1. Introduction

Modern LLMs increasingly integrate with external tools, functions, and MCP servers [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7], enabling them to perform complex reasoning and actions beyond text generation. Through tool calling, also known as function calling, LLM agents can invoke APIs, MCP servers, or other agents to access data, perform computations, and take action on behalf of users. These capabilities enable complex workflows such as financial analysis, coding assistance, and autonomous system management. However, as the number of available tools and agents grows, a fundamental challenge emerges regarding how an LLM can effectively select the right tool or agent at the right time.

This challenge, referred to as tool selection, extends beyond reasoning or planning. It involves both scalability, meaning the ability to handle hundreds or thousands of tools, and reliability, meaning accurate, authorized, and interpretable actions. In production environments, these issues are amplified by constraints such as API tool limits imposed by model providers, user-level authorization, latency, and system-level monitoring. Despite growing industrial adoption, academic literature still lags behind. Existing work on tool learning focuses primarily on controlled or small-scale experiments and fails to capture the architectural and operational nuances of production-grade systems [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

At the same time, recent advances including reasoning-centered models, hosted protocols like MCP, and agent-as-a-tool multi-agent systems [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17] are redefining what tool selection means in practice. These developments have introduced new dimensions such as retrieval-based tool scaling, multi-turn context management, human-in-the-loop orchestration, and memory-assisted tool persistence [

18]. Yet, a systematic understanding of these mechanisms and their interplay in production settings remains lacking.

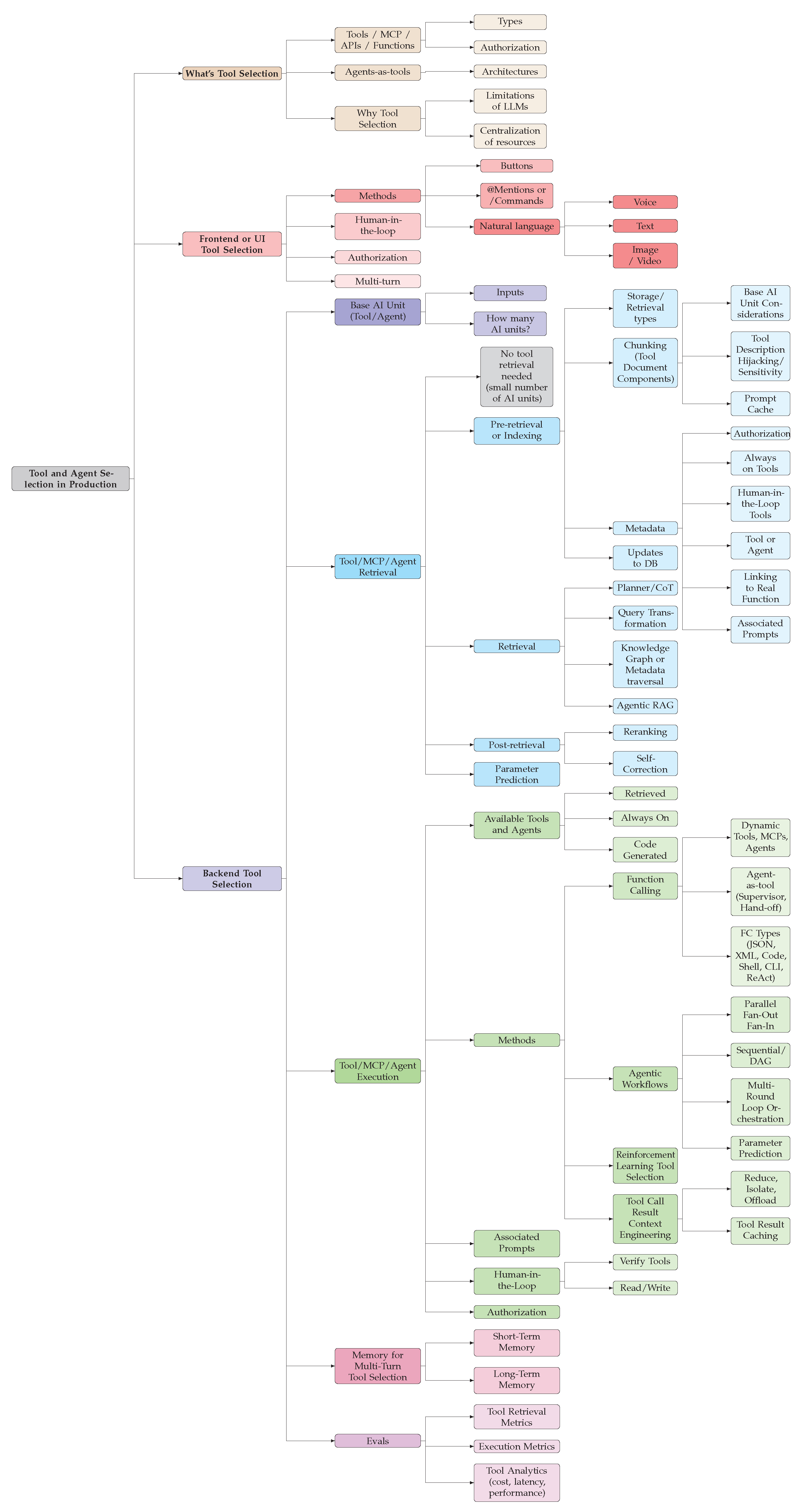

Figure 1.

High-level overview of tool selection across introduction, frontend, and backend components.

Figure 1.

High-level overview of tool selection across introduction, frontend, and backend components.

This paper aims to close that gap by presenting the first comprehensive production-oriented framework of tool and agent selection from a production perspective. We distinguish between the frontend layer, where users interact with agents through buttons, slash commands, or natural language, and the backend layer, where retrieval, execution, orchestration, and memory enable scalable reasoning. The paper contributes in three ways.

Comprehensive Taxonomy. A unified taxonomy of modern tool and agent selection approaches spanning manual, UI-driven, retrieval-based, autonomous selection, tools, subagents, and MCPs.

Production-Oriented Framework. An analysis of how real-world systems integrate agent and tool retrieval, execution, short-term and long-term memory, authentication, authorization, and human-in-the-loop pipelines to achieve scalable and secure agentic behavior.

Evaluation and Open Challenges. A synthesis of evaluation methods for agent and tool retrieval and execution accuracy, cost, and latency, along with future research directions.

2. Overview of Tool Selection

Tool selection refers to the process by which LLMs identify, select, and iteratively use one or more external functions, tools, or agents to complete a task. As illustrated in

Figure 2, a user begins with a frontend interaction, such as pressing a button or providing a natural language query, which the backend interprets to determine the set of available base AI units

and their total count

. When this set is small, the model can directly access all units. However, as the number of tools and agents grows, retrieval mechanisms are needed. The backend then applies indexing, retrieval, and post-retrieval ranking strategies, drawing on retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) techniques to select the most relevant functions from a knowledge base [

8,

9,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. The retrieved, always-on, or code-generated tools are executed using backend orchestration methods such as native function calling, python-, shell-, cli-, parallel or DAG-based workflows [

4,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31], depending on system configuration. Throughout this process, contextual considerations including authentication, authorization, human-in-the-loop verification, parameter prediction, and associated prompts remain active from retrieval through execution [

3,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36]. After producing the final response, the backend updates both short-term and long-term memory to capture conversation context and tool usage history [

18,

37]. Evaluation then considers retrieval and execution accuracy, as well as operational analytics such as cost, latency, and the number of tools or agents invoked, providing a complete view of production-scale tool and agent selection.

2.1. Tools, MCPs, APIs, or Functions

Recent innovations in tool calling have blurred the boundaries among tools, MCP servers, APIs, functions, and agents. In essence, function or tool calling extends an LLM’s capabilities by granting access to external functions and data beyond its training corpus. Although functions traditionally represent simple read or write operations, any abstracted capability, whether a computation, API endpoint, or service call, can be exposed to an LLM as a tool. Within native tool-calling frameworks, these entities share a common structure: a JSON-, code-, or command-line-interface (CLI)-formatted function schema attached to the model provider’s API call (

Figure 2). The distinction lies primarily in intent and context. APIs are typically designed for human developers to invoke explicitly, while tools are optimized for agents that autonomously decide when and how to use them based on their name, description, and parameter schema. MCP tools, in particular, standardize this interface by defining reusable, interoperable tool specifications that can be hosted remotely or run locally [

1,

2,

38,

39]. Regardless of implementation, the structured function definition remains the fundamental mechanism through which an LLM perceives available actions and determines their execution order.

Figure 3.

Natural language-based tool selection where a user can ask anything to the LLM agent.

Figure 3.

Natural language-based tool selection where a user can ask anything to the LLM agent.

