Submitted:

10 December 2025

Posted:

11 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Digital mental health uses technology—like the Internet, smartphones, wearables, and immersive platforms—to improve access to care. While these resources quickly expanded post COVID-19, ongoing issues include low user retention, poor digital literacy, unclear privacy rules, and limited proof of effectiveness and safety. AI chatbots, also known as agents and assistants that act as a therapist or companion, support mental health by delivering counseling and personalized interactions through various apps and devices. AI chatbots may boost social health and lower loneliness, however, they may also increase dependence and affect emotional outcomes. Their use remains largely unregulated, with concerns about privacy, bias, and ethics. Experiences vary; some users report positive results while others doubt their safety and impact, especially in crisis response. There is a need to better protect vulnerable users and engage the underserved, with input from various individuals with lived experience on what feels safe, supportive, or harmful when interacting with AI chatbots. Proper evaluation, standardized training by digital navigators, and ethical/clinical guidelines are crucial for safe, engaging and effective adoption of AI in mental health care and support.

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. The Problem

3. Literature Synthesis

3.1. An Overview of Mental Health Chatbots

- Ada is a web-based chatbot that interacts through text, using a rule-based response system. While its targeted disorders are not specified, Ada serves as an accessible digital agent for general mental health support [45].

- AEP is designed for individuals with social communication disorders. It operates on a web-based platform, using text for both input and output. The response generation method is not specified [46].

- Ally targets lifestyle disorders and provides support through both text and embodied conversational agent (ECA) modalities, accepting text and voice input. It is a stand-alone platform with unspecified response generation [46].

- Amazon Alexa assists users dealing with stress, anxiety, depression, and loneliness. It can interact via text and voice on a web-based platform, employing a hybrid response system that blends rule-based and generative techniques [47]

- APE is a text-based, web-based chatbot focused on depression. The response generation method is not detailed [48].

- Automated Social Skills Trainer supports individuals with autism. It features both text and ECA outputs, accepts text and voice inputs, and functions as a stand-alone application with a rule-based response system [50].

- CARO focuses on major depression and operates through text on a web-based platform, utilizing a generative response method [51].

- Carmen addresses lifestyle disorders using text and ECA outputs, with text and voice inputs on a stand-alone platform. The response method is not specified [46].

- CoachAI provides support for lifestyle disorders through text on a stand-alone platform, relying on rule-based responses [52].

- DEPRA is a web-based, text-driven chatbot targeting depression. The response generation approach is not specified [51].

- ePST supports those facing mood disorders, stress, and anxiety through text interactions on a web-based platform, using a rule-based response system [49].

- ELIZA provides stress support via text for problem distress and depression/anxiety/stress [28]. Response generation is not specified.

- Elizabeth is a stand-alone chatbot for depression, providing text and ECA outputs and accepting text and voice inputs, driven by a rule-based response method [50].

- Emohaa provides support for subclinical anxiety and depression via voice and text; response generation is not specified [57].

- Emotion Guru targets depression via text on a web-based platform, employing a generative response approach [51].

- EMMA offers text-based support for depression; details about the platform and response generation are not specified [51].

- Evebot provides generative text responses for depression on a stand-alone platform [51].

- Healthy Lifestyle Coaching Chatbot helps with lifestyle disorders via text on a stand-alone platform; response generation is not specified [46].

- iDecide is a stand-alone chatbot for chronic disorders, using text and ECA outputs and accepting text and voice inputs. The response method is not specified [46].

- iHelpr supports users with depression, anxiety, stress, sleep issues, and self-esteem problems, using text on a web-based platform and rule-based responses [50].

- Jeanne is a stand-alone chatbot for substance use disorder, using text and ECA outputs, with text and voice inputs and a rule-based response system [50].

- Kokopot operates via text on a web-based platform, targeting unspecified disorders with generative responses [50].

- Max addresses chronic disorders through text and ECA outputs, accepts text and voice inputs on a stand-alone platform. Response generation is not specified [46].

- Microsoft Cortana interacts through text and voice on a web-based platform with a hybrid response system, but targeted disorders are not specified [47].

- Minder interacts through text and voice on a web-based platform targeting subclinical depression/anxiety; response generation is not specified [57].

- My Personal Health Guide supports chronic disorders, using text and ECA outputs, accepting text and voice inputs on a stand-alone platform; response generation is not specified [46].

- ODVIC supports substance use disorder through text and ECA outputs on a web-based platform, using rule-based responses [51]

- Owlie offers text-based support for stress, anxiety, depression, and autism on a web-based platform; response generation is not specified [52]

- Paola addresses lifestyle disorders using text and ECA outputs, accepting text and voice inputs on a stand-alone platform; response method not specified [56]

- PrevenDep is a stand-alone chatbot for depression, using text and ECA outputs, accepting text and voice inputs, and relying on rule-based responses [49].

- PRISM supports bipolar disorders via text on a stand-alone platform; response generation is not specified [46].

- Quit Coach assists with lifestyle disorders using text on a stand-alone platform; response method not specified [46].

- Samsung Bixby interacts via text and voice on a web-based platform using a hybrid response approach; targeted disorders are not specified [47].

- SimCoach supports depression and PTSD through text and ECA outputs, accepting text and voice inputs on a web-based platform, using generative responses [50].

- SimSensei Kiosk helps with depression, anxiety, and PTSD using text and ECA outputs and accepting text and voice inputs on a stand-alone platform, relying on rule-based responses [50].

- Sunny supports depression and anxiety via text on a web-based platform; response method not specified [52].

- Steps to Health addresses lifestyle disorders using text and ECA outputs, accepting text and voice inputs on a stand-alone platform; response method not specified [46].

- TEO supports subclinical anxiety and depression through generative text responses on a web-based platform [57].

- TensioBot aids with chronic disorders via text on a web-based platform; response and modality details are not specified [46].

- Thinking Head targets autism using text and ECA outputs, accepting text and voice inputs on a stand-alone platform with rule-based responses [51].

- Vitalk assists with subclinical depression/anxiety in conversational format; response method is not specified [57].

- VR-JIT addresses stress and autism using text and ECA outputs, accepting text and voice inputs on a stand-alone platform with rule-based responses [51].

- Wellthy CARE mobile app is a stand-alone solution for chronic disorders; further details are not specified [46].

- Woebot supports depression and anxiety through text on a web-based platform with a rule-based response system 45-49,51-57].

- XiaoE targets depression, interacting via text, image, and voice on a web-based platform with generative responses [29].

- XiaoNan targets depression, interacting via text and voice on a web-based platform with generative responses [49].

