Introduction

Insect-mating systems describe the conditions under which males and female gametes are exchanged during reproduction as well as how group interactions structure their mating behaviour (Thornhill & Alcock, 1983). In the broadest sense, mating systems include monogamy, polyandry, polygyny, and polygynandry, which convey the number of times each sex typically mates (Hoffmann et al., 2021; Shuker & Simmons, 2014). However, mating systems are also both plastic and evolutionarily dynamic, since the behaviours that underpin them are traits affected by spatial ecology (Shelly & Whittier, 1993; Silva et al., 2017) and the forces of evolution (Shelly, 2018). Together these act to produce many different reproductive modes and behaviours, even across populations of the same species. Understanding these patterns require more precise models to accurately describe, as well as empirical findings to validate and revise such models.

Consider the lek mating system. First described in the European grouse, Tetrao urogallus (Aves: Galliformes: Phasianidae) by Lloyd (1867), it has since captured the attention of many ecologists, including Darwin who developed his ideas on sexual selection based on the lekking Indian peafowl Pavo cristatus (Aves: Galliformes: Phasianidae). For lekking species, males aggregate at mating sites distinct from the sites where females lay eggs/raise young. Curiously though, these sites offer visiting females no apparent resource other than the opportunity to mate (by contrast, a resource-dependent polygynous species would aggregate near food, water, or refugia). Even more curiously, one of the canonical attributes of leks is that a single or few dominant males capture most of the matings, leading many to speculate how and why subordinate males would continue to form leks. As such, a great deal of ecological and evolutionary theory has been developed to understand how lekking evolves and maintained in populations (Emlen & Oring, 1977), how mate choice is enacted (Beehler & Foster, 1988; J. W. Bradbury & Gibson, 1983), as well as how to distinguish lekking from other similar systems (Höglund & Alatalo, 1995).

Emlen & Oring (1977) explain that the first condition of lek mating is the release of males from parental care, which allows adult males to devote themselves entirely to securing mates (at the cost of female fitness), rather than nest-building, foraging, or predator defence. The mating system which evolves from this conflict is thought to be contingent on spatial ecology. For example, if the distribution of females within the environment is highly patchy, this then selects for a system in which males must guard females or the resources they utilize (e.g., burrows, water, food sources) (Buzatto & Machado, 2008). However, if females are evenly disbursed, then this selects for a mating system in which males need to quickly “scramble” to mate with many females, since they cannot economically defend them from the advances of competitors (Herberstein et al., 2017). In the middle of the continuum between these two extremes lies lekking, in which the optimum strategy for males directly compete with one another for a dominant position within a territory (Alcock, 1990). Females visit these resourceless sites strictly to mate before leaving to lay their eggs elsewhere. One hypothesized driver of this system is that mating displays might be highly conspicuous (Zahavi & Zahavi, 1999), which increases predation pressure on lone adults (Rathore et al., 2023), causing mating to be aggregated for social protection away from the nest (Lima, 2009). As such, lekking is a complex behaviour comprised of several individual elements, these being: (1) lack of parental care, (2) highly male-skewed aggregations, and (3) a territory free of resources that females might use.

As alluded to, disruptions to the spatial ecology of a species can in turn cause shifts in the mating system, and such has been described in many lekking insect species, including wild dragonflies (Odonata) (Emlen & Oring, 1977; Hastings et al., 1994) and mass-reared fruit tephritid flies (Dodson, 1986). No doubt, confinement within industrial colonies represents a significant disruption, causing insects to endure a completely different niche than that of the wild (Price, 2002). However, sustaining viable captive insect populations with high genetic diversity requires a deep understanding of the both the physiological and ecological factors that originally evolved. As such, fieldwork is a key step in validating and enhancing the natural mating behaviours in captive populations (Price, 2002), and is also a vital component for designing habitat that promotes insect welfare (Barrett et al., 2022; Van Huis, 2021).

Take for example the black soldier fly (BSF) Hermetia illucens (L. 1758) (Diptera: Stratiomyidae); this species has recently been domesticated for industrial waste-management (Rhode et al., 2020). Currently, trillions of larvae are reared per annum (Barrett et al., 2022, 2025) in BSF factories throughout the globe, including the tropics (da Silva & Hesselberg, 2020). But despite this, only a single field-based study has been conducted to understand the behaviour of wild black soldier fly (J. K. Tomberlin & Sheppard, 2001), and besides a few other scattered accounts (Booth & Sheppard, 1984; Copello, 1926; James, 1935; Sheppard et al., 2002; Tingle et al., 1975; J. K. Tomberlin et al., 2002), very little is known that can contextualize what occurs in industrial colonies. Moreover, most captive BSF strains share a common genetic provenance (Kaya et al., 2021), despite native/naturalized populations of BSF occurring across ~80% the globe (Nyakeri et al., 2017). As such, there are many global regions where BSF likely live under diverse ecological conditions that can give clues for breeding program optimization. Indeed, a genetic diversity hotspot exists in the American tropics to which BSF are native (Kaya et al., 2021; Sandrock et al., 2021). For these reasons, expanding knowledge of wild black soldier fly behavior, especially in the Neotropics, is particularly important. While laboratory studies can explore solutions to such as outcrossing (Jensen et al., 2025), another path will likely be utilizing resources (i.e., wild-caught flies).

Tomberlin & Sheppard (2001) describe BSF as lekking, but since this is the only primary account, there is a great deal of controversy as to whether the species mating system is indeed lekking. In captivity, successful reproduction has been shown to be possible with only a single pair of BSF and therefore not predicated on the stability of lekking aggregations (Jensen et al., 2025). Other studies complicate the matter further by suggesting that captive black soldier fly adults cannot distinguish between sexes (and may simply attempt to mate with objects they detect within their field of vision) (Giunti et al., 2018; Laudani et al., 2024), suggesting the mating system may be shifting away from lekking (N. B. Lemke et al., 2023). Without a clear picture of what the typical mating system of wild populations is, the answers remain unclear. In mass-reared Tephritidae (Diptera), which lek in the wild, the mating system becomes scramble competition polygyny under: (a) high rearing densities since mates become readily available, and (b) high opportunity costs of maintaining territories (instead of pursuing mates) (Dodson, 1986).

In addition, another open question exists whether black soldier fly adults naturally feed, and whether this feeding might serve to supplement limited nutrient reserves for highly energetic flights. Black soldier fly adults are fully capable of feeding (Barrett et al., 2025; Bruno et al., 2019), and feeding by adults been experimentally shown to increase longevity of 5oth males and females in captivity, as well as increase female fecundity under optimized diets (Barrett et al., 2025; Furman et al., 1959; Klüber et al., 2023; Thinn & Kainoh, 2022). Whether this reflects natural physiology and ecology is unknown, especially since the prevailing thought is that as capital breeders (Stephens et al., 2009), it is the larval stage the primarily accumulates energy reserves (Harjoko et al., 2023). However, feeding has been shown to mediate reproductive success in other lekking flies (Yuval et al., 1998), and indeed it has been hypothesized that black soldier fly adults might be able to use resources such as nectar, pollen, or fruit (van Rijn et al., 2013). By examining the gut contents of captured BSF adults, what, if any, food resources they naturally utilize can be determined. This can then be directly correlated with the composition of their gut microbial communities, since if a diverse range of microbes associated with specific food sources are also present, it would provide strong evidence that adult flies are indeed feeding in the wild.

Moreover, the gut microbiomes of wild-caught adult black soldier flies can also be measured and compared with those of larvae to understand the full life-cycle dynamics of these microbial communities under different niches/evolutionary history. Larval gut microbiomes are well-studied due to their role in bioconversion; however, both captive and wild adult diets and environments differ drastically from the larvae, potentially leading to significant gut microbiome shifts. Interestingly, there have been only a few known publications of adult microbiomes (Tettamanti et al., 2022), however these have been described from controlled laboratory settings. Understanding differences between larval and adult microbiomes can reveal how the microbiome influences adult fly health, reproduction, and interactions with the environment. As such, studying the gut microbiomes of healthy, free-ranging individuals provides a baseline understanding of their natural microbial communities, and will be invaluable for comparing flies reared across different controlled industrial environments, helping to reveal the microbial contributions to the fly's natural fitness and nutrient acquisition. This knowledge may also provide insights into optimizing rearing practices, such as identifying beneficial microbes that persist across life stages and can be manipulated to improve fly production and waste management efficiency.

Hence, the objectives of this study were to document black soldier fly behaviour in the wild within in its native Neotropical range, and test the hypothesis that black soldier fly exhibit lekking using Bradbury’s expanded criteria for lekking species (J. Bradbury et al., 1986). This was achieved by examining the sex ratio and spatial distribution of black soldier fly adults at multiple field sites in Costa Rica. In addition, the gut contents and microbial communities of captured adults were also examined to determine what, if any, food resources they might naturally utilize.

Methods

Permitting Process. Fieldwork was performed in Costa Rica because black soldier flies were previously collected during a study abroad trip in July - August 2022 by NBL and remain part of an insect biodiversity collection at the Texas A&M Soltis Center in Alajuela, Costa Rica. In addition, data collected by community scientists (iNaturalist.com) indicated the black soldier fly was commonly found throughout Costa Rica year-round, with sightings peaking during the month of April (though, this peak may have been due to increased user activity). Industrial projects utilizing BSF had also been reported in Costa Rica (Diener et al., 2011; Studt-Solano & Flores-Mora, 2010), and so it was important to know a priori whether wild-caught flies might be industrially escapees; however, natural selection pressures are apparently high enough to cause a reversion back to the wild-type (C. Sandrock, personal communication in 2023), and Hermetia illucens is morphologically district from its sympatric congeners (Fachin et al., 2021; Fachin & Hauser, 2022; see also iNaturalist records).

