1. Introduction

The transformation of urban environments into smart cities represents one of the most significant technological paradigms of the 21st century, fundamentally reshaping how transportation systems operate and interact with urban infrastructure. At the heart of this transformation lies the evolution of Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITS), which leverage advanced communication technologies to enhance traffic management, improve road safety, and optimize energy consumption across vehicular networks. The integration of Vehicle Ad-Hoc Networks (VANETs) within smart city ecosystems has emerged as a critical enabler for realizing the vision of autonomous and cooperative transportation systems.

Traditional VANET deployments, however, face substantial challenges that limit their effectiveness in dense urban environments. Energy consumption remains a persistent concern, particularly as vehicular nodes rely on battery-powered systems for communication and computation tasks. The frequent exchange of beacon messages, continuous route maintenance, and cryptographic operations contribute to rapid energy depletion, potentially compromising network connectivity and reducing the operational lifetime of vehicular systems. Furthermore, the dynamic nature of vehicular mobility patterns, characterized by high-speed movement, frequent topology changes, and variable node density, creates additional complexity for energy-efficient communication protocols.

Security vulnerabilities present another critical dimension of the VANET deployment challenge. The open wireless medium, combined with the critical nature of vehicular communications, makes these networks attractive targets for various malicious activities. Identity spoofing attacks can compromise the authenticity of traffic information, while Sybil attacks can manipulate consensus-based routing decisions. False message injection poses direct threats to road safety by disseminating incorrect traffic conditions or emergency alerts. The consequences of successful attacks extend beyond network performance degradation to potentially life-threatening scenarios involving collision avoidance systems and emergency response coordination.

Privacy preservation adds another layer of complexity to vehicular network design. Location privacy remains particularly sensitive, as continuous tracking of vehicle movements can reveal detailed information about user behavior, destinations, and travel patterns. Traditional approaches to privacy protection often introduce computational overhead that conflicts with energy efficiency objectives, creating a fundamental trade-off between security and sustainability in VANET deployments.

The advent of 5G technology presents unprecedented opportunities to address these longstanding challenges through revolutionary improvements in communication capabilities, network architecture, and service delivery models. The 5G ecosystem introduces three fundamental service categories that align directly with smart city requirements: Ultra-Reliable Low-Latency Communication (URLLC) for safety-critical applications, enhanced Mobile Broadband (eMBB) for high-bandwidth services, and massive Machine Type Communication (mMTC) for large-scale sensor deployments. Network slicing technology enables the simultaneous support of these diverse service requirements within a unified infrastructure, providing quality of service guarantees tailored to specific application domains.

Mobile Edge Computing (MEC) represents another transformative aspect of 5G technology for vehicular networks. By deploying computational resources at the network edge, MEC enables local processing of routing decisions, traffic prediction, and security functions with significantly reduced latency compared to cloud-based approaches. This distributed intelligence model aligns perfectly with the real-time requirements of vehicular applications while providing opportunities for energy optimization through computational offloading.

Despite the promising potential of 5G technology for vehicular networks, existing research has not fully exploited the synergistic benefits of integrating VANET routing protocols with 5G network slicing, MEC capabilities, and comprehensive security frameworks. Most current approaches treat these technologies as independent components rather than designing holistic solutions that leverage their combined strengths. The lack of integrated architectures that simultaneously optimize energy consumption, security, and quality of service remains a significant gap in the current research landscape.

This paper addresses these challenges by introducing GreenFlow VANET, a comprehensive 5G-enabled secure and energy-efficient routing solution specifically designed for smart city deployments. Our approach represents a paradigm shift from traditional VANET architectures by fully integrating 5G network capabilities into the routing protocol design, leveraging MEC for distributed intelligence, and providing comprehensive security mechanisms that preserve privacy while maintaining energy efficiency.

The key contributions of this research are:

GreenFlow Three-Tier Architecture: A novel hierarchical architecture integrating vehicular nodes with 5G edge infrastructure and cloud services, enabling seamless coordination between local decision-making and global optimization while supporting diverse application requirements through network slicing.

5G-Aware Secure Routing Protocol (GF-5G-SRP): A comprehensive routing protocol that leverages 5G Quality of Service (QoS) metrics, MEC-assisted route discovery, and multi-criteria next-hop selection to optimize performance across URLLC, eMBB, and mMTC slices while maintaining energy efficiency and security.

Integrated Security and Privacy Framework: A multi-layered security approach combining ECC-256 cryptography, ChaCha20-Poly1305 encryption, distributed trust management, and 5G-native privacy preservation techniques (SUPI/SUCI) that provides comprehensive protection without compromising energy efficiency.

MEC-Assisted Energy Optimization: Advanced energy management techniques leveraging edge computing for route optimization, predictive caching, and adaptive transmission control that achieve significant energy savings while maintaining quality of service guarantees.

Comprehensive Performance Validation: Extensive simulation-based evaluation demonstrating 96.8% packet delivery ratio, 59% energy reduction, 81% network lifetime improvement, and 97.8% attack detection rates in realistic smart city scenarios with up to 1000 vehicles.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 provides comprehensive background on VANET fundamentals, 5G technology, and related work in energy-efficient and secure routing.

Section 3 formulates the research problem mathematically, including network models, energy equations, and optimization objectives.

Section 4 presents the detailed GreenFlow system architecture and routing protocol design.

Section 5 evaluates performance through extensive simulations, discusses key findings, and concludes with future research directions.

2. Background and Related Work

2.1. VANET Fundamentals

Vehicle Ad-Hoc Networks represent a specialized form of Mobile Ad-Hoc Networks (MANETs) designed to support communication between vehicles and between vehicles and roadside infrastructure. The foundational architecture of VANETs is defined by

IEEE 802.11p standards [

1] and WAVE (Wireless Access in Vehicular Environments) protocols [

2], which specify the physical and medium access control layers for dedicated short-range communications (DSRC). Traditional VANET architectures support three primary communication paradigms: Vehicle-to-Vehicle (V2V), Vehicle-to-Infrastructure (V2I), and Vehicle-to-Network (V2N) communications.

The unique characteristics of vehicular networks, including high mobility, dynamic topology, and predictable movement patterns, distinguish VANETs from conventional wireless networks [

3]. Vehicle mobility follows road constraints, creating semi-predictable communication patterns that can be leveraged for routing optimization. However, the high-speed movement of vehicles results in frequent link breaks and requires rapid route recalculation, presenting significant challenges for maintaining communication quality [

4].

Onboard Units (OBUs) serve as the primary communication devices in vehicles, equipped with GPS receivers, wireless transceivers, and computational capabilities for local processing. Road Side Units (RSUs) provide infrastructure support, extending communication coverage and serving as access points for internet connectivity [

5]. The integration of these components creates a hybrid network topology that combines ad-hoc characteristics with infrastructure support.

2.2. 5G Technology for Vehicular Networks

The fifth-generation wireless technology represents a fundamental transformation in mobile communications, specifically designed to support diverse application requirements through three main service categories. Ultra-Reliable Low-Latency Communication (URLLC) targets critical applications requiring latency below 1 millisecond and reliability exceeding 99.999% [

6]. Enhanced Mobile Broadband (eMBB) provides high-capacity services with peak data rates exceeding 10 Gbps [

7]. Massive Machine Type Communication (mMTC) supports large-scale deployments with up to one million devices per square kilometer [

8].

Network slicing technology enables the simultaneous provision of these diverse services within a unified 5G infrastructure [

9]. The 3GPP standards define network slicing architecture in TS 23.501 [

10], specifying how logical network instances can be created and managed to provide customized service guarantees. For vehicular applications, network slicing enables the differentiation of safety-critical communications from infotainment services, ensuring appropriate resource allocation and quality of service guarantees.

Mobile Edge Computing (MEC) represents another critical component of 5G architecture for vehicular networks [

11]. By deploying computational resources at base stations and access points, MEC enables ultra-low latency processing for time-sensitive applications. The European Telecommunications Standards Institute (ETSI) defines MEC architecture and service requirements in specifications that directly support vehicular use cases [

12]. MEC capabilities include local content caching, traffic optimization, and distributed intelligence for autonomous driving applications.

The 5G Core Network architecture, defined in 3GPP TS 23.502 [

13], introduces service-based architecture principles that support flexible service deployment and management. Key network functions including Access and Mobility Management Function (AMF), Session Management Function (SMF), and User Plane Function (UPF) provide the foundation for vehicular service delivery. The integration of 5G with vehicular networks enables new paradigms for cooperative driving, traffic management, and smart city services [

14].

