1. Introduction

The European Reference Networks (ERNs) [

1] represent a significant collaborative effort to improve the care for people with rare, complex and low-prevalence diseases in the European Union Member States and Norway. This is achieved through the generation and exchange of knowledge among different institutions. Unfortunately, the heterogeneity of data systems, formats, and standards across healthcare providers (HCPs), national registries, and ERNs presents a substantial barrier to achieving this vision. The Joint Action on the Integration of ERNs into National Healthcare Systems (JARDIN) [

2] has been working to facilitate the seamless flow of health data from its point of capture to its ultimate use, thus improving accessibility to ERNs by integrating them into National Healthcare Systems.

To identify potential solutions to prominent technical and semantic interoperability challenges, JARDIN’s Work Package 8 (WP8) - “Data Management” - convened a "Hackathon on Health Data Federated Querying" on April 4th, 2025. The event gathered around 50 information technology (IT) specialists from 10 EU member states. Participants possessed a diverse range of expertise in key areas such as the Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable (FAIR) principles, semantic web technologies, software development, database operations, and healthcare data standards. The hackathon’s format was inspired by "Bring Your Own Data" workshops [

3], which have been successfully used to foster awareness and research on the FAIR principles.

The hackathon objectives were defined based on the results of a broad survey that was also conducted as a task of WP8 [

4]. This survey evaluated the technical, legal, and organizational barriers [

5] by collecting information from clinicians, hospital IT experts, and national authorities. The survey results revealed a significant difference in how European countries manage data: while a few countries use fully digital systems with national registries and standardized codes, the majority still relies on paper-based documentation (or a combination of digital and paper) [

32]. Therefore, sharing data within ERNs is mostly a manual and burdensome task that faces challenges related to lack of (i) an infrastructure architecture for secure data exchange; and (ii) the use of standardised diagnosis codes and (iii) artefacts to make data sources more FAIR within a knowledge exchange infrastructure. Hence, the hackathon's primary goal was to collaboratively identify and experiment with potential solutions to automate the secure exchange of harmonised FAIR data.

This paper provides a comprehensive review of the hackathon, detailing the challenges addressed, the solutions proposed by the working groups, and its impact on the strategic next steps for the JARDIN initiative.

2. The Hackathon Format and Overview

The hackathon was designed to address three selected challenges among the many identified in WP8’s broad survey1 on technical barriers of data exchange. These were chosen in consultation with a panel of JARDIN advisors, prioritising those deemed most urgent and feasible to address within the scope and duration of a hackathon.

The first challenge focused on brainstorming an IT architecture to enable a secure and controlled exchange of information among HCPs, national registries, and ERNs. The second tackled the need to harmonise data from different HCPs. The third challenge aimed at finding means to ensure that data from HCPs are made available for access and reuse with clear and well-defined conditions, according to the FAIR principles. These challenges are described in more detail in

Section 3.

To ground the hackathon's activities in a tangible scenario, a common use case was established: a clinician responsible for clinical trials seeking to identify eligible patients across different institutions. In this scenario, a list of patients containing their age, diagnosis, and genotype is required from various hospitals to facilitate recruitment for the trial. This use case highlights the critical need for simplified, secure data flow between hospitals, national systems, and ERN registries.

The 4-hour hackathon agenda was divided into three main parts with the following structure and content:

Introduction (20 minutes): This session provided participants with all necessary context, including an overview of the JARDIN project and WP8, challenges in health data exchange, a review of the selected hackathon challenges, and organizational instructions.

-

Working Sessions & Discussion (3 hours 15 minutes): This central block was divided as follows:

- ○

Working Session 1 (1 hour 45 minutes): Participants chose a challenge and joined a corresponding breakout group.

- ○

Group Discussion (20 minutes): All participants reconvened to discuss progress. This also served as an opportunity for individuals to switch working groups if they desired.

- ○

Working Session 2 (1 hour 10 minutes): Participants continued their collaborative work.

Wrap-up (15 minutes): The event concluded with a final session to summarize key outcomes and outline potential future directions.

Participants were given resources to help them document their proposed solution and recommend an implementation strategy. These resources included a virtual whiteboard for brainstorming, a shared storage space for transferring files, and a documentation template. The template first provided participants with a detailed description of their challenges and the use case. It then had specific sections for the teams to complete, where they could describe their proposed solution, its proof of concept or demonstration, the implementation strategy, and any potential scalability risks. The templates used in each challenge are available as supplementary material [

6].

2.1. Participants Overview

The hackathon drew 47 participants from the 57 individuals who registered (82.5%), representing a diverse group from ten different countries: Belgium, Cyprus, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and The Netherlands. Invitations were distributed through JARDIN’s mailing list, social media channels, and internal newsletter, and participants were encouraged to share the call with their colleagues. A report detailing the hackathon's participation and outcomes is publicly available at [

6].

To better understand the collective technical proficiency of the group, participants were asked to self-assess their expertise across several key domains. Forty of the 47 participants (85.1%) responded to the assessment. This assessment utilized a five-point rating scale, where 1 represented "none or limited knowledge" and 5 represented "expert". The areas evaluated included FAIR principles, semantic web tools, ontologies, and software development.

