Submitted:

11 December 2025

Posted:

12 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

MSC: 62C12; 62F10; 62F15

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Results

2.1. The Bayes Estimators and the PESLs

2.2. The Empirical Bayes Estimators of

3. Simulations

3.1. Consistencies of the Moment Estimators and the MLEs

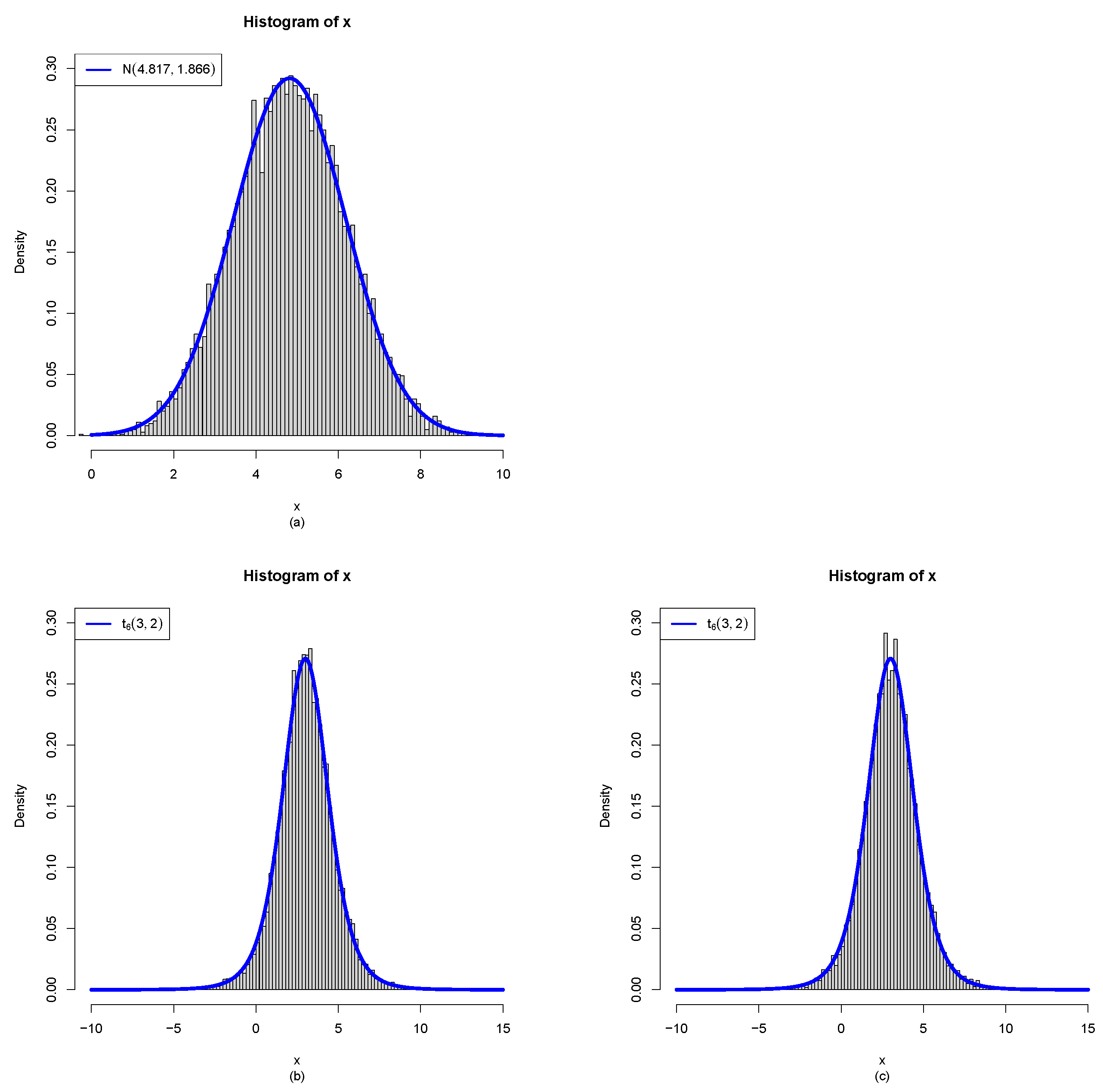

- Plot (a): the sample generated from (1) are iid from with and .

- The moment estimators of the hyperparameters for sample are far away from the true hyperparameters , and thus the samples generated from the model (1) can not be used to estimate the hyperparameters .

- For , since the moment estimator of is which is negative, the MLE method fails to iterate, and thus the MLEs of the hyperparameters are equal to the moment estimators.

- For and , the moment estimators and the MLEs of the hyperparameters are close to the true hyperparameters , and thus the samples generated from the model (2) can be used to estimate the hyperparameters .

- For and , the MLEs are closer to the true hyperparameters than the moment estimators for this simulation.

- With , , or , the frequencies of the estimators approach zero as n tends to infinity, indicating that both the moment estimators and the MLEs are consistent for estimating the hyperparameters. In the case of , the frequencies of and remain relatively high (at least across all scenarios). Nevertheless, a decreasing trend toward zero is evident as n grows large, suggesting eventual convergence.

- By comparing the frequencies corresponding to , , and , we find that as decreases, the frequencies generally increase. This occurs because the constraintsbecome easier to satisfy when is smaller.

- When comparing the moment estimators with the MLEs of the hyperparameters , , and , it is observed that for large sample sizes n, the MLEs exhibit smaller values than the moment estimators. This indicates that, in terms of consistency, the MLEs perform more reliably in estimating the hyperparameters.

