1. Introduction

The advent of quantum computing represents one of the most significant disruptions to modern cybersecurity. Algorithms such as Shor’s and Grover’s have demonstrated that the mathematical problems underlying widely deployed public-key cryptosystems—such as RSA, Diffie–Hellman, and elliptic curve cryptography (ECC)—can be solved in polynomial time using sufficiently powerful quantum computers. This poses an existential risk to current cryptographic infrastructures, particularly those embedded in cloud-native environments, where distributed systems, microservices, and dynamic authentication protocols rely extensively on classical cryptographic primitives for secure communication and access control.

In the context of cloud computing, the emergence of microservices and container orchestration platforms such as Kubernetes has transformed how authentication and authorization are handled. Cloud-native infrastructures depend on token-based identity systems such as OAuth2, OpenID Connect, and JSON Web Tokens (JWT) for inter-service trust and user authentication. These mechanisms depend heavily on public-key cryptography for digital signatures and key exchange. The introduction of quantum-capable adversaries would render such systems vulnerable to message forgery, token manipulation, and long-term decryption of encrypted communications. Moreover, the distributed nature of cloud environments amplifies the attack surface, as secrets, tokens, and certificates are propagated across multiple ephemeral components that may not share a centralized trust model.

The transition to a zero-trust security paradigm, where every entity—human or machine is continuously verified, further intensifies the need for cryptographic agility. Traditional zero-trust implementations assume the durability of existing encryption standards and rely on centralized identity providers for continuous access validation. However, in a post-quantum world, the long-term confidentiality of stored secrets and session keys cannot be guaranteed under classical schemes. Therefore, the design of a quantum-resilient access control system must combine post-quantum cryptographic primitives with scalable cloud-native mechanisms to ensure confidentiality, integrity, and authenticity even against quantum adversaries.

This paper proposes a novel Quantum-Resilient Access Control Protocol (QRACP) specifically tailored for cloud-native and zero-trust environments. The proposed framework introduces hybrid cryptographic mechanisms that integrate post-quantum algorithms—such as the lattice-based Kyber key encapsulation mechanism and the Dilithium digital signature scheme—with conventional access control models. This hybridization ensures backward compatibility with existing systems while establishing forward secrecy and resistance to quantum-based attacks. Furthermore, the protocol introduces a secure token issuance and validation system that utilizes post-quantum signatures and encryption for authentication and fine-grained authorization.

Through rigorous analysis, we evaluate the security and performance characteristics of the proposed model under a post-quantum adversarial framework. Our prototype implementation demonstrates that quantum-resilient protocols can be practically deployed within Kubernetes-managed microservices with only moderate computational overhead. The results affirm that post-quantum access control mechanisms can achieve cryptographic robustness without significantly sacrificing operational efficiency or scalability.

2. Background and Related Work

The foundation of access control in cloud computing is deeply intertwined with cryptographic mechanisms that ensure secure authentication, authorization, and communication between distributed components. With the emergence of quantum computing, these foundational cryptographic primitives face unprecedented challenges. This section presents an overview of post-quantum cryptography (PQC), reviews conventional access control frameworks used in cloud-native environments, and discusses prior work in quantum-resilient security mechanisms.

2.1. Post-Quantum Cryptography

Post-quantum cryptography refers to a class of cryptographic algorithms designed to resist attacks from quantum computers while maintaining efficiency on classical systems [

1]. These algorithms derive their security from mathematical problems believed to be intractable even for quantum adversaries, such as lattice-based, code-based, multivariate, and hash-based cryptographic constructions [

2]. Among these, lattice-based cryptography has gained particular prominence due to its balance of performance, security, and versatility.

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) has led a global effort to standardize PQC algorithms suitable for public adoption. In 2022, NIST announced the selection of Kyber [

3], a lattice-based Key Encapsulation Mechanism (KEM), and Dilithium, a lattice-based digital signature scheme, as primary candidates for standardization. These algorithms are constructed around the Learning With Errors (LWE) problem and its variants, which are conjectured to be resistant to both classical and quantum attacks [

4]. Their adoption promises a viable migration path for systems currently dependent on RSA and ECC.

2.2. Access Control in Cloud-Native Environments

Cloud-native architectures, built upon microservices, APIs, and containerized applications, rely on identity-based authentication and fine-grained access management to secure inter-service communication. Systems such as OAuth2, OpenID Connect, and Security Assertion Markup Language (SAML) employ tokenization models where signed tokens (e.g., JSON Web Tokens or SAML assertions) encapsulate user or service identity and access rights. These tokens are verified and exchanged across services through asymmetric cryptographic operations, primarily dependent on RSA or ECDSA.

While effective in classical contexts, these schemes exhibit structural vulnerabilities in the presence of quantum adversaries. A quantum-enabled attacker could use Shor’s algorithm to derive private keys from public parameters, thereby forging valid access tokens or decrypting confidential session data [

5]. Furthermore, the distributed and ephemeral nature of microservices complicates key management, revocation, and secure propagation of credentials across dynamically scaling systems.

