1. Introduction

Cognition encompasses the brain's neural processes and signal integration mechanisms that facilitate learning, memory, and decision-making. Dementia is characterized by a decline in cognitive function severe enough to impair an individual's ability to perform daily activities independently. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that over 55 million individuals globally are affected by dementia, with prevalence rates increasing annually. This trend imposes significant economic burdens worldwide and escalates caregiving demands on families. Cognitive decline generally advances through progressive stages, and timely intervention with suitable strategies may mitigate the progression of neurodegeneration [

1].

Subjective cognitive decline (SCD) refers to an individual's perception of a decline in cognitive abilities, despite performing within the normal range on objective cognitive tests. In recent years, it has been considered a possible transitional stage to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and an early risk factor for dementia [

2]. Mild cognitive impairment is often a precursor to dementia in older adults; although patients typically maintain their ability to perform daily self-care activities, memory impairments have already begun to appear. Currently, there are limited treatment options available for SCD and MCI, highlighting the need to find more effective interventions to slow cognitive decline.

Good exercise and dietary habits, as well as improved sleep quality, help prevent or treat cognitive impairment by modulating neuroinflammation, metabolic health, and the gut-brain axis, which is a bidirectional communication network involving the central nervous system (CNS), autonomic nervous system, enteric nervous system (ENS), and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis [

3]. Gut microbiota are key regulators of the gut-brain axis, influencing host physiology and cognitive function through the production of neuroactive molecules and modulation of immune and endocrine pathways. Microbial metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), and serotonin precursors are secreted by gut bacteria and can signal to the brain via the enteric nervous system, vagus nerve, and systemic circulation, thereby affecting central nervous system activity and cognitive processes [

4,

5]. The brain, in turn, can influence gut microbial composition and function through the release of neurotransmitters and neuroendocrine signals [

4].

Alterations in gut microbiota composition—often driven by aging, stress, or dietary habits—can increase intestinal permeability and promote local and systemic inflammation, which may contribute to neuroinflammation and cognitive decline [

6,

7]. Diets rich in fiber, polyphenols, and prebiotics support beneficial microbial populations, enhance SCFA production, and reduce inflammatory signaling, while Westernized diets high in fat and low in fiber promote dysbiosis and increased risk of cognitive impairment [

5,

7,

8]. Interventions such as probiotics, prebiotics, and psychobiotics have shown potential to improve cognitive outcomes by restoring microbial balance and modulating neuroimmune and neuroendocrine pathways [

9,

10]. In summary, dietary habits can modulate gut microbial composition, which in turn impacts the gut-brain axis and cognitive function through neuroactive metabolites, immune signaling, and regulation of intestinal barrier integrity [

5,

7,

8].

Growing evidence indicates a strong bidirectional relationship between the gut microbiota and brain health. The gut–brain axis operates through several key mechanisms. First, neurotransmitters and short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) produced in the gut can directly signal the brain via the vagus nerve, whereas long-chain fatty acids activate vagal pathways through cholecystokinin (CCK) [

11,

12]. Second, hormones, neurotransmitters, and immune signaling molecules are able to cross the intestinal barrier, enter the systemic circulation, and ultimately reach the central nervous system through the blood–brain barrier (BBB) [

13,

14]. Third, microbial-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) and microbial metabolites can stimulate peripheral immune cells, which in turn modulate neuroinflammation and brain function [

15,

16]. Together, these pathways highlight the potential of gut microbiota–targeted interventions to influence cognitive processes and neurological health.

Current evidence indicates that Lactococcus lactis is a safe, non-pathogenic, and edible strain, with genomic analyses confirming the absence of virulence genes. Studies have further shown that L. lactis produces substantial amounts of extracellular vesicles (EVs) that carry bioactive molecules with potential regulatory functions. In neuroprotection research, EVs and secreted metabolites derived from lactic acid bacteria, including Lactococcus and Lactobacillus species, have been reported to enhance brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression and mitigate amyloid beta 1–42–induced neuronal toxicity [

17,

18,

19]. Despite growing evidence linking the gut microbiota to cognitive health through neurochemical, immune, and vagal pathways, clinical trials investigating microbiome-based interventions in early cognitive decline remain limited. No human studies have evaluated probiotics engineered to influence neurotrophic pathways—such as ExoBDNF-producing strains—or examined their effects on cognitive performance, psychological well-being, and sleep in populations with Subjective Cognitive Decline (SCD) or Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI). This lack of evidence represents a key gap in identifying feasible and non-pharmacological strategies to slow cognitive deterioration. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate the effects of an ExoBDNF-producing lactic acid bacteria supplement on cognitive function, psychological outcomes, and sleep quality in individuals with SCD or MCI using an open-label, single-group pretest–posttest design. This pilot trial seeks to provide preliminary evidence to support the development of future randomized controlled studies targeting the gut–brain axis in early cognitive decline.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Participants were eligible for inclusion if they were adults aged 18 years or older who were fully conscious, able to communicate, and willing to participate, and if they voluntarily provided written informed consent; a total of 30 volunteers meeting these criteria were enrolled in the study.

