1. Introduction

Since the early 2000’s the term ‘nano’ gained increasing interest in the scientific community and subsequently in the area of standardization and regulation. There are numerous definitions of nanomaterials (NM) e.g. in technical specifications by ISO [

1], on a general regulatory level like the EU Commission Recommendation on the definition of nanomaterials [

2], or in application driven regulations like in the novel food regulation [

3]. Detailed explanations on the interpretation of the EU commission recommendation and principles on how to measure nano-specific characteristics have been elaborated by the Joint Research Center of the European Commission (JRC) [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

While it is generally accepted by regulators, that the term ‘nano’ does not automatically imply any hazard [

9], concerns are raised based on the novelty and potentially unknown properties of nanomaterials.

The novel properties found for certain nanomaterials and the new nomenclature led to the impression that NMs generally can be regarded as ‘novel materials’ with unique properties differentiating them from traditional materials with the same chemical composition, which do not exhibit a nanostructure. However, this is true only for some newly developed materials which fall under the different NM definitions. There are other examples of NMs and nanostructured materials which have been produced since many decades (e.g., SAS, carbon black, some types of titania), centuries (e.g., gold ruby glass) or even millennia (e.g., clay). Even nanosilver, a material which is frequently discussed nowadays, exists for more than 100 years. (Nowack et al. 2011) [

10]. These materials can fall under the different definitions of NMs although they are on the market long before the term ‘nano’ was introduced in the scientific community, or in regulations. The present paper summarizes briefly the history of innovation, manufacturing and marketing of SAS and cites references where the ‘nano’ property of SAS can be traced back to the beginning of its production.

2. Brief Overview on the History of Silica Production

It dates back to 1941 when Degussa chemist Harry Klöpfer was looking for an active, light-colored reinforcing filler to replace rubber carbon blacks. Using silicon tetrachloride in a flame process (similar to the production of carbon black) led to the production of AEROSIL

®, the first pyrogenic silica. Due to the similarities in application and production, it was also referred to as ‘white carbon black’, a name still used in Chinese today. The year 1944 laid the foundation for the first production plant of AEROSIL

® in Rheinfelden, Germany. Since then, the production of pyrogenic silica from Degussa has expanded to various places all over the world over the years. Other manufacturers of pyrogenic silica appeared on the market and produced according to the patented process from Degussa [

11]. In 1958 Cabot Corp. started the production of pyrogenic silica, Wacker followed in the 1960’s. From there on pyrogenic silica has found its way in many industries like rubber, plastics, coatings, pharma, food and feed, providing effects such as reinforcement, thickening, free-flow, anticaking or matting [

12].

The success story with precipitated silicas (another production route for SAS) began in the 1950s. In 1951 chemist Dr. Hans Verbeek and his assistant Peter Nauroth developed a process for precipitated silica, hence ‘VN’ still visible in some of today’s product names. From the year 1953, precipitated silica was marketed under the trade name ‘ULTRASIL

®’. Large amounts of ULTRASIL

® VN 3 were in production for high-quality rubber goods, also enabling the creation of colored rubber compounds. Even before the introduction of ULTRASIL

® VN 3, Aluminum Silicate AS 7 was used as filler [

13]. 1952, Interchemical Corporation, was granted a patent on a precipitated silica type as under specific reaction conditions leading to a “soft silica powder” with submicron structures to be detected in the electron microscope [

14]. Also in the 1950’s Columbia Southern Chemical Corporation filed several patents on precipitated silica with a specific surface area of 25 – 200 m²/g and submicron structures, which can be seen in electron microscope images [

15,

16,

17,

18].

In 1979 Iler provided an overview on commercially available types of synthetic amorphous silica, both from the precipitated and the pyrogenic production route, listing 14 different producers and 88 commercial grades with a specific surface area between 50 and 720 m²/g, which shows the rapid development of this product group during this time [

19].

Figure 1.

Snippet from a brochure dating back to the early 1950s introducing the name ‘white carbon black’ for AEROSIL®.

Figure 1.

Snippet from a brochure dating back to the early 1950s introducing the name ‘white carbon black’ for AEROSIL®.

Figure 2.

Snippet from a brochure from 1955, describing the thickening properties of AEROSIL® in polyester resins.

Figure 2.

Snippet from a brochure from 1955, describing the thickening properties of AEROSIL® in polyester resins.

3. Particle Size and Structure of Synthetic Amorphous Silica

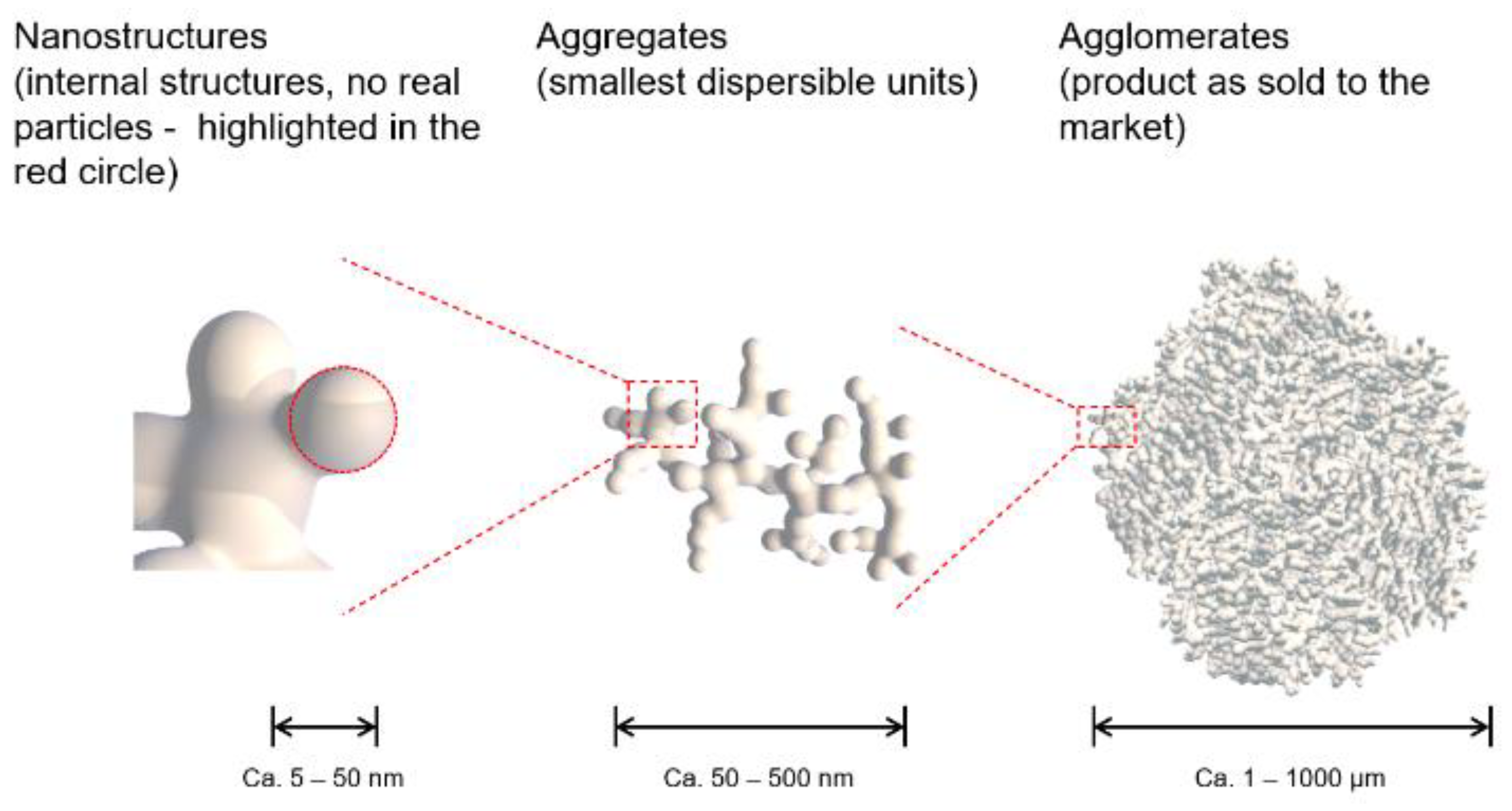

3.1. Overview on the Different Levels of Structure in SAS

All synthetic amorphous silica types - pyrogenic (fumed) silica, precipitated silica and silica gel - are nanostructured materials. The particle size distribution of SAS is characterized by different levels of structure, namely nanostructures (in some publications referred to as constituent particles or primary particles), aggregates, and agglomerates. This complex structure is caused by the production process. The particles that initially form in the production process are spherical primary particles in the nanometer range. These initial primary particles are fused within a short time frame in the production process to form aggregates via covalent bonds. The size and shape of the former primary particles still can be adumbrated in TEM (Transmission Electron Microscope) pictures but there are no physical boundaries between these former primary particles anymore [

20]. Thus, the aggregate can be considered the smallest particle with defined boundaries. The former primary particles have lost their physical identity and just can be regarded as nanostructures inside the aggregate. Aggregates then further combine to agglomerates via physical bonds and the agglomerates are the particle size in which synthetic amorphous silica is marketed. It should be noted that almost identical structures as seen in SAS can also be found in biogenic amorphous silica (BAS) which e.g. can be found in common horsetail and oat husk [

21].

