1. Introduction

Obesity is a rapidly escalating global health crisis that is characterized by generalized metabolic and inflammatory disturbances [

1]. Despite the extensive characterization of systemic complications, the impact of obesity on salivary gland homeostasis remains poorly understood [

2,

3]. Newer evidence indicates that obesity is associated with reduced salivary secretion, altered glandular composition, and an increased susceptibility to oral dysfunction. Leptin-deficient

ob/ob mice, which develop profound hyperphagia and severe obesity, serve as robust models for elucidating the pathological mechanisms underlying obesity-induced salivary gland dysfunction [

4,

5,

6].

Among the diverse forms of regulated cell death, ferroptosis has recently attracted attention as a key driver of tissue injury in metabolic and inflammatory diseases [

7]. Ferroptosis, which is characterized by iron-dependent accumulation of lipid peroxides that frequently occurs with the depletion or inactivation of glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4), causes overwhelming oxidative damage to polyunsaturated fatty acid-containing membranes. Morphologically distinct from apoptosis or necrosis, ferroptosis is characterized by unique mitochondrial ultrastructural changes, including cristae collapse, outer membrane rupture, and increased matrix density [

8,

9,

10].

Salivary glands are highly metabolic organs that are particularly vulnerable to oxidative stress [

11]. Under various pathological conditions, ferroptosis plays a central role in salivary gland dysfunction. In a study that used ovariectomized rat models, treatment with ferrostatin-1 effectively preserved the glandular architecture and suppressed lipid peroxidation [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Subsequent studies extended these findings to radiation-induced salivary gland injury, wherein compounds such as amifostine and melatonin exert protective effects by inhibiting ferroptotic processes [

16]. The evaluation of ferroptosis in hepatic tissues revealed a critical role for ferritinophagy, particularly NCOA4-mediated pathways, in promoting steatotic liver injury [

17].

Despite these advances, the specific contribution of ferroptosis in obesity-driven salivary gland pathology remains largely unknown. Although both ferrostatin-1 (a lipid radical scavenger) and deferoxamine (an iron chelator) are established modulators of ferroptotic pathways, their comparative efficacy in mitigating obesity-associated salivary gland injury remains unelucidated.

This study investigated the involvement of ferroptosis in salivary gland dysfunction in obesity and evaluated the therapeutic potential of ferrostatin-1- and deferoxamine-induced pathway inhibition in a mouse model. Utilizing comprehensive histological, biochemical, and ultrastructural analyses, we aimed to elucidate the mechanistic underpinnings of ferroptosis in obese salivary glands and assess the comparative efficacy of the abovementioned two pharmacological inhibitors in restoring glandular homeostasis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Models and Experimental Design

Leptin-deficient (ob/ob) mice, characterized by excessive food intake and pronounced obesity, are widely used as robust models of metabolic disorders. In this study, we used ob/ob mice to investigate the contribution of ferroptosis to obesity-induced alterations in the salivary glands. Six-week-old female C57BL/6-Jms Slc mice (n = 8) and age-matched C57BL/6J ob/ob mice (n = 24) were obtained from Japan SLC (Shizuoka, Japan). Following a 2-week acclimation period, the animals were randomly assigned to four groups (n = 8 per group) as follows: wild-type C57BL/6 (control), untreated ob/ob, ferrostatin-1-treated ob/ob (FER), and deferoxamine-treated ob/ob (DFO). All animals were fed standard chow ad libitum throughout the study period. Beginning at 8 weeks of age, mice in the FER and DFO groups received intraperitoneal (IP) injections of ferrostatin-1 (5 µM/kg) or deferoxamine (100 mg/kg), respectively, three times weekly for 8 weeks. The control and untreated ob/ob groups received vehicle (sterile saline) injections according to the same schedule. To monitor pathological progression, baseline and endpoint assessments were conducted at 8 and 16 weeks of age. At the study endpoint, the animals were anesthetized via inhalation and blood samples were collected from the inferior vena cava. Subsequently, the mice were euthanized and salivary gland tissues were harvested for subsequent analysis. All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Pusan National University Hospital (IACUC approval no. PNUH-2023-223).

2.2. Measurement of Lipid Peroxidation

The level of malondialdehyde (MDA), a biomarker of lipid peroxidation, was quantified using a commercial detection kit (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Tissue homogenates and standards were incubated with thiobarbituric acid (TBA) at 95°C for 1 h. Following rapid cooling on ice, the absorbance of the MDA-TBA adduct was spectrophotometrically measured at 532 nm. The MDA concentrations were determined by interpolating a standard curve.

2.3. Cytosolic Iron Quantification

Intracellular ferrous iron (Fe2+) levels were assessed using a colorimetric assay kit (Abcam, ab83366). Approximately 30 mg of salivary gland tissue was homogenized in Iron Assay Buffer and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was reacted with an iron probe under acidic conditions to produce a colored complex, which was detected spectrophotometrically at 593 nm. Data were normalized to the total protein content that was determined using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay.

2.4. Detection of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

ROS generation was measured using the fluorescent probe 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA). Homogenized tissue samples were incubated with 10 µM DCFH-DA at 37°C for 30 min in the dark. Oxidation of the probe yielded fluorescent dichlorofluorescein (DCF), which was measured fluorometrically (e.g., using a fluorescence microplate reader) at excitation/emission wavelengths of 485/535 nm. The fluorescence intensity was normalized to the protein concentration.

2.5. GPX4 Activity Assay

Glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) activity was evaluated using a commercial assay kit (Abcam). Enzymatic activity was quantified by measuring the rate of NADPH oxidation. Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA method, and activity was calculated according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.6. Histological and Immunohistochemical Analysis

Salivary glands were excised immediately after euthanasia, fixed overnight in 4% formalin, and paraffin-embedded. Because mouse salivary glands are very small, multiple specimens from animals within the same experimental group were embedded together and stained on the same slide to ensure uniform staining conditions and to allow direct comparison across samples. Serial paraffin sections were prepared so that histologic and immunohistochemical analyses could be performed at anatomically comparable levels among animals.

Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for general morphology or Masson’s trichrome (MT) for fibrosis assessment. For immunohistochemistry (IHC), deparaffinized sections underwent antigen retrieval and were incubated with primary antibodies at 4 °C for 24 h. After washing, the sections were incubated with horseradish peroxidase–conjugated secondary antibodies (ENZO Biochem Inc., USA) for 1 h at room temperature (23 °C), followed by visualization using DAB and counterstaining with hematoxylin. Negative controls were processed in parallel by substituting PBS containing 1% BSA for the primary antibody.

Representative images were acquired from the central region of each gland using a Leica light microscope at 200× magnification. For each animal, 3–4 serial sections were evaluated, and 5–7 microscopic fields per section were analyzed in a fully blinded manner to ensure methodological rigor.

2.7. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM)

For ultrastructural analysis, salivary gland tissues were pre-fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde in phosphate buffer and post-fixed in 1% osmium tetroxide. After dehydration through a graded ethanol series, samples were embedded in Epon 812 resin. Ultrathin sections (50–60 nm) were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined using a JEOL JEM-1200EXII transmission electron microscope.

To ensure adequate quantitative assessment of mitochondrial morphology, three animals per group were examined. For each animal, 2–3 ultrathin sections were prepared, and 8–10 TEM fields per section were analyzed. Mitochondrial integrity was assessed in a blinded manner, focusing on cristae structure, membrane continuity, and the degree of swelling.

2.8. Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted using the TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis was synthesized using a reverse transcription kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Quantitative real-time PCR (qPCR) was conducted on an ABI PRISM 7900 HT system using SYBR Green Chemistry. The relative gene expression levels were calculated using the 2

−ΔΔCt method, with

GAPDH normalized as the endogenous reference gene. The primer sequences are listed in

Table 1.

