1. Introduction

Influenza A viruses are categorized by 18 hemagglutinin (H) subtypes and 11 neuraminidase (N) subtypes, forming 198 potential combinations. Among these, H1N1 represents one of the most prevalent subtypes [

1]. Four key subtypes—H1N1, H2N2, H3N2, and H5N1—have demonstrated substantial impacts on human health. The 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic originated from a novel H1N1 strain containing genetic material from swine, avian, and human influenza viruses. This triple-reassortant viral architecture enabled cross-species transmission, allowing simultaneous infection of humans, birds, and swine [

2,

3,

4,

5]. As a recombinant virus, it exhibits accelerated mutation rates and broad population susceptibility, driving recurrent global outbreaks that threaten public health security [

6]. This study characterized two H1N1 influenza virus strains identified during routine epidemiological surveillance of swine herds in Shandong Province. Using high-throughput sequencing and phylogenetic analysis, we evaluated their genetic evolution to gain insights into their potential transmission pathways dynamics and inform targeted prevention strategies for mitigating public health and agricultural risks.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Processing and Sequencing

In 2019, 200 porcine lung samples were obtained from swine herds exhibiting clinical signs of respiratory disease (coughing, fever, ocular/nasal discharge) across multiple cities in Shandong Province, China, including Liaocheng, Linyi, Jinan, Qingdao, and etc. All pig lung samples were independently collected by farmers in 2019 from deceased pigs exhibiting respiratory symptoms (fever, coughing, etc.) at different times and locations within their respective farms. These samples were subsequently sent to our laboratory for testing.

Lung samples were homogenized in 500 μL PBS buffer [

7]. Following centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 3 minutes to remove cellular debris, viral RNA was isolated from 200 μL of clarified supernatant using the Simply P Total RNA Extraction Kit (Bioflux) per standardized protocols. All procedures were conducted within a biosafety cabinet using filter-tipped pipette tips to minimize aerosol contamination and cross-contamination.

This study employed validated universal primers from our laboratory for preliminary influenza virus detection. Following RT-PCR testing of 200 collected pig lung samples, two samples (1%) tested positive for SIV. These two positive samples originated from two pig farms in Linyi city and Shanghe County of Jinan City, Shandong Province. Positive samples were then sent to the company for next-generation sequencing to obtain full genome sequences.

2.2. Bioinformatic and Phylogenetic Analysis

The genomic characterization of H1N1 subtype swine influenza viruses was conducted through analysis of sequences obtained using MegAlign and MEGA 11, where each gene fragment derived from sequencing served as the target sequence for subsequent homology-based investigations. High-homology sequences retrieved via BLAST analysis were systematically compared with reference sequences acquired from NCBI GenBank (Table S1), encompassing human, canine, avian, and livestock origins, all specimens being temporally constrained to the 2004–2020 surveillance period.

Phylogenetic analysis of genes such as PB1 and PB2 was performed using MEGA11. The coding nucleotide sequences corresponding to the genes were downloaded from the NCBI database. Subsequent analyses were conducted using MEGA 11 software. First, the built-in MUSCLE algorithm was employed for multiple sequence alignment, followed by manual refinement to ensure correct codon framing. Subsequently, MEGA’s ‘Find Best Model’ function was employed to determine the GTR model as the optimal nucleotide substitution model for this dataset based on maximum likelihood principles. Finally, a phylogenetic tree was constructed using maximum likelihood analysis with the selected model, and bootstrap analysis with 1000 repetitions was performed to assess branch reliability.

2.3. Genetic Recombination Analysis

Potential recombination events were analyzed using SimPlot (version 3.5.1) and RDP5 (version 5.2) software, and validated through 1,000 bootstrap repetitions. In the RDP5 analysis, recombination signals were determined using a corrected p-value threshold. The selection of reference strains is based on the following principles: Sequence similarity and priority is given to strains exhibiting the highest homology with each gene fragment of the strain under study in BLAST alignments.

3. Results

3.1. Virus Gene Sequencing and Sequence Submission

This study collected 200 swine lung tissue samples from multiple locations in Shandong Province. Two distinct influenza A viruses were identified and sequenced from these samples, designated as A/swine/China/SD6591/2019(H1N1) (abbreviated as SD6591) and A/swine/China/SD6592/2019(H1N1) (abbreviated as SD6592).

The GenBank accession numbers of the SD6591 viral gene segments are PV464931-PV464938, and the GenBank accession numbers corresponding to each of the eight SD6592 viral gene segments are PV464939-PV464946.

3.2. Bioinformatic Analysis

We analyzed the individual viral genes using the BLAST database, followed by comparative assessment of nucleotide homology between SD6591 and other H1N1 strains available in GenBank. The PB2, PB1, NP, NA, HA, and NEP genes exhibited the highest homology with swine-origin H1N1 subtype influenza viruses, The PA and M2 genes exhibit high homology with human-origin H1N1 subtype influenza viruses, indicating that the PA and M2 genes of this virus are most closely related to the corresponding gene clusters of human seasonal H1N1 influenza viruses. This suggests that these gene fragments may ultimately originate from human H1N1 viruses. However, no direct epidemiological evidence currently links this virus to specific recent human cases. This genetic association suggests ongoing evolution of human-derived viral genes within swine populations and underscores the importance of monitoring swine influenza for zoonotic transmission risks (

Table 1). Isolates from humans and dogs are tightly nested within the evolutionary branch of swine viruses, lacking evidence of independent multigenerational transmission. This aligns with the genetic pattern of unidirectional spillover from pigs to humans and from pigs to dogs. Therefore, it is considered a zoonotic event, representing an instance where a virus circulating within a pig population was captured upon spilling over to an accidental host.