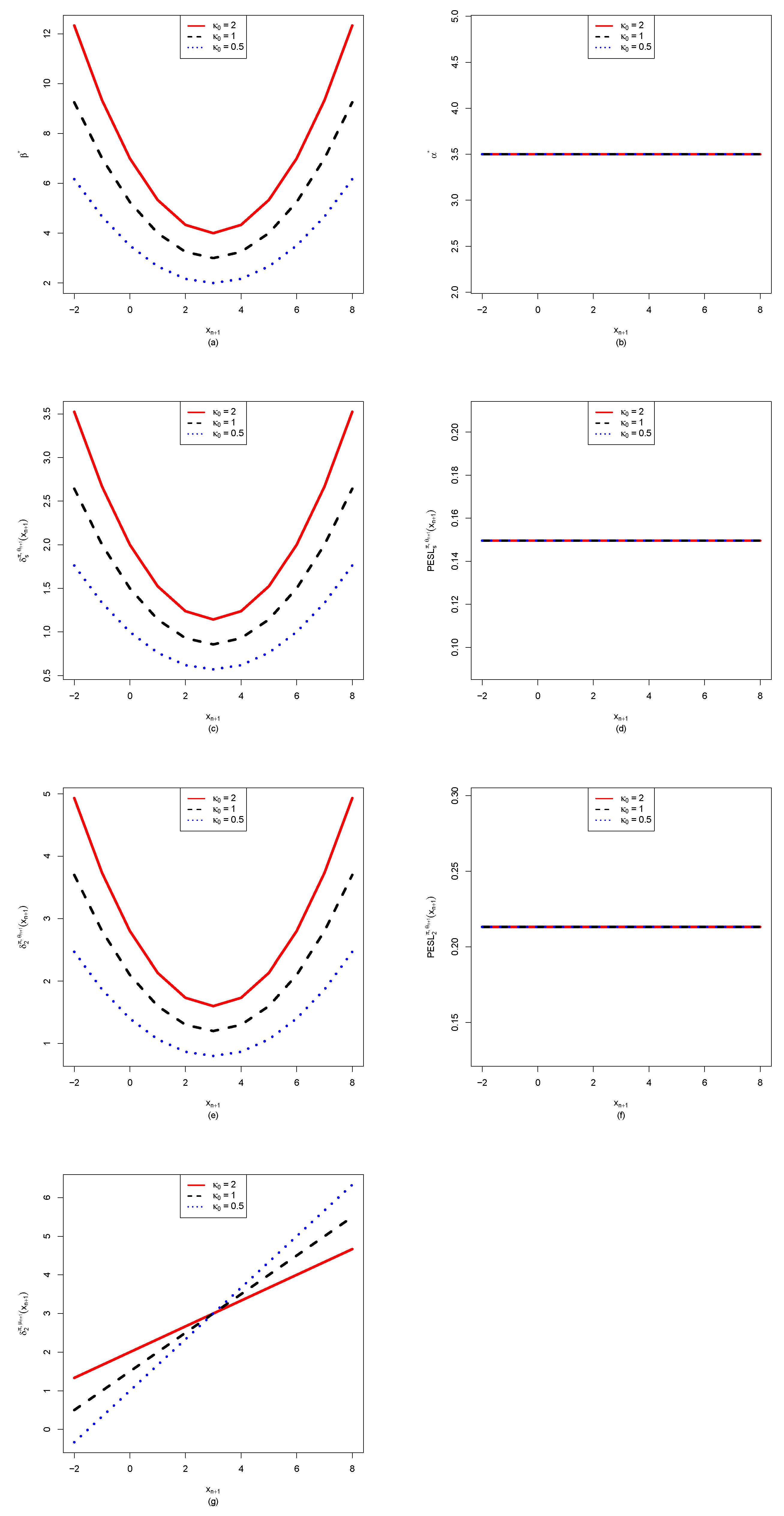

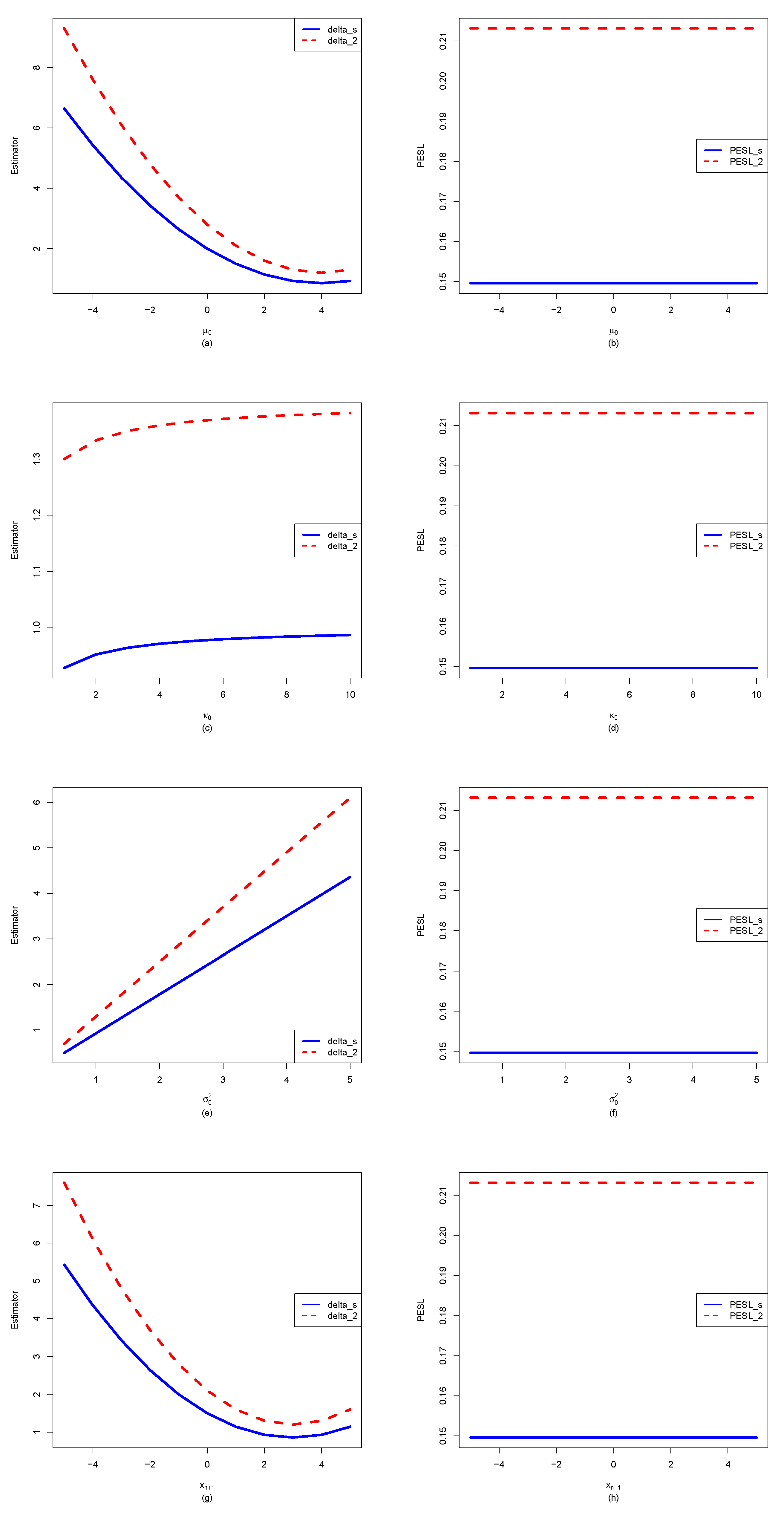

3.2. The Effect of for Quantities of Interest as Functions of

- From the left column of the figure, we see that , , , and are affected by . Moreover, , , and are quadratic functions of (note that their y ranges are different), while is a linear function of .

- For plot (a), we observe that when using will underestimate when using , and it will overestimate when using . In other words, is an increasing function of for a fixed . Similar phenomena are observed for (plot (c)) and (plot (e)).

- For (plot (g)), we observe an interesting phenomenon that when ( in the simulation), when using will underestimate that when using , and it will overestimate that when using . In other words, is an increasing function of when . However, when , we observe a reversed phenomenon that when using will overestimate that when using , and it will underestimate that when using . In other words, is a decreasing function of when . The phenomena can be explained by the theoretical analysis of

- From the right column of the figure, we see that , , and are not affected by . Moreover, they also do not depend on .

