Submitted:

08 December 2025

Posted:

11 December 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- To develop a comprehensive framework to clearly understand tourists’ PEBs at heritage sites;

- To explore the formation of tourists’ PEBs as a process of internalizing personal norms; and

- To explore the impact of internal motivation and travel companions’ influences on the formation of tourists’ PEBs.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Self-Determination Theory (SDT)

2.2. Norm Activation Model (NAM)

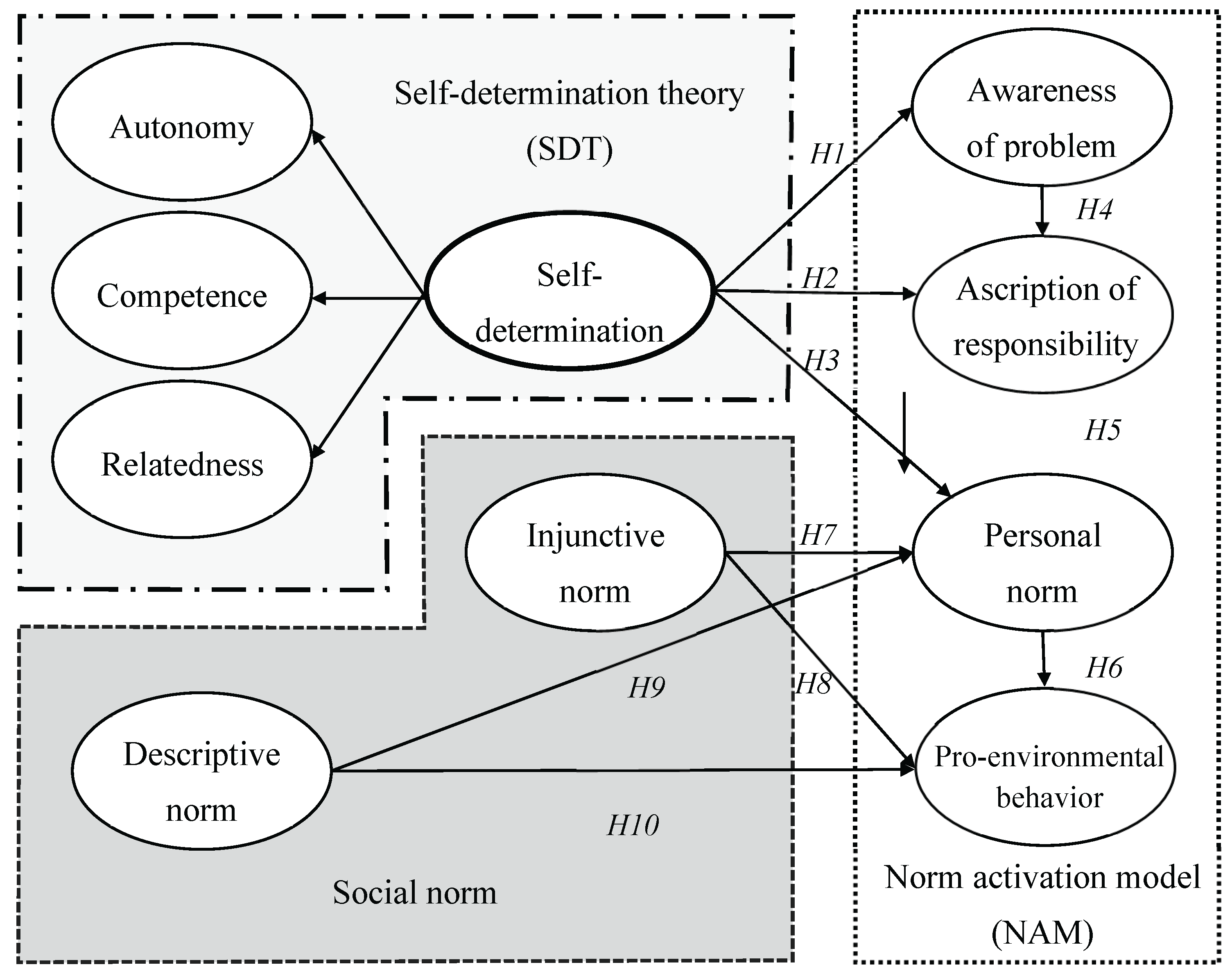

2.3. Hypotheses Development

3. Methods