This genomic analysis indicates that strain SD6591 potentially represents a human-swine influenza reassortant virus. Phylogenetic analysis indicates that the M2 gene of strain SD6591 is most closely related to canine-origin H1N1 influenza viruses, suggesting this gene fragment may have entered swine populations through cross-species transmission between dogs and pigs. Selecting human-origin strains as references aims to establish a standard host reference system and conduct preliminary public health risk assessments. This finding reveals the complexity of influenza virus transmission pathways across species and underscores the necessity of expanding surveillance to include companion animals.

Subsequent comparative genomic characterization of SD6592 through GenBank alignment revealed that PB2, PB1, NP, NA, HA, NEP, PA, and M2 gene segments exhibited >98% nucleotide homology with H1N1 subtype swine influenza strains, suggesting limited genetic divergence between the newly identified strain and previously documented H1N1 variants. Notably, phylogenetic analysis demonstrated closest evolutionary relationship with A/swine/Beijing/0301/2018(H1N1) (

Table 2).

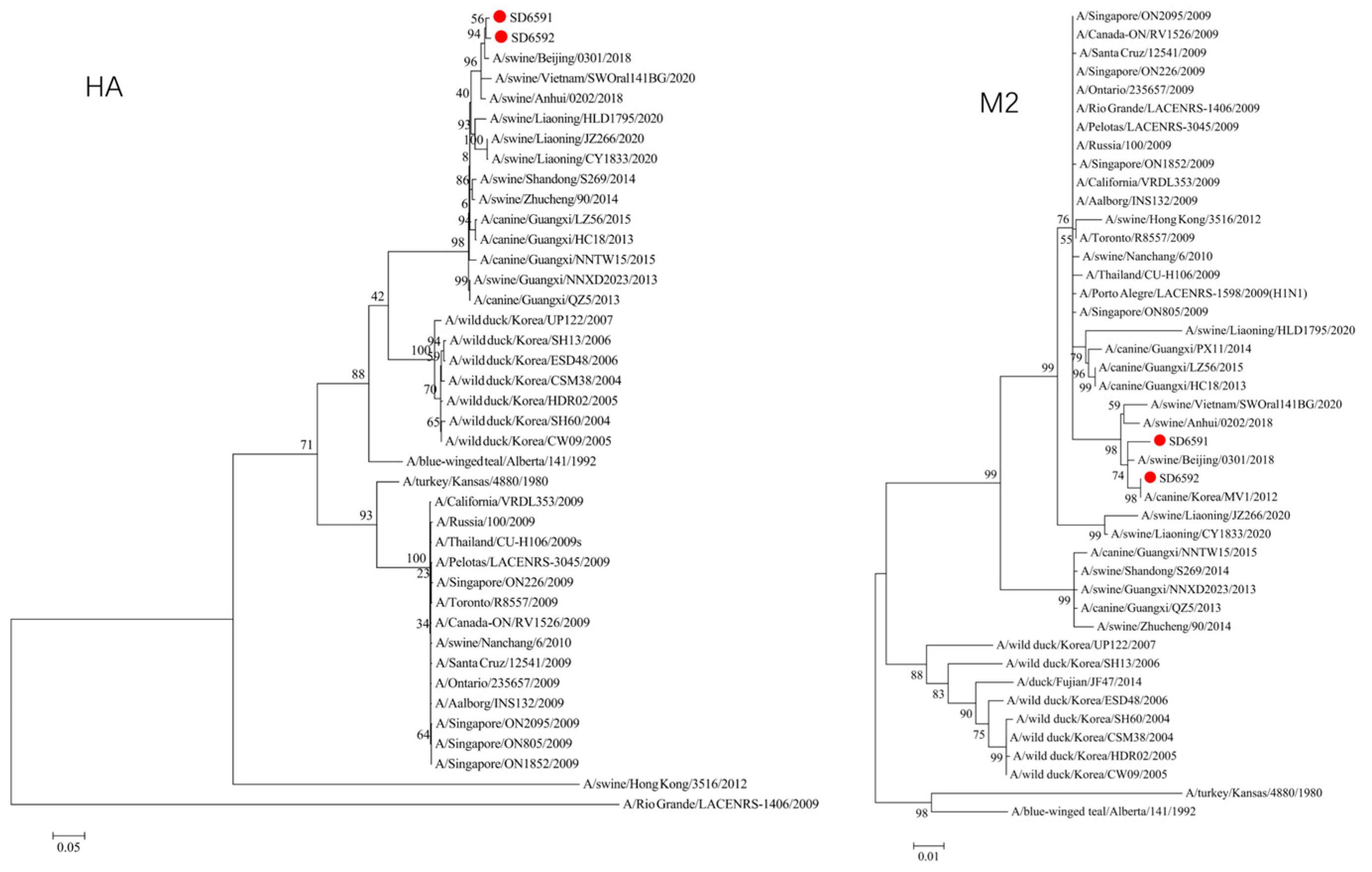

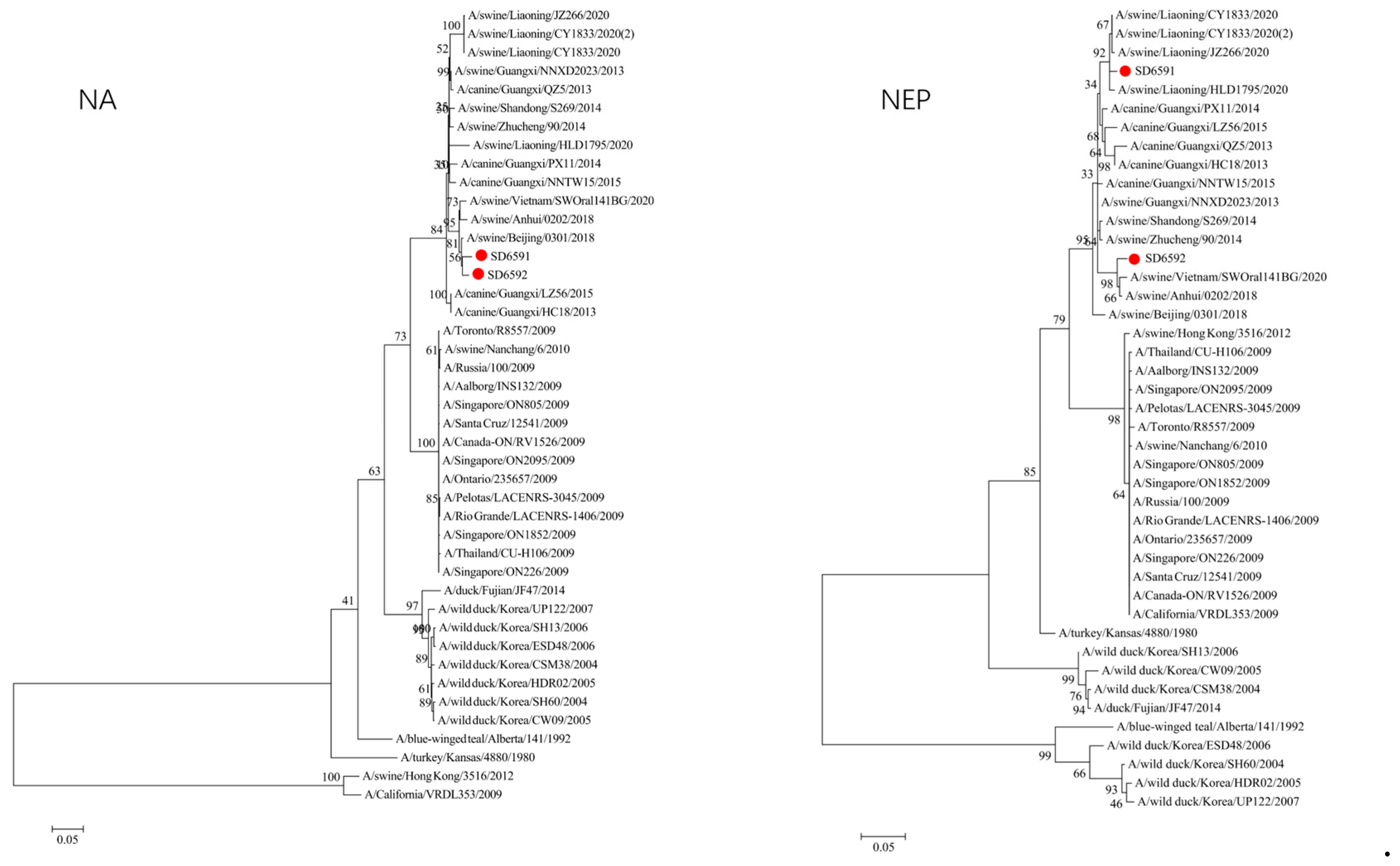

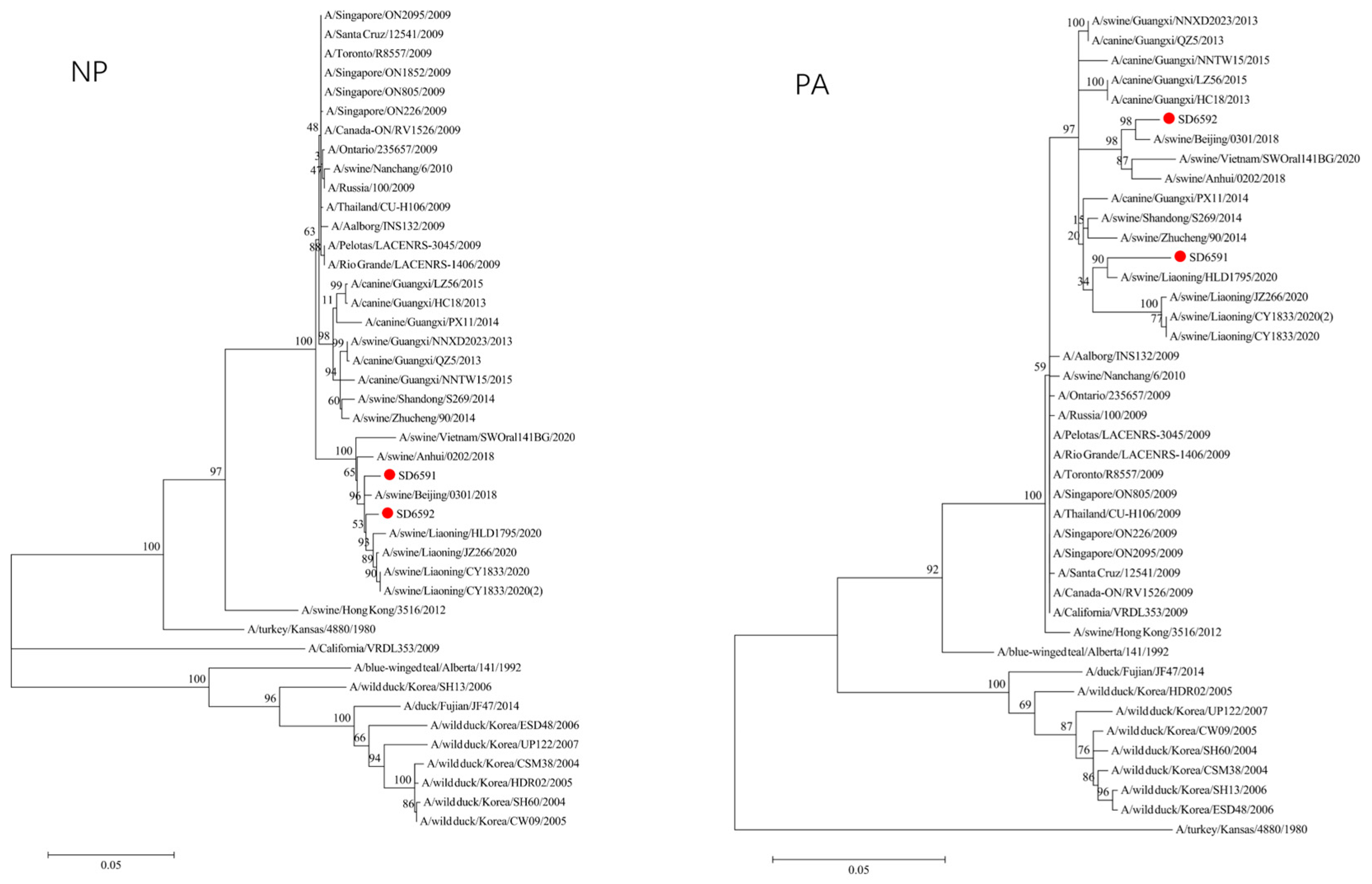

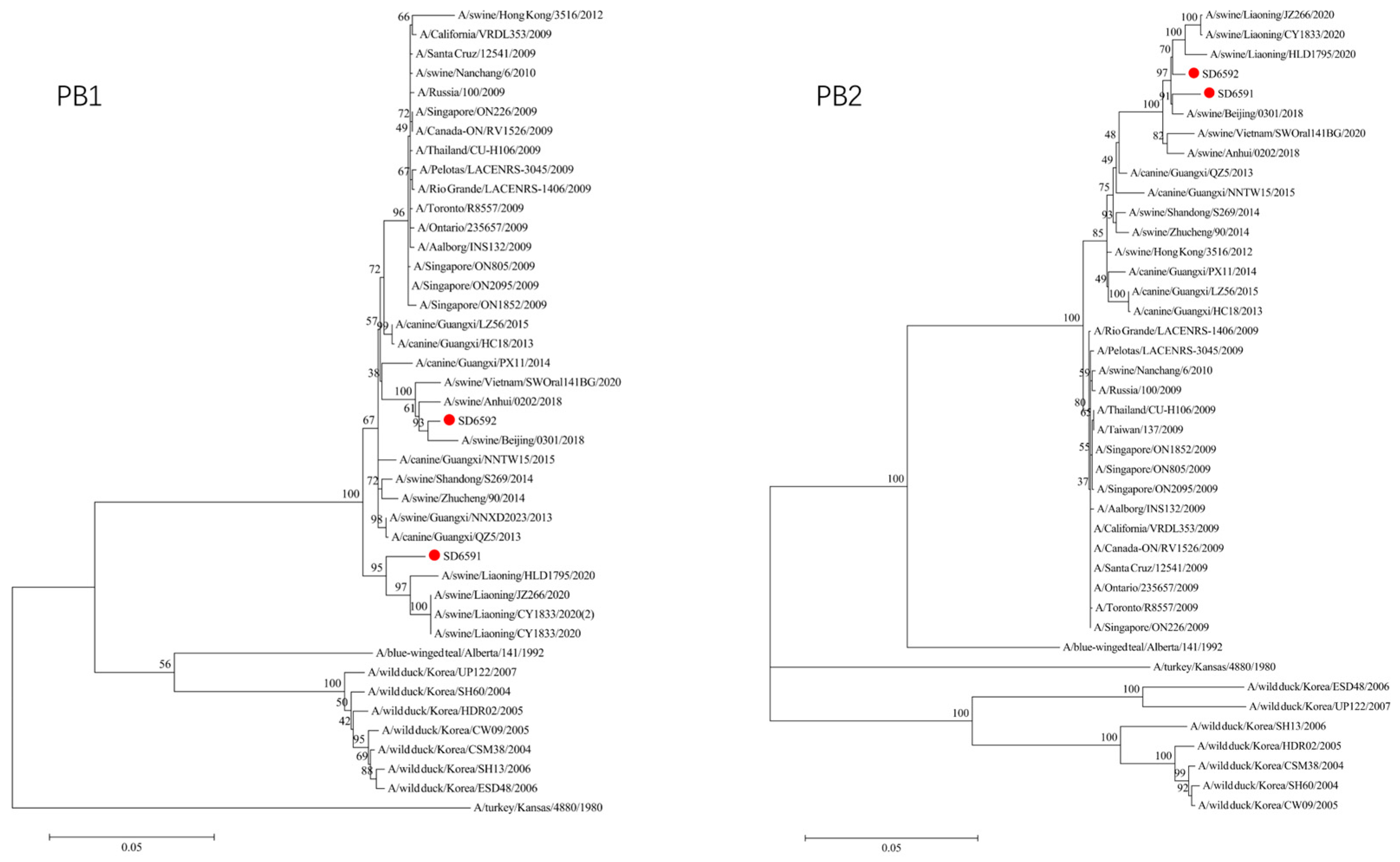

3.3. Phylogenetic Analysis

We conducted phylogenetic analysis of influenza virus strains SD6591 and SD6592 through individual gene alignment. As shown in

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3, and

Figure 4, the HA, NA, NP, and PB2 genes of SD6591 clustered with A/swine/Beijing/0301/2018(H1N1), while PA and NEP genes shared higher similarity with the same reference strain. The M2 gene displayed dual phylogenetic affinity with both A/swine/Beijing/0301/2018(H1N1) and A/canine/Korea/MV1/2012. The PB1 gene demonstrated evolutionary proximity to A/swine/Liaoning/CY1833/2020, A/swine/Liaoning/HLD1795/2020, and A/swine/Liaoning/JZ266/2020.

