Submitted:

09 December 2025

Posted:

09 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. The Clinical Paradox of Karen

1.2. Limitations of Existing Behavioral and Cognitive Models

-

Behavioral models explain avoidance but not ignition failure.Foundational theories of depression, such as those by Ferster (1973) and Lewinsohn (1974), highlight how avoidance behaviors are maintained by the absence of reinforcing experiences. These models explain behavioral persistence but offer little insight into why action never initiates, even when reinforcement is anticipated and values are identified.

-

Reinforcement theory accounts for maintenance, not structural inertia.Karen’s environment lacked strong sources of reinforcement, as Hopko et al. (2011) observed. Yet the theory assumes that behavior begins and then extinguishes when reinforcement is insufficient. It does not explain why behavior fails to initiate in the first place, even when the task is small and the stakes are understood.

-

Cognitive models do not explain the action gap.Karen demonstrated insight into her depressive cycle and agreed with the logic of BA. Cognitive theories, such as Beck’s model or later appraisal frameworks, can explain rumination and negative schema but lack a mechanistic model for how understanding fails to convert into action. Insight is assumed to support change, but this assumption is not always borne out in practice.

-

Comorbidity increases friction but lacks structural specificity.Karen’s breast cancer and caregiving demands clearly increased her distress and emotional load. These contextual burdens may raise the “cost” of behavior, but they do not fully account for complete behavioral paralysis across all tasks and time points, especially when Karen remained engaged and verbally committed.

-

Emerging models address effort but remain partial.Recent frameworks in motivation science, such as Motivational Intensity Theory (Brehm & Self, 1989), the Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS) theory (Gray & McNaughton, 2000), and Reward Prediction Error (RPE) models (Montague et al., 1996; Huys et al., 2015), offer insights into how effort, salience, and action tendencies are modulated. However, they typically focus on value prediction, response inhibition, or cost–benefit analysis and lack a multivariable structure for explaining why effort fails to emerge even when the behavior is internally valued and externally supported.