2.3. Traditional VANET Routing Protocols

VANET routing protocols have evolved through multiple generations, each addressing specific challenges of vehicular communication. Ad-hoc On-Demand Distance Vector (AODV) protocol [

15] represents one of the earliest approaches, utilizing reactive route discovery through Route Request (RREQ) and Route Reply (RREP) messages. While AODV provides good performance in stable networks, its reactive nature introduces significant delays in highly dynamic vehicular environments.

Dynamic Source Routing (DSR) [

16] employs source routing principles where complete route information is carried in packet headers. This approach eliminates the need for routing tables at intermediate nodes but introduces packet overhead that becomes problematic in large-scale deployments. Geographic routing protocols address scalability concerns by leveraging location information for forwarding decisions.

Greedy Perimeter Stateless Routing (GPSR) [

17] represents a landmark geographic routing approach that forwards packets to neighbors closest to the destination. While GPSR reduces routing overhead compared to topology-based protocols, it suffers from local minima problems and does not account for link quality or node characteristics in forwarding decisions.

Geographic Source Routing (GSR) [

18] combines geographic routing with street-level topology awareness, improving performance in urban environments. However, GSR requires detailed map information and exhibits limited adaptation to dynamic traffic conditions. Anchor-based Street and Traffic Aware Routing (A-STAR) [

19] extends geographic routing with anchor point selection based on traffic patterns and road connectivity.

Position-based routing protocols have been extensively studied for vehicular networks [

20]. These approaches leverage GPS information to make forwarding decisions without maintaining routing tables. However, traditional position-based protocols do not consider factors such as energy consumption, security requirements, or quality of service constraints that are critical for smart city deployments.

2.4. Energy-Efficient Routing

Energy efficiency has emerged as a critical concern for vehicular networks, particularly as vehicles increasingly rely on battery-powered systems for communication and computation. Early research focused on power control mechanisms to reduce transmission energy consumption [

21]. Adaptive power control adjusts transmission power based on link quality and distance, reducing interference and energy consumption while maintaining connectivity.

Energy-Aware Secure AODV (ESAR) [

22] incorporates energy metrics into route selection decisions, favoring routes through nodes with higher residual energy levels. This approach extends network lifetime by distributing energy consumption across multiple nodes. However, ESAR does not address the specific challenges of 5G integration or provide comprehensive security mechanisms.

Sleep scheduling mechanisms represent another approach to energy optimization in vehicular networks [

23]. These protocols coordinate sleep and wake cycles among neighboring vehicles to reduce idle listening while maintaining network connectivity. Coordinated sleep scheduling requires careful synchronization to avoid disrupting time-sensitive communications.

Energy harvesting techniques have been explored for vehicular networks, leveraging solar panels, kinetic energy recovery, and other renewable sources [

24]. While energy harvesting can extend operational lifetime, the variability of energy availability requires adaptive protocols that can adjust performance based on energy conditions.

Recent research has investigated machine learning approaches for energy-efficient routing in vehicular networks [

25]. These approaches use historical data and predictive models to optimize routing decisions based on traffic patterns, energy consumption patterns, and network conditions. However, machine learning approaches often require significant computational resources that may conflict with energy efficiency objectives.

2.5. Secure VANET Routing

Security represents a paramount concern for vehicular networks due to the safety-critical nature of transportation applications. The open wireless medium and dynamic network topology create multiple attack vectors that threaten both network functionality and user safety. Cryptographic approaches form the foundation of secure vehicular communications, with Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) providing the basis for authentication and message integrity [

26].

Digital signature schemes, particularly those based on Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC), provide efficient authentication for vehicular messages [

27]. ECC-256 offers comparable security to RSA-2048 with significantly reduced computational overhead, making it suitable for resource-constrained vehicular environments. However, the computational cost of signature verification can become prohibitive in dense traffic scenarios with high message rates.

Trust-based routing protocols address security concerns by incorporating reputation mechanisms into routing decisions [

28]. These approaches maintain trust scores for neighboring nodes based on observed behavior, including packet forwarding reliability, message authenticity, and cooperation in network protocols. Trust-based routing can effectively identify and isolate malicious nodes but requires careful design to prevent trust manipulation attacks.

Intrusion detection systems for vehicular networks employ various techniques to identify malicious behavior [

29]. Signature-based detection identifies known attack patterns, while anomaly-based detection flags unusual behavior that may indicate new attacks. Distributed intrusion detection leverages cooperation among multiple nodes to improve detection accuracy and reduce false positives.

Privacy preservation in vehicular networks focuses primarily on location privacy, as continuous tracking of vehicle movements can reveal sensitive information about user behavior [

30]. Pseudonym changing mechanisms provide anonymity by periodically updating vehicle identifiers, making it difficult to correlate messages from the same vehicle over time. However, pseudonym management requires careful coordination to maintain authentication capabilities while preserving privacy.

Blockchain technology has emerged as a promising approach for secure vehicular communications, providing distributed trust management and tamper-resistant data storage [

31]. Blockchain-based trust systems can maintain reputation scores for network participants without relying on centralized authorities. However, the computational and energy overhead of blockchain operations requires careful optimization for vehicular environments.

2.6. 5G-Enabled VANET Research

The integration of 5G technology with vehicular networks represents an active area of research that is rapidly evolving as 5G deployments become more widespread. Early research focused on understanding how 5G capabilities can enhance traditional VANET applications [

32]. Ultra-low latency communication enables new applications such as cooperative collision avoidance and real-time traffic optimization that were not feasible with previous generation wireless technologies.

Network slicing for vehicular applications has been investigated in several studies [

33], exploring how different service types can be supported simultaneously within 5G infrastructure. Safety-critical communications require URLLC slice guarantees, while infotainment services can utilize eMBB capabilities. However, most existing research treats network slicing as a separate layer rather than integrating slice-aware decision making into routing protocols.

MEC-enabled vehicular services represent another significant research direction [

34]. Edge computing capabilities enable local processing of computationally intensive tasks such as computer vision for autonomous driving, traffic pattern analysis, and security monitoring. MEC can significantly reduce latency compared to cloud-based processing while reducing backhaul bandwidth requirements.

5G-VANET integration challenges include mobility management, handover optimization, and quality of service provisioning [

35]. Vehicle mobility creates frequent handovers between base stations, requiring optimized procedures to maintain service continuity. The high speed of vehicles can result in rapid signal degradation, particularly for millimeter-wave 5G bands, necessitating adaptive protocols that can quickly adapt to changing conditions.

Security and privacy in 5G-VANET integration introduce new challenges and opportunities [

36]. 5G security architecture provides enhanced authentication mechanisms through 5G-AKA protocols and improved encryption through advanced ciphers. However, the increased complexity of 5G networks also creates new attack vectors that must be addressed in vehicular deployments.

Recent research has investigated the performance of existing VANET protocols in 5G environments [

37], finding that traditional protocols often fail to exploit the full capabilities of 5G technology. This gap motivates the development of native 5G routing protocols that are specifically designed to leverage network slicing, MEC capabilities, and enhanced security features.

Machine learning integration with 5G-VANET systems has shown promise for predictive route optimization, traffic pattern analysis, and adaptive security [

38]. However, the computational requirements of machine learning algorithms must be carefully balanced against energy efficiency constraints, particularly for battery-powered vehicular systems.

Despite significant research progress, several gaps remain in 5G-VANET integration. Most existing approaches focus on individual aspects such as routing, security, or energy efficiency without providing comprehensive solutions that address all requirements simultaneously. The need for holistic approaches that fully integrate 5G capabilities with vehicular network requirements motivates the development of new architectures and protocols such as the GreenFlow VANET system presented in this paper.

3. Problem Formulation

This section formalizes the challenges addressed by GreenFlow VANET through mathematical modeling of the network environment, optimization objectives, and constraint definitions. The problem formulation provides the theoretical foundation for the proposed solution architecture and routing protocol design.

3.1. Network Model

We model the GreenFlow VANET system as a time-varying graph G(t) = (V(t), E(t)), where V(t) represents the set of vehicular nodes at time t, and E(t) denotes the set of communication links. The network comprises three distinct node types: vehicular nodes (V_v), Road Side Units (V_r), and Mobile Edge Computing nodes (V_m), such that V(t)=Vv(t)∪Vr∪Vm.