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

Participants met criteria for either Subjective Cognitive Decline (SCD) or Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI). Individuals classified as SCD reported a persistent decline in memory over the past five years, corroborated by an informant such as a family member, friend, or colleague. SCD was further defined by a Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) score greater than 25, a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score greater than 27, and a total score of 0–24 on the Subjective Cognitive Decline Questionnaire. Individuals classified as MCI were required to have a MoCA score between 11 and 25 and an MMSE score between 24 and 27.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

Participants were excluded if pregnancy was confirmed or expected, or if they had a history of gallbladder or gastrointestinal disease, gout, porphyria, gastric bariatric surgery, hypertension (≥160/100 mmHg after 10 minutes of rest), diuretic use, cardiac disease, hepatic or renal dysfunction, thyroid disorders, Cushing’s syndrome, malignancy, severe sensory impairment, intellectual disability, or any condition that could interfere with study outcomes.

They were also excluded if they had a history of brain surgery, severe traumatic, neurovascular, infectious, or other major brain injury, epilepsy, or neurological disorders—including traumatic brain injury with loss of consciousness longer than 24 hours or post-traumatic amnesia lasting more than 7 days—or if they had consumed probiotics within two weeks prior to screening or participated in another clinical trial within four weeks before screening.

2.4. Study Procedures

This study was designed as a single-group pretest–posttest, open-label trial. At baseline (week 0), enrolled participants underwent physical examinations and completed initial questionnaires. Starting from the first week, daily administration of ExoBDNF supplementation (ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT06968299), was initiated at a dosage of 1 × 10

10 colony-forming units (CFU) [

20], which was maintained through the end of week 9. Throughout the intervention period, participants were instructed to maintain their usual dietary and lifestyle habits.

After starting the diet, subjects filled out a daily diary that included questions about study product intake, other food intake, bowel movement frequency, stool quality (consistency and color), any medications received, and any unpleasant symptoms such as diarrhea, constipation, vomiting, flatulence, and discomfort. It is expected that this project will help clarify whether supplementation with Pediococcus acidilactici ExoBDNF can help improve cognitive ability, sleep or mental health.

2.5. Outcome Measurement

The primary endpoint was the change in the Subjective Cognitive Decline Questionnaire (SCD-Q) score from baseline to week 8 [

21] , comparing the probiotic intervention group with the placebo group, to determine whether a statistically significant difference was observed.

The SCD-Q serves as an instrument to evaluate self-perceived cognitive deterioration by systematically documenting an individual's subjective experience of cognitive changes over the preceding two years. The SCD-Q comprises two principal components: "MyCog," completed by the individual, and "TheirCog," completed by an informant or caregiver. The "MyCog" section contains 24 items designed to assess perceived alterations in memory, language, and executive functioning. Each component of the SCD-Q—both "MyCog" (self-report) and "TheirCog" (informant-report)—yields a score ranging from 0 to 24. Items are scored dichotomously (yes/no), with higher scores reflecting greater perceived cognitive decline. This scoring methodology is substantiated by validation studies documented in the medical literature [

22,

23].

Secondary endpoints included computerized cognitive assessments using the Cognitive Test Battery [

24], comprising a Go/No-Go task to evaluate attention and response inhibition, a task-switching paradigm to assess cognitive flexibility, and a working memory task (Corsi block-tapping) to measure spatial short-term memory. Participants also completed validated questionnaires, including the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [

25], Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) [

26]. The MoCA provides a comprehensive, highly sensitive assessment of attention and memory through tasks such as digit span, vigilance, serial subtraction, five-word learning, and delayed recall with cueing. It also evaluates executive and visuospatial functions, enabling the detection of subtle cognitive deficits—especially mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and early dementia—and helps distinguish amnestic from non-amnestic cognitive syndromes [

27]. MMSE is more effective for detecting moderate-to-severe dementia but frequently underestimates impairment in patients with mild cognitive deficits or single-domain impairment [

28].