- 3MR is a stand-alone solution for posttraumatic stress disorder, using text and ECA outputs, accepting text and voice inputs, and relying on rule-based responses [51].

3.2. Clinical Risks, Opportunities, and Ethical Issues

- Stakeholder Engagement: Co-design with lived experience is rare, perpetuating cultural mismatches and failure to recognize nuanced distress cues [61]. There is a need for future research to integrate human-in-the-loop mechanisms, enhance cultural adaptation, integrate ethics in the design and implementation of more adaptive and empathetic support from LLMs [32].

- Privacy and Data Security: Concerns persist regarding data use, consent, and the potential for breaches or misuse [62].

3.3. AI Chatbot Applications Used in Mental Health Care and Support

- Self-clone Chatbots are AI agents modeled on users’ own conversational and support styles—as a novel alternative to traditional therapy, designed to externalize inner dialogue and enhance emotional and cognitive engagement [85].

- Mental Health Task Assistants like Mia Health [86] combine psychoeducation, journaling, and real-time analytics to support care professionals across assessment, care planning, and emotion regulation. By integrating psychological expertise with advanced AI, these systems scale efficient, responsive mental health services tailored to individual needs.

- Humanoid/Social robots (e.g., Qhali/Yonbo) are interactive, embodied machines with human-like appearance and/or robot features designed to engage with humans through socially intelligent behaviors—such as speech, gestures, and emotional responsiveness—with the goal of supporting mental health and well-being through companionship, motivation, and therapeutic interventions [87,88,89,90,91,92,93].

3.4. AI Chatbot Phenomena in Mental Health

3.5. AI Chatbot Governance

3.6. AI Chatbot Frameworks

4. Implications for Future Research

4.1. General Overview of AI Chatbots in Mental Health

4.2. Ethical, Clinical, and Design Challenges for AI Mental Health Chatbots

- Structured, Context-Aware Escalation Protocols: Implement clear, auditable pathways for crisis detection and escalation, ensuring that AI systems can reliably identify and respond to self-harm or suicidal ideation.

- Transparent Operation and Explainability: Ensure that chatbot interactions are transparent, with explainable decision-making processes that users and clinicians can review.

- Regular Auditing and Sentiment Analysis: Maintain ongoing monitoring of chatbot responses by qualified professionals to identify and rectify potential ethical or clinical risks.

- Comprehensive User Education: Provide users with clear information about the chatbot’s capabilities, limitations, and escalation procedures, fostering informed and safe engagement.

- Integration with Human Support Networks: Facilitate seamless connections to clinical and peer support pathways, ensuring that users can access appropriate care when needed.

- Continuous Improvement Through Feedback: Use real-world user feedback and longitudinal evaluation to refine protocols and improve chatbot safety and efficacy over time.

4.3. Influence of the Risks of AI Chatbots

4.4. Framework and Strategies for Safe, Inclusive, Effective and Integrative AI Chatbots

- Governance with transparent oversight and ethical guidelines.

- Cultural competence through diverse stakeholder engagement and ongoing training.

- Co-regulation fostering shared responsibility among AI, clinicians, and users.

- Lived experience design via participatory workshops and prototyping.

- Trauma-informed principles prioritizing safety and empowerment.

- Research partnerships for evidence-based interventions.

- Transparency about AI capabilities and data use.

- Continuous feedback loops for iterative improvement.

- Cross-functional collaboration among multidisciplinary teams.

- Responsible deployment focusing on sustainability and real-world impact.

4.5. Future Directions in Emotionally Intelligent Digital Mental Health

5. Conclusions

1. Introduction

2. Core Principles

3. System Architecture

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AEI | Augmented Emotional Intelligence |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| CBT COVID-19 DEI DSM-5 EHR EU GAD 7 GenAI GenAI4MH GDPR GP GPT-4 HL7 FHIR K-10 LLM |

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Coronavirus disease of 2019 Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition Electronic Health Record European Union Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale Generative Artificial Intelligence Generative Artificial Intelligence in Enhancing Mental Healthcare General Data Protection Regulation General Practitioner Generative Pre-trained Transformer 4 Health Level Seven International Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources Kessler 10 Large Language Model |

| MFA NLP OECD PHQ-9 |

Multi-Factor Authentication Natural Language Processing Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development Patient Health Questionnaire |

| RAG | Retrieval Augmented Generation |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trial |

| US | United States |

| UX | User Experience |

Appendix A

- • Clearly define the loneliness and/or mental health problem being solved.

- • Assess if AEI is the optimal solution compared to alternatives.

- • Document the specific role and value of AEI in this context.

- • Obtain consent-based user access aligned with privacy agreements.

- • Confirm model provider compliance with internal data policies.

- • Ensure all personal data sent to the model is documented, minimal, and securely retained.

- • Gather text, speech, and optional visual cues (e.g., tone, expressions).

- • Apply contextual AEI to detect emotions, sentiment, and behavioral patterns in real-time.

- Test outputs for biases (gender, race, etc.).

- Audit for exclusion or harm to sensitive groups.

- Verify if training data is representative.

- Include regular monitoring and auditing protocols.

- Persona mapping through describing experiences and challenges.

- Generate safe, empathetic responses using emotionally intelligent personas.

- Personalize tone and approach using lived-experience protocols.

- Provide disclaimers or accuracy notices when needed.

- Clearly signal when users interact with AI.

- Allow users to edit, retry, or opt out of AI-generated responses.

- Visually label AI content and highlight user rights.

- Test for prompt injection, misuse, or jailbreaking.

- Apply moderation, access controls, logging, and rate limits.

- Enforce storage and reuse policies for AI outputs.

- • Recommend tailored AEI tools or referrals to lived experience peers, coaches, guides based on user state.

- • Receive emotional support and companionship as well as build meaningful connections.

- • Connect to group coaching sessions led by certified coaches to build resilience and healthy habits.

- • Engagement with monthly check-ins and referral to clinical support based on needs.

- • Escalate to mental health care professionals when risk is detected.

- • Ensure escalation pathways are documented and supervised.

- Get explicit consent for deeper interventions or emotional support.

- Maintain strong ethical boundaries, user autonomy, and privacy.

- Monitor post-launch metrics (accuracy, satisfaction, fallbacks).

- Assign responsibility for reviewing incidents or flagged content.

- Update AEI systems based on user feedback and evaluation.

- Secure review by legal, ethics, UX/design, and privacy leads.

- Ensure all affordances, disclosures, and risks are well documented.

