Submitted:

10 December 2025

Posted:

11 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

| Method | Materials | Conditions treament | Efficiency | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrolysis + Fenton | Fe/C + H2O2 | Mass ratio Fe:C = 1:1; pH = 5; Processing time 300 minutes; H2O2 | COD removal 90.9%; color 84.4%; humic acids 72.8% | [7] |

| Electrolysis + Fenton | Fe/C + H2O2 | Mass ratio Fe:C = 3:1, mass of material Fe/C 55.72 g/L; pH = 3.12; H2O2 concentration 12.32 mL/L | COD removal 74.6%; BOD5/COD is 0.5 | [26] |

| Electrolysis + Fenton | Fe/C + H2O2 | Surface area ratio C:Fe = 717143.8; pH = 3.8; H2O2 concentration 1687.6 mg/L | COD removal 86.9% | [27] |

| Electrolysis + Fenton | Fe/C + H2O2 | Mass of Fe/C 104.52 g/L; pH = 3.2; H2O2 concentration is 3.57 g/L | COD removal 90.27%; humic acids 93.79%. | [28] |

| Electrolysis + Fenton | Fe/C + H2O2 | Fe/C mass 52 g/L; Fe:C mass ratio = 3:1; H2O2 concentration 12 mL/L; Processing time 1 h | COD removal 75%; BOD5/COD increased from 0.075 to 0.25. | [29] |

| Electrolysis + Fenton | Fe/C + H2O2 | Fe/C mass is 30~40 g/L; pH = 4; Processing time 1.5 h | COD removal 67.5%; color 92.41%; removal of Ni2+, Cr6+, Pb2+ ions is 96%, 97%, 96%. | [30] |

| Electrolysis + Fenton | Fe/C + H2O2 | Mass ratio Fe:C = 1:1; pH = 5; H2O2 concentration 100 mg/L | COD removal 86.1%; color 95.3%; humic acids 81.8%; BOD5/COD increased from 0.07 to 0.21 | [31] |

| Electrolysis + Fenton | Fe/C + H2O2 | Fe/GAC mass is 10 g/L pH = 3; ratio COD/H2O2 = 1/2 | COD removal 82.1%; BOD5/COD increased from 0.07 to 0.39 | [32] |

| Electrolysis + Fenton | Cast iron + H2O2 |

Fe0: 75 g/L, pH: 3.0. H2O2: 195.6 |

COD removal after internal microelectrolysis 38.2%, after internal microelectrolysis/H2O2 65.1% | [33] |

| Electrolysis + Fenton | Fe/C + H2O2 | pH of 5, Fe/C of 1:1, gas flow rate of 80 Lh-1, and H2O2 of 100mgL−1. | Removal efficiencies of COD (86.1%), color (95.3%), and humic acids (81.8%) | [34] |

| Electrolysis + Fenton | Fe/C + H2O2 | Fe/GAC: 3.0 pH 4, H2O2: 0.75 mM Air flow rate: 200 L/h |

Removal efficiencies COD: 79.2%, colour: 90.8%, BOD5/COD in the final effluent increased from 0.03 to 0.31 | [35] |

| Micro-electrolysis | Fe/C | pH 2.0; GAC 10 g/L; Fe0/GAC: 2/1; Time 90 min |

Removal: COD 85%, Increase in ratio: BOD5/COD 0.31 | [36] |

| Micro-electrolysis | Fe/AC | pH 3, Fe/AC: 12/4 g/L Time: 20 min |

Removal: COD 46% Total nitrogen: 54% |

[37] |

| Electrolysis + Fenton | Fe/C + H2O2 | Dose of H2O2 (27.5%) 25 L four times diluted | Removal: COD 85% Metal content >60% |

[38] |

| Micro-electrolysis O3/OH− /H2O2 |

Fe/GAC | Fe/GAC 20/80 g/L pH 3, |

Removal: COD 76.7% Total COD removal 95.4% at internal microelectrolysis O3/OH-/H2O2 | [39] |

|

Fe0/H2O2 process |

Fe0/H2O2 | pH 3, time: 60 min, COD/H2O2 ratio of 1:4 |

75% TOC removal, BOD5/COD ratio from 0.13 to 0.43 | [40] |

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Fabrication of Fe/Cu Material

2.2. Collection of Landfill Leachate

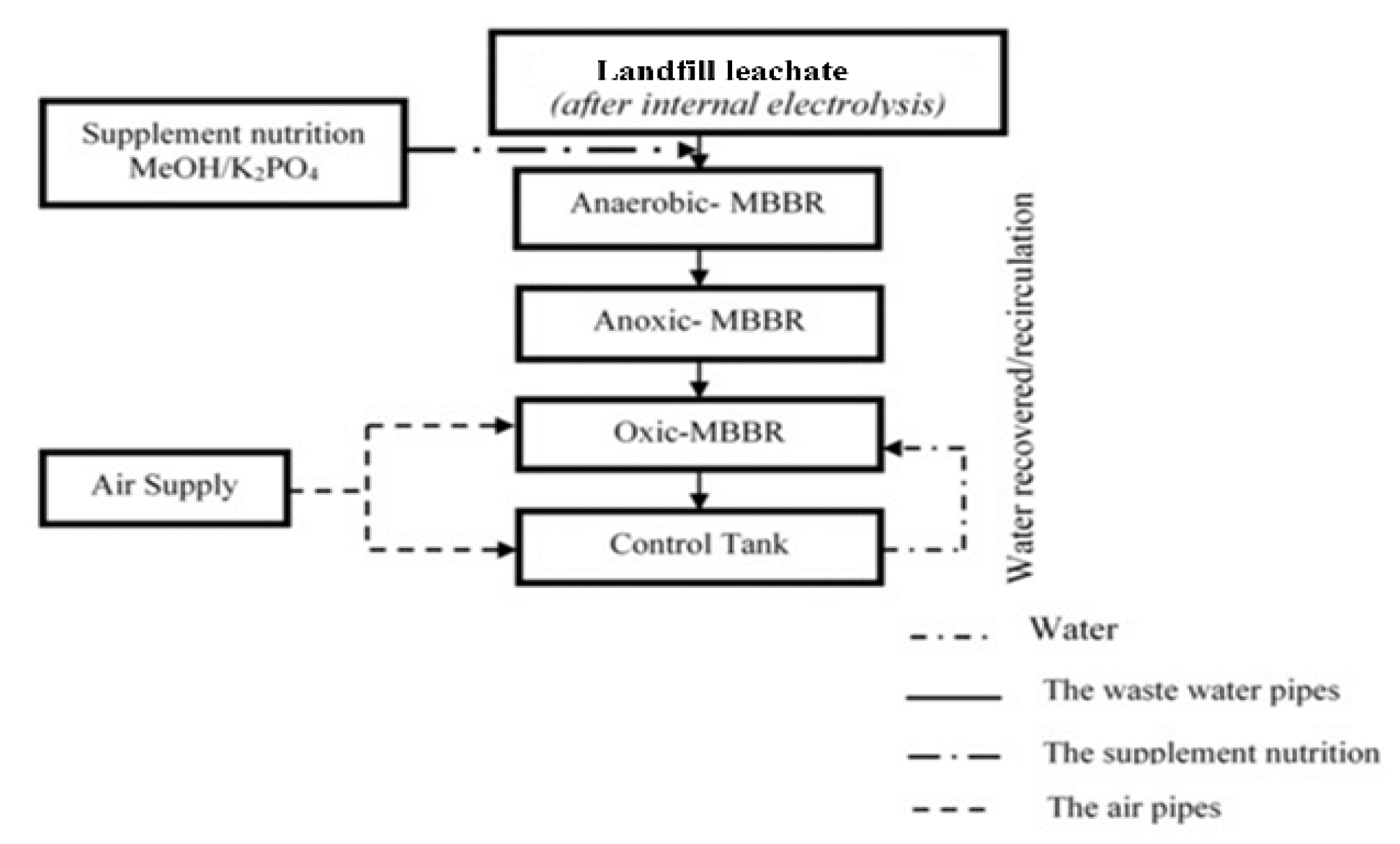

2.3. Establishment of the A₂O–MBBR System

2.3.1. Cultivation of Aerobic Activated Sludge

2.3.2. Cultivation of Anoxic Activated Sludge

2.3.3. Cultivation of Oxic Activated Sludge

2.3.4. Activated Sludge Culture

| Reaction Tank | COD (mg/L) | MLSS (mg/L ) | pH | DO (mg/L) | Retention Time (h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anaerobic | 1090 | 3043 | 7-8 | - | 14 |

