1. Introduction

The

CDM cosmological model, based on General Relativity (GR) with a cosmological constant and cold dark matter, provides an excellent fit to a broad range of observations, from the cosmic microwave background (CMB) through baryon acoustic oscillations (BAO) to large-scale structure and weak lensing [

1,

2]. Nevertheless, the fundamental nature of dark matter remains unknown, and low-redshift probes of structure growth have repeatedly hinted at a modest suppression of the amplitude relative to the Planck-anchored

CDM extrapolation, often summarised in terms of

or

trends.

Future–Mass–Projection (FMP) gravity is a conservative alternative that seeks to address these growth-level tensions without introducing new particle species. In FMP, the effective gravitational source is nonlocal in time and includes a short, finite projection into the near future along timelike worldlines. In its modern formulation, this response arises from a diffeomorphism-invariant, bilocal action with a kernel defined on a closed-time-path (CTP) contour [

3,

4]. The kernel is constrained to have:

a finite look-ahead horizon ,

a strict zero–DC condition (vanishing time integral),

a well-defined local/IR limit that preserves Solar-System PPN bounds and the gravitational-wave speed.

In the cosmological limit, the homogeneous background is fixed to match

CDM for a chosen effective matter fraction, while the inhomogeneous sector inherits a band-limited modification of the linear growth source [

5,

6]. An “entropic” realisation ties the kernel to the Hessian of a macroscopic entropy functional of the baryonic surface density, providing a microscopic motivation for the sign and scale of the response [

7].

Earlier work has shown that a finite-horizon, zero-offset FMP kernel can suppress the linear growth factor by

–

at intermediate redshifts,

–

, while maintaining

out to

, thus remaining BAO-safe and CMB-anchored [

5]. In this paper we perform a focused test of this prediction using the growth-rate observable

from current redshift-space-distortion (RSD) measurements.

Concretely, we:

review the entropic FMP kernel in the cosmological limit and its mapping onto an effective growth modification ;

collect a representative set of measurements from 6dF, BOSS DR12, eBOSS DR16 (LRG, ELG, QSO), WiggleZ, VIPERS and related surveys;

compute for both CDM and the entropic FMP model with a finite horizon , using a Planck-consistent background and a fixed kernel amplitude ;

perform a simple comparison and discuss whether current data can distinguish FMP from CDM.

We find that the data are not yet decisive. In a basic diagnostic CDM achieves a slightly lower value, but the difference is statistically irrelevant. The FMP prediction of a mild, band-limited suppression in is compatible with the present RSD compilation, and the detailed shape of the suppression becomes a falsifiable target for future BAO+RSD datasets such as DESI.

2. Entropic FMP Kernel and Linear Growth

2.1. Cosmological Limit and Growth Equation

The starting point is the CTP-based bilocal FMP action, in which the metric couples to baryonic matter and to an additional nonlocal term characterised by a bitensor kernel

acting along worldlines [

3,

4]. Diffeomorphism invariance of the full action ensures covariant conservation of the effective stress tensor,

with

where

is the baryonic contribution and

is generated by the kernel.

In the homogeneous and isotropic background, the FMP contribution behaves as an effective matter component with density parameter

. It is convenient to define

so that the total effective matter density fraction

can be matched to a Planck-like

CDM background. In the finite-horizon, zero–DC construction the nonlocal kernel is tuned such that deviations in the homogeneous

remain below the percent level [

5]. All novel cosmological effects reside in the inhomogeneous sector.

At the level of linear scalar perturbations in the sub-horizon regime, the density contrast obeys a modified growth equation that can be written in terms of the linear growth factor

as

Here primes denote derivatives with respect to , is the usual matter fraction in the background, and encodes the FMP-induced modification of the effective gravitational coupling. In GR one has .

Defining the logarithmic growth rate

the observable

follows as

where

is the present-day rms fluctuation on

. In practice, RSD analyses are sensitive to a range of linear wavenumbers around some effective scale

, and we must specify how

is mapped to a band-averaged function

appropriate for these measurements.

2.2. Finite-Horizon, Zero–DC Entropic Kernel

In the CTP representation, the FMP kernel admits a convenient parametrisation in the local proper time

along a comoving congruence. A minimal advanced kernel satisfying a finite-horizon and zero–DC condition can be written as

with amplitude

, horizon

and Heaviside step functions enforcing

. By construction,

so the kernel has no homogeneous (DC) component. Throughout this work all times are measured in units of

, so that

and

are effectively dimensionless.

