1. Introduction

1.1. Historical Context and Current Challenges

For centuries, protein crystallization was regarded as an empirical "art." Early triumphs, such as Funke’s description of hemoglobin crystals in the 19th century, J.B. Sumner's crystallization of urease in 1926, and J.C. Kendrew's determination of myoglobin's structure in the 1950s, targeted naturally abundant and stable proteins [

1]. However, modern biology demands structures of challenging targets, including membrane proteins, low-abundance transcription factors, intrinsically flexible signaling proteins, and massive supramolecular complexes, exposing the limits of conventional empirical screening approaches.

Although high-throughput crystallization robotics now allow researchers to screen thousands of nanoliter-scale conditions, overall success rates have largely plateaued. This is because crystallization is not a random precipitation phenomenon but an ordered assembly process governed by specific, anisotropic interactions between molecules [

2]. Packing within a crystal lattice is highly selective, and even small differences in surface physicochemical properties can determine success or failure. Therefore, blindly expanding the number of screening conditions ultimately faces diminishing returns and does not provide a fundamental solution.

1.2. Physicochemical Basis of Crystallization

Crystallization success hinges on two crucial factors: the presence of "sticky patches" on the protein surface and "conformational homogeneity" in the sample solution [

2]. Sticky patches are surface regions capable of forming specific and reversible intermolecular interactions, such as hydrogen bonds, salt bridges, or hydrophobic interactions.

From the perspective of soft matter physics, protein crystal nucleation is often proposed to follow the two-step nucleation mechanism [

3,

4]. In this model, crystallization proceeds via the following steps: 1) formation of metastable dense liquid clusters: The protein solution first forms metastable, condensed droplets of high solute concentration (dense liquid clusters), driven by short-range attractive interactions between proteins. This liquid-like cluster provides an environment with the necessary high supersaturation for crystal nucleation. 2) appearance of the crystalline nucleus: within this dense cluster, a crystal nucleus with a periodic, ordered structure emerges from conformational fluctuations.

To control this process, the protein surface’s physicochemical properties must be rationally modified to introduce directional interactions that favor the formation of an ordered lattice over amorphous aggregation or liquid-liquid phase separation (LLPS). Specifically, engineering is required to maximize the enthalpic contributions at the crystal contacts while simultaneously reducing the entropic penalty associated with crystallization.

2. Surface Engineering via Physicochemical Approaches

The thermodynamic driving force for crystallization is represented by the change in Gibbs free energy, DGcryst= DHcryst - TDScryst. As a protein transitions from solution to a crystal lattice, it loses translational and rotational degrees of freedom, making the entropy change DS typically negative (unfavorable). To compensate for this entropic loss, an entropic gain from the release of solvent molecules and an enthalpic gain DH from crystal contact formation are required.

2.1. Surface Entropy Reduction (SER) and Its Extensions

One of the primary thermodynamic barriers to crystallization is the loss of conformational entropy TDS

conf that occurs when flexible side chains on the protein surface become fixed within the crystal lattice. Large, flexible polar residues like lysine (Lys) and glutamic acid (Glu) have high conformational entropy and act as an "Entropy Shield," inhibiting the formation of crystal contacts [

5,

6].

2.1.1. Lys/Glu to Ala Substitution

Derewenda and colleagues proposed the surface entropy reduction strategy, which involves substituting surface clusters of high-entropy residues (Lys/Glu) with alanine (Ala), which lacks a side chain and possesses minimal conformational entropy. In principle, substitution with Ala avoids the entropic loss penalty associated with crystallization by eliminating side-chain flexibility. Furthermore, the small Ala side chain can create cavities or grooves on the molecular surface, which may facilitate the formation of new crystal contacts by allowing hydrophobic residues from an adjacent molecule to fit in. This method has shown dramatic success with difficult-to-crystallize proteins like RhoGDI and PDZRhoGEF, enabling high-resolution structure determination [

7,

8]. For instance, a RhoGDI mutant yielded high-quality crystals not obtained with the wild type, leading to a successful 1.3 Å resolution analysis [

9]. To facilitate this process, prediction tools like the SERp server have been developed to automatically select surface clusters for mutation, based on secondary structure prediction and evolutionary conservation, without disrupting the protein fold [

10].

2.1.2. Use of Alternative Residues

While Ala is the standard substitution residue, replacement with tyrosine can be more effective in specific situations. Tyrosine is frequently observed at antigen-antibody interfaces. It is less geometrically restrictive than long polar chains and is better at forming specific interactions, such as hydrogen bonds or p- p interactions. This can induce strong contacts with a smaller entropic cost compared to long-chain polar residues [

11].

2.1.3. Introduction of Electrostatic Interactions

While SER is an approach to "remove" the entropic barrier, recent efforts have progressed toward actively "creating" enthalpic favorability. This strategy involves the deliberate introduction of charged residues (Asp, Glu, Arg, Lys) at the intended crystal contact sites to form salt bridges with the adjacent molecule. In a notable case study, Weuster-Botz and colleagues dramatically improved the crystallization rate and yield of

Lactobacillus brevis Alcohol Dehydrogenase (LbADH) by substituting a threonine with glutamic acid (T102E) [

12]. Mechanistically, Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations suggested that a weak, water-mediated interaction in the wild type was transformed into contacts with strengthened direct ionic bonds and hydrophobic interactions in the mutant, thereby increasing contact stability [

13]. This approach is also being applied to streamline the crystallization of proteins in industrial purification processes, known as technical crystallization [

14,

15].(

Figure 1)

2.2. Chemical Surface Modification

In addition to genetic engineering, chemical modification of purified proteins is a viable strategy. The most established method is the reductive methylation of lysine residues [

16]. In this reaction, formaldehyde and dimethylamine borane are used to convert the primary amine of lysine into a tertiary amine, yielding dimethyllysine. This modification retains the positive charge of lysine but alters the solvation shell, thereby increasing hydrophobicity and bulkiness. Structural analysis indicates that dimethylated lysines are more prone to forming cation-p interactions and specific salt bridges (e.g., with Glu), exhibiting a stereochemically distinct interaction mode compared to unmodified lysine. Consequently, this method has a strong track record and is widely used as a salvage strategy for proteins that fail to crystallize in standard screens, with numerous reported successes. [

17].

3. Utilizing Fusion Partners and Crystallization Chaperones

When surface engineering alone is insufficient, or when expression and stability issues are present, the use of fusion partners that provide a crystallization "scaffold" becomes a powerful strategy.