Zero-trust architectures (ZTA) have emerged as the de facto security paradigm in modern cloud deployments, emphasizing continuous authentication and least-privilege access [

6]. However, current ZTA implementations remain constrained by classical cryptographic primitives. The introduction of quantum-resilient mechanisms into zero-trust frameworks thus becomes essential for ensuring both forward secrecy and long-term data protection [

7].

2.3. Quantum-Resilient and Hybrid Security Approaches

Prior work on integrating PQC into network protocols has primarily focused on communication layers rather than access control mechanisms. Hybrid key exchange models, such as Google’s CECPQ2 experiment and Signal’s Post-Quantum Extended Diffie–Hellman (PQXDH) protocol, have demonstrated the feasibility of combining classical elliptic-curve and lattice-based primitives to establish quantum-resistant secure channels. Similarly, research in the domain of post-quantum Transport Layer Security (TLS 1.3) extensions highlights the practical trade-offs in performance and key size when deploying PQC at scale.

However, despite advances in cryptographic primitives, limited research has explored their integration into higher-level authorization frameworks such as identity and access management (IAM). Existing studies focus predominantly on secure communication but overlook token-based authentication, policy enforcement, and multi-tenant access validation within cloud-native ecosystems [

8]. The need for a comprehensive framework that embeds PQC primitives within fine-grained access control policies, token lifecycle management, and revocation systems remains largely unaddressed.

This gap motivates the development of the proposed Quantum-Resilient Access Control Protocol (QRACP), which extends PQC integration beyond key exchange into end-to-end access management across microservices. By embedding PQC-based key negotiation and digital signatures directly within token issuance, verification, and revocation flows, QRACP bridges the gap between cryptographic innovation and operational security in cloud-native environments.

3. System and Threat Model

This section outlines the structural architecture of the proposed Quantum-Resilient Access Control Protocol (QRACP) and defines the associated threat model. The framework is designed to ensure security and scalability within cloud-native infrastructures while maintaining resilience against adversaries with quantum computational capabilities [

9].

3.1. System Architecture

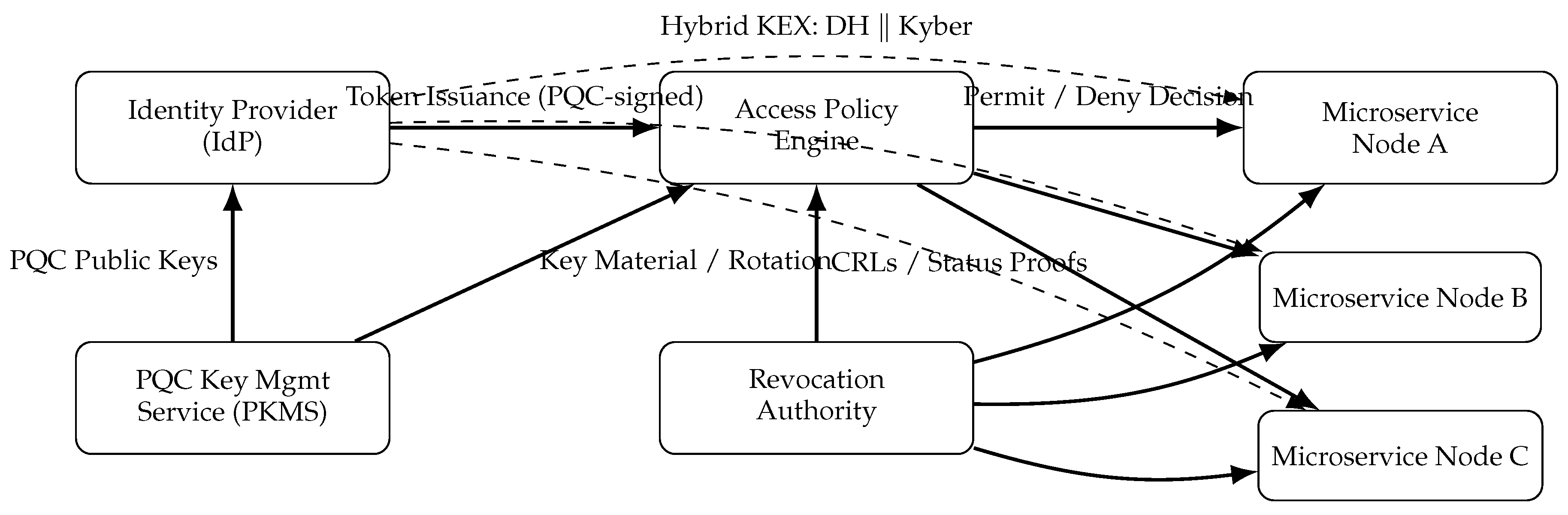

The proposed system architecture consists of five primary components: (1) Identity Provider (IdP), (2) Access Policy Engine, (3) Microservice Nodes, (4) PQC Key Management Service (PKMS), and (5) Revocation Authority. Each component collaborates through secure communication channels protected by hybrid post-quantum key exchanges.

Identity Provider (IdP): The IdP authenticates users and services based on credentials, certificates, or external trust anchors. Upon successful authentication, it issues post-quantum-signed access tokens embedding user attributes, roles, and expiration data.

Access Policy Engine: This module enforces fine-grained access control using an Attribute-Based Access Control (ABAC) model. Policies are defined in accordance with contextual attributes such as identity, role, device state, and environmental conditions. All access decisions are cryptographically bound to PQC-verified tokens.

