Submitted:

20 January 2025

Posted:

22 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- determination of the impact of different parameters on the effectiveness of the IME process: pH; microelectrodes ratios and doses; time; the addition of H2O2 in different doses and moment of the process;

- determination of the impact of humic substances removal by precipitation in pH 2, 3 and 4 (preliminary coagulation PC) on the IME effectiveness.

- investigation of the validity of soaking of the GAC in LL before the IME process (in different variants).

| Name of the process | Characteristics of LL | Characteristics of microelectrodes | Process parameters | Parameters recognized as optimal | IME efficiency | Bibliography |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microelectrolysis/Fenton process | pH 6.4, NNH4 1,300 mg/L, CaCO3 alcalinity 10,400 mg/L, COD 8,546 mg O2/L |

Cast iron degreased 20 min in ethanol | pH 1,0; 3,0; 5,0; 7,0. Fe0 25; 50; 75 and 100 g/L, H2O2: 97.0, 195.6, 324.9 i 538.8 mM |

Cast iron dosage 75 g/L H2O2 dose 195.6 mM 90 min IME + 105 min IME/H2O2 |

COD removal after IME 38.2%, after IME/H2O2 65.1% |

[1] |

| SIME reactor | COD 538 mgO2/L, BOD5 38 mgO2/L, BOD5/COD 0.07, pH 7,2 |

Scrap cast iron with an area of 0,3-0,4 m2g-1, washed in hexane and washed again in 0,1 M HCl GAC |

Preliminary tests: pH: 3; 5; 7; 8.5, Fe/C mass ratio: 1/3, 2/2; 3/3; 4/3; 5/3; 6/3 SIME Reactor: Air flow rate: 20; 40; 80; 120 L/h, H2O2: 0; 50; 100; 150; 200; 250 mg/L |

SIME Reactor: pH 5, Fe/GAC 1/1, Air flow rate 80 L/h, H2O2 dose 100 mg/L |

COD removal 73.7% in the combined process (without aeration 60 min and with aeration 90 min) COD removal 86.1% in a SIME reactor with H2O2 addition |

[2a, 2b, 2c] |

| Coupled coagulation and aerated micro-electrolysis process with in situ addition of H2O2 | Concentrate LL after the NF process: pH 7,48 COD 6500 mgO2/L, BOD5 200 mgO2/L, BOD5/COD 0.03. |

Medium size scrap cast iron 2 mm, washed 20% NaOH and re-rinsed H2SO4 GAC rinsed in distilled water |

Fe/GAC: 3.0 Air flow rate: 200 L/h H2O2 (30%): 0, 0,24, 0,50; 0,75; 1,0; 1,25; 1,88; 2,5 mM pH: 2; 3; 4; 5; 6; 7 |

pH 4, H2O2: 0.75 mM HRT; 2 h in IME reactor with aeration |

Removal: COD 79.2% OWO 79.9% Color 90.8% UV 81.8% Increase in the BOD5/COD ratio 0.31 |

[25] |

| Microelectrolysis | pH 8.5 ± 0.1 Color: 500 ± 50 COD 3318.2 ± 205.5 mgO2/L BZT5 397.5 ± 48.5 mgO2/L TOC 843.4 ± 71.5 mg/L BOD5/COD 0.12 |

Information not included | Fe/GAC 2/1; 1/1; 1/2; GAC: 1, 5, 10 g/L, pH: 2, 3, 4, Time: 30, 60 and 90 min |

pH 2.0; GAC 10 g/L; Fe0/GAC 2/1; Time 90 min |

Removal: COD 85% Increase in ratio BOD5/COD 0.31 |

[27] |

| Iron–carbon internal micro-electrolysis | Leachate after the biological treatment process: pH 7.5–8. COD 237.3–262.6 mgO2/L NO3-N 69.19–71.8 NO2-N 2.38–2.7 NNH4+-N 217.9–234.0 mg/L |

Commercial Iron dust washed in 0.1 M HCl, and washed 10 times in distilled water AC rinsed 10 times in distilled water Both microelectrodes with a size of M. 100 mesh. |

pH 3, 5, 6, Fe/AC: 12/4 g/L Time: 5, 10, 20, 40 min |

pH 3, Fe/AC: 12/4 g/L Time: 20 min |

Removal: COD 46% TKN 54% |

[28] |

| Microelectrolysis -Fenton process | pH 7.52 ChZT 4980 mgO2/L, BZT5 548 mgO2/L, BOD5/COD 0.11, NNH4 1850 mg/L. |

Cast iron filings with an area of 0.3-0.4 m2/g, defatted in ethanol and washed out in 0.1 M H2SO4 and in water, GAC with a diameter of 2-4 mm |

Preliminary tests: pH: 2; 3; 4, H2O2: 10; 12; 14 ml/L, Fe/GAC: 44; 52; 60 g/L, in a ratio of 3:1, Time: 60 min. Column experiment: LL flow rate: 1.0; 1.5; 2.0; 3.0; 6.0 ml/min |

Fe-C: 55.72% H2O2 12.32 ml/L pH 3.12, Time 60 min |

Removal: COD 74.59% BOD5 0.50 |

[3] |

| Iron–carbon micro–electrolysis (ICME) coupled with H2O2 | RO leachate concentrate: pH 7.35 COD 1980-2100 mgO2/L BOD5 97.0-102.9 mgO2/L BOD5/COD 0.049 |

Cast iron scraps soaked in 2% H2SO4 and rinsed in water GAC size 0.2-1.5 × 4 mm with a specific surface area of 925.2 m2/g, rinsed in distilled water |

Cylindrical reactor: pH 0.64; 2; 4; 6; 7.36, C/Fe with an area of 342; 164; 500.0; 687; 500; 875; 1002, 836. H2O2: 659; 1000; 1500; 2000; 2340 mg/L |

C/Fe with an area of 717.1438, H2O2 1687,6 mg/L, pH 3,8 |

Removal: COD 86.9% |

[29] |

| Coagulation/flocculation process coupled with microelectrolysis-Fenton process (MEF) | pH 8.5 COD 6880 mgO2/L BOD5 572 mgO2/L BOD5/COD 0.081 |

0.3-0.4 m2/g cast iron filings soaked in 0.1 M NaOH, rinsed in water and soaked in 0.1 M H2SO4 and rinsed again in the water, GAC 2-4 mm in size, soaked in raw leachate for 72 h and dried at 40 degrees. |

pH: 2, 3 and 4 H2O2 (30%): 2.66; 3.33; 4.0 mg/L, Fe/GAC: 80; 100; 120 g/L, at ratio 1/1 |

pH 3.20, H2O2 3.57 mg/L Fe/GAC 104,52 g/L |

Removal: COD 40.27% at IME process 90.27% - total in the MEF proces |

[26] |

| Microelectrolysis-Fenton oxidation process combined with biological degradation and coagulative precipitation | pH 7.47 COD, 1590.9-1790.7 mg/L NH3-N 808.1-894.7 mg/L TN 895.9-944.4 mg/L |