2.1.1. Types and Categories of Tools

LLM-integrated tools fall into three types:

local or custom tools,

MCP or hosted tools, and

managed or built-in tools. Local or custom tools are functions defined within a local repository for specific applications [

9,

10]. These local or custom tools commonly are JSON-based native function calling, XML-based, shell-based, python-based, cli-based, MCP or hosted tools, accessible through standardized protocols such as the Model Context Protocol (MCP), enable shared, reusable functionality across systems [

1,

26]. Managed or built-in tools are provided directly by model providers or frameworks and often include utilities like web search, code execution, or file operations [

2,

3]. Functionally, tools can be grouped into two categories within the CRUD (create, read, update, delete) spectrum:

read tools and

write tools. Read tools retrieve or query data without modifying the environment, while write tools perform actions that create, update, or delete resources [

32,

40,

41]. These distinctions define how tools are executed, authorized, and monitored in production.

2.1.2. Auth Considerations and Human-in-the-Loop

Authentication, authorization, and human-in-the-loop (HITL) controls are essential for managing how users and agents execute tools in production. Authentication verifies user identity, while authorization defines which actions or resources a user is permitted to access [

3,

32,

40,

41]. At the user level, these controls are typically implemented through mechanisms such as JSON Web Tokens or OAuth scopes, ensuring that only authenticated users can access specific tools or MCP servers that match their permissions.

Authorization can also apply to tools and agents themselves. Tool-level authorization governs which operations an individual tool may perform within a given environment, while agent-level authorization determines whether an entire agent is permitted to execute actions or must authenticate independently of the user. This layered structure provides both user-centric and system-centric safeguards that protect against unauthorized access.

HITL mechanisms introduce an additional layer of safety by requiring explicit user confirmation before certain tool actions are executed. Systems can pause to let users approve or modify a pending action based on its risk or effect. Read operations are often allowed automatically, whereas write operations such as creating, updating, or deleting data typically require user approval. These interventions help balance automation with oversight, improving both transparency and control in production settings.

2.2. Agents as Tools

As the number of tools grows, a single agent managing all of them faces scalability and complexity challenges [

8,

9,

10,

20,

42]. Reasoning over many options and dependencies lengthens context and reduces reliability. To mitigate this, systems often adopt the separation-of-concerns principle, assigning each agent a focused domain with a bounded tool set or MCP servers to improve specialization. Agents can exchange information or delegate tasks, enabling collaboration similar to human experts. This structure forms a tool–agent–complexity paradigm [

13,

43,

44,

45], where agents themselves act as callable tools within higher-level systems, supporting modular, scalable, and reusable architectures. Beyond these architectures, emerging frameworks such as Claude Skills modularize agent capabilities into reusable "skills" that can be dynamically loaded or composed within a larger system [

46]. Each skill encapsulates domain-specific workflows, metadata, and tool access patterns, enabling agents to operate with fine-grained specialization while maintaining interoperability across contexts.

2.2.1. Multi-Agent as Tools Architectures

Within this agent-as-tool paradigm, two main multi-agent architectural patterns have emerged. The first is the supervisor–orchestrator architecture [

47], in which a top-level agent coordinates sub-agents exposed as tools. Each sub-agent is treated as a function with defined inputs and outputs, typically requiring a task as input and an answer as output, enabling the orchestrator to decompose tasks and parallelize execution under centralized control. The second primary architecture is the hand-off or network-based model [

11,

48,

49], in which control is transferred from one agent to another. In this model, agents delegate user tasks, passing requests to better-equipped agents given the domain of the question. Recommendations for multi-agent architectures within an agent-as-tool system:

Supervisor architectures are suited for research and reasoning tasks that use parallel execution.

Hand-off architectures are suited for autonomous, domain-isolated agents that do not need heavy orchestration.

2.3. Why Tool Selection

Tool selection is the process by which LLMs choose and invoke the right function from many available tools. Reliable selection stabilizes production systems by separating frontend triggers, such as buttons or @mentions, from backend retrieval mechanisms. It is also key to scalability, as agents are constrained by the number of tools or MCP servers they can access at once. Scaling this agent–tool space requires retrieval-based selection, agent-as-tool abstractions, and user interfaces that let users search for and equip MCPs from large tool pools. Existing work [

50,

51] focus broadly on tool learning and overlook production challenges such as hosted tools, authentication, human oversight, and orchestration. Production-grade tool selection therefore remains an open research problem, requiring deeper analysis of retrieval, scalability, and coordination in real-world systems.

2.3.1. Limitations of LLM Tool Calling

The motivation for robust tool selection arises directly from the limitations of current LLM tool calling.

Context and caching pressure

Long tool outputs and long running agents inflate context window use and cost, while dynamic native function calling resets the prompt cache and increases cost and latency. To avoid these limitations, production systems apply context engineering strategies to reduce, isolate, and offload tool results, while using non-native function calling such as code-, cli-, shell- based strategies [

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60]. See

Section 4.3.

3. Frontend or UI Tool Selection

Frontend or UI tool selection for LLM agents shapes how users can interact with the underlying backend models that perform tool selection. As seen in

Figure 2, users can force agents to use tools, MCPs, or agents-as-tools such as buttons, @mentions, slash commands. Or users can interact with backend systems through natural language, comprising text, voice, image, or video. The theme of auth and human-in-the-loop also has specific frontend or UI-based implications, such as SSO logins or approving tool calls.

3.1. Methods of Frontend or UI Tool Selection

3.1.1. Buttons

Within a chat interface, buttons that select, equip, or force an LLM agent to call a tool enable the predictability and explicitness of an agent’s actions (

Figure 4). Buttons allow for production situations where a user knows which tool an agent should call, rather than offloading the tool selection reasoning to an agent, which can lead to non-deterministic or error-prone behavior. Furthermore, when the number of tools scales beyond reasonable limits, buttons or drop-down menus allow users to select from a large set of tools rather than invoking retrieval systems. Many provider-hosted chat services [

2,

3,

38], independent chat applications [

61], and coding assistants [

62,

63,

64,

65,

66,

67,

68,

69,

70,

71] use buttons to abstract tool selection from the agent to the user.

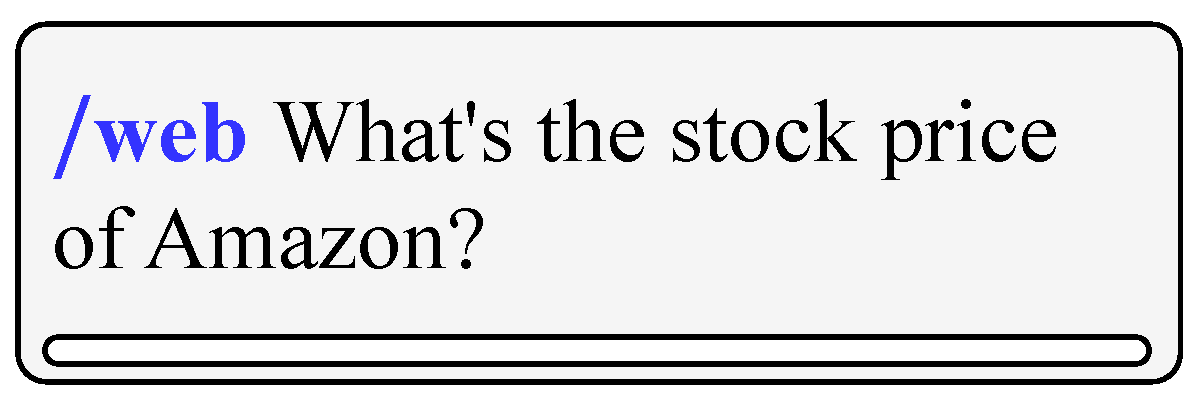

3.1.2. Mentions or Slash Commands

Structured command syntax offers power users precise control over tool invocation (

Figure 5). The @-mention pattern, popularized in collaborative platforms, enables explicit routing to specialized agents or custom GPTs within ChatGPT conversations [

72,

73,

74,

75]. Development-oriented assistants such as Windsurf AI extend this paradigm through slash commands (e.g.,

/explain) and file-specific mentions (e.g.,

@filename.py) to trigger contextual tools (

Figure 6) [

73,

74]. While this approach provides fine-grained control and composability, it also requires users to be familiar with the available commands and their syntax.