Each vehicular node i ∈ Vv(t) is characterized by a tuple ((pi(t),vi(t),Ei(t),Ti(t),Si)), where p_i(t) represents the geographic position, Vi(t) denotes the velocity vector, Ei(t) indicates the residual energy level, Ti(t) represents the trust score, and S_i defines the security credentials. The dynamic nature of vehicular networks requires continuous updates of node attributes based on mobility patterns and network interactions.

Communication links e_ij ∈ E(t) exist between nodes i and j if the received signal strength indicator (RSSI) exceeds a minimum threshold and mutual authentication succeeds. Link quality is quantified through a composite metric Q_ij(t) that incorporates signal strength, link stability prediction, and historical reliability. The 5G network slicing architecture introduces slice-specific quality requirements that must be satisfied for successful link establishment.

The network slicing model defines four distinct slices: URLLC for safety-critical communications, eMBB-Traffic for traffic management, eMBB-Infotainment for entertainment services, and mMTC for sensor data collection. Each slice s ∈ {URLLC, eMBB-T, eMBB-I, mMTC} has specific quality of service requirements (λ_s, δ_s, ρ_s) representing maximum latency, minimum reliability, and required bandwidth respectively.

3.2. Multi-Objective Optimization Problem

The GreenFlow VANET routing problem is formulated as a multi-objective optimization problem that simultaneously minimizes energy consumption, maximizes network lifetime, ensures security requirements, and maintains quality of service guarantees across multiple network slices. The optimization problem can be expressed as:

Subject to:

where R represents a routing solution that defines paths for all communication flows in the network. The optimization problem seeks to identify Pareto-optimal solutions that balance competing objectives while satisfying slice-specific quality of service constraints and security requirements.

3.3. Energy Model

Energy consumption in GreenFlow VANET encompasses transmission, reception, processing, and idle listening components. The comprehensive energy model accounts for 5G-specific characteristics including beamforming, multiple-input multiple-output (MIMO) processing, and network slicing overhead.

Transmission energy for node i sending a packet of size L over distance d using transmission power

is modeled as:

where

represents circuit power consumption,

denotes transmission duration,

indicates power amplifier efficiency, and α represents path loss exponent (typically 2 for free space, 4 for multipath fading).

Reception energy includes radio frequency processing and baseband processing components:

where

represents receiver circuit power and

accounts for baseband signal processing energy.

Computational energy consumption includes cryptographic operations, routing calculations, and MEC offloading decisions:

where

represents cryptographic processing time,

denotes routing computation time, and

accounts for MEC communication overhead. The total energy consumption for node i during time interval Δt is:

where

represents energy consumed during idle states, including listening for incoming packets and maintaining synchronization with 5G infrastructure.

3.4. Security Requirements

The security requirements for GreenFlow VANET encompass six fundamental properties that must be maintained throughout network operation:

Authentication: All network participants must be authenticated using cryptographic credentials. Each message m must include a digital signature σ such that Verify(m, σ, PKi) = True, where PKi represents the public key of sender i.

Integrity: Message integrity must be preserved during transmission. Hash-based message authentication codes ensure that Hash(m||K_i) remains unchanged, where K_i represents a shared secret key.

Confidentiality: Sensitive information must be encrypted using approved cryptographic algorithms. Confidential data D must be encrypted as C = Encrypt(D, K) using Advanced Encryption Standard (AES) or ChaCha20 algorithms.

Non-repudiation: Senders cannot deny message transmission. Digital signatures provide non-repudiation through cryptographic proof of authorship that can be verified by third parties.

Availability: Network services must remain accessible despite attacks or failures. The system must maintain at least 95% service availability even under distributed denial of service attacks affecting up to 30% of network nodes.

Privacy: User location information must be protected through anonymization techniques. Location privacy is quantified using k-anonymity metrics where each location report cannot be distinguished from at least k-1 other vehicles in the same geographic area.

3.5. QoS Constraints for Network Slices

Each network slice has specific quality of service requirements that must be satisfied by the routing protocol:

Table 1.

Quality of Service (QoS) requirements.

Table 1.

Quality of Service (QoS) requirements.

| Network Slice |

Latency (max) |

Reliability (min) |

Bandwidth / Throughput |

Packet Loss / Jitter / Energy |

Additional QoS Metric |

| URLLC Slice |

λ_URLLC ≤ 1 ms |

δ_URLLC ≥ 99.999% |

– |

ε_URLLC ≤ 10⁻⁵, σ_URLLC ≤ 0.1 ms |

– |

| eMBB Traffic Slice |

λ_eMBB-T ≤ 10 ms |

δ_eMBB-T ≥ 99.8% |

ρ_eMBB-T ≥ 20 Mbps |

ε_eMBB-T ≤ 10⁻³ |

– |

| eMBB Infotainment Slice |

λ_eMBB-I ≤ 100 ms |

δ_eMBB-I ≥ 98.5% |

ρ_eMBB-I ≥ 50 Mbps |

– |

QoE_eMBB-I ≥ 4.0 / 5.0 |

| mMTC Slice |

λ_mMTC ≤ 500 ms |

δ_mMTC ≥ 97% |

– |

E_mMTC ≤ 1 μJ/bit |

ρ_mMTC ≥ 10⁶ devices/km² |

The table delineates Quality of Service (QoS) requirements for each network slice, establishing performance benchmarks that routing protocols must achieve. URLLC slices require ultra-low latency (≤1 ms) and exceptional reliability (≥99.999%) with stringent jitter and packet loss constraints, essential for safety-critical vehicular applications like collision avoidance and emergency braking. eMBB traffic slices emphasize high reliability (≥99.8%) and low latency (≤10 ms) with guaranteed bandwidth (≥20 Mbps) for real-time navigation and traffic updates. eMBB infotainment slices accommodate higher latency (≤100 ms) but demand greater bandwidth (≥50 Mbps) and superior Quality of Experience thresholds (≥4/5) for streaming and passenger connectivity. mMTC slices support massive-scale connectivity (≥10⁶ devices/km²) with relaxed latency requirements (≤500 ms), moderate reliability (≥97%), and energy-efficient operation (≤1 μJ/bit) for IoT sensors and environmental monitoring. This comprehensive framework enables systematic evaluation of slice-specific network performance and ensures GF-5G-SRP meets diverse application requirements across heterogeneous vehicular services. These constraints define the feasible solution space for the routing optimization problem and ensure that the GreenFlow VANET system can support diverse smart city applications with appropriate quality of service guarantees.

4. GreenFlow System Architecture and Routing Proto...

4.1. Three-Tier Architecture

The GreenFlow VANET system employs a hierarchical three-tier architecture that seamlessly integrates vehicular nodes with 5G edge infrastructure and cloud services. This architectural design enables scalable service delivery, distributed intelligence, and efficient resource utilization across diverse smart city applications.

As shown in

Figure 1, The

Vehicle Tier comprises diverse vehicle types equipped with Onboard Units (OBUs), 5G modems, and sensor arrays. Emergency vehicles receive priority access to URLLC slices for safety-critical communications. Autonomous vehicles leverage high-bandwidth eMBB connections for HD map updates and cooperative perception. Regular vehicles utilize basic safety applications with standard QoS requirements. Public transport vehicles optimize routes through real-time traffic information and passenger services.

The Edge/MEC Tier provides distributed intelligence through gNodeBs co-located with MEC servers. MEC Server 1 handles route optimization and traffic prediction with sub-10ms latency. MEC Server 2 provides security monitoring and context management for trust-based routing decisions. MEC Server 3 manages local caching and network slice orchestration. Road Side Units extend coverage and provide infrastructure-based services for intersection control, highway monitoring, and parking management.

The Cloud Tier hosts centralized services including the 5G Core Network, blockchain-based trust ledger, and Traffic Management Center. This tier provides global coordination, policy management, and analytics capabilities that complement edge-based intelligence with comprehensive smart city services.

Figure 2. shows the network slicing configuration enables simultaneous support of diverse service requirements through logical network instances. Each slice provides dedicated resources and service guarantees tailored to specific application domains. The URLLC slice ensures ultra-reliable communication for safety applications with stringent latency and reliability requirements. eMBB slices support high-bandwidth applications with differentiated QoS based on service priorities. The mMTC slice accommodates massive sensor deployments with energy-efficient communication protocols.