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Measures

3.3. Sample Profile

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

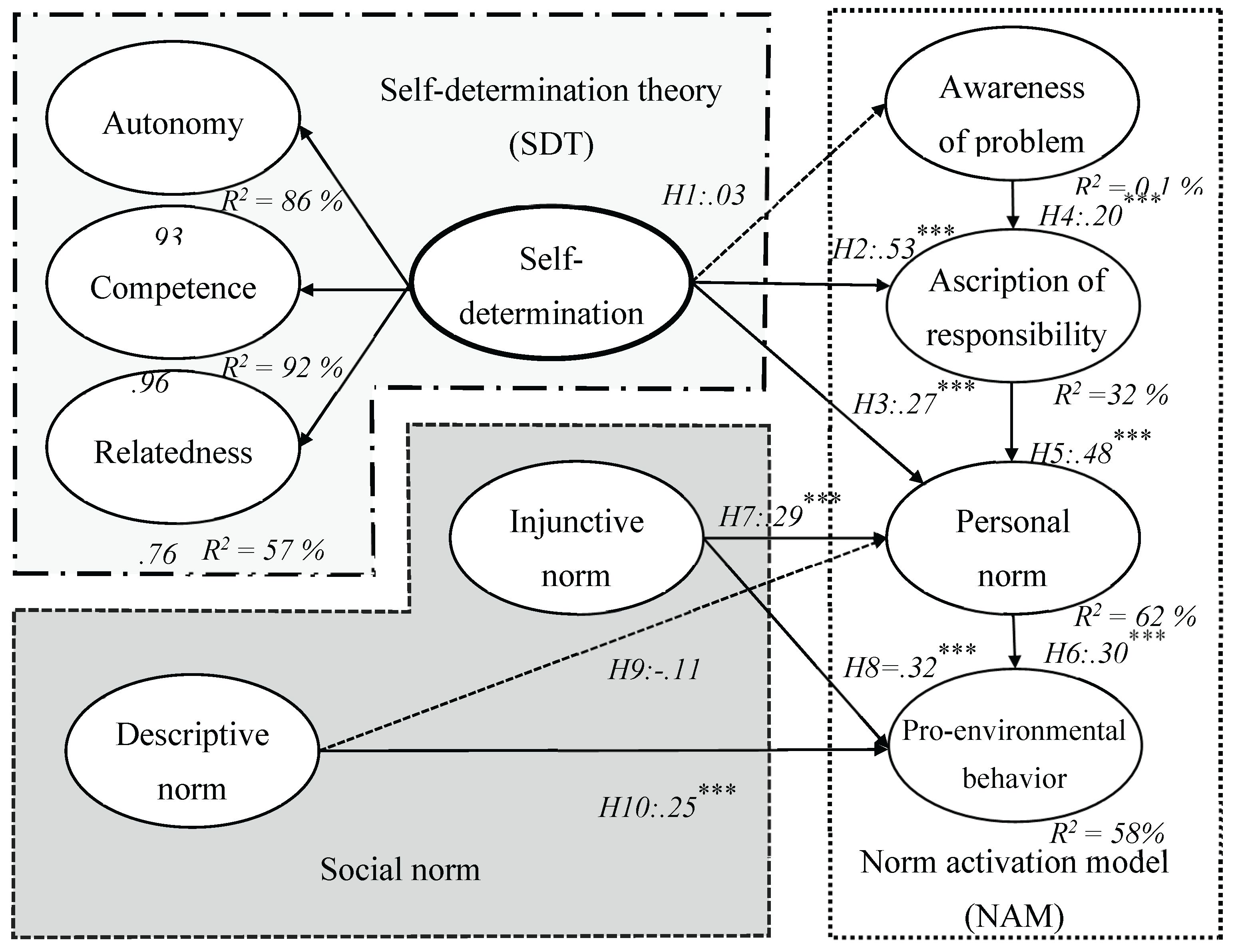

4.2. Structural Equation Modeling

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Summary of Findings

5.2. Theoretical Implications

5.3. Practical Implications

5.4. Limitations

References

- Ahmad, F., Draz, M. U., Su, L., & Rauf, A. (2019). Taking the bad with the good: The nexus between tourism and environmental degradation in the lower middle-income southeast asian economies. Journal of Cleaner Production, 233, 1240–1249. [CrossRef]