3.1. Rigid Fusion Partners

The main challenge with fusion protein methods is the flexibility of the linker between the target protein and the fusion partner, which can inhibit ordered formation within the crystal lattice. To address this, Maltose-Binding Protein (MBP), while well-known as a solubilization tag, is also utilized as a crystallization chaperone. The key to success with MBP is designing a short, rigid linker (e.g., an AAA linker) to eliminate flexibility between the domains, effectively allowing the helices of both partners to connect continuously [

18]. This design permits the crystallizability of MBP to propagate to the target protein, thereby facilitating lattice formation. In the realm of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), the strategy of replacing the intracellular loop 3 (ICL3) with T4 Lysozyme (T4L) or the thermostabilized cytochrome b

562 (BRIL) proved to be revolutionary. These fusion partners provide the necessary polar surface area often lacking in the hydrophobic transmembrane domain, thereby dictating the formation of the crystal lattice [

19,

20]. This technique has successfully led to the resolution of numerous GPCR structures, including that of the b2-adrenergic receptor. Additionally, a "termini restraining" method has been reported where the N- and C-termini of membrane proteins are constrained using self-associating split-sfGFP to stabilize the overall protein structure and promote crystallization [

21].

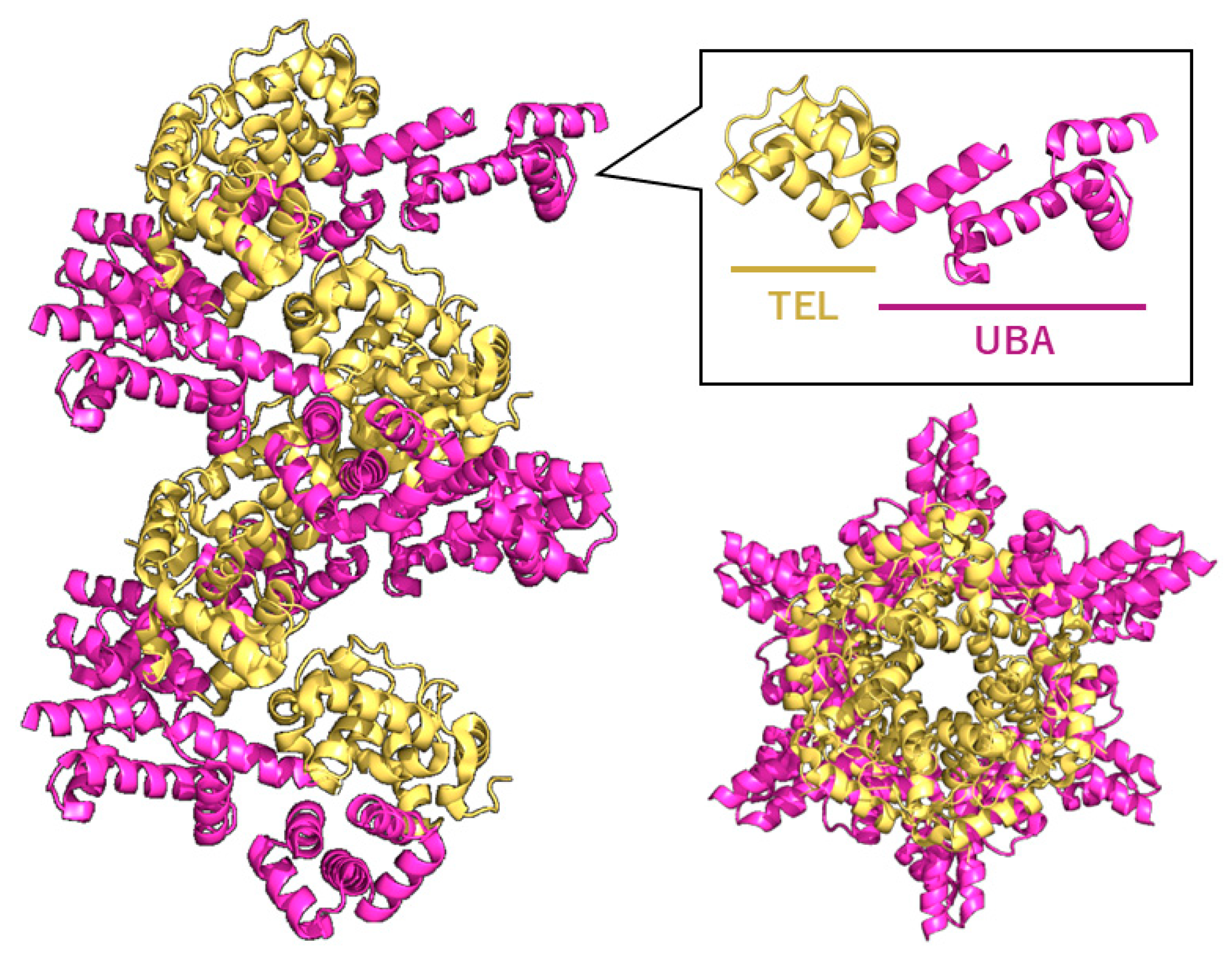

3.2. TELSAM as Polymeric Crystallization Enhancement

TELSAM represents a new paradigm among crystallization chaperones due to its intrinsic ability to form helical polymers. Polymerization occurs via head-to-tail interactions within the SAM domain, and the V112E mutation renders the assembly pH-dependent and reversible [

22]. Fusing a target protein to TELSAM arranges the target helically, resulting in an avidity effect that amplifies the target's interactions; this provides sufficient strength to stabilize the crystal lattice, even for interactions that would be too weak for crystallization on their own [

23]. Contrary to conventional wisdom, TELSAM fusion proteins have been shown to crystallize even at extremely low protein concentrations of 0.1 – 0.2 mg/mL [

24]. Interestingly, TELSAM can promote crystallization even with a flexible linker, largely because the strong orientation control provided by the polymer compensates for the linker's freedom, effectively "trapping" the target protein within the crystal lattice. Recent work on the human TNK1 UBA domain demonstrated crystallization at just 0.2 mg/mL when fused to TELSAM, with the crystal lattice forming through the target protein even when the TELSAM polymers do not directly contact each other [

24]. This feature makes it a powerful tool for proteins difficult to prepare in large quantities. (

Figure 2)

3.3. Antibody Fragments

Co-crystallization with antibody fragments is a classic and powerful technique that fixes a specific conformation of the target and expands the crystallizable surface area. Nanobody is a single-domain antibodies derived from camelids are small, highly stable, and capable of binding to concave epitopes. They are widely used as crystallization chaperones, especially for membrane proteins like GPCRs and transporters[

25]. Nanobodies stabilize a specific functional state of the target, enabling structural analysis.

4. Control of Complexes and Structural Homogeneity

Crystallizing multi-protein or protein–nucleic acid assemblies requires an additional conceptual layer beyond that applied to monomeric proteins: complexes behave as dynamic equilibria whose composition, structural uniformity, and stability are strongly influenced by buffer chemistry, precipitants, oxidation state, and mixing ratios. Accordingly, achieving diffraction-quality crystals relies on rational control of these equilibria. Drawing from both our experience and representative systems, we outline here general principles that guide the stabilization and homogenization of complexes prior to crystallization.