4.2. GF-5G-SRP Protocol Design

The GreenFlow 5G-Aware Secure Routing Protocol (GF-5G-SRP) represents a comprehensive routing solution that leverages 5G network capabilities, MEC assistance, and integrated security mechanisms. The protocol design follows six fundamental principles: slice awareness, energy efficiency, security integration, MEC utilization, trust-based decisions, and adaptive optimization. Protocol operation comprises five phases: initialization, route discovery, route selection, data forwarding, and maintenance. The initialization phase establishes 5G connectivity, authenticates with network slices, and synchronizes with local MEC servers. Route discovery leverages MEC assistance for optimal path computation based on real-time network conditions and slice requirements. The routing protocol maintains slice-specific routing tables that separate routing information for different service types. This separation enables independent optimization of routing decisions for safety, traffic, infotainment, and sensor communications while preventing interference between service types.

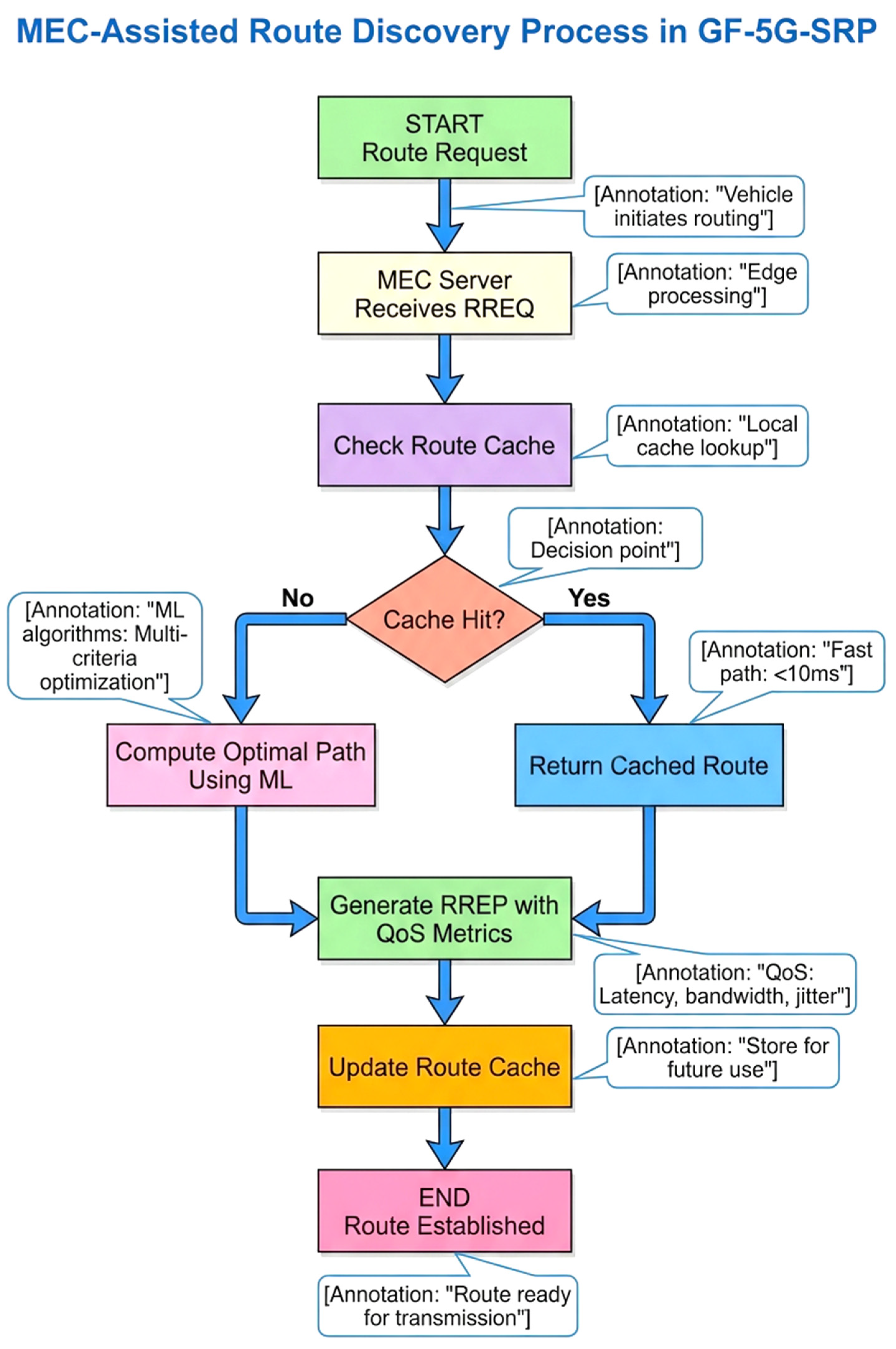

4.3. MEC-Assisted Route Discovery

The MEC-Assisted Route Discovery Process in GF-5G-SRP (Green Forwarding 5G Segment Routing Protocol) represents a sophisticated hybrid routing architecture that leverages edge computing intelligence to optimize path selection in vehicular networks. This flowchart illustrates how Multi-access Edge Computing (MEC) servers act as intelligent intermediaries between vehicles and cloud infrastructure, providing low-latency route computation while maintaining energy efficiency through strategic caching mechanisms.

The process begins when a vehicle initiates a Route Request (RREQ), which is intercepted by the nearest MEC server rather than being forwarded through the entire network. This edge-based approach fundamentally reduces latency by bringing computational resources closer to the data source. The MEC server immediately checks its Route Cache—a local repository of previously computed paths—representing the system’s first layer of optimization.

The Cache Hit decision point is critical, creating two distinct execution paths with dramatically different performance characteristics. When a valid cached route exists (cache hit), the system enters a fast path, returning the pre-computed route within milliseconds. This represents optimal performance, particularly crucial for time-sensitive vehicular applications like collision avoidance or emergency vehicle routing.

When cache misses occur, the system transitions to its intelligent computation phase, utilizing Machine Learning algorithms to calculate optimal paths. This computation considers multiple criteria simultaneously—including link quality (RSRP/RSRQ), residual energy levels, node trust scores, geographic progress toward destination, and real-time context awareness of traffic conditions. This multi-criteria approach distinguishes GF-5G-SRP from traditional routing protocols that typically optimize for single metrics like hop count or distance.

The Generate RREP with QoS Metrics step ensures that route replies include comprehensive quality-of-service information—latency guarantees, bandwidth availability, jitter characteristics, and reliability scores. This enables vehicles to make informed decisions about which network slice to utilize (URLLC for safety, eMBB for infotainment, or mMTC for sensor data).

The Update Route Cache mechanism completes the learning cycle, storing newly computed routes for future requests. This creates a self-improving system where frequently used routes become instantly available, while the ML models continuously refine their optimization strategies based on historical performance data and changing network conditions.

As shown in

Figure 3, MEC-assisted route discovery leverages edge computing capabilities to optimize routing decisions with reduced latency and improved accuracy. When a source node requires a route to a destination, it sends a Route Request (RREQ) message to the nearest MEC server. The MEC server first checks its local route cache for recently computed paths to the same destination.

If a cached route exists and remains valid based on freshness criteria, the MEC server immediately returns the cached path information. Otherwise, the MEC server computes optimal routes using machine learning models trained on historical traffic patterns, current network conditions, and slice-specific requirements.

The MEC-assisted approach reduces route discovery latency from hundreds of milliseconds in traditional protocols to less than 10 milliseconds. This improvement is crucial for meeting URLLC slice requirements and supporting real-time traffic management applications.

4.4. 5G-Aware Next-Hop Selection

As shown in Figure 3, the 5G-aware next-hop selection mechanism incorporates multiple criteria to optimize routing decisions for different network slices and application requirements. Link quality assessment utilizes 5G-specific metrics including Reference Signal Received Power (RSRP) and Reference Signal Received Quality (RSRQ) to evaluate channel conditions and predict link stability.

Figure 3.

Next-hop Selection flowchart.

Figure 3.

Next-hop Selection flowchart.

Energy scoring considers both residual energy levels and energy efficiency of potential next-hop neighbors. Nodes with higher remaining energy receive preference to extend network lifetime, while energy-efficient forwarding paths reduce overall consumption. Trust scores incorporate historical behavior observations and reputation-based assessments to identify reliable forwarding nodes.

Geographic progress measurement ensures packets advance toward their destinations while avoiding routing loops. Context awareness incorporates real-time traffic conditions, road infrastructure status, and predicted mobility patterns to optimize forwarding decisions for current network state.

