1. Introduction

Despite extensive research in the field, anastomotic leakage remains a common and serious complication in colorectal surgery, occurring in approximately 3–7% of cases, with mortality rates ranging from 2–4% [

8]. Furthermore, the leakage rate for low rectal anastomoses may be even higher, reaching up to 27% in some reports [

4,

6,

7]. Anastomotic leakage is multifactorial in etiology, and ischemia of the colonic margins is considered one of the most important contributing factors [

1]. Known risk factors include smoking, coronary artery disease, and hypertension. Patients with these comorbidities often suffer from microvascular disease that impairs tissue perfusion, especially in the anastomotic area, which may lead to ischemia and subsequently increase the risk of leakage [

9,

10,

11]. This complication can significantly affect the clinical course of the patient, potentially resulting in fever, abscess formation, sepsis, metabolic disturbances, and/or multiorgan failure [

12]. However, no existing animal model has demonstrated a direct link between marginal ischemia and anastomotic leakage. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to develop a rat model with varying degrees of ischemia at the colonic incision margins to test this relationship. A validated model of this nature could assist in evaluating new interventions intended to reduce the incidence of anastomotic leakage, particularly in high-risk patients [

1]. Animal experiments remain essential tools for understanding pathophysiological mechanisms and for evaluating interventions aimed at preventing anastomotic leakage. Most experimental models in this field have utilized rats to establish colonic anastomoses [

12,

13,

14]. Other animal models, such as pigs and dogs, have also been used. However, these models pose several limitations including ethical concerns, high cost, housing difficulties, and lack of clinical relevance, making rodent models more practical and commonly used [

15,

16,

17]. Several studies in the literature have focused on optimizing the development of models that reliably induce anastomotic leaks in rodents. These efforts have included evaluating appropriate analgesic protocols, determining the ideal number of sutures, and the adoption of absorbable sutures, all of which have contributed to refining these experimental models. Accordingly, future research may focus on identifying predisposing factors that elevate the risk of leakage. Recognizing such factors may aid surgeons in selecting appropriate patients for primary anastomosis and ultimately reduce postoperative morbidity and mortality [

19]. Our model simulates a mechanical injury to the intestinal wall by applying localized pressure to the mesenteric side of the bowel, in a manner resembling conditions such as intestinal strangulation, segmental ischemia, or trauma. The model is based on creating a partial obstruction of blood flow in the mesenteric vessels of the bowel segment, with end-to-end anastomosis performed afterward. This simulation allows evaluation of various factors affecting anastomotic healing, such as blood supply, age, systemic diseases, pharmacologic interventions, and more.

2. Materials and Methods

A total of 144 rats were used in this experimental study conducted at the animal facility of Soroka University Medical Center. For the study, rats weighing 300 grams were used and underwent open surgery via laparotomy. Anesthesia was administered using inhalational gas. The procedure involved transection of the transverse colon followed by an end-to-end anastomosis, performed using a single-layer, interrupted suture technique with six 5-0 Vicryl stitches. The experimental groups were defined based on the degree of ischemia applied to the mesocolon, simulating varying levels of vascular injury:

The first group (control group) underwent resection without any mesocolon injury.

In the other groups, ischemia was induced by clamping a defined segment of the mesocolon on one side of the bowel, for a specific length proximal to the anastomosis site. The degree of vascular injury to the mesocolon was modulated as follows:

Group 1 – No mesocolon injury

Group 2 – 0.2 cm ischemic segment on one side of the mesocolon

Group 3 – 0.4 cm ischemic segment on one side of the mesocolon

Group 4 – 1 cm ischemic segment on one side of the mesocolon

Group 5 – 2 cm ischemic segment on one side of the mesocolon

All rats were monitored for 20 minutes postoperatively to assess bleeding and recovery from anesthesia. The rats were then returned to their cages with free access to food and water. Ten days after the primary surgery, a second laparotomy was performed to evaluate the healing of the anastomosis and assess for complications such as anastomotic leak, peritonitis, or other causes of morbidity and mortality. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines for the use of animals in research and was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Israel. All experiments were performed on a defined number of healthy rats, using standard anesthetic protocols and humane endpoints.

