Submitted:

10 December 2025

Posted:

11 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Observations

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. The Morpho-Kinematic Model of NGC 2371

4.2. The Brilliant Knots in [N ii]

4.3. The Origin of NGC 2371

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Additional PV Diagrams

Appendix B. Modelling Structures in ShapeX

- In most cases, the process begins by defining a sphere whose polar axis is initially oriented along the N–S direction.

- The sphere is then rotated so that its polar axis attains a position angle (PA) consistent with the orientation of the main axis of the structure to be modelled.

- At this stage, the modifiers SIZE or SQUEEZE are applied to transform the sphere into an ellipsoid or even into a bipolar structure. In some cases, only a section of these surfaces is employed to reproduce the observed morphology. For example, an ellipsoid may be used to represent a cap, but this does not imply the existence of the entire ellipsoid, only the region that matches the observed feature. This approach allows us to estimate both the distance from the geometric centre to the cap and to assign a velocity law consistent with its expansion.

- Once the synthetic structure resembles the morphology seen in direct imaging, a velocity law and an inclination angle with respect to the line of sight are introduced. These parameters are adjusted iteratively, along with the size and orientation, until the model reproduces the relevant portion of the PV diagram while maintaining consistency with the direct image.

- The same procedure is then repeated for each additional structure. In practice, it is often more effective to begin with a single PV diagram and, once a convincing fit is obtained, to test whether it also reproduces other PV diagrams. This process is continued until a robust final model is reached, in which all structures reproduce satisfactorily both the morphological and kinematic characteristics observed in the images and spectra.

- Using ShapeX as an analysis tool is also very powerful. For example, once an elliptical or bipolar structure has been defined and an inclination angle and velocity law have been assigned, the model can be rotated to view the nebula pole-on, and synthetic spectra can be extracted to directly measure the deprojected polar velocity. Likewise, by rotating the model so that the main axis is perpendicular to the line of sight, the deprojected equatorial expansion velocity can also be measured.

Appendix C. Calculations

References

- Ramstedt, S.; Vlemmings, W. H. T.; Doan, L.; et al. 2020, DEATHSTAR: Nearby AGB stars with the Atacama Compact Array I. CO envelope sizes and asymmetries: A new hope for accurate mass-loss-rate estimates, A&A, 640, A133. [CrossRef]

- Scicluna, P.; Kemper, F.; McDonald, I.; et al. 2022, The Nearby Evolved Stars Survey II: Constructing a volume-limited sample and first results from the JCMT, MNRAS, 512, 1091. [CrossRef]

- Kwok, S. 2000, The Origin and Evolution of Planetary Nebulae, Cambridge Astrophysics Series, Vol. 33, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- De Marco, O. 2009, The Origin and Shaping of Planetary Nebulae: Putting the Binary Hypothesis to the Test, PASP, 121, 316. [CrossRef]

- Sahai, R.; Morris, M. R.; Villar, G. G. 2011, Young Planetary Nebulae: Hubble Space Telescope Imaging and a New Morphological Classification System, AJ, 141, 134. [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, N.; Justham, S.; Chen, X.; et al. 2013, Common envelope evolution: where we stand and how we can move forward, A&AR, 21, 59. [CrossRef]

- Chamandy, L.; Blackman, E. G.; Frank, A.; et al. 2020, Common envelope evolution on the asymptotic giant branch: unbinding within a decade, MNRAS, 495, 4028. [CrossRef]

- García-Segura, G.; Taam, R. E.; Ricker, P. M. 2022, Common-envelope shaping of planetary nebulae IV: From protoplanetary to planetary nebula, MNRAS, 517, 3822. [CrossRef]

- López-Cámara, D.; De Colle, F.; Moreno Méndez, E.; et al. 2022, Jets in common envelopes: a low-mass main-sequence star in a red giant, MNRAS, 513, 3634. [CrossRef]

- Ondratschek, P. A.; Röpke, F. K.; Schneider, F. R. N.; et al. 2022, Single-degenerate Type Ia supernovae from common envelope evolution, A&A, 660, L8. [CrossRef]