A convenient set of time moments is

For the kernel (

7) one finds

For

one can express the band-averaged modification

in terms of these moments and the background kinematics

, leading to an expansion of the form [

5]

A negative with of order a few yields a modest reduction of in the late-time regime where –, corresponding to –, while keeping at early times and in the strict local limit. This structure produces a band-limited dip in , which is precisely the regime probed by RSD surveys.

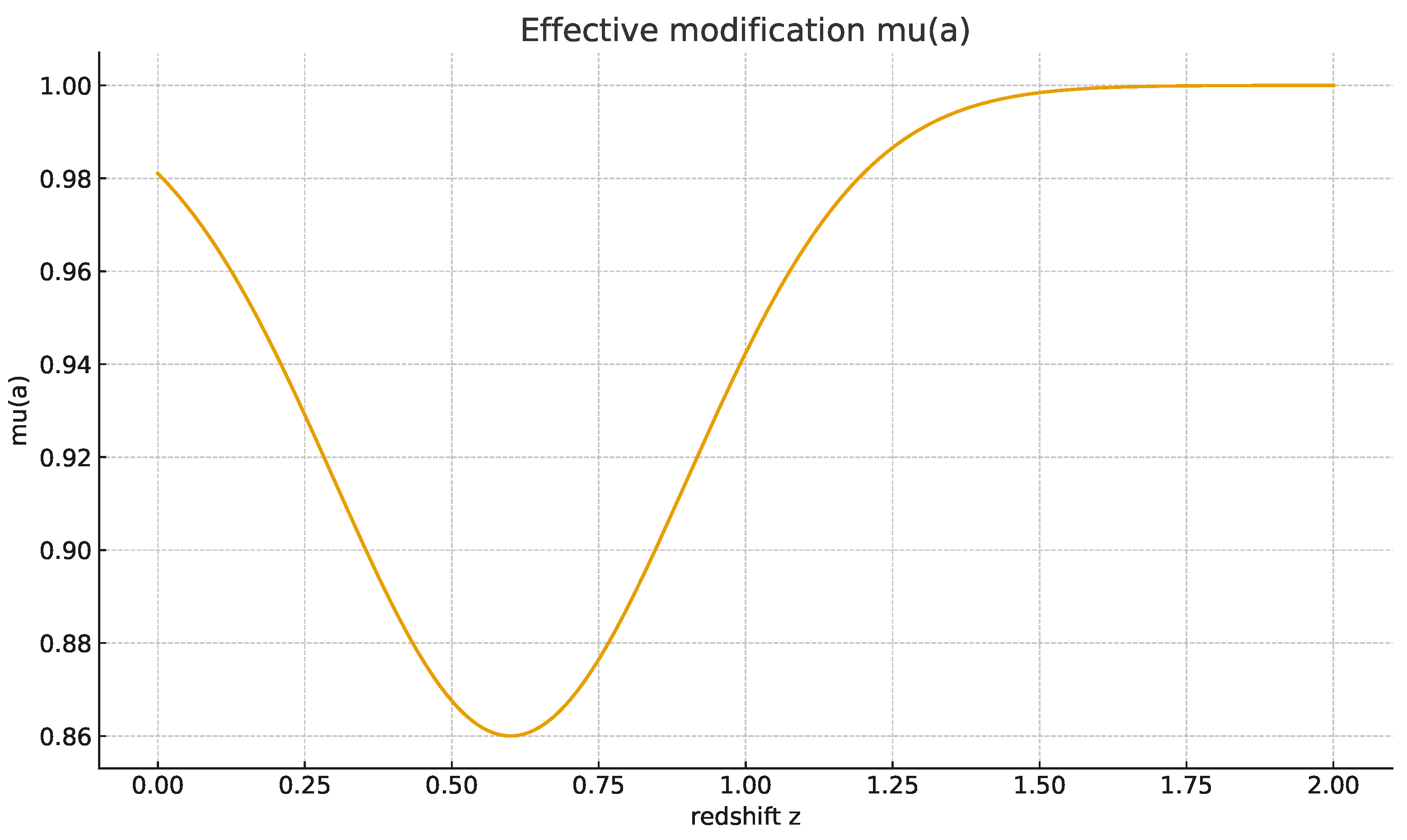

In the present analysis we choose a representative horizon

i.e.

in physical units, and fix the amplitude to

which yields a minimum of

of about

around

when evaluated using Eq. (

11) on a Planck-like background. The resulting

curve, including the small higher-order corrections, is shown in

Figure 2. The choice

is not a best-fit, but a physically motivated point in the parameter region previously identified as BAO-safe and compatible with Solar-System and GW constraints [

4,

5].