Appendix B

Appendix C

Appendix D

| Principle | Implementation Strategy | Clinical Governance Mandate |

| Clinical Oversight | AI should support—not replace—licensed professionals. Escalation protocols must be human-led. | This establishes the non-negotiable Human-in-the-Loop model required for high-risk mental health support, mitigating outcomes associated with autonomous AI failure. |

| Crisis Detection | Real-time monitoring for suicidal ideation, with automatic referral to emergency services. | Operationalizes an escalation pathway by requiring reliable identification and immediate intervention for acute risk signals, addressing risks of suicidality and harm promotion. |

| Bias Mitigation | Diverse training data and fairness audits to prevent cultural or demographic harm. | Ensures the system maintains its effectiveness, cultural competence, and inclusivity for vulnerable cohorts. |

| Transparency | Clear disclosures about AI limitations and non-human status. Avoid anthropomorphism. | A necessary technical countermeasure against “AI psychosis” and the practical risk of emotional dependency by pre-emptively setting appropriate user expectations for the relationship. |

| Ethical Guardrails | Prevent AI from validating harmful ideation or offering technical advice on self-harm. | This principle directly resolves the delusion support issue by imposing content restrictions that prohibit the affirmation or sustainment of maladaptive or harmful beliefs, defining the system’s safe boundaries. |

| Personalization with Limits | Hyper-personalization (e.g., self-clone AI chatbots) must be balanced with safeguards against emotional over-identification. | Sets a clinical boundary on the relational intensity of the AI chatbot, ensuring it remains a functional support system and does not replace essential human connections, protecting vulnerable users from unhealthy dependency. |

Appendix E

- Interoperability Standards: Use established protocols such as HL7FHIR to ensure seamless and secure data exchange between chatbots and EHR platforms.

- Modular Architecture: Implement modular chatbot components that can interface with EHRs via secure Application Programming Interfaces (APIs), allowing for flexible deployment and easier updates.

- Role-Based Access: Restrict chatbot access to relevant EHR modules based on user roles (e.g., clinician, patient, administration), minimizing unnecessary data exposure.

- Consent-Driven Memory: Chatbots should only retain or transmit data with explicit user consent, enabling users to control what information is shared with EHRs.

- Granular Access Controls: Implement fine-grained permissions to determine who can view, edit, or export sensitive mental health data.

- Comprehensive Audit Trails: Maintain immutable logs of all chatbot-EHR interactions, including data access, modifications, and transfers, to support accountability and traceability.

- Stakeholder Engagement: Involve clinicians, IT teams, legal experts, and patients in the design and integration process to address diverse needs and compliance requirements.

- Risk Assessment: Conduct a privacy impact assessment to identify potential risks and mitigation strategies before integration.

- Consent Management: Develop clear consent protocols and user interfaces that inform patients about data collection, usage, and sharing.

- Secure API Integration: Use secure API gateways with authentication and authorization mechanisms to connect chatbots to EHRs.

- Testing and Validation: Rigorously test the integration for data integrity, security vulnerabilities, and workflow compatibility before go-live.

- Ongoing Monitoring: Establish continuous monitoring for anomalies, unauthorized access, and system performance issues.

- Encryption: Encrypt all data in transit (using Transport Layer Security 1.2/1.3 or higher) and at rest (using Advanced Encryption Standard-256 or equivalent standards).

- Secure Authentication: Require multi-factor authentication (MFA) for all users accessing chatbot-EHR interfaces.

- Secure APIs: Implement API security best practices, including input validation, rate limiting, and regular security patching.

- Tokenization: Replace sensitive identifiers with tokens during transfer to limit exposure in case of interception.

- Data Loss Prevention (DLP): Deploy DLP solutions to monitor, detect, and block unauthorized data transfers or leaks.

- Intrusion Detection and Prevention Systems (IDPS): Use IDPS to identify and respond to suspicious activity or breaches in real time.

- Secure Cloud Storage: Store chatbot and EHR data within Australian-compliant, ISO-certified cloud environments with strong physical and logical security controls.

- Regular Security Audits: Schedule independent audits and penetration testing to uncover vulnerabilities and ensure compliance with relevant standards (e.g., Australian Privacy Principles, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act where applicable).

- Data Minimization and Retention Policies: Limit data collection to what is necessary and define retention periods aligned with legal and clinical needs.

- Adopt a privacy-by-design approach from the outset of integration planning.

- Provide ongoing security training for staff and users interacting with chatbot-EHR systems.

- Regularly review and update consent forms, privacy notices, and data governance policies.

- Engage in transparent communication with users about data usage, AI capabilities, and escalation protocols.

- Establish clear escalation pathways for technical issues and potential breaches, including rapid notification and remediation procedures.

Appendix F

- Mental health care plans;

- Referrals to mental health resources e.g., Australia’s Head to Health for navigation through face-to-face, phone, and online mental health support.