Information not included | Full-scale testing: IME tank: f 0.87 × 4.5 m Fenton IME tank: f 1.84 × 0.5 × 0.8 m |

Dose of H2O2 (27.5%) 25 L four times diluted | Removal: COD 85% Metal content > 60% |

[30] |

| Process IME-O3/OH-/H2O2 | COD 1224 mgO2/L TOC 578 mg/L BOD5 220 mgO2/L, BOD5/ChZT 0.18, pH 7,2 |

Cast iron filings with size 2-4 mm, soaked in ethanol for 2 hours, GAC from walnut shells with a size of 0.4–0.85 mm and a surface area of 1100 m2/g |

Glass reactor with a volume of 0.5 L, Fe/GAC: 20/10, 20/20, 20/40, 20/60, 20/80, 20/100, and 20/120 g/L, Experiment time: 60 minutes |

Fe/GAC 20/80 g/L | Removal: COD 76,7% at IME process total COD removal 95.4% at IME-O3/OH-/H2O2 |

[31] |

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. The Characteristics of Raw LL

3.2. The Impact of Different Parameters on the Efficency of IME Process

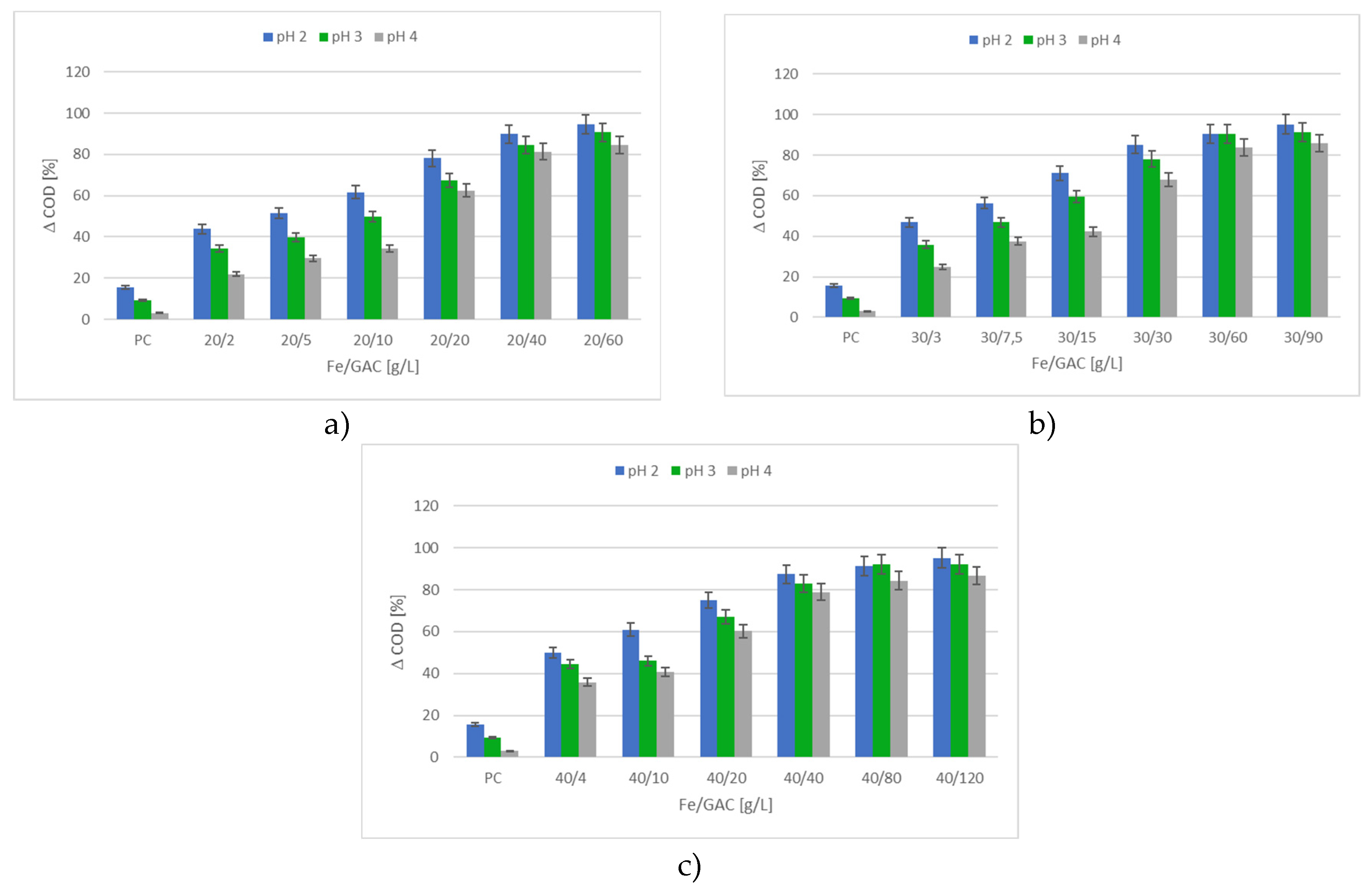

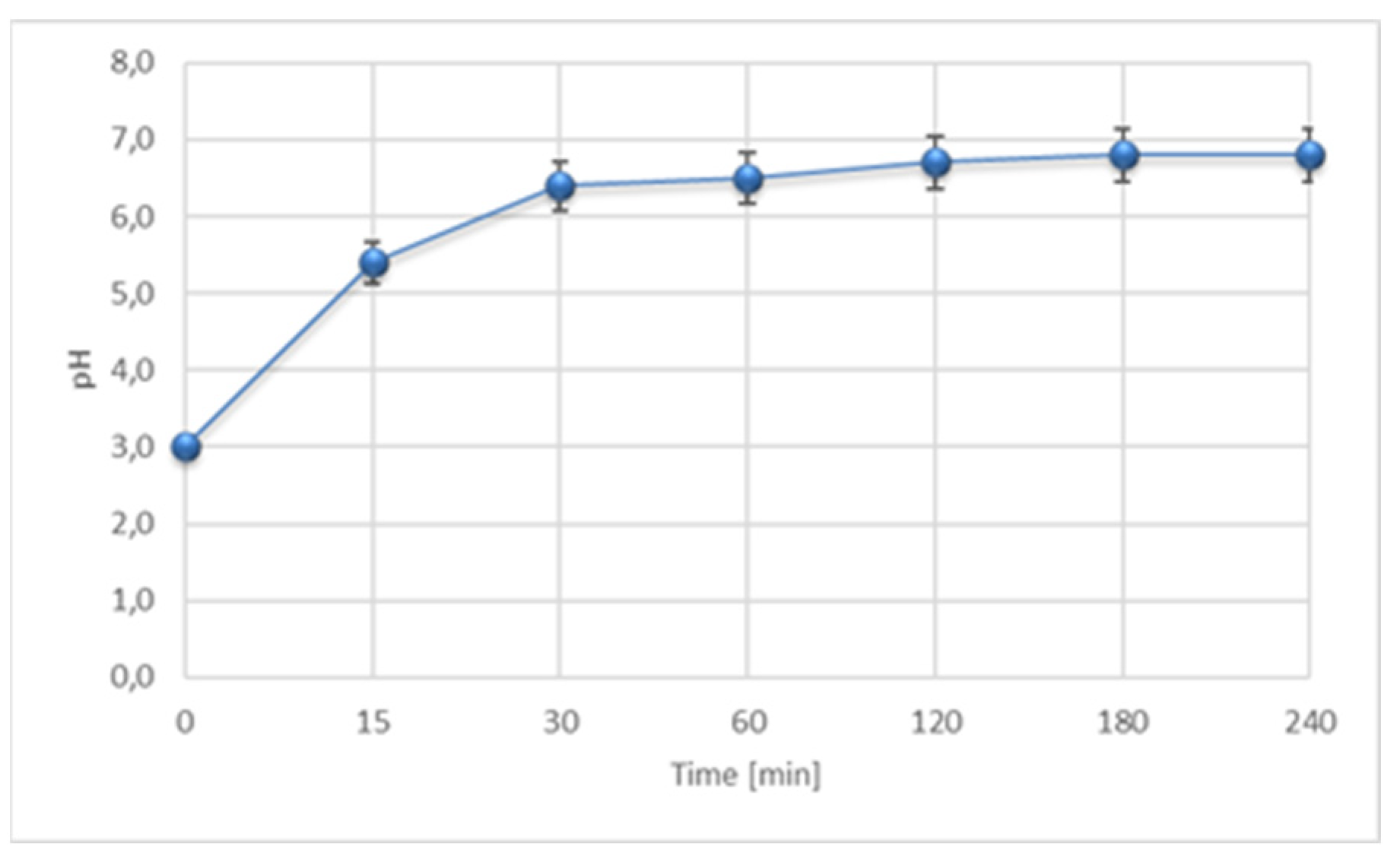

3.2.1. The Impact of pH and PC on the Efficiency of IME Process