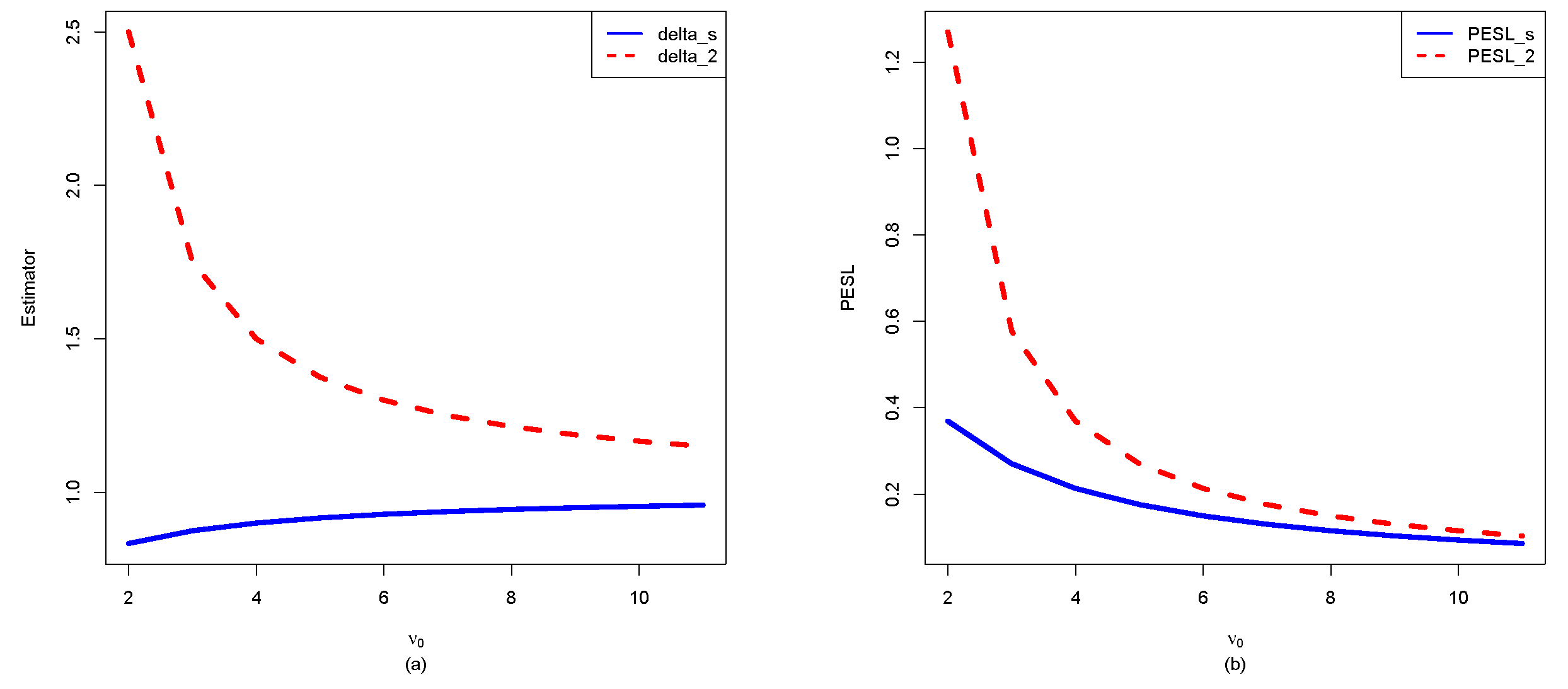

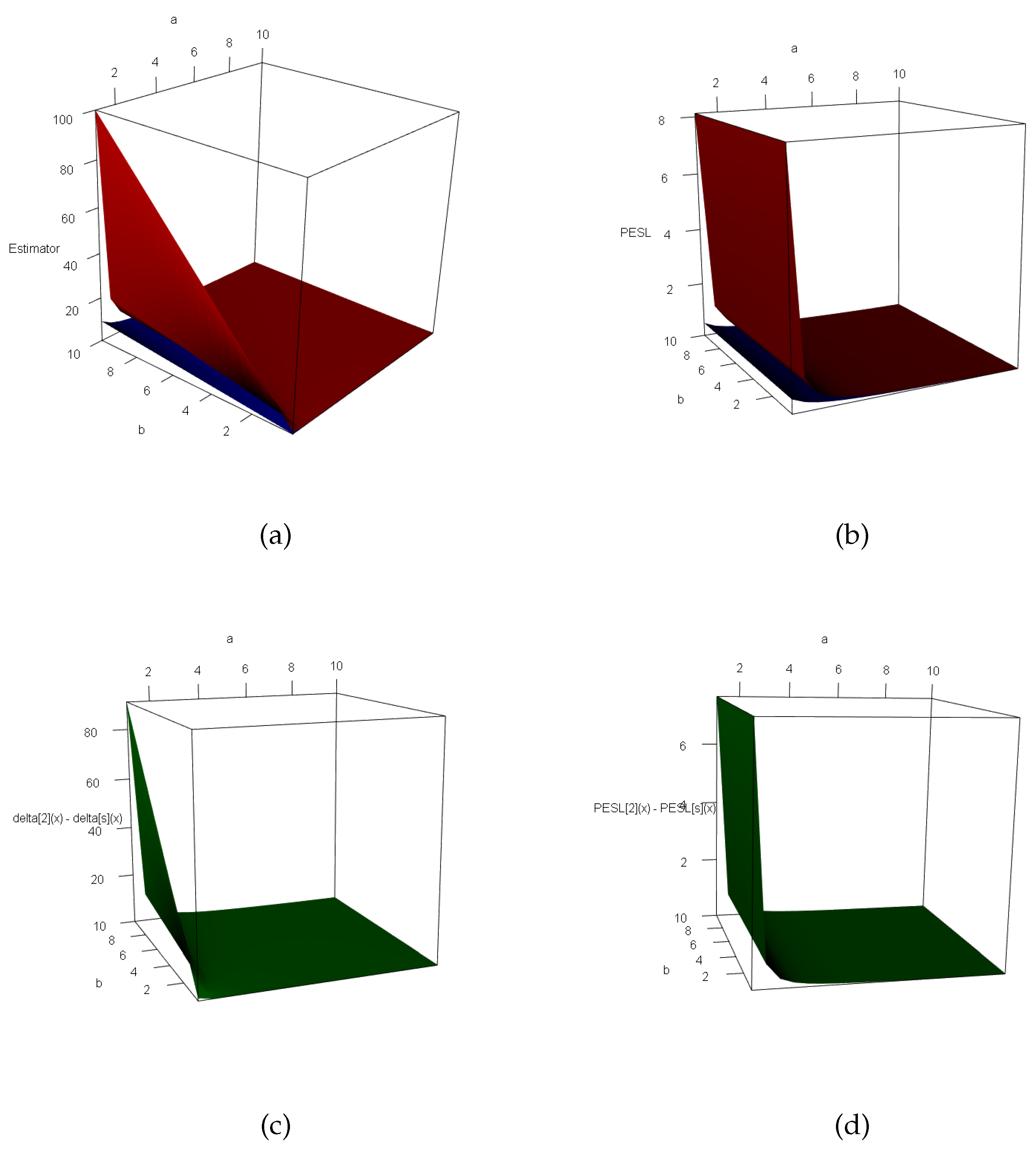

3.3. Two Inequalities of the Bayes Estimators and the PESLs

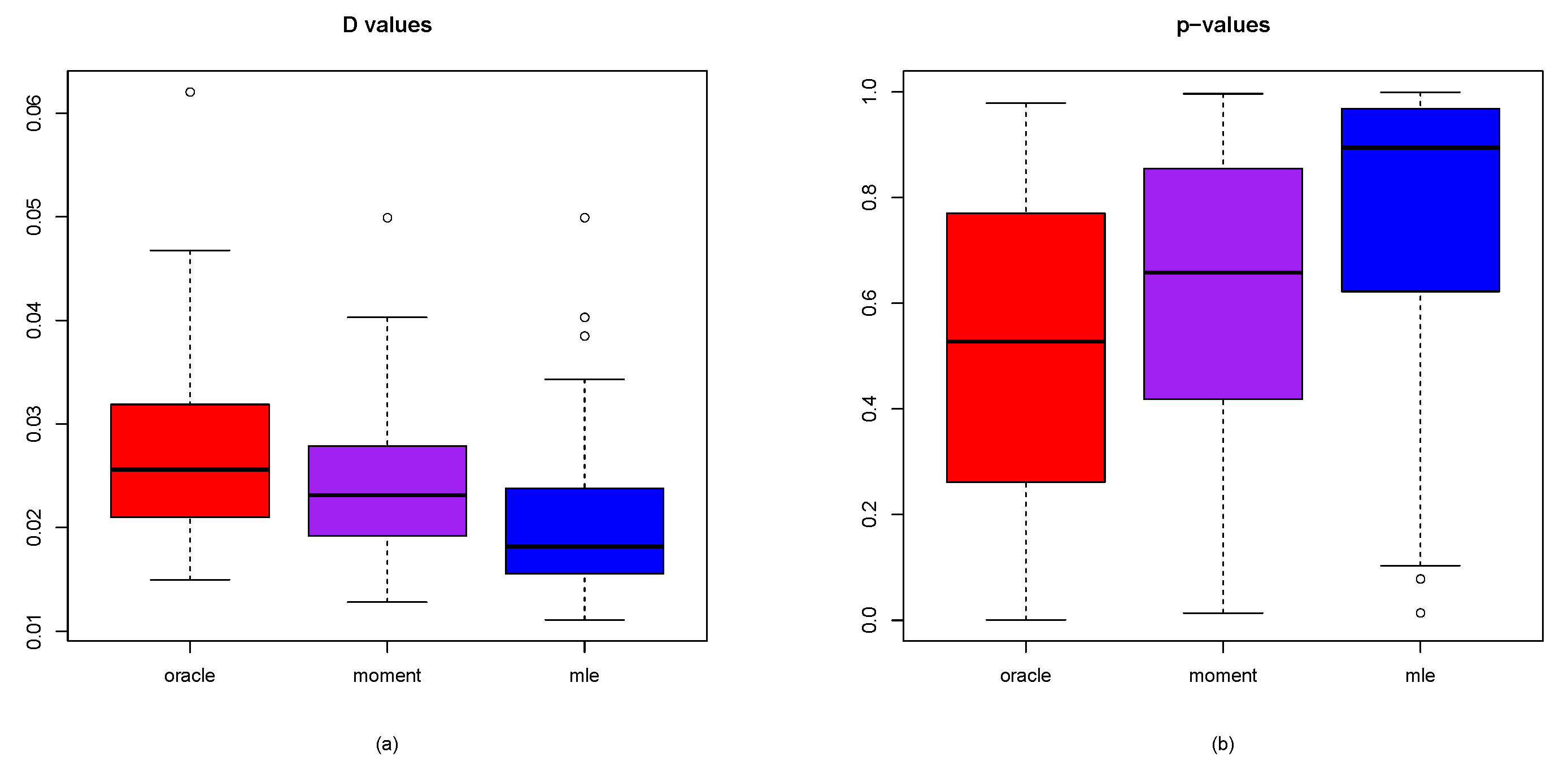

3.4. Goodness-of-Fit of the Model: KS Test

- The values corresponding to the three approaches are , , and , respectively. This indicates that the MLE method performs best, followed by the moment method, while the oracle method yields the least satisfactory results. A plausible explanation for this outcome is that, as shown in (25), the empirical cdf relies on observed data, and similarly, the theoretical cdf used in both the moment and MLE methods are derived from data. In contrast, the associated with the oracle method does not depend on actual data.

- The corresponding to the three methods are , , and , respectively, indicating that the MLE method performs best, followed by the moment method, with the oracle method ranking last. A plausible explanation for this outcome is provided in the preceding paragraph.

- The values for the three approaches are , , and , respectively. For the MLE method, the value exceeds half of the M simulations. In terms of performance ranking, the methods are ordered as follows: MLE method, oracle method, and moment method.

- The three methods yield values of , , and , respectively. Since a lower D value is associated with a higher p-value, the method producing the minimum D value will also produce the maximum p-value. As a result, the and values are identical across the three approaches. Based on performance, the methods can be ranked in descending order of preference as follows: MLE method, oracle method, and moment method.

- The values for the three methods are , , and , respectively, indicating that these values are close to . This suggests that all three methods exhibit strong performance in terms of model fit.

- To summarize, the MLE method consistently achieves the top ranking across all five evaluation metrics—, , , , and . When comparing the moment method with the MLE method, the results indicate that the MLE method outperforms the moment method on each of these five criteria.

- The D values obtained by the oracle method are higher than those of the other two approaches. Since lower D values indicate better performance, the preferred ranking of the three methods is as follows: MLE method, moment method, and then the oracle method.

- The oracle method yields the lowest p-values compared to the other two approaches. Since higher p-values are preferable, the methods can be ranked in descending order of preference as follows: MLE method, moment method, and finally the oracle method.

- Large D values are associated with small p-values, whereas small D values are linked to large p-values.

- Based on the D values and p-values, the MLE method outperforms the method of moments.

