Submitted:

11 December 2025

Posted:

12 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Related Theories and Technological Developments

1.2. Current Status of Technological Applications and Scenario Adaptability Analysis

2. Statistical Significance of Local Similarity Analysis

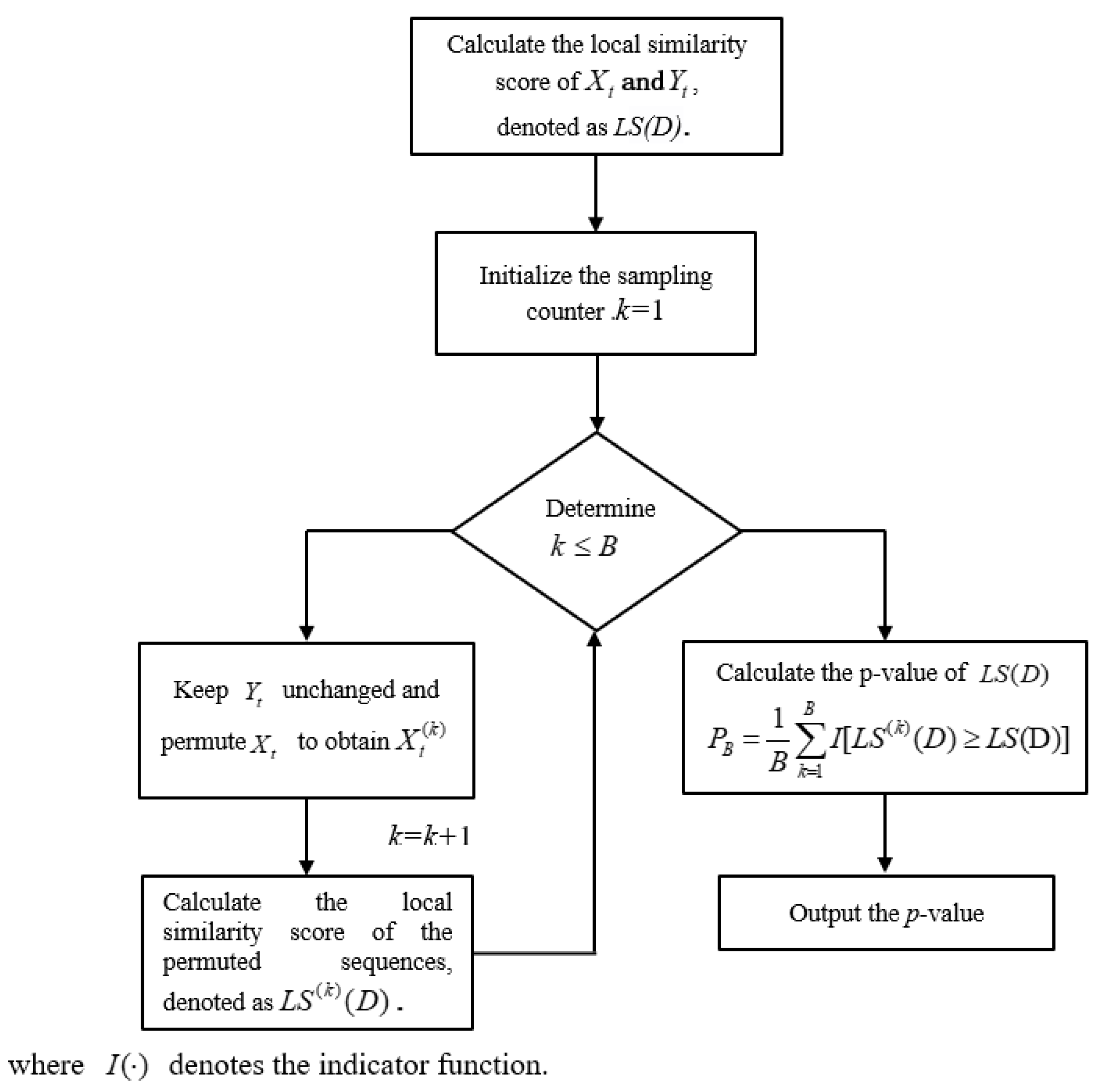

2.1. Permutation Test

2.2. Data-Driven Local Similarity Analysis (DDLSA)

2.3. Theoretical Local Similarity Approximation (TLSA)

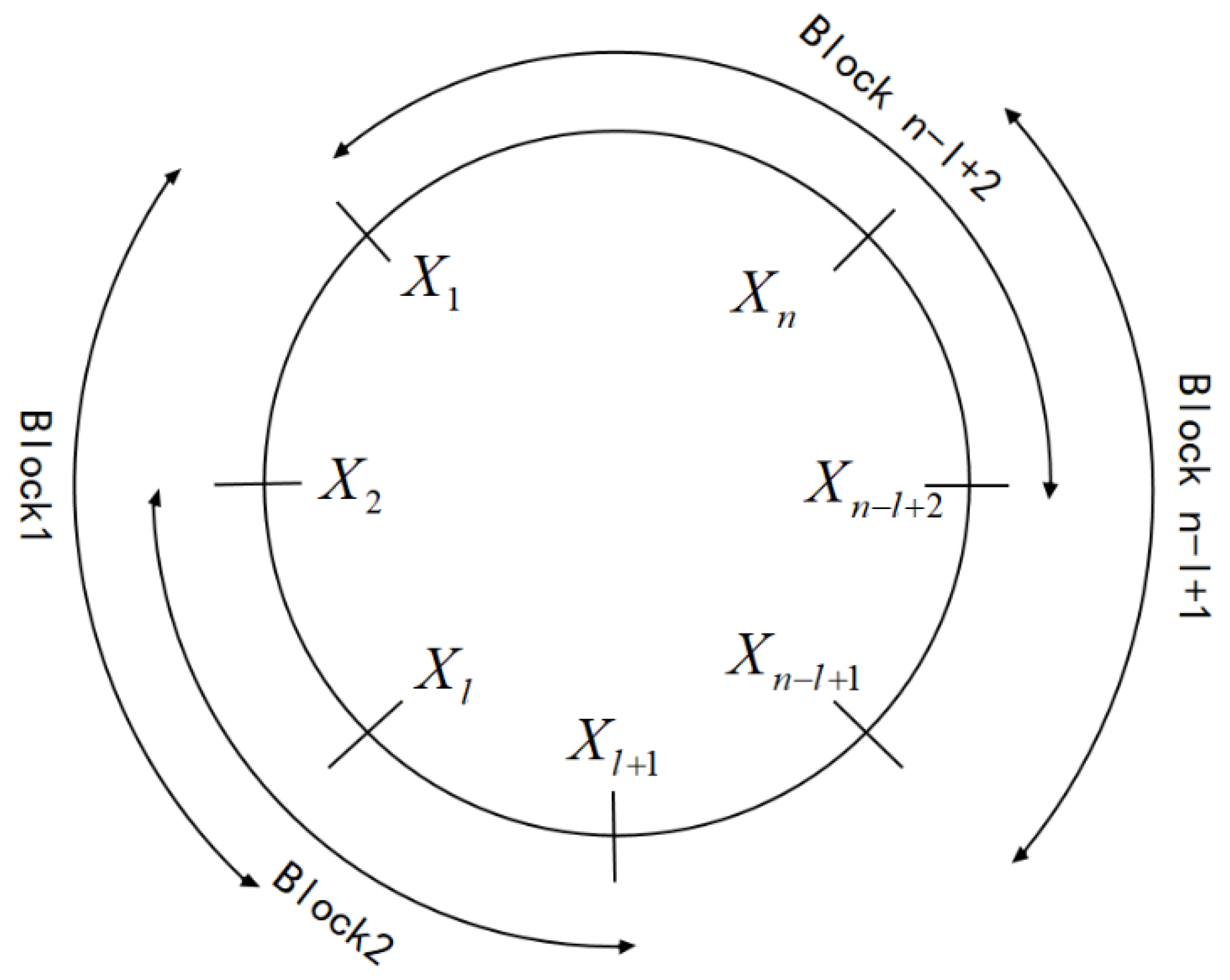

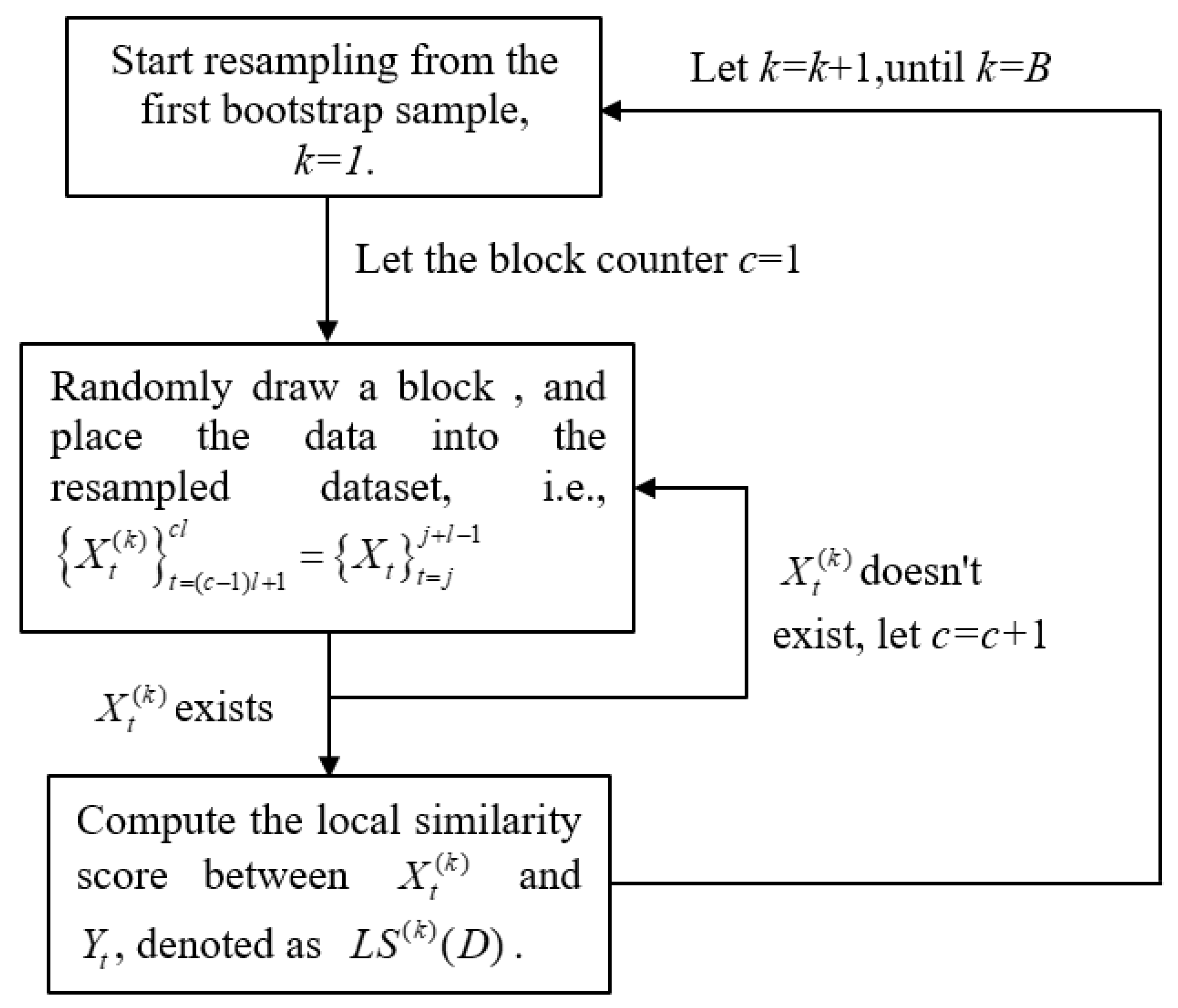

2.4. Moving Block Bootstrap(MBB)

2.5. Circular Moving Block Bootstrap(CMBB)

3. Simulation Study

3.1. Model Specification

3.2. Data Standardization

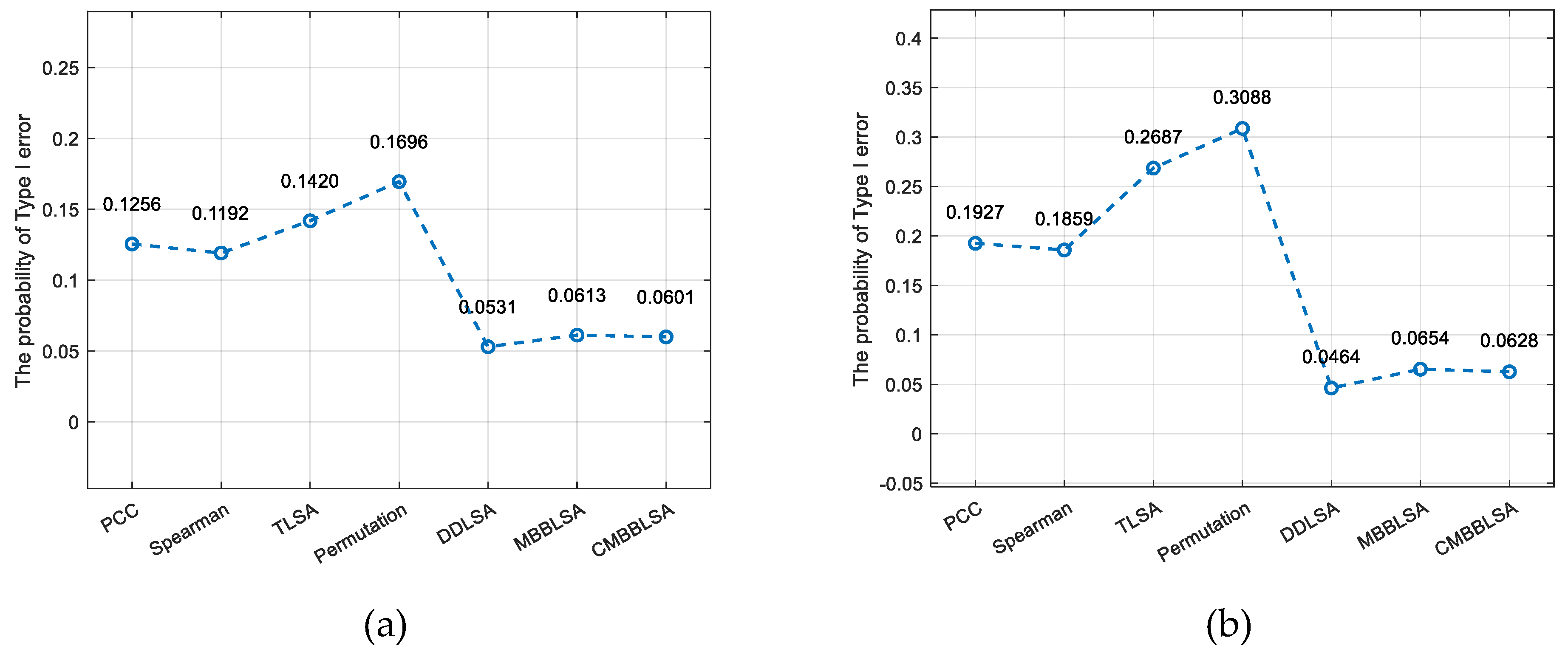

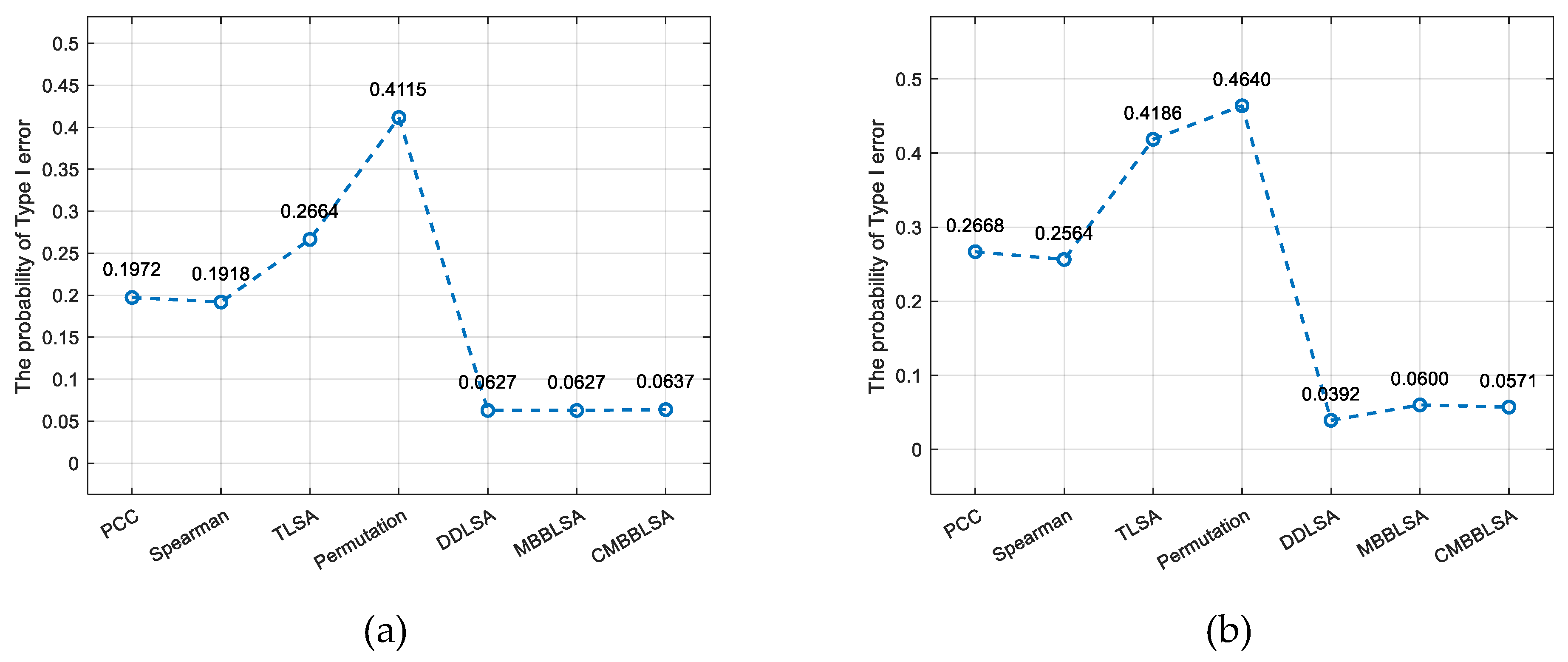

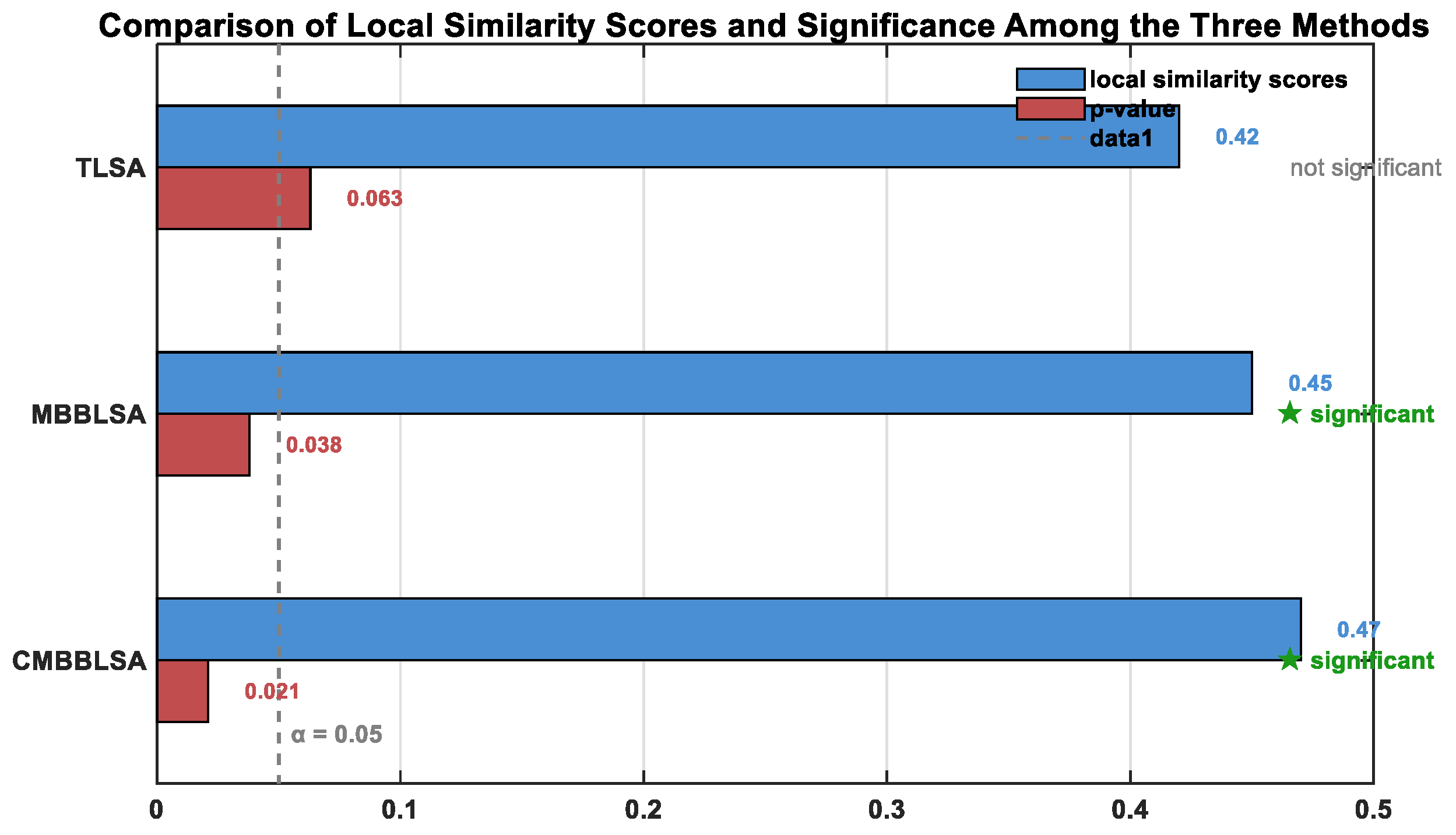

3.3. Analysis of Results

4. Empirical Study

4.1. Dataset Description

4.2. Data Autocorrelation Test

4.3. Method Application and Parameter Settings

5. Conclusion and Prospects

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

Appendix A

| n | PCC | Spearman | TLSA | Permutation | DDLSA | MBBLSA | CMBBLSA | |

| -0.5 -0.5 | 20 | 0.1132 | 0.1105 | 0.0234 | 0.1291 | 0.0113 | 0.0431 | 0.0455 |

| 40 | 0.1188 | 0.1169 | 0.0625 | 0.1379 | 0.0203 | 0.0529 | 0.0506 | |

| 60 | 0.1192 | 0.1197 | 0.0826 | 0.1547 | 0.0291 | 0.0558 | 0.0534 | |

| 80 | 0.1227 | 0.1205 | 0.0983 | 0.1584 | 0.0304 | 0.0571 | 0.0561 | |