- Akadiri, S. S., Lasisi, T. T., Uzuner, G., & Akadiri, A. C. (2020). Examining the causal impacts of tourism, globalization, economic growth and carbon emissions in tourism island territories: bootstrap panel Granger causality analysis. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(4), 470–484. [CrossRef]

- Al-Ansi, A., Lee, J. S., King, B., & Han, H. (2021). Stolen history: Community concern towards looting of cultural heritage and its tourism implications. Tourism Management, 87, 104349. [CrossRef]

- Ariestiningsih, E. S., Muchtar, A. A., Marhamah, M., & Sulaeman, M. (2020). The role of ascription of responsibility on Pro Environmental Behavior in Jakarta communities. In Conference On Recent Innovation (ICRI 2018). Jakarta: Scitepress-Science and Technology (pp. 2251-2258).

- Arroyo, R., Ruiz, T., Mars, L., Rasouli, S., & Timmermans, H. (2020). Influence of values, attitudes towards transport modes and companions on travel behavior. Transportation research part F: traffic psychology and behaviour, 71, 8-22. [CrossRef]

- Ateş, H. (2020). Merging theory of planned behavior and value identity personal norm model to explain pro-environmental behaviors. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 24, 169-180. [CrossRef]

- Autin, K. L., Herdt, M. E., Garcia, R. G., & Ezema, G. N. (2022). Basic psychological need satisfaction, autonomous motivation, and meaningful work: a self-determination theory perspective. Journal of Career Assessment, 30(1), 78-93. [CrossRef]

- Barszcz, S. J., Oleszkowicz, A. M., Bąk, O., & Słowińska, A. M. (2023). The role of types of motivation, life goals, and beliefs in pro-environmental behavior: the Self-Determination Theory perspective. Current Psychology, 42(21), 17789-17804. [CrossRef]

- Baxter, D., & Pelletier, L. G. (2020). The roles of motivation and goals on sustainable behaviour in a resource dilemma: A self-determination theory perspective. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 69, 101437. [CrossRef]

- Bagozzi, R. P., & Yi, Y. (1988). On the evaluation of structural equation models. Journal of the academy of marketing science, 16, 74-94.

- Bergquist, M., Nilsson, A., & Schultz, W. P. (2019). A meta-analysis of field-experiments using social norms to promote pro-environmental behaviors. Global Environmental Change, 59, 101941. [CrossRef]

- Bicchieri, C., Muldoon, R., & Sontuoso, A. (2018). Social norms. The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy.

- Cialdini, R. B. (1998). Social influence: Social norms, conformity, and compliance. The handbook of social psychology/McGraw-Hill.

- Cialdini, R. B., Reno, R. R., & Kallgren, C. A. (1990). A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of personality and social psychology, 58(6), 1015.

- Cialdini, R. B., & Jacobson, R. P. (2021). Influences of social norms on climate change-related behaviors. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 42, 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Czajkowski, M., Hanley, N., & Nyborg, K. (2017). Social norms, morals and self-interest as determinants of pro-environment behaviours: the case of household recycling. Environmental and Resource Economics, 66, 647-670. [CrossRef]

- Davari, D., Nosrati, S., & Kim, S. (2024). Do cultural and individual values influence sustainable tourism and pro-environmental behavior? Focusing on Chinese millennials. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 41(4), 559-577. [CrossRef]

- D’Arco, M., Marino, V., & Resciniti, R. (2023). Exploring the pro-environmental behavioral intention of Generation Z in the tourism context: The role of injunctive social norms and personal norms. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1-22. [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). The general causality orientations scale: Self-determination in personality. Journal of research in personality, 19(2), 109-134. [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4) , 227- 268. [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Self-determination theory: A macrotheory of human motivation, development, and health. Canadian psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 49(3), 182. [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., Olafsen, A. H., & Ryan, R. M. (2017). Self-determination theory in work organizations: The state of a science. Annual review of organizational psychology and organizational behavior, 4, 19-43. [CrossRef]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum Press.

