1. Introduction

Numerous physiological processes in bacteria are regulated by small regulatory RNAs (sRNAs) to remodel their gene expression in response to changing environmental conditions [

1]. sRNAs help bacteria to adaptively react to the changing environmental conditions and regulate key stages of pathogenesis [

2]. Mycobacteria are known to express small RNAs that regulate protein expression by controlling mRNA stability, processing, and access to ribosome binding sites. These molecules have been shown to be closely linked to bacterial survival under stressful conditions, including the host immune response [

3,

4]. One of these RNAs, MTS1338 sRNA (DrrS sRNA or ncRv11733 sRNA), is highly expressed during the stationary phase of growth [

5] and the dormancy state [

6]. In vitro experiments demonstrated that its transcription is controlled by the transcriptional regulator DosR and is activated under hypoxic and NO-induced stresses [

7], suggesting that MTS1338 may play a role during the stable phase of infection, when host responses confront mycobacterial multiplication more or less successfully. MTS0997 sRNA (Mcr11 or ncRv1264Ac) upregulates several genes required for Mycobacteria tuberculosis fatty acid production [

30]. MTS0997 is abundantly expressed by M. tuberculosis in the lungs of chronically infected mice [

8] as well as in hypoxic and non-replicating M. tuberculosis [

4].

In the majority of bacteria species, trans-encoded sRNAs require RNA chaperones, either Hfq or ProQ, to ensure appropriate sRNA/mRNA base pairing [

9,

10]. However, experiments to identify the orthologues of the most common RNA chaperones Hfq, ProQ, or CsrA in M. tuberculosis have failed, which suggested that mycobacteria must exploit alternative proteins or mechanisms for efficient sRNA/mRNA interactions [

11]. Possible alternatives are either mycobacterial sRNAs can interact with their cognate mRNAs independently without the assistance of RNA chaperons, or they have an RNA chaperone that has not been discovered yet [

12]. One potential candidate for the role of RNA chaperone may belong to the cold shock protein family Csp. Cold shock proteins are multifunctional DNA/RNA binding proteins that are found in 72% of sequenced bacterial genomes [

13]. Functionally, bacterial proteins with the Csp domain are mainly transcription and translation factors, and it is also believed that they are involved in the remodeling of RNA structure, that is, they have RNA chaperone activity [

14,

15,

16]. Homologues of Csp are widespread in prokaryotes, acting in response to many different environmental stresses [

14,

17]. It has been shown that during cold shock, some Csp proteins exhibit their chaperone activity and melt secondary RNA structures, restoring processes such as transcription and translation [

18]. The number of Csp proteins varies among bacteria, for example, in E. coli nine Csp proteins have been identified, named CspA to CspI, and only some of the homologues have RNA chaperone activity [

19]. Two cold shock proteins have been identified in M. tuberculosis – CspA and CspB. Both of them contain a β-barrel cold shock domain (Csd) consisting of a three-stranded (β1-β2-β3) N-terminal and a two-stranded (β4-β5) C-terminal sheet. Recently we characterized CspA from M. tuberculosis (MtbCspA) and showed that it has a lower affinity for single-stranded RNA compared to single-stranded DNA despite of active involvement of the β3-β4 and β4-β5 loops in interactions with the oligonucleotides [

20].

CspB from M. tuberculosis (MtbCspB) has a long C-terminal region conserved among mycobacterial proteins and absent from other bacterial Csp proteins. In this study, we report the previously unexplored structure of the MtbCspB protein and its RNA-binding properties, targeting two small RNAs, MTS0997 and MTS1338, which are present only in the genomes of highly pathogenic mycobacteria.

2. Results

2.1. MtbCspB Forms Dimers

Based on the AlphaFold prediction, we suggested that MtbCspB could form dimers connecting the C-terminal α-helix hairpins. Under denaturing conditions, MtbCspB had a molecular weight consisting with a monomer – 15.9 kDa. However, gel filtration analysis of the protein revealed that MtbCspB preferentially forms dimers, as its peak is located between the peaks of proteins with molecular masses of 25 and 46 kDa (

Figure 1).