| Anoxic tank | 2085 | 1-2 | 6 | ||

| Aerobic | 1123 | 5-8 | 4 |

2.4. Methods and Instruments

3. Results

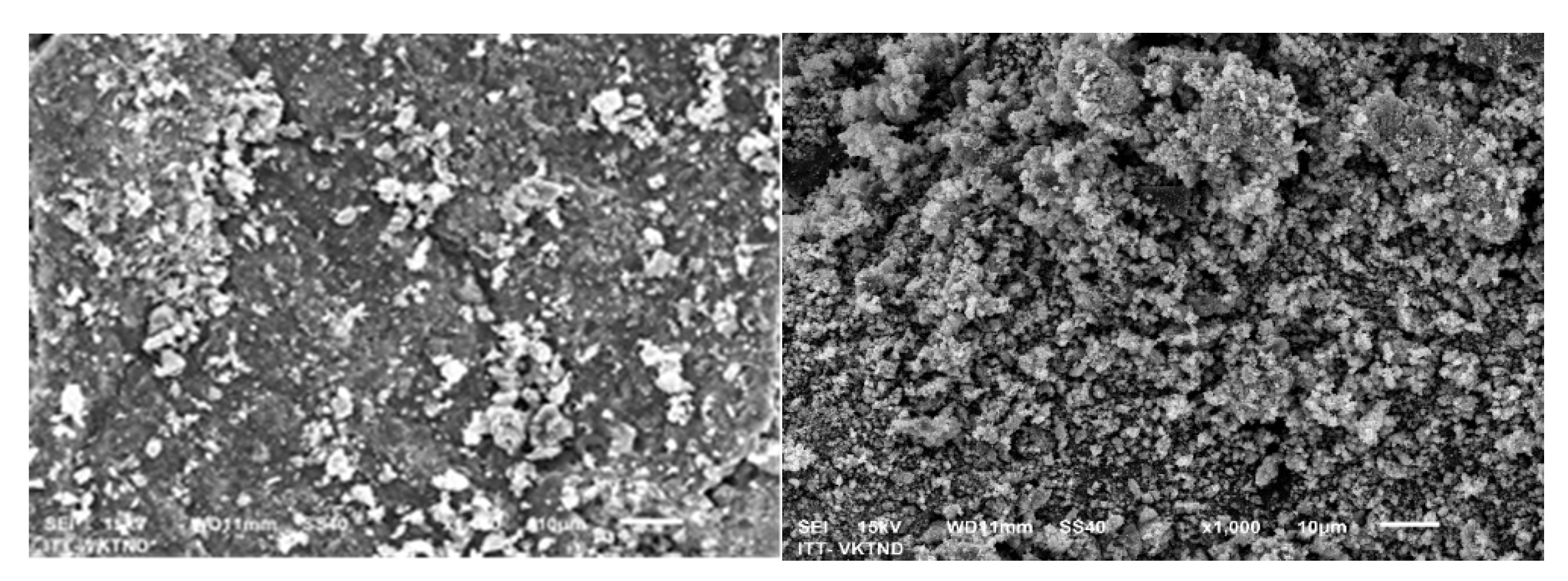

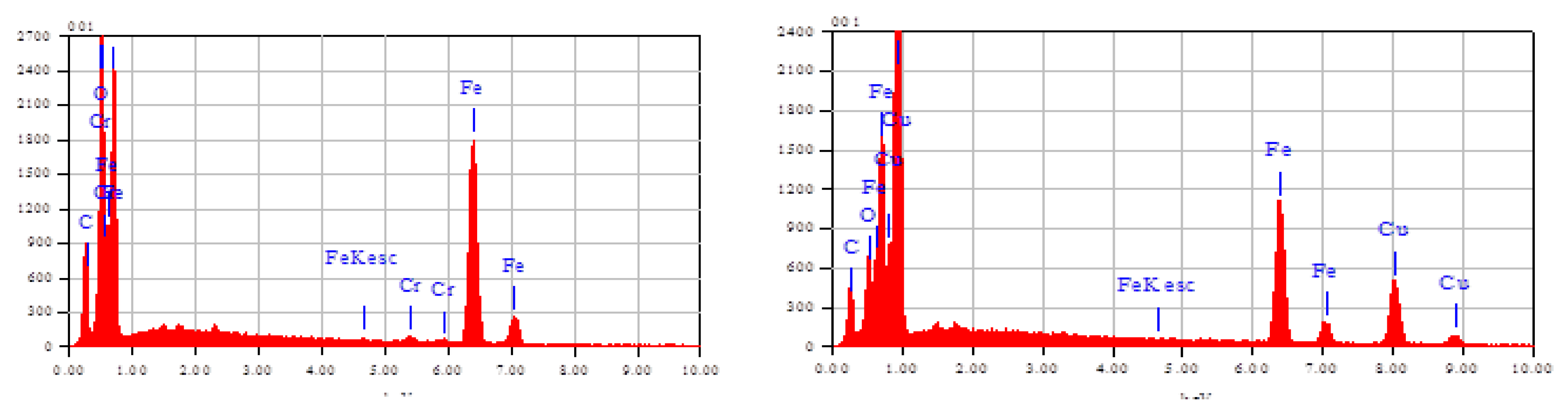

3.1. Surface Characteristics and Physical Properties of Fe/Cu Materials

3.1.1. SEM–EDS Analysis of Fe/Cu

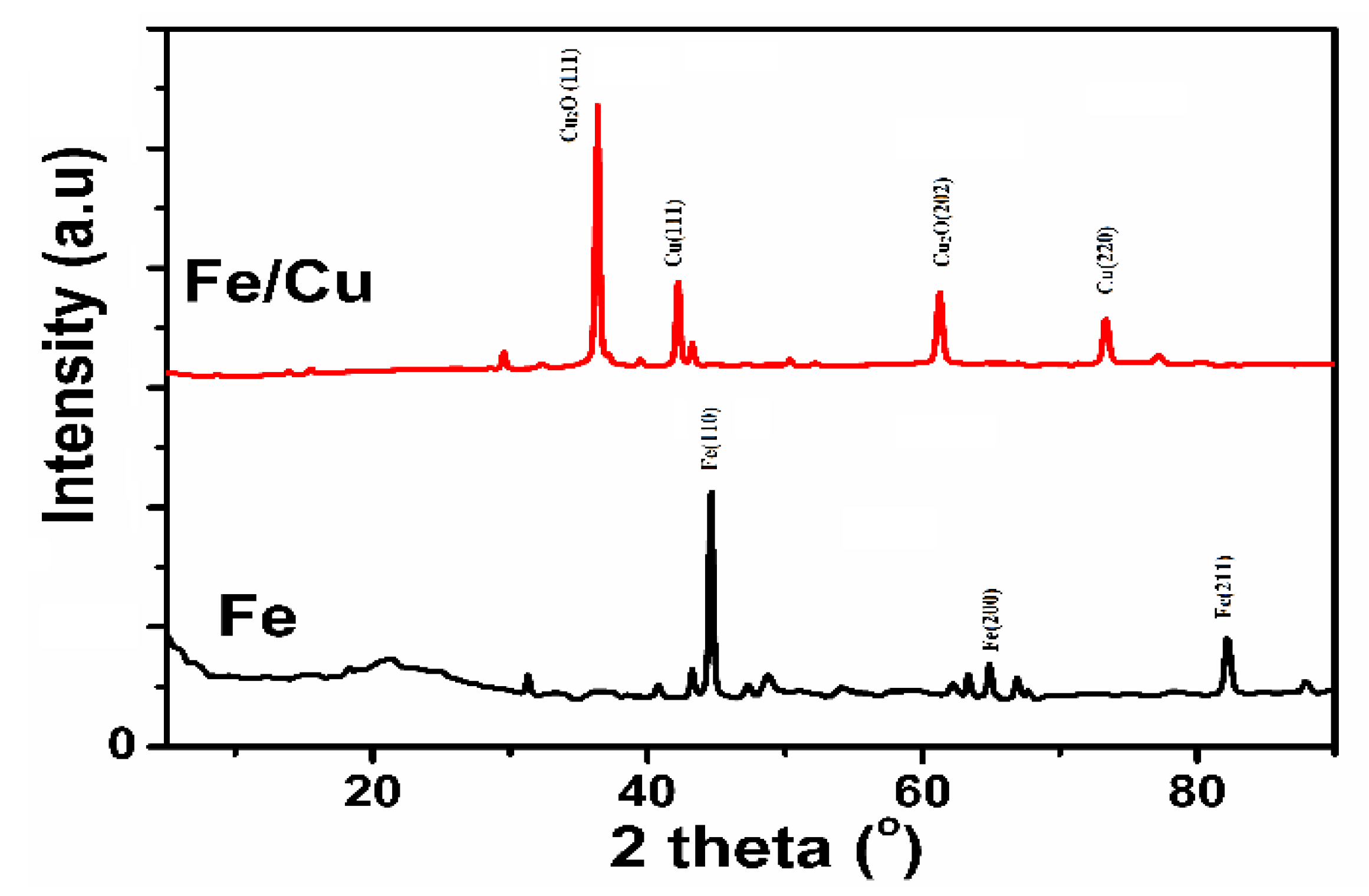