- De Groot, J. I., & Steg, L. (2009). Morality and prosocial behavior: The role of awareness, responsibility, and norms in the norm activation model. The Journal of social psychology, 149(4), 425-449.

- De Groot, J. I., Bondy, K., & Schuitema, G. (2021). Listen to others or yourself? The role of personal norms on the effectiveness of social norm interventions to change pro-environmental behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 78, 101688. [CrossRef]

- Ding, M., Liu, X., & Liu, P. (2024). Parent-child environmental interaction promotes pro-environmental behaviors through family well-being: An actor-partner interdependence mediation model. Current Psychology, 43(18), 16476-16488. [CrossRef]

- Doran, R., & Larsen, S. (2016). The relative importance of social and personal norms in explaining intentions to choose eco-friendly travel options. International Journal of Tourism Research, 18(2), 159-166. [CrossRef]

- Dworkin, G. (1988).The theory and practice of autonomy. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Elgaaied-Gambier, L., Monnot, E., & Reniou, F. (2018). Using descriptive norm appeals effectively to promote green behavior. Journal of Business Research, 82, 179-191. [CrossRef]

- Esfandiar, K., Dowling, R., Pearce, J., & Goh, E. (2020). Personal norms and the adoption of pro-environmental binning behaviour in national parks: An integrated structural model approach. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(1), 10-32. [CrossRef]

- Faraz, N. A., Ahmed, F., Ying, M., & Mehmood, S. A. (2021). The interplay of green servant leadership, self-efficacy, and intrinsic motivation in predicting employees’ pro-environmental behavior. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 28(4), 1171-1184. [CrossRef]

- Farrow, K., Grolleau, G., & Ibanez, L. (2017). Social norms and pro-environmental behavior: A review of the evidence. Ecological Economics, 140, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Filimonau, V., Matute, J., Mika, M., & Faracik, R. (2018). National culture as a driver of pro-environmental attitudes and behavioural intentions in tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 26(10), 1804–1825. [CrossRef]

- Fishbach, A., & Woolley, K. (2022). The structure of intrinsic motivation. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 9, 339-363.

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of marketing research, 18(1), 39-50.

- Fu, L., Zhang, Y., & Bai, Y. (2017). Pro-environmental awareness and behaviors on campus: Evidence from Tianjin, China. EURASIA Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 14(1), 427-445.

- Gagné, M., & Deci, E. L. (2005). Self-determination theory and work motivation. Journal of Organizational behavior, 26(4), 331-362. [CrossRef]

- Grilli, G., & Curtis, J. (2021). Encouraging pro-environmental behaviours: A review of methods and approaches. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 135, 110039. [CrossRef]

- Gross, J., & Vostroknutov, A. (2022). Why do people follow social norms?. Current Opinion in Psychology, 44, 1-6. [CrossRef]

- Han, H., Hwang, J., Kim, J., & Jung, H. (2015). Guests’ pro-environmental decision-making process: Broadening the norm activation framework in a lodging context. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 47, 96-107. [CrossRef]

- Han, H., Hwang, J., & Lee, M. J. (2017). The value–belief–emotion–norm model: Investigating customers’ eco-friendly behavior. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 34(5), 590-607.

- Han, H. (2021). Consumer behavior and environmental sustainability in tourism and hospitality: A review of theories, concepts, and latest research. Sustainable Consumer Behaviour and the Environment, 1-22.