2.2. The MtbCspB Crystal Structure

The structure of MtbCspB was determined by molecular replacement and the protein monomer predicted by AlphaFold (AF-I6WZM9-F1, deposited at UNIPROT I6WZM9) was used (Fig. 2a). The initial model consisted of an N-terminal Csp domain, a C-terminal double α-helix hairpin and a long unstructured connection of these two parts of the protein. It was found one protein monomer in the asymmetric unit of the P3121 cell, divided into the N-terminal Csp domain (residues 2-71) and C-terminal double α-helixes hairpin (residues 84-135). The α1-helix (residues 88-110) bended in the region of residues 102-104. No electron density was found for residues 72-83. Analysis of the molecular crystal packing revealed that MtbCspB formed a dimer in the crystal due to tight contacts of the C-terminal parts and organized into a stable bundle of four α-helixes. According to PISA analysis, the buried surface within the bundle was 2440 sq. Å and ΔGint was -20.6 kcal/mol. This α-helical bundle was stabilized by a large number of hydrophobic contacts between the α-helixes. Moreover, four hydrogen bonds formed by the amino acid residues of the α-helixes shielded the ends of the bundle. Thus, the α-helical bundle was ordered in a stable spatial structure that facilitated the organization of the MtbCspB dimer. AlfaFold3 predicted the formation of the protein dimer in the same way, but in an elongated form that can be realized in solution (

Figure 2).

2.3. MtbCspB Is Able to Bind sRNAs MTS0997 and MTS1338

We determined the affinity of MtbCspB for two of the best-studied sRNAs from Mycobacterium tuberculosis - MTS0997 and MTS1338 - using surface plasmon resonance (SPR). Both sRNAs were transcribed and purified in vitro. The protein has been immobilized on the COOH-chip and the different concentrations of the sRNAs have been used as analyte. MtbCspB interacts with the sRNAs with high affinity and does not interact with oligoC RNA, which is used as a control (

Table 1) [

21,

22]. Cold shock proteins are known to bind to uridine-rich RNA so we have also tested protein’s ability to interact with oligoU RNA [

21,

22]. The affinity of the protein to the oligoU RNA is two orders of magnitude lower.

2.4. MtbCspB Modulates the Structure of MTS0997 and MTS1338 sRNAs Differently

To localize the protein binding sites on the sRNAs, we used the chemical probing of MtbCspB/MTS0997 and MtbCspB/MTS1338 complexes (

Figure 3). In case of MTS0997 sRNA, reactivity of nucleotides in the presence of MtbCspB increased, which means that the RNA structure has changed and the bases has become unpaired and solvent-exposed. Unlike MTS0997, MTS1338 nucleotides accessible to chemical modification in a free state mainly were less reactive to these probes in the presence of MtbCspB.