Initial project approval (ID 1323) was granted by la Oficina Técnica, Commission National Para La Gestión De La Biodiversidad (National Commission for Biodiversity Management Technical Office) on 14 April 2023. Final resolution and approval for the permit was delivered on 25 May 2023 (R-029-2023-OT-CONAGEBIO), granting permission to research and collect up to 100 black soldier fly samples, Hermetia illucens, their genetic material, and microbes, from Costa Rica. Fieldwork was conducted from 28 May 2023 - 14 June 2023 in Alajuela Province, Costa Rica at the sites described below. At the conclusion of fieldwork, export permits were filed by Dr. Ronald Vargas, subdir. Soltis Center, to export biological samples from Costa Rica to the United States.

Texas A&M Soltis Center(10.383137, -84.617217). The Soltis Center is a field research station and community educational center established in 2006 to facilitate academic research interests in Costa Rica. Its campus features two rows of 8-person bungalows, situated on a mountain slope (450 – 1,800 m above sea level). These bungalows overlook the main visitor center which had attached classrooms, an insect collection room, cafeteria, kitchens, laundry, and maintenance areas. All food scraps produced by the Soltis Center kitchen were taken daily ca. 15:00 to feed pigs at a local farm (see below). From the Soltis Center, several trails lead directly into the eastern edge of the Bosque Eterno de los Ninos (Children’s Eternal Rainforest), a large primary growth tropical wet forest connected to the larger Monteverde Conservation Area. However, the vegetation on the grounds themselves was mostly comprised of lawn grass and ornamental plants maintained by staff (though also included a 80+ species-orchid sanctuary), or secondary growth forest dominated by fast-growing pioneer species, viz. Cecropia spp. (Rosales: Urticaceae) (Breviglieri et al., 2019). Compared to the previous year, the vegetation in the region was dry and brittle, brought on by an extended drought during a La Niña year.

Smallholder Farms in San Juan(10.380592, -84.613538). While rainforest lay west of the Soltis Center, to the east was the village of San Juan (near Pocosol). Since San Juan was mainly comprised of smallholder farms, there was the potential to find high numbers of black soldier flies in the vicinity, since earlier reports state that BSF used to be found in dense mats near poultry/swine manure (Sheppard et al., 2002). Residents of this farm engaged in subsistence-level farming. The family’s property included a plot of pastureland where cows, goats, and sheep grazed; another plot of patchy hardwood and fruit trees where chickens foraged freely in the area around their coops up until the edge of a pit where the residents dumped trash; and a third plot where yucca was mainly grown in monoculture. A preliminary search for BSF on the grounds helped narrow the study area to the second of these areas, i.e., around the chicken coops. In this area pigs were also raised in styes and fed silage made from locally sourced grade-3 feed, supplemented with fruits and vegetables that grew on the property (e.g., bananas, plantains, starfruit). The pig manure drained into a small swale, which attracted many insects including calliphorid spp. (Diptera), and euglosisne orchid bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae), which could be easily identified based on their wing-buzzing (Kimsey, 1980).

Finca Luna Nueva(10.388018, -84.598919). On the advice of Soltis Center Staff, La Finca Luna Nueva Ecolodge (New Moon Estate and Ecolodge), henceforth “Finca Luna”, was investigated as well, which lay 5-minutes by car east of the Soltis Center. Finca Luna was advertised as a ‘recreational paradise’ where visitors can enjoy a hike through pristine tropical rainforest and farm-to-table dining experiences (Fincalunanuevalodge.com). Its on-site restaurant was supported by its own syntropic farm, following the system pioneered by E. Götsch, which focuses on harnessing naturally-occurring processes to simulate natural forest succession instead of artificial inputs (Andrade et al., 2020). Finca Luna’s plant community was engineered to produce fruit from multiple canopy layers simultaneously, yielding 200 varieties of fruits and vegetables per annum including heirloom tomatoes and avocado, guanabana, mango, caviar lime, among others. As such, the grounds of Finca Luna Nueva offered a hyper-diverse array of habitats to potentially find BSF in, including cattle pasture, crop rows, greenhouses, fruit trees, tropical forest, and various buildings. Indeed, Finca Luna was already home to an open-air BSF compost facility sheltered underneath a large wooden gazebo. Preliminary exploration around the grounds narrowed our focus to this BSF compost facility as a known center for BSF activity. For instance, in addition to the BSF compost center, there was an additional enclosed compost facility for processing dairy cattle manure, but no BSF were found there. Instead at the open-air compost facility, BSF from the wild readily visited to oviposit and were reportedly present year-round in abundance (personal communication from farm workers). The compost was produced from food waste from the Ecolodge’s restaurant (e.g., tropical fruit, vegetables, eggshells) which was brought daily and cycled through a three-stage aerobic composting system. Over the course of a week, the compost was successively cured in 1m3 bins, until being added to a large pile to hot compost (3m × 1.5m × 0.75m, L × W × H, set at angle of repose) which was churned biweekly to vent heat and control for anoxia. The finished compost was used to fertilize fields and the estimated amount of compost at the site was between 3-4 m3.

Transects. To determine where and how often BSF occur in the wild, transects were established and surveyed following previous examples for other lekking insects (Alcock, 2000; Alcock et al., 1989; Kimsey, 1980). Since we had little a priori knowledge of where BSF might be at the Soltis Center, 30-m transects (n = 12) were established haphazardly throughout the campus, with some extending into trails that permeated secondary growth forest. At the farm, six 30-m transects were erected to follow putative flight paths to the chicken coop and pig pens from the nearest tree stands or surrounding foliage. At Finca Luna observations were made on (n = 9) 30-m transects. A single transect ran within the composting center, four transects were orientated along each edge of the compost facility, and an additional four transects radiated outwards, two of which ran directly through established hiking trails, while others cut perpendicular to these trails through heavy vegetation. Logistical issues as well as sporadic rains made sampling at the same time each day difficult. Transects were walked at the Soltis Center on 10 June 2023 between 9:00 and 11:25 (n = 2 sets of 10 observations); at the farm in San Juan on 31 May 2023 - 6 June 2023 as early as 07:25 and as late as 14:45 (n=14 sets of 6 observations); and at Finca Luna from 07 June 2023 - 09 June 2023 as early as 09:49 and as late as 16:48 (n = 7 sets of 9). Each transect was walked 4 times in a span of 2 min and the number of BSF sightings was recorded. The sequence in which each transect was walked was randomized between two observers. At the beginning of each observation period, dry bulb temperature (°C) and relative humidity (%RH) were collected with a HT607 Temperature & Humidity Meter (Protmex International Group CO., LTD, Shenzhen, China). In addition, UV AB (280-400 nM) irradiance (i.e., solar power (µW/cm2) was recorded during the replication window using a UV513 AB UltraViolet Light Meter (GENERAL, Taiwan).

Canopy Observations. During the same day-time intervals as transect observations, observations within the forest canopy was simultaneously conducted by spanning a ladder at n = 3 locations sites at the smallholder farm (i.e., a lone palm, clusters of banana ‘trees’, or within dense canopy of an unknown hardwood species) and n=2 locations on the east side of the compost facility at Finca Luna. Each location was observed at least twice for periods lasting approximately 10 min in a random order by two observers.

Specimen Collection. Live specimens were captured whenever possible due to the rarity of black soldier fly sightings, except for at Finca Luna where sightings were nearly constant (even during rain). Adults were collected with nets and larvae were collected by hand. As adults were caught, their sex was determined via examining the external genitalia. This was tallied determine the sex ratio across field sites. Flies were typically caught while resting on foliage at Finca Luna Nueva and the farm in San Juan. Whenever a specimen was caught, it was transferred immediately to a Falcon Tube and covered in RNAlater™ solution, which induced euthanasia. Specimens were temporarily stored at -20 C in the Soltis Center lab, prior to being exported to the United States. Half of the specimens from each site (Soltis Center (n = 7), the farm in San Juan (n = 6), and Finca Luna Nueva (n = 23)) were randomly divided and sent to either Indiana University - Purdue University Indianapolis (Indianapolis, IN, USA) for genetic analysis or to Mississippi State University (Starkville, MS, USA) for microbial analysis.

Field data cleaning. Field data were prepared in Excel (Version 2401, Build 17231.20236 click-to-run) by replacing NA values of BSF counts with zeroes, since these zeroes would not affect total summed counts when a Pivot Table was applied. Any NA values for the environmental covariates (e.g., temp, RH, and UV) were imputed by using the mean average of the remaining non-NA values from that same set of observations. Since no BSF were observed from any of the Soltis Center transects (n = 20 observations) and moreover were temporally psuedoreplicated since all observations at the Soltis Center occurred on the same day, so these data were excluded. In addition, due to data loss, there were also n = 8 rows of NA values which were deleted so that correlations could be calculated, leaving a total of n = 147 observations to analyze. In some cases, the number of BSF was so high during a transect-walk that it was uncountable, but as to not skew the analysis, these were recorded as values of 20. In addition, no adult black soldier flies were observed during canopy observational periods, and so this data was also discounted.

Observation counts vs. distance model. To predict

where BSF were most likely to be spotted, observation counts were summed with respect to transect. Distance from the oviposition site of each transect was estimated by first downloading satellite images of the study sites at the Private Farm and Finca Luna Nueva from Google Maps on 29 June 2023 and are provided in the

Supplementary Materials. Using the markup feature in Apple Photos (Version 8.0, 531.0.100) photo editing software, the location of transects were defined. The edited photos were imported into ImageJ (version 1.54d) and then, using the measure tool, the distance from the center of the oviposition substrate to the center of each transect measured and calibrated to a 30.48-m (100ft) reference scale. To confirm that the center of the transect was appropriate, we also tested distance to either end points of the transect, and all three performed qualitatively similar. Because distance could then be abstracted across the two sites, data from both sites were pooled, and a regression model fit to these data. To select the best model, data was entered into an online curve-fitting software (MyCurveFit.com, Beta Version), and the model which minimized Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) was selected. The model was verified using the online computational answer engine, WolframAlpha (Wolfram Research, 2009) and then plotted in R studio (version 4.1.2).