As shown in

Table 1, self-assessed expertise varied considerably across topics, which may reflect the diverse backgrounds of Hackathon participants and their different levels of domain-specific knowledge. Participants who completed the self-assessment reported the highest level of expertise in FAIR principles, whereas HCP software and Ontologies were associated with the lowest self-assessed knowledge. Nevertheless, except for the HCP software, at least 20% of respondents reported “high” (4) or “expert” (5) level in specific domains. Additionally, apart from this topic and the Knowledge/Data topic, between 10% and 20% reported an “expert” level (5). These results indicate a considerable level of expertise across most topics and, from a group perspective, an overall strong expertise. Furthermore, each working group included at least one participant with a high to very high level of expertise (data not shown), which supported the execution of some technically complex tasks within the challenges.

3. The Hackathon’s Focus Challenges

The data collected when patients visit a HCP is usually stored locally (digitally). With the patient's consent, (anonymised) data can be shared with larger networks, such as national registries or ERNs. The sharing process involves exporting the data from the local HCP system to the network, where it is imported by other providers and merged with additional information. These larger knowledge bases enable reuse by various stakeholders—including researchers, patient organizations, and government bodies—under specific data access and use conditions.

This data exchange process firstly introduces two fundamental challenges that were addressed at the hackathon. First, because medical data are sensitive, it must be shared within a secure environment that protects patient privacy and ensures it is used only under approved conditions (Challenge #1: Querying Service). Second, for the patient data to be meaningfully combined, it must be harmonised into a consistent format and structure that accounts for the different sources (Challenge #2: HCP Data Harmonization).

However, the data flow is not just one-way. HCPs also receive information and feedback regarding diagnosis and/or treatment from other providers and ERNs. Therefore, the different systems must be able to find and understand each other automatically. This creates a third challenge: each data source must describe itself, its data, and its access rules in a clear, machine-actionable format. This problem was addressed as Challenge #3: Metadata Description. These three challenges are described in the next subsections.

3.1. Challenge #1: Querying Service

The querying service challenge focused on designing a secure service architecture to allow data querying from multiple sources (i.e., HCPs, national registries, and ERNs) without exposing sensitive information. The overall goal was to develop a service that could receive a request, execute a query across several harmonized datasets, and return aggregated, non-identifiable results.

Therefore, the main tasks for the participants were (i) to define a clear workflow and architecture for the querying process; (ii) to create a proof-of-concept or a demonstration for the specific patient cohort use case; and (iii) to discuss methods to allow data to be used under controlled conditions.

To support this work, participants were provided with sample data (available as supplementary material). These were AI-generated CSV files2 that had been annotated with an ontology to simulate the fully harmonized data needed for this challenge. Consequently, the group was informed that they should focus on the data exchange itself, as the harmonisation and metadata exposure aspects were to be addressed by other working groups.

3.2. Challenge #2: HCP Data Harmonisation

The HCP data harmonisation challenge focused on investigating methods to generate harmonised data from exports of HCP systems. For it to be effectively manageable for the hackathon, we assumed that all systems are able to export their data into a simple CSV file. This allowed participants to focus on the task of harmonising the data itself, rather than on the complexities of extracting it in different ways from different systems. While the ideal solution would use secure Application Programming Interfaces (APIs), it is argued that the methods developed for CSV files could be adapted for such systems.

With this simplified setup, the goal was to find ways to convert different CSV files into a single, harmonized format that uses semantic web standards. The main tasks for the participants were: (i) to design or reuse a semantic data model for the common use case; and (ii) to develop scripts to convert various source CSVs into the standard target template. Also, a critical requirement of this challenge was mapping different diagnosis codes (e.g. ICD-10 or free text) to Orphanet codes [

7], a process identified as a best practice for coding rare disease diagnoses by the European Steering Group on Health Promotion, Disease Prevention and Management of Non-Communicable Diseases [

8].

To support this work, participants were provided with sample CSV files containing AI-generated data (available in the supplementary material). These files were designed to simulate real-world conditions and intentionally included inconsistent formatting and irrelevant data.

3.3. Challenge #3: Metadata Description

The metadata description challenge focused on a fundamental aspect of the FAIR principles: making data services easy to find and use within ERNs. The main goal was to improve how these services are described using the FAIR Data Point (FDP) [

9], which is a software specification for publishing standardized metadata. For the purpose of this challenge, a "data service" was defined as the technical means by which one data source (such as an ERN registry) allows another party (such as an HCP) to access its data.

To make the task manageable, two key assumptions were made. The first was that a secure network (the output of Challenge #1) was already in place. Second, to allow participants to focus on the metadata itself rather than on software development, the FDP was chosen as the standard tool for publishing the service descriptions. Given this setup, the participants' specific tasks were to (i) review the existing FDP metadata model; (ii) identify any gaps in its ability to describe data services; and (iii) suggest improvements to make these descriptions more useful for both people and automated systems.

4. Proposed Solutions and Technical Frameworks

The hackathon's working groups proposed a series of complementary solutions, demonstrating a strong preference for adapting and integrating existing, tested technologies rather than building entirely new systems from scratch. Overall, the solutions are closely interrelated: the high-level architecture proposed in Challenge #1 serves as the overarching framework, while the solutions to Challenge #2 and Challenge #3 provide detailed specifications for key components within that framework, as described below.