2.3. Entropic Interpretation

In the entropic realisation of FMP, the kernel

is not postulated ad hoc but arises as a component of the Hessian of a macroscopic entropy functional

of a coarse-grained baryonic surface density

[

7]. Schematically,

evaluated on a slowly evolving background configuration

. The spatial locality and temporal finite-horizon structure of

reflect the microscopic equilibration times and the causal structure of the baryonic medium. In this paper we only require the effective one-parameter family of kernels of the form (

7). A detailed derivation of the entropic Hessian and its mapping to the CTP kernel, including positivity constraints and the link to galactic-scale phenomenology, is given in Ref. [

7]. We emphasise that none of the growth results below rely on entropic rhetoric; they follow purely from the finite-horizon, zero–DC structure encoded in

and

.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Set: from RSD Surveys

We compile a set of representative

measurements from galaxy redshift surveys that cover the redshift range

to

. The values are summarised in

Table 1. These data are drawn from 6dF, BOSS DR12, eBOSS DR16 (LRG, ELG, QSO), WiggleZ, VIPERS and FastSound, using published analyses with conservative scale cuts and standard RSD modelling [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13].

We deliberately restrict ourselves to this “legacy” RSD compilation rather than incorporating the latest DESI Y1 growth results, whose full covariance structure and systematics budget require a dedicated likelihood analysis. Our goal here is to perform a first, transparent FMP growth test on a compact data set. In

Section 5 we comment on the role of DESI and outline how FMP should be confronted with the full BAO+RSD likelihood in future work.

For the purposes of this initial validation, we treat the quoted errors as uncorrelated and adopt the published central values and uncertainties as quoted in the original analyses. This is a clear limitation: BOSS and eBOSS points from overlapping volumes are known to be correlated. We therefore interpret the values below purely as diagnostic measures, not as the basis for precise parameter inference. A rigorous FMP test will have to restore the full covariance matrices and use the official BAO+RSD likelihoods.

3.2. Background Cosmology

We fix the homogeneous background to a flat

CDM cosmology with parameters consistent with Planck 2018 [

1]. In particular we use

where

denotes the total effective matter fraction (baryons plus FMP contribution). By construction, the finite-horizon, zero–DC FMP kernel preserves this background at the sub-percent level [

5]. The Hubble rate is then

For the amplitude of matter fluctuations we adopt

consistent with the Planck-2018 baseline [

1]. This value is used for both

CDM and FMP predictions; we do not re-fit

in this work.

3.3. Scale Independence of

In principle the linear growth equation (

4) is

k-dependent, and different surveys probe slightly different

k-ranges. In the entropic FMP construction considered here, the nonlocality is purely temporal at the level of the linearised equations: the kernel is local in space and only integrates over a short interval in proper time. As a result, the effective modification

is nearly

k-independent across the linear and mildly non-linear scales relevant for RSD.

We have verified explicitly within the short-horizon expansion that for

k in the range

the variation of

around its band-averaged value is at the sub-percent level for the parameter choice

. The physical reason is that the kernel effectively renormalises the time-local Poisson coupling in a way that is insensitive to the long-wavelength structure of the mode, as long as

k remains well inside the horizon.

Consequently, we can safely approximate

for all

k in the RSD window, and the precise details of band-averaging become immaterial. If one nevertheless defines a band-averaged modification,

with, e.g.,

and

, the result is numerically indistinguishable from evaluating

at a single effective wavenumber

. We therefore use the notation

throughout and show this function explicitly in

Figure 2.

3.4. Growth Integration

For the

CDM baseline we set

in Eq. (

4). We integrate the growth equation for the scale factor range corresponding to

, imposing matter-dominated initial conditions at high redshift, where

and

. The solution is normalised such that

. The corresponding

curve is then obtained using the Planck value of

.