- Han, H., & Hyun, S. S. (2017). Drivers of customer decision to visit an environmentally responsible museum: Merging the theory of planned behavior and norm activation theory. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 34(9), 1155-1168. [CrossRef]

- Helferich, M., Thøgersen, J., & Bergquist, M. (2023). Direct and mediated impacts of social norms on pro-environmental behavior. Global Environmental Change, 80, 102680. [CrossRef]

- Huang, C. H., Lings, I., Beatson, A., & Chou, C. Y. (2018). Promoting consumer environmental friendly purchase behaviour: A synthesized model from three short-term longitudinal studies in Australia. Journal of Environmental Planning and Management, 61(12), 2067-2093. [CrossRef]

- Huber, R. A., Anderson, B., & Bernauer, T. (2018). Can social norm interventions promote voluntary pro environmental action?. Environmental science & policy, 89, 231-246. [CrossRef]

- Kang, S. E. (2022). Travelers’ pro-environmental behaviors in the Hyperloop context: Integrating norm activation and AIDA models. International Journal of Tourism Research, 24(6), 813-826. [CrossRef]

- Keizer, K., & Schultz, P. W. (2018). Social norms and pro-environmental behaviour. Environmental psychology: An introduction, 179-188. [CrossRef]

- Khan, A. N. (2024). Elucidating the effects of environmental consciousness and environmental attitude on green travel behavior: Moderating role of green self-efficacy. Sustainable Development, 32(3), 2223-2232. [CrossRef]

- Khan, F., Ahmed, W., & Najmi, A. (2019). Understanding consumers’ behavior intentions towards dealing with the plastic waste: Perspective of a developing country. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 142, 49-58. [CrossRef]

- Kiatkawsin, K., & Han, H. (2017). Young travelers’ intention to behave pro-environmentally: Merging the value-belief-norm theory and the expectancy theory. Tourism management, 59, 76-88. [CrossRef]

- Kim, J. J., & Hwang, J. (2020). Merging the norm activation model and the theory of planned behavior in the context of drone food delivery services: Does the level of product knowledge really matter?. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 42, 1-11. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. J., Bonn, M., & Lee, C. K. (2020). The effects of motivation, deterrents, trust, and risk on tourism crowdfunding behavior. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 25(3), 244-260. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. S., & Stepchenkova, S. (2020). Altruistic values and environmental knowledge as triggers of pro-environmental behavior among tourists. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(13), 1575-1580. [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. H., & Seock, Y. K. (2019). The roles of values and social norm on personal norms and pro-environmentally friendly apparel product purchasing behavior: The mediating role of personal norms. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 51, 83-90. [CrossRef]

- Koliotasi, A. S., Abeliotis, K., & Tsartas, P. G. (2023). Understanding the Impact of Waste Management on a Destination′ s Image: A Stakeholders′ Perspective. Tourism and Hospitality, 4(1), 38-50. [CrossRef]

- Landon, A. C., Woosnam, K. M., & Boley, B. B. (2018). Modeling the psychological antecedents to tourists’ pro-sustainable behaviors: An application of the value-belief-norm model. Journal of sustainable tourism, 26(6), 957-972. [CrossRef]

- Lange, F., & Dewitte, S. (2019). Measuring pro-environmental behavior: Review and recommendations. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 63, 92-100. [CrossRef]

- Legault, L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Encyclopedia of personality and individual differences, 2416-2419.

- Lehto, X. Y., Choi, S., Lin, Y. C., & MacDermid, S. M. (2009). Vacation and family functioning. Annals of Tourism Research, 36(3), 459-479.

- Li, Q., & Wu, M. (2020). Tourists’ pro-environmental behaviour in travel destinations: Benchmarking the power of social interaction and individual attitude. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(9), 1371-1389. [CrossRef]

- Li, X., Liu, Z., & Wuyun, T. (2022). Environmental value and pro-environmental behavior among young adults: the mediating role of risk perception and moral anger. Frontiers in psychology, 13, 771421. [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S. M. C., Guerreiro, J., & Han, H. (2022). Past, present, and future of pro-environmental behavior in tourism and hospitality: A text-mining approach. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(1), 258-278. [CrossRef]

- Lu, H., Zou, J., Chen, H., & Long, R. (2020). Promotion or inhibition? Moral norms, anticipated emotion and employee’s pro-environmental behavior. Journal of Cleaner Production, 258, 120858. [CrossRef]

- Lv, X., Shi, K., Xu, S., & Wu, A. (2024). Will tourists’ pro-environmental behavior influence their well-being? An examination from the perspective of warm glow theory. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 32(8), 1453-1470. [CrossRef]