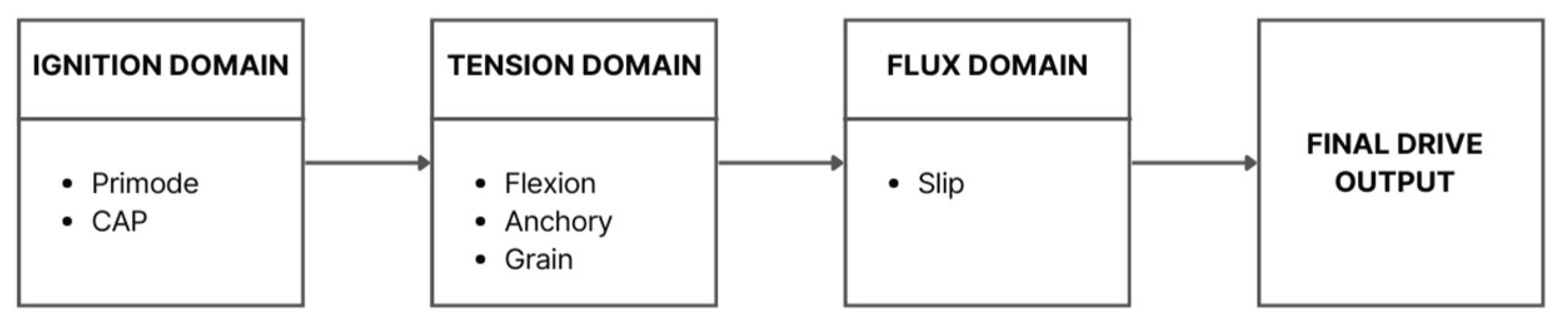

1.3. Structural Framework: Cognitive Drive Architecture (CDA)

- Primode: Governs whether task initiation is structurally possible

- CAP (Cognitive Activation Potential): Reflects available volitional energy

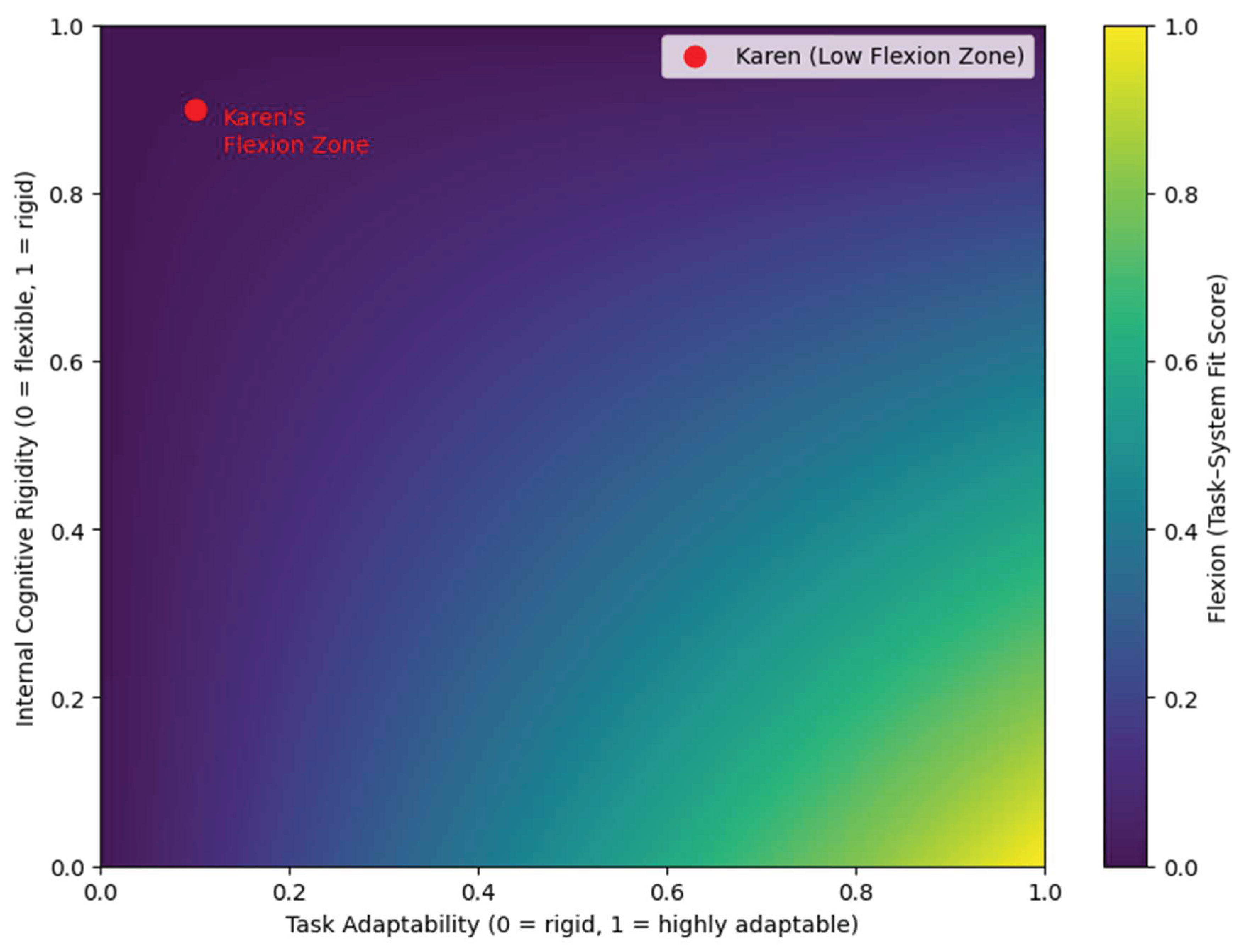

- Flexion: Measures the internal compatibility between the task and the self

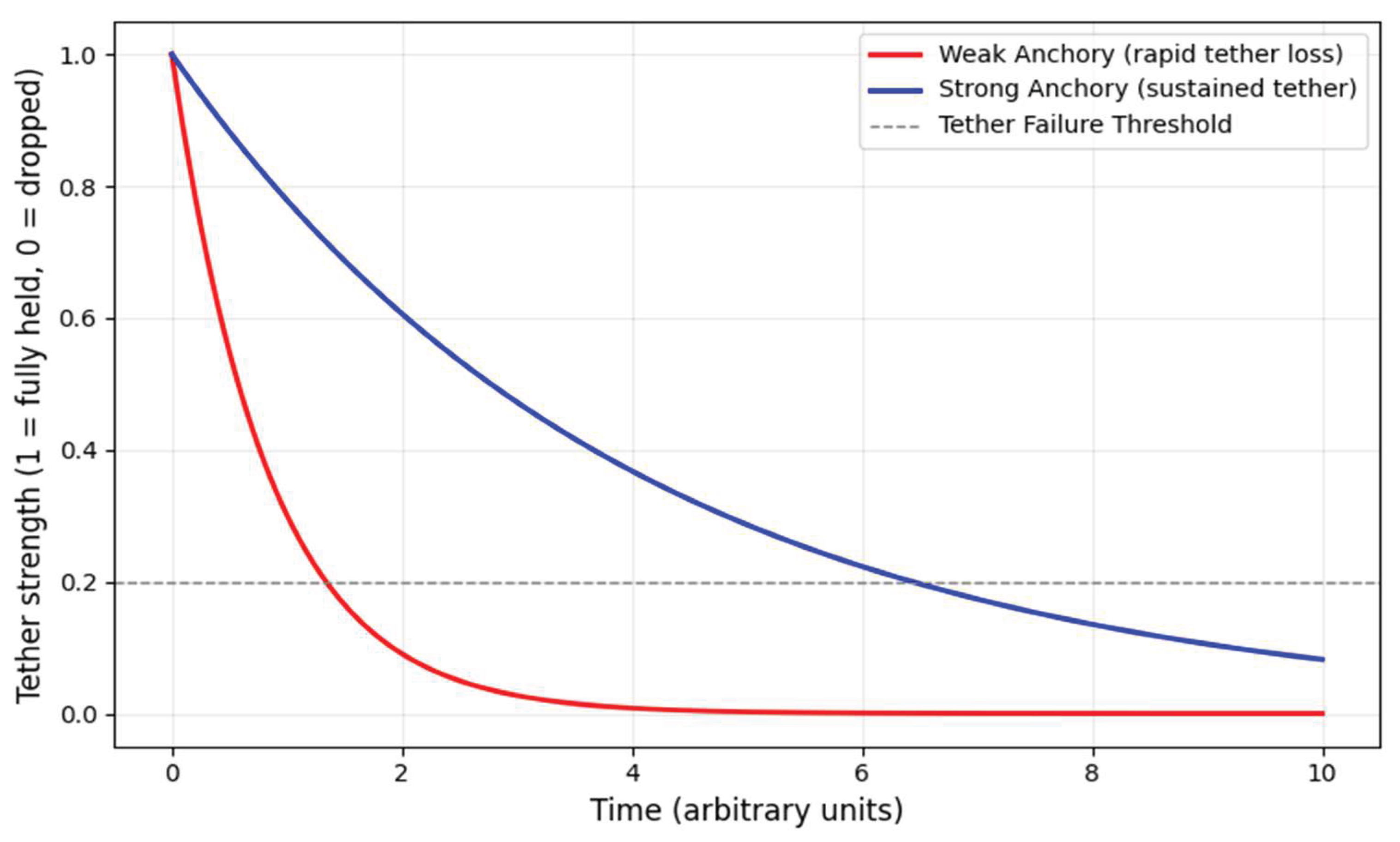

- Anchory: Supports attentional tethering and sustained focus

- Grain: Captures internal resistance or friction (e.g., emotional drag, shame, cognitive dissonance)