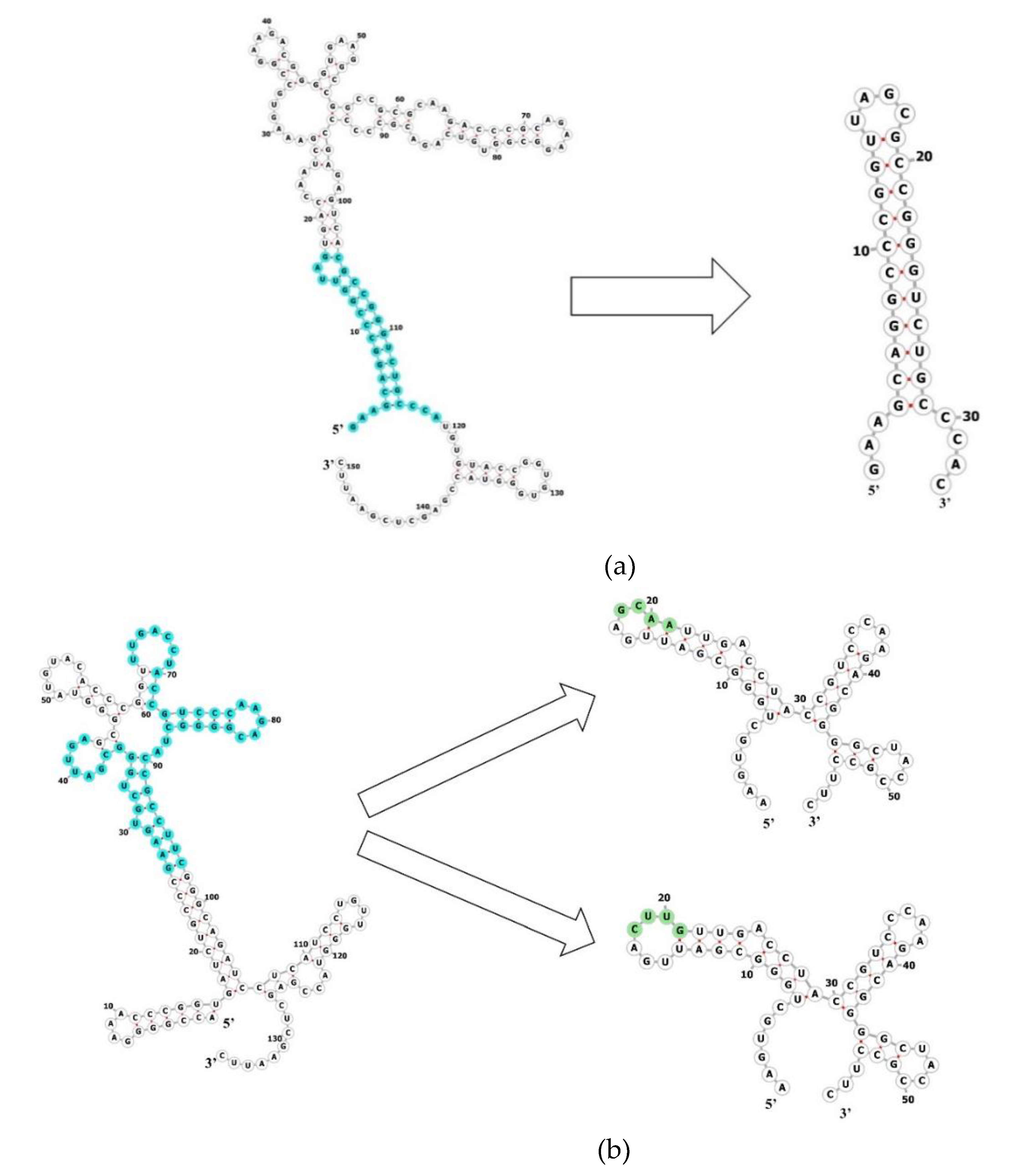

2.5. MtbCspB Can Bind to Short Variants of the RNAs

To further localization an MtbCspB binding site on RNA, we obtained several RNA fragments. Based on the analysis of secondary structure models and the results of RNA chemical probing we obtained one RNA fragment for MTS0997 (shortMTS0997) and two fragments for MTS1338 (shortMTS1338-GCAA and shortMTS1338-CUUG) (

Figure 4).

SPR measurements (

Table 2) showed that MtbCspB appeared to retain affinity for the RNA fragments, although the KD of MtbCspB complexes with MTS0997 and MTS1338 was two to three orders of magnitude lower (

Table 1). Importantly, when using a buffer with a higher ionic strength (0.25M NaCl instead of 0.15M NaCl) MtbCspB retains the ability to bind to the RNA fragments but lost affinity to MTS0997 and MTS1338 sRNAs.

3. Discussion

In both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, stable sRNA:mRNA base pairing typically requires the assistance of RNA-chaperones like Hfq or ProQ [

9,

23]. These proteins are also involved in many aspects of RNA life, such as refolding, annealing, protection, activation or inhibition of the translation [

9]. However, mycobacterium species have been reported to lack genes encoding Hfq and ProQ in their chromosome [

11,

24], which suggests the need to investigate how sRNAs in mycobacterial species acquires stability inside the cells [

1]. Cold shock domain proteins (CSPs) are potential candidates for this role. Mycobacterium tuberculosis encodes two cold shock proteins, MtbCspA and MtbCspB. The main difference between them is that MtbCspB has a long C-terminus, which is predicted to form two α-helices.

