Submitted:

10 December 2025

Posted:

11 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Method

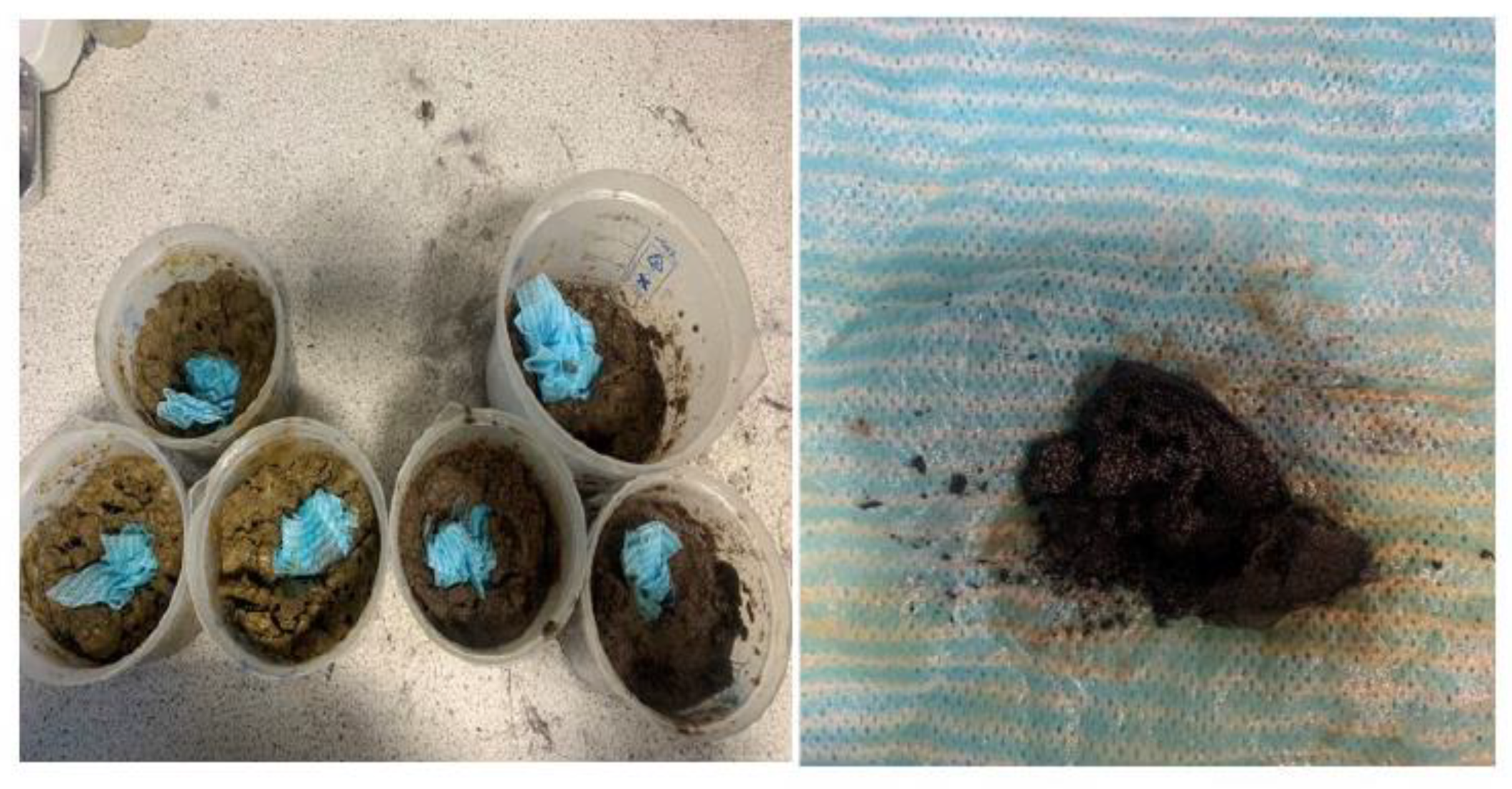

2.1. Preparation of Superhydrophobic and Oleophilic Orange Peels Adsorbent

2.1.1. Physical Modification Process

2.1.2. Chemical Modification Process

2.1.3. Thermal Modification Process

2.1.4. Preparation of Aerogels

2.2. Characterization of Prepared Aerogel

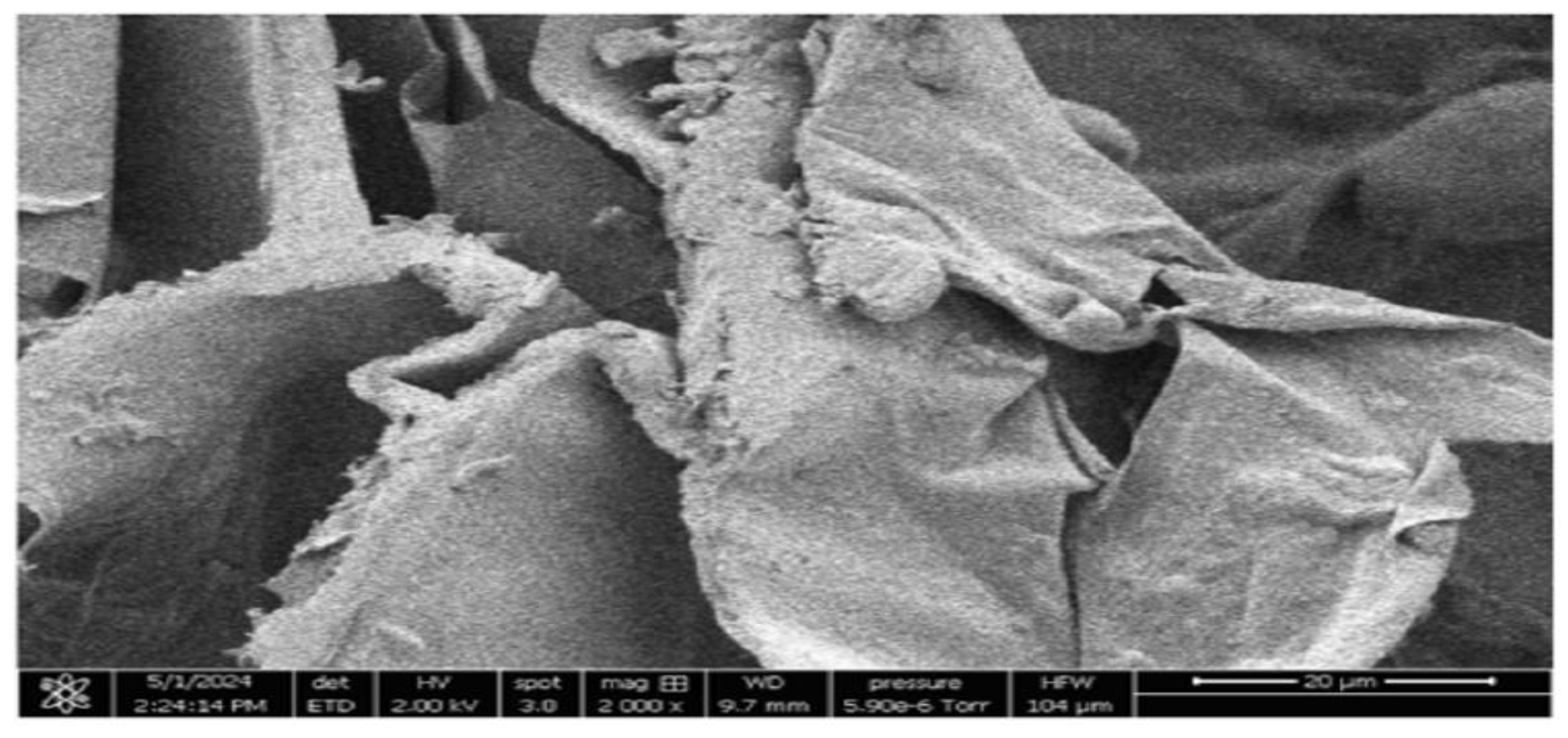

