1. Introduction

Dengue is the most important tropical-subtropical arboviral disease, responsible for cyclic epidemics in more than 100 countries globally [

1]. The etiological agent of the disease is dengue virus, a term that groups four genetically and antigenically related viruses known as dengue virus serotypes. The serotypes are numbered 1 to 4 (DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3, DENV-4) according to the chronological order of their discovery. The four serotypes share 60-75% homology in their amino acid sequences, and each is further subdivided into genotypes based on nucleotide variability within the serotype [

2,

3]. Each serotype can cause dengue, and infection with one serotype does not confer long-lasting immunity to the others [

4]. A fifth serotype was identified in 2013, but the extent of its contribution to epidemic events remains undetermined [

5].

Like all arboviruses, dengue viruses are maintained through an arthropod-host cycle, primarily involving

Aedes mosquitoes and humans in urban epidemic cycles. Nevertheless, enzootic and epizootic cycles have also been documented and are likely to represent the original sylvatic cycle [

6,

7]. Approximately 80% of dengue infections are asymptomatic, while the remaining cases present with either a non-specific fever or classic dengue fever (DF). Although DF is usually self-limiting, it can progress to life-threatening forms like dengue hemorrhagic fever (DHF) and dengue shock syndrome (DSS) [

8]. Clinically, the traditional classification has been revised into two categories—dengue and severe dengue—to better reflect case severity and guide appropriate management [

9]. The progression to severe dengue is driven by a complex interplay of, host variability, age, comorbidities and ecological factors [

10]. Additionally, the virulence of different dengue serotypes or genotypes varies, and their replacement or co-circulation in endemic areas is a common occurrence [

11,

12]. The introduction of a new serotype in endemic area can lead to severe secondary infections due to a phenomenon known as antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE). ADE may be triggered by circulating antibodies from the first infection, which have little neutralizing effect on the heterologous viral particle, thereby increasing the cellular uptake of the live viral particles [

13,

14].

Sporadic dengue epidemics have been recorded globally since the early 19th century. A major shift occurred in Southeast Asia post-World War II, with increasing urban epidemics, multiple serotype co-circulation, and the first DHF outbreak [

15,

16]. Since the mid-1970s, DHF has become the leading cause of hospitalizations and deaths in Asia, accounting for 70% of the global burden [

6]. In recent decades, Central and South America have experienced the most dramatic epidemiological changes. After an

A. aegypti eradication program in the mid-20th century, only isolated dengue outbreaks occurred, but its cessation in 1970 led to vector resurgence [

17]. Major epidemics began in the 1980s with the introduction of all four serotypes and DHF outbreaks [

18]. In 2023, the Americas faced their worst dengue outbreak with 4.6 million cases, doubling in the first four months of 2024 [

19,

20]. Overall, it has been estimated that there are approximately 96 million symptomatic dengue infections and an additional 390 million asymptomatic infections every year worldwide, while about 3.9 billion people are at risk of infection [

21].

Dengue viruses are single-stranded, positive-sense RNA viruses of the family Flaviviridae. The virion is 50 nm in diameter, icosahedral in shape, and coated with a lipid envelope [

22]. The genome is approximately 11 kb and it is flanked by two untranslated regions (UTR). The UTR regions play a crucial role in viral replication and immune modulation [

23], while the coding region is translated into a single polyprotein that is processed into three structural proteins and seven non-structural proteins. The three structural proteins (the capsid, membrane and envelope proteins) organize the virion particle, encapsulate the genome and mediates virion binding and fusion to host cell [

3]. The seven non-structural proteins (NS1, NS2A, NS2B, NS3, NS4A, NS4B, NS5) constitute the RNA replication machinery and play an important role in evading the host immune system [

24,

25]. As already mentioned, one of the key components in causing explosive outbreaks is the introduction, substitution, as well as co-circulation of multiple dengue serotypes in endemic or naive regions. It is therefore essential to identify and closely monitor the viral serotypes that are in circulation. The identification of dengue serotypes can be achieved through molecular analysis, with the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) being the most used method. A number of RT-qPCR methods have been developed based on the serotype-specific amplification. Consequently, four distinct reactions are required for viral typing [

26,

27,

28,

29]. Methods that allow simultaneous detection and characterization of the four serotypes in a single reaction have been described; however, they are contingent upon the utilization of multiple oligonucleotides within the same reaction or were conceptualized based on a limited number of dengue genomes available at the time, which are not representative of the current global dengue virus population [

30,

31].

Here, we describe a novel, sensitive, and specific real time RT-qPCR assay for the simultaneous detection and serotyping of dengue virus. The assay was developed through the analysis of an extensive dataset of dengue virus genomes enabling the design of a single pair of primers and four serotype-specific probes that are virtually representative of all circulating dengue genomes to date. Furthermore, the four serotyping probes may be replaced with a single generic probe resulting in a more sensitive pan-dengue Real Time RT-qPCR.

Finally, to provide diagnostic value, four serotype-specific RT-qPCR assays targeting the 3′ genome region were developed.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bioinformatic Analysis

All dengue complete genomes available in Bacterial and Viral Bioinformatics Resource Center (BV-BRC) database as of March 2025 were retrieved. All genomes were aligned by MAFFT (v7.520) [

32]. Oligonucleotides were designed by Primer 3 [

33]. Phylogenetic trees were inferred using the Maximum Likelihood (ML) method implemented in IQ-TREE [

34]. Two trees were built from the entire dataset; one based on whole-genome sequences and the other on the 27-bp region covered by the probes. The best-fit substitution models were selected with Model Finder [

35] and were GTR+F+I+G4 for the first tree and TIM2e+ASC+G4 for the second. Branch support was estimated using SH-aLRT [

36]. The images of the phylogenetic trees were edited with MEGA (

https://www.megasoftware.net/) and with Draw (

https://it.libreoffice.org/scopri/draw).The Dengue genotype was assessed according to Fonseca

et al. [

37]. Alignment visualization and further bioinformatic analysis were carried out by means of UGENE [

38].

2.2. Cell Culture, Virus Strains, RNA Extraction and Samples

Two dengue strains (DENV-1 and DENV-2) available in our institute were isolated in a previously epidemiological investigation [

39] and propagated in cell culture. The resulting genomic RNA was used as a template in the Real Time RT-qPCR setup.

The Vero E6 cell line, provided by Sigma-Aldrich, was cultured in Eagle’s minimal essential medium (MEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 100 U/ml penicillin, and 200 μg/ml streptomycin, in the presence of 5% CO₂. The two viral strains were propagated in 2% FCS until 80% of cellular lysis was observed. The collected supernatant underwent to nucleic acid extraction.

All RNA extractions were carried out by QIAamp Viral RNAMini Kit (Qiagen) or by Maxwell®® 16 Viral Total Nucleic Acid Purification Kit (Promega) according to manufacturer’s instructions.

All the novel methods were tested on three panels of clinically characterized samples, for a total of 30 samples. The first panel was provided by the European network EVD-LabNet (Emerging Viral Diseases-Expert Laboratory Network) during the External Quality Assurance on molecular detection of arboviruses [

40]. The panel consisted of 12 samples of which four spiked with the four dengue serotypes. The second panel consisted of 16 clinical samples provided by the Italian National Institute of Health and the third included 10 samples collected in 2012 and analyzed in a previous study [

39]. Other genomes (tick-borne encephalitis virus, TBEV; usutu virus, USUV; zika virus, ZIKA; west nile virus lineage 1, WNVL1; west nile virus lineage 2, WNVL2; japanese encephalitis virus, JEV; chikungunya virus, CHKV; Plasmodium falciparum and plasmodium ovale), available in our institute, were tested to further asses the specificity of the novel method. All viruses were cultured in biosafety level 3 laboratory and inactivated at 56 ◦ C for 1 h.

