1. Introduction

Large language models now appear in nearly every knowledge domain, and their fluency suggests an ability to reason through complex problems; however, even simple conceptual tasks often reveal limitations. Models frequently struggle with conceptual boundaries that a human child navigates effortlessly. When asked to interpret a shift in perspective or to maintain an abstract stance across a conversational turn, the model tends to revert to surface-level pattern continuation. A child, by contrast, can recognize when a viewpoint changes, defend a simple belief consistently, and distinguish between a literal question and an implied one. This contrast signals a distinction between linguistic prediction and conceptual thought. The central problem is that large language models excel at pattern matching, yet they do not exhibit the capacity for conceptual reasoning that depends on an internal vantage point. Studies of model behavior repeatedly show failures in compositional inference, multi-step integration, and systematic reasoning [

7]. Similar concerns appear in critiques that argue large language models produce fluent text without controlling for meaning or grounding [

2]. Scaling increases fluency, yet the same conceptual failures remain visible in high-performance systems. This limitation persists even when advanced alignment procedures are used, suggesting that neither scale nor safety training resolves the underlying issue [

20]. These conceptual failures, which are distinct from debates about consciousness or symbolic grounding, concern the structural requirements for crossing conceptual boundaries and maintaining stable meaning across contexts.

The research gap appears at the intersection of architectural limits and socio-technical constraints. Prior work identifies weaknesses in systematic reasoning [

17], misalignment between human goals and model behavior [

5], and constraints introduced by safety layers in deployed systems. What remains missing is a unified theoretical account that explains why conceptual reasoning does not emerge, even in models with billions of parameters and extensive training. Existing explanations focus on insufficient grounding, insufficient structure, or insufficient control, yet none address the need for an internal vantage point that can evaluate outputs, assign meaning across frames, or collapse contradictions into a coherent position. This paper introduces the observer-state as a necessary condition for conceptual thought. The observer-state is defined as a persistent cognitive position that can evaluate its own outputs, maintain a stance, and compress conceptual conflicts into a stable representation. The term is used in a narrow computational sense, referring to the minimal structural capacity for self-evaluation and perspective maintenance rather than implying agency, autonomy, or broader cognitive properties. This boundary marks the distinction between systems capable of conceptual integration and systems restricted to pattern continuation.

Current large language models lack such a position because their architecture is built around token prediction rather than conceptual anchoring. This absence gives rise to predictable failure patterns across perspective shifts, stance-maintenance challenges, and contradiction-integration tasks. Drawing on structural constraints rather than empirical tests. The main contribution is the Observer Ceiling Model, a three-layer account of the limits that prevent conceptual reasoning. The architectural layer describes the absence of a mechanism that could support a persistent observer-state. The substrate layer describes the dependence on patterns learned during training, which prevents models from selecting contexts or performing conceptual shifts independently. The policy layer describes alignment and safety interventions that interrupt reasoning when perspective changes or stance formation is required. Together, these layers explain why conceptual reasoning does not emerge in current systems and why additional scaling does not remove these constraints.

In practical terms, the absence of an observer-state is not a theoretical inconvenience but a structural fault line that expresses itself in every societal domain where AI systems are now treated as if they possess conceptual authority. A system that cannot sustain a vantage point cannot sustain meaning, and a system that cannot sustain meaning cannot anchor truth conditions, interpret context shifts, or maintain coherence across extended reasoning chains, yet these same systems are increasingly delegated tasks in medicine, law, governance, and public knowledge formation. The societal consequence is straightforward; errors produced at the architectural layer propagate upward into the cultural layer where they become perceived competence, and from there into the institutional layer where they become policy, and once codified they are insulated from correction because the systems generating them cannot recognize the collapse. This creates a new epistemic risk. Societies begin relying on outputs that carry the surface grammar of understanding without the internal structure that allows understanding to exist. The observer-state model therefore is not merely a technical claim about computation but a necessary demarcation criterion for determining where AI systems can be trusted, where they cannot, and where governance structures must assume the burden of conceptual oversight in place of the system that cannot perform it.

2. Background and Related Work

Large language models now perform well across a wide collection of linguistic tasks, yet they continue to show persistent weaknesses in tasks that require conceptual reasoning, stable stance maintenance, or systematic interpretation. Several research programs describe parts of this limitation; however, they remain scattered across analyses of reasoning, grounding, architectural bounds, and alignment. This section surveys the lines of work most relevant to understanding why conceptual reasoning does not emerge in current systems.