- Rechy-García, J. S.; Toalá, J. A.; Guerrero, M. A.; et al. 2022, The common envelope origins of the fast jet in the planetary nebula M 3–38, ApJL, 933, L24. [CrossRef]

- Henney, W. J.; López, J. A.; García-Díaz, M. T.; et al. 2021, Five axes of the Turtle: symmetry and asymmetry in NGC 6210, MNRAS, 502, 1070. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-González, J. B.; Toalá, J. A.; Sabin, L.; et al. 2022, Adjusting the bow-tie: a morpho-kinematic study of NGC 40, MNRAS, 515, 1557. [CrossRef]

- Pottasch, S. R.; Gathier, R.; Gilra, D. P.; et al. 1981, The ultraviolet spectrum of the planetary nebula NGC 2371 and its exciting star, A&A, 102, 237.

- Kaler, J. B.; Stanghellini, L.; Shaw, R. A. 1993, NGC 2371: a high-excitation planetary nebula with an O VI nucleus, A&A, 279, 529.

- Ramos-Larios, G.; Phillips, J. P. 2012, The structure of the planetary nebula NGC 2371 in the visible and mid-infrared, MNRAS, 425, 1091. [CrossRef]

- Hajduk, M.; Haverkorn, M.; Shimwell, T.; et al. 2021, Evidence for cold plasma in planetary nebulae from LOFAR observations, ApJ, 919, 121. [CrossRef]

- Bailer-Jones, C. A. L., Rybizki, J., Fouesneau, M., et al. 2021, Estimating Distances from Parallaxes. V. Geometric and Photogeometric Distances to 1.47 Billion Stars in Gaia Early Data Release 3, AJ, 161, 3, 147. [CrossRef]

- Sabbadin, F.; Bianchini, A.; Hamzaoglu, E. 1982, Spatial–kinematical models for planetary nebulae: NGC 2371–2, A&AS, 50, 523.

- Gómez-González, V. M. A.; Toalá, J. A.; Guerrero, M. A.; et al. 2020, Planetary nebulae with Wolf–Rayet-type central stars I: The case of the high-excitation NGC 2371, MNRAS, 496, 959. [CrossRef]

- Olguín, L.; Vázquez, R.; Cook, R.; et al. 2002, Physical Conditions and Chemical Structure of the PNe NGC 2440 and NGC 2371-72, Revista Mexicana de Astronomía y Astrofísica Conference Series, 12, 172.

- Ayala, S.; Vázquez, R.; Miranda, L. F.; et al. 2005, NGC 2371: Mapping its physical and kinematic structure, in Planetary Nebulae as Astronomical Tools, AIP Conf. Proc., 804, 95. [CrossRef]

- Meaburn, J.; López, J. A.; Gutiérrez, L.; et al. 2003, The Manchester Echelle Spectrometer at the San Pedro Mártir Observatory (MES–SPM), RevMexA&A, 39, 185.

- Tody, D. 1986, The IRAF Data Reduction and Analysis System, Proc. SPIE, 627, 733. [CrossRef]

- Tody, D. 1993, IRAF in the Nineties, in Astronomical Data Analysis Software and Systems II, ASP Conf. Ser., 52, 173.

- Fitzpatrick, M.; Placco, V.; Bolton, A.; et al. 2025, Modernizing IRAF to Support Gemini Data Reduction, ASPCS, 541, 461. [CrossRef]

- Steffen, W.; Koning, N.; Wenger, S.; Morisset, C.; Magnor, M. 2011, Shape: A 3D modeling tool for astrophysics, IEEE Trans. Vis. Comput. Graphics, 17, 454. [CrossRef]

- Guillén, P. F.; Vázquez, R.; Miranda, L. F.; Zavala, S.; Contreras, M. E.; Ayala, S.; Ortiz-Ambriz, A. 2013, Multiple outflows in the planetary nebula NGC 6058, MNRAS, 432, 2676. [CrossRef]

- Schoenberner, D. 1979, Asymptotic giant branch evolution with steady mass loss, A&A, 79, 108.