Other secondary endpoints included Taiwan Cognition Questionnaire (TCQ) [

29], Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21) [

30], and the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) [

31]. The TCQ assesses subjective cognitive complaints in Taiwanese adults, focusing on memory, attention, and executive function. Culturally adapted for the population of Taiwan, it is a self-report tool useful for epidemiological research and cognitive screening. It allows quick identification of perceived cognitive difficulties that may aid early detection of cognitive impairment [

32]. The DASS-21 is a short self-report measure assessing depression, anxiety, and stress through three seven-item subscales rated on a 4-point Likert scale. Higher scores indicate greater severity of emotional disturbance. It demonstrates strong structural validity and internal consistency, allowing clear distinction among the three emotional states. Widely used in clinical and research settings, it serves as an efficient tool for screening psychological distress [

33,

34]. The PSQI is a widely used self-report measure of sleep quality over the past month, covering seven domains: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleep medication, and daytime dysfunction. It yields a global score distinguishing good and poor sleepers and has been validated in clinical and non-clinical samples, including those in Taiwan. Its strengths include comprehensive coverage of sleep domains, strong reliability, and high sensitivity to sleep dysfunction [

35,

36].

2.6. Statistics

Comparative analyses between pre-intervention and post-intervention time points were performed utilizing either the paired t-test or the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, implemented through SPSS statistical software version 24.0 (IBM Co[33,34rp., Chicago, IL, USA). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Normality was assessed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Correlation between SCD-Q and DASS-21 data was analyzed by Spearman correlation analysis. The intervention was considered to have a supportive modulatory effect if statistically significant differences were observed in within-subject comparisons, accompanied by improvements in key clinical symptoms.

3. Results

A total of 30 participants, comprising 29 individuals with subjective cognitive decline (SCD) and 1 individual with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), completed the 9-week ExoBDNF supplementation protocol. The mean age of the participants was 40.97 years (± 12.05), with females representing 70% of the sample.

Table 1 summarizes baseline (week 0) and post-intervention outcomes (week 9).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and data collected at baseline and following the completion of ExoBDNF supplementation.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics and data collected at baseline and following the completion of ExoBDNF supplementation.

| Variables |

Baseline

(Mean ± SD) |

Week 9

(Mean ± SD) |

Paired t-test/

Wilcoxon signed-rank test |

P |

| Age |

40.97 ± 12.05 |

| Sex (Female): n (%) |

21 (70%) |

| Questionnaire |

| SCD-Q |

50.6 ± 6.4 |

37.9 ± 8.4 |

t = 7.8 |

< 0.001 |

| TCQ |

7.7 ± 3.1 |

3.4 ± 2.3 |

t = 7.3 |

< 0.001 |

| PSQI |

8.5 ± 2.3 |

6.3 ± 2.9 |

t = 4.0 |

< 0.001 |

| DASS-21 |

22.0 ± 12.6 |

11.6 ± 9.0 |

z = – 4.5 |

< 0.001 |

| MoCA |

27.5 ± 2.0 |

28.3 ± 2.3 |

z = – 2.0 |

0.047 |

| MMSE |

29.1 ± 1.2 |

29.2 ± 1.0 |

z = – 0.6 |

0.542 |

| Cognitive Test Battery |

| Go/No Go |

| correction rate (%) |

95.0 ± 6.3 |

97.3 ± 6.0 |

z = – 2.0 |

0.046 |

| reaction time (s) |

640.0 ± 97.1 |

627.5 ± 71.8 |

z = 0.5 |

0.600 |

| Task-switching |

| correction rate (%) |

95.7 ± 5.2 |

96.4 ± 8.3 |

z = – 1.9 |

0.053 |

| reaction time (s) |

1063.0 ± 287.0 |

919.3 ± 215.7 |

z = – 3.8 |

< 0.001 |

| Working memory |

| correction rate (%) |

50.8 ± 20.1 |

52.0 ± 20.8 |

z = – 0.3 |

0.779 |

| reaction time (s) |

3827.0 ± 908.6 |

3542.5 ± 555.2 |

z = – 2.1 |

0.039 |

3.1. Subjective Cognitive Outcomes

SCD-Q scores decreased from 50.6 ± 6.4 at baseline to 37.9 ± 8.4 at week 9 (t = 7.8, p < 0.001), indicating reduced self-perceived cognitive decline. TCQ scores improved from 7.7 ± 3.1 to 3.4 ± 2.3 (t = 7.3, p < 0.001), reflecting reduced subjective cognitive complaints.

3.2. Psychological and Sleep Measures

DASS-21 total scores decreased from 22.0 ± 12.6 to 11.6 ± 9.0 (z = – 4.5, p < 0.001)., indicating significant reductions in psychological distress. PSQI scores declined from 8.5 ± 2.3 to 6.3 ± 2.9 (t = 4.0, p < 0.001), suggesting better overall sleep.

3.3. Global Cognitive Function

MoCA scores increased from 27.5 ± 2.0 to 28.3 ± 2.3 (z = – 2.0, p = 0.047). MMSE scores showed no significant change (29.1 ± 1.2 to 29.2 ± 1.0, p = 0.542).

3.4. Computerized Cognitive Test Battery

3.4.1. Go/No-Go (Attention and Inhibitory Control)

Correct response rate improved significantly (95.0 ± 6.3% to 97.3 ± 6.0 %; z = – 2.0, p = 0.046). Reaction time showed no significant change.