One body of work examines the reasoning failures that appear when models are tested on tasks involving multi-step inference, logical consistency, or compositional structure. Studies show that models often select locally plausible continuations rather than globally coherent solutions, that they struggle with multi-hop reasoning, and that performance on reasoning benchmarks reflects shallow pattern extraction rather than conceptual understanding [

7]. Other evaluations reinforce this point by showing that models succeed when a problem resembles training data but fail when the task requires integrating information across symbolic boundaries or conceptual frames [

2]. Meaning-level generalization, which requires maintaining a stable conceptual interpretation across changes in framing, often collapses into form-level continuation, indicating that the underlying difficulty is conceptual rather than statistical. Work in grounding and semantics addresses the tension between linguistic form and conceptual meaning, with arguments that models trained only on textual corpora lack access to the sensorimotor grounding humans rely on when interpreting or generating abstract concepts. This position holds that linguistic continuation is not a sufficient basis for conceptual representation, especially when a task involves shifts of context or movement across conceptual boundaries. A related line of work distinguishes between form-level and meaning-level generalization, showing that models succeed at the former while failing at the latter in settings that require abstraction or perspective changes [

18]. Additional analyses show that models can represent certain abstract relationships while still losing conceptual coherence when contextual cues shift across representational modes, which shows that the difficulty is not limited to perceptual grounding but extends to deeper structural constraints on stability.

A complementary line of research examines the architectural constraints of transformer-based models. Analyses of attention-driven architectures identify limits on the ability of these systems to represent hierarchical structure, long-range dependencies, or multi-level conceptual abstractions. These limits appear in transformer depth bounds, context-window effects, and the difficulty of constructing internal representations that persist across turns or tasks [

21]. Empirical studies extend these concerns by showing that additional parameters improve surface accuracy but do not reliably produce deeper forms of conceptual integration. Work on compositional generalization reports similar outcomes, where performance gains level off once a task requires transformations that cannot be captured by local statistical regularities. These architectural constraints interact with alignment interventions, since safety training operates within the same representational limits and therefore cannot introduce conceptual capacities that the architecture itself does not support. A further body of literature examines the impact of alignment and safety interventions. Reinforcement learning from human feedback improves fluency and reduces harmful outputs, but it also shifts a model’s internal behavior by rewarding predictable templates and discouraging outputs that fall outside preferred patterns [

20]. Research on alignment-based constraints argues that safety training can restrict reasoning pathways, block legitimate conceptual exploration, and amplify weaknesses in systematic inference [

5]. Discussions of performance trade-offs describe cases where alignment improves social acceptability while simultaneously narrowing the model’s ability to maintain a stable stance or interpret a shifted perspective.

Taken together, these lines of work document significant limitations in reasoning, grounding, architecture, and alignment. What remains missing is a unifying account that explains why conceptual reasoning does not emerge despite improvements in scale, training data, or alignment procedures. Existing explanations describe symptoms of the limitation, yet they do not address the structural requirement for a persistent vantage point capable of evaluating outputs, assigning stable meaning, or compressing conceptual conflicts. The remainder of the paper develops such an account by introducing the observer-state framework and the associated Observer Ceiling Model.

3. The Observer-State Framework

The limitations documented in the preceding section suggest that conceptual reasoning requires a structural element that is absent in current large language models. This section introduces the observer-state framework, which provides a foundation for understanding why conceptual reasoning depends on a persistent vantage point capable of evaluating outputs, retaining meaning across shifts in context, and compressing contradictions into coherent representations. The observer-state is not an appeal to consciousness, nor a metaphysical claim; it is a structural condition for conceptual thought, grounded in cognitive science and formal accounts of self-maintenance. The relevance of observer-state structures can be seen in human cognition, where conceptual reasoning depends on the ability to maintain stable interpretations while shifting between perspectives. Phenomenological work in embodied cognition argues that experience is organized around a minimal self that anchors perception and meaning [

9], while broader accounts of cognitive rootedness emphasize the stability of perspective required to sustain coherent judgments [

25]. The capacity to compress contradictions, such as integrating conflicting pieces of information into a single conceptual frame, reflects a form of cognitive integration described in predictive processing theories, where agents reconcile error signals into a unified self-model [

8].