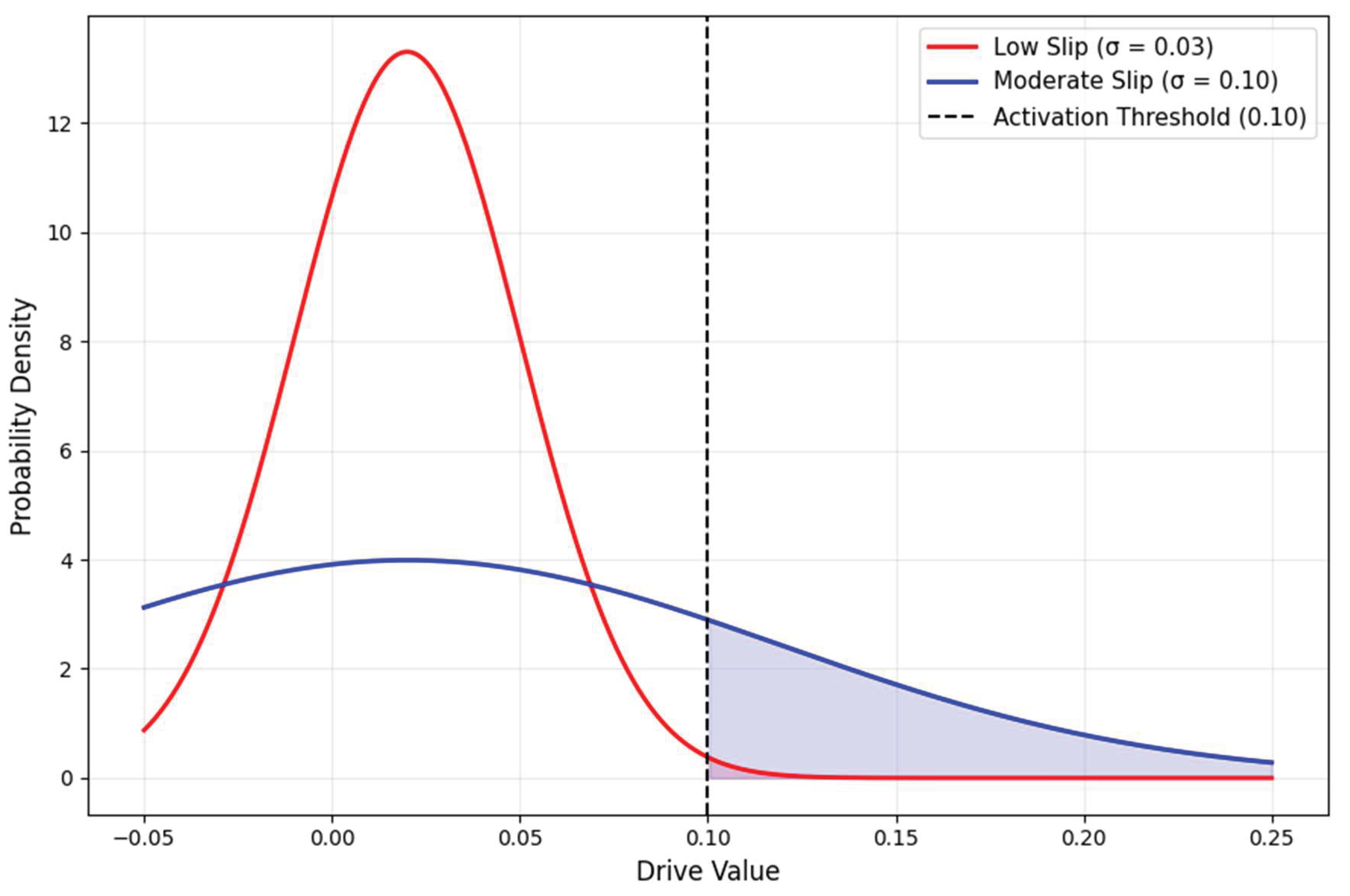

- Slip: Models behavioral variability or execution instability

- Ignition (Primode, CAP)

- Tension (Flexion, Anchory, Grain)

- Flux (Slip)

1.4. Purpose and Contribution of This Paper

- Reconstruct Karen’s Drive configuration using CDA and LTA

- Explain behavioral non-initiation as a structural misalignment rather than a motivational deficit

- Illustrate how variables like suppressed Primode, high Grain, and weak Anchory generate mechanical paralysis

- Offer a generalizable model for similar BA nonresponse cases, especially in high-load clinical populations

2. Method: Secondary Case Selection Approach

2.1. Case Source

2.2. Inclusion Criteria for Case Selection

- Motivational paradox: The patient demonstrated insight into BA principles, verbalized desire for behavioral change, and participated consistently in sessions, yet failed to initiate any behavioral tasks over a 12-session course. This paradox is a hallmark indicator of potential ignition failure within the CDA framework.

- High-resolution process documentation: The original case report includes session-by-session descriptions of values clarification, behavioral task planning, psychoeducation delivery, and client–therapist interaction. This granularity enables reliable mapping of CDA variables to real clinical moments.

- Explicit recognition of treatment nonresponse: Hopko et al. (2011) openly acknowledged that the patient’s inactivity was difficult to reconcile with standard behavioral models. Their transparency makes the case ideal for reanalysis via an alternative structure-oriented lens.

- Contextual complexity and load: The patient faced multifactorial adversity, including a breast cancer diagnosis, caregiving responsibilities, and reduced social-emotional reinforcement. These conditions are ideal for the application of Latent Task Architecture (LTA), a domain-specific extension of CDA that models how load and internal friction compound to suppress behavioral readiness (Lagun, 2025c).

2.3. Data Extraction and Mapping Procedure

- Behavioral Observations: Patterns of withdrawal, inactivity, sleep regulation, and instances of attempted activation.

- Values Exploration: Patient statements during values exercises, including role identity narrowing and difficulty articulating self-relevant goals beyond caregiving.

- Compliance and Activation: Completion of tasks, homework adherence, initiation of scheduled behaviors, and therapeutic documentation of missed or incomplete assignments.

- Treatment Engagement: The patient’s expressed understanding of BA concepts, responses to psychoeducation, and affective resonance with intervention logic.

2.4. Ethical Compliance

3. Summary of the Original Case

3.1. Patient Background

3.2. Psychiatric Presentation

3.3. Behavioral Activation Protocol: Components and Implementation

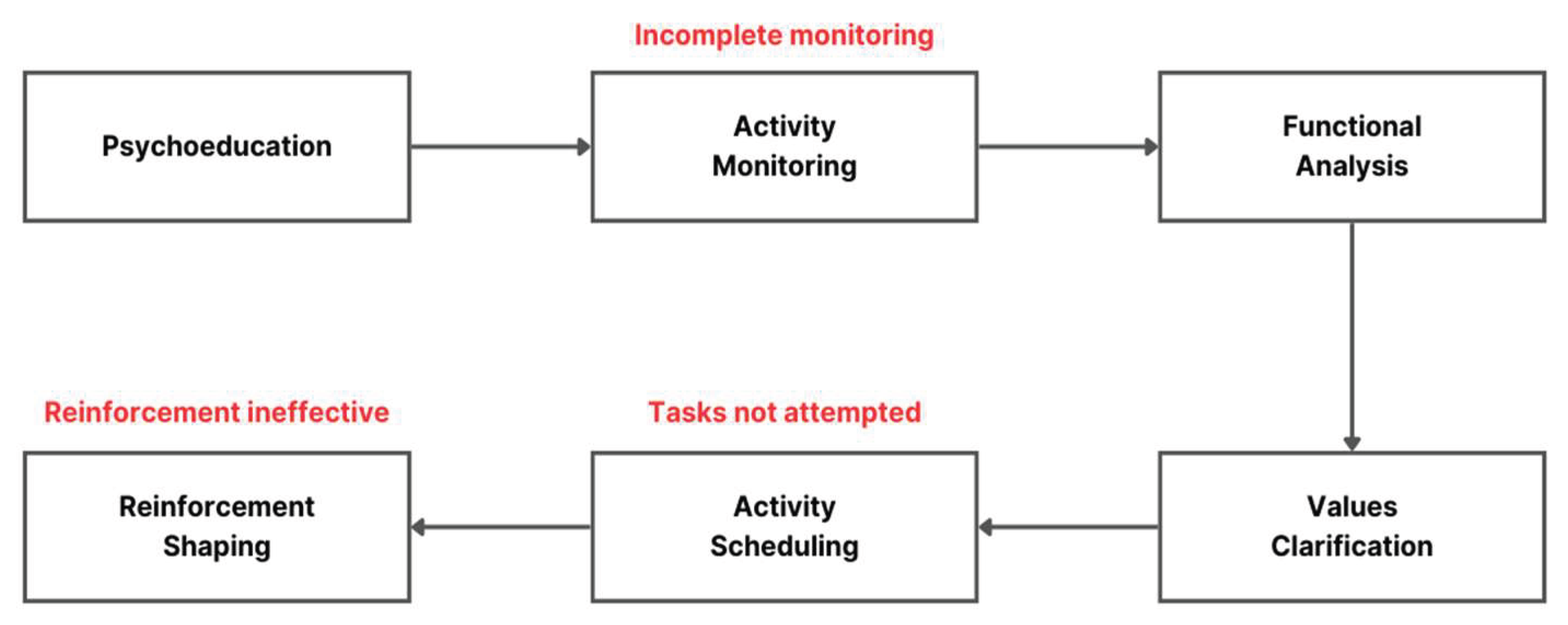

- Psychoeducation: Karen was introduced to the foundational principles of BA, namely, the role of avoidance in sustaining depression and the premise that behavioral engagement precedes mood improvement.

- Activity Monitoring: She was asked to log daily behaviors and emotional states, with the goal of identifying avoidance patterns and opportunities for behavioral reinforcement.

- Functional Analysis: Sessions explored the antecedents and consequences of specific behaviors, seeking to uncover how inaction or avoidance was being maintained in her routine.