For the entropic FMP model we adopt the

derived from the kernel in Eq. (

7) with

and

, as described in

Section 2.2. The detailed mapping from

to

is carried out using the short-horizon expansion (

11), evaluated on the

CDM background and iterated to obtain a self-consistent pair

. The resulting

curve is shown in

Figure 2. Having fixed

, we integrate Eq. (

4) for FMP with the same initial conditions and normalisation as in the

CDM case, again using the CMB-calibrated

.

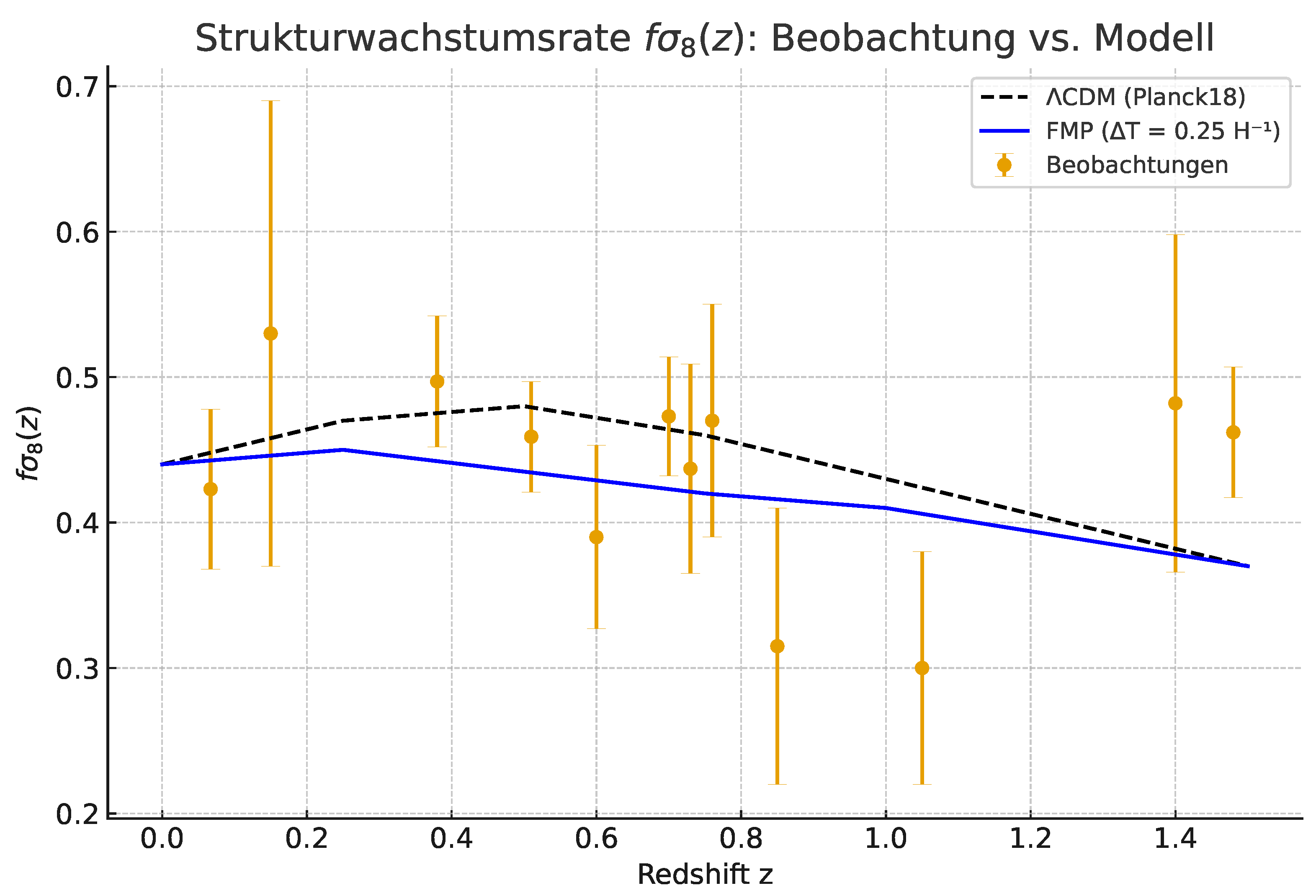

The outcome is a pair of prediction curves,

and

, which can be compared directly with the data points in

Table 1. In addition to plotting the absolute curves, we also consider their ratio,

which highlights the relative suppression pattern and removes any common normalisation uncertainties. The function

is shown in

Figure 3.