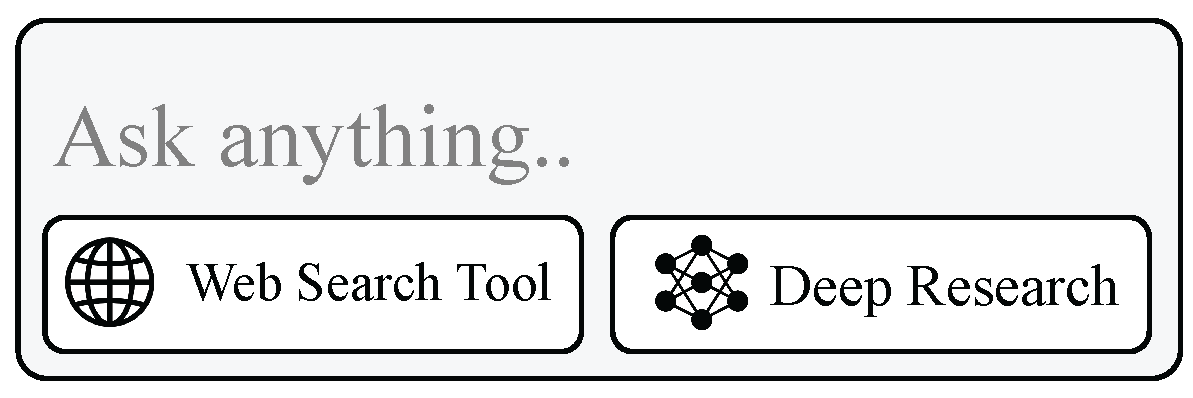

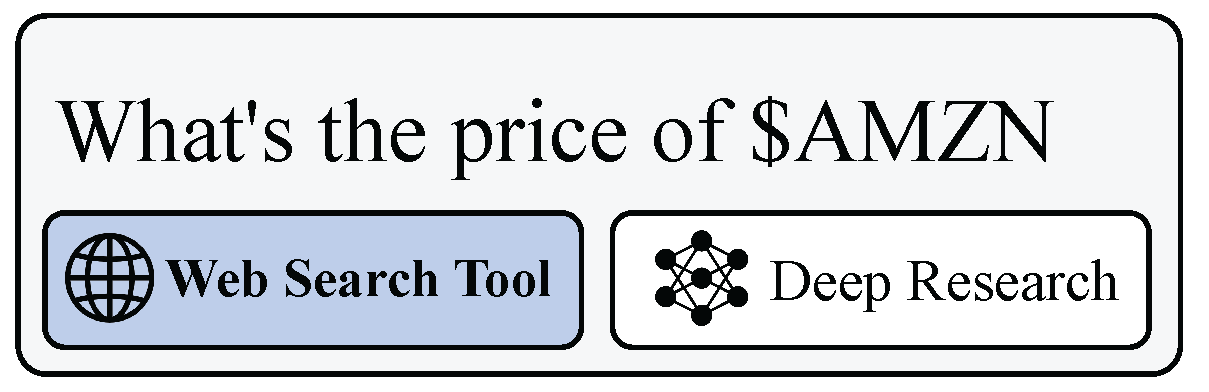

3.1.3. Natural Language

Implicit tool invocation through natural language processing represents the most accessible yet technically challenging approach [

2,

6,

29,

38,

76,

77,

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83,

84,

85,

86,

87,

88]. Backend models must infer both the necessity for tool use and the appropriate tool selection from unstructured user input [

18,

50,

51].

Voice

User voice is a common medium for natural language in production systems, with two primary methods. The first method is transcribing the user’s audio first through a speech-to-text transcription service [

89,

90,

91] and sending the transcribed text to the backend to handle tool selection. The second method is recent advancements in speech-to-speech models [

78,

92,

93] that take an input as speech and can execute tool or MCP calls through speech natively, without a step for transcription service. These recent function calling speech-to-speech models result in decreased latency, simpler architectures, and the ability to scale complexity by using hand-off or supervisor multi-agent architectures.

Text

Traditional text-based natural language involves sending the user’s raw text input to the backend to handle tool selection. Many model providers enable automatic tool selection for models by setting backend parameters such as

tool_choice=auto, which allows the model to call tools only when it determines necessary [

2,

38,

62,

76,

77,

79,

80,

81,

83,

84,

86,

94].

Image and Video

Images and videos can also be used as the input for tool calling. Two methods include 1) traditional OCR or Image parsing to extract text and send to the backend, and 2) native vision language models (vLLMs) that process images and text as inputs and can call tools as output. Similar to function calling speech-to-speech models, vLLMs decrease latency and reduce architecture complexity by handling multimodal inputs natively [

2,

3,

38,

77,

80,

95,

96].

3.2. Human-in-the-Loop in Front End

Human-in-the-loop mechanisms (HITL) are commonly handled in the frontend or UI in the application level through user-confirmation button clicks, pause-and-edit tool calls, or discarding the tool call altogether. For example, coding agents perform many write operations such as adding or deleting files, running commands in the terminal, and more. HITL in the frontend enables the simplest medium for humans to approve, edit, or deny tool selection for AI agents in production [

3,

32,

40,

62,

63,

97].

3.3. Frontend Auth Considerations

AI agents that act upon users often need to have the same permissions as the user. At the user level, authentication can involve logging in to verify identity, while authorization determines whether they are allowed to use the agent, tool, or MCP server [

1,

3,

40,

80,

81,

83]. While frontend or UI auth considerations are primary at the user level, tool-level and agent-level considerations need to surface helpful messages in the frontend if their scopes prevent them selecting a tool. Furthermore, HITL is tightly coupled to auth considerations, where if scopes prevent an agent or tool to be called without a human’s approval, user confirmations can be triggered in the frontend to confirm the action [

32,

62].

3.4. Multi-Turn Front End

Multi-turn tool calling introduces context management challenges related to how many tools the model can access within a session. In frontend interfaces, users can directly select tools, agents, or MCP servers through buttons, @mentions, or slash commands, but UI space limits the number of visible options. Larger systems with hundreds of tools often rely on drop-down menus or search functions, such as BM25 or vector search, to help users locate specific tools. Maintaining continuity across sessions adds complexity, since the backend must manage which tools remain active in short-term context and which are removed. MemTool [

18] addresses this by dynamically adjusting short-term tool memory based on user interactions and natural language inputs.

Long-term memory for multi-turn frontend tool selection tracks a user’s personalized tools and parameters [

98,

99,

100,

101]. In production, interfaces such as buttons or drop-downs can highlight frequently used tools, while sending user context to the backend to improve natural language tool selection and parameter prediction.

4. Backend Tool Selection

Backend tool selection (

Figure 2, steps 3–6) manages how LLM agents retrieve, execute, and orchestrate tools or agents at scale. It also covers supporting mechanisms such as memory, human oversight, authorization, and evaluation that ensure scalable and reliable performance in production systems.

4.1. Base AI Unit (Tool/Agent)

Since any tool, MCP, API, function, or agent can be represented as a function definition for an LLM, it is critical to determine what and how many base AI units

are present. Tools and agents have different requirements for how they are indexed in a tool knowledge base for retrieval [

8,

9], as well as inconsistent input parameters and considerations during execution.

4.1.1. Inputs

Tools, MCPs, and APIs generally include traditional input parameters, similar to functions in programming languages [

102,

103]. Agents, although not formally standardized, typically receive a natural language task as input. Protocols such as the Agent-to-Agent (A2A) framework [

104] and the Agent Communication Protocol (ACP) [

105] describe common formats for agent inputs and exchanges. Developers can also define custom input parameters for agent-as-tool implementations. The inputs provided to a base AI unit determine how tools or agents are executed. When production systems use tools or custom agent-as-tool configurations, native function-calling execution through a supervisor agent generally works as intended. In contrast, when an agentic workflow (

Section 4.3) operates without function calling, such as fan-in, fan-out, or sequential DAG structures, standardized task inputs can be sent to all agents if using A2A. However, when

or when a custom agent-as-tool has non-standard input parameters, an additional layer of parameter prediction (

Section 4.2.4) is required. Therefore, when both tools and agents exist within the same system, input design must align with the chosen execution pattern to ensure consistent and correct behavior in production.

4.1.2. Quantity Considerations

Simply put, LLMs can only handle a finite number of tools, MCPs, or agents-as-tools, before hitting API limitations and model complexity issues [

8,

9,

10,

11,

52]. For example, OpenAI can only send 128 tools before an API error is raised [

2]. When scaling the number of base AI units

beyond a certain number of tools or agents that reaches model or API limits, tool retrieval is needed. If the number of base AI units is low enough that LLMs can perform with high tool selection accuracy, then tool retrieval can be omitted from the architecture.

4.2. Tool, MCP, or Agent Retrieval

Tool retrieval is the process of storing and retrieving a large number of tools from a knowledge base, to scale the number of tools an LLM agent can handle. Every state-of-the-art retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) strategy and traditional regex or grep search with filesystems [

28,

106,

107] applies to tools [

108,

109].