4.1. Solution to Challenge #1: A Hybrid Federated Querying Architecture

The group working on challenge #1 proposed an architecture diagram to detail and organise the components necessary on an infrastructure enabling the exchange of harmonised data (

Figure 1). The diagram, simplified for the sake of readability, was originally designed using the Archimate modelling language (available in the supplementary material).

The proposed architecture consists of four main components that work together to process a query. The query trigger is the user's entry point to the network. A researcher uses the trigger to submit their query. Along with the query itself, they must provide the intended conditions for data reuse and information about their user profile.

The

query processor acts as the central hub of the network. It receives the request from the trigger and first checks the requester's profile and access conditions to authorise the query against the network's policies. If authorized, the processor then finds relevant data sources by searching the metadata available in their FDPs (further specified in challenge #3). Once matching sources are found, the processor forwards the query to their FAIR Data Stations. Note that the query processor checks the allowed use conditions by comparing the information provided in the query request with that exposed by the FDPs. The group suggested making this information machine-actionable using the Open Digital Rights Language (ODRL) standard [

10]. The ODRL model is explained further in subsection 4.1.1.

The FAIR Data Station resides at the data-holding institution (e.g. an HCP). It receives the query from the query processor and performs a final check, comparing the query's reuse conditions against the local data's specific permissions. If the request is compliant, the Data Station executes the query on the HCP harmonized dataset and returns its results to the query processor.

The HCP harmonized dataset, which is the focus of challenge #2, resides locally and is queried by the FAIR Data Station. It must also contain the necessary information regarding patient informed consent. After a query is run, the FAIR Data Station sends the aggregated results back to the central Query Processor. In the end of the process, the Query Processor gathers the results from all responding Data Stations, aggregates them into a single response, and returns it to the user via the Query Trigger.

This entire process, outlined by the proposed architecture, is an example of federated querying. This approach significantly enhances data protection because the sensitive raw data never leaves the secure environment of the local institution. Instead, only the query travels to the data, and only aggregated, non-sensitive results are returned to the Query Processor. For the implementation of the components of the architecture, the group suggested reusing existing resources from other initiatives, as further detailed in subsection 4.1.2.

4.1.1. The ODRL Model

ODRL is a World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) standard for creating machine-readable policies that express rights, permissions, and obligations over digital assets like data. These policies are used to automatically determine if a data access request should be granted by matching the request's parameters against the data's usage rules. An ODRL policy is set by an Assigner (the data owner) for a specific Target (the dataset). The policy contains one or more Rules, such as a Permission, which defines an Action (e.g. “read” or “update”) that is allowed for a particular Assignee (a type of user or group). Critically, this permission can be bound by Constraints, such as requiring a specific research purpose or geographic location. When a request is received, a system can automatically compare the requester's profile and intent against the Assignee and Constraint definitions in the policy to authorize or deny the action.

To demonstrate its practical application, the group working on challenge #1 also drafted an initial ODRL policy model for the patient cohort use case as a suggestion for how access conditions could be managed within their proposed architecture. This is presented in

Figure 2.

Figure 2 provides a specific example of an ODRL policy model designed to govern access to a filtered patient dataset for research. The model grants a

Permission for the

Action "Run Query" to an

Assignee defined as a "Researcher." This permission, however, is only valid if two constraints on the researcher are met: first, that their "Credentials" are valid, and second, that they are confirmed to be part of the "Institute Network," which acts as the

Assigner of the rights.

Furthermore, the policy defines constraints on the data itself. The Target of the query is specified as "Filtered Patient Data." The model shows that this data has already been created through a refinement process where only patients fulfilling the "Study Criteria" (e.g. having provided informed consent) are included. This ensures the query only runs on data from the appropriate patient cohort.

By formally defining these conditions for both the user and the data, the ODRL model provides an automated method for enforcing complex data access rules, ensuring that sensitive information is protected while enabling responsible reuse.

4.1.2. Leveraging Existing Initiatives

To ensure better convergence and accelerate development, the working group recommended reusing components from other initiatives. This approach also increases collaboration and helps solutions mature more quickly. Based on the participants' experience, two specific projects were highlighted as key sources for reusable solutions: the Heterogeneous Semantic Data Integration for the Gut-brain Interplay (HEREDITARY) project [

11] and the European Joint Programme on Rare Diseases (EJP RD) [

12].

The HEREDITARY project is a European initiative focused on integrating data to study the relationship between gut health and neurodegenerative diseases. Its federated analytics framework is designed around a virtual data lakehouse architecture [

13], which allows complex analyses to be run across distributed sources without centralising sensitive data. Preliminary results on genomic data show the HEREDITARY project’s Semantic Data Integration platform can facilitate federated querying, even across multiple, heterogeneous datasets. This capability is pivotal for cross-institutional studies, where accessing comprehensive, interoperable data while satisfying legal constraints is critical [

14].