2.3. Multicolor Real-Time RT-qPCR Targeting the 5′ UTR Region

The multicolor RT-qPCR was set up in a final volume of 20 μl using the TaqPath 1-Step Multiplex Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific), with 1 μM of forward and reverse primers, 0.2 μM of probe for Dengue serotypes 1, 2, and 3; 0.3 μM of probe for Dengue serotype 4 and 4 μl of genomic RNA. Primers and probes are listed in

Table 1. The reaction was performed on QuantStudio™ 5 Real-Time PCR System instruments (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The amplification program included an incubation step at 25 °C for 5 minutes for Uracil-DNA Glycosylase (UDG) treatment, a reverse transcription at 60 °C for 10 min followed by 95 °C for 2 min and then 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 58 °C for 1 min (extension, acquisition step).

The generic pan-dengue RT-qPCR was assembled as described above, using a concentration of 0.2 μM for the blocked probe. The amplification program differed in the extension/acquisition step which was performed at 60 °C.

The probes labeled with proprietary dyes (FAM, VIC, ABY, and CY5) were synthesized by Thermo Fisher Scientific, while all other oligonucleotides were synthesized by Eurofins Genomics (

https://eurofinsgenomics.eu/).

2.4. Preparation of Synthetic Dengue RNA Standards

To assess the analytical performance of the novel method, the fragments resulting from the amplification of the four dengue serotypes were cloned to produce four synthetic RNA standards. The oligonucleotides and restriction enzymes used for the amplification and cloning of the four fragments are listed in

Supplementary Table 1.

The four targets were reverse transcribed and amplified using the SuperScript™ III One-Step RT-PCR System with the Platinum®® Taq DNA Polymerase kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The reactions were set up in a final volume of 50 μl, with 0.5 μM of each serotype-specific primer pair and 4 μl of genomic RNA. The amplification program was the same for all reactions and consisted of 60 °C for 5 min, reverse transcription at 50 °C for 30 min, followed by 94 °C for 2 min and 10 cycles of 94 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 30 s (ΔT -0.5 °C per cycle), and 68 °C for 1 min; then 30 cycles of 94 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 68 °C for 1 min. The PCR products were visualized on a 2% agarose gel stained with Midori Green (NIPPON Genetics), purified using spin columns (Macherey-Nagel), and cloned into the pRSETC vector using the T4 ligase enzyme (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Plasmid DNA obtained from transformed One Shot™ TOP10 Competent Cells (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was purified with the NucleoSpin Plasmid Minikit (Macherey-Nagel), and the presence of the desired insert was confirmed by PCR and sequencing analysis using the CEQ 8000 instrument, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Beckman Coulter). The four plasmids were linearized and transcribed using the Riboprobe®® In Vitro Transcription System (Promega). The reactions were subjected to DNase digestion and purified using RNeasy Kits (Qiagen), with a further in-column DNase digestion. The synthetic RNAs were quantified using a NanoDrop™ 8000 Spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher), a Quantus™ Fluorometer (Promega), and a TapeStation instrument (Agilent Technologies). The RNA copy number was estimated using Avogadro’s formula: RNA (ng) * (6.02 × 10²³) / (length * 1 × 10⁹ * 340).

2.5. Analytical Performance

To assess the analytical performance of the novel methods, six serial tenfold dilutions of titrated synthetic RNA (from 10

7 to 10

2 copies/reaction) from each dengue serotype, performed in triplicate, were used to obtain the standard curves. The repeatability of the test was verified by running the experiment multiple times under the same conditions. To assess the specificity of the method, genomes from other

Flavivirus species and additional potential cross-reactive genomes were analyzed. The limit of detection (LOD) of the assays was estimated by analyzing eight replicates of twelve 1:2 serial dilutions, with the appropriate amount of synthetic RNA selected based on the analysis of the standard curves. The results were subjected to probit regression analysis using Minitab software (

www.minitab.com).

The methods were tested on three panels of clinically characterized samples.

2.6. Singleplex Real-Time RT-qPCR Targeting the 3′ Genomic Region

The four serotype-specific singleplex RT-qPCR reactions were set up in a final volume of 20 μl using the TaqPath 1-Step Multiplex Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 4 μl of genomic RNA, 1 μM of serotype-specific forward and reverse primers, 0.3 μM of probe for dengue serotypes 1 and 2, and 0.2 μM of probe for dengue serotype 3 and 4. Primers and probes are listed in

Table 2. The reactions were performed on QuantStudio™ 5 Real-Time PCR System instruments (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The amplification program included an incubation step at 25 °C for 5 minutes for Uracil-DNA Glycosylase (UDG) treatment, a reverse transcription at 60 °C for 10 min followed by 95 °C for 2 min and then 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 1 min (extension, acquisition step).

The four singleplex assays were evaluated on the three panels of clinically characterized samples and their results were compared with those obtained using the multicolor method.

3. Results

3.1. Sequences Alignment and Oligonucleotides Design

The raw dataset obtained from BV-BCR was preliminarily aligned. The analysis revealed that some modified, cloned, or attenuated dengue genome strains showed poor homology with the alignment and were therefore removed from the dataset. The resulting cleaned dataset included 7,936 full genomes, of which 3,337 belonged to the DENV-1 serotype, 2,180 to DENV-2, 1,645 to DENV-3, and 774 to DENV-4. All genomes are listed in

Supplementary Table 2.

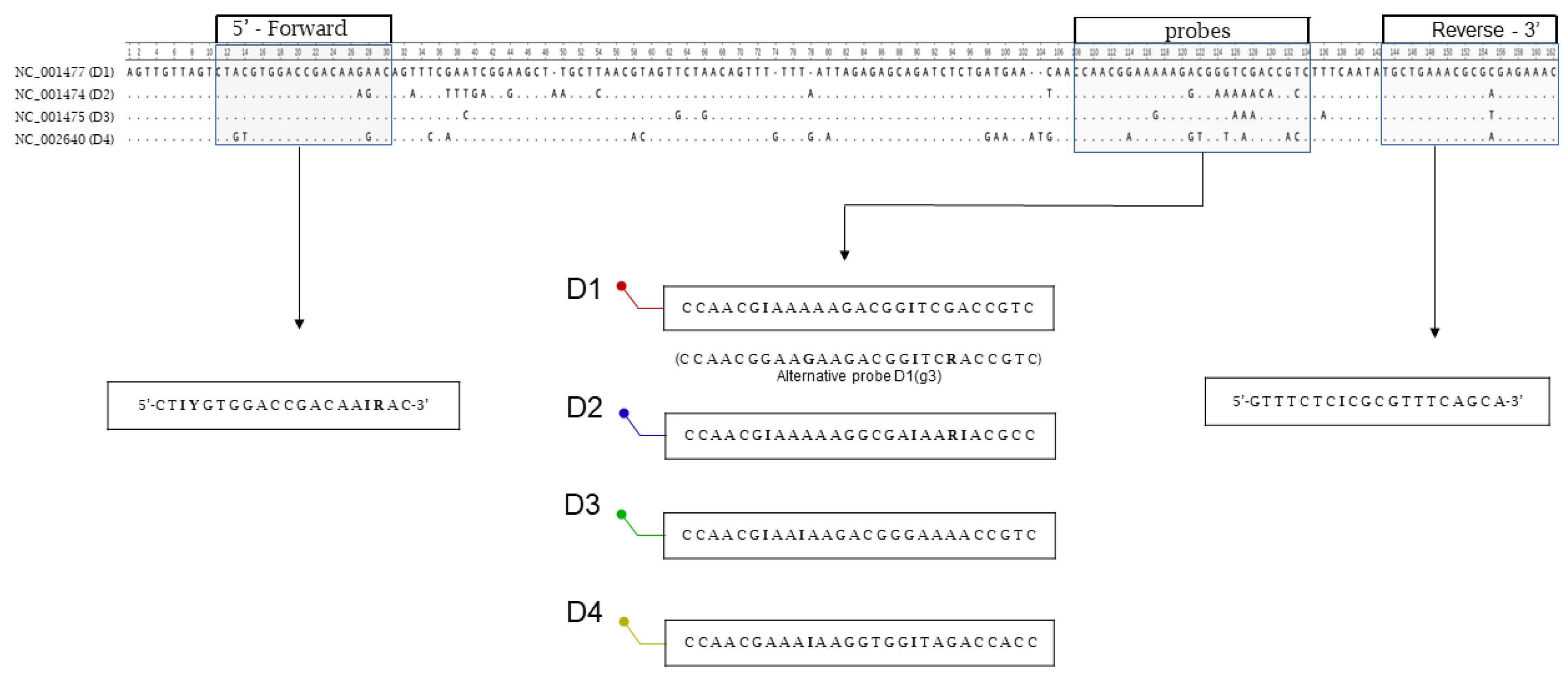

A preliminary alignment of the four dengue reference genomes showed that the two untranslated regions (UTRs) flanking the viral genomes were the most conserved. The 5′ UTR region was selected for oligonucleotide design. In silico analysis identified a primer pair yielding a 147-bp PCR fragment spanning positions 11 to 157 (a.n. NC_001477, DENV-1). The primer pair targets two 20-bp regions of low variability among the four serotypes, while the probes lie in a more variable 27-bp region (