2.2.1. Scanning Electron Microscope

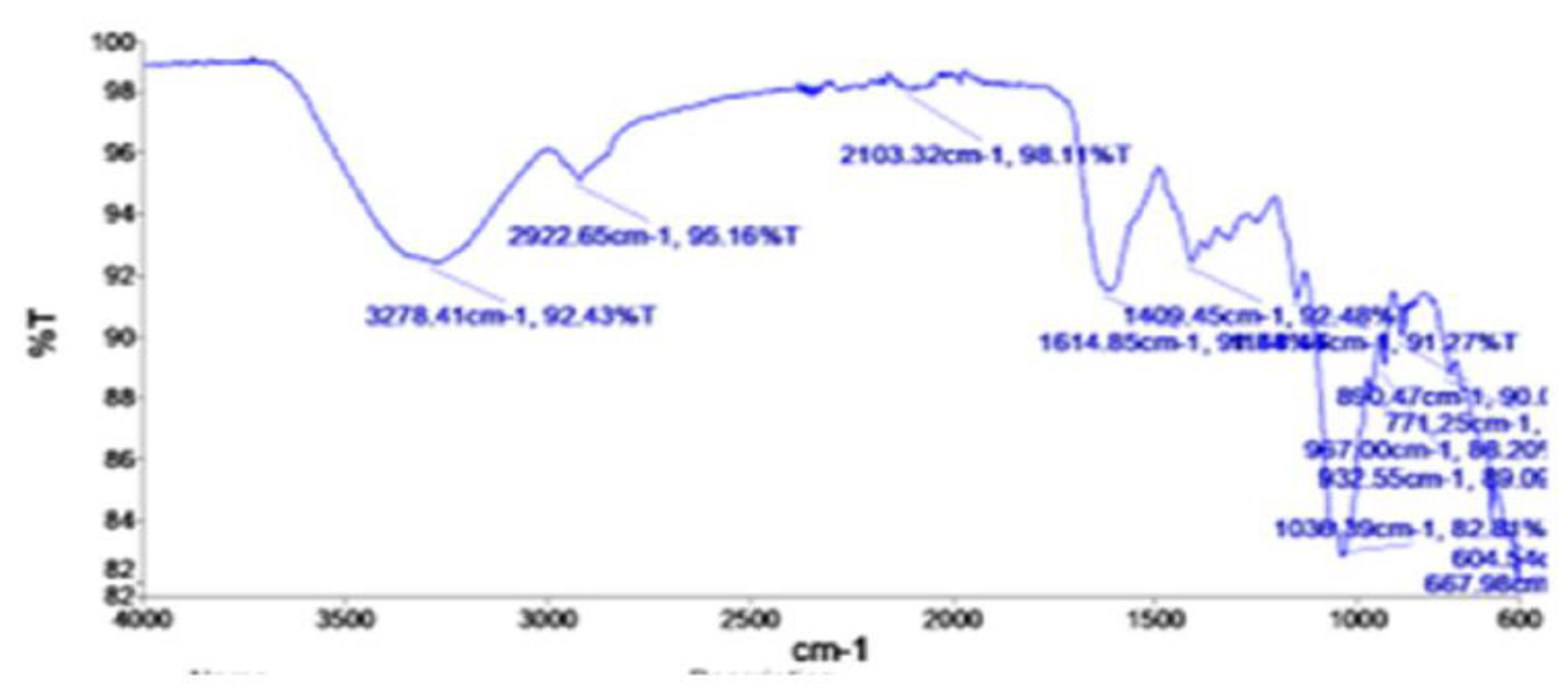

2.2.2. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR)

2.2.3. Surface Area Analysis

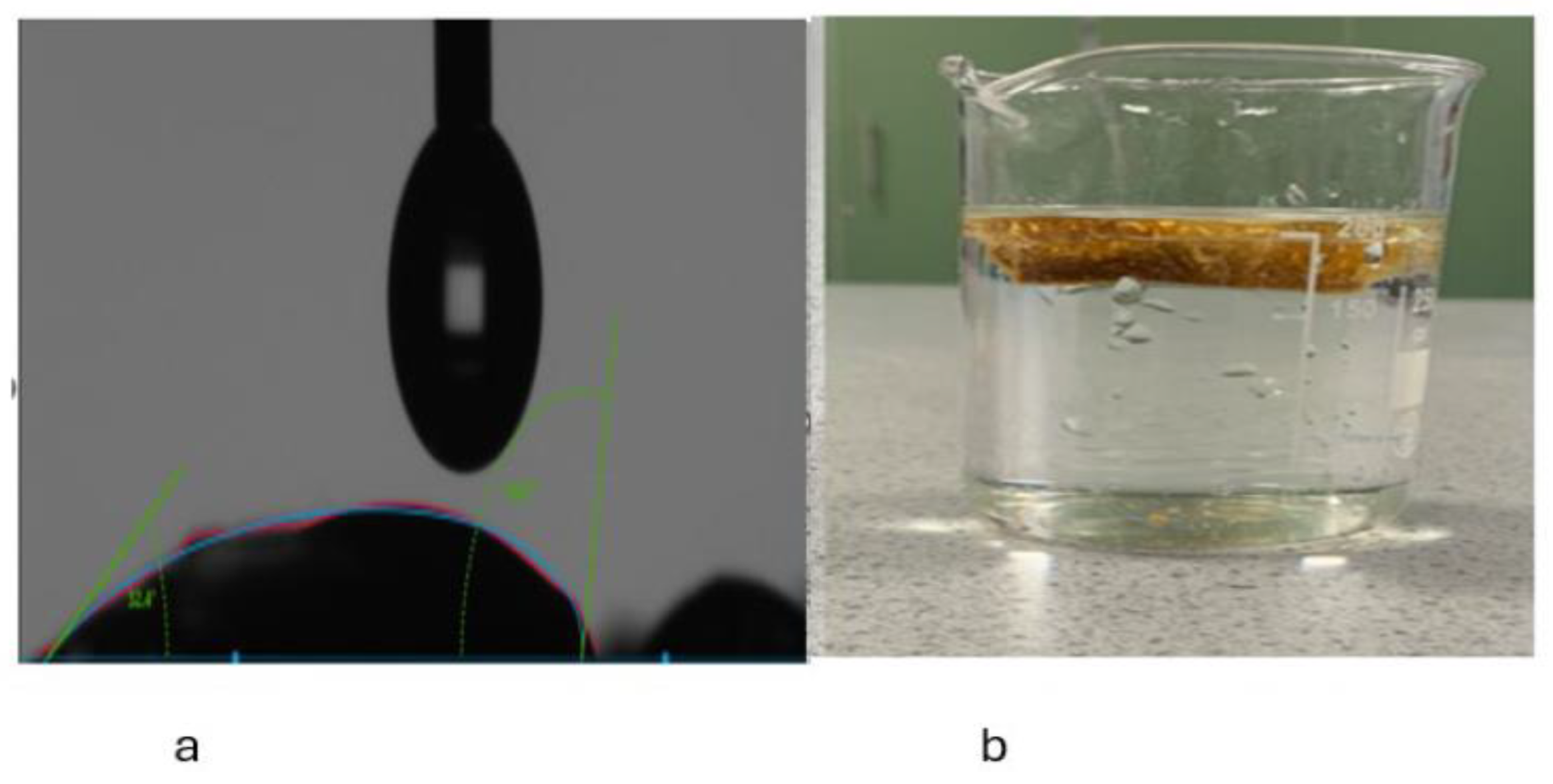

2.3. Hydrophobic Test

2.3.1. The Floating Test

Water Contact Angle Measurement

2.4. Adsorption Experiments

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Morphology and Structure of the Aerogel

3.1.1. Densities and Porosities

3.1.2. SEM Image of Prepared Orange Peel Aerogel

3.1.3. FT-IR of Prepared Orange Peel Aerogel

3.1.4. Hydrophobic Tests of the Aerogel

3.2. Oil Adsorption of Prepared Aerogels

4. Implications of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Anovitz, L.M.; Cole, D.R. Characterization and Analysis of Porosity and Pore Structures. Reviews in Mineralogy and Geochemistry [online]. 2015, 80, pp. 61–164. (accessed on 2 July 2020).