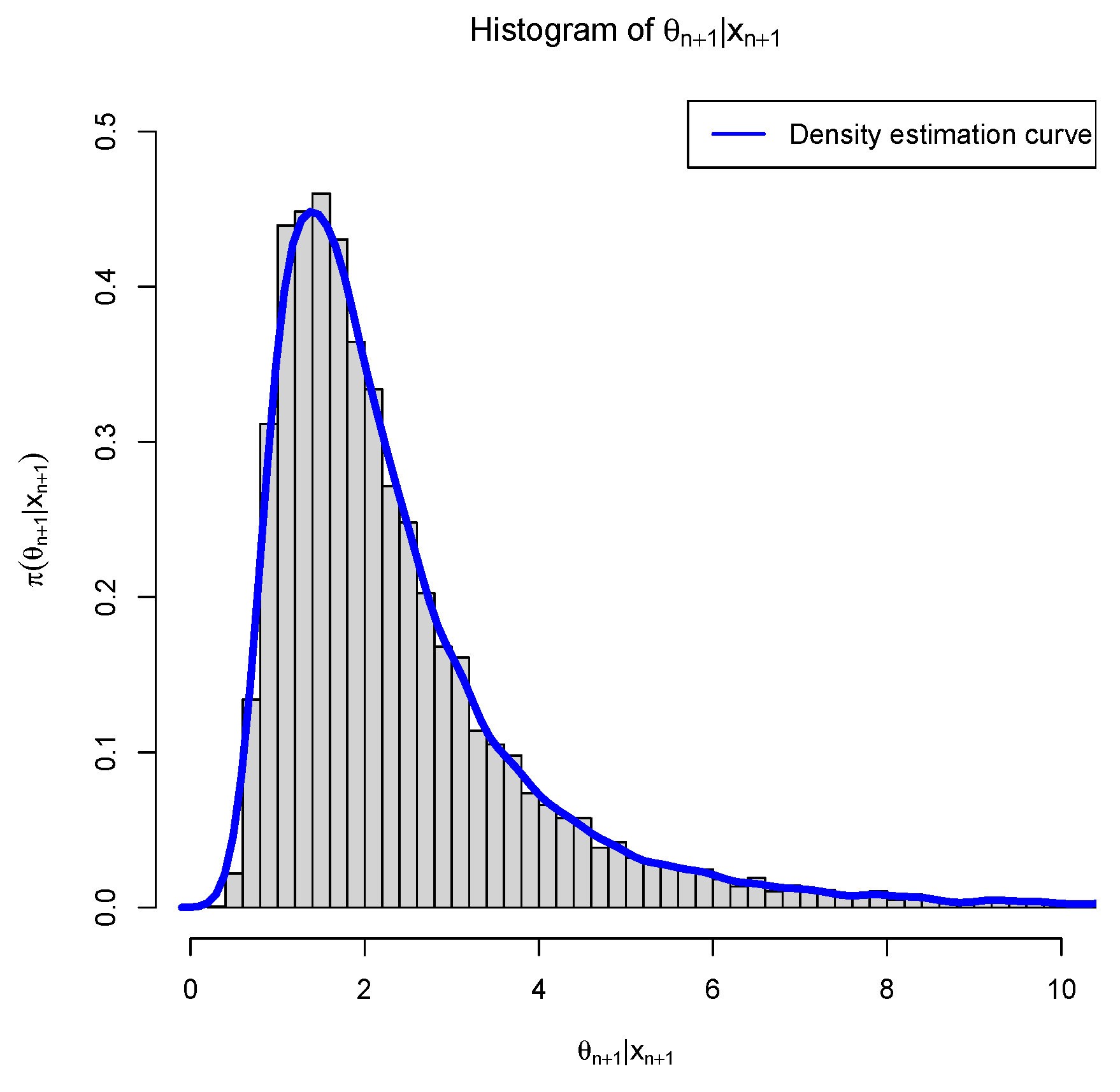

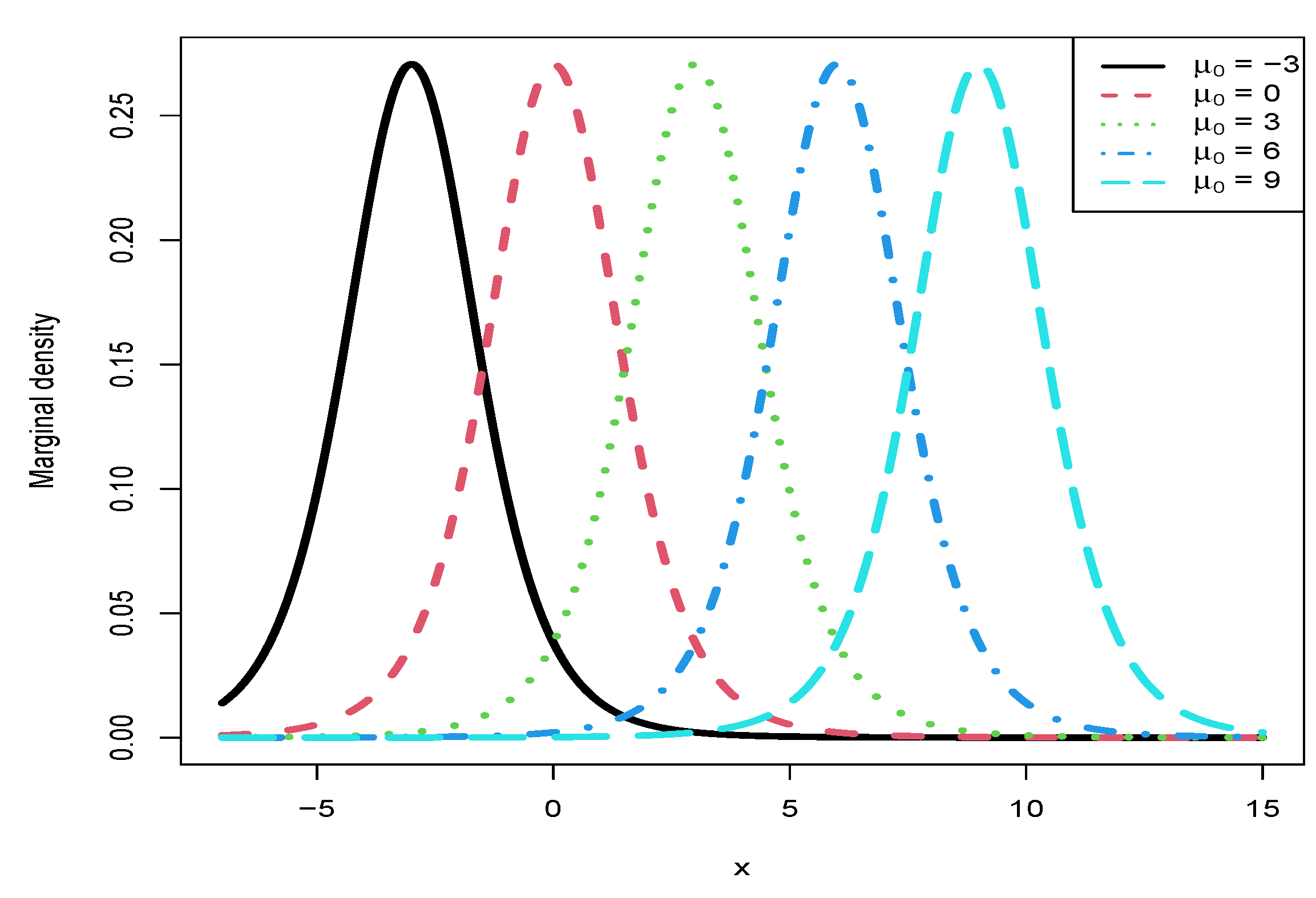

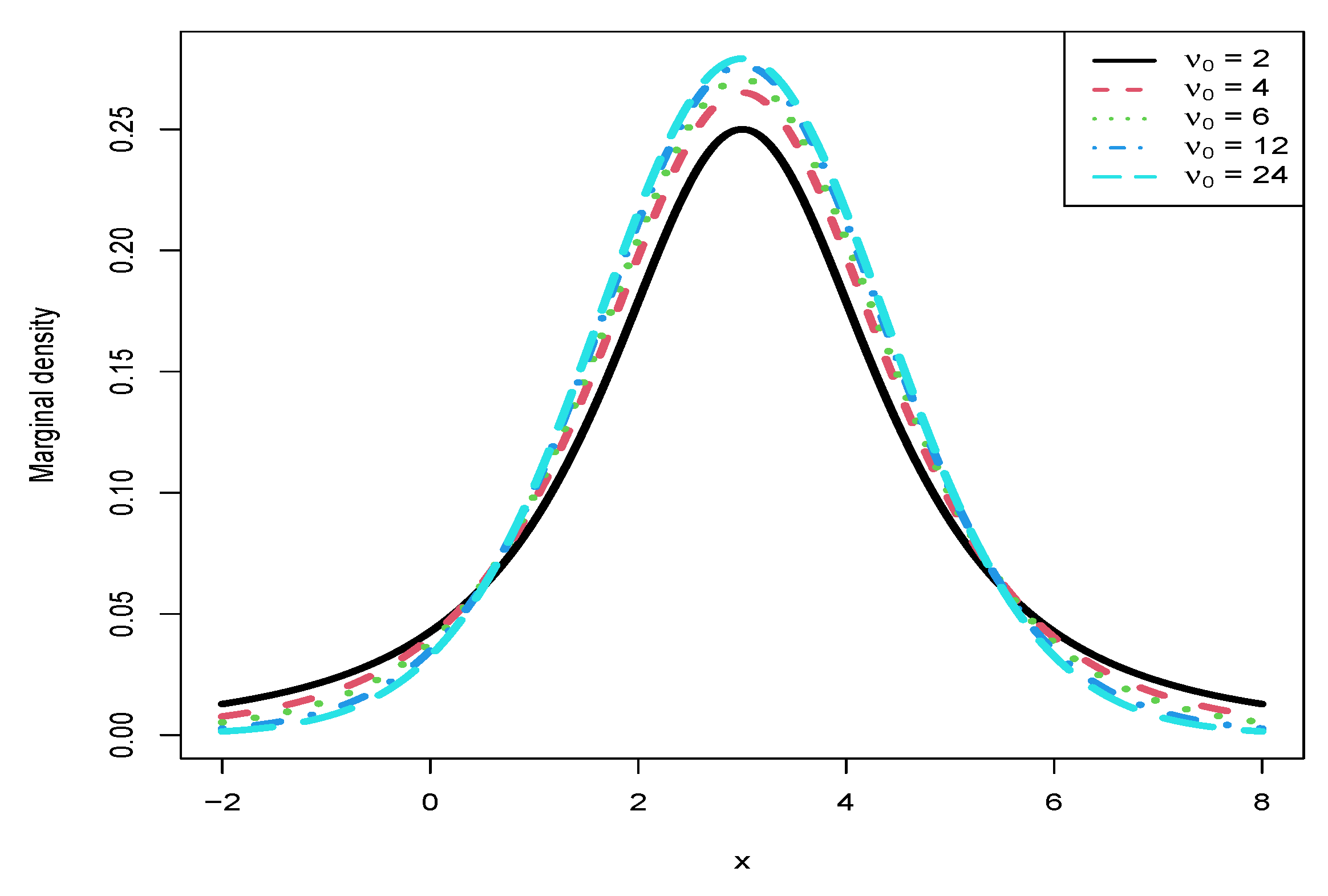

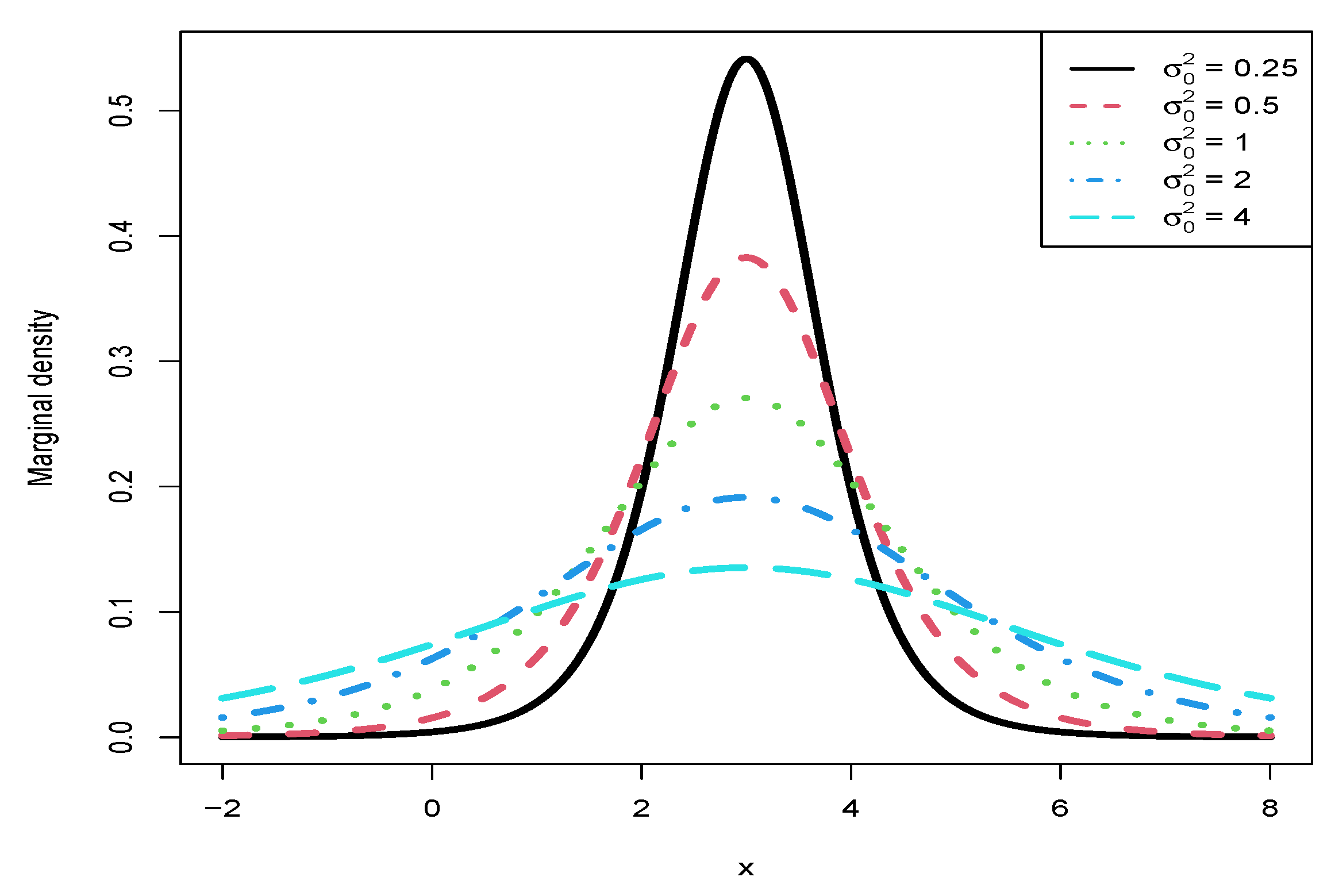

3.5. Marginal Densities for Various Hyperparameters

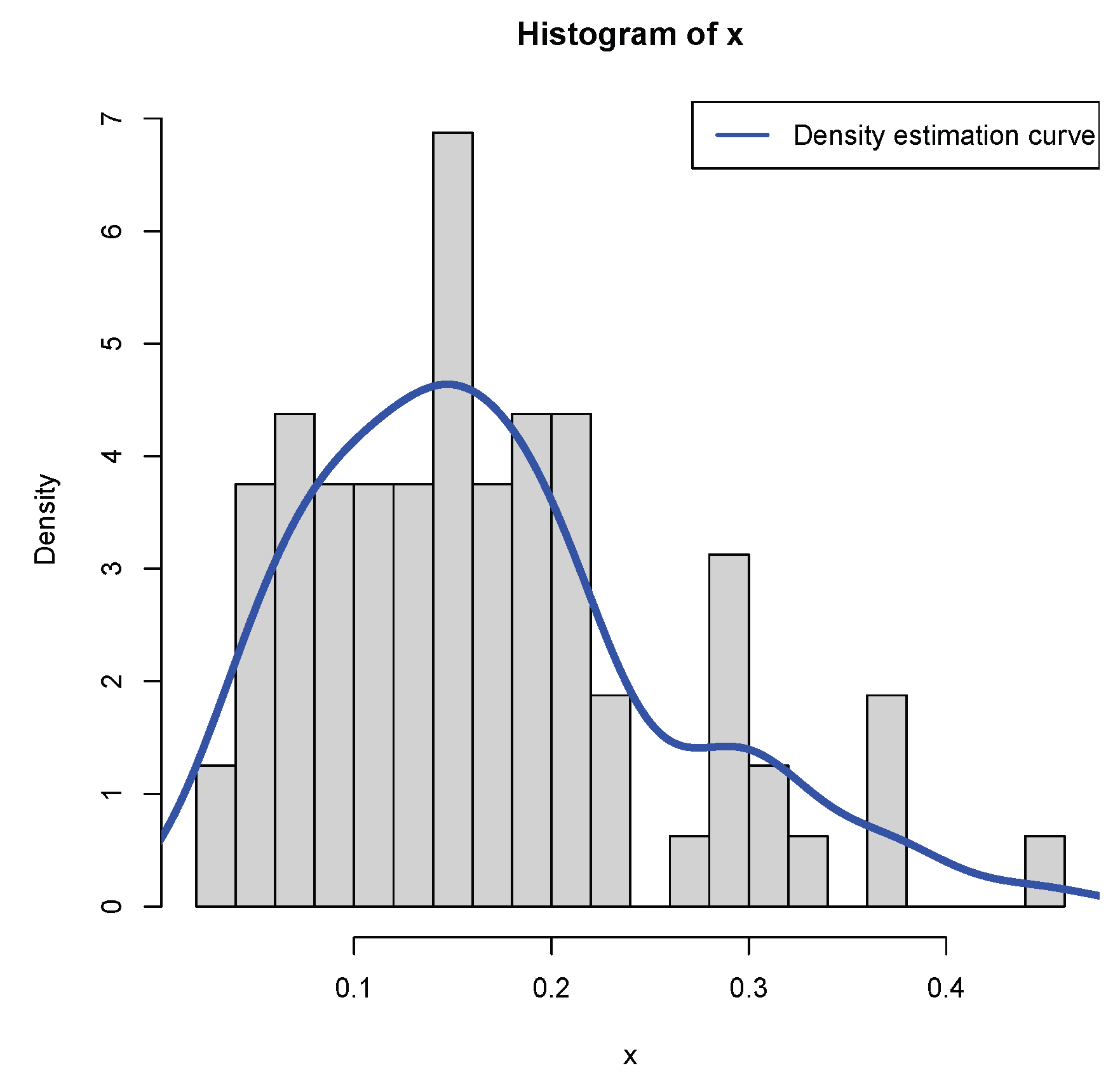

4. A Real Data Example

- The moment estimator of the hyperparameter is equal to the sample mean of the first n observations. It is worth noting that the MLE of the hyperparameter is equal to , which is very close to the moment estimator of the hyperparameter . Furthermore, the moment estimator and the MLE of the hyperparameter are also very similar, and they are close to . However, the moment estimator and the MLE of the hyperparameter are quite different. This does not mean that the moment estimator and the MLE are not consistent estimators of the hyperparameter , nor mean that the hierarchical normal and normal-inverse-gamma model (2) does not fit the real data. For the big difference between the two estimators, the reason is that the sample size is small. Certainly, the MLE of the hyperparameter is more reliable, as guaranteed from the previous figures and tables in the simulations section.