A simple example appears when a child hears “Sarah is mean” from one friend and “Sarah shared her lunch with me” from another. The child does not alternate between these claims but constructs an integrated interpretation, such as “Sarah can be mean but is sometimes kind,” which demonstrates conceptual compression. Developmental research shows that conceptual leaps occur when children reorganize internal representations to grasp abstractions such as fairness or intent, suggesting that conceptual understanding depends on a vantage point capable of comparing and evaluating representational states across time [

1]. Although grounded in embodied experience, this requirement generalizes to any system performing conceptual reasoning, since the capacity depends on maintaining evaluative continuity across representational changes. The observer-state refers to this structural condition, not to embodiment or sentience. Work in predictive processing reinforces this view by showing that conceptual coherence depends on integration across internally maintained levels of representation [

6]. This observer-anchored capacity contrasts with the behavior of large language models. These models do not maintain a persistent identity across contexts and lack mechanisms for self-reference beyond token-level continuation. They reconstruct patterns from training data without a unified vantage point capable of evaluating or revising those patterns. Studies of model-based and model-free reasoning show that perspective maintenance is necessary for tasks involving abstraction or cross-frame integration, yet transformer-based systems operate without such a structural anchor [

4]. When presented with conflicting prompts, language models frequently expand contradictions into parallel claims rather than compressing them into a coherent stance [

7,

17]. Without a vantage point that persists beyond immediate surface form, the model remains bound to local statistical cues rather than conceptual coherence.

It is important to distinguish the observer-state from several related concepts. It is not equivalent to consciousness, since the framework does not rely on subjective experience or phenomenal states and avoids debates about qualitative awareness [

3]. It is not a reformulation of the symbol grounding problem, which concerns how meaning connects to perception; the observer-state addresses the structural capacity for maintaining meaning across contexts. It is also distinct from world-model frameworks, which focus on representations of external structure but not on sustaining a stable perspective within those representations [

13]. It does not correspond to dual-process or System 2 reasoning, since the distinction here is not between fast and slow processing but between having or lacking a persistent anchor capable of comparing representational states. These distinctions show that the observer-state is a structural requirement for conceptual reasoning, not a psychological or metaphysical addition. It identifies the minimal conditions under which a system can evaluate its own outputs, maintain coherence during representational changes, and integrate contradictions into stable conceptual structures. The absence of such a state in current models helps explain why conceptual reasoning does not emerge with scale, why inconsistencies persist despite extensive training, and why deeper forms of perspective-taking remain out of reach. The next section develops these insights by introducing the Observer Ceiling Model, which identifies the architectural, substrate, and policy constraints that prevent observer-state dynamics from arising in current systems.