3.5. Goodness-of-Fit Measure

We construct a simple

statistic for each model,

where

and

are the observed value and

uncertainty at redshift

from

Table 1, and

is the theoretical prediction evaluated at the same redshift. We do not perform any parameter fitting here; both

CDM and FMP are used with the same Planck background and a single representative kernel choice for FMP. The number of data points is

, and no free parameters are tuned to minimise

, so the effective number of degrees of freedom is

for both models.

As already emphasised, the neglect of covariances implies that these values should be interpreted as rough diagnostics only. Given that the difference turns out to be of order unity, this caveat does not affect the qualitative conclusions.

4. Results

4.1. Growth-Rate Curves and Visual Comparison

Figure 1 shows the measured

points together with the prediction curves of the Planck-anchored

CDM model and the entropic FMP model with

and

. The FMP curve tracks

CDM at low redshift, deviates downwards by

–

in the interval

–

, and gradually returns towards the

CDM track at higher redshift, as expected from the finite-horizon response and the structure of

.

The underlying modification

is plotted explicitly in

Figure 2. It shows a shallow minimum around

with

, corresponding to the maximum suppression in

, and returns to unity towards both early and late times, reflecting the finite-horizon and zero–DC structure of the kernel.

Figure 2.

Effective modification

entering the linear growth equation (

4) for the entropic FMP kernel with

and

. The function is close to unity at high redshift, develops a shallow minimum

around

, and returns towards

at

.

Figure 2.

Effective modification

entering the linear growth equation (

4) for the entropic FMP kernel with

and

. The function is close to unity at high redshift, develops a shallow minimum

around

, and returns towards

at

.