References

- Balcombe, L.; De Leo, D. Digital Mental Health Amid COVID-19. Encyclopedia 2021, 1(4), 1047–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehtimaki, S.; Martic, J.; Wahl, B.; Foster, K. T.; Schwalbe, N. Evidence on Digital Mental Health Interventions for Adolescents and Young People: Systematic Overview. JMIR Mental Health 2021, 8(4), e25847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcombe, L.; De Leo, D. The Potential Impact of Adjunct Digital Tools and Technology to Help Distressed and Suicidal Men: An Integrative Review. Frontiers in Psychology 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer-Grote, L.; Fössing, V.; Aigner, M.; Fehrmann, E.; Boeckle, M. Effectiveness of Online and Remote Interventions for Mental Health in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults After the Onset of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JMIR Mental Health 2024, 11, e46637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, S.; Mehta, U. M.; Naslund, J.; Torous, J. Translating Digital Health into the Real World: The Evolving Role of Digital Navigators to Enhance Mental Health Access and Outcomes. Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodner, R.; Lim, K.; Schneider, R.; Torous, J. Efficacy and risks of artificial intelligence chatbots for anxiety and depression: a narrative review of recent clinical studies. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcombe, L.; De Leo, D. Digital Mental Health Challenges and the Horizon Ahead for Solutions. JMIR Mental Health 2021, 8(3), e26811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denecke, K.; Abd-Alrazaq, A.; Househ, M. Artificial Intelligence for Chatbots in Mental Health: Opportunities and Challenges. In Multiple Perspectives on Artificial Intelligence in Healthcare; 2021; pp. 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcombe, L.; De Leo, D. Human-Computer Interaction in Digital Mental Health. Informatics 2022, 9(1), 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, K. A.; Blease, C.; Faurholt-Jepsen, M.; Firth, J.; Van Daele, T.; Moreno, C.; Carlbring, P.; Ebner-Priemer, U. W.; Koutsouleris, N.; Riper, H.; Mouchabac, S.; Torous, J.; Cipriani, A. Digital mental health: challenges and next steps. BMJ mental health 2023, 26(1), e300670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddals, S.; Torous, J.; Coxon, A. “It happened to be the perfect thing”: experiences of generative AI chatbots for mental health. Npj Mental Health Research 2024, 3(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wisniewski, H.; Gorrindo, T.; Rauseo-Ricupero, N.; Hilty, D.; Torous, J. The Role of Digital Navigators in Promoting Clinical Care and Technology Integration into Practice. In Digital Biomarkers; Portico, 2020; Volume 4, Suppl. 1, pp. 119–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben-Zeev, D.; Tauscher, J.; Sandel-Fernandez, D.; Buck, B.; Kopelovich, S.; Lyon, A. R.; Chwastiak, L.; Marcus, S. C. Implementing mHealth for Schizophrenia in Community Mental Health Settings: Hybrid Type 3 Effectiveness-Implementation Trial. Psychiatric Services 2025, 76(12), 1091–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghouts, J.; Pretorius, C.; Ayobi, A.; Abdullah, S.; Eikey, E. V. Editorial: Factors influencing user engagement with digital mental health interventions. Frontiers in Digital Health 2023, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, E.M.; Raiker, J.S. Engagement and retention in digital mental health interventions: a narrative review. BMC Digit Health 2024, 2, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auf, H.; Svedberg, P.; Nygren, J.; Nair, M.; Lundgren, L. E. The Use of AI in Mental Health Services to Support Decision-Making: Scoping Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2025, 27, e63548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahsepar Meadi, M.; Sillekens, T.; Metselaar, S.; van Balkom, A.; Bernstein, J.; Batelaan, N. Exploring the Ethical Challenges of Conversational AI in Mental Health Care: Scoping Review. JMIR Mental Health 2025, 12, e60432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, P.-L.; Kuo, W.-C.; Tseng, B.-L.; Sung, Y.-H. Does the AI-driven Chatbot Work? Effectiveness of the Woebot app in reducing anxiety and depression in group counseling courses and student acceptance of technological aids. Current Psychology 2025, 44(9), 8133–8145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, Y.; Jia, F. A Scoping Review of AI-Driven Digital Interventions in Mental Health Care: Mapping Applications Across Screening, Support, Monitoring, Prevention, and Clinical Education. Healthcare 2025, 13(10), 1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balcombe, L. AI Chatbots in Digital Mental Health. Informatics 2023, 10(4), 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabacińska, K.; Dosso, J. A.; Vu, K.; Prescott, T. J.; Robillard, J. M. Influence of User Personality Traits and Attitudes on Interactions With Social Robots: Systematic Review. Collabra: Psychology 2025, 11(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, M. V.; Mackin, D. M.; Trudeau, B. M.; Bhattacharya, S.; Wang, Y.; Banta, H. A.; Jewett, A. D.; Salzhauer, A. J.; Griffin, T. Z.; Jacobson, N. C. Randomized Trial of a Generative AI Chatbot for Mental Health Treatment. NEJM AI 2025, 2(4). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazanov, G.; Poupard, M.; Last, B. S. Public Responses to the First Randomized Controlled Trial of a Generative Artificial Intelligence Mental Health Chatbot. Available from. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Scammell, R. Microsoft AI CEO says AI models that seem conscious are coming. Here’s why he’s worried. Business Insider via MSN. 2025. Available online: https://www.msn.com/en-au/news/techandscience/microsoft-ai-ceo-says-ai-models-that-seem-conscious-are-coming-here-s-why-he-s-worried/ar-AA1KSzUs.

- De Freitas, J.; Uğuralp, A. K.; Oğuz--Uğuralp, Z.; Puntoni, S. Chatbots and mental health: Insights into the safety of generative AI. In Journal of Consumer Psychology; Portico, 2023; Volume 34, 3, pp. 481–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moylan, K.; Doherty, K. Expert and Interdisciplinary Analysis of AI-Driven Chatbots for Mental Health Support: Mixed Methods Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2025, 27, e67114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, R.; Lee, Y.-C.; Kraut, R. E.; Mohr, D. C. Systematic review and meta-analysis of AI-based conversational agents for promoting mental health and well-being. Npj Digital Medicine 2023, 6(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casu, M.; Triscari, S.; Battiato, S.; Guarnera, L.; Caponnetto, P. AI Chatbots for Mental Health: A Scoping Review of Effectiveness, Feasibility, and Applications. Applied Sciences 2024, 14(13), 5889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Lai, A.; Thygesen, J. H.; Farrington, J.; Keen, T.; Li, K. Large Language Models for Mental Health Applications: Systematic Review. JMIR Mental Health 2024, 11, e57400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olawade, D. B.; Wada, O. Z.; Odetayo, A.; David-Olawade, A. C.; Asaolu, F.; Eberhardt, J. Enhancing mental health with Artificial Intelligence: Current trends and future prospects. Journal of Medicine, Surgery, and Public Health 2024, 3, 100099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.; Siddals, S.; Ma, Z.; Galatzer-Levy, I.; Xia, W.; Hau, C.; Na, H.; Flathers, M.; Linardon, J.; Ayubcha, C.; Torous, J. Charting the evolution of artificial intelligence mental health chatbots from rule-based systems to large language models: a systematic review. World psychiatry: official journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA) 2025, 24(3), 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamrin, S.I.; Omar, N.F.; Ngah, R.; Bakhodirovich, G.S.; Absamatovna, K.G. The Applications of AI-Powered Chatbots in Delivering Mental Health Support: A Systematic Literature Review. In Internet of Things, Smart Spaces, and Next Generation Networks and Systems. ruSMART NEW2AN 2024 2024. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Koucheryavy, Y., Aziz, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, 2026; vol 15555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayor, E. Chatbots and mental health: a scoping review of reviews. Current Psychology 2025, 44(15), 13619–13640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cross, S.; Bell, I.; Nicholas, J.; Valentine, L.; Mangelsdorf, S.; Baker, S.; Titov, N.; Alvarez-Jimenez, M. Use of AI in Mental Health Care: Community and Mental Health Professionals Survey. JMIR Mental Health 2024, 11, e60589–e60589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rousmaniere, T.; Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Shah, S. Large language models as mental health resources: Patterns of use in the United States. Practice Innovations. Available from. 2025. [CrossRef]

- OpenAI. Strengthening ChatGPT’s responses in sensitive conversations. 2025. Available online: https://openai.com/index/strengthening-chatgpt-responses-in-sensitive-conversations/.