- Atai, E.; Jumbo, R. B.; Andrews, R.; Cowley, T.; Azuazu, I.; Coulon, F.; Pawlett, M. Bioengineering remediation of former industrial sites contaminated with chemical mixtures. Journal of Hazardous Materials Advances 2023, 10, 100319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuazu, I.N.; Sam, K.; Campo, P.; Coulon, F. Challenges and opportunities for low-carbon remediation in the Niger Delta: towards sustainable environmental management. Science of the Total Environment 2023, 900, 165739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barus, D.A.; Humaidi, S.; Ginting, R.T.; Sitepu, J. Enhanced adsorption performance of chitosan/cellulose nanofiber isolated from durian peel waste/graphene oxide nanocomposite hydrogels. Environmental Nanotechnology, Monitoring & Management [online]. 2022, 17, p. 100650. (accessed on 9 March 2022).

- Boulkhessaim, S.; Gacem, A.; Khan, S.H.; Amari, A.; Yadav, V.K.; Harharah, H.N.; Elkhaleefa, A.M.; Yadav, K.K.; Rather, S.U.; Ahn, H.J.; Jeon, B.H. Emerging trends in the remediation of persistent organic pollutants using nanomaterials and related processes: A review. Nanomaterials 2022, 12(13), 2148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, T.; Wang, H.; Jin, C.; Sun, Q.; Nie, Y. Fabrication of nitrogen-doped porous electrically conductive carbon aerogel from waste cabbage for supercapacitors and oil/water separation. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics [online] 2017, 29(5), 4334–4344. (accessed on 8 December 2021). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, S.; Dora, D.T.K.; Porwal, S.K. Silicon-free PSMA-modified aerogel derived from waste fruit peels for efficient oil recovery. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery [online]. 2023. (accessed on 13 September 2023).

- Chergui, S.; Yeddou, A.R.; Chergui, A.; Halet, F.; Nadjemi, B.; Ould-Dris, A. Removal of Cyanide from Aqueous Solutions by Biosorption onto Sorghum Stems: Kinetic, Equilibrium, and Thermodynamic Studies. Journal of Hazardous, Toxic, and Radioactive Waste [online] 2021, 26(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhajed, M.; Verma, C.; Sathawane, M.; Singh, S.; Maji, P.K. Mechanically durable green aerogel composite based on agricultural lignocellulosic residue for organic liquids/oil sorption. Marine Pollution Bulletin [online]. 2022, 180, p. 113790. (accessed on 15 November 2022).

- Cuong, T.V.; Quoc, P.N.; Kien, L.A.; Khoi, T.A.; Minh, P.C. Carbon Aerogel from Jackfruit Waste as New Material for Electrodes Capacitive Deionization. Chemical Engineering Transaction [online] 2022, 97, 2283–9216. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Q.; Li, D.; Sun, Y.; Wang, H.; Lu, Y.; Yang, D. Low temperature-resistant superhydrophobic and elastic cellulose aerogels derived from seaweed solid waste as efficient oil traps for oil/water separation. Chemosphere [online] 2023, 336, 139179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, Y.; Jing, Z.; Qiu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Qiu, F.; Pan, J.; Zhang, T.; Li, C. Multifunctional biomass carbon fiber aerogel based on resource utilization of agricultural waste-peanut shells for fast and efficient oil–water/emulsion separation. In Materials Science and Engineering; B [online], 2022; Volume 283, p. 115819. [Google Scholar]

- Deschamps, G.; Caruel, H.; Borredon, M.-E.; Albasi, C.; Riba, J.-P.; Bonnin, C.; Vignoles, C. Oil Removal from Water by Sorption on Hydrophobic Cotton Fibers. 2. Study of Sorption Properties in Dynamic Mode. Environmental Science & Technology [online] 2003, 37(21), 5034–5039. [Google Scholar]

- Dilamian, M.; Noroozi, B. Rice straw agri-waste for water pollutant adsorption: Relevant mesoporous super hydrophobic cellulose aerogel. Carbohydrate Polymers [online]. 2021, 251, p. 117016. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0144861720311899 (accessed on 30 October 2021).