Figure 3.

Different structural levels of Synthetic Amorphous Silica (SAS).

Figure 3.

Different structural levels of Synthetic Amorphous Silica (SAS).

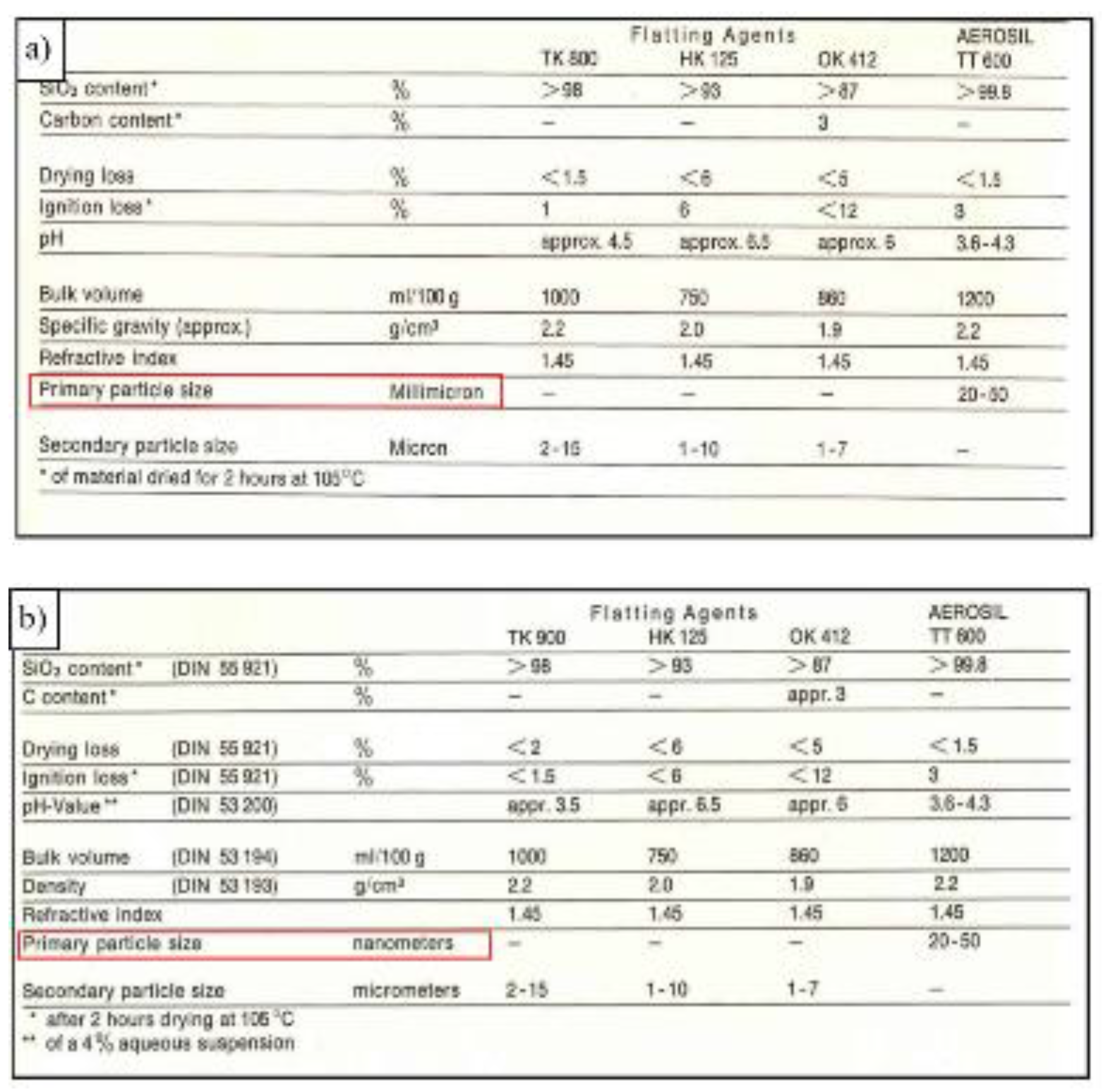

Historical documents from Evonik Industries and its predecessor companies (namely Degussa) show that the same structural elements could be detected in SAS from the first time of production onwards. However, the term ‘nanometer’ was not introduced in documents on SAS until the early 1970’s. Before that, the particle sizes at the submicron scale were expressed in the units of ‘millimicron’.

Figure 4 shows extracts from brochures dated back from 1970 and 1975, the change from the wording ‘millimicron’ to ‘nanometer’ happened between these dates [

22,

23].

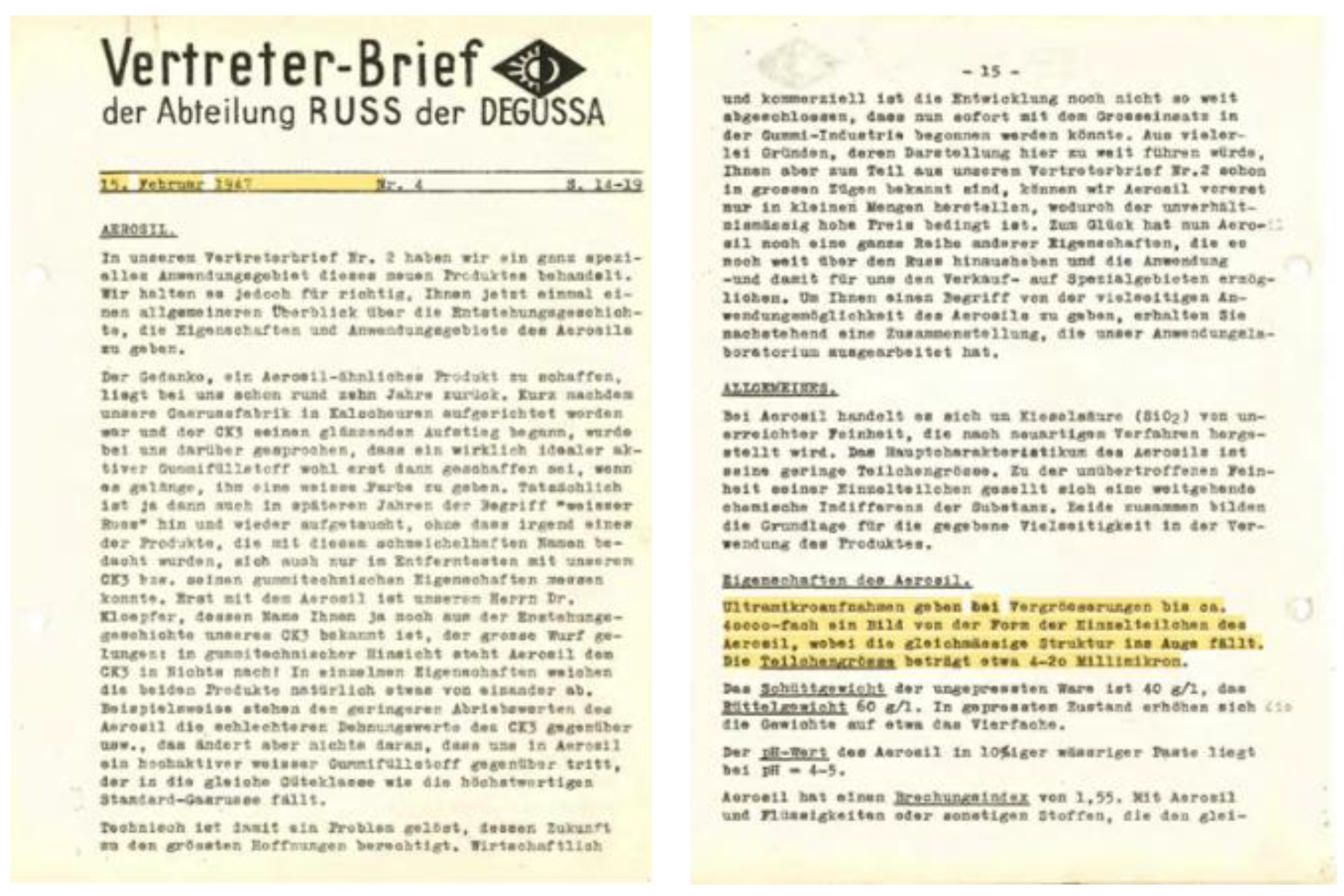

One of the oldest pieces of evidence to prove that SAS is a nanostructured material since the beginning of its production was found in a publication from 1947 titled ‘Vertreter-Brief der Abteilung RUSS der DEGUSSA’ (