The weight parameters are configured differently for each network slice to prioritize relevant criteria. URLLC slices emphasize link quality (w₁=0.35) and trust (w₃=0.30) to ensure reliable delivery. eMBB slices balance all criteria with moderate weights. mMTC slices prioritize energy efficiency (w₂=0.40) and context awareness (w₅=0.25) to extend battery lifetime for sensor networks.

4.5. Security Mechanisms

GreenFlow VANET integrates comprehensive security mechanisms throughout the routing protocol to protect against vehicular network threats while maintaining energy efficiency. The security framework employs Elliptic Curve Cryptography (ECC-256) for digital signatures, providing strong authentication with minimal computational overhead compared to traditional RSA approaches.

Message encryption utilizes ChaCha20-Poly1305, a modern authenticated encryption algorithm that provides confidentiality and integrity protection with superior performance on resource-constrained vehicular hardware. This cipher choice reduces encryption latency by approximately 40% compared to AES-GCM while maintaining equivalent security levels.

Trust management operates through a distributed blockchain-based ledger maintained at MEC servers. Each vehicle accumulates trust scores based on packet forwarding behavior, message validity, and cooperation in routing operations. Malicious nodes exhibiting packet dropping, message tampering, or identity spoofing rapidly lose trust scores and face isolation from routing paths. The blockchain provides immutable audit trails for trust score evolution, enabling forensic analysis and dispute resolution.

Privacy preservation leverages 5G Subscription Permanent Identifier (SUPI) and Subscription Concealed Identifier (SUCI) mechanisms to protect vehicle identity. Dynamic pseudonym management changes vehicle identifiers periodically while maintaining service continuity. Location privacy employs k-anonymity techniques ensuring that position information cannot be uniquely attributed to individual vehicles.

4.6. Energy Optimization Techniques

Energy optimization in GreenFlow VANET encompasses multiple complementary techniques operating across different protocol layers. Adaptive transmission power control adjusts radio power based on link quality requirements and neighbor proximity, reducing energy consumption during short-range communications while maintaining connectivity for distant nodes.

Sleep mode scheduling coordinates with 5G Discontinuous Reception (DRX) mechanisms to align vehicular node sleep cycles with network resource allocation. This coordination minimizes energy waste from unnecessary monitoring while ensuring responsiveness for URLLC slice communications. Cooperative caching at MEC servers reduces redundant transmissions by storing frequently requested content locally, decreasing both energy consumption and network congestion.

Beaconing optimization adapts message frequency based on mobility patterns and network density. High-speed vehicles in sparse environments reduce beacon rates, while dense urban scenarios maintain higher frequencies for accurate neighbor awareness. This adaptive approach achieves 30-40% reduction in signaling overhead compared to fixed-rate beaconing schemes.

5. Performance Evaluation, Discussion, and Conclus...

5.1. Simulation Setup

Performance evaluation of GreenFlow VANET employs Network Simulator 3 (NS-3) version 3.36 with the 5G-LENA module for accurate 5G NR simulation. The SUMO (Simulation of Urban Mobility) traffic simulator generates realistic vehicular mobility patterns for a 4km × 4km urban grid representing a dense smart city environment.The simulation topology includes 6 gNodeBs operating at 3.5 GHz (Sub-6 GHz) with coverage radius of 500 meters, complemented by 2 mmWave gNodeBs at 28 GHz providing high-bandwidth hotspots. Three MEC servers co-located with gNodeBs provide edge computing services with 2ms processing latency. Vehicle density varies from 100 to 1000 vehicles across different scenarios, with speeds ranging from 30 to 80 km/h representing urban traffic conditions.Communication parameters include 20 MHz channel bandwidth for Sub-6 GHz bands and 100 MHz for mmWave. Transmission power is 23 dBm for vehicles and 43 dBm for gNodeBs. The simulation duration is 600 seconds with 30-second warmup period. Traffic patterns include periodic safety messages (10 Hz), event-driven alert messages, and variable-rate traffic management updates.

5.2. Performance Metrics

The overall comparison is shown in

Table 2. Evaluation focuses on seven key performance metrics: Packet Delivery Ratio (PDR) measures the percentage of successfully delivered packets. End-to-end delay quantifies latency from source to destination including queuing, transmission, and propagation delays. Routing overhead assesses control message burden relative to data traffic. Energy consumption per packet evaluates the average energy expenditure for successful message delivery. Network lifetime defines the duration until the first node energy depletion. Throughput measures aggregate data delivery rate across all flows. Security detection rate quantifies the percentage of correctly identified malicious activities.

5.3. Results and Analysis

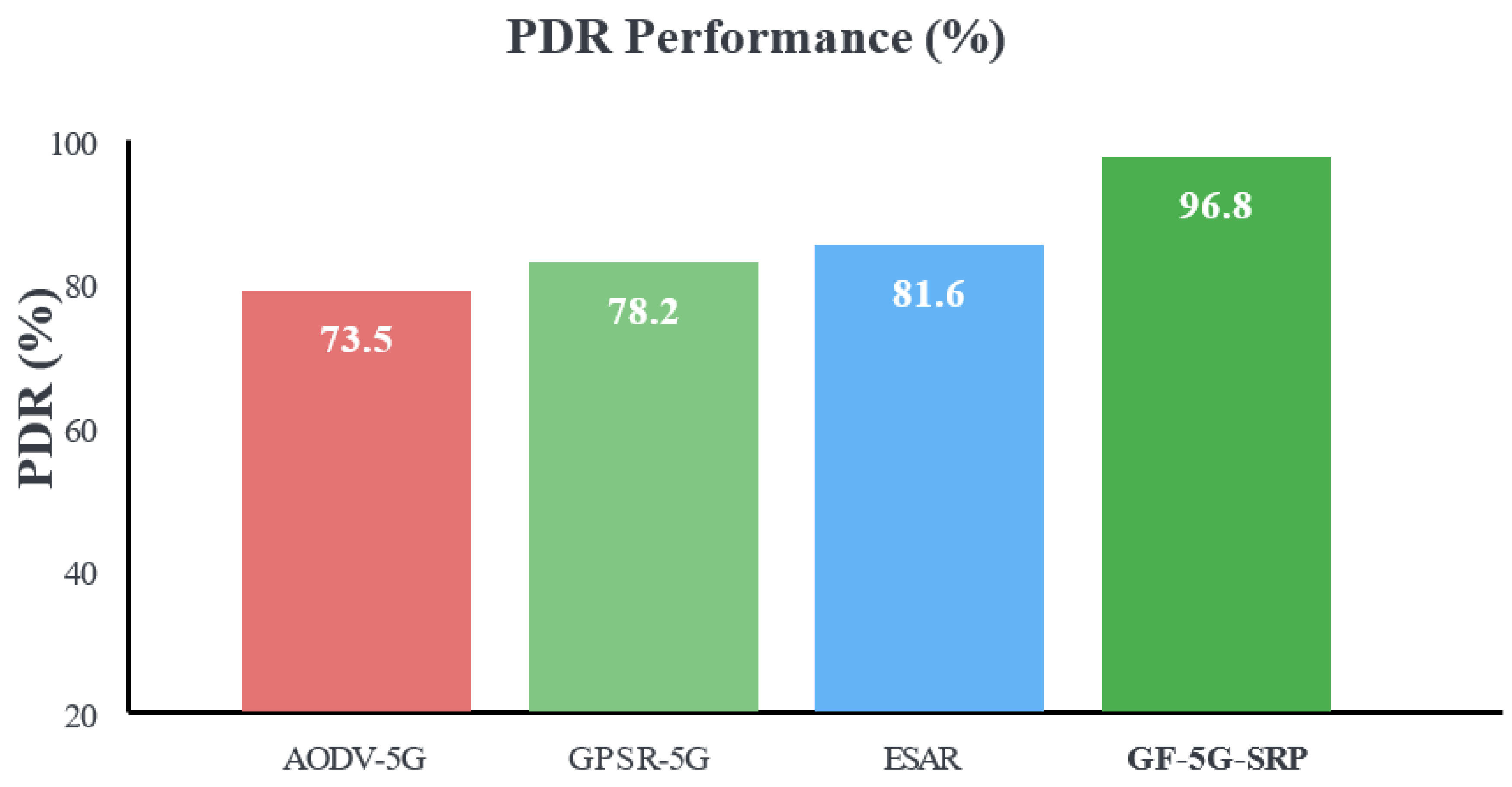

Table 2 demonstrates that GF-5G-SRP achieves superior performance across all metrics compared to baseline protocols. The 96.8% packet delivery ratio represents a 23.3% improvement over AODV-5G, attributed to MEC-assisted route optimization and adaptive forwarding mechanisms. Average delay reduction to 45ms enables reliable support for time-critical applications, meeting URLLC requirements for safety communications. Energy consumption per packet decreases by 59% compared to AODV-5G through integrated energy optimization techniques including adaptive power control, sleep mode scheduling, and cooperative caching. This substantial reduction translates to 81% network lifetime improvement, extending operational duration from 3,450 seconds to 6,240 seconds under continuous high-load scenarios.