- Do, N.; Truong, B.; Nguyen, P.; Le, K.; Duong, H.; Le, P. Composite aerogels of TEMPO-oxidized pineapple leaf pulp and chitosan for dyes removal. Separation and Purification Technology [online] 2022, 283, 120200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, N.H.N.; Tran, V.T.; Tran, Q.B.M.; Le, K.A.; Thai, Q.B.; Nguyen, P.T.T.; Duong, H.M.; Le, P.K. Recycling of Pineapple Leaf and Cotton Waste Fibers into Heat-insulating and Flexible Cellulose Aerogel Composites. Journal of Polymers and the Environment [online] 2020, 29(4), 1112–1121. (accessed on 14 February 2023). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Septiani, Eka Lutfi; Prastuti, Okky Putri; Kurniati, Yuni; Fauziyah, Mar’atul; Widiyastuti, W.; Setyawan, Heru; Wahyudiono; Kanda, H.; Goto, M. Sorption Efficiency in Dye Removal and Thermal Stability of Sorghum Stem Aerogel. Materials Science Forum [online]. 2019, 966, pp. 175–180. (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- Fadeeva, E.; Schlie-Wolter, S.; Chichkov, B.N.; Paasche, G.; Lenarz, T. Structuring of biomaterial surfaces with ultrashort pulsed laser radiation Author links open overlay panel E. Fadeeva 1, S. Schlie-Wolter 1, B.N. Chichkov 1, G. Paasche 2, T. Lenarz 2; 2016; pp. 145–172. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, N.; Guo, X.; Liang, S. Adsorption study of copper (II) by chemically modified orange peel. Journal of Hazardous Materials [online] 2009, 164(2–3), 1286–1292. (accessed on 28 September 2020). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, P.; Cardea, S.; Tabernero, A.; De Marco, I. Porous Aerogels and Adsorption of Pollutants from Water and Air: A Review. Molecules [online]. 2021, 26, p. 4440. (accessed on 14 November 2021).

- Huang, J.; Li, D.; Huang, L.; Tan, S.; Liu, T. Bio-Based Aerogel Based on Bamboo, Wastepaper, and Reduced Graphene Oxide for Oil/Water Separation. Langmuir [online]. 2022, 38, pp. 3064–3075. (accessed on 17 May 2022).

- Imran, M.; Islam, A.; Farooq, M.U.; Ye, J.; Zhang, P. Characterization and adsorption capacity of modified 3D porous aerogel from grapefruit peels for removal of oils and organic solvents. Environmental Science and Pollution Research [online] 2020, 27(35), 43493–43504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jumbo, R. B.; Coulon, F.; Cowley, T.; Azuazu, I.; Atai, E.; Bortone, I.; Jiang, Y. Evaluating different soil amendments as bioremediation strategy for wetland soil contaminated by crude oil. Sustainability 2022, 14(24), 16568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kästner, M.; Miltner, A. Application of compost for effective bioremediation of organic contaminants and pollutants in soil. Applied microbiology and biotechnology 2016, 100(8), 3433–3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly, J. M.; Doherty, R. M.; O’Connor, F. M.; Mann, G. W. The impact of biogenic, anthropogenic, and biomass burning volatile organic compound emissions on regional and seasonal variations in secondary organic aerosol. Atmos. Chem. Phys. 2018, 18, 7393–7422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz, L.; Ghaani, M.R.; MacElroy, J.M.D.; English, N.J. A comprehensive review on the application of aerogels in CO2-adsorption: Materials and characterisation. Chemical Engineering Journal [online] 2021, 412(Volume 412 128604), 128604. (accessed on 16 March 2021). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, G.; Dora, D.T.K.; Jadav, D.; Naudiyal, A.; Singh, A.; Roy, T. Utilization and regeneration of waste sugarcane bagasse as a novel robust aerogel as an effective thermal, acoustic insulator, and oil adsorbent. Journal of Cleaner Production [online] 2021, 298(126744), 126744. (accessed on 12 October 2022). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Sam, K.; Coulon, F.; De Gisi, S.; Notarnicola, M.; Labianca, C. Recent developments and prospects of sustainable remediation treatments for major contaminants in soil: A review. Science of the Total Environment 2024, 912, 168769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Li, J.; Wang, G.; Zhang, T.; Dai, W.; Ho, K. F.; Wang, Q.; Shao, Y.; Wu, C.; Li, L. Molecular characteristics of organic compositions in fresh and aged biomass burning aerosols. Science of The Total Environment 2020, 741, 140247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, L.; Lei, S.; Xi, J.; Ye, D.; Hu, W.; Song, L.; Hu, Y.; Cai, W.; Gui, Z. Bio-based multifunctional carbon aerogels from sugarcane residue for organic solvents adsorption and solar-thermal-driven oil removal. Chemical Engineering Journal [online] 2021, 426(129580), 129580–129580. (accessed on 12 September 2023). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, S.; Guo, X.; Feng, N.; Tian, Q. Application of orange peel xanthate for the adsorption of Pb2+ from aqueous solutions. Journal of Hazardous Materials [online] 2009, 170(1), 425–429. (accessed on 18 May 2022). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luu, T.P.; Do, N.H.N.; Chau, N.D.Q.; Lai, D.Q.; Nguyen, S.T.; Le, D.; Thai, Q.B.; Le, P.K.; Duong, H.M. Morphology control and advanced properties of bio-aerogels from pineapple leaf waste. Chemical Engineering 2020, 78, 433–438. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Y.; Bao, J.; Dang, Y.; Liu, D.; Li, T.; Li, S.; Yu, Y.; Zhu, L. Biochar aerogel enhanced remediation performances for heavy oil-contaminated soil through biostimulation strategy. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2023, 443, 130209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michael-Igolima, U.; Abbey, S.J.; Ifelebuegu, A.O.; Eyo, E.U. Modified Orange Peel Waste as a Sustainable Material for Adsorption of Contaminants. Materials;Materials [online] 2023, 16(3), 1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michaux, S.P. The mining of minerals and the limits to growth; Geological Survey of Finland: Espoo, Finland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad, S.; Albadn, Y. M.; Yahya, E. B.; Nasr, S.; Khalil, H. A.; Ahmad, M. I.; Kamaruddin, M. A. Trends in enhancing the efficiency of biomass-based aerogels for oil spill clean-up. Giant 2024, 100249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.D.; Vu, C.M.; Vu, H.T.; Choi, H.J. Micron-Size White Bamboo Fibril-Based Silane Cellulose Aerogel: Fabrication and Oil Absorbent Characteristics. Materials [online]. 2019, 12, p. 1407. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1944/12/9/1407/htm (accessed on 17 March 2021).