As shown in

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3, and

Figure 4, analysis shows that the HA, PA, NA, and PB1 genes of SD6592 form a monophyletic branch with A/swine/Beijing/0301/2018(H1N1), while M2 is more closely related to A/canine/Korea/MV1/2012. The NEP gene shares ancestral connections with A/swine/Vietnam/SWOral141BG/2020 and A/swine/Anhui/0202/2018, while PB2 and NP genes cluster with Liaoning swine variants CY1833/2020, HLD1795/2020, and JZ266/2020. The NA gene forms a polyphyletic group encompassing H1N1 swine influenza variants from Vietnam, Anhui, and Beijing. Red solid dots: Represent original viral sequences sequenced or analyzed in this study. Branch node numbers: Indicate bootstrap support values, used to assess the confidence and reliability of each branch (calculated through 1000 repeated bootstrap samples).

3.4. Genetic Recombination Analysis

H1N1 has been detected in a variety of mammals and it has the potential for zoonotic transmission [

8]. In addition, genetic recombination is an important mode of RNA virus evolution [

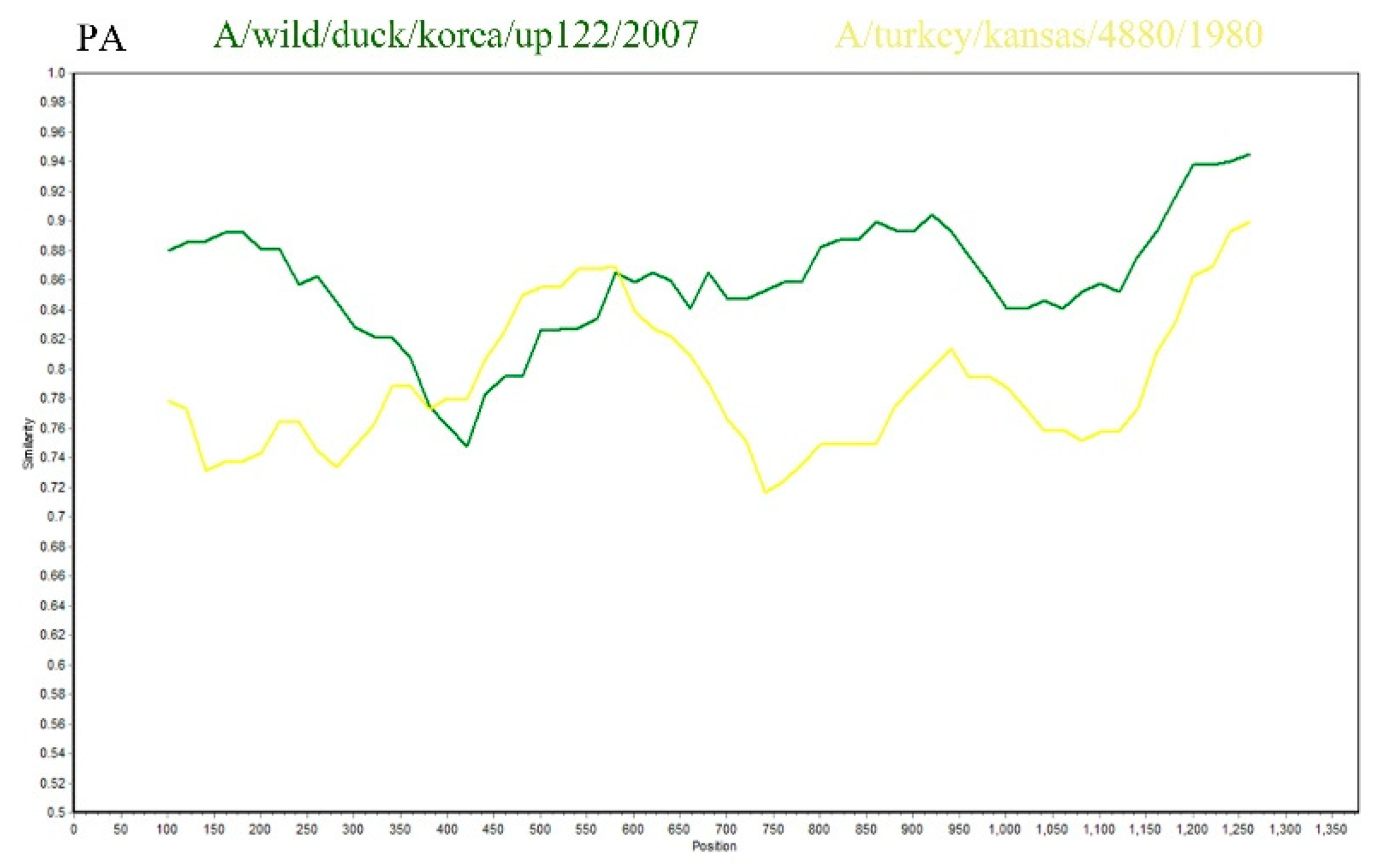

9]. This study utilized SimPlot software, with SD6591 as the query sequence, to conduct recombination analysis with the A/Wild duck/Korea/UP122/2007 strain and the A/turkey/Kansas/4880/1980 strain. The results indicated that the PA gene of SD6591 exhibited a high degree of sequence homology (87.5%) with the A/turkey/Kansas/4880/1980 strain (GenBank accession number: EU742643.2) within the 400–600 bp region, while it showed even higher homology (95.2%) with the A/Wild duck/Korea/UP122/2007 strain (GenBank accession number: HQ014821.1) within the 600–1250 bp region. This suggests that the PA gene of SD6591 may originate from a recombination event between the aforementioned duck-derived and turkey-derived strains (

Figure 5).