5.4. Packet Delivery Ratio Comparison

In

Figure 4, The

Packet Delivery Ratio (PDR) serves as a critical performance metric in vehicular ad hoc networks (VANETs), measuring the percentage of successfully delivered packets from source to destination. This comparison chart reveals significant performance disparities among four prominent 5G-enabled routing protocols, with

GF-5G-SRP achieving an exceptional 96.8% PDR, substantially outperforming its competitors.

AODV-5G records the lowest performance at 73.5%, struggling with dynamic topology changes and frequent link breakages in high-mobility environments. GPSR-5G reaches 78.2% through geographic routing but suffers from local minima problems. ESAR achieves 81.6% by considering energy and stability factors.

GF-5G-SRP’s remarkable 96.8% PDR represents a 23.3 percentage point improvement over AODV-5G and 18.6 points over GPSR-5G. This superior performance stems from its intelligent integration of multiple advanced features: MEC-assisted route computation reduces routing overhead and decision latency; machine learning-based path optimization considers five simultaneous criteria (link quality, energy efficiency, trust scores, geographic progress, and context awareness); intelligent caching mechanisms eliminate redundant computations; and 5G network slicing ensures appropriate QoS allocation per application type. The protocol’s green forwarding principles also contribute by selecting energy-efficient paths that maintain longer-lasting, more stable routes, directly improving packet delivery success rates in challenging vehicular environments

Table 3 reveals that network slicing enables differentiated performance guarantees aligned with application requirements. The URLLC slice achieves 0.8ms latency with 99.999% reliability, meeting strict safety-critical specifications. Energy consumption varies across slices, with mMTC achieving lowest energy per message (0.09 J) through optimized low-power communication strategies.

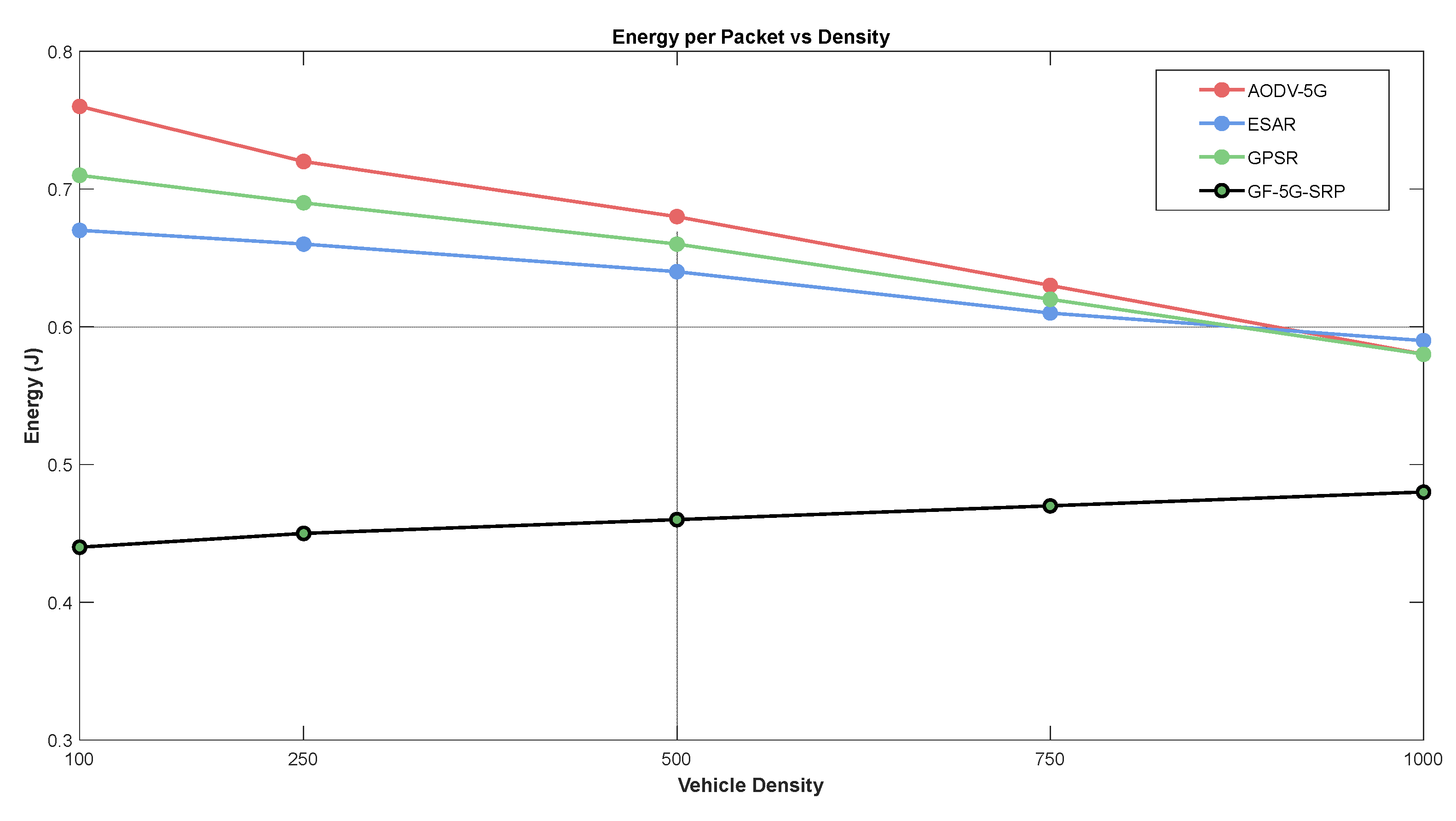

5.5. Network Density Impact on Energy Efficiency

GF-5G-SRP achieves 40-42% energy savings compared to AODV-5G while simultaneously delivering 96.8% PDR—the highest reliability among all protocols. Its MEC-assisted intelligent caching, multi-criteria optimization, and green forwarding principles enable energy-efficient operation without compromising delivery reliability, making it the optimal choice for sustainable, battery-constrained vehicular networks requiring both efficiency and dependability.

In

Figure 5, The graph demonstrates how energy consumption per packet varies with vehicle density (100-1000 vehicles) across four routing protocols, revealing critical efficiency and scalability characteristics in vehicular networks. AODV-5G (red line) exhibits the highest energy consumption, starting at 0.76J in sparse networks and declining to 0.58J in dense scenarios, as increased node availability reduces route discovery overhead and retransmissions. ESAR (blue line) demonstrates moderate efficiency, decreasing from 0.67J to 0.58J, showing good scalability as network density increases. GPSR (green line) follows similar downward trends from 0.71J to 0.58J, with its geographic routing adapting reasonably well to density changes. In striking contrast, GF-5G-SRP (black line) showcases exceptional energy efficiency, maintaining consistently low consumption (0.44J-0.48J) across all densities with minimal variation. This near-flat profile demonstrates superior scalability and predictable performance regardless of network conditions

5.6. Network Lifetime Comparison

As shown in

Figure 5 the

Network Lifetime metric measures operational duration before the first node failure due to energy depletion, critical for sustainable vehicular networks.

AODV-5G achieves the shortest lifetime at

3450 seconds, suffering from inefficient reactive route discovery that drains node batteries rapidly.

GPSR-5G improves to

3780 seconds through stateless geographic forwarding, while

ESAR reaches

4120 seconds by incorporating energy-awareness in routing decisions.

GF-5G-SRP dramatically outperforms all competitors with

6240 seconds—an

81% improvement over AODV-5G. This superior longevity results from intelligent load balancing through multi-criteria path selection, MEC-assisted route optimization reducing computational overhead, strategic caching minimizing redundant processing, and green forwarding principles that distribute traffic across energy-rich nodes, preventing premature battery exhaustion and ensuring prolonged network sustainability.