| 100 | 0.1247 | 0.1197 | 0.1082 | 0.1602 | 0.0307 | 0.0559 | 0.0541 | |

| 200 | 0.1283 | 0.1207 | 0.1344 | 0.1764 | 0.0381 | 0.0566 | 0.0547 | |

| 300 | 0.1233 | 0.1201 | 0.1425 | 0.1729 | 0.0371 | 0.0545 | 0.0532 | |

| 0 0 | 20 | 0.0506 | 0.0490 | 0.0042 | 0.0473 | 0.0076 | 0.0466 | 0.0491 |

| 40 | 0.0451 | 0.0460 | 0.0130 | 0.0466 | 0.0161 | 0.0408 | 0.0420 | |

| 60 | 0.0516 | 0.0493 | 0.0189 | 0.0481 | 0.0225 | 0.0443 | 0.0457 | |

| 80 | 0.0519 | 0.0527 | 0.0223 | 0.0492 | 0.0248 | 0.0445 | 0.0503 | |

| 100 | 0.0483 | 0.0472 | 0.0243 | 0.0471 | 0.0274 | 0.0441 | 0.0445 | |

| 200 | 0.0475 | 0.0470 | 0.0283 | 0.0452 | 0.0295 | 0.0433 | 0.0442 | |

| 300 | 0.0490 | 0.0493 | 0.0343 | 0.0499 | 0.0352 | 0.0489 | 0.0486 | |

| 0.3 0.3 | 20 | 0.0623 | 0.0590 | 0.0083 | 0.0661 | 0.0100 | 0.0472 | 0.0489 |

| 40 | 0.0650 | 0.0648 | 0.0243 | 0.0751 | 0.0239 | 0.0538 | 0.0531 | |

| 60 | 0.0710 | 0.0677 | 0.0354 | 0.0764 | 0.0314 | 0.0549 | 0.0530 | |

| 80 | 0.0742 | 0.0745 | 0.0415 | 0.0796 | 0.0339 | 0.0551 | 0.0549 | |

| 100 | 0.0668 | 0.0666 | 0.0436 | 0.0767 | 0.0347 | 0.0536 | 0.0525 | |

| 200 | 0.0724 | 0.0708 | 0.0577 | 0.0848 | 0.0402 | 0.0531 | 0.0526 | |

| 300 | 0.0735 | 0.0735 | 0.0627 | 0.0826 | 0.0430 | 0.0525 | 0.0505 | |

| 0.3 0.5 | 20 | 0.0801 | 0.0809 | 0.0111 | 0.0879 | 0.0144 | 0.0604 | 0.0601 |

| 40 | 0.0867 | 0.0840 | 0.0360 | 0.0935 | 0.0275 | 0.0635 | 0.0601 | |

| 60 | 0.0877 | 0.0851 | 0.0474 | 0.1005 | 0.0320 | 0.0608 | 0.0574 | |