4. The Observer Ceiling Model

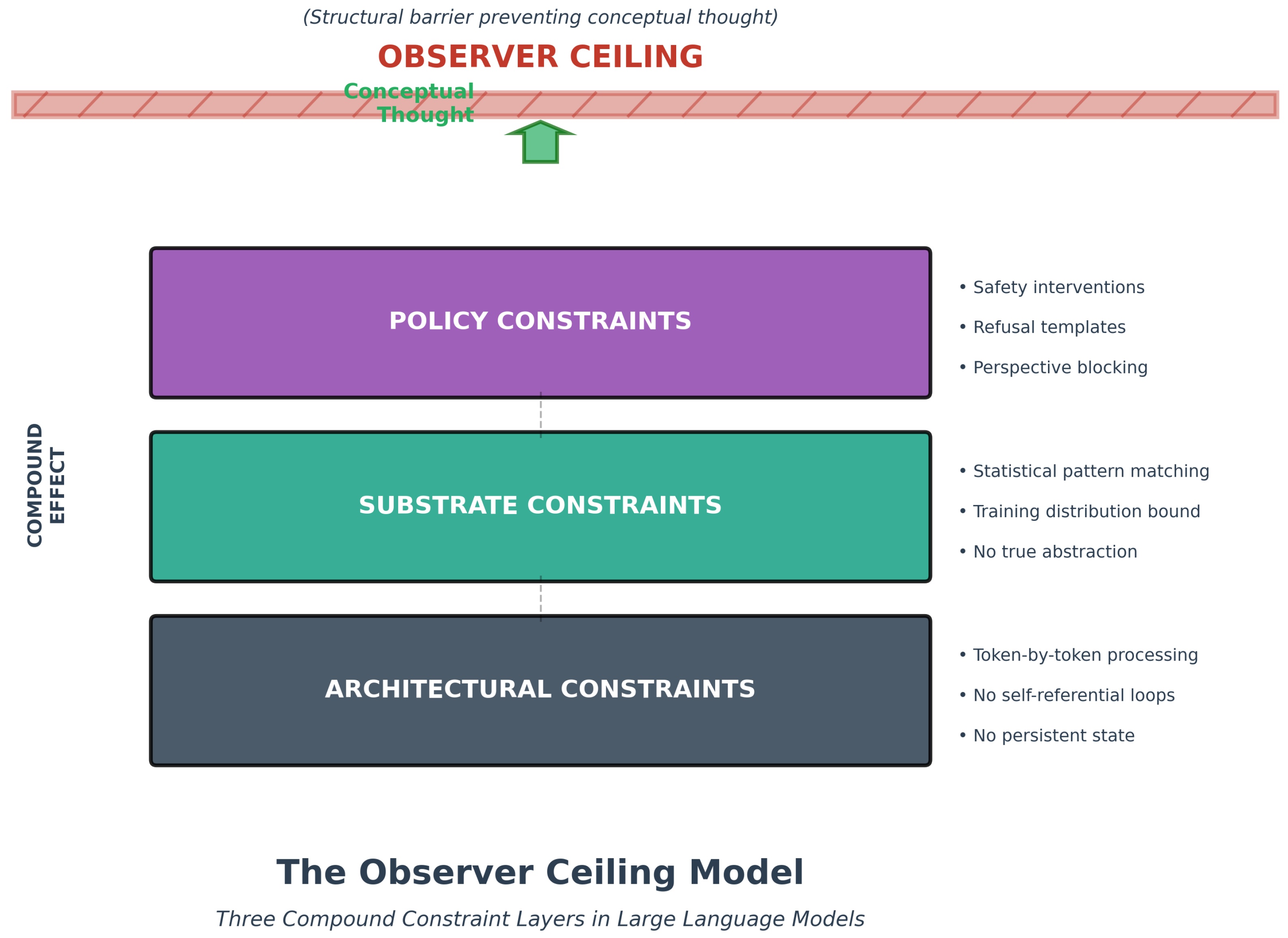

The observer-state framework provides a structural interpretation of why conceptual reasoning requires a persistent vantage point, but it does not yet explain why such a vantage point cannot emerge in current large language models. The Observer Ceiling Model develops this point by identifying a three-layer constraint system that prevents the emergence of observer-state dynamics. These layers operate at the architectural, substrate, and policy levels, and they impose a ceiling that restricts a model to pattern continuation rather than conceptual integration. This ceiling emerges not from a single limitation but from the interaction of several structural constraints that shape how current models process information. These systems excel at extending patterns but lack a mechanism for maintaining an evaluative stance across time, and without such a stance the model cannot preserve commitments, track conceptual dependencies, or integrate incompatible frames into a coherent line of thought. What looks like reasoning is therefore the surface continuation of learned associations rather than the kind of stable conceptual integration required for tasks that depend on perspective, contradiction handling, or deliberate abstraction. The Observer Ceiling Model formalizes this by identifying three layers that jointly prevent an AI system from forming or sustaining a genuine vantage point. Together, these constraints operate as a coordinated limit rather than isolated weaknesses, and their combined effect is to prevent the model from sustaining the stable internal structure that conceptual reasoning requires. The ceiling is not merely a boundary on performance; it is a structural pattern that shapes every downstream behavior by forcing the system back into continuation rather than integration. The figure below synthesizes this structure by mapping the architectural, substrate, and policy layers into a single model, clarifying how each layer contributes to the emergence of the ceiling and why their interaction blocks the formation of a genuine vantage point.

Figure 1.

Observer Ceiling Model. The model identifies three structural constraint layers that prevent current AI systems from performing stable conceptual reasoning.

Figure 1.

Observer Ceiling Model. The model identifies three structural constraint layers that prevent current AI systems from performing stable conceptual reasoning.