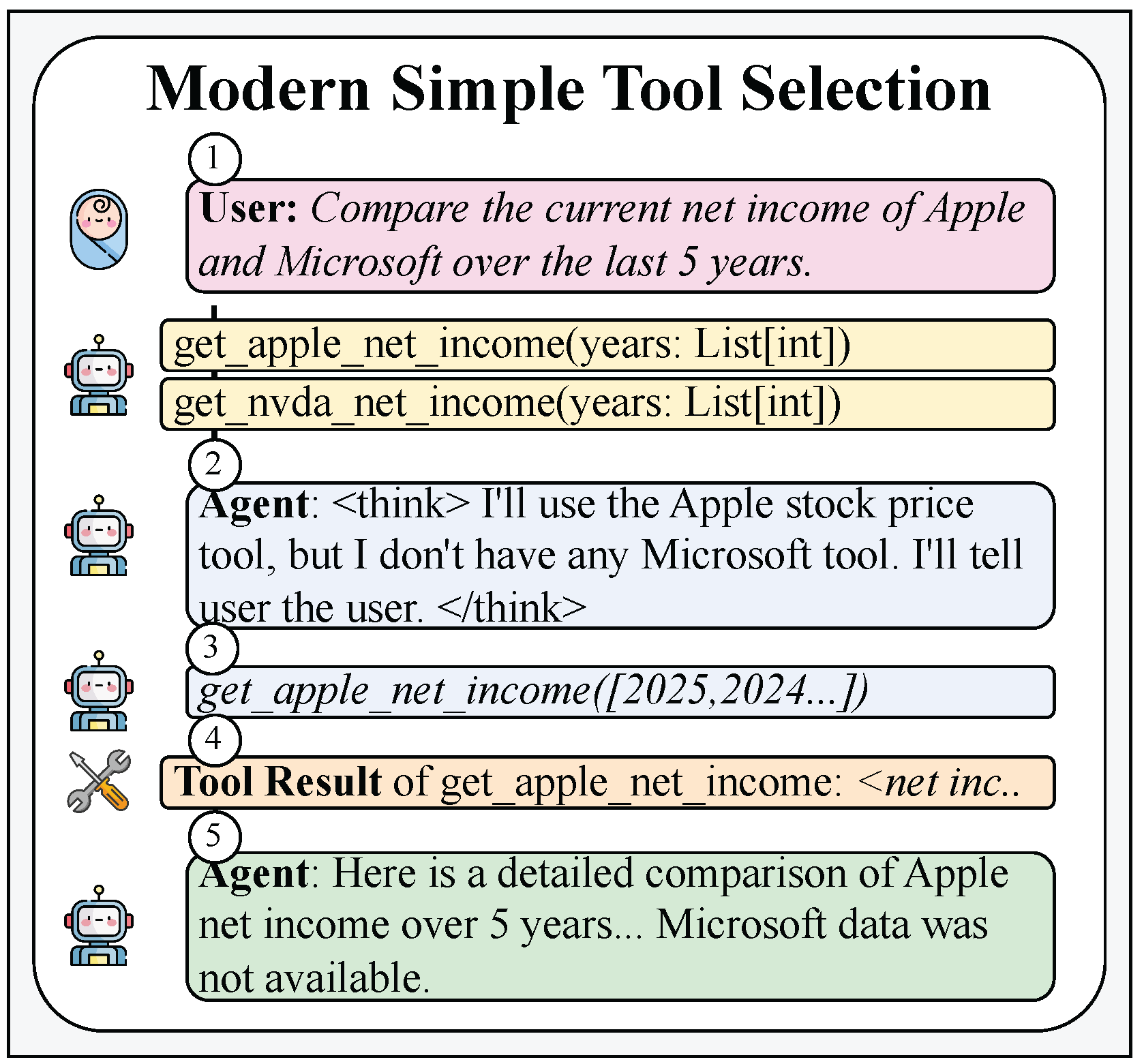

4.2.1. No Tool Retrieval

When the number of base AI units

in a system is low enough, tool retrieval is not required, and all available tools or agents can be directly equipped to the LLM agent. In this configuration, the model can reason, select, and execute the appropriate function using native tool calling without any retrieval or ranking step. This represents the simplest form of tool selection, where the agent operates entirely within its reasoning context and performs one-shot function execution based on user intent (

Figure 7).

4.2.2. Pre-Retrieval or Indexing

The goal of the indexing phase is to build a knowledge base over

whose retrieval performance is optimized through various chunking strategies, retrieval methods, and metadata enhancement [

8,

9,

10,

52,

110].

Storage and Retrieval Types

Tool and agent documents require appropriate storage and retrieval mechanisms that align with production needs. Vector databases store dense embeddings and enable efficient nearest-neighbor search for semantic retrieval. Knowledge graphs (KGs) represent entities and relationships explicitly, supporting structured retrieval through graph traversal when tools depend on one another, with dependencies encoded as edges in the graph. GraphRAG methods combine vector similarity with KG traversal to leverage both semantic and structural dependencies between tools [

22,

109,

111,

112,

113]. Lexical methods such as BM25 remain competitive baselines, offering interpretability and speed when terminology is consistent. Hybrid RAG approaches integrate vector retrieval with lexical keyword matching using a ranking function [

106,

113]. Traditional structured storage systems, including SQL and NoSQL databases, support fast lookups through identifiers and metadata filters. The selection of storage and retrieval methods depends on latency constraints, corpus size, and the degree of tool interdependence. When using embeddings, they can be computed with general-purpose models [

114,

115,

116] or with retrievers fine-tuned on domain-specific interaction data to enhance retrieval accuracy [

10,

110].

4.2.3. Intra-Retrieval or Inference Time

The goal of the intra-retrieval or inference time phase is to retrieve all of the relevant tools, MCPs, or agents to answer the user question.

Planner/CoT

Query decomposition is critical to break down complex user queries and retrieve relevant tools for each sub-task. Traditional methods use a planner or query decomposition [

8,

10,

50,

118] to retrieve relevant tools in a parallelized workflow. Recent advancements in CoT-reasoning-LLMs allow the LLM to call tools during its chain of thought, allowing the planning, query decomposition, and retrieval to be coupled in the same chain of thought step.

Agentic RAG

Agentic RAG allows an LLM to decompose user queries by calling tools from the tool knowledge base, where each subquery corresponds to an individual tool call. Recent advances in CoT-reasoning LLMs enable the model to break down queries and use knowledge-base search tools directly within its chain of thought. The direct impact of agentic RAG is less steps in a predefined workflow, saving latency, cost, but more error-prone due to relying on tool calling from the LLM [

10,

11,

121,

122,

123].

4.2.4. Post-Retrieval

The goal of post-retrieval is to refine, iterate, and finalize the set of retrieved tools or agents from the intra-retrieval stage.

Reranking

Typically, an efficient, first-pass, bi-encoder or lexical retrieval search is performed in the intra-retrieval stage, and a second-pass cross-encoder or LLM is employed to rerank or refine the subset of tools or agents [

21,

110,

124]. Reranking models are optimized to reorder tool or agent results based on the user query. Due to their computational complexity, rerankers are applied to a narrowed subset of results rather than the full tool or agent set.

Self-Correction

Another modern agentic approach for post-retrieval is self-correction, tightly coupled with retrieval strategies such as agentic RAG. In self-correction, if the system detects that no agent or tool is relevant, it can re-query the knowledge base to try alternative search formulations [

20,

121,

122]. If self-correction is not implemented through agentic RAG, it functions as an additional workflow or DAG condition looping back to the initial query node.

Parameter Prediction Considerations

Depending on the Tool, MCP, or Agent execution architecture and whether the Base AI Unit is a

, there are parameter prediction considerations. If the Base AI Unit consists only of agents, the architecture can simply send the user query, or a decomposed query, to each of the final retrieved agents. If the Base AI Unit is a Tool, a thin layer of parameter prediction is required, either in the retrieval step or during execution [

10,

11,

52,

110]. When a tool’s parameter depends on the output of another tool, additional retrieval may be necessary, as in GraphRAG-based dependency modeling [

109,

111,

112]. If the retrieval architecture follows an agentic RAG design, closely integrated with the execution architecture, as in MemTool or ScaleMCP, parameter prediction can be handled natively through function calling within the agent’s reasoning process [

9,

18].

4.3. Tool, MCP, and Agent Execution

Tool execution invokes preselected or inference-chosen tools using either native function calling or agentic workflows arranged sequentially, in parallel, or as DAGs [

2,

3,

11,

38,

47,

48,

52,

76]. The execution design determines whether retrieval occurs and how tools are selected and parameterized.

Coupling Retrieval to Execution or Execution to Retrieval

Retrieval may occur within the execution loop, as in agentic RAG [

9,

18,

20,

121,

122], where tools are dynamically equipped during reasoning. Alternatively, execution may follow a fixed retrieval plan, executing a predefined DAG or sequence. When a function-calling agent receives the retrieved set and decides which tools to call, the two stages remain loosely coupled.

Methods

The two primary methods for tool, MCP, or agent execution are (i) native function-calling supervisor or orchestration agents and (ii) agentic workflows [

2,

3,

9,

11,

38,

47,

48,

52,

76]. While agentic workflows can include function calling within the DAG or workflow, their execution path is typically deterministic, with agentic loops predefined by the system design.

Function Calling

If the Base AI unit is a Tool, then a set of tools or MCP servers will be dynamically equipped to a top-level orchestration or supervisor LLM agent, given the task to use the dynamic set of tools to answer the user question. If the Base AI unit is an agent, then the agent becomes an agent-as-a-tool or subagent, attached to a top-level supervisor agent. Furthermore, if tools and agents are retrieved, then both tools and agents are attached to the supervisor or orchestrator agent, which subsequently has access to both the sub-agents and tools. However, these configurations and requirements can be customized by the practitioner.