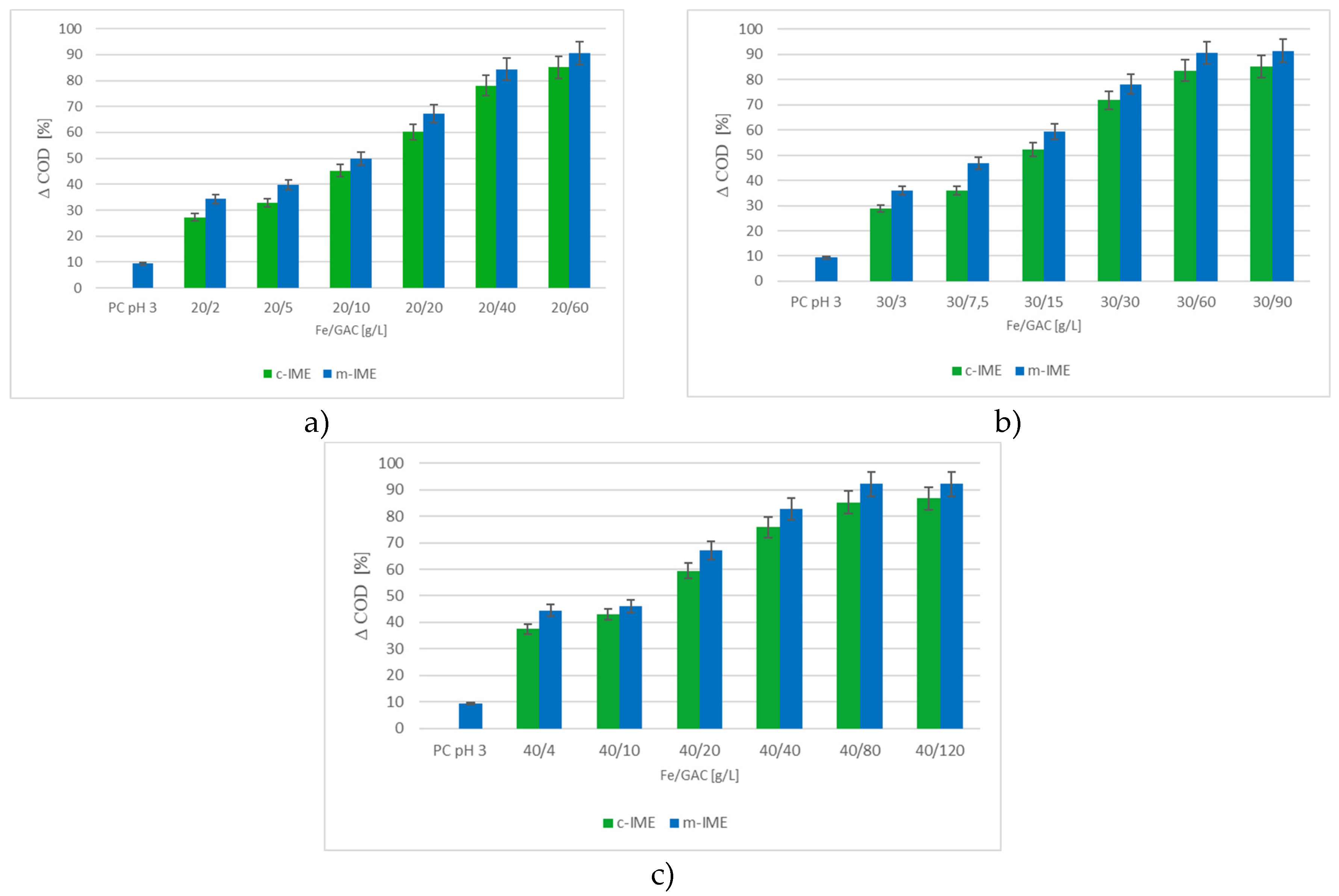

3.2.2. Efficiency of the m-IME and c-IME Processes

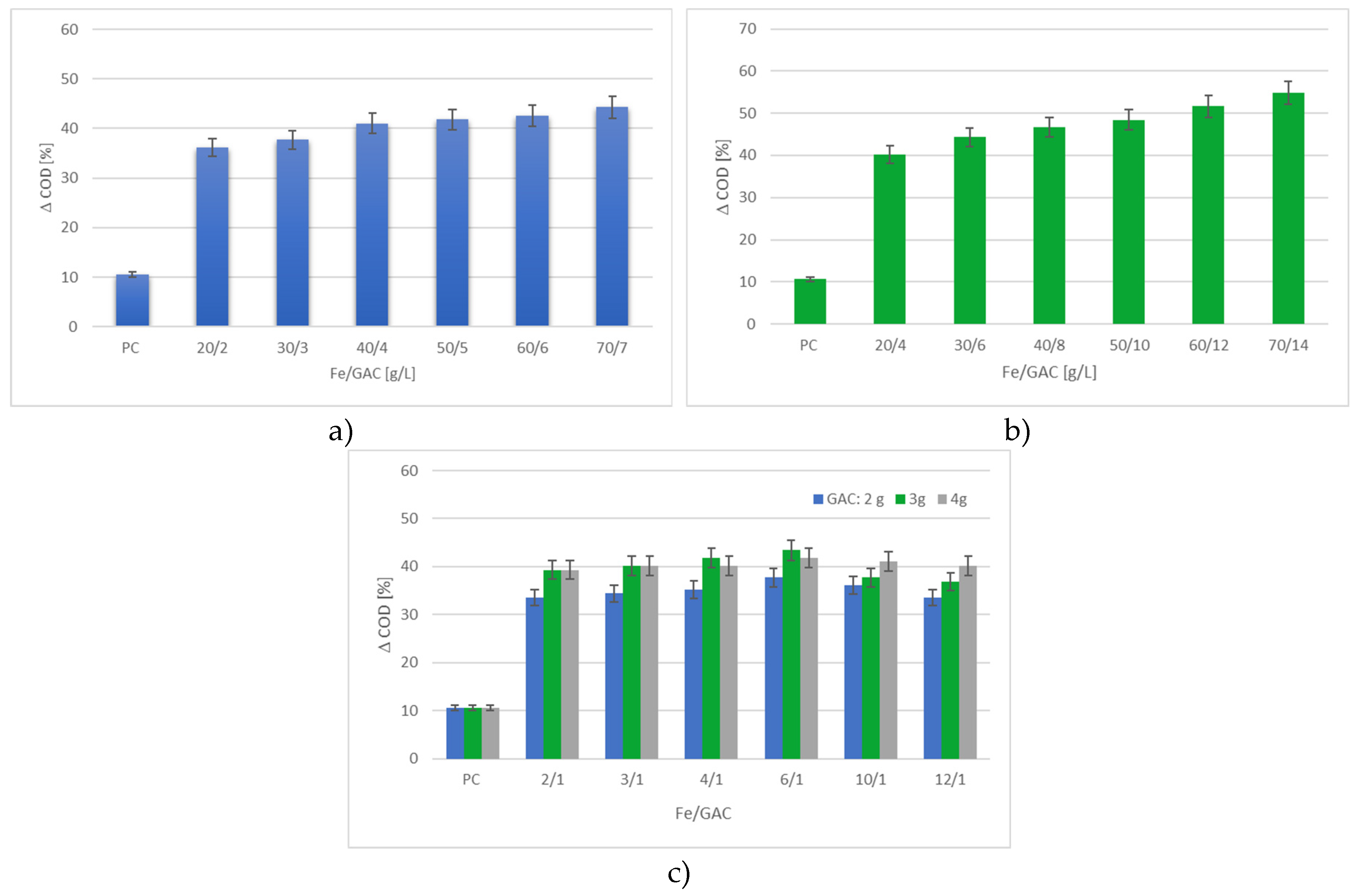

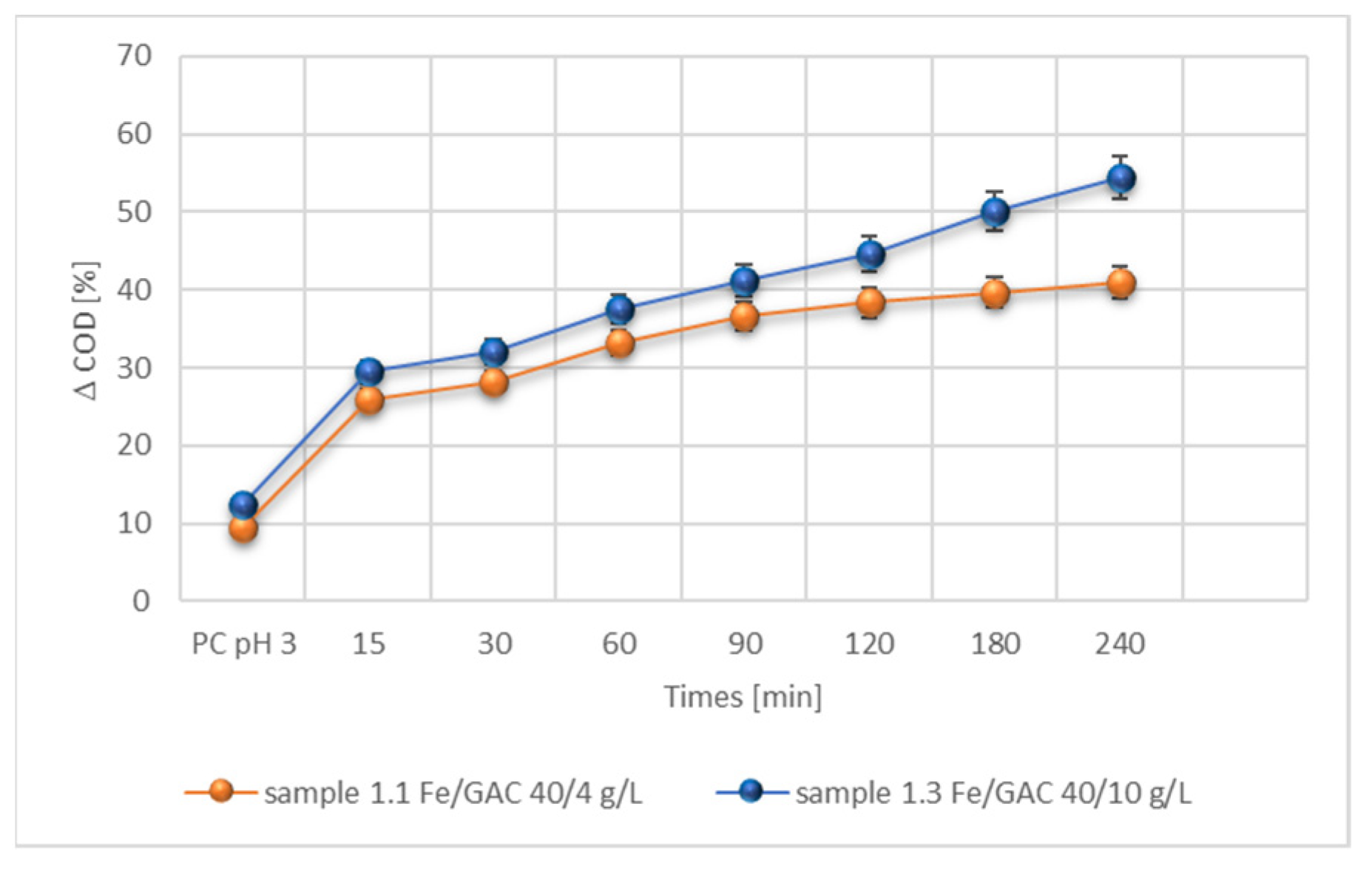

3.2.3. Effects of Fe/GAC Doses

3.2.4. Effect of Time of the Process

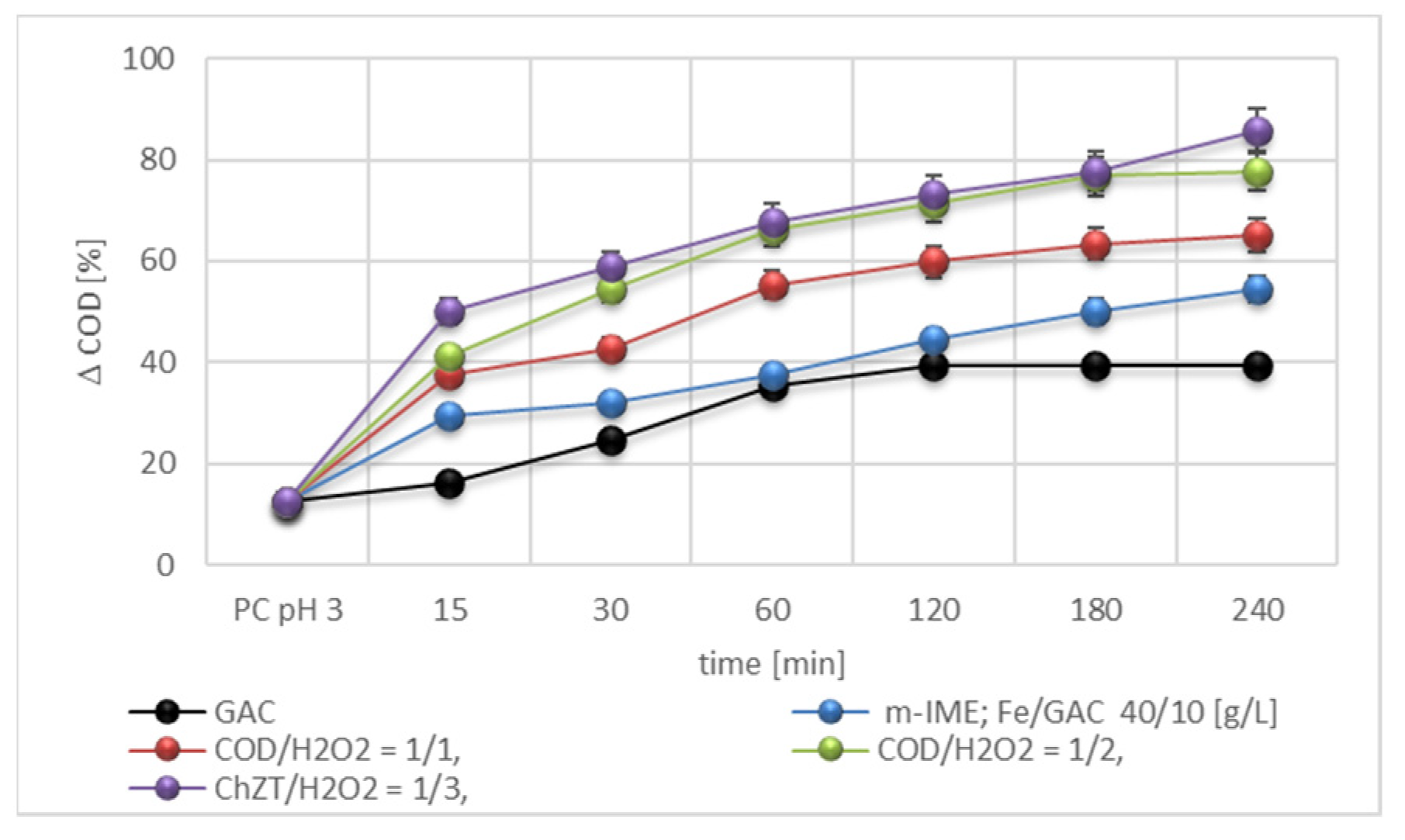

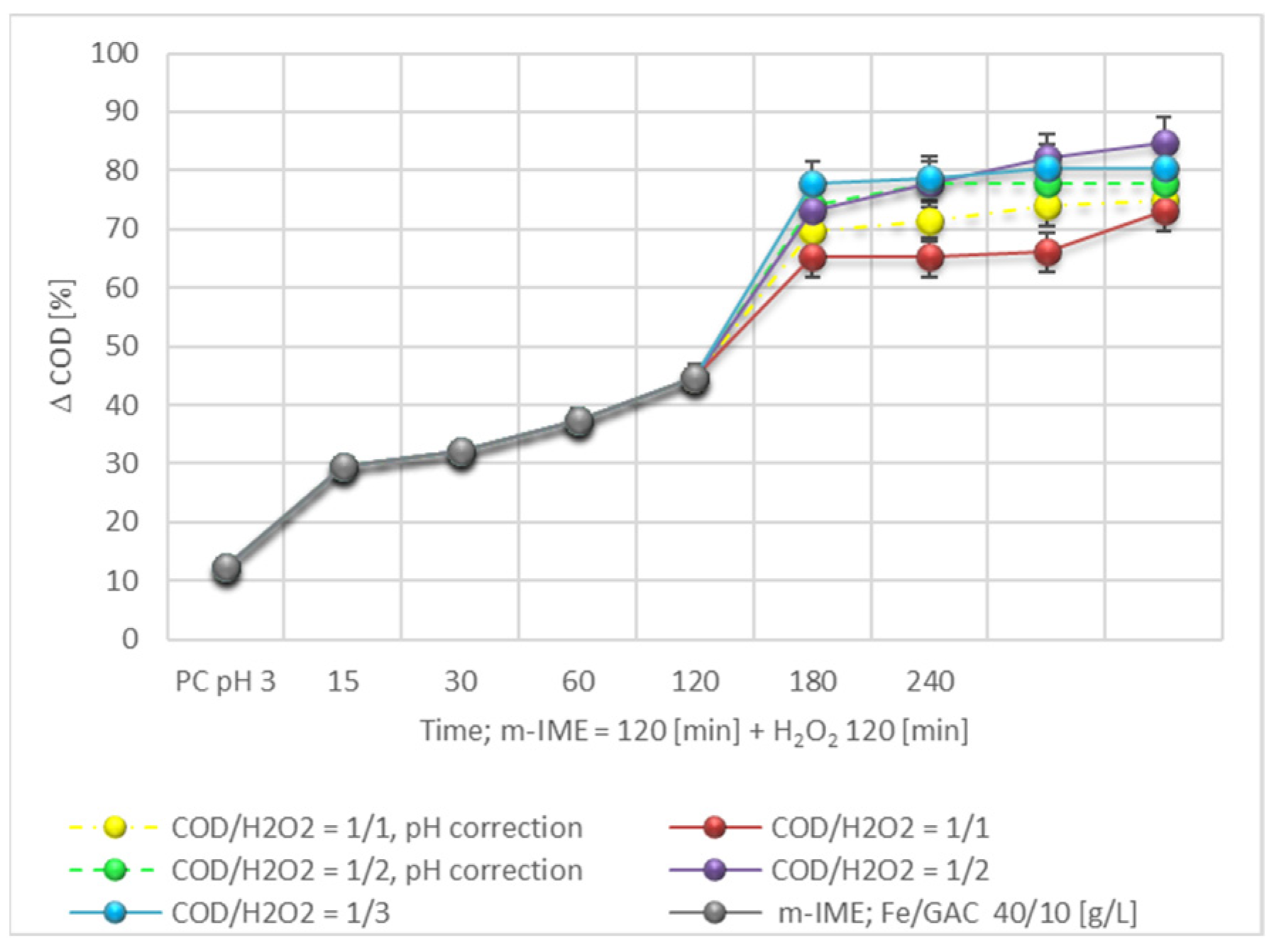

3.3. Hybrid Process m-IME/H2O2