- Values Clarification: The therapist facilitated reflection on life domains that Karen found meaningful, using these values as anchors for later behavioral planning.

- Activity Scheduling: Together, the therapist and patient designed simple, values-aligned behavioral tasks to be implemented between sessions.

- Reinforcement Shaping: The therapist attempted to involve Karen’s husband in encouraging activation by positively reinforcing her efforts and engagement.

3.4. Documented Process Challenges

- Incomplete Activity Logs: Karen frequently returned without having completed her activity or mood monitoring sheets. This limited the therapist’s ability to identify avoidance patterns or calibrate future tasks based on real data.

- Values Identification Difficulties: When prompted to articulate core values, Karen focused exclusively on caregiving. She struggled to name goals or sources of meaning outside this role, restricting the range of behaviors that could be targeted for activation.

- Lack of Behavioral Follow-Through: Although activities were collaboratively scheduled and tailored to be feasible, Karen reported not attempting them. She cited fatigue, self-doubt, and a persisting belief that mood must improve before action could occur.

- Limited External Reinforcement: Efforts to involve her husband in reinforcement strategies were unsuccessful. His emotional unavailability created an environment where even attempted behaviors received little acknowledgment, and her depressive withdrawal was sometimes unintentionally reinforced.

3.5. Clinical Outcome

4. CDA Reinterpretation (Core Analysis)

- Primode: ignition threshold, determining whether action can begin at all (e.g., the system’s behavioral “spark plug”).

- CAP (Cognitive Activation Potential): emotional-volitional “voltage” that amplifies Primode exponentially.

- Flexion: degree of fit between the task and the individual’s cognitive configuration (task-to-self alignment).

- Anchory: strength of attentional tethering required to sustain effort (mental grip or tethering).

- Grain: internal friction: emotional drag, fatigue, shame, or contextual burden (like running through molasses).

- Slip: baseline system variance affecting behavioral consistency.

-

If Primode = 0, the entire Drive collapses to near-zero regardless of CAP or Flexion.

- ○

- This is mathematically embedded:

- High Grain in the denominator reduces Drive yield, even when all other variables are favorable.

- CAP amplifies Primode nonlinearly, meaning emotional energy only matters if ignition is already possible.

- Slip adds behavioral variability but cannot compensate for a zeroed ignition system.

- No initiation of any BA task → Primode ≈ 0

- Expression of desire to improve → CAP > 0, but low amplitude

- Activities felt incompatible with identity and physical state → Flexion low

- Inconsistent monitoring, rapid drift → Anchory low

- Hopelessness, fatigue, caregiving burden → Grain extremely high

- Stable inactivity → Slip low

- Each variable will now be mapped to concrete behaviors reported in the original case.

- The Drive Equation constrains interpretation, ensuring we do not over-attribute any single variable.

- It clarifies how multivariate interactions produce simple clinical outcomes (in this case, non-activation).

- It sets the stage for explaining contradictions that BA could not organize without critiquing the BA model itself, which was never designed to model ignition mechanics.

4.1. Primode: Structural Ignition Blockade

4.1.1. Behavioral Evidence of Primode Suppression

- 1.

-

No assignment was ever initiated between sessions

- a.

- No walks.

- b.

- No calls to friends.

- c.

- No completion of monitoring logs.

- d.

- No attempts at value-aligned actions.

- 2.

-

Her verbal reasoning revealed an ignition gateKaren repeatedly said variants of:“I can’t start until I feel better.”This belief acts as a cognitive key that locks the ignition system. In CDA, such a belief is not a thought error; it is a structural permission rule. If the internal rule for action is “mood → action” and the treatment rule is “action → mood,” the ignition point is blocked by a contradictory gate condition.

- 3.

-

Medical burden created physiological Primode inhibitionBreast cancer and associated fatigue significantly reduced Karen’s internal availability for task initiation. In CDA, severe fatigue reduces Primode independent of motivation:If energy availability is extremely low, Primode stays below the threshold even if CAP is moderate.

- 4.

- Caregiving identity created a second permission blockadeKaren’s self-concept of “caregiver first, self never” meant that initiating self-directed action required violating an internalized role. Within CDA, identity-based permission rules are part of the Primode structure.

4.1.2. Structural Interpretation Using the Drive Equation

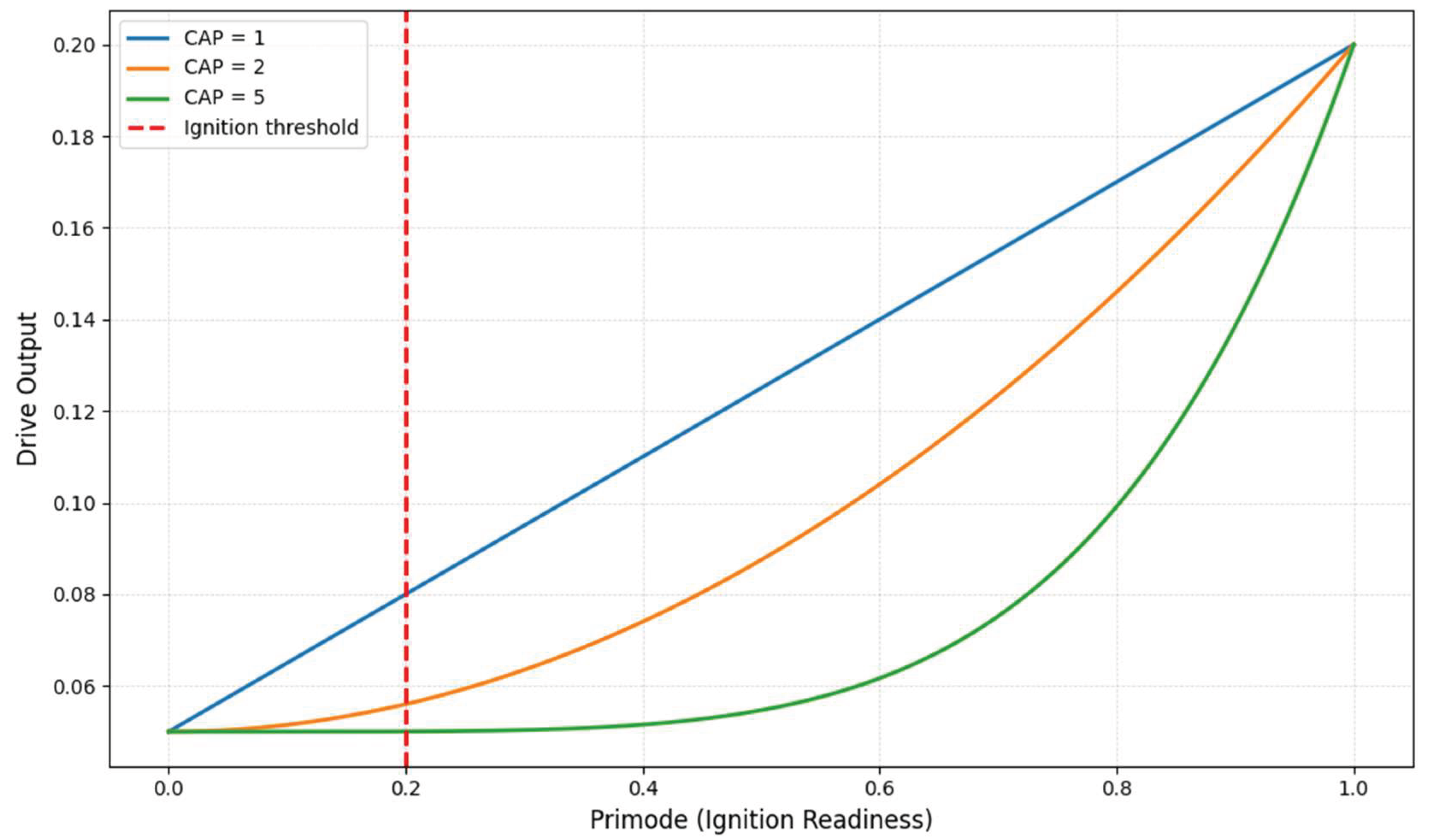

Assume (based on case patterns):