- Melvin, J., Winklhofer, H., & McCabe, S. (2020). Creating joint experiences-Families engaging with a heritage site. Tourism Management, 78, 104038. [CrossRef]

- Meng, B., Lee, M. J., Chua, B. L., & Han, H. (2022). An integrated framework of behavioral reasoning theory, theory of planned behavior, moral norm and emotions for fostering hospitality/tourism employees’ sustainable behaviors. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34(12), 4516-4538. [CrossRef]

- Michailidou, A. V., Vlachokostas, C., & Moussiopoulos, Ν. (2016). Interactions between climate change and the tourism sector: Multiple-criteria decision analysis to assess mitigation and adaptation options in tourism areas. Tourism Management, 55, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Miyakawa, E., & Oguchi, T. (2022). Family tourism improves parents’ well-being and children’s generic skills. Tourism Management, 88, 104403.

- Nguyen, T. N., Lobo, A., & Nguyen, B. K. (2018). Young consumers’ green purchase behaviour in an emerging market. Journal of Strategic Marketing, 26(7), 583-600. [CrossRef]

- Nyborg, K. (2018). Social norms and the environment. Annual Review of Resource Economics, 10(1), 405-423.

- Park, E., Lee, S., Lee, C. K., Kim, J. S., & Kim, N. J. (2018). An integrated model of travelers’ pro-environmental decision-making process: The role of the New Environmental Paradigm. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 23(10), 935–948. [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y. T., Saboori, B., Ranjbar, O., & Can, M. (2022). The effects of tourism market diversification on CO2 emissions: evidence from Australia. Current Issues in Tourism, 26(4), 518–525. [CrossRef]

- Ritchie, B. W., Prideaux, B., Thompson, M., & Demeter, C. (2022). Understanding tourists’ attitudes toward interventions for the Great Barrier Reef: an extension of the norm activation model. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(6), 1364-1383. [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.M. & Deci, E.L. (2000), “Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being”, American Psychologist, 55 (1), 68-462.

- Ryan, R.M. & Deci, E.L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary educational psychology, 61, 101860. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S. H. (1973). Normative explanations of helping behavior: A critique, proposal, and empirical test. Journal of experimental social psychology, 9(4), 349-364. [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, S. H. (1977). Normative influences on altruism. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 10, pp. 221-279). Academic Press.

- Setiawan, B., Afiff, A. Z., & Heruwasto, I. (2020). Integrating the theory of planned behavior with norm activation in a pro-environmental context. Social Marketing Quarterly, 26(3), 244-258. [CrossRef]

- Setiawan, B., Afiff, A. Z., & Heruwasto, I. (2021). Personal norm and peo-environmental consumer behavior: an application of norm activation theory. ASEAN Marketing Journal, 13(1), 3. [CrossRef]

- Sharpe, E. J., Perlaviciute, G., & Steg, L. (2021). Pro-environmental behaviour and support for environmental policy as expressions of pro-environmental motivation. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 76, 101650. [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R., & Gupta, A. (2020). Pro-environmental behaviour among tourists visiting national parks: Application of value-belief-norm theory in an emerging economy context. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 25(8), 829-840. [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, K. M., Elliot, A. J., Kim, Y., & Kasser, T. (2001). What is satisfying about satisfying events? Testing 10 candidate psychological needs. Journal of personality and social psychology, 80(2), 325.

- Shi, H., Fan, J., & Zhao, D. (2017). Predicting household PM2. 5-reduction behavior in Chinese urban areas: An integrative model of Theory of Planned Behavior and Norm Activation Theory. Journal of Cleaner Production, 145, 64-73. [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y. H., Im, J., Jung, S. E., & Severt, K. (2018). The theory of planned behavior and the norm activation model approach to consumer behavior regarding organic menus. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 69, 21-29. [CrossRef]

- Silvi, M., & Padilla, E. (2021). Pro-environmental behavior: Social norms, intrinsic motivation and external conditions. Environmental Policy and Governance, 31(6), 619-632. [CrossRef]

- Su, L., Cheng, J., Wen, J., Kozak, M., & Teo, S. (2022). Does seeing deviant other-tourist behavior matter? The moderating role of travel companions. Tourism Management, 88, 104434. [CrossRef]

- Su, L., Li, M., Wen, J., & He, X. (2025). How do tourism activities and induced awe affect tourists’ pro-environmental behavior?. Tourism Management, 106, 105002. [CrossRef]

- Tyson, A., Kennedy, B., & Funk, C. (2021). Gen Z, Millennials stand out for climate change activism, social media engagement with issue.