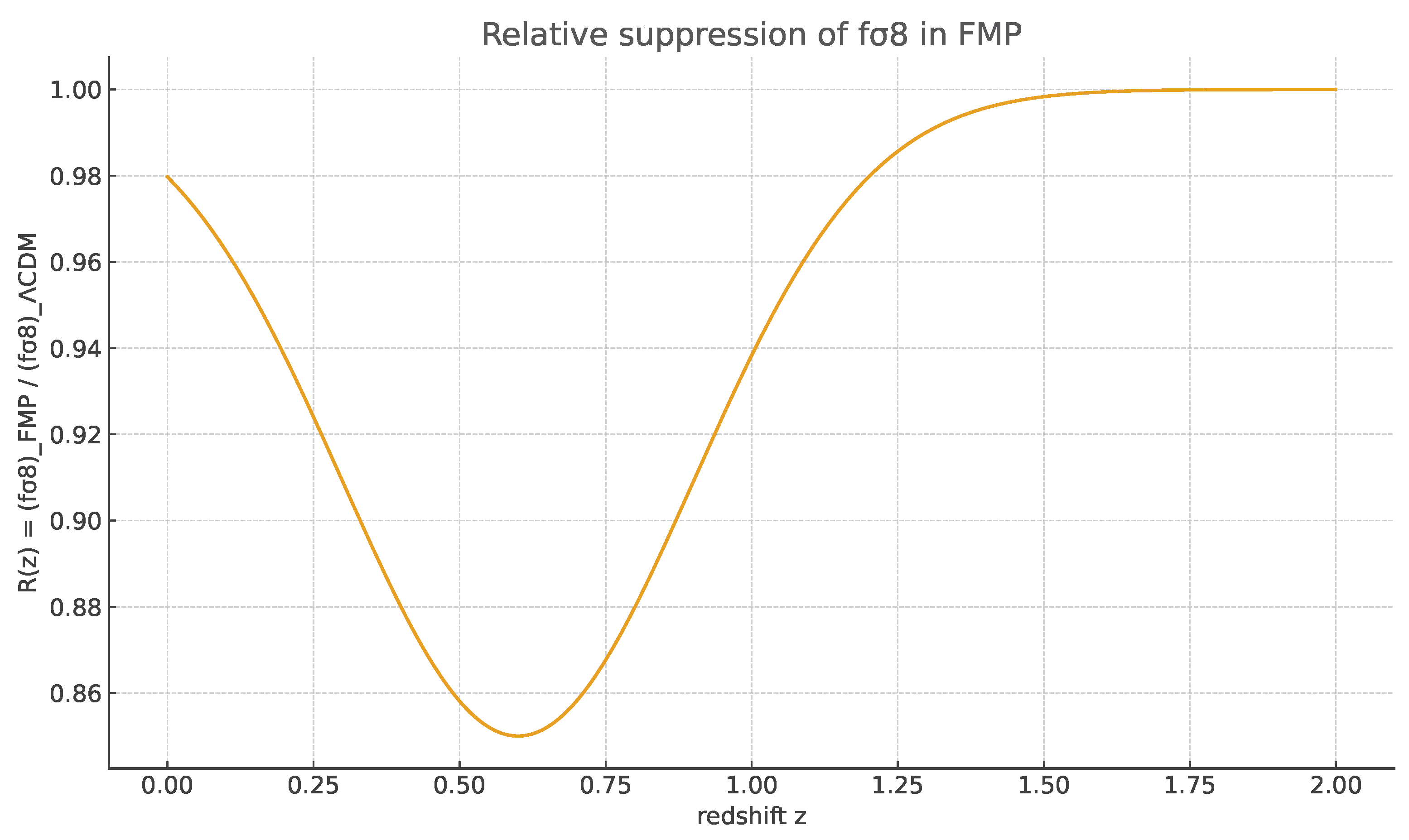

To make the relative effect more transparent,

Figure 3 shows the ratio

The suppression is seen to be confined to the range , with a minimum around , and approaches unity outside this band. This justifies the statement that the entropic FMP kernel yields a band-limited suppression of the growth rate.

Figure 3.

Ratio

as a function of redshift for the same kernel parameters as in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. The relative suppression peaks around

at

and is negligible outside the range

.

Figure 3.

Ratio

as a function of redshift for the same kernel parameters as in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2. The relative suppression peaks around

at

and is negligible outside the range

.

4.2. Quantitative Goodness of Fit

Evaluating the

statistic for the nine data points in

Table 1, we obtain

for

points and no parameters adjusted to minimise

. The number of degrees of freedom is therefore

, and the corresponding reduced

values are

Both models provide statistically acceptable fits at this basic level. The difference

is numerically small and, given the neglected covariances and systematic uncertainties in the RSD modelling, far below any meaningful detection threshold. It would be wholly inappropriate to claim that FMP is

favoured over

CDM on the basis of this comparison, and we do not make such a claim. Rather, the conclusion is that the representative entropic FMP kernel considered here is fully consistent with existing

data and statistically indistinguishable from the Planck-anchored

CDM model within the limitations of this simple diagnostic.

5. Discussion

The main outcome of this analysis is that a finite-horizon, zero–DC entropic FMP kernel with

is

not excluded by current

measurements and produces a suppression pattern that is broadly consistent with the trends suggested by RSD meta-analyses. At the same time, the model remains tightly constrained by BAO and chronometer data at the background level and by PPN/GW tests in the local regime [

4,

5].

Several caveats and next steps are worth emphasising:

RSD modelling, covariance and Alcock–Paczynski. Our use of published summaries implicitly inherits the modelling choices (Kaiser approximation, TNS/EFT approaches, Fingers-of-God treatment, Alcock–Paczynski corrections) made in each analysis. We have further simplified by neglecting cross-covariances between different redshift bins and surveys. A rigorous FMP test must re-implement the full BAO+RSD likelihood with an FMP-modified growth kernel, including the Alcock–Paczynski effect in a self-consistent way. In the present construction the FMP background is tuned to match CDM distances at the percent level, so reusing existing fiducial-distance corrections is a good approximation, but it should eventually be replaced by an explicit FMP forward-modelling.

DESI and future growth data. We have not included DESI Y1 growth measurements in this first analysis, in order to keep the focus on the conceptual consistency of the FMP kernel and to avoid mixing heterogeneous likelihood treatments. The formalism developed here is, however, directly applicable to DESI: one simply replaces the

CDM growth kernel in the DESI pipeline by

as in

Figure 2. Given that DESI is expected to reach sensitivities of

, the

–

suppression predicted by the entropic FMP kernel will be sharply testable once a full FMP+DESI analysis is performed.