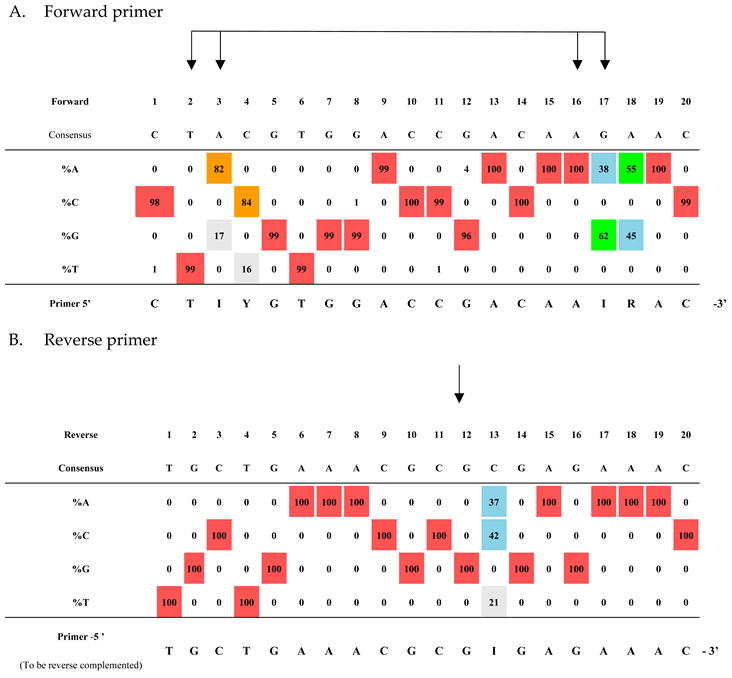

Figure 1).

Next, the conservation of the regions covered by the primers was analyzed across the fully aligned dataset. As shown in

Table 3, the two grid profiles resulting from the alignment analysis revealed four variable positions in the forward primer (panel A) and one variable position in the reverse primer (panel B). The primer sequences were modified or degenerated accordingly to accommodate all variations. It should be noted that variations equal to or below 1% were not taken into consideration. Moreover, due to the absence of the first bases in many genomes, the entire forward primer sequence is representative of 2,563 genomes out of 7,936.

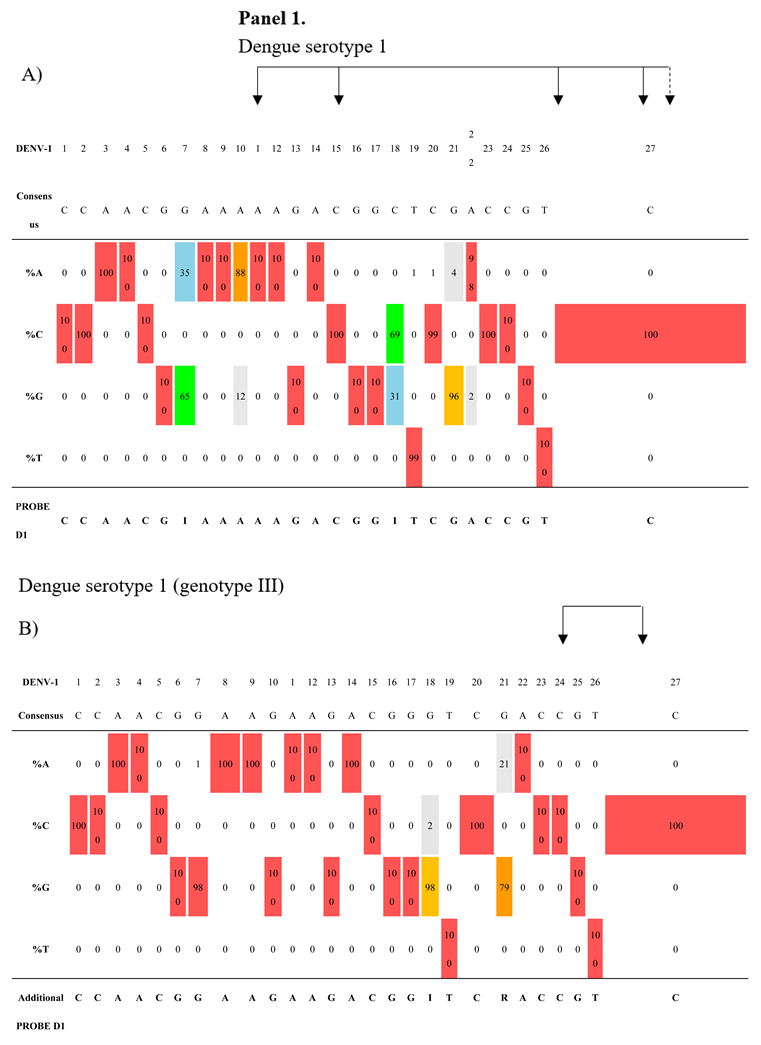

Conversely, the region covered by the probes was analyzed separately for each of the four serotype-specific datasets. As shown in

Table 4 (panels 1–4), each serotype exhibited its own intrinsic variability. The DENV-1 probe was designed with two inosines at positions 7 and 18, covering approximately 88% of the DENV-1 dataset. The remaining 12% carry two variants at positions 10 (A/G) and 21 (G/A). These variants were mainly found (97%) in a cluster of 373 sequences belonging to genotype 3 (

Supplementary Figure S1 and S2), which was responsible for a recent outbreak in Pakistan in 2022 (41). Since further degeneracy of probe 1 resulted in a significant loss of performance, we designed an alternative specific probe for this cluster (

Table 4, Panel 1B).