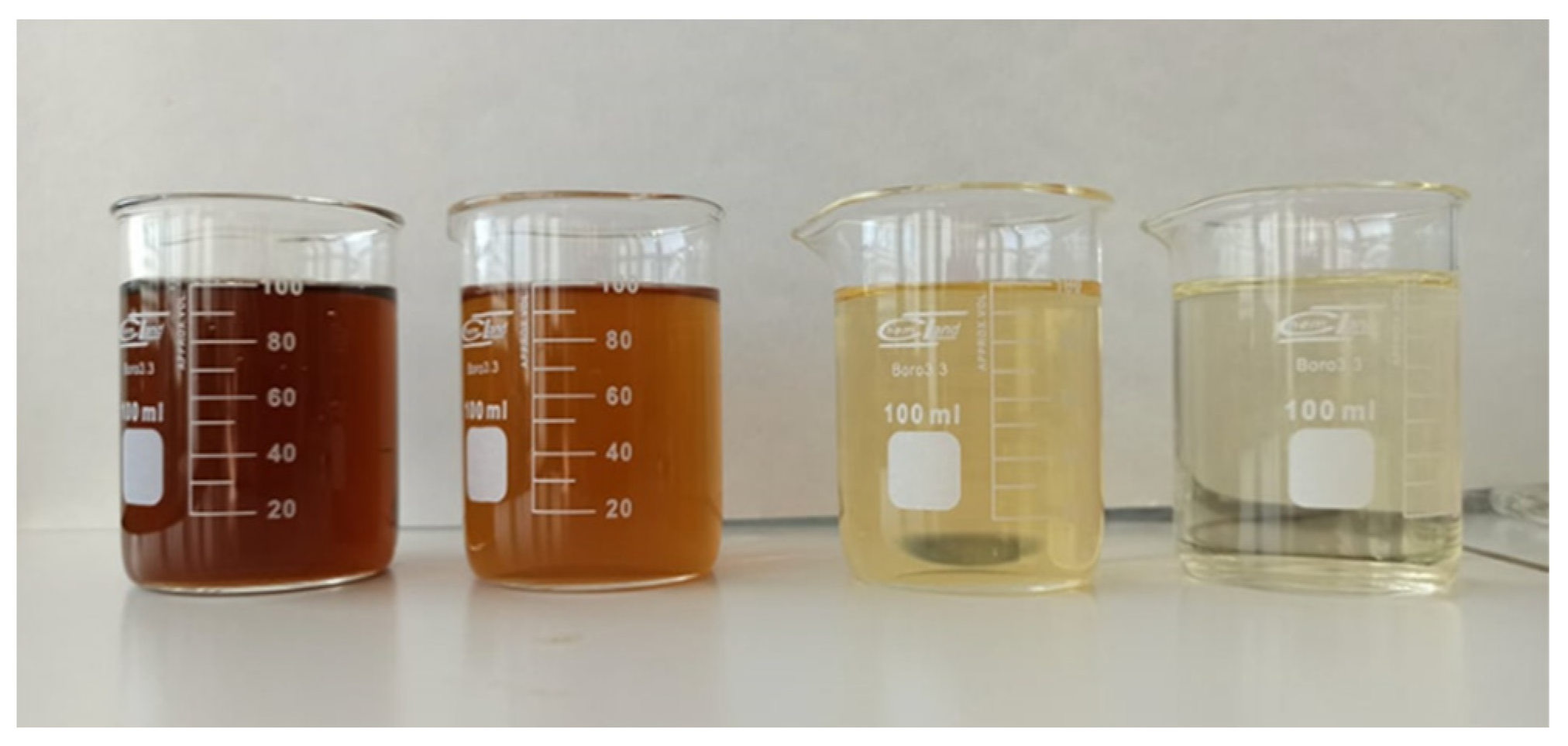

3.4. Characteristics of LL After Subsequent Purification Stages

3.5. Comparison of the Efficiency of IME* and Sorption Processes with a Use of GAC Soaked in LL

| Sample 1.4, COD 1715 mg O2/L | ||

| GAC saturated in raw LL pH 7,8 | GAC saturated in LL after PC pH 3 (COD after PC 1438 mgO2/L) | |