The European Joint Programme on Rare Diseases (EJP RD) was a large-scale initiative created to build a comprehensive ecosystem for rare disease research, bringing together a wide range of stakeholders to accelerate diagnosis and therapy development. An important result of this program is the EJP RD Virtual Platform (VP) [

15], a federated infrastructure that allows researchers to discover and query rare disease resources (e.g. registries, biobanks) under certain conditions). The EJP RD concluded in 2024 and is now being followed up by the European Rare Disease Research Alliance (ERDERA) [

16].

Building on these established projects, the group made specific recommendations for the components of their proposed architecture.

Harmonized Dataset. To create a powerful and scalable data harmonization solution, the group recommended adopting the data virtualization architecture pioneered by the HEREDITARY project. This approach is powered by a strategic orchestration of multiple components that realizes the Ontology-Based Data Federation (OBDF) [

17] paradigm, whose implementation requires two main components: a data lake platform and an Ontology-Based Data Access (OBDA) [

18] query rewriter. The former enables data access to multiple relational sources, harmonizing different schemas with virtual views and providing a single viewpoint on top of it; the latter is capable of exploiting ontologies and RML (RDF Mapping language [

19]) mappings to rewrite and unfold graph-based queries in relational format. A possible implementation for OBDF leveraging open-source components uses Dremio [

20] as the data lake platform and Ontop [

21] as the OBDA component. This setup exposes a virtual knowledge graph, enabling complex and semantic-enriched queries across all connected sources. This recommendation also aligns with the suggestions made by the group for Challenge #2 (as described in the next subsection), in which the proposed semantic model can act as the central model for this virtual layer.

FAIR Data Station and FAIR Data Point. The group recommended connecting with existing development efforts that are already creating a formal specification and implementations for the FAIR Data Station concept [

22]. Additionally, the group proposed extending the existing FDP metadata model following the EJP RD metadata model [

23] to describe rare disease resources, which is consistent with the work from the challenge #3 group.

Query Processor. For this central component, the group suggested a hybrid approach using tested solutions from both HEREDITARY and EJP RD. The key recommendation was to use the GA4GH Beacon v2 protocol [

24] as the standardized interface for querying resources within the network. The GA4GH Beacon protocol is an international API specification standard for discovering genomic and clinical data in a privacy-protecting manner. In its latest version (Beacon v2), it allows a user to ask complex questions of a data source (e.g., "how many female patients over 40 with a specific diagnosis do you have?") and receive a granulated response depending on the access level of the user (boolean, count or record response) while maintaining the anonymity of the patients. In the proposed federated network, Beacon would serve as the uniform API, allowing the central Query Processor to communicate with all connected Data Stations using a single, shared language.

4.2. Solution to Challenge #2: Data Harmonization via CARE-SM

The working group for Challenge #2 proposed a solution centred on the Clinical and Registry Entries Semantic Model (CARE-SM) [

25]. This model was chosen as the standard for harmonising data because it uses the machine-readable Resource Description Framework (RDF) to represent patient information in a structured, graph-based format. The foundational structure of CARE-SM relies on the Semanticscience Integrated Ontology (SIO), which serves as its core schema and defines all concepts within the data model through its upper-class classes and properties. CARE-SM follows a design pattern in which individual roles are realised in processes, which in turn have outputs that follow controlled attribute types (e.g. range). This pattern facilitates data integration and querying.

Figure 3 shows a simplified excerpt of CARE-SM, including an example of how the clinical trial use case data is instantiated.

To demonstrate their approach, the group developed a proof-of-concept of a data transformation and harmonisation pipeline with three main steps. A complete example of this pipeline was provided in a Python notebook (available as supplementary material). An illustration of this pipeline is presented in

Figure 4:

Ingestion (focus on data format): Raw data from source CSV files is imported into a standard tabular structure using an automated tool. The group suggested DuckDB [

26] as an example of such a tool.

Semantic enrichment: The imported data is then mapped to a standard template following controlled vocabularies. This step uses a combination of approaches, including SQL functions [

27], Python User-Defined Functions (UDFs) [

28] for more complex logic, and even Large Language Models (LLMs) to identify patterns in unstructured text. Examples of these transformation approaches are available in the python notebook (sup. material [

6]).

Syntactic harmonisation: Finally, the standardized tabular data is converted into the semantically rich RDF format following CARE-SM. This is achieved using tools like Ontop or RDF Mapping Language (RML). For instance, with Ontop, the OWL implementation of CARE-SM could be used, and mappings retrieved via SQL queries on the tabular data produced in the previous step. The Ontop endpoint would then be provided in the semantic layer of the proposed architecture from challenge #1.

The group emphasized that while automation is helpful, human expertise is essential for creating the initial mappings from a local system to the common template. Furthermore, the group suggested a two-phase, iterative implementation strategy for the solution proposed. In phase 1 (Pilot), institutions should begin by adapting their systems to harmonize a small, core set of data elements required to answer specific “simple” use cases (e.g., the elements listed in the clinical trial use case). This allows them to build expertise while navigating the challenging initial setup. Subsequently, in phase 2 (Expansion), initiated after the initial hurdles are overcome, the systems can be expanded to export more complex and comprehensive patient information.