Observation counts vs time. Using the pivot table function in Excel, total counts of BSF observations were summed with reference to the time of observation. Time was rounded to the nearest quarter hour (i.e., 15 minutes). Counts/time were plotted using the inbuilt plotting function. Time was then converted into a decimal so that a 4th-degree polynomial regression could be fit to the data, The 4th degree polynomial was selected because this function would have 2 inflection points (i.e., changes in tonicity), corresponding to the bounds of optimal time ranges for future field sampling.

Abiotic Factors. To determine whether abiotic factors had an impact on the total BSF observed, a multiple correlation analysis using Pearson’s distance was conducted to determine the linear relationship between the number of black soldier fly observations (totalled for each quarter hour) to temperature (rounded to the nearest 2.5 °C), RH (rounded to the nearest 2.5 percent), and UV-light irradiance (rounded to the nearest 100 µW/cm2). These relationships were also plotted, and regressions fit to each.

Gut Content Analysis. To investigate dietary sources in adult black soldier fly, gut content analysis was performed by dissecting each specimen to isolate the alimentary canal, including the midgut, hindgut, and any visible crop. DNA was extracted from gut contents using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Germany), following the manufacturer’s protocol with a modified elution volume of 25 µL. To identify plant and vertebrate-derived dietary inputs, we amplified ITS and 16S rRNA genes using specific primers for plants and vertebrates (Vertebrate primer 1 (16S_H2714): 5'-CTCCATAGGGTCTTCTCGTCTT-3', Vertebrate primer 2 (16S_L2513): 5'-GCCTGTTTACCAAAAACATCAC-3', Plant primer 1 (ITS-u2): 5'-GCGTTCAAAGAYTCGATGRTT-3', Plant primer 2 (ITS-p5): 5'-CCTTATCAYTTAGAGGAAGGAG-3', respectively as described by Owings et al. (2019). PCR amplification success was verified via gel electrophoresis, and successful products were purified and sequenced bidirectionally using BigDye™ Terminator Cycle v3.1 Sequencing chemistry (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Resulting sequences were manually edited and aligned, and taxonomic identification was performed using the NCBI BLAST tool (version 2.15.0) (Camacho et al., 2009), retaining top hits based on E-value rankings.

Gut Microbiome Analysis. Sixteen adult and two larval samples previously preserved in RNALater™ (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) (as described above) were sent to Mississippi State University where they were dissected to collect guts for analyses. DNA was isolated from gut samples and samples were sent to Michigan State University Genomics Research Technology Support Facility for amplicon library preparation and sequencing. The V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene were amplified using dual indexed, Illumina compatible primers following the protocol described in (Kozich et al., 2013). PCR products were batch normalized using a PCR Normalization and Purification kit (Charm Biotech, USA) and the product recovered from the plates was pooled. The pool was then concentrated and cleaned up using a QIAquick Spin column (Qiagen N.V., Germany) and AMPure XP magnetic beads (Beckman Coulter Life Sciences, USA). Afterwards, the pool was quality checked and quantified using a combination of AccuGreen™ High Sensitivity dsDNA (Biotium, Inc., USA), 4200 TapeStation HS DNA1000 (Agilent Technologies, Inc., USA), and Invitrogen Collibri Illumina Library Quantification (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) qPCR assays. This pool was then loaded onto one (1) MiSeq v2 Standard flow cell (Illumina, Inc., USA) and sequencing was carried out in a 2x250bp paired end format using a MiSeq v2 500 cycle reagent cartridge (Illumina, Inc., USA). Custom sequencing and index primers complementary to the 515f/806r oligomers were added to appropriate wells of the reagent cartridge. Base calling was done by Illumina Real Time Analysis (RTA) v1.18.54 and output of RTA was demultiplexed and converted to FASTQ format with Illumina Bcl2fastq v2.20.0 (Illumina, Inc. USA). A summary of the run output is attached below. Basic QC information about sequence data is provided by the accompanying FastQC reports.

Raw FASTQ files barcoded Illumina 16S rRNA paired-end reads were assembled, quality-filtered, demultiplexed, and analyzed in the CLC Workbench 25.0.2 (Qiagen N.V., Germany). Reads were discarded if they have a quality score <Q20, contained ambiguous base calls or barcode/primer errors, and/or were reads with <75% (of total read length) consecutive high-quality base calls. Chimeric reads were removed using the default settings. Sequences that remained were binned and classified into Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) to a 97% sequence similarity. The highest-quality sequences from each OTU cluster were taxonomically assigned and identified using BLAST against reference sequences from the most up to date SILVA 97% reference dataset, and low abundance OTUs (<10 reads across all samples in the total dataset) were removed. An additional filtering was performed manually to remove sequences associated with mitochondria or chloroplast. Relative abundance tables were generated to family level and associated with metadata.

Alpha and beta diversity analyses were performed with metadata including larvae, adult, and collection location. Rarefaction analysis was conducted with minimum depth of 1 with the number of points set to 20 and the number of replicates at each point set at 100.00. Relative abundances and significance of differentially abundant taxa were calculated. Chao-1 and Shannon diversity index (alpha diversity) were calculated and compared against metadata using pairwise Kruskal-Wallis. Alpha diversity was also generated based on phylogenetic diversity to family level. Generalized UNIFRAC analyses and Bray-Curtis dissimilarities were calculated and compared against metadata using pairwise PERMANOVA with Bonferroni corrected p-values (permutations = 99,999). Dissimilarities were used to create PCoA plots. Statistical significance was determined as the Bonferroni corrected p-value: p<0.05.

Statistical difference in taxon abundance was analyzed in the CLC Workbench that performed a generalized linear model differential abundance test on samples, or groups defined by metadata. The tool modelled each feature (e.g., an OTU, an organism or species name or a GO term) as a separate Generalized Linear Model (GLM), where it is assumed that abundances follow a Negative Binomial distribution. The Wald test was used to determine significance between group pairs with correction accounting for multiple comparisons using the false discovery (FDR) rate and significance counted as p<0.001.

Results

BSF Sex Ratio. Black soldier flies were haphazardly caught and sexed across three field sites in Costa Rica. All flies were caught with relative proximity to an oviposition site: a kitchen containing food scraps at the A&M Soltis Center, a chicken coop at the Farm in San Juan, and in a compost bin at Finca Luna Nueva. A total of 51 females were collected, and 1 male was collected leading to a sex ratio (F:M) of 0.980 averaged across all three sites (

Table 1, below). All the flies caught at the Soltis Center, and the Farm in San Juan were included in this number, whereas at Finca Luna Nueva a subsample of n

> 30 was chosen, since (via the central limit theorem) this is generally considered large enough to sufficiently estimate population parameters.