3. Results

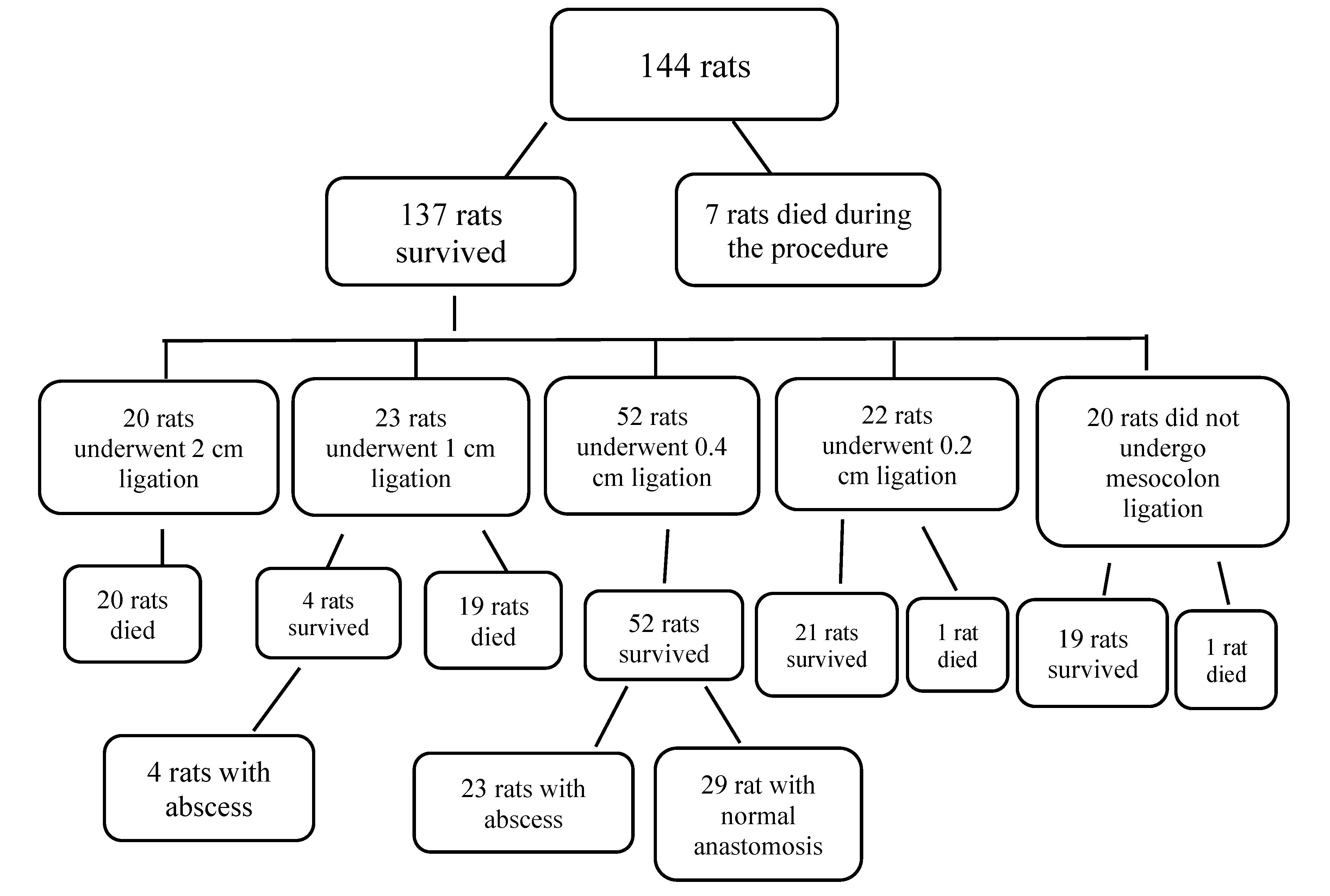

For an entire year, experiments were conducted on rats, which were divided into small groups. In each group, rats were randomly selected to undergo mesocolon ligation, with a different type of ligation performed each time. The table below summarizes all the small rat groups together and presents the number of animals that died during the procedure for various reasons, those that died later, and those that survived with a proper anastomosis, abscess formation, or other outcomes. It is important to note that equal conditions were strictly maintained for all rats in terms of anesthesia administration, analgesics, hydration, and nutrition.