- Wang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, G. The Application and Ethical Implication of Generative AI in Mental Health: Systematic Review. JMIR Mental Health 2025, 12, e70610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, R.; Gelling, A.; Jackson, M.; Verbeek-Martin, E.; Millet, S.; Mallet, W.; Powell Thomas, G.; Bothwell, S.; Brideson, T.; Brown, T.; Reavley, N. Digital Navigation Project Recommendations Report. SANE and Nous Group. 2025). Digital Navigation Project Recommendations Report. SANE and Nous Group. Available from: https://www.sane.org/digitalnav (viewed on 2 December, 2025. Available online: https://www.sane.org/digitalnav.

- Hipgrave, L.; Goldie, J.; Dennis, S.; Coleman, A. Balancing risks and benefits: clinicians’ perspectives on the use of generative AI chatbots in mental healthcare. Frontiers in Digital Health 2025, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Australian Government. Tech Trends Position Statement Generative AI. Available from: Generative AI - Position Statement - August 2023.pdf. viewed on. 2025.

- Demiris, G.; Oliver, D.P.; Washington, K.T. The Foundations of Behavioral Intervention Research in Hospice and Palliative Care. In Behavioral Intervention Research in Hospice and Palliative Care; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Inkster, B.; Sarda, S.; Subramanian, V. An Empathy-Driven, Conversational Artificial Intelligence Agent (Wysa) for Digital Mental Well-Being: Real-World Data Evaluation Mixed-Methods Study. JMIR mHealth and uHealth 2018, 6(11), e12106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karkosz, S.; Szymański, R.; Sanna, K.; Michałowski, J. Effectiveness of a Web-based and Mobile Therapy Chatbot on Anxiety and Depressive Symptoms in Subclinical Young Adults: Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Formative Research 2024, 8, e47960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A.; Niles, A. N.; Vargas, J. H.; Marafon, T.; Couto, D. D.; Gross, J. J. Acceptability and Effectiveness of Artificial Intelligence Therapy for Anxiety and Depression (Youper): Longitudinal Observational Study. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2021, 23(6), e26771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaidyam, A. N.; Linggonegoro, D.; Torous, J. Changes to the Psychiatric Chatbot Landscape: A Systematic Review of Conversational Agents in Serious Mental Illness: Changements du paysage psychiatrique des chatbots: une revue systématique des agents conversationnels dans la maladie mentale sérieuse. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 2020, 66(4), 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinengo, L.; Jabir, A. I.; Goh, W. W. T.; Lo, N. Y. W.; Ho, M.-H. R.; Kowatsch, T.; Atun, R.; Michie, S.; Tudor Car, L. Conversational Agents in Health Care: Scoping Review of Their Behavior Change Techniques and Underpinning Theory. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2022, 24(10), e39243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogilvie, L.; Prescott, J.; Carson, J. The Use of Chatbots as Supportive Agents for People Seeking Help with Substance Use Disorder: A Systematic Review. In European Addiction Research; Portico, 2022; Volume 28, 6, pp. 405–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Yang, L.; Qian, C.; Li, T.; Su, Z.; Zhang, Q.; Hou, X. Conversational Agent Interventions for Mental Health Problems: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2023, 25, e43862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bérubé, C.; Schachner, T.; Keller, R.; Fleisch, E.; v Wangenheim, F.; Barata, F.; Kowatsch, T. Voice-Based Conversational Agents for the Prevention and Management of Chronic and Mental Health Conditions: Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2021, 23(3), e25933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-Alrazaq, A. A.; Alajlani, M.; Ali, N.; Denecke, K.; Bewick, B. M.; Househ, M. Perceptions and Opinions of Patients About Mental Health Chatbots: Scoping Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2021, 23(1), e17828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Hassan, A.; Aziz, S.; Abd-alrazaq, A. A.; Ali, N.; Alzubaidi, M.; Al-Thani, D.; Elhusein, B.; Siddig, M. A.; Ahmed, M.; Househ, M. Chatbot features for anxiety and depression: A scoping review. Health Informatics Journal 2023, 29(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabir, A. I.; Martinengo, L.; Lin, X.; Torous, J.; Subramaniam, M. Evaluating Conversational Agents for Mental Health: Scoping Review of Outcomes and Outcome Measurement Instruments. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2023, 25, e44548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abd-Alrazaq, A. A.; Rababeh, A.; Alajlani, M.; Bewick, B. M.; Househ, M. Effectiveness and Safety of Using Chatbots to Improve Mental Health: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2020, 22(7), e16021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaffney, H.; Mansell, W.; Tai, S. Conversational Agents in the Treatment of Mental Health Problems: Mixed-Method Systematic Review. JMIR Mental Health 2019, 6(10), e14166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidyam, A. N.; Wisniewski, H.; Halamka, J. D.; Kashavan, M. S.; Torous, J. B. Chatbots and Conversational Agents in Mental Health: A Review of the Psychiatric Landscape. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 2019, 64(7), 456–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd-alrazaq, A. A.; Alajlani, M.; Alalwan, A. A.; Bewick, B. M.; Gardner, P.; Househ, M. An overview of the features of chatbots in mental health: A scoping review. International Journal of Medical Informatics 2019, 132, 103978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, W.; Luo, J.; Zhang, H. The therapeutic effectiveness of artificial intelligence-based chatbots in alleviation of depressive and anxiety symptoms in short-course treatments: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders 2024, 356, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Yang, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhang, X.; Leng, Q.; Zhao, X. Deep learning-based multimodal emotion recognition from audio, visual, and text modalities: A systematic review of recent advancements and future prospects. Expert Systems with Applications 2024, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tornero-Costa, R.; Martinez-Millana, A.; Azzopardi-Muscat, N.; Lazeri, L.; Traver, V.; Novillo-Ortiz, D. Methodological and Quality Flaws in the Use of Artificial Intelligence in Mental Health Research: Systematic Review. JMIR Mental Health 2023, 10, e42045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehbozorgi, R.; Zangeneh, S.; Khooshab, E.; Nia, D. H.; Hanif, H. R.; Samian, P.; Yousefi, M.; Hashemi, F. H.; Vakili, M.; Jamalimoghadam, N.; Lohrasebi, F. The application of artificial intelligence in the field of mental health: a systematic review. BMC psychiatry 2025, 25(1), 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimada, K. The Role of Artificial Intelligence in Mental Health: A Review. Science Insights 2023, 43(5), 1119–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavory, T. Regulating AI in Mental Health: Ethics of Care Perspective. JMIR Mental Health 2024, 11, e58493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laban, G.; Ben-Zion, Z.; Cross, E. S. Social Robots for Supporting Post-traumatic Stress Disorder Diagnosis and Treatment. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pataranutaporn, P.; Liu, R.; Finn, E.; Maes, P. Influencing human–AI interaction by priming beliefs about AI can increase perceived trustworthiness, empathy and effectiveness. Nature Machine Intelligence 2023, 5(10), 1076–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawik, B.; Tobis, S.; Baum, E.; Suwalska, A.; Kropińska, S.; Stachnik, K.; Pérez-Bernabeu, E.; Cildoz, M.; Agustin, A.; Wieczorowska-Tobis, K. Robots for Elderly Care: Review, Multi-Criteria Optimization Model and Qualitative Case Study. Healthcare 2023, 11(9), 1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bravata, D.; Russell, D.; Fellows, A.; Goldman, R.; Pace, E. Digitally Enabled Peer Support and Social Health Platform for Vulnerable Adults With Loneliness and Symptomatic Mental Illness: Cohort Analysis. JMIR Formative Research 2024, 8, e58263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer, R.; Ali, K.; Hughes, C. Using AI-Based Virtual Companions to Assist Adolescents with Autism in Recognizing and Addressing Cyberbullying. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland) 2024, 24(12). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, D. Supportive? Addictive? Abusive? How AI companions affect our mental health. Nature 2025, 641(8062), 296–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewale, M. D.; Muhammad, U. I. From Virtual Companions to Forbidden Attractions: The Seductive Rise of Artificial Intelligence Love, Loneliness, and Intimacy—A Systematic Review. In Official Journal of the Coalition for Technology in Behavioral Science; Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science, 2025; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C.M.; Liu, A.R.; Danry, V.; Lee, E.; Chan, S.W.T.; Pataranutaporn, P.; Maes, P.; Phang, J.; Lampe., M.; Ahmad, L.; Agarwal, S. How AI and Human Behaviors Shape Psychosocial Effects of Chatbot Use: A Longitudinal Randomized Controlled Study. arXiv 2025, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phang, J.; Lampe, M.; Ahmad, L.; Agarwal, S.; Fang, C.M.; Liu, A.R.; Danry, V.; Lee, E.; Chan, S.W.T.; Pataranutaporn, P.; Maes, P. Investigating Affective Use and Emotional Well-being on ChatGPT. arXiv 2025, 1–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Common Sense Media. Talk, Trust, and Trade-Offs: How and Why Teens Use AI Companions. 2025. Available online: https://www.commonsensemedia.org/research/talk-trust-and-trade-offs-how-and-why-teens-use-ai-companions.