Figure 5) [

24]. As per the document, the idea to create AEROSIL

® started with efforts to make an ideal active rubber filler with a white color. The ultrafine particles give the AEROSIL

® product its versatility in terms of possible applications. The primary particle / nanostructure size of these particles is reported as 4-20 millimicrons (= nanometers). In terms of technical properties, AEROSIL

® was explained to be in no way inferior to carbon black thus the term ‘white carbon black’ emerged as a name for AEROSIL

® in the initial years of development [

25].

3.2. Nanostructures

Nanostructures of SAS only can be visualized and measured by electron microscope techniques such as SEM (Scanning Electron Microscope) or TEM (Transmission Electron Microscope). TEM was invented in the 1930’s and one of the first electron microscopes in Germany was installed in Degussa’s Laboratories. While the technology development over the years has improved the resolution and quality of the images, it was already possible to detect the nanostructures within AEROSIL

® even with the first TEM devices. When comparing the TEM images from different periods, it is obvious that the structure of silica essentially has not changed at all.

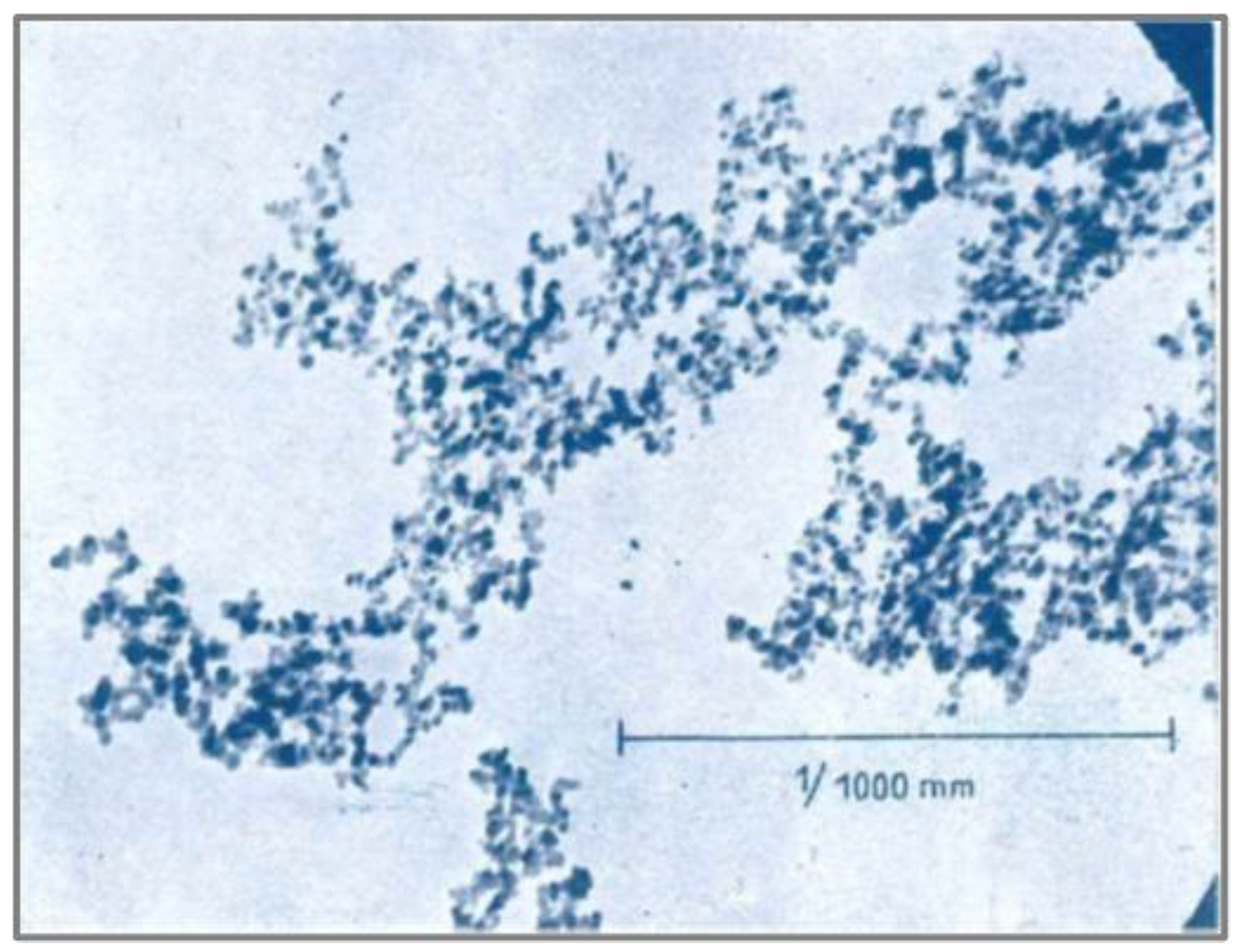

Figure 6 displays the oldest TEM image of AEROSIL

® found during our literature search from 1948. The image is published in a pamphlet titled ‘AEROSIL

® – Degussa’[

26]. It mentions the ‘primary particle size’ as 4-20 ‘millimicrons’ and the surface area (BET) as 300-350 m

2/g. This suggests that the grade of this fumed silica is equivalent to today’s grade AEROSIL

® 300. The image displays the structure with a scale bar of 1 μm. Modern-day TEMs can show images at much greater resolution.