- Nguyen, H.; Tran, K.A.; Tram, H.N.N.; Le, Kien Anh; Le, P.K. Fabrication of Carbon Aerogels from Coir for Oil Adsorption. IOP conference series [online], 2022; 964, pp. 012033–012033. (accessed on 13 September 2023). [Google Scholar]

- Nita, L.E.; Ghilan, A.; Rusu, A.G.; Neamtu, L.; Chiriac, A.P. New Trends in Bio-Based Aerogels. Pharmaceutics [online] 2020, 12(5). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ouyang, D.; Lei, X.; Zheng, H. Recent advances in biomass-based materials for oil spill cleanup. Nanomaterials 2023, 13(3), 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Han, G.; Mao, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Duan, H.; Huang, J.; Qu, L. Structural characteristics and physical properties of lotus fibres obtained from Nelumbo nucifera petioles. Carbohydrate Polymers [online]. 2011, 85, pp. 188–195. (accessed on 23 May 2021).

- Tu, Phan Minh; Chau, N.; Ngan, Le Thanh; Lam, Cao Vu; Thang, Tran Quoc; Duyen, K.; Toan, Huynh Phuoc; Son, Nguyen Truong; Hieu, Nguyen Huu. Superhydrophobic banana stem–derived carbon aerogel for oil and organic adsorptions and energy storage. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery [online]. 2023. (accessed on 11 September 2023).

- Phat, L.N.; Nguyen, H.C.; Khoa, B.D.D.; Khang, P.T.; Tien, D.X.; Thang, T.Q.; Trung, N.K.; Nam, H.M.; Phong, M.T.; Hieu, N.H. Synthesis and surface modification of cellulose cryogels from coconut peat for oil adsorption. 2022, pp. 2435–2447. (accessed on 18 May 2022).

- Pung, T.; Ponglong, N.; Panich-pat, T. Fabrication of Pomelo-Peel Sponge Aerogel Modified with Hexadecyltrimethoxysilane for the Removal of Oils/Organic Solvents. Water, Air, & Soil Pollution [online]. 2022, 233. (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- Sam, K.; Onyena, A.P.; Zabbey, N.; Odoh, C.K.; Nwipie, G.N.; Nkeeh, D.K.; Osuji, L.C.; Little, D.I. Prospects of emerging PAH sources and remediation technologies: insights from Africa. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2023, 30(14), 39451–39473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, S.; Tiwari, S.; Hasan, A.; Saxena, V.; Pandey, L.M. Recent advances in conventional and contemporary methods for remediation of heavy metal-contaminated soils. 3 Biotech 2018, 8(4), 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheesley, R. J.; Schauer, J. J.; Chowdhury, Z.; Cass, G. R.; Simoneit, B. R. Characterization of organic aerosols emitted from the combustion of biomass indigenous to South Asia. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres 2003, 108(D9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, G.; Qian, Y.; Tan, F.; Cai, W.; Li, Y.; Cao, Y. Controllable synthesis of pomelo peel-based aerogel and its application in adsorption of oil/organic pollutants. In Royal Society Open Science [online]; 2019; 6, 2. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6408386/ (accessed on 20 October 2020).

- Singh, A.K.; Ketan, K.; Singh, J.K. Simple and green fabrication of recyclable magnetic highly hydrophobic sorbents derived from waste orange peels for removal of oil and organic solvents from water surface. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering [online] 2017, 5(5), 5250–5259. (accessed on 9 August 2022). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, P.; Adams, J.; Beerling, D.J.; Beringer, T.; Calvin, K.V.; Fuss, S.; Griscom, B.; Hagemann, N.; Kammann, C.; Kraxner, F.; Minx, J.C. Land-management options for greenhouse gas removal and their impacts on ecosystem services and the sustainable development goals. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 2019, 44(1), 255–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.T.; Nguyen, S.T.; Do, N.D.; Thai, N.N.T.; Thai, Q.B.; Huynh, H.K.P.; Phan, A.N. Green aerogels from rice straw for thermal, acoustic insulation and oil spill cleaning applications. Materials Chemistry and Physics [online] 2020, 253, 123363. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, A.; Thakur, S.; Goel, G.; Raj, J.; Gupta, V.K.; Roberts, D.; Thakur, V.K. Bio-based sustainable aerogels: New sensation in CO2 capture Current Research in Green and Sustainable Chemistry 2020. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Dong, Yong Ping; Xu, M.; Xia, J.; Liu, Z.; Cao, Y. Aerogels made from soybean stalk with various lignocellulose aggregating states for oil spill clean-up. Cellulose [online]. 2021, 28, pp. 9873–9891. (accessed on 12 September 2023).