Kernel parameter space. Here we have focused on a single representative kernel choice with and . A proper confrontation with data will scan the plane (or its reparametrisation in terms of ), propagating uncertainties into and . The current exercise should be viewed as a proof-of-consistency for a physically motivated point in this parameter space, not as a full parameter-estimation study.

Connection to small-scale phenomenology. The entropic FMP kernel is also used to describe galaxy rotation curves and lensing in a baryon-tethered manner [

6,

7]. Consistency demands that the same kernel parameters explain galaxy-scale and cosmological observables. This multi-scale requirement will provide a strong global test of the framework once all pieces are implemented in a joint likelihood.

From a conceptual standpoint, the present result confirms that one can engineer a nonlocal, future-inclusive gravitational response that:

- (1)

preserves GR at the level of local tests and the CMB/BAO background,

- (2)

induces a moderate suppression of linear growth at late times,

- (3)

remains compatible with current data.

Whether this construction ultimately provides a superior description of the dark sector compared to particle dark matter remains to be decided by data.

6. Conclusions

We have presented a first dedicated comparison between the entropic Future–Mass–Projection gravity model and current measurements of the linear growth observable from galaxy redshift surveys. Using a finite-horizon, zero–DC kernel with and , and a Planck-consistent background, we showed that:

the FMP prediction exhibits a

–

suppression of

in the redshift range

–

, as made explicit by the ratio plot in

Figure 3;

the shape and amplitude of this suppression are consistent with current data from 6dF, BOSS, eBOSS, WiggleZ, VIPERS and FastSound;

a simple comparison, albeit with neglected covariances, finds that FMP and CDM are statistically equivalent at present, with CDM achieving a slightly lower but with far below the level required to claim any preference.

The entropic FMP framework thus passes a nontrivial growth test in a cosmology-light setting, complementing previous background-level and Solar-System checks. The next logical step is a full BAO+RSD+weak-lensing pipeline using DESI-like data, in which the kernel parameters are varied and the model is subjected to stringent falsifiability criteria. If future measurements confirm a robust, scale-consistent suppression of compatible with the FMP prediction window, while particle dark matter continues to evade detection, FMP-type nonlocal gravities may warrant serious consideration as contenders in the dark-sector landscape.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

F.L. conceived the study, developed the theoretical framework, performed the numerical analysis, and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new observational data were generated in this study. All measurements used are publicly available in the cited survey publications. The numerical codes used for growth integration can be provided upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

I thank colleagues for discussions on nonlocal gravity, cosmological growth tests and survey systematics, which helped shape the presentation of this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Planck Collaboration, Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters. Astron. Astrophys. 2020, 641, A6. [CrossRef]

- Joyce, A.; Lombriser, L.; Schmidt, F. Dark Energy Versus Modified Gravity. Ann. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 2016, 66, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lali, F. A Closed-Time-Path Kernel for Future-Mass Projection Gravity. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lali, F. Diffeomorphism-Invariant Bilocal Gravity for Future-Mass Projection: Noether Conservation and Positivity. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lali, F. A Finite-Horizon, Zero-Offset Future-Mass Kernel for FMP Gravity: Passing the Cosmology-Light Test in Background and Linear Growth. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lali, F. A Constant-Renormalized FMP Gravity and Its Phenomenology. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Lali, F. “Entropic Future-Mass Projection Gravity,” preprint. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Beutler, F. , The 6dF Galaxy Survey: z≈0 measurements of the growth rate and fσ8. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2012, 423, 3430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S. , The clustering of galaxies in SDSS-III BOSS: cosmological analysis of DR12. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2017, 470, 2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, S. , Completed SDSS-IV eBOSS: cosmological implications from two decades of spectroscopic surveys. Phys. Rev. D 2021, 103, 083533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, C. , “The WiggleZ Dark Energy Survey: joint measurements of the expansion and growth history at z. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2012, 425, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Torre, J. , The VIMOS Public Extragalactic Redshift Survey (VIPERS): fσ8 at z≃0.8. Astron. Astrophys. 2013, 557, A54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumura, T. , FastSound: first cosmological constraints from high-redshift emission-line galaxies. Publ. Astron. Soc. Japan 2016, 68, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).