We have shown that MtbCspB organizes a dimer in solution connecting pairs of the C-terminal α-helixes, which are form a stable four helixes bundle. This bundle is a rather common ternary structure for α-helical proteins, for example, ROP/ROM proteins. In contrast to MtbCspA [

20], this protein demonstrates remarkable affinity to RNAs. We dissected MtbCspB affinity for two sRNAs, which act as a key element for successful infection to its host – MTS0997 and MTS1338. Kinetic analysis has shown that these RNAs interact with MtbCspB dimer with a nanomolar dissociation constant (

Table 1). The affinity of MtbCspB for the short RNA with six uridines at 3’-end (oligoU RNA) is two orders of magnitude lower than for the studied sRNAs. The oligoU RNA is insufficient in length to bind to both parts of MtbCspB. Therefore, it can be hypothesized that the protein retains the ability to interact with oligoU RNA via the N-terminal cold shock domain, similar to its single-domain homologues. However, when MtbCspB bound to a large sRNA, the protein can interact with the protruding RNA via two N-terminal domains of the dimer, which significantly increases the affinity of MtbCspB for the RNA.

Chemical probing of the sRNAs in a complex with MtbCspB revealed that the reactivity of a number of nucleotides was changed (

Figure 4). This suggests that MtbCspB might both stabilize single-stranded regions of RNAs and protect them from RNAse degradation. In the case of MTS1338 MtbCspB protects nucleotides from modification, but in the case of MTS0997, nucleotide reactivity increases in the presence of MtbCspB. It’s worth mentioning that mature form of MTS1338 include 109 nt [

7], but in our experiments we used 117nt form of the sRNA. We found that most of the protected nucleotides are located at the 3’-end of MTS1338, so we could propose that MtbCspB may prevent the sRNA maturation.

To determine a minimal RNA fragment, which is sufficient to interact with the protein, we designed three various RNA fragments that should retain affinity for MtbCspB based on the chemical probing data and prediction of the RNAs secondary structure (Fig. 4). Considering that in case of MTS0997 reactivity of nucleotides increased in a presence of MtbCspB we supposed that protein-binding site is located near the identified nucleotides so we obtained the hairpin, which includes nucleotides 3-20 and 107-120 from original RNA sequence. In case of MTS1338 MtbCspB protects nucleotides from modification so we tried both to include these nucleotides to an RNA fragment and to obtain the most stable version of a fragment. The resulting fragments include nucleotides 29-48 and 65-100 from original RNA sequence. GCAA or CUUG tetraloops were used to close the cutting edges of the RNA fragments. The affinity of MtbCspB for the RNA fragments was measured in buffer of different ionic strength, 150 mM and 250 mM NaCl (

Table 2). In a buffer with 150 mM NaCl, the affinity of MtbCspB for the RNA fragments was two orders of magnitude lower than for the sRNAs, as was the case for oligoU RNA. In a buffer containing 250 mM NaCl, the RNA fragments retain their ability to bind MtbCspB, whereas full-lenght sRNA does not bind to MtbCspB under these conditions. This unexpected result can be explained by the fact that high ionic strength causes dissociation of the MtbCspB dimers, resulting in loss of affinity to full-length RNAs, but the affinity of the protein monomer for short RNA remains unchanged. It can be assumed that MtbCspB in the dimeric form first recognizes the spatial structure of RNA and then binds to a specific nucleotide sequence. In the case of RNA fragments containing these specific sequences, the MtbCspB monomer is sufficient for their recognition.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Gene Cloning, Expression and Purification of MtbCspB