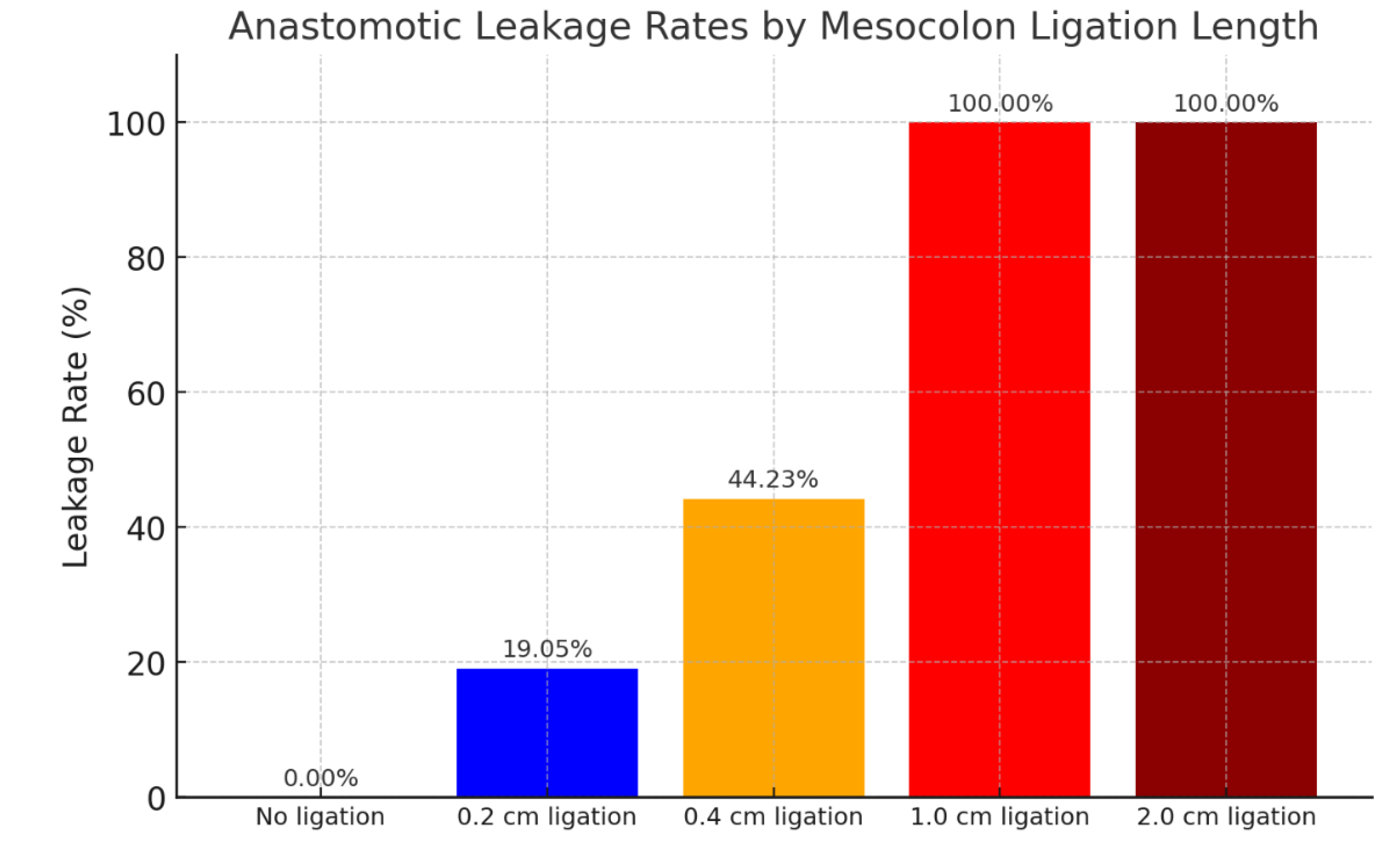

Following the random allocation of rats to undergo surgery with mesocolon ligation at varying lengths, the anastomoses were evaluated. Some anastomoses were intact, while others were compromised, presenting with leakage, abscesses, and related complications. The table above presents the leakage rates observed in each experimental group. It can be concluded that rats which did not undergo mesocolon ligation exhibited a 100% rate of intact anastomosis. In rats subjected to ligation of 0.2 cm on each side, leakage occurred in 19.05% of cases. In those with 0.4 cm ligation on each side, leakage was observed in 44.23% of cases. Rats that underwent ligation of 1 cm showed a 100% leakage rate, while those with 2 cm ligation on each side experienced 100% mortality.

Based on our results, it can be concluded that ligation at 0.4 cm results in a leakage rate of 44.23%, which may serve as a reliable model for future experimental studies. Ligation at 0.2 cm could also be considered as a model, though the leakage rate was less consistent, occurring in only 19.05% of cases. According to the present study, ligation greater than 1 cm resulted in 100% mortality. Additionally, it was decided to measure the bursting pressure of the anastomosis as part of the evaluation of the anastomotic line, ten days after the initial surgery.

Table 1.

Summary of outcomes by mesocolon ischemia severity.

Table 1.

Summary of outcomes by mesocolon ischemia severity.

| Group |

Survived |

Died Intra-op |

Died Post-op (24h) |

Leak |

Total |

Anastomotic Leak Rate (%) |

| No ischemia (control) |

22 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

22 |

0.0 |

| 0.2 cm mesocolon ischemia |

24 |

2 |

1 |

4 |

24 |

19.05 |

| 0.4 cm mesocolon ischemia |

52 |

2 |

0 |

23 |

54 |

44.23 |

| 1 cm mesocolon ischemia |

4 |

1 |

19 |

23 |

24 |

100 |

| 2 cm mesocolon ischemia |

0 |

0 |

20 |

20 |

20 |

100 |

Summary of perioperative and postoperative outcomes in rats undergoing end-to-end colonic anastomosis with varying lengths of mesocolon ischemia. Data include intraoperative mortality, early postoperative mortality, anastomotic leakage, and overall survival rates. Increasing ischemic length was associated with progressively higher rates of anastomotic failure and mortality.

Figure 1.

Anastomotic leakage rates according to mesocolon ligation length.

Figure 1.

Anastomotic leakage rates according to mesocolon ligation length.

Figure 2.