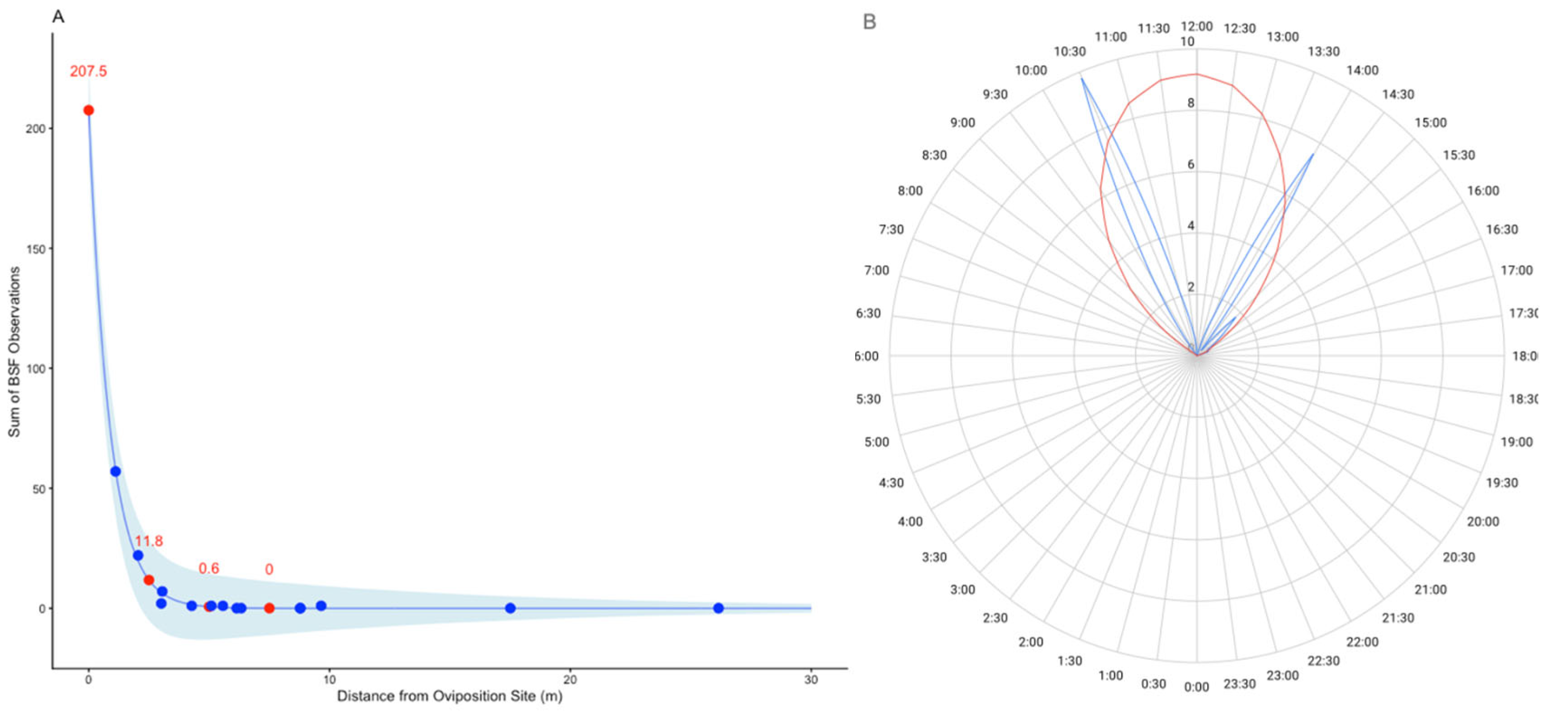

BSF Observations vs Distance from Oviposition Site. A Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was conducted on un-pooled transect data (i.e., counts of BSF sightings) using an online calculator (socscistatistics.com) to test for normality (p-value <.00001), and indicated data were distributed non-normally (5.049 skew, 27.59 kurtosis). Spearman’s Rho was then calculated to determine whether distance and counts were correlated. The test suggested the relationship between the variables was highly significant (2-tailed p = 0.0011), and the values were highly negatively correlated (rs = -0.85). Following this, an exponential regression was fit the data (R2 = 0.99, p < 0.001, DOF = 11) and was selected based on minimized AIC (55.62) and BIC (57.54) scores compared to the tested alternatives (e.g., linear, log, multiplicative inverse, polynomial, half-life models). The equation takes the form, Y = a + be-cx , where y is the number of observations, and x is the distance from the oviposition site; a is the intercept, and b is a scaling factor that has unknown biological meaning: . Like the correlation test, the model has a decreasing trend and yields the following predictions: at 0-m, more than 206.99 observations made on average (though this number is an underestimate), at 2.50 m there will be 11.68 observations, at 5.00-m there will be 0.62 observations on average, and at 7.56-m and beyond there will be 0 observations.

BSF Observations vs. Time. To determine

when BSF were most likely to be observed irrespective of site or transect, counts of BSF were totaled with respect to the time they were observed rounded to the nearest quarter-hour. Plotting this (

Figure 1) showed that BSF were observed between 0945-1630 hours and displayed essentially a bimodal distribution with peaks near 10:15 and 13:45; however, this was likely because fieldwork was rarely conducted when lunch was served at the field station (i.e., 12:00 noon). Since there isn’t a biological reason why BSF would not be active at this time, a 4

th-degree polynomial regression (which would have 2 inflection points) was fit to the data (using decimal percent values for time, i.e., 12:00 noon = 0.50), given by the following equation:

. The local maximum of this function predicts that the highest numbers of BSF will be observed at 12:00 noon, while the inflection points indicate that BSF sightings should be much rarer at times earlier than 09:00 or later than 14:30. Predictions from this model were then plotted on a radar plot along with observed values multiplied by a scaled by a factor of 0.2.

Abiotic Factors. The extrema and weekly averages of temperature (°C), humidity (%RH, Abs Humidity, Dew Point), and UV-light irradiance (µW/cm

2) are reported in

Table 2. A multi-correlation analysis was the connected to see the relationship between the covariates and BSF observations (

Table 3). Of these covariates, both temperature (r = 0.29) and UV light (r = 0.283) were both positively correlated with increasing observations of BSF, whereas relative humidity was negatively correlated with counts of flies (r = -0.16). Temperature and UV-light were positively related to one another (r = 0.55) suggesting warm days generally coincide with sunny days. There was no relationship between UV-light and humidity (r = 0.123) reflecting the fact that the two do not directly interact. Finally, humidity was inversely related with temperature (r = -0.438), which is consistent with the fact that in open systems warm air holds relatively more water vapor, causing RH to decrease.

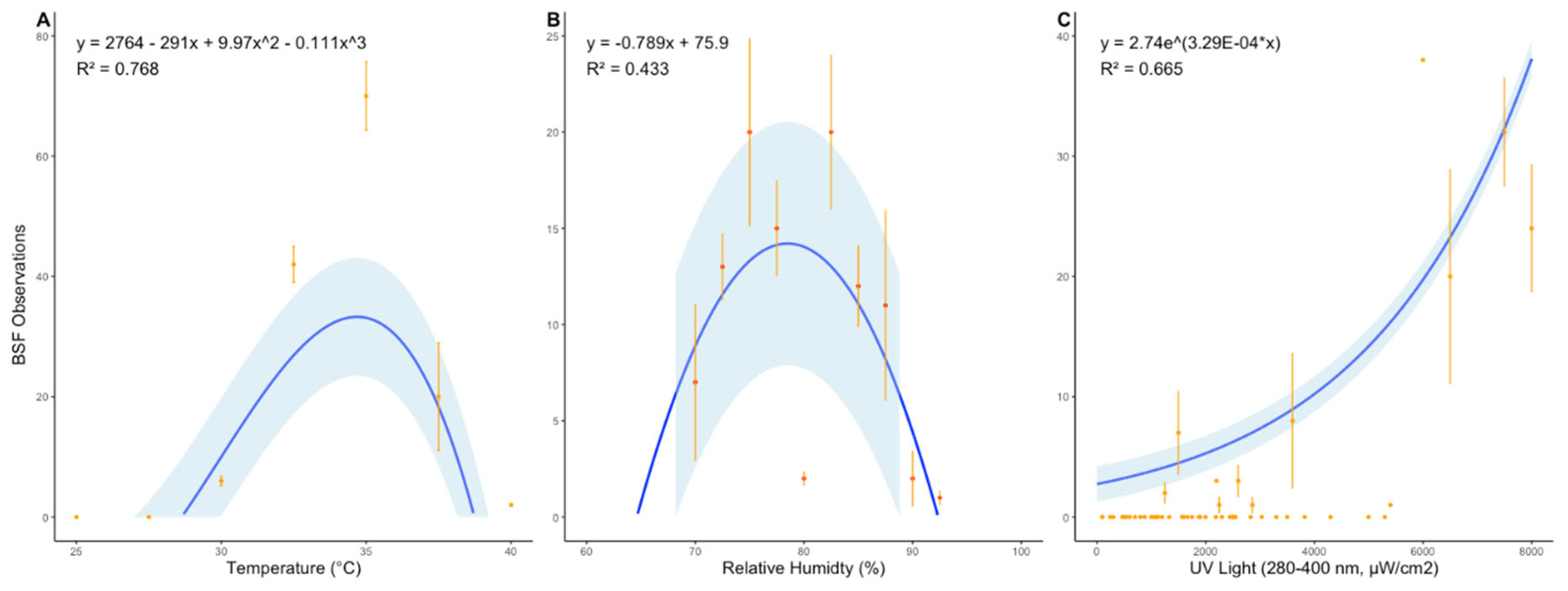

Counts of BSF were plotted against each of these factors, and regressions fit (

Figure 3). Doing so revealed a right-skewed polynomial relationship (

; R2 = 0.657) between BSF counts and temperature (

Figure 3A), indicating that observations slowly increase with temperature, up to an optimum of 34.7 °C, and then quickly fall off. A decreasing quadratic relationship (

; R2 = 0.433) was found between BSF counts and humidity (

Figure 3B) indicating an optimum of 78.5 %RH was associated with the most BSF observations. Lastly, an exponential relationship between BSF and UV-AB light (

;

) was found, indicating (

Figure 3C) that BSF observations rapidly increase along with increasing UV-light up to a maximum of 8000 µW/cm

2.

Adult Feeding Behavior. Only one of 16 samples exhibited plant DNA amplification, however sequencing of this sample was ultimately inconclusive. For all 16 adults, vertebrate DNA amplification indicated that they are seeking and feeding on wild resources. BLAST analysis of 16S sequences with the NCBI database showed that the most likely species was human (Homo sapiens).