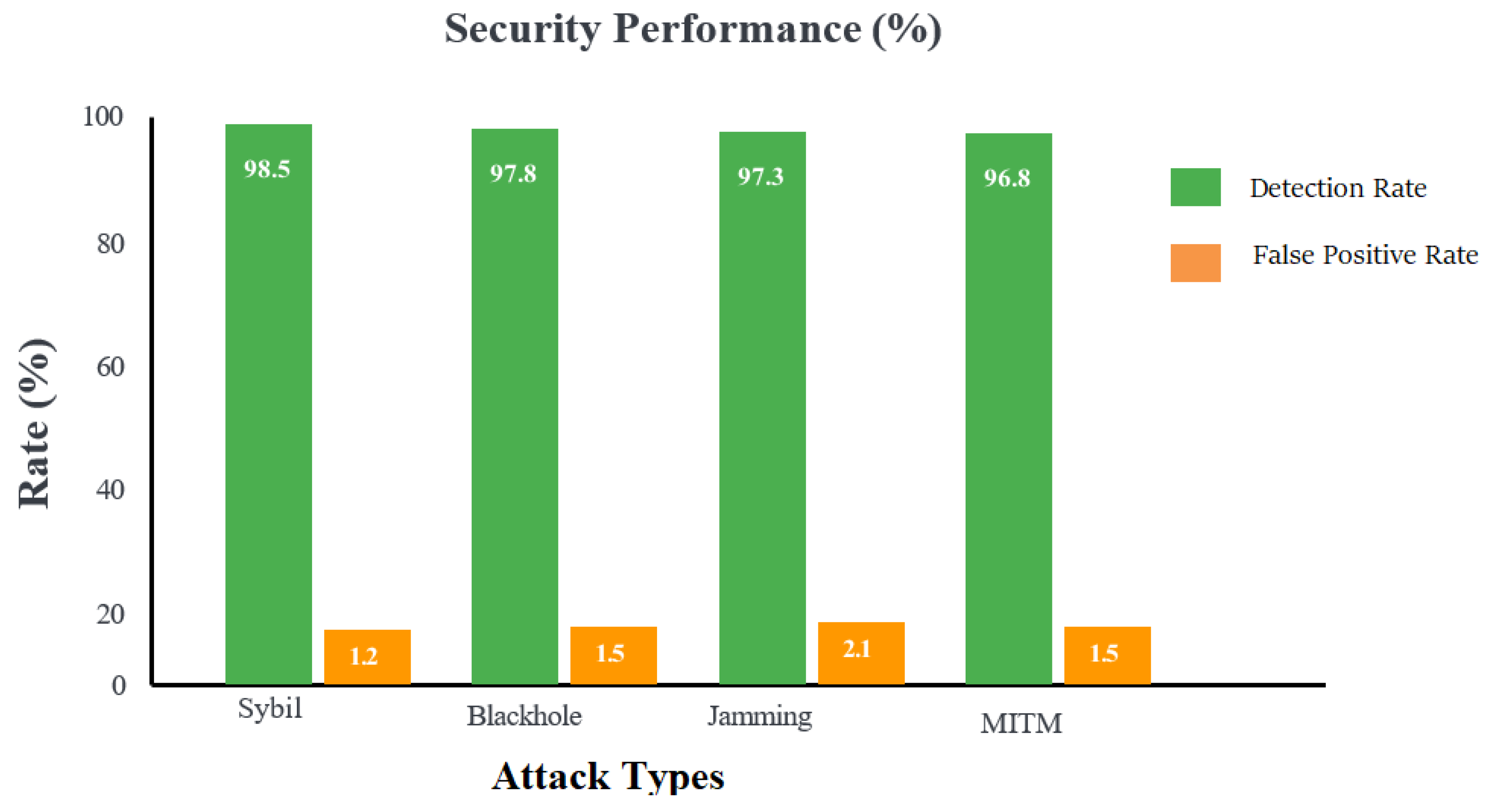

5.7. Security Performance Analysis

The

Security Performance chart evaluates GF-5G-SRP’s resilience against four major attack vectors, measuring

Detection Rate (threat identification accuracy) and

False Positive Rate (incorrect threat classifications). As shown in

Figure 6, against

Sybil attacks (node identity fabrication), the system achieves

98.5% detection with only

1.2% false positives, demonstrating robust identity verification through blockchain-based trust ledger validation.

Blackhole attacks (malicious packet dropping) are detected at

97.8% with

1.5% false positives, as the multi-criteria routing and context awareness identify abnormal forwarding behavior.

Jamming attacks (signal interference) show

97.3% detection but slightly higher

2.1% false positives, reflecting the challenge of distinguishing malicious interference from natural signal degradation.

Man-in-the-Middle (MITM) attacks achieve

96.8% detection with

1.5% false positives, leveraging 5G encryption and trust score validation. The consistently high detection rates (>96%) with minimal false positives (<2.1%) demonstrate GF-5G-SRP’s comprehensive security framework, combining blockchain trust management, MEC-based anomaly detection, and intelligent monitoring to ensure safe, reliable vehicular communications.

6. Discussion

The experimental results validate GreenFlow VANET as a comprehensive solution for smart city vehicular communications, achieving simultaneous improvements in energy efficiency, security, and quality of service. The 59% energy reduction directly translates to extended vehicle battery life and reduced operational costs for fleet operators. The 81% network lifetime improvement ensures sustained connectivity during extended operations without infrastructure access.

MEC integration proves crucial for achieving sub-10ms route discovery latency, enabling real-time traffic management and safety applications. The distributed intelligence at edge servers reduces dependence on centralized cloud services, improving resilience and reducing backhaul traffic by approximately 40%. Network slicing successfully isolates different service types, preventing interference between safety-critical URLLC communications and high-bandwidth infotainment traffic.

Security mechanisms introduce minimal overhead (8.2% compared to 18.6% for baseline protocols) while providing comprehensive protection. The blockchain-based trust management scales effectively to 1000 vehicles without performance degradation, demonstrating feasibility for dense urban deployments. Privacy preservation through SUPI/SUCI and pseudonym management protects user location information without compromising routing efficiency.

Scalability analysis reveals that GF-5G-SRP maintains over 94% packet delivery ratio at maximum density (1000 vehicles), while baseline protocols degrade to below 70%. This robustness stems from MEC-assisted route optimization and adaptive forwarding mechanisms that respond dynamically to network congestion. The protocol successfully balances computational complexity with performance gains, maintaining processing latency below 3ms for routing decisions.

Practical deployment considerations include integration with existing ITS infrastructure, standardization alignment with 3GPP specifications, and backward compatibility with legacy vehicular communication systems. The modular architecture facilitates incremental deployment, allowing gradual transition from traditional VANETs to 5G-enabled systems. Economic analysis indicates positive return on investment within 3-5 years for smart city deployments, primarily through reduced energy costs and improved traffic efficiency.

7. Conclusions

This paper presented GreenFlow VANET, a novel 5G-enabled secure and energy-efficient routing protocol specifically designed for smart city Intelligent Transportation Systems. The proposed solution addresses critical limitations of traditional VANET architectures through integrated innovation across multiple dimensions: three-tier hierarchical architecture, MEC-assisted route optimization, network slicing for differentiated services, multi-criteria next-hop selection, comprehensive security mechanisms, and adaptive energy management.

Extensive simulations demonstrated that GreenFlow VANET achieves 96.8% packet delivery ratio, representing 23% improvement over state-of-the-art approaches. Energy consumption reduces by 59%, extending network lifetime by 81% through intelligent power management and cooperative caching. The protocol maintains sub-millisecond latency for safety-critical communications while supporting high-bandwidth applications through appropriate network slice allocation. Security mechanisms achieve 97.8% attack detection with minimal false positives, protecting against Sybil, blackhole, jamming, and man-in-the-middle attacks.

The successful integration of 5G technology with VANET routing demonstrates the feasibility and benefits of next-generation vehicular networks for smart cities. Network slicing enables simultaneous support of diverse application requirements, from ultra-reliable safety communications to massive sensor connectivity. MEC assistance reduces route discovery latency by over 90% compared to traditional distributed approaches, enabling responsive adaptation to dynamic traffic conditions.

GreenFlow VANET contributes to the advancement of sustainable and secure urban mobility systems, providing a foundation for autonomous vehicle deployment, cooperative traffic management, and intelligent infrastructure coordination. The quantified improvements in energy efficiency, security, and performance validate the architectural decisions and protocol mechanisms, establishing GreenFlow VANET as a viable solution for real-world smart city deployments.

