The discussion section first examines the present findings considering current empirical evidence on gratitude and human flourishing, highlighting points of convergence and divergence with previous research. In addition, it includes a subsection on Clinical Relevance and Future Research Directions, which addresses the practical implications of these findings for assessment and intervention, and identifies key gaps and priorities for future empirical work and clinical practice.

4.1. Gratitude and Human Flourishing in Adults: Toward a Deeper Understanding

Seligman [

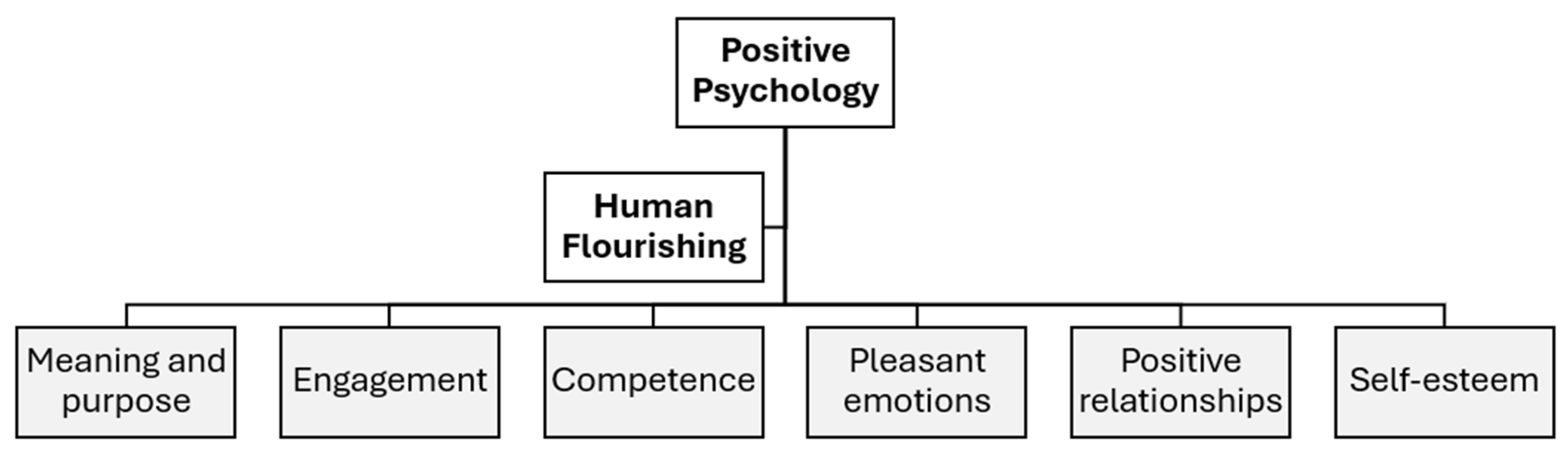

14] argues that flourishing is one of the most central and promising constructs in Positive Psychology, as it offers crucial insights for enhancing quality of life for all individuals. The term is commonly used to describe a person’s overall state of well-being. In this study, flourishing was selected as one of the focal constructs because it reflects the capacity of adults to cope with daily challenges and adversity.

The notion of human flourishing is clearly different from subjective well-being, which primarily assesses happiness, and from psychological well-being, which focuses mainly on self-processes. Instead, flourishing integrates elements of both subjective and psychological well-being into a more comprehensive framework [

14]