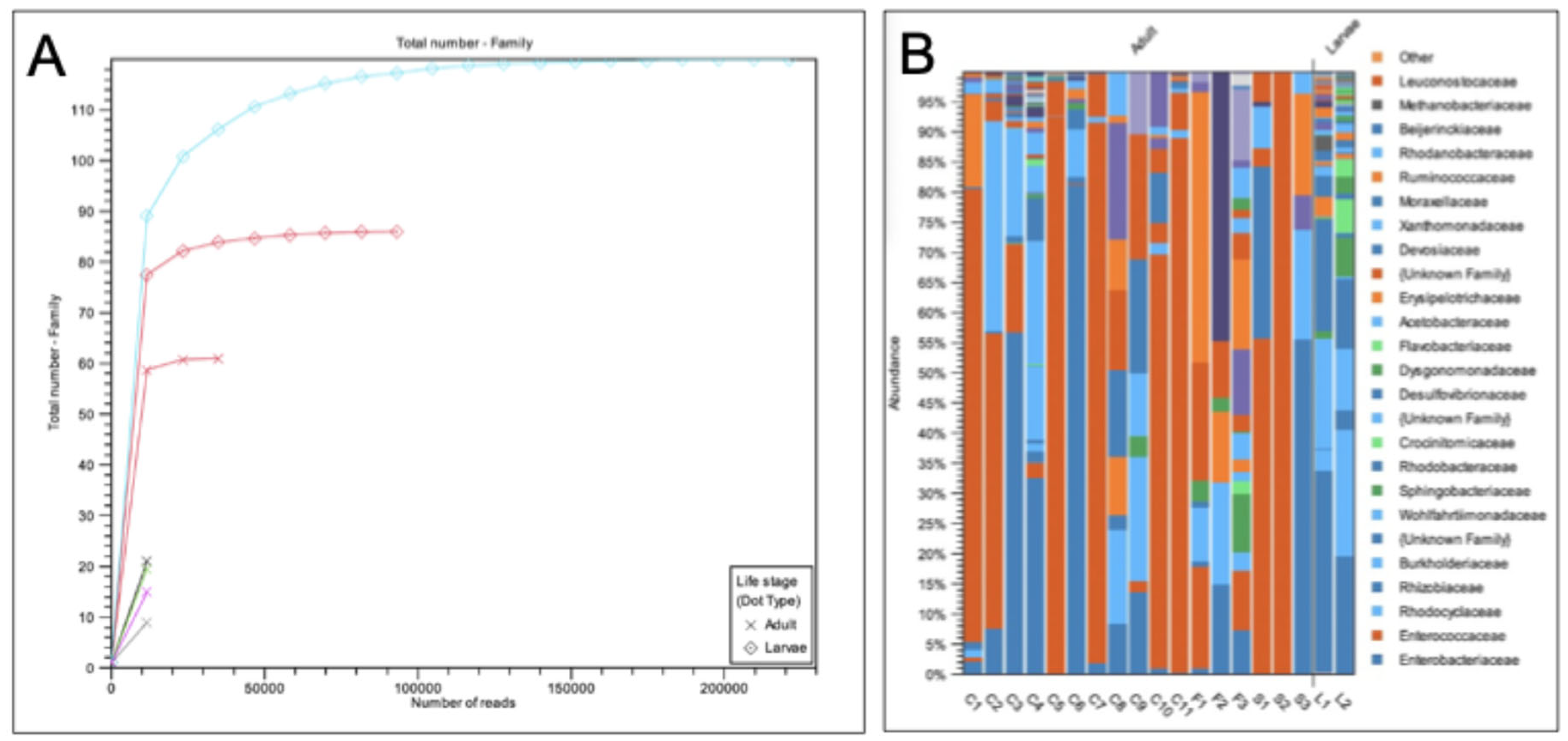

Gut Microbiome Between and Among Life Stages. Rarefaction analysis revealed differences higher bacterial diversity in black soldier fly larval compared to adults (

Figure 4A) and here was a great deal of variation among and between life stages (

Figure 4B). The number of OTUs at the family level was much higher in larval than in adult samples, however this difference was not significantly different. This suggests that larvae harbor a more diverse bacterial community, likely due to broader environmental exposure of differing physiological niches.

Relative abundances support this trend (

Figure 5). Larvae maintained more even microbial communities, characterized by families including

Enterobacteriaceae, Rhizobiaceae, Burkholderiaceae, and

Sphingobacteriaceae. In contrast, adult samples were dominated by a narrower set of taxa, with

Enterobacteriaceae and

Rhodocyclaceae compromising most of the microbial load. Several low-abundance families were grouped as “other,” especially in adults indicating higher variability or reduced richness at this stage (

Figure 5A).

Differential abundance analyses measured 1,018 significantly different relative abundances of taxa between larval and adult samples (

Figure 5B). Only two identified indicator taxa were identified for adults:

Sphingomonas and

Fingoldia magnia. Dechlorobacter, Proteobacteria, Morganelli morganii, Sphingobacterium paucimobilis and

Ottowia were among highest in differential abundance (i.e. indicator taxa) in larvae compared to adult samples (Supplemental

Table S1).

Principal Coordinates Analysis (PCoA) based on Bray-Curtis dissimilarity revealed clear separation between larval and adult microbiomes (

Figure 5C). Larval samples clustered distinctly from adult samples, which explained 23.96% of total variation. This life stage-based clustering suggests that ontogenic shifts significantly influence the microbial community structure.

Geographic Variation in Adult Microbiomes. Differences in the microbiome composition were apparent among adult flies collected from different environments—Soltis Center, “Soltis”, the Farm in San Juan, “Farm”, and the Compost facility at Finca Luna, “Compost”. Bray-Curtis dissimilarity between Compost and Farm samples was higher (

p=0.09 PERMANOVA) than between Compost and Soltis (

Figure 6A). Generalized UniFrac distances were significantly higher (

p=0.008) between Compost and Farm samples, suggesting a greater divergence in microbial communities, indicating a substantial phylogenetic shift due to location (

Figure 6B). There was also a noteworthy, though not significant difference between Compost and Soltis samples (

p=0.07), though Soltis and Compost samples share a greater proportion of their evolutionary history (

Figure 3B). In practical terms, this means that the types of microbes present in the two samples are more closely related on the phylogenetic tree, and their overall community composition is more alike.

Family level relative abundance of adults collected at the Compost site were enriched in

Enterobacteriaceae and

Moraxellaceae, while Farm samples exhibited a higher proportion of

Rhizobiaceae, Bacillaceae, and

Rhodobacteraceae. Soltis samples were dominated by

Enterococcaceae, suggesting a highly specialized or homogenized community at that site (Supplemental Table X). Farm microbiomes had more rare taxa compared to other locations (highest 8.0%), whereas Compost and Soltis were dominated by fewer taxa (14.0% and 26.0%, respectively). This suggests a more complex and potentially more resilient microbial community among Farm samples (

Figure 6C).

Differential Abundance analyses measured environment-specific indicator taxa that discriminated among sites (

Figure 6D). The comparison between Farm and (Finca Luna) Compost yielded the largest number of unique indicator taxa (n=35) while the Soltis vs (Finca Luna) Compost and Soltis vs Farm yielded 15 and 1 unique taxa, respectively. Notably, 14 taxa were shared between Soltis vs (Finca Luna) Compost and Soltis vs Farm comparisons, indicating a core microbial signature associated with the Soltis environment. Taxa including

Streptococcus sp., Mycobacterium sp., and

Sphingomonas sp. were significantly more abundant in Farm samples (FRD-adjusted p≤ 3.12×10⁻⁶) while Compost samples were enriched in

Bacillus sp., Aureimonas sp., and

Gracivacillus halotolerans.

In the Soltis vs. Compost comparison, Soltis samples showed higher abundance of

Rhizobium sp. Alloicoccus otitis, and

Staphylococcus aureus (p < 0.001), while Compost samples featured taxa like

Pantoea sp., Serratia sp., and

Thermoactinomyces spp. In the Soltis vs Farm comparison, Soltis flies harbored more

Streptococcus sp., Mycobacterium sp., and

Finegoldia magna, whereas Farm flies were enriched in

Veillonella sp., Neisseria sp., and Actinomyces sp. (p = 0.05). These differences underscore the role of environmental factors in shaping taxonomic structure within adult microbiomes (Supplemental

Table S1).

Discussion

The objectives of this study were to document black soldier fly (BSF) behavior in the wild and test the hypothesis that BSF exhibit lekking. We examined the sex ratio and spatiotemporal distribution of black soldier fly adults at 3 field sites in Alajuela, Costa Rica. In short, we determined that wild BSF most likely exhibit a lek mating system. The models we developed predict that most female BSF will be found at a maximum 7.5-m from the oviposition site, during the middle hours of the day, and under optimal ambient conditions of 34.8 °C, 78.5% RH, and full sunlight (i.e., 8000 µW/cm2 of UV-AB radiation), thus informing optimal cage designs and rearing practices. Adult BSFs were also examined to determine what, if any, food resources they might naturally utilize, and the study found the presence of plant (n = 1 of 16 specimens) and vertebrate DNA (n = 16 of 16 specimens) in the guts of adult BSF, suggesting they feed in the wild, and may engage in ‘mud-puddling’ behavior (see below). Lastly, the study also demonstrated that both BSF developmental stage (larvae vs. adult) and the environmental context (3 field sites sites) exert strong influences on the structure and composition of black soldier fly gut microbiome, and there appears to be a shared core microbiome across our sampled sites. Thus, the study expands our understanding of wild BSF mating and feeding behavior as well as host-associated microbial ecology, providing a foundation for targeted manipulation of BSF behavior and microbiota in applied settings.

Sex Ratio Analysis. The average adult sex ratio recorded across our three field sites was highly female-skewed (F:M = 0.98, n = 52) (Table x). This pattern is consistent with those of a previous field study that found high densities of female BSF (91.3% females, n = 123) ovipositing in chicken manure at a poultry farm (Tomberlin & Sheppard, 2001). Since highly skewed ratios deviate from the expected sex ratio of sexually reproducing organisms, which typically are near 0.50 (Ancona et al., 2017); this suggests that for our study a male BSF population existed somewhere unobserved, and is the missing piece to yield a balanced 50:50 sex ratio. Captive BSF emerge at a 50:50 ratio, although BSF reared from wild-caught flies have been shown to have a slightly biased sex ratio of 56% female (Tomberlin 2002). The near complete absence of male observations at our three study sites further suggests that males exhibit different habitat preferences compared to females, and that the ability of BSF to self-segregate by sex in captivity (N. B. Lemke et al., 2024; Salari & De Goede, 2024) is an evolutionary holdover from the wild, potentially as a way to maintain highly skewed sex ratios localized to sub-regions of the cages. Indeed, Tomberlin & Sheppard (2001) report high densities of males (91.9%, n = 109) establishing territories along a 10-15-m margin of hardwood forest located 100-m away from where the females were established. In captivity, biased sex ratios of breeding populations (ranging from 0.64 – 1.80 M:F) has been shown to trade-off with fitness and fecundity (Hoc et al., 2019).

Perching. Since most of the female specimens we caught were perching on top (adaxial) surface of plant leaves, this suggests a female preference for perching. There were several ‘tufts’ of ornamental plants near the corners of the compost facility gazebo where large numbers of (98% F:M) flies perched, putatively as a stopover either on their way to the oviposition site or away from it. As for the single male BSF sampled, we suspect that it had recently pupated and had not yet travelled away from the oviposition site. Since multiple mating and oviposition has been observed in captive populations (Chiabotto et al., 2024; Manas, Venon, et al., 2025; Muraro et al., 2024) it may be possible that females make multiple trips to the mating site and back. However, the adaptive advantage of this is unknown since mating is not known to stimulate additional egg production, and only a single mating is enough to completely fill a female’s three spermathecae with sperm (Manas et al., 2024; Manas, Labrousse, et al., 2025; Munsch-Masset et al., 2023). Certainly, long flights will have steep costs and fitness trade-offs (Beenakkers et al., 1984; Kaufmann et al., 2013) for an energy-limited fly (Harjoko et al., 2023). Thus, perching is an important way of economically conserving energy for females (N. B. Lemke et al., 2024) who might need to travel twice as far as males during their lives. Additionally, perching on the top-surface of leaves confers the benefit of early visual detection of predators (Sugiura, 2020), and can be contrasted with insects that instead perch on the bottom (abaxial) leaf surface to hide. We observed wild BSF perching on the top surface of leaves, but were easily startled, and did not at all display the docility commonly seen in captive strains (personal observation). Indeed, the theory on the ecology of fear predicts that as predators become less abundant (as is the case in captivity), prey species lose their tenacity and vigilance (Brown et al., 1999). Conversely, an early report of wild BSF describe females as being tenacious (i.e., highly active), returning to the oviposition site >100 times after being harassed by bees (Copello, 1926).