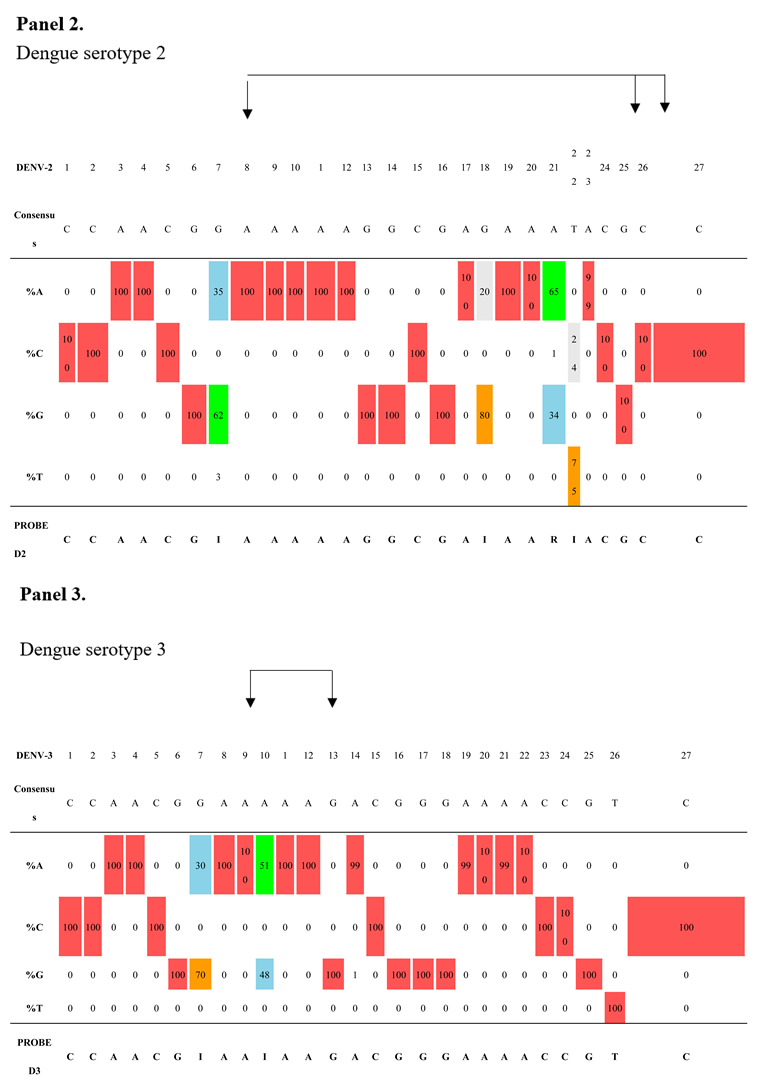

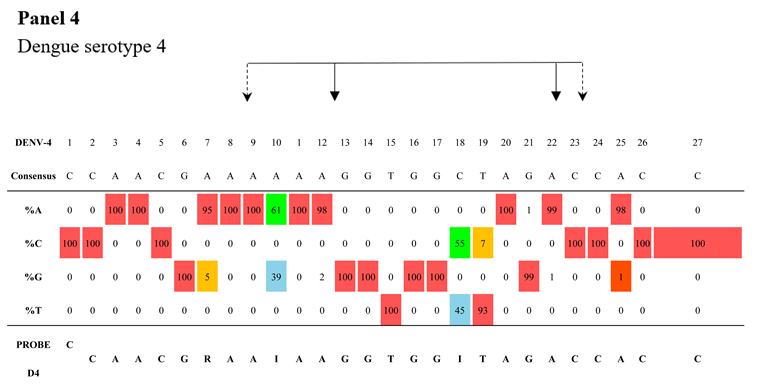

As shown in

Table 4, panels 2–4, the DENV-2-specific probe includes three inosines (positions 7, 18, and 22) and one degenerate base at position 21. The DENV-3 probe includes two inosines (positions 7 and 10), and the DENV-4 probe includes two inosines (positions 10 and 18). These three probes cover their respective complete datasets. It should be noted that two minor variants detected in the region targeted by the DENV-4 probe (position 7: A/G; position 19: T/C) were represented up until 2016 in India and China and then progressively disappeared, as traced through the phylogenetic tree (

Supplementary Figure S3).

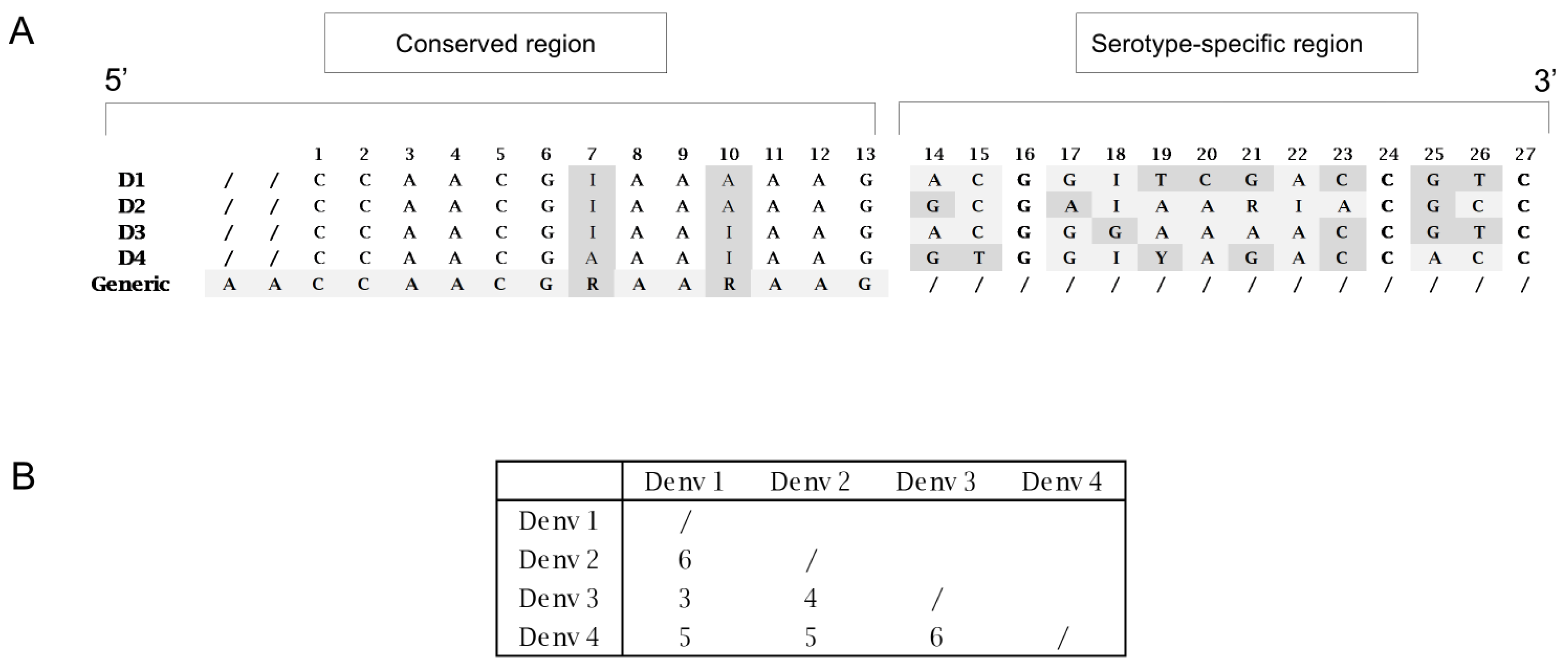

Figure 2, panel A, shows the sequence comparison of the four probes. Each one is 27 bp in length and shares a conserved 13-nucleotide region at the 5′ end (incorporating appropriate degeneracies), whereas the 3′ region, consisting of 14 nucleotides, is serotype-specific.

Figure 2, panel B, illustrates the nucleotide variability among the four probes within this 3′ region.

The conserved 13-nucleotide sequence at the 5′ end, extended with two additional fully conserved nucleotides, was used to design a generic probe, modified with a minor groove-binder (MGB) molecule to enable the detection of all serotypes.

The four serotype-specific RT-qPCR targeting the 3′ regions (

Table 2) were designed with a similar approach above described. First, the oligonucleotides were built on the reference genomes, then the conservation of the oligonucleotide sequences and the choice of the degeneracy to introduce, was evaluated through the grid profile analysis of each serotype-specific dataset (

Supplementary Table 3).

3.2. Phylogenetic Analysis

The discriminatory power of the 27-bp probe-target sequence among the four serotypes was preliminarily assessed in silico through phylogenetic analysis. Two phylogenetic trees were built in order to assess whether they produced equivalent topologies, the first using the full genomes and the second using the partial dataset consisting of the 27-bp sequences covered by the probes, extracted from the full alignment. As shown in

Supplementary Figure S1 and S4, the maximum likelihood analysis yielded distinct clades in both the analysis. The tree topology was supported by aLRT SH-like values, and all strains belonging to the same serotype clustered together in both trees.

3.3. Specificity, Sensibility and Intra-Laboratory Repeatability of the Novel Method

Supplementary Figure S5 shows the sequencing analysis of the four cloned vectors, focusing on the serotype-specific sequences.