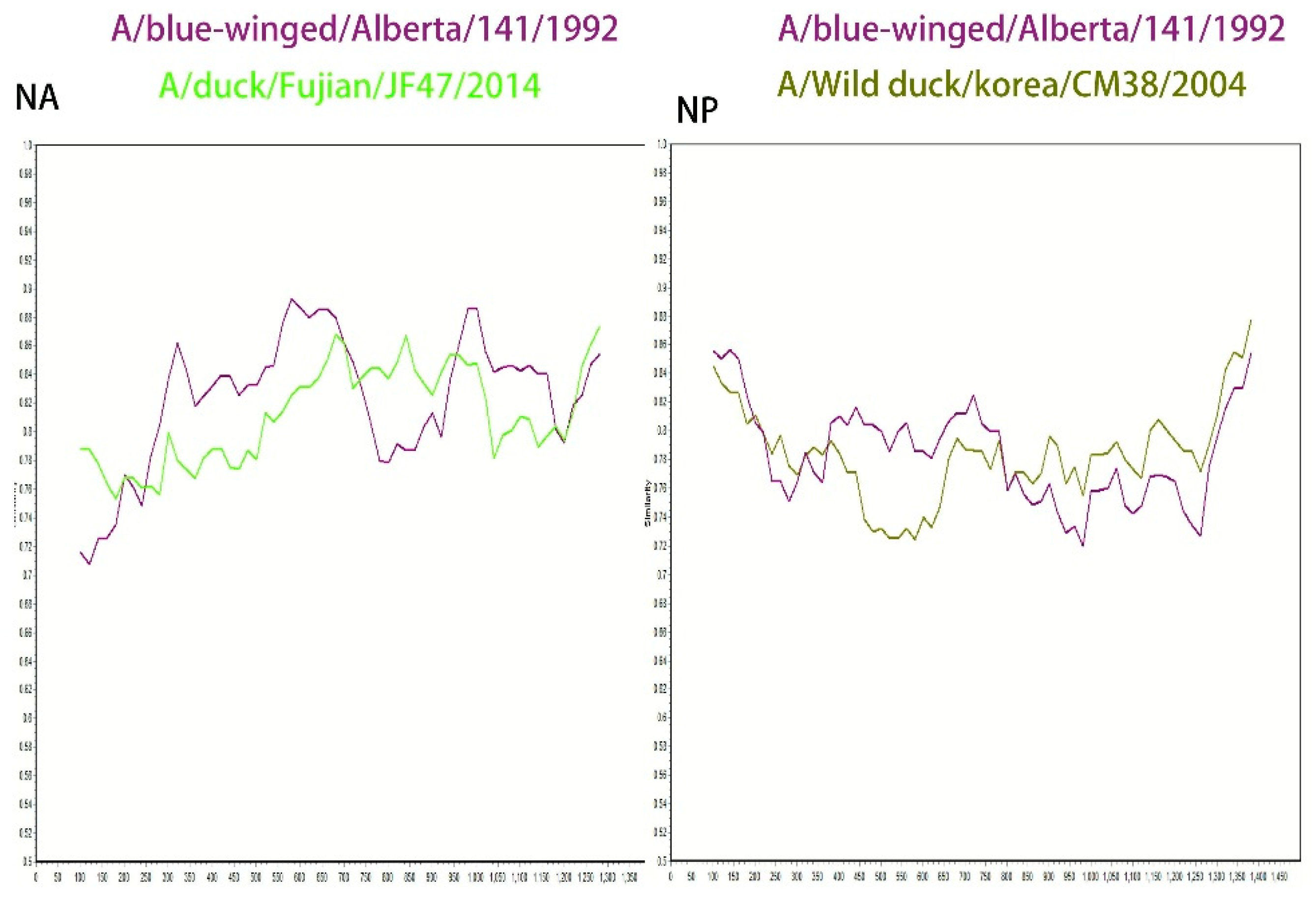

In addition, this study conducted a SimPlot recombination analysis of the NA gene using SD6592 as the query sequence, with the A/blue-winged teal/Alberta/141/199 strain and the A/duck/Fujian/JF47/2014 strain as backgrounds. The results showed that the sequence homology was relatively high (89.2%) in the 300–750 bp interval with the A/blue-winged teal/Alberta/141/199 strain, while the homology was higher (85.5%) in the 650–900 bp interval with the A/duck/Fujian/JF47/2014 strain (GenBank accession number: KP657996.1), suggesting that the NA gene may originate from recombination between the two aforementioned strains (

Figure 6).

In the NP gene analysis, recombination analysis was conducted using the A/blue-winged teal/Alberta/141/199 strain (GenBank accession number: CY004545.1) and the A/wild duck/Korea/CSM38/2004 strain (GenBank accession number: HQ014821.1) as backgrounds. The results indicated a high homology (82.5%) with the A/blue-winged teal/Alberta/141/199 strain in the 400–700 bp region, and a high homology (82.5%) with the A/wild duck/Korea/CSM38/2004 strain in the 850–1300 bp region, suggesting that the NP gene may have been formed by recombination of the aforementioned two wild duck-derived strains (

Figure 6).

To confirm the evolutionary history of the PA, NA and NP gene, we conducted a multi-algorithm recombination event analysis using the RDP5 software package, building upon our preliminary SimPlot analysis. After testing with multiple methods including RDP, GENECONV, and BootScan, and applying a corrected p-value threshold of <0.05, no statistically significant recombination signals were detected. These results indicate that the sequence mosaicism observed in the PA gene is more likely attributable to complex point mutation accumulation or unsampled ancestral sequences, rather than recent direct recombination events. This finding suggests relative genetic stability within this viral lineage in the porcine host.