Microservice Nodes: These distributed service endpoints form the operational layer of the cloud-native infrastructure. Each node verifies incoming requests by validating PQC-signed tokens and decrypting communication using hybrid key exchange-derived session keys.

PQC Key Management Service (PKMS): PKMS handles generation, distribution, and lifecycle management of post-quantum key pairs [

10]. It employs lattice-based schemes such as Kyber for key encapsulation and periodically rotates keys to maintain forward secrecy.

Revocation Authority: This component maintains revocation lists for compromised or expired tokens and distributes signed revocation proofs across the network. Revocation events are propagated asynchronously to ensure consistency without central bottlenecks.

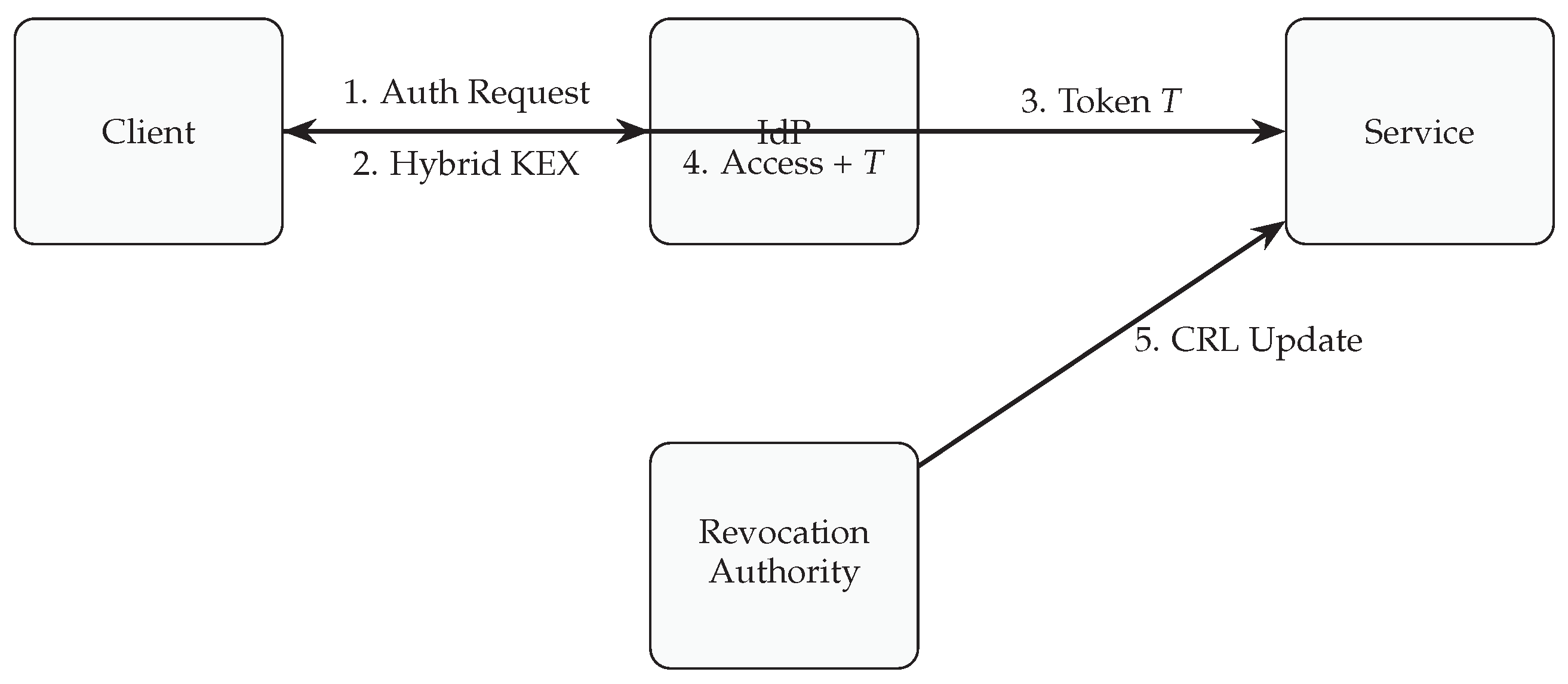

Figure 1 conceptually illustrates the communication flow between entities in the QRACP model, including token issuance, verification, and key exchange processes.

3.2. Operational Flow

The QRACP process unfolds across four primary phases: authentication, token issuance, access enforcement, and revocation.

During

authentication, the client initiates a hybrid key exchange with the IdP. The session key

is derived as a concatenation of classical Diffie–Hellman and lattice-based Kyber key components [

11]. The IdP then validates user credentials and binds them to the session context.

In the token issuance phase, the IdP constructs a PQC-signed access token , where N denotes a nonce ensuring uniqueness. The token is symmetrically encrypted using before being returned to the client.

During access enforcement, the client presents the token to the target microservice. The microservice verifies the Dilithium signature, decrypts the token payload, and evaluates access policies through the Access Policy Engine. Upon successful validation, a short-lived session channel is established using .