The analytical performance of the serotyping multicolor method was first assessed by analyzing the four synthetic RNAs. The methods were first tested for specificity by challenging each of the four probes with their respective heterologous synthetic RNAs. No cross-reactivity or fluorescence cross-talk was observed, even when limiting dilutions of each target (down to 10² copies/reaction) were tested in the presence of high concentrations (up to 10⁹ copies/reaction) of a mixture of three heterologous targets.

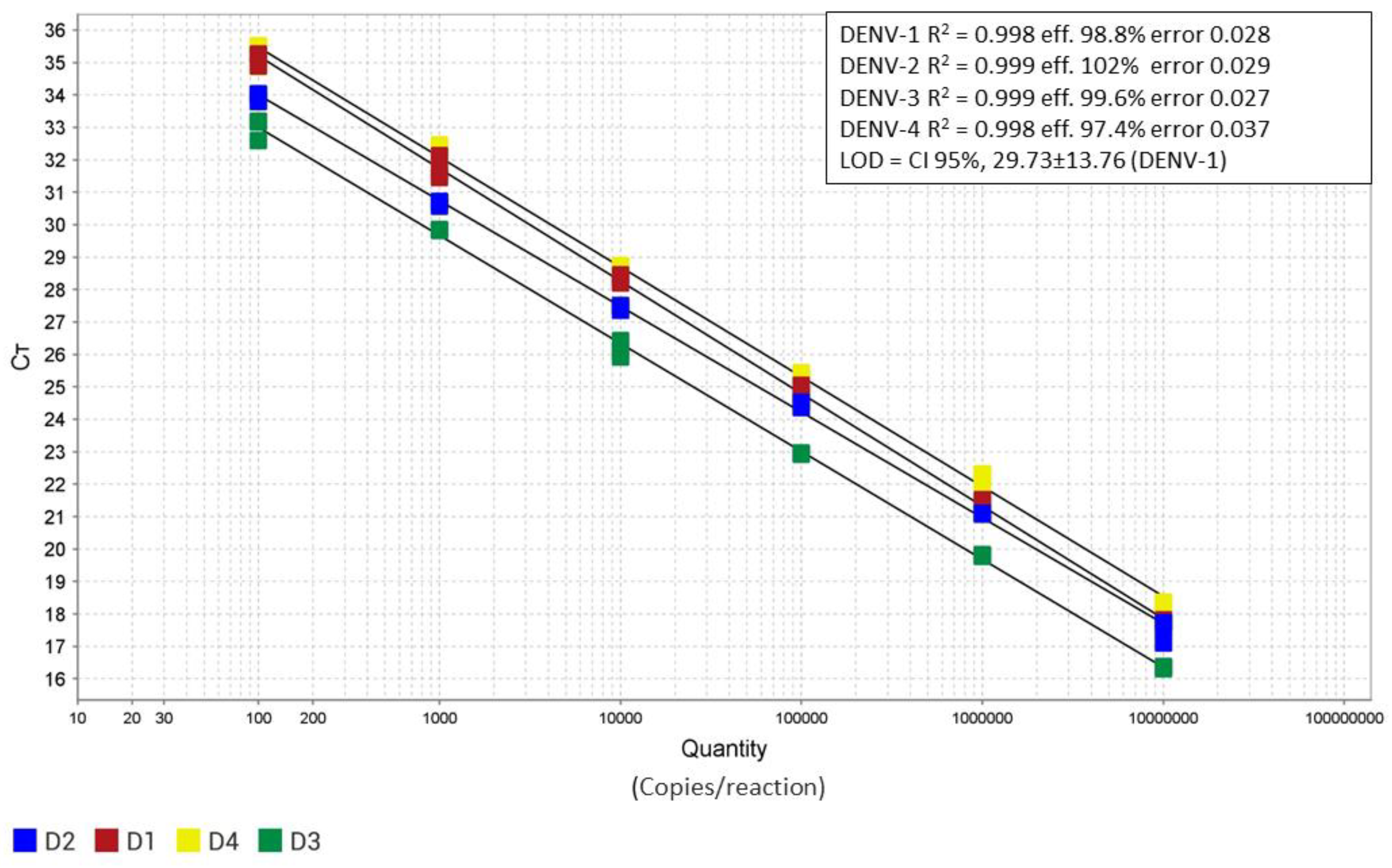

Figure 3 shows the four standard curves obtained by analyzing the dilutions of titrated synthetic RNAs in triplicate. The reaction exhibited optimal linearity (R² = 0.99) within the dilution range of 10⁷ to 10² copies per reaction. A slightly lower efficiency was observed for serotype 4 (efficiency % = 97.4). The limit of detection (LOD) of the assay, estimated for dengue serotype 1, was 29 copies/reaction (CI 95%,29.73±13.76) while the 50% LOD was 14 copies reaction (CI 95%, 14,8 ± 5,61).

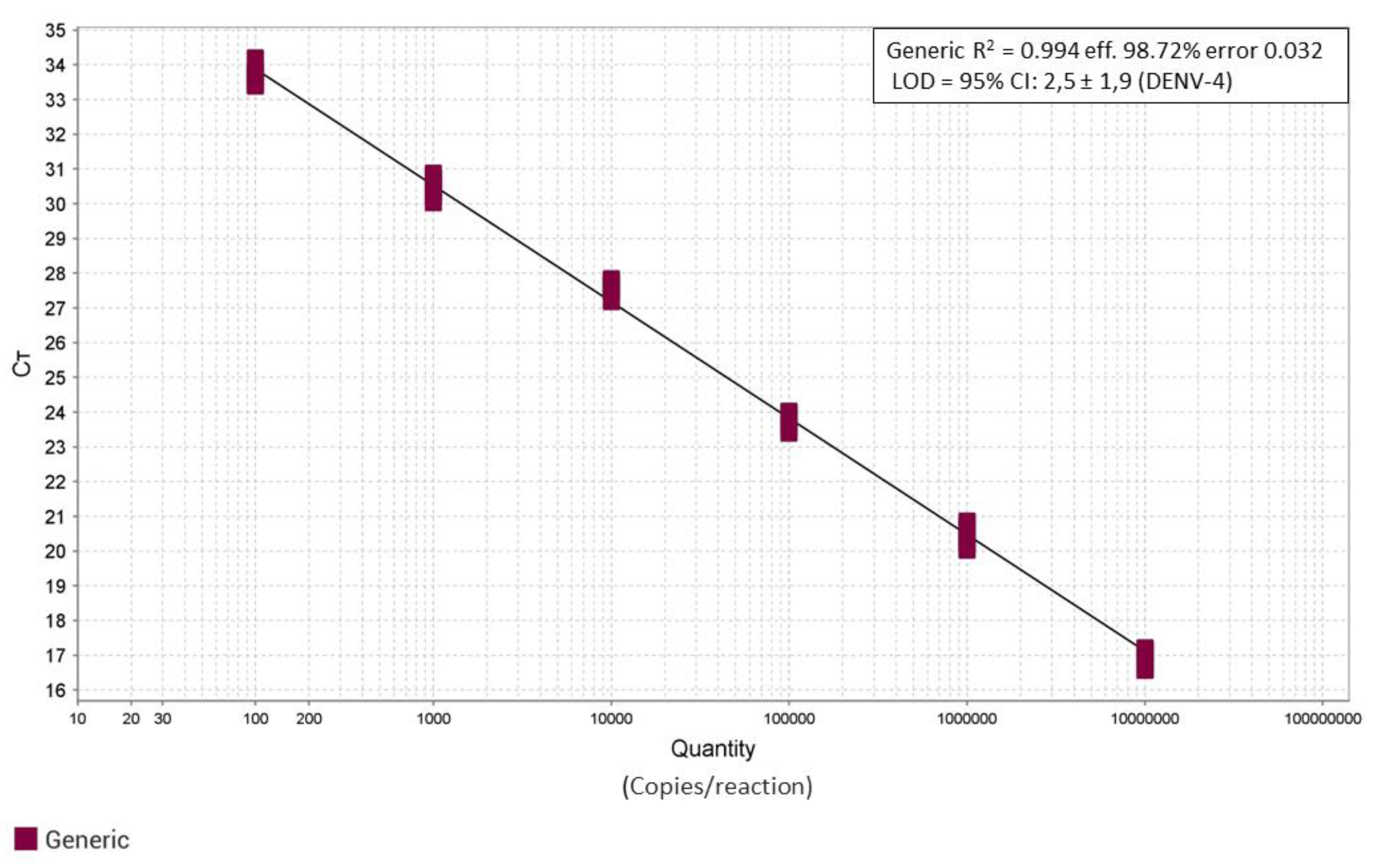

Similarly, the analytical performance of the pan-dengue PCR assay using the generic blocked probe was assessed by analyzing serial dilutions of the four titrated synthetic RNAs. Since the four synthetic RNAs showed comparable PCR performance and crossing threshold (Ct) values, they were analyzed as a single equivalent template. A single standard curve was thus generated by analyzing each RNA dilution in 12 replicate series. As shown in