- Iben, I., Kaler, J. B., Truran, J. W., et al. 1983, On the evolution of those nuclei of planetary nebulae that experiencea final helium shell flash, ApJ, 264, 605. [CrossRef]

- Toalá, J. A., Lora, V., Montoro-Molina, B., et al. 2021, Formation and fate of the born-again planetary nebula HuBi 1, MNRAS, 505, 3, 3883. [CrossRef]

- Fang, X., Guerrero, M. A., Marquez-Lugo, R. A., et al. 2014, Expansion of Hydrogen-poor Knots in the Born-again Planetary Nebulae A30 and A78, ApJ, 797, 2, 100. [CrossRef]

- Zou, Y.; Frank, A.; Chen, Z.; Reichardt, T.; De Marco, O.; Blackman, E. G.; Nordhaus, J.; et al. 2020, Bipolar planetary nebulae from outflow collimation by common envelope evolution, MNRAS, 497, 2855. [CrossRef]

- Córsico, A. H.; Althaus, L. G.; Miller Bertolami, M. M.; et al. 2021, White-Dwarf Asteroseismology with the Kepler Space Telescope, Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences, 8, 631132. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira da Rosa, G.; et al. 2022, Kepler and TESS Observations of PG 1159-035, ApJ, 936(2), 187. [CrossRef]

- Jones, D. 2020, Binary Central Stars of Planetary Nebulae, Galaxies, 8, 33. [CrossRef]

- Ramos-Larios, G.; Guerrero, M. A.; Vázquez, R.; Phillips, J. P. 2012, Optical and infrared imaging and spectroscopy of the multiple-shell planetary nebula NGC 6369, MNRAS, 420, 1977. [CrossRef]

- Vázquez, R. 2012, Bubbles and Knots in the Kinematical Structure of the Bipolar Planetary Nebula NGC 2818, ApJ, 751, 116. [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Muñoz, M. A.; Vázquez, R.; Sabin, L.; Olguín, L.; Guillén, P. F.; Zavala, S.; Michel, R. 2023, The origin of the planetary nebula M 1–16: a morpho-kinematic and chemical analysis, A&A, 676, A101. [CrossRef]

- Friederich-Hidalgo, A.; Torres, R. M.; Soto-Badilla, F.; Medina-Leal, C. A.; Gil-Gallegos, S. S.; Íñiguez-Garín, E.; Vázquez, R. 2025, Tracing the ISM–PN interaction: a morphokinematic study of Abell 71, MNRAS, 541, 3932. [CrossRef]

| Run | Date | Slit | PA | Filter | Exposure time (s) | Notesa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 2002 Jan 7 | A1 | 55° | [O iii] | 900 | 40″ to NW |