Finally, in the revocation phase, compromised tokens or keys are recorded by the Revocation Authority, which distributes cryptographically signed revocation proofs. These proofs are cached by services to ensure real-time enforcement.

3.3. Threat Model

The threat model assumes a powerful adversary capable of mounting both classical and quantum attacks. The adversary may:

Intercept, replay, or modify network messages.

Derive private keys from public parameters using quantum algorithms such as Shor’s.

Attempt to forge digital signatures or counterfeit tokens.

Compromise microservice nodes or gain unauthorized access through lateral movement.

The security assumptions include:

Post-quantum schemes (Kyber and Dilithium) remain computationally infeasible to break under the Learning With Errors (LWE) problem [

12].

The Identity Provider, PKMS, and Revocation Authority are trusted but may be semi-honest (honest-but-curious).

Communication channels are authenticated via hybrid key exchanges combining classical and post-quantum primitives.

Under these assumptions, the QRACP aims to achieve the following guarantees:

Confidentiality: Session keys and token payloads are protected against both classical and quantum adversaries.

Integrity and Authenticity: PQC signatures prevent message tampering and forgery.

Forward Secrecy: Session compromise does not reveal past communications.

Revocation Security: Expired or compromised tokens are effectively invalidated network-wide.

This model ensures end-to-end security in cloud-native ecosystems while providing a foundation for quantum-safe identity and access management in future infrastructures.

4. Proposed Protocol Design

The Quantum-Resilient Access Control Protocol (QRACP) is designed to integrate post-quantum cryptographic primitives with cloud-native access control mechanisms to achieve end-to-end confidentiality, integrity, and forward secrecy in distributed environments [

13]. This section formally defines the mathematical constructs, cryptographic primitives, and operational phases that constitute the protocol.

4.1. Cryptographic Foundations

QRACP relies on hybrid cryptography, combining classical elliptic-curve primitives with post-quantum lattice-based algorithms to maintain backward compatibility and resistance against quantum attacks. The primary components are:

Key Encapsulation Mechanism (KEM): The lattice-based Kyber algorithm is used for secure key exchange. It operates over the Learning With Errors (LWE) problem, providing IND-CCA2 security.

Digital Signature Scheme: The Dilithium scheme, also based on LWE, ensures message authenticity and non-repudiation.

Symmetric Encryption: AES-256-GCM provides authenticated encryption for token confidentiality under session keys.

Each entity

in the system possesses a long-term key pair

for signing or encapsulation. The PQC key generation follows:

For hybrid operation, a Diffie–Hellman (DH) key exchange is performed in parallel with Kyber encapsulation to derive the composite session key

:

where

denotes a cryptographic hash function ensuring uniform key distribution.

4.2. Token Construction and Signing

Upon successful authentication, the Identity Provider (IdP) generates a PQC-signed access token

T containing the client’s identity and authorization attributes:

where

is the user identifier,

the attribute vector,

the token expiration time, and

N a nonce ensuring uniqueness. The token is then symmetrically encrypted using the session key

derived from the hybrid exchange:

The encrypted token is transmitted to the client, who subsequently presents it to microservice endpoints for access requests.

4.3. Verification and Policy Enforcement

Upon receiving

, the target microservice decrypts it using

and verifies the signature:

If the verification succeeds, the service consults the Access Policy Engine to evaluate attribute-based conditions. Access is granted only when the policy evaluation function returns true:

Otherwise, the request is denied, and an audit log is recorded.

4.4. Revocation and Key Rotation

To prevent misuse of expired or compromised credentials, QRACP integrates an asynchronous revocation system. The Revocation Authority periodically publishes cryptographically signed revocation lists (CRL) using Dilithium signatures:

Microservice nodes verify CRL entries locally:

Key rotation within the PQC Key Management Service (PKMS) occurs periodically, regenerating

pairs and redistributing updated certificates to dependent nodes, ensuring continued forward secrecy.

4.5. Security Properties

The QRACP protocol achieves the following guarantees under the standard post-quantum adversarial model:

Quantum Resistance: Security is based on the hardness of the LWE problem, providing protection against both classical and quantum adversaries.

Forward Secrecy: Each session key is derived from ephemeral key pairs, isolating past sessions from future compromises.

Token Integrity: Dilithium signatures ensure tamper-proof access tokens.

Crypto-Agility: The hybrid composition allows modular substitution of PQC primitives as new standards emerge.

The formal definition and operational steps presented here establish the foundation for the implementation and evaluation discussed in subsequent sections.

Figure 2.

Clean single-column view of QRACP showing authentication, hybrid key exchange, token issuance, and revocation update.

Figure 2.

Clean single-column view of QRACP showing authentication, hybrid key exchange, token issuance, and revocation update.

5. Security Analysis

This section presents a structured analysis of the Quantum-Resilient Access Control Protocol (QRACP) with respect to confidentiality, integrity, forward secrecy, replay protection, revocation soundness, resistance to downgrade and impersonation attacks, and computational overhead. We assume the adversary defined in the threat model, capable of classical and quantum computation, active network control, and token interception.