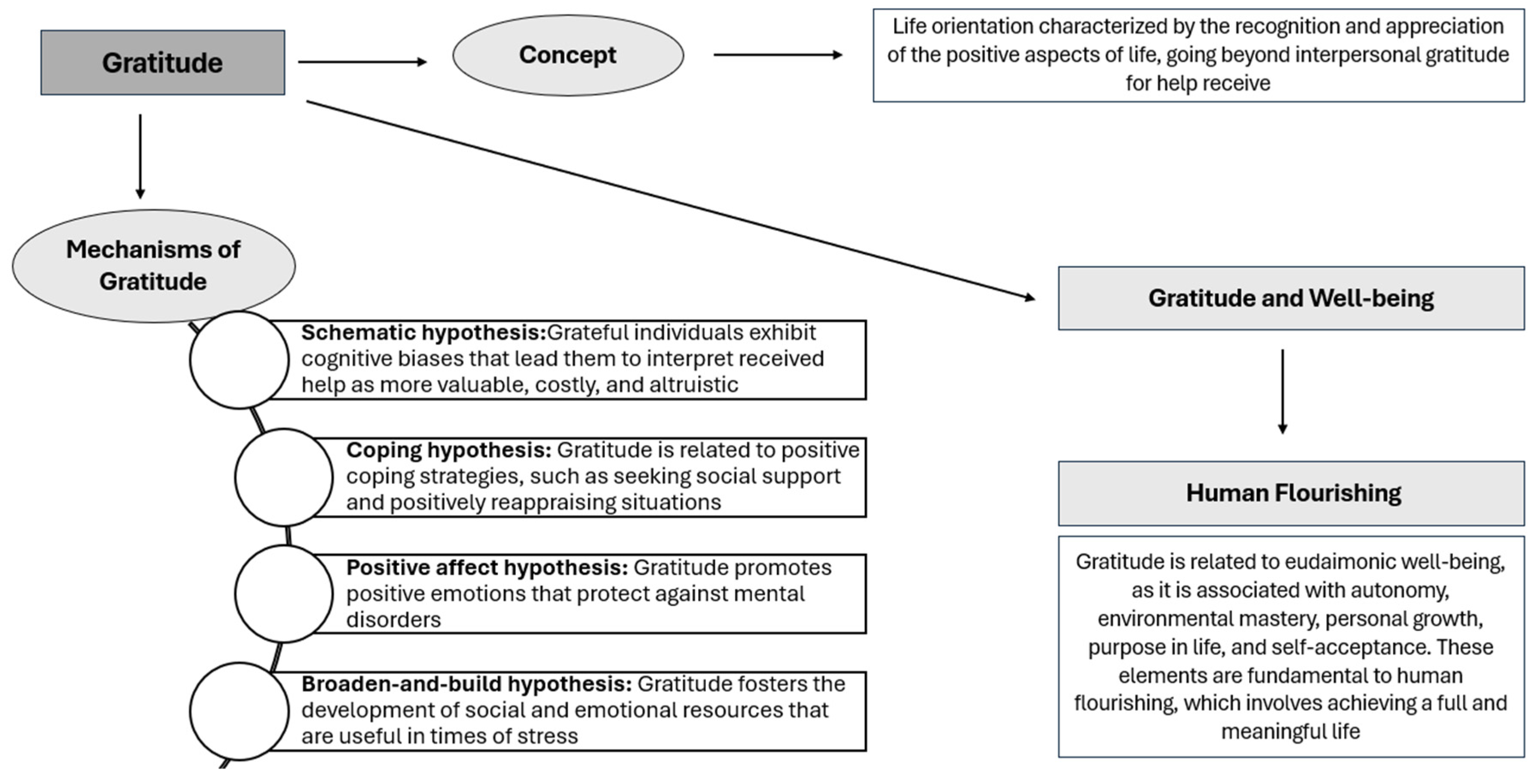

Human flourishing -as a multidimensional state of overall well-being- encompasses happiness, physical health, a sense of meaning in life, positive interpersonal relationships, financial stability, and character development. Within this framework, gratitude is identified as a central factor in fostering flourishing, as it is associated with a wide range of psychological, social, and physical benefits [

30].

In terms of mental well-being, gratitude is linked to higher life satisfaction, more frequent positive emotions, and lower levels of psychological distress, including reduced depressive symptoms and diminished suicidal ideation. With regard to physical health, gratitude has been associated with better cardiovascular functioning, lower rates of obesity, fewer sleep disturbances, and an enhanced subjective perception of general health. At the social level, gratitude appears to strengthen interpersonal bonds by promoting social support and encouraging participation in community activities, thereby contributing to collective well-being [

30].

According to the reviewed studies, gratitude helps adults regulate their emotions, strengthen their relationships, derive meaning from their experiences, and attain personal accomplishments, all of which are key aspects of the PERMA model of flourishing [

10,

12,

14].