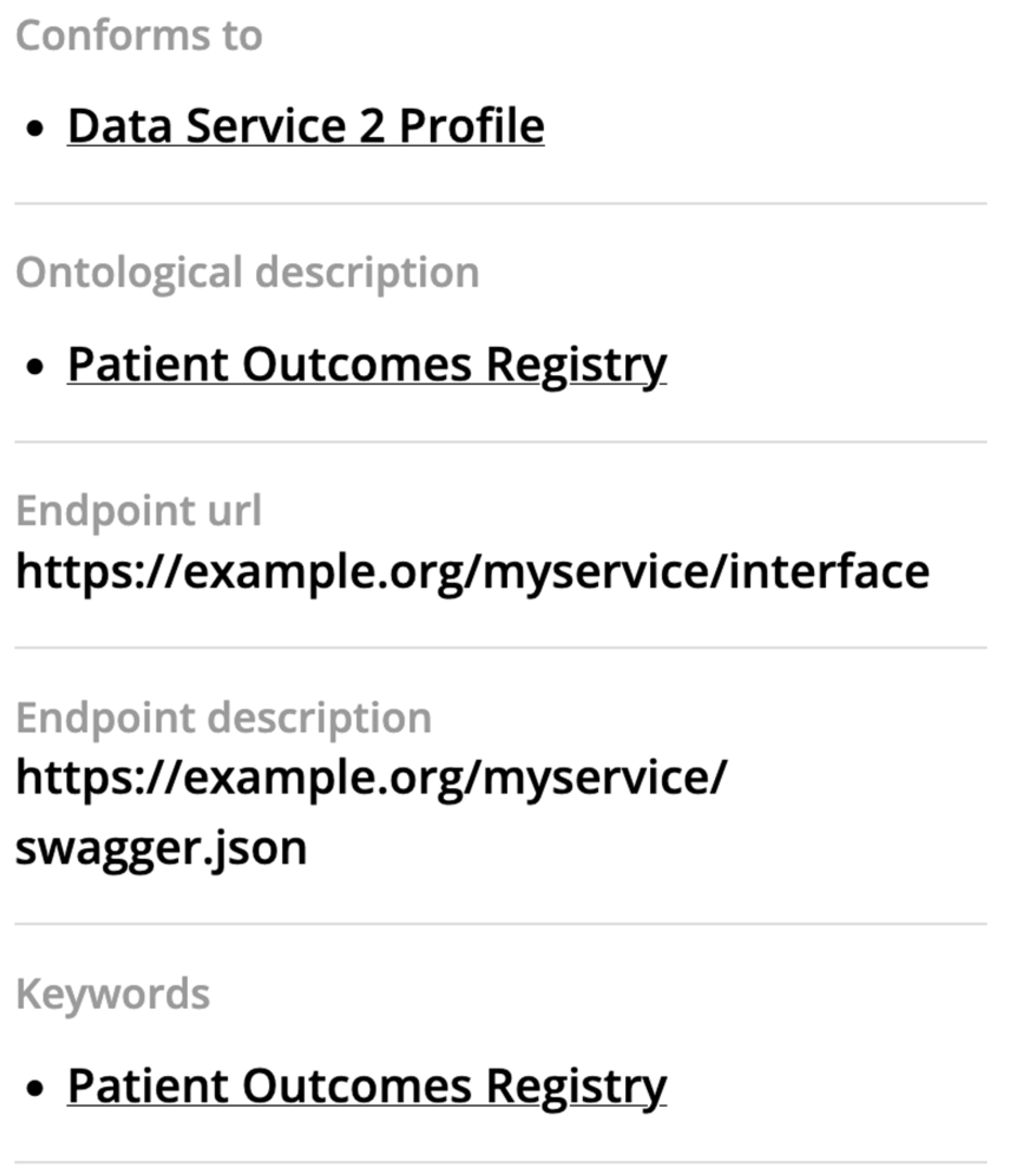

4.3. Solution to Challenge #3: Extending the FAIR Data Point (FDP) Metadata Model

The working group for challenge #3 focused on describing a data service using an FDP. For their work, the group utilised FDP version 1.16 and developed a proof-of-concept demonstration, in which they successfully configured a test instance of FDP, demonstrating how a data service for the rare diseases domain can be described in practice.

The group's recommendations are based on the FDP's internal structure, which uses the W3C standard Data Catalog Vocabulary (DCAT) [

29]. The FDP is built on DCAT because it is the international standard for describing data catalogs, which promotes widespread interoperability. Maintaining compatibility with DCAT is therefore essential to ensure that the data services described in this project can be discovered and used by other major data initiatives. The EJP RD metadata model, suggested by group #2, is also aligned with DCAT.

DCAT organises metadata using a logical hierarchy. At the highest level is the Catalog, which acts as a container for a collection of datasets. Each Catalog contains one or more Datasets, which represent a conceptual collection of data (e.g. "A registry of rare disease patients"). A single Dataset can be made available in different forms, each of which is called a Distribution (e.g., a CSV file and an API could both be distributions of the rare disease patients' data). Finally, a Data Service describes the specific operation that provides access to the data, such as a query endpoint or a direct download link.