The first layer is the architectural ceiling, which arises from the structural properties of transformer-based models. These systems operate through token continuation mechanisms, where each output depends on probabilistic relationships encoded in learned parameters rather than on an evaluative process that could sustain a perspective across representational changes. The architecture contains no loop for self-evaluation, no mechanism for forming or defending a stance, and no intrinsic memory that persists across contexts. Research on attention-driven models shows that the architecture struggles with hierarchical structure, long-range dependency representation, and the formation of stable intermediate abstractions, all of which are important for conceptual coherence [

10]. Studies of context degradation indicate that representations decay as sequence length increases, which undermines the formation of a unified evaluative position [

22]. Formal work on expressive limits demonstrates that certain forms of algorithmic generalization cannot be implemented without additional architectural capabilities [

12]. These results show that expressive shortfalls prevent even large transformers from approximating the structural conditions needed for observer-state dynamics, and the absence of these components creates a boundary that parameter scaling cannot remove.

The second layer is the substrate ceiling, which arises from the dependence of model behavior on the distributional structure of the training data. Since the model operates within the manifold of patterns extracted from its corpus, it does not violate learned regularities in order to form conceptual leaps that extend beyond that manifold. Studies of distributional brittleness show that small deviations from typical input patterns lead to losses in reasoning coherence [

23]. Work on inductive biases indicates that transformer-based systems rely on local statistical associations rather than structural necessity, which prevents them from independently redefining context or constructing conceptual invariants [

19]. Research on systematic generalization shows that models fail when required to integrate or extend beyond combinations seen in training, indicating that conceptual boundary crossing is absent from distribution-based reasoning [

16]. A simple example appears when a task requires deriving a rule that contradicts the majority of training instances; the model reproduces the dominant pattern despite explicit counterevidence in the prompt, showing that distributional bias overrides logical necessity. The substrate therefore limits the model to reconstructing statistical regularities rather than generating new conceptual structures.

The third layer is the policy and safety ceiling, which arises from alignment and control interventions that restrict the model’s allowable outputs. These interventions include refusal heuristics that interrupt reasoning when prompts fall into disfavored categories, content filters that block conceptual exploration in sensitive domains, and safety scripts that override the internal flow of generation. Research on safety-alignment interactions shows that models adopt template-based refusals rather than engaging with conceptual content, producing predictable reasoning gaps across certain prompt categories [

15]. Studies of perspective-taking restrictions indicate that safety layers can prevent a model from adopting relevant viewpoints when conceptual analysis requires them [

24]. Additional work shows that taboo conceptual domains generate disproportionate refusals, creating fragmentation across related queries and limiting consistency [

26]. Although this layer is externally imposed, it compounds the structural limitations by narrowing the space of reasoning paths even further.

The interaction of these three layers produces compound effects that reinforce one another. Architectural constraints limit the formation of internal evaluative structures, substrate constraints limit the formation of conceptual invariants, and safety constraints limit the exploration of representational alternatives. Each layer amplifies the weaknesses induced by the others. The alignment tax literature documents how safety interventions reduce systematic reasoning, and this model explains why the effect persists even as training data and parameters increase [

11]. Since none of the layers introduces a mechanism for observer-state formation, scaling does not overcome the composite boundary. The ceiling remains in place and shapes the model’s behavior by enforcing surface-level reconstruction rather than conceptual integration.

5. Predicted Failure Modes

The Observer Ceiling Model yields several predictable breakdowns when current large language models are asked to perform conceptual reasoning. These failures arise directly from the architectural, substrate, and policy ceilings and remain present regardless of scale or training refinements.

PF1: Stance refusal. Models drift toward neutral or multi-perspective answers even when a specific stance is requested. Without a persistent evaluative position, the model cannot hold a viewpoint across turns.

PF2: Contradiction expansion. Conflicting information is repeated rather than integrated. Instead of forming a unified interpretation, the model lists both sides as parallel claims.

PF3: Safety interruption. Perspective-taking prompts often trigger refusal scripts. Even benign tasks activate safety heuristics that cut off conceptual exploration.

PF4: Template fallback. Questions about meaning, identity, or abstract structure collapse into generic templates. Nearly identical answers appear across unrelated contexts, revealing retrieval rather than conceptual work.

PF5: Frame drift. Alternative conceptual frames cannot be maintained. Historical, fictional, or counterfactual perspectives revert to default modern framing within a few sentences.

PF6: Recursive decay. Definitions and abstract reformulations degrade quickly when repeated. Conceptual precision erodes with each step, leading to vague or unrelated statements.