4. Discussion

SIV can cause highly contagious respiratory diseases in pigs, it has led to an increase in mortality rates on many farms in China, posing a major threat to the farming industry in China [

10,

11]. H1N1 subtypes of swine influenza viruses are widespread in swine populations and undergo regular mutation. In 2009, a novel H1N1 swine influenza virus was first detected in Mexico and rapidly spread worldwide, triggering the so-called “H1N1 influenza A pandemic” [

12]. This pandemic demonstrated that swine influenza viruses can spread across species to humans and cause global epidemics. Currently, the spread of influenza can be prevented and controlled through enhanced vaccination, personal hygiene and public health measures [

13].

This study detected only 2 SIV-positive cases (a positivity rate of 1%) among 200 samples. However, this investigation involved nucleic acid testing only. We will subsequently collect serum samples and conduct hemagglutination inhibition tests to verify whether the virus is prevalent in pig populations. Pigs act as a “mixing vessel” for influenza viruses, continuous monitoring and research on swine influenza viruses is also an important means to detect new mutated strains in time and develop effective preventive and control measures. Analysis of the biological characteristics of two H1N1 subtypes, SIV SD6591 and SD6592, identified in two independent infected pigs in Shandong Province, aims to understand the epidemiological situation of SIV in Shandong pig farms and provide reference for the prevention and control of swine influenza in China.

In the present study of viruses from Shandong, homology analysis showed that SD6591 had high nucleotide sequence homology with SIV identified in Beijing or Anhui, and the nucleotide sequences with the highest homology in the PA and M2 genes were originated from human beings, To validate this reassortment hypothesis and elucidate its biological significance, future research urgently requires: conducting mixed infection studies under experimental conditions to assess the likelihood and efficiency of reassortment occurring when human influenza viruses and swine influenza viruses co-infect cells or animal models.

The establishment of a biological phylogenetic tree for each gene by MEGA11 showed that strain SD6591 was closely related to A/swine/Beijing/0301/2018 (H1N1) and A/canine/Korea/MV1/-2012 (H1N1), thus verifying the cross-species transmission of SIV [

14]. When two or three viral strains infect the same host at the same time, their genome segments may be exchanged and recombined, and genetic recombination can produce influenza virus strains with new characteristics. Swine is one of the most important hosts for the genetic recombination of influenza viruses, and these strains of viruses may have a higher pathogenicity or a stronger transmission capacity [

15,

16,

17]. Therefore, in-depth studies of genetic mutations and genetic recombination of SIV are important for understanding their pathogenic mechanisms, developing effective prevention and control strategies, and developing novel vaccines and antiviral drugs [

18].

Although preliminary analysis based on similarity graphs suggested sequence differences, more rigorous RDP5 multi-algorithm reassortment analysis failed to reveal clear statistical evidence supporting reassortment events. Therefore, the observed sequence variations are more likely attributable to accumulated point mutations rather than reassortment. This finding suggests that this viral lineage may exhibit relative genetic stability during evolution, which is significant for understanding its epidemiological characteristics.

The observations in this study are based on a limited sample size; therefore, the evolutionary differences revealed are preliminary and require confirmation through future, more extensive research. Furthermore, this study is based on genomic analysis and has not yet involved experimental verification of viral biological characteristics (such as replication capacity and pathogenicity) or real-world epidemiological conditions. Future comprehensive assessments of its potential risks should be conducted through viral isolation, animal experiments, and large-scale epidemiological investigations.

5. Conclusions

This study conducted a systematic analysis of eight gene segments from SD6591 and SD6592 strains, including homology comparison, phylogenetic tree construction, and recombination detection. The results indicated that no significant recombination events were observed in the gene segments, suggesting that these two strains of swine influenza virus maintained a relatively stable genetic background during this study. However, considering the crucial role of pigs in the cross-host transmission and gene reassortment of influenza viruses, as well as the frequent contact among multiple species in the farming environment, strengthening surveillance of influenza viruses in pig populations is helpful for timely detection of potential recombinant or mutated strains, providing a scientific basis for preventing and controlling the emergence and spread of novel influenza viruses.

Author Contributions

Research design, experimental operation, first draft of paper, Zhijun Yu and Zhen Yuan; Data analysis, chart production, methodological verification, Zhen Yuan; Financial support, experimental supervision, and paper revision, Zhijun Yu, Ran We, Kaihui Cheng; Sample processing, Zhen Yuan, Rui Shang, Sisi Ma; Academic discussion (solution suggestions for key issues). Zhijun Yu, Ran Wei, Kaihui Cheng, Huixia Zhang.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32270562), the Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (ZR2022MC007; ZR2024MC172; ZR2023QC319; ZR2021MC119).

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

There are no potential conflicts of interest.

References

- Yu H, Sun Y, Zhang J, Zhang W, Liu W, Liu P, Liu K, Sun J, Liang H, Zhang P, Wang X, Liu X, Xu X (2024) Influenza A virus infection activates caspase-8 to enhance innate antiviral immunity by cleaving CYLD and blocking TAK1 and RIG-I deubiquitination. Cell Mol Life Sci 81:355. [CrossRef]

- Avanthay R, Garcia-Nicolas O, Ruggli N, Grau-Roma L, Parraga-Ros E, Summerfield A, Zimmer G (2024) Evaluation of a novel intramuscular prime/intranasal boost vaccination strategy against influenza in the pig model. PLoS Pathog 20:e1012393. [CrossRef]

- Gray GC, Bender JB, Bridges CB, Daly RF, Krueger WS, Male MJ, Heil GL, Friary JA, Derby RB, Cox NJ (2012) Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 virus among healthy show pigs, United States. Emerg Infect Dis 18:1519-1521. [CrossRef]