Figure 4, the reaction exhibited consistent performance across the four synthetic positive controls (R² = 0.994; efficiency = 98.7%; error = 0.032). The limit of detection (LOD) was estimated for serotype 4 and corresponded to 2,7 copies per reaction (95% CI: 2,5 ± 1,9), while the 50% LOD was 1,2 copies per reaction (95% CI: 1,2 ± 0,78).

The reliability and specificity of the two methods were evaluated by analyzing three panels of clinically characterized samples, for a total of 30 samples. All samples were correctly detected, and no cross-reactivity was observed with related Flavivirus genomes or additional potential cross-reactive genomes available in our institute (TBEV, USUV, ZIKV, WNV L1, WNV L2, JEV, CHIKV, P. falciparum, and P. ovale).

The same clinical samples were used to test the four serotype-specific RT-qPCR designed on the 3′genome region. The results agreed with the multicolor method (

Supplementary Table 4) and in several instances revealed better performance (

Supplementary Figure S6).

4. Discussion

Dengue is a growing global health threat [

42]. Since its first documented outbreak in Southeast Asia, the virus has spread westward through the Middle East, Africa and to the Americas [

43]. Southeast Asia has historically experienced the highest health and economic burden from outbreaks, while other tropical regions have faced recurrent waves [

44]. In recent decades, the interaction of environmental, ecological, and human factors has facilitated the spread of competent vectors, leading to a global increase in disease incidence [

45]. While the Americas have recently experienced a dramatic epidemiological shift [

19], alarming signals are now emerging from the European continent. Dengue is not considered endemic in mainland Europe, and nearly all detected infections were associated with travel to endemic regions until 2010. Since then, autochthonous infections have steadily increased. In France, the first two locally acquired dengue cases were reported in 2010 [

46], and numbers have continued to rise, reaching 85 in 2024 [

47]. Spain has reported fewer cases over the same period [

48], whereas Italy has shown a marked increase in local transmission, with 82 autochthonous cases out of 327 totals in 2023, and 213 out of 696 in 2024 [

49,

50]. It is evident that the high incidence of the disease in endemic areas leads to an increase in imported cases, and the high density of the secondary vector (

Aedes albopictus) in some regions of Europe contributes to a growing number of local transmission chains. The repeated occurrence of these events could increase the likelihood of viral endemicity becoming established. Experimental data reveal that even a few transmission cycles may favor the selection of DENV strains adapted to local vectors [

51,

52]. The vector itself has already been shown to be able to overwinter in Central Europe [

53], even under low-temperature conditions (−6 °C to −10 °C) [

54]. Additionally, the ability of the vector to complete its life cycle (homodynamicity) has already been observed in Southern Europe [

55]. In such a scenario, the potential establishment of viral endemicity within a short time frame in Central and Southern Europe represents a realistic concern [

56].

Rapid identification and contextual serological typing of circulating DENV strains represent important tools to strengthen surveillance systems and to enable the immediate implementation of control measures. The described multicolor real-time RT-PCR method presents several advantages: the oligonucleotides have been designed based on a database virtually representative of all dengue genomes circulating to date; the single detection and serotyping one-tube reaction requires a simple wet setup with two primers and four probes, and the availability of a fifth alternative probe (DENV-1B) allows for the detection of all genotypes of Dengue 1, if needed. The method has been successfully tested to simultaneously detect multiple targets (co-infections), moreover, all wild-type full genomes (43 genomes collected from mosquitoes) were retained in the database, and only a few modified or cloned genomes were excluded.

The performance of the novel method supports its use in surveillance studies as well as in clinical settings. The sensitivity, estimated at 29 copies per reaction, enables detection of the virus during the pre-febrile and critical phase of the disease. When needed, the generic pan-detection probe can detect 2 copies per reaction, though this comes at the cost of losing serotyping information.

However, to gain diagnostic value, a secondary confirmatory amplification target is required. Although other published methods could address this need, we chose to design four additional serotype-specific amplification targets taking advantage of the highly informative genomic database. Three serotype-specific amplicons were designed on the 3′ UTR (DENV-2, DENV-3, DENV-4) and one in the 3′ terminal region of the NS5 (DENV-1). The conservation of the primers and probes was in silico validated using the same approach described for the multicolor PCR. It should be noted that, with the exception of the DENV-1 serotype, the conservation of primers and probes was evaluated on a smaller number of complete genomes than in the multicolor approach, due to the absence of the target sequences in several genomes.

The four single-plex methods were tested on already typed clinical samples, and the results agreed with the multicolor analysis method. However, several analyses with the single-plex assay targeting the 3′ genomic region detected the samples at a lower crossing threshold (

Supplementary Table 4 and Supplementary Figure S6). These results are most likely not due to a higher sensitivity of the four single-plex assays, but rather to the higher availability of the RNA amplicon target in the 3′ region. It is well established that the 3′UTR of the flavivirus genome is protected from degradation by the host cell exonuclease Xrn1, a process that results in the formation of subgenomic flaviviral RNAs (sfRNAs) [

57]. In

Supplementary Figure S7, the amplification plots obtained from the multicolor and the 3′ UTR methods on one clinical sample are shown, along with titrated positive controls to support this interpretation.

This study has one main limitation, namely the low number of clinical samples available for in-depth testing of the procedure. Nevertheless, the database used to design the method is highly representative and the likelihood that additional nucleotide variants in the analyzed genomic region are not included is reasonably low. Evidence indicates that the flaviviral 5′ and 3′ UTR regions interact through base pairing, which promotes genome cyclization and, consequently, viral replication [

58,

59,

60]. Only a few variants are tolerated in these regions, making it unlikely that they are absent from our database. An additional limitation is the lack of testing of the alternative probe DENV-1B, due to the absence of the specific strains. This probe includes one degenerate base (bp 21 = R) but one fewer modification compared to the probe DENV-1, which is an inosine replaced with a “G” (bp 7 I/G) (

Table 4). Overall, the stability of the alternative probe DENV-1B should be higher than that of the probe DENV-1.