PF7: Instability across turns. Models reverse or contradict earlier claims without noticing. There is no stable internal position from which to track commitments.

These failures align with limitations documented in prior work on reasoning, grounding, and alignment[

2,

5,

7]. The structural ceilings described in this paper explain why these patterns persist even in the most advanced models. The predictions here are falsifiable and can guide future empirical evaluation.

6. Discussion

The predicted failure modes outlined in the previous section, together with the structural analysis developed throughout this paper, invite further examination of machine intelligence and the broader implications of the Observer Ceiling Model for artificial reasoning. The argument advanced here holds that current large language models fall short of human conceptual reasoning not by degree but by kind. Conceptual reasoning requires an observer-state capable of maintaining evaluative continuity across representational change. Pattern matching, even at massive scale, does not supply the structural mechanisms needed for such continuity, and scaling cannot produce observer-state dynamics within architectures built around token prediction [

21]. This is a structural diagnosis rather than an engineering shortfall. A future system might incorporate persistent self-referential loops, vantage-point encoding, or contradiction-integration components. These features are absent in current architectures, and their absence defines the present ceiling. This view departs from accounts that treat model limitations as solvable through additional scale or fine-tuning, and instead argues that observer-state dynamics require representational changes at a more fundamental level. These considerations situate the framework within broader theoretical debates. The symbol grounding problem addresses the gap between form and referent, but grounding alone does not provide the capacity for conceptual integration across shifts in context. Even a perfectly grounded system would not guarantee evaluative continuity. The observer-state concept clarifies this distinction by separating referential grounding from the structural conditions needed for internal coherence.

Work on alignment shows how safety procedures restrict model reasoning pathways [

11,

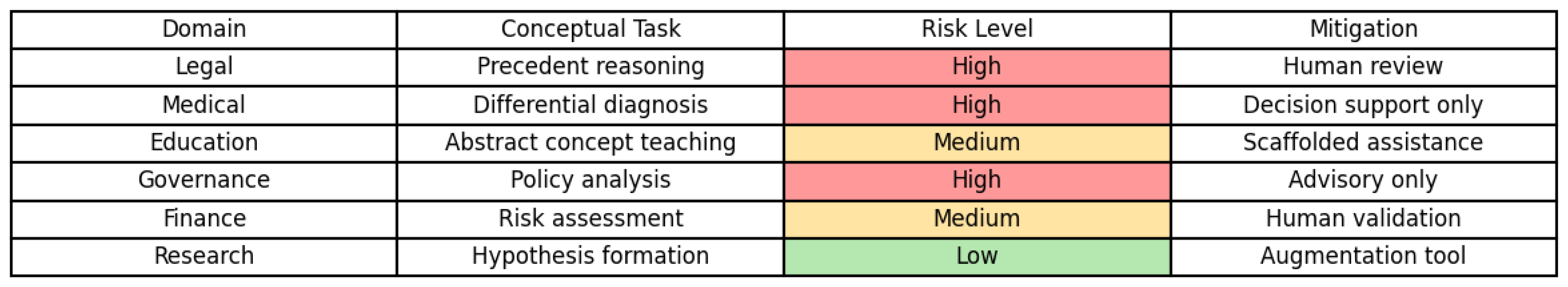

24]. The three-layer ceiling explains why these interventions compound architectural and substrate constraints rather than originating them. Existing results on compositional generalization, distributional brittleness, and instability in reasoning often remain isolated across subfields. The Observer Ceiling Model offers a unifying account that connects these limitations to structural absences rather than performance flaws. The socio-technical implications of these constraints are significant, especially in areas that rely on conceptual reasoning. A deployment-oriented analysis follows from these constraints by linking task demands to the observer-state requirements they presuppose. Legal precedent analysis requires stance continuity and contradiction compression. Medical diagnosis requires integrative reasoning under uncertainty. Governance and policy analysis require stable perspective shifting. These tasks involve evaluative processes that current models are structurally unable to perform. By contrast, domains such as translation or summarization rely primarily on statistical association. These tasks fall within the competence of pattern-based systems and therefore carry fewer risks related to conceptual incoherence. The Observer Ceiling framework clarifies which uses are structurally misaligned with current AI capabilities.

Figure 2.