Distance from Oviposition Site. A model was built that related counts of BSF observations with the distance away from a putative oviposition site (

Figure 1). The model gave two asymptotes; a vertical asymptote at the origin, indicating that uncountable numbers of BSF will be spotted immediately near the oviposition site; and a horizontal asymptote indicating virtually no BSF are expected to be observed at a radius beyond 7.5-m. More haphazard explorations of the field sites took us a great distance away, and through a variety of locations (in the understory of forest patches, up into the tree canopy, on the roof of buildings, and in sewers and pipes beneath them). Despite these efforts BSF were only ever found near an identified oviposition site. However, since no mating was observed within the 30-m radius, and females were gravid (indicated by readily oviposited eggs when placed within Falcon tubes), this must mean that females are travelling far afield to mate with males since oviposition activity peaks 2-3 days

after mating (N. B. Lemke, Li, De Smet, et al., 2025; J. K. Tomberlin et al., 2002). Although we did not collect fitness data of the eggs laid by captured females, in another study <1% of virgin flies laid eggs in collection cups (J. K. Tomberlin et al., 2002).

BSF relation to human-modified environments. The high abundance of BSF near identified oviposition sites, this suggests that ‘wild’ BSF are most likely to be found in close association with human-modified habitats, since composting fruit, vegetables, and manure provide a readily exploitable resource to develop in. Thus, we posit that finding black soldier flies in ‘the wild’ is likely a matter of finding a high volume of substrate for them to colonize.

Most of our BSF observations were made at Finca Luna Nueva where, ~3 to 4-m3 of compost was reportedly available year-round for BSF to colonize. Here, large numbers of BSF were directly observed to oviposit into the slits between the wooden boards of the compost bins. The local farmers communicated that BSF were found here year-round.

Compare this to the smallholder farm in San Juan where adult BSF sightings were much rarer. Here, the volume of substrate was comparatively much smaller, and while many insect larvae were found in the swale into which pig fecal sludge drained, this area was also home to ~100 foraging chickens, and so most of the larvae were quickly consumed (personal observation). We theorize this had the effect of depressing adult BSF populations, and so the swale served mostly as an ecological trap. The dynamic nature of the substrate itself (e.g., from an influx of pigs, rain) could have also played a role. Adult Calliphorids were abundant at this site, and these species are able to take advantage of ephemeral resources through quick colonization (T. M. Barbosa et al., 2023).

Lastly, at the Soltis Center, the resource that attracted BSF was likely the fruit and vegetables scraps produced in the kitchen, since BSF were almost always collected around lunchtime, and likewise would have been an ephemeral resource since each afternoon the scraps were given to the farm for pig feed. Within the Soltis Center, adult specimens were only ever found resting along large, screened windows in kitchen/laundry area, which we believe acted analogous to a flight-interception trap (wherein BSF could enter easily but not leave). BSF have been described as reluctant to enter enclosed spaces (J. K. Tomberlin et al., 2002). Another Neotropical genus of soldier fly, Merosargus spp. (Diptera: Stratiomyidae) (F. Barbosa, 2015) is likewise attracted to damaged vegetative matter, and BSF themselves have been shown to prefer to oviposit in plant-based substrates (Kotzé & Tomberlin, 2020).

BSF were never observed within primary and secondary forest, likely because it is there where BSF face extreme competition from opportunistic scavengers (ants, calliphorid and sarcophagid flies, and scarab beetles) (Cornaby, 1974). Ants alone are known to dominate the structure of tropical forest communities through herbivory, predation, and mutualisms, and moreover can comprise up to 50% of arthropod biomass. Interestingly, we note that neither dead BSF or remnants of adult flies were never found at the compost facility, and there were never any observations predators/scavengers of BSF (but wasps were frequent and thus possible parasitoids). Within the Soltis Center bungalows, however, adult BSF were predated by ambush lizards and web-building spider spp. (personal observations), and indeed both of these guilds have adaptive foraging behaviors to catch fast-moving prey (Gasnier et al., 1994; Wise, 1995).

Lekking? Past studies have utilized Bradbury’s expanded criteria for lekking species to determine whether lekking is occurring (J. Bradbury et al., 1986). However, since mating BSF were not directly observed during our study, we need to instead consider what alternative mating systems to lekking would look like, and rule these out. For instance, resource-based polygyny would entail that males establish territories around apparent resources (e.g., the oviposition site, water, shelter), but we found the opposite. Similarly, female-defense polygyny would entail that males establish territories around the females themselves, but again we find the opposite. Moreover, both systems seem very unlikely since the density of females is so high that defending a territory around the compost facility would be uneconomic for males (Emlen & Oring, 1977). Additionally, since mating was never observed in our study (but high numbers of females were), we can also assume that scramble competition polygyny is also not occurring. If it was, we would see males (literally) scramble after females to mate. Lekking is left as the only mating system consistent with our findings, in which males establish territories at a separate site and females visit it strictly to mate. Such is consistent with a prior field report (J. K. Tomberlin & Sheppard, 2001) and a conceptual model informed by fieldwork(N. B. Lemke et al., 2023). The findings of this study thus provide additional evidence to suggest that lek-behaviors, e.g., sex-based aggregations, (N. B. Lemke et al., 2024) are indeed evolutionary holdovers from the wild still present within the captive niche.

Temporal Dynamics. During our study we recorded the time of observation for each transect, as well as the local abiotic conditions (i.e., temperature, relative humidity, and UV-light irradiance) using handheld devices. Regressions were fit to each of these data, revealing the following predictions: (a) BSF are most likely to be observed between 09:00-14:30 hours, with a peak occurring at 12:00-noon (

Figure 1B). Since sunrise in Costa Rica is ca. 05:30, this suggests BSF are not immediately active in the morning. (b) BSF sightings are predicted to slowly increase in frequency along with increasing temperature, reaching a peak at 35 °C, after which they rapidly decline, and no observations are expected beyond 40 °C (

Figure 3A). (c) BSF sightings are predicted to increase up to an optimum humidity of 78.5% RH (

Figure 3B) and then decrease at a symmetrical rate after this critical point. (d) BSF sightings are predicted to exponentially increase with UV-light (

Figure 3C).

Interestingly the maximum UV-AB (280-400 nM) photon density measured by our handheld was 8000 (µW/cm2), which is the theoretical maximum of UV light that would be measured in full sun at noon on a clear day, i.e., 8% of the total 100,000 µW/cm2 direct beam solar radiation is UV light (energy.gov). This is several orders of magnitude more intense that what we have observed in greenhouse or indoor cages using the same measuring device (personal observation). Since solar radiation is scattered or absorbed through clouds and water vapor, dust and pollutants, windows and BSF cage materials; the primary factor that accounts for heightened BSF activity in natural lighting (N. B. Lemke et al., 2023; N. B. Lemke, Li, Dickerson, et al., 2025) may very well be higher intensities of UV-light than can be produced by artificial lamps, though of course natural light has many other components including IR and heat.

Each of these patterns we found is congruent with findings in both wild captive populations: BSF are known to peak in activity in the middle of the photoperiod and are not known to be active at night (Tingle et al., 1975). Previously BSF were documented to perch on plants until temperatures exceed 27 °C (Booth & Sheppard, 1984), and have an upper thermal tolerance of around 40 °C (Sheppard et al., 2002). BSF also lay 80% of their clutches when the ambient humidity is greater than 60% (J. Tomberlin & Sheppard, 2002), but prefer oviposit in dry cracks near the substrate (Copello, 1926), as we also observed. BSF require high-intensity UV-Blue light to trigger mating activity (Oonincx et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2010). The literature reports a minimum photon density threshold of 63 uMol/m2 for BSF mating to occur (Sheppard et al., 2002), though these units are not easily converted to solar irradiance measured in our study.

Adult Feeding Behavior. In this study, all dissected BSF contained vertebrate DNA which was then confirmed as was human, which aligns with previous findings of high human DNA in the guts of other fly species (Owings, 2012), though specimen contamination cannot not be ruled out entirely. The most likely source of human DNA in the environment was an open-pit latrine/outhouse (one of which was located on the northern end of Finca Luna transect, indicated by the orange-rooved building in

Supplementary Figure S2). Moreover, if sodium or other salts are a limiting nutrient in the wild, latrines might be an opportunity for BSF to acquire these from urine. The behavior of insects seeking out salts in moist ground, sweat, rotten flesh, and excrement has been referred to as ‘mud-puddling’ and has been documented in some (but not all) herbivorous insects (butterflies, moths, honeybees, etc.) (Xiao et al., 2010).

Although adult BSF can reproduce in caged systems without a nutrient supply, both watering and feeding them extends their lifespan (J. K. Tomberlin et al., 2002). Although much of the discourse around BSF considers them as income-breeders (wherein it is the larvae that acquire and store nutrients), they may lie somewhere in middle of the continuum between strict income breeders and capital breeders (N. Lemke & Puniamoorthy, 2025). Indeed other Dipterans, strictly need nutrients to reproduce: blow flies (Diptera: Calliphoridae) require carbohydrates for flight and females need protein for egg development (Norris, 1965). Similar requirements exist for most blood-feeding Dipterans, including mosquitoes, tabanids, simuliids, stomoxyines, and chironomids (though some are autogenic) (Spielman, 1971). Thus, it is unsurprising that wild black soldier flies also feed as adults, though any fitness benefits remain unclear. Whether adult BSF utilize floral resources has also yet to be confirmed, potentially because nectar (a sugar) would be rapidly digested and not be detectible via DNA analyses.