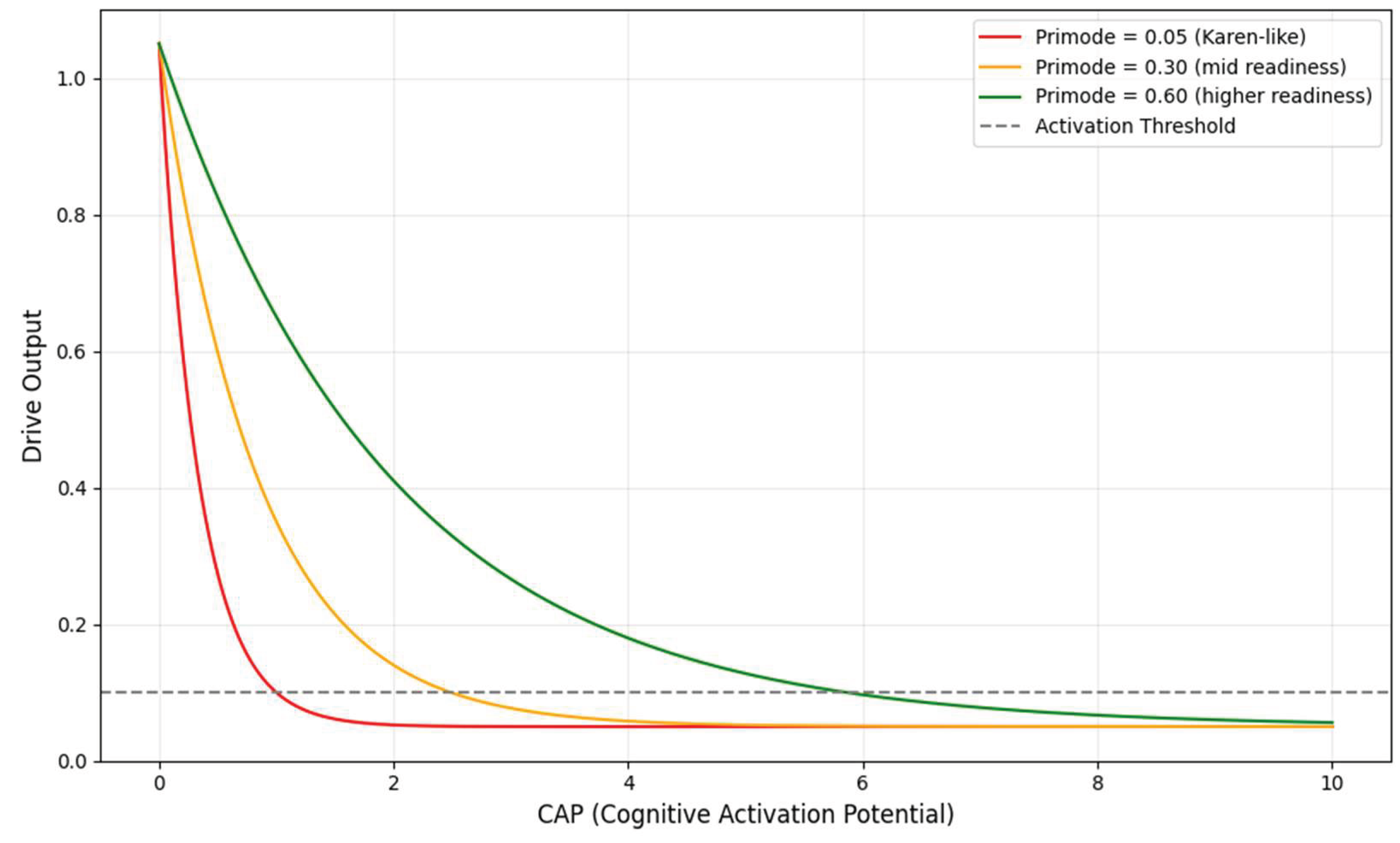

- Primode = 0.05 (near zero; ignition not available)

- CAP = 2 (she wanted to improve, but emotional voltage low)

- Flexion = 0.3 (tasks felt mismatched)

- Anchory = 0.2 (weak tethering)

- Grain = 1.8 (high emotional friction)

- Slip = 0.05 (rigid, stable depressive pattern)

4.1.3. Why Primode Remained Near Zero in Karen’s System

- 1.

- Cancer-related fatiguePhysical depletion lowered readiness so severely that initiation was structurally impossible, not merely difficult.

- 2.

- Emotional gating rule: “Mood must improve first”This rule set the ignition threshold infinitely high. Primode cannot rise when the system believes it must wait.

- 3.

- Caregiving load and self-permission deficitKaren implicitly deprived herself of permission to allocate energy toward her own well-being.

- 4.

- Absence of reinforcing environmentAlthough this affects Grain and Anchory more directly, it indirectly reduced Primode by removing any anticipatory sense of reward.

4.1.4. Why BA Could Not Explain This but CDA Can

- Once a patient understands the rationale,

- And values are identified or clarified,

- She understood the rationale (cognition intact),

- She endorsed the goal (motivation intact),

- The therapist delivered the protocol correctly (method intact),

What CDA provides

- No task begins,

- No amount of motivation produces action,

- No scheduling yields behavior,

- No reinforcement becomes available (because nothing happens to reinforce).

4.2. CAP: Activation Potential Misalignment

4.2.1. Evidence of Low CAP Despite Verbal Desire

- 1.

-

Emotional flatnessKaren acknowledged BA principles but did not appear emotionally mobilized by them. She “understood but did not internalize” the rationale. Emotional resonance is a key contributor to CAP; without it, initiation energy stays weak.

- 2.

-

Hopelessness as a CAP dampenerShe frequently described her situation as overwhelming and doubted that small actions would make any difference. Hopelessness suppresses CAP by reducing the internal sense that action is consequential.

- 3.

-

Cancer-related fatigueThe physical burden of cancer treatment depleted not only physical energy but also emotional voltage. Chronic fatigue has a direct lowering effect on CAP because it reduces the moment-to-moment energetic availability required for ignition.

- 4.

-

Lack of reinforcing social contextIn CDA, CAP is influenced by anticipated emotional return. Since Karen’s environment offered little reinforcement, her husband was emotionally unavailable, her daughter uninvolved, and her internal activation potential had no anticipatory signal to rise. Together, these factors indicate a persistent CAP value below the minimum needed to meaningfully amplify Primode.