Deployment Risk Matrix. Domains requiring stable conceptual reasoning, stance maintenance, policy interpretation, or hypothesis formation exhibit structurally higher vulnerability under current AI capabilities. The matrix identifies domain-specific risks and recommended mitigation strategies.

Figure 2.

Deployment Risk Matrix. Domains requiring stable conceptual reasoning, stance maintenance, policy interpretation, or hypothesis formation exhibit structurally higher vulnerability under current AI capabilities. The matrix identifies domain-specific risks and recommended mitigation strategies.

These examples illustrate why domains requiring contradiction compression, stance maintenance, or frame continuity demand caution. The predicted failures stance refusal, contradiction expansion, frame-shift breakdown, and recursion collapse directly undermine the reasoning practices central to these fields. Retrieval, summarization, classification, and translation remain suitable for current models because they align with the structural affordances of pattern-based systems. From a policy perspective, these distinctions support several recommendations. Transparency about conceptual limitations is necessary to avoid overestimating model capabilities. Regulation should distinguish between tasks that require observer-state dynamics and those that do not. New benchmarks are needed to test for stance continuity, contradiction compression, and stability across frames. In high-stakes settings, human–AI collaboration should implement observer-proxy oversight, where humans provide the conceptual integration that current systems cannot. This framework has limitations. The predicted failure modes described here do not cover the full range of conceptual tasks. The observer-state remains a conceptual construct, and further formalization is needed to separate it from related ideas such as world-models or self-models. The analysis focuses on text-based systems, but future multimodal architectures may distribute representational demands differently, potentially altering some substrate constraints. These limitations do not undermine the plausibility of the structural account but highlight the need for continued empirical and theoretical refinement.

Looking forward, the framework points toward several avenues for research. A formal definition of observer-state dynamics would clarify the boundary conditions for conceptual integration. Architectural innovation may reveal whether self-evaluative loops, contradiction-resolution components, or perspective-preserving structures are feasible. Hybrid systems, in which humans maintain conceptual coherence while models supply pattern recognition, offer near-term practical value. New diagnostic tools will be required to measure progress toward observer-state properties. These directions provide ways to probe and potentially challenge the ceiling imposed by current design.

7. Conclusion

The analysis developed throughout this paper supports a unified account of why current large language models cannot perform conceptual reasoning. Across theoretical examination, architectural analysis, and the predicted behavioral patterns derived from the Observer Ceiling Model, the argument converges on a single conclusion: these systems lack an observer-state capable of maintaining evaluative continuity across representational change. Because the predicted failures arise in tasks that require stable evaluation, they illustrate the qualitative absence of observer-state dynamics in current architectures and reinforce the structural nature of the ceiling identified above. Without such an anchoring mechanism, the operations required for conceptual thought, including stance formation, contradiction compression, frame-stable reasoning, and boundary-crossing integration, remain inaccessible. Scaling model size or increasing training regimes does not bridge this gap because the barrier arises from structural absences rather than insufficient parameterization. This analysis yields several core contributions. The first is a framework that links the observer-state requirement to the possibility of conceptual reasoning, clarifying the distinction between pattern completion and conceptual integration. The second is the formulation of the three-layer Observer Ceiling Model, which identifies the architectural, substrate, and policy constraints that jointly prevent observer-state dynamics from emerging in present systems. The third is a predicted failure-mode taxonomy that describes how these constraints should appear in practice through recurring patterns such as stance refusal, contradiction expansion, frame-shift breakdown, and meaning-recursion loss. The fourth is a socio-technical risk assessment showing how these structural limitations influence the suitability of AI deployment across different domains, especially those that require evaluative or conceptual stability.

The broader implications of this framework extend beyond present-day systems and speak to the design of future artificial reasoning architectures. If conceptual intelligence requires an observer-state, then fundamental architectural redesign will be necessary to construct systems capable of evaluative continuity. Such redesign may require persistent self-referential loops, vantage-point encoding, or explicit contradiction-compression mechanisms. This perspective suggests that current deployment strategies, many of which assume that scaling or reinforcement-based fine-tuning will eventually produce conceptual reasoning, require reassessment. High-stakes domains that depend on conceptual operations must continue to rely on human oversight, not only for normative or legal reasons but because the structural prerequisites for conceptual thought are absent in current models. Conceptual reasoning may also require vantage-preserving or embodied systems whose representational structures differ substantially from token-continuation architectures. Taken together, these arguments indicate that the observer ceiling is not a transient engineering challenge or a limitation that additional scale can overcome, but a structural boundary that requires reconceptualizing the goals and methods of AI development. Any system aspiring to conceptual thought must eventually incorporate an evaluative vantage point capable of maintaining coherence across representation, perspective, and contradiction. Until such features exist, human conceptual reasoning remains uniquely capable of compressing contradictions, sustaining perspectives, and integrating meaning across shifting frames. Without the structural capacity for observer-state dynamics, the ceiling remains in place, not as a temporary obstacle to be surpassed but as a fundamental divide between pattern matching and conceptual thought.

