 minimum wages | 30 (24.2) | |

| Up to 2 minimum wages | 19 (15.3) | |

| 6 to 10 minimum wages | 14 (11.3) | |

| More than 10 minimum wages | 5 (4.0) | |

| Reported Diseases in the Past 2 Years (2023-2025) | ||

| High/low blood pressure (hypertension) | 95 (76.61) | |

| Arthritis, arthrosis, rheumatism or other musculoskeletal diseases | 49 (39.52) | |

| Anxiety | 38 (30.65) | |

| Diabetes | 36 (29.03) | |

| Chronic sleep problems | 29 (23.39) | |

| COVID-19 | 27 (21.77) | |

| Depression | 20 (16.13) | |

| Recurrent stomach problems, diarrhea | 17 (13.71) | |

| Migraine | 15 (12.10) | |

| Hearing impairment | 12 (9.68) | |

| Fibromyalgia | 8 (6.45) | |

| High fever | 8 (6.45) |

| Variable | M | SD | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| (1) WM (2) CF (3) IC |

3.99 | 1.75 | — | |||||||||

| 46.40 | 35.27 | -0.21* | — | |||||||||

| 36.17 | 38.28 | -0.20* | 0.73*** | — | ||||||||

| (4) Physical (5) Social |

14.07 | 2.41 | 0.06 | -0.08 | -0.14 | — | ||||||

| 15.20 | 3.25 | 0.09 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.38*** | — | ||||||

| (6) Environment (7) Psychological (8) IADL (9) Depression |

14.36 | 2.70 | 0.20* | -0.07 | -0.13 | 0.38*** | 0.61*** | — | ||||

| 14.68 | 2.39 | 0.11 | -0.01 | -0.12 | 0.35*** | 0.31*** | 0.52*** | — | ||||

| 1.72 | 3.70 | -0.19* | 0.19* | 0.19* | -0.27** | 0.04 | -0.12 | -0.13 | — | |||

| 2.73 | 2.37 | -0.07 | 0.04 | 0.07 | -0.38*** | -0.25** | -0.44*** | -0.35*** | 0.19* — | |||

| Latent Variable | Indicator | B | SE | β | p |

|

Executive Functions (EF) |

|||||

| Working Memory (MT) | 1.000 | 0.000 | 0.241 | — | |

| Cognitive Flexibility (Flx) | -68.594 | 37.859 | -0.821 | 0.070 | |

| Inhibitory Control (CI) | -80.853 | 40.163 | -0.892 | 0.044 |

| Index | Value | Criterion |

| Chi-square (χ²) | 10.035 | — |

| Degrees of freedom (df) | 12 | — |

| p-value | 0.613 | > .05 |

| Comparative Fit Index (CFI) | 1.000 | ≥ .90 |

| Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) | 0.000 | ≤ .08 |

| Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) | 0.041 | ≤ .08 |

| Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) | 5806.51 | Lower |

| Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) | 5896.76 | Lower |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).