| A2 | 55° | [O iii] | 600 | CS | ||

| A3 | 55° | [O iii] | 900 | 60″ to SE | ||

| B | 2003 Feb 23 | B1 | 90° | [O iii] | 900 | 13″ to S |

| B2 | 90° | [O iii] | 900 | CS | ||

| B3 | 90° | [O iii] | 900 | 19″ to N | ||

| B4 | 90° | [O iii] | 900 | 30″ to N | ||

| B5 | 90° | [O iii] | 900 | 32″ to S | ||

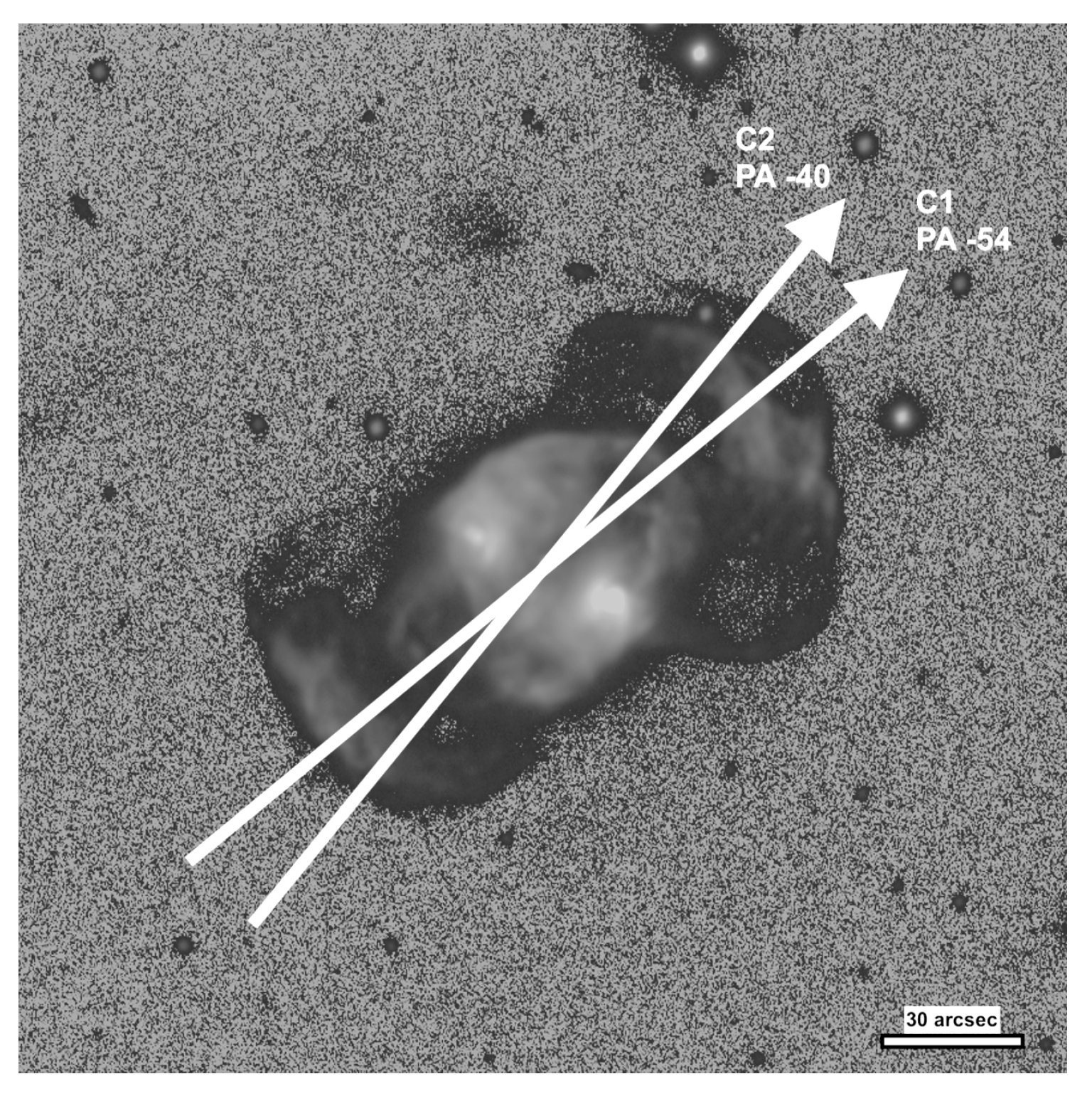

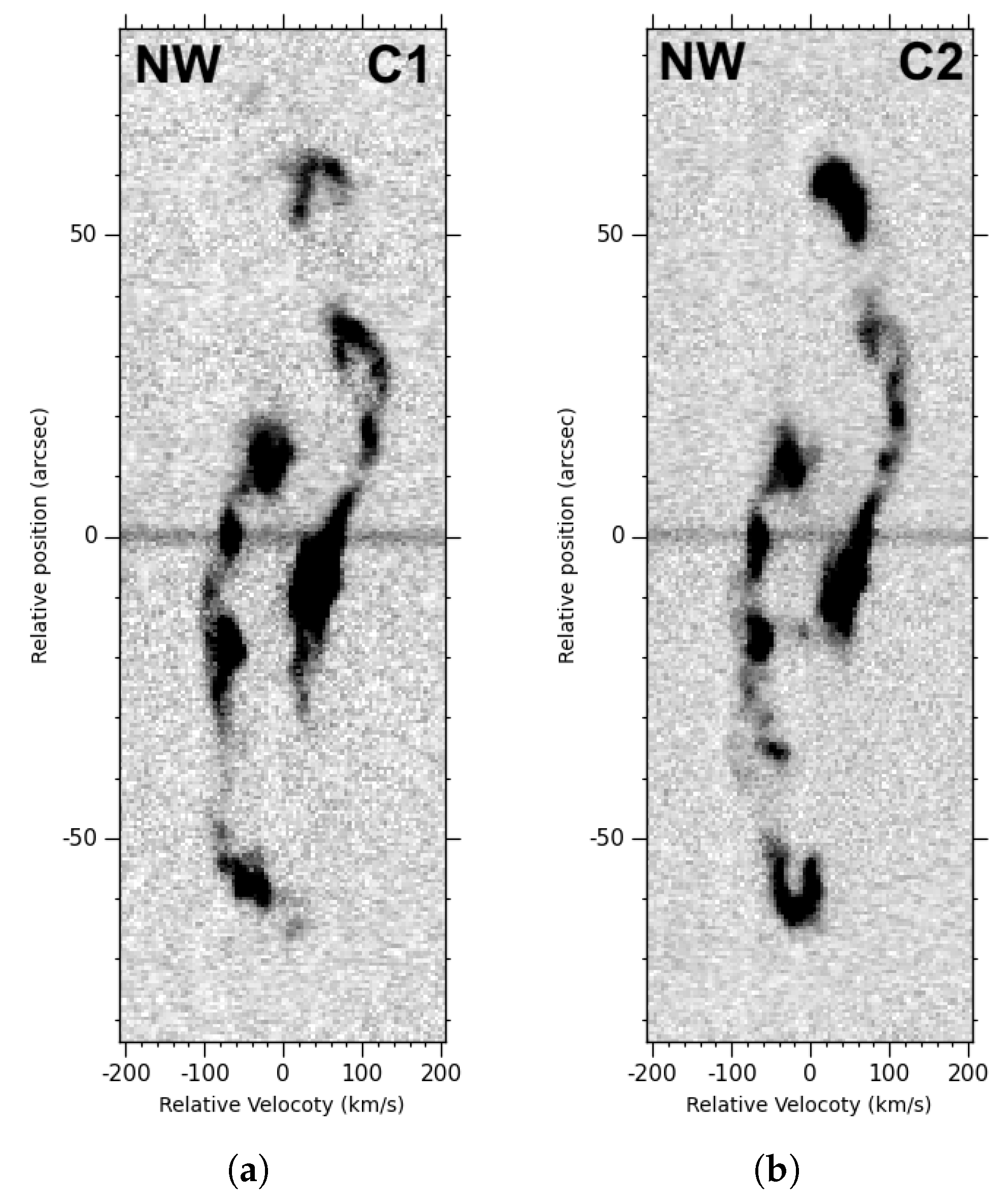

| C | 2005 Feb 25 | C1 | ° | [O iii] | 1200 | CS |