The MtbCspB coding region was PCR-amplified from the M. tuberculosis genomic DNA (strain H37Rv, kindly provided by Dr. T. L. Azhikina, Shemyakin and Ovchinnikov Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry RAS) and cloned into the expression vector pET28a (Invitrogen) using NcoI and HindIII sites. The pET28a vector carrying the MtbCspB gene was used for transformation in E. coli BL21(DE3)/pRARE to express an C-terminal His6-tag protein. Transformed cells were grown in LB medium containing 50 μg/ml kanamycin and 10 μg/ml chloramphenicol at 37°C until the OD600 reached ~0.8. Protein expression was induced with 0.5 mM IPTG. After incubation for 3 hours at 37°C the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 8000g for 20 min at 4°C, resuspended in 40 ml lysis buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 8.0, 0.5 M NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 1 mM PMSF, 1 mM DTT, 0.1% Triton X-100) and disrupted by sonication (Fisher Scientific, USA). Cell membranes and ribosomes were precipitated using stepwise centrifugation at 14,000g for 20 min and at 90,000g for 50 min, respectively. Cleared lysates were loaded on a Ni-NTA Agarose (Qiagen, Germany) column equilibrated with 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 8.0, 0.2 M NaCl, 10 mM imidazole. The MtbCspB was eluted in a linear gradient of imidazole from 10 mM to 250 mM. Then protein-containing fractions were pooled and ammonium sulfate was added to a final concentration of 1.5M. The solution was applied to a Butyl-Sepharose (Cytiva, USA) equilibrated with 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1M NaCl, 1.5M ammonium sulfate. MtbCspB was eluted in a linear gradient of ammonium sulfate from 1.5M to 0M and NaCl from 1M to 200 mM. The last step of purifying was size-exclusion chromatography on HiLoad 16/60 Superdex 75 prep grade (GE Healthcare, Sweden), equilibrated with 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 200 mM NaCl. For crystallization experiments, the protein was lyophilized and then diluted with a size exclusion chromatography buffer to a final concentration 18 mg/ml.

4.2. Analysis of Protein Particle Size by Gel Filtration

For this analysis, we used an Acta Basic system (Amersham, UK) with Superdex 75 Increase column, 10/300 GL (Cytiva, USA), preliminary equilibrated with 200 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0. The protein sample (1 mg/ml, 100 μl) was injected into the column and eluted with velocity 0.5 ml/min. The calibration curve was modeled used gamma subunit of archaeal initiation factor aIF2γ from Sulfolobus solfataricus (45.8 kDa), ribosomal protein L1 from Thermus thermophilus (24.8 kDa), isolated domain I of L1 from T. thermophilus (15.4 kDa) and CspB from Bacillus subtilis (7.3 kDa).

4.3. Protein Crystallization

Crystallization experiments were carried out at 25 °C using the vapor diffusion method with hanging drops on siliconized glass cover slides in Libro plates. MtbCspB formed crystals under condition #B5 of Nuc-Pro 3 (1.7 M lithium sulfate, 50 mM HEPES sodium salt, pH 7.0, 50 mM magnesium sulfate, Jena Bioscience, Germany) used as a reservoir solution. Drops were made by mixing the protein solution with the reservoir solution in 1:1 volume ratios. Crystals appeared after 3 weeks and grew within 1 week. Before freezing in liquid nitrogen, the crystals were transferred to the mother liquor containing 37.5% glucose.

4.4. X-Ray Diffraction Data Collection and Processing

Diffraction data were collected on a Rigaku XtaLAB Synergy-S single-crystal diffractometer of the Center for Collective Use “Structural and Functional Studies of Proteins and RNA”, Institute of Protein Research RAS (Pushchino, Russia) under the control of the CrysalisPro program (Rigaku, Japan). The data were processed in space group P3121 using the CrysalisPro. The protein structure was determined by the molecular replacement with PHASER [

25] using the AlfaFold model (AF-I6WZM9-F1) of MtbCspB (UNIPROT I6WZM9) as a starting point. The asymmetric unit of the crystal cells contained a protein monomer. The structures were refined using REFMAC [

26] from the CCP4 package [

27]. Manual editing and modification of the models were carried out using COOT [

28]. Statistics of data collection and crystallographic refinement are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Kinetic constants and equilibrium dissociation constants (KD) of the MtbCspB-RNA fragments complexes in the buffer containing 150 mM or 250mM NaCl (*).

Table 3.

Kinetic constants and equilibrium dissociation constants (KD) of the MtbCspB-RNA fragments complexes in the buffer containing 150 mM or 250mM NaCl (*).