Flowchart illustrating rat allocation, survival and postoperative outcomes across experimental groups.

Figure 2.

Flowchart illustrating rat allocation, survival and postoperative outcomes across experimental groups.

This table summarizes the experimental results from a controlled animal model, in which rats underwent colonic anastomosis under varying degrees of ischemia applied to the mesocolon adjacent to the anastomotic site. Each experimental group was defined according to the severity and length of the ischemic injury applied unilaterally to the mesocolon, with standardized timing and location relative to the anastomosis. The data presented in the table reflect a clear trend: as the degree of mesocolon ischemia increases, there is a corresponding rise in morbidity and mortality, either intraoperatively or in the postoperative period. This highlights the critical role of mesenteric perfusion in anastomotic healing. The differences in anastomotic leak rates among the groups further emphasize the importance of local tissue perfusion and vascular integrity for successful anastomotic recovery.

This model establishes a direct relationship between incision margin ischemia and anastomotic leak rates in rats. Our findings align with previous animal studies demonstrating ischemia as a critical factor in leak development. Unlike models using large animals, the rat model offers logistical and ethical advantages. The 0.4 cm ligation condition yielded a consistent and intermediate leak rate suitable for testing preventive strategies. Future applications include evaluating antibiotics, novel suturing techniques, and perfusion-enhancing technologies.

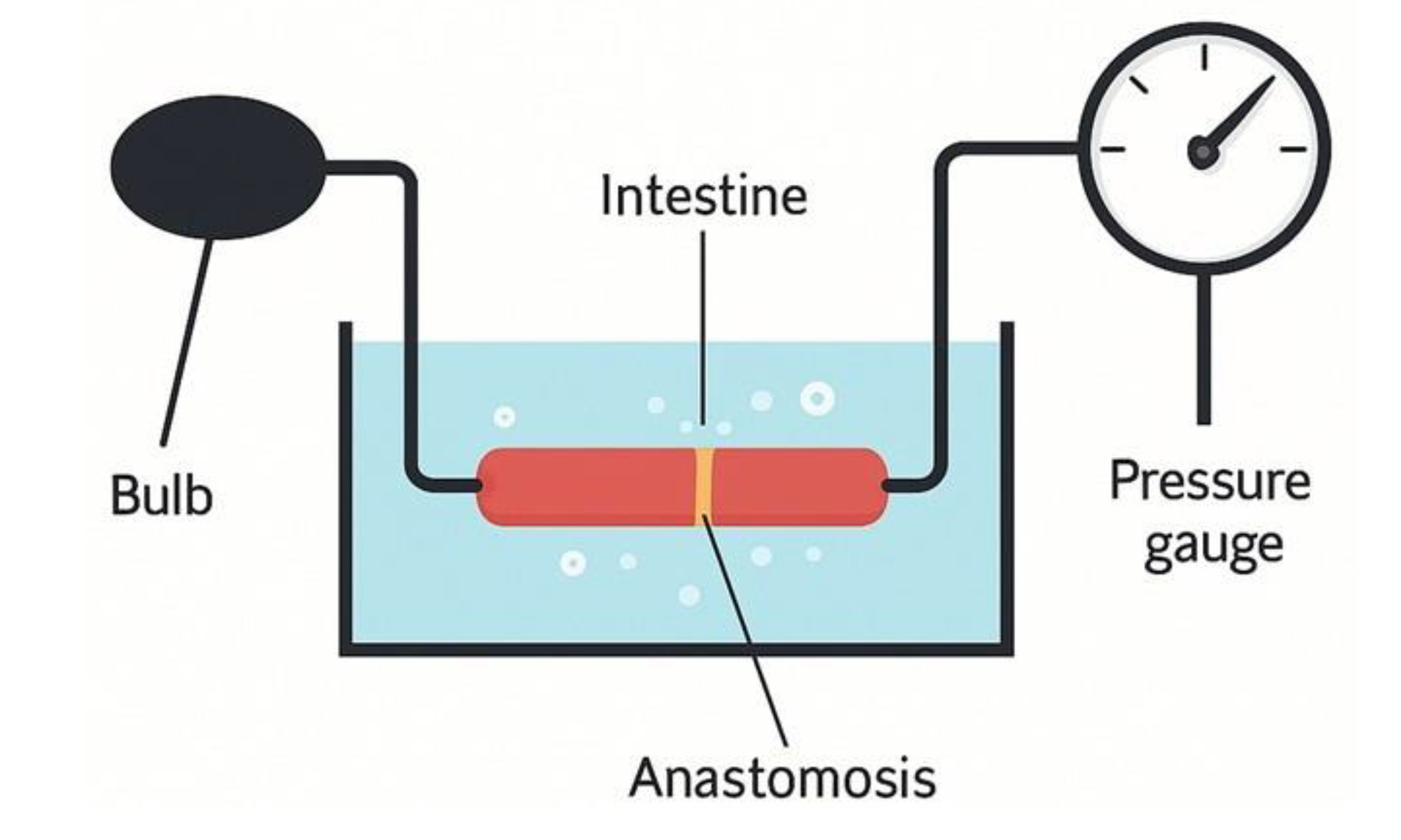

In addition, it was decided to measure the anastomotic bursting pressure as part of the assessment of the anastomotic line, ten days after the initial surgical procedure.