Native function calling is typically JSON-typed, where the tool-call specification is filled by the agent using JSON. Recent research and provider tooling also support Python-based execution, shell-based, and lightweight XML/keyword query forms, and these are now increasingly used across frameworks rather than traditional native function calling [

15,

27,

28,

38,

125,

126,

127,

128]. In parallel, several providers and RL frameworks encourage lightweight XML-style directives (e.g., <search>, <tool>) interleaved with a model’s reasoning both for structured prompting and for rollouts that call search tools during training [

123,

129,

130,

131,

132,

133,

134]. In practice, modern stacks expose a broader, hierarchical action space that offloads context from the model: (i) schema-safe JSON function calls, (ii) sandboxed CLI utilities executed in a VM (shell/file I/O), which are easy to extend without modifying model context and handle large outputs via files, and (iii) code execution over packages/APIs (e.g., short Python programs that call pre-authorized services) [

15]. These layers can be presented behind a single tool call abstraction, since changing the function definitions of an LLM across multi-turns resets the prompt cache, effecting cost and latency reductions [

2,

15,

25,

27,

28,

59,

60,

135]. Complementarily, MCP-driven code-based function calling presents tools as code APIs that the agent imports on demand, reducing token overhead from loading many tool definitions and keeping large intermediate results out of the context [

27,

28]. However, advanced methods such as constrained sampling/decoding increase tool calling accuracy with native JSON-function calling, thus high-accuracy dynamic tool use without resetting the cache during code or bash tool calling is an open area of research. [

2,

25].

Agentic Workflows

Agentic workflows, or DAG-based execution systems, consist of predefined nodes and edges that limit flexibility but offer low latency through parallelization and minimal function-calling overhead. Common themes include parallel or map-reduce execution, sequential prompt chains for deterministic tasks, and multi-round loops revisiting earlier nodes to handle errors or incomplete results. Native function calling can be embedded within these workflows. For instance, a retrieval node may first select dynamic tools then equip them to an agent in the following node to answer a query [

8,

18]. Parameter prediction is often integrated into retrieval or DAG creation. When one tool’s parameters depend on another’s output, the dependency can be resolved during DAG construction, ensuring correct execution order [

111,

112]. Recent coding agent platforms integrate similar orchestration principles directly into their environments, offering multi-agent parallel execution modes and native coordination tools [

62,

64,

71,

136,

137,

138].

Tool Call Result Context Engineering

A single or multiple tool call results can often exceed the context window of an LLM. Therefore, common practice in production systems is to reduce, isolate, and offload the tool result before sending them to the LLM context. Reduction can be achieved through truncation and LLM summarization, isolation involves separating raw payloads outside the prompt with lightweight references, and offloading moves large data blobs to files so that later steps fetch only what is needed [

55,

155,

156,

157]. For structured JSON or XML, use post-processing to keep only needed fields, trim long outputs, or render compact markdown [

56,

158]. In production, it is common to use a combination of one or more of these strategies, and optimizing long-running tasks with tool calls is an open area of research.

Additionally, tool result caching for read-only tools that reset after a period of time can improve latency and cost in production settings. For example, if a tool result to fetch quarterly financial metrics from a database does not change until the next quarter, then caching can prevent repeated execution of that query for all users by saving the result and avoiding redundant database queries [

57,

58,

159,

160].

Associated Prompts

When attaching a set of individual, unrelated tools to a top-level supervisor or orchestration agent, the agent may not understand the nuances or complexities of how to use the tools. By appending tool-associated prompts to the supervisor’s system prompt from an MCP server [

1,

25], the supervisor agent has more context about how to use the tools in a longer-running job, rather than the sole tool description and input parameter descriptions.

Human-in-the-Loop

During tool execution, tools or agents may need human approval or clarification that pauses tool execution, either due to user or agent authentication or authorization, or the severity of the tool [

32]. The human can either verify or confirm the tool execution, commonly with a button click or verbal approval [

62,

63,

64]. The other approach is editing a tool call, where the human can manually change the input parameters to the tool from a UI, or with natural language back to the agent[

32]. As stated previously, tools or agents may need human-in-the-loop approval due to being write-based tools, rather than read-only tools, which require further approval for production-grade applications.

Authorization

Authorization is a critical factor in the execution phase of agents, to prevent restricted access based on the user’s role or status. If a tool or agent is selected for execution but the user lacks access, the run should stop altogether [

40,

41]. Authorization can be applied in both the retrieval and execution phases. In the retrieval phase, unauthorized tools or agents are filtered out before selection, so they never enter the final available set or DAG. In the execution phase, the system may retrieve and select from the full catalog (even if the user lacks access), but each tool or agent execution is checked and authorized, and the supervisor must replan or abort. The choice of where to enforce authorization depends on production environments. A common pattern is retrieval-time filtering for privacy and determinism, with execution-time checks giving the user transparency of the agent access [

161].

4.4. Memory for Multi-Turn Tool Selection

Memory for tool selection for Large Language Model (LLM) agents enables the persistent accumulation of knowledge, sustained contextual awareness, and adaptive decision-making informed by historical interactions and prior experiences. Existing literature divides memory for AI systems into short-term and long-term memory, each serving distinct but complementary roles in multi-turn agentic interactions [

162].

4.4.1. Short-Term Memory for Dynamic Tool Management

Short-term memory manages inputs within limited context windows, consisting of sensory inputs (e.g., tools, multimodal data) and working memory (session messages) [

162]. The majority of flagship model context windows fall between 100,000 to 1,000,000 tokens [

163,

164], requiring effective strategies to prevent token overflow and prune context that distracts the model during task execution [

165,

166,

167,

168].

While performing tool and agent selection over multi-turn user interactions, removing and adding dynamic sets of tools and agents in the available context window of the system becomes critical. MemTool [

18] introduces short-term dynamic tool memory that gives the LLM agent autonomy to prune its available dynamic tools and search for new ones across a session. Previous tool retrieval approaches focus on a single turn, rather than multi-turn tool selection [

8,

10,

20,

42].

4.4.2. Long-Term Memory for Personalized Tool Use

Long-term memory involves storing information for extended periods that persist across sessions, enabling the model to retain knowledge and learned tools over time [

162,

169,

170]. It includes explicit memory (key facts, events) and implicit memory (skills, procedures), with explicit memory further dividing into episodic memory (personal experiences) and semantic memory (facts about the environment) [

171].

Existing memory frameworks [

172,

173,

174,

175] manage the persistence of long-term interactions either through a vector database, knowledge graph, or traditional database, and contain built-in modules for context engineering [

174,

176]. Long-term tool memory approaches focus on personalized tool calling based on the user, adapting tool usage based on user preferences and historical interaction patterns [

177,

178,

179].

4.5. Evaluations

Evaluation spans two axes: (i) whether the system retrieves the right tools and (ii) whether execution produces correct task outcomes, with operational analytics guiding iteration.

4.5.1. Tool Retrieval Metrics

Tool retrieval is an information-retrieval problem where reporting standard IR metrics is common: Recall@k, Precision@k, MRR@k, nDCG@k, and mAP@k on ground-truth tool sets [

180]. Other agent-specific tool retrieval metrics include tool completeness and correctness, or whether the expected tools were surfaced and called [

181]. For tool-applied RAG retrieval [

8], there is Context Precision and Context Recall to quantify ranking quality and coverage, consistent with common RAG evaluation workflows [

182].

4.5.2. Execution Metrics

For execution-based metrics, LLM-as-a-judge is the established evaluation guideline for whether the LLM agent answered the question using the correct tools [

12,

144,

145,

146,

147,

150,

183,

184,

185,

186]. Task Completion indicates end-to-end success of agentic workflows and multi-round tool calling workflows [

187].

4.5.3. Tool Analytics

Standard tool and agent analytics include metrics such as the total number of base AI units in the system and whether those base AI units span tools or agents. Operational telemetry metrics should cover latency of tools and agents, token usage, cost, error/failure rates, and popularity/performance by tool or agent [

188]. Having predictive analytics on which tool and agent are used the most can also indicate poisoning techniques by MCP servers to influence retrieval and selection architectures [

117].

5. Conclusions

Large Language Model (LLM) agents are evolving into complex systems capable of reasoning, acting, and collaborating through external tools, Model Context Protocol (MCP) servers, and other agents. As these systems scale, selecting the appropriate tool or agent efficiently and securely has become a key challenge for real-world deployment. This work has examined the landscape of tool and agent selection from both frontend and backend perspectives, outlining how production systems integrate retrieval, orchestration, execution, and memory to achieve scalable and reliable performance. We have also highlighted how emerging standards such as MCP and Agent-to-Agent (A2A) communication, together with mechanisms for authorization, human-in-the-loop verification, and context memory, are shaping the next generation of tool-using agents. Looking ahead, as agents become more autonomous, there are emerging retrieval systems not just for agents, tools, or MCP servers, but also skills, which are consolidated sets of instructions, tools, and agents that complete a task. Furthermore, as agents are fine-tuned for long-running tasks with upwards of 200–300 sequential tool calls, the aforementioned retrieval systems and context engineering techniques will be trained into the underlying model themselves. We hope that future research is guided by this modern work of agent and tool selection in production.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

References

- Model Context Protocol. Tools Documentation (MCP Concepts). 2025. Available online: https://modelcontextprotocol.io/docs/concepts/tools.