- Xing, H.; Fei, Y.; Cheng, J.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J.; Niu, C.; Fu, Q.; Cheng, J.; Lu, L. Green Preparation of Durian Rind-Based Cellulose Nanofiber and Its Application in Aerogel. Molecules [online]. 2022, 27, p. 6507. (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Yue, X.; Zhang, T.; Yang, D.; Qiu, F.; Li, Z. Hybrid aerogels derived from banana peel and wastepaper for efficient oil absorption and emulsion separation. Journal of Cleaner Production [online] 2018, 199, 411–419. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0959652618321711 (accessed on 17 September 2020). [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; You, L.; Shen, X.; Li, S. An environmentally friendly carbon aerogels derived from waste pomelo peels for the removal of organic pollutants/oils. Microporous and Mesoporous Materials [online]. 241. 2017, 241, pp. 285–292. (accessed on 15 April 2023).

| Waste material | Preparation process | Density g/cm3 |

Porosity % |

Contact angle | Sorption capacities g/g | Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banana leaf | Freeze drying | 0.14-0.28 | - | - | - | Thermal insulation | Raji et al., 2023 |

| Banana leaf | Freeze drying | 0.015 | - | 149o | 35 - 115 | Adsorption of oil/organic solvents |

Yue et al., 2018 |

| Banana stem | Freeze drying + Pyrolysis | - | - | 135o | 35 | Thermal insulation | Tu et al., 2023 |

| Pineapple leaf | Freeze drying | 0.127 – 0.326 | 97 – 99 | - | - | Thermal insulation | Luu et al., 2020 |

| Pineapple leaf | Freeze drying | 0.063 – 0.093 | 92 – 94 | - | - | Thermal insulation | Do et al., 2020 |

| Pineapple leaf | Freeze drying | 0.013 – 0.033 | 96 – 99 | 140o | 38 | Adsorption of oil |

Do et al., 2020 |

| Pineapple leaf + Cotton waste | Freeze drying | 0.019 – 0.046 | 96 | - | - | Thermal insulation | Do et al., 2022 |

| Peanut shell | Freeze drying + Carbonization | - | 98 | 141o | 27-50 | Adsorption of oil/organic solvents | Dai et al., 2022 |

| Seaweed solid waste | Freeze drying + Carbonization | - | - | 153o | 11-30 | Adsorption of oil |

Dai et al., 2023 |

| Rice straw | Freeze drying | 0.012 | 99.5 | 120o | 28 - 70 | Adsorption of oil/organic solvents | Chhajed et al., 2022 |

| Rice straw | Freeze drying | 0.002 – 0.024 | 98.4 – 99.8 | 151o | 98 - 170 | Adsorption of oil/organic solvents. | Dilamian et al., 2021 |

| Rice straw | Freeze drying | 0.05 – 0.06 | 97 | 150o | 13 | Thermal insulator | Tran et al., 2020 |

| Bamboo powder + Wastepaper | Freeze drying | 0.011 | - | 118o – 142o | 67 – 121 | Adsorption of oil | Huang et al., 2022 |

| Soybean stalk | Freeze drying | - | 95 – 97 | - | 16 – 31 | Adsorption of oil | Wu et al., 2021 |

| Sugarcane bagasse | Freeze drying | 0.016 – 0.122 | 91.9 – 98.9 | - | Adsorption of oil/organic solvent | Li et al., 2020 | |

| Sugarcane bagasse | Freeze drying | 0.016 – 0.112 | 92 - 99 | - | 25 | Adsorption of oil/organic solvent | Thai et al., 2020 |

| Sugarcane bagasse | Freeze drying | 0.012 – 0.108 | 92.9 – 99.2 | 140o | 23 | Thermal insulation/oil adsorption | Kumar et al., 2021 |

| Sorghum stem | Freeze drying | 0.146 – 0.167 | 90 | - | - | Adsorption of dyes | Septiani et al., 2019 |

| Sorghum stem | Freeze drying | - | - | - | 0.076 | Adsorption of organic and inorganic solvents | Chergui et al., 2021 |

| Lupin hull | Freeze drying | 0.030 | 98.1 | - | - | Food packaging | Ciftci et al., 2017 |

| Lupin hull | SCCO2 Freeze drying |

0.009 0.05 |

99.4 96.6 |

- | - | Food packaging | Deniz Ciftci, 2017 |

| White bamboo | Freeze drying | 0.085 – 0.144 | 90 – 95 | 114o – 132o | - | Adsorption of oil | Nguyen et al., 2019 |

| Durian | Ultrasonic | 0.003 – 0.012 | 99 | - | Xing et al., 2022 | ||

| Durian | Freeze drying | 0.5 | - | - | - | Supercapacitor | Wang et al., 2020 |

| Jackfruit | Freeze drying | 0.275 | - | - | - | Supercapacitor | Lee et al., 2020 |

| Watermelon rind | Freeze drying + Pyrolysis | - | 91 – 94 | 127o | 53.51 – 70.52 | Adsorption/energy storage | Tu et al., 2022 |

| Pomelo | Freeze drying | - | - | 128o – 135o | 5 - 36 | Adsorption of organic pollutants and oil | Zhu et al., 2017 |