- The KS test is used as a measure of the goodness-of-fit. The p-value of the moment method is , which implies that the distribution with , , and estimated by their moment estimators fits the sample well. Moreover, the p-value of the MLE method is , which implies that the distribution with , , and estimated by their MLEs fits the sample even better. Comparing the moment method and the MLE method, we observe that the D value of the MLEs is smaller, and the p-value of the MLEs is larger, which means that the distribution with the hyperparameters , , and estimated by the MLEs has a better fit to the sample than that estimated by the moment estimators.

-

When the hyperparameters are estimated by the MLE method, we see thatand

- The mean of X (the poverty level data) is estimated by . The variance of X is estimated by . It is useful to note that the mean and variance of X by the two methods are very similar, although the estimators of the hyperparameters are very different. Moreover, it is worth mentioning thatfor the MLE method. For the moment method, the mean and variance of X are similar. Hence, the variance of X is very small, not large!

5. Conclusions and Discussions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Proofs of Theorems

Appendix A.1. The Proof of Theorem 1

Appendix A.2. The Proof of Theorem 2

Appendix A.3. The Proof of Theorem 3

- (C1).

- We observe , where are iid.

- (C2).

- The parameter is identifiable; that is, if , then .

- (C3).

- The densities have common support, and is differentiable in , , and .

- (C4).

- The parameter space contains an open set of which the true parameter value is an interior point.

References

- Berger, JO. Statistical Decision Theory and Bayesian Analysis, 2nd edition; Springer: New York, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Maritz, JS; Lwin, T. Empirical Bayes Methods, 2nd edition; Chapman & Hall: London, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Carlin, BP; Louis, A. Bayes and Empirical Bayes Methods for Data Analysis, 2nd edition; Chapman & Hall: London, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Robbins, H. An empirical bayes approach to statistics. Proceedings of Third Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability, vol. 1, University of California Press, 1955.