In the same line, gratitude plays a central role in psychological well-being, as it is closely linked to increased positive emotions, enhanced interpersonal relationships, and a greater capacity to derive meaning from life. According to the current research, gratitude supports individuals in coping with adversity by shifting their perspective toward a more positive outlook, enabling them to value both their experiences and the people who are part of their lives. Gratitude also contributes to well-being by strengthening social bonds, fostering positive emotions, and helping individuals to find meaning in the challenges they face. It may also enhance engagement in daily activities and promote the attainment of personal goals [

10,

12,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. Individuals with higher levels of gratitude tend to be more proactive and, consequently, are much more likely to engage in more positive and effective coping strategies when facing stressful life situations. In turn, they are also more likely to develop and mobilize their social support network and to activate other psychological strengths, such as optimism and resilience, all of which contributes to fostering better mental health and preventing mental disorders and emotional disturbances.

The studies reviewed underscore the central role of gratitude in the process of human flourishing, particularly among vulnerable populations and individuals undergoing life transitions or periods of crisis. This finding is especially relevant, as it may point to a set of protective factors that could be beneficial not only during diagnosis and treatment, but also as part of mental health prevention strategies. Such problems often remain under-recognized due to the stigma associated with them and the difficulties involved in accessing appropriate care resources.

Older adults are included in this group because of the challenges associated with this stage of life, together with the potential comorbidities and health problems that frequently emerge in later adulthood. Emerging evidence also points to gratitude as a protective factor in reducing stress, particularly in later life, and highlights the beneficial impact of gratitude-based interventions on perceived stress and flourishing in older adults. Programs that systematically cultivate gratitude—such as gratitude journaling or guided reflection on positive life events—have been associated with lower levels of psychological strain and higher reports of meaning, positive affect, and overall well-being in this population [

9]. These findings are consistent with the so-called paradox of ageing, a term used to describe the observation that life satisfaction tends to increase as people grow older [

36]. The idea that, despite the physical, cognitive, and social losses typically experienced, later life is associated with higher levels of well-being has become a central theme in the ageing literature [

36]. We hypothesize that gratitude and the level of flourishing attained function as mediating or antecedent factors in this phenomenon, a possibility that warrants further empirical investigation.

In contemporary societies, which are dominated by youth-oriented values such as strength, speed, innovation, and efficiency, later adulthood has often been associated with economic poverty, inactivity in the labour market, sociocultural marginalization, and ill health. This representation of ageing has given rise to the so-called “decline model”, which focuses on deficits and has contributed to the proliferation of stereotypes about old age. There is therefore a clear need to reconsider the prevailing social representations of ageing and older adults and to actively counteract ageism. By contrast, the “personal growth model” – grounded in a life-span developmental perspective – underscores the potential advantages of later life, such as increased free time, reduced responsibilities, and a greater capacity to focus on what is truly important [

36]. Within this framework, gratitude aligns closely with a model centred on personal growth and on the promotion of active and healthy ageing.

In the case of emerging adults with divorced parents, gratitude assists them in coping with the stress and difficulties associated with parental separation, allowing them to strengthen family relationships and find meaning in their lived experiences. Thus, gratitude constitutes a key factor in optimizing flourishing within this group [

10]. Gratitude appears to be a powerful resource for fostering flourishing, as it assists them in managing stress and in developing healthier and more meaningful relationships [

10]. It is important to recognize that divorce often constitutes a stressful life event for sons and daughters. Although in many cases it does not lead to a full-blown crisis or become consolidated as a traumatic event, in many others it does. When the inherently stressful nature of divorce is combined with the fact that the transition to adulthood is marked by a series of changes and events that also generate stress (e.g., beginning university, entering the labour market, psychophysiological changes, shifts in social roles and expectations, changes in responsibilities, identity transitions, and the exploration of new relationships and social networks), it becomes particularly relevant to examine how gratitude may contribute to well-being and help ensure that the transition to adulthood occurs under the most favourable conditions. In this way, gratitude might foster an adequate process of flourishing and the strengthening of coping resources that will be crucial across subsequent life stages.