| Pomelo | Freeze drying + Carbonization | 0.020 | 98 | 132o | 49.2 – 71.3 | Adsorption of organic pollutants and oil | Shi et al., 2019 |

| Pomelo | Freeze drying | 0.18 – 0.23 | 80 – 87 | - | 1.7 – 3.9 | Adsorption of organic pollutants and oil | Pung et al., 2022 |

| Pomelo fruit peels + wastepaper | Freeze drying | 0.611 | 99 | 139o | Adsorption of oil | Chaudhary et al., 2023 | |

| Coconut peat | Freeze drying | 28.21 | 98 | - | 2.1 – 2.5 | Adsorption of oil | La et al., 2021 |

| Coconut peat | Freeze drying | 98 | 24.52 | Adsorption of oil | Phat et al., 2022 | ||

| Coconut fibre | Freeze drying + Carbonization | 0.034 – 0.063 | 96 - 98 | - | 0.63 – 0.65 | Adsorption of dye | Nguyen et al., 2022 |

| Cabbage | Freeze drying | - | - | - | - | Adsorption of oil and organic solvent/ supercapacitor | Cai et al., 2017 |

| Grapefruit peels | Freeze drying | 0.051 | - | 141o | - | Adsorption of oil and organic solvent. | Imran et al., 2020 |

| Chemical composition | Mass% (Zapata et al., 2009) |

Mass% (Santos et al., 2015) |

Mass% This study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon | 49.59 | 44.5 | 48.67 |

| Hydrogen | 6.95 | 6.1 | - |

| Oxygen | 39.7 | 47.3 | 36.46 |

| Na | - | - | 4.44 |

| Nitrogen | 0.66 | 1.5 | - |

| K | - | - | 0.95 |

| Ca | - | - | 1.08 |

| Sulphur | 0.06 | 0.4 | - |

| Chloride | 0.001 | - | 8.39 |

| Ash | 3.05 | 4.0 | - |

| Water | 2.73 | - | - |

| Oil type | Density (g/cm) | Viscosity (pas) |

|---|---|---|

| Vegetable oil | 0.910 | 0.061 |

| Type of aerogel | Average pore size (nm) | Pore diameter (nm) | Bulk density g/cm3 | Porosity % |

Water contact angle | Adsorption capacity (g/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| orange | 58 | 51 | 0.010417 | 99 | 102.7 | 5.3 - 8.0 |

| Waste material | Preparation process | Density g/cm3 |

Porosity % |

Contact angle | Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pineapple leaf | Freeze drying | 0.013 – 0.033 | 96 | 140o | Adsorption of oil |

Do et al. 2020 |

| Peanut shell | Freeze drying + Carbonization | - | 98 | 141o | Adsorption of oil/organic solvents | Dai et al. 2022 |

| Seaweed solid waste | Freeze drying + Carbonization | - | - | 153o | Adsorption of oil |

Dai et al. 2023 |

| Bamboo powder + Wastepaper | Freeze drying | 0.011 | - | 118o – 142o | Adsorption of oil | Huang et al. 2022 |

| Sugarcane bagasse | Freeze drying | 0.016 – 0.122 | 91.9 | - | Adsorption of oil/organic solvent | Li et al. 2021 |

| Sugarcane bagasse | Freeze drying | 0.016 – 0.112 | 92 | - | Adsorption of oil/organic solvent | Thai et al. 2020 |

| White bamboo | Freeze drying | 0.085 – 0.144 | 90 – 95 | 114o – 132o | Adsorption of oil | Nguyen et al. 2019 |

| Pomelo | Freeze drying | - | - | 128o – 135o | Adsorption of organic pollutants and oil | Zhu et al. 2017 |

| Pomelo | Freeze drying + Carbonization | 0.020 | 98 | 132o | Adsorption of organic pollutants and oil | Shi et al. 2019 |

| Pomelo | Freeze drying | 0.18 – 0.23 | 80 – 87 | - | Adsorption of organic pollutants and oil | Pung et al. 2022 |

| Pomelo fruit peels + wastepaper | Freeze drying | 0.611 | 99 | 139o | Adsorption of oil | Chaudhary et al. 2023 |

| Coconut peat | Freeze drying | 28.21 | 98 | - | Adsorption of oil | La et al. 2021 |

| Coconut peat | Freeze drying | 98 | Adsorption of oil | Phat et al. 2022 | ||

| Grapefruit peels | Freeze drying | 0.051 | - | 141o | Adsorption of oil and organic solvent. | Imran et al. 2020 |

| Orange peels adsorbents | Oil adsorption capacities (mg/g) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OPA | 1st test | 2nd test | 3rd test | Average |

| Dry weight | 6.5 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 6.5 |

| Final weight | 74 | 74 | 73.5 | 73.83333 |

| Adsorption capacities | 10.38 | 10.38 | 10.35 | 10.37 |

| CMOP | 1st test | 2nd test | 3rd test | Average |

| Dry weight | 6.5 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 6.5 |

| Final weight | 52 | 52 | 51 | 51.66667 |

| Adsorption capacities | 7 | 7 | 6.8 | 6.933333 |

| Pristine | 1st test | 2nd test | 3rd test | Average |

| Dry weight | 6.5 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 6.5 |

| Final weight | 6.7 | 7 | 6.8 | 6.833333 |

| Adsorption capacities | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.05 | 0.053333 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).