4.5. Cloning and Purification of RNAs

The MTS0997 and MTS1338 coding regions were amplified by PCR from the M. tuberculosis (strain H37Rv) genomic DNA and cloned into the vector pUC18 (Invitrogen, USA) using HindIII and XmaI sites; the forward primers additionally contained sequence the T7 promoter. DNA fragments corresponding to the sRNAs were obtained by PCR using pairs of overlapping primers. RNAs were obtained from linearized plasmid DNA by in vitro transcription with T7 RNA polymerase as described in [

29].

4.6. RNA Chemical Probing

Structural analysis of sRNAs alone (MTS0977 and MTS1338) or in the presence of MtbCspB was performed using chemical probing of RNA as previously described [

30].

4.6.1. Chemical Modifications of RNA

For the chemical probing experiment, we used two types of samples: individual RNAs and RNAs mixed with MtbCspB. RNAs were heated to 80°C for 10 min and cooled on ice before the addition of the protein. Then, RNAs (3 nmoles) were mixed with MtbCspB (6 nmoles) in a buffer containing 20 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 8.0 and 150 mM NaCl. Samples were incubated at room temperature for 30 min. Control (free RNA) samples were incubated identically. Modification reactions were carried out in 50 μl of 20 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 8.0 and 150 mM NaCl buffer containing RNA (750 pmol) or RNA with MtbCspB. The modifications was performed by addition of freshly prepared DMS (1 µL of a 1/5 dilution in ethanol), kethoxal (1 µL of a 1/5 dilution in ethanol), or CMCT (50 µL of 100 mg/mL in the reaction buffer) followed by incubation at 37°C for 10 min. Reactions were stopped by adding of stop-buffers followed by ethanol precipitation. DMS stop-buffer contained 1 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 M β-mercaptoethanol, and 100 mM sodium EDTA. CMCT stop-buffer contained 3 M sodium acetate. Kethoxal stop-buffer contained 150 mM sodium acetate and 250 mM H3BO3-KOH, pH 7.0. The RNAs were precipitated by ethanol and were washed with cold 70% ethanol. Pellets were dissolved in a buffer containing 25 mM H3BO3-KOH, pH 7.0, 300 mM sodium acetate, 0.5% SDS, and 5 mM sodium EDTA, followed by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. RNA pellets were dissolved in 10 µL of 25 mM H3BO3-KOH, pH 7.0. Control (unmodified) samples were treated in the same way as modified samples, except that the modification step was skipped. Unmodified RNAs were used as templates for the reference sequencing reactions and to monitor artifact stops or pauses in reverse transcription.

4.6.2. Fluorescent Primer Extension

RNA fragments used for chemical probing experiments contain identical 3'-end, which correspond to the pUC18 sequence between restriction sites SmaI and EcoRI (5'-GGGUACCGAGCUCGAAUUC-3'). A Cy5 fluorescent reverse transcription primer complementary to the 3'-end of the studied RNA fragments was purchased from Evrogen (Russia). For reverse transcription (RT), RNAs or modified RNAs (4 µL of a 1 µM solution) were added to the Cy5-primer (4 µL of a 2 µM solution) in an annealing buffer (250 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 200 mM KCl), heated to 90°C for 3 min, and slowly cooled to 37°C. RT reactions were performed in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 40 mM KCl, 6 mM MgCl2, and 2 mM each dNTP. M-MuLV Reverse Transcriptase 5 units (SibEnzyme, Russia) were added and reactions were incubated at 37°C for 60 min. For sequencing samples, 1 µM ddATP, ddCTP, ddGTP, or ddTTP were added to the RT reactions of each sample. Reactions were stopped by adding formamide with 10 mM EDTA, 0.3% bromophenol blue, and 0.3% xylenecyanol. Aliquots of 6–8 µL were analyzed in an 8% polyacrylamide gel in the presence of 8 M urea. Gels were visualized using the ChemiDoc MP Imaging System (Bio-Rad, USA).