Gut Microbiome. BSF gut microbial diversity shifted across life stage and sampling locations reflecting the dynamic and responsive nature of the black soldier fly microbiome. While the limited sample size (n = 2) for larval samples restricts our ability to perform robust statistical inference, this preliminary analysis revealed distinct compositional differences between the larval and adult microbiomes. These findings, though descriptive in nature, underscore the significant microbial shifts that occur during black soldier fly life stage succession.

Larval samples harbored greater family-level microbial richness compared to adults, suggesting that larvae maintain a more diverse gut microbiota potentially due to their direct interaction with heterogeneous and microbially rich substrates such as compost (

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). This aligns with previous findings showing that larvae often possess broader microbial repertoire to support digestion and nutrient acquisition in complex environments (Fu et al., 2023; Van Looveren et al., 2024; Zheng et al., 2013). In contrast, adult black soldier flies exhibited a less diverse but more consistent microbiota, dominated by a narrower range of taxa (

Figure 5A), indicating possible specialization or microbial streamlining during metamorphosis. Community composition analysis further underscored these life-stage differences. Larval microbiomes were enriched in families such as

Acetobacteraceae, Moraxellaceae, and

Sphingobacteriaceae, while adults showed a higher prevalence of

Enterobacteriaceae, and

Rhizobiaceae (

Figure 5A). However, some adult samples showed a very low number of taxa. This could be a function of limited feeding or previously shed gut content at the time of sampling, thus underestimating diversity.

Microbial profiles differed markedly across the three collection environments-compost, farm, and the Soltis facility-highlighting the influence of external conditions and microbial exposure on host-associated microbiota. Compost-derived adults exhibited high relative abundances of

Enterobacteriaceae, and

Moraxellaceae, while Farm-derived adults harboured more

Bacillaceae and

Rhizobiaceae, and Soltis samples were overwhelmingly dominated by

Enterococcaceae (Figure D); and interestingly, another study found

Enterococcaceae to be the most abundant genus in the guts of Costa Rican larvae (Khamis et al., 2020). These patterns we found in adult BSF were mirrored by significant clustering in both Bray-Curtis and UniFrac-based PCoA analysis (

Figure 4A and 4B). Differential abundance analyses revealed several location-specific indicator taxa, supporting the hypothesis that environmental microbial pools play a crucial role in shaping black soldier fly gut communities (

Figure 6C).

Conclusions

The results presented here provide novel insights into the unmodified population dynamics and environmental interactions of BSF in their native Neotropical environment. Together these findings serve as a vital comparison-point to BSF behaviours within an industrial niche and confirms a link between the ecologies of wild and captive BSF populations. Although BSF mass-producers may want to eventually select out some wild traits, documenting what occurs in the wild populations is still critically relevant for establishing a non-biased baseline for industrial applications as well as scientifically informed welfare protocols, including cage design and rearing protocols. In addition, these findings have important implications for BSF-based bioconversion systems since understanding how life stage and environmental exposure shape microbial communities can inform strategies for optimizing rearing conditions, given that microbiota interact within the BSF gut to influence host digestion, immunity, and waste processing efficiency (Auger et al., 2025). Inoculating rearing substrates with beneficial microbes or selecting for microbial profiles associated with improved waste degradation could enhance system performance.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Funding

This material is based upon work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant Nos. 1746932, 2052565, 2052788, 2052454. Any opinion, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. In addition, this work was partially funded by the Entomological Society of America Systematics and Evolutionary Biology Section Student Research Travel Award.:

Acknowledgments

Thank you to our anonymous reviewers who helped revise the manuscript; to Ronald Vargas Castro, Spence Behmer, Hojun Song, Stephanie Guzman-Valencia, Brenda Galvan, Susan Albor, and Alice Diaz Chauvigne for help and encouragement during the permitting process, to Bill Eberhard, Bill Wcislo, and Flavia Barbosa for advice on how to locate stratiomyids in the wild; again to Ronald Vargas Castro as well as to Eugenio Gonzalez, Johan Rodriguez, Noylin Rodriguez, Vivian Samora Santamaria and the rest of the Soltis Center for guidance during fieldwork, and lastly the locals of San Juan and the staff of Finca Luna for being enthusiastic about our work and helping to make it a success.

References

- Alcock, J. A large male competitive advantage in a lekking fly, Hermetia comstocki Williston (Diptera: Stratiomyidae). Psyche: A Journal of Entomology 1990, 97, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcock, J. Possible causes of variation in territory tenure in a lekking pompilid wasp (Hemipepsis ustulata) (Hymenoptera). Journal of Insect Behavior 2000, 13, 439–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcock, J.; Gwynne, D.T.; Dadour, I.R. Acoustic signaling, territoriality, and mating in whistling moths,Hecatesia thyridion (Agaristidae). Journal of Insect Behavior 1989, 2, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancona, S.; Dénes, F.V.; Krüger, O.; Székely, T.; Beissinger, S.R. Estimating adult sex ratios in nature. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2017, 372, 20160313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, D.; Pasini, F.; Scarano, F.R. Syntropy and innovation in agriculture. Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 2020, 45, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auger, L.; Tegtmeier, D.; Caccia, S.; Klammsteiner, T.; De Smet, J. BugBook: How to explore and exploit the insect-associated microbiome 2025. [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, F. An integrative view of postcopulatory sexual selection in a soldier fly: Interplay between cryptic male choice and sperm competition. In Cryptic Female Choice in Arthropods: Patterns, Mechanisms and Prospects; Peretti, A. V., Aisenberg, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing, 2015; pp. 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, T.M.; Jales, J.T.; Medeiros, J.R.; Gama, R.A. Sarcosaprophagous dipterans associated with differentially-decomposed substrates in Atlantic Forest environments. Acta Brasiliensis 2023, 7, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, M.; Chia, S.Y.; Fischer, B.; Tomberlin, J.K. Welfare considerations for farming black soldier flies, Hermetia illucens (Diptera: Stratiomyidae): a model for the insects as food and feed industry. Journal of Insects as Food and Feed 2022, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, M.; Patel, N.; McCarry, B.; Shellenberger, G.; Schwartz, E.; Fiocca, K.; Waddell, E. Dietary preferences and impacts of feeding on behavior, longevity, and reproduction in adult black soldier flies (Diptera: Stratiomyidae; Hermetia illucens). Journal of Insects as Food and Feed 2025, Online, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beehler, B.M.; Foster, M.S. Hotshots, hotspots, and female preference in the organization of lek mating systems. The American Naturalist 1988, 131, 203–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beenakkers, A.M. Th.; Van der Horst, D.J.; Van Marrewijk, W.J.A. Insect flight muscle metabolism. Insect Biochemistry 1984, 14, 243–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booth, D.C.; Sheppard, C. Oviposition of the black soldier fly, Hermetia illucens (Diptera: Stratiomyidae): Eggs, masses, timing, and site characteristics. Environmental Entomology 1984, 13, 421–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, J.; Gibson, R.; Tsai, I.M. Hotspots and the dispersion of leks. Animal Behaviour 1986, 34, 1694–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradbury, J.W.; Gibson, R.M. Leks and mate choice. In Mate Choice; Bateson, P., Ed.; Cambridge University Press, 1983; pp. 109–140. [Google Scholar]