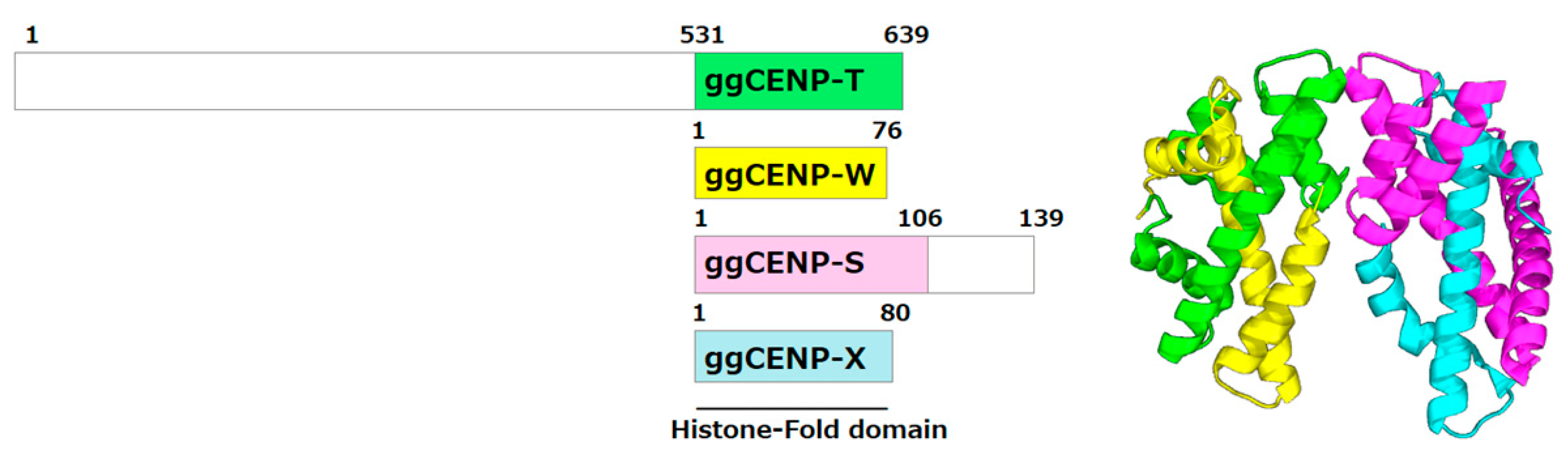

4.1. Identifying the Stable Unit

A critical first step is determining the minimal stable assembly, which often cannot be inferred solely from sequence-defined domain boundaries. Many complexes exhibit emergent stability only when maintained as specific subassemblies. In our studies of centromeric proteins, we found that the four components CENP-T, -W, -S, and -X form a robust heterotetramer (CENP-T-W-S-X), analogous to the histone H3–H4 complex [

26]. Isolated crystallization of the CENP-T-W and CENP-S-X subcomplexes further revealed remarkable structural similarity between the two, including conservation of key tetramerization residues. These findings highlight a generalizable principle: biochemical delineation of the stable oligomeric state—using SEC, EMSA, thermostability measurements, and structure prediction—is often decisive for crystallization success. This approach is broadly applicable to transcriptional regulators, helicase–loader assemblies, and chromatin-associated complexes that frequently misbehave when fragmented into overly simplified constructs. (

Figure 3)

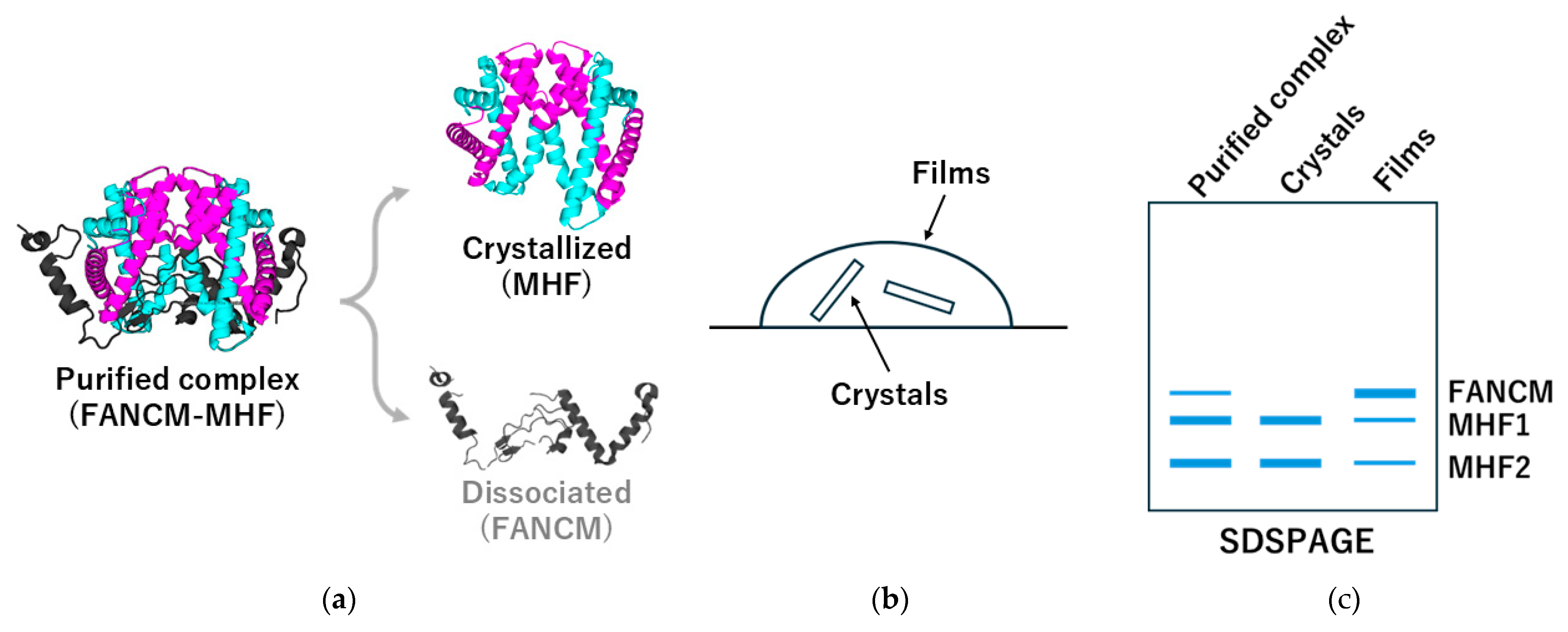

4.2. Controlling Dissociation and Optimizing Solution Conditions

Because protein complexes exist in equilibrium, crystallization conditions can unintentionally promote dissociation, resulting in crystals composed of only the most stable subunit. This was evident in the crystallization of the FANCM–MHF complex, where initial crystals contained only the MHF (CENP-S-X) portion after the FANCM peptide dissociated under MPD-rich and mildly oxidative conditions [