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of the bursting pressure measurement model.

Figure 3.

Schematic illustration of the bursting pressure measurement model.

An illustration simplifying the model we constructed for measuring bursting pressure. On one side, the connection to the pump is shown, and on the other side, the pressure gauge used to measure the bursting pressure inside the intestine (comparing an unoperated intestine with one following surgery).

Table 2.

Bursting pressure measurements according to anastomotic conditions.

Table 2.

Bursting pressure measurements according to anastomotic conditions.

| Bursting pressures |

|

| Intestine without an anastomosis |

›300 |

| Intestine with an intact anastomosis |

145‹ |

| Intestine with an abscess at the anastomotic site |

85‹ |

| Intestine with a perforation |

40‹ |

Bursting pressures were measured in 10 rats from each group:

4. Discussion

Several similar studies in literature address ischemia models of the anastomotic margins in laboratory animals. Pommergaard demonstrated that a murine model closely replicates anastomotic leakage in humans. This model has high clinical relevance, as leakage in the model resembles the outcomes of leakage in humans. They showed, in the murine model, an increased rate of colonic anastomotic leakage when the anastomosis was performed with four absorbable sutures compared to a control group with eight absorbable sutures (40% vs. 0%, p = 0.003). Weight loss was more pronounced, and the vitality index was also significantly lower in these animals (p < 0.001) [

1]. Boersema and colleagues concluded that hyperbaric oxygen therapy improves the healing of ischemic anastomoses in rats and benefits postoperative renal function. They used 40 rats that underwent colectomy with ischemic anastomosis. The rats were divided into a group receiving hyperbaric oxygen treatment (HBOT) for 10 days and a control group without HBOT. In the HBOT group, no anastomotic leakage was observed, compared to a leakage rate of 37.5% in the control group [

2]. Henne-Bruns D. determined that placing a polyglycolic acid (PGA) mesh over the colonic anastomotic line impairs healing in rats, possibly due to reduced contact between the anastomosis and the omentum. In this study, 75 rats underwent transverse colon transection with single-layer anastomosis. In half of the rats, six sutures were placed, and in the other half, four sutures. In half of the animals in each group, a PGA mesh was placed to cover the anastomosis [

3]. In another study in pigs, significant anastomotic separation and marginal ischemia were not reliable predictors for developing intra-abdominal abscess, peritonitis, or sepsis. In this study, 12 pigs underwent end-to-end anastomosis of the descending colon, with ligation of the mesenteric vessels 5 cm from each side of the anastomosis. No clinical leakage was demonstrated, even in animals with maximal ischemia [

4]. A Dutch research group concluded that weight loss and deterioration in the vitality index are good predictors for an anastomotic leakage model in mice. They compared end-to-end colonic anastomosis using 12 interrupted sutures to anastomosis with 5 interrupted sutures. In mice without leakage, there was weight loss for 2–3 days postoperatively, followed by stabilization. In contrast, in mice with leakage, weight loss continued beyond day five. Variability in vitality index values was also observed [

5]. It is evident that there is no consensus among researchers regarding the optimal model for anastomotic leakage, with the main difficulty being the lack of a uniform, consistent rodent model that would allow for significant and efficient follow-up studies. In the present study, we succeeded in creating a clinical model that produces consistent leakage rates in end-to-end colonic anastomoses by ligating the mesocolon at varying lengths on each side of the anastomosis in rats. During the study, we aimed to maintain uniformity across all parameters, including the number of sutures, suture type, rat weight, and other factors, to avoid influencing the results or introducing bias. Anesthesia was achieved with isoflurane gas. All anastomoses were constructed with six sutures using 5-0 coated Vicryl. Following the initial surgical procedure, the rats were given unlimited access to food and water, in addition to analgesics. Notably, no antibiotics were administered. In the control group (rats without mesocolon ligation), the leakage rate was 0%. In the group with 0.2 cm mesocolon ligation on each side of the anastomosis, leakage rate was 19.05%. In the group with 0.4 cm ligation on each side leakage rate was 44.23%. In the last two groups, with ligations of 1 cm and 2 cm on each side, 100% leakage among the few survivors. As shown in the attached tables and diagrams, a consistent leakage rate was observed in the group with 0.4 cm ligation on each side of the mesocolon. In addition, bursting pressure measurements were performed 10 days after anastomosis creation, comparing the control group to the mesocolon-ligation groups. A significant difference was found between unoperated intestines and those after surgery. It should be noted that although differences in bursting pressure were observed among postoperative anastomoses with varying mesocolon ligation lengths, these differences were relatively small. The consistent leakage rate, as described above, can serve for future studies using this model to evaluate the effects of additional variables, such as smoking, antibiotic use, etc. The impact of these factors can be measured according to changes in the leakage rate established in this model. The model we developed appears to have strong potential for testing different approaches and innovative technologies aimed at preventing leakage in colorectal surgery. Possible interventions include prophylactic antibiotic use, biological glues, novel suture materials, blood supply assessment technologies for the anastomosis, and other methods. We consider this model a successful platform for future research.