2.9. Western Blotting

Tissue lysates were prepared in a radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer that was supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors. Lysates were cleared by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. Proteins were separated using sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. These membranes were blocked (e.g., with 5% non-fat milk) and incubated overnight at 4°C with the following primary antibodies: LC3B, p62, PRKN, PINK1, NCOA4 (all at 1:1000 dilution), and β-actin. HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5000) were applied for 2 h at room temperature. Signals were detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) reagent and visualized using an imaging system.

2.10. Statistical Analysis

All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Intergroup comparisons were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Scheffé's post-hoc test using SPSS (v19.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). A p-value <0.05 was considered as the cutoff for statistical significance.

3. Results

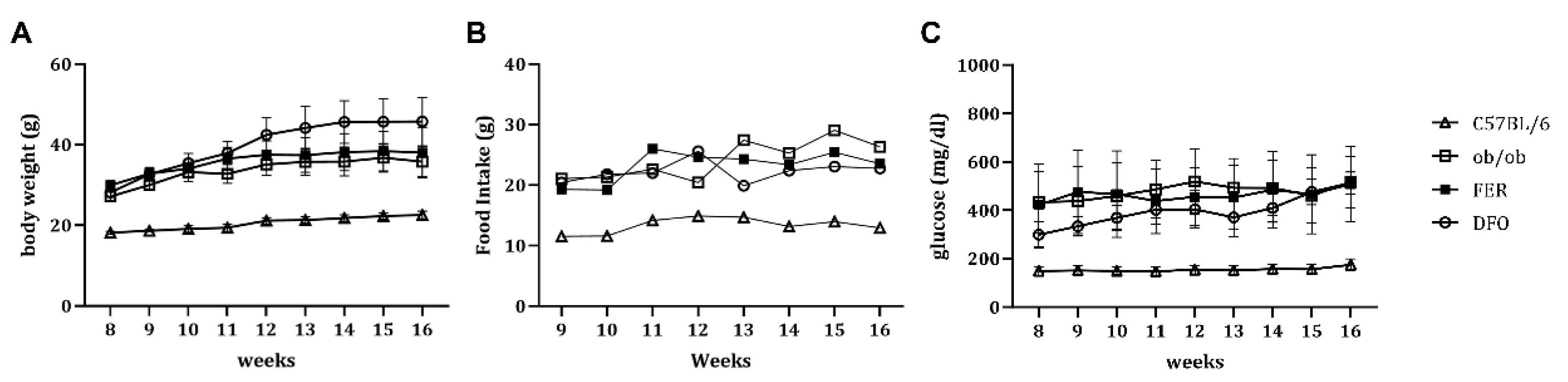

3.1. Obesity-Associated Changes in Weight, Nutrient Intake, and Glycemic Status

Body weight was consistently elevated in all obese groups, including untreated

ob/ob mice, compared to that in C57BL/6 control mice (

Figure 1A). Moreover, the daily food intake significantly increased across these groups, and reflected the characteristic leptin deficiency-associated hyperphagic behavior (

Figure 1B). In parallel, fasting glucose levels were markedly elevated in the untreated

ob/ob group, and remained similarly high in the FER and DFO groups throughout the experimental period (

Figure 1C). These systemic metabolic alterations established a physiologically unfavorable environment that potentially fosters subsequent histological and functional deterioration of the salivary glands.

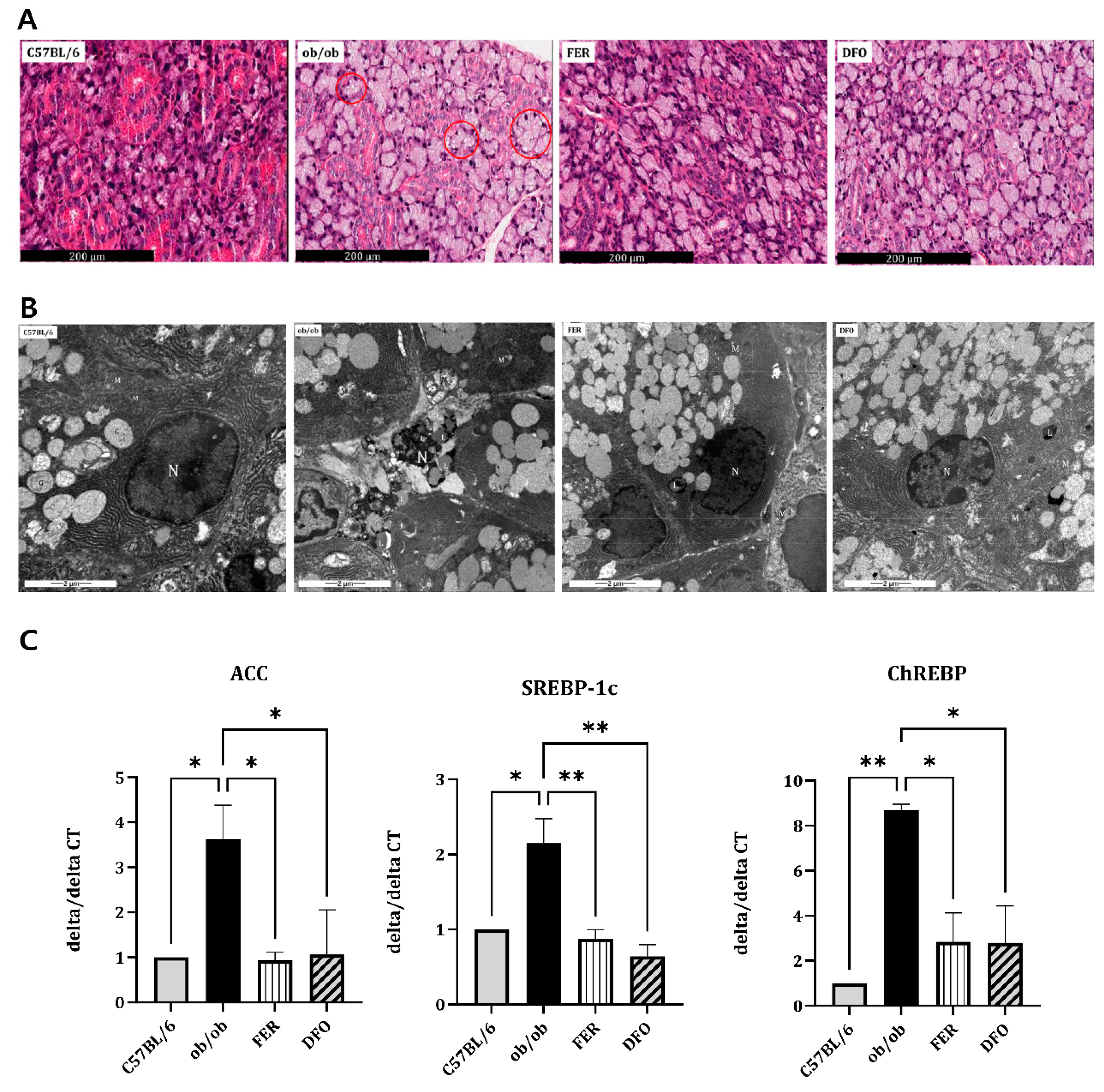

3.2. Enhanced Lipogenesis in the Salivary Glands of Obese Mice

Histological analysis revealed pronounced acinar atrophy, expanded interstitial spaces, and extensive cytoplasmic vacuolization that was consistent with lipid-droplet accumulation in the salivary glands of untreated

ob/ob mice (

Figure 2A). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) further confirmed the presence of abundant cytoplasmic lipid droplets within acinar cells. Notably, this accumulation was markedly reduced in both DFO- and FER-treated groups (

Figure 2B). At the transcriptional level,

ob/ob mice exhibited significantly elevated expression of key lipogenesis-related genes, including

acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC),

sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c), and

carbohydrate-responsive element-binding protein (ChREBP). Treatment with either ferrostatin-1 or deferoxamine substantially suppressed the expression of these lipogenic genes (

Figure 2C). Collectively, these findings demonstrate that obesity promotes profound lipid accumulation in the salivary glands, as evident at the histological, ultrastructural, and molecular levels, which can be effectively mitigated by ferroptosis-targeted interventions.