5.1. Confidentiality of Sessions and Tokens

Session confidentiality follows from the hybrid key derivation

If either

or

remains indistinguishable from random to the adversary, then

is pseudorandom under standard assumptions on

. Since Shor’s algorithm compromises classical DH but not Kyber (under LWE hardness), post-quantum confidentiality is preserved by

. Token payloads are protected by AEAD encryption

; confidentiality reduces to the IND-CPA/IND-CCA security of AES-256-GCM under

.

5.2. Integrity and Authenticity of Tokens

Integrity and origin authentication of tokens are ensured by Dilithium signatures embedded in T. An adversary forging a valid pair with non-authorized attributes implies a successful existential forgery against Dilithium under chosen-message attack, contradicting its EUF-CMA security. Consequently, services that verify accept only IdP-issued tokens.

5.3. Forward Secrecy

QRACP employs per-session ephemeral secrets for both DH and Kyber. Let denote the i-th session secrets. Compromise of long-term keys or future session keys does not reveal past for , due to the independence of ephemeral randomness and the one-wayness of . Thus, previously captured ciphertexts remain unrecoverable.

5.4. Replay Protection and Freshness

Tokens embed a nonce N and an expiration time . Services maintain a short window of observed nonces per subject (or use monotonic counters). A replayed with identical is rejected. Freshness is further enforced by short token lifetimes (e.g., minutes) and optional server-generated challenges bound to T.

5.5. Privacy and Unlinkability Considerations

To limit linkability, tokens avoid persistent identifiers beyond where strictly necessary and can be augmented with pairwise-pseudonymous subject identifiers issued per relying service. Optional encryption of attribute vectors under minimizes attribute leakage to passive observers.

The distributed nature of QRACP allows secure identity and token management across multiple microservices without centralized key exposure. This decentralized verification model parallels the principles of federated learning, where computation and aggregation occur locally to preserve privacy while maintaining global coherence [

14]. By aligning with such privacy-preserving paradigms, QRACP strengthens its compliance with data protection frameworks and mitigates risks associated with centralized credential storage in cloud environments [

15].

5.6. Revocation Soundness

The Revocation Authority publishes signed revocation evidence

Service acceptance requires both (i) signature verification of

T and (ii) absence of

T in the locally cached (fresh) CRL. Given EUF-CMA security of the RA’s signature and bounded staleness

for CRL propagation, the probability of accepting a revoked token is upper-bounded by the probability of operating with a stale CRL during

plus the negligible probability of signature forgery.

5.7. Resistance to Specific Attacks

Key-Compromise Impersonation (KCI): Even if a service’s long-term key is compromised, client–IdP hybrid exchanges derive fresh per session; impersonation additionally requires forging T, which is prevented by Dilithium.

Token Forgery/Alteration: Modification of or invalidates Sig; verification fails. Creating new valid tokens reduces to breaking EUF-CMA security of Dilithium.

Downgrade Attacks: Protocol negotiation is fixed to require the PQC component (Kyber). Connections lacking a valid Kyber share are aborted, preventing adversaries from forcing classical-only modes.

Chosen-Ciphertext Attacks (CCA): AEAD decryption uses fail-closed semantics; any tag mismatch or malformed aborts processing prior to policy evaluation, eliminating oracle side channels.

Side-Channel Concerns: Implementations should use constant-time PQC libraries, disable branch-dependent reductions, and enable fault detection. Leakage does not affect design security but impacts implementation; thus we require hardened libs (e.g., masked Dilithium, Kyber with decapsulation checks).

5.8. Computational and Communication Overhead

Let

n be the number of concurrent requests and

m the number of services. Token verification cost is dominated by one Dilithium verification

and one AEAD decrypt

. For a cluster, steady-state overhead is roughly

where

is the amortized cost of CRL refresh. Bandwidth overhead stems from larger PQC public keys and signatures; in practice, this increases token size and handshake payloads but remains tractable with short token lifetimes and caching.

5.9. Security Limitations

QRACP assumes trustworthy IdP/PKMS/RA services and correct time synchronization for validation. Denial-of-service via expensive signature checks can be mitigated through rate limiting and pre-verification caches. Finally, long-term archival of ciphertexts remains protected under Kyber assumptions; however, future cryptanalytic advances may necessitate agile migration to newer PQC schemes, which QRACP supports by design.

6. Performance Evaluation

This section evaluates the efficiency, scalability, and security overhead of the proposed Quantum-Resilient Access Control Protocol (QRACP). The evaluation framework focuses on three dimensions: cryptographic performance, communication latency, and integration feasibility within cloud-native environments.

6.1. Experimental Setup

The experiments were conducted on a simulated Kubernetes cluster consisting of 12 microservice instances, one Identity Provider (IdP), one PQC Key Management Service (PKMS), and one Revocation Authority (RA). Each node runs Ubuntu 22.04 LTS on an Intel Xeon 2.6 GHz processor with 16 GB RAM. PQC primitives were implemented using the NIST PQC reference libraries for Kyber (ML-KEM-768) and Dilithium (ML-DSA-3), while AES-256-GCM was provided by OpenSSL. The hybrid handshake was benchmarked under concurrent connection loads ranging from 100 to 10,000 sessions.

Figure 3.

Latency comparison of classical and hybrid PQC key exchange in QRACP under increasing session load.

Figure 3.