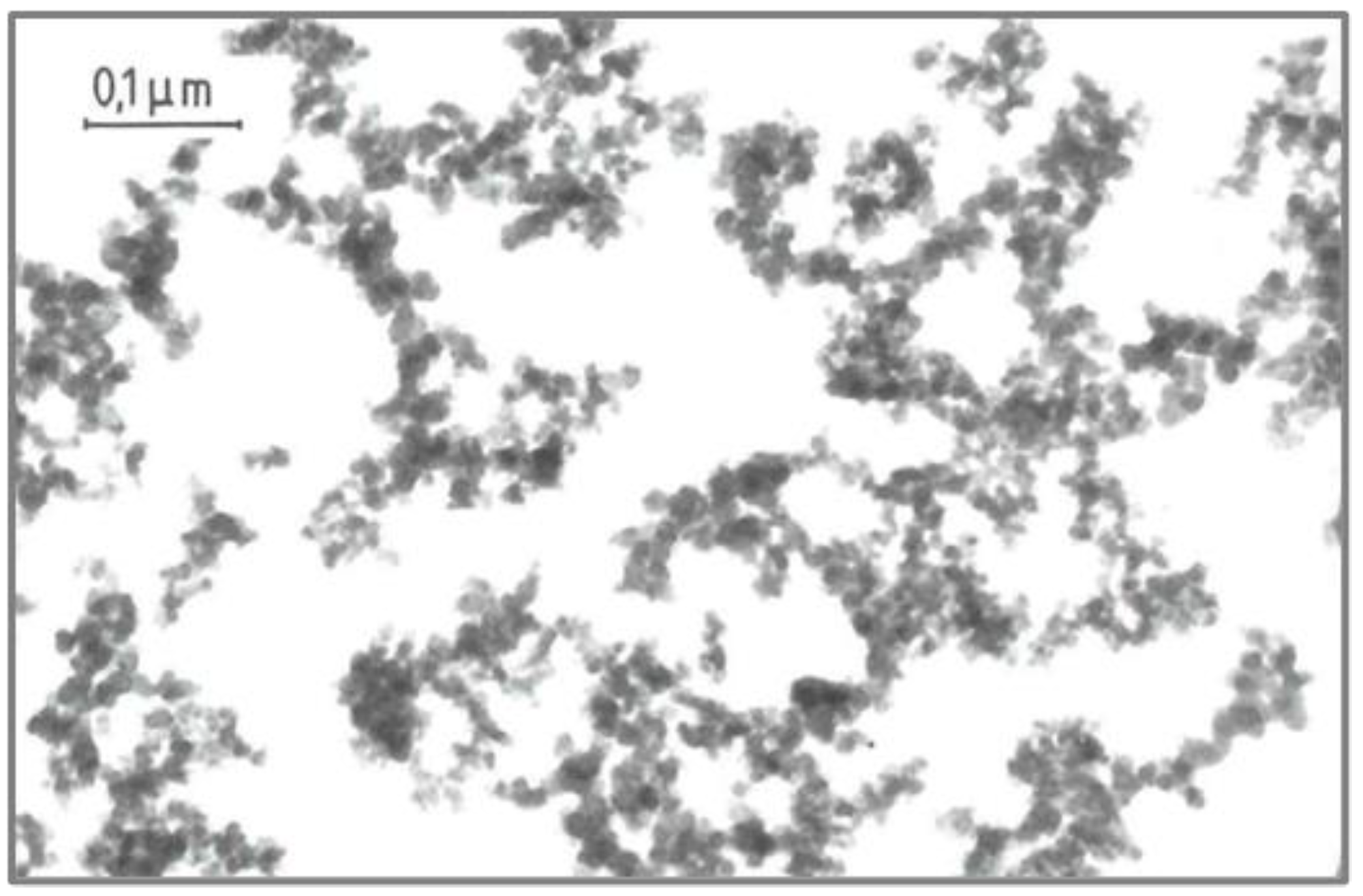

Figure 7 shows a TEM image of AEROSIL

® 380 published in the year 2006 [

27]. The scale bar of the image is 0.1 μm or 100 nm. The small spheroidal structures in both images represent the nanostructures of AEROSIL

® fumed silica. It can be seen that these structures are fused to aggregates. Modern TEM equipment allows even better resolution and proves that there are no phase boundaries between the nanostructures within SAS [

20].

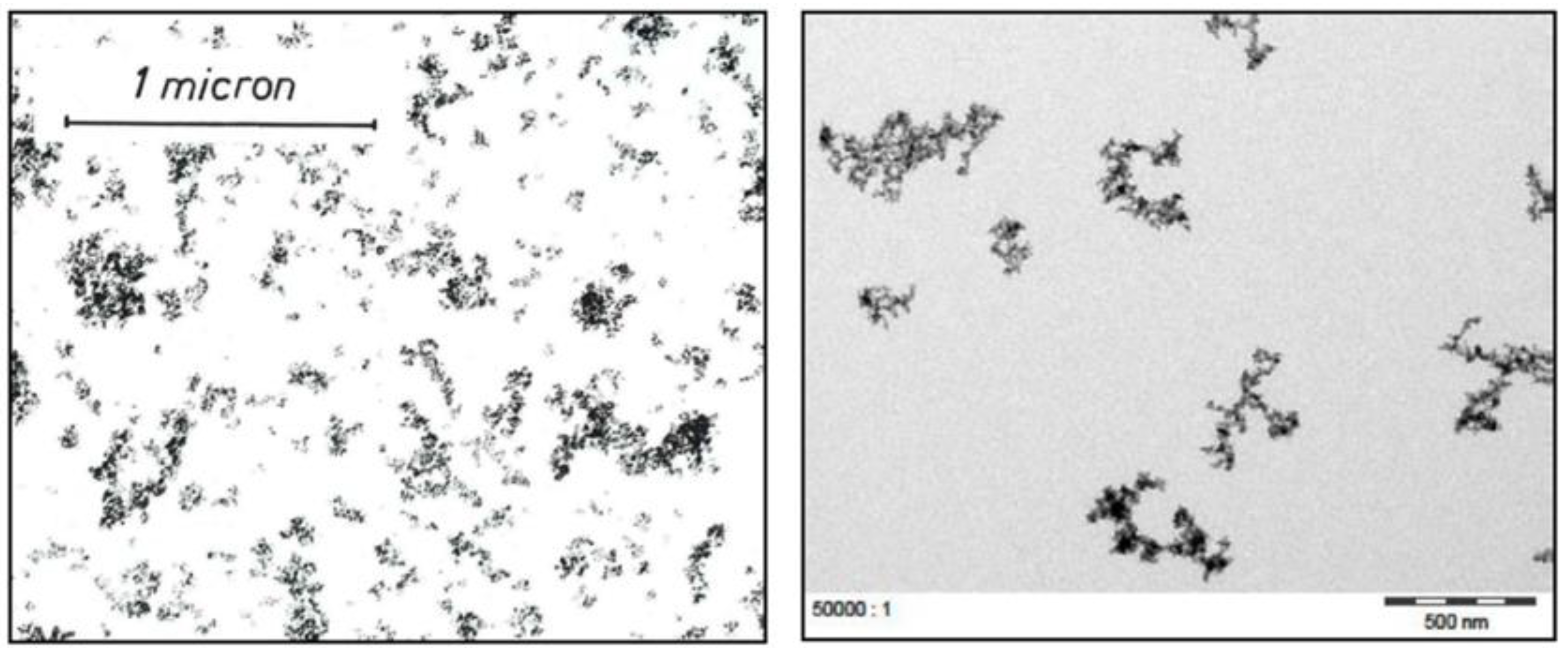

Another historic example is provided in

Figure 8, which compares a TEM image from the year 1971 of AEROSIL

® 200 with a TEM image from a report issued in 2016 that shows AEROSIL

® 200 Pharma [

28].

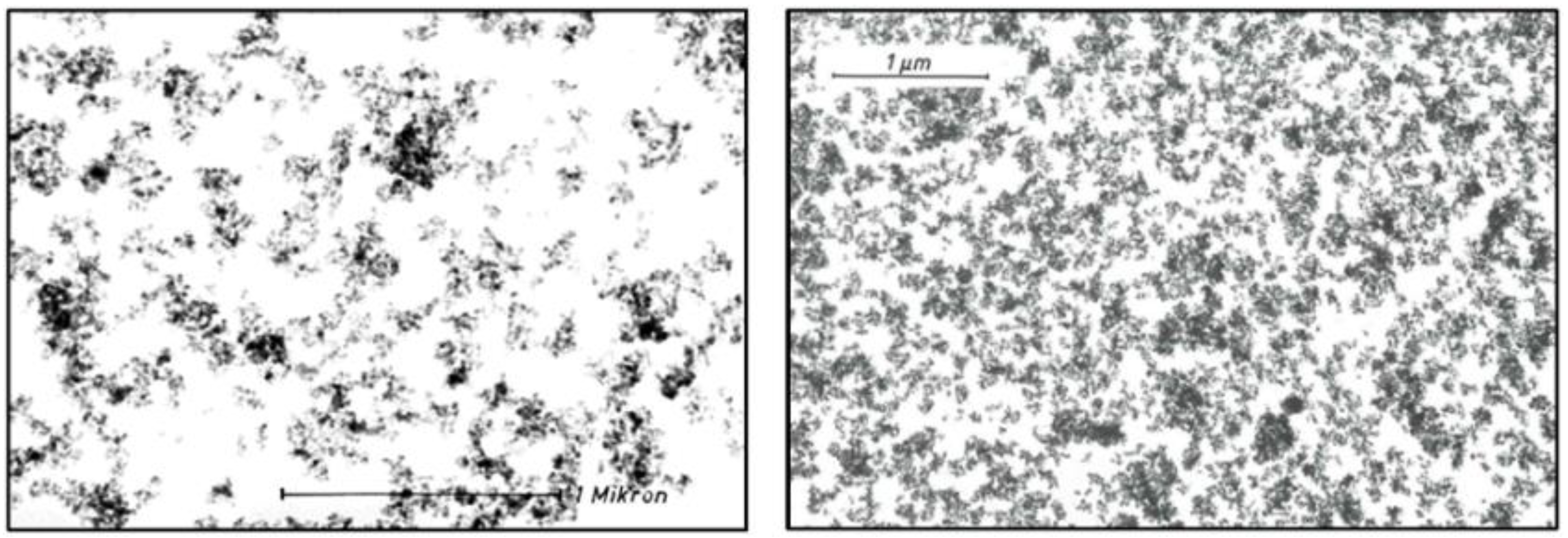

Precipitated silica differs from fumed silica not just by the production process but also by the morphology of agglomerates, which exhibit a denser, sponge-like structure, leading to higher bulk and tamped densities. Nevertheless, precipitated silica is also composed of the same basic levels of structure, i.e. nanostructures, aggregates and agglomerates. As for pyrogenic silica this morphology has been essentially the same since the earliest production of precipitated silica. An example is provided in

Figure 9 comparing TEM pictures of ULTRASIL

® VN 3 from 1969 and from 1982. The TEM images of this precipitated grade of SAS reveal a denser structure than found for AEROSIL

® fumed silica. However, the structure of silica has continued to remain the same throughout the years [

29,

30].