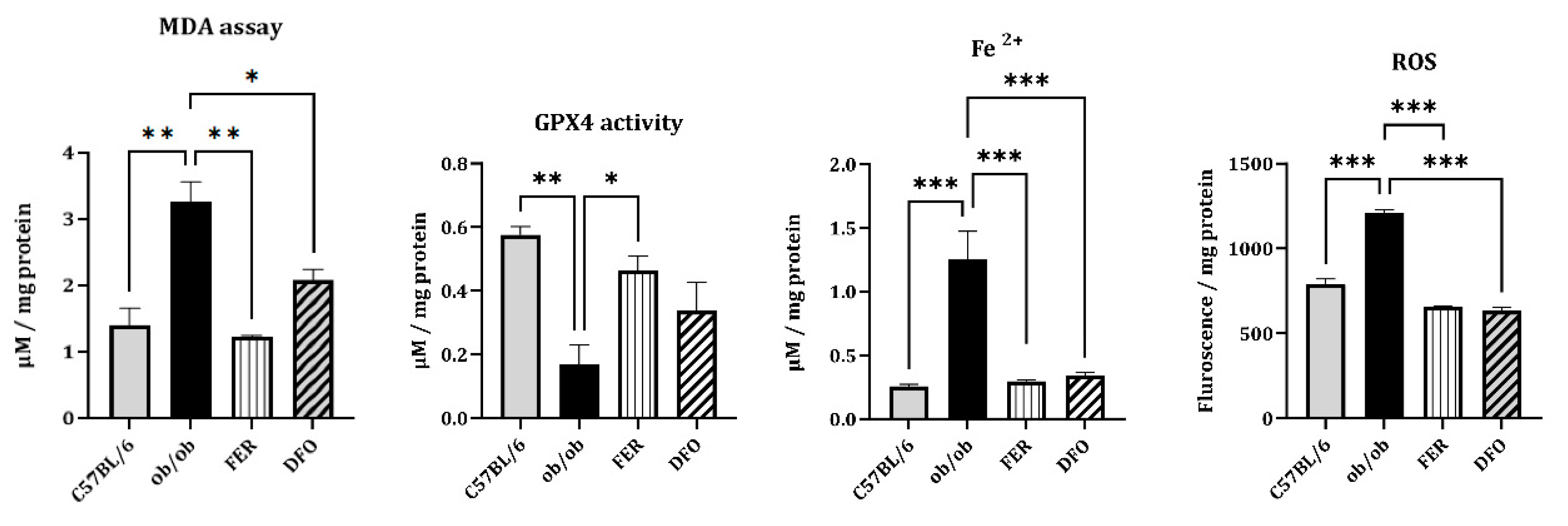

3.3. Ferroptosis-associated Oxidative Stress and Iron Dysregulation

To investigate whether obesity-induced salivary gland injury involves ferroptosis, we measured the key indices of oxidative damage and iron accumulation. ROS levels were significantly elevated in the ob/ob group, as determined by DCFH-DA fluorescence assay, and were effectively reduced by either ferrostatin-1 or deferoxamine (p < 0.001). Moreover, the MDA content—a marker of lipid peroxidation—increased in the ob/ob group. Ferrostatin-1 treatment induced a greater reduction in MDA levels than did the deferoxamine treatment (p < 0.01 and p < 0.05, respectively). Similarly, the primary ferroptosis defense mechanism, indicated by GPX4 enzymatic activity, was markedly impaired in ob/ob mice. This activity was more robustly restored by ferrostatin-1 than by deferoxamine (p < 0.05). In contrast, cytosolic Fe2+ levels, which were significantly elevated in the ob/ob group, were comparably reduced by either treatment (p < 0.001). These results confirmed that obesity promotes ferroptosis-associated oxidative stress and iron overload in salivary glands. Furthermore, they suggest that, compared with deferoxamine, ferrostatin-1 exerts superior efficacy in mitigating lipid peroxidation and restoring antioxidant capacity in this model.

Figure 3.

Oxidative stress and iron accumulation associated with ferroptosis in the salivary glands of C57BL/6, ob/ob, FER, and DFO groups. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, which were measured using a DCFH-DA fluorescence assay, were significantly elevated in the ob/ob group and decreased following treatment with either ferrostatin-1 or deferoxamine. Malondialdehyde (MDA) levels increased in the ob/ob mice and markedly decreased by ferrostatin-1, rather than by deferoxamine, treatment. GPX4 enzymatic activity was reduced in the ob/ob group and more effectively restored in the FER group compared to the DFO group. Cytosolic ferrous iron (Fe2+) levels were elevated in the ob/ob mice and normalized in both treatment groups. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Columns and error bars represent mean ± standard deviation. FER, ferrostatin-1-treated ob/ob mice; DFO, deferoxamine-treated ob/ob mice; GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4.

Figure 3.

Oxidative stress and iron accumulation associated with ferroptosis in the salivary glands of C57BL/6, ob/ob, FER, and DFO groups. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) levels, which were measured using a DCFH-DA fluorescence assay, were significantly elevated in the ob/ob group and decreased following treatment with either ferrostatin-1 or deferoxamine. Malondialdehyde (MDA) levels increased in the ob/ob mice and markedly decreased by ferrostatin-1, rather than by deferoxamine, treatment. GPX4 enzymatic activity was reduced in the ob/ob group and more effectively restored in the FER group compared to the DFO group. Cytosolic ferrous iron (Fe2+) levels were elevated in the ob/ob mice and normalized in both treatment groups. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. Columns and error bars represent mean ± standard deviation. FER, ferrostatin-1-treated ob/ob mice; DFO, deferoxamine-treated ob/ob mice; GPX4, glutathione peroxidase 4.