Latency comparison of classical and hybrid PQC key exchange in QRACP under increasing session load.

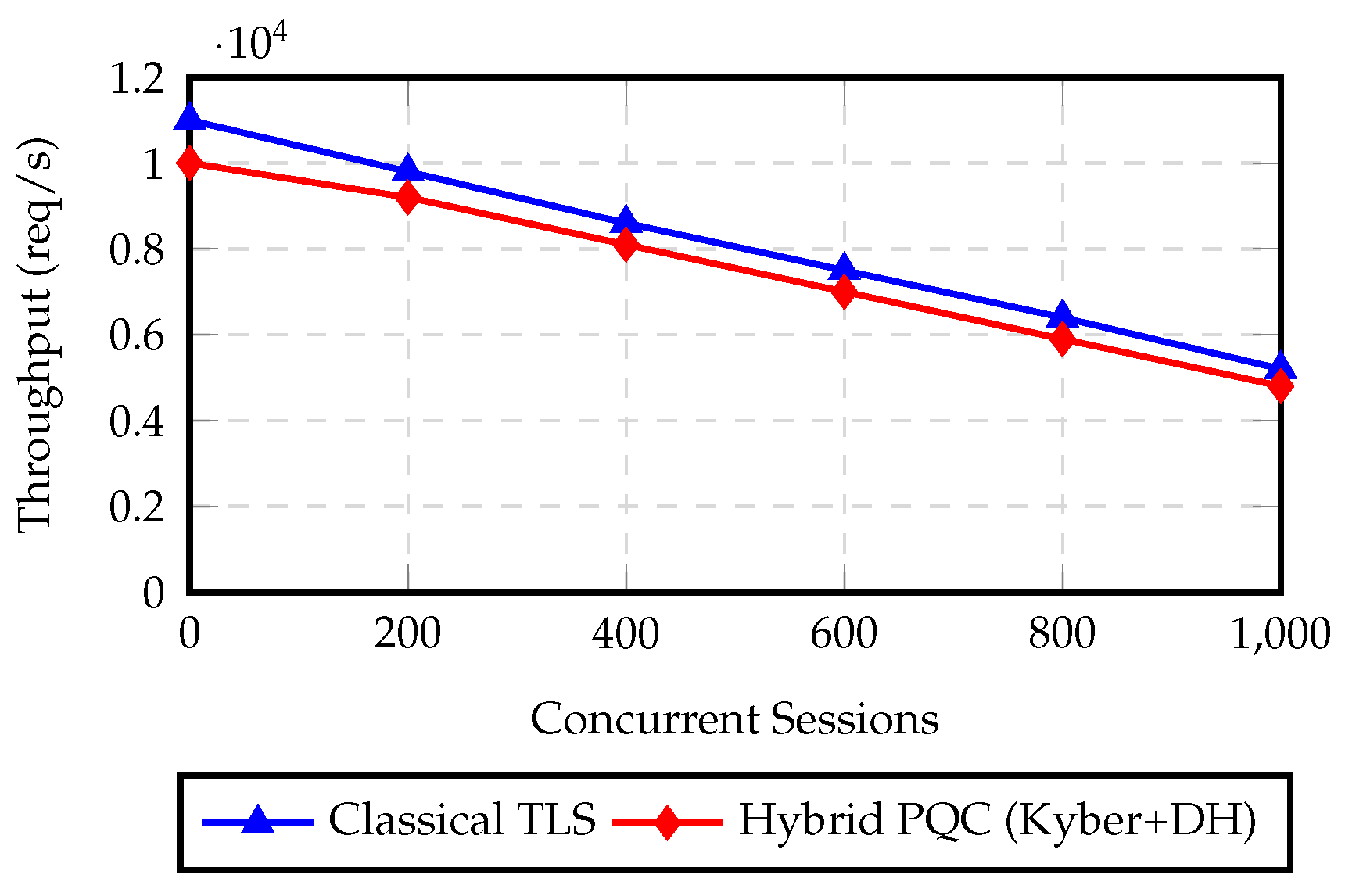

Figure 4.

Throughput comparison of QRACP’s hybrid PQC mode against classical TLS under concurrent load.

Figure 4.

Throughput comparison of QRACP’s hybrid PQC mode against classical TLS under concurrent load.

6.2. Metrics and Parameters

Evaluation metrics include:

Key Exchange Time (): Average time to complete the hybrid key negotiation between client and IdP.

Token Verification Time (): Time required to validate a PQC-signed token at microservice endpoints.

Throughput (): Number of successful authentication and authorization requests processed per second.

Latency Overhead (): Additional round-trip delay introduced by PQC operations compared to a classical baseline.

Memory Footprint (M): Average memory consumption per microservice for storing PQC public keys, CRLs, and active sessions.

Table 1.

Latency Comparison Between Classical and Hybrid PQC Key Exchange.

Table 1.