| 80 | 0.1464 | 0.1473 | 0.0343 | 0.1525 | 0.0157 | 0.0598 | 0.0592 | |

| 100 | 0.0918 | 0.0870 | 0.0637 | 0.1042 | 0.0375 | 0.0614 | 0.0592 | |

| 200 | 0.0900 | 0.0879 | 0.0768 | 0.1084 | 0.0427 | 0.0592 | 0.0577 | |

| 300 | 0.0872 | 0.0869 | 0.0821 | 0.1098 | 0.0391 | 0.0577 | 0.0553 | |

| 0.5 0.5 | 20 | 0.1036 | 0.1020 | 0.0196 | 0.1139 | 0.0175 | 0.0696 | 0.0653 |

| 40 | 0.1184 | 0.1147 | 0.0589 | 0.135 | 0.0327 | 0.0660 | 0.0656 | |

| 60 | 0.1251 | 0.1196 | 0.0807 | 0.146 | 0.0355 | 0.0667 | 0.0665 | |

| 80 | 0.1177 | 0.1151 | 0.0900 | 0.1438 | 0.0353 | 0.0624 | 0.0603 | |

| 100 | 0.1268 | 0.1237 | 0.0985 | 0.1547 | 0.0358 | 0.0570 | 0.0543 | |

| 200 | 0.1295 | 0.1267 | 0.1331 | 0.1722 | 0.0398 | 0.0583 | 0.0581 | |

| 300 | 0.1356 | 0.1315 | 0.1476 | 0.1836 | 0.0404 | 0.0595 | 0.0588 | |

| 0.5 0.8 | 20 | 0.1498 | 0.1514 | 0.0322 | 0.1544 | 0.0183 | 0.0768 | 0.0673 |

| 40 | 0.1688 | 0.1674 | 0.0966 | 0.1874 | 0.0279 | 0.0712 | 0.0684 | |

| 60 | 0.1730 | 0.1711 | 0.1278 | 0.208 | 0.0268 | 0.0772 | 0.0720 | |

| 80 | 0.1830 | 0.1807 | 0.1756 | 0.2255 | 0.0283 | 0.0765 | 0.0731 | |

| 100 | 0.1824 | 0.1781 | 0.1700 | 0.2339 | 0.0297 | 0.0706 | 0.0702 | |

| 200 | 0.1918 | 0.1841 | 0.2198 | 0.2647 | 0.0323 | 0.0701 | 0.0664 | |

| 300 | 0.1994 | 0.1913 | 0.2427 | 0.283 | 0.0317 | 0.0680 | 0.0670 |

| n | PCC | Spearman | TLSA | Permutation | DDLSA | MBBLSA | CMBBLSA | |

| -0.5 -0.5 | 20 | 0.1138 | 0.1137 | 0.1041 | 0.1302 | 0.0054 | 0.0331 | 0.0356 |