According to the study of Tessy [

10], several factors contribute to well-being or flourishing in emerging adults. The authors reported the significant role of both gratitude and forgiveness. Gratitude promotes positive emotions, strengthens interpersonal relationships, facilitates the construction of meaning from experiences, and supports greater engagement and personal achievement. Forgiveness, in turn, involves the capacity to let go of negative emotions such as anger, and to replace them with more positive states such as empathy and compassion. In this way, forgiveness contributes to improved relationships, helps individuals to derive meaning from difficult experiences, and supports emotional well-being. At the emotional level, forgiveness may facilitate the experience of gratitude by releasing negative emotions such as resentment toward those who have caused harm, individuals may become more receptive to acknowledging and appreciating the positive aspects of their lives and relationships. In a complementary way, forgiveness and gratitude jointly promote well-being—while forgiveness reduces negative affect and contributes to the repair of damaged relationships, gratitude cultivates positive emotions and reinforces social bonds [

10]. Both processes also play a significant role in flourishing, as they are linked to key components of the PERMA model, including positive emotions, relationships, and meaning. Taken together, they may be particularly effective in enhancing the well-being of emerging adults. Thus, forgiveness and gratitude are not only related but mutually reinforcing in their capacity to improve emotional well-being and interpersonal functioning [

10].

From a clinical standpoint, the constructs of gratitude and flourishing are closely aligned with third-wave behavioral therapies, particularly Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) [

37]. ACT explicitly aims to promote a rich, full, and purposeful life, rather than merely reducing symptoms, by fostering psychological flexibility, values-based action, and acceptance of difficult internal experiences. Within this framework, gratitude can be understood as a practice that orients attention toward valued aspects of one’s life and context, even in the presence of pain or illness, while flourishing reflects the broader outcome of living in accordance with personally worthwhile values. Integrating gratitude-focused exercises into ACT-based interventions might therefore strengthen individuals’ capacity to engage with their lives in a more open, appreciative, and committed way, supporting well-being that extends beyond symptom control or the absence of disease.

In the same line, in the context of chronic osteoarthritis, the study framed within Aristotelian virtue theory underscores gratitude and flourishing as two central virtue-based resources [

31]. Gratitude appears to function as a facilitating factor for quality of life and for the development of a salient life despite pain and its accompanying symptoms. This is one of the principal therapeutic objectives in the treatment of patients with chronic pain, as these symptoms are often disabling and individuals’ autonomy, social networks, and life projects tend to be adversely affected by both the pain and its chronic nature. Evaluating and intervening in gratitude and flourishing in the context of chronic pain is particularly important because these constructs shift the clinical focus from mere symptom control to the possibility of living a valuable life alongside pain [39,40]. In this sense, working explicitly with gratitude and flourishing does not imply denying the reality of pain, but rather enlarging the therapeutic horizon to include growth, purpose, and connection as legitimate and attainable outcomes of chronic pain treatment. In the context of flourishing, gratitude emerged as a capacity that can catalyze personal growth and healing not only at the individual level but also within the family domain. Close relationships, particularly familial ones, were frequently mentioned as settings in which virtues such as gratitude are experienced and embodied, thereby contributing to well-being and flourishing in the midst of adversity [

31].

In addition, the longitudinal findings of Phillips et al. [

32] with adults with disabilities reinforce the notion that gratitude operates as a prospective predictor of flourishing and not merely as a concurrent correlate of well-being. Higher gratitude at baseline was associated with greater flourishing nearly two years later, suggesting that grateful dispositions may set in motion processes that support long-term psychological adjustment. Importantly, adaptation to disability partially mediated this association, accounting for a substantial proportion of the total effect. This pattern indicates that gratitude may contribute to flourishing, at least in part, by facilitating more effective adaptation to the challenges imposed by disability. In other words, individuals who cultivate gratitude appear better able to adjust to their functional limitations, and this enhanced adaptation is reflected in higher levels of flourishing over time. Such results align with strengths-based perspectives in rehabilitation psychology and highlight gratitude and flourishing as a promising target for interventions aimed at promoting both adaptive functioning and a fuller, more substantive life in the context of disability [

32,41,42]. In line with this perspective, our findings support the idea of reimagining rehabilitation and health care beyond a deficit-correction model focused solely on restoring bodily “normality.” Emphasizing gratitude and flourishing invites clinicians to consider how people can lead rich, personally significant, and dignified lives even when pain, illness, or disability persist. This shift aligns rehabilitation goals with broader notions of human development and well-being, rather than limiting success to symptom reduction or functional recovery alone [41].