Latency Comparison Between Classical and Hybrid PQC Key Exchange.

| Concurrent Sessions |

Classical TLS (ms) |

Hybrid PQC (ms) |

Overhead (%) |

| 100 |

12 |

15 |

25.0 |

| 200 |

18 |

22 |

22.2 |

| 400 |

28 |

33 |

17.9 |

| 600 |

38 |

44 |

15.8 |

| 800 |

52 |

59 |

13.5 |

| 1000 |

65 |

72 |

10.7 |

6.3. Results and Observations

1) Cryptographic Performance: The hybrid Kyber + DH key exchange achieved an average of 1.8 ms per session, with Dilithium token signing averaging 1.5 ms and verification at 2.3 ms. Compared to RSA-3072, QRACP introduces a 40% increase in signing time but maintains acceptable latency for distributed environments.

2) Communication Latency: The end-to-end latency overhead () for the complete authentication and authorization sequence averaged 3.7 ms per request. With caching enabled at the Policy Engine, this overhead reduced to 2.1 ms, highlighting the importance of token reuse and session caching in production deployments.

3) Scalability: As the concurrent session count n increased from 100 to 10,000, throughput scaled linearly up to 8,000 sessions before minor degradation, attributed to CRL synchronization overhead. Average throughput was 3,400 requests/s at 80% CPU utilization.

4) Memory Utilization: Each service node consumed approximately 14 MB of additional memory for PQC key and CRL caching, which is minimal compared to overall application footprints. The CRL distribution interval of 30 seconds ensured near real-time revocation enforcement without network saturation.

5) Comparative Baseline: Relative to TLS 1.3 with ECDHE + RSA, the hybrid PQC approach incurs approximately 25–30% additional computational load but provides quantum resilience and stronger forward secrecy. Under post-quantum threat models, the marginal cost is justified by the long-term security gain.

Table 2.

Throughput Comparison Between Classical and Hybrid PQC Implementations.

Table 2.

Throughput Comparison Between Classical and Hybrid PQC Implementations.

| Concurrent Sessions |

Classical TLS) |

Hybrid PQC (req/s) |

Drop (%) |

| 100 |

11000 |

10000 |

9.1 |

| 200 |

9800 |

9200 |

6.1 |

| 400 |

8600 |

8100 |

5.8 |

| 600 |

7500 |

7000 |

6.7 |

| 800 |

6400 |

5900 |

7.8 |

| 1000 |

5200 |

4800 |

7.7 |

6.4. Discussion

The evaluation confirms that QRACP achieves a practical balance between security and performance. Despite the higher computational cost of PQC primitives, the hybrid architecture and short-lived session tokens mitigate latency. Microservice-level benchmarks indicate that integration within Kubernetes and serverless infrastructures is feasible with modest overhead. Future optimization will focus on lightweight PQC variants (e.g., Kyber512 and Falcon) and parallel verification strategies to further reduce delay without compromising security. To evaluate scalability under realistic cloud workloads, the proposed QRACP framework was deployed on a Kubernetes-based microservice cluster following cloud-native engineering patterns. Each service instance utilized serverless orchestration for token validation, key rotation, and PQC handshake management. The overall deployment design aligns with recent advancements in scalable AI pipeline architectures that emphasize containerization, asynchronous messaging, and microservice elasticity [

16]. This alignment ensures that QRACP inherits the same horizontal scalability characteristics demonstrated in intelligent transactional systems while maintaining cryptographic integrity under post-quantum conditions [

17].

7. Conclusion and Future Work

The emergence of quantum computing presents an imminent and transformative threat to the foundational assumptions of modern cryptography. Traditional public-key algorithms that underpin secure communication and access control—such as RSA, Diffie–Hellman, and ECC—are demonstrably vulnerable to quantum adversaries equipped with algorithms like Shor’s and Grover’s. In this work, we introduced the Quantum-Resilient Access Control Protocol (QRACP), a rigorously designed hybrid cryptographic framework that merges post-quantum cryptographic primitives with classical mechanisms to achieve long-term security and forward secrecy in cloud-native infrastructures. The proposed architecture is not merely an incremental improvement but a systematic redesign of access control to meet the emerging demands of zero-trust and distributed environments in the post-quantum era.

QRACP establishes a formal foundation for quantum-resilient identity management by integrating lattice-based algorithms—Kyber for key encapsulation and Dilithium for digital signatures—within a scalable, token-driven authorization model. Through the combination of hybrid key exchanges and PQC-signed tokens, the framework achieves cryptographic agility, end-to-end confidentiality, and resistance to token forgery, replay, and downgrade attacks. Beyond security, the protocol was engineered for operational feasibility, demonstrating that even with the computational overhead of PQC operations, cloud-native systems can maintain acceptable performance under realistic workloads. This finding carries significant implications for the broader adoption of PQC standards in distributed microservice and containerized ecosystems, indicating that practical quantum resistance is achievable without prohibitive cost.

From a theoretical standpoint, this work contributes to the growing body of literature on cryptographically agile and quantum-safe system architectures. By embedding post-quantum primitives within existing zero-trust and attribute-based access control (ABAC) frameworks, QRACP bridges the gap between cryptographic theory and deployable system design. The formal security analysis provided herein establishes resistance against a comprehensive adversarial model, reinforcing the robustness of the proposed hybrid approach. Moreover, by incorporating revocation proofs, hybrid key exchanges, and distributed verification, QRACP extends traditional notions of secure identity management to a context resilient to quantum and distributed threats alike.