- OpenAI. Function Calling. 2024. Available online: https://platform.openai.com/docs/guides/function-calling?api-mode=chat.

- Anthropic. Tool Use with Claude. 2024. Available online: https://docs.anthropic.com/en/docs/agents-and-tools/tool-use/overview.

- Microsoft Learn. Azure AI Agent Service (preview) — Overview. Accessed. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Amazon Web Services. Agents for Amazon Bedrock — Developer Guide. Accessed. 2025.

- LlamaIndex. Function Calling with Agents (LlamaIndex Examples), 2025. Accessed. 8 November 2025.

- deepset. Haystack Agents — Concepts and Usage. Accessed. 2025.

- Lumer, E.; Subbiah, V.K.; Burke, J.A.; Basavaraju, P.H.; Huber, A. Toolshed: Scale Tool-Equipped Agents with Advanced RAG-Tool Fusion and Tool Knowledge Bases. Also published in ICAART 2025 2024, 2410.14594. [Google Scholar]

- Lumer, E.; Gulati, A.; Subbiah, V.K.; Basavaraju, P.H.; Burke, J.A. ScaleMCP: Dynamic and Auto-Synchronizing Model Context Protocol Tools for LLM Agents. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Y.; Liang, S.; Ye, Y.; et al. ToolLLM: Facilitating Large Language Models to Master 16000+ Real-World APIs. arXiv 2023, 2307.16789. [Google Scholar]

- Du, Y.; Wei, F.; Zhang, H. AnyTool: Self-Reflective, Hierarchical Agents for Large-Scale API Calls. arXiv 2024, 2402.04253. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, K.; Gulati, A.; Lumer, E.; Campagna, S.; Subbiah, V.K. Jackal: A Real-World Execution-Based Benchmark Evaluating Large Language Models on Text-to-JQL Tasks. 2025, 2509.23579. [Google Scholar]

- Aizawa, K.; Engineering, A. Writing Effective Tools for Agents — with Agents. 11 September 2025. Available online: https://www.anthropic.com/engineering/writing-tools-for-agents (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Microsoft. AutoGen (AG2) — Multi-Agent Framework. Accessed. 2025.

- Manus. Manus. 2025. Available online: https://manus.im/.

- CrewAI. CrewAI — Documentation, 2025. Accessed. 8 November 2025.

- AgentScope Contributors. AgentScope: A Flexible Yet Robust Framework for Building AI Agents. Accessed. 2024.

- Lumer, E.; Gulati, A.; Subbiah, V.K.; Basavaraju, P.H.; Burke, J.A. MemTool: Optimizing Short-Term Memory Management for Dynamic Tool Calling in LLM Agent Multi-Turn Conversations. 2025, 2507.21428. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, G.; Zhong, W.; Chen, J.; Chen, X.; Lu, Y.; Lin, H.; He, B.; Han, X.; Sun, L. LiveMCPBench: Can Agents Navigate an Ocean of MCP Tools? arXiv 2025, arXiv:2508.01780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yoon, J.; Sachan, D.S.; et al. Re-Invoke: Tool Invocation Rewriting for Zero-Shot Tool Retrieval. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Li, P.; Liu, W.; et al. ToolRerank: Adaptive and Hierarchy-Aware Reranking for Tool Retrieval. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Microsoft. GraphRAG — A Graph-based Approach to Retrieval-Augmented Generation. Accessed. 2024.

- Sarmah, P.; et al. Hybrid RAG: Integrating Knowledge Graphs with Retrieval-Augmented Generation. arXiv 2024. arXiv:2408.

- ToolBench Contributors. ToolBench: A Comprehensive Benchmark for Tool Learning. Accessed. 2024.

- LangChain. Context Engineering for AI Agents with LangChain and Manus; Martin, Lance, Ji, Yichao “Peak”, Eds.; LangChain Manus; Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6_BcCthVvb8 (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- AI, L. LangChain Documentation. 2025. Available online: https://docs.langchain.com/.

- Jones, A.; Kelly, C. Code execution with MCP: Building more efficient agents. 2025. Available online: https://www.anthropic.com/engineering/code-execution-with-mcp.

- Anthropic. Introducing advanced tool use on the Claude Developer Platform. Engineering blog. 2025. Available online: https://www.anthropic.com/engineering/advanced-tool-use.

- Vercel. AI Tools — Vercel AI SDK, 2025. Accessed. 8 November 2025.

- LlamaIndex. AgentToolSpec API Reference (LlamaIndex), 2025. Accessed. 8 November 2025.

- Amazon Web Services. Amazon GenAI — AgentCore (Serverless Agent Framework) Documentation. Accessed. 2025.

- LangChain, Blog. Introducing Ambient Agents. 2024. Available online: https://blog.langchain.com/introducing-ambient-agents/.

- OpenAI. Guardrails for Python (OpenAI), 2025. Accessed. 8 November 2025.

- NVIDIA. NVIDIA NeMo Guardrails — Documentation. Accessed. 2024.

- OWASP Foundation. OWASP Top 10 for Large Language Model Applications. Accessed. 2024.

- NIST. NIST AI Safety Institute Consortium (AISIC). Accessed. 2024.

- Ouyang, S.; Yan, J.; Hsu, I.H.; Chen, Y.; Jiang, K.; Wang, Z.; Han, R.; Le, L.T.; Daruki, S.; Tang, X.; et al. ReasoningBank: Scaling Agent Self-Evolving with Reasoning Memory. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Google. Function calling with the Gemini API. 2024. Available online: https://ai.google.dev/gemini-api/docs/function-calling.

- llama.cpp: Port of Facebook’s LLaMA model in C/C++, 2025. In GitHub repository; accessed; Gerganov, G., Ed.; (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Arcade. Tool Calling-Introduction. 2024. Available online: https://docs.arcade.dev/home/use-tools/tools-overview.

- Composio. Composio — Skills that evolve with your Agents, 2025. Website. accessed. (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Liu, M.M.; Garcia, D.; Parllaku, F.; Upadhyay, V.; Shah, S.F.A.; Roth, D. ToolScope: Enhancing LLM Agent Tool Use through Tool Merging and Context-Aware Filtering. arXiv 2025, arXiv:cs. [Google Scholar]

- Microsoft Blog. Agents in AutoGen. 2024. Available online: https://microsoft.github.io/autogen/0.2/blog/2024/05/24/Agent/.

- Krishnan, N. AI Agents: Evolution, Architecture, and Real-World Applications. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.12687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mistral, AI. Agents & Conversations, 2025. Mistral Docs. accessed. (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Anthropic. Introducing Agent Skills. 2025. Available online: https://www.anthropic.com/news/skills.

- AI, L. LangGraph Agent Supervisor Tutorial. 2025. Available online: https://langchain-ai.github.io/langgraph/tutorials/multi_agent/agent_supervisor/.

- Microsoft. Handoff Orchestration in Semantic Kernel. 2025. Available online: https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/semantic-kernel/frameworks/agent/agent-orchestration/handoff?pivots=programming-language-csharp.

- Li, M.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, B.; et al. API-Bank: A Comprehensive Benchmark for Tool-Augmented LLMs. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Cheng, Z.; Zhu, H.; Fried, D.; Neubig, G. What Are Tools Anyway? A Survey from the Language Model Perspective. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.15452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, C.; Dai, S.; Wei, X.; Cai, H.; Wang, S.; Yin, D.; Xu, J.; Wen, J.r. Tool Learning with Large Language Models: A Survey. Frontiers of Computer Science 2025, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S.G.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X.; Gonzalez, J.E. Gorilla: Large Language Model Connected with Massive APIs. arXiv 2023, 2305.15334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anthropic. Writing effective tools for AI agents — using AI agents, 2025. Engineering blog. accessed. (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Huang, T.; Jung, D.; Chen, M. Planning and Editing What You Retrieve for Enhanced Tool Learning. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: NAACL 2024, Accessed. 2024; (accessed on 10 November 2025). [Google Scholar]

- Ji, P. Context Engineering for AI Agents: Lessons from Building Manus, 2025. Manus Blog. accessed. (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- LangChain. Middleware, 2025. Documentation. accessed. (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- IETF. RFC 9111: HTTP Caching, 2022. Internet Standard. accessed. (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Docs, MDN Web. Cache-Control header — HTTP, 2025. Documentation. accessed. (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- OpenAI. Prompt caching. 2025. Available online: https://platform.openai.com/docs/guides/prompt-caching.

- Anthropic. Prompt caching with Claude. 2025. Available online: https://claude.com/blog/prompt-caching.

- Perplexity, AI. Getting Started with Perplexity Tools. 2024. Available online: https://www.perplexity.ai/hub/getting-started.