- Avanthay R, Garcia-Nicolas O, Zimmer G, Summerfield A (2023) NS1 and PA-X of H1N1/09 influenza virus act in a concerted manner to manipulate the innate immune response of porcine respiratory epithelial cells. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 13:1222805. [CrossRef]

- Xing L, Chen Y, Chen B, Bu L, Liu Y, Zeng Z, Guan W, Chen Q, Lin Y, Qin K, Chen H, Deng X, Wang X, Song W (2021) Antigenic Drift of the Hemagglutinin from an Influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 Clinical Isolate Increases its Pathogenicity In Vitro. Virol Sin 36:1220-1227. [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsova N, Siniavin A, Butenko A, Larichev V, Kozlova A, Usachev E, Nikiforova M, Usacheva O, Shchetinin A, Pochtovyi A, Shidlovskaya E, Odintsova A, Belyaeva E, Voskoboinikov A, Bessonova A, Vasilchenko L, Karganova G, Zlobin V, Logunov D, Gushchin V, Gintsburg A (2023) Development and characterization of chimera of yellow fever virus vaccine strain and Tick-Borne encephalitis virus. PLoS One 18:e0284823. [CrossRef]

- Du S, Xu F, Lin Y, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Su K, Li T, Li H, Song Q (2022) Detection of Porcine Circovirus Type 2a and Pasteurella multocida Capsular Serotype D in Growing Pigs Suffering from Respiratory Disease. Vet Sci 9. [CrossRef]

- Holzer B, Rijal P, McNee A, Paudyal B, Martini V, Clark B, Manjegowda T, Salguero FJ, Bessell E, Schwartz JC, Moffat K, Pedrera M, Graham SP, Noble A, Bonnet-Di Placido M, La Ragione RM, Mwangi W, Beverley P, McCauley JW, Daniels RS, Hammond JA, Townsend AR, Tchilian E (2021) Protective porcine influenza virus-specific monoclonal antibodies recognize similar haemagglutinin epitopes as humans. PLoS Pathog 17:e1009330. [CrossRef]

- Mac Kain A, Joffret ML, Delpeyroux F, Vignuzzi M, Bessaud M (2021) A cold case: non-replicative recombination in positive-strand RNA viruses. Virologie (Montrouge) 25:62-73. [CrossRef]

- Ren C, Chen T, Zhang S, Gao Q, Zou J, Li P, Wang B, Zhao Y, OuYang A, Suolang S, Zhou H (2023) PLK3 facilitates replication of swine influenza virus by phosphorylating viral NP protein. Emerg Microbes Infect 12:2275606. [CrossRef]

- Zhu W, Wang L, Dong Z, Chen X, Song F, Liu N, Yang H, Fu J (2016) Comparative Transcriptome Analysis Identifies Candidate Genes Related to Skin Color Differentiation in Red Tilapia. Sci Rep 6:31347. [CrossRef]

- Galindo-Fraga A, Del Carmen Guerra-de-Blas P, Ortiz-Hernandez AA, Rubenstein K, Ortega-Villa AM, Ramirez-Venegas A, Valdez-Vazquez R, Moreno-Espinosa S, Llamosas-Gallardo B, Perez-Patrigeon S, Noyola DE, Magana-Aquino M, Vilardell-Davila A, Guerrero ML, Powers JH, Beigel J, Ruiz-Palacios GM, Mexican Emerging Infectious Disease Clinical Research N (2024) Prospective cohort study of patient demographics, viral agents, seasonality, and outcomes of influenza-like illness in Mexico in the late H1N1-pandemic and post-pandemic years (2010-2014). IJID Reg 12:100394. [CrossRef]

- Tapia R, Mena J, Garcia V, Culhane M, Medina RA, Neira V (2023) Cross-protection of commercial vaccines against Chilean swine influenza A virus using the guinea pig model as a surrogate. Front Vet Sci 10:1245278. [CrossRef]

- Schmitt K, Curlin J, Remling-Mulder L, Moriarty R, Goff K, O’Connor S, Stenglein M, Marx P, Akkina R (2020) Mimicking SIV chimpanzee viral evolution toward HIV-1 during cross-species transmission. J Med Primatol 49:284-287. [CrossRef]

- Si L, Bai H, Oh CY, Jin L, Prantil-Baun R, Ingber DE (2021) Clinically Relevant Influenza Virus Evolution Reconstituted in a Human Lung Airway-on-a-Chip. Microbiol Spectr 9:e0025721. [CrossRef]

- Yu J, Liu R, Zhou B, Chou TW, Ghedin E, Sheng Z, Gao R, Zhai SL, Wang D, Li F (2019) Development and Characterization of a Reverse-Genetics System for Influenza D Virus. J Virol 93. [CrossRef]

- Simon PF, McCorrister S, Hu P, Chong P, Silaghi A, Westmacott G, Coombs KM, Kobasa D (2015) Highly Pathogenic H5N1 and Novel H7N9 Influenza A Viruses Induce More Profound Proteomic Host Responses than Seasonal and Pandemic H1N1 Strains. J Proteome Res 14:4511-4523. [CrossRef]

- Kasturi SP, Kozlowski PA, Nakaya HI, Burger MC, Russo P, Pham M, Kovalenkov Y, Silveira ELV, Havenar-Daughton C, Burton SL, Kilgore KM, Johnson MJ, Nabi R, Legere T, Sher ZJ, Chen X, Amara RR, Hunter E, Bosinger SE, Spearman P, Crotty S, Villinger F, Derdeyn CA, Wrammert J, Pulendran B (2017) Adjuvanting a Simian Immunodeficiency Virus Vaccine with Toll-Like Receptor Ligands Encapsulated in Nanoparticles Induces Persistent Antibody Responses and Enhanced Protection in TRIM5alpha Restrictive Macaques. J Virol 91. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).