We are confident that the described procedures represent a further advancement in dengue detection and characterization and will prove useful in surveillance, epidemiological, and clinical studies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, GF, FM and FL; Methodology, GF, FM, EL; Validation, GF, FM, EL, RDS; Formal Analysis: GF; Investigation: GF, FM, EL; Resources: GF, FM, EL, GV, GM, GP, FL, RDS; Data Curation, GF, FM; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, GF; Review & Editing, GF, FM, EL, GV, GM, RDS, GP, FL; Visualization, GF, FM; Supervision, GF and FL; Project Administration, GF, FL. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by the Italian Ministry of Defense.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Colonel Fabrizio Frisoni and Lieutenant Colonel Leonardo Di Palma for their valuable logistical support. Emiliana Luciano is recipient of the Tor Vergata PhD program in Tissue Engineering and Remodeling Biotechnologies for Body Functions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Messina, JP; Brady, OJ; Golding, N; Kraemer, MUG; Wint, GRW; Ray, SE; Pigott, DM; Shearer, FM; Johnson, K; Earl, L; Marczak, LB; Shirude, S; Davis Weaver, N; Gilbert, M; Velayudhan, R; Jones, P; Jaenisch, T; Scott, TW; Reiner, RC, Jr.; Hay, SI. The current and future global distribution and population at risk of dengue. Nat Microbiol 2019, 4(9), 1508–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, MG; Harris, E. Dengue. Lancet 2015, 385(9966), 453–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harapan, H; Michie, A; Sasmono, RT; Imrie, A. Dengue: A Minireview. Viruses 2020, 12(8), 829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzman, MG; Gubler, DJ; Izquierdo, A; Martinez, E; Halstead, SB. Dengue infection. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016, 2, 16055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustafa, MS; Rasotgi, V; Jain, S; Gupta, V. Discovery of fifth serotype of dengue virus (DENV-5): A new public health dilemma in dengue control. Med J Armed Forces India 2015, 71(1), 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gubler, DJ. Dengue and dengue hemorrhagic fever. Clin Microbiol Rev 1998, 11(3), 480–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, EC; Twiddy, SS. The origin, emergence and evolutionary genetics of dengue virus. Infect Genet Evol 2003, 3(1), 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, CP; Farrar, JJ; Nguyen, vV; Wills, B. Dengue. N Engl J Med 2012, 366(15), 1423–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, N; Balmaseda, A; Coelho, IC; Dimaano, E; Hien, TT; Hung, NT; Jänisch, T; Kroeger, A; Lum, LC; Martinez, E; Siqueira, JB; Thuy, TT; Villalobos, I; Villegas, E; Wills, B. European Union, World Health Organization (WHO-TDR) supported DENCO Study Group. Multicentre prospective study on dengue classification in four South-east Asian and three Latin American countries. Trop Med Int Health 2011, 16(8), 936–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitehorn, J; Simmons, CP. The pathogenesis of dengue. Vaccine 2011, 29(42), 7221–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamel, R; Surasombatpattana, P; Wichit, S; Dauvé, A; Donato, C; Pompon, J; Vijaykrishna, D; Liegeois, F; Vargas, RM; Luplertlop, N; Missé, D. Phylogenetic analysis revealed the co-circulation of four dengue virus serotypes in Southern Thailand. PLoS One 2019, 14(8), e0221179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Ende, J; Nipaz, V; Carrazco-Montalvo, A; Trueba, G; Grobusch, MP; Coloma, J. Cocirculation of 4 Dengue Virus Serotypes, Putumayo Amazon Basin, 2023-2024. Emerg Infect Dis 2025, 31(1), 202–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narayan, R; Tripathi, S. Intrinsic ADE: The Dark Side of Antibody Dependent Enhancement During Dengue Infection. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2020, 10, 580096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanam, A; Gutiérrez-Barbosa, H; Lyke, KE; Chua, JV. Immune-Mediated Pathogenesis in Dengue Virus Infection. Viruses 2022, 14(11), 2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquito-borne hemorrhagic fevers of South-East Asia and the Western Pacific. Bull World Health Organ. 1966, 35(1), 17–33. [PubMed]

- HAMMON, WM; RUDNICK, A; SATHER, GE. Viruses associated with epidemic hemorrhagic fevers of the Philippines and Thailand. Science 1960, 131(3407), 1102–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubler, DJ; Clark, GG. Dengue/dengue hemorrhagic fever: the emergence of a global health problem. Emerg Infect Dis 1995, 1(2), 55–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brathwaite Dick, O; San Martín, JL; Montoya, RH; del Diego, J; Zambrano, B; Dayan, GH. The history of dengue outbreaks in the Americas. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012, 87(4), 584–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Disease Outbreak News; Dengue – Global Situation. 30 May 2024. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-outbreak-news/item/2023-DON518.

- Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/documents/dengue-epidemiological-situation-region-americas-epidemiological-week-20-2025.

- Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dengue-and-severe-dengue?