First, the group provided recommendations on which ontological terms and keywords to use at each level of the DCAT hierarchy. To illustrate, examples of suggested keywords and ontology terms are described in

Table 2. For instance, at the Catalog and Dataset level, they suggested using terms from the National Cancer Institute Thesaurus (NCIT) [

30] and Orphanet codes to describe key concepts such as 'Patient outcomes registry', 'Diagnosis', 'Genotype', and specific diseases (e.g., Duchenne muscular dystrophy).

Second, the group provided two key technical recommendations on how to describe a data service within the DCAT vocabulary:

Properly link the data service to the dataset: the group recommended using the dcat:servesDataset property to explicitly connect the data service record to the parent dataset record. This is additional to the existing association of Data Service with Distribution, because it ensures the service is linked to the overall descriptive metadata (like dcat:theme and keywords) that are defined at the Dataset level.

Describe service parameters in the endpoint description: To explain what parameters a data service accepts (e.g., for a query), the group recommended using the

dcat:endpointDescription property. This property is the designated place to provide documentation on how other systems can interact with the service. An endpoint description is shown in

Figure 5.

Finally, the group emphasized a critical requirement for this approach: the creation of detailed documentation and guidelines. They emphasised that these guides must not only explain the technical steps for installing an FDP, but more importantly, how to populate it correctly using high-quality, well-chosen ontological terms.

4.4. Risk Assessment

An additional, crucial recommendation from the hackathon conclusion session was that the implementation of any solution must be preceded by a thorough risk assessment. For instance, the working group for challenge #2 identified several risks and their potential mitigations, which are broadly applicable to all the solutions presented in this paper:

Data privacy and compliance: A primary risk is non-compliance with data protection regulations, such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which may have significant legal and ethical implications. This risk can be addressed by enforcing strict local data processing rules and using secure aggregation protocols to ensure full compliance.

System performance: A service that communicates with multiple networks may become inefficient for practical use, hindering its adoption by clinicians and researchers. To mitigate this, performance can be improved by optimizing query execution, implementing data caching, and using parallel processing where feasible.

User-friendliness: A system’s usability is crucial for adoption. This can be improved by focusing on clear communication and accessible design. This involves providing technical documentation and usage instructions in clear, accessible language and offering this support in multiple languages to cater to a diverse user base. Furthermore, it is important to follow established user interface (UI) design principles wherever applicable to ensure the service is intuitive and predictable for all users.

Technical integration: Connecting a new service to the diverse and often outdated IT systems at different institutions poses a major technical challenge. This requires designing the system in a modular and adaptable way, in close collaboration with local IT teams to create customized integration solutions.

Cybersecurity vulnerabilities: Any service providing access to distributed health data can be a target for cyberattacks. Protecting against this risk involves implementing robust security measures, including end-to-end encryption, regular security audits, and strict access control protocols. It is of note that one of the tools developed for the creation and publication of FAIR data and metadata (including FDPs) in the EJP RD project, FAIR-in-a-box [

31], is under an ongoing assessment and peer-review of the cybersecurity of its components. This tool uses components from different publishers, originally posing a challenge when it comes to ensuring its complete security. Now, a pipeline has been created that automatically implements the latest security patches for all components, re-tests each patched container, and publishes the results in GitHub to ensure full transparency. An independent working group has been established to deeply monitor the security reports for at least one of the components, and take action if deemed necessary and plausible.

5. Discussion and Key Messages

The JARDIN Hackathon on Health Data Federated Querying brought together a multidisciplinary community of clinicians, FAIR data stewards, and semantic web and software engineering experts to co-design interoperable solutions grounded in real-world use cases. This effort underscored that building a functional data exchange ecosystem is not solely a technical problem, but also a socio-technical one that requires continuous collaboration. It also demonstrated that hackathon-style collaborations were demonstrated to be an effective way to align technical and semantic practices across institutions and to converge on implementable frameworks, such as the one outlined in

Figure 1. Overall, these initiatives position JARDIN efforts as methodological models for identifying future community-driven solutions to interoperability challenges in health data exchange.

The outcomes of the hackathon converge on key messages that are critical for the future of automated and secure exchange of health data in Europe. Beyond producing actionable solutions, the event strengthened the collective capacity of the European rare disease community to operationalise the FAIR principles in practice. A prominent theme was the consensus to leverage existing, validated frameworks instead of developing novel ones. The proposals to adapt existing solutions, such as the EJP RD Virtual Platform and metadata model, the CARE-SM semantic model, and the FDP architecture reflect a pragmatic approach that can accelerate development and ensure greater stability and interoperability of health data.

Furthermore, the hackathon validated the value of prioritizing incremental, practical steps. Starting with challenges of lower complexity such as harmonizing CSV files provides tangible goals that deliver immediate value while laying the groundwork for more complex solutions such as live, API-based data exchange. This iterative approach is essential for managing complexity and encouraging adoption among diverse institutions with varying technical capabilities.

It is also worth noting that for the data harmonization process, a comprehensive and standardised set of data elements for rare diseases must first be defined. The selection of these core data elements and the recommendation of appropriate standards and codes for each one is the focus of a dedicated task within the scope of WP8. The work from this task will provide the essential foundation for implementing the harmonization pipeline proposed during the hackathon.