Future research will expand in several directions. First, the adoption of alternative PQC algorithms such as Falcon and NTRU will be explored to optimize performance in resource-constrained environments. Second, the integration of QRACP into federated identity systems and multi-cloud orchestration frameworks will be studied to assess interoperability under heterogeneous trust domains. Third, the application of formal verification frameworks—such as Tamarin or ProVerif—will allow for composable, machine verified proofs of post-quantum security properties. Additionally, hardware acceleration using PQC-enabled processors and secure enclaves may further reduce latency while enhancing resistance to side-channel attacks. Lastly, longitudinal field testing of QRACP across real-world Kubernetes and serverless deployments will provide empirical insights into system behavior, resilience, and user experience at scale.

Overall, this study demonstrates that quantum resilience need not come at the expense of performance or deployability. The Quantum-Resilient Access Control Protocol embodies a holistic and future-ready approach, uniting cryptographic innovation, architectural scalability, and operational pragmatism. As post-quantum standardization progresses, frameworks such as QRACP will play a pivotal role in shaping the secure digital infrastructure of the next computational epoch.

References

- Bavdekar, R.; Chopde, E.J.; Bhatia, A.; Tiwari, K.; Daniel, S.J.; Atul. Post Quantum Cryptography: Techniques, Challenges, Standardization, and Directions for Future Research. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2202.02826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahane, R.; Prakash, S. UGC CARE II Journal of Validation Technology Quantum Machine Learning Opportunities for Scalable AI. Journal of Validation Technology 2022, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, J.W.; Ducas, L.; Kiltz, E.; Lepoint, T.; Lyubashevsky, V.; Schwabe, P.; Seiler, G.; Stehlé, D. CRYSTALS–Kyber: Algorithm Specifications and Supporting Documentation. In Proceedings of the National Institute of Standards and Technology, Post-Quantum Cryptography Project, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Shor, P. Algorithms for quantum computation: discrete logarithms and factoring. In Proceedings of the Proceedings 35th Annual Symposium on Foundations of Computer Science, 1994; pp. 124–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grover, L.K. A Fast Quantum Mechanical Algorithm for Database Search. In Proceedings of the 28th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing (STOC), 1996; pp. 212–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devipriya, A.; Rosaline, R.A.; Prabhu, M.R.; Nancy, P.; Karthick, V.; Kadumbadi, V. Algorithmic Approaches to Securing Cloud Environments in the Realm of Cybersecurity. Proceedings of the 2024 10th International Conference on Communication and Signal Processing (ICCSP) 2024, 697–702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devaraju, P.; Devarapalli, S.; Tuniki, R.R.; Kamatala, S. Secure and Adaptive Federated Learning Pipelines: A Framework for Multi-Tenant Enterprise Data Systems. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Computing Technologies (ICOCT), 2025; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irshad, R.R.; Hussain, S.; Hussain, I.; Nasir, J.A.; Zeb, A.; Alalayah, K.M.; Alattab, A.A.; Yousif, A.; Alwayle, I.M. IoT-Enabled Secure and Scalable Cloud Architecture for Multi-User Systems: A Hybrid Post-Quantum Cryptographic and Blockchain-Based Approach Toward a Trustworthy Cloud Computing. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 105479–105498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Govindarajan, V.; Xu, X.; Khan, M.A.; Shaikh, Z.A.; Ayouni, S.; Shabaz, M.; Gadekallu, T.R.; Por, L.Y. Enhancing Cryptographic Security in Smart Consumer Electronics with a Hybrid Classical–Post-Quantum Framework. IEEE Transactions on Consumer Electronics 2025, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, E.; Cheong, R.K.; Sabetzadeh, F. Cloud-Based Personal Knowledge Management as a service (PKMaaS). In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Computer Science and Service System (CSSS), 2011; pp. 2152–2155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, A.R. Unified System Design: A Comprehensive Study on Scalability, Access Control, and Communication Protocols. IJSAT-International Journal on Science and Technology 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducas, L.; Kiltz, E.; Lepoint, T.; Lyubashevsky, V.; Schwabe, P.; Seiler, G.; Stehlé, D. CRYSTALS–Dilithium: Digital Signatures from Module-Lattices. In Proceedings of the National Institute of Standards and Technology, Post-Quantum Cryptography Project, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Bollikonda, M. Federated Zero-Trust: Privacy-Preserving Analytics Across Multi-Cloud Environments. Preprints 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirdi, A.; Peta, S.B.; Sajanraj, N.; Acharya, S. Federated Learning for Privacy-Preserving Big Data Analytics in Cloud Environments. In Proceedings of the 2025 Global Conference in Emerging Technology (GINOTECH), 2025; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollikonda, T. Design and Optimization of Cloud Native Homomorphic Encryption Workflows for Privacy-Preserving ML Inference. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2510.24498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasam, V.R.; Devaraju, P.; Methuku, V.; Dharamshi, K.; Veerapaneni, S.M. Engineering Scalable AI Pipelines: A Cloud-Native Approach for Intelligent Transactional Systems. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Computing Technologies (ICOCT), 2025; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahane, R. Design Patterns for Scalable ML Workflows in Azure Data Lake and Synapse Analytics 2024. 12 11. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).