- Van Riper, C. J., & Kyle, G. T. (2014). Understanding the internal processes of behavioral engagement in a national park: A latent variable path analysis of the value-belief-norm theory. Journal of environmental psychology, 38, 288-297.

- Videras, J., Owen, A. L., Conover, E., & Wu, S. (2012). The influence of social relationships on pro-environmental behaviors. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 63(1), 35-50. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., Wang, J., Wan, L., & Wang, H. (2023). Social norms and tourists’ pro-environmental behaviors: Do ethical evaluation and Chinese cultural values matter? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(6), 1413–1429. [CrossRef]

- Wang, X., & Zhang, C. (2020). Contingent effects of social norms on tourists’ pro-environmental behaviours: The role of Chinese traditionality. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(10), 1646-1664. [CrossRef]

- White, K. M., Smith, J. R., Terry, D. J., Greenslade, J. H., & McKimmie, B. M. (2009). Social influence in the theory of planned behaviour: The role of descriptive, injunctive, and in-group norms. British journal of social psychology, 48(1), 135-158. [CrossRef]

- Wu, L., Zhu, Y., & Zhai, J. (2022). Understanding waste management behavior among university students in China: environmental knowledge, personal norms, and the theory of planned behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 771723. [CrossRef]

- Wu, J., Font, X., & Liu, J. (2021). Tourists’ pro-environmental behaviors: Moral obligation or disengagement?. Journal of Travel Research, 60(4), 735-748. [CrossRef]

- Xu, X. (2018). Does traveler satisfaction differ in various travel group compositions? Evidence from online reviews. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(3), 1663-1685.

- Yan, H., & Chai, H. (2021). Consumers’ intentions towards green hotels in China: An empirical study based on extended norm activation model. Sustainability, 13(4), 2165. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D., & Tu, Y. (2021). Green building, pro-environmental behavior and well-being: Evidence from Singapore. Cities, 108, 102980. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X., Liu, J., & Zhao, K. (2018). Antecedents of citizens’ environmental complaint intention in China: An empirical study based on norm activation model. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 134, 121-128. [CrossRef]

| Measures | Standardized loading |

Cronbach’s α |

|---|---|---|

|

Awareness of problem Tourism can hurt the sustainability of heritage at tourism destinations. The tourism industry can cause climate change. The tourism industry can cause depletion of natural resources. |

.66 .87 .86 |

.83 |

|

Ascription of responsibility I feel responsible for the environmental problems caused by tourism activities. Travelers are responsible for avoiding environmental problems caused by tourism activities. Travelers are responsible for contributing to protect the environment and heritage during their travels. |

.77 .83 .86 |

.86 |

|

Personal norm When traveling, I feel the obligation to contribute to improve the environment and heritage. When traveling, I feel the obligation to comply with recommendations of heritage and environmental protection. When traveling, I feel the obligation to comply with of heritage and environmental protection. When traveling, I feel the obligation to encourage anyone to have a vision of heritage and environmental protection. |

.84 .92 .90 .73 |

.90 |

|

Injunctive norm For those who are important to you (like relatives, friends, or colleagues) ~ they would say/think I should act pro-environmentally when travelling. they think that engaging in environmental protection while travelling is something that one ought to do. they would prefer/approve of behaving in an environmentally friendly way while travelling. they expect me to participate in environmental protection when travelling. |

.88 .88 .91 .89 |

.94 |

|

Descriptive norm For those who are important to you (like relatives, friends, or colleagues) ~ a high percentage of them take part in environmental protection during travel. they engage in environmental protection during travel. most of them participate in environmental protection while travelling. they are very likely to engage in environmental protection when travelling. |