- Anthropic. Claude Code Overview. 2024. Available online: https://docs.anthropic.com/en/docs/claude-code/overview.

- Cursor IDE. Tools. 2024. Available online: https://docs.cursor.com/agent/tools.

- OpenAI. Codex CLI. 2025. Available online: https://developers.openai.com/codex/cli/.

- AI, C. What is Cline? 2025. Available online: https://docs.cline.bot/getting-started/what-is-cline.

- GitHub. GitHub Copilot Features. 2025. Available online: https://docs.github.com/en/copilot/get-started/features.

- Continue Dev. Automating Documentation Updates with Continue CLI, 2025. Documentation. accessed. (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- FlowiseAI. Tutorials: Interacting with API Tools & MCP; Human In The Loop; Agentic RAG, 2025. Documentation. accessed. (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Open WebUI. Action Function, 2025. Documentation. accessed. (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- LobeHub. Plugins, 2025. Documentation. accessed. (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Docs, GitHub. Use GitHub Copilot Agents. Accessed. 2024.

- OpenAI. What is the mentions feature for GPTs? 6 August 2025. Available online: https://help.openai.com/en/articles/8908924-what-is-the-mentions-feature-for-gpts.

- Windsurf, AI. Chat Overview. 2024. Available online: https://docs.windsurf.com/chat/overview.

- Anthropic. Customize Claude Code with plugins. 2025. Available online: https://www.anthropic.com/news/claude-code-plugins.

- Windsurf. Windsurf — Slash Commands Reference. Accessed. 2025.

- Mistral, AI. Function Calling. 2024. Available online: https://docs.mistral.ai/capabilities/function_calling/.

- Meta. Tool Calling. 2024. Available online: https://llama.developer.meta.com/docs/features/tool-calling.

- xAI. Function Calling. 2024. Available online: https://docs.x.ai/docs/guides/function-calling.

- Groq. Compound. 2024. Available online: https://console.groq.com/docs/agentic-tooling#use-cases.

- Cloud, Google. Vertex AI Generative AI — Introduction to function calling. 2024. Available online: https://cloud.google.com/vertex-ai/generative-ai/docs/multimodal/function-calling.

- Amazon Web Services. Use a tool to complete an Amazon Bedrock model response. 2024. Available online: https://docs.aws.amazon.com/bedrock/latest/userguide/tool-use.html.

- Google Gemini, CLI. Gemini CLI Core: Tools API. 2024. Available online: https://github.com/google-gemini/gemini-cli/blob/main/docs/core/tools-api.md.

- IBM. Tool Calling. 2024. Available online: https://www.ibm.com/watsonx/developer/capabilities/tool-calling.

- Reka, AI. Function Calling. 2024. Available online: https://docs.reka.ai/chat/function-calling.

- Inflection, AI. Inflection Inference API (1.0.0). 2024. Available online: https://developers.inflection.ai/api/docs.

- SmolAgents. SmolAgents Tools. 2024. Available online: https://huggingface.co/docs/smolagents/tutorials/tools.

- Mistral, AI. Function Calling, 2025. Mistral Docs. accessed. (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Ollama. How to Create Tools to Extend AI with Functions, 2024. Blog post. accessed. (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Xu, T.; Brockman, G.; McLeavey, C.; Sutskever, I. Robust Speech Recognition via Large-Scale Weak Supervision. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.04356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baevski, A.; Zhou, H.; Mohamed, A.; Auli, M. wav2vec 2.0: A Framework for Self-Supervised Learning of Speech Representations. arXiv arXiv:2006.11477.

- Zhang, Y.; et al. USM: Scaling Automatic Speech Recognition Beyond 100 Languages. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.01037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. Realtime API Overview. 2024. Available online: https://platform.openai.com/docs/guides/realtime.

- Sesame, AI. Crossing the Uncanny Valley of Conversational Voice. 2024. Available online: https://www.sesame.com/research/crossing_the_uncanny_valley_of_voice.

- Cohere. Basic usage of tool use (function calling). 2024. Available online: https://docs.cohere.com/docs/tool-use-overview.

- Liu, H.; Li, C.; Wu, Q.; Lee, Y.J. Visual Instruction Tuning. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.08485. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lumer, E.; Cardenas, A.; Melich, M.; Mason, M.; Dieter, S.; Subbiah, V.K.; Basavaraju, P.H.; Hernandez, R. Comparison of Text-Based and Image-Based Retrieval in Multimodal Retrieval Augmented Generation Large Language Model Systems. arXiv 2025, arXiv:cs. [Google Scholar]

- Microsoft. Visual Studio Code: Intelligent Code Assistance. 2024. Available online: https://code.visualstudio.com/docs/editor/intellisense.

- Park, J.S.; O’Brien, J.C.; Cai, C.J.; Morris, M.R.; Liang, P.; Bernstein, M.S. Generative Agents: Interactive Simulacra of Human Behavior. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.03442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mem0. Mem0: The Memory Layer for Personalized AI. 2025. Available online: https://mem0.ai/.

- LlamaIndex. Long-Term Memory in LlamaIndex, 2025. Accessed. 8 November 2025.

- LangChain, AI. LangGraph — Persistence and Checkpointing, 2025. Accessed. 8 November 2025.

- Python Software Foundation. Python Documentation. 2025. Available online: https://docs.python.org/3/.

- Microsoft. TypeScript Documentation. 2025. Available online: https://www.typescriptlang.org/docs/.

- Google DeepMind and Google Research. Announcing the Agent2Agent Protocol (A2A). 2025. Available online: https://developers.googleblog.com/en/a2a-a-new-era-of-agent-interoperability/.

- IBM Research. The simplest protocol for AI agents to work together. 2025. Available online: https://research.ibm.com/blog/agent-communication-protocol-ai.

- Heule, S.; Jia, E.; Jain, N. Improving agent with semantic search. Cursor research blog post. 2025. Available online: https://cursor.com/blog/semsearch.

- Huang, N. How agents can use filesystems for context engineering. 2025. Available online: https://blog.langchain.com/how-agents-can-use-filesystems-for-context-engineering/ LangChain.

- Gao, Y.; Xiong, Y.; et al. Retrieval-Augmented Generation for Large Language Models: A Survey. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Y.; et al. Graph Retrieval-Augmented Generation: A Survey. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Zhu, T.; Han, H.; et al. SEAL-Tools: Self-Instruct Tool Learning Dataset for Agent Tuning and Detailed Benchmark. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Shomer, H.; Wang, Y.; Lei, Y.; Guo, K.; Hua, Z.; Long, B.; Liu, H.; Tang, J. RAG vs. GraphRAG: A Systematic Evaluation and Key Insights. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.11371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumer, E.; Basavaraju, P.H.; Mason, M.; Burke, J.A.; Subbiah, V.K. Graph RAG-Tool Fusion. 2025, 2502.07223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarmah, B.; Hall, B.; Rao, R.; Patel, S.; Pasquali, S.; Mehta, D. HybridRAG: Integrating Knowledge Graphs and Vector Retrieval Augmented Generation for Efficient Information Extraction. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2408.04948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. Embedding Models. 2024. Available online: https://platform.openai.com/docs/guides/embeddings/embedding-models.

- Cohere. Cohere Embed Models. 2024. Available online: https://docs.cohere.com/docs/cohere-embed.

- Cloud, Google. Vertex AI Embeddings (preview). 2025. Available online: https://cloud.google.com/vertex-ai/generative-ai/docs/embeddings.

- Shi, J.; Yuan, Z.; Tie, G.; Zhou, P.; Gong, N.Z.; Sun, L. Prompt Injection Attack to Tool Selection in LLM Agents. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.19793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, H.; Balasubramanian, N.; Khot, T.; Sabharwal, A. Interleaving Retrieval with Chain-of-Thought Reasoning for Knowledge-Intensive Multi-Step Questions. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lumer, E.; Nizar, F.; Gulati, A.; Basavaraju, P.H.; Subbiah, V.K. Tool-to-Agent Retrieval: Bridging Tools and Agents for Scalable LLM Multi-Agent Systems. arXiv 2025, arXiv:cs. [Google Scholar]

- Nizar, F.; Lumer, E.; Gulati, A.; Basavaraju, P.H.; Subbiah, V.K. Agent-as-a-Graph: Knowledge Graph-Based Tool and Agent Retrieval for LLM Multi-Agent Systems. arXiv 2025, arXiv:cs. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.; Ehtesham, A.; Kumar, S.; Talaei Khoei, T. Agentic Retrieval-Augmented Generation: A Survey on Agentic RAG. arXiv arXiv:2501.09136. [CrossRef]

- Maragheh, R.Y.; Vadla, P.; Gupta, P.; Zhao, K.; Inan, A.; Yao, K.; Xu, J.; Kanumala, P.; Cho, J.; Kumar, S. ARAG: Agentic Retrieval Augmented Generation for Personalized Recommendation. arXiv arXiv:2506.21931. [CrossRef]

- Jin, B.; Zeng, H.; Yue, Z.; Yoon, J.; Arik, S.Ö.; Wang, D.; Zamani, H.; Han, J. Search-R1: Training LLMs to Reason and Leverage Search Engines with Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.09516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumer, E.; Melich, M.; Zino, O.; Kim, E.; Dieter, S.; Basavaraju, P.H.; Subbiah, V.K.; Burke, J.A.; Hernandez, R. Rethinking Retrieval: From Traditional Retrieval Augmented Generation to Agentic and Non-Vector Reasoning Systems in the Financial Domain for Large Language Models. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2511.18177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y.; Peng, H.; Ji, H. Executable Code Actions Elicit Better LLM Agents. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.01030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varda, K.; Pai, S. Code Mode: the better way to use MCP. 2025. Available online: https://blog.cloudflare.com/code-mode/.