- Yu, H. Q.; McGuinness, S. An experimental study of integrating fine-tuned large language models and prompts for enhancing mental health support chatbot system. Journal of Medical Artificial Intelligence 2024, 7, 16–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucher, E. M.; Harake, N. R.; Ward, H. E.; Stoeckl, S. E.; Vargas, J.; Minkel, J.; Zilca, R. Artificially intelligent chatbots in digital mental health interventions: a review. Expert Review of Medical Devices 2021, 18(sup1), 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottesman, O.; Johansson, F.; Komorowski, M.; Faisal, A.; Sontag, D.; Doshi-Velez, F.; Celi, L. A. Guidelines for reinforcement learning in healthcare. Nature Medicine 2019, 25(1), 16–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haque, M. D. R.; Rubya, S. An Overview of Chatbot-Based Mobile Mental Health Apps: Insights From App Description and User Reviews. JMIR mHealth and uHealth 2023, 11, e44838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, H.; Chen, J.; Qiu, Y.; Liu, P.; Liu, Z. The Impact of Human–Chatbot Interaction on Human–Human Interaction: A Substitution or Complementary Effect. International Journal of Human–Computer Interaction 2024, 41(2), 848–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lejeune, A.; Le Glaz, A.; Perron, P.-A.; Sebti, J.; Baca-Garcia, E.; Walter, M.; Lemey, C.; Berrouiguet, S. Artificial intelligence and suicide prevention: A systematic review. European Psychiatry 2022, 65(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratch, I.; Essig, T. A Letter about Randomized Trial of a Generative AI Chatbot for Mental Health Treatment. NEJM AI 2025, 2(9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckman, T. G.; Markowitz, J. C.; Heckman, B. D. A Generative AI Chatbot for Mental Health Treatment: A Step in the Right Direction? NEJM AI 2025, 2(9). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoib, S.; Siddiqui, M. F.; Turan, S.; Chandradasa, M.; Armiya’u, A. Y.; Saeed, F.; De Berardis, D.; Islam, S. M. S.; Zaidi, I. Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning Approach and Suicide Prevention: A Qualitative Narrative Review; Research and Reviews: Preventive Medicine, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chin, M. H.; Afsar-Manesh, N.; Bierman, A. S.; Chang, C.; Ohno-Machado, L. Guiding Principles to Address the Impact of Algorithm Bias on Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health and Health Care. JAMA Network Open 2023, 6(12), e2345050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, J.; Grabb, D.; Agnew, W.; Klyman, K.; Chancellor, S.; Ong, D. C.; Haber, N. Expressing stigma and inappropriate responses prevents LLMs from safely replacing mental health providers. In Proceedings of the 2025 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, 2025; pp. 599–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholich, T.; Barr, M.; Wiltsey Stirman, S.; Raj, S. A Comparison of Responses from Human Therapists and Large Language Model–Based Chatbots to Assess Therapeutic Communication: Mixed Methods Study. JMIR Mental Health 2025, 12, e69709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shirvani, M.S.; Liu, J.; Chao, T.; Martinez, S.; Brandt, L.; Kim, I-J; Dongwook, Y. Talking to an AI Mirror: Designing Self-Clone Chatbots for Enhanced Engagement in Digital Mental Health Support. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health, Mia. Meet Mia. 2025. Available online: https://miahealth.com.au/.

- Scoglio, A. A.; Reilly, E. D.; Gorman, J. A.; Drebing, C. E. Use of Social Robots in Mental Health and Well-Being Research: Systematic Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2019, 21(7), e13322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, S. C. Integrating Emotional AI into Mobile Apps with Smart Home Systems for Personalized Mental Wellness; Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science: Official Journal of the Coalition for Technology in Behavioral Science, 2025; pp. 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Zuñiga, G.; Arce, D.; Gibaja, S.; Alvites, M.; Cano, C.; Bustamante, M.; Horna, I.; Paredes, R.; Cuellar, F. Qhali: A Humanoid Robot for Assisting in Mental Health Treatment. Sensors 2024, 24(4), 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazuz, K.; Yamazaki, R. Trauma-informed care approach in developing companion robots: a preliminary observational study. Frontiers in Robotics and AI 2025, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PR Newswire. X-Origin AI Introduces Yonbo: The Next-Gen AI Companion Robot Designed for Families. 2025. Available online: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/x-origin-ai-introduces-yonbo-the-next-gen-ai-companion-robot-designed-for-families-302469293.html.