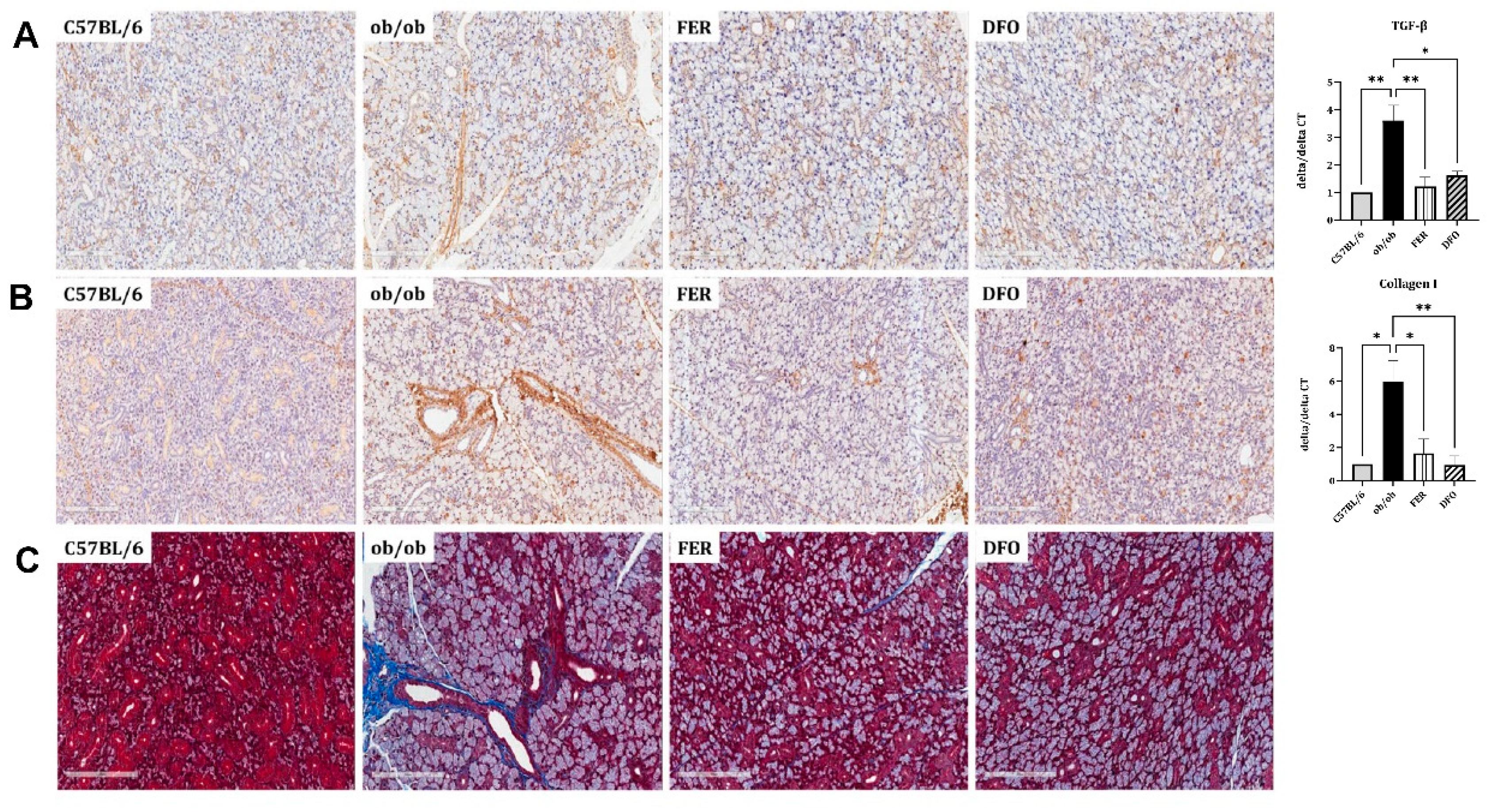

3.4. Obesity-induced Fibrosis and Inflammation in the Salivary Glands

To evaluate whether obesity-induced ferroptosis is accompanied by fibrotic remodeling, we analyzed the histological and transcriptional markers in the salivary glands. In the

ob/ob group, immunohistochemical staining revealed the increased expression of the profibrotic mediators TGF-β and Collagen I, which are indicative of enhanced fibrotic activity. This increase was attenuated in both treatment groups. The qPCR analysis corroborated these histological findings.

TGF-β mRNA was significantly upregulated in the

ob/ob group and was more robustly suppressed by ferrostatin-1 than by deferoxamine (

p < 0.01 and

p < 0.05, respectively). In contrast,

Collagen I mRNA expression showed a stronger suppressive response to deferoxamine (

p < 0.01;

Figure 4A and B). MT staining was used to assess collagen deposition. MT staining revealed extensive interstitial fibrosis (blue staining) in the

ob/ob group, which was markedly reduced following either ferrostatin-1 or deferoxamine treatment (

Figure 4C). These findings indicate that ferroptosis is closely linked to fibrotic remodeling in salivary glands under obese conditions, with ferrostatin-1 and deferoxamine exhibiting differential regulatory effects on specific fibrosis-related pathways.

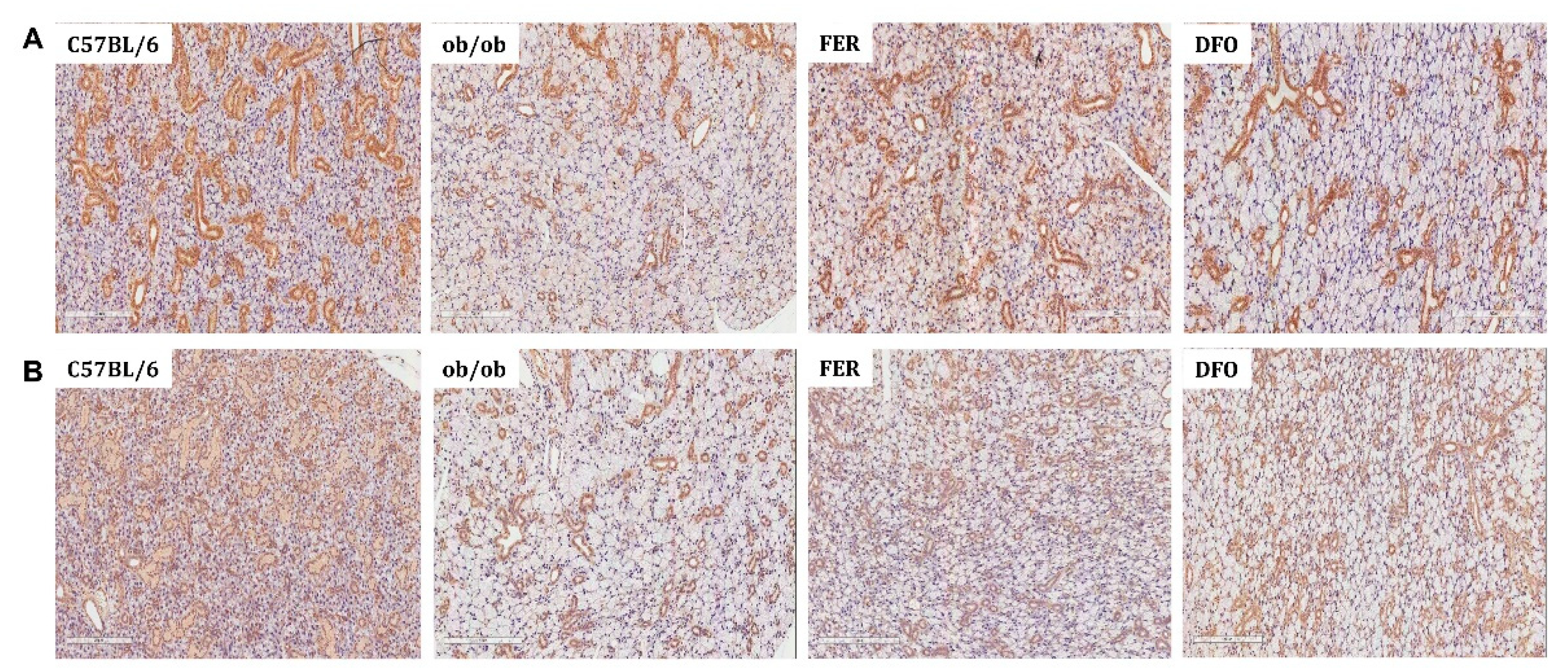

3.5. Functional Deterioration of the Salivary Glands and Its Reversal by Ferroptosis Inhibitors

To assess the secretory function of salivary glands, we performed immunohistochemical staining for functional markers. In the

ob/ob group, the expression of α-amylase—a key digestive enzyme—was markedly reduced compared to that in C57BL/6 controls. This reduction was partially reversed in both treatment groups; however, a more pronounced recovery was observed in the FER group (

Figure 5A). Similarly, the expression of aquaporin-5 (AQP5) —a water-channel protein that is essential for saliva secretion—decreased in the

ob/ob group. Compared to deferoxamine treatment, ferrostatin-1 treatment more effectively restored AQP5 expression (

Figure 5B). These findings suggest that obesity-induced ferroptosis significantly impairs salivary gland secretory function and that pharmacological inhibition of this pathway, particularly with ferrostatin-1, can effectively facilitate functional recovery.