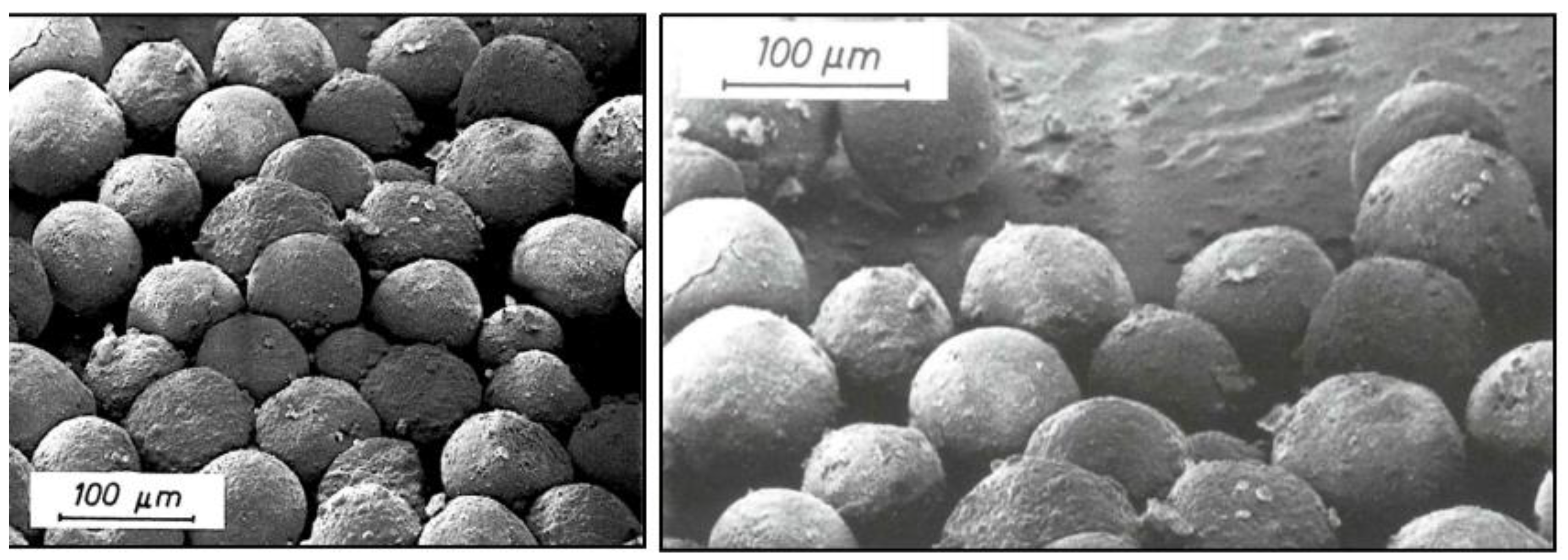

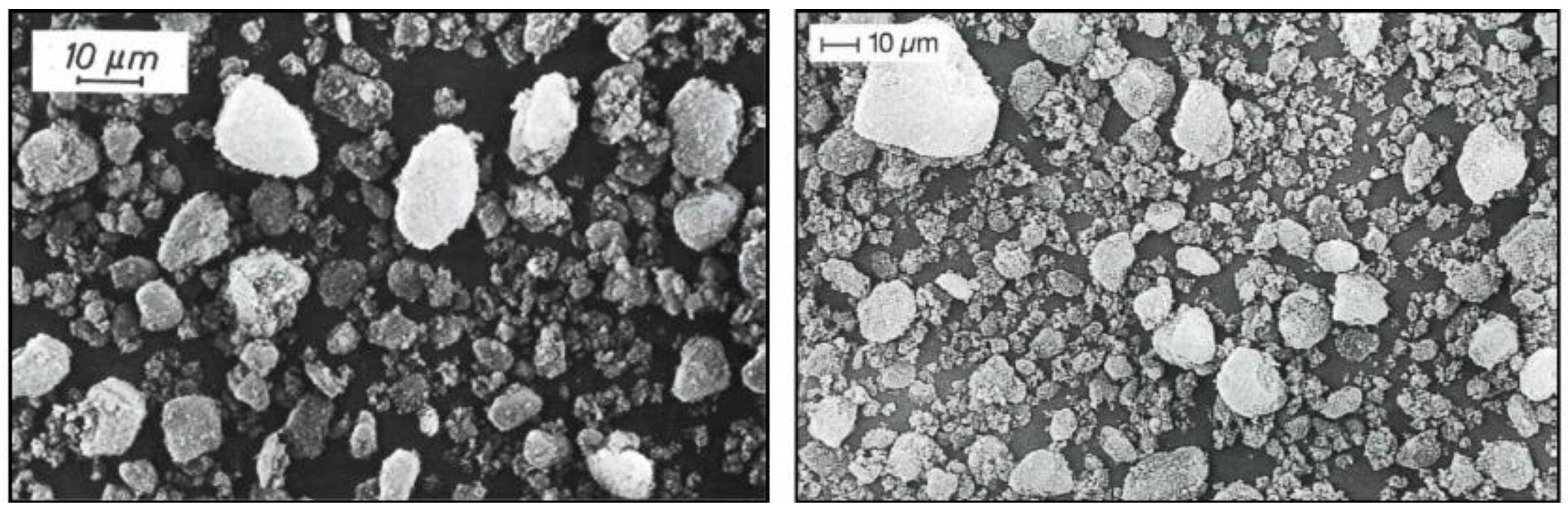

3.3. Aggregates and Agglomerates

To visualize the 3-dimensional aggregate and agglomerate structure of SAS, Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) is more suitable than TEM. In particular, for precipitated SAS the aggregate and agglomerate structure is of high relevance for the application of these materials. Some examples can be derived from spray-dried precipitated SAS grades such as SIPERNAT

® products. These materials consist of largely porous spherical agglomerates with sizes of 50 μm to 320 μm and are characterized by a very good adsorptive capacity for liquids. SEM Images from 1985 and 2004 display the same structures (

Figure 10). This indicates that also at the level of agglomerates the structure of SAS has not changed throughout the years [

31,

32,

33]. The same can be shown for SAS products used as matting agents such as HK 125. The SEM pictures in

Figure 11 are taken from publications from 1985 and 1996 and reveal the same agglomerate structure [

34,

35].