3.4.2. Task-Switching (Cognitive Flexibility)

Correct rate showed a trend toward improvement but did not reach significance (p = 0.053). Reaction time improved substantially (1063.0 ± 287.0 s to 919.3 ± 215.7 s; z = – 3.8, p < 0.001).

3.4.3. Working Memory (Corsi Block-Tapping)

Global WM performance was largely unchanged in accuracy (50.8 ± 20.1% to 52.0 ± 20.8 %; p = 0.779), but reaction time improved modestly (3827.0 ± 908.6 s to 3542.5 ± 555.2 s; z = – 2.1, p = 0.039).

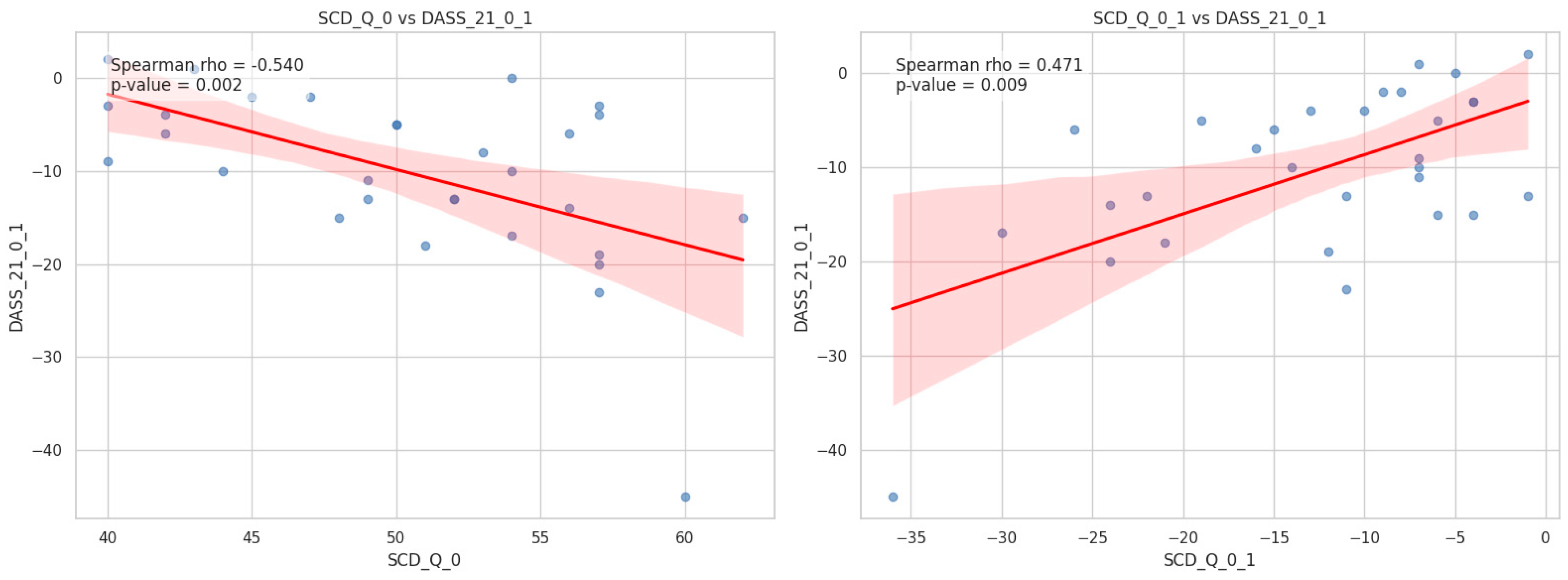

3.5. Correlation Between SCD-Q and DASS-21 Data

Baseline scores on the SCD-Q demonstrated a significant negative correlation with the changes in DASS-21 scores observed between week 1 and week 9 (Spearman’s r = – 0.54, p = 0.002).

The variations in SCD-Q scores demonstrated a positive correlation with the variations in DASS-21 scores from week 1 to week 9 (Spearman’s r = 0.471, p = 0.009).

Figure 1 illustrates the scatter plots with best-fit regression lines and 95% confidence intervals. First, a significant negative correlation was observed between baseline SCD scores and the longitudinal change in DASS-21 scores (rho = – 0.54, p = 0.002). This suggests that participants with higher initial subjective cognitive complaints tended to show a greater decrease in emotional distress levels over time. Second, we found a significant positive correlation between the change in SCD scores and the change in DASS-21 scores (rho = 0.471, p = 0.009). This indicates that the longitudinal trajectory of subjective cognitive decline is closely associated with changes in emotional states; specifically, reductions in SCD scores were associated with concurrent reductions in DASS-21 scores.

Figure 1.