- Robbins, H. The empirical bayes approach to statistical decision problems. Annals of Mathematical Statistics 1964, 35, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robbins, H. Some thoughts on empirical bayes estimation. Annals of Statistics 1983, 1, 713–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deely, JJ; Lindley, DV. Bayes empirical bayes. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1981, 76, 833–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, C. Parametric empirical bayes inference: Theory and applications. Journal of the American Statistical Association 1983, 78, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maritz, JS; Lwin, T. Assessing the performance of empirical bayes estimators. Annals of the Institute of Statistical Mathematics 1992, 44, 641–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlin, BP; Louis, A. Empirical bayes: Past, present and future. Journal of the American Statistical Association 2000, 95, 1286–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pensky, M. Locally adaptive wavelet empirical bayes estimation of a location parameter. Annals of the Institute of Statistical Mathematics 2002, 54, 83–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coram, M; Tang, H. Improving population-specific allele frequency estimates by adapting supplemental data: An empirical bayes approach. The Annals of Applied Statistics 2007, 1, 459–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efron, B. Tweedie’s formula and selection bias. Journal of the American Statistical Association 2011, 106, 1602–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Houwelingen, HC. The role of empirical bayes methodology as a leading principle in modern medical statistics. Biometrical Journal 2014, 56, 919–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, M; Kubokawa, T; Kawakubo, Y. Benchmarked empirical bayes methods in multiplicative area-level models with risk evaluation. Biometrika 2015, 102, 647–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satagopan, JM; Sen, A; Zhou, Q; Lan, Q; Rothman, N; Langseth, H; Engel, LS. Bayes and empirical bayes methods for reduced rank regression models in matched case-control studies. Biometrics 2016, 72, 584–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R; Mess, R; Walker, SG. Empirical bayes posterior concentration in sparse high-dimensional linear models. Bernoulli 2017, 23, 1822–1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikulich-Gilbertson, SK; Wagner, BD; Grunwald, GK; Riggs, PD; Zerbe, GO. Using empirical bayes predictors from generalized linear mixed models to test and visualize associations among longitudinal outcomes. Statistical Methods in Medical Research 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, YY; Rong, TZ; Li, MM. The empirical bayes estimators of the mean and variance parameters of the normal distribution with a conjugate normal-inverse-gamma prior by the moment method and the mle method. Communications in Statistics-Theory and Methods 2019, 48, 2286–2304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, YY; Wang, ZY; Duan, ZM; Mi, W. The empirical bayes estimators of the parameter of the poisson distribution with a conjugate gamma prior under stein’s loss function. Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation 2019, 89, 3061–3074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J; Zhang, YY; Sun, Y. The empirical bayes estimators of the rate parameter of the inverse gamma distribution with a conjugate inverse gamma prior under stein’s loss function. Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation 2021, 91, 1504–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, MQ; Zhang, YY; Sun, Y; Sun, J; Rong, TZ; Li, MM. The empirical bayes estimators of the probability parameter of the beta-negative binomial model under zhang’s loss function. Chinese Journal of Applied Probability and Statistics 2021, 37, 478–494. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Y; Zhang, YY; Sun, J. The empirical bayes estimators of the parameter of the uniform distribution with an inverse gamma prior under stein’s loss function. Communications in Statistics-Simulation and Computation 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, YY; Zhang, YY; Wang, ZY; Sun, Y; Sun, J. The empirical bayes estimators of the variance parameter of the normal distribution with a conjugate inverse gamma prior under stein’s loss function. Communications in Statistics-Theory and Methods 2024, 53, 170–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, SS; Tang, YC. Bayesian Statistics, 2nd edition; China Statistics Press: Beijing, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, MH. Bayesian Statistics Lecture. Statistics Graduate Summer School, School of Mathematics and Statistics, Northeast Normal University, Changchun, China July 2014.

- James, W; Stein, C. Estimation with quadratic loss. Proceedings of the Fourth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability 1961, 1, 361–380. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, YY. The bayes rule of the variance parameter of the hierarchical normal and inverse gamma model under stein’s loss. Communications in Statistics-Theory and Methods 2017, 46, 7125–7133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, YH; Song, WH; Zhou, MQ; Zhang, YY. The bayes posterior estimator of the variance parameter of the normal distribution with a normal-inverse-gamma prior under stein’s loss. Chinese Journal of Applied Probability and Statistics 2018, 34, 551–564. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, YY; Xie, YH; Song, WH; Zhou, MQ. Three strings of inequalities among six bayes estimators. Communications in Statistics-Theory and Methods 2018, 47, 1953–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Good, IJ. Turing’s anticipation of empirical bayes in connection with the cryptanalysis of the naval enigma. Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation 2000, 66(2), 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noma, H; Matsui, S. Empirical bayes ranking and selection methods via semiparametric hierarchical mixture models in microarray studies. Statistics in Medicine 2013, 32(11), 1904–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, W; Jeong, KS; Xie, Y; Khodursky, A. A nonparametric empirical bayes approach to joint modeling of multiple sources of genomic data. Statistica Sinica 2008, 18(2), 709–729. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q; Xu, Z; Lai, Y. An empirical bayes approach for the identification of long-range chromosomal interaction from hi-c data. Statistical Applications in Genetics and Molecular Biology 2021, 20(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soloff, JA; Guntuboyina, A; Sen, B. Multivariate, heteroscedastic empirical bayes via nonparametric maximum likelihood. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B-Statistical Methodology 2024, 87(1), 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler D, Murdoch D, others. rgl: 3D Visualization Using OpenGL 2017. URL https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rgl, r package version 0.98.1.

- Zhang, YY; Zhou, MQ; Xie, YH; Song, WH. The bayes rule of the parameter in (0,1) under the power-log loss function with an application to the beta-binomial model. Journal of Statistical Computation and Simulation 2017, 87, 2724–2737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conover, WJ. Pages 295–301 (one-sample kolmogorov test), 309–314 (two-sample smirnov test). In Practical Nonparametric Statistics; John Wiley & Sons: New York, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Durbin, J. Distribution Theory for Tests Based on the Sample Distribution Function; SIAM: Philadelphia, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Marsaglia, G; Tsang, WW; Wang, JB. Evaluating kolmogorov’s distribution. Journal of Statistical Software 2003, 8(18). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, DS; Kaishev, VK; Tan, S. Computing the kolmogorov-smirnov distribution when the underlying cdf is purely discrete, mixed or continuous 2017; City, University of London Institutional Repository.

- Aldirawi, H; Yang, J; Metwally, AA. Identifying appropriate probabilistic models for sparse discrete omics data. In IEEE EMBS International Conference on Biomedical and Health Informatics (BHI); IEEE, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Santitissadeekorn, N; Lloyd, DJB; Short, MB; Delahaies, S. Approximate filtering of conditional intensity process for poisson count data: Application to urban crime. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis 2020, 144, 1–14, Document Number 106850. [Google Scholar]

- Berger, JO. The case for objective bayesian analysis. Bayesian Analysis 2006, 1, 385–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, JO; Bernardo, JM; Sun, DC. Overall objective priors. Bayesian Analysis 2015, 10, 189–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024; Available online: http://www.R-project.org/.

- Casella, G; Berger, RL. Statistical Inference, 2nd edition; Pacific Grove: Duxbury, 2002. [Google Scholar]

| Moment estimators | MLEs | |

| Moment estimators | MLEs | ||||||

| n | |||||||

| 1e4 | |||||||

| 2e4 | |||||||

| 4e4 | |||||||

| 8e4 | |||||||

| 16e4 | |||||||

| 1e4 | |||||||

| 2e4 | |||||||

| 4e4 | |||||||

| 8e4 | |||||||

| 16e4 | |||||||

| 1e4 | |||||||

| 2e4 | |||||||

| 4e4 | |||||||

| 8e4 | |||||||

| 16e4 | |||||||

| 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||||||

| Moment method | MLE method | ||

| Estimators of | |||

| the hyperparameters | |||

| Goodness-of-fit | D | ||

| of the model | p-value | ||

| Empirical Bayes estimators | |||

| and PESLs | |||

| Mean and variance of | |||

| the poverty level data |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).