.90 .91 .90 .87 |

.94 |

|

Autonomy I want my choices to be based on my true interests and values while performing pro-environmental behaviors at Pingyao ancient city. I want to be free to do things my own way while performing pro-environmental behaviors at Pingyao ancient city. I want my choices to be expressed my “true self” while performing pro-environmental behaviors at Pingyao ancient city. |

.89 .91 .62 |

.92 |

|

Competence I want to successfully complete difficult tasks and projects while performing pro-environmental behaviors at Pingyao ancient city. I want to take on and master challenges while performing pro-environmental behaviors at Pingyao ancient city. I want to be capable in what I will do while performing pro-environmental behaviors at Pingyao ancient city. |

.89 .83 .84 |

.89 |

|

Relatedness I want to have a sense of contact with my companions (family, friends, locals, etc.) who care for me, and whom I care for. I want to close and connected with my companions (family, friends, locals, etc.) while performing sustainable behaviors at destinations. I want to have a strong sense if intimacy with my companions (family, friends, locals, etc.) I spent time with while performing pro-environmental behaviors at Pingyao ancient city. |

.88 .92 .85 |

.91 |

|

Pro-environmental behavior I perform green practices to protect the environment on my trips. I act responsibly to protect the destination’s environment on my trips. I do not disrupt the fauna and flora on my trips. I consume natural resources responsibly on my trips. |

.85 .85 .83 .87 |

.90 |

| AP | AR | PN | IN | DN | Aut | Com | Rel | PEB | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AP | 1.00 | ||||||||

| AR | .23a(.05)b | 1.00 | |||||||

| PN | .04(.00) | .71(.50) | 1.00 | ||||||

| IN | .01(.00) | .48(.23) | .62(.38) | 1.00 | |||||

| DN | .07(.00) | .46(.21) | .54(.29) | .81(.66) | 1.00 | ||||

| Aut | .01(.00) | .46(.21) | .57(.32) | .68(.46) | .71(.50) | 1.00 | |||

| Com | .04(.00) | .52(.27) | .63(.40) | .72(.52) | .74(.55) | .90(.81) | 1.00 | ||

| Rel | .00(.00) | .39(.15) | .49(.24) | .58(.34) | .59(.35) | .73(.53) | .70(.49) | 1.00 | |

| PEB | -.03(.00) | .51(.26) | .62(.38) | .70(.49) | .66(.44) | .63(.40) | .70(.49) | .64(.41) | 1.00 |

| AVE | .64 | .68 | .72 | .79 | .80 | .67 | .73 | .78 | .72 |

| C.R. | .84 | .86 | .91 | .94 | .94 | .85 | .89 | .91 | .91 |

| Mean | 4.13 | 5.49 | 5.79 | 5.76 | 5.59 | 5.37 | 5.55 | 5.37 | 5.69 |

| S.D. | 1.37 | 1.18 | 1.05 | 1.05 | 1.09 | 1.11 | 1.08 | 1.17 | .97 |

| Hypotheses | Paths | Coefficients | t-values | Hypothesis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypothesis 1 | SD → AP | .03 | .55 | Not supported |

| Hypothesis 2 | SD → AR | .53 | 10.66*** | Supported |

| Hypothesis 3 | SD → PN | .27 | 4.03*** | Supported |

| Hypothesis 4 | AP → AR | .20 | 4.34*** | Supported |

| Hypothesis 5 | AR → PN | .48 | 9.96*** | Supported |

| Hypothesis 6 | PN → PEB | .30 | 6.51*** | Supported |

| Hypothesis 7 | IN → PN | .29 | 4.31*** | Supported |

| Hypothesis 8 | IN → PEB | .32 | 4.41*** | Supported |

| Hypothesis 9 | DN → PN | -.11 | -1.64 | Not supported |

| Hypothesis 10 | DN → PEB | .25 | 3.82*** | Supported |

| Variance explained | Total effect on PEB: | Indirect effect on PEB: | ||

|

R2 (AP) = 0.1% R2 (AR) = 32% R2 (PN) = 62% |

R2 (PEB) = 58% | βIN→PEB = .38** |

βIN→ PN →PEB = .09** βDN→ PN →PEB = -.03 |

|

| βDN→PEB = .19** | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).