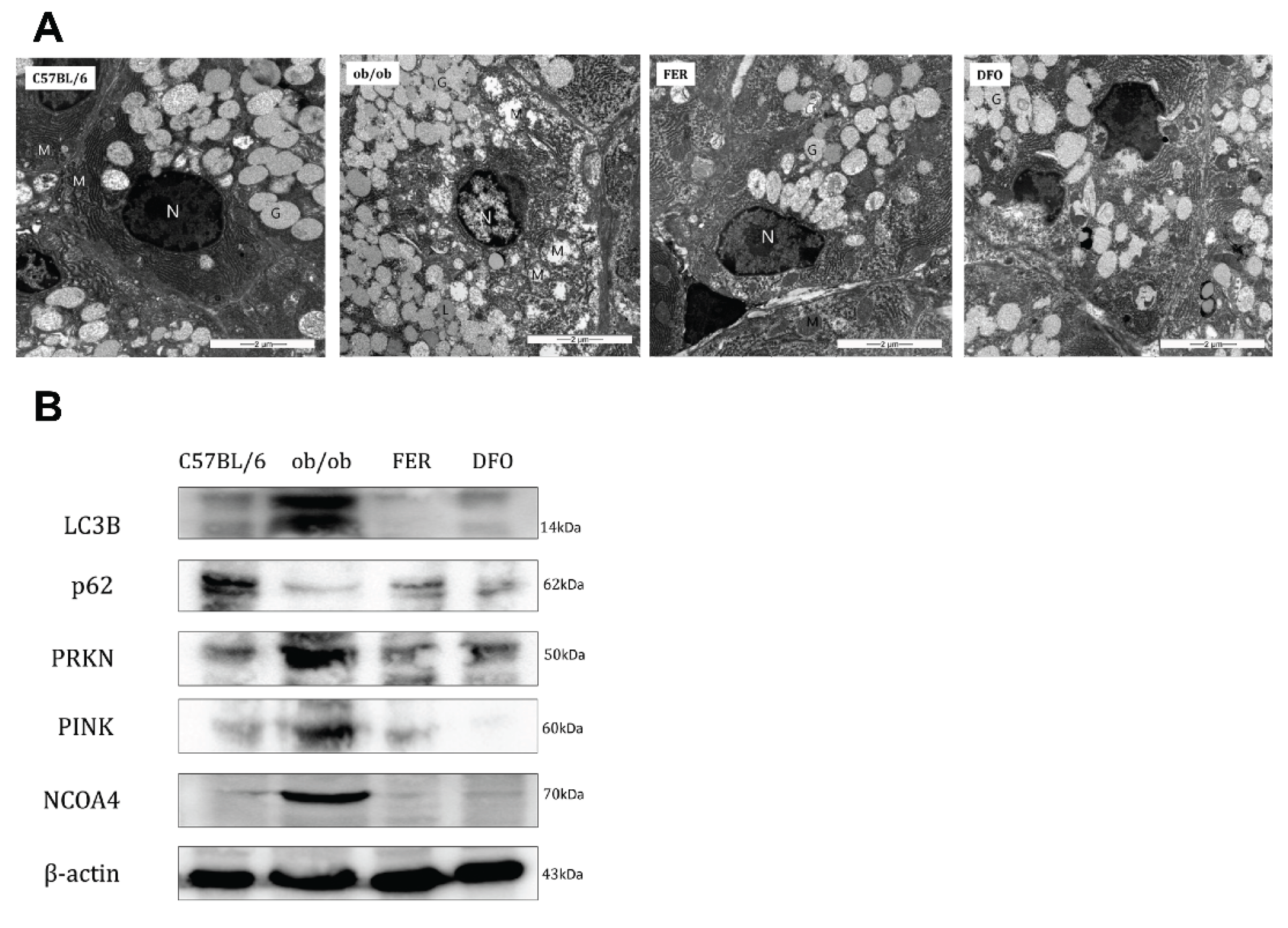

3.6. Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Selective Autophagy Imbalance in the Obese Salivary Glands

Considering the observed phenotypic changes, we examined the mitochondrial ultrastructure and regulation of selective autophagy pathways. In the

ob/ob group, TEM revealed severe mitochondrial ultrastructural damage, which was characterized by swelling, loss of cristae, and outer membrane rupture. These morphological changes were partially mitigated by ferrostatin-1 or deferoxamine treatment (

Figure 6A). Western blotting revealed distinct alterations in key autophagy- and mitophagy-regulatory proteins. The expression of LC3B-II (the lipidated form, indicated at 14 kDa) was most prominently induced in the

ob/ob group. Concurrently, the levels of p62 (SQSTM1)—an autophagy substrate—were markedly decreased in

ob/ob mice compared with controls. This pattern (high LC3B-II and low p62 levels) suggested enhanced autophagic degradation (increased flux) in the obese state. Both treatments reduced LC3B-II levels and partially restored p62 levels, which suggested the normalization of autophagic flux. The mitophagy regulators PINK1 and PRKN (parkin) were upregulated in the

ob/ob group. Either treatment decreased the expression of these proteins. Notably, ferrostatin-1 maintained PINK1 expression at levels that were similar to those in the control whereas deferoxamine resulted in a near-complete loss of the PINK1 signal. NCOA4—a cargo receptor for ferritinophagy—is selectively elevated in

ob/ob mice, which suggests increased ferritin turnover. NCOA4 levels were suppressed in both the control and treatment groups. These findings indicate that obesity-induced salivary gland pathology involves significant mitochondrial damage and the dysregulation of selective autophagy pathways, including mitophagy and ferritinophagy. The modulation of autophagic flux and mitophagy markers by ferroptosis inhibitors, particularly the preservation of PINK1 by ferrostatin-1, likely contributed to the observed tissue-protective effects.

4. Discussion

This study provided compelling evidence that obesity-induced salivary gland dysfunction is associated with ferroptosis. In the ob/ob mouse model, this is evidenced by pronounced lipid peroxidation, iron dysregulation, mitochondrial damage, and impaired secretory function. Through integrated histological, biochemical, ultrastructural, and molecular assessments, we established that ferroptosis plays a pivotal role in salivary gland pathology under metabolic stress. Critically, the pharmacological inhibition of ferroptosis using either ferrostatin-1 or deferoxamine significantly attenuated these pathological changes, which validated ferroptosis as a viable therapeutic target for obesity-associated salivary gland disorders.

Ectopic lipid accumulation has emerged as a prominent feature of salivary gland injury in obese mice that suggests lipotoxicity [

5,

18,

19,

20]. Acinar atrophy, cytoplasmic vacuolization, and TEM-confirmed lipid droplets were accompanied by the transcriptional upregulation of key lipogenic regulators, including

SREBP-1c,

ACC, and

ChREBP. These results are consistent with those of hepatic steatosis models, which suggested that salivary glands undergo a similar maladaptive lipogenic shift in response to chronic metabolic overload [

17]. Both ferroptosis inhibitors effectively suppressed lipogenic gene expression, and this indicates a close relationship between lipid dysregulation and ferroptotic stress. This suggests the presence of a potential feedback loop wherein oxidative stress exacerbates lipid synthesis, which, in turn, fuels further ferroptosis by increasing the availability of substrates for peroxidation.