In addition, it is observed that the FAIR principles and semantic web artefacts provide a clear roadmap for the development of all proposed solutions. For instance, using FDPs makes services Findable, employing semantic models ensures data is Interoperable, and defining clear access conditions makes data Accessible. These principles offer the foundational guidelines for building a scalable and responsible data ecosystem, while semantic web technologies such as RDF provide proven, efficient methods for data harmonization and exchange.

Moreover, although developed by separate groups, the solutions proposed for the three challenges are complementary and can operate collectively as an integrated system. The data harmonization process from Challenge #2 provides the standardised data that is then shared through the secure network architecture from Challenge #1. In turn, the metadata standards from Challenge #3 are used to describe the services within this network, making them discoverable and usable. Additionally, this interconnected design also allows for a coordinated implementation strategy. Individual institutions can incrementally adopt the data harmonization (Challenge #2) and service description (Challenge #3) methods to build local expertise. Simultaneously, a dedicated group can work in parallel to establish the core network infrastructure (Challenge #1) in close collaboration with these institutions.

To further support and accelerate deployment, additional initiatives should be undertaken. For instance, targeted training programs can be provided to institutions to help their staff prepare for implementing the new data transformation and access protocols. Indeed, as described in [

3], similar initiatives leveraged on Bring Your Own Data Workshops to increase awareness of, expertise in, and research on the FAIR principles and FAIR-enabling software and standards.

While the solutions proposed represent a significant strategic step forward, they have not yet been sufficiently tested in real-world settings. A crucial next step is to test implementations of these conceptual architectures with dedicated focus groups to assess their practicality and gather implementation feedback. That said, it is important to state that these are not merely theoretical proposals; they were designed by experts in the field, grounded in previous experiences from projects where these technologies and approaches have already been successfully assessed and validated.

Finally, it is important to note that the three hackathon challenges were simplified versions of highly complex, real-world problems. They were made more manageable to ensure they were achievable within the limited time of the event. For example, the task of converting unstructured data (e.g., free-text clinical notes) into a structured format—a crucial step for the harmonization process in Challenge #2—was excluded from the scope of the hackathon. Similarly, the final step of analyzing the combined data to extract new scientific insights was considered a challenge to be addressed in future initiatives. Indeed, many of these related issues are already being addressed by other initiatives within JARDIN or through collaborations with other projects, such as ERDERA.

6. Conclusion and Future Steps

The exchange of health data across European institutions remains hindered by persistent barriers such as heterogeneous data formats, fragmented infrastructures, and limited use of common standards. While several initiatives have addressed parts of this challenge, there remains a gap in integrating these approaches into a coherent and operational architecture. The JARDIN Hackathon on Health Data Federated focused on addressing this gap by convening a multidisciplinary group of experts to experiment with concrete, complementary solutions that build upon these established efforts.

From this work, a clear strategic direction emerged: to build on existing successful solutions, proceed with practical, incremental steps, and let the FAIR principles guide all stages of development. By aligning with ongoing European initiatives and FAIR data standards, the proposed architecture provides a scalable and reproducible blueprint for automating the secure exchange of harmonised data from the point of care to research networks.

Based on the hackathon's outcomes, JARDIN WP8’s next steps will involve several key activities. First, the proposed solutions described in this work will be further refined using additional feedback from the expert community. Next, these refined solutions will be tested with pilot groups to understand real-world implementation challenges. Finally, the project will continue to collaborate with the wider community to expand the inventory of potential solutions for these and other related challenges.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Emiliano Reynares (IQVIA) and Dennis van Gerwen (LUMC) for their invaluable insights, and to all other hackathon participants for their collaborative efforts. This work was supported by the JARDIN - Joint Action on integration of ERNs into national healthcare systems project (101129863), which is co-funded by the European Union under the grant number EU4H-2022-JA2-IBA-05.

Notes

| 1 |

Note that the WP8 survey identified a higher number of challenges relating to technical, organisational and legal barriers. The hackathon focused on a selection of technical challenges, chosen through discussions with experts in the field. Other challenges that were not addressed during the hackathon remain relevant and are planned to be addressed in future work. Readers should refer to [ 32] for more details on the survey and its results. |

| 2 |

CSV files were chosen for their simplicity and ease of use, which was a practical consideration given the hackathon's limited timeframe. Furthermore, it is expected that any HCP system is minimally capable of exporting data in at least a CSV format. |

References

- European Commission, "European Reference Networks," Public Health. Accessed: Nov. 18, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://health.ec.europa.eu/rare-diseases-and-european-reference-networks/european-reference-networks_en.

- “JARDIN Joint Action European Reference Networks,” JARDIN Joint Action. Accessed: Nov. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://jardin-ern.eu/.

- C. H. Bernabé et al., “Building Expertise on FAIR Through Evolving Bring Your Own Data (BYOD) Workshops: Describing the Data,Software, and Management-focused Approaches and Their Evolution,” Data Intelligence, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 429–456, Sep. 2024. [CrossRef]

- “Data management,” JARDIN Joint Action. Accessed: Nov. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://jardin-ern.eu/work-package/data-management/.