27]. Such behavior underscores the need to assess dissociation constants, evaluate sensitivity to precipitants and redox conditions, and tune ionic strength and buffer composition to maintain the correct assembly. Equally important is the verification of crystal composition—typically by SDS-PAGE or mass spectrometry of dissolved crystals—to avoid misinterpretation of results. In this way, crystallization becomes a controlled manipulation of binding equilibria rather than a passive screening process. (

Figure 4)

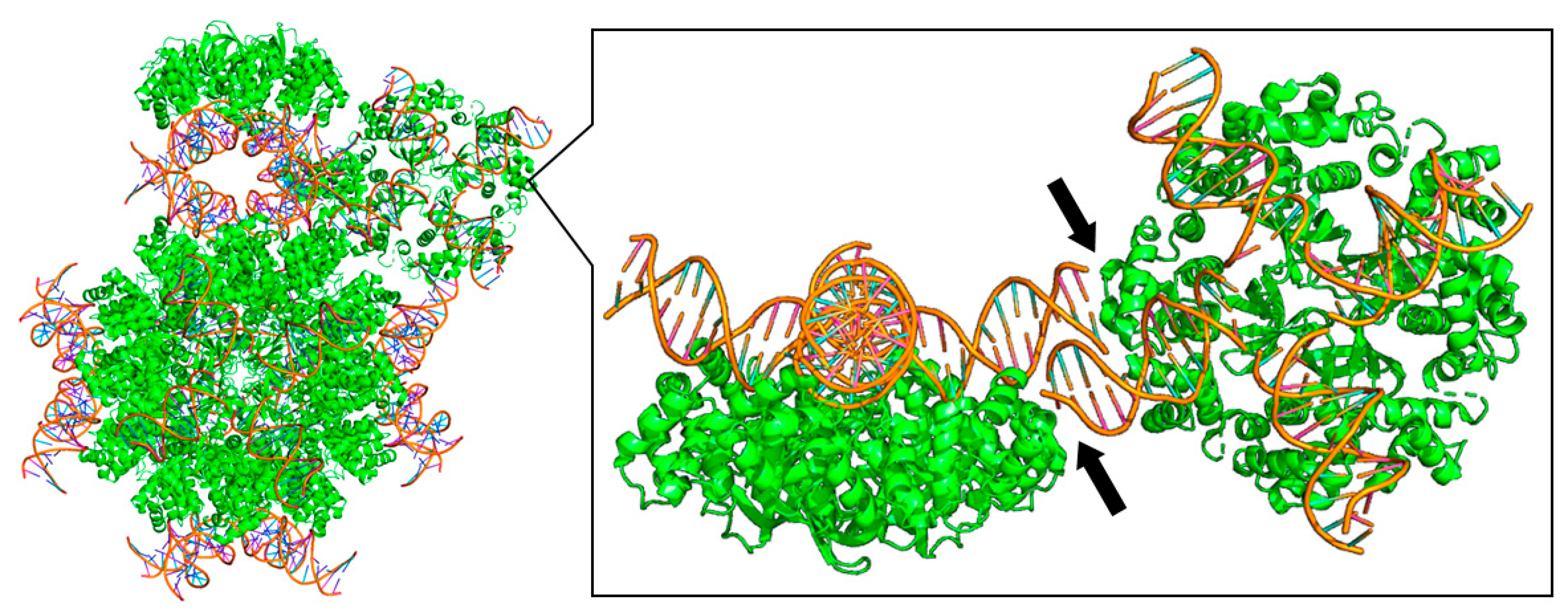

4.3. Engineering Nucleic-Acid Components in Protein–DNA Complex Crystallizations

For protein–nucleic acid complexes, the nucleic acid frequently functions as a structural element of the crystal lattice rather than as a mere ligand. Consequently, DNA or RNA must be engineered with the same degree of intentionality as the protein construct. In the crystallization of the CENP-S-X complex, systematic variation of double-stranded DNA length revealed substantial effects on space group (P2₁ versus C2) and diffraction resolution, even when altered by only a few base pairs [

28]. Differences between blunt and overhanging ends further influenced packing interactions and cryoprotection behavior.

Importantly, alternative crystallization attempts by another group using different DNA lengths, sequences, and stoichiometric ratios resulted in much lower resolution structures [

29], underscoring how sensitive lattice formation is to nucleic-acid design variables. A similar principle emerges in structural studies of the Holliday junction-binding protein RuvA, where modifications in arm length, overhangs, or DNA sequence led to distinct binding modes and crystal packing arrangements [

30]. Collectively, these observations demonstrate a generalizable rule: nucleic acids must be treated as active design parameters—length, end configuration, and sequence composition often dictate lattice architecture and must be optimized deliberately. (

Figure 5)

4.4. A Generalized Workflow for Stabilizing and Crystallizing Complexes

The principles illustrated by representative systems—including CENP-T-W-S-X [

26], FANCM–MHF [

27], and the DNA-dependent crystallization behavior of CENP-S-X [

28,

29]—enable a generalized workflow for complexes of diverse composition. The process begins by defining the minimal stable unit through biochemical analysis and structure-informed construct design. Once this assembly is established, its dissociation behavior must be characterized, as precipitants or oxidative conditions can shift equilibrium and promote partial disassembly, as observed for FANCM–MHF [

27].

Solution stoichiometry should then be optimized so that the predominant species corresponds to the desired oligomeric form. For complexes involving nucleic acids or other ligands, these components must be treated as structural design variables, since even small modifications in DNA length, sequence, or end structure—illustrated by the contrasting crystallization outcomes of CENP-S-X–DNA in different laboratories [

28,

29]—can determine lattice symmetry and achievable resolution. Throughout this workflow, maintaining sample homogeneity is essential, and crystals must be validated by analyzing dissolved crystals to confirm their composition. Through this rational, equilibrium-informed approach, complex crystallization becomes a broadly transferable methodology rather than a system-specific empirical challenge.

5. Acceleration via AI and Computational Science

The evolution of structural prediction AI and computational science is revolutionizing crystallization strategies. These tools accelerate the entire process, from preliminary target assessment to the active design of crystal lattices.