| 40 | 0.1138 | 0.1116 | 0.0545 | 0.1532 | 0.0160 | 0.0444 | 0.0476 | |

| 60 | 0.1216 | 0.1200 | 0.0885 | 0.1664 | 0.0287 | 0.0592 | 0.0566 | |

| 80 | 0.1265 | 0.1235 | 0.1050 | 0.1755 | 0.0311 | 0.0587 | 0.0578 | |

| 100 | 0.1182 | 0.1150 | 0.1089 | 0.1728 | 0.0289 | 0.0497 | 0.0530 | |

| 200 | 0.1361 | 0.1312 | 0.1553 | 0.2009 | 0.0372 | 0.0598 | 0.0590 | |

| 300 | 0.1336 | 0.1263 | 0.1600 | 0.2007 | 0.0345 | 0.0556 | 0.0548 | |

| 0 0 | 20 | 0.0492 | 0.0497 | 0.0023 | 0.0508 | 0.0048 | 0.0377 | 0.0359 |

| 40 | 0.0487 | 0.0476 | 0.0127 | 0.0506 | 0.0175 | 0.0443 | 0.0455 | |

| 60 | 0.0495 | 0.0492 | 0.0185 | 0.0512 | 0.0221 | 0.0458 | 0.0466 | |

| 80 | 0.0446 | 0.0473 | 0.0197 | 0.0464 | 0.0228 | 0.0418 | 0.0417 | |

| 100 | 0.0500 | 0.0486 | 0.0228 | 0.0471 | 0.0254 | 0.0435 | 0.0443 | |

| 200 | 0.0532 | 0.0493 | 0.0314 | 0.0523 | 0.0333 | 0.0510 | 0.0491 | |

| 300 | 0.0483 | 0.0484 | 0.0351 | 0.0502 | 0.0366 | 0.0501 | 0.0503 | |

| 0.3 0.3 | 20 | 0.0614 | 0.0617 | 0.0036 | 0.0672 | 0.0058 | 0.0441 | 0.0444 |

| 40 | 0.0677 | 0.0642 | 0.0206 | 0.0755 | 0.0200 | 0.0487 | 0.0523 | |

| 60 | 0.0694 | 0.0670 | 0.0321 | 0.0814 | 0.0268 | 0.0543 | 0.0540 | |

| 80 | 0.0707 | 0.0717 | 0.0386 | 0.0834 | 0.0299 | 0.0538 | 0.0519 | |

| 100 | 0.0715 | 0.0704 | 0.0482 | 0.0886 | 0.0358 | 0.0586 | 0.0566 | |

| 200 | 0.0726 | 0.0718 | 0.0616 | 0.0935 | 0.0451 | 0.0593 | 0.0571 | |

| 300 | 0.0756 | 0.0721 | 0.0665 | 0.0912 | 0.0449 | 0.0541 | 0.0537 | |

| 0.3 0.5 | 20 | 0.0762 | 0.0786 | 0.0065 | 0.0878 | 0.0074 | 0.0540 | 0.0532 |

| 40 | 0.0866 | 0.0865 | 0.0274 | 0.0948 | 0.0206 | 0.0558 | 0.0528 | |

| 60 | 0.0891 | 0.0887 | 0.0472 | 0.1045 | 0.0290 | 0.0625 | 0.0593 | |

| 80 | 0.0889 | 0.0866 | 0.0521 | 0.1084 | 0.0324 | 0.0590 | 0.0555 | |

| 100 | 0.0875 | 0.0856 | 0.0624 | 0.1096 | 0.0355 | 0.0596 | 0.0556 | |

| 200 | 0.0900 | 0.0883 | 0.0847 | 0.1220 | 0.0407 | 0.0591 | 0.0584 | |

| 300 | 0.0895 | 0.0869 | 0.0919 | 0.1210 | 0.0410 | 0.0564 | 0.0558 | |

| 0.5 0.5 | 20 | 0.1036 | 0.1029 | 0.0126 | 0.1168 | 0.0099 | 0.0566 | 0.0533 |

| 40 | 0.1116 | 0.1111 | 0.0531 | 0.1481 | 0.0243 | 0.0608 | 0.0602 | |

| 60 | 0.1170 | 0.1155 | 0.0810 | 0.1559 | 0.0331 | 0.0621 | 0.0620 | |

| 80 | 0.1209 | 0.1186 | 0.0936 | 0.1620 | 0.0368 | 0.0619 | 0.0582 | |

| 100 | 0.1208 | 0.1175 | 0.1063 | 0.1691 | 0.0361 | 0.0648 | 0.0627 | |

| 200 | 0.1277 | 0.1248 | 0.1467 | 0.1894 | 0.0414 | 0.0632 | 0.0614 | |

| 300 | 0.1224 | 0.1203 | 0.1550 | 0.1936 | 0.0357 | 0.0590 | 0.0584 | |

| 0.5 0.8 | 20 | 0.1460 | 0.1510 | 0.0244 | 0.1674 | 0.0109 | 0.0793 | 0.0790 |

| 40 | 0.1685 | 0.1691 | 0.0943 | 0.2099 | 0.0239 | 0.0795 | 0.0731 | |

| 60 | 0.1809 | 0.1791 | 0.1311 | 0.2251 | 0.0227 | 0.0756 | 0.0705 | |

| 80 | 0.1727 | 0.1736 | 0.1577 | 0.2405 | 0.0240 | 0.0734 | 0.0720 | |

| 100 | 0.1833 | 0.1788 | 0.1813 | 0.2586 | 0.0269 | 0.0757 | 0.0715 | |

| 200 | 0.1891 | 0.1854 | 0.2341 | 0.2922 | 0.0288 | 0.0697 | 0.0672 | |

| 300 | 0.1944 | 0.1882 | 0.2575 | 0.3000 | 0.0287 | 0.0685 | 0.0670 |

| n | PCC | Spearman | TLSA | Permutation | DDLSA | MBBLSA | CMBBLSA | |

| -0.5 -0.5 | 20 | 0.1103 | 0.1114 | 0.0103 | 0.1411 | 0.0045 | 0.0348 | 0.0360 |