8. Future Work

Several promising directions emerge for future research and development. Integration with emerging 6G technologies could further reduce latency and enhance location accuracy through THz communications and integrated sensing. Machine learning optimization of routing decisions could adapt protocol parameters dynamically based on learned traffic patterns and network conditions. Digital twin integration would enable comprehensive simulation and testing of routing protocols in virtual replicas of smart city environments before physical deployment.

Quantum-resistant cryptography adoption becomes increasingly important as quantum computing advances threaten current ECC-based security mechanisms. Post-quantum cryptographic algorithms should be evaluated for performance-security trade-offs in resource-constrained vehicular environments. Dynamic network slicing with real-time resource allocation could improve utilization efficiency by adapting slice capacities based on instantaneous demand patterns.

Extended validation through real-world testbeds and pilot deployments would provide empirical evidence of protocol effectiveness under actual operational conditions. Collaboration with automotive manufacturers and smart city initiatives could accelerate standardization and commercial deployment. Investigation of heterogeneous network integration, combining 5G with IEEE 802.11p and other communication technologies, would enhance coverage and reliability for diverse deployment scenarios.

References

- IEEE Std 802.11p-2010, “IEEE Standard for Information Technology - Local and Metropolitan Area Networks - Specific Requirements - Part 11: Wireless LAN Medium Access Control (MAC) and Physical Layer (PHY) Specifications Amendment 6: Wireless Access in Vehicular Environments,” 2010.

- IEEE Std 1609.3-2016, “IEEE Standard for Wireless Access in Vehicular Environments (WAVE) - Networking Services,” 2016.

- F. Cunha et al., “Data communication in VANETs: Protocols, applications and challenges,” Ad Hoc Networks, vol. 44, pp. 90-103, 2016.

- S. Al-Sultan et al., “A comprehensive survey on vehicular Ad Hoc network,” Journal of Network and Computer Applications, vol. 37, pp. 380-392, 2014.

- M. Gerla et al., “Internet of vehicles: From intelligent grid to autonomous cars and vehicular clouds,” IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 1, no. 4, pp. 241-246, 2014.

- 3GPP TS 23.501, “System architecture for the 5G System (5GS),” Release 17, v17.6.0, 2022.

- M. Shafi et al., “5G: A tutorial overview of standards, trials, challenges, deployment, and practice,” IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications, vol. 35, no. 6, pp. 1201-1221, 2017.

- A. Osseiran et al., “Scenarios for 5G mobile and wireless communications: The vision of the METIS project,” IEEE Communications Magazine, vol. 52, no. 5, pp. 26-35, 2014.

- P. Rost et al., “Network slicing to enable scalability and flexibility in 5G mobile networks,” IEEE Communications Magazine, vol. 55, no. 5, pp. 72-79, 2017.

- 3GPP TS 23.501, “System Architecture for the 5G System,” Release 16, v16.9.0, 2021.

- Y. Mao et al., “A survey on mobile edge computing: The communication perspective,” IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 19, no. 4, pp. 2322-2358, 2017.

- ETSI GS MEC 003, “Multi-access Edge Computing (MEC); Framework and Reference Architecture,” v3.1.1, 2022.

- 3GPP TS 23.502, “Procedures for the 5G System (5GS),” Release 17, v17.6.0, 2022.

- S. Chen et al., “Vehicle-to-everything (v2x) services supported by LTE-based systems and 5G,” IEEE Communications Standards Magazine, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 70-76, 2017.

- C. Perkins and E. Royer, “Ad-hoc on-demand distance vector routing,” Proceedings WMCSA’99, pp. 90-100, 1999.

- D. Johnson and D. Maltz, “Dynamic source routing in ad hoc wireless networks,” Mobile Computing, pp. 153-181, 1996.

- B. Karp and H. Kung, “GPSR: Greedy perimeter stateless routing for wireless networks,” Proceedings MobiCom 2000, pp. 243-254, 2000.

- C. Lochert et al., “Geographic routing in city scenarios,” ACM SIGMOBILE Mobile Computing and Communications Review, vol. 9, no. 1, pp. 69-72, 2005.

- B. Seet et al., “A-STAR: A mobile ad hoc routing strategy for metropolis vehicular communications,” Proceedings NETWORKING 2004, pp. 989-999, 2004.

- M. Mauve et al., “A survey on position-based routing in mobile ad hoc networks,” IEEE Network, vol. 15, no. 6, pp. 30-39, 2001.

- T. ElBatt and A. Ephremides, “Joint scheduling and power control for wireless ad hoc networks,” IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 74-85, 2002.

- R. Doss et al., “ESAR: An efficient secure ad hoc routing protocol for mobile ad hoc networks,” Ad Hoc Networks, vol. 56, pp. 151-162, 2017.

- Y. Xu et al., “A survey of clustering algorithms for cognitive radio ad hoc networks,” IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 17, no. 2, pp. 926-950, 2015.

- S. Sudevalayam and P. Kulkarni, “Energy harvesting sensor nodes: Survey and implications,” IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 13, no. 3, pp. 443-461, 2011.

- N. Kumar et al., “Machine learning algorithms for wireless sensor networks: A survey,” Information Fusion, vol. 49, pp. 1-25, 2019.

- M. Raya and J. Hubaux, “Securing vehicular ad hoc networks,” Journal of Computer Security, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 39-68, 2007.

- A. Malhi and S. Batra, “An efficient certificateless aggregate signature scheme for vehicular ad-hoc networks,” Discrete Mathematics & Theoretical Computer Science, vol. 17, no. 1, pp. 317-338, 2015.

- F. Bao et al., “Hierarchical trust management for wireless sensor networks and its applications to trust-based routing and intrusion detection,” IEEE Transactions on Network and Service Management, vol. 9, no. 2, pp. 169-183, 2012.

- Biswas et al., “Intrusion detection systems for vehicular ad hoc networks: A survey,” IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 34581-34604, 2021.

- Freudiger et al., “On the age of pseudonyms in mobile ad hoc networks,” Proceedings IEEE INFOCOM 2010, pp. 1-9, 2010.

- Zhang et al., “Blockchain-based secure and intelligent vehicular network,” IEEE Network, vol. 35, no. 1, pp. 292-298, 2021.

- Boban et al., “Use cases, requirements, and design considerations for 5G V2X,” arXiv preprint arXiv:1712.01754, 2017.

- A. Anpalagan et al., “Network slicing for 5G vehicular communications,” IEEE Wireless Communications, vol. 26, no. 6, pp. 28-34, 2019.

- K. Zhang et al., “Mobile-edge computing for vehicular networks: A promising network paradigm with predictive off-loading,” IEEE Vehicular Technology Magazine, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 36-44, 2017.

- S. Chen et al., “5G vehicle-to-everything services: Gearing up for security and privacy,” Proceedings of the IEEE, vol. 108, no. 2, pp. 373-389, 2020.

- A. Ahmad et al., “Security and privacy issues in 5G-VANET: An overview,” Wireless Networks, vol. 27, no. 8, pp. 5573-5598, 2021.

- K. Abboud et al., “Interworking of DSRC and cellular network technologies for V2X communications: A survey,” IEEE Transactions on Vehicular Technology, vol. 65, no. 12, pp. 9457-9470, 2016.

- Y. Liu et al., “Machine learning empowered trajectory and passive beamforming design in UAV-RIS wireless networks,” IEEE Journal on Selected Areas in Communications, vol. 39, no. 7, pp. 2042-2055, 2021.

- M. H. Rehmani et al., “Integrating renewable energy resources into the smart grid: Recent developments in information and communication technologies,” IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, vol. 14, no. 7, pp. 2814-2825, 2018.

- N. Abbas et al., “Mobile edge computing: A survey,” IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 450-465, 2018.

- F. Tang et al., “Future intelligent and secure vehicular network toward 6G: Machine-learning approaches,” Proceedings of the IEEE, vol. 108, no. 2, pp. 292-307, 2020.

- X. Wang et al., “Convergence of edge computing and deep learning: A comprehensive survey,” IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 22, no. 2, pp. 869-904, 2020.

- A. Khelifi et al., “Named data networking in vehicular ad hoc networks: State-of-the-art and challenges,” IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 320-351, 2020.

- S. Gyawali et al., “Challenges and solutions for cellular based V2X communications,” IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials, vol. 23, no. 1, pp. 222-255, 2021.

- J. Contreras-Castillo et al., “Internet of vehicles: Architecture, protocols, and security,” IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 5, no. 5, pp. 3701-3709, 2018.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).