5. Conclusion

We developed a reliable rat model for colonic anastomotic leak based on mesocolon ischemia. A 0.4 cm bilateral mesocolon ligation yielded reproducible leak rates, supporting its use as a standard for further experimental studies aimed at leak prevention.

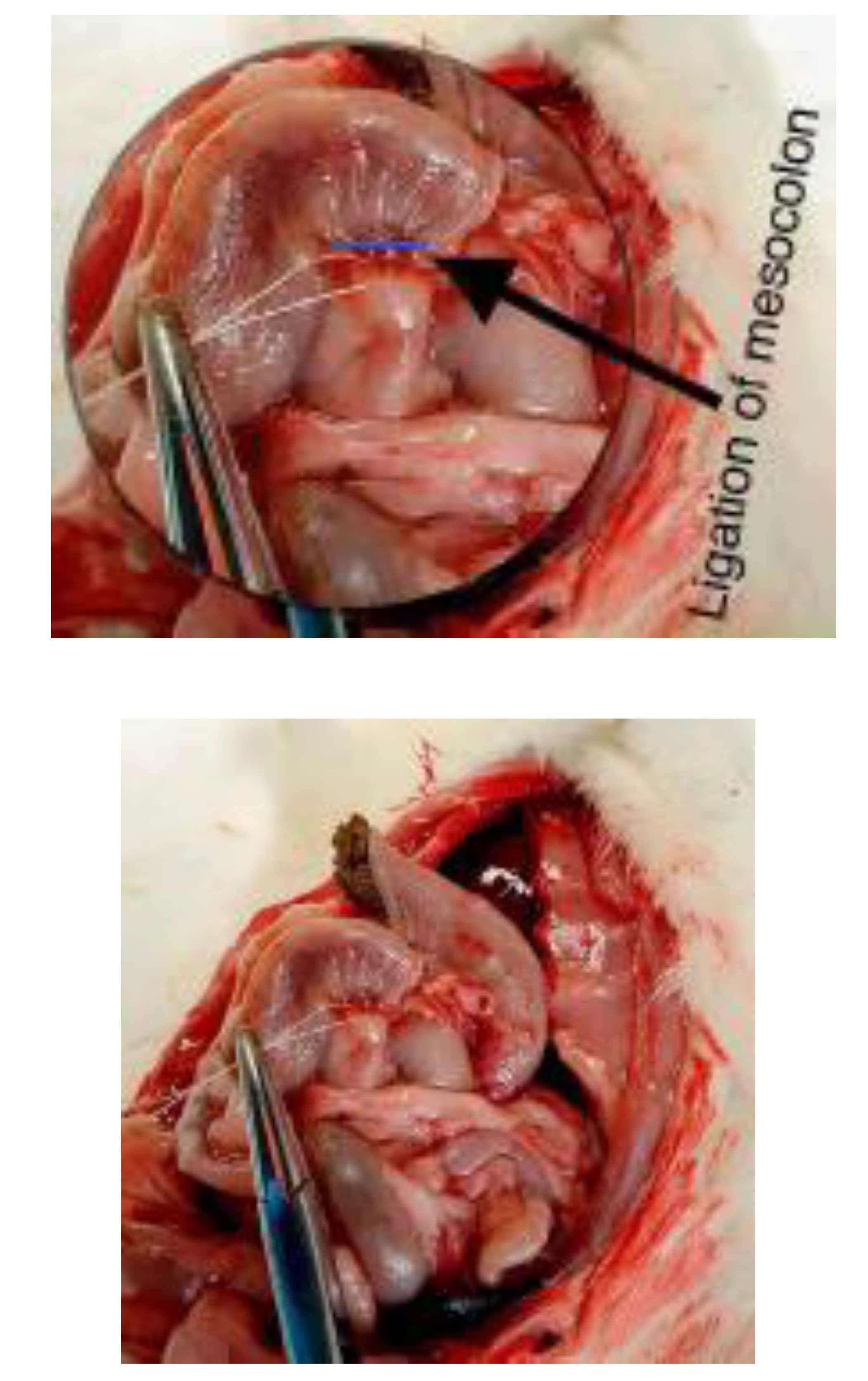

Figure 4.

Measurement of mesocolon ligation length.

Figure 4.

Measurement of mesocolon ligation length.

Intraoperative images 4 and 5 demonstrating measurement of the mesocolon ligation length adjacent to the colonic anastomosis. Precise measurement ensured standardized and reproducible induction of ischemia across experimental groups.