- Hacker News. Discussion: Code Mode — the better way to use MCP. 2025. Available online: https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=45830318.

- Mistral, AI. Tools, 2025. Mistral Docs. accessed. (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Moonshot, AI. Kimi K2 — Thinking. 2025. Available online: https://moonshotai.github.io/Kimi-K2/thinking.html.

- Anthropic. Use XML tags to structure your prompts. 2025. Available online: https://anthropic.mintlify.app/en/docs/build-with-claude/prompt-engineering/use-xml-tags.

- OpenAI. Reasoning models. 2025. Available online: https://platform.openai.com/docs/guides/reasoning.

- Together, AI. DeepSeek-R1 Quickstart. 2025. Available online: https://docs.together.ai/docs/deepseek-r1.

- veRL Maintainers. Search Tool Integration — Multi-Turn RL. 2025. Available online: https://verl.readthedocs.io/en/latest/sglang_multiturn/search_tool_example.html.

- Moonshot, AI. Kimi K2: Open Agentic Intelligence. arXiv arXiv:2507.20534. [CrossRef]

- Google AI for Developers. Context caching — Gemini API. 2025. Available online: https://ai.google.dev/gemini-api/docs/caching?lang=py.

- Cursor Team. Introducing Cursor 2.0 and Composer · Cursor. 2025. Available online: https://cursor.com/blog/2-0.

- LangChain. Deep Agents overview — Docs by LangChain. 2025. Available online: https://docs.langchain.com/oss/python/deepagents/overview.

- OpenDevin Contributors. OpenDevin — Autonomous Software Engineering Agent. Accessed. 2024.

- Anthropic. Introducing Claude Sonnet 4.5. 2025. Available online: https://www.anthropic.com/news/claude-sonnet-4-5.

- Qian, C.; Acikgoz, E.C.; He, Q.; Wang, H.; Chen, X.; Hakkani-Tür, D.; Tur, G.; Ji, H. ToolRL: Reward is All Tool Learning Needs. arXiv arXiv:2504.13958.

- Dong, G.; Chen, Y.; Li, X.; Jin, J.; Qian, H.; Zhu, Y.; Mao, H.; Zhou, G.; Dou, Z.; Wen, J.R. Tool-Star: Empowering LLM-Brained Multi-Tool Reasoner via Reinforcement Learning. arXiv arXiv:2505.16410.

- Anonymous. Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards: GRPO’s Effective Loss. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.06639. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, J.; Magazine, R.; Pandya, Y.; Nambi, A. Agentic Reasoning and Tool Integration for LLMs via Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2025, arXiv:cs. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, S.; Shinn, N.; Razavi, P.; Narasimhan, K. τ-bench: A Benchmark for Tool-Agent-User Interaction in Real-World Domains. arXiv 2024. arXiv:2406.12045.

- Barres, V.; Dong, H.; Ray, S.; Si, X.; Narasimhan, K. τ2-Bench: Evaluating Conversational Agents in a Dual-Control Environment. arXiv arXiv:2506.07982.

- Chen, C.; Hao, X.; Liu, W.; Huang, X.; Zeng, X.; Yu, S.; Li, D.; Wang, S.; Gan, W.; Huang, Y.; et al. ACEBench: Who Wins the Match Point in Tool Usage? arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.12851. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, L.; Du, Z.; Zhang, X.; Hu, H.; Tang, J. ComplexFuncBench: Exploring Multi-Step and Constrained Function Calling under Long-Context Scenario. arXiv arXiv:2501.10132.

- Wang, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, L.; Peng, H.; Ji, H. MINT: Evaluating LLMs in Multi-turn Interaction with Tools and Language Feedback. arXiv 2024. arXiv:2309.10691. [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, J.; Song, X.; Peng, Z.; Deng, K.; Zhang, C.; Wang, J.; Peng, J.; et al. MTU-Bench: A Multi-granularity Tool-Use Benchmark for Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, S.G.; Mao, H.; Yan, F.; Ji, C.C.; Suresh, V.; Stoica, I.; Gonzalez, J.E. The Berkeley Function Calling Leaderboard (BFCL): From Tool Use to Agentic Evaluation of Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 42nd International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML), 2025. [Google Scholar]

- WebArena Contributors. WebArena: Open, Reproducible Web Environments for Agents. Accessed. 2024.

- VisualWebArena Contributors. VisualWebArena: A Visual Web Navigation Benchmark for Multimodal Agents. Accessed. 2024.

- BrowserGym Contributors. BrowserGym: A Browser Automation and Web Agent Benchmark. Accessed. 2024.

- AgentBoard Contributors. AgentBoard: A Unified Platform for Evaluating LLM Agents. Accessed. 2024.

- Schmid, P. The New Skill in AI is Not Prompting, It’s Context Engineering, 2025. Blog post. published. 30 06 2025. (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- LangChain. Context engineering in agents, 2025. Documentation. accessed. (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Martin, L. Context Engineering for Agents, 2025. Blog post. accessed. (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- OpenAI. Structured model outputs, 2025. Documentation. accessed. (accessed on 9 November 2025).

-

Redis; Redis, 2025.

- LangChain. Node-level caching in LangGraph, 2025. Changelog. accessed. (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Databricks. Agent Framework — Databricks GenAI, 2025. Accessed. 8 November 2025.

- Wu, S.; Others. Human Memory for AI Memory: Building Agent Memory from Cognitive Psychology. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Vellum. LLM Context Window Comparison. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Shang, S. LongRoPE 2: Nearly Lossless LLM Context Extension, 2025. arXiv.

- Laban, S. LLMs Lost in Multi-Turn Conversation, 2025. arXiv.

- Hong, S. Context Management for Multi-Turn Conversations, 2025. arXiv.

- Chirkova, S. Provence: Efficient and Robust Context Management. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Schmid, S. Context Engineering for LLM Agents, 2025. arXiv.

- Park, J.S.; Others. Generative Agents: Interactive Simulacra of Human Behavior. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.03442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, W.; Others. MemoryBank: Enhancing Large Language Models with Long-Term Memory. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alake, R. Agent Memory: Episodic and Semantic Memory for LLMs. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Mem0. Mem0: The Memory Layer for AI Applications. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zep. Zep: Long-Term Memory for AI Assistants. 2025.

- Letta. Letta: Build Stateful LLM Applications. 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Packer, C.; Others. MemGPT: Towards LLMs as Operating Systems. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2310.08560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S. AMem: Agentic Memory for LLM Agents, 2025. arXiv.

- Zhang, W.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, C.; Yang, L.; Shang, J.; Wei, Z.; Zou, H.P.; Huang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Gao, Y.; et al. PersonaAgent: When Large Language Model Agents Meet Personalization at Test Time. 2025. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.06254.

- Hao, Y.; Cao, P.; Jin, Z.; Liao, H.; Chen, Y.; Liu, K.; Zhao, J. Evaluating Personalized Tool-Augmented LLMs from the Perspectives of Personalization and Proactivity. 2025. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.00771.

- Cheng, Z.; Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Guo, Y.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, H. ToolSpectrum: Towards Personalized Tool Utilization for Large Language Models. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.13176.

- Manning, C.D.; Raghavan, P.; Schütze, H. Introduction to Information Retrieval; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- DeepEval. Tool Correctness. 2025. Available online: https://deepeval.com/docs/metrics-tool-correctness.

- Ragas. Metrics Overview. 2025. Available online: https://docs.ragas.io/en/latest/concepts/metrics/.

- OpenAI. Evaluation Best Practices. 2025. Available online: https://platform.openai.com/docs/guides/evaluation-best-practices.

- OpenAI. Working with evals. 2025. Available online: https://platform.openai.com/docs/guides/evals.

- Ragas. Response Relevancy. 2025. Available online: https://docs.ragas.io/en/stable/concepts/metrics/available_metrics/answer_relevance/.

- Ragas. Ragas Metric Faithfulness. 2025. Available online: https://docs.ragas.io/en/latest/concepts/metrics/available_metrics/faithfulness/.

- DeepEval. Task Completion. 2025. Available online: https://deepeval.com/docs/metrics-task-completion.

- LangChain. Monitor projects with dashboards. 2025. Available online: https://docs.langchain.com/langsmith/dashboards.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).