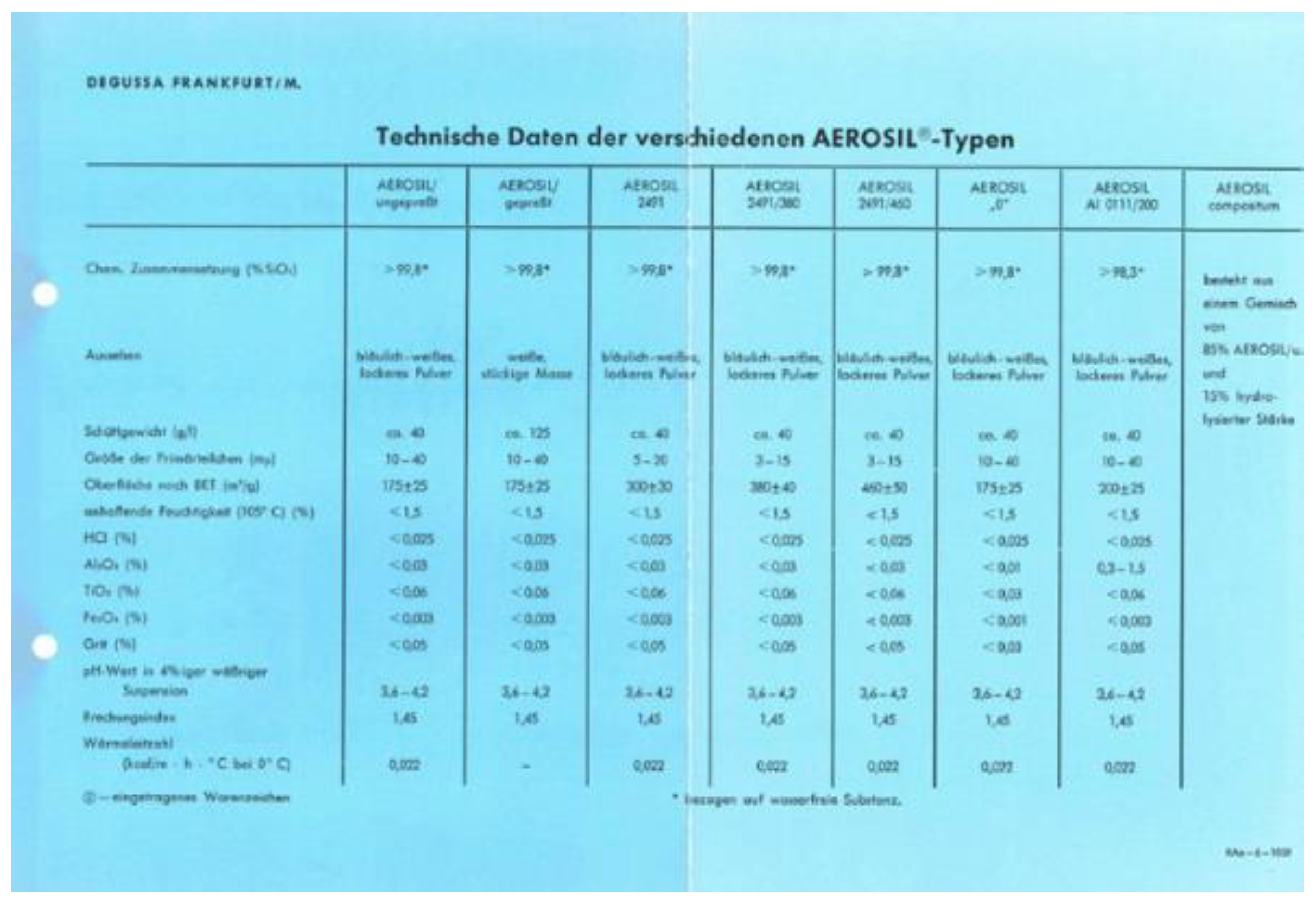

3.4. Other Characteristics of SAS

Besides these qualitative comparisons of microscopic pictures, it is worth to analyse the numbers of characteristic properties of SAS published over time such as ‘primary particle’ sizes (nowadays reported as nanostructures), secondary particle sizes (aggregates and agglomerates), BET (Brunauer–Emmett–Teller) surface area, pH value, moisture adsorbed value, ignition loss, tapped densities, and impurity concentrations. Typical values can be found with only little differences in the published brochures over time. Only minor differences occur and can be explained as analytical methods for these properties have certainly improved over the years. As a result, when a more accurate value was calculated, an updated version of the publication was released with an updated value. An early example with technical data listed for AEROSIL

® types dates back to 1959 [

36] and shows only minor differences to today’s product specifications. The analytical methods can e.g. be studied in detail from the publication ‘Technical Bulletin Pigments Number 16: Analytical Methods for Synthetic Silicas and Silicates’ [

37].

Figure 12.

Technical data sheet of different AEROSIL® products published 1959.

Figure 12.

Technical data sheet of different AEROSIL® products published 1959.

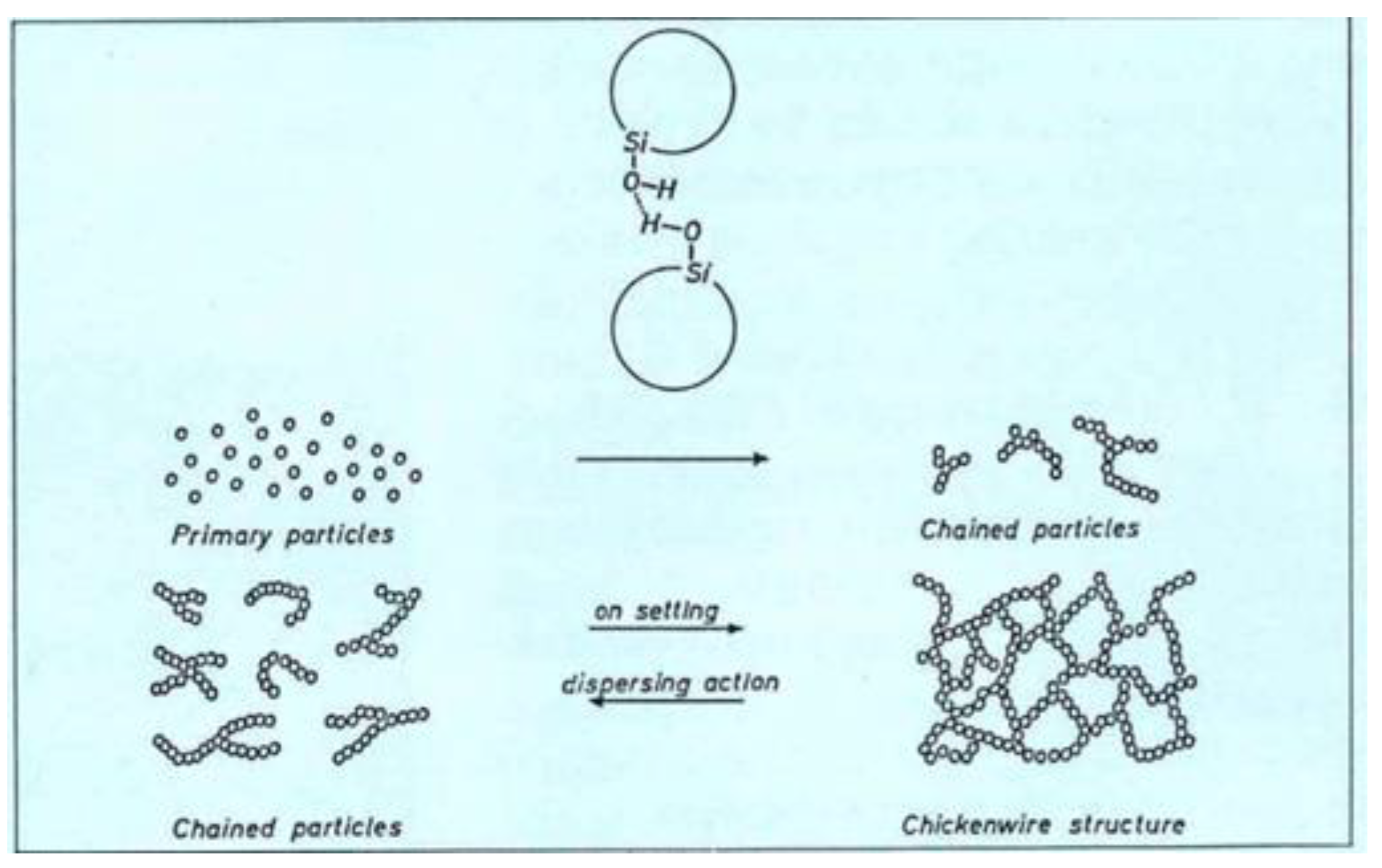

AEROSIL

® fumed silica has been produced over the years with specific areas of 50-400 m

2/g measured according to the BET method. AEROSIL

® grades exhibit fractal aggregates with chained elements at the end. In publications dating back to the 1970’s it is described that in dispersions, these can form “chickenwire” structures (from today’s perspective these structures should be described rather as 3-dimensional network). This property is utilized to increase the viscosity in liquids and thus causes thickening [

11,

38]. Precipitated silica, like SIPERNAT

®, on the other hand, exhibits more compact aggregates which form sponge-like agglomerates.

Figure 13.

Snippet from a brochure from 1974 describing the buildup of viscosity through the connection of chain-formed AEROSIL® aggregates.

Figure 13.

Snippet from a brochure from 1974 describing the buildup of viscosity through the connection of chain-formed AEROSIL® aggregates.