Figure 5.

Measurement of mesocolon ligation length.

Figure 5.

Measurement of mesocolon ligation length.

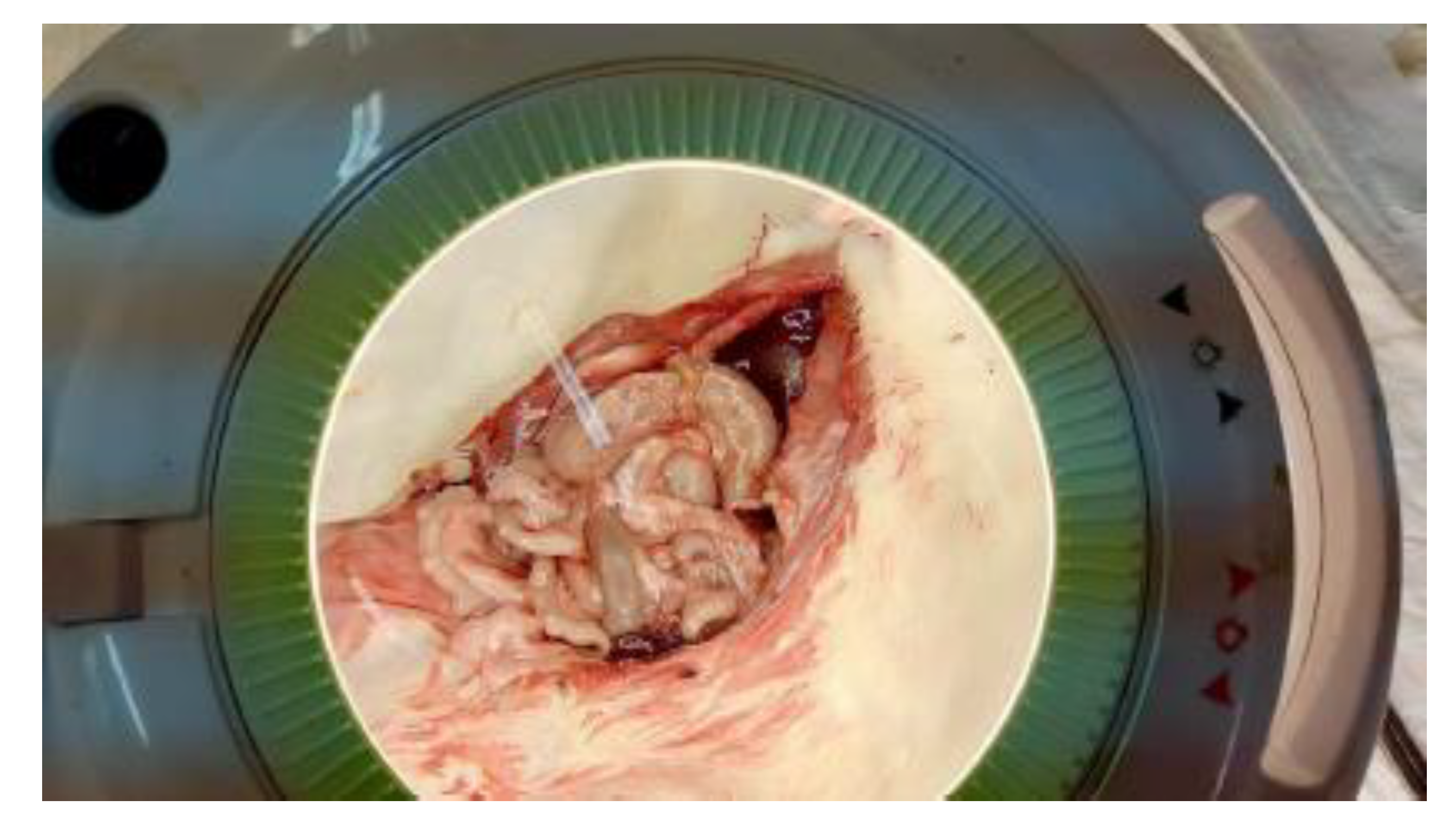

Figure 6.

Postoperative appearance of ischemic colonic anastomosis.

Figure 6.

Postoperative appearance of ischemic colonic anastomosis.

Figure 7.

Postoperative appearance of ischemic colonic anastomosis.

Figure 7.

Postoperative appearance of ischemic colonic anastomosis.

Representative images 6 and 7 showing the colon following mesocolon ligation, with visible anastomotic leakage and associated intra-abdominal abscess formation.

Figure 8.

Macroscopic appearance of the colon after mesocolon ligation.

Figure 8.

Macroscopic appearance of the colon after mesocolon ligation.

Gross specimen of the intestine following mesocolon ligation, demonstrating ischemic changes at the anastomotic site.

Figure 9.

Microscopic image of the anastomotic site.

Figure 9.

Microscopic image of the anastomotic site.