Scatter plots illustrating the associations between subjective cognitive decline (SCD) and emotional distress (DASS–21). (A) The relationship between baseline SCD scores and the change in DASS–21 scores. A significant negative correlation was found (rho = −0.540, p = 0.002). (B) The relationship between the change in SCD scores and the change in DASS-21 scores. A significant positive correlation was observed (rho = 0.471, p = 0.009). The red solid lines represent the best-fit linear regression models, and the shaded areas indicate the 95% confidence intervals.

Figure 1.

Scatter plots illustrating the associations between subjective cognitive decline (SCD) and emotional distress (DASS–21). (A) The relationship between baseline SCD scores and the change in DASS–21 scores. A significant negative correlation was found (rho = −0.540, p = 0.002). (B) The relationship between the change in SCD scores and the change in DASS-21 scores. A significant positive correlation was observed (rho = 0.471, p = 0.009). The red solid lines represent the best-fit linear regression models, and the shaded areas indicate the 95% confidence intervals.

4. Discussion

This pilot study provides initial evidence that ExoBDNF-producing Lactococcus lactis supplementation may enhance cognitive function, psychological well-being, and sleep quality in individuals with early cognitive decline. Significant reductions in subjective cognitive complaints (SCD-Q, TCQ) and modest improvements in global cognition (MoCA) suggest that the intervention may benefit individuals at a stage where cognitive changes are subtle yet clinically meaningful. Because subjective decline often precedes measurable impairment, these findings highlight the potential of ExoBDNF as an early-stage supportive strategy.

Improvements in psychological distress and sleep quality further reinforce the intervention’s relevance, as mood disturbances and poor sleep are closely linked to worsening cognitive outcomes [

37,

38]. The concurrent changes across these domains suggest that ExoBDNF may modulate shared gut–brain pathways involved in emotional regulation, stress response, and cognitive processing.

Concurrently with the present investigation, meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials have consistently revealed enhancements in global cognitive function, memory, processing speed, and spatial ability subsequent to probiotic supplementation. These improvements are characterized by standardized mean differences ranging from 0.4 to 0.6 in older adult populations and individuals experiencing cognitive impairment [

39,

40]. The effect is most pronounced with single-strain formulations, higher doses (e.g., ≥1×10

9 CFU/g), and intervention durations of at least 12 weeks [

39,

40]. Mechanistically, probiotics are proposed to confer cognitive advantages through the modulation of the gut-brain axis. This includes the attenuation of neuroinflammatory processes, the upregulation of neurotrophic factors such as BDNF, and the regulation of neurotransmitter metabolism [

39,

41]. In healthy adults and younger populations, the evidence for cognitive enhancement is less robust and often inconsistent, with some studies showing no significant effect [

42,

43].

At the neural systems level, studies in schizophrenia have demonstrated that dysfunctional connectivity—particularly excessive high-frequency resting-state synchrony in regions such as the cuneus, superior temporal gyrus, and fusiform gyrus—is strongly associated with attentional impairments. These findings highlight that cognitive deficits can arise from maladaptive large-scale oscillatory patterns that impair the precision of information processing [

44]. Such evidence converges with neuromodulation research showing that targeted modulation of cortical excitability (e.g., rTMS, tDCS, tACS) can selectively improve working memory, attention, and executive function through rebalancing dysfunctional prefrontal–temporal–parietal circuits [

45]. Integrating these perspectives, the current findings suggest that ExoBDNF supplementation may support cognition through mechanisms conceptually similar to neuromodulation: both strategies ultimately influence neural plasticity and large-scale network efficiency, albeit through different biological routes. Whereas rTMS and tDCS act directly upon cortical excitability and connectivity, gut-derived metabolites and bacterial extracellular vesicles (EVs) may indirectly enhance neurotrophic signaling—such as BDNF pathways—thereby strengthening synaptic resilience and cognitive network function. The observed correlation between improved subjective cognition and reduced emotional distress further supports a systems-level view in which emotional regulation and cognitive performance share overlapping circuit-level substrates and may respond synergistically to interventions that restore network balance. Notably, the EEG-based evidence from schizophrenia research demonstrates that cognitive impairment emerges when connectivity patterns become either hyper-synchronous or inefficiently coordinated. This lends additional theoretical support to microbiome-based interventions: if gut-brain modulation enhances neuroplasticity, it may help prevent or attenuate maladaptive oscillatory states that precede measurable cognitive decline, particularly in early-stage populations such as SCD. From a translational standpoint, the convergence of probiotic-based modulation and neuromodulation research highlights a promising multimodal framework in which peripheral (microbiome) and central (brain stimulation) interventions could be combined to optimize cognitive outcomes.