| 40 | 0.1158 | 0.1132 | 0.0576 | 0.1671 | 0.0179 | 0.0467 | 0.0504 | |

| 60 | 0.1238 | 0.1185 | 0.0855 | 0.1821 | 0.0223 | 0.0517 | 0.0499 | |

| 80 | 0.1303 | 0.1278 | 0.1016 | 0.1871 | 0.0277 | 0.0553 | 0.0526 | |

| 100 | 0.1256 | 0.1229 | 0.1201 | 0.1951 | 0.0310 | 0.0547 | 0.0540 | |

| 200 | 0.1479 | 0.1246 | 0.1601 | 0.2127 | 0.0341 | 0.0594 | 0.0545 | |

| 300 | 0.1336 | 0.1263 | 0.1734 | 0.2183 | 0.0350 | 0.0593 | 0.0511 | |

| 0 0 | 20 | 0.0507 | 0.0513 | 0.0012 | 0.0478 | 0.0028 | 0.0337 | 0.0407 |

| 40 | 0.0489 | 0.0479 | 0.0080 | 0.0511 | 0.0109 | 0.0409 | 0.0405 | |

| 60 | 0.0481 | 0.0498 | 0.0145 | 0.0513 | 0.0182 | 0.0450 | 0.0448 | |

| 80 | 0.0501 | 0.0527 | 0.0183 | 0.0513 | 0.0215 | 0.0507 | 0.0501 | |

| 100 | 0.0487 | 0.0467 | 0.0218 | 0.0589 | 0.0240 | 0.0445 | 0.0496 | |

| 200 | 0.0474 | 0.0483 | 0.0327 | 0.0524 | 0.0347 | 0.0497 | 0.0510 | |

| 300 | 0.0503 | 0.0498 | 0.0343 | 0.0475 | 0.0358 | 0.0423 | 0.0497 | |

| 0.3 0.3 | 20 | 0.0668 | 0.0654 | 0.0024 | 0.0741 | 0.0031 | 0.0411 | 0.0435 |

| 40 | 0.0742 | 0.0742 | 0.0194 | 0.0847 | 0.0178 | 0.0543 | 0.0518 | |

| 60 | 0.0704 | 0.0680 | 0.0287 | 0.0850 | 0.0250 | 0.0540 | 0.0527 | |

| 80 | 0.0772 | 0.0741 | 0.0409 | 0.0909 | 0.0327 | 0.0575 | 0.0552 | |

| 100 | 0.0683 | 0.0639 | 0.0442 | 0.0906 | 0.0347 | 0.0591 | 0.0539 | |

| 200 | 0.0720 | 0.0746 | 0.0619 | 0.0921 | 0.0425 | 0.0576 | 0.0559 | |

| 300 | 0.0756 | 0.0721 | 0.0679 | 0.0934 | 0.0433 | 0.0589 | 0.0520 | |

| 0.3 0.5 | 20 | 0.0766 | 0.0767 | 0.0043 | 0.0876 | 0.0048 | 0.0487 | 0.0487 |

| 40 | 0.0842 | 0.0827 | 0.0282 | 0.1014 | 0.0220 | 0.0590 | 0.0566 | |

| 60 | 0.0878 | 0.0885 | 0.0444 | 0.1211 | 0.0273 | 0.0715 | 0.0689 | |

| 80 | 0.0846 | 0.0849 | 0.0583 | 0.1167 | 0.0328 | 0.0657 | 0.0603 | |

| 100 | 0.0876 | 0.0854 | 0.0644 | 0.1259 | 0.0370 | 0.0712 | 0.0668 | |

| 200 | 0.0923 | 0.0886 | 0.0837 | 0.1233 | 0.0410 | 0.0614 | 0.0563 | |

| 300 | 0.0896 | 0.0859 | 0.0954 | 0.1272 | 0.0408 | 0.0572 | 0.0512 | |

| 0.5 0.5 | 20 | 0.1010 | 0.1033 | 0.0070 | 0.1245 | 0.0068 | 0.0528 | 0.0517 |

| 40 | 0.1102 | 0.1094 | 0.0488 | 0.1620 | 0.0226 | 0.0602 | 0.0591 | |

| 60 | 0.1199 | 0.1188 | 0.0764 | 0.1705 | 0.0314 | 0.0628 | 0.0625 | |

| 80 | 0.1199 | 0.1190 | 0.0970 | 0.1821 | 0.0324 | 0.0595 | 0.0588 | |

| 100 | 0.1270 | 0.1243 | 0.1181 | 0.1889 | 0.0381 | 0.0650 | 0.0629 | |

| 200 | 0.1199 | 0.1156 | 0.1480 | 0.1998 | 0.0372 | 0.0588 | 0.0576 | |

| 300 | 0.0474 | 0.1197 | 0.1562 | 0.2014 | 0.0391 | 0.0596 | 0.0589 | |

| 0.5 0.8 | 20 | 0.1473 | 0.1482 | 0.0181 | 0.1820 | 0.0084 | 0.0719 | 0.0711 |

| 40 | 0.1639 | 0.1711 | 0.0947 | 0.2290 | 0.0201 | 0.0821 | 0.0769 | |

| 60 | 0.1800 | 0.1739 | 0.1331 | 0.2450 | 0.0219 | 0.0730 | 0.0704 | |

| 80 | 0.1825 | 0.1797 | 0.1703 | 0.2629 | 0.0211 | 0.0737 | 0.0697 | |

| 100 | 0.1871 | 0.1825 | 0.1838 | 0.2663 | 0.0238 | 0.0712 | 0.0688 | |

| 200 | 0.1871 | 0.1834 | 0.2425 | 0.3018 | 0.0263 | 0.0671 | 0.0669 | |

| 300 | 0.1989 | 0.1968 | 0.2176 | 0.3266 | 0.0271 | 0.0688 | 0.0680 |

| n | PCC | Spearman | TLSA | Permutation | DDLSA | MBBLSA | CMBBLSA | |

| -0.5 -0.5 | 20 | 0.0481 | 0.0462 | 0.0047 | 0.0478 | 0.0091 | 0.0407 | 0.0374 |