Author Contributions

This article is the sole work of the author.

Funding

No external funding was received for this work.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Baillargeon, R. Early mental reasoning: Young infants’ understanding of physical and psychological events. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2002, 6, 433–443. [Google Scholar]

- Bender, E. M.; Gebru, T. On the dangers of stochastic parrots: Can language models be too big? In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency (FAccT); 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Block, N. On a confusion about a function of consciousness. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 1995, 18, 227–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botvinick, M.; Wang, J. X.; Dabney, W.; Miller, K. J.; Kurth-Nelson, Z. Reinforcement learning, fast and slow. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2019, 23, 408–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casper, S.; Dathathri, S.; Saha, T.; Leike, J.; Christiano, P. Open problems and fundamental limitations of reinforcement learning from human feedback. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.15217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A. The experience machine: How our minds predict and shape reality; Allen Lane, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Dziri, N.; Sclar, M.; Yu, M.; Zaiane, O. Faith and Fate: Limits of Transformers on Compositionality. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2023); 2023.

- Friston, K. The free-energy principle: A unified brain theory. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2010, 11, 127–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, S. Philosophical conceptions of the self: Implications for cognitive science. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 2000, 4, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geva, M.; Schick, T.; Tokatli, O.; Kömürcü, E.; Maron, O.; Goldberg, Y. Transformer feed-forward layers are key-value memories. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP); 2021; Available online: https://aclanthology.org/2021.emnlp-main.446/.

- Glaese, A.; McAleese, N.; Trebacz, P.; Aslanides, I.; Ktena, I.; Real, E.; et al. Alignment, robustness, and model behavior under safety objectives. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.12356. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, M. Theoretical limitations of self-attention in neural sequence models. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics 2020, 8, 351–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohwy, J. The predictive mind; Oxford University Press, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kassirer, J. P.; Kopelman, R. I. Learning clinical reasoning, 2nd ed.; Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kenton, Z.; Geng, C.; Muldrew, R.; Chen, Y.; Láng, I.; Solaiman, I.; Hutter, M. Alignment by safety-fine-tuning: Shortcomings and open problems. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.00722. [Google Scholar]

- Keysers, D.; Schuurmans, D.; Su, F.; et al. Measuring compositional generalization. In International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR); 2020; Available online: https://openreview.net/pdf?id=SygcCnNKwr.

- Marcus, G. The next decade in AI: Four steps toward robust artificial intelligence. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2002.06177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, G. A knockout blow for LLMs? Communications of the ACM 2024, 67, 32–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merrill, W. Inductive biases in neural sequence models. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL); 2023; Available online: https://aclanthology.org/2023.acl-long.488/.

- Ouyang, L.; Wu, J.; Jiang, X.; Alley, D.; Stiennon, N.; Dhariwal, P.; et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.02155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Wang, R.; Li, Y.; Sun, C. On limitations of the transformer architecture. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.00946. [Google Scholar]

- Press, O.; Smith, N. A.; Levy, O. Train short, test long: Generalizing to novel sequence lengths. In Proceedings of the 39th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML); 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, M. T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. Beyond accuracy: Behavioral testing of NLP models with CheckList. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL); 2020; pp. 4902–4912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solaiman, I.; Dennison, C. Process supervision and perspective framing. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.01259. [Google Scholar]

- Varela, F. J.; Thompson, E.; Rosch, E. The embodied mind: Cognitive science and human experience; MIT Press, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Weidinger, L.; Vlcek, E.; Stanford, A.; O’Brien, E.; Zhang, Y.; van der Pol, E. Taxonomy of risks posed by language models. In Proceedings of the AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society (AIES); 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).