Safety data demonstrate that probiotics are generally well tolerated and do not result in a statistically significant increase in adverse events relative to placebo [

46]. However, the reliability of the current evidence remains variable, underscoring the need for further well-designed clinical trials to establish the most effective strain selection, dosage, and treatment duration, and to confirm efficacy in more heterogeneous populations [

47].

The primary limitation of this study is its open-label, single-group pretest–posttest design, which lacks a placebo control and randomization. Without a comparison group, improvements may be influenced by expectancy effects, practice effects on cognitive tests, regression to the mean, or natural symptom fluctuations, rather than the ExoBDNF supplementation itself. Additionally, the small sample size (n = 30) and the predominance of participants with SCD limit statistical power and reduce generalizability to broader SCD/MCI populations. These design constraints prevent causal inference and highlight the need for larger, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials to confirm the efficacy of ExoBDNF supplementation. Another limitation is the reliance on self-report measures for key outcomes such as subjective cognition, psychological distress, and sleep quality. Although these instruments are validated, self-reported data are inherently vulnerable to response bias, mood-related influences, and participants’ expectations, which may inflate perceived improvements. Furthermore, the absence of biological markers—such as inflammatory cytokines, gut microbiota profiling, or BDNF levels—limits the ability to verify whether the observed changes reflect underlying neurobiological or gut–brain axis mechanisms.

5. Conclusions

This pilot study suggests that ExoBDNF-producing Lactococcus lactis may improve subjective cognition, psychological well-being, sleep quality, and selected cognitive functions in individuals with early cognitive decline. While these findings are encouraging, the study’s small sample size and uncontrolled design limit causal interpretation. Larger randomized, placebo-controlled trials are needed to validate these preliminary results and clarify the therapeutic potential of ExoBDNF supplementation.

Author Contributions

Hsin-An Chang: conceptualization; Li-Fen Chen: writing-review and editing; Ching-En Lin: writing-original draft preparation; Wen-Hui Fang: resources and supervision; Chuan-Chia Chang: funding acquisition.

Funding

Dr Hsin-An Chang was supported by the faculty grant of Tri-Service General Hospital (VTA114-T-1-1 and TSGH-B-114024) and by a fund from the National Science and Technology Council of Taiwanese Government (NSTC-112-2314-B-016-017-MY3). SunWay Biotech Co., Ltd provided funds for the clinical trial. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Institutional Review Board Statement

All experimental procedures conformed to the standards set by the latest revision of the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the ethics committee of Tri–Service General Hospital (TSGH, IRB No.: B202505081).

Informed Consent Statement

Participants who were willing to participate provided written informed consent.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere gratitude to all participants for their time, commitment, and contributions to this study. We also thank the clinical and research staff who supported data collection and study coordination.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest related to this study.