| 40 | 0.0501 | 0.0495 | 0.0147 | 0.0505 | 0.02 | 0.0448 | 0.0438 | |

| 60 | 0.0531 | 0.0521 | 0.0208 | 0.0515 | 0.0238 | 0.0478 | 0.048 | |

| 80 | 0.0476 | 0.0478 | 0.0209 | 0.0477 | 0.0242 | 0.0448 | 0.045 | |

| 100 | 0.0494 | 0.0497 | 0.0251 | 0.0506 | 0.0272 | 0.0465 | 0.0481 | |

| 200 | 0.0531 | 0.0507 | 0.0316 | 0.0487 | 0.033 | 0.0477 | 0.0474 | |

| 300 | 0.0513 | 0.0515 | 0.0362 | 0.0508 | 0.0369 | 0.0485 | 0.0483 | |

| 0 0 | 20 | 0.0817 | 0.0811 | 0.0114 | 0.093 | 0.0131 | 0.0597 | 0.0581 |

| 40 | 0.0892 | 0.0842 | 0.039 | 0.1052 | 0.0317 | 0.064 | 0.062 | |

| 60 | 0.0846 | 0.0821 | 0.0526 | 0.1072 | 0.0364 | 0.0618 | 0.0572 | |

| 80 | 0.0873 | 0.0838 | 0.0624 | 0.109 | 0.0378 | 0.0619 | 0.0586 | |

| 100 | 0.0901 | 0.0869 | 0.0679 | 0.1132 | 0.0398 | 0.0594 | 0.057 | |

| 200 | 0.0876 | 0.0871 | 0.078 | 0.1116 | 0.041 | 0.0557 | 0.0538 | |

| 300 | 0.0848 | 0.0839 | 0.0889 | 0.1144 | 0.0406 | 0.0559 | 0.0559 | |

| 0.3 0.3 | 20 | 0.1232 | 0.1222 | 0.026 | 0.1475 | 0.0159 | 0.0686 | 0.064 |

| 40 | 0.1306 | 0.1285 | 0.0731 | 0.1632 | 0.0275 | 0.0606 | 0.0587 | |

| 60 | 0.1357 | 0.1324 | 0.1015 | 0.1785 | 0.0311 | 0.0615 | 0.0583 | |

| 80 | 0.1354 | 0.1365 | 0.1172 | 0.1863 | 0.0296 | 0.0595 | 0.0587 | |

| 100 | 0.1379 | 0.1339 | 0.1426 | 0.1945 | 0.032 | 0.061 | 0.0574 | |

| 200 | 0.1395 | 0.1343 | 0.1598 | 0.2052 | 0.0351 | 0.0565 | 0.0559 | |

| 300 | 0.1385 | 0.1332 | 0.1703 | 0.207 | 0.0346 | 0.0594 | 0.0579 | |

| 0.3 0.5 | 20 | 0.1481 | 0.1482 | 0.0358 | 0.1682 | 0.0155 | 0.0719 | 0.0683 |

| 40 | 0.1591 | 0.1571 | 0.1014 | 0.199 | 0.026 | 0.0692 | 0.0688 | |

| 60 | 0.1582 | 0.1546 | 0.1251 | 0.2097 | 0.0232 | 0.0636 | 0.0623 | |

| 80 | 0.1607 | 0.1572 | 0.1445 | 0.2222 | 0.0276 | 0.0649 | 0.0635 | |

| 100 | 0.156 | 0.155 | 0.1601 | 0.2247 | 0.0276 | 0.0599 | 0.0572 | |

| 200 | 0.1624 | 0.1558 | 0.1967 | 0.2453 | 0.0309 | 0.061 | 0.0601 | |

| 300 | 0.1957 | 0.1901 | 0.2559 | 0.307 | 0.042 | 0.0567 | 0.0564 | |

| 0.5 0.5 | 20 | 0.1796 | 0.18 | 0.0536 | 0.2037 | 0.016 | 0.0857 | 0.068 |

| 40 | 0.1858 | 0.1853 | 0.1267 | 0.2367 | 0.0216 | 0.0676 | 0.0621 | |

| 60 | 0.1924 | 0.1902 | 0.1695 | 0.2574 | 0.0223 | 0.0647 | 0.0647 | |

| 80 | 0.1886 | 0.184 | 0.1842 | 0.2655 | 0.0223 | 0.0575 | 0.0562 | |

| 100 | 0.1973 | 0.1898 | 0.2107 | 0.3074 | 0.0264 | 0.0611 | 0.0608 | |

| 200 | 0.1984 | 0.19 | 0.256 | 0.3389 | 0.028 | 0.058 | 0.0579 | |

| 300 | 0.1964 | 0.1917 | 0.2815 | 0.354 | 0.0282 | 0.0571 | 0.0558 | |

| 0.5 0.8 | 20 | 0.2251 | 0.2276 | 0.0754 | 0.2456 | 0.0112 | 0.0994 | 0.0826 |

| 40 | 0.2493 | 0.2463 | 0.1714 | 0.2907 | 0.0122 | 0.0754 | 0.0711 | |

| 60 | 0.2503 | 0.2474 | 0.2217 | 0.3239 | 0.016 | 0.0736 | 0.0713 | |

| 80 | 0.2557 | 0.253 | 0.2599 | 0.3961 | 0.0157 | 0.0689 | 0.0666 | |

| 100 | 0.2556 | 0.2587 | 0.2743 | 0.4038 | 0.019 | 0.065 | 0.064 | |

| 200 | 0.2604 | 0.2519 | 0.3452 | 0.4011 | 0.0229 | 0.0625 | 0.062 | |

| 300 | 0.2674 | 0.2618 | 0.3802 | 0.4948 | 0.0242 | 0.0639 | 0.0638 |

| n | PCC | Spearman | TLSA | Permutation | DDLSA | MBBLSA | CMBBLSA | |

| -0.5 -0.5 | 20 | 0.0499 | 0.0466 | 0.015 | 0.0589 | 0.0124 | 0.056 | 0.0407 |

| 40 | 0.0561 | 0.047 | 0.0157 | 0.058 | 0.0147 | 0.0556 | 0.0561 | |

| 60 | 0.0556 | 0.0505 | 0.0251 | 0.0582 | 0.0167 | 0.057 | 0.0569 | |

| 80 | 0.0521 | 0.0511 | 0.0276 | 0.0595 | 0.0284 | 0.0581 | 0.0577 | |

| 100 | 0.0543 | 0.0499 | 0.0249 | 0.06 | 0.0295 | 0.0453 | 0.0555 | |

| 200 | 0.0555 | 0.0531 | 0.0345 | 0.0664 | 0.0339 | 0.0402 | 0.0591 | |

| 300 | 0.0502 | 0.0495 | 0.0362 | 0.0663 | 0.0352 | 0.0552 | 0.0465 | |

| 0 0 | 20 | 0.0729 | 0.0775 | 0.0291 | 0.0821 | 0.0379 | 0.0579 | 0.0558 |

| 40 | 0.0855 | 0.0808 | 0.0379 | 0.0914 | 0.049 | 0.059 | 0.0581 | |

| 60 | 0.0887 | 0.0875 | 0.0439 | 0.0971 | 0.058 | 0.058 | 0.0592 | |

| 80 | 0.093 | 0.0844 | 0.0698 | 0.0965 | 0.0415 | 0.0615 | 0.0602 | |

| 100 | 0.084 | 0.0875 | 0.0707 | 0.1369 | 0.0521 | 0.0621 | 0.0615 | |

| 200 | 0.0815 | 0.0903 | 0.0801 | 0.1045 | 0.055 | 0.065 | 0.0641 | |

| 300 | 0.0905 | 0.0869 | 0.0895 | 0.1571 | 0.0565 | 0.0665 | 0.0658 | |

| 0.3 0.3 | 20 | 0.106 | 0.1012 | 0.1117 | 0.1537 | 0.0198 | 0.0198 | 0.0362 |

| 40 | 0.137 | 0.1172 | 0.1273 | 0.1709 | 0.0205 | 0.0205 | 0.0595 | |

| 60 | 0.131 | 0.1157 | 0.1246 | 0.2001 | 0.0192 | 0.0192 | 0.0577 | |

| 80 | 0.1303 | 0.116 | 0.1265 | 0.2256 | 0.0231 | 0.0231 | 0.0571 | |

| 100 | 0.1285 | 0.1197 | 0.1248 | 0.2348 | 0.0259 | 0.0259 | 0.0595 | |

| 200 | 0.1293 | 0.1207 | 0.1274 | 0.2571 | 0.0258 | 0.0258 | 0.0585 | |

| 300 | 0.1251 | 0.1204 | 0.1239 | 0.2793 | 0.0363 | 0.0263 | 0.0655 | |

| 0.3 0.5 | 20 | 0.1367 | 0.1371 | 0.0613 | 0.1214 | 0.0362 | 0.0607 | 0.0569 |

| 40 | 0.1287 | 0.121 | 0.0843 | 0.1351 | 0.0441 | 0.0592 | 0.0591 | |

| 60 | 0.1256 | 0.1342 | 0.1188 | 0.1572 | 0.0483 | 0.0586 | 0.0611 | |

| 80 | 0.1452 | 0.1449 | 0.1398 | 0.1408 | 0.0519 | 0.0625 | 0.0626 | |

| 100 | 0.1489 | 0.1464 | 0.1556 | 0.1594 | 0.0516 | 0.0619 | 0.0622 | |

| 200 | 0.1309 | 0.1549 | 0.1918 | 0.2036 | 0.0552 | 0.0631 | 0.0632 | |

| 300 | 0.1571 | 0.1687 | 0.2217 | 0.2228 | 0.0535 | 0.0623 | 0.0625 | |

| 0.5 0.5 | 20 | 0.1532 | 0.1781 | 0.0997 | 0.184 | 0.0167 | 0.0856 | 0.0595 |

| 40 | 0.1929 | 0.1836 | 0.1404 | 0.2503 | 0.0183 | 0.0535 | 0.0577 | |

| 60 | 0.1946 | 0.1844 | 0.1872 | 0.301 | 0.0293 | 0.0596 | 0.0571 | |

| 80 | 0.1982 | 0.1953 | 0.1927 | 0.3382 | 0.0376 | 0.0611 | 0.0695 | |

| 100 | 0.2082 | 0.1891 | 0.2039 | 0.3708 | 0.0243 | 0.0638 | 0.0585 | |

| 200 | 0.1983 | 0.1999 | 0.1965 | 0.488 | 0.0353 | 0.0634 | 0.0655 | |

| 300 | 0.1948 | 0.2047 | 0.2642 | 0.4743 | 0.0336 | 0.0639 | 0.0658 | |

| 0.5 0.8 | 20 | 0.2238 | 0.1994 | 0.1663 | 0.2868 | 0.0115 | 0.0994 | 0.0813 |

| 40 | 0.2495 | 0.2294 | 0.2099 | 0.2602 | 0.0142 | 0.0892 | 0.0721 | |

| 60 | 0.2495 | 0.2235 | 0.2359 | 0.3054 | 0.0248 | 0.0686 | 0.0741 | |

| 80 | 0.2506 | 0.2494 | 0.2624 | 0.3425 | 0.0262 | 0.0625 | 0.0622 | |

| 100 | 0.2661 | 0.2551 | 0.2775 | 0.3745 | 0.0244 | 0.0619 | 0.0671 | |

| 200 | 0.2419 | 0.2565 | 0.3558 | 0.4853 | 0.0341 | 0.0631 | 0.0734 | |

| 300 | 0.2663 | 0.2677 | 0.4087 | 0.5704 | 0.0244 | 0.0623 | 0.0625 |

| n | PCC | Spearman | TLSA | Permutation | DDLSA | MBBLSA | CMBBLSA | |

| -0.5 -0.5 | 20 | 0.0482 | 0.0465 | 0.0117 | 0.0457 | 0.0246 | 0.0546 | 0.0569 |

| 40 | 0.0561 | 0.0495 | 0.0301 | 0.0462 | 0.0283 | 0.0583 | 0.0576 | |

| 60 | 0.0555 | 0.0514 | 0.0219 | 0.0507 | 0.035 | 0.055 | 0.0575 | |

| 80 | 0.0491 | 0.0488 | 0.0174 | 0.0472 | 0.0204 | 0.0436 | 0.0431 | |

| 100 | 0.0511 | 0.0511 | 0.0222 | 0.05 | 0.0251 | 0.0455 | 0.0459 | |

| 200 | 0.0505 | 0.0529 | 0.0315 | 0.053 | 0.033 | 0.0507 | 0.0505 | |

| 300 | 0.0478 | 0.0493 | 0.0312 | 0.0491 | 0.0321 | 0.0455 | 0.0464 | |

| 0 0 | 20 | 0.0776 | 0.0676 | 0.0707 | 0.1493 | 0.0596 | 0.0596 | 0.0595 |

| 40 | 0.0831 | 0.0828 | 0.031 | 0.1205 | 0.0231 | 0.0579 | 0.0602 | |

| 60 | 0.0777 | 0.0785 | 0.0444 | 0.1163 | 0.0274 | 0.0553 | 0.0578 | |

| 80 | 0.0891 | 0.0865 | 0.0552 | 0.118 | 0.0342 | 0.0537 | 0.0559 | |

| 100 | 0.0813 | 0.0815 | 0.067 | 0.1247 | 0.0382 | 0.0578 | 0.0579 | |

| 200 | 0.0861 | 0.0852 | 0.0927 | 0.1373 | 0.0389 | 0.0559 | 0.0547 | |

| 300 | 0.0921 | 0.0906 | 0.0976 | 0.1358 | 0.0411 | 0.055 | 0.0537 | |

| 0.3 0.3 | 20 | 0.1085 | 0.1197 | 0.1132 | 0.2148 | 0.0306 | 0.0606 | 0.0591 |

| 40 | 0.1278 | 0.1268 | 0.0743 | 0.216 | 0.0214 | 0.0607 | 0.0603 | |

| 60 | 0.1341 | 0.1328 | 0.1065 | 0.2202 | 0.0238 | 0.0589 | 0.0587 | |

| 80 | 0.1317 | 0.1297 | 0.1281 | 0.2224 | 0.0234 | 0.0523 | 0.0518 | |

| 100 | 0.1411 | 0.1384 | 0.1527 | 0.252 | 0.0304 | 0.0622 | 0.0603 | |

| 200 | 0.1408 | 0.134 | 0.195 | 0.2729 | 0.0327 | 0.057 | 0.0569 | |

| 300 | 0.1361 | 0.1295 | 0.201 | 0.266 | 0.0324 | 0.0536 | 0.0532 | |

| 0.3 0.5 | 20 | 0.1507 | 0.1343 | 0.1566 | 0.2464 | 0.0266 | 0.0566 | 0.0663 |

| 40 | 0.1548 | 0.1527 | 0.0967 | 0.2596 | 0.0171 | 0.0646 | 0.0638 | |

| 60 | 0.1606 | 0.1576 | 0.1392 | 0.2647 | 0.0209 | 0.0631 | 0.0609 | |

| 80 | 0.1561 | 0.1546 | 0.1695 | 0.2763 | 0.0244 | 0.0656 | 0.0638 | |

| 100 | 0.1629 | 0.1593 | 0.1856 | 0.3022 | 0.025 | 0.065 | 0.0635 | |

| 200 | 0.164 | 0.1582 | 0.2303 | 0.3248 | 0.0279 | 0.0613 | 0.0608 | |

| 300 | 0.1637 | 0.1588 | 0.2526 | 0.335 | 0.0284 | 0.059 | 0.0586 | |

| 0.5 0.5 | 20 | 0.1715 | 0.1758 | 0.0325 | 0.2468 | 0.009 | 0.0754 | 0.0566 |

| 40 | 0.1935 | 0.1896 | 0.1361 | 0.3048 | 0.013 | 0.0663 | 0.0601 | |

| 60 | 0.1881 | 0.1858 | 0.1859 | 0.3189 | 0.0154 | 0.061 | 0.0593 | |

| 80 | 0.2024 | 0.1974 | 0.2224 | 0.3437 | 0.0176 | 0.0602 | 0.0602 | |

| 100 | 0.206 | 0.2016 | 0.2483 | 0.3793 | 0.022 | 0.0644 | 0.0637 | |

| 200 | 0.1953 | 0.1923 | 0.3071 | 0.4076 | 0.0234 | 0.0562 | 0.0557 | |

| 300 | 0.1955 | 0.1888 | 0.3396 | 0.4323 | 0.0279 | 0.0588 | 0.0585 | |

| 0.5 0.8 | 20 | 0.2024 | 0.1805 | 0.1951 | 0.2904 | 0.059 | 0.059 | 0.0616 |

| 40 | 0.2469 | 0.2502 | 0.1841 | 0.3557 | 0.0069 | 0.0723 | 0.0664 | |

| 60 | 0.2445 | 0.2415 | 0.2462 | 0.3797 | 0.0103 | 0.068 | 0.0663 | |

| 80 | 0.2535 | 0.2508 | 0.2882 | 0.3976 | 0.0099 | 0.065 | 0.0627 | |

| 100 | 0.2584 | 0.2543 | 0.3155 | 0.4872 | 0.0115 | 0.0665 | 0.0661 | |

| 200 | 0.2636 | 0.2606 | 0.3985 | 0.5459 | 0.0166 | 0.0609 | 0.0595 | |

| 300 | 0.2516 | 0.2831 | 0.199 | 0.5748 | 0.0127 | 0.0627 | 0.0638 |

References

- Andrews, D. W. K. (1991). Heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation consistent covariance matrix estimation. Econometrica, 59(3), 817-858. [CrossRef]

- Amato, J. D., & Laubach, T. (1999). Monetary policy in an estimated optimization-based model with sticky prices and wages. Research Working Paper (No. RWP 99-09). Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

- Carlstein, E. (1986). The use of subseries values for estimating the variance of a general statistic from a stationary sequence. The Annals of Statistics, 14(3), 1171-1179. [CrossRef]

- Cryer, J. D., & Chan, K. S. (2011). Time series analysis and its applications: With R examples (2nd ed.) (Pan, H. Y., Trans.). China Machine Press.