3.5. Safety of SAS

Former published epidemiological studies indicate no specific toxicological effect of SAS in humans under former and current exposure situations at the workplace [

39]. The available epidemiological studies have recently been reviewed confirming the lack of adverse effects in occupationally exposed persons (Antoniou et al. (2023)) [

40]. From early on industry has accompanied the production of SAS with extensive toxicological studies confirming its safety. As early as the 1950s, elaborate inhalation experiments were carried out with animals, which showed that even high concentrations of synthetic amorphous silica do not cause lung diseases, as is known with crystalline quartz, for example [

41,

42,

43].

SAS has also been used in the consumer sector (food, feed, pharma, cosmetics) for decades and is considered safe. Recently, the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) has concluded that silicon dioxide as food additive (E 551) does not raise safety concerns at current usage levels for all population groups, including infants under 16 weeks of age (EFSA) [

44]. An extensive systematic review of the literature on synthetic amorphous silica supports the hypothesis of the very low toxicity of amorphous silica to humans and animals concluding that there is no reason for concern regarding the hazard of silica particles (Krug) [

45]. The existing toxicological assessments of silica are valid for the SAS grades on the market today including old studies, since silica has always been a nanostructured material and there are no "novel" nanoforms that would make it necessary to re-evaluate.

4. Application of Silica in Regulated Industries (Food, Feed, Cosmetics, Pharmaceuticals, etc.)

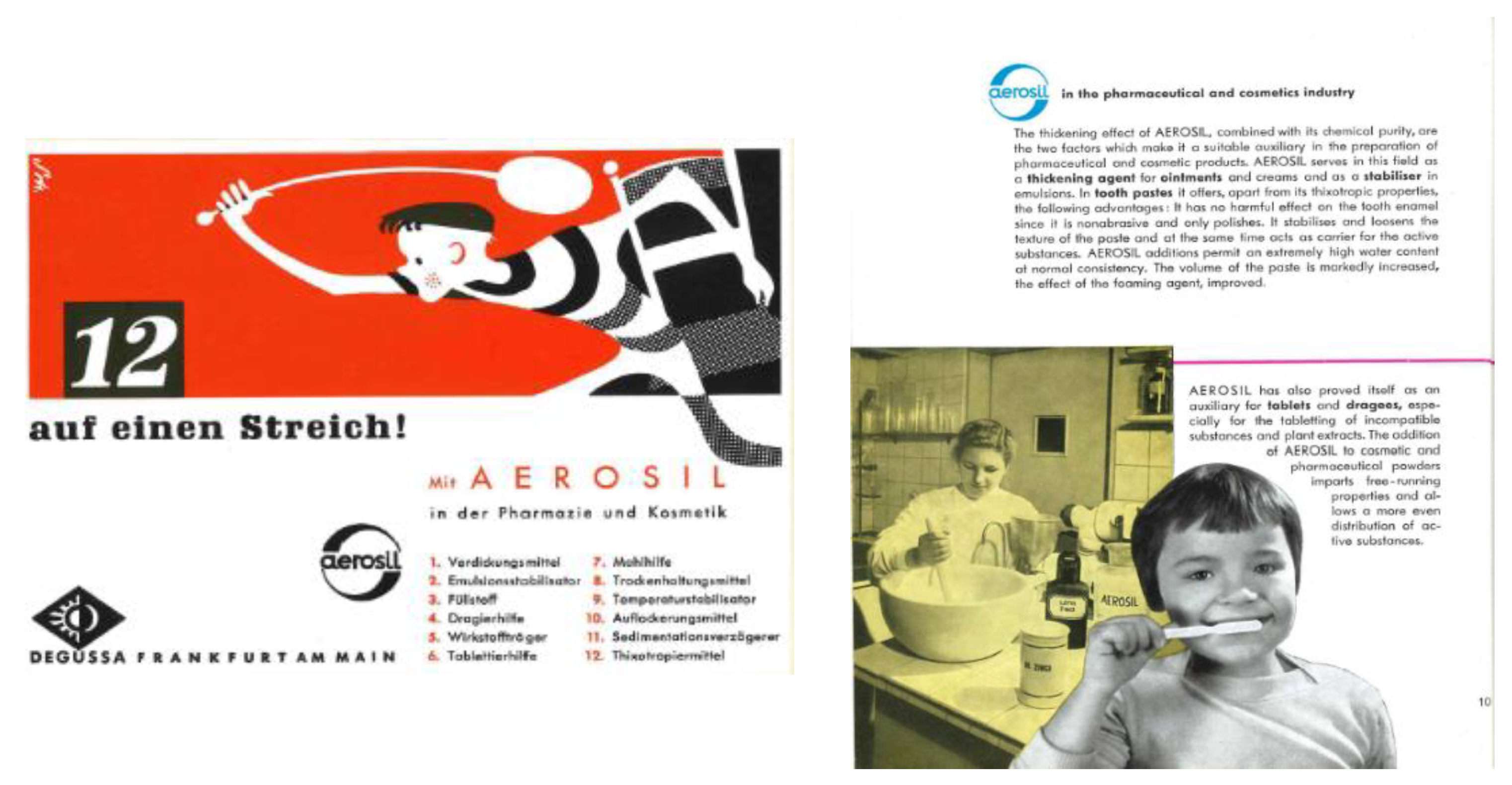

The physico-chemical properties of SAS have enabled them to be used in a broad variety of applications. Some of the fundamental applications of SAS include its use as a thickening agent and filler. Since the early years of production, it has been used in industries such as rubber, paints, coatings, plastics, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, adhesives, and many more. Among this long list, the application in the food industry, animal feed industry, cosmetics industry, and pharmaceutical industry requires separate attention due to the regulatory requirements. Pyrogenic silica like AEROSIL

® exhibit a strong thickening effect, combined with chemical purity making them an ideal auxiliary for use in pharmaceuticals and cosmetics application. In cosmetics, it can be used as a thickening agent for ointments and creams, and as a stabilizer in emulsions and toothpaste. AEROSIL

® has also found its use as a tableting aid and flow regulator in pharmaceutical applications for a long time. In a report from 1957 and in a brochure from 1960 the application of AEROSIL

® in pharmaceuticals and toothpastes was already described [

46,

47]. In an advertisement from 1961 numerous functions of AEROSIL

® in pharmaceuticals and cosmetics are described [

48]. All brochures of the companies Degussa, Evonik as well as product descriptions for the mentioned product grades are available on request.

Figure 14.

Advertisement from 1961, describing numerous functions of AEROSIL® in pharmaceuticals and cosmetics as well as in toothpaste.

Figure 14.

Advertisement from 1961, describing numerous functions of AEROSIL® in pharmaceuticals and cosmetics as well as in toothpaste.

Due to its sponge-like structure, precipitated SAS can absorb liquids and moisture and is used e.g. in the food industry as free-flow and anticaking agent in powder food or as absorbent to convert liquid additives into powders for animal feed applications. Pyrogenic silica also can be used in food additives and mainly serve as free-flow and anticaking agent, by acting as a spacer between the particles of food additives.

Documents dating back to 1964 report that SAS at that time was already permitted to be used in salts and in chewing gum. In a brochure from 1966 the use of AEROSIL

® as free-flowing agent and milling aid is described, confirming compliance with F.D.A. regulation Subpart D ‘Food Additives Permitted in Food for Human, Consumption’, § 121.1058 Silicon dioxide [

49].

5. Summary

Nanomaterials have been produced since long before the term ‘nano’ gained increasing interest in the scientific community. Examples are e.g. clay, gold ruby glass, carbon black, Synthetic Amorphous Silica (SAS), titania, or even nanosilver [

10].

For SAS there is a long history in the production and marketing, dating back to the early 1940s. During this long and successful history SAS found its way into a in a broad variety of applications, among them the usage in regulated industries such as food, feed, pharma, or cosmetics where consumer safety is of utmost importance. Early on toxicological testing by industry and regular approval processes confirmed its safety. From physico-chemical data and electron microscope imaging it could be proven that the earliest SAS products exhibited the same structure of SAS as nowadays. Research on ‘nanomaterials’ gained interest in the scientific community much later in the early 2000s and subsequently definitions and regulations on nanomaterials were developed. Thus, SAS is an example for a substance which has been produced as a nanomaterial long before anyone thought about nanomaterials or nanoscience.