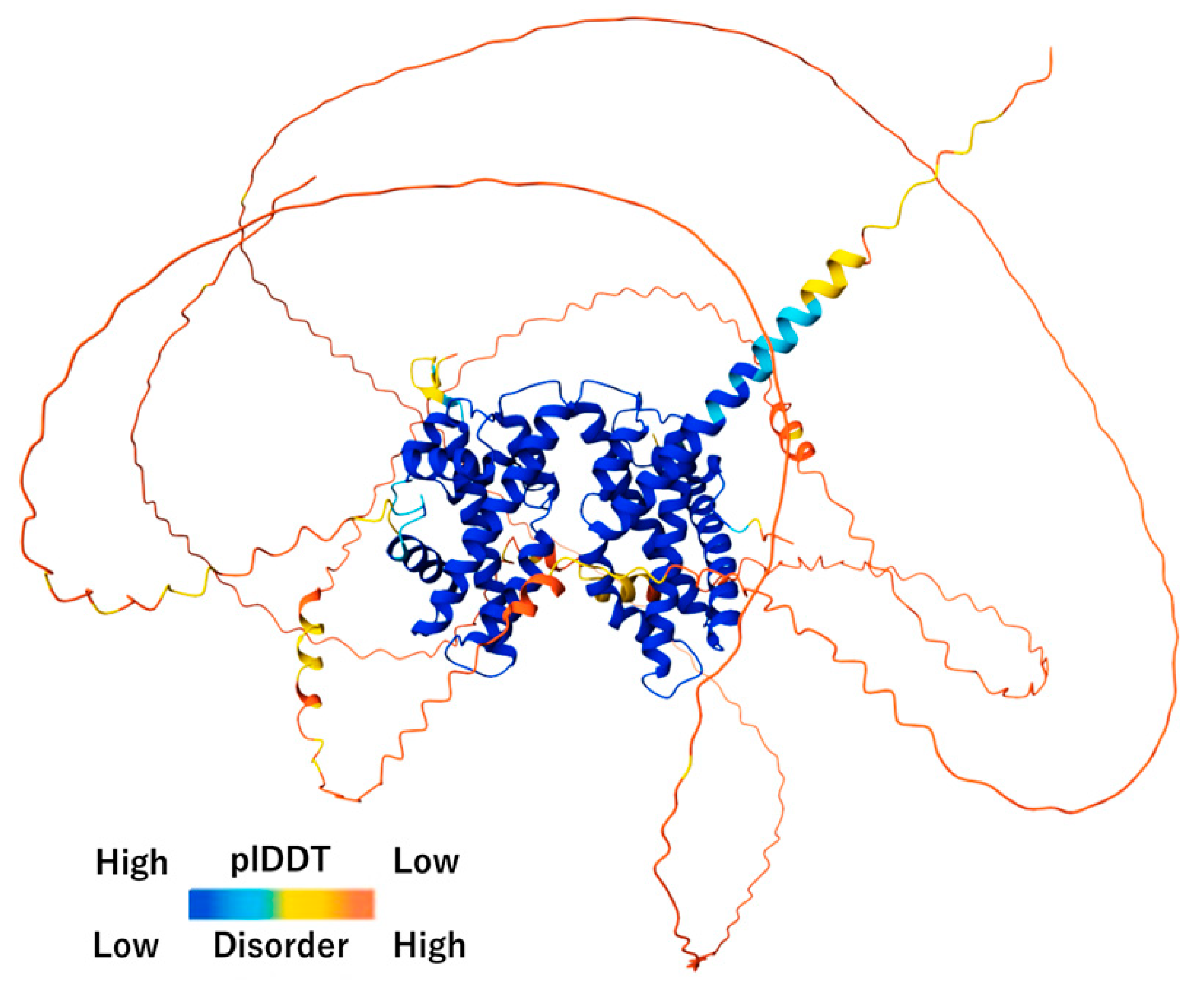

5.1. AlphaFold for Construct Design and Structure Prediction

AlphaFold2 and the latest AlphaFold3 not only provide highly accurate structure predictions but also precisely predict domain boundaries and intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) through the pLDDT score (local confidence score) and Predicted Aligned Error (PAE) [

31,

32]. In terms of applications, this capability allows for the rapid in silico design of crystallization-appropriate domain boundaries without the need for experimental limited proteolysis. Consequently, the identification of stable domains, traditionally determined by limited proteolysis and mass spectrometry, can now be achieved with high accuracy derived solely from sequence information. Furthermore, the predicted structural model can be utilized to identify potential sites for SER mutation (e.g., surface loops), while AlphaFold-Multimer can guide the mixing ratio for co-crystallization by predicting the complex's stoichiometry and interaction interface [

33]. (

Figure 6)

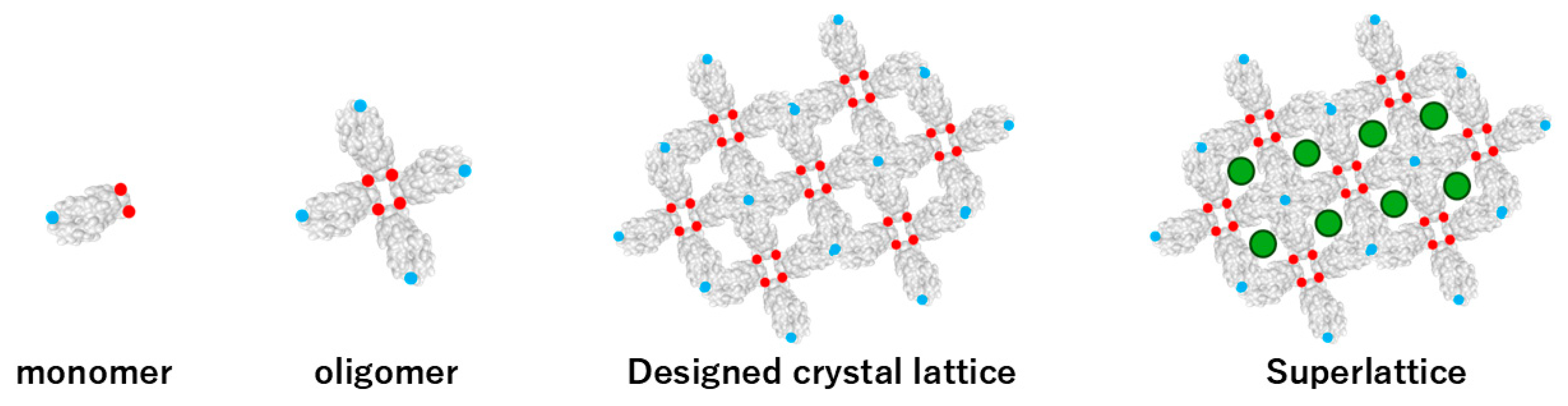

5.2. De Novo Crystal Design and Artificial Lattices

Protein design technologies using Rosetta and RFdiffusion have moved beyond merely modifying existing proteins to the level of

De Novo (from scratch) design of proteins that self-assemble into specific crystal lattices. Regarding programmed self-assembly, hierarchical assembly methods are employed to computationally design proteins that self-assemble into three-dimensional crystal lattices with specific symmetries (e.g., P6 symmetry or cubic symmetry) at atomic-level accuracy [

34,

35]. These designs involve engineering an oligomeric building block (e.g., a trimer) and computationally designing the interfaces so they interact at specific angles and distances. In a significant application, Li and colleagues designed highly porous three-dimensional protein crystals [

36]. These artificial lattices are expected to function as the "ultimate scaffold" to capture and align guest proteins for structural analysis. A future possibility exists wherein a guest protein is fused to a part of this artificial lattice, allowing it to be arrayed according to the designed lattice's order; this would enable structure determination even if the guest protein lacks intrinsic crystallizability, holding the potential to completely transform protein crystallization from a "probabilistic search" to a "deterministic design." (

Figure 7)

6. Conclusions and Outlook

Protein crystallization is no longer adequately described as a “game of chance.” Instead, it is evolving into a rational engineering discipline that integrates physicochemical principles, molecular design, and computational prediction.