3.1.2. XRD Analysis of Fe/Cu

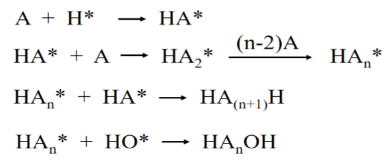

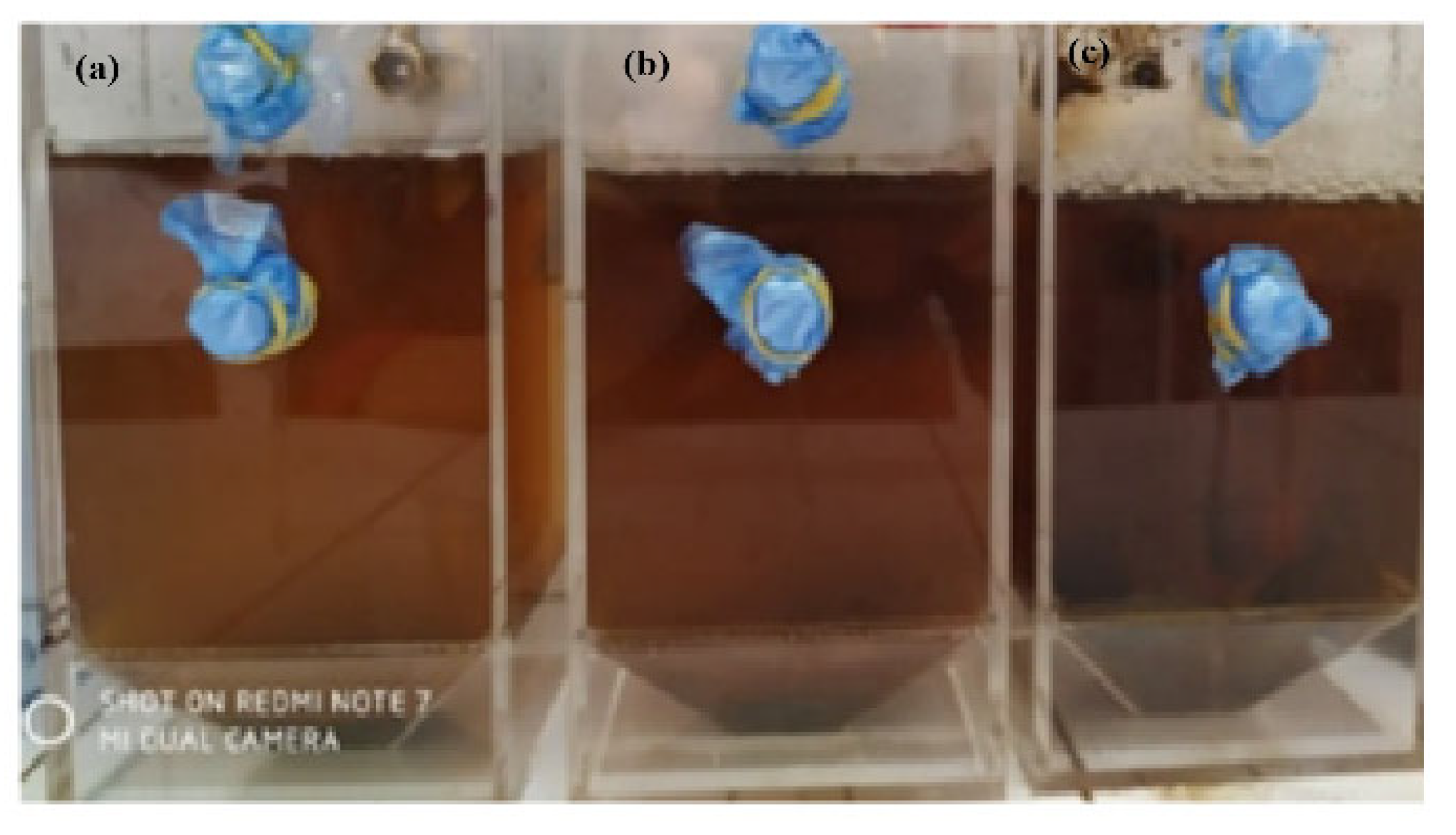

3.2. Effect of Experimental Parameters on the Efficiency of Landfill Leachate Treatment by Internal Electrolysis Method

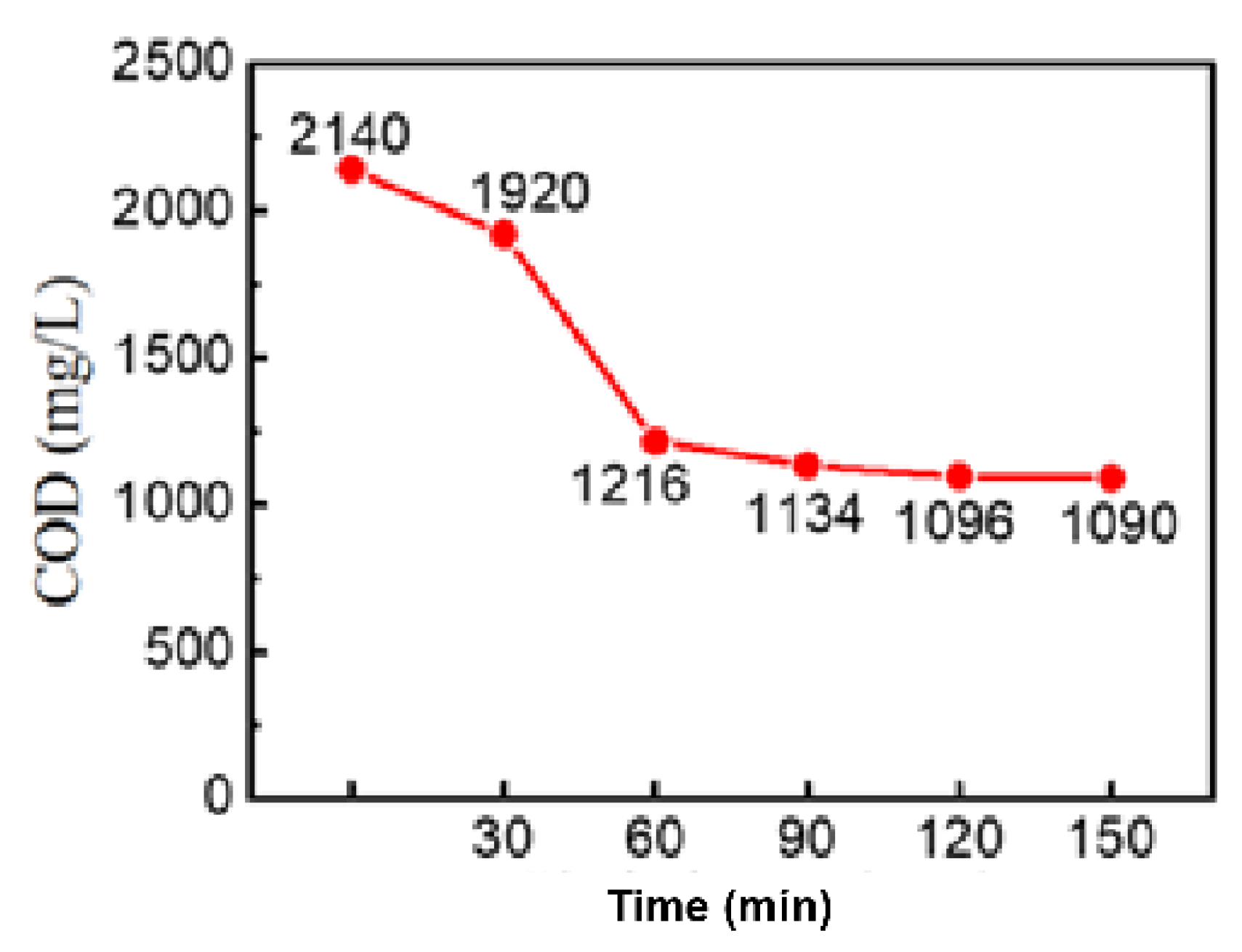

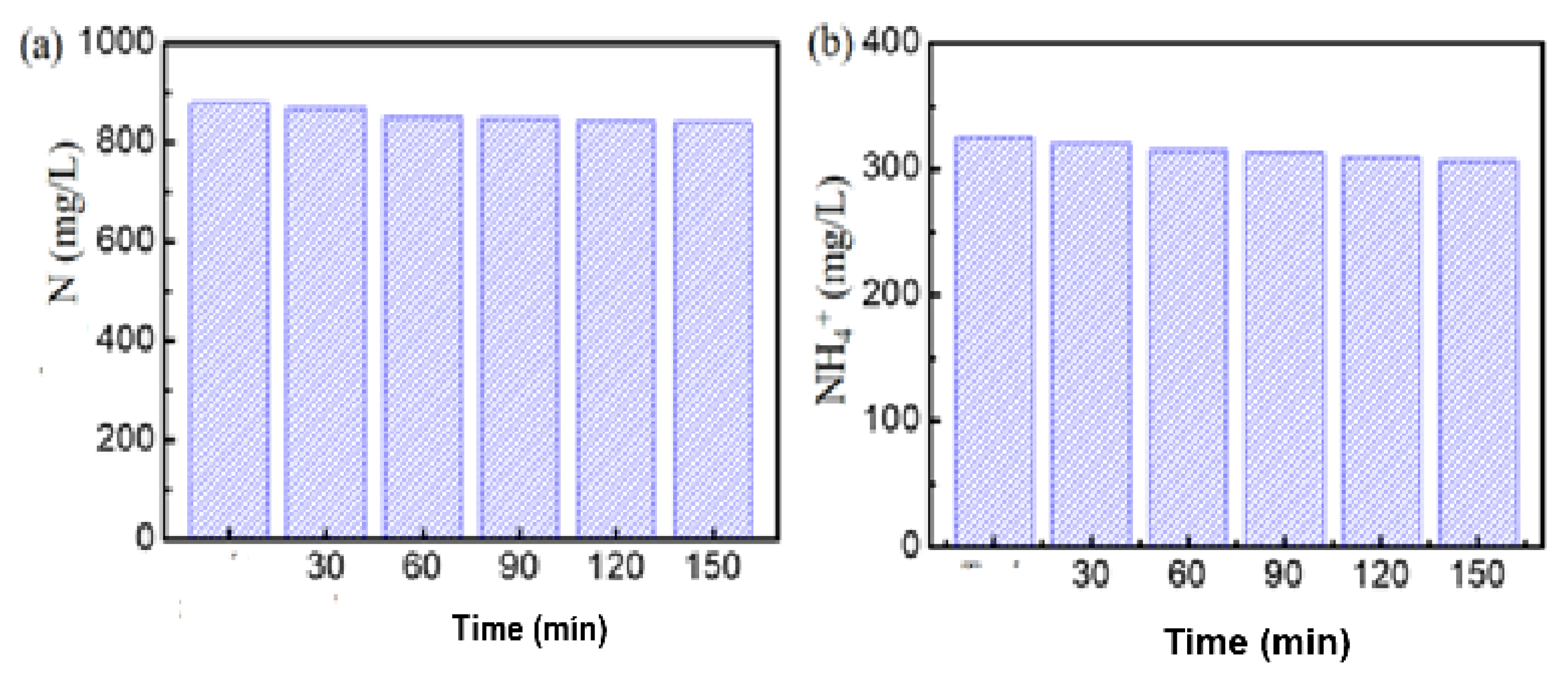