Abbreviations

| SD |

standard deviation |

| SCD-Q |

Subjective Cognitive Decline Questionnaire |

| TCQ |

Taiwan Cognition Questionnaire |

| PSQI |

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index |

| DASS-21 |

Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21items |

| MoCA |

Montreal Cognitive Assessment |

| MMSE |

Mini-Mental State Examination |

References

- Klimova, B.; Valis, M.; Kuca, K. Cognitive decline in normal aging and its prevention: a review on non-pharmacological lifestyle strategies. Clin Interv Aging 2017, 12, 903–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, C.A.; Bouldin, E.D.; McGuire, L.C. Subjective Cognitive Decline Among Adults Aged ≥45 Years - United States, 2015-2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2018, 67, 753–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuigunov, D.; Sinyavskiy, Y.; Nurgozhin, T.; Zholdassova, Z.; Smagul, G.; Omarov, Y.; Dolmatova, O.; Yeshmanova, A.; Omarova, I. Precision Nutrition and Gut-Brain Axis Modulation in the Prevention of Neurodegenerative Diseases. Nutrients 2025, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.T.; Zohair, M.; Khan, A.; Kashif, A.; Mumtaz, S.; Muskan, F. From Gut to Brain: The roles of intestinal microbiota, immune system, and hormones in intestinal physiology and gut-brain-axis. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2025, 607, 112599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.S. Roles of Diet-Associated Gut Microbial Metabolites on Brain Health: Cell-to-Cell Interactions between Gut Bacteria and the Central Nervous System. Adv Nutr 2024, 15, 100136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doroszkiewicz, J.; Groblewska, M.; Mroczko, B. The Role of Gut Microbiota and Gut-Brain Interplay in Selected Diseases of the Central Nervous System. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, T.M.; Valsamakis, G.; Mastorakos, G.; Hanson, P.; Kyrou, I.; Randeva, H.S.; Weickert, M.O. Dietary Influences on the Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Int J Mol Sci 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castells-Nobau, A.; Mayneris-Perxachs, J.; Fernández-Real, J.M. Unlocking the mind-gut connection: Impact of human microbiome on cognition. Cell Host Microbe 2024, 32, 1248–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kezer, G.; Paramithiotis, S.; Khwaldia, K.; Harahap, I.A.; Čagalj, M.; Šimat, V.; Smaoui, S.; Elfalleh, W.; Ozogul, F.; Esatbeyoglu, T. A comprehensive overview of the effects of probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics on the gut-brain axis. Front Microbiol 2025, 16, 1651965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrio, C.; Arias-Sánchez, S.; Martín-Monzón, I. The gut microbiota-brain axis, psychobiotics and its influence on brain and behaviour: A systematic review. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2022, 137, 105640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hwang, Y.K.; Oh, J.S. Interaction of the Vagus Nerve and Serotonin in the Gut-Brain Axis. Int J Mol Sci 2025, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicks, L.M.T. Gut Bacteria and Neurotransmitters. Microorganisms 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Lu, Y. The microbiota-gut-brain axis and central nervous system diseases: from mechanisms of pathogenesis to therapeutic strategies. Front Microbiol 2025, 16, 1583562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Y.; Dhingra, R.; Zhang, Z.; Ball, L.M.; Zylka, M.J.; Lu, K. Toward Elucidating the Human Gut Microbiota-Brain Axis: Molecules, Biochemistry, and Implications for Health and Diseases. Biochemistry 2022, 61, 2806–2821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasarello, K.; Cudnoch-Jedrzejewska, A.; Czarzasta, K. Communication of gut microbiota and brain via immune and neuroendocrine signaling. Front Microbiol 2023, 14, 1118529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aijaz, M.; Ahmad, M.; Ahmad, S.; Afzal, M.; Kothiyal, P. The gut-brain axis: role of gut microbiota in neurological disease pathogenesis and pharmacotherapeutics. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Hu, L.; Gao, B.; Yang, R.; Huang, Y.; Li, P.; Shang, N. Lactococcus lactis-derived extracellular vesicles: A novel nanodelivery system enhance the properties of nisin Z. Food Chem 2025, 489, 144776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Mok, J.; Yu, H.M.; An, H.J.; Choi, G.H.; Lee, Y.S.; Kwon, K.J.; Choi, S.J.; Kim, K.H.; Kim, S.J.; et al. Comparative and pharmacological investigation of bEVs from eight Lactobacillales strains. Sci Rep 2025, 15, 27263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.R.; Park, K.M.; Lee, N.K.; Paik, H.D. Neuroprotective effects of Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and Pediococcus pentosaceus strains against oxidative stress via modulation of Nrf2-mediated antioxidation and anti-apoptosis. Brain Res 2025, 1866, 149925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, A.B.; Jacob, S. A simple practice guide for dose conversion between animals and human. J Basic Clin Pharm 2016, 7, 27–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, C.L.; Chou, K.H.; Lee, P.L.; Liang, C.S.; Kuo, C.Y.; Lin, G.Y.; Lin, Y.K.; Hsu, Y.C.; Ko, C.A.; Yang, F.C.; et al. Shared alterations in hippocampal structural covariance in subjective cognitive decline and migraine. Front Aging Neurosci 2023, 15, 1191991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rami, L.; Mollica, M.A.; García-Sanchez, C.; Saldaña, J.; Sanchez, B.; Sala, I.; Valls-Pedret, C.; Castellví, M.; Olives, J.; Molinuevo, J.L. The Subjective Cognitive Decline Questionnaire (SCD-Q): a validation study. J Alzheimers Dis 2014, 41, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moret-Tatay, C.; Zharova, I.; Iborra-Marmolejo, I.; Bernabé-Valero, G.; Jorques-Infante, M.J.; Beneyto-Arrojo, M.J. Psychometric Properties of the Subjective Cognitive Decline Questionnaire (SCD-Q) and Its Invariance across Age Groups. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2023, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adolphe, M.; Sawayama, M.; Maurel, D.; Delmas, A.; Oudeyer, P.-Y.; Sauzéon, H. An Open-Source Cognitive Test Battery to Assess Human Attention and Memory. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 13–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crum, R.M.; Anthony, J.C.; Bassett, S.S.; Folstein, M.F. Population-based norms for the Mini-Mental State Examination by age and educational level. Jama 1993, 269, 2386–2391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, S.; Simões, M.R.; Alves, L.; Santana, I. Montreal cognitive assessment: validation study for mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2013, 27, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinto, T.C.C.; Machado, L.; Bulgacov, T.M.; Rodrigues-Júnior, A.L.; Costa, M.L.G.; Ximenes, R.C.C.; Sougey, E.B. Is the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) screening superior to the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) in the detection of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and Alzheimer's Disease (AD) in the elderly? Int Psychogeriatr 2019, 31, 491–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacy, M.; Kaemmerer, T.; Czipri, S. Standardized mini-mental state examination scores and verbal memory performance at a memory center: implications for cognitive screening. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen 2015, 30, 145–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, Y.-C.; Chiu, N.-Y.; Hwang, T.-J.; Su, T.-P.; Yang, Y.-K.; Chen, C.-S.; Li, C.-T.; Su, K.-P.; Lai, T.-J.; Chang, C.-M. A Multi-Center Study for the Development of the Taiwan Cognition Questionnaire (TCQ) in Major Depressive Disorder. Journal of Personalized Medicine 2022, Vol. 12, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, J.D.; Crawford, J.R. The short-form version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS-21): construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol 2005, 44, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollayeva, T.; Thurairajah, P.; Burton, K.; Mollayeva, S.; Shapiro, C.M.; Colantonio, A. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index as a screening tool for sleep dysfunction in clinical and non-clinical samples: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev 2016, 25, 52–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.T.; Chang, W.Y.; Jang, Y. Psychometric and diagnostic properties of the Taiwan version of the Quick Mild Cognitive Impairment screen. PLoS One 2018, 13, e0207851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adu, P.; Popoola, T.; Iqbal, N.; Medvedev, O.N.; Simpson, C.R. Validating the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS-21) across Germany, Ghana, India, and New Zealand using Rasch methodology. J Affect Disord 2025, 383, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, R.H.; Paulino, Y.C.; Kawabata, Y. Validating Constructs of the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 and Exploring Health Indicators to Predict the Psychological Outcomes of Students Enrolled in the Pacific Islands Cohort of College Students. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2024, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hinz, A.; Glaesmer, H.; Brähler, E.; Löffler, M.; Engel, C.; Enzenbach, C.; Hegerl, U.; Sander, C. Sleep quality in the general population: psychometric properties of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, derived from a German community sample of 9284 people. Sleep Med 2017, 30, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, P.S.; Wang, S.Y.; Wang, M.Y.; Su, C.T.; Yang, T.T.; Huang, C.J.; Fang, S.C. Psychometric evaluation of the Chinese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (CPSQI) in primary insomnia and control subjects. Qual Life Res 2005, 14, 1943–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzierzewski, J.M.; Perez, E.; Ravyts, S.G.; Dautovich, N. Sleep and Cognition: A Narrative Review Focused on Older Adults. Sleep Med Clin 2022, 17, 205–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, R.B.; Duman, R. Neuroplasticity in cognitive and psychological mechanisms of depression: an integrative model. Mol Psychiatry 2020, 25, 530–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.; Yang, D.; Sun, J.; Li, Y. Probiotic supplements are effective in people with cognitive impairment: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutr Rev 2023, 81, 1091–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, H.; Liang, Y.; Qin, X.; Luo, Q.; Gong, X.; Gao, Q. Effects of probiotics on cognitive function across the human lifespan: a meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Nutr 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.C.; Huang, Y.Y.; Tsai, S.Y.; Kuo, Y.W.; Lin, J.H.; Ho, H.H.; Chen, J.F.; Hsia, K.C.; Sun, Y. Efficacy of Probiotic Supplements on Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor, Inflammatory Biomarkers, Oxidative Stress and Cognitive Function in Patients with Alzheimer's Dementia: A 12-Week Randomized, Double-Blind Active-Controlled Study. Nutrients 2023, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eastwood, J.; Walton, G.; Van Hemert, S.; Williams, C.; Lamport, D. The effect of probiotics on cognitive function across the human lifespan: A systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2021, 128, 311–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekete, M.; Lehoczki, A.; Major, D.; Fazekas-Pongor, V.; Csípő, T.; Tarantini, S.; Csizmadia, Z.; Varga, J.T. Exploring the Influence of Gut-Brain Axis Modulation on Cognitive Health: A Comprehensive Review of Prebiotics, Probiotics, and Symbiotics. Nutrients 2024, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, T.-C.; Huang, C.C.; Chung, Y.-A.; Park, S.Y.; Im, J.J.; Lin, Y.-Y.; Ma, C.-C.; Tzeng, N.-S.; Chang, H.-A. Resting-State EEG Connectivity at High-Frequency Bands and Attentional Performance Dysfunction in Stabilized Schizophrenia Patients. Medicina 2023, Vol. 59, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, C.-C.; Lin, K.-H.; Chang, H.-A. Exploring Cognitive Deficits and Neuromodulation in Schizophrenia: A Narrative Review. Medicina 2024, Vol. 60, 2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doron, S.; Snydman, D.R. Risk and safety of probiotics. Clin Infect Dis 2015, 60 Suppl 2, S129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ning, L.; Fan, W.; Jia, C.; Ge, L. Probiotics and Cognitive-Related Health Outcomes: An Umbrella Review of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutr Rev 2025, 83, 2144–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).