Qualitative work with forcibly displaced migrants in South Africa further also underscores gratitude as a central psychosocial resource for coping and flourishing [

33]. From an emic standpoint, gratitude was portrayed as helping individuals face traumatic experiences, providing a sense of relief and a renewed outlook on their circumstances; migrants reported feeling thankful for being alive, for having escaped oppressive contexts, and for the community ties that facilitated change in their lives. Gratitude was also closely linked to other inner strengths, such as hope and optimism, highlighting the interconnected nature of these positive dispositions [

7,

14,

33]. In relation to flourishing, gratitude emerged as a capacity that can foster personal growth and healing at both individual and family levels, with close—especially familial—relationships described as key contexts in which gratitude is experienced, embodied, and translated into well-being and flourishing despite ongoing adversity [

33]. Participants in the study reported that gratitude allowed them to value their survival, learn from difficult experiences, and develop new ways of understanding their circumstances. This disposition not only supported them in coping with hardship but also functioned as a catalyst for personal growth and resilience. Moreover, gratitude emerged as a psychosocial resource that can positively shape family and community relationships, contributing to an “upward spiral” of collective well-being [

33].

Gratitude also emerged as one of the core components of personal flourishing in the study of Braghetta et al [

34] which explores the effects of the flourishing intervention among individuals with depressive symptoms. Gratitude appears to contribute to flourishing through several interrelated pathways. One possible explanation points out that gratitude is closely associated with the experience of positive emotions (i.e., satisfaction and happiness) which play a relevant role in well-being and flourishing. Participants in the intervention reported feeling more grateful and placing greater value on positive aspects of their lives, which likely supported their overall sense of well-being. Moreover, gratitude is associated with strengthened social relationships, as it tends to foster empathy, connectedness, and appreciation of others. These relational benefits are highly relevant to flourishing, which encompasses close social ties and perceived social support.

Moreover, gratitude may exert a protective effect on mental health. By promoting a more positive focus and reframing experiences, gratitude can contribute to reductions in depressive symptoms and improvements in quality of life, aligning with the broader aims of the flourishing intervention to enhance psychological and emotional well-being. Participants’ qualitative reports suggested a significant shift in perspective, characterized by a more positive outlook on life and increased appreciation of their experiences. Such attitudinal change can be considered a key element of personal flourishing [

4,

34]. Therefore, gratitude appears to function as a facilitating factor for flourishing by enhancing positive affect, strengthening social relationships, and supporting psychological and emotional well-being [

4,

34].

Furthermore, individuals who report higher levels of gratitude tend to engage in healthier lifestyle behaviors, such as lower consumption of substances and alcohol, which may indirectly support both physical and psychological health. Finally, gratitude is also related to a higher frequency of participation in religious services, which can reinforce a sense of purpose, belonging, and spiritual connection, and thus further contribute to the overall experience of human flourishing [

30].

Drawing on moral affect theory, gratitude can be understood as a moral emotion that orients individuals toward prosocial behavior and relationship-enhancing responses. From this perspective, expressions of gratitude do more than simply reflect momentary positive feelings; they serve to acknowledge benefits received from others and to reinforce perceptions of others as benevolent and trustworthy [

38]. In this way, gratitude promotes the formation, maintenance, and strengthening of social bonds. These closer relationships, in turn, expand individuals’ interpersonal resources—such as emotional support, practical assistance, and informational guidance—which are critical for effective coping. Thus, gratitude not only fosters a sense of connection and reciprocity but also indirectly enhances coping capacity by increasing access to social and psychological resources that can be mobilized in the face of stress or adversity.