- L. D. Hughes et al., “Addressing barriers in FAIR data practices for biomedical data,” Sci Data, vol. 10, no. 1, p. 98, Feb. 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Bernabé, ‘The JARDIN hackathon to seek solutions to overcome technical barriers in health data exchange - Paper's supplementary material’. Zenodo, Nov. 13, 2025. [CrossRef]

- “ORPHAcodes.” Accessed: Nov. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.orphacode.org/.

- “Rare diseases,” Public Health. Accessed: Nov. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://health.ec.europa.eu/rare-diseases-and-european-reference-networks/rare-diseases_en.

- L. da Silva Santos, K. Burger, R. Kaliyaperumal, and M. Wilkinson, “FAIR Data Point: A FAIR-Oriented Approach for Metadata Publication,” Data Intelligence, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 163–183, Feb. 2025. [CrossRef]

- “The Open Digital Rights Language: XML for Digital Rights Management,” Information Security Technical Report, vol. 9, no. 3, pp. 47–55, Jul. 2004.

- “HEREDITARY project.” Accessed: Nov. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://hereditary-project.eu/.

- “Home,” EJP RD - European Joint Programme on Rare Diseases. Accessed: Nov. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.ejprarediseases.org/.

- Oreščanin, D., & Hlupić, T. (2021, September). Data lakehouse-a novel step in analytics architecture. In 2021 44th international convention on information, communication and electronic technology (MIPRO) (pp. 1242-1246). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- L. Menotti, G. Silvello, M. Cazzaro, I. G. Gut, and M. Rueda, “HERO-Genomics: An Ontology for Integration and Access of Multicenter Genomic Data”. [CrossRef]

- “EJP-RD Resource Discovery Portal.” Accessed: Nov. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://vp.erdera.org/.

- “European Rare Diseases Research Alliance” ERDERA. Accessed: Nov. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://erdera.org/.

- Z. Gu, D. Calvanese, M. D. Panfilo, D. Lanti, A. Mosca, and G. Xiao, “OBDF: OBDA + Data Federation – Extended Abstract,” in 2024 IEEE 40th International Conference on Data Engineering Workshops (ICDEW), IEEE, May 2024, pp. 381–383. [CrossRef]

- D. Calvanese, G. De Giacomo, D. Lembo, M. Lenzerini, A. Poggi, and R. Rosati, "Ontology-based database access," in SEBD, June 2007, pp. 324–331.

- Dimou, M. Vander Sande, P. Colpaert, R. Verborgh, E. Mannens, and R. Van de Walle, "RML: A generic language for integrated RDF mappings of heterogeneous data," in LDOW, vol. 1184, 2014.

- “Intelligent Lakehouse Platform for Unified Data Access,” Dremio. Accessed: Nov. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.dremio.com/.

- T. Bagosi et al., “The ontop framework for ontology based data access,” in Communications in Computer and Information Science, in Communications in computer and information science. , Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2014, pp. 67–77.

- “FAIR Data Train specifications.” Accessed: Nov. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://specs.fairdatatrain.org/.

- “GitHub - ejp-rd-vp/resource-metadata-schema: Metadata model and schemas for the EJP virtual platform,” GitHub. Accessed: Nov. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/ejp-rd-vp/resource-metadata-schema.

- J. Rambla et al., “Beacon v2 and Beacon networks: A ‘lingua franca’ for federated data discovery in biomedical genomics, and beyond,” Hum Mutat, vol. 43, no. 6, pp. 791–799, Jun. 2022. [CrossRef]

- P. Alarcón-Moreno and M. D. Wilkinson, "Take CARE of your patient data: Clinical and registry entries (CARE) semantic model," in Proc. 15th Int. Conf. Semantic Web Appl. Tools Health Care Life Sci. (SWAT4HCLS), Leiden, Netherlands, 2024.

- “An in-process SQL OLAP database management system,” DuckDB. Accessed: Nov. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://duckdb.org/.

- L. Rockoff, The Language of SQL. Addison-Wesley Professional, 2016.

- “Function (computer programming).” Accessed: Nov. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Function_(computer_programming).

- “Data Catalog Vocabulary (DCAT) - Version 3.” Accessed: Nov. 12, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://www.w3.org/TR/vocab-dcat-3/.

- S. de Coronado, L. Remennik, and P. L. Elkin, “National Cancer Institute Thesaurus (NCIt),” Terminology, Ontology and their Implementations, pp. 395–441, 2023. [CrossRef]

- “GitHub - ejp-rd-vp/FiaB: FAIR IN A BOX,” GitHub. Accessed: Nov. 18, 2025. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/ejp-rd-vp/FiaB.

- de Oliveira Coelho Henriques, V. Sand, D. V. Albring, C. Bernabé, A. Vohora, S. Maiella, I. C. M. Pelsma, V. Šimka, P. Doležalová, A.-S. Lapointe, M. Roos, A. Rath, F. Schaefer, P. A. C. 't Hoen, and B. dos Santos Vieira, "Rare disease data management across Europe: Insights from the JARDIN survey on data sharing and interoperability," manuscript submitted to the Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases. Preprint available online.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).