| c-IME* Fe/GAC 40/8 g/L, 60 min | ||

| COD [mg O2/L] | 1144 | 1078 |

| D COD total. [%] | 33.3 | 37.1 |

| Sorption in acidified LL pH 3, time 60 min | ||

| COD [mg O2/L] | 1340 | 1405 |

| D COD total. [%] | 21.9 | 18.1 |

| m-IME* Fe/GAC 40/8 g/L, 60 min, D COD after PC 16,2% | ||

| COD [mg O2/L] | 1062 | 1013 |

| D COD [%] | 26.1 | 29.5 |

| D COD total. [%] | 38.1 | 40.9 |

| Sorption in LL after PC at pH 3, time 60 min | ||

| COD [mg O2/L] | 1177 | 1422 |

| D COD [%] | 18.7 | 1.1 |

| D COD total. [%] | 31.4 | 17.1 |

|

IME (GAC whitout preliminary saturation) | ||

| c-IME | m-IME | |

| COD [mg O2/L] | 947.7 | 817.0 |

| D COD [%] | Not applicable | 43,2 |

| D COD total. [%] | 44.7 | 52.4 |

|

Sorption in LL after PC at pH 3 (GAC whitout preliminary saturation) | ||

| COD [mg O2/L] | 1078 | 1045 |

| D COD [%] | Not applicable | 34.6 |

| D COD total. [%] | 37.1 | 39.0 |

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IME | Internal Microelectrolysis |

| m-IME | Modified internal microelectrolysis |

| c-IME | Classic internal microelectrolysis |

| AOP’s | Advanced oxidation process |

| COD | Chemical oxygen demand |

| BOD | Biological oxygen demand |

| TOC | Total organic carbon |

| LL | Landfill leachate |

| PC | Preliminary coagulation |

| HS | Humic substances |

| SUVA | Specific UV Absorbance |

| AC | Activated carbon |

| GAC | Granular activated carbon |

| CNC | Computer Numerical Control |

| ZVI | Zero valent iron |

References

- Zang, H.; Xiang, L.; Zhang, D.; Qing, H. Treatment of landfill leachate by internal microelectrolysis and sequent Fenton process. Desalination and Water Treatment 2012, 47, 243–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, D.; Xu, X.; Ch, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jia, J. Treatment of mature landfill leachate by a continuous modular internal micro-electrolysis Fenton reactor. Research on Chemical Intermediates 2012, 39, 2763–2776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ying, D.; Peng, J.; Xu, X.; Li, K.; Wang, Y.; Jia, J. Treatment of mature landfill leachate by internal micro-electrolysis integrated with coagulation: a comparative study on a novel sequencing batch reactor based on zero valent iron. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2012, 229–230, 426–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ying, D.; Xu, X.; Li, K.; Wang, Y.; Jia, J. Design of a novel sequencing batch internal micro-electrolysis reactor for treating mature landfill leachate. Chemical Engineering Research and Design 2012, 90, 2278–2286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yang, Q.; Wang, D.; Li, X.; Zeng, G.; Li, Z.; Deng, Y.; Liu, J.; Yi, K. Advanced landfill leachate treatment using iron-carbon microelectrolysis- Fenton process: Process optimization and column experiments. Journal of Hazardous Materials 2016, 318, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Ma, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, Q.; Zhou, Z.; Ren, Z. Degradation of organic pollutants in near-neutral pH solution by Fe-C microelectrolysis system. Chemical Engineering Journal 2017, 315, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Jia, Y.; Qin, Y.; Zhou, M.; Sun, J. Iron-carbon microelectrolysis for wastewater remediation: Preparation, performance and interaction mechanisms. Chemosphere 2021, 278, 130483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdizadeh, H.; Malakootian, M. Optimization of ciprofloxacin removal from aqueous solutions by a novel semi-fluid Fe/charcoal micro-electrolysis reactor using response surface methodology. Process Saf. Environ. Protect. 2019, 123, 299–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Chai, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Shu, Y. Degradation of organic wastewater containing Cu-EDTA by Fe-C micro-electrolysis. Trans. Nonferrous Metals Soc. China 2012, 22, 983–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Lin, Y.; Liu, L. Treatment of dinitrodiazophenol production wastewater by Fe/C and Fe/Cu internal electrolysis and the COD removal kinetics. Journal of the Taiwan Institute of Chemical Engineers 2016, 58, 148–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Peng, P.; Lu, T. Treatment of naphthalene derivatives with iron-carbon micro-electrolysis. Trans. Nonferrous Metals Soc. China 2006, 16, 1442–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Liao, L.; Lv, G.; Qin, F.; He, Y.; Wang, X. Micro-electrolysis of Cr (VI) in the nanoscale zero-valent iron loaded activated carbon. J. Hazard Mater 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.; Xu, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, D.; Chen, W. Effects of different scrap iron as anode in Fe-C micro-electrolysis system for textile wastewater degradation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 26869–26882, 254–255, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malakootian, M.; Mahdizadeh, H.; Khavari, M.; Nasiri, A.; Gharaghani, M.A.; Khatami, M.; Sahle-Demessie, E.; Varma, R.S. Efficiency of novel Fe/charcoal/ultrasonic micro-electrolysis strategy in the removal of Acid Red 18 from aqueous solutions. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 103553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Lv, P.; Shen, Y.; Wang, J.; Fan, J. Identification of degradation products of ionic liquids in an ultrasound assisted zero-valent iron activated carbon micro-electrolysis system and their degradation mechanism. Water Res. 2013, 47, 3514–3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Shen, Y.; Lv, P.; Wang, J.; Fan, J. Degradation of 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride ionic liquid by ultrasound and zero-valent iron/activated carbon. Separation and Purification Technology 2013, 104, 208–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, X.; Liu, M.; Zeng, Q.; Ding, Y. Degradation and decolorization of reactive red X-3B aqueous solution by ozone integrated with internal micro-electrolysis and zero-valent iron/activated carbon. Separ. Purif. Technol. 2010, 104, 208–213, Separ. Purif. Technol. 74, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Dong, W.; Sun, F.; Yang, W.; Dong, J. Degradation efficiency and mechanism of azo dye RR2 by a novel ozone aerated internal micro-electrolysis filter. J. Hazard Mater. 2014, 276, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Yi, J.; Chen, L.; Lan, T.; Dai, J. Pretreatment of printing and dyeing wastewater by Fe/C micro-electrolysis combined with H2O2 process. Water Sci. Technol. 2018, 707–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Yu, L.; Luo, S.; Jiao, W.; Liu, Y. Degradation of nitrobenzene wastewater via iron/carbon micro-electrolysis enhanced by ultrasound coupled with hydrogen peroxide. China Pet. Process. Petrochem. Technol. 2017, 19, 72–81. [Google Scholar]