- Breviglieri, C.P.B.; Romero, G.Q.; Mega, A.C.G.; da Silva, F.R. Are Cecropia trees ecosystem engineers? The effect of decomposing Cecropia leaves on arthropod communities. Biotropica 2019, 51, 562–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.S.; Laundré, JW; Gurung, M. The ecology of fear: Optimal foraging, game theory, and trophic interactions. Journal of Mammalogy 1999, 80, 385–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, D.; Bonelli, M.; Cadamuro, A.G.; Reguzzoni, M.; Grimaldi, A.; Casartelli, M.; Tettamanti, G. The digestive system of the adult Hermetia illucens (Diptera: Stratiomyidae): Morphological features and functional properties. Cell and Tissue Research 2019, 378, 221–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzatto, B.A.; Machado, G. Resource defense polygyny shifts to female defense polygyny over the course of the reproductive season of a Neotropical harvestman. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 2008, 63, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, C.; Coulouris, G.; Avagyan, V.; Ma, N.; Papadopoulos, J.; Bealer, K.; Madden, T.L. BLAST+: Architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 2009, 10, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiabotto, C.; Grosso, F.; Doretto, A.; Meneguz, M. Observation of mating behavior using marked flies of black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) under sunlight condition. Journal of Insects as Food and Feed 2024, 10, 2017–2029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copello, A. Biologia de Hemetia illuscens Latr. (La mosca de nuetras colmenas). Revista de La Sociedata Entomologica Argentina 1926, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Cornaby, B.W. Carrion reduction by animals in contrasting tropical habitats. Biotropica 1974, 6, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, G.D.P.; Hesselberg, T. A review of the use of black soldier fly larvae, Hermetia illucens (Diptera: Stratiomyidae), to compost organic waste in tropical regions. Neotropical Entomology 2020, 49, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, S.; Studt Solano, N.M.; Roa Gutiérrez, F.; Zurbrügg, C.; Tockner, K. Biological treatment of municipal organic waste using black soldier fly larvae. Waste and Biomass Valorization 2011, 2, 357–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dodson, G. Lek mating system and large male aggressive advantage in a gall-forming tephritid fly (Diptera: Tephritidae). Ethology 1986, 72, 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emlen, S.T.; Oring, L.W. Ecology, sexual selection, and the evolution of mating systems. Science 1977, 197, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fachin, D.A.; González, C.R.; Elgueta, M.; Hauser, M. A catalog of Stratiomyidae (Diptera: Brachycera) from Chile, with a new synonym and notes on the species. Zootaxa 2021, 5004, 1–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fachin, D.A.; Hauser, M. Large flies overlooked: The genus Hermetia Latreille, 1804 (Diptera: Stratiomyidae) in the Neotropics, with 11 synonyms and a new species to Brazil. Neotropical Entomology 2022, 51, 660–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, J.; Wang, J.; Huang, X.; Guan, B.; Feng, Q.; Deng, H. Composition and diversity of gut microbiota across developmental stages of Spodoptera frugiperda and its effect on the reproduction. Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, D.P.; Young, R.D.; Catts Paul, E. Hermetia illucens (Linnaeus) as a Factor in the Natural Control of Musca domestica Linnaeus. Journal of Economic Entomology 1959, 52, 917–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasnier, T.R.; Magnusson, W.E.; Lima, A.P. Foraging activity and diet of four sympatric lizard species in a tropical rainforest. Journal of Herpetology 1994, 28, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giunti, G.; Campolo, O.; Laudani, F.; Palmeri, V. Male courtship behaviour and potential for female mate choice in the black soldier fly Hermetia illucens L. (Diptera: Stratiomyidae). Entomologia Generalis 2018, 38, 29–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harjoko, D.N.; Hua, Q.Q.H.; Toh, E.M.C.; Goh, C.Y.J.; Puniamoorthy, N. A window into fly sex: Mating increases female but reduces male longevity in black soldier flies. Animal Behaviour 2023, 200, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hastings, J.M.; Dodson, G.N.; Heckman, J.L. Male perch selection and the mating system of the robber fly,Promachus albifacies (Diptera: Asilidae). Journal of Insect Behavior 1994, 7, 829–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herberstein, M.E.; Painting, C.J.; Holwell, G.I. Scramble competition polygyny in terrestrial arthropods. In Advances in the study of behavior; Naguib, M., Podos, J., Simmons, L.W., Barrett, L., Healy, S.D., Zuk, M., Eds.; Elsevier, 2017; Vol. 49, pp. 237–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoc, B.; Noël, G.; Carpentier, J.; Francis, F.; Megido, R.C. Optimization of black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) artificial reproduction. PLOS ONE 2019, 14, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, L.; Hull, K.L.; Bierman, A.; Badenhorst, R.; Bester-van der Merwe, A.E.; Rhode, C. Patterns of genetic diversity and mating systems in a mass-reared black soldier fly colony. Insects 2021, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Höglund, J.; Alatalo, R.V. Leks; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- James, M.T. The genus Hermetia in the United States (Diptera: Stratiomyidae). Bulletin of the Brooklyn Entomological Society 1935, 30, 165–170. Available online: https://biostor.org/reference/169315.

- Jensen, K.; Thormose, S.F.; Noer, N.K.; Schou, T.M.; Kargo, M.; Gligorescu, A.; Nørgaard, J.V.; Hansen, L.S.; Zaalberg, R.M.; Nielsen, H.M.; Kristensen, T.N. Controlled and polygynous mating in the black soldier fly: Advancing breeding programs utilizing quantitative genetic designs 2025. [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, C.; Reim, C.; Blanckenhorn, W.U. Size-dependent insect flight energetics at different sugar supplies. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 2013, 108, 565–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, C.; Generalovic, T.N.; Ståhls, G.; Hauser, M.; Samayoa, A.C.; Nunes-Silva, C.G.; Roxburgh, H.; Wohlfahrt, J.; Ewusie, E.A.; Kenis, M.; Hanboonsong, Y.; Orozco, J.; Carrejo, N.; Nakamura, S.; Gasco, L.; Rojo, S.; Tanga, C.M.; Meier, R.; Rhode, C.; Sandrock, C. Global population genetic structure and demographic trajectories of the black soldier fly, Hermetia illucens. BMC Biology 2021, 19, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamis, F.M.; Ombura, F.L.O.; Akutse, K.S.; Subramanian, S.; Mohamed, S.A.; Fiaboe, K.K.M.; Saijuntha, W.; Van Loon, J.J.A.; Dicke, M.; Dubois, T.; Ekesi, S.; Tanga, C.M. Insights in the global genetics and gut microbiome of black soldier fly, Hermetia illucens: Implications for animal feed safety control. Frontiers in Microbiology 2020, 11. Available online: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2020.01538. [CrossRef]

- Kimsey, L.S. The behaviour of male orchid bees (Apidae, Hymenoptera, Insecta) and the question of leks. Animal Behaviour 1980, 28, 996–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klüber, P.; Arous, E.; Zorn, H.; Rühl, M. Protein- and carbohydrate-rich supplements in feeding adult black soldier flies (Hermetia illucens) affect life history traits and egg productivity. Life 2023, 13, Article 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotzé, Z; Tomberlin, J.K. Influence of substrate age and interspecific colonization on oviposition behavior of a generalist feeder, black soldier fly (Diptera: Straiomyidae), on carrion. Journal of Medical Entomology 2020, 57, 987–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozich, J.J.; Westcott, S.L.; Baxter, N.T.; Highlander, S.K.; Schloss, P.D. Development of a dual-Index sequencing strategy and curation pipeline for analyzing amplicon sequence data on the MiSeq Illumina sequencing platform. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2013, 79, 5112–5120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laudani, F.; Campolo, O.; Latella, I.; Modafferi, A.; Palmeri, V.; Giunti, G. Does Hermetia illucens recognize sibling mates to avoid inbreeding depression? Entomologia Generalis 2024, 44, 1225–1232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, N.B.; Dickerson, A.J.; Tomberlin, J.K. No neonates without adults. BioEssays 2023, 45, 2200162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, N.B.; Li, C.; De Smet, J.; Tomberlin, J.K. Temporal trends: Phase-shifted time-series analysis reveals highly correlated reproductive behaviors in the black soldier fly, Hermetia illucens (Diptera: Stratiomyidae) (p. 2025.08.26.672371). bioRxiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, N.B.; Li, C.; Dickerson, A.J.; Salazar, D.A.; Rollinson, L.N.; Mendoza, J.E.; Miranda, C.D.; Crawford, S.; Tomberlin, J.K. Heterogeny in cages: Age-structure and attractant availability impacts fertile egg production in the black soldier fly, Hermetia illucens. Journal of Insects as Food and Feed. Online. 2025. [CrossRef]

- Lemke, N.B.; Rollison, L.N.; Tomberlin, J.K. Sex-specific perching: Monitoring of artificial plants reveals dynamic female-biased perching behavior in the black soldier fly, Hermetia illucens (Diptera: Stratiomyidae). Insects 2024, 15, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemke, N.; Puniamoorthy, N. Beyond the Black Box: Reproductive Strategies of the Black Soldier Fly as a Model for Bridging Evolutionary Biology and Applied Entomology. Biology and Life Sciences 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, S.L. Predators and the breeding bird: Behavioral and reproductive flexibility under the risk of predation. Biological Reviews 2009, 84, 485–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lloyd, L. The game birds and wild fowl of Sweden and Norway: With an account of the seals and salt-water fishes of those countries; F. Warne and Company, 1867. [Google Scholar]

- Manas, F.; Labrousse, C.; Bressac, C. Plastic responses in sperm expenditure to sperm competition risk in black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens, Diptera) males. Journal of Insect Physiology 2025, 161, 104751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manas, F.; Piterois, H.; Labrousse, C.; Beaugeard, L.; Uzbekov, R.; Bressac, C. Gone but not forgotten: Dynamics of sperm storage and potential ejaculate digestion in the black soldier fly Hermetia illucens. Royal Society Open Science 2024, 11, 241205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manas, F.; Venon, P.; Yang, L.; Labrousse, C.; Bressac, C. Multiple mating is not driven by size and sperm management in black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens). Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 2025, 173, 815–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munsch-Masset, P.; Labrousse, C.; Beaugeard, L.; Bressac, C. The reproductive tract of the black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) is highly differentiated and suggests adaptations to sexual selection. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata 2023, n/a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muraro, T.; Lalanne, L.; Pelozuelo, L.; Calas-List, D. Mating and oviposition of a breeding strain of black soldier fly Hermetia illucens (Diptera: Stratiomyidae): polygynandry and multiple egg-laying. Journal of Insects as Food and Feed 2024, 1(aop), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, K.R. The bionomics of blow flies. Annual Review of Entomology 1965, 10, 47–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyakeri, E.M.; Ogola, H.J.O.; Ayieko, M.A.; Amimo, F.A. Valorisation of organic waste material: Growth performance of wild black soldier fly larvae (Hermetia illucens) reared on different organic wastes. Journal of Insects as Food and Feed 2017, 3, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oonincx, D.G.A.B.; Volk, N.; Diehl, J.J.E.; van Loon, J.J.A.; Belušič. G Photoreceptor spectral sensitivity of the compound eyes of black soldier fly (Hermetia illucens) informing the design of LED-based illumination to enhance indoor reproduction. Journal of Insect Physiology 2016, 95, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owings, C.G. Developmental plasticity of Cochliomyia macellaria Fabricius (Diptera: Calliphoridae) from three distinct ecoregions in Texas. PhD Thesis. 2012. Available online: https://oaktrust.library.tamu.edu/items/093ad7a9-ca1d-49d5-b3d1-8cf965af9a20.

- Owings, C.G.; Banerjee, A.; Asher, T.M.D.; Gilhooly, W.P.; Tuceryan, A.; Huffine, M.; Skaggs, C.L.; Adebowale, I.M.; Manicke, N.E.; Picard, C.J. Female blow flies as vertebrate resource indicators. Scientific Reports 2019, 9, 10594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, E.O. Animal domestication and behavior; CABI Pub, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rathore, A.; Isvaran, K.; Guttal, V. Lekking as collective behaviour. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 2023, 378, 20220066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]