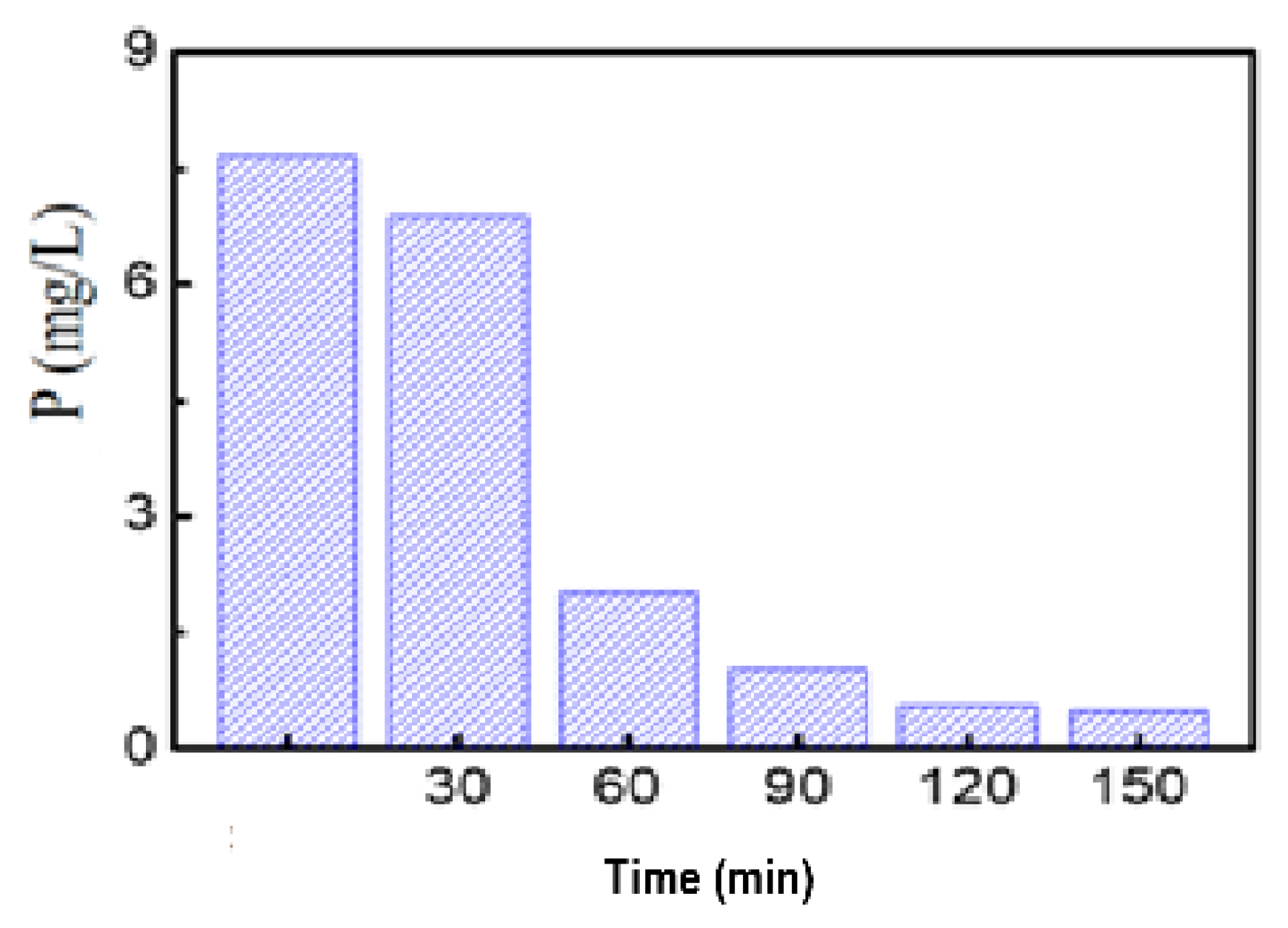

3.2.1. Effect of Treatment Time

-COD Removal Efficiency

Total N and Ammonium Removal Efficiency

P Removal Efficiency

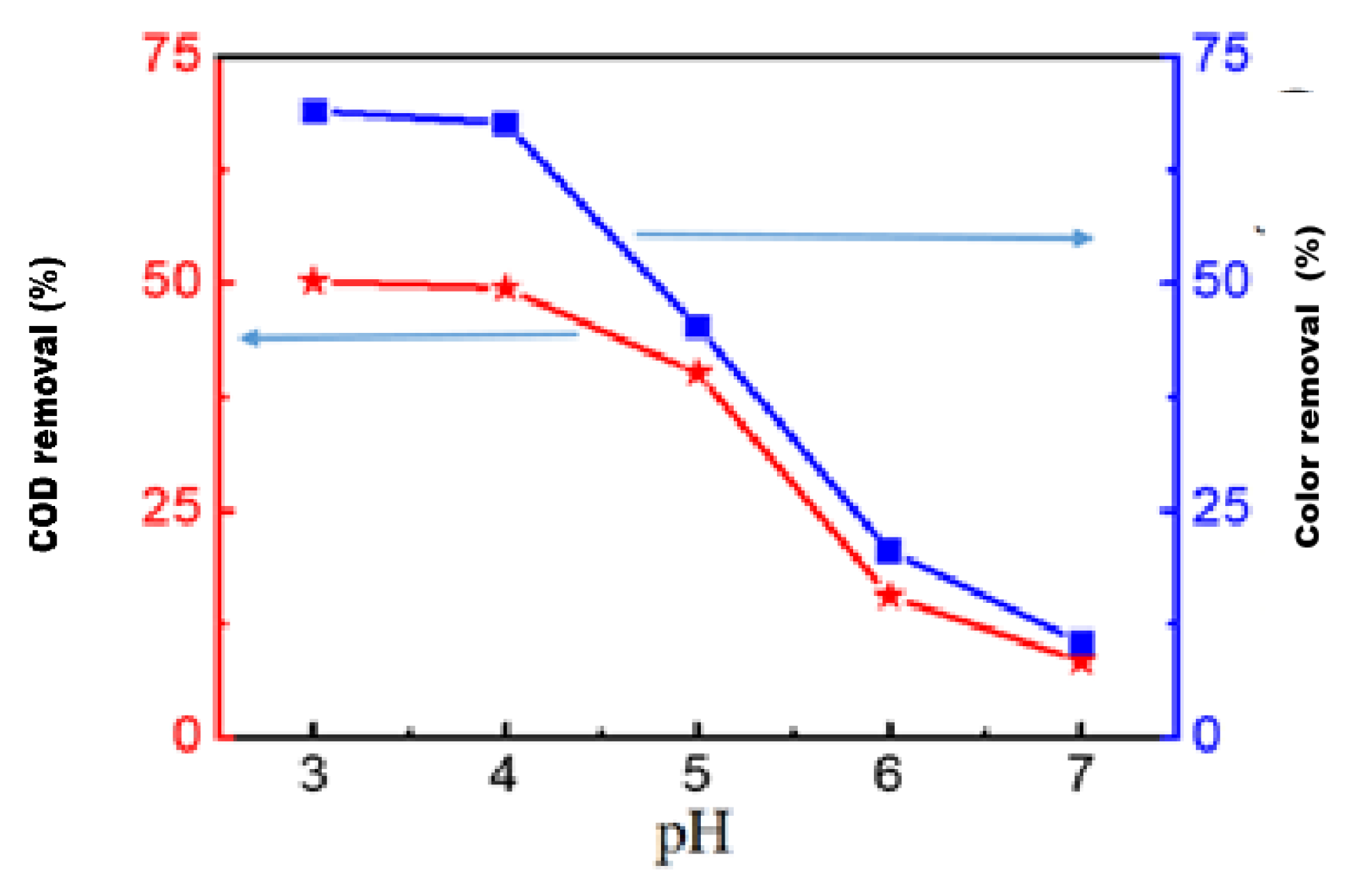

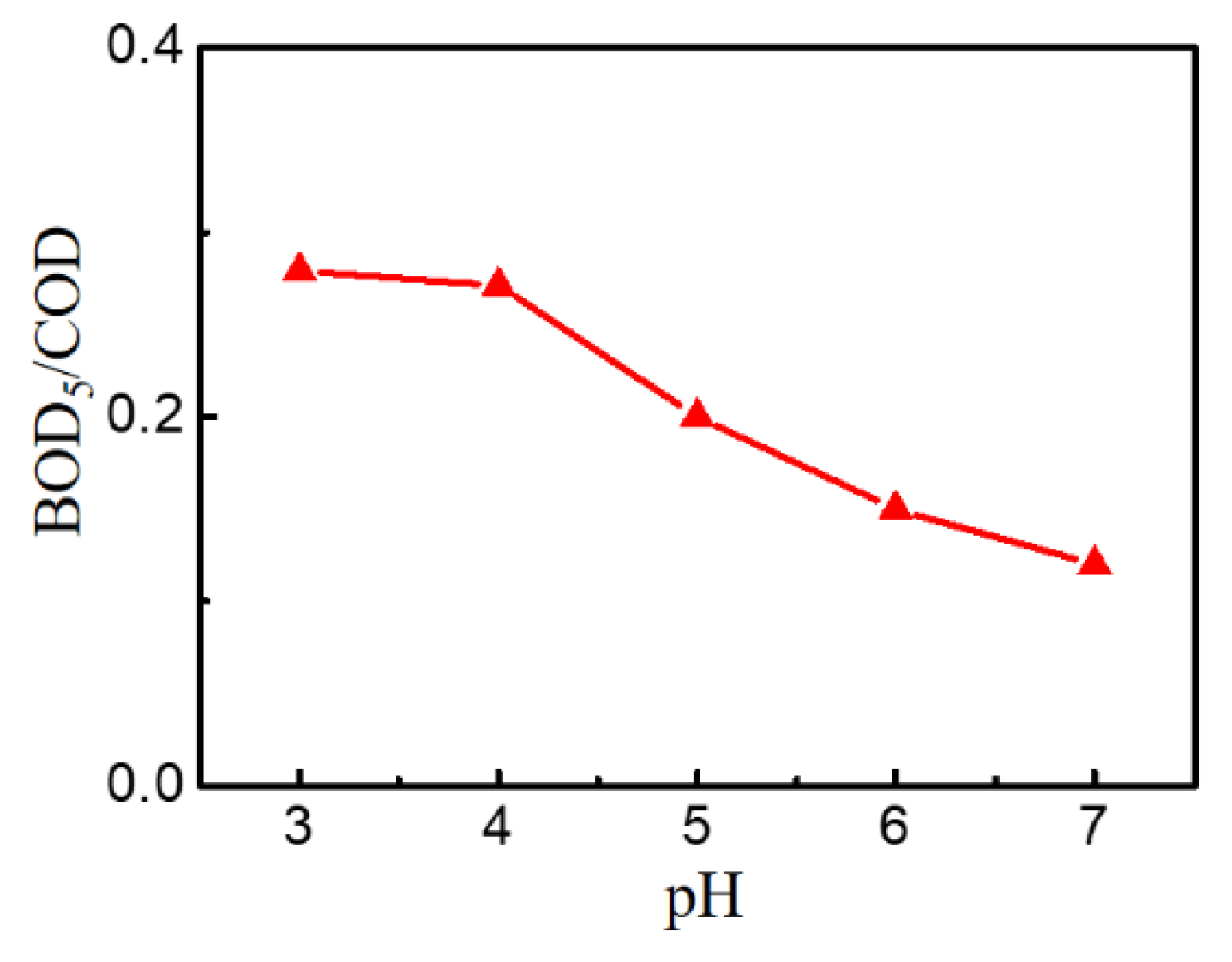

3.2.2. Effect of pH

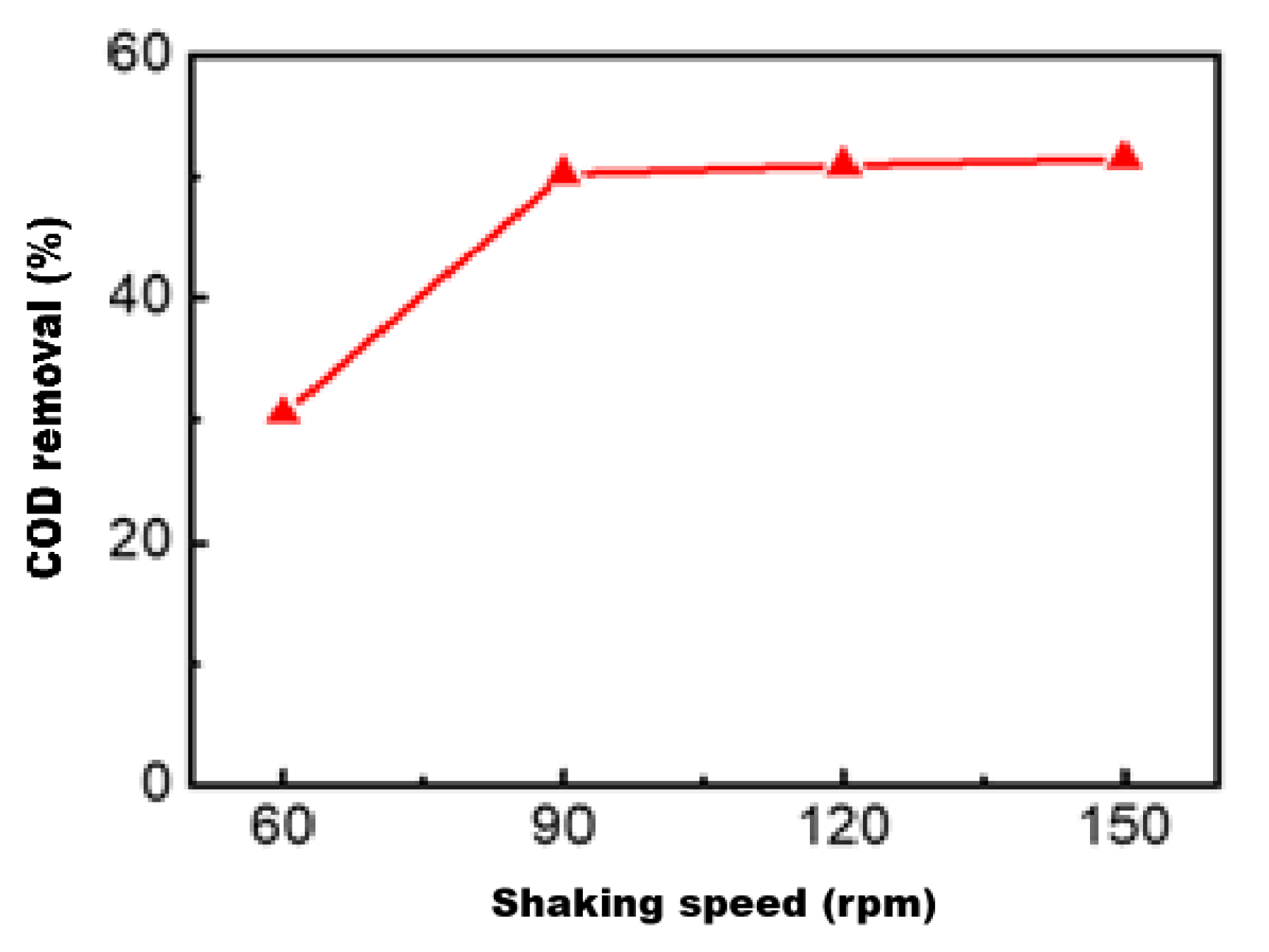