The cardinal hallmarks of ferroptosis, oxidative stress, and iron accumulation were evident in the salivary glands of the obese mice [

21,

22,

23]. Elevated ROS and MDA levels, reduced GPX4 activity, and increased cytosolic Fe

2+ collectively confirmed the activation of the ferroptotic cascade. Compared with deferoxamine, ferrostatin-1 demonstrated a superior capacity to suppress lipid peroxidation (MDA) and restore GPX4 activity; however, both treatments comparably reduced cytosolic iron levels. These findings suggest that obesity fosters a lipid ROS-driven ferroptotic milieu in salivary glands. Consequently, the direct neutralization of lipid radicals (by ferrostatin-1) appears to confer broader cytoprotection rather than iron chelation monotherapy (by deferoxamine).

Furthermore, obesity induced substantial fibrotic remodeling, as indicated by the increased expression of TGF-β and Collagen I, and confirmed by MT staining. Interestingly, ferrostatin-1 more effectively reduced

TGF-β expression whereas deferoxamine more prominently suppressed

Collagen I transcripts. This divergence suggests that ferroptosis contributes to fibrotic signaling through complex pathways that involve both iron-and lipid peroxide-dependent mechanisms. These further highlights that different ferroptosis inhibitors can differentially modulate the distinct downstream nodes of tissue remodeling [

24,

25,

26,

27].

Functionally, the diminished expression of α-amylase and AQP5 in obese salivary glands reflects a significant impairment in both the production of digestive enzymes and fluid-secretion capacity. The expression of both proteins was restored by ferrostatin-1 or deferoxamine treatment; however, ferrostatin-1 consistently demonstrated superior restorative efficacy. These results align with those of previous studies, which demonstrated that ferroptosis impairs secretory epithelial function in hormone-deficient and radiation-induced salivary gland injury. This study is the first to significantly extend this paradigm to the context of metabolic diseases [

12,

13,

15,

16].

The mitochondrial ultrastructure exhibited classical ferroptosis-associated damage, including swelling, cristae disruption, and outer membrane rupture, which confirmed mitochondrial vulnerability [

8,

28,

29,

30]. Autophagy and mitophagy markers revealed complex patterns of dysregulation. The combination of increased LC3B-II and decreased p62 levels suggests an enhanced autophagic flux (increased degradation) in the obese state. Concurrently, the upregulation of PINK1 and PRKN indicates heightened mitophagy activation, likely in response to mitochondrial damage. Furthermore, the selective elevation of NCOA4 expression implies the induction of ferritinophagy, which contributes to increased intracellular free iron levels. Treatment modulated these markers, albeit with distinct profiles for the two inhibitors. Ferrostatin-1 preserved PINK1 expression at near-control levels, whereas Deferoxamine almost completely abolished this effect. This striking difference suggests divergent effects on the mitochondrial quality control mechanisms and turnover dynamics. Taken together, these findings underscore the intricate intersection between ferroptosis, selective autophagy, and mitochondrial homeostasis in the functional deterioration of salivary glands under obese conditions [

31,

32].

A key strength of this study was the direct comparative analysis of ferrostatin-1 and deferoxamine—two canonical ferroptosis inhibitors with distinct mechanisms of action [

33,

34,

35]. Ferrostatin-1 functions as a lipophilic radical-trapping antioxidant that directly neutralizes lipid peroxyl radicals and thereby inhibits LPO propagation. In contrast, deferoxamine sequesters redox-active Fe

2+ through chelation and indirectly mitigates ferroptotic stress by limiting Fenton chemistry-mediated ROS generation. These mechanistic differences translate into different biological outcomes. Ferrostatin-1 exhibited superior efficacy in reducing MDA, restoring GPX4 activity, preserving mitophagy-related protein expression (e.g., PINK1), and improving functional markers (AQP5 and amylase). In contrast, deferoxamine exerted a stronger suppressive effect on

Collagen I mRNA expression. These findings indicate that a specific point of intervention within the ferroptotic cascade critically dictates the downstream tissue responses, which highlights the necessity for mechanism-specific therapeutic strategies that are tailored to the underlying pathology.

This study had some limitations. First, functional salivary flow measurements, which would have provided direct evidence for secretory restoration, were not performed. Second, the long-term and potential off-target effects of chronic ferroptosis inhibition warrant further investigation. Third, the upstream regulators of ferroptosis susceptibility, such as NRF2, ACSL4, and SLC7A11, have not been examined yet. Investigating these factors may provide deeper mechanistic insights into the metabolic–redox interface that governs salivary gland ferroptosis.

5. Conclusions

This study established ferroptosis as a critical driver of salivary gland dysfunction in a leptin-deficient mouse model of obesity. Pharmacological inhibition using ferrostatin-1 or deferoxamine effectively mitigates oxidative stress, suppresses lipogenic gene expression, attenuates fibrosis, and restores salivary gland function. Although both agents conferred protection, they exhibited distinct molecular profiles and differential efficacies, particularly in the modulation of lipid peroxidation, iron homeostasis, and autophagic pathways. Collectively, these findings highlight the potential of ferroptosis as a promising therapeutic strategy for managing obesity-associated salivary gland disorders.