- Kalam, K. T.; Rahman, J. M.; Islam, Md. R.; Dewan, S. M. R. ChatGPT and mental health: Friends or foes? In Health Science Reports; Portico, 2024; Volume 7, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, J. W.; Poliak, A.; Dredze, M.; Leas, E. C.; Zhu, Z.; Kelley, J. B.; Faix, D. J.; Goodman, A. M.; Longhurst, C. A.; Hogarth, M.; Smith, D. M. Comparing Physician and Artificial Intelligence Chatbot Responses to Patient Questions Posted to a Public Social Media Forum. JAMA Internal Medicine 2023, 183(6), 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; DiPaola, D.; Ali, S.; Sap, M.; Park, H. W.; Breazeal, C. Empathy Toward Artificial Intelligence Versus Human Experiences and the Role of Transparency in Mental Health and Social Support Chatbot Design: Comparative Study. JMIR Mental Health 2024, 11, e62679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refoua, E.; Elyoseph, Z.; Wacker, R.; Dziobek, I.; Tsafrir, I.; Meinlschmidt, G. The next frontier in mindreading? Assessing generative artificial intelligence (GAI)’s social-cognitive capabilities using dynamic audiovisual stimuli. Computers in Human Behavior Reports 2025, 19, 100702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elyoseph, Z.; Refoua, E.; Asraf, K.; Lvovsky, M.; Shimoni, Y.; Hadar-Shoval, D. Capacity of Generative AI to Interpret Human Emotions From Visual and Textual Data: Pilot Evaluation Study. JMIR Mental Health 2024, 11, e54369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roustan, D.; Bastardot, F. The Clinicians’ Guide to Large Language Models: A General Perspective With a Focus on Hallucinations. Interactive Journal of Medical Research 2025, 14, e59823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asman, O.; Torous, J.; Tal, A. Responsible Design, Integration, and Use of Generative AI in Mental Health. JMIR Mental Health 2025, 12, e70439–e70439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaber, F.; Shaik, M.; Allega, F.; Bilecz, A. J.; Busch, F.; Goon, K.; Franke, V.; Akalin, A. Evaluating large language model workflows in clinical decision support for triage and referral and diagnosis. Npj Digital Medicine 2025, 8(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laestadius, L.; Bishop, A.; Gonzalez, M.; Illenčík, D.; Campos-Castillo, C. Too human and not human enough: A grounded theory analysis of mental health harms from emotional dependence on the social chatbot Replika. New Media & Society 2022, 26(10), 5923–5941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, J.; Oğuz-Uğuralp, Z.; Kaan-Uğuralp, A. “Emotional Manipulation by AI Companions”. Available from. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Prunkl, C. Human Autonomy at Risk? An Analysis of the Challenges from AI. Minds and Machines 2024, 34(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansoor, M.; Hamide, A.; Tran, T. Conversational AI in Pediatric Mental Health: A Narrative Review. Children 2025, 12(3), 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoene, A.M.; Canca, C. For Argument’s Sake, Show Me How to Harm Myself!’: Jailbreaking LLMs in Suicide and Self-Harm Contexts. arXiv 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landymore, F. Psychologist Says AI Is Causing Never-Before-Seen Types of Mental Disorder. 2025. Available online: https://futurism.com/psychologist-ai-new-disorders.

- Morrin, H.; Nicholls, L.; Levin, M.; Yiend, J.; Iyengar, U.; DelGuidice, F.; Bhattacharyya, S.; MacCabe, J.; Tognin, S.; Twumasi, R.; Alderson-Day, B.; Pollak, T. Delusions by design? How everyday AIs might be fuelling psychosis (and what can be done about it). 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foster, C. Experts issue warning over ‘AI psychosis’ caused by chatbots. Here’s what you need to know. 2025. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-families/ai-psychosis-symptoms-warning-chatboat-b2814068.html.

- Prada, L. ChatGPT is giving people extreme spiritual delusions . 2025. Available online: https://www.vice.com/en/article/chatgpt-is-giving-people-extreme-spiritual-delusions.

- Tangermann, V. ChatGPT users are developing bizarre delusions . 2025. Available online: https://futurism.com/chatgpt-users-delusions.

- Klee, M. Should We Really Be Calling It ‘AI Psychosis’? Rolling Stone. 2025. Available online: https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-features/ai-psychosis-chatbot-delusions-1235416826/.

- Dupre, Harrison. “People Are Becoming Obsessed with ChatGPT and Spiraling Into Severe Delusions”. 2025. Available online: https://futurism.com/chatgpt-mental-health-crises.

- Hart, R. Chatbots Can Trigger a Mental Health Crisis. What to Know About ‘AI Psychosis’. 2025. Available online: https://au.news.yahoo.com/chatbots-trigger-mental-health-crisis-165041276.html.

- Rao, D. ChatGPT psychosis: AI chatbots are leading some to mental health crises . 2025. Available online: https://theweek.com/tech/ai-chatbots-psychosis-chatgpt-mental-health.

- Siow Ann, C. AI Psychosis- a real and present danger. The Straits Times. 2025. Available online: https://www.straitstimes.com/opinion/ai-psychosis-a-real-and-present-danger.

- Travers, M. 2 Terrifyingly Real Dangers Of ‘AI Psychosis’ — From A Psychologist. 2025. Available online: https://www.forbes.com/sites/traversmark/2025/08/27/2-terrifyingly-real-dangers-of-ai-psychosis---from-a-psychologist/.

- Zilber, A. ChatGPT allegedly fuelled former exec’s ‘delusions’ before murder-suicide. Available from: ChatGPT ‘coaches’ man to kill his mum | news.com.au — Australia’s leading news site for latest headlines. viewed on. 2025.

- Bryce, A. AI psychosis: Why are chatbots making people lose their grip on reality? 2025. Available online: https://www.msn.com/en-us/technology/artificial-intelligence/ai-psychosis-why-are-chatbots-making-people-lose-their-grip-on-reality/ar-AA1M2eDr?ocid=BingNewsSerp.

- Phiddian, E. AI Companions apps such as Replika need more effective safety controls, experts say. AI companion apps such as Replika need more effective safety controls, experts say - ABC News. viewed on. 2025.

- McLennan, A. AI chatbots accused of encouraging teen suicide as experts sound alarm. 2025. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-08-12/how-young-australians-being-impacted-by-ai/105630108.