A practical workflow emerges from this perspective:

- 1.

-

Target Assessment (AI-informed)

Predict domain boundaries and IDRs using AlphaFold; identify regions suitable for truncation or surface redesign.

This reduces the need for labor-intensive proteolysis experiments.

- 2.

-

Stabilization by Biochemistry

Determine the minimal stable unit via biochemical assays and structure prediction.

For complexes, evaluate dissociation behavior and optimize stoichiometry.

- 3.

-

Surface and Interface Engineering (Strategy I)

Improve crystallizability by altering surface features through mutations—SER, electrostatic engineering, and context-dependent Arg substitutions—to introduce directional contacts and enhance lattice compatibility.

- 4.

-

Scaffold Consideration (Strategy II)

Introduce crystallization chaperones or fusion partners such as MBP, BRIL, or TELSAM to provide rigid surfaces or polymeric orientation control.

TELSAM is particularly valuable for targets available only at low concentrations.

- 5.

-

Iterative Screening and Feedback

Always verify crystal composition, especially for complexes, and treat nucleic acids as tunable design variables.

Computational predictions can be fed back into construct redesign, enabling fast convergence on successful conditions.

Collectively, these strategies empower structural biologists to pursue increasingly complex and dynamic assemblies. While an element of “artistry” remains, crystallization has now matured into a highly systematic and engineerable process, poised to benefit further from the increasing integration of AI and de novo molecular design.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, S.I. and T.N.; writing—original draft preparation, S.I.; writing—review and editing, T.N.; visualization, S.I.; supervision, T.N.; funding acquisition, T.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partly supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI under Grant No. 23K056710 (to T.N.).

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT (OpenAI, version 5.1) and Gemini 3 for language refinement and structural suggestions. The authors have reviewed and edited all output and take full responsibility for the content.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- McPherson, A.; Gavira, J.A. Introduction to Protein Crystallization. Acta Crystallogr F Struct Biol Commun 2014, 70, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derewenda, Z.S.; Godzik, A. The “Sticky Patch” Model of Crystallization and Modification of Proteins for Enhanced Crystallizability. In Protein Crystallography; Wlodawer, A., Dauter, Z., Jaskolski, M., Eds.; Methods in Molecular Biology: New York, NY; Springer: New York, 2017; Vol. 1607, pp. 77–115. ISBN 978-1-4939-6998-2. [Google Scholar]

- Vekilov, P.G. The Two-Step Mechanism of Nucleation of Crystals in Solution. Nanoscale 2010, 2, 2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vekilov, P.G. Nucleation. Crystal Growth & Design 2010, 10, 5007–5019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derewenda, Z.S. Rational Protein Crystallization by Mutational Surface Engineering. Structure 2004, 12, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derewenda, Z.S.; Vekilov, P.G. Entropy and Surface Engineering in Protein Crystallization. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 2006, 62, 116–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longenecker, K.L.; Garrard, S.M.; Sheffield, P.J.; Derewenda, Z.S. Protein Crystallization by Rational Mutagenesis of Surface Residues: Lys to Ala Mutations Promote Crystallization of RhoGDI. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 2001, 57, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrard, S.M.; Longenecker, K.L.; Lewis, M.E.; Sheffield, P.J.; Derewenda, Z.S. Expression, Purification, and Crystallization of the RGS-like Domain from the Rho Nucleotide Exchange Factor, PDZ-RhoGEF, Using the Surface Entropy Reduction Approach. Protein Expression and Purification 2001, 21, 412–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mateja, A.; Devedjiev, Y.; Krowarsch, D.; Longenecker, K.; Dauter, Z.; Otlewski, J.; Derewenda, Z.S. The Impact of Glu→Ala and Glu→Asp Mutations on the Crystallization Properties of RhoGDI: The Structure of RhoGDI at 1.3 Å Resolution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 2002, 58, 1983–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldschmidt, L.; Cooper, D.R.; Derewenda, Z.S.; Eisenberg, D. Toward Rational Protein Crystallization: A Web Server for the Design of Crystallizable Protein Variants. Protein Science 2007, 16, 1569–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, D.R.; Boczek, T.; Grelewska, K.; Pinkowska, M.; Sikorska, M.; Zawadzki, M.; Derewenda, Z. Protein Crystallization by Surface Entropy Reduction: Optimization of the SER Strategy. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 2007, 63, 636–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowotny, P.; Hermann, J.; Li, J.; Krautenbacher, A.; Klöpfer, K.; Hekmat, D.; Weuster-Botz, D. Rational Crystal Contact Engineering of Lactobacillus Brevis Alcohol Dehydrogenase To Promote Technical Protein Crystallization. Crystal Growth & Design 2019, 19, 2380–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, J.; Bischoff, D.; Grob, P.; Janowski, R.; Hekmat, D.; Niessing, D.; Zacharias, M.; Weuster-Botz, D. Controlling Protein Crystallization by Free Energy Guided Design of Interactions at Crystal Contacts. Crystals 2021, 11, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walla, B.; Bischoff, D.; Janowski, R.; Von Den Eichen, N.; Niessing, D.; Weuster-Botz, D. Transfer of a Rational Crystal Contact Engineering Strategy between Diverse Alcohol Dehydrogenases. Crystals 2021, 11, 975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walla, B.; Maslakova, A.; Bischoff, D.; Janowski, R.; Niessing, D.; Weuster-Botz, D. Rational Introduction of Electrostatic Interactions at Crystal Contacts to Enhance Protein Crystallization of an Ene Reductase. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rayment, I. [12] Reductive Alkylation of Lysine Residues to Alter Crystallization Properties of Proteins. In Methods in Enzymology; Elsevier, 1997; Vol. 276, pp. 171–179. ISBN 978-0-12-182177-7. [Google Scholar]