In sum, gratitude appears to operate as a facilitator of flourishing by promoting acceptance, meaning-making, and interpersonal connectedness, even in contexts marked by suffering and adversity [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34].

4.2. Clinical Relevance and Future Research Direction

The present findings suggest several relevant implications for clinical practice and mental health promotion, particularly among those with lower levels of gratitude (e.g., younger individuals, men, the unemployed and people with lower levels of religious participation). First, gratitude-based interventions could be integrated as low-cost, scalable tools within primary care, community health programs, and psychological services. Practices such as writing gratitude letters, keeping gratitude journals, and/or expressing appreciation to significant others might act as effective strategies to enhance emotional well-being, complementing existing scientific evidence-based treatments [

30].

In addition, given that human flourishing is influenced by cultural, social, and demographic variables [

30], clinicians should consider these contextual factors when designing and implementing gratitude-focused interventions. For example, the way gratitude is expressed and experienced may differ across cultures, age groups, and socioeconomic contexts. Adapting the language, format, and delivery of gratitude and flourishment exercises to the values and norms of specific populations may increase their acceptability, engagement, and effectiveness.

In the same line, cross-cultural research indicates that the determinants of well-being are not universal, but are shaped by the cultural context in which individuals are embedded. For instance, in more individualistic societies, personal autonomy, self-expression, and the pursuit of individual goals tend to emerge as particularly strong predictors of well-being. By contrast, in more collectivistic cultures, the quality of interpersonal relationships, a sense of belonging, and the fulfilment of social roles carry greater weight in explaining subjective well-being and flourishing [

3]. These differences suggest that what it means to “live well” is partly defined by culturally shared values and norms, and that psychological constructs such as flourishing and gratitude may be experienced, expressed, and prioritized in distinct ways across cultural settings.

These considerations underscore the relevance of systematically accounting for cultural factors when designing and interpreting research on well-being and gratitude. Measures developed in one cultural context may not fully capture relevant aspects of flourishing in another, and the relative contribution of different dimensions (e.g., autonomy, social network, material stability, spiritual life, etc.) might vary across populations. Similarly, interventions aimed at enhancing gratitude and well-being are unlikely to be equally effective if they do not align with culturally salient values and relational expectations.

Therefore, these findings point to the need for culturally sensitive research and intervention programs. Future studies should explicitly examine how cultural norms and value systems shape the links between gratitude and flourishing, and adapt intervention components accordingly. Incorporating cultural perspectives can enhance the ecological validity, acceptability, and effectiveness of gratitude-based interventions, ensuring that they are responsive to the lived realities of diverse communities.

Furthermore, gratitude-based practices may be particularly useful in prevention and health promotion settings. Incorporating brief gratitude exercises into school curricula, workplace wellness programs, and community-based initiatives could help foster resilience, strengthen social bonds, and reduce stress levels. In clinical populations, these interventions might also contribute to improving mood, enhancing perceived social support, and promoting adherence to treatment recommendations.

Moreover, from a clinical perspective, the evidence on gratitude, forgiveness, and flourishing, particularly among those groups that are most vulnerable or currently experiencing periods of crisis and/or transition (i.e., emerging adults, older adults, chronic pain patients, people with disabilities, people with depression, forced migrants, etc.) highlights several important implications for assessment and intervention.

For instance, for clinical practice with older adults, incorporating gratitude and flourishing into assessment and intervention offers a valuable complement to traditional symptom-focused approaches. Integrating these elements into psychosocial and rehabilitative programs may therefore promote more holistic well-being in later life, supporting older adults not only to cope with loss and decline, but also to maintain a sense of growth, dignity, and fulfillment.

In the case of emerging adults with divorced parents, mental health professionals working with this population may benefit from systematically evaluating levels of gratitude and forgiveness as potential protective factors that influence the impact of family stress and relational disruption [

10]. Integrating gratitude- and forgiveness-based exercises into therapeutic protocols might support emotional regulation, reduce negative affect such as anger and fear, and strengthen key dimensions of flourishing (i.e., positive emotions, meaningful relationships, and sense of purpose). Moreover, fostering these dispositions may enhance engagement in daily activities and promote adaptive goal pursuit, thereby contributing to more resilient trajectories of development during the transition to adulthood. In this sense, gratitude and forgiveness can be conceptualized not only as outcomes of psychological adjustment but also as clinically relevant mechanisms that can be intentionally cultivated to optimize well-being in emerging adults exposed to the stressors associated with parental divorce.