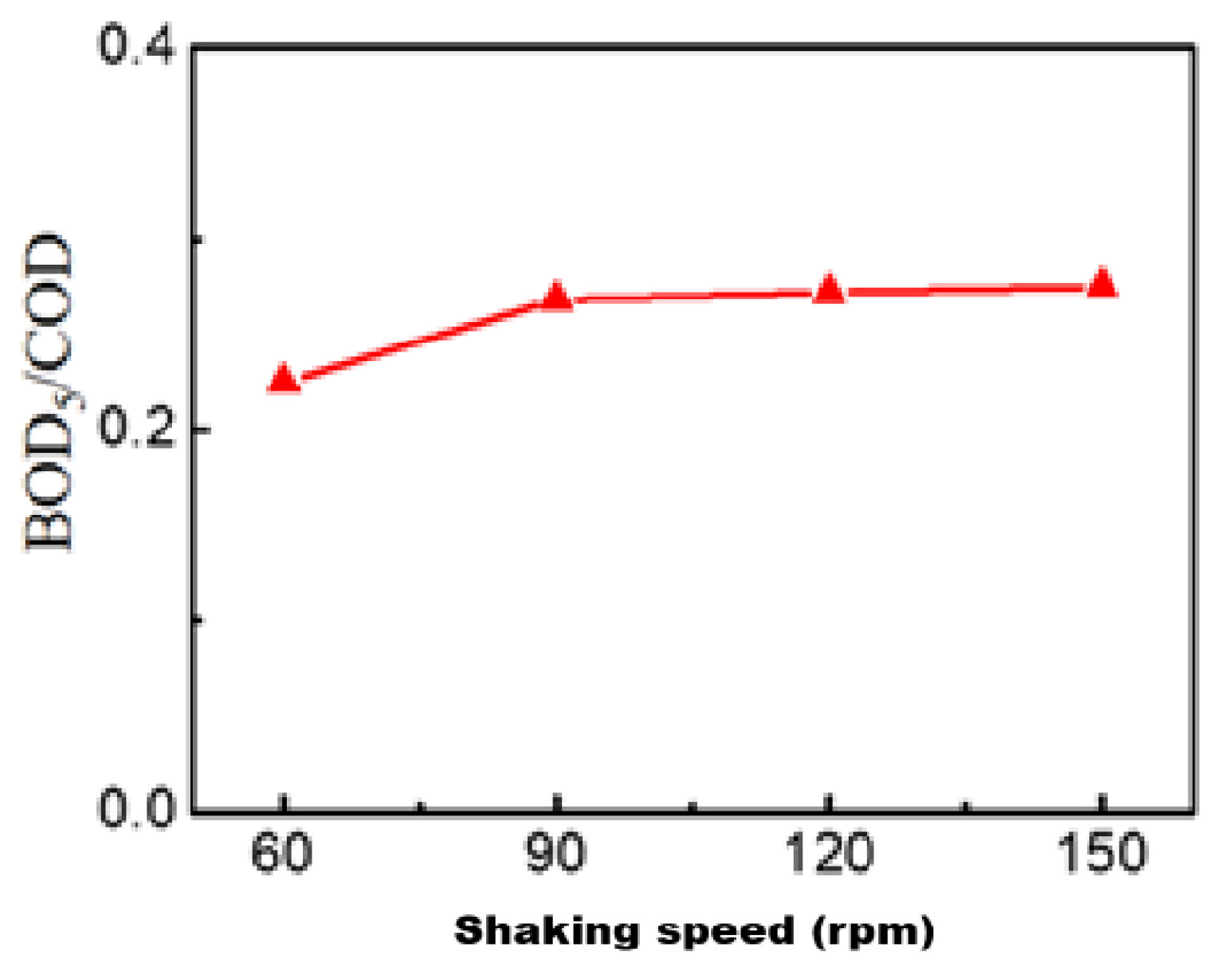

3.2.3. Effect of Shaking Speed

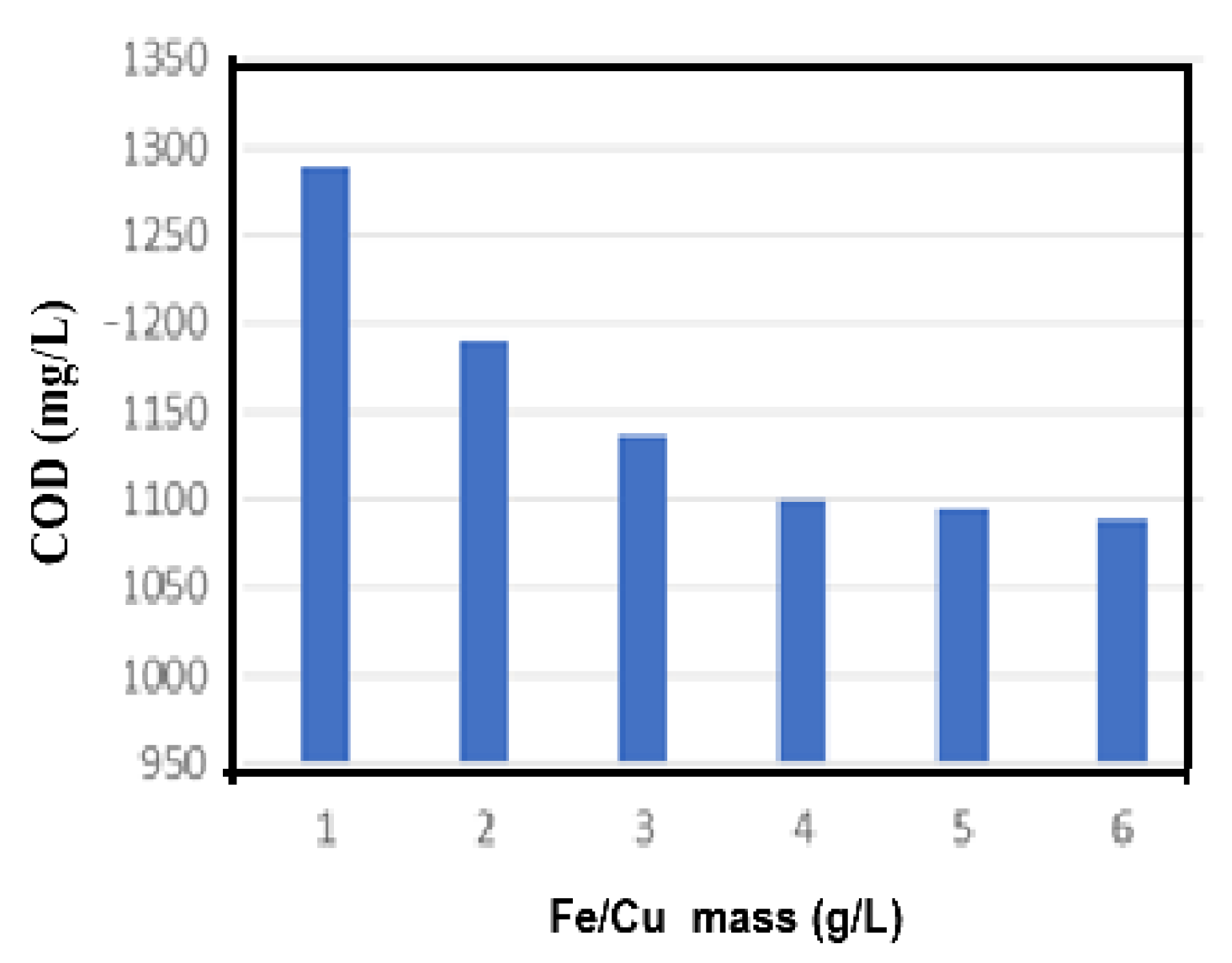

3.2.4. Effect of Fe/Cu Dosage

| Parameters | Before treatment | After lime treatment | After electrolysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| COD (mg/L) | 3000-3500 | 2140 | 1090 |