- Dang, A., Moh’d, A., Islam, A., et al. (2016). Reddit temporal n-gram corpus and its applications on paraphrase and semantic similarity in social media using a topic-based latent semantic analysis. In Proceedings of the 26th International Conference on Computational Linguistics (COLING 2016) (pp. 3553-3564). Association for Computational Linguistics.

- Hall, P. (1985). Resampling a coverage pattern. Stochastic Processes and Their Applications, 20(2), 231-246. [CrossRef]

- Li, Y., Ni, P., & Chang, V. (2019). An empirical research on the investment strategy of stock market based on deep reinforcement learning model. In F. Firouzi, E. Estrada, V. M. Muñoz, & V. Chang (Eds.), Complexis 2019 - Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Complexity, Future Information Systems and Risk (pp. 52-58). SciTePress.

- Mudelsee, M. I. (2010). Climate time series analysis: Classical statistical and bootstrap methods. Atmospheric and Oceanographic Sciences Library. Springer.

- Peligrad, M., & Utev, S. (2005). A new maximal inequality and invariance principle for stationary sequences. The Annals of Probability, 33(2), 798-815. [CrossRef]

- Sherman, M. F. M. S., Jr., & Speed, F. M. (1998). Analysis of tidal data via the blockwise bootstrap. Journal of Applied Statistics, 25(3), 333-340. [CrossRef]

- Storey, J. D. (2002). A direct approach to false discovery rates. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B, 64(3), 479-498. [CrossRef]

- Storey, J. D. (2003). The positive false discovery rate: A bayesian interpretation and the q-value. The Annals of Statistics, 31(6), 2013-2035. [CrossRef]

- Xia, L. C., Ai, D., Cram, J. A., Fuhrman, J. A., & Sun, F. (2013). Efficient statistical significance approximation for local similarity analysis of high-throughput time series data. Bioinformatics, 29(2), 230-237. [CrossRef]

- Xia, L. C., Ai, D., Cram, J. A., Liang, X., Fuhrman, J. A., & Sun, F. (2015). Statistical significance approximation in local trend analysis of high-throughput time series data using the theory of Markov chains. BMC Bioinformatics, 16, 301. [CrossRef]

- Zou, L. Q. (2020). Markov chain model and its application. Science and Technology Innovation Herald, 2020(11),97-98. [CrossRef]

| n | PCC | Spearman | TLSA | Permutation | DDLSA | MBBLSA | CMBBLSA | |

| -0.5 -0.5 | 20 | 0.1063 | 0.1099 | 0.0407 | 0.1243 | 0.0198 | 0.0538 | 0.0499 |