In the field of disability, integrating the constructs of gratitude and flourishing into assessment and intervention may offer valuable avenues for enhancing mental health and quality of life. Fostering gratitude can help individuals orient attention toward purposeful aspects of their lives and social environments, even in the presence of functional limitations, while a focus on flourishing emphasizes agency, personal growth, and valued participation rather than deficit and impairment. Clinical interventions that explicitly incorporate gratitude practices and explore pathways to flourishing (for example, through values clarification, strengths-based work, and support for social connection) may therefore contribute to greater psychological adjustment, resilience, and a more positive identity.

Similarly, in the context of chronic pain, incorporating gratitude and flourishing into clinical practice can complement traditional approaches and broaden therapeutic goals beyond pain reduction. Encouraging patients to cultivate gratitude—for supportive relationships, coping resources, or relevant activities they can still engage in—may facilitate more adaptive pain acceptance and reduce the emotional burden associated with persistent symptoms. At the same time, a flourishing-oriented perspective invites clinicians and patients to collaboratively identify and pursue valued life domains, promoting a richer and more worthwhile life alongside pain. These strategies have the potential to promote psychological flexibility, improve mood and functioning, and foster a sense of growth and coherence in the face of long-term pain.

In addition, intervening with forced migrants from the perspective of positive psychology, and specifically through the promotion of gratitude and flourishing, is particularly relevant given their heightened vulnerability to chronic stress and social marginalization [

33]. Traditional interventions have often focused primarily on symptom reduction and trauma processing; while necessary, these approaches may be insufficient to foster long-term adaptation and well-being. Integrating strengths-based strategies that cultivate gratitude can contribute to rebuilding a sense of identity, meaning, and hope, while reinforcing personal and collective resources. Such interventions have the potential not only to alleviate negative emotional states, but also to enhance resilience, support healthier family and community dynamics, and promote more sustainable processes of social integration and flourishing. In this sense, working from a framework that emphasizes flourishing responds to an ethical and clinical imperative to move beyond mere survival and to support these individuals in leading lives they experience as dignified, meaningful, and fulfilling.

Regarding, future lines of research, the assessment of flourishing is highly relevant for informing public policy initiatives aimed at promoting population well-being, but this requires systematic evaluation procedures and psychometrically robust instruments to generate actionable evidence [

12]. The absence of consensus regarding the theoretical, conceptual, and operational definition of flourishing constrains the interpretability and cross-study comparability of epidemiological data, highlighting the need for greater international collaboration to move towards more standardized measurement frameworks. Moreover, decisions about thresholds for classifying individuals as flourishing are particularly consequential, as they critically shape reported prevalence rates and the conclusions drawn from them. Although the models differ in emphasis and structure, they show a moderate to high degree of convergence (e.g., Keyes and Seligman approaches), with some approaches aligning more closely than others [

12]. Therefore, studies should also employ prototype analyses to examine how lay perceptions of flourishing maps onto academic definitions, which may, in turn, contribute to refining existing measures. In sum, the study underscores the need to standardize flourishing assessments in order to enhance their usefulness for research and policy development [

12].

Future research should further develop the study of gratitude and flourishing, moving beyond predominantly cross-sectional designs toward longitudinal approaches that can clarify the mechanisms underlying their effects on mental health. Such designs would allow for a better understanding of temporal and causal pathways, as well as the dynamic interplay between these constructs and other psychological resources. In addition, it is essential to incorporate a gender-sensitive and intersectional perspective, examining how social positions and overlapping forms of vulnerability shape experiences of gratitude and opportunities for flourishing. Finally, more studies are needed with diverse populations—across different cultural, socioeconomic, and migratory contexts—to assess the generalizability of current findings and to identify context-specific factors that may enhance or hinder the benefits of gratitude for mental health and well-being.