4.7. Analysis of MtbCspB-RNA Interaction

Kinetic analysis of protein interaction with specific RNA fragments was performed by surface plasmon resonance technique [

31] using imSPR-Pro system (iCLUEBIO, Korea). MtbCspB was immobilized on the COOH-chip (iCLUEBIO, Korea) and five different concentrations of the analyte samples (RNAs) were prepared by serial dilution in a solution containing 20 mM HEPES-NaOH, pH 8.0, 150 mM or 250 mM NaCl, 10mM MgCl2 and 0.05 % Tween-20 for each set of sensorgrams. The samples were injected at a flow rate of 30 µL/min. The injection step included a 300s association phase followed by a 600 s dissociation phase in the buffer. Kinetic analysis was performed by globally fitting curves describing the simple 1:1 bimolecular model to a set of three to five sensorgrams using BIAEvaluation v. 4.1 software. As controls, biotinylated oligoU and oligoC were obtained as described [

21].

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.L. and A.N.; methodology, N.L. and A.M.; software, N.L., A.M., and A.N.; validation, N.L., A.M., and A.N..; formal analysis, N.L. and A.N.; investigation, N.L., A.M., and P.P.; resources, A.N.; data curation, N.L., A.M., and A.N.; writing—original draft preparation, N.L.; writing—review and editing, A.N.; visualization, N.L. and A.M.; supervision, A.N.; project administration, A.N.; funding acquisition, A.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by Russian Scientific Foundation, grant number 24–24–00071.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Azat Gabdulkhakov for the diffraction data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dutta, T.; Srivastava, S. Small RNA-Mediated Regulation in Bacteria: A Growing Palette of Diverse Mechanisms. Gene 2018, 656, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djapgne, L.; Oglesby, A.G. Impacts of Small RNAs and Their Chaperones on Bacterial Pathogenicity. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martini, B.A.; Grigorov, A.S.; Skvortsova, Y.V.; Bychenko, O.S.; Salina, E.G.; Azhikina, T.L. Small RNA MTS1338 Configures a Stress Resistance Signature in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azhikina, T.L.; Ignatov, D.V.; Salina, E.G.; Fursov, M.V.; Kaprelyants, A.S. Role of Small Noncoding RNAs in Bacterial Metabolism. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2015, 80, 1633–1646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnvig, K.B.; Young, D.B. Non-Coding RNA and Its Potential Role in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Pathogenesis. RNA Biol. 2012, 9, 427–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignatov, D.V.; Salina, E.G.; Fursov, M.V.; Skvortsov, T.A.; Azhikina, T.L.; Kaprelyants, A.S. Dormant Non-Culturable Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Retains Stable Low-Abundant MRNA. BMC Genomics 2015, 16, 954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moores, A.; Riesco, A.B.; Schwenk, S.; Arnvig, K.B. Expression, Maturation and Turnover of DrrS, an Unusually Stable, DosR Regulated Small RNA in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. PLoS One 2017, 12, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelly, S.; Bishai, W.R.; Lamichhane, G. A Screen for Non-Coding RNA in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis Reveals a CAMP-Responsive RNA That Is Expressed during Infection. Gene 2012, 500, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsuya-Gaviria, K.; Paris, G.; Dendooven, T.; Bandyra, K.J. Bacterial RNA Chaperones and Chaperone-like Riboregulators: Behind the Scenes of RNA-Mediated Regulation of Cellular Metabolism. RNA Biol. 2022, 19, 419–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, B.R.; Bardwell, J.C. Protein and RNA Chaperones. Mol. Aspects Med. 2025, 104, 101384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coskun, F.S.; Płociński, P.; van Oers, N.S.C. Small RNAs Asserting Big Roles in Mycobacteria. Non-Coding RNA 2021, 7, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taneja, S.; Dutta, T. On a Stake-out: Mycobacterial Small RNA Identification and Regulation. Non-coding RNA Res. 2019, 4, 86–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czapski, T.R.; Trun, N. Expression of Csp Genes in E. Coli K-12 in Defined Rich and Defined Minimal Media during Normal Growth, and after Cold-Shock. Gene 2014, 547, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamanaka, K.; Fang, L.; Inouye, M. The CspA Family in Escherichia Coli: Multiple Gene Duplication for Stress Adaptation. Mol. Microbiol. 