- Walter, T.S.; Meier, C.; Assenberg, R.; Au, K.-F.; Ren, J.; Verma, A.; Nettleship, J.E.; Owens, R.J.; Stuart, D.I.; Grimes, J.M. Lysine Methylation as a Routine Rescue Strategy for Protein Crystallization. Structure 2006, 14, 1617–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smyth, D.R.; Mrozkiewicz, M.K.; McGrath, W.J.; Listwan, P.; Kobe, B. Crystal Structures of Fusion Proteins with Large-affinity Tags. Protein Science 2003, 12, 1313–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cherezov, V.; Rosenbaum, D.M.; Hanson, M.A.; Rasmussen, S.G.F.; Thian, F.S.; Kobilka, T.S.; Choi, H.-J.; Kuhn, P.; Weis, W.I.; Kobilka, B.K.; et al. High-Resolution Crystal Structure of an Engineered Human β2 -Adrenergic G Protein–Coupled Receptor. Science 2007, 318, 1258–1265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, E.; Thompson, A.A.; Liu, W.; Roth, C.B.; Griffith, M.T.; Katritch, V.; Kunken, J.; Xu, F.; Cherezov, V.; Hanson, M.A.; et al. Fusion Partner Toolchest for the Stabilization and Crystallization of G Protein-Coupled Receptors. Structure 2012, 20, 967–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, W. Protein Fusion Strategies for Membrane Protein Stabilization and Crystal Structure Determination. Crystals 2022, 12, 1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.A. Polymerization of the SAM Domain of TEL in Leukemogenesis and Transcriptional Repression. The EMBO Journal 2001, 20, 4173–4182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawarathnage, S.; Soleimani, S.; Mathis, M.H.; Bezzant, B.D.; Ramírez, D.T.; Gajjar, P.; Bunn, D.R.; Stewart, C.; Smith, T.; Pedroza Romo, M.J.; et al. Crystals of TELSAM–Target Protein Fusions That Exhibit Minimal Crystal Contacts and Lack Direct Inter-TELSAM Contacts. Open Biol. 2022, 12, 210271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawarathnage, S.; Tseng, Y.J.; Soleimani, S.; Smith, T.; Pedroza Romo, M.J.; Abiodun, W.O.; Egbert, C.M.; Madhusanka, D.; Bunn, D.; Woods, B.; et al. Fusion Crystallization Reveals the Behavior of Both the 1TEL Crystallization Chaperone and the TNK1 UBA Domain. Structure 2023, 31, 1589–1603.e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, S.G.F.; Choi, H.-J.; Fung, J.J.; Pardon, E.; Casarosa, P.; Chae, P.S.; DeVree, B.T.; Rosenbaum, D.M.; Thian, F.S.; Kobilka, T.S.; et al. Structure of a Nanobody-Stabilized Active State of the Β2 Adrenoceptor. Nature 2011, 469, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishino, T.; Takeuchi, K.; Gascoigne, K.E.; Suzuki, A.; Hori, T.; Oyama, T.; Morikawa, K.; Cheeseman, I.M.; Fukagawa, T. CENP-TWSX Forms a Unique Centromeric Chromatin Structure with a Histone-like Fold. Cell 2012, 148, 487–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S.; Nishino, T. Structural Analysis of the Chicken FANCM–MHF Complex and Its Stability. Acta Crystallogr F Struct Biol Commun 2021, 77, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ito, S.; Nishino, T. Biochemical and Crystallization Analysis of the CENP-SX–DNA Complex. Acta Crystallogr F Struct Biol Commun 2022, 78, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Saro, D.; Sachpatzidis, A.; Singh, T.R.; Schlingman, D.; Zheng, X.-F.; Mack, A.; Tsai, M.-S.; Mochrie, S.; Regan, L.; et al. The MHF Complex Senses Branched DNA by Binding a Pair of Crossover DNA Duplexes. Nat Commun 2014, 5, 2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariyoshi, M.; Nishino, T.; Iwasaki, H.; Shinagawa, H.; Morikawa, K. Crystal Structure of the Holliday Junction DNA in Complex with a Single RuvA Tetramer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000, 97, 8257–8262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly Accurate Protein Structure Prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; Adler, J.; Dunger, J.; Evans, R.; Green, T.; Pritzel, A.; Ronneberger, O.; Willmore, L.; Ballard, A.J.; Bambrick, J.; et al. Accurate Structure Prediction of Biomolecular Interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R.; O’Neill, M.; Pritzel, A.; Antropova, N.; Senior, A.; Green, T.; Žídek, A.; Bates, R.; Blackwell, S.; Yim, J.; et al. Protein Complex Prediction with AlphaFold-Multimer 2021.

- King, N.P.; Sheffler, W.; Sawaya, M.R.; Vollmar, B.S.; Sumida, J.P.; André, I.; Gonen, T.; Yeates, T.O.; Baker, D. Computational Design of Self-Assembling Protein Nanomaterials with Atomic Level Accuracy. Science 2012, 336, 1171–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanci, C.J.; MacDermaid, C.M.; Kang, S.; Acharya, R.; North, B.; Yang, X.; Qiu, X.J.; DeGrado, W.F.; Saven, J.G. Computational Design of a Protein Crystal. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012, 109, 7304–7309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, S.; Nattermann, U.; Bera, A.K.; Borst, A.J.; Yaman, M.Y.; Bick, M.J.; Yang, E.C.; Sheffler, W.; Lee, B.; et al. Accurate Computational Design of Three-Dimensional Protein Crystals. Nat. Mater. 2023, 22, 1556–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Surface entropy reduction strategies: Lys/Glu-to-Ala mutations and engineered electrostatic interactions. Surface entropy reduction (SER) approaches aim to increase crystallizability by removing high-entropy surface residues and introducing directional interactions at potential crystal contacts. Left: Lysine and glutamate residues act as “entropy shields” due to their high conformational entropy, inhibiting formation of ordered lattice contacts. Top right: Substitution of Lys/Glu clusters with alanine reduces conformational entropy and creates low-profile surfaces that facilitate packing interactions. Bottom right: Introduction of charged residues (Asp/Glu or Arg/Lys) promotes favorable enthalpic contributions by forming direct salt bridges or electrostatic interactions with adjacent molecules.

Figure 1.

Surface entropy reduction strategies: Lys/Glu-to-Ala mutations and engineered electrostatic interactions. Surface entropy reduction (SER) approaches aim to increase crystallizability by removing high-entropy surface residues and introducing directional interactions at potential crystal contacts. Left: Lysine and glutamate residues act as “entropy shields” due to their high conformational entropy, inhibiting formation of ordered lattice contacts. Top right: Substitution of Lys/Glu clusters with alanine reduces conformational entropy and creates low-profile surfaces that facilitate packing interactions. Bottom right: Introduction of charged residues (Asp/Glu or Arg/Lys) promotes favorable enthalpic contributions by forming direct salt bridges or electrostatic interactions with adjacent molecules.

Figure 2.