Author Contributions

G. C. P., H. P., and B-. J.L. designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the results, and wrote the manuscript. S-.Y.B., J.M.K., and S. C. S. performed the experiments and analyses. Y-.I.C. provided technical support and conceptual advice. B-.J.L. supervised the study. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIT) (no. RS-2022-NR070216).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Ethics Committee of Pusan National University Hospital (No. PNUH-2023-223, approved on September 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author (B-.J.L.) upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Haslam, D.W.; James, W.P. Obesity. Lancet 2005, 366, 1197–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Henning, R.J. Obesity and obesity-induced inflammatory disease contribute to atherosclerosis: a review of the pathophysiology and treatment of obesity. Am J Cardiovasc Dis 2021, 11, 504–529. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jin, X.; Qiu, T.; Li, L.; Yu, R.; Chen, X.; Li, C.; Proud, C.G.; Jiang, T. Pathophysiology of obesity and its associated diseases. Acta Pharm Sin B 2023, 13, 2403–2424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Munzberg, H.; Rezai-Zadeh, K.; Keenan, M.; Coulon, D.; Lu, H.; Berthoud, H.R.; Ye, J. Leptin deficient ob/ob mice and diet-induced obese mice responded differently to Roux-en-Y bypass surgery. Int J Obes (Lond) 2015, 39, 798–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalewska, A.; Ziembicka, D.; Zendzian-Piotrowska, M.; Maciejczyk, M. The Impact of High-Fat Diet on Mitochondrial Function, Free Radical Production, and Nitrosative Stress in the Salivary Glands of Wistar Rats. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2019, 2019, 2606120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rojas, J.M.; Bolze, F.; Thorup, I.; Nowak, J.; Dalsgaard, C.M.; Skydsgaard, M.; Berthelsen, L.O.; Keane, K.A.; Soeborg, H.; Sjogren, I.; et al. The Effect of Diet-induced Obesity on Toxicological Parameters in the Polygenic Sprague-Dawley Rat Model. Toxicol Pathol 2018, 46, 777–798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Stockwell, B.R.; Conrad, M. Ferroptosis: mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2021, 22, 266–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon, S.J.; Lemberg, K.M.; Lamprecht, M.R.; Skouta, R.; Zaitsev, E.M.; Gleason, C.E.; Patel, D.N.; Bauer, A.J.; Cantley, A.M.; Yang, W.S.; et al. Ferroptosis: an iron-dependent form of nonapoptotic cell death. Cell 2012, 149, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cao, F.; Yin, H.L.; Huang, Z.J.; Lin, Z.T.; Mao, N.; Sun, B.; Wang, G. Ferroptosis: past, present and future. Cell Death Dis 2020, 11, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockwell, B.R. Ferroptosis turns 10: Emerging mechanisms, physiological functions, and therapeutic applications. Cell 2022, 185, 2401–2421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Z.; Dong, L.; Zheng, Z.; Liu, S.; Gong, S.; Meng, L.; Xin, Y.; Jiang, X. Mechanism, Prevention, and Treatment of Radiation-Induced Salivary Gland Injury Related to Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants (Basel) 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, H.K.; Kim, J.M.; Shin, S.C.; Sung, E.S.; Kim, H.S.; Park, G.C.; Cheon, Y.I.; Lee, J.C.; Lee, B.J. The mechanism of submandibular gland dysfunction after menopause may be associated with the ferroptosis. Aging (Albany NY) 2020, 12, 21376–21390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.M.; Shin, S.C.; Cheon, Y.I.; Kim, H.S.; Park, G.C.; Kim, H.K.; Han, J.; Seol, J.E.; Vasileva, E.A.; Mishchenko, N.P.; et al. Effect of Echinochrome A on Submandibular Gland Dysfunction in Ovariectomized Rats. Mar Drugs 2022, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, Y.I.; Kim, J.M.; Shin, S.C.; Kim, H.S.; Lee, J.C.; Park, G.C.; Sung, E.S.; Lee, M.; Lee, B.J. Effect of deferoxamine and ferrostatin-1 on salivary gland dysfunction in ovariectomized rats. Aging (Albany NY) 2023, 15, 2418–2432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G.C.; Bang, S.Y.; Kim, J.M.; Shin, S.C.; Cheon, Y.I.; Park, H.; Suh, S.; Cho, J.H.; Sung, E.S.; Lee, M.; et al. Ferrostatin-1 Prevents Salivary Gland Dysfunction in an Ovariectomized Rat Model by Suppressing Mitophagy-Driven Ferroptosis. Antioxidants (Basel) 2025, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.M.; Park, G.C.; Lee, H.W.; Bang, S.Y.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, W.T.; Shin, S.C.; Cheon, Y.I.; Lee, B.J. Amifostine and melatonin attenuate radiation-induced oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrotic remodeling in the vocal folds and subglottic glands of rats. Biomed Pharmacother 2025, 192, 118658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, G.C.; Bang, S.Y.; Kim, J.M.; Shin, S.C.; Cheon, Y.I.; Kim, K.M.; Park, H.; Sung, E.S.; Lee, M.; Lee, J.C.; et al. Inhibiting Ferroptosis Prevents the Progression of Steatotic Liver Disease in Obese Mice. Antioxidants (Basel) 2024, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garbowska, M.; Lukaszuk, B.; Miklosz, A.; Wroblewski, I.; Kurek, K.; Ostrowska, L.; Chabowski, A.; Zendzian-Piotrowska, M.; Zalewska, A. Sphingolipids metabolism in the salivary glands of rats with obesity and streptozotocin induced diabetes. J Cell Physiol 2017, 232, 2766–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, Y.; Morozumi, T.; Takahashi, T.; Saruta, J.; Sakaguchi, W.; To, M.; Kubota, N.; Shimizu, T.; Kamata, Y.; Kawata, A.; et al. Effect of High Fat and Fructo-Oligosaccharide Consumption on Immunoglobulin A in Saliva and Salivary Glands in Rats. Nutrients 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, K.; Luo, P.; Guo, Z.; Yang, L.; Pu, J.; Han, F.; Cai, F.; Tang, J.; Wang, X. Lipid Metabolism: An Emerging Player in Sjogren's Syndrome. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 2025, 68, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, D.; Chen, X.; Kang, R.; Kroemer, G. Ferroptosis: molecular mechanisms and health implications. Cell Res 2021, 31, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Zhou, X.; Xie, F.; Zhang, L.; Yan, H.; Huang, J.; Zhang, C.; Zhou, F.; Chen, J.; Zhang, L. Ferroptosis in cancer and cancer immunotherapy. Cancer Commun (Lond) 2022, 42, 88–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ru, Q.; Li, Y.; Chen, L.; Wu, Y.; Min, J.; Wang, F. Iron homeostasis and ferroptosis in human diseases: mechanisms and therapeutic prospects. Signal Transduct Target Ther 2024, 9, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, W.; Wang, B.; Huang, R.; Zhang, C.; Fu, P.; Ma, L. Ferroptosis in organ fibrosis: From mechanisms to therapeutic medicines. J Transl Int Med 2024, 12, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Zong, L.; Lin, J.; Liu, X.; Ning, S. Emerging roles of ferroptosis in pulmonary fibrosis: current perspectives, opportunities and challenges. Cell Death Discov 2024, 10, 301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, G.; Liao, H.; Li, R. Ferroptosis and renal fibrosis: mechanistic insights and emerging therapeutic targets. Ren Fail 2025, 47, 2498629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Q.; Luo, Y.; Xia, Q.; He, K. Ferroptosis and Liver Fibrosis. Int J Med Sci 2021, 18, 3361–3366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedmann Angeli, J.P.; Schneider, M.; Proneth, B.; Tyurina, Y.Y.; Tyurin, V.A.; Hammond, V.J.; Herbach, N.; Aichler, M.; Walch, A.; Eggenhofer, E.; et al. Inactivation of the ferroptosis regulator Gpx4 triggers acute renal failure in mice. Nat Cell Biol 2014, 16, 1180–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, C.; Zhao, Y.; Gao, G. Mitochondria regulation in ferroptosis. Eur J Cell Biol 2020, 99, 151058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Kon, N.; Li, T.; Wang, S.J.; Su, T.; Hibshoosh, H.; Baer, R.; Gu, W. Ferroptosis as a p53-mediated activity during tumour suppression. Nature 2015, 520, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, F.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, H.; Liu, J.; Yang, S.; Luo, X.; Liu, W.; Zheng, H.; Liu, Q.; Cui, Y.; et al. Dynamic O-GlcNAcylation coordinates ferritinophagy and mitophagy to activate ferroptosis. Cell Discov 2022, 8, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C.; Wu, Z.; Wang, L.; Yang, Q.; Huang, J.; Huang, J. A Mitophagy-Related Gene Signature for Subtype Identification and Prognosis Prediction of Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpellini, C.; Klejborowska, G.; Lanthier, C.; Hassannia, B.; Vanden Berghe, T.; Augustyns, K. Beyond ferrostatin-1: a comprehensive review of ferroptosis inhibitors. Trends Pharmacol Sci 2023, 44, 902–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karbakhsh Ravari, F.; Ghasemi Gorji, M.; Rafiei, A. From iron-driven cell death to clot formation: The emerging role of ferroptosis in thrombogenesis. Biomed Pharmacother 2025, 189, 118328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Miao, R.; Zhong, J. Targeting Iron Metabolism and Ferroptosis as Novel Therapeutic Approaches in Cardiovascular Diseases. Nutrients 2023, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

General physiological parameters in C57BL/6, ob/ob, FER, and DFO groups. (A) Body weight, (B) daily food intake, and (C) fasting blood glucose levels were measured in C57BL/6 control, untreated ob/ob, and ob/ob mice treated with either ferrostatin-1 (FER) or deferoxamine (DFO) throughout the experimental period. FER, ferrostatin-1-treated ob/ob mice; DFO, deferoxamine-treated ob/ob mice.

Figure 1.