4.2.2. Structural Interpretation Using the Drive Equation

Example Simulation Based on Karen’s Presentation

- Primode ≈ 0.05

- CAP ≈ 2 (reflecting desire without emotional ignition)

- Flexion ≈ 0.3

- Anchory + Grain ≈ 2.0

- Slip ≈ 0.05

Case A: CAP = 2 (likely Karen’s range)

Case B: CAP = 4 (hypothetical strong emotional voltage)

Case C: CAP = 10 (extremely high voltage for illustration)

Interpretation

- CAP was not strong enough to overcome extraordinarily high Grain.

- CAP was not volatile enough to produce spontaneous small actions.

- CAP could not amplify Primode because Primode itself was suppressed.

4.2.3. Depression’s Effect on CAP: Emotional Amplitude Flattening

- Hopelessness constricted upward CAP fluctuations.

- Emotional numbing reduced the “spark” that normally initiates new behavior.

- Fatigue lowered the voltage supply itself.

- Contextual invalidation (lack of familial reinforcement) prevented CAP surges.

4.2.4. Why BA Could Not Explain This but CDA Can

Limitations of BA Regarding CAP

- motivation becomes behaviorally usable,

- emotional readiness is sufficient for small steps,

- the patient possesses enough internal energy to begin scheduled tasks.

- verbal desire and

- activation voltage capable of initiating behavior.

How CDA Clarifies the Paradox

- Motivation = conceptual desire.

- CAP = ignition voltage.

- A person can sincerely want change,

- Understand the treatment model,

- Agree to try new behaviors and still produce zero activation.

4.3. Flexion: Task–System Misfit

4.3.1. Behavioral Evidence of Flexion Failure

- 1.

-

Global rejection of tasks regardless of size or contentKaren declined nearly all behavioral tasks assigned during BA, including the smallest possible ones:

- a.

- a few minutes of walking,

- b.

- calling a friend,

- c.

- writing brief notes,

- d.

- completing monitoring sheets.

She did not reject tasks strategically but globally. This pattern indicates low Flexion; her system could not adjust or reshape the task demands to her internal state. - 2.

-

“Not worth it,” “not possible right now,” “too tired” responsesThese phrases appeared repeatedly in session summaries (Hopko et al., 2011). In CDA, these responses indicate that the task geometry felt incompatible with her present cognitive and physiological configuration.A high-Flexion system would say, “Maybe I’ll try a smaller version.” A low-Flexion system says only, “No.”Karen consistently produced the latter.

- 3.

-

Narrowed values space (caregiving identity only)Karen struggled to identify any value outside her caregiving role. She did not articulate values related to:

- a.

- personal health

- b.

- emotional restoration

- c.

- social connection

- d.

- autonomy or competence

This severe narrowing of valued domains leaves BA with almost no “flexible handles” to map tasks onto. When values collapse, Flexion collapses with them. - 4.

-

Physical fatigue eliminating cognitive task adaptabilityCancer-related fatigue limited not just her energy but also her adaptability. Hopko et al. (2011) describe her as “exhausted,” “worn down,” and “overwhelmed.” In CDA, physical exhaustion directly constrains Flexion by reducing:

- a.

- cognitive bandwidth,

- b.

- emotional responsiveness,

- c.

- capacity for micro-adjustments in task shape.

A fatigued system cannot reconfigure tasks well. - 5.

-

Lack of generative alternativesPatients with moderate Flexion usually propose alternative activity forms:

- a.

- shorter versions,

- b.

- different times,

- c.

- different contexts,

- d.

- different people.

Karen generated almost no alternatives. This absence is a direct behavioral signature of Flexion deficiency.

4.3.2. Structural Interpretation of Flexion in Karen’s System

- 1.

- Identity rigidity (“caregiver first, self last”)

- 2.

-

Emotional hopelessness rigidified cognitive configurationHopko et al. (2011) note repeated expressions of hopelessness and futility. Hopelessness reduces:

- a.

- openness to reinterpreting tasks,

- b.

- willingness to experiment,

- c.

- tolerance for ambiguity.

This flattens the internal landscape, leaving tasks unable to fit. - 3.

-

Physical burden reduced degrees of freedomFatigue limited not only capacity but also adaptability. Karen’s system had fewer “degrees of freedom” to transform a task into something executable.

- 4.

-

Values constriction blocked task adaptationBecause her values map contained a single node (caregiving), tasks that did not directly serve that role felt meaningless. Tasks without perceived meaning cannot bend to fit.

4.3.3. Numerical Illustration: Flexion Near Zero

- 1.0 = high adaptability

- 0.5 = moderate adaptability

- 0.1 = extremely low adaptability

- A “small” task remains effectively the same size.

- A “modifiable” task cannot be modified.

- A “low-cost” task feels high-cost.

4.3.4. How Flexion Explains Key Clinical Confusions

-

Why cognitive understanding did not translate into behaviorBA assumes that once rationale and values are understood, patients can adapt tasks to their lives. Karen understood but could not adapt.

-

Why values clarification failed to generate meaningful actionsValues clarification failed not because Karen lacked values but because her value structure was too narrow to support flexible actions. Flexion requires multiple value anchors. She had one.

-

Why “simple tasks” were rejected alongside “bigger tasks”Across all assignments, rejection was uniform. Flexion explains this uniformity: if a system cannot adapt to tasks, its size does not matter.

-

Why no “micro-steps” emerged despite therapist supportMicro-stepping requires Flexion. Karen consistently showed none.

4.3.5. Why BA Could Not Explain This but CDA Can

Limitations of BA’s conceptual tools

- patients can flexibly choose and modify tasks once values are clarified;

- even fatigued or depressed patients can scale tasks down;

- values produce a menu of possible actions.

What CDA clarifies

- high (tasks feel shapeable),

- moderate (tasks can be adapted with effort),

- low (tasks feel rigid or impossible),

- near zero (task geometry collapses entirely).

4.4. Anchory: Tethering Breakdown

4.4.1. Behavioral Evidence of Tether Fragility

- 1.

-

Highly inconsistent attention to BA tasksKaren demonstrated immediate attentional collapse across nearly every assignment:

- a.

- Activity logs were rarely completed.

- b.

- Monitoring sheets returned blank even after multiple reminders.

- c.

- Tasks discussed in session were forgotten by the next session.

This is not inattentiveness in the cognitive sense. It is tethering collapse. - 2.

-

Rapid drift back into habitual avoidanceHopko et al. (2011) note that Karen often reverted to sleeping in, withdrawing, or remaining inactive. This drift occurred not after attempting tasks, but instead of any attempt at all. Low Anchory means intentions cannot be “held in working engagement” long enough to manifest behavior.

- 3.

-

In-session engagement did not carry overKaren was described as attentive and cooperative during sessions. Yet this attentional engagement was extremely context-bound: it dissolved as soon as the session ended. This session-bound engagement profile is a hallmark of weak Anchory: attention can be established but not retained.

- 4.

-

Fatigue-induced micro-lapsesSevere fatigue from cancer treatment would have weakened her ability to sustain even brief cognitive anchoring. Fatigue does not just reduce energy. It erodes attentional tether strength.

- 5.