Microscopic image obtained during the procedure, illustrating tissue morphology at the anastomotic site following ischemic injury.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: G.B., I.K.; Methodology: G.B., A.O., I.V.; Investigation: G.B., G.H., I.K., Y.V., E.Q., I.V., N.A., S.Y., D.L., S.A.F.; Data curation: G.B., I.K.; Formal analysis: G.B., I.K.; Writing – original draft: G.B., I.K.; Writing – review & editing: A.O., D.C.; Supervision: D.C. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, Israel. The study protocol was reviewed and approved prior to initiation.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable. This study did not involve human participants.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the staff of the Animal Facility at Soroka University Medical Center for their assistance with animal care and maintenance throughout the study. We also acknowledge the technical support provided by the Department of General Surgery B, Soroka University Medical Center.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pommergaard, Hans-Christian; Achiam, Michael Patrick; Burcharth, Jakob; Rosenberg, Jacob. Impaired Blood Supply in the Colonic Anastomosis in Mice Compromises Healing. Int Surg 2015, 100(1), 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National database for colorectal cancer. Danish colorectal cancer group: Annual report 2009: http://www.dccg.dk/03_Publika tion/02_arsraport_pdf/aarsrapport%20 2009.pdf.

- Boccola, MA; Buettner, PG; Rozen, WM; Siu, SK; Stevenson, AR; Stitz, R; Ho, YH. Risk factors and outcomes for anastomotic leakage in colorectal surgery: a single-institution analysis of 1,576 patients. World J Surg 2011, 35, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borowski, DW; Bradburn, DM; Mills, SJ; Bharathan, B; Wilson, RG; Ratcliffe, AA; Kelly, SB. Volume outcome analysis of colorectal cancer-related outcomes. Br J Surg 2010, 97, 1416–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goriainov, V; Miles, AJ. Anastomotic leak rate and outcome for laparoscopic intra-corporeal stapled anastomosis. J Minim Access Surg 2010, 6, 6–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buchs, NC; Gervaz, P; Secic, M; Bucher, P; Mugnier-Konrad, B; Morel, P. Incidence, consequences, and risk factors for anastomotic dehiscence after colorectal surgery: a prospective monocentric study. Int J Colorectal Dis 2008, 23, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornton, M; Joshi, H; Vimalachandran, C; Heath, R; Carter, P; Gur, U; Rooney, P. Management and outcome of colorectal anastomotic leaks. Int J Colorectal Dis 2011, 26, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akasu, T; Takawa, M; Yamamoto, S; Yamaguchi, T; Fujita, S; Moriya, Y. Risk factors for anastomotic leakage following intersphincteric resection for very low rectal adenocarcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg 2010, 14, 104–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fawcett, A; Shembekar, M; Church, JS; Vashisht, R; Springall, RG; Nott, DM. Smoking, hypertension, and colonic anastomotic healing; a combined clinical and histopathological study. Gut 1996, 38(5), 714–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, MJ; Shin, R; Oh, HK; Park, JW; Jeong, SY; Park, JG. The impact of heavy smoking on anastomotic leakage and stricture after low anterior resection in rectal cancer patients. World J Surg 2011, 35(12), 2806–2810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruschewski, M; Rieger, H; Pohlen, U; Hotz, HG; Buhr, HJ. Risk factors for clinical anastomotic leakage and postoperative mortality in elective surgery for rectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis 2007, 22(8), 919–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peel, AL; Taylor, EW. Proposed definitions for the audit of postoperative infection: a discussion paper. Surgical Infection Study Group. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1991, 73, 385–8. [Google Scholar]

- Henne-Bruns, D; Kreischer, HP; Schmiegelow, P; Kremer, B. Reinforcement of colon anastomoses with polyglycolic acid mesh: an experimental study. Eur Surg Res. 1990, 22, 224–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houston, KA; Rotstein, OD. Fibrin sealant in high-risk colonic anastomoses. Arch Surg. 1988, 123, 230–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Ham, AC; Kort, WJ; Weijma, IM; Jeekel, H. Transient protection of incomplete colonic anastomoses with fibrin sealant: an experimental study in the rat. J Surg Res. 1993, 55, 256–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pommergaard, HC; Rosenberg, J; Scumacher-Petersen, C; Achiam, M. Choosing the best animal species to mimic clinical colon anastomotic leakage in humans: a qualitative systematic review. Eur Surg Res. 2011, 47, 173–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulati, SM; Thusoo, TK; Kakar, A; Iyenger, B; Pandey, KK. Comparative study of free omental, peritoneal, Dacron velour, and marlex mesh reinforcement of large-bowel anastomosis: an experimental study. Dis Colon Rectum 1982, 25, 517–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nordentoft, T; Sorensen, M. Leakage of colon anastomoses: development of an experimental model in pigs. Eur Surg Res. 2007, 39, 14–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pommergaard, Hans-Christian. Experimental evaluation of clinical colon anastomotic leakage. Dan Med J 2014, 61(3), B4821. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).