| Total P (mg/L) | 87-90 | 25 | 2 |

| Total N (mg/L) | 1850-2100 | 895 | 790 |

| NH4+ (mg/L) | 450-894 | 325 | 301 |

| pH | 7.2-8.5 | 11 | 6.5-7.0 |

3.3. Wastewater Treatment After Electrolysis by Anaerobic-Anoxic-Oxid Moving Bed Biofilm Reactor (A2O-MBBR)

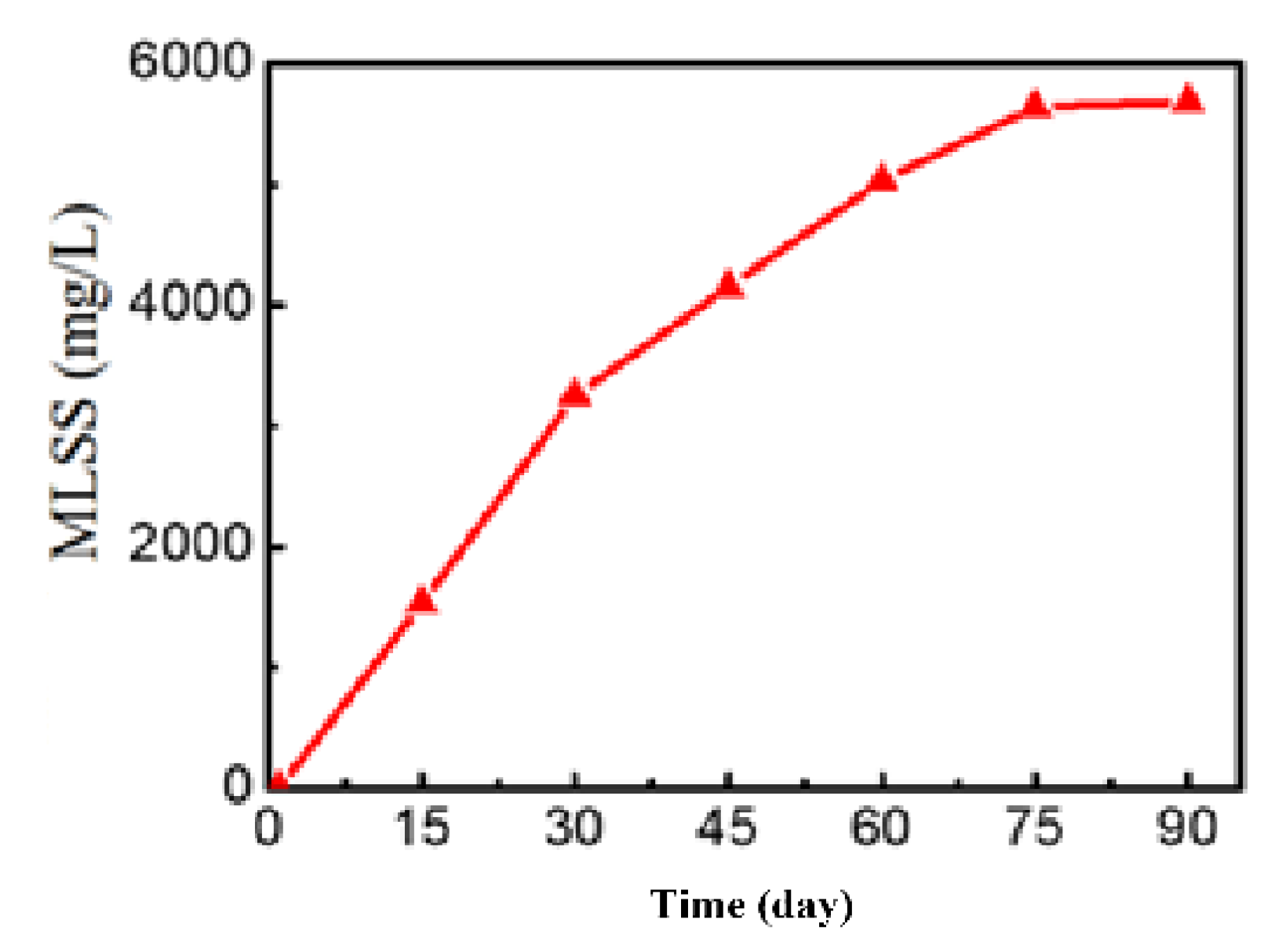

3.3.1. Investigation of Activated Sludge Development

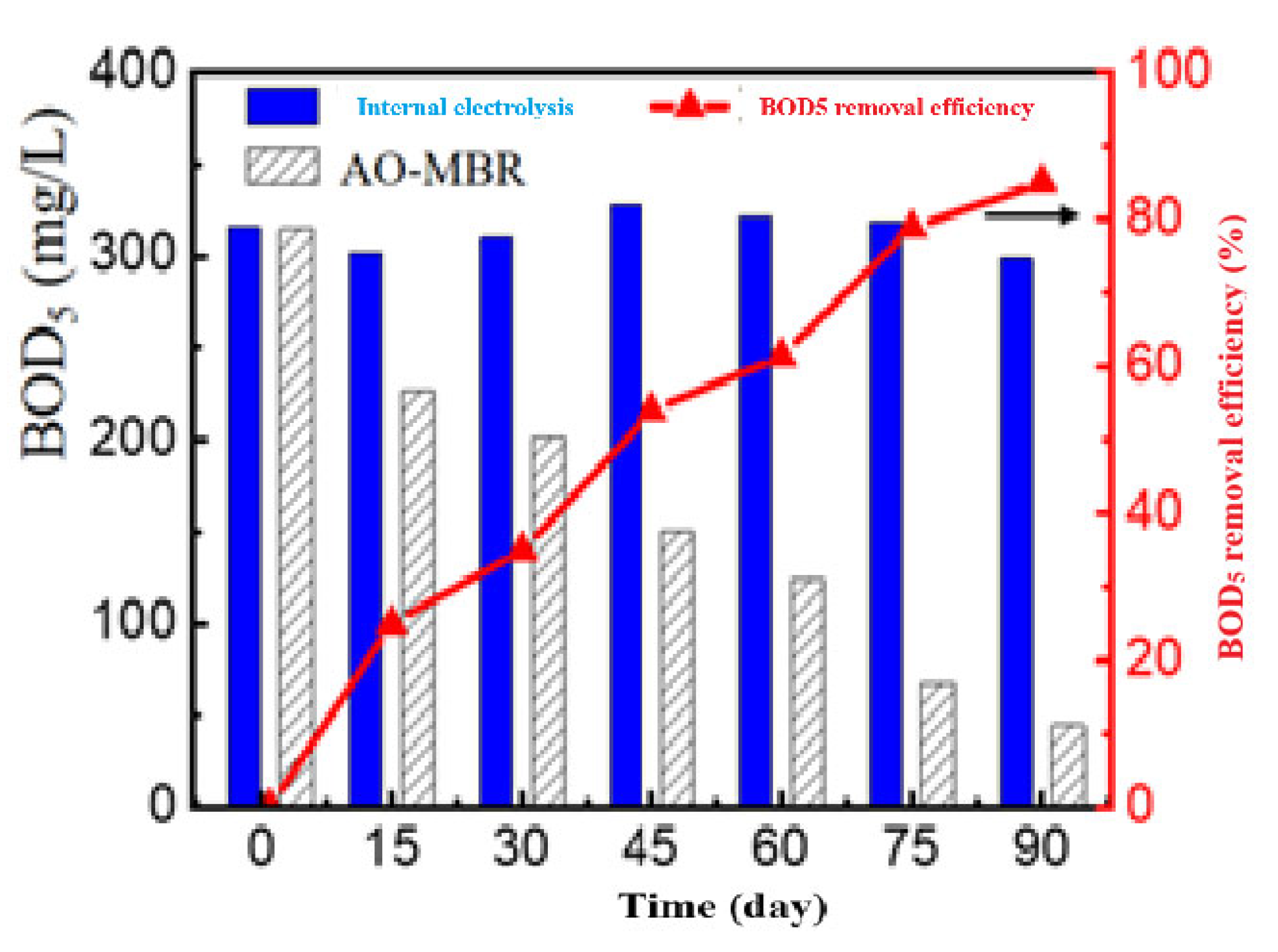

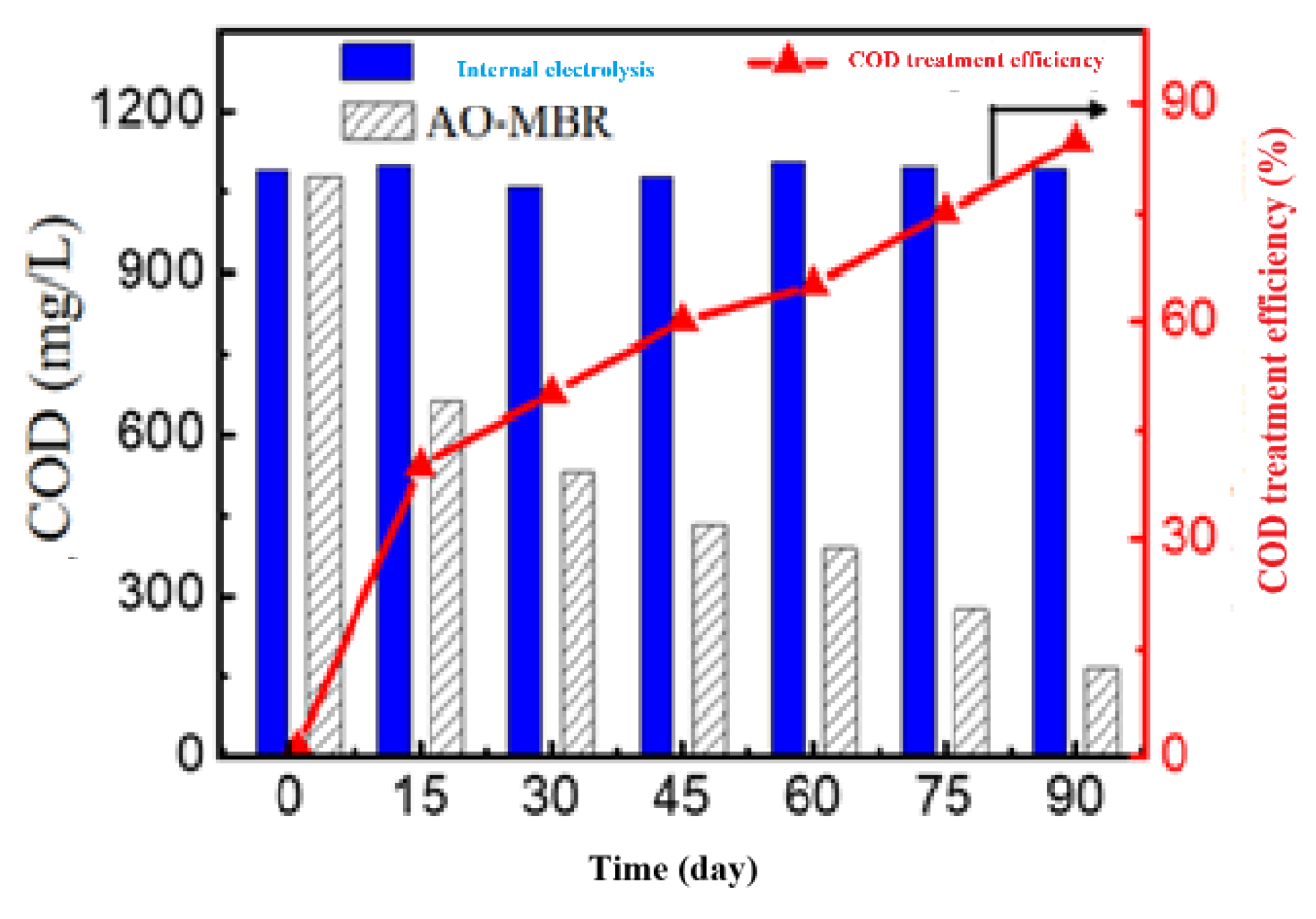

3.3.2. COD Removal Efficiency

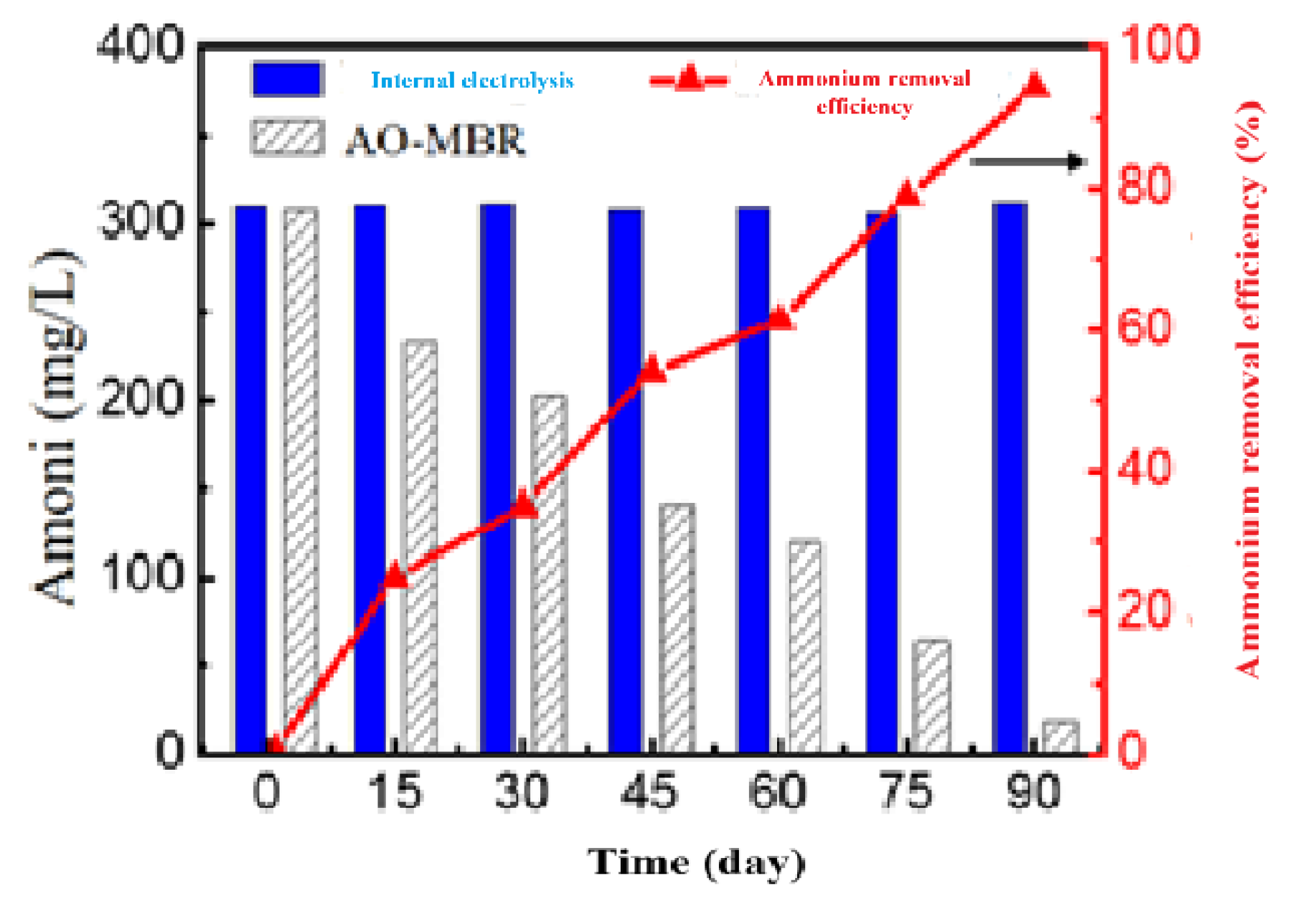

3.3.3. Ammonium Removal Efficiency

3.3.4. BOD5 Removal Efficiency

3.3.5. The Treatment Efficiency of the Entire AAO Process

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- V.H. Tap. Research on waste water treatment research by ozonation method. PhD, Academy of Science and Technology/Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology (2015).

- N. H. Khanh. Comparative study of domestic and foreign technologies for leachate treatment, on that basis, propose leachate treatment technology to meet type B according to Vietnamese standards (TCVN) for landfills in Hanoi city. Institute of Environmental Technology (2007), Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology.

- D. X. Hien. Research on the development of an integrated physicochemical-biological technology that is adaptive, effective, safe and sustainable with the ecological environment to treat leachate at concentrated landfills. State project, KC08.05/11-15, Hanoi University of Science and Technology, (2016).

- L. M. Ma, W. X. Zhan. Enhanced Biological Treatment of Industrial Wastewater With Bimetallic Zero-Valent Iron. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 5384–5389. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D. T. Huong, V. T. Nguyen, X. L. Ha, H. L. Nguyen, T. T. Duong, D. C. Nguyen and H. Tham Nguyen. Enhanced Degradation of Phenolic Compounds in Coal Gasification Wastewater by Methods of Microelectrolysis Fe-C and Anaerobic-Anoxic-Oxic Moving Bed Biofilm Reactor (A2O-MBBR). Processes 2020, 8, 1258. [CrossRef]

- J. Wiszniowski, D. Robert, J. Surmacz-Gorska, K. Miksch, J. V. Weber. Landfill leachate treatment methods: A review. Environmental Chemistry Letters 2006, 4, 51–61.

- L. Q. Wang, Q. Yang, D. B. Wang, X. M. Li, K. X. Yi. Advanced landfill leachate treatment using iron-carbonmicroelectrolysis- Fenton process: Process optimization and columnexperiments. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2016, 318, 460–467. [CrossRef]

- G. Del Moro, L. Prieto-Rodríguez, M. De Sanctis, C. Di Iaconi, S. Malato, G. Mascolo. Landfill leachate treatment: Comparison of standalone electrochemical degradation and combined with a novel biofilter. Chemical Engineering Journal 2016, 288, 87–98. [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Wu, J.; Wang, J. Treatment of high mass concentration coking wastewater using enhancement catalytic iron carbon internal-electrolysis. Journal of Jiangsu University-Natural Science Edition 2010, 31, 348–352. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, S.-Y.; Chiu, P.C.; Kim, B.J.; Cha, D.K. Enhancing Fenton oxidation of TNT and RDX through pretreatment with zero-valent iron. Water Research 2003, 37, 4275–4283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Sun, G.; Yang, T.; Zhang, B.; He, Y.; Wang, X. A preliminary study of anaerobic treatment coupled with micro-electrolysis for anthraquinone dye wastewater. Desalination 2013, 309, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Bian, W.; Shi, J. 4-chlorophenol degradation by pulsed high voltage discharge coupling internal electrolysis. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2009, 166, 1474–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, D.; Guo, Yue Q.; Lee, H.S.; Wu, W. M.; Liang, B.; Wang, A. J.; Cheng, H.Y. Enhanced decolorization of azo dye in a small pilot-scale anaerobic baffled reactor coupled with biocatalyzed electrolysis system (ABR–BES): A design suitable for scaling-up. Bioresource Technology 2014, 163, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Guo, S.; Li, F. Treatment of oilfield produced water by anaerobic process coupled with micro-electrolysis. Journal of Environmental Sciences 2010, 22, 1875–1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, R.; Chai, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Shu, Y.; Zhao, J. Degradation of organic wastewater containing Cu–EDTA by Fe–C micro-electrolysis. Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China 2012, 22, 983–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, L.; Zhang, G.; Meng, Q.; Xu, L.; Lv, B. Enhanced MBR by internal micro-electrolysis for degradation of anthraquinone dye wastewater. Chemical Engineering Journal 2012, 210, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Guo, S.; Guo, C.; Dai, D.; Jiao, X.; Ma, T.; Chen, J. Stability of Fe–C micro-electrolysis and biological process in treating ultra-high concentration organic wastewater. Chemical Engineering Journal 2014, 255, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, X.; Xu, X.; Lu, M.; Li, H. Pretreatment of Oil Shale Retort Wastewater by Acidification and Ferric-Carbon Micro-Electrolysis. Energy Procedia 2012, 17, 1655–1661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X. Interior microelectrolysis oxidation of polyester wastewater and its treatment technology. J. Hazard. Mater. 2009, 169, 480–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- H. Cheng, W. Xu, J. Liu, H. Wang, Y. He, G. Chen. Pretreatment of wastewater from triazine manufacturing by coagulation, electrolysis, and internal microelectrolysis. J. Hazard. Mater. 2007, 146, 385–392. [CrossRef]

- X.C. Ruan, M.Y. Liu, Q.F. Zeng, Y.H. Ding. Degradation and decolorization of reactive red X-3B aqueous solution by ozone integrated with internal micro-electrolysis. Purif. Technol. 2010, 74, 195–201. [CrossRef]

- Bo, L; Zhang, Y; Chen, Z. Y; Yang, P; Zhou, Y. X; Wang, J. L. Removal of p-nitrophenol (PNP) in aqueous solution by the micron-scale iron-copper (Fe/Cu) bimetallic particles. Applied Catalysis B: Environmental 2014, 144, 816–830. [Google Scholar]

- Gang, Q; Dan, G. Pretreatment of petroleum refinery wastewater by microwaveenhanced Fe0/GAC micro-electrolysis. Desalination and Water Treatment 2014, 52, 2512–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiaoying, Z; Mengqi, J; Xiang, Z; Wei, C; Dan, L; Yuan, Z; Xiaoyao, S. Enhanced removal mechanism of iron carbon micro-electrolysis constructed wetland on C, N, and P in salty permitted effluent of wastewater treatment plant. Science of The Total Environment 2019, 1, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei Qin, Guo Liang Zhang, Qin Meng, Lu Sheng Xu, Bo Sheng Lu. Enhanced MBR by internal micro-electrolysis for degradation of anthraquinone dye wastewater. Chemical Engineering Journal 2010, 2012, 575–584.

- Diwen Ying, Xinyan Xu, Chen Yang, Yalin Wang, Jinping Jia. Treatment of mature landfill leachate by a continuous modular internal micro-electrolysis Fenton reactor. Research on Chemical Intermediates 2013, 39, 2763–2776. [CrossRef]

- Son Jianyang, Li Weicheng, Li Yuyou, Mosa Ahmed, Wang Hongyu, Jin Yong. Treatment of landfill leachate RO concentration by Iron–carbon micro–electrolysis (ICME) coupled with H2O2 with emphasis on convex optimization method. Environmental Pollutants and Bioavailability 2019, 31, 49–55. [CrossRef]

- Luo Kun, Pang Ya, Li Xue, Chen Fei, Liao Xingsheng. Landfill leachate treatment by coagulation/flocculation combined with microelectrolysis-Fenton processes. Environmental technology 2019, 40, 1862–1870. [CrossRef]

- Yang Qi, Liu Sheng, Zhong Yu, Chen Ren, Li Xiaoming, Zeng Guangming. Enhancing biodegradability of landfill leachate using iron-carbon microelectrolysis with fenton process. Journal of Hunan University (Nature Scienece) 2015, 42, 125–131.

- Xiaoqing Dong, Hui Liu, Ji Li, Ruiqi Gan, Quanze Liu, Xiaolei Zhang. Fenton Oxidation Combined with Iron–Carbon Micro-Electrolysis for treating leachate generated from Thermally Treated Sludge. Separations 2023, 10, 568.