-

No evidence of spontaneous re-engagementIndividuals with moderate Anchory may drift but later return to tasks. Karen did not spontaneously resume any BA task once attention lapsed, further indicating a system that cannot re-anchor without external scaffolding.

4.4.2. Structural Interpretation of Anchory in Karen’s System

Illustrative anchoring breakdown

- Intentions evaporate quickly.

- Engagement cannot survive even minor emotional or cognitive interruptions.

- Tasks require external scaffolding to remain in awareness.

- Internal cues fail to trigger task recall.

- Activation falters even before Grain exerts influence.

Interaction with Depression

- lowering cognitive persistence,

- reducing attentional stability,

- increasing mental fatigue,

- increasing susceptibility to emotional drift.

4.4.3. Clinical Patterns Explained by Low Anchory

- 1.

-

Incomplete activity logs despite repeated promptsBA relies heavily on monitoring as the first behavioral foothold. Karen’s inability to complete logs, even when she verbally agreed, indicates not oppositionality but failure of attentional tethering.

- 2.

-

“I forgot” as genuine structural outputKaren often returned saying she “forgot” or “never got around” to an activity. These are behavioral signatures of weak Anchory, not poor motivation.

- 3.

-

The disconnect between in-session clarity and out-of-session absenceKaren could discuss tasks coherently in session; Anchory is temporarily stabilized by therapist structure, but structural tethering collapsed outside that scaffold.

- 4.

-

Drift back to habitual patterns without attempting alternativesAnchory enables shift maintenance, not shift initiation. Karen could shift cognitively (in-session) but could not maintain the shift long enough to enact behavior (out-of-session).

- 5.

- Fatigue amplifying tether fragility

4.4.4 Numerical Illustration: Anchory Too Weak to Support Behavior

- Primode ≈ 0.05

- CAP ≈ 2

- Flexion ≈ 0.1

- Grain ≈ 1.8

- Slip ≈ 0.05

Case A: Anchory = 0.2 (likely Karen)

Case B: Anchory = 0.5 (moderate tethering)

- partial micro-tasks,

- occasional log attempts,

- intermittent inconsistent activation.

Case C: Anchory = 0.8 (strong tethering)

- values to persist as guides,

- assignments to stay cognitively alive,

- tasks to be retried.

4.4.5. Why BA Could Not Explain This but CDA Can

Limitations of BA

- once tasks are scheduled,

- once values are clear,

- and once rationale is accepted,

- motivational deficits,

- task aversiveness, or

- emotional avoidance.

What CDA Clarifies

- Activation cannot survive without attentional tethering.

- Even moderate motivation (CAP) cannot overcome low Anchory.

- Session-based insight cannot transfer if Anchory collapses between sessions.

- Systems with Anchory < threshold produce precisely the behavioral pattern Karen displayed.

4.5. Grain: Internal Resistance and Emotional Friction

4.5.1. Behavioral and Contextual Evidence of High Grain

- 1.

-

HopelessnessKaren frequently described her situation as unchangeable and doubted that behavioral attempts would produce relief. This emotional stance creates significant resistance, as each action is filtered through futility.

- 2.

-

Medical fatigueCancer-related exhaustion made even minor tasks feel physically overwhelming. Physiological depletion increases internal friction, reducing the capacity to convert intention into movement.

- 3.

-

Caregiving burdenHer identity as the primary caregiver created internal conflict around self-directed actions. Tasks aimed at improving her well-being competed against a firmly held role expectation, generating guilt-based resistance.

- 4.

-

Lack of environmental reinforcementHer husband was emotionally unavailable, and her daughter did not participate in supporting change. The absence of anticipated reinforcement amplifies Grain, as the system predicts no external payoff for effort.

- 5.

-

Fear of failure and shameKaren expressed concern that attempting tasks might confirm personal inadequacy. This anticipation of emotional pain adds another layer of resistance.These elements interacted to create a sustained, high-resistance state.

4.5.2. Structural Interpretation of Grain’s Effect

- Primode = 0.4

- CAP = 2

- Flexion = 0.3

- Anchory = 0.2

- Slip = 0.05

Case A: Lower resistance (Grain = 0.5)

Case B: Higher resistance (Grain = 1.8)

4.5.3. Clinical Meaning of High Grain in This Case

- Tasks felt pointless, not simply difficult, because hopelessness blocked perceived value.

- Fatigue amplified resistance, making even micro-activities feel burdensome.

- Caregiver identity conflicted with self-directed action, creating internal prohibitions.

- A non-reinforcing environment removed the anticipated reward, reducing the likelihood of sustained engagement.

- Shame and fear of failure added emotional cost to every possible action.

4.5.4. Why BA Could Not Explain This but CDA Can

4.6. Slip: Variability and Performance Entropy

4.6.1. Behavioral Evidence of Suppressed Variability

- 1.

-

Uniform absence of task attemptsNone of the scheduled activities were attempted, not once. There were no partial walks, no half-completed logs, and no “I tried but couldn’t finish.” This level of uniformity is characteristic of low variability.

- 2.

-

Stable daily routineHer behavior remained dominated by extended sleep, withdrawal, and sustained inactivity. Hopko et al. (2011) do not describe alternating “better days” of relative engagement; patterns were steady and fixed.

- 3.

-

No spontaneous micro-experimentsDepressed patients with moderate Slip often make unintended attempts (e.g., answering one call, stepping outside briefly, writing down a few activities). Karen did not show this kind of accidental behavioral noise.

- 4.

-

Emotional and energetic flatnessHer hopelessness and fatigue were persistent, with little documented fluctuation. Slip is often mirrored by emotional variability; a flat emotional profile suggests reduced entropy.

4.6.2. Structural Role of Slip in the System

- near-zero Primode,

- low CAP,

- low Flexion,

- weak Anchory,

- high Grain,

4.6.3. Numerical Illustration: Slip as Variability Around a Fixed Baseline

- the deterministic part of Drive (from Primode, CAP, Flexion, Anchory, Grain) is near zero, say, 0.02,

- Slip represents a random fluctuation around this baseline.

- Baseline Drive (without Slip) = 0.02

- Activation threshold = 0.10

Case A: Very low Slip (e.g.,)

Case B: Moderate Slip (e.g., s=0.10s = 0.10s=0.10)

4.6.4. Clinical Meaning of Low Slip in Karen’s Case

-

Inertia becomes absoluteWith minimal variability, the system remains locked in its dominant pattern, in this case, avoidance and withdrawal.

-

No footholds for reinforcement emergeBA needs at least one or two behaviors to reinforce. Without occasional deviations, there is nothing to shape.

-

Insight cannot “leak” into behaviorIn-session understanding may fluctuate slightly, but low Slip prevents these fluctuations from producing observable actions between sessions.

-

Rigidity becomes the default stateEven if the rest of the architecture changes slightly, low Slip keeps behavior nearly constant.

4.6.5. Why BA Could Not Explain This but CDA Can

- spontaneous deviations from avoidance almost never occur,

- accidental successes are rare to nonexistent,

- the system generates a flat behavioral output even in the presence of insight and desire.