TELSAM-mediated crystallization enhancement and polymer-guided orientation control. TELSAM (Translocation ETS Leukemia SAM domain) forms a helical polymer that provides strong orientation control for fused target proteins. The TEL domain (yellow) assembles into a left-handed helical polymer, while the fused UBA domain (magenta) projects outward (PDBID:7TDY). Side and top views of the 7TDY crystal structure illustrate how the polymeric scaffold restricts rotational freedom and enhances the effective local concentration of the fused domain, enabling crystallization even at very low protein concentrations.

Figure 2.

TELSAM-mediated crystallization enhancement and polymer-guided orientation control. TELSAM (Translocation ETS Leukemia SAM domain) forms a helical polymer that provides strong orientation control for fused target proteins. The TEL domain (yellow) assembles into a left-handed helical polymer, while the fused UBA domain (magenta) projects outward (PDBID:7TDY). Side and top views of the 7TDY crystal structure illustrate how the polymeric scaffold restricts rotational freedom and enhances the effective local concentration of the fused domain, enabling crystallization even at very low protein concentrations.

Figure 3.

Domain organization of chicken CENP-T, CENP-W, CENP-S, and CENP-X and their conserved heterotetrameric structure. Domain architectures of the four centromeric proteins are shown (left), highlighting the conserved histone-fold domains. The right panel depicts the heterotetrameric CENP-T–W–S–X structure (PDBID:3VH5), where each subunit adopts a histone-fold arrangement analogous to canonical H3–H4 heterotetramers. CENP-T contains an extensive intrinsically disordered N-terminal region, whereas CENP-S possesses a C-terminal disordered tail; these flexible regions are absent from the heterotetrameric histone-fold core. This assembly represents the minimal stable unit required for crystallographic and biochemical analyses of centromeric nucleoprotein complexes.

Figure 3.

Domain organization of chicken CENP-T, CENP-W, CENP-S, and CENP-X and their conserved heterotetrameric structure. Domain architectures of the four centromeric proteins are shown (left), highlighting the conserved histone-fold domains. The right panel depicts the heterotetrameric CENP-T–W–S–X structure (PDBID:3VH5), where each subunit adopts a histone-fold arrangement analogous to canonical H3–H4 heterotetramers. CENP-T contains an extensive intrinsically disordered N-terminal region, whereas CENP-S possesses a C-terminal disordered tail; these flexible regions are absent from the heterotetrameric histone-fold core. This assembly represents the minimal stable unit required for crystallographic and biochemical analyses of centromeric nucleoprotein complexes.

Figure 4.

Dissociation during crystallization of the FANCM–MHF complex and verification of crystal composition. During crystallization of the chicken FANCM–MHF complex (PDBID:7DA2), FANCM can dissociate under certain conditions (e.g., MPD-rich precipitants or oxidation), resulting in crystals containing only the MHF subcomplex. (a) The purified FANCM-MHF complex may separate into crystallized MHF and dissociated FANCM fragments. (b) A schematic of the crystallization drop shows crystal formation and film-like aggregates. (c) SDS–PAGE analysis of dissolved crystals is essential to confirm the composition and avoid misinterpretation of crystallographic data.

Figure 4.

Dissociation during crystallization of the FANCM–MHF complex and verification of crystal composition. During crystallization of the chicken FANCM–MHF complex (PDBID:7DA2), FANCM can dissociate under certain conditions (e.g., MPD-rich precipitants or oxidation), resulting in crystals containing only the MHF subcomplex. (a) The purified FANCM-MHF complex may separate into crystallized MHF and dissociated FANCM fragments. (b) A schematic of the crystallization drop shows crystal formation and film-like aggregates. (c) SDS–PAGE analysis of dissolved crystals is essential to confirm the composition and avoid misinterpretation of crystallographic data.

Figure 5.

DNA length–dependent changes in crystal packing: example from RuvA–Holliday junction complexes. Crystal packing of the RuvA–Holliday junction complex (PDBID:1C7Y) is highly sensitive to the length and configuration of the bound DNA. Left: overall view of crystal packing of the tetrameric RuvA complex bound to Holliday junction DNA. Right: magnified view highlighting how differences in DNA arm length alter intermolecular contacts (arrows), generating distinct lattice architectures. This illustrates the general principle that nucleic-acid components must be treated as structural design variables in crystallization trials.

Figure 5.

DNA length–dependent changes in crystal packing: example from RuvA–Holliday junction complexes. Crystal packing of the RuvA–Holliday junction complex (PDBID:1C7Y) is highly sensitive to the length and configuration of the bound DNA. Left: overall view of crystal packing of the tetrameric RuvA complex bound to Holliday junction DNA. Right: magnified view highlighting how differences in DNA arm length alter intermolecular contacts (arrows), generating distinct lattice architectures. This illustrates the general principle that nucleic-acid components must be treated as structural design variables in crystallization trials.

Figure 6.

AlphaFold-based structural prediction reveals ordered cores and extensive intrinsically disordered regions. AlphaFold3 prediction of the full-length chicken CENP-T-W-S-X complex illustrates the distribution of predicted confidence (pLDDT) and intrinsic disorder. Ordered regions (blue) show high pLDDT values, forming stable globular domains, while extended low-confidence regions (orange–red) correspond to intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs). Such predictions guide rational construct design by identifying domain boundaries, flexible linkers to remove, and targets for surface engineering.

Figure 6.

AlphaFold-based structural prediction reveals ordered cores and extensive intrinsically disordered regions. AlphaFold3 prediction of the full-length chicken CENP-T-W-S-X complex illustrates the distribution of predicted confidence (pLDDT) and intrinsic disorder. Ordered regions (blue) show high pLDDT values, forming stable globular domains, while extended low-confidence regions (orange–red) correspond to intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs). Such predictions guide rational construct design by identifying domain boundaries, flexible linkers to remove, and targets for surface engineering.

Figure 7.

De novo design of protein crystal lattices through hierarchical assembly. A monomeric building block (left) are engineered with specific intermolecular interaction patches, shown as red (interaction type A) and blue (interaction type B) circles. These complementary interaction sites drive the formation of defined oligomeric units (second panel), which further assemble into designed two-dimensional or three-dimensional protein crystals lattices (third panel). In the superlattice architecture (right), guest molecules—depicted as green circles—are intentionally incorporated into predefined cavities, demonstrating the ability of de novo lattices to host external functional components through programmable interface design.

Figure 7.

De novo design of protein crystal lattices through hierarchical assembly. A monomeric building block (left) are engineered with specific intermolecular interaction patches, shown as red (interaction type A) and blue (interaction type B) circles. These complementary interaction sites drive the formation of defined oligomeric units (second panel), which further assemble into designed two-dimensional or three-dimensional protein crystals lattices (third panel). In the superlattice architecture (right), guest molecules—depicted as green circles—are intentionally incorporated into predefined cavities, demonstrating the ability of de novo lattices to host external functional components through programmable interface design.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).