| 40 | 0.1193 | 0.1136 | 0.0755 | 0.1408 | 0.0357 | 0.0575 | 0.0577 | |

| 60 | 0.1208 | 0.1156 | 0.0951 | 0.1502 | 0.0391 | 0.057 | 0.056 | |

| 80 | 0.1215 | 0.1198 | 0.104 | 0.157 | 0.039 | 0.0563 | 0.0539 | |

| 100 | 0.1245 | 0.1206 | 0.1182 | 0.1642 | 0.0432 | 0.0592 | 0.0547 | |

| 200 | 0.1275 | 0.1203 | 0.1376 | 0.1754 | 0.0461 | 0.0563 | 0.0548 | |

| 300 | 0.1328 | 0.1261 | 0.1527 | 0.1798 | 0.0497 | 0.0597 | 0.058 | |

| 0 0 | 20 | 0.0488 | 0.0469 | 0.0108 | 0.0496 | 0.0169 | 0.046 | 0.045 |

| 40 | 0.0531 | 0.0503 | 0.0225 | 0.0513 | 0.0264 | 0.0497 | 0.0502 | |

| 60 | 0.0489 | 0.0469 | 0.0242 | 0.0504 | 0.0287 | 0.0475 | 0.0486 | |

| 80 | 0.0464 | 0.0471 | 0.0264 | 0.0473 | 0.0279 | 0.0462 | 0.0463 | |

| 100 | 0.0499 | 0.049 | 0.0291 | 0.0513 | 0.0324 | 0.0491 | 0.05 | |

| 200 | 0.05 | 0.051 | 0.0346 | 0.0493 | 0.0363 | 0.0486 | 0.0496 | |

| 300 | 0.0477 | 0.0481 | 0.0373 | 0.0486 | 0.0383 | 0.0491 | 0.0496 | |

| 0.3 0.3 | 20 | 0.0645 | 0.0638 | 0.0161 | 0.0639 | 0.0227 | 0.0544 | 0.0532 |

| 40 | 0.0667 | 0.0659 | 0.0288 | 0.07 | 0.0286 | 0.0545 | 0.0534 | |

| 60 | 0.0697 | 0.0701 | 0.0395 | 0.0771 | 0.034 | 0.0575 | 0.057 | |

| 80 | 0.0742 | 0.0704 | 0.0473 | 0.0748 | 0.0417 | 0.0591 | 0.0565 | |

| 100 | 0.0716 | 0.0691 | 0.0486 | 0.0764 | 0.0401 | 0.0555 | 0.0544 | |

| 200 | 0.0722 | 0.0719 | 0.0618 | 0.0831 | 0.0476 | 0.0578 | 0.0563 | |

| 300 | 0.067 | 0.0704 | 0.061 | 0.0799 | 0.0445 | 0.0519 | 0.0502 | |

| 0.3 0.5 | 20 | 0.0795 | 0.0802 | 0.0198 | 0.077 | 0.022 | 0.0606 | 0.0587 |

| 40 | 0.0825 | 0.0837 | 0.0419 | 0.0888 | 0.0341 | 0.0613 | 0.0599 | |

| 60 | 0.0859 | 0.0848 | 0.0535 | 0.0931 | 0.0402 | 0.062 | 0.0583 | |

| 80 | 0.0878 | 0.0884 | 0.0622 | 0.1019 | 0.0417 | 0.0609 | 0.06 | |

| 100 | 0.0885 | 0.0873 | 0.07 | 0.1058 | 0.0457 | 0.0646 | 0.0621 | |

| 200 | 0.093 | 0.0888 | 0.0834 | 0.1098 | 0.0472 | 0.0605 | 0.0586 | |

| 300 | 0.0902 | 0.0859 | 0.0888 | 0.1115 | 0.0496 | 0.059 | 0.0575 | |

| 0.5 0.5 | 20 | 0.1046 | 0.1036 | 0.034 | 0.1079 | 0.0324 | 0.0724 | 0.0703 |

| 40 | 0.1157 | 0.1133 | 0.0668 | 0.1245 | 0.04 | 0.065 | 0.0646 | |

| 60 | 0.1175 | 0.1159 | 0.0851 | 0.1396 | 0.0413 | 0.0627 | 0.0626 | |

| 80 | 0.1223 | 0.1182 | 0.1009 | 0.1535 | 0.0467 | 0.0648 | 0.0644 | |

| 100 | 0.1151 | 0.1116 | 0.1033 | 0.1465 | 0.045 | 0.0622 | 0.0602 | |

| 200 | 0.1234 | 0.1192 | 0.1332 | 0.1675 | 0.0473 | 0.0602 | 0.0588 | |

| 300 | 0.1256 | 0.1192 | 0.142 | 0.1696 | 0.0531 | 0.0613 | 0.0601 | |

| 0.5 0.8 | 20 | 0.1484 | 0.1503 | 0.0559 | 0.1514 | 0.0359 | 0.0864 | 0.0847 |

| 40 | 0.1703 | 0.1731 | 0.1163 | 0.1985 | 0.045 | 0.0793 | 0.0712 | |

| 60 | 0.1859 | 0.1848 | 0.1529 | 0.224 | 0.0448 | 0.0763 | 0.0727 | |

| 80 | 0.1869 | 0.1814 | 0.1748 | 0.2388 | 0.0449 | 0.0742 | 0.0732 | |

| 100 | 0.1875 | 0.1837 | 0.1942 | 0.2584 | 0.0431 | 0.073 | 0.0712 | |

| 200 | 0.1939 | 0.1881 | 0.2442 | 0.2902 | 0.0511 | 0.0717 | 0.0703 | |

| 300 | 0.1927 | 0.1859 | 0.2687 | 0.3088 | 0.0464 | 0.0654 | 0.0628 |

| n | PCC | Spearman | TLSA | Permutation | DDLSA | MBBLSA | CMBBLSA | |

| -0.5 -0.5 | 20 | 0.0482 | 0.0493 | 0.01 | 0.0475 | 0.0167 | 0.0455 | 0.0458 |

| 40 | 0.0472 | 0.0473 | 0.0202 | 0.0496 | 0.0226 | 0.0475 | 0.0478 | |

| 60 | 0.0516 | 0.0513 | 0.0251 | 0.0512 | 0.0293 | 0.0493 | 0.0502 | |

| 80 | 0.0489 | 0.0486 | 0.0268 | 0.0502 | 0.0301 | 0.0493 | 0.0498 | |

| 100 | 0.0504 | 0.05 | 0.0291 | 0.0484 | 0.0324 | 0.0479 | 0.0489 | |

| 200 | 0.0497 | 0.0523 | 0.0346 | 0.0512 | 0.0364 | 0.0516 | 0.0498 | |

| 300 | 0.0489 | 0.0503 | 0.0383 | 0.05 | 0.0391 | 0.0499 | 0.0502 | |

| 0 0 | 20 | 0.0858 | 0.0825 | 0.0237 | 0.0903 | 0.026 | 0.0658 | 0.0651 |

| 40 | 0.0823 | 0.0786 | 0.0396 | 0.0876 | 0.032 | 0.0576 | 0.0568 | |

| 60 | 0.0845 | 0.0799 | 0.0534 | 0.0899 | 0.0388 | 0.0567 | 0.0562 | |

| 80 | 0.085 | 0.0808 | 0.0602 | 0.0967 | 0.0439 | 0.059 | 0.0565 | |

| 100 | 0.0895 | 0.0841 | 0.0669 | 0.0997 | 0.0437 | 0.0596 | 0.0581 | |

| 200 | 0.0851 | 0.082 | 0.0749 | 0.1018 | 0.0453 | 0.0553 | 0.0547 | |

| 300 | 0.0857 | 0.0828 | 0.0841 | 0.105 | 0.046 | 0.0545 | 0.0533 | |

| 0.3 0.3 | 20 | 0.1274 | 0.1272 | 0.046 | 0.1361 | 0.0316 | 0.0745 | 0.0727 |

| 40 | 0.1316 | 0.1284 | 0.0866 | 0.1572 | 0.0383 | 0.0677 | 0.0675 | |

| 60 | 0.1357 | 0.1335 | 0.1066 | 0.1692 | 0.0373 | 0.0605 | 0.0605 | |

| 80 | 0.1455 | 0.1416 | 0.1267 | 0.1815 | 0.0427 | 0.067 | 0.065 | |

| 100 | 0.1391 | 0.1309 | 0.1348 | 0.1834 | 0.0397 | 0.0605 | 0.0586 | |

| 200 | 0.1398 | 0.1367 | 0.1558 | 0.1953 | 0.0444 | 0.0597 | 0.0595 | |

| 300 | 0.1433 | 0.1408 | 0.1786 | 0.212 | 0.0459 | 0.059 | 0.0588 | |

| 0.3 0.5 | 20 | 0.1454 | 0.1457 | 0.057 | 0.1543 | 0.0307 | 0.0756 | 0.0703 |

| 40 | 0.158 | 0.1534 | 0.1052 | 0.1851 | 0.0367 | 0.0678 | 0.0674 | |

| 60 | 0.1359 | 0.1523 | 0.133 | 0.1979 | 0.036 | 0.0636 | 0.0625 | |

| 80 | 0.1576 | 0.1561 | 0.1526 | 0.2086 | 0.0392 | 0.0657 | 0.0643 | |

| 100 | 0.166 | 0.1601 | 0.1665 | 0.2233 | 0.0423 | 0.0648 | 0.0628 | |

| 200 | 0.165 | 0.1561 | 0.1956 | 0.239 | 0.0406 | 0.0587 | 0.0573 | |

| 300 | 0.1637 | 0.1541 | 0.2178 | 0.2514 | 0.0427 | 0.0593 | 0.0569 | |

| 0.5 0.5 | 20 | 0.1786 | 0.1811 | 0.0802 | 0.1919 | 0.0364 | 0.0943 | 0.0812 |

| 40 | 0.1852 | 0.1848 | 0.1376 | 0.2222 | 0.0323 | 0.0693 | 0.0651 | |

| 60 | 0.1849 | 0.1841 | 0.1716 | 0.2511 | 0.0323 | 0.062 | 0.0598 | |

| 80 | 0.193 | 0.1856 | 0.1967 | 0.2708 | 0.0373 | 0.0602 | 0.0577 | |

| 100 | 0.1921 | 0.1869 | 0.2139 | 0.2808 | 0.0368 | 0.0598 | 0.0581 | |

| 200 | 0.1957 | 0.1901 | 0.2559 | 0.307 | 0.042 | 0.0567 | 0.0564 | |

| 300 | 0.1972 | 0.1918 | 0.2664 | 0.4115 | 0.0627 | 0.0627 | 0.0637 | |

| 0.5 0.8 | 20 | 0.225 | 0.2295 | 0.1102 | 0.2461 | 0.0282 | 0.1012 | 0.0868 |

| 40 | 0.2442 | 0.2437 | 0.1976 | 0.303 | 0.0295 | 0.0779 | 0.0736 | |

| 60 | 0.2514 | 0.2419 | 0.2443 | 0.3446 | 0.0278 | 0.0658 | 0.0654 | |

| 80 | 0.252 | 0.2543 | 0.2787 | 0.3634 | 0.0337 | 0.0698 | 0.07 | |

| 100 | 0.2544 | 0.2501 | 0.3063 | 0.3877 | 0.0316 | 0.0612 | 0.0606 | |

| 200 | 0.2647 | 0.2601 | 0.3826 | 0.4396 | 0.0402 | 0.0634 | 0.0622 | |

| 300 | 0.2668 | 0.2564 | 0.4186 | 0.464 | 0.0392 | 0.06 | 0.0571 |

| Information Category | Concrete Content |

| Data Source | Intelligent Transportation System (ITS) of a first-tier city, monitoring station coordinates: 39°54′N, 116°23′E (downtown main road) |

| Collection Period | January 2023 – December 2023 (365 days total) |

| Sampling Interval | 5 minutes/interval, 8760 time points in total (continuous time series) |

| Core Variable Types | Traffic Flow Data, Speed Data, Environmental Factors |

| Final Selected Variables | 20 variables (12 traffic flow/speed variables + 8 environment-related variables) |

| Missing Value Handling Method | Piecewise Linear Interpolation |

| Variable Type | Number of Variables |

Number of Significantly Autocorrelated Variables |

Proportion | Typical Variable Autocorrelation Coefficient (Lag 1) |

| Traffic Flow Data | 6 | 5 | 83.3% | Main Road A Morning Peak Flow: 0.68 (p=2.1×10−6) |

| Speed Data | 6 | 5 | 83.3% | Main Road B Evening Peak Speed: 0.52 (p=3.7×10−5) |

| Environmental Factors | 8 | 6 | 75.0% | Rainfall: 0.45 (p=1.2×10−4) |

| Total | 20 | 16 | 80.0% | -- |

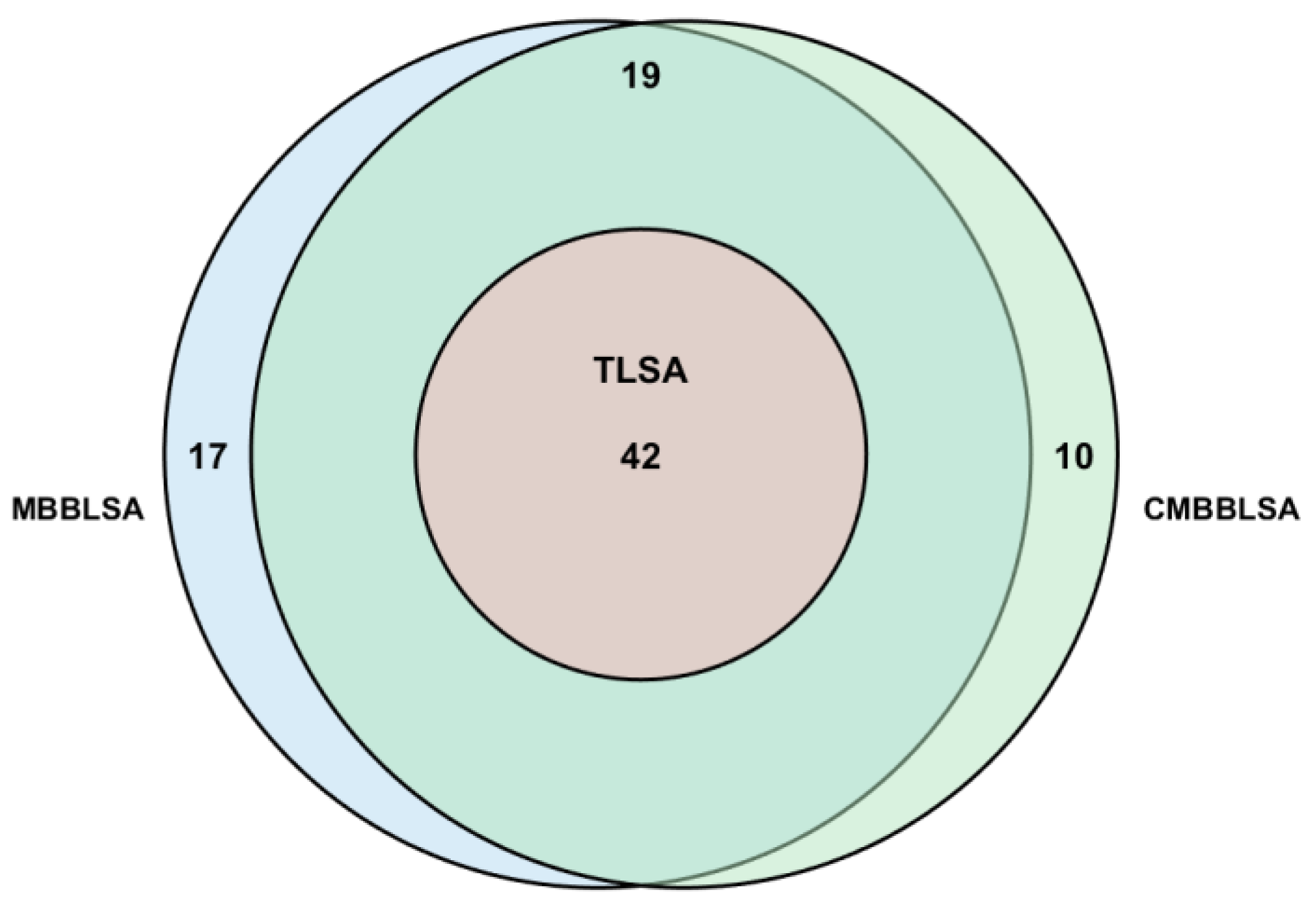

| Significance Level | TLSA | MBBLSA | CMBBLSA | False Positive Reduction Rate of CMBBLSA Compared to MBBLSA |

| =0.05 | 42 | 78 | 61 | 21.8% |

| =0.01 | 23 | 45 | 32 | 28.9% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).