5. Structural Integration

5.1. Reconstructing Karen’s Drive Architecture

- Primode: effectively zero, no ignition; no assignments initiated

- CAP: low, desire present but insufficient emotional–volitional energy

- Flexion: very poor, tasks did not fit her internal cognitive or emotional state

- Anchory: fragile, intentions dissipated rapidly outside the structured session context

- Grain: extremely high, persistent resistance from hopelessness, fatigue, role guilt, and lack of reinforcement

- Slip: low, minimal variability; no spontaneous attempts or deviations from avoidance

5.2. How These Variables Interact to Produce Total Inactivity

-

Primode remained below ignition thresholdWithout ignition readiness, no action can begin, regardless of motivation or insight.

-

Grain dominated the systemEmotional despair, physical exhaustion, caregiving strain, and a non-reinforcing home environment created a high-resistance field that absorbed nearly all available activation.

-

Low CAP provided insufficient voltageKaren wanted improvement but lacked the emotional energy to overcome resistance.

-

Flexion collapse prevented task adaptationBA assignments could not be reshaped into forms compatible with her depleted internal resources or rigid caregiver identity.

-

Weak Anchory prevented intentions from surviving between sessionsEngagement inside the therapy room did not translate into sustained action afterward.

-

Low Slip removed spontaneous chances for successWithout variability, no accidental or partial behaviors could emerge to generate momentum.

5.3. Why BA Failed Coherently Within This Architecture

- at least some ignition capacity (Primode > 0),

- sufficient emotional energy to support action,

- meaningful flexibility in how tasks are performed,

- the ability to hold task intentions between sessions, and

- enough variability for occasional success

- Low Primode

- Low CAP

- Low Flexion

- Weak Anchory

- High Grain

- Low Slip

5.4. If the Case Were Evaluated Today

- High Grain

- Near-zero Primode

- Weak Anchory

- Low Flexion

- Minimal Slip

6. Implications for Understanding & Treatment

6.1. Rethinking Treatment-Resistant Depression Through Structure

6.2. Grain Reduction as a Prerequisite to Activation

- Medical comorbidity

- Chronic fatigue

- Identity-based self-pressure

- Emotional hopelessness

- Low-reinforcement environments

6.3. Flexion as a Determinant of Task Feasibility

6.4. Anchory Support as a Structural Foundation

- Environmental scaffolding

- Simplified intention structures

- Micro-tethering strategies

6.5. Structural Assessment Before Intervention Selection

- Primode → Initiation latency tasks

- CAP → Emotional–volitional intensity scales

- Flexion → Task-fit/load questionnaires

- Anchory → Sustained attention metrics

- Grain → Friction, burden, or fatigue indices

- Slip → Variability and micro-fluctuation analysis

8.6. Toward a CDA-Aligned Intervention Framework

- Standardized tools for Drive-state assessment

- Procedures for Grain (resistance) reduction

- Ignition and Anchory support techniques

- Micro-interventions targeting Flexion and stabilizing Slip

7. Conclusion

Funding

Conflict of interest

Ethical approval

Data availability

References

- Brehm, J. W., & Self, E. A. (1989). The intensity of motivation. Annual review of psychology, 40, 109–131. [CrossRef]

- Dimidjian, S., Hollon, S. D., Dobson, K. S., Schmaling, K. B., Kohlenberg, R. J., Addis, M. E., Gallop, R., McGlinchey, J. B., Markley, D. K., Gollan, J. K., Atkins, D. C., Dunner, D. L., & Jacobson, N. S. (2006). Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the acute treatment of adults with major depression. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 74(4), 658–670. [CrossRef]

- Ferster, C. B. (1973). A functional analysis of depression. American Psychologist, 28(10), 857–870. [CrossRef]

- Gray, J.A. and McNaughton, N. (2000). The neuropsychology of anxiety: An enquiry into the functions of the septo-hippocampal system. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Hopko, D. R., Magidson, J. F., & Lejuez, C. W. (2011). Treatment failure in behavior therapy: focus on behavioral activation for depression. Journal of clinical psychology, 67(11), 1106–1116. [CrossRef]

- Huys, Q. J., Daw, N. D., & Dayan, P. (2015). Depression: a decision-theoretic analysis. Annual review of neuroscience, 38, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, N. S., Dobson, K. S., Truax, P. A., Addis, M. E., Koerner, K., Gollan, J. K., Gortner, E., & Prince, S. E. (1996). A component analysis of cognitive-behavioral treatment for depression. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology, 64(2), 295–304. [CrossRef]

- Lagun, N. (2025a). Cognitive Drive Architecture: Derivation and Validation of Lagun’s Law for Modeling Volitional Effort. Preprints. [CrossRef]

- Lagun, N. (2025b). Lagun’s law and the foundations of cognitive drive architecture: A first principles theory of effort and performance. International Journal of Science and Research Archive. [CrossRef]

- Lagun, N. (2025c). Latent Task Architecture: Modeling Cognitive Readiness Under Unresolved Intentions. [CrossRef]

- Lewinsohn, P. M. (1974). A behavioral approach to depression. In R. J. Friedman & M. M. Katz (Eds.), The psychology of depression: Contemporary theory and research. John Wiley & Sons.

- Martell, C. R., Addis, M. E., & Jacobson, N. S. (2001). Depression in context: Strategies for guided action. W W Norton & Co.

- Montague, P. R., Dayan, P., & Sejnowski, T. J. (1996). A framework for mesencephalic dopamine systems based on predictive Hebbian learning. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience, 16(5), 1936–1947. [CrossRef]

| Domain | Extracted Elements (Hopko et al., 2011) |

| Behavioral Patterns | Long sleep duration, behavioral withdrawal, consistent inactivity |

| Values & Meaning | Identity collapsed into caregiving role; difficulty expressing non-caregiver goals |

| Compliance Indicators | Non-completion of activity logs; failure to initiate scheduled behaviors across sessions |

| Psychoeducation Engagement | Intellectual understanding of BA principles; lack of emotional integration; continued belief that mood must precede behavior |

| Psychosocial Context | Breast cancer diagnosis; caregiver strain; low environmental reinforcement; emotionally distant spousal relationship |

| Treatment Process | Twelve-session BA protocol completed; no observed activation or mood change throughout |

| CDA Variable | Reflects | Existing Measurement Approaches (MVA-Compatible) |

| Primode | Ignition readiness | Action-initiation latency tasks; voluntary response delays |

| CAP | Emotional activation potential | Affective-intensity scales; arousal indices; motivational state ratings |

| Flexion | Task–system fit | Task-fit questionnaires; cognitive load/effort scales; flow disruption measures |

| Anchory | Attention tether strength | Continuous Performance Test; fixation decay via eye-tracking; sustained attention metrics |

| Grain | Emotional/physical/contextual friction | Workload/friction indices; strain ratings; fatigue and burden metrics |

| Slip | Behavioral variability | Day-to-day performance variance; intraindividual RT spread; micro-fluctuation measures |

| CDA Variable | Conceptual Treatment Implication |

| Primode | No activation occurs when ignition readiness is below the threshold. |

| CAP | Desire must generate sufficient voltage to overcome resistance. |

| Flexion | Tasks must be adaptable to a person’s cognitive architecture. |

| Anchory | Intentions need tether stability to persist across contexts. |

| Grain | High resistance must be reduced before scheduling tasks. |

| Slip | Variability allows accidental footholds; low Slip produces rigid nonresponse |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).