General physiological parameters in C57BL/6, ob/ob, FER, and DFO groups. (A) Body weight, (B) daily food intake, and (C) fasting blood glucose levels were measured in C57BL/6 control, untreated ob/ob, and ob/ob mice treated with either ferrostatin-1 (FER) or deferoxamine (DFO) throughout the experimental period. FER, ferrostatin-1-treated ob/ob mice; DFO, deferoxamine-treated ob/ob mice.

Figure 2.

Lipid accumulation in the salivary glands of C57BL/6, ob/ob, FER, and DFO groups. (A) Representative H&E-stained images showing structural changes in the salivary glands. Lipid droplet-like cytoplasmic vacuoles are indicated by red circles in the ob/ob group. (B) Transmission electron microscopy images illustrating cytoplasmic lipid droplets (L), mitochondria (M), nuclei (N), and glandular components (G). (C) Relative mRNA expression levels of ACC, SREBP-1c, and ChREBP in the salivary glands that were analyzed by qPCR. Elevated expression in the ob/ob group was normalized to control levels following treatment with ferrostatin-1 or deferoxamine. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Columns and error bars represent the mean ± standard deviation. FER, ferrostatin-1-treated ob/ob mice; DFO, deferoxamine-treated ob/ob mice.

Figure 2.

Lipid accumulation in the salivary glands of C57BL/6, ob/ob, FER, and DFO groups. (A) Representative H&E-stained images showing structural changes in the salivary glands. Lipid droplet-like cytoplasmic vacuoles are indicated by red circles in the ob/ob group. (B) Transmission electron microscopy images illustrating cytoplasmic lipid droplets (L), mitochondria (M), nuclei (N), and glandular components (G). (C) Relative mRNA expression levels of ACC, SREBP-1c, and ChREBP in the salivary glands that were analyzed by qPCR. Elevated expression in the ob/ob group was normalized to control levels following treatment with ferrostatin-1 or deferoxamine. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Columns and error bars represent the mean ± standard deviation. FER, ferrostatin-1-treated ob/ob mice; DFO, deferoxamine-treated ob/ob mice.

Figure 4.

Histological and transcriptional assessment of profibrotic and stress-responsive markers in obese salivary glands. Immunohistochemical staining and mRNA expression analysis were performed to assess fibrotic and inflammatory changes in the salivary glands of C57BL/6, ob/ob, DFO, and FER groups. (A, B) TGF-β and collagen I expression were increased in the ob/ob group and this decreased following treatment, as confirmed by both immunostaining and qPCR. Ferrostatin-1 suppressed TGF-β expression more effectively whereas deferoxamine more markedly reduced collagen I. (C) Metallothionein (MT)—a stress-inducible protein involved in oxidative and inflammatory responses—showed increased immunoreactivity in the ob/ob group and was comparably reduced by both treatments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Columns and error bars represent the mean ± standard deviation. FER, ferrostatin-1-treated ob/ob mice; DFO, deferoxamine-treated ob/ob mice.

Figure 4.

Histological and transcriptional assessment of profibrotic and stress-responsive markers in obese salivary glands. Immunohistochemical staining and mRNA expression analysis were performed to assess fibrotic and inflammatory changes in the salivary glands of C57BL/6, ob/ob, DFO, and FER groups. (A, B) TGF-β and collagen I expression were increased in the ob/ob group and this decreased following treatment, as confirmed by both immunostaining and qPCR. Ferrostatin-1 suppressed TGF-β expression more effectively whereas deferoxamine more markedly reduced collagen I. (C) Metallothionein (MT)—a stress-inducible protein involved in oxidative and inflammatory responses—showed increased immunoreactivity in the ob/ob group and was comparably reduced by both treatments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. Columns and error bars represent the mean ± standard deviation. FER, ferrostatin-1-treated ob/ob mice; DFO, deferoxamine-treated ob/ob mice.

Figure 5.

Expression of salivary gland functional proteins α-amylase and AQP5 in C57BL/6, ob/ob, DFO, and FER groups. (A) Immunohistochemical staining of α-amylase showed prominent cytoplasmic expression in the acinar cells of C57BL/6 mice, reduced staining in the ob/ob group, and restored levels following treatment, with stronger recovery observed in the FER group. (B) AQP5 staining was localized to the apical membrane of acinar cells and was markedly reduced in the ob/ob mice; however, this was restored in both treatment groups, with ferrostatin-1 inducing a more prominent effect. FER, ferrostatin-1-treated ob/ob mice; DFO, deferoxamine-treated ob/ob mice.

Figure 5.

Expression of salivary gland functional proteins α-amylase and AQP5 in C57BL/6, ob/ob, DFO, and FER groups. (A) Immunohistochemical staining of α-amylase showed prominent cytoplasmic expression in the acinar cells of C57BL/6 mice, reduced staining in the ob/ob group, and restored levels following treatment, with stronger recovery observed in the FER group. (B) AQP5 staining was localized to the apical membrane of acinar cells and was markedly reduced in the ob/ob mice; however, this was restored in both treatment groups, with ferrostatin-1 inducing a more prominent effect. FER, ferrostatin-1-treated ob/ob mice; DFO, deferoxamine-treated ob/ob mice.

Figure 6.

Mitochondrial ultrastructure and selective autophagy markers in salivary glands. (A) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of the salivary glands showing mitochondrial morphology in each group. The ob/ob group exhibited extensive mitochondrial swelling, cristae loss, and outer membrane disruption; however, these alterations were alleviated in the FER and DFO groups. (B) Western blot analysis of autophagy- and mitophagy-related proteins. LC3B expression was markedly increased in the ob/ob group and reduced following treatment. In contrast, p62 levels were lowest in the ob/ob group and partially restored by both ferrostatin-1 and deferoxamine. PINK1 and PRKN were elevated in the ob/ob group and decreased following treatment, with PINK1 expression better maintained in the FER group. NCOA4 was highly expressed in the ob/ob group but was suppressed in all other groups. FER, ferrostatin-1-treated ob/ob mice; DFO, deferoxamine-treated ob/ob mice.

Figure 6.

Mitochondrial ultrastructure and selective autophagy markers in salivary glands. (A) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of the salivary glands showing mitochondrial morphology in each group. The ob/ob group exhibited extensive mitochondrial swelling, cristae loss, and outer membrane disruption; however, these alterations were alleviated in the FER and DFO groups. (B) Western blot analysis of autophagy- and mitophagy-related proteins. LC3B expression was markedly increased in the ob/ob group and reduced following treatment. In contrast, p62 levels were lowest in the ob/ob group and partially restored by both ferrostatin-1 and deferoxamine. PINK1 and PRKN were elevated in the ob/ob group and decreased following treatment, with PINK1 expression better maintained in the FER group. NCOA4 was highly expressed in the ob/ob group but was suppressed in all other groups. FER, ferrostatin-1-treated ob/ob mice; DFO, deferoxamine-treated ob/ob mice.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for qPCR analysis.

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for qPCR analysis.

| GENE |

Sequence (5‘-3‘) |

| Forward |

Reverse |

| GAPDH |

AGCCCAAGATGCCCTTCAGT

|

CCGTGTTCCTACCCCCAATG

|

| SREBP-1c |

ACGGAGCCATGGATTGCACA

|

AAGGGTGCAGGTGTCACCTT

|

| ChREBP |

CTGGGGACCTAAACAGGAGC

|

GAAGCCACCCTATAGCTCCC

|

| ACC |

ATGGGCGGAATGGTCTCTTTC

|

TGGGGACCTTGTCTTCATCAT

|

| TGF-β1 |

GTGTGGAGCAACATGTGGAACTCTA

|

TTGGTTCAGCCACTGCCGTA

|

| Collagen I |

CCTCAGGGTATTGCTGGACAAC

|

CAGAAGGACCTTGTTTGCCAGG

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).