| C2 | ° | [O iii] | 1200 | CS | ||

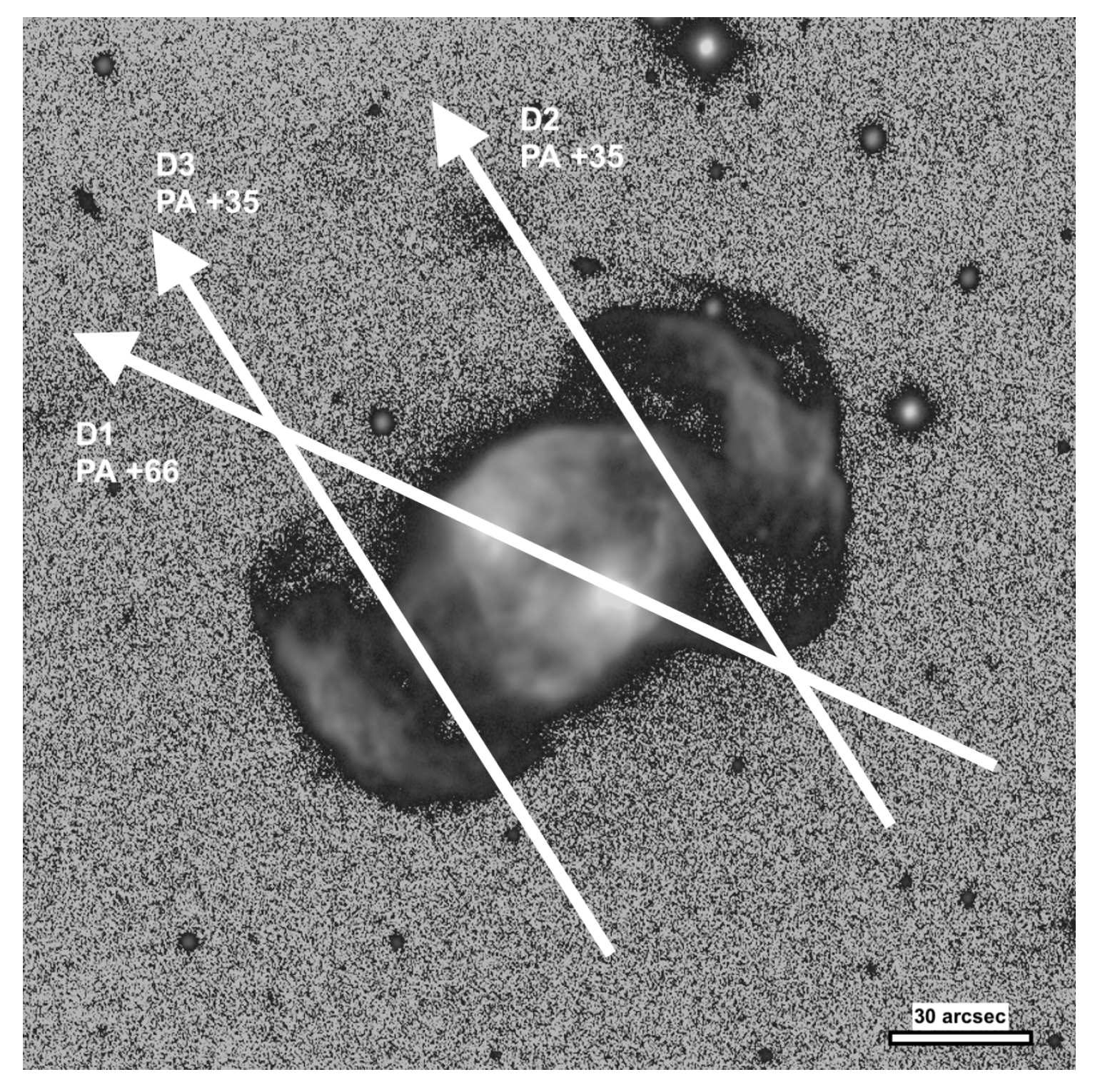

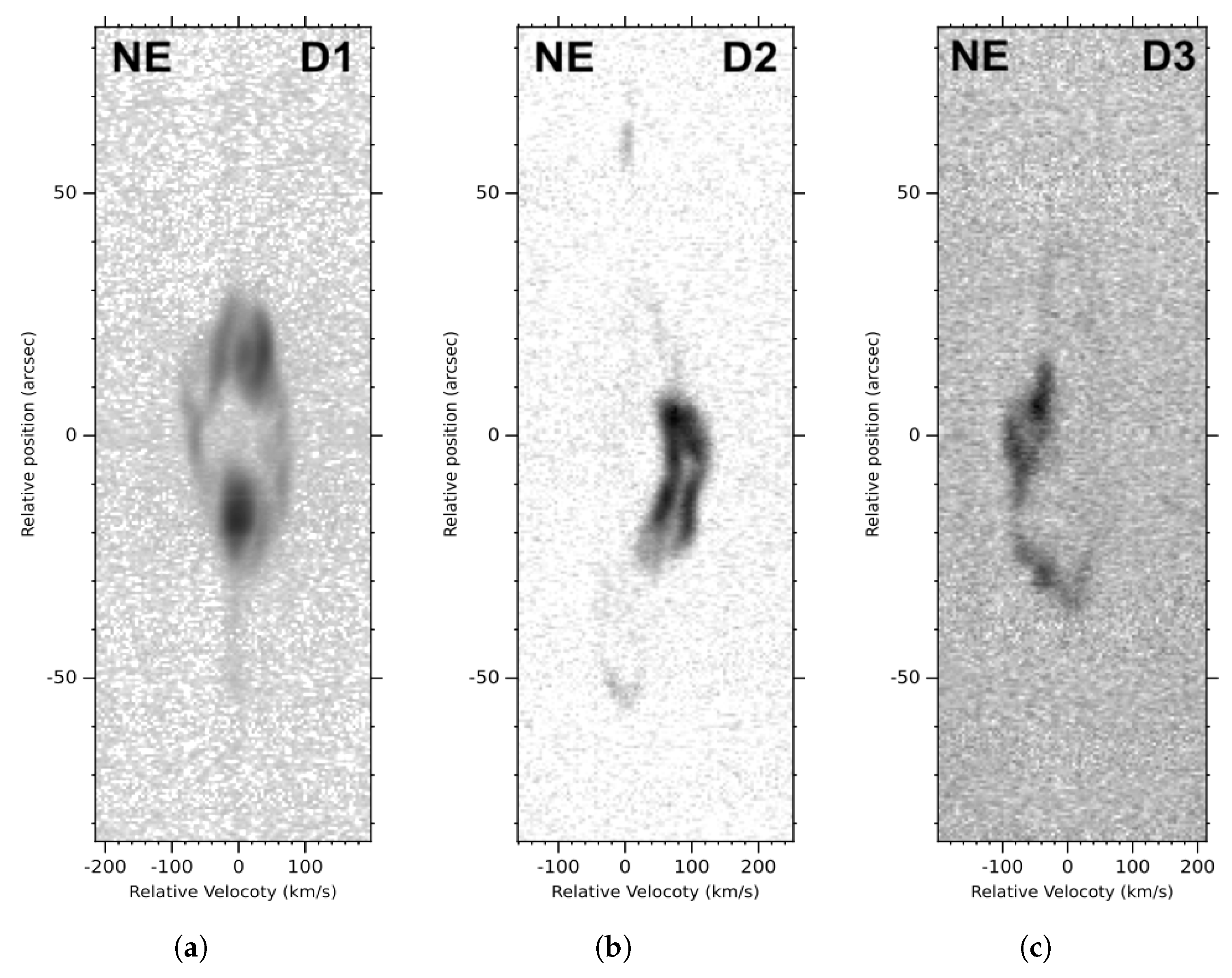

| D | 2005 Dec 13–14 | D1 | 66° | [O iii] | 900 | CS |

| D2 | 35° | [O iii] | 1800 | 33″ to NW | ||

| D3 | 35° | [O iii] | 1800 | 36″ to SE | ||

| E | 2009 Feb 4–6 | E1 | 66° | H+[N ii] | 1800 | Jets |

| E2_1 | ° | H+[N ii] | 900 | CS | ||

| E2_2 | ° | [O iii] | 900 | CS | ||

| E3 | ° | [O iii] | 900 | 17″ to NE | ||