- Kuhn, RJ; Zhang, W; Rossmann, MG; Pletnev, SV; Corver, J; Lenches, E; Jones, CT; Mukhopadhyay, S; Chipman, PR; Strauss, EG; Baker, TS; Strauss, JH. Structure of dengue virus: implications for flavivirus organization, maturation, and fusion. Cell 2002, 108(5), 717–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gebhard, LG; Filomatori, CV; Gamarnik, AV. Functional RNA elements in the dengue virus genome. Viruses 2011, 3(9), 1739–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lescar, J; Soh, S; Lee, LT; Vasudevan, SG; Kang, C; Lim, SP. The Dengue Virus Replication Complex: From RNA Replication to Protein-Protein Interactions to Evasion of Innate Immunity. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018, 1062, 115–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tremblay, N; Freppel, W; Sow, AA; Chatel-Chaix, L. The Interplay between Dengue Virus and the Human Innate Immune System: A Game of Hide and Seek. Vaccines (Basel) 2019, 7(4), 145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leparc-Goffart, I; Baragatti, M; Temmam, S; Tuiskunen, A; Moureau, G; Charrel, R; de Lamballerie, X. Development and validation of real-time one-step reverse transcription-PCR for the detection and typing of dengue viruses. J Clin Virol 2009, 45(1), 61–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huhtamo, E; Hasu, E; Uzcátegui, NY; Erra, E; Nikkari, S; Kantele, A; Vapalahti, O; Piiparinen, H. Early diagnosis of dengue in travelers: comparison of a novel real-time RT-PCR, NS1 antigen detection and serology. J Clin Virol 2010, 47(1), 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, C; Palacios, G; Jabado, O; Reyes, N; Niedrig, M; Gascón, J; Cabrerizo, M; Lipkin, WI; Tenorio, A. Use of a short fragment of the C-terminal E gene for detection and characterization of two new lineages of dengue virus 1 in India. J Clin Microbiol 2006, 44(4), 1519–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callahan, JD; Wu, SJ; Dion-Schultz, A; Mangold, BE; Peruski, LF; Watts, DM; Porter, KR; Murphy, GR; Suharyono, W; King, CC; Hayes, CG; Temenak, JJ. Development and evaluation of serotype- and group-specific fluorogenic reverse transcriptase PCR (TaqMan) assays for dengue virus. J Clin Microbiol 2001, 39(11), 4119–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songjaeng, A; Thiemmeca, S; Mairiang, D; Punyadee, N; Kongmanas, K; Hansuealueang, P; Tangthawornchaikul, N; Duangchinda, T; Mongkolsapaya, J; Sriruksa, K; Limpitikul, W; Malasit, P; Avirutnan, P. Development of a Singleplex Real-Time Reverse Transcriptase PCR Assay for Pan-Dengue Virus Detection and Quantification. Viruses 2022, 14(6), 1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waggoner, JJ; Abeynayake, J; Sahoo, MK; Gresh, L; Tellez, Y; Gonzalez, K; Ballesteros, G; Pierro, AM; Gaibani, P; Guo, FP; Sambri, V; Balmaseda, A; Karunaratne, K; Harris, E; Pinsky, BA. Single-reaction, multiplex, real-time rt-PCR for the detection, quantitation, and serotyping of dengue viruses. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013, 7(4), e2116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katoh, K; Rozewicki, J; Yamada, KD. MAFFT online service: multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief Bioinform 2019, 20(4), 1160–1166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kõressaar, T; Lepamets, M; Kaplinski, L; Raime, K; Andreson, R; Remm, M. Primer3_masker: integrating masking of template sequence with primer design software. Bioinformatics 2018, 34(11), 1937–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, BQ; Schmidt, HA; Chernomor, O; Schrempf, D; Woodhams, MD; von Haeseler, A; Lanfear, R. IQ-TREE 2: New Models and Efficient Methods for Phylogenetic Inference in the Genomic Era. Mol Biol Evol Erratum in: Mol Biol Evol. 2020 Aug 1;37(8):2461. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msaa131. 2020, 37(5), 1530–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalyaanamoorthy, S; Minh, BQ; Wong, TKF; von Haeseler, A; Jermiin, LS. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat Methods 2017, 14(6), 587–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anisimova, M; Gascuel, O. Approximate likelihood-ratio test for branches: A fast, accurate, and powerful alternative. Syst Biol. 2006, 55(4), 539–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, V; Libin, PJK; Theys, K; Faria, NR; Nunes, MRT; Restovic, MI; Freire, M; Giovanetti, M; Cuypers, L; Nowé, A; Abecasis, A; Deforche, K; Santiago, GA; Siqueira, IC; San, EJ; Machado, KCB; Azevedo, V; Filippis, AMB; Cunha, RVD; Pybus, OG; Vandamme, AM; Alcantara, LCJ; de Oliveira, T. A computational method for the identification of Dengue, Zika and Chikungunya virus species and genotypes. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2019, 13(5), e0007231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okonechnikov, K; Golosova, O; Fursov, M; UGENE team. Unipro UGENE: a unified bioinformatics toolkit. Bioinformatics 2012, 28(8), 1166–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezza, G; El-Sawaf, G; Faggioni, G; Vescio, F; Al Ameri, R; De Santis, R; Helaly, G; Pomponi, A; Metwally, D; Fantini, M; Qadi, H; Ciccozzi, M; Lista, F. Co-circulation of Dengue and Chikungunya Viruses, Al Hudaydah, Yemen, 2012. Emerg Infect Dis 2014, 20(8), 1351–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Presser, LD; Baronti, C; Moegling, R; Pezzi, L; Lustig, Y; Gossner, CM; Reusken, CBEM; Charrel, RN; EVD-LabNet. Excellent capability for molecular detection of Aedes-borne dengue, Zika, and chikungunya viruses but with a need for increased capacity for yellow fever and Japanese encephalitis viruses: an external quality assessment in 36 European laboratories. J Clin Microbiol 2025, 63(1), e0091024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umair, M; Haider, SA; Rehman, Z; Jamal, Z; Ali, Q; Hakim, R; Bibi, S; Ikram, A; Salman, M. Genomic Characterization of Dengue Virus Outbreak in 2022 from Pakistan. Vaccines (Basel) 2023, 11(1), 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Z; Zhan, J; Chen, L; Chen, H; Cheng, S. Global, regional, and national dengue burden from 1990 to 2017: A systematic analysis based on the global burden of disease study 2017. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 32, 100712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villabona-Arenas, CJ; Zanotto, PM. Worldwide spread of Dengue virus type 1. PLoS One 2013, 8(5), e62649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stanaway, JD; Shepard, DS; Undurraga, EA; Halasa, YA; Coffeng, LE; Brady, OJ; Hay, SI; Bedi, N; Bensenor, IM; Castañeda-Orjuela, CA; Chuang, TW; Gibney, KB; Memish, ZA; Rafay, A; Ukwaja, KN; Yonemoto, N; Murray, CJL. The global burden of dengue: an analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet Infect Dis 2016, 16(6), 712–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y; Chen, H; Wu, H; Wu, B; Wang, L; Liu, X; Yang, Y; Tan, H; Gao, W. Epidemiological Trends and Age-Period-Cohort Effects on Dengue Incidence Across High-Risk Regions from 1992 to 2021. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2025, 10(6), 173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Ruche, G; Souarès, Y; Armengaud, A; Peloux-Petiot, F; Delaunay, P; Desprès, P; Lenglet, A; Jourdain, F; Leparc-Goffart, I; Charlet, F; Ollier, L; Mantey, K; Mollet, T; Fournier, JP; Torrents, R; Leitmeyer, K; Hilairet, P; Zeller, H; Van Bortel, W; Dejour-Salamanca, D; Grandadam, M; Gastellu-Etchegorry, M. First two autochthonous dengue virus infections in metropolitan France, September 2010. Euro Surveill 2010, 15(39), 19676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arulmukavarathan, A; Gilio, LS; Hedrich, N; Nicholas, N; Reuland, NI; Sheikh, AR; Staub, A; Trüb, FG; Schlagenhauf, P. Dengue in France in 2024 - A year of record numbers of imported and autochthonous cases. New Microbes New Infect. 2024, 62, 101553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrero-Martínez, JM; Sánchez-Ledesma, M; Ramos-Rincón, JM. Imported and autochthonous dengue in Spain. Rev Clin Esp (Barc) 2023, 223(8), 510–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branda, F; Nakase, T; Maruotti, A; Scarpa, F; Ciccozzi, A; Romano, C; Peletto, S; de Filippis, AMB; Alcantara, LCJ; Marcello, A; Ciccozzi, M; Lourenço, J; Giovanetti, M. Dengue virus transmission in Italy: historical trends up to 2023 and a data repository into the future. Sci Data 2024, 11(1), 1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epicentro Istituto Superiore di Sanità. Arbovirosi in Italia (Febbre Dengue. 2025. Available online: https://www.epicentro.iss.it/arbovirosi/dashboard (accessed on 30 July 2025).

- Fortuna, C; Severini, F; Marsili, G; Toma, L; Amendola, A; Venturi, G; Argentini, C; Casale, F; Bernardini, I; Boccolini, D; Fiorentini, C; Hapuarachchi, HC; Montarsi, F; Di Luca, M. Assessing the Risk of Dengue Virus Local Transmission: Study on Vector Competence of Italian Aedes albopictus. Viruses 2024, 16(2), 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellone, R; Lequime, S; Jupille, H; Göertz, GP; Aubry, F; Mousson, L; Piorkowski, G; Yen, PS; Gabiane, G; Vazeille, M; Sakuntabhai, A; Pijlman, GP; de Lamballerie, X; Lambrechts, L; Failloux, AB. Experimental adaptation of dengue virus 1 to Aedes albopictus mosquitoes by in vivo selection. Sci Rep. 2020, 10(1), 18404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pluskota, B; Jöst, A; Augsten, X; Stelzner, L; Ferstl, I; Becker, N. Successful overwintering of Aedes albopictus in Germany. Parasitol Res Erratum in: Parasitol Res. 2016 Aug;115(8):3279. doi: 10.1007/s00436-016-5150-y. 2016, 115(8), 3245–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tippelt, L; Werner, D; Kampen, H. Tolerance of three Aedes albopictus strains (Diptera: Culicidae) from different geographical origins towards winter temperatures under field conditions in northern Germany. PLoS One 2019, 14(7), e0219553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Del Lesto, I; De Liberato, C; Casini, R; Magliano, A; Ermenegildi, A; Romiti, F. Is Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus) going to become homodynamic in Southern Europe in the next decades due to climate change? R Soc Open Sci 2022, 9(12), 220967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ware-Gilmore, F; Jones, MJ; Mejia, AJ; Dennington, NL; Audsley, MD; Hall, MD; Sgrò, CM; Buckley, T; Anand, GS; Jose, J; McGraw, EA. Evolution and adaptation of dengue virus in response to high-temperature passaging in mosquito cells. Virus Evol 2025, 11(1), veaf016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, EG; Moon, SL; Wilusz, J; Kieft, JS. RNA structures that resist degradation by Xrn1 produce a pathogenic Dengue virus RNA. Elife 2014, 3, e01892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Villordo, SM; Gamarnik, AV. Genome cyclization as strategy for flavivirus RNA replication. Virus Res 2009, 139(2), 230–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alvarez, DE; Lodeiro, MF; Ludueña, SJ; Pietrasanta, LI; Gamarnik, AV. Long-range RNA-RNA interactions circularize the dengue virus genome. J Virol 2005, 79(11), 6631–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Robinson, ZE; Pereira, HS; D’Souza, MH; Patel, TR. Structural dynamics of dengue virus UTRs and their cyclization. Biophys J Epub ahead of print. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).