- An, L.; Xiao, P. Zero-valent iron/activated carbon microelectrolysis to activate peroxydisulfate for efficient degradation of chlortetracycline in aqueous solution. RSC Adv. 2020, 10, 19401–19409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Xi, B.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, F.; Han, X.; Gao, P.; Wan, S.; Jiang, Y.; Yang, Y. a comparative study on the treatment of 2,4-dinitrotoluene contaminated groundwater in the combined system: efficiencies, intermediates and mechanisms. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 735, 139161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, L.; Zhang, G.; Meng, Q.; Xu, L.; Lv, B. Enhanced MBR by internal microelectrolysis for degradation of anthraquinone dye wastewater. Chem. Eng. J. 2012, 210, 575–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, W.; Li, D.; Li, J.; Hu, Q.; Deng, S. Nitrate removal and microbial analysis by combined micro-electrolysis and autotrophic denitrification. Bioresour. Technol. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Jin, M.; Zhou, X.; Chen, W.; Lu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Shao, X. Enhanced removal mechanism of iron carbon micro-electrolysis constructed wetland on C, N, and P in salty permitted effluent of wastewater. 2019, 649, 21–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Cheng, Y.; Zhang, T.; Ji, F.; Xu, X. Treatment of pharmaceutical wastewater using interior micro-electrolysis/Fenton oxidation-coagulation and biological degradation. Chemosphere 2016, 152, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Wu, Y. Application of coupled zero-valent iron/biochar system for degradation of chlorobenzene-contaminated groundwater. Water Science and Technology 2017, 75, 571–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Chen, J.; Xie, Z.; Xu, X. Treatment of nanofiltration concentrates of mature landfill leachate by a coupled process of coagulation and internal micro-electrolysis adding hydrogen peroxide. Environmental Technology 2014, 36, 1001–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.; Pang, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, F.; Liao, X.; Lei, M.; Song, Y. Landfill leachate treatment by coagulation/flocculation combined with microelectrolysis Fenton processes. Environmental Technology 2018, 40, 1862–1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Cheng, X.G.; Yin, P.H.; Lu, G.; Suo, J.C. The Performance of Microelectrolysis in Improving the Biodegradability Landfill Leachate. Applied Mechanics and Materials 2013, 448–453, 1399–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Chen, S.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, C.; Liu, J.; Luo, J.; Song, G.; Qian, G.; Song, L.; Xia, M. Simultaneous removal of organic matter and nitrate from bio-treated leachate via iron-carbon internal micro-electrolysis. Royal Society of Chemistry Adv. 2015, 5, 68356–68360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Li, W.; Li, Y.; Mosa, A.; Wang, H.; Jin, Y. Treatment of landfill leachate RO concentration by Iron–carbon micro–electrolysis (ICME) coupled with H2O2 with emphasis on convex optimization method. Environmental Pollutants and Bioavailability 2019, 31, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Xua, Y.; Zhoua, S.; Liub, J.M.; Cheng, Y.; Fu, G.Y.; He, X.S. Field-scale performance of microelectrolysis-Fenton oxidation process combined with biological degradation and coagulative precipitation for landfill leachate treatment. In Proceedings of the 2019 4th International Conference on Advances in Energy and Environment Research (ICAEER 2019); Environmental Protection, Pollution and Treatment. 2019; Volume 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucharska, M.A.; Mirehbar, S.K.; Ładyńska, J.A. Novel combined IME-O3/OH*/H2O2 process in application for mature landfill leachate treatment. Journal of Water Process Engineering 2022, 45, 102441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzysztoszek, A.; Naumczyk, J. Landfill Leachate Treatment by Fenton, Photo-Fenton Processes and their Modification. Journal of Advanced Oxidation Technologies 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogacki, J.; Marcinowski, P.; El-Khozondar, B. Treatment of Landfill Leachates with Combined Acidification/Coagulation and the Fe0/H2O2 Process. Water 2019, 11, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joanna Ładyńska. Stabilized municipal landfill leachate treatment by the internal microelectrolysis proces. Doctoral dissertation, Warsaw Uniwersity of Technology, Warsaw, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, W.; Zhao, H.; Gao, J.; Meng, X.; Wu, S.; Qin, Y. Influence of a reagents addition strategy on the Fenton oxidation of rhodamine B: control of the competitive reaction of ·OH. RSC Advances 2016, 6, 108791–108800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krupińska, I. Problemy związane z występowaniem substancji humusowych w wodach podziemnych. Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytet Zielonogórski, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzyk, A.; Papciak, D. Wpływ właściwości związków organicznych na efektywność procesów uzdatniania wody-podstawy teoretyczne. Czasopismo Inżynierii Lądowej, Środowiska i Architektury, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material/symbol | GAC Gryfskand | Grey cast iron |

|---|---|---|

| Trade name | WD extra, 4H | EN-GJL 200 |

| Form | granulated | filings |

| Size | 2-0,75 mm | 2-1 mm |

| Bulk density | 472 g/L | 7,15 kg/L |

| Other |

|

chemical composition (approximate % by weight):

|

| Sample nr | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COD [mg O2/L] | 1073 | 1045 | 1092 | 1715 |

| pH | 7,81 | 7,31 | 8,20 | 7,80 |

| Conductivity [mS/cm] | 11,8 | 11,6 | 8,19 | 9,8 |

| Ntotal [g/L] | 298 | 236 | 343 | 432 |

| Cl- [mg/L] | 420 | 390 | 370 | 412 |

| TOC [mg/L] | 376 | 362 | 381 | 543 |

| BOD5 [mg O2/L] | 92 | 104 | 131 | 190 |

| BOD5/COD | 0,08 | 0,10 | 0,12 | 0,11 |

| N-NH4 [g/L] | 268 | 197 | 294 | 387 |

| Absorbance 254 nm | 11,80 | 11,75 | 11,82 | 11,92 |

| SUVA [m2/gC] | 0,0314 | 0,0324 | 0,0309 | 0,0219 |

| Sample 1.4 | Raw LL | PC pH 3 | m-IME 120 min | m-IME 120 min/H2O2 60 min (H2O2/COD 2/1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COD [mg O2/L] | 1092 | 955 | 402 | 170 |

| D COD [%] | 12,5 | 44,6 | 82,1 | |

| pH | 8,2 | 3,0 | 6,2 | 9,0 |

| Conductivity [mS/cm] | 8,19 | 9,71 | 8,96 | 9,81 |

| Ntotal [g/dm3] | 343 | 336 | 242 | 198 |

| TOC [mg/dm3] | 381 | 326 | 130 | 88 |

| BOD5 [mg O2/dm3] | 131 | - | 129 | 78 |

| BOD5/COD | 0,12 | - | 0,32 | 0,39 |

| Absorbance 254 [nm] | 11,82 | 8,96 | 0,562 | 0,103 |

| SUVA [m2/gC] | 0,0309 | 0,0275 | 0,0042 | 0,0011 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).