| E4 | ° | [O iii] | 900 | 17″ to SW | ||

| F | 2016 Feb 20 | F1 | 93° | [O iii] | 1800 | CS |

| F2 | 65° | H+[N ii] | 1800 | CS | ||

| F3_1 | 37° | [O iii] | 1800 | CS | ||

| F3_2 | 37° | H+[N ii] | 1800 | CS | ||

| F4 | ° | [O iii] | 1800 | CS | ||

| G | 2016 Feb 21 | G1 | 37° | [O iii] | 1800 | 50″ to SE |

| G2 | 37° | [O iii] | 1800 | 28″ to SE | ||

| G3 | 37° | [O iii] | 1800 | 28″ to NW | ||

| G4 | 37° | [O iii] | 1800 | 50″ to NW |

| Structure | PA | i | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (arcsec) | (arcsec) | (°) | (°) | ( km s−1) | ( km s−1) | ( km s−1 arcsec−1) | (yrs) | |

| Lobes | n/a | n/a | 1.8 | |||||

| Barrel | n/a | 2.5 | ||||||

| NW cap | n/a | n/a | 5.0 | |||||

| SE cap | n/a | n/a | 3.0 | |||||

| E jet | n/a | n/a | 3.6 | |||||

| W jet | n/a | n/a | 1.0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).