- Ying Diwen, Xu Xinyan, Li Kan, Wang Yalin, Jia Jinping. Design of a novel sequencing batch internal micro-electrolysis reactor for treating mature landfill leachate. Chemical Engineering Research and Design 2012, 90, 2278–2286. [CrossRef]

- Joanna Ładynska, Małgorzata Kucharska, Jeremi Naumczyk. An Innovative Approach to the Internal Microelectrolysis (IME) Process applied to stabilized landfill leachate. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 2201. [CrossRef]

- Zang, H.; Xiang, L.; Zhang, D.; Qing, H. Treatment of landfill leachate by internal microelectrolysis and sequent Fenton process. Desalination Water Treat. 2012, 47, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, D.; Peng, J.; Xu, X.; Li, K.; Wang, Y.; Jia, J. Treatment of mature landfill leachate by internal micro-electrolysis integrated with coagulation: A comparative study on a novel sequencing batch reactor based on zero valent iron. J. Hazard. Mater. 2012, 229–230, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Chen, J.; Xie, Z.; Xu, X. Treatment of nanofiltration concentrates of mature landfill leachate by a coupled process of coagulation and internal micro-electrolysis adding hydrogen peroxide. Environ. Technol. 2014, 36, 1001–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Cheng, X.G.; Yin, P.H.; Lu, G.; Suo, J.C. The Performance of Microelectrolysis in Improving the Biodegradability Landfill Leachate. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2013, 448-453, 1399–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Chen, S.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, C.; Liu, J.; Luo, J.; Song, G.; Qian, G.; Song, L.; Xia, M. Simultaneous removal of organic matter and nitrate from bio-treated leachate via iron-carbon internal micro-electrolysis. RSC Advances 2015, 5, 68356–68360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.Y.; Xu, Y.Z.; Zhou, S.; Liu, J.M.; Cheng, Y.; Fu, G.Y.; He, X.S. Field-scale performance of microelectrolysis-Fenton oxidation process combined with biological degradation and coagulative precipitation for landfill leachate treatment, Environmental Protection, Pollution and Treatment. In Proceedings of the 2019 4th International Conference on Advances in Energy and Environment Research (ICAEER 2019), Shanghai, China, 16–18 August 2019; 118. [Google Scholar]

- Kucharska, M.A.; Mirehbar, S.K.; Łady’nska, J.A. Novel combined IME-O3/OH*/H2O2 process in application for mature landfill leachate treatment. J. Water Process Eng. 2022, 45, 102441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogacki, J.; Marcinowski, P.; El-Khozondar, B. Treatment of Landfill Leachates with Combined Acidification/Coagulation and the Fe0/H2O2 Process. Water 2019, 11, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah Naz Ahmed, Christopher Q.Lan. Treatment of landfill leachate using membrane bioreactors: A review. Desalination 2012, 287, 41–54. [CrossRef]

- Liu Cheng Dong, Song Xiao Ling. Application of A2O Biological Denitrification Technology for Coking Waste Water Treatment. Journal of Coal Chemical Industry 2006, 2, 51–53.

- Min Zhang, Joo Hwa Tay, Yi Qian and Xia Sheng Gu. Coke plant wastewater treatment by fixd biofilm system for COD and NH3-N removal. Water Research 1998, 32, 519–527. [CrossRef]

- S. J. You, C. L. Hsu, S. H. Chuang, C. F. Ouyang. Nitrification efficiency and nitrifying bacteria abundance in combined AS-RBC and A2O systems. Water Research 2003, 37, 2281–2290. [CrossRef]

- Bramha Gupta, Ashok Kumar Gupta, Partha Sarathi Ghosal, Saurabh Lal, Duduku Saidulu, Ashish Srivastava, Maharishi Upadhyay. Recent advances in application of moving bed biofilm reactor for wastewater treatment: Insights into critical operational parameters, modifications, field-scale performance, and sustainable aspects. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2022, 10, 107742.

- Shabnam Murshid, AdithyaJoseph Antonysamy, GnanaPrakash Dhakshinamoorthy, Arun Jayaseelan, Arivalagan Pugazhendhi. A review on biofilm-based reactors for wastewater treatment: Recent advancements in biofilm carriers, kinetics, reactors, economics, and future perspectives. Science of the Total Environment 2023, 892, 164796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuli Liu, Yatong Gao, Xiaohong Han, Jiajun Hua, Yuhong Zhang, Glen T. Daigger, Qi Li, Ning Guo, Xiao Mi, Jia Kang, Peng Zhang. Electrochemical membrane bioreactors for wastewater treatment: Mechanisms of membrane fouling control and applications to refractory pollutants. Journal of Environmental Chemical Engineering 2025, 13, 118242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong Zhen Peng, Xiao Lian Wang, Bai Kun Li. Anoxic biological phosphorus uptake and the effect of excessive aeration on biological phosphorus removal in the A2O process. Desalination 2006, 89, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei Zeng, Lei Li, Ying Ying Yang, Xiang Dong Wang, Yong Zhen Peng. Denitrifying phosphorus removal and impact of nitrite accumulation on phosphorus removal in a continuous anaerobic-anoxic-aerobic (A2O) process treating domestic wastewater. Enzyme and Microbial Technology 2011, 48, 134–142. [CrossRef]

- Zi Xing Wang, Xiao Chen Xua, Zheng Gong, Feng Lin Yang. Removal of COD, phenols and ammonium from Lurgi coal gasification wastewater using A2O-MBR system. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2012, 235- 236, 78–84. [CrossRef]

- J. Rajesh Banu, Do Khac Uan, Ick-Tae Yeom. Nutrient removal in an A2O-MBR reactor with sludge reduction. Bioresource Technology 2009, 100, 3820–3824. [CrossRef]

- Dong Ying, Wang Zhiwei, Zhu Chaowei, Wang Qiaoying. A forward osmosis membrane system for the post-treatment of MBR-treated landfill leachate. Journal of membrane science 2014, 471, 192–200. [CrossRef]

- Judit Ribera-Pi, Marina Badia-Fabregat, Jose Espi, Frederic Clarens, Irene Jubany. Decreasing environmental impact of landfill leachate treatment by MBR, RO and EDR hybrid treatment. Environmental technology 2021, 42(22), 3508–3522. [CrossRef]

- Zhang Jiao, Kang Xiao, Xia Huang. Full-scale MBR applications for leachate treatment in China: Practical, technical, and economic features. Journal of hazardous materials 2020, 389, 122138. [CrossRef]

- Eun-Tae Lim, Gwi-Taek Jeong, Sung-Hun Bhang, Seok-Hwan Park, Don-Hee Park. Evaluation of pilot-scale modified A2O processes for the removal of nitrogen compounds from sewage. Bioresource Technology 2009, 100, 6149–6154. [CrossRef]

- Wei Zeng, Lei Li, YingYing Yang, Shu Ying Wang, Yong Zhen Peng. Nitritation and denitritation of domestic wastewater using a continuous anaerobic–anoxic–aerobic (A2O) process at ambient temperatures. Bioresource Technology 2010, 101, 8074–8082. [CrossRef]

- Yong Qing Gao, Yong Zhen Peng, Jing Yu Zhang, Shu Ying Wang, Jian Hua Guo. Biological sludge reduction and enhanced nutrient removal in a pilot-scale system with 2-step sludge alkaline fermentation and A2O process. Bioresource Technology 2011, 102, 4091–4097. [CrossRef]

- Tzu-Yi Pai. Modeling nitrite and nitrat variations in A2O process under different return oxic mixed liquid using an extended model. Process Biochemistry 2007, 42, 978–987. [CrossRef]

- Hye Ok Park, Sanghwa Oh, Rabindra Bade, and Won Sik Shin. Application of A2O moving-bed biofilm reactors for textile dyeing wastewater treatment. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2010, 27, 893–899. [CrossRef]

| Numbers | Parameter | Unit | New leachate ≤1 year | Old leachate (1-3 years old) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | pH | - | 4.89-6.41 | 7.81-7.89 |

| 2 | TDS | mg/L | 7.301-16.209 | 6.014-14.145 |

| 3 | Hardness | mg (CaCO3)/L | 5,833-9,677 | 1.26-1,867 |

| 4 | SS | mg/L | 1,760-4,311 | 169-243 |

| 5 | COD | mg (O2)/L | 38,533-65,333 | 1,092-2,507 |

| 6 | BOD | mg (O2)/L | 30,000-48,000 | 200-735 |

| 7 | VFA | mg/L | 17.677-25.2 | 26-33 |

| 8 | Total P | mg/L | 55.8-89.6 | 4.7-0.1 |

| 9 | Total N | mg/L | 977-1,800 | 515-1.874 |

| 10 | NH3 | mg/L | 781-1,764 | 512-1.874 |

| 11 | Organic nitrogen | mg/L | 196-470 | 3-4.8 |

| 12 | SO42- | mg/L | 1,400-1,590 | 7.5-14 |

| 13 | Cl- | mg/L | 3,960-4,500 | 7.5-14 |

| 14 | Ca2+ | mg/L | 1,670-2,736 | 60-80 |

| 15 | Mg2+ | mg/L | 404-687 | 297-381 |

| 16 | Pb | mg/L | 0.32-4.9 | - |

| 17 | Zn | mg/L | 93-202 | - |

| 18 | Al | mg/L | 0,04-0,5 | - |

| 19 | Mn | mg/L | 14.50-32.70 | - |

| 20 | Ni | mg/L | 2.21-8.02 | - |

| 21 | Total Cr6+ | mg/L | 0.04-0.05 | - |

| 22 | Cu | mg/L | 3.5-4.0 | - |

| 23 | Fe2+ | mg/L | 204-208 | 4.5-6.4 |

| Samples | Elements | % Mass | % Atom |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fe | O | 8.95 | 25.55 |

| Fe | 91.05 | 74.45 | |

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 | |

| Fe/Cu | O | 12.11 | 24.97 |

| Fe | 18.59 | 21.83 | |

| Cu | 69.30 | 53.20 | |

| Total | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Indicator | Before treatment | After Fe/Cu | After A2O - MBBR |

Fe-Cu & A2O-MBBR | QCVN 40: 2011/BTNMT (column B2) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| After treatment | H% | |||||

| BOD5 mg/L | 250 | 258 | 44.8 | 44.8 | 85.2 | 50 |

| COD mg/l | 2140 | 1090 | 156 | 156 | 85.6 | 300 |

| Total N mg/L | 895 | 790 | 47.5 | 47.5 | 94.1 | 60 |

| Total P mg/L | 20 | 2.5 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 98.0 | 4.0 |

| -N mg/L | 335 | 301 | 9.7 | 9.7 | 96.7 | 25 |

| pH | 8.0-9.0 | 6.5 | 6.5 - 7.2 | 6.5 - 7.2 | - | 6.0 - 9.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).