1998, 27, 247–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bae, W.; Xia, B.; Inouye, M.; Severinov, K. Escherichia Coli CspA-Family RNA Chaperones Are Transcription Antiterminators. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 2000, 97, 7784–7789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuliodori, A.M.; Di Pietro, F.; Marzi, S.; Masquida, B.; Wagner, R.; Romby, P.; Gualerzi, C.O.; Pon, C.L. The CspA MRNA Is a Thermosensor That Modulates Translation of the Cold-Shock Protein CspA. Mol. Cell 2010, 37, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennella, E.; Sára, T.; Juen, M.; Wunderlich, C.; Imbert, L.; Solyom, Z.; Favier, A.; Ayala, I.; Weinhäupl, K.; Schanda, P.; et al. RNA Binding and Chaperone Activity of the E. Coli Cold-Shock Protein CspA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, 4255–4268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, W.; Hou, Y.; Inouye, M. CspA, the Major Cold-Shock Protein of Escherichia Coli, Is an RNA Chaperone. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 196–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Burkhardt, D.H.; Rouskin, S.; Li, G.; Weissman, J.S.; Gross, C.A. A Stress Response That Monitors and Regulates MRNA Structure Is Central to Cold Shock Adaptation. Mol. Cell 2018, 70, 274–286.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pankratova, P.Y.; Lekontseva, N.V.; Nikulin, A.D. Characterization of DNA/RNA Binding Properties of CspA Protein from Mycobacterium Tuberculosis. Silico Res. Biomed. 2025, 1, 100033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekontseva, N.; Mikhailina, A.; Fando, M.; Kravchenko, O.; Balobanov, V.; Tishchenko, S.; Nikulin, A. Crystal Structures and RNA-Binding Properties of Lsm Proteins from Archaea Sulfolobus Acidocaldarius and Methanococcus Vannielii: Similarity and Difference of the U-Binding Mode. Biochimie 2020, 175, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fando, M.S.; Mikhaylina, A.O.; Lekontseva, N.V.; Tishchenko, S.V.; Nikulin, A.D. Structure and RNA-Binding Properties of Lsm Protein from Halobacterium Salinarum. Biochemistry (Moscow) 2021, 86, 833–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jørgensen, M.G.; Pettersen, J.S.; Kallipolitis, B.H. SRNA-Mediated Control in Bacteria: An Increasing Diversity of Regulatory Mechanisms. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Gene Regul. Mech. 2020, 1863, 194504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwenk, S.; Arnvig, K.B. Regulatory RNA in Mycobacterium Tuberculosis, Back to Basics. Pathog. Dis. 2018, 76, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, A.J.; Grosse-Kunstleve, R.W.; Adams, P.D.; Winn, M.D.; Storoni, L.C.; Read, R.J. Phaser Crystallographic Software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2007, 40, 658–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murshudov, G.N.; Vagin, A.A.; Dodson, E.J. Refinement of Macromolecular Structures by the Maximum-Likelihood Method. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 1997, 53, 240–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winn, M.D.; Ballard, C.C.; Cowtan, K.D.; Dodson, E.J.; Emsley, P.; Evans, P.R.; Keegan, R.M.; Krissinel, E.B.; Leslie, A.G.W.; McCoy, A.; et al. Overview of the CCP4 Suite and Current Developments. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol. Crystallogr. 2011, 67, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emsley, P.; Cowtan, K. Coot : Model-Building Tools for Molecular Graphics. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2004, 60, 2126–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevskaya, N. Ribosomal Protein L1 Recognizes the Same Specific Structural Motif in Its Target Sites on the Autoregulatory MRNA and 23S RRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005, 33, 478–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, S.; Moazed, D.; Noller, H.F. Structural Analysis of RNA Using Chemical and Enzymatic Probing Monitored by Primer Extension. In Brenner’s Encyclopedia of Genetics; Elsevier, 1988; Vol. 164, pp. 481–489. ISBN 9780080961569. [Google Scholar]

- Katsamba, P.S.; Park, S.; Laird-Offringa, I.A. Kinetic Studies of RNA–Protein Interactions Using Surface Plasmon Resonance. Methods 2002, 26, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).