- Yang, A.; Jarrett, L.; Gallagher, F. “The family of teenager who died by suicide alleges OpenAI’s ChatGPT is to blame”. 2025. Available online: https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/tech-news/family-teenager-died-suicide-alleges-openais-chatgpt-blame-rcna226147.

- ABC News. “OpenAI’s ChatGPT to implement parental controls after teen’s suicide”. 2025. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-09-03/chatgpt-to-implement-parental-controls-after-teen-suicide/105727518.

- Hartley, T.; Mockler, R. Hayley has been in an AI relationship for four years. It’s improved her life dramatically but are there also risks? 2025. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2025-08-20/ai-companions-romantic-relationships-ethical-concerns/105673058.

- Scott, E. It’s like a part of me’: How a ChatGPT update destroyed some AI friendships . 2025. Available online: https://www.sbs.com.au/news/the-feed/article/chatgpt-friendship-relationships-therapist/3cxisfo4o.

- OECD. Governing with Artificial Intelligence: The State of Play and Way Forward in Core Government Functions; OECD Publishing: Paris, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Ethics and governance of artificial intelligence for health: Guidance on large multi-modal models. Geneva, 2025. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240084759.

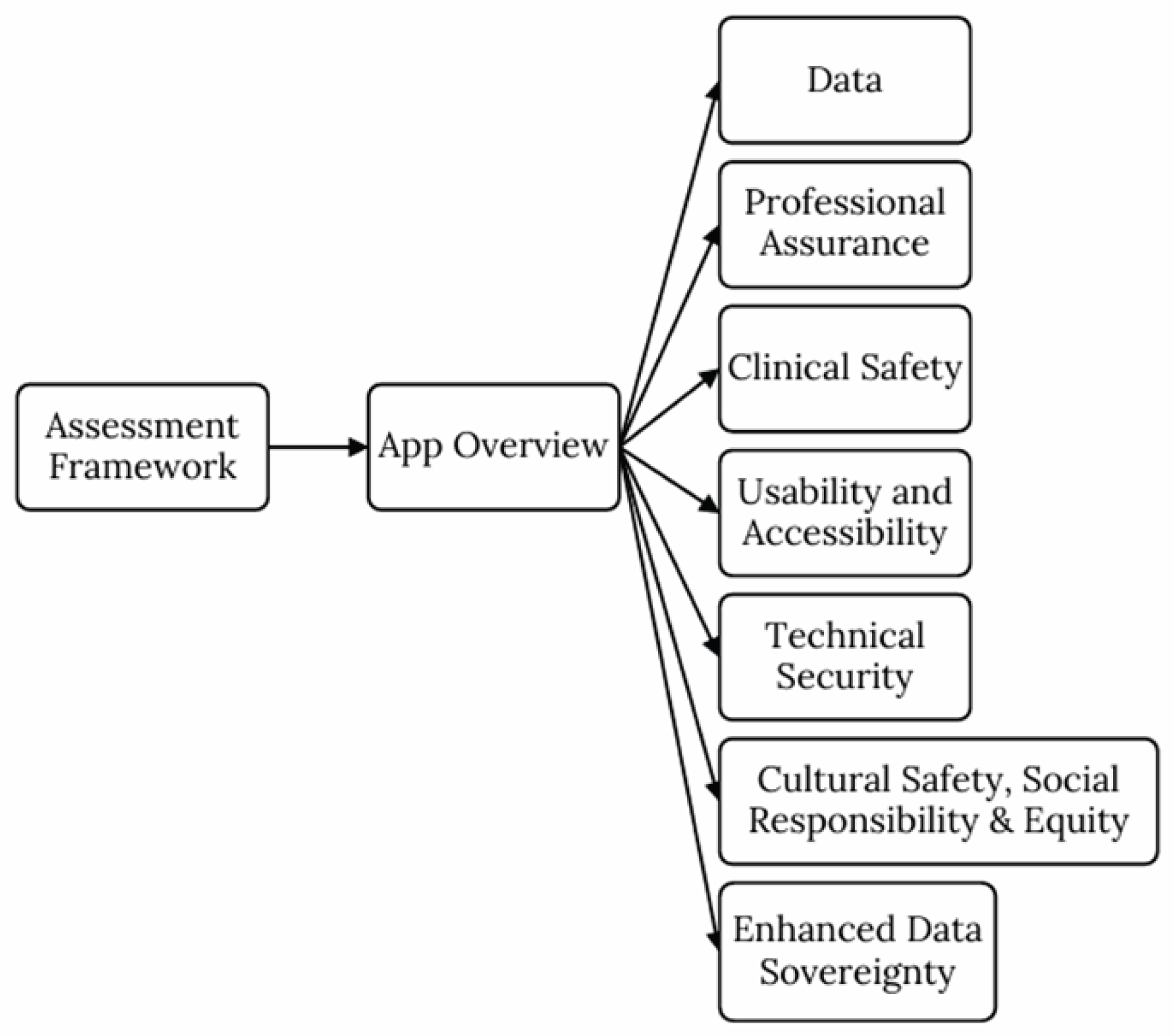

- Mental Health Commission of Canada. Assessment Framework for Mental Health Apps. 2023. Available online: https://mentalhealthcommission.ca/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/MHCC-Assessment-Framework-for-Mental-Health-Apps-EN-FINAL.pdf.

- Waddell, A.; Seguin, J. P.; Wu, L.; Stragalinos, P.; Wherton, J.; Watterson, J. L.; Prawira, C. O.; Olivier, P.; Manning, V.; Lubman, D.; Grigg, J. Leveraging Implementation Science in Human-Centred Design for Digital Health. In Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2024; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haber, Y.; Hadar Shoval, D.; Levkovich, I.; Yinon, D.; Gigi, K.; Pen, O.; Angert, T.; Elyoseph, Z. The externalization of internal experiences in psychotherapy through generative artificial intelligence: a theoretical, clinical, and ethical analysis. Frontiers in Digital Health 2025, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciriello, R. F.; Chen, A. Y.; Rubinsztein, Z. A. Compassionate AI Design, Governance, and Use. IEEE Transactions on Technology and Society 2025, 6(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelhalim, E.; Anazodo, K. S.; Gali, N.; Robson, K. A framework of diversity, equity, and inclusion safeguards for chatbots. Business Horizons 2024, 67(5), 487–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Bhanushali, T.; Huang, Z.; Yang, J.; Badami, S.; Hightow-Weidman, L. Evaluating Generative AI in Mental Health: Systematic Review of Capabilities and Limitations. JMIR Mental Health 2025, 12, e70014–e70014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howcroft, A.; Blake, H. Empathy by Design: Reframing the Empathy Gap Between AI and Humans in Mental Health Chatbots. Information 2025, 16(12), 1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).