The same nanostructures as for SAS can be found in its biogenic analogue BAS derived from different herbal sources. The formation of nanostructures happens almost unavoidably in the genesis of amorphous silica, driven by its chemical nature. Thus consequently, for amorphous silica ‘nano’ is normal and not a novel property. Regarding nanostructured SAS materials as entirely new chemicals with unknown properties, therefore is not justified. Policymakers and regulators should not overlook the extensive knowledge gained from our scientific and regulatory history with this material, in particular as it is generally accepted, that the term ‘nano’ does not automatically imply any hazard [

9].

Author Contributions

writing— original draft, Claus-Peter Drexel, Fahad Haider; writing - review and editing, Claus-Peter Drexel, Gottlieb-Georg Lindner, Magdalena Kern and Tobias Schuster; data curation, Fahad Haider.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to „Evonik Konzernarchiv“ for supporting the citation of relevant documents.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors are employees of Evonik Operations GmbH, a manufacturer of Synthetic Amorphous Silica (SAS).

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NM |

Nanomaterial |

| SAS |

Synthethic amorphous silica |

| BAS |

Biogenic amorphous silica |

| TEM |

Transmission Electron Microscopy |

| SEM |

Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| BET |

Surface area according to Brunauer, Emmet and Teller |

| EFSA |

European Food Safety Authority |

| F.D.A. |

US Food and Drug Administration |

References

- ISO: Technical specification: Nanotechnologies — Vocabulary - Part 1: Core terms, 2015.

- EU Commission: Recommendation on the definition of nanomaterial, 2022.

- Verordnung (EU) 2015/2283 des Europäischen Parlamentes und des Rates vom 25. November 2015 über neuartige Lebensmittel, 2015.

- Rauscher H, Roebben G, Mech A, Gibson N, Kestens V, Linsinger TPJ, et al. JRC Science for policy report - An overview of concepts and terms used in the European Commission’s definition of nanomaterial, 2019. [CrossRef]

- Rauscher H, Kestens V, Rasmussen K, Linsinger T, Stefaniak E. Guidance on the implementation of the commission recommendation, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen K, Rauscher H, Mech A, Riego Sintes J, Gilliland D, Gonzalez M, et al. Physico-chemical properties of manufactured nanomaterials - Characterisation and relevant methods. An outlook based on the OECD Testing Programme. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol. 2018; 92 (Supplement C): 8-28. [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen K, Riego Sintes J, Rauscher H. How nanoparticles are counted in global regulatory nanomaterial definitions. Nat Nanotechnol. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Rauscher H, Kobe A, Kestens V, Rasmussen K., Is it a nanomaterial in the EU? Three essential elements to work it out. Nano Today, 2023; 49. [CrossRef]

- De Jong W, Bridges J, Dawson K, Jung T, Proykova A, Chaudhry Q, et al. Scientific Basis for the Definition of the Term “nanomaterial” SCENIHR 2010. [CrossRef]

- Nowack B, Krug HF, Height M. 120 years of nanosilver history: implications for policy makers. Environ Sci Technol. 45(4) 2011; 1177-83. [CrossRef]

- Aerosil - Manufacture, Properties and Application Degussa AG; 1974.

- Aerosil Flyer. Frankfurt am Main: Degussa AG; 1955.

- 75 Jahre Chemische Fabrik Wessling: Degussa AG; 1955.

- Kumins CA, Greening GR, inventors; Interchemical Corp, Method of producing Silica Powder. USA, 1952.

- Allen EM; Columbia-Sothern Chemical Corporation, Silica Composition and Production Thereof. USA, 1952.

- Tornhill FS, Allen EM; Columbia-Southern Chemical Corporation, Pittsburgh, Pa., Verfahren zur Gewinnung feinzerteilter Kieselsäure. Germany, 1952.

- Tornhill FS; Pittsburgh Plate Glass Company, Procedure of preparing a finely divided silica. Switzerland, 1958.

- Tornhill FS; Columbia-Southern Chemical Corporation, assignee. Proceédé de préparation de silice finement divisée. Switzerland, 1953.

- Iler R.K. THE CHEMISTRY OF SILICA - Solubility, Polymerization, Colloid and Surface Properties, and Biochemistry: JOHN WILEY & SONS; 1979.

- Albers P, Maier M, Reisinger M, Hannebauer B, Weinand R. Physical boundaries within aggregates - differences between amorphous, para-crystalline, and crystalline Structures, Crystal Research and Technology, 50(11), 2015; 846-65.

- Lindner GG, Drexel C-P, Sälzer K, Schuster TB, Krueger N. Comparison of Biogenic Amorphous Silicas Found in Common Horsetail and Oat Husk With Synthetic Amorphous Silicas. Frontiers in Public Health. 10 2022. [CrossRef]

- Degussa Flatting Agents for Coating Industry Degussa AG; 1970.

- Degussa Flatting Agents for Coating Industry Degussa AG; 1975.

- Vertreter-Brief der Abteilung Russ der Degussa - Aerosil (Nr 1-15). 1947.

- Aerosil Flyers (particle size). 1937-1958.

- Aerosil - Degussa. Frankfurt am Main: Degussa AG; 1948.

- Basic Characteristics of Aerosil Fumed Silica, Technical Bulletin Fine Particles 11, Degussa AG, 2006.

- Degussa Pigments for Printing Inks, Schriftenreihe Pigmente 10, Degussa AG, 1971.

- Sprühgetrocknete Fällungskieselsäure K 322 (VN 3) - Lichtmikroskopische Untersuchung. 1969.

- Degussa Products for Cable Industry, Schriftenreihe Pigmente 5, Degussa AG, 1982.

- What are 'White Reinforcing Fillers': Degussa AG; 1977.

- SIPERNAT-ASPHALT, Schriftenreihe Pigmente, 46: Degussa AG; 1985.

- Synthetic Silica as a Flow Aid and Carrier Substance, Technical Bulletin Fine Particles 31, Degussa AG; 2004.

- ACEMATT Silicas for the Paint Industry, Schriftenreihe Pigmente 21, Degussa AG; 1996.

- Degussa Pigmente für die Lackindustrie, Schriftenreihe Pigmente 3, Degussa AG; 1985.

- Technische Daten der verschiedenen Aerosil-Typen - Technical Data. 1959.

- Analytical Methods for Synthetic Silicas and Silicates, Schriftenreihe Pigmente 16, Degussa AG; 1992.

- Ferch, H.; Basic Characteristics and Applications of a Silica produced by Flame Hydrolysis, Drugs Made in Germany, 13, 1970, 45-84.

- Taeger D, McCunney R, Bailer U, Barthel K, Kupper U, Bruning T, et al. Cross-Sectional Study on Nonmalignant Respiratory Morbidity due to Exposure to Synthetic Amorphous Silica. J Occup Environ Med. ; 58(4), 2016, 376-84. [CrossRef]

- Antoniou EE, Nolde J, Torensma B, Dekant W, Zeegers MP. Nine human epidemiological studies on synthetic amorphous silica and respiratory health. Toxicol Lett. 399, 2024, Suppl 1, 12-7. [CrossRef]

- Klosterkötter W. Tierexperimentelle Untersuchungen über die Retention und Elimination von Stäuben bei langfristiger Exposition. Beitr Silikose-Forsch 1963; S-Bd. Grundfragen Silikoseforsch.5, 417–36.

- Leuschner F. Über die chronische Toxizität von AEROSIL®. 1963.

- G.W.H. Schepers TMD, A.B. Delahant, F.T. Creedon, A.J. Redelin. The Biological Action of Degussa Submicron Amorphous Silica Dust (Dow Corning Silica). AMA Archives of industrial health. 1957.

- Younes M, Aquilina G, Castle L, Degen G, Engel KH, Fowler P, et al. Re-evaluation of silicon dioxide (E 551) as a food additive in foods for infants below 16 weeks of age and follow-up of its re-evaluation as a food additive for uses in foods for all population groups. EFSA Journal. 22 (10) 2024. [CrossRef]

- Krug HF. A Systematic Review on the Hazard Assessment of Amorphous Silica Based on the Literature From 2013 to 2018. Frontiers in Public Health. 2022; 10. [CrossRef]

- Aerosil and its applications: Degussa AG; 1960.

- Verwendungsmöglichkeiten von Aerosil in der pharmazeutischen Praxis. 1957.

- Aerosil - Flyers about Aerosil - applications and technical data. 1961.

